Abstract

Effective board performance relies heavily on the smooth exchange of information and knowledge among members. However, the sociocognitive processes surrounding these information exchanges within boards, known as board dynamics, are often treated as a black box in corporate governance research. With the goal of advancing the understanding of communication-centered board dynamics, this paper develops a theoretical model of unsaid known in the boardroom. Drawing on the communication, psycho-dynamics, and governance literature, we theorize how board members jointly make sense through what they think and say and not say and offer propositions. We discern between the implicit theories of senders and listeners, shaping decision-making. Our conceptual model suggests that heightened collective awareness among board members regarding communication incongruences can improve decision-making. Addressing these discrepancies can enhance boards’ capacity for informed decision-making and optimize outcomes.

1 Introduction

Boards, as strategic decision-making teams, have become central to the institutions of contemporary societies. However, the question of how individual board members collectively make decisions remains poorly understood (Filatotchev et al., 2020; Veltrop et al., 2020; Gofen et al., 2021; Pernelet and Brennan, 2022; Weck et al., 2022; Clarke et al., 2023; Engbers and Khapova, 2023). Scholars increasingly examine these processes from cognitive and behavioral perspectives (Van Ees et al., 2009; Westphal and Zajac, 2013; Carroll et al., 2017; Boivie et al., 2021Pernelet and Brennan, 2022; Engbers and Khapova, 2023), as the sharing of information and knowledge plays a central role in facilitating effective board performance. Interestingly, an expanding body of research indicates that sociocognitive processes within boards, commonly known as board dynamics, frequently impede the quality of information sharing and knowledge exchange, thereby adversely impacting decision-making processes (Forbes and Milliken, 1999; Westphal and Bednar, 2005; Engbers and Khapova, 2023). Unfortunately, these scholars also face challenges in comprehensively understanding how board members collectively make sense of and reach decisions.

First, existing studies predominantly rely on survey-based designs, which are ill suited for capturing nuanced, moment-to-moment interactions between board members. These designs often solicit post hoc assessments, risking the influence of biased attitudes and opinions (Frone et al., 1986; Baumeister and Vohs, 2007). Furthermore, they overlook the potential misalignment between board members’ stated beliefs and their tacit ‘theories-in-use’, resulting in oversimplified portrayals of board dynamics, defensive routines and the barriers faced by members (Argyris, 1992; Boivie et al., 2016).

Moreover, delving into real-time behaviors and cognition poses numerous design hurdles and raises fundamental questions about the nature of social entities. The ontological and epistemological implications of perceiving social phenomena as objective, subjective, or intersubjective further complicate the research process (Cunliffe, 2011). Consequently, the corporate governance literature may offer idealistic solutions that are impractical to implement.

In light of these challenges, we assert that there is a pressing need for research methodologies capable of capturing the dynamic nature of board interactions and navigating the complexities of board cognition (Minichilli et al., 2012; Boivie et al., 2016, 2021; Engbers and Khapova, 2023). Addressing these methodological and conceptual hurdles is crucial for gaining a deeper understanding of board dynamics and informing more practical and effective governance strategies.

However, to develop these research methodologies effectively, we argue that adequately exploring these boardroom dynamics requires initial theorization about these complicated sociocognitive and behavioral processes, enabling researchers to design reflexive research approaches. Therefore, this paper aims to fill this void by conducting a thorough exploration of a wide range of literature covering various aspects related to communication and cognition.

To develop this framework, we build on an approach referred to by Cornelissen et al. (2015, p. 14) as ‘communicative institutionalism.’ This approach describes communication as a joint activity within which senders and listeners mutually, moment by moment, create a shared understanding of their situation. With social cognition, we refer to an individual’s learning processes through observing others within organizations. We thus propose that communication not only reflects particular cognitive outcomes but also elicits cognitive responses and consequently leads to cognitive results (Cornelissen et al., 2015).

Although “discussions of cognition are often dissociated from discussions of communication” (Ocasio et al., 2015, p. 43), in this paper, we theorize that “actors somehow generate meaningful knowledge structures – categories, frames, repertoires, logics, theories, schemas and use words to communicate those preexisting meanings” (Ocasio et al., 2015, p. 43) and influence the assessment of others.

Thus, in this paper, our aim is to explore the nexus between communication and cognition, which includes non-verbal communication and socio, meta- and cognitive processes. Drawing from this comprehensive research, we formulate propositions and suggest a framework to elucidate the sociocognitive processes among board members. More specifically, instead of centering our attention on the content of knowledge sharing, our focus lies on elucidating the dynamics surrounding the intentional or unintentional withholding of information or when certain information is tacitly assumed and left unsaid. We theorize that unspoken elements swiftly transform into what can be termed “unsaid known,” representing the collective, unarticulated evaluation of behavioral dynamics within the board.

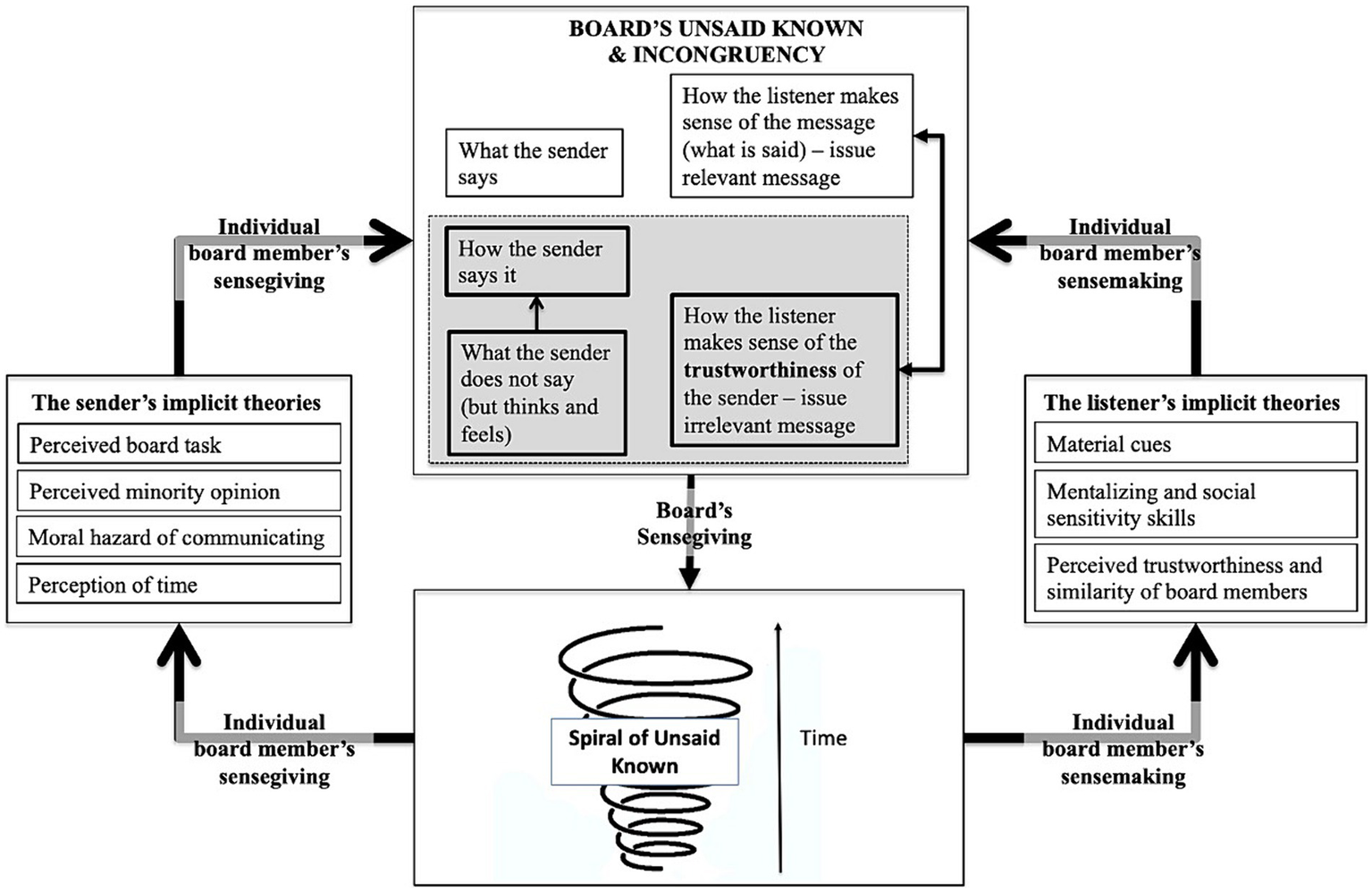

Consequently, drawing from a broad range of the sociocognitive literature, we present a conceptual model (see Figure 1). Through this framework, we aim to provide deeper insights into how communication and cognition intersect within the context of boardroom interactions and offer propositions for future research.

Figure 1

Conceptual model of the (spiral of) unsaid known in the boardroom. This conceptual framework illustrates the dynamics of communication within board meetings. The top box emphasizes the role of 'the unsaid known and incongruence’, shaped by what is said, how it is said, what is not said, and what is heard and not heard correctly. The arrow ‘board’s sensegiving’ indicates how this incongruence manifests in board communication. The bottom box introduces the concept of ‘the spiral of unsaid known,’ underscoring the enduring significance of unspoken elements when left unaddressed. The arrows ‘individual board member’s sensegiving’ and ‘individual board member’s sensemaking’ depict how implicit sender’s and listener’s theories are influenced by this spiral of unsaid known. Subsequently, the arrow stemming from implicit theories illustrates how board members decode spoken and unspoken messages and convey meaning through verbal and non-verbal cues, thereby perpetuating this dynamic process. This figure serves as a visual representation of the multifaceted communication dynamics inherent in board meetings, wherein both conveyors and recipients of information actively participate in the processes of sense-giving and sense-making.

At the core of our theoretical model lies a recognition of the pivotal role of incongruency in shaping boardroom dynamics. We explain how board members who are unaware of their taken-for-granted implicit theories that shape how they listen and respond can enact incongruent communication during board meetings and its effects. Incongruence manifests when a person’s non-verbal behavior contradicts their verbal expressions. We emphasize that when individuals display incongruence, yet listeners as ‘senders-in-waiting,’ opt not to acknowledge it, this incongruency becomes ingrained within what we term ‘the unsaid known.’ This concept represents the collective, unspoken assessment of behavioral dynamics within the board. Silenced incongruence, in turn, risks triggering a spiral of the unsaid known that proves challenging to interrupt, as it reinforces both the implicit theories of listeners and the theories of the senders. This reinforcement sustains a cycle in which incongruent behavior, shaped by implicit theories, further contributes to the unsaid known, perpetuating the cycle of silence and incongruence within the boardroom.

Acknowledging the dual roles individuals play as both senders and listeners simultaneously, the figure distinctly illustrates the differentiation between the implicit theories held by a sender and those held by a listener during specific moments in a board meeting. Consequently, both senders and listeners continuously transition between these roles in response to the evolving dynamics enacted by the unsaid known of the meeting. Whether assuming the role of a listener or sender, individuals’ actions are influenced by a combination of distinct implicit theories outlined in this paper, which shape their perceptions and subsequent responses.

We conclude the paper with a discussion of how the proposed model can be used to advance the understanding of board dynamics and decision-making in boards.

2 Board’s unsaid known and incongruency

2.1 Routine and preconscious ways of assessing and responding

Since individuals are simultaneously engaging in the sending and receiving of messages (Barnlund, 2017), they can influence this communication process positively or negatively depending on how they respond to each other and on what they try to achieve individually and as a group. Their communication is seen as a joint activity. Each member is both a sender and a listener. “The listener is an active agent, who is ‘a speaker-in-waiting’” (Cornelissen et al., 2014, p. 13) and becomes a speaker when responding. Hence, the cognition and acts of the speaker are not privileged over the intentions and cognitions of the listener; instead, both are viewed as equally important.

From psychoanalytic and psychological perspectives, individuals continuously make sense of situations using their sociocognitive and metacognitive skills, including ‘mindreading’ abilities, which allow them to predict behaviors based on perceived authenticity and congruency (Frank et al., 1993Nichols and Stich, 2004). To illustrate, individuals often rely on subconscious processes, such as ‘mindreading’, to anticipate the reactions of others based on non-verbal cues and past experiences.

Furthermore, individuals’ responses are often shaped by subconscious processes rather than conscious intentions, influenced by automatic information processing skills (Craik and Lockhart, 1972; Schneider and Shiffrin, 1977; Petty and Cacioppo, 1986; Bargh and Chartrand, 1999; Kahneman, 2012). Lyons-Ruth (1999) suggested that information does not necessarily require verbalization to be understood to some extent. Birdwhistell (2014) also noted that subconscious communication, occurring non-verbally, is significant. Similarly, Bollas (2017) posits that we possess intuitive knowledge beyond our conscious awareness, labeling this as our “unthought known.” Psychologist Chris Argyris underscores this concept by asserting that “everyone is aware of these underlying dynamics; they are tacitly understood” (Argyris, 1990, p. 3).

Given that subconscious processes heavily influence communication, individuals’ responses may be guided by intuitive knowledge and implicit understanding rather than explicit reasoning.

These studies suggest that in the context of boardrooms, where members often have diverse backgrounds, hold part-time roles, and meet episodically to discuss critical topics, establishing trust and effective communication poses significant challenges (Forbes and Milliken, 1999; Boivie et al., 2016). Moreover, as boards consist of many board members, there is an imbalance between active senders and listeners, which further complicates the communication dynamics within boards.

While boards benefit from cohesion and shared understanding, decision-making also requires cognitive conflict to foster diverse perspectives and informed choices (Forbes and Milliken, 1999; Engbers and Khapova, 2023). Nonetheless, this requirement, the periodic nature of board meetings, the involvement of numerous individuals, and the complexity of issues often lead to discussions being constrained by time and pressure (Forbes and Milliken, 1999; Boivie et al., 2016).

We suggest that due to time constraints and other barriers, board members primarily operate at a level of awareness that is taken for granted. Moreover, within the structured framework of board meetings, individuals may resort to habitual responses instead of deep reflection and conscious behavior.

This subconscious communication, occurring non-verbally, forms the basis of what we term “unsaid known,” the collective yet unspoken assessment of behavioral board dynamics. Unlike tacit knowledge, which primarily concerns practical skills and understanding (Johnson et al., 2002; Tsoukas, 2005), we suggest that “unsaid known” encompasses a broader range of knowledge, including emotional and relational information that may be difficult or even dangerous to articulate within the boardroom context. While tacit knowledge relates to skills that are challenging to verbalize, “unsaid known” refers to knowledge that individuals consciously or unconsciously suppress or avoid expressing due to perceived risks or consequences, such as fear of conflict or reprisal. We propose that while uncovering tacit knowledge and converting it into explicit knowledge, as suggested by Tsoukas (2005), can be challenging, revealing the “unsaid known” presents even greater complexity. This process may trigger defensive routines, as outlined by Argyris (1992). Thus, although related to tacit knowledge, the term “unsaid known,” this term encompasses a broader spectrum of understanding that is not solely dependent on practical expertise but also involves intuitive insights and emotional awareness. This construct highlights the performative nature of communication within the boardroom, where unspoken cues and implicit understandings shape interactions and decisions.

In sum, understanding the influence of subconscious processes on board communication is crucial for comprehending the dynamics of board interactions and decision-making processes.

Proposition 1: Board communication predominantly operates at a taken-for-granted, preconscious level, where the “unsaid known” plays a significant role in shaping interactions and decisions.

2.2 Costly communication and organizational suicide

With respect to the time and effort needed to communicate messages, Petty and Cacioppo (1986) differentiate between the more resource-intensive “central route” of persuasion, which involves careful evaluation of issue-relevant arguments, and the less demanding “peripheral route,” which emphasizes what they call ‘issue-irrelevant cues’ related to the issue. According to Petty and Cacioppo (1986) listeners use the issue-irrelevant cue route to assess the trustworthiness (expertise, attractiveness, or credibility) of the sender and determine the effort they want to put into understanding the sender. Thus, issue-irrelevant cues determine how issue-relevant cues are received, so we can assume that they are more issue-relevant, as the term would imply.

This suggests that within the communication process, individuals often rely on peripheral cues to gauge trustworthiness and determine their level of engagement with the message, which can significantly influence communication dynamics.

Moreover, Petty and Cacioppo (1986) presume that sharing issue-irrelevant information is less costly because it happens without having to express words and put effort into sharing this information. Sharing issue-relevant information, on the other hand, is costly since it requires more effort, preparation, and consideration to translate arguments and reasoning processes into words. Nevertheless, these authors prefer this route over sharing issue-irrelevant information because issue-relevant messages, which concern the dynamics often assessed between people who communicate, can be substantiated, whereas issue-irrelevant cues cannot (Dewatripont and Tirole, 2005).

For example, while sharing issue-irrelevant information might seem less demanding initially, the absence of substantive content may hinder meaningful communication and understanding among board members.

Moreover, when issue-irrelevant information that concerns the trustworthiness of the senders is not expressed due to the cost of communication, observations of incongruent behavior, we posit, are also rarely discussed during board meetings. According to Argyris (1992, 2010), underground dynamics are rarely discussed, as surfacing underground dynamics is organizational suicide; therefore, these underground dynamics are undiscussable, and undiscussability is also made undiscussable.

Indeed, the reluctance to address underlying tensions or incongruences may perpetuate a culture of avoidance within the organization, inhibiting open dialog and problem solving.

More specifically, according to Lyons-Ruth (1999, p. 578), “at the level of unconscious enactive procedures, the medium is the message; that is, the organization of meaning is implicit in the organization of the enacted relational dialog.” Dewatripont and Tirole (2005) agree, as they assert that in practice, information is often neither soft nor hard. It is in between.

Given that information processing involves both conscious and subconscious elements, it is essential to consider how implicit cues shape communication dynamics within organizational settings.

Moreover, according to Mehrabian et al. (1981), when these observations are not mentioned and the listener correctly or incorrectly perceives words to disagree with the tone of voice and other non-verbal behaviors, he or she tends to trust the tonality and non-verbal behavior and will often preconsciously respond non-verbally to this message. Listeners, as senders-in-waiting, often respond incongruently to incongruent behavior when they withhold their observations regarding the perceived incongruity of others and act as if they do not. They are also senders who listen since they communicate their thoughts and feelings non-verbally even when they try not to. For clarity purposes, we define senders or speakers as individuals who intend to communicate a message (someone who is nodding often does so with the intent to say he or she has heard the message or agrees with the message). We assume that senders do not intentionally want to send an incongruent message, so incongruity usually unintentionally induces a spiral of inauthentic action–reaction patterns in the group as a whole. Incongruity can even inspire “political maneuvers that undo whatever “consensus” teams may reach at the decision–making table” (Edmondson and Smith, 2006, p. 8).

Especially in the boardroom, where non-executives are judiciously responsible for monitoring the CEO (Forbes and Milliken, 1999) and where power dynamics create ambiguous hierarchical relations (Veltrop et al., 2017), we propose that perceived incongruity can trigger a “spiral of unsaid known.” This phenomenon occurs when political maneuvers prompt recognition but not acknowledgment within the group. This concept is related to, but distinct from, the spiral of silence of Noelle-Neumann (1993). The spiral of silence refers to the phenomenon where individuals within a group tend to remain silent or withhold their opinions if they perceive that their views are in the minority or socially unacceptable, fearing isolation or social sanctions. This leads to a reinforcement of the dominant opinion and a suppression of minority perspectives.

The spiral of unsaid known, on the other hand, pertains to situations where there is a collective awareness or recognition of certain issues, behaviors, or information within a group, but these are left unacknowledged or unspoken. Unlike the spiral of silence, where individuals refrain from expressing their opinions, the spiral of unsaid involves a tacit agreement or understanding among group members to not openly address certain matters, often due to perceived political implications, power dynamics, or relational considerations. It involves a shared avoidance of discussing uncomfortable or sensitive topics, leading to a buildup of unspoken tensions or conflicts within the group.

In sum, the reluctance to communicate costly information, coupled with the fear of organizational repercussions, underscores the importance of understanding the dynamics of underground communication within organizational settings. When left unaddressed, these issues can spiral into a “spiral of unsaid known,” making them increasingly difficult to address openly.

Proposition 2: In the context of the boardroom environment, where power dynamics and relational considerations often play a significant role, it is imperative to recognize and address the phenomenon of the “spiral of unsaid known.”

2.3 Incongruent communication and a spiral of unsaid known

People do not always say what they think or “mean what they say, in the sense that discursive output does not flow directly from cognition” (Cornelissen et al., 2014, p. 12). Incongruent communication arises when senders convey messages that diverge from their intended meaning, either deliberately or unintentionally. This incongruity can manifest through verbal and non-verbal cues, leading to internal conflicts and mixed messages (Chu et al., 2005; Eberly et al., 2013; Hall and Knapp, 2013). Additionally, competing commitments or desires may further exacerbate incongruent communication, complicating the sender’s ability to convey coherent and authentic messages (Kegan and Lahey, 2011).

This suggests that within organizational communication, incongruent messages may stem from a variety of factors, including both deliberate and unintentional actions, as well as internal conflicts and competing commitments.

When incongruity remains unaddressed, it becomes challenging to evaluate the accuracy of the implicit motives or theories (Detert and Edmondson, 2011) guiding individuals’ perceptions and response mechanisms. According to March and Simon (1993) and Kahneman (2012), human decision-making is often constrained by bounded rationality, leading to the emergence of biases and errors in judgment.

Given that human decision-making is influenced by bounded rationality, biases and errors in judgment can contribute to incongruent communication within organizational settings.

Ross et al. (1977) and Argyris (1992) further assert that individuals tend to perceive themselves as rational, despite being largely unaware of their inherent biases and cognitive limitations. Consequently, when unexpected events occur, individuals may mistakenly attribute false intentions and motives to others, perpetuating a cycle of miscommunication and misunderstanding (Argyris, 1992; Ross, 2018).

Moreover, individuals may unwittingly engage in biased behaviors while operating within routine patterns, resulting in what Argyris terms ‘skilled incompetence.’ These errors, although unintended, become ingrained in individuals’ behavioral repertoire, often due to their unconscious adherence to implicit theories that rationalize and justify these discrepancies (Argyris, 1992; Diamond, 2008; Ross, 2018). The concept of ‘skilled incompetence’ highlights how biases can persist within organizational communication because individuals are unaware of how they themselves contribute to this incongruence, leading to ongoing challenges in achieving clarity and coherence in messaging.

In sum, incongruent communication poses significant challenges to effective organizational communication, as it undermines coherence and trust within interpersonal interactions. Board members, in particular, may resort to softening their messages and masking their true opinions, adopting an emotionally neutral stance to navigate group dynamics (Jackall, 1988) without being aware how they contribute to these dynamics. This penchant for inconsistency, while seemingly advantageous in executive settings, perpetuates a culture of miscommunication and undermines organizational transparency.

Proposition 3: Biases that enact incongruent communication patterns on boards present significant challenges for effective communication and interpersonal understanding.

3 Unraveling sensemaking from the sensegiving process

As individuals engage in the complex task of sharing, withholding, or even manipulating information to attain specific goals and navigate social dynamics (Ashcraft et al., 2009), it becomes crucial to differentiate between the sensemaking and sensegiving processes, even as individuals take on dual roles as senders and listeners. Drawing on an extensive array of literature, we seek to delve into the unique implicit theories guiding both senders and listeners and develop propositions that suggest how board members both decide to respond depending on how they assess their situation. We first explore the sender’s perspective and then the listeners’ perspective.

3.1 Sender’s implicit theories: sensegiving

People communicate not only to convey information but also to negotiate and maintain relationships, reflecting the intricate nature of interpersonal dynamics within organizational contexts (Atkinson, 2002). Communication transcends the mere transmission and decoding of messages; it encompasses an ongoing, dynamic, and interactive process of symbol manipulation that is central to organizational existence and phenomena (Ashcraft et al., 2009). As Jackall (1988) astutely observes, managers adeptly navigate complex symbolic forms to shape perceptions and influence outcomes, often employing nuanced messaging to convey underlying intentions.

For example, phrases such as “He is exceptionally well qualified” may be interpreted as “He has committed no major blunders to date,” while “He is slightly below average” may signal “he is stupid,” while board members employ strategic messaging to convey desired meanings while simultaneously managing perceptions and relationships. Jackall’s (1988) examples highlight the subtle nuances in communication, where seemingly innocuous statements carry layered meanings that are decipherable to astute recipients.

3.1.1 The senders perceived board task

Board members aim to contribute to both the success of the board’s performance and their own personal success, as they define it. Central to this objective is the effective execution of the board’s control and service tasks, which encompass routine issues and require seamless sharing of information and knowledge among board members.

The decision-making performance of boards directly influences firm performance, indeed emphasizing the critical role of cohesive board dynamics and managing the tension between cohesiveness and cognitive conflict (Forbes and Milliken, 1999; Engbers and Khapova, 2023).

Additionally, the roles held by different board members shape the task and dynamics within the board. For instance, the chair plays a crucial role in guiding discussions and setting the agenda, while the CEO offers insights from an operational perspective. Other board members contribute their expertise and viewpoints, enriching the decision-making process with diverse insights.

These varying roles and responsibilities influence the dynamics of communication within the board and may impact how individual members perceive their obligations and objectives (Westphal and Bednar, 2005; Veltrop et al., 2017).

Boards may also experience paradoxical tension as they navigate the dual responsibilities of monitoring and collaboration (Sundaramurthy and Lewis, 2003; Carroll et al., 2017; Boivie et al., 2021). Moreover, board members may hold divergent views on the board’s task (Pieterse et al., 2011). When information is shared for effective decision-making but board members assume that voicing their opinion may upset someone and put their personal goals at risk, they have competing commitments (Kegan and Lahey, 2011) and may choose not to express their opinion.

The literature suggests that individual board members may harbor differing implicit theories regarding how to achieve the intended outcome, particularly when faced with competing commitments that may jeopardize personal goals.

Proposition 4: The assessment of individual board members of the board’s task significantly influences the implicit sender theories held by board members, shaping their communication and decision-making processes within the boardroom.

3.1.2 The senders (perceived) minority opinion

In board settings, there is a tendency for board members to align with majority views, even if they hold dissenting opinions individually. This phenomenon, described as “herding” by Malenko (2014), occurs when board members defer to the perceived consensus of the group, placing less emphasis on their own private information and opinions. This suggests that the influence of group dynamics on individual decision-making processes is significant, particularly regarding the adoption of majority opinions over dissenting viewpoints.

As noted by Sunstein and Hastie (2014), the strength and impact of these informational signals are influenced by factors such as the number, nature, and authority of those conveying them. To illustrate, we propose that when influential board members express a particular viewpoint, they may sway others to conform, regardless of their personal beliefs or reservations. Given that individuals often look to authority figures for guidance and validation, the influence of key opinion leaders within the boardroom can significantly shape decision-making dynamics.

Conformity to the majority is facilitated by several cognitive biases and group dynamics, including ‘groupthink’ and the ‘false-consensus effect.’ Groupthink, as described by Janis (1972), occurs when cohesive group dynamics hinder critical reflection and discussion of differing opinions, leading to conformity. Similarly, the false-consensus effect (Ross et al., 1977) manifests as the tendency to assume that others share one’s beliefs, further reinforcing the inclination to align with the majority.

The reluctance to express minority opinions may result in situations where dissenting voices remain unheard of, leading to decisions that may not accurately reflect the preferences of all board members. This underscores the challenges faced by minority groups and individuals in asserting their viewpoints within boardroom discussions. This phenomenon, illustrated by the Abilene paradox (Harvey, 1974), serves as a poignant example of how the fear of dissent can lead to suboptimal decision-making outcomes.

In sum, the discussion on board dynamics reveals a tendency for board members to conform to majority views, even when holding dissenting opinions individually. This phenomenon, known as “herding,” underscores the influence of group dynamics on individual decision-making processes. Additionally, the strength of informational signals is influenced by factors such as the authority of those conveying them, further highlighting the impact of influential opinion leaders within the boardroom.

Moreover, cognitive biases and group dynamics such as groupthink and the false-consensus effect facilitate conformity to the majority, potentially leading to decisions that do not accurately represent the preferences of all board members. This reluctance to express minority opinions can result in situations where dissenting voices remain unheard, ultimately impacting decision-making outcomes within the group.

Proposition 5: The perception of being in the minority within the board influences the implicit sender theories held by board members, impacting their communication and decision-making processes within the group.

3.1.3 The senders’ moral hazard of communicating

People engage in a continuous, subconscious assessment of the potential risks involved in communicating their thoughts and perspectives (Detert and Edmondson, 2011; Morrison, 2014). This assessment is not solely based on the content of the message but also considers the social and relational consequences that may arise from expressing divergent views (Sunstein and Hastie, 2014, p. 566). Indeed, the perceived risks associated with expressing dissenting views often outweigh the desire for open dialog and constructive debate.

In addition, power differentials within teams (Edmondson and Besieux, 2021) and boards (Malenko, 2014) intensify the perceived risk faced by members who wish to express dissenting opinions. Leaders, such as the chairperson, have a significant influence on team dynamics, impacting individuals’ willingness to speak up (Veltrop et al., 2017). This phenomenon, also referred to as CEO disease (Goleman et al., 2013), creates an environment where withholding issue-relevant information becomes commonplace to avoid potential repercussions.

Moreover, a lack of comprehensive decision-making processes for strategic issues can exacerbate cognitive conflicts among board members. Verifiable data may be sidelined in favor of opposing opinions expressed as facts, leading to rationalizations and negative attributions about others (Engbers and Khapova, 2023). These conflicts, when left unaddressed, contribute to incongruent behaviors and speculation among board members, further hindering effective communication (Ross et al., 1977; Pronin et al., 2004; Mooney et al., 2007).

In sum, the discussion on the sender’s moral hazard of communicating highlights the continuous assessment of risks associated with expressing dissenting views within board settings. This assessment considers not only the content of the message but also the potential social and relational consequences (Detert and Edmondson, 2011; Morrison, 2014). Power differentials within teams and boards intensify these perceived risks, with leaders exerting significant influence on team dynamics (Malenko, 2014; Edmondson and Besieux, 2021). This dynamic, also known as CEO-disease (Goleman et al., 2009), creates an environment where withholding issue-relevant information becomes common to avoid potential repercussions.

Furthermore, a lack of comprehensive decision-making processes for strategic issues can exacerbate cognitive conflicts among board members, leading to rationalizations and negative attributions about others (Engbers and Khapova, 2023). These conflicts contribute to incongruent behaviors and speculation among board members, further hindering effective communication (Ross et al., 1977; Pronin et al., 2004; Mooney et al., 2007).

Proposition: Within board settings, apprehension regarding potential repercussions for expressing dissenting opinions fosters hesitancy among board members to voice minority perspectives, which in turn inhibits the emergence of cognitive conflict.

3.1.4 The senders perception of time

Most boards operate as large, episodic groups with constrained time frames for discussions during meetings (Forbes and Milliken, 1999). This suggests that board members may often feel pressured to articulate their views within limited time constraints, hindering the comprehensive exchange of knowledge and perspectives (Boivie et al., 2016). To illustrate, the necessity for members to substantiate their positions with objective evidence and persuasive arguments, particularly in the presence of diverse backgrounds and norms, further exacerbates the challenge of effective communication (Malenko, 2014). Indeed, the time allotted for discussions often falls short of accommodating the complexities and strategic nature of the issues at hand, leading to frustrations among members unable to fully express their thoughts.

In such instances, the urgency to convey information competes with the complexity and strategic nature of the issues at hand, exacerbating the challenge of effective communication. This frustration, when left unaddressed, contributes to a higher level of unspoken concern within the board, perpetuating an environment of inauthentic interactions and responses. Moreover, the prioritization of issue-relevant, verifiable information over issue-irrelevant data (Petty and Cacioppo, 1986) further restricts the exchange of perspectives and inhibits the potential for constructive dialog.

Proposition 7: The limited time allocated for discussions in board meetings constrains the exchange of information and perspectives, leading to a greater prevalence of unspoken sentiments and inhibiting the board’s ability to foster authentic communication and cohesive decision-making processes.

3.2 Listener’s implicit theories: sensemaking

Listeners, also referred to as “senders-in-waiting,” play a pivotal role in communication processes. This suggests that the listener extends beyond mere reception and decoding of verbal and non-verbal cues; it encompasses the critical task of attributing meaning to received messages and making sense of the broader context in which these messages are embedded (Ross and Ward, 1996; Pronin et al., 2004; Weick et al., 2005; Kahneman, 2012). Moreover, within the dynamic environment of board meetings, we suggest that listeners exhibit a tendency to selectively focus on distinct facets of the discourse, whether specific words, gestures, or other contextual cues, resulting in diverse interpretations of the same information. Moreover, the meaning ascribed to these selected elements can vary significantly among listeners, shaping their overall understanding of the situation at hand.

It is our contention that the perspective adopted by listeners profoundly impacts their interpretation of messages and their subsequent sense-making process. We assume that listeners’ implicit theories are tied to their individual objectives, roles, and desired outcomes, which serve as guiding forces in their cognitive processing and decision-making endeavors. In addition to the roles and perceptions of tasks, we delve into three other implicit theories that shape listeners’ cognitive frameworks. In the following paragraphs, we delve into how board members, through their implicit listener’s theories, as senders-in-waiting, make sense of their situation.

3.2.1 Material cues

Material artifacts are indispensable in constructing shared knowledge structures and fostering reflection (Cornelissen et al., 2014; Stigliani and Ravasi, 2018). They support both retrospective reflection and prospective sensemaking, aiding individuals and groups in envisioning and planning for the future (Rouleau and Balogun, 2007; Stigliani and Ravasi, 2012). These artifacts, including physical objects such as drawings, prototypes, and presentations, play a pivotal role in shaping group dynamics and enabling collaborative interpretation. Notably, gestures, as suggested by Cornelissen et al. (2014), are also considered material cues, further underscoring their significance in communication dynamics.

Within the challenging communication environment of board settings, rich with time constraints and judicial responsibilities we assume material cues are abundant (Cornelissen et al., 2014). Governing rules and procedures, documented in organizational bylaws and charters, delineate formal roles, responsibilities, and meeting structures, influencing power dynamics and communication patterns (Chu et al., 2005). Moreover, tools such as reports and presentations are employed to manage information asymmetry among board members.

Recognizing the challenging communication environment within board settings, characterized by time constraints and judicial responsibilities we assert that this setting is rich in material cues (Vaara and Monin, 2010). Among the most influential are the governing rules and procedures that delineate formal roles and responsibilities, which are often documented in organizational bylaws and charters. These rules not only outline tasks but also dictate fundamental aspects such as board composition, meeting frequency, deliberation time, and authority distribution. Furthermore, they influence seating arrangements during meetings, subtly affecting power dynamics and communication patterns (Chu et al., 2005).

Given the limited time and information asymmetry among board members, we assert that listeners’ implicit theories are deeply influenced by these material cues, governing rules, and time pressure. These cues shape their perception of formal responsibilities, decision-making processes, and interactions with colleagues within the boardroom.

Proposition 8: The governing rules, procedures and agenda that enact the formal roles and responsibilities within board settings significantly shape the implicit theories held by listeners, influencing their perception of formal responsibility, decision-making processes, and interactions with colleagues.

3.2.2 Mentalizing and social sensitivity skills

People cannot not communicate (Watzlawick and Beavin, 1967). Effective communication, encompassing both verbal and non-verbal aspects, is crucial in interpersonal interactions (Birdwhistell, 2014; Hargie, 2021). Individuals swiftly make sense of situations, drawing upon available information. For example, sensemaking, as Weick (1995) suggests, involves the interplay between frames, cues, and the relational connections formed between them. Words alone do not dictate meaning but rather trigger larger cognitive frameworks that guide prompt interpretation and action (Cornelissen et al., 2014). Individuals invest significant cognitive effort in forming hypotheses about incoming information and aligning it with preexisting schemas Yus (1999). Interpretation thus hinges on implicit theories guiding conversational responses.

Social sensitivity plays a pivotal role in these sensemaking processes (Hall and Knapp, 2013). Emotional contagion studies underscore how followers mirror leaders’ emotions (Hatfield et al., 1994). Social sensitivity influences mentalizing, gauging the authenticity of others’ expressions (Chu et al., 2005). Individuals often accurately predict others’ actions based on inferred thoughts and emotions (Hall and Knapp, 2013). Emotional contagion studies underscore how followers mirror leaders’ emotions through facial mimicry (Hatfield et al., 1994). Even in cases where individuals mask their emotions, such as with a poker face, recipients may glean insights into their intentions (Chu et al., 2005). Social sensitivity also influences the accuracy of mentalizing, wherein individuals gauge the authenticity of others’ expressions, such as remorse (Chu et al., 2005).

These studies suggest that group dynamics are significantly impacted by social sensitivity. Woolley et al. (2010) found, for example, that collective intelligence, which contributes to a group’s performance, is strongly correlated with the average social sensitivity of its members. Additionally, teams proficient in recognizing member emotions tend to outperform those lacking such proficiency, particularly in managing cognitive conflicts and social biases (Elfenbein et al., 2007).

In the dynamic environment of the boardroom, where communication challenges are amplified by time constraints and an ambiguous hierarchical structure, we posit that the significance of mentalizing and social sensitivity skills becomes even more pronounced. Board members must navigate complex interactions, often influenced by power dynamics and subtle cues, to effectively collaborate and make informed decisions.

Within this context, the ability to accurately interpret others’ thoughts, emotions, and intentions, as highlighted by theories of mentalizing and social sensitivity (Hatfield et al., 1994; Hall and Knapp, 2013), is paramount. Board members must be attuned to both verbal and non-verbal cues, including facial expressions and gestures, to gauge the authenticity of their colleagues’ communications (Chu et al., 2005). This heightened social sensitivity enables them to foster trust, resolve conflicts, and cultivate a collaborative atmosphere conducive to effective decision-making.

Moreover, these studies suggest that the collective social sensitivity of board members significantly influences group dynamics and performance (Woolley et al., 2010). Boards characterized by high social sensitivity are better equipped to manage cognitive conflicts and navigate power dynamics, ultimately enhancing communication dynamics and decision outcomes.

Proposition 9: Board performance is significantly impacted by the collective social sensitivity of its members, particularly in managing cognitive conflicts and fostering effective communication dynamics.

3.2.3 The perceived trustworthiness and similarity of board members

Studies by Byrne (1961) and Eberly et al. (2013) suggest that the level of attraction, similarity, and shared background among individuals significantly influence their ability to communicate, coordinate, and understand each other. Conversely, when these factors differ among individuals, communication and coordination are hindered, as noted implicitly in these studies. Hinds and Mortensen (2005) further argue that exposure to a common context enhances understanding and mitigates interpersonal conflict within teams.

Petty and Cacioppo (1986) and Dewatripont and Tirole (2005), as discussed earlier, support these findings by highlighting that individuals continuously exchange issue-relevant information verbally while silently assessing the trustworthiness of the sender non-verbally. The perceived attractiveness, trustworthiness, or expertise of the sender significantly influences listeners’ receptiveness and processing of the information, particularly when they have a stake in the issue under scrutiny. Conversely, low levels of trustworthiness, expertise, attractiveness, or sender incongruity diminish listeners’ commitment to understanding and processing information, leading to misinterpretation of issue-irrelevant cues (Dewatripont and Tirole, 2005).

Given the specific context of boardrooms, characterized by diverse backgrounds, part-time roles, and episodic meetings, we assert that establishing and maintaining trust poses significant challenges. The imbalance between active senders and listeners, given the relatively large size of boards, further complicates communication dynamics. Moreover, while boards benefit from cohesion and shared understanding, effective decision-making necessitates cognitive conflict to foster diverse perspectives and informed choices (Forbes and Milliken, 1999). Engbers and Khapova (2023) highlight the struggle that boards face in managing the tension between cohesion and cognitive conflict, as the latter may lead to affective conflict and erode trust among members.

In sum, the complexity of boardroom dynamics is compounded when members lack similarity and attraction. In such cases, the effort invested by individual listeners in processing information varies based on the perceived trust developed through previous experiences or shared backgrounds.

Proposition 10: The implicit theories held by listeners regarding the trustworthiness and similarity of the sender significantly influence their receptiveness to communicated messages, shaping their willingness to invest effort in understanding and processing information and ultimately impacting the effectiveness of communication within the board setting.

4 Toward a model of a spiral of unsaid known in the boardroom

In summary, the model posits that the unsaid known in the boardroom becomes profoundly consequential when listeners perceive incongruence in senders and react instinctively. This discrepancy between verbal and non-verbal cues diminishes the quality of communication, adversely affecting decision-making processes and the subsequent commitment of board members to the decisions made. Consequently, when these decisions are conveyed to stakeholders, board members engage in sensemaking and sensegiving processes, perpetuating a cycle of incongruent sociocognitive and communicative events and a level of unsaid known.

Senders and listeners within the boardroom play pivotal roles in shaping and interpreting communication dynamics. Boards tasked with deliberating decisions (Forbes and Milliken, 1999) primarily engage in communication behaviors, making it challenging to discern true agreement or cohesiveness among members. Incongruent behaviors (Chu et al., 2005; Eberly et al., 2013; Hall and Knapp, 2013), such as verbalizing agreements when dissenting internally, erode trustworthiness, hindering the effective execution of decisions.

The perception of time constraints, pressure to conform, fear of social and financial repercussions, and concern for maintaining board cohesion contribute to a spiral of the unsaid known. This reluctance to share information diminishes decision quality and commitment, despite the need for diverse perspectives to enhance critical thinking (Forbes and Milliken, 1999). However, by fostering a culture of productive information sharing, board members can mitigate a spiral of the unsaid known, thereby enhancing decision-making processes.

Furthermore, the model suggests that when distrust and political maneuvering emerge within the boardroom, the discussion of these dynamics becomes increasingly challenging (Argyris, 1992). The biases underlying these dynamics remain unresolved, as they are not voiced and refuted, leading to unwarranted blame and hampered decision-making. Minority opinions are often overlooked, and groupthink (Janis, 1972) and false consensus (Ross et al., 1977) prevail, exacerbating the detrimental effects of the unsaid known on boardroom dynamics and decision outcomes.

If board members are collectively aware of this phenomenon, we assume they would deal with it more consciously or would at least find it hard to act as if underground dynamics are not present. Why would they cover up what they know everyone knows (Sunstein and Hastie, 2014)? When listeners are willing to share information in a productive way about how they assess issue-irrelevant information, incongruity is halted. Given that there are usually more listeners than senders during board meetings, only one listener may change the conversation when he or she shares inferences about perceived incongruity.

Knowledge of interpersonal interaction could help people overcome such issues: “Many conflicts become unproductive because people do not understand the dynamic nature of interpersonal interaction – that is, how what I say affects what you think, which affects what you say and then what I think next, and so on. Not seeing our own contribution to the other’s behavior, we feel blameless when we encounter an interpersonal problem” (Edmondson and Smith, 2006, p. 22).

5 Discussion

The exploration of sociocognitive processes within the boardroom and their influence on decision-making represents a critical endeavor in understanding organizational dynamics. This paper aimed to shed light on these processes by drawing insights from the communication, psycho-dynamic, and governance literatures to develop preliminary propositions and a model of the “unsaid known” phenomenon in the boardroom.

Our model underscores the significance of implicit theories (Detert and Edmondson, 2011) and taken-for-granted communicative events in shaping decision-making among board members. By distinguishing between the cognition of senders and listeners (Cornelissen et al., 2015), we have sought to theorize their unique sensemaking processes. We propose that heightened collective awareness of incongruences in communicated information and underlying dynamics can potentially enhance decision-making processes.

These preliminary theories emphasize the need to delve more deeply into the mechanisms behind board members’ active listening and their decisions regarding the expression of thoughts and feelings. This calls for real-time explorations involving direct engagement within the boardroom setting to capture the genuine situations, thoughts, and feelings of board members rather than relying solely on interviews to probe overarching values and beliefs.

Moreover, distinguishing between the implicit theories (Detert and Edmondson, 2011) of senders and receivers is crucial, as it reveals the disparity between individuals’ personal thoughts and feelings versus their perceptions of others’ thoughts and feelings. This differentiation underscores the complex nature of mindreading and metacognition, emphasizing the necessity for nuanced methodologies in investigating these processes (Schraw and Moshman, 1995; Nichols and Stich, 2004; Dimaggio et al., 2008). This suggests that researchers should not only investigate what board members think themselves but also delve into their perceptions of what others think (second order) and even their perceptions of what others think they themselves think (third order metacognition) (Strle, 2012). A clear distinction between the thoughts and emotions of board members may pose challenges, but investigating the role of emotions and emotion recognition skills could significantly enrich our understanding of these board processes (Elfenbein et al., 2007; Kelly and Metcalfe, 2011).

Further research is also warranted to delve into implicit, preconscious (Dehaene et al., 2006) processes and biases (Argyris, 1992; Kahneman, 2012) within the boardroom, as well as how board members assess and respond to these dynamics. In particular, the unsaid known may proliferate in instances of increasingly incongruent behavior (Chu et al., 2005; Eberly et al., 2013; Hall and Knapp, 2013), distrust, and political maneuvering, posing challenges for discussion and exploration (Argyris, 1992). Given the implicit theories surrounding risk and minority opinion, further research is warranted to explore the influence of power dynamics on sensemaking processes (Weick et al., 2005).

Crucially, our model indicates that incongruencies not only affect internal board processes but also spill over into communication with stakeholders, potentially impeding effective stewardship. This observation prompts an exploration of the role of incongruency in shaping institutional logic (Cornelissen et al., 2015). Exploring incongruencies, however, may elicit defensive responses, suggesting that addressing the unsaid known within boards requires multifaceted strategies, including creating an environment where social biases are normalized, establishing group norms that encourage critical thought, and allowing time for informal interactions and discussions during meetings (Edmondson, 2004). By proactively managing the unsaid, boards can mitigate biases, enhance decision-making processes, and foster a culture of openness and trust.

Methodological advancements, exemplified by the adaptation of the left-hand column method (Senge, 1997), present an opportunity for investigating the phenomenon of the unsaid known. By incorporating speculation about others’ unspoken thoughts and feelings alongside individuals’ own reflections, this method offers a comprehensive approach to understanding the dynamics of communication and cognition within the boardroom. Nevertheless, challenges persist in addressing defensive reactions and ensuring confidentiality (Putnam, 1991). Additionally, investigating individuals’ thoughts and feelings, both about themselves and others, reveals social biases that pose analytical complexities. Discerning truth from perception and reality from interpretation becomes paramount. Therefore, delving into these biases implies a need for researchers to introspect on their own biases and their positioning within their research (Cunliffe, 2011). Maintaining consistency between approach and philosophical stance is crucial to avoid ontological drift.

Statements

Author contributions

ME: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. SK: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. EL: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We hereby acknowledge that the paper titled ‘The spiral of the unsaid known and preconscious decision-making in the boardroom’ is part of ME’ Ph.D. thesis titled ‘How the unsaid shapes decision-making in boards: A reflexive exploration of paradigms in the boardroom.’ The Ph.D. thesis was published online on the 14th of October 2020 and was developed under the supervision of SK as the supervisor and EL was the co-supervisor.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

ArgyrisC. (1990). “The dilemma of implementing controls: the case of managerial accounting” in Readings in accounting for management control. eds. EmmanuelC.OtleyD.MerchantK. (Boston: Springer), 669–680.

2

ArgyrisC. (1992). Overcoming organizational defenses. J. Qual. Particip.15:26.

3

ArgyrisC. (2010). Organizational traps: Leadership, culture, organizational design. OUP Oxford.

4

AshcraftK. L.KuhnT. R.CoorenF. (2009). 1 constitutional amendments: “materializing” organizational communication. Acad. Manag. Ann.3, 1–64. doi: 10.1080/19416520903047186

5

AtkinsonD. (2002). Toward a sociocognitive approach to second language acquisition. Mod. Lang. J.86, 525–545. doi: 10.1111/1540-4781.00159

6

BarghJ. A.ChartrandT. L. (1999). The unbearable automaticity of being. Am. Psychol.54, 462–479. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.54.7.462

7

BarnlundD. C. (2017). “A transactional model of communication” in Communication theory ed. MortensenC. D., (Routledge), 47–57.

8

BaumeisterR. F.VohsK. D. (2007). Self-regulation, ego depletion, and motivation. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass1, 115–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00001.x

9

BirdwhistellR. L. (2014). Kinesics and context: Essays on body motion communication. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

10

BoivieS.BednarM. K.AguileraR. V.AndrusJ. L. (2016). Are boards designed to fail? The implausibility of effective board monitoring. Acad. Manag. Ann.10, 319–407. doi: 10.1080/19416520.2016.1120957

11

BoivieS.WithersM. C.GraffinS. D.CorleyK. G. (2021). Corporate directors' implicit theories of the roles and duties of boards. Strateg. Manag. J.42, 1662–1695. doi: 10.1002/smj.3320

12

BollasC. (2017). The shadow of the object: psychoanalysis of the unthought known. London: Routledge.

13

ByrneD. (1961). Interpersonal attraction and attitude similarity. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol.62, 713–715. doi: 10.1037/h0044721

14

CarrollB.IngleyC.InksonK. (2017). Boardthink: exploring the discourses and mind-sets of directors. J. Manag. Organ.23, 606–620. doi: 10.1017/jmo.2017.36

15

ChuY.StrongW.MaJ.GreeneW. (2005). Silent messages in negotiations: the role of non-verbal communication in cross-cultural business negotiations. J. Organ. Cult. Commun. Confl.9, 113–129.

16

ClarkeD.ApplefordG.CocozzaA.ThabetA.BloomG. (2023). The governance behaviours: a proposed approach for the alignment of the public and private sectors for better health outcomes. BMJ Glob. Health8:e012528. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2023-012528

17

CornelissenJ. P.DurandR.FissP. C.LammersJ. C.VaaraE. (2015). Putting communication front and center in institutional theory and analysis. Acad. Manag. Rev.40, 10–27. doi: 10.5465/amr.2014.0381

18

CornelissenJ. P.MantereS.VaaraE. (2014). The contraction of meaning: the combined effect of communication, emotions, and materiality on sensemaking in the stockwell shooting. J. Manag. Stud.51, 699–736. doi: 10.1111/joms.12073

19

CraikF. I. M.LockhartR. S. (1972). Levels of processing: a framework for memory research. J. Verbal Learn. Verbal Behav.11, 671–684. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5371(72)80001-X

20

CunliffeA. L. (2011). Crafting qualitative research: morgan and smircich 30 years on. Organ. Res. Methods14, 647–673. doi: 10.1177/1094428110373658

21

DehaeneS.ChangeuxJ. P.NaccacheL.SackurJ.SergentC. (2006). Conscious, preconscious, and subliminal processing: a testable taxonomy. Trends Cogn. Sci.10, 204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.03.007

22

DetertJ. R.EdmondsonA. C. (2011). Implicit voice theories: taken-for-granted rules of self-censorship at work. Acad. Manag. J.54, 461–488. doi: 10.5465/AMJ.2011.61967925

23

DewatripontM.TiroleJ. (2005). Modes of communication. J. Political Econ113, 1217–1238. doi: 10.1086/497999

24

DiamondM. A. (2008). Telling them what they know: organizational change, defensive resistance, and the unthought known. J. Appl. Behav. Sci.44, 348–364. doi: 10.1177/0021886308317403

25

DimaggioG.LysakerP. H.CarcioneA.NicolòG.SemerariA. (2008). Know yourself and you shall know the other… to a certain extent: multiple paths of influence of self-reflection on mindreading. Conscious. Cogn.17, 778–789. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2008.02.005

26

EberlyM. B.JohnsonM. D.HernandezM.AvolioB. J. (2013). An integrative process model of leadership: examining loci, mechanisms, and event cycles. Am. Psychol.68, 427–443. doi: 10.1037/a0032244

27

EdmondsonA. C. (2004). “Psychological safety, trust, and learning in organizations: a group-level lens” in Trust and distrust in organizations: dilemmas and approaches. eds. KramerR. M.CookK. S. (New York: Russell Sage Foundation), 239–272.

28

EdmondsonA. C.BesieuxT. (2021). Reflections: voice and silence in workplace conversations. J. Change Manag.21, 269–286. doi: 10.1080/14697017.2021.1928910

29

EdmondsonA. C.SmithD. M. (2006). Too hot to handle? How to manage relationship conflict. Calif. Manag. Rev.49, 6–31. doi: 10.2307/41166369

30

ElfenbeinH. A.PolzerJ. T.AmbadyN. (2007). “Team emotion recognition accuracy and team performance” in Functionality, intentionality and morality (research on emotion in organizations). eds. HärtelC. E. J.AshkanasyN. M.ZerbeW. J. (Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited), 87–119.

31

EngbersM.KhapovaS. N. (2023). How boards manage the tension between cognitive conflict and cohesiveness: illuminating the four board conflict climates. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev.32, 63–88. doi: 10.1111/corg.12516

32

FilatotchevI.AguileraR. V.WrightM. (2020). From governance of innovation to innovations in governance. Acad. Manag. Perspect.34, 173–181. doi: 10.5465/amp.2017.0011

33

ForbesD. P.MillikenF. J. (1999). Cognition and corporate governance: understanding boards of directors as strategic decision-making groups. Acad. Manag. Rev.24, 489–505. doi: 10.2307/259138

34

FrankM. G.EkmanP.FriesenW. V. (1993). Behavioral markers and recognizability of the smile of enjoyment. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol.64, 83–93. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.1.83

35

FroneM. R.AdamsJ.RiceR. W.Instone-NoonanD. (1986). Halo error: a field study comparison of self -and subordinate evaluations of leadership process and leader effectiveness. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull.12, 454–461. doi: 10.1177/0146167286124008

36

GofenA.MoseleyA.ThomannE.WeaverR. K. (2021). Behavioural governance in the policy process: introduction to the special issue. J. Eur. Public Policy28, 633–657. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2021.1912153

37

GolemanD.BoyatzisR.MckeeA. (2009). Primal leadership. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev.37, 75–84. doi: 10.1109/EMR.2009.5235507

38

GolemanD.BoyatzisR. E.McKeeA. (2013). Primal leadership: unleashing the power of emotional intelligence. Boston: Harvard Business Press.

39

HallJ. A.KnappM. L. (2013). “Welcome to the handbook of non-verbal communication” in Non-verbal communication. eds. HallJ. A.KnappM. L. (Boston: De Gruyter Mouton), 3–8.

40

HargieO. (2021). Skilled interpersonal communication: research, theory and practice, Routledge.

41

HarveyJ. B. (1974). The Abilene paradox: the management of agreement. Organizational dynamics.

42

HatfieldE.CacioppoJ. T.RapsonR. L. (1994). Emotional Contagion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

43

HindsP. J.MortensenM. (2005). Understanding conflict in geographically distributed teams: the moderating effects of shared identity, shared context, and spontaneous communication. Organ. Sci.16, 290–307. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1050.0122

44

JackallR. (1988). Moral mazes: the world of corporate managers. Int. J. Politics Cult. Soc.1, 598–614. doi: 10.1007/BF01390690

45

JanisI. (1972). Victims of group think. Groupthink is seen as a negative for such groups. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

46

JohnsonB.LorenzE.LundvallB. Å. (2002). Why all this fuss about codified and tacit knowledge?Ind. Corp. Change11, 245–262. doi: 10.1093/icc/11.2.245

47

KahnemanD. (2012). “Mental effort,” in thinking, Fast and SlowPenguin.

48

KeganR.LaheyL.L. (2011). The real reason people won’t change. Boston: Harvard Business Review.

49

KellyK. J.MetcalfeJ. (2011). Metacognition of emotional face recognition. Emotion11, 896–906. doi: 10.1037/a0023746

50

Lyons-RuthK. (1999). The two-person unconscious: intersubjective dialogue, enactive relational representation, and the emergence of new forms of relational organization. Psychoanal. Inq.19, 576–617. doi: 10.1080/07351699909534267

51

MalenkoN. (2014). Communication and decision-making in corporate boards. Rev. Financ. Stud.27, 1486–1532. doi: 10.1093/rfs/hht075

52

MarchJ. G.SimonH. A. (1993). Organizations. New York: Wiley.

53

MehrabianA. (1981). Silent messages: implicit communication of emotions and attitudes. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, Inc.

54

MinichilliA.ZattoniA.NielsenS.HuseM. (2012). Board task performance: an exploration of micro- and macro-level determinants of board effectiveness. J. Organ. Behav.33, 193–215. doi: 10.1002/job.743

55

MooneyA. C.HolahanP. J.AmasonA. C. (2007). Don't take it personally: exploring cognitive conflict as a mediator of affective conflict. J. Manag. Stud.44, 733–758. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00674.x

56

MorrisonE. W. (2014). Employee voice and silence. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav.1, 173–197. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091328

57

NicholsS.StichS. (2004). Reading one’s own mind: self-awareness and developmental psychology. Can. J. Philos.30, 297–339. doi: 10.1080/00455091.2004.10717609

58

Noelle-NeumannE. (1993). The spiral of silence: public opinion--our social skin. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

59

OcasioW.LoewensteinJ.NigamA. (2015). How streams of communication reproduce and change institutional logics: the role of categories. Acad. Manag. Rev.40, 28–48. doi: 10.5465/amr.2013.0274

60

PerneletH. R.BrennanN. M. (2022). Challenge in the boardroom: director–manager question-and-answer interactions at board meetings. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev.31, 544–562. doi: 10.1111/corg.12492

61

PettyR. E.CacioppoJ. T. (1986). “The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion” in Advances in experimental social psychology. ed. BerkowitzL. (Cambridge: Academic Press), 123–205.

62

PieterseA. N.Van KnippenbergD.Van GinkelW. P. (2011). Diversity in goal orientation, team reflexivity, and team performance. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process.114, 153–164. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2010.11.003

63

ProninE.GilovichT.RossL. (2004). Objectivity in the eye of the beholder: divergent perceptions of bias in self versus others. Psychol. Rev.111, 781–799. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.111.3.781

64

PutnamR. (1991). “Recipes and reflective learning: “what would prevent you from saying it that way?”” in The reflective turn: Case studies in and on reflective practice. ed. SchönD. A. (New York: Teachers College Press), 145–163.

65

RossL. (2018). From the fundamental attribution error to the truly fundamental attribution error and beyond: my research journey. Perspect. Psychol. Sci.13, 750–769. doi: 10.1177/1745691618769855

66

RossL.GreeneD.HouseP. (1977). The “false consensus effect”: an egocentric bias in social perception and attribution processes. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol.13, 279–301. doi: 10.1016/0022-1031(77)90049-X

67

RossL.WardA. (1996). “Naive realism in everyday life: implications for social conflict and misunderstanding” in Values and knowledge. eds. ReedE. S.TurielE.BrownT. (Hillsdale, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.), 103–135.

68

RouleauL.BalogunJ. (2007). Exploring middle managers' strategic sensemaking role in practice. Adv. Inst. Manag. Res. Pap. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.1309585

69

SchneiderW.ShiffrinR. M. (1977). Controlled and automatic human information processing: I. Detection, search, and attention. Psychol. Rev.84, 1–66. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.1.1

70

SchrawG.MoshmanD. (1995). Metacognitive theories. Educ. Psychol. Rev.7, 351–371. doi: 10.1007/BF02212307

71

SengeP. M. (1997). The fifth discipline. Meas. Bus. Excell.1, 46–51. doi: 10.1108/eb025496

72

StiglianiI.RavasiD. (2012). Organizing thoughts and connecting brains: material practices and the transition from individual to group-level prospective sensemaking. Acad. Manag. J.55, 1232–1259. doi: 10.5465/amj.2010.0890

73

StiglianiI.RavasiD. (2018). The shaping of form: exploring designers’ use of aesthetic knowledge. Organ. Stud.39, 747–784. doi: 10.1177/0170840618759813

74

StrleT. (2012). Metacognition and decision making: between first and third person perspective. Interdiscip. Descr. Complex Syst.10, 284–297. doi: 10.7906/indecs.10.3.6

75

SundaramurthyC.LewisM. (2003). Control and collaboration: paradoxes of governance. Acad. Manag. Rev.28, 397–415. doi: 10.2307/30040729

76

SunsteinC. R.HastieR. (2014). Making dumb groups smarter. Boston: Harvard Business Review

77

TsoukasH. (2005). Do we really understand tacit knowledge. Manag. Knowl. Essent. Read.107, 1–18.

78

VaaraE.MoninP. (2010). A recursive perspective on discursive legitimation and organizational action in mergers and acquisitions. Organ. Sci.21, 3–22. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1080.0394

79

Van EesH.GabrielssonJ.HuseM. (2009). Toward a behavioral theory of boards and corporate governance. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev.17, 307–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8683.2009.00741.x

80

VeltropD. B.BezemerP. J.NicholsonG.PuglieseA. (2020). Too unsafe to monitor? How board–CEO cognitive conflict and chair leadership shape outside director monitoring. Acad. Manag. J.64, 207–234. doi: 10.5465/amj.2017.1256

81

VeltropD. B.MollemanE.HooghiemstraR. B. H.Van EesH. (2017). Who's the boss at the top? A micro-level analysis of director expertise, status and conformity within boards. J. Manag. Stud.54, 1079–1110. doi: 10.1111/joms.12276

82

WatzlawickP.BeavinJ. (1967). Some formal aspects of communication. Am. Behav. Sci.10, 4–8. doi: 10.1177/0002764201000802

83

WeckM. K.VeltropD. B.OehmichenJ.RinkF. (2022). Why and when female directors are less engaged in their board duties: an interface perspective. Long Range Plan.55:102123. doi: 10.1016/j.lrp.2021.102123

84

WeickK. E. (1995). “Sensemaking in organizations (time, but it will amount to far less than the time you’ll devote to damage control after a miscommunication has dealt its blow)” in That’s what I have to say. make sense (Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications)

85

WeickK. E.SutcliffeK. M.ObstfeldD. (2005). Organizing and the process of sensemaking. Organ. Sci.16, 409–421. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1050.0133

86

WestphalJ. D.BednarM. K. (2005). Pluralistic ignorance in corporate boards and firms' strategic persistence in response to low firm performance. Adm. Sci. Q.50, 262–298. doi: 10.2189/asqu.2005.50.2.262

87

WestphalJ. D.ZajacE. J. (2013). A behavioral theory of corporate governance: explicating the mechanisms of socially situated and socially constituted agency. Acad. Manag. Ann.7, 607–661. doi: 10.1080/19416520.2013.783669

88

WoolleyA. W.ChabrisC. F.PentlandA.HashmiN.MaloneT. W. (2010). Evidence for a collective intelligence factor in the performance of human groups. Science330, 686–688. doi: 10.1126/science.1193147

89

YusF. (1999). Misunderstandings and explicit/implicit communication. Pragmatics9, 487–517. doi: 10.1075/prag.9.4.01yus

Summary

Keywords

boards, leadership, communication, joint sensemaking, corporate governance, theory-building

Citation

Engbers M, Khapova SN and van de Loo E (2024) Unsaid known in the boardroom: theorizing unspoken assessments of behavioral board dynamics. Front. Commun. 9:1347271. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1347271

Received

30 November 2023

Accepted

14 March 2024

Published

26 March 2024

Volume

9 - 2024

Edited by

Camelia Cmeciu, University of Bucharest, Romania

Reviewed by

Pedro Beltran Cuervo, Universidad La Salle, Mexico

Anca Anton, University of Bucharest, Romania

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Engbers, Khapova and van de Loo.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marilieke Engbers, m.j.e.engbers@vu.nl

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.