- Leiden University Centre for Linguistics, Leiden, Netherlands

This paper proposes a theoretical reduction of the existence of perspective taking in discourse to the combination of two basic methods of communication: iconic simulation, and description by means of conventional symbols. This includes an integration of the depiction theory of quotation and a pragmatic version of the theory of signs. Perspective taking is argued to be a consequence of the iconic simulation of acts, linguistic acts in particular. The basic fact that a single utterance can comprise both depictive and descriptive components is in turn the basis for the occurrence of different variants of speech and thought representation, which are traditionally discussed under the rubric of indirect and free indirect discourse. On this basis, it is argued that the phenomena can actually be analyzed more insightfully (and more simply) directly in terms of interactions between specific linguistic items and the distinction between depiction and description. In addition, this “composite utterance” approach to perspective taking combines abstract conceptual clarity and simplicity with a high degree of flexibility in the way such interactions can work out in specific situations, which allows it to also serve as a basis for the analysis of “multiperspectival” and “doublevoiced” discourse.

1. Introduction: Free indirect discourse and the nature of scientific explanation

Languages allow story tellers to present the verbal utterances and the thoughts of story characters in different ways, and these differences have significant effects on the way readers construe the perspectives of both the narrator and the characters on the story events, as well as the way these perspectives relate to each other. Three generally recognized modes of speech and thought representation (STR for short) that have attracted much attention in linguistics (stylistics in particular) and narratology over the last century or so are direct discourse, indirect discourse, and free indirect discourse—the latter exhibiting grammatical and interpretive characteristics of both direct and indirect discourse. All three forms can be illustrated with the following excerpt from the story “The Tiger Moth” in Bates (1972).

(1) She rested her fork on the edge of her plate and he noticed for the first time that she was wearing no wedding ring. He immediately changed the subject.

“Are you in one of the services?” he said.

No, she said, she was teaching literature and history in St. Anne's High School for Girls. They had been evacuated from London to a mansion called Clifton Court. Did he know it?

In the first sentence we have a representation of an observation of the male character (“he noticed…”), the content of which is given in a subordinate clause (“that she was wearing no wedding ring”); the tense is past, as in the story as a whole. This is called indirect discourse (ID).1 The way his question to her is represented is called direct discourse (DD); the tense of “Are you in one of the services?” is present, it has main clause syntax, and the pronoun refers to the female character, not the reader. ID would have been “(He asked) if she was in one of the services.” This is why DD is said to involve a complete shift to the perspective of the character(s) in the story. The story world provides the perspective from which the interpretation of all elements in the clause is to be determined: What and whom the question is related to, what the pronouns and the tense refer to. In ID, on the other hand, the perspective remains with the narrator. The female character's response in (1), finally, exemplifies free indirect discourse (FID); it has main clause syntax (“she was teaching literature”) like DD, but the tense and the pronouns are of the same type as in ID: “she was,” not “I am (teaching literature).” Particularly illustrative is the final sentence in (1), with the syntax of a direct question, but with the past tense and a 3rd person subject: “Did he know it?,” not “Do you know it?.” This is why FID is considered a mixed category, evoking both the narrator and a character's perspective. Roughly, in DD, characters have their own voice, in ID the narrator apparently stays “in control,” and FID represents a kind of mixture, or intermediate: characters get some, but not all, of their own voice.

Different scholars from different backgrounds have provided analyses of these modes of STR, often including proposals for expanding the range of modes, and there is in fact a continuous lively debate on the proper construal of their properties and differences, in combination with a rich research program into the actual usage and effects of different modes of STR in various contexts and genres, with all their subtleties. But all approaches share the idea that DD and ID are each other's formal and functional opposites, with some modes of STR, at least FID, in between. So as intermediate mode, combining features of both DD and ID, FID is conceptually the most complex form. A natural conclusion might thus be that this mode of STR is characteristic for adult literature, but this is not at all the case. Consider this excerpt from a conversation between Humpty Dumpty and Alice in Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking Glass (1872), intended for a ±7 year old readership:

(2) “What a beautiful belt you've got on!” Alice suddenly remarked. (They had had quite enough of the subject of age, she thought: and if they really were to take turns in choosing subjects, it was her turn now).

The representation of Alice's thought in parentheses is a clear case of FID (“They had had enough,” not “We have had…”; “it was her turn,” not “it is my turn”). Or take the start of the first page in the most popular book in The Netherlands to read to toddlers (from about 3 years old), Jip and Janneke by Schmidt (1977; translation by Schmidt, 2008):

(3) Jip walked around the garden and he was so bored. But look, what did he see over there? A hole in the hedge. What's on the other side of the hedge, Jip wondered. A palace? A gate? A knight in armor? He sat down on the ground and looked through the hole. And what did he see? A little nose. And a little mouth. And two blue eyes.

The second sentence (what did he see…?) presents Jip as wondering about something in the past tense and third-person, and thus exhibits an FID-like character (the same applies to the repeated question later in the excerpt); it is his uncertainty, not the narrator's (virtually, rhetorically?) presenting a question to the reader/listener.2 Maier (2015, p. 359) also observes that “free indirect discourse is not at all uncommon in children's literature,” and provides several examples. The dates of publication of the examples above moreover indicate that it is not a very recent phenomenon either. Taken together, this clearly indicates that understanding this type of mixed perspective discourse is no problem for young children, and in view of the conceptual complexity of FID, an explanation is called for: The ability to understand FID must be a consequence of elementary cognitive and communicative abilities that children already have at their disposal at a very young age. This is the very general and basic issue that constitutes the topic of this paper: How can we explain the very existence of perspective taking in discourse? That is: What are the elementary conditions and causes that produce the possibility of (re)presenting, in communication, another person's speech and mind in the first place (and secondarily: in various ways)?

In order for an answer to such a question to count as a scientific explanation, it has to fulfill the general requirements for an explanation of a complex phenomenon: It must consist in a reduction of the phenomenon at hand to the combination and interaction of more basic principles, and at the same time demonstrate how this combination gives rise to the emergence of properties that are not present at the level of the basic principles themselves. In physics, for example, properties of fluids and solids can be reduced to the interaction of molecules under certain conditions, but no molecule is itself a fluid or solid—that is an emergent property at a higher level of organization of substances.

In our case, what is desired is a reduction of STR in discourse to the interaction of more elementary features of language (use) and communication, which by the same token shows how STR, in various manifestations, emerges as a special property of phenomena at the level of organization where these features are combined.

The general scientific importance of this question lies in the fact that STR is on the one hand a universal and commonly used feature of human communication, language in particular, and on the other hand a feature that has no analog in other communication systems in the animal kingdom. There is now solid evidence that several species of animals possess perspective taking cognitive abilities (cf. Krupenye and Call, 2019 for an overview). But while chimpanzees, scrub-jays, and some other species can represent various mental states of others cognitively, to themselves, none is capable of representing mental states of others in communication, to others. Thus we cannot fully explain the latter capacity of young and adult humans, by invoking the combination and interaction of cognitive perspective taking abilities and communication per se; we will have to dig deeper into basic theoretical concepts characterizing human communication and language, to see if the phenomenon of perspective taking in narrative discourse can be derived from them, and if so how, and what this implies for the analysis of actual viewpoint phenomena.

2. Depiction, sign theory, and quotation

A major step toward answering the question how STR is to be explained was taken with the analysis of “quotations as demonstrations” by Clark and Gerrig (1990). According to their proposal, a quotation does not describe a linguistic act, it depicts it—in the same way a stage actor's waving, or saying “Hello,” depicts a character's greeting. The reason why this can be considered an explanatory account is precisely that it shows how properties of quotations are reducible to and emerge from the application of a basic, non-linguistic technique of communication, namely depiction, to a specific kind of acts, namely linguistic ones.

In 2016, Clark published a version of this theory in which he emphasizes the generality of the depiction idea. It illustrates how the reduction side of explanations generally comes with a goal of unification. If depiction was only involved (as a causal factor) in quotation, the story would not really count as a good explanation. Truly basic principles are involved in several different kinds of complex emergent phenomena—the latter testifies, so to speak, to the fundamental character of the principles. Clark identifies five different research traditions dealing with instances of depiction:

- iconic gestures,

- facial gestures expressing emotion,

- quotations,

- full-scale demonstrations as teaching methods, of the “show-don't-tell”-type,

- the development of make-believe play in children.

He notices that none of the theories in each of these domains can be extended to the other ones, so there is no theoretical account of the basic depiction technique that they all share, and that is what he sets out to develop in his paper: Reduction, and with it unification, of a variety of phenomena to more basic principles. Here, I will concentrate on the combination of depiction with language, in order to argue two points: first, that the depiction approach can and should be (further) unified with the theory of signs, and second, how not just quotation, but also the possibility of different “mixed” forms of STR, with a variety of functions, emerges from such combinations.

In order to appreciate the implications of the conception of quotation as the depiction of a linguistic act, it is useful to start with the depiction of non-linguistic events. Consider the following two examples.

(4) My son and I noticed that the car has a-uh, a worry noise, kind of a “(low growling noise)” like when you used to put a baseball card in a-uh, the spokes of your bike (Clark, 2016, p. 332).

(5) When you need to move in a very measured way, then we looked for a maximally sharp, pointed sound. So when it is ták—pák—ták—pák—ták, then you can follow it well. When it hwuw h.wuw h.wuw h.wuw, then it becomes a much more rolling and sliding—uh—motion (Dutch therapist explaining the use of music in helping Parkinson patients control their movements, my translation).

In both cases, the speaker attempts to have their interlocutors imagine some sounds with particular characteristics in two ways that differ radically in the cognitive resources that they employ. On the one hand, the sounds are described, invoking the knowledge of certain symbols, i.e., words and constructions [“like when you put a baseball card in the spokes of your bike” in (4), and “maximally sharp, pointed sound” in (5)]. On the other hand, the sounds are depicted, i.e., simulated, which invokes the capacity to map relevant properties of the observed vocal sounds to properties of sounds in the intended domain of car noises and music, respectively. Thus, Clark's distinction between description and depiction is basically a special case of the distinction between symbolic and iconic communication, and symbols and icons are the subject matter of the theory of signs (Clark, 1996, p. 160; De Brabanter, 2017, pp. 232–234, and some other references cited there).3 In particular Keller's (1998) version of sign theory is useful here, because it focuses from the start on the use of signs as tools in cognition and communication, rather than on relations between signs and what is signified (the “object” in terms of Peirce's sign theory; cf. Hoopes, 1991). It is this basically pragmatic starting point of Keller's sign theory that makes it especially congenial to Clark's analysis of different methods of communication.4

Keller's general characterization of signs is that they consist in observable (and thereby cognitively highly accessible) phenomena that people use to infer something that is not observable. Different kinds of signs differ in the procedure and the cognitive resources allowing them to be used to this end. At the most elementary level, it is causal knowledge that allows us to infer, for example, the existence of fire from the observation of smoke, the presence of a dog from hearing barking, or the physical and/or mental condition (being tired or bored, depending on other knowledge) of a person from seeing them yawn. The observable phenomena involved only count as signs because of their being used to make certain inferences. These signs are symptoms; they are called signs because they are interpreted, but they have not been intentionally produced to be interpreted.

The second type of signs is icons. We may, for example, infer the presence of a dog on the premises from a picture of a dog on a fence, or the properties of a piece of music from someone's vocalizations, or the kosher/halal character of a food item from a crossed-out picture of a pig. In this case, what allows the observable phenomena to be interpreted in these various ways is our capacity to map (some of) the structure in the observed phenomena to another conceptual domain.5

Moreover, icons, unlike symptoms, are intentionally produced as signs. The capacity to imagine something, by mapping some structural properties of an observed, or at least cognitively highly accessible, event to another domain, is necessary for some observed phenomenon to count as an iconic sign, but it is not sufficient: When a certain configuration of clouds in the sky reminds you of a dog's head, for example, you don't take it as a sign indicating anything related to a dog (and if you do, and do so publicly, you actually commit yourself to beliefs about some intentional agent having made it in order to be interpreted). In other words, icons, unlike symptoms, are communicative signs.

Finally, signs of the third type, symbols, are also intended as signs. In their case, what allows them to be used as a basis for certain inferences is knowledge of rules, i.e., conventions in a particular community. For example, observing the configuration of lines 小心犬 allows you to infer you should be on guard for a dog, based on knowledge of a set of rules (known as “Mandarin”) for linking such configurations to interpretations, in the same way as observing the string Beware of the dog! licenses a similar inference, based on knowledge of another set of conventions (in this case “English”).6

An important component of Keller's sign theory is that different methods of signification can be “stacked.” For example, recall the observation of someone yawning as a sign, i.e., a symptom, (in particular circumstances) for the conclusion that this person is bored. Now imagine you see a friend in the audience of a lecture, the two of you make eye contact, and she then simulates a yawn (cf. Figure 1). Your observing this behavior will allow you to infer that she is bored, and that she intends to communicate this to you.

Figure 1. Simulated yawning (photo created by cookie_studio, www.freepik.com).

The use of a simulated yawn to communicate the idea of being bored combines two techniques of interpretation: First of all, it is iconic behavior, allowing you to think of yawning, and this is, secondly, a kind of behavior that allows you to infer that she is bored. Another possible path to the same ultimate communicative goal is for her to utter the sound (represented as) Yawn to you: First, it is symbolic behavior, allowing you to think of yawning (given your shared knowledge of English), and this is, secondly, a kind of behavior that allows you to infer that she is bored. The latter phenomenon is known as metonymy in linguistic semantics, which thus turns out to be reducible to and emerging from the combination of two more elementary notions: It is symbolic sign use exploiting the capacity to interpret symptoms. Analogously, metaphor—e.g., saying of a statement that it is “painful,” while it is not physically hurting—is analyzable as symbolic sign use exploiting the iconic technique (cf. Keller, 1998, pp. 156–157).

Depiction of language use, i.e., quotation, or DD, is just another instance of this kind of “stacking.” All events can be simulated, so verbal acts too. Consider the following (causally connected) examples. In January 2015, American pastor Larry Tomczak posted an article about Hollywood's “gay agenda,” as he perceived it.7 One thing he wrote was:

(6) Ellen DeGeneres celebrates her lesbianism and “marriage” in between appearances of guests like Taylor Swift to attract young girls.

With the quotation marks, Tomczak had indicated that he was depicting the use of the word marriage:8 He would not want to use this word for Ellen DeGeneres relationship himself, he considers it a “so-called” marriage. A few days later, DeGeneres responded in her talk show,9 starting with this:

(7) First of all, I'm not “married,” I'm married—that's all.

The first instance of the word married was spoken with a slightly different intonation than the rest, and accompanied by a gesture known as “air quotes” (cf. Figure 2), hence the representation within quotation marks in (7).

DeGeneres does not reproduce exactly what Tomczak had written [cf. “marriage” in (6) vs. “married” in (7)], but incorporates a depiction of the opinion represented in (6) into her own utterance, including a depiction of quotation marks, thereby mocking both the opinion and the way Tomczak had presented it.10

Clark's analysis of DD can thus be unified with Keller's pragmatic theory of signs. First of all, elementary depictions, like the ones in (4) and (5), are clearly instances of the second type of signs: icons. They allow you to communicate something through providing a simulation, in relevant respects, of what you want your addressee to think of.

Second, depictions of linguistic acts, like the ones in (6) and (7), are other instances of the possibility of “stacking” techniques of signification. In the case of metaphor, a speaker invokes your knowledge of conventional symbol meanings to make you infer a communicative intention beyond that on the basis of your iconic capacities. With DD, a speaker invokes your iconic capacities by simulating the use of an expression, to make you infer a communicative intention somehow related to the interpretation the expression would have in virtue of the conventional use of its elements. In (6) and (7), this relation is one of distancing, mocking, or irony (which is why the quotation marks are sometimes called “scare quotes” in such cases, but notice that it is actually a matter of interpretation; the quotation marks are the same as everywhere else). Another kind of effect occurs in cases like (8) and (9), analyzed as “fictive interaction” in Pascual (2014):11

(8) I prefer an “I do” ring over an “I will” ring.

(9) The trouble with cocaine is that the “…but I didn't inhale” excuse doesn't work.

The depicted expressions in (8) are characteristic for two different institutional procedures, viz. getting married and getting engaged, respectively. As Pascual (2014, pp. 65–69) notes, there is a kind of metonymy involved: It is causal knowledge that allows the interpretation from the expressions to the ideas of a wedding ring and an engagement ring, while the depiction has the additional rhetorical advantage of foregrounding the commitments undertaken by the participants in these different procedures. Analogously, the expression “but I didn't inhale,” famously used by US president Clinton to soften the effects of the disclosure of his drug use as a youth, is used in (9) to characterize a particular kind of excuse.12 Thus, this type of cases illustrates the use of multiple applications of stacking of methods of signification: iconic simulation—of a symbolic act—causally linked, as typical, to a particular type of situations.

Thirdly, Keller's and Clark's theories both insist that a simulation must be recognized as different from what it simulates in order for an icon/depiction to count as one (Clark, 2016, p. 327; Keller, 1998, pp. 144–145). If an observer does not see a behavior as in Figure 1 as different from an actual yawn, he cannot take it as a simulation, not as intentionally produced, and it will not count as communication. Similarly, if a listener does not recognize a stretch of language as depicted, he will attribute it to the actual speaker, with potentially dramatic consequences; for example, if a listener does not hear an ironical remark as different from a serious statement, he may not take it as irony, and the sender will be taken as communicating a very different message.13

All in all, we now have a theoretical account (of the “reduction and emergence” type) of the ability to evoke an image of speech by others in one's communicative actions: Once we have language, so to speak, it is unavoidable, given the elementary capacity to use simulation for communication, that language use can and will be simulated for communicative purposes as well. This ability is a consequence of a specific combination of elementary methods of sign use, alongside other emergent phenomena in pragmatics and semantics, such as metaphor and metonymy. The pragmatic theory of signs here functions as the unifying conceptual framework.

3. Depiction, in utterances, of language use

The next two steps in the development of a full theoretical account of STR come specifically from Clark and Gerrig's (1990) analysis of depiction in language use (partly in combination with Goffman's (1981) analysis of the range of possible “hearer” roles). The first point is the actual demonstration that perspective taking is an emergent phenomenon—a result of the interaction between elementary phenomena each of which does not exhibit perspective taking itself. The second is an exploration of consequences that follow immediately from the first: What properties of STR phenomena does this theoretical approach account for?

3.1. Depiction, imagined acts, and perspective taking

Every depiction comprises an observable scene that is intentionally produced by a communicator in order to allow an addressee to imagine a distal scene.14 When the distal scene comprises an action, then the communicative event has the character of a staged play: We see and hear someone perform some act, and we use this observed behavior to imagine an act of a character at another time and place.15

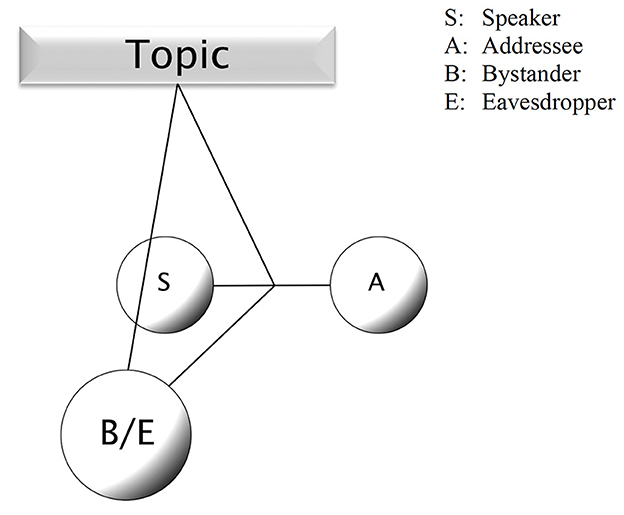

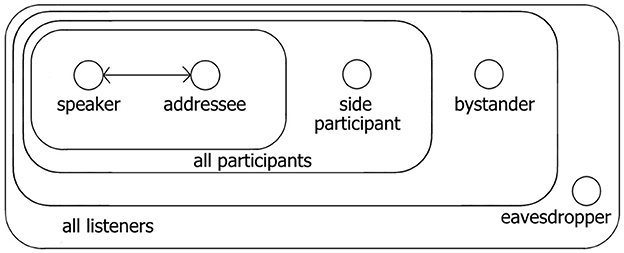

It is actually quite easy and natural for people to imagine distal scenes involving linguistic acts. The background is that conversations regularly take place in groups and in public spaces, so that we all have ample experience observing conversations. Goffman (1981, p. 131ff.) demonstrates that the dichotomy of “speaker” and “hearer” is far too simple to do justice to the dynamics of actual talk (cf. Levinson, 1988 on Goffman's “participation framework”). In particular, we have to distinguish various kinds of “hearer”-roles (cf. Figure 3).

Figure 3. Language experience: Various roles (taken from Clark, 1996, p. 14).

Side participants are also intended receivers of the speaker's message, besides the person who is directly addressed; they may under certain conditions also take the turn in the conversation. A speaker will often also take bystanders into account in formulating his contributions. And people overhearing a conversation without any of the participants being aware of them may also acquire information from it about whatever the topic of the conversation is, and about the positions of various participants. That is just the way language is: a public tool for communication (within the group sharing the conventions). Given its public nature, every member of a language community has not only experience as speaker and addressee, but also as an observer of communicative interaction, indicated schematically in Figure 4.

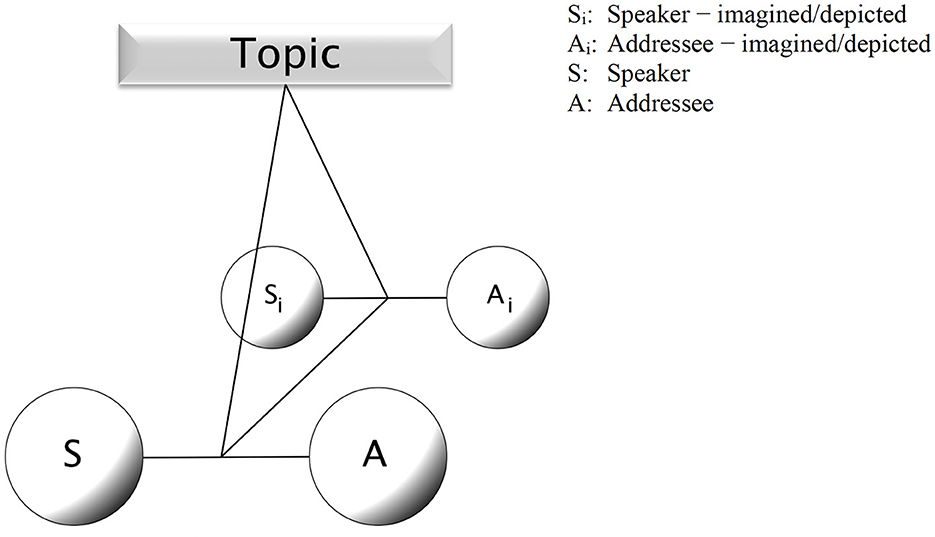

Given the capacity for iconic simulation, listeners can also imagine a conversation when someone depicts it for them. In that case, the cognitive constellation is slightly more complex (there is a speaker who presents a conversation for her addressee to be observed), as indicated in Figure 5.

Prompted by the speaker's depiction, the addressee imagines a conversation, and in the process becomes an eavesdropper to that conversation. In such a case, the relationship between speaker and addressee is characterized by the logic of the roles of actor in and audience at a staged play, respectively—which is why Clark (2016, p. 330) can use a set of “principles from the theater” as a basis for his “staging theory” of depictions.16

It is this situation that inevitably involves perspective taking. Members of the audience at a play observe, from their physical viewpoint, the stage and the actors, and imagine depicted characters—this entails the construction of the viewpoints of these characters in their own world, which is likewise imagined. Consider Figure 6.

The audience sees the actors looking at the ceiling of the theater and imagines Romeo and Juliet looking at the night sky. Whenever an observed act is interpreted as a depiction, i.e., used to imagine some act in a displaced world, the emergent distinction between an observable and a distal scene also implies a distinction between perspectives, as acts imply people performing them.

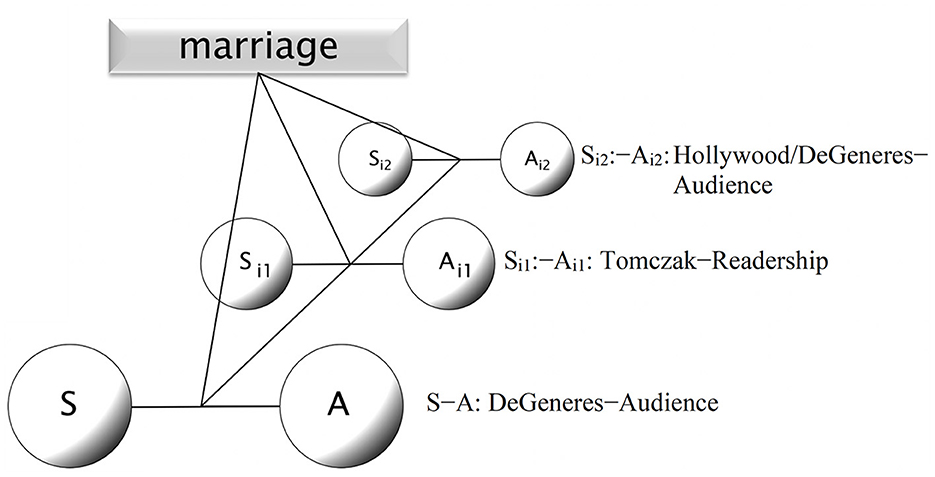

Moreover, this consequence has recursive potential. Depicted, imagined characters are of course capable of depicting linguistic acts (stage actions) in their own imagined world. We have in fact already seen an instance of this in example (7), produced by Ellen DeGeneres. Consider Figure 7. Embedded in the utterance to her audience, DeGeneres depicts Larry Tomczak's opinion, as himself depicting the view of Hollywood (including herself) on the institution of marriage, thus evoking an ironical variety of perspectives on the concept.17

Thus we have recursion of perspectives, without necessarily any grammatical marking in the language being used.18

It is useful to explicitly reiterate the point that depiction by itself does not necessarily produce perspective taking: The depictions of noise in (4) and of music in (5) involve a distinction between observed and distal scenes, but not necessarily a distinction between associated perspectives. The same is true for the observation of conversation per se (cf. Figure 4): it is not impossible to differentiate the perspectives of interlocutors and others, but we don't have to, and the default situation is that we don't (as long as there is no need).19 Perspective taking is truly an emergent complex phenomenon, an effect of a specific combination of elementary phenomena, viz. (a) the depiction of (b) acts, in particular communicative acts. This combination results in the constellation indicated in Figure 5, with depicting/imagining actions by Speaker and Addressee on the one hand, and depicted/imagined actions of others (in a distal scene) on the other.

3.2. Combining depiction and description: Deconstructing (free) indirect discourse

Depictions do not only occur alongside verbal utterances, but also as integral components of them, as we have already seen. In (4), the vocal depiction of some noise occurs in the slot of the complement of an indefinite article; the first depiction of music in (5) functions as a predicate nominal, and the second one as a verb phrase; the fictive interaction cases in (8) and (9) are prenominal attributive modifiers. Many other cases observed and analyzed in Clark (2016) are of this type, leading him to conclude: “Everyday discourse is a mix of descriptions, depictions, and composites of the two” (p. 343), and it is especially because of the composites that depiction “ought to be included in accounts of language processing” (p. 325). In fact, all the evidence clearly shows that the processing system in everyday language use does not handle the linguistic, descriptive part of utterances separately, to combine the results with those of processing any para-linguistic and non-linguistic components.20 People must be working with a single system for processing communicative acts, which has simultaneous access to all relevant resources—causal knowledge, iconic structure mapping, knowledge of conventions (“rules of the language”)—and immediately integrates these as soon as it becomes relevant. I actually find this picture more sensible than one with a separate linguistic processing system, precisely because the function of the processing system is to make sense of an interlocutor's communicative actions, and it has evolved in the context of this kind of task (cf. Enfield, 2015; Verhagen, 2021a).

The insight that everyday utterances are basically composite, is, of course, only a very general constraint on theories of processing. As Clark acknowledges, it does not by itself tell us how the processing system performs the task of integrating observed utterances and various cognitive resources. However, it does have the consequence that depictions of language use, being just another kind of depiction, can be integral parts of other utterances, as the examples in (6)–(9) confirm, and this in itself already has implications, some of which provide more elements of an explanatory theoretical account (again, of the “reduction and emergence” type) for a range of more specific phenomena, including free indirect discourse (and “mixed” modes of STR in general), the meaningful interaction of multiple voices in a single text, and the way they relate to conventional properties of languages.

To start, the insight that depictions, in particular depictions of language use, can be built into linguistic utterances as components (recall an “I do” ring, etc.), provides a general characterization of the nature of a “mixed” form of STR like free indirect discourse: Some parts of a single grammatical utterance are interpretable as depictions of what a character says or thinks, while other parts are taken as descriptive. The very possibility of the existence of something like FID is thus a direct consequence of the possibility to build depiction into a verbal utterance, and not dependent on the existence of both direct and indirect discourse in a language. So from this perspective, the label FID is actually a bit of a misnomer: It does not reflect the actual underlying factors that explain its existence. We are not really dealing with a “mixture” of direct and indirect discourse, and forms of expression like FID also exist in languages that do not have grammatical constructions characterizing indirect discourse in European languages, such as formally distinguishable constructions for complementation/subordination—and such languages are not at all rare (cf. Evans, 2013).

But the consequences of the analysis of FID-like phenomena as emergent from the interaction between iconic and symbolic language use, are actually somewhat deeper, more radical. Consider the start of the story of Jip and Janneke again, repeated here for convenience:

(3) Jip walked around the garden and he was so bored. But look, what did he see over there? A hole in the hedge. What's on the other side of the hedge, Jip wondered. A palace? A gate? A knight in armor? He sat down on the ground and looked through the hole. And what did he see? A little nose. And a little mouth. And two blue eyes.

We assigned the two questions “what did he see…?” an FID-like status because of the combination of main clause syntax with third person and past tense. The question “What's on the other side of the hedge,” because of its apparent present tense, is to be considered DD, as indicated by the italics in the translation (the Dutch original contains no italics at all). For many other parts of the text, it is impossible to choose between DD and FID, because of the lack of pronouns and tense. All the independent nominal phrases following a question (“A hole in the hedge” through “And two blue eyes” at the end) could be seen as DD or as FID. In view of the italics, the translator considered three of them DD, possibly because of the question marks. But there is actually no reason to consider them, in terms of type of STR, any different from the other phrases that constitute answers. One might be tempted to say that the text is quite ambiguous, and/or that the distinction between FID and DD is sometimes hard to make, but the text is not really ambiguous at all. For the story to progress, such choices do not really matter; the point is that the answers to Jip's questions—at one point a number of possible answers that he considers—become shared knowledge, common ground, of the narrator, the readers/listeners, and Jip. Other stories, as we will see, can display more complexity in the relationships between different perspectives, but the point here is that the traditional STR distinctions are not really helpful in explicating the way the text is interpreted.

All of the phrases involved contain depictions of what Jip is experiencing while exploring the hole in the hedge. The “so bored” in the first sentence may also well be taken as a depiction of Jip's mood, especially because of the intensifying so. Taking depiction as the crucial notion, we can analyze perspectivization in the text in terms of a single distinction, as indicated with depiction marked as gray background in (3)′ (dropping the italics of the translation):

(3) Jip walked around the garden and he was so bored. But look, what did he see over there? A hole in the hedge. What's on the other side of the hedge, Jip wondered. A palace? A gate? A knight in armor? He sat down on the ground and looked through the hole. And what did he see? A little nose. And a little mouth. And two blue eyes.

The picture that we get in this way is both more simple, more complete and interpretively more adequate than one in terms of distinctions between narration, DD, and FID. I consider this a good reason to conclude that these distinctions can and should be dispensed with, at least as primitive, explanatory notions.

In fact, the same holds for the distinction between FID and ID. Van Duijn and Verhagen (2018) discuss the following example, from a journalistic story, told in the present tense, analyzed in Sanders (2010) (I only provide the English translation here):

(10) The family doctor, who at Carla's request arrives within moments, sees a full-term infant, a girl well over seven pounds. Later it is determined that the child died weeks before, but did live. Carla thinks that Etta is the mother. Who else could the baby belong to?

First of all, notice that the question in the last sentence could both be seen as DD and as FID here as well. But the sentence preceding it, is especially interesting. As Carla's conjecture about the identity of the dead baby's mother is represented in a complement clause, it satisfies the criterion for ID. But it is definitely possible, and in my view even plausible, to interpret the entire sentence, specifically including the matrix predicate, as a depiction of what Carla had said. We imagine a conversation following the discovery of the baby's body and the arrival of the family doctor: He reports what he sees and the question arises (and is likely to be asked) who the mother could be, and Carla says: “I think that Etta is the mother.” In that case, we would have to consider the sentence reporting it in (10) as FID. But in terms of the present theory, the real point is that we are linguistically free, so to speak, to treat the matrix predicate as depiction or as description—without it making a big difference, in this case, for the idea that is being communicated: It becomes common ground to journalist, readership, and participants in the event that this is what Carla thinks. In this reading, the only linguistic items that are not used depictively are the proper name Carla and the third person marking on the verb.

The possibility to read the matrix clause of a complementation construction in a suitable context as depiction is more general. Consider the following excerpt from (the translation of) the novel The Discovery of Heaven by Dutch author Harry Mulisch; it is the end of a report on a discussion between a number of politicians while they are sailing.

(11) Onno had gotten up and said that he felt superfluous here. They agreed that for the time being he would say nothing to the others; God willing, they might have solved the problem before they arrived in Stavoren. Onno promised that he would not jump ship in Enkhuizen.

It is very well possible to attribute the qualification “promise” in the last sentence to Onno himself, imagining him as having said “I promise that I will not jump ship in Enkhuizen,” so with only the grammatical third person and tense characteristics in both matrix and complement clause as linguistic markers indicating that the reported event is not part of the communicative situation. Here too, the plausibility of such a reading is enhanced by the fact that the immediately preceding sentence is largely depiction as well, apart from pronouns and tense (this is FID in the traditional sense, without a matrix clause). Notice that the plausibility of a depictive reading of the last matrix clause in (11) might have been even more enhanced if the subject had not been a proper name, but a pronoun (he), i.e., an element that is minimally different from the first person (I) that Onno would use himself.21 So several instances of complementation that would because of their grammatical form be classified as ID, may in fact also be classifiable as FID, when elements of the matrix clause, in particular the predicate, turn out to be plausibly interpretable as depictive. Obviously, this undermines the usefulness of categorization of perspective taking in terms of distinguishing between DD, FID, and ID; an analysis in terms of the possibility/plausibility of directly interpreting each linguistic element of an utterance depictively or descriptively in itself provides a sufficient basis for analyzing the perspectives involved, without a need for “intermediate” categories of STR.

3.3. Depiction in composite utterances: A (more) strictly linguistic approach

We have seen that several sentences satisfying the criteria for ID, in particular because of the presence of a complement taking matrix predicate, can also be analyzed as FID (including their matrix clauses). But even other instances of ID may contain depicted elements. In the first sentence of (11), it is not sensible to interpret the matrix predicate say as depictive (unlike the matrix predicate promise in the last sentence). But notice the interpretation of the deictic local adverb here in the complement clause; it takes the narrated event, in particular Onno's perspective, as its deictic center. So ID apparently may contain depictive components as well. This has in fact been observed in the literature several times, and it is not hard to find other examples, such as the one in (12) (see Section 4 for a discussion of the larger passage that this is part of):

(12) … the coach called—it was a Saturday in December—to tell them Vermeer was the most hopeless pupil he'd ever come across …22

The main character here is a young boy, whose first name is Phinus. But it is customary for coaches of soccer teams to refer to the team members with their last name. The use of Vermeer is thus a depiction of the coach's message. The assessment of the degree of the boy's ineptitude (“most hopeless,” “ever”) is also naturally taken as depictive. So Fludernik (2005, p. 562), in an encyclopedia entry, rightly observes: “Although indirect speech is supposed to be untainted by characters' expressivity, there are in fact numerous cases of such mimicry by the narratorial discourse,” referring to her own empirical research (Fludernik, 1993) as well as other work. Similarly, Dutch narratologists Van Boven and Dorleijn (2015) observe in the most recent edition of their textbook that elements of character subjectivity may occur in ID, to which they then add: “so in the narrator's text.” Thus, neither does away with the category of ID, which is understandable as it would come down to giving up a tool to talk about differences in the organization of perspectives at all.

A different approach is taken in one of the “classic” and highly influential works on stylistics, including STR: Leech and Short (2007[1981]). Unlike “many writers on speech presentation” (their own words), they consider the presence of an element of character subjectivity in a complement clause sufficient to consider it a member of the FID category. They invoke the idea of “family resemblance” to justify that no single specific feature mentioned in the definition of the category is criterial for FID, not even main clause syntax (Leech and Short, 2007[1981], pp. 264-267). It seems fair to say that in this approach, the label FID basically means any instance of mixing of a character's and a narrator's words. But Leech and Short do not do away with ID either; when a complement to a matrix clause does not contain any elements that have to be considered a character's words, then the reported discourse counts as ID, also in their approach. So this seems to be a common denominator, despite the differences.23

However, in a depiction/description approach, a different analysis is possible, and in fact plausible. Consider the sentences listed in (13), which contain the finite complement clauses in (11) and (12):

(13)a Onno had gotten up and said that he felt superfluous here.

(13)b They agreed that for the time being he would say nothing to the others […].

(13)c Onno promised that he would not jump ship in Enkhuizen.

(13)d the coach called […] to tell them Vermeer was the most hopeless pupil he'd ever come across […]

I marked several elements that minimally have to be considered as depictions in order to arrive at a coherent and sensible interpretation. But as observed in Section 3.3, much more of (13)c, including the matrix predicate, may be interpreted as depiction as well: Imagine Onno having said “I promise that I will not jump ship in Enkhuizen.” In principle, all of the lexical content of the complement clauses may well be read depictively (“[I] feel[+PAST] superfluous here,” “for the time being, [I] will[+PAST] say nothing to the others,” etc.). In (13)a and b it does not make sense to interpret the matrix predicates say and agree as depictive, but in the case of (13)d such a reading, analogous to (13)c and (10), is not at all implausible; imagine the coach saying: “I'm calling to tell you Vermeer is the most hopeless […].” At the same time, there are no grounds, formal or interpretive, to enforce such an interpretation; it is equally defensible to read this sentence completely as a description of what happened, and thus to attribute it to the narrator. In other words: many elements do not constrain their interpretation in a specific way; they may be called linguistically “neutral,” or “free,” as to their being taken as depiction or description. Besides these, there are items that do function as cues for distinguishing depiction from description, though additional information is always necessary; for example:

• In (13)a: here is a deictic adverb, so the reader should find a deictic anchor; Onno is available, this link makes complete sense, and other ones don't; so the use of here depicts Onno's utterance.

• In (13)a and c: Onno and he are third person items, which are not normally used to refer to oneself (in this language/culture), so these expressions are not to be taken as part of a depiction of Onno's speech act; the past tense is used (in this language) for indexing a situation detached from the communicative situation, so not to be taken as a part of a depiction of Onno's speech act (cf. Verhagen, 2019).24 This logic can be applied to each of the sentences in (13), and, of course, to past tense, third person stories in general. 25

• In (13)d: Vermeer is a last name; the referent is a young boy (contextual knowledge); children are normally called by their first name, but soccer coaches use last names (cultural knowledge); the soccer coach is available; so the use of Vermeer depicts the soccer coach's utterance.

So different cues “work” in different directions. Given their conventional function in the language, some point to a depictive interpretation when part of reported discourse, while others point to a non-depictive one—and many items do not point in any particular direction at all and may in principle be taken in either way. The construction of a matrix predicate with a complement clause may certainly be used to introduce reported discourse, and given this usage, it may also be taken as a cue, but it is only a weak one. The matrix clause always indicates some perspective that the embedded eventuality is linked to (Verhagen, 2005, Ch. 3), but this does not mean that it is always descriptive. That is largely dependent on its lexical content. People can characterize their own speech acts in certain ways (I promise, I think, I argue, etc.), and these acts can be partially depicted, as we have seen (He promised, etc.).

Note that it was not necessary, in any of these explications of the interpretation of perspective taking, to use the categories of ID or FID. The elementary concepts that we need are the universal ones of depiction and description—iconic and symbolic signaling, respectively—on the one hand, and the conventional functions of linguistic items in a language on the other.

The important difference lies in the concepts involved. The traditional “types-of-STR”-approach treats the object of analysis as basically all text, i.e., language use, and attempts to characterize differences in terms of who is responsible for which elements of the language being used. The depiction-description approach treats the object of analysis as consisting of communicative signals of fundamentally different kinds: icons, i.e., simulations on the one hand, and symbols on the other. What makes the object of analysis appear as “all text,” especially in written/printed genres, is that the simulations involve simulations of linguistic acts, and we may thus not directly notice their being performed. In the theater and in everyday interactions, their nature as acts is clearer, often also because of multimodality. But texts do not fundamentally work differently; when being used and interpreted, they are also manifestations of communicative action. In the “all text” approach to STR, it is natural to speak of a “cline” from DD to ID, but given the fundamental difference between iconic and symbolic signaling, there can be no cline from depiction to description. Certainly, there may be a lot of variation in the degree of plausibility and (un)certainty with which a particular piece of an utterance is assigned a depictive or descriptive status; in fact, this situation can be communicatively exploited (Section 4). But the distinction between the concepts is not a gradual one.

4. An emergent asymmetry and its advantages

4.1. Absolute indirect discourse does not exist

I have argued that the very existence of perspective taking is an emergent phenomenon in acts comprising depictions of acts (including linguistic ones). But there is yet another consequence that arises from the specific possibility of incorporating a simulation of symbolic communication (a depiction of language use) in a symbolic action (a linguistic utterance). Put abstractly, it comes down to the following. The fact that both depictions and descriptions consist of linguistic material produces a kind of systematic, inescapable ambiguity. Given a linguistic utterance, there is no way of telling, from the material used alone, whether it is to be taken as a description or a depiction by the present, actual speaker (in the case of stories: the narrator). And given that partial depictions can be components of utterances, the same ambiguity in principle also exists for parts of utterances.

This has a peculiar consequence showing a fundamental theoretical incompatibility of the “all text” approach and the depiction approach: “Absolute” ID, in the sense of a conventional linguistic construction that marks some piece of language as only a description by the actual speaker, cannot exist. From an interpretive perspective, no linguistic act under consideration is inherently constrained to a descriptive interpretation: Any stretch of speech/writing can always be claimed to be interpretable as a depiction of (a part of) another speaker's utterance.

Depiction is characterized in opposition to description, and DD is characterized in opposition to ID, so it might seem natural to identify ID, as the opposite of DD-as-depiction, with description. As a matter of fact, this is even stated in so many words in Clark and Gerrig (1990, p. 787). In a discussion of the nature of FID (which they call “free indirect quotation”), contrasting it with both DD (“direct quotation”) and ID (“indirect quotation”), they write: “Free indirect quotations demonstrate aspects of things that indirect quotations only describe.” However, my claim is that the idea that ID clauses “only describe,” must be false: 26 There can be no such thing as a linguistic utterance that, as a matter of principle, i.e., because of its grammatical and lexical make-up, can only be used and interpreted as description, the argument being that any type of act can be simulated, including linguistic acts. In other words, the idea of a conventional tool indexing description, is an impossible, self-contradictory notion.

There is an asymmetry here, as languages can and do evolve conventional tools for indexing depiction (cf. McGregor, 1997, pp. 256–258). In writing, quotation marks are of course the best known case, and in (spoken) language we have various kinds of “quotative” markers and constructions (such as go and like in colloquial English). And there may be other cues, like a change of voice quality or gaze, suggesting to an interpreter that a relevant piece of language is to be taken as depiction rather than description. But in the end, it is always an interpretive decision how things are actually taken. Moreover, dedicated conventional tools for indexing depiction such as quotation marks and quotatives are not themselves inherently descriptive; again: because no linguistic item can be. Such markers enforce a “split” between two scenes, one functioning as a trigger to imagine the other, but the utterance of which the markers are a part may itself well be interpreted as depiction (recall Ellen DeGeneres depicting the use of quotation marks in (7)).

In short, the fundamental asymmetry that the depiction theory of STR and perspective taking entails is this: Some complete utterances are only interpretable as simulations when indexed by a device such as quotation marks, quotative construction, or the like, but there are no utterances that are only interpretable as descriptions, i.e., without any element being interpretable as depictive. Apart from DD (only depiction), all other forms of STR are interpretable as mixtures of description and depiction, in various ratios.

On the one hand, this situation allows for the kind of abuse observed in footnote 13: the speaker of an insult claiming their utterance to have been intended ironically.27 On the other hand, it also allows for great interpretive flexibility that can be exploited in narratives. When there is a lot of freedom in interpreting pieces of an utterance as depictive or descriptive, this offers opportunities for constructing various different, complex “networks” of relationships between perspectives with the same, relatively simple, set of tools.

4.2. Exploiting depiction: Different “networks” of perspectives

Precisely the common possibility of interpreting a stretch of language both as depiction and as description offers opportunities for developing different relationships between the perspectives of different relevant “subjects of consciousness” in a story. Certain constellations of linguistic cues indicate that a distinction is to be made between an imagined scene and one in which this scene is being depicted (cf. Section 3.3). But it is dependent on other factors, in particular knowledge about the characters that play a role in the passage involved, how one constructs the distinction, and relates it to the subjects involved. The systematic ambiguity also implies that there need not be a single possible, or even optimal solution to this interpretive task.

For a first example, consider the larger excerpt from which (1) was taken:

(14) She rested her fork on the edge of her plate and he noticed for the first time that she was wearing no wedding ring. He immediately changed the subject.

“Are you in one of the services?” he said.

No, she said, she was teaching literature and history in St. Anne's High School for Girls. They had been evacuated from London to a mansion called Clifton Court. Did he know it?

“I see it from the air. Sounds pretty dull though. Still, fun and gossip in the common room I've no doubt.”

No, she was free of all that, she said, thank God. She'd managed to buy a small cottage of her own.

“Sounds cozy. Perhaps I might invite myself over some time?”

“The garden's a mass of weeds.”

This enigmatic answer of hers had the effect of changing his interest into a certain excitement.

What we have here is a representation of a conversation, taking place between a male and a female character in a story, over dinner; they have just made each other's acquaintance. The excerpt starts with the report that he noticed for the first time that she was wearing no wedding ring and changed the subject. As we noted, the first part of the excerpt provides examples of the three main categories of STR. But the distribution of complete depiction (DD) and partial depiction (“FID”) is unbalanced, and we take this into account in constructing our interpretation, as well as other information, in particular, information about his mental processes (notice the reasoning implicit in the negation in the complement clause that she was wearing no wedding ring (cf. footnote 1), and the decision implied in the causal relation between this sentence and the next). The representation of the conversation alternates between complete depiction for his turns and partial depiction for hers. Her contributions are depicted, but in a way that is different from his. The depiction is partial, with the past tense and third person markers explicitly indicating its being depicted from another scene. In this case, given the systematicity of the unbalanced distribution and other information, it makes sense to understand her contributions in this excerpt as being presented “through” the male character. It is at the point where her answer is “enigmatic” (i.e., for him) that the partial depiction ends. A good way of making sense of this, given the reading of the text so far, is precisely that this reflects his being incapable of reliably interpreting the utterance; the only way of representing it then is to “just give the words” as uttered.

Notice that it is not at all implausible, especially at this point, to also consider all depictions, including hers, as being done from the scene of narration as well. It is completely natural to read the text here in such a way that the enigmatic character of her statement at the end becomes common ground for both the main character, the reader, and the narrator. In this respect, this excerpt does not differ essentially from the Jip and Janneke excerpt in (3) (see Section 3.3). A much more “radical” illustration of something similar can be seen in the following excerpt from Renate Dorrestein's novel Zonder genade (2001), translated into English by Hester Velmans as Without mercy (2003). The novel as a whole consists of a number of frame stories. In one of these, main character Phinus Vermeer recalls, in much detail, a conversation with his wife about the lack of exercise of their son Jem. This recollection in turn triggers another reminiscence of his own failed attempt as a boy to become a soccer player. It was clear from the start that he did not have the talent at all, but he kept telling stories about great performances to the two aunts who were raising him and had paid for the expensive outfit; but this became more and more hard going:

(15) The flawless penalty kicks were fast becoming a millstone around his neck, but he couldn't backtrack out of the first division now: the aunts believed in him. How sorry they were that they had to work on Wednesday afternoons!

The last sentence is an exclamative-how construction, and the ones who are depicted as exclaiming are the aunts. This depiction is done by Phinus, within a story about his own youth, triggered by a story on his son's youth—recollections depicted as Phinus' storytelling by the narrator. Shortly after this, we go a level deeper:

(16) Until the day the coach called—it was a Saturday in December—to tell them Vermeer was the most hopeless pupil he'd ever come across and, believe him, he'd had his share of stone-blind, bungling, gormless misfits in his day. His own life would be personally much improved if he were to be relieved of having to coach this exceptional basket case.

As noted before in connection with the first sentence [see the discussion of (12) in Section 3.3], it is the coach who designates Phinus by his last name “Vermeer,” and the same is true for the qualification “stone-blind, bungling, gormless misfits” to indicate a region on the scale of soccer talent. This sentence and the next one look like FID, but Phinus himself was not the addressee of the coach's message—the aunt answering the phone was, who presumably reported it to the young Phinus, whose older self now imagines it as part of a reminiscence embedded in a frame story. However, while we can reconstruct such connections and might on that basis try to compute whose perspectives are exactly mixed in which clauses, the real point in understanding the text here is simply that it contains the depiction of a judgment on Phinus' total failure as a soccer player, which in this way becomes clear (common ground) for everyone involved: the trainer, the aunts, Phinus as an adult, and the reader.28

Such an effect of modification of the common ground of readers and characters is certainly not the only one that can be achieved by mixing depiction and description. The following excerpt from Dickens' Bleak House (1852-53), and Womack's (2011) discussion of it are particularly well suited to illustrate this.

(17) Sir Leicester […] regards the Court of Chancery, even if it should involve an occasional delay of justice and a trifling amount of confusion, as a something, devised in conjunction with a variety of other somethings, by the perfection of human wisdom, for the eternal settlement (humanly speaking) of everything. And he is upon the whole of a fixed opinion, that to give the sanction of his countenance to any complaints respecting it, would be to encourage some person in the lower classes to rise up somewhere …

Womack (2011, pp. 66–67) insightfully comments:

Formally, this gives Sir Leicester's views in indirect discourse, telling us […] how he “regards” the Court, what his “fixed opinion” is. And sometimes it gives them in what may be imagined as the words he would use. For example, the acknowledgment that Chancery may “involve an occasional delay of justice and a trifling amount of confusion” is effectively a fragment of direct speech. The elevated viewpoint from which the Court's monstrous inefficiency looks like a minor imperfection is clearly Sir Leicester's.

Womack thus notices, in the traditional terminology of DD and ID, that several components of Dickens' text have a depictive character, embedded in a description. We may even see more of them than Womack lists here; for example, the matrix predicate “be upon the whole of a fixed opinion” may well be attributed to Sir Leicester as well [cf. the discussion of (10) and (11) in Section 3.2]. What is especially interesting, however, is the next step in Womack's analysis:

[…] the grandiose build up, through the regarding and the parenthetic clause, leads you to expect an idea, but then, instead, you get “a something” conjoined with “other somethings” for the settlement of “everything.” In the sudden drop into total vagueness, and especially in the comic plural form of “something,” the reader detects, not Sir Leicester's consciousness, but a mocking authorial consciousness of him. In exactly the moment that the impressive rhythm of the sentence assigns it to the authorship of Sir Leicester, the choice of noun announces the intervention of a second author, aggressively unimpressed. It is what Bakhtin calls “doublevoiced discourse.” Two distinct speakers are heard in the same words, one signaled by the syntax, the other by the vocabulary.29

Indeed, the depiction of Sir Leicester's view of the Court of Chancery here has a strong effect of distancing, mocking, and the partial nature of the depiction here definitely contributes to this, much in the same way as the use of contentless vocalizations like blah blah blah spoken with, for example, a mincing pronunciation, is a strong mocking device. This effect, of the reader being invited to reject a depicted opinion, is quite different from what we saw in the previous examples in this section, but the mechanism of partial depiction embedded in (some) descriptive discourse is essentially the same; depending on the way the depiction, with the multiplicity of perspectives that comes with it, is connected to other pieces of knowledge, in particular those based in the text involved, very different effects may result.

At the end of the last piece quoted from Womack (2011), he relates his analysis to Bakhtin's notion of doublevoiced discourse. Indeed, I want to claim that the depiction theory of STR precisely provides a basis for explaining the fact that discourse so generally manifests multiple “voices,” i.e., that this appears to be a general condition of language. On the very abstract level of language in general, the idea that it always re-uses words of others, is, in my view, basically the same as the idea that all present day conventions of a linguistic community are the result of many recurrent instances of language use, on which usage based linguists these days all agree. But the idea of doublevoiced (and multivoiced) specific discourses, in which the interaction of several subjects, communicating and being represented, create significant interpretive effects, can find an explanatory basis in the universal mechanism of simulation, applied to language use. As soon as there is symbolic communication, i.e., language, it can be simulated, and doublevoicedness emerges immediately. Thus, it is no wonder that this is a common feature of conversational discourse (Tannen, 1989), giving rise to patterns of systematic combinatoriality (what Du Bois, 2014 calls “dialogic syntax”), not only of literature.30

5. Conclusion

In this paper, I have proposed an explanation of the existence of perspective taking in terms of the application of a universal method of communication, viz. simulation, to linguistic acts. The basis for this explanation is Clark's theory of depiction as a method of communication, with a few minor amendments.

On the one hand, this theory can be unified with the theory of signs, in particular in the version developed in Keller (1998). Perspective differentiation results from the iconic simulation of acts, linguistic acts in particular. On the other hand, the depiction theory contains (at least) one additional specific claim, viz. that depictions can be integral components of utterances. This allows for the explanation of the existence of variation in the representation of reported discourse and consequently in the perspectives associated with them.

The proposed approach allows one to analyze known specific phenomena of perspective taking directly in terms of the linguistic elements involved on the one hand, and the general distinction between depiction and description on the other hand, without a need for notions like Indirect Discourse and Free Indirect Discourse, which are notoriously hard to define, and on which there is no general consensus among scholars.

While the approach provides an explanatory conceptual framework, it does not do more than that. In other words, given this framework, all the research on actual perspective taking phenomena in different languages, in specific texts, through time, and so on, is still to be done. There are many results from previous research, carried out in other frameworks and formulated in other terms, that can, with any luck, be re-analyzed in terms of the present theory. But at the same time, the framework will hopefully also make it possible to “see” and analyze phenomena that were so far not included in the domain of perspective taking research in an insightful way. There are some reasons to believe that this is indeed the case.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Acknowledgments

I want to thank the reviewers of previous versions of this paper for helpful comments and suggestions. They have contributed significantly to sharpening both the form and content of my argument, and clarifying the structure of the final version. Naturally, the responsibility for claims made here is mine.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer, SS, declared a past collaboration with the author AV to the handling editor.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^For some scholars, this might not count as ID because notice is a verb of perception, taken as a marker of “focalization” (Genette, 1980) rather than speaking/thinking. However, the negation in the complement cancels a possibility or expectation (the absence of a something is itself not perceivable), so this clause reports a thought process (Van Duijn and Verhagen, 2018, pp. 405/6). This case may thus well be seen as a grammatical instance of the “seeing is understanding” metaphor. In section 4.2, I will argue that it also illustrates that analyses in terms of the theory to be developed in this paper are superior to traditional ones.

2. ^It has the characteristics of “fictive interaction” [Pascual, 2014; cf. Section 2, examples (8) and (9)], exploiting the conversation frame to evoke the idea of cognitive uncertainty (“What do I see over there?”), and at the same time, with the past tense and third person markers, of FID.

3. ^Davidson (2015) also treats Clark and Gerrig's (1990) proposal as an instance of the general technique of iconicity, justifying the introduction of a special operator in formal representations of various relevant phenomena in spoken, written, and signed language.

4. ^Clark (1996, pp. 156-161) bases his own discussion of signs on Peirce. See Verhagen (2021a, pp. 141-150) for a fuller discussion, including an extension, of Keller's theory, and a comparison with Peirce's classification of sign types.

5. ^As similarity per se—the usual defining criterion in representational conceptions of signs—is not a necessary condition (a painting of a castle looks more like any other painting than like a castle), Keller (1998, pp. 108/9) proposes capacity for “association” as the basis for iconicity. However, this is a rather vague concept, and the term may also apply to symptoms and symbols (as Keller acknowledges). The notion of “structure mapping” is more suitable than “similarity” and more specific than “association” (there is recognizable structure in the painting that can be mapped onto the structure of a castle). Like Keller's “association”, “structure mapping” may involve a considerable amount of indirectness (cf. the logical steps and background knowledge involved in getting from the combination of the two pictorial elements “cross” (indicating a barrier or obstruction) and “pig” to the interpretation “this meal is kosher/halal”).

6. ^Symbols being conventional, signs cannot start their life as symbols. Symbols always arise out of symptoms or icons on the basis of (repeated) use (Keller, 1998, pp. 143–167), through processes of conventionalization as analyzed in Lewis (1969). It is in this process that the relation between a signifier and what it signifies may become more or less arbitrary (the only requirement for conventions is that they are mutually shared), i.e., lose their causal or iconic connection, but this is no necessity, as Keller notes. Verhagen (2021a) elaborates these issues and their implications for linguistic theory in general.

7. ^https://www.christianpost.com/news/are-you-aware-of-the-avalanche-of-gay-programming-assaulting-your-home-132277/

8. ^Quotation marks are themselves conventional signs indicating, in written language, that the material in between is being depicted. Indeed, it would not be inappropriate to label them “depiction marks”, as they are in fact also used for non-linguistic depictions. For example, Clark (2016, p. 325) represents an utterance that includes a bit of singing in the following way in print: But then he writes “dee-duh dum.”

9. ^Clip retraceable at a number of websites, including https://www.etonline.com/news/156299_ellen_degeneres_fires_back_at_christian_post_for_claiming_she_has_a_gay_agenda.

10. ^The expressive facial expression accompanying (only) the production of “married” is, in my interpretation, not a part of the depiction of Tomczak's opinion, but an independent gesture, depicting bewilderment (of DeGeneres).

11. ^Vandelanotte (2022) provides a broad overview of more types of “speech and thought representation” (see also footnote 21).

12. ^Note that it is not necessary to know that president Clinton has actually used this excuse in order to recognize the simulation (and to understand the utterance). Such differences are always a matter of interpretation; the simulation in itself is never decisive.

13. ^In turn, this can be abused by senders: make an offensive remark, and then accuse someone taking offence of not recognizing the irony (cf. Tobin and Israel, 2012 on the inherent complexity of irony interpretation). This actually points toward a fundamental ambiguity which will be addressed in Section 4.1.

14. ^Clark (2016) distinguishes three scenes, base, proximal, and distal. For my purposes in this paper, only two scenes are needed, and I conflate “base” and “proximal” into “observable”.

15. ^Imagination is both necessary and sufficient for this process. On the one hand, we can only represent the actions of historical figures to ourselves through imagination; on the other hand, a depicted act does not even have to be a possible act in the real world (e.g., a lion speaking English). The difference between fiction and history is not in the observable scene, but entirely in the interpretation of the distal scene.

16. ^At least terminologically, this resembles the label “dramaturgical theory” for Wierzbicka's (1974) analysis of quotation, that Clark and Gerrig (1990, pp. 801/2) explicitly dissociate themselves from. Although they feel much affinity to it, they ascribe this theory some limitations that their own theory does not suffer from. I leave aside to what extent this criticism makes sense, so also if the theory of 2016 still differs from dramaturgical theory.

17. ^Cf. the characterization of irony in Tobin and Israel (2012, pp. 27/28) as “allowing for apparently endless layering in certain contexts” and “fundamentally a viewpoint effect in which a conceptualization is simultaneously accessed from multiple perspectives”.

18. ^Recursive embedding is certainly not the only kind of interesting complex relationship between perspectives; cf. Van Duijn and Verhagen (2018).

19. ^The default assumption in cooperative communication is that all relevant knowledge is mutually shared, common ground, as if transparent to everyone involved (Verhagen, 2015). The account given here differs slightly—perhaps only in explicitness—from the one in Clark (2016, p. 339). His starting point is “To interpret what people are doing generally requires taking account of their viewpoints”, to which he then adds “Depictions require additional viewpoints”. The first of these statements at least suggests that speakers distinguish their viewpoints from their addressees', embedding the latter in their own, which would lead to potentially infinite recursion as the addressee must be assumed to do the same. However, Clark's (1996) account of joint projects, and especially of human cooperative communication as a joint project, implies joint attention, i.e., participants taking an intersubjectively shared perspective on some object. When coordination becomes problematic, the need may arise to “break up” the shared perspective into individual ones, so this is certainly possible, but not “generally required”, at least not for interlocutors (and it is psychologically and evolutionarily implausible; cf. Verhagen, 2021b, p. 49/50). It would seem more natural for third persons, i.e., non-participants in a conversation, but that is precisely the situation in which two “planes” of cognitive coordination have to be distinguished (Van Duijn and Verhagen, 2018), of the type given in Figure 5.

20. ^If only because the parsing of composite utterances (think of (4) and (5) again) could not be completed if only linguistic information were to be used, let alone that there would be an interpretation to be combined with information from other sources.

21. ^This relates to what Vandelanotte (2004, 2022) in a number of publications calls Distancing Indirect Speech/Thought (DIST), with more distance between reader and character than FID-proper: As Vandelanotte notes, a pronoun indicates “higher accessibility” than a proper name. The present approach suggests that the difference can be explained in terms of this function of the linguistic items involved, given the elementary distinction between depiction and description; i.e., it can be seen as one type of interpretation of the combination of depiction and description, rather than as a part of the conventional linguistic code (cf. Van Duijn and Verhagen, 2018, pp. 408-410). The conceptual character of phenomena like FID, DIST, fictive interaction, irony and others emerges from the iconic simulation of symbolic acts and the perspectival shifts associated with it. This does not preclude the possibility that the strategy of combining a proper name with a partly depicted speech act becomes a convention in a particular language community (e.g., present day users of written English), and might then be considered a (language-specific) construction. Such a claim would require some specific empirical argumentation, while it also hinges on the exact definition of the notions “construction” and “convention” (cf. footnote 6). These considerations point to a research program on the way various combinations of depiction and description are interpreted (universally) on the one hand, and conventionalized (in specific communities) on the other (see also the Conclusion Section).

22. ^Interestingly, the Dutch original has a complementizer (Dutch does not allow dropping of complementizers with finite complements). Possibly, the translator felt that leaving out that would fit the character of the passage well—it makes it similar to FID, in English. So this might be a case of a difference between Dutch and English of the type hinted at in footnote 21.

23. ^Moreover, the theoretical content of Leech and Short's approach is fundamentally different from the present one. Theirs is an instance of the “verbatim reproduction” theory of quotation criticized in Clark and Gerrig (1990).