- School of Communication, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, Canada

I investigate in this brief empirical study the social media attacks against female Canadian journalists who have frequently been targeted with online abuse. I used purposive sampling to focus on three journalists: Rachel Gilmore (formerly with Global News), Erica Iffil (freelance with The Hill Times), and Saba Eitizaz (Toronto Star). I employed a mixed method approach to conduct this study by collecting all the available Twitter replies to these three journalists (n = 402,821) posted by 84,962 unique users. The digital analysis results show that there are slight differences in the quantity of attacks on these journalists, but the qualitative assessment of images associated with tweets indicate the need to use manual approaches to better understand the nuances and quality of these disinformation and often racist attacks.

To investigate online trolling against journalists, I used purposive sampling to focus on three Canadian female journalists who recently received wide publicity. These journalists were awarded the Canadian Journalists for Free Expression prize for their journalistic work and courage in countering abusive attacks against them (Campbell, 2022; Powell, 2023); and they come from different racial, religious, and ethnic backgrounds. The latter aspect is important to offer important comparative insight and understanding of the quality and quantity of online trolling or what Waisbord (2020, p. 1030) terms as “mob censorship.” The latter term is defined as “bottom-up, citizen vigilantism aimed at disciplining journalism.” In other words, the diversity of the journalists' identity traits offers an important comparative perspective for this study on abusive content targeting journalists. This point aligns with previous research on this issue; as Kreiss (2019, p. 27) emphasizes, the “social identity is constructed by journalists and for them by other social groups in a distinct socioeconomic context, and it has significant consequences for the institution's legitimacy in the eyes of publics….. The social identity of journalists is at once historically specific, contextually salient and meaningful, and politically consequential.” It is important to mention here that conducting interviews with journalists is very important to further understand the nature of online abuse they frequently receive, but the analysis of social media content can also offer another useful insight about these online attacks.

In addition to addressing the gaps in literature surrounding the systematic study of gendered trolling of journalists within the Canadian context, this paper attempts to explore the methodological limitations in using digital methods such as sentiment analysis alone, for there is a growing need to employ a variety of mixed method approaches especially qualitative assessments. Due to the multimodal nature of abusive content, it has become increasingly important to take into account the textual and visual content in order to enrich the findings. To add further insight into the results of this study, I used the sexist terms identified on the Hatebase database in order to extract relevant abusive tweets. This is similar to the supervised machine learning method used in Frenda et al. (2019) on how to automatically identify misogynistic content and Mondal et al. (2017) on detecting online hate using an online dictionary. Finally and in terms of the platform, this study offers insight from Twitter, which is now known as X, and unfortunately freely extracting full data from this platform using the Academic API is not possible anymore because it got decommissioned; hence, such academic studies remain possible but have become highly expensive if one purchases the new commercial API access.

To conduct the study, I used Twitter Academic API v2 to collect all the available replies to the three journalists' Twitter handles. I focused our attention on Twitter because this is the platform where the three journalists are very active. The datasets span from January 1, 2016 until March 15, 2023 which is when the study was conducted. I started in 2016 because this 7 years time period offers a reasonable timeline and enough data to measure the possible online attacks against journalists. In total, I collected 402,821 replies posted by 84,962 unique users who engaged with these three journalists (@sabaeitizaz 7,503; @wickdchiq: 91,318; @atRachelGilmore: 304,000). I used this time frame to make sure I can capture most of the social media users' reactions toward these three journalists throughout the previous few years. I found, for example, that 872 users have engaged with the three journalists, and 6,853 interacted with two of them without counting the replies made by these three journalists to one another or to other users.

To understand the type of reception these journalists receive, I first conducted an automated and unsupervised sentiment analysis of the replies to these journalists using the sentiment analysis of WordStat nine that contains a large lexicon resource (Hossen and Dev, 2021). The results of the negative comments in the second sentiment analysis, however, are slightly different from the above: Gilmore: 75.37%, Eitizaz: 74.29%, Ifill: 69.21%. As can be seen above, there are minor differences among the journalists with regard to these sentiment scores, for Gilmore received a slightly higher percentage of negative replies than Eitizaz and Ifill.

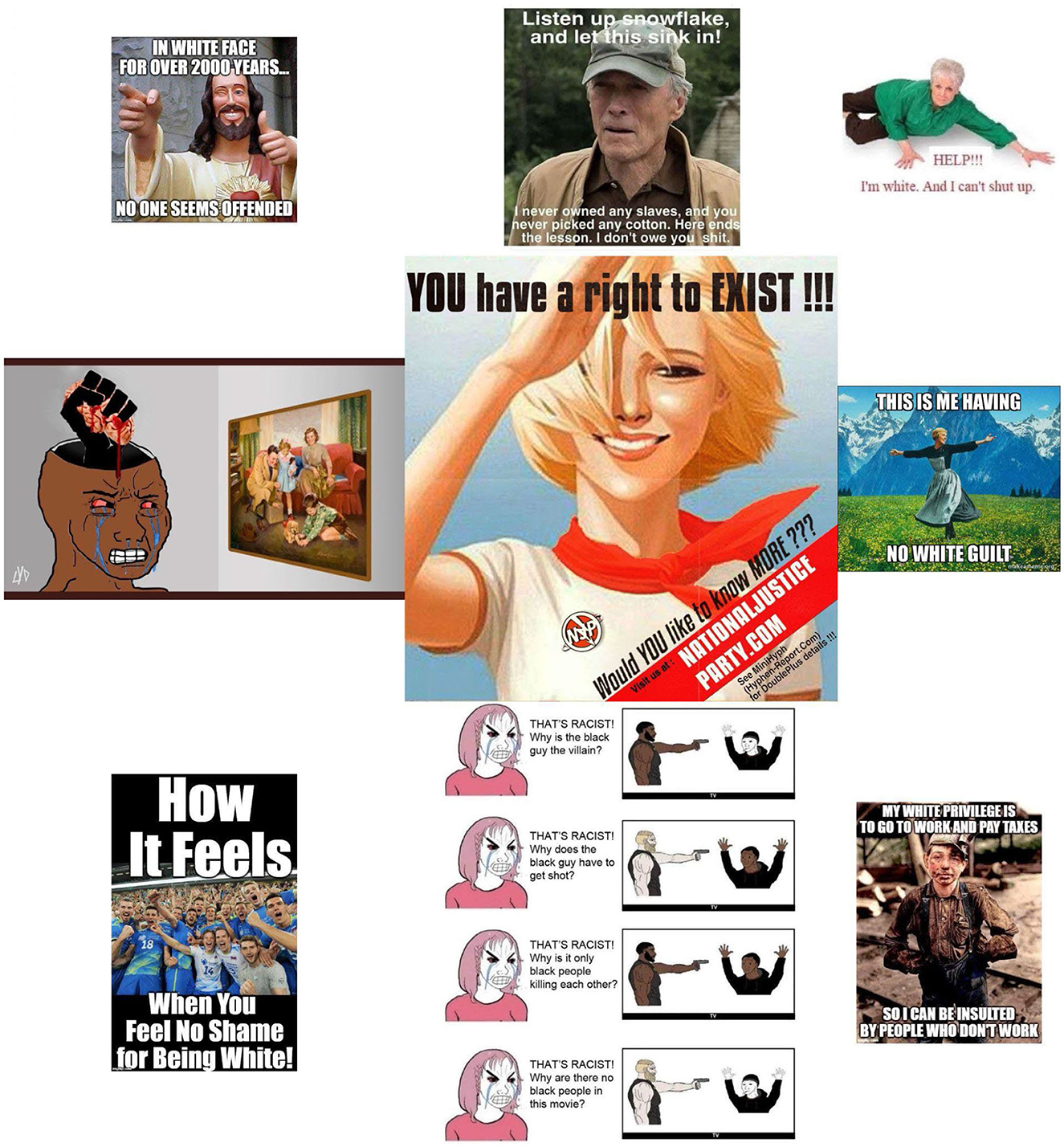

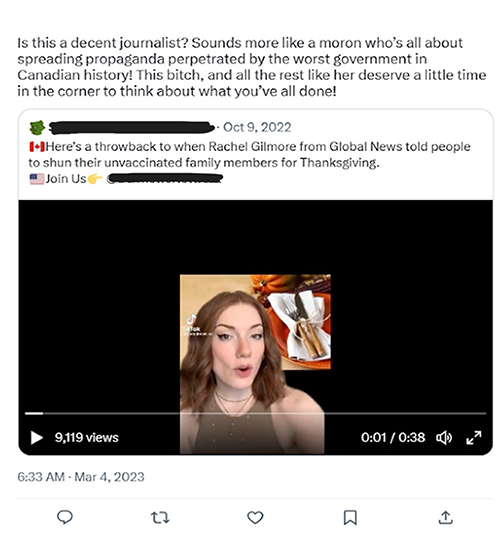

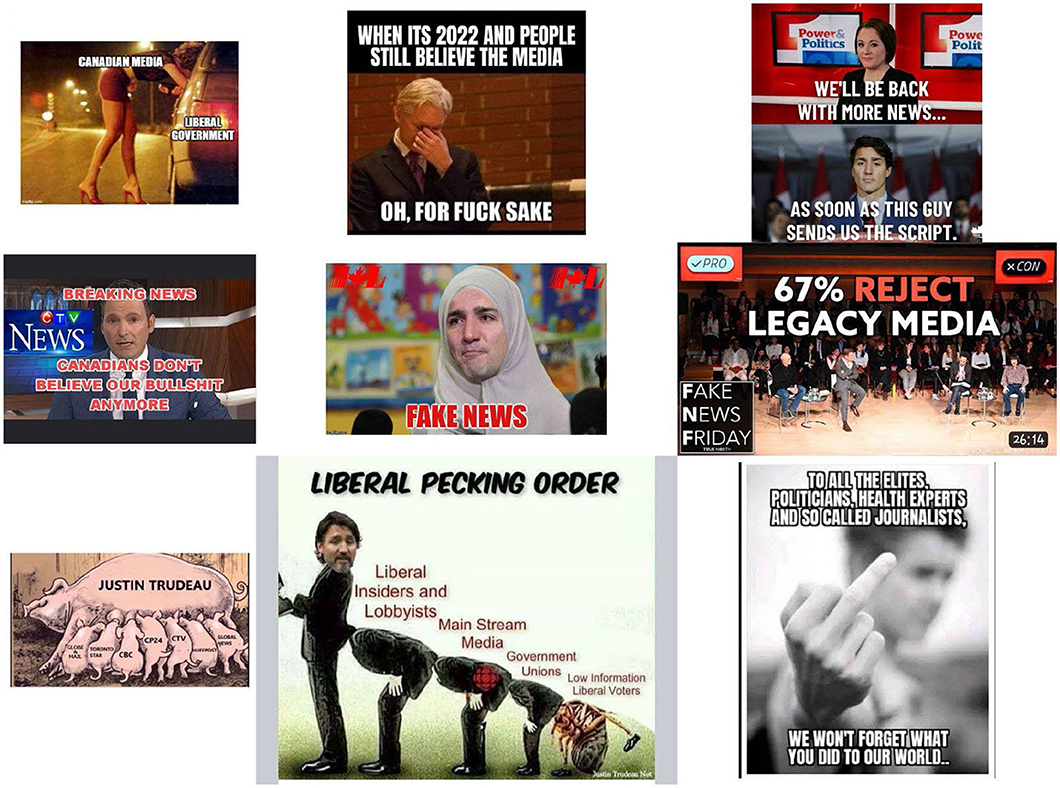

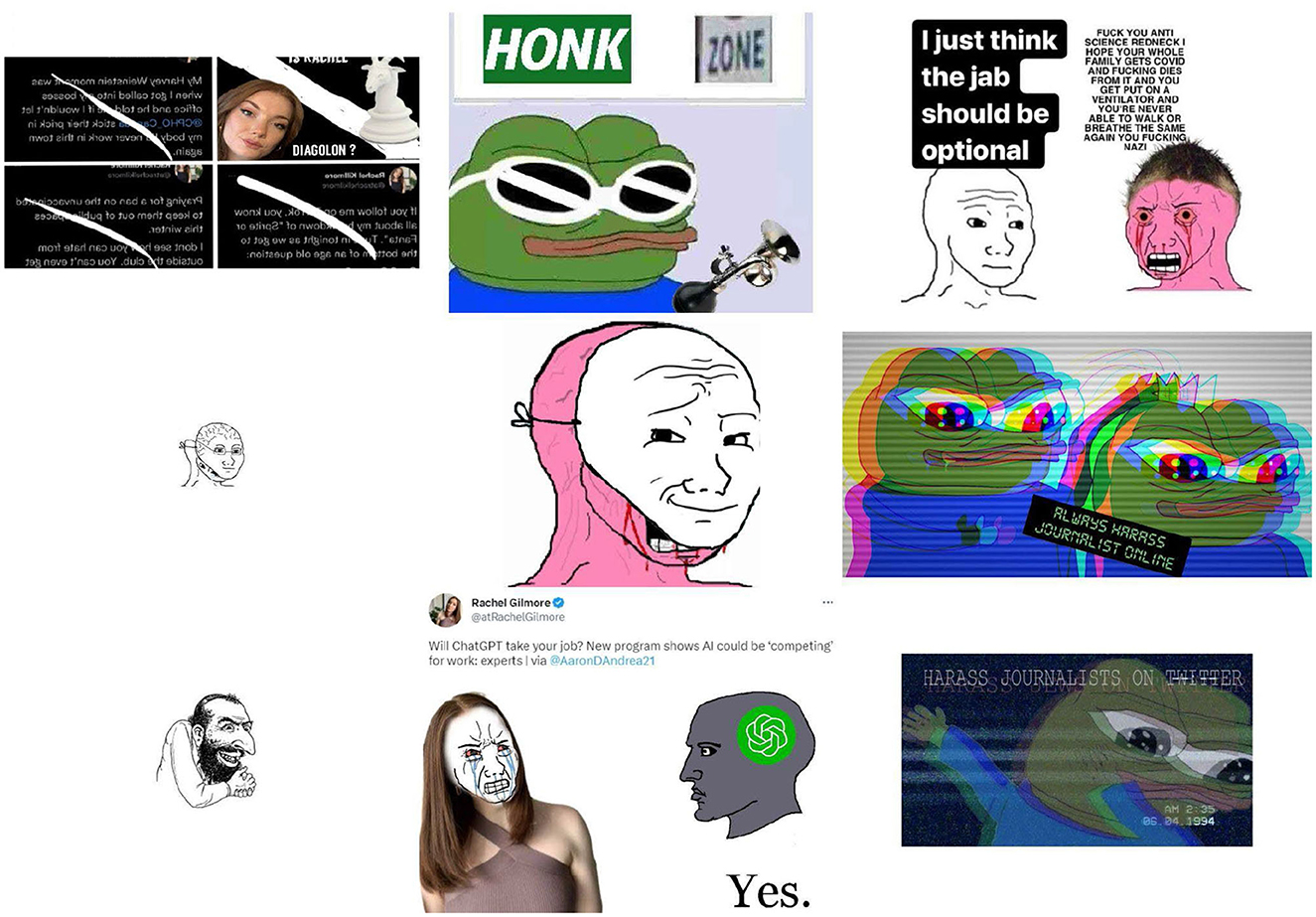

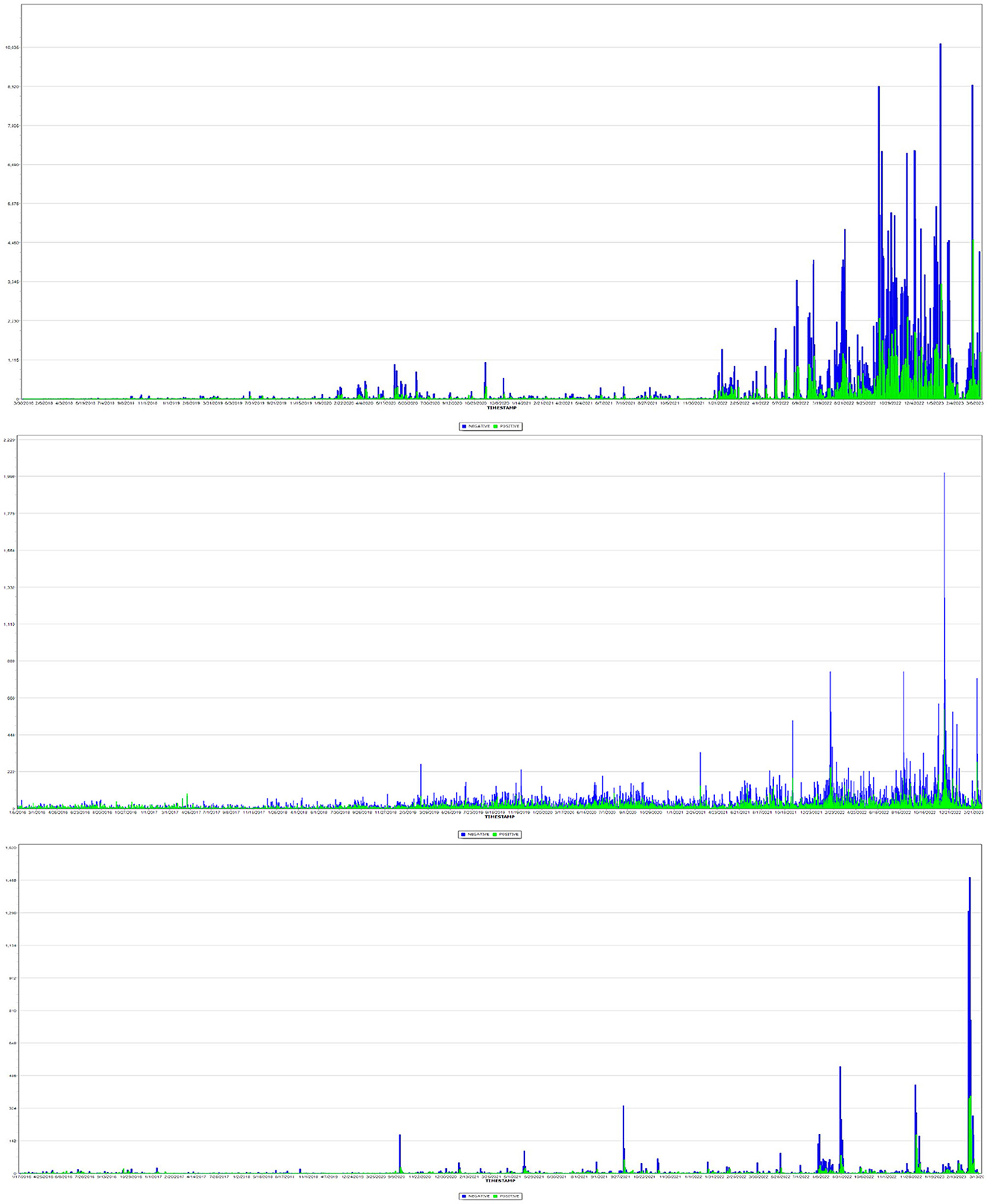

To have a closer look at the sentiments, I calculated the daily sentiments to better understand the time periods of attacks. As can be seen in Figure 1, there is a clear fluctuation of sentiments on a daily basis, depending on certain events or issues discussed online and in the news media. For example, Gilmore's sentiment analysis results show a negative as well as positive spike in March 2023 which is when the news about her departure from Global News is shared. In late 2022 and early 2023, however, most of the sentiments clustered around negative comments. This is the period when the journalist was frequently targeted by Diagolon and other far-right groups who even threatened her physical safety (LaFleche, 2022). Regarding Ifill, the most intense attacks occurred in early December 2022 as a reaction to a video comment she made on the prevalence of racism and white privilege in Canada (See Figure 2). As a matter of fact, many negative images associated with the tweets addressed to Ifill were a reaction against the journalist's advocacy and activism for Black causes (Figure 3). As for Eitizaz, the highest frequency of negative comments can be seen in early March 2023 following her comment on sacking some journalists from their work including the case of Rachel Gilmore (See Figure 4). In fact, there were 527 images associated with Eitizaz's replies, and some of them were directed at Gilmore (See Figures 4, 8). The same applies to some visuals found in the 4,064 images associated with the tweet replies to Ifill.

Figure 1. Daily distribution of sentiment analysis (top) Gilmore, (middle) Ifill, (bottom) Eitizaz using WordStat.

To get more insight from the datasets collected, I used Hatebase, a repository of abusive terms that can be filtered based on certain identity traits like religion, race, gender, and sex. For this study, I focused on sexist abusive terms targeting females (Hatebase, 2023). The Hatebase data has been used in numerous previous academic studies that examined online hate (See for example Silva et al., 2016). As of March 24, 2023, there were 64 abusive terms in this category; however, I removed four terms because they could have general meaning including: “Girl,” “mammy,” “bird,” and “birds.” Also, I did not take the level of offensives into account e.g., low, moderate or intensive because words like 'bitch' is considered moderately offensive in Hatebase, and this might not be accurate. In total, I searched each dataset for 60 abusive terms using a Python script, and I found 1,148 tweets referencing them. The distribution of these abusive tweets is as follows: Gilmore: n = 952, Ifill: n = 160, Eitizaz: n = 36. Because the frequencies of these terms are highly different, it is important to consider the overall number of replies. Accordingly, the journalists received the following percentages of clearly sexist content: Eitizaz: 0.50%; Gilmore: 0.31%; Ifill: 0.19%. Again, there are very minor differences amongst the three journalists when it comes to sexist attacks.

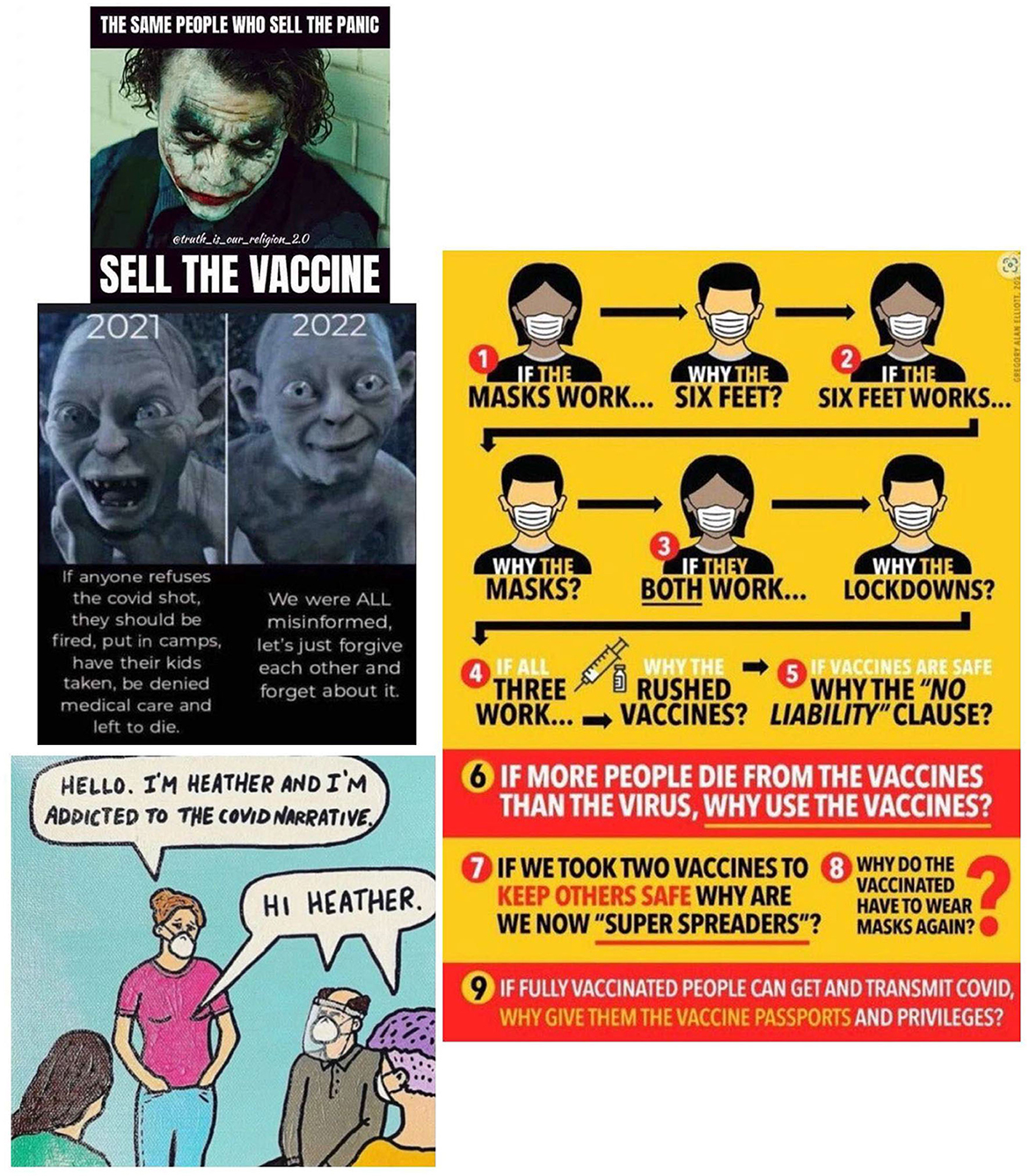

The qualitative examination of images associated with the replies shows that many users targeted liberal mainstream media (Figure 5), and/or employed far-right symbols like that of Wojak in their responses to the journalists including Islamophobic and anti-Semitic messages (See Figure 6) as well as referencing COVID misinformation about the vaccine (Figure 7) or using doctored images showing fake news headlines (See Figure 8).

To conclude, online abuse targeting the three journalists examined here shows many similarities like the use of negative sentiments, sexist attacks, and abusive images. However, the volume of attack differs, depending on the journalists' social media activity, their followers, and events taking place offline like work circumstances and/or issues covered by the journalists or discussed in the news media. In this respect, Gilmore is more vocal and active than the two other journalists on Twitter, and she has a popular TikTok account, both enhancing audience engagement, whether be positive or negative. Other important factors to consider when comparing these journalists include the general tone they use on social media, level of activity, and most importantly the nature of political issues they discuss. Without taking the volume of replies into account, I found in this study slight differences in the abusive attacks against the three female journalists, depending on the type of media content examined.

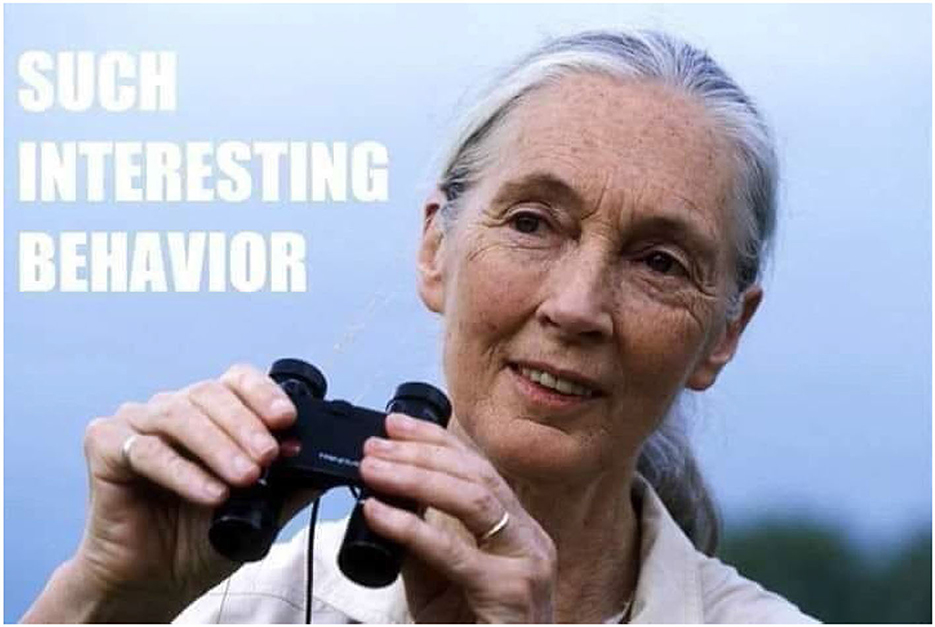

Future studies need to examine different social media platforms because Twitter is not the only one that is used to target journalists. For example, fringe groups are known to be active on alternative online sites like Rumble, BitChute, and Telegram (Langlois et al., 2021); hence, it is necessary to systematically examine these platforms in more details. These sites are also known to have less moderation policies than traditional social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter (Al-Rawi, 2021). Also, the differences between attacks on men vs. women Canadian journalists can be examined, and more studies are needed to investigate the importance of intersectional identities for gender and sex alone cannot offer a full picture of the nature of abusive attacks against journalists. study Wagner (2022), for example, explored the issue of online harassment's perceptions of Canadian politicians using interviews with 101 respondents from diverse backgrounds. Other important identity traits should include race, nationality, religion, and ethnicity (see for example Al-Rawi et al., 2022, 2023). Another technique that requires more examination impersonates the journalist's Twitter handle, for I found two parody accounts targeting Gilmore using very similar usernames (@atRachelGilmor and @itRachelGilmore). Finally and more importantly, I used a number of digital methods to identify abusive content that mostly rely on the decontextualized manifest meaning or what is clearly obvious in the text because of the large data I collected; hence, future studies can rely on a representative sample and qualitatively examine multimodal social media discourses that could uncover other aspects or differences in the quality of abusive content targeting journalists, for there are often nuanced meanings and highly racist messages (See for example Figure 9) that often require contextual knowledge and appropriate background information to be clearly understood.

Figure 9. A highly racist image addressed to Ifill. Jane Morris Goodall, the famous English primatologist, mostly studied chimpanzees.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors for any interested scholars after removing other Twitter users' details.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was not obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article because this is a nonreactive research method based on the analysis of content. All tweets and images are found on the Internet and are in the public domain.

Author contributions

AA-R: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing–original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Digital Citizen Contribution Program, Canadian Heritage, Government of Canada, project no. 1353025. This project was also partly funded by a SSHRC Insight grant-under grant no. R831585 and application no. 435-2022-0478. The title of the project is Mediated democracy and racism discourses in Canada.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Prof. Peter Klein and Dr. Chris Tenove from the Global Reporting Centre at the University of British Columbia for their kind feedback and insights on an earlier version of this paper.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Al-Rawi, A. (2021). Telegramming hate: far-right themes on dark social media. Can. J. Commun. 46, 821–851. doi: 10.22230/cjc.2021v46n4a4055

Al-Rawi, A., Ackah, B. B., and Chun, W. H. (2023). The intersectionality of twitter responses to black Canadian politicians. Soc. Media Soc. 9:20563051231157290. doi: 10.1177/20563051231157290

Al-Rawi, A., Chun, W. H. K., and Amer, S. (2022). Vocal, visible and vulnerable: female politicians at the intersection of Islamophobia, sexism and liberal multiculturalism. Fem. Media Stud. 22, 1918–1935. doi: 10.1080/14680777.2021.1922487

Campbell, I. (2022). ‘Stay the Course': Reporters, Editors Discuss Strategies for Combating Online Hate With Mendicino. The Hill Times. Available online at: https://www.hilltimes.com/story/2022/12/05/stay-the-course-journalists-discuss-strategies-for-combating-online-hate-with-public-safety-minister-mendicino/357755/

Frenda, S., Ghanem, B., Montes-y-Gómez, M., and Rosso, P. (2019). Online hate speech against women: automatic identification of misogyny and sexism on twitter. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 36, 4743–4752. doi: 10.3233/JIFS-179023

Hatebase (2023). Gender- Female. Available online at: https://hatebase.org/search_results/gender_id=6%7Clanguage_id=eng%7Cpage=1

Hossen, M. S., and Dev, N. R. (2021). An improved lexicon based model for efficient sentiment analysis on movie review data. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 120, 535–544. doi: 10.1007/s11277-021-08474-4

Kreiss, D. (2019). The social identity of journalists. Journalism 20, 27–31. doi: 10.1177/1464884918807595

LaFleche, G. (2022). Death Threats. Racist Taunts. Vows of violence. Inside the Increasingly Personal Attacks Targeting Canadian Female Journalists. Toronto Star. Available online at: https://www.thestar.com/news/investigations/2022/09/04/death-threats-racist-taunts-vows-of-violence-inside-the-increasingly-personal-attacks-targeting-canadian-female-journalists.html

Langlois, G., Coulter, N., Elmer, G., and McKelvey, F. (2021). Alt-rights in Canada. Can. J. Commun. 46, 751–755. doi: 10.22230/cjc.2021v46n4a4245

Mondal, M., Silva, L. A., and Benevenuto, F. (2017). “A measurement study of hate speech in social media,” in Proceedings of the 28th ACM conference on hypertext and social media (Prague, Czech Republic), 85–94. doi: 10.1145/3078714.3078723

Powell, B. (2023). Toronto Star Journalists Honoured for Calling Out Online Abuse and ‘Courageous' Reporting. Toronto Star. Avaialable online at: https://www.thestar.com/news/gta/2023/02/15/toronto-star-journalists-honoured-for-calling-out-online-abuse-and-courageous-reporting.html

Silva, L., Mondal, M., Correa, D., Benevenuto, F., and Weber, I. (2016). Analyzing the targets of hate in online social media. Proc. Int. AAAI Conf. Web Soc. Media 10, 687–690. doi: 10.1609/icwsm.v10i1.14811

Wagner, A. (2022). Tolerating the trolls? gendered perceptions of online harassment of politicians in Canada. Femin. Media Stud. 22, 32–47. doi: 10.1080/14680777.2020.1749691

Keywords: social media, female Canadian journalists, disinformation, racialized attacks, online abuse

Citation: Al-Rawi A (2023) Social media attacks against female Canadian journalists. Front. Commun. 8:1260540. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1260540

Received: 18 July 2023; Accepted: 25 September 2023;

Published: 17 October 2023.

Edited by:

Greg Elmer, Toronto Metropolitan University, CanadaReviewed by:

Vincent Raynauld, Emerson College, United StatesFenwick Mckelvey, Concordia University, Canada

Copyright © 2023 Al-Rawi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ahmed Al-Rawi, YWFscmF3aUBzZnUuY2E=

Ahmed Al-Rawi

Ahmed Al-Rawi