- 1Institute of Social and Cultural Anthropology, Faculty for the Study of Culture, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Munich, Germany

- 2Center for Information and Language Processing, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Munich, Germany

This article investigates discourse- and language-specific features of online anti-immigrant extreme speech in Germany. We analyze a context rich dataset collected and annotated through a collaborative effort involving fact-checkers, ethnographers and natural language processing (NLP) researchers. Using a bottom-up annotation scheme, we capture the nuances of the discourse and develop a typology of lexical innovations. The analysis combines thematic and critical discourse analysis with a linguistic perspective, revealing that direct forms of racism intertwine with argumentative forms of antagonism and playful word games within anti-immigrant discourses, in ways that center around narratives of victimhood and perceived threats from migrants. We further show how the specific conditions in Germany, including strict legal regulations of speech, have shaped the emergence of a non-standard language variety in and through anti-immigrant discourse, which helps the discourse community maintain group identity. The ethnographically backed analysis provides a granular understanding of the phenomenon of online extreme speech in the German context, contributing to the broader field of discourse studies and offering insights into the varieties within anti-immigrant discourse.

1 Introduction

Yes, we are doing well in Germany, but nothing was given to us. Thanks to our ancestors, who have built up everything laboriously and worked. And our oh so needy newcomers sit down in the made nest and are still rewarded for it, while we continue to toil to keep the country running reasonably. Everyone is the architect of their own fortune. Think about the bullshit that you write.

- An online post against immigrants in Germany1.

Anti-immigrant extreme speech has emerged as a prominent instance of polarization and right-wing populist discourse globally. Studies have shown how this kind of speech aims at tapping and stoking strong feelings of fear, alienation and resentment towards the immigrant community (Hameleers, 2021). Scholarship on right-wing populist mobilization in Germany has documented such trends since the 1990s (Klein and Falter, 1996), but more recent research has revealed that anti-immigrant and Islamophobic discourses have seen an increase, following refugee arrivals from war torn Syria in 2015 and incidents of Islamist terror in Europe (Awan, 2014; Hanzelka and Schmidt, 2017). Studies have documented a subsequent shift in public opinion from a largely welcoming or neutral stance toward immigration to one marked by deep divisions and widespread dissatisfaction with political processes and institutions, playing into the hands of right-wing populist movements like Pegida [Patriotic Europeans against the Islamization of the Occidental World], which instrumentalized the situation (Arlt et al., 2020). Much research has attributed social media a central role in the success of populist voices, showing how it has created new ways of targeting social groups which have been historically oppressed and have long been the subject of xenophobic angst in the country (Krämer, 2014; Schaub and Morisi, 2020) as well as elsewhere in Europe (Lentin, 2016; Törnberg and Wahlström, 2018; Siapera, 2019).

We contribute to this important stream of scholarship on online right-wing populism by moving beyond methods where academic researchers alone gather and label data, and instead develop and analyze a context-rich annotated dataset, which was developed through a process of collaborative data gathering and coding involving factcheckers, ethnographers and AI developers (NLP researchers). In turn, based on ethnographically derived categories that emerged during this collaborative process, we offer a granular annotation scheme to examine anti-immigrant discourses.

Our departure in this study is the concept of “extreme speech,” which emphasizes the situatedness of online speech in different cultural and political contexts as well as historical sensibility that challenges presentist and technocentric arguments about contemporary right-wing politics (Udupa et al., 2023). This approach therefore has two key dimensions: (1) online vitriol is not the result of a sudden crisis instigated by social media but has longer historical roots, and (2) meanings and implications of extreme expressions can be traced more fully with a bottom up understanding of emic perspectives rather than frameworks applied from outside. Thus, our approach gives a central place for community collaboration in identifying, evaluating and annotating problematic content, departing from identifying such content using universal definitions or securitized discourses.

Based on content and linguistic analysis of a dataset of 2,355 anti-immigrant passages collected through a collaborative coding process in 2021–2022, we present illustrative examples of the discursive worlds that anti-immigrant actors have developed in Germany and advance two observations. First, we show that while overt forms of racism are prevalent in online anti-immigrant discourse, they exist alongside more covert expressions of racism embedded in themes such as self-victimization, hyper-nationalism, anger towards political elites, and skepticism towards refugees specifically. Probing this latent hostility, we introduce the concept of “argumentative racism” that articulates its racist messages by formulating complex arguments that may not appear racist at first glance. Second, anti-immigrant discourses have developed a distinct variety of non-standard language usage patterns and lexical innovations. Presenting a typology of lexical innovations, we suggest that this key aspect of xenophobic discourses makes automated detection of extreme speech even harder.

These linguistic developments are influenced, in part, by regulatory conditions like Germany’s Network Enforcement Act (NetzDG)2, which sets lower thresholds for speech violations compared to First Amendment protections in the US (Bleich, 2014). However, as we discuss in the next section, extant thematic and lexical dimensions of anti-immigrant discourse are not merely a result of strict regulations but are shaped by longer historical patterns which are at the same time reconfigured as social media channels have expanded and broader contexts of migration have shifted.

We begin this qualitative critical discussion by first outlining recent anthropological and communications scholarship on online anti-immigrant and populist discourses and situating them in the longer trajectory of anti-immigrant sentiments in Germany. Presenting our methodological departures, we will subsequently present key results of our collaborative methodology by organizing them under two sections—thematic analysis and linguistic analysis—of discourse specific features. We will conclude by discussing the implications of these findings for content moderation and methodological way forward within digital hate scholarship.

2 Right-wing populism and anti-immigrant sentiments in Germany

As scholarship across different disciplines has highlighted, populism as an ideology counterposes an imagined construction of ‘the people’ against an out-group, claiming to be democratic by representing the ‘silent majority’ (Kazin, 1998; Canovan, 1999). Populist logic opposes ‘the people’ vertically to an elite, and in many cases articulates with the nationalist axis and opposes ‘the people’ horizontally to immigrants and minorities (Rensmann, 2006; Krämer, 2014; Brubaker, 2017). The anti-immigration narrative has always been central to the success of right-wing populists. Already in 2002, no populist party in Western Europe performed well in elections without activating resentment towards immigrants, while electoral success without mobilizing resentment towards elitism or economic changes was achievable (Ivarsflaten, 2008).

In Germany, the rise of right-wing populism has been observed at least since the 1990s, and the construction of cultural differences and controversies over ‘the Other’ have mirrored German’s national identity for long (Thränhardt, 2002; Wilhelm, 2013). Importantly, the term “migrants” in such discourses has had multiple referents, and the evaluative stances associated with them have in turn differed. Shaped by domestic clash of interests and ideological tussles, migrants were demarcated into different types with shifting understandings of who were desirable and who were not. In post-world war II Germany, “refugees” were considered as suffering from communism in the Cold War; Jewish immigrants were recognized as a symbol of “Germany’s rejection of Nazism”; and guest workers were seen as a proof of the prosperity of the country’s economy (Thränhardt, 2002, p. 346).

Against this variegated reception and framings of different types of migrants, recent years have seen a rise in online abuse against Muslim migrants and greater prevalence of Islamophobia (Awan, 2014). This rise is associated with what was seen as a “crisis” following former Chancellor Angela Merkel’s optimistic “wir schaffen das” statement [we can do this], which paved the way for more than one million refugees from war-torn Syria alongside Afghanistan and Iraq to enter Germany in 2015 as well as public perceptions of dangers following Islamist attacks in different parts of Europe (Hanzelka and Schmidt, 2017). Having been on the peripheries of the political spectrum until then, right-wing populists instrumentalized the situation, mobilizing popular movements such as “Pegida” to organize major protests on the streets, supporting the rise of the right-wing party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) and promoting mistrust regarding the truthfulness of media coverage on refugees and immigrants (Stier et al., 2017; Arlt et al., 2020). This was compounded by the decline in traditional parties’ representative function, which helped the electoral success of right-wing populist actors in Germany and across Europe (Kriesi, 2014; Inglehart and Norris, 2017). For instance, Pegida and AfD effectively tapped “a more general surge in populist sentiment in the country” (Stier et al., 2017, p. 4) reflected in concerns over media bias and criticism of the political class for its distance from citizens (Dostal, 2015; Garnett, 2018).

“Populist atmosphere” in Germany reflects the broader political climate in present day Europe. Based on attitude surveys in Germany, Mudde explains how xenophobia and anti-immigration attitudes are at the heart of European culture and not only in its extreme margins, explaining populist right wing views as “pathological normalcy” (Mudde, 2010, p. 1167). Similarly, Siapera’s research on racist discourse in Ireland shows how supremacist discourses have blended with racial and ethno-nationalistic “common sense,” sustaining exclusionary and discriminatory practices towards racialized others (Siapera, 2019, p. 25).

2.1 Social media and anti-immigrant discourses

Much research has attributed social media a central role in the success of populist voices in Germany (Krämer, 2014; Schaub and Morisi, 2020). Compared to more centrist attitudes, populist activists deliberately take advantage of the possibilities of social media to bypass traditional media, allowing them to express an unfiltered relationship to ‘the people’ who are, according to their narrative, being silenced by the elites (see Jacobs and Spierings, 2019; Schmuck and Hameleers, 2020). Although some studies have suggested that social media platforms are important for populists because of the possibility to bridge the distance between ‘fringe’ and ‘center’ by bypassing legacy gatekeepers (e.g., Batorski and Grzywińska, 2018), several studies have demonstrated that movements like Pegida not only attract members of the so-called fringe communities, but they fan and tap political attitudes of a significant portion of the German population who feel detached from the political system (e.g., Heim, 2017).

A large number of these studies have utilized content analysis as the basis of their arguments (e.g., Jagers and Walgrave, 2007), employing different features of social media content as units of analysis, often in combination with other types of “real world” data or implications for actual physical events. Kaiser (2021) has researched the connections between anti-refugee pages on Facebook and local mobilizations of such groups, and how physical attacks against refugee shelters are coordinated on Facebook pages dedicated to different regional groups of the Pegida movement. Aslanidis (2018, p. 1251) has measured populist discourse with a “clause-based semantic text analysis.” Hanzelka and Schmidt (2017, p. 143) use samples of user comments on Facebook pages of Pegida to identify and measure the percentage of hateful comments and its relation to “trigger events” by using a qualitative coding method, finding that the largest hate speech “triggers” in these groups are connected to incidents in which refugees and immigrants are portrayed as perpetrators as well as topics of asylum policy more generally.

In addition to research focused on the impact of social media, extensive studies are available that delve into news coverage and the overarching discourse related to anti-immigration narratives. With a “historical/critical discourse analysis” of German newspaper coverage between 2015 and early 2016. Vollmer and Karakayali (2017, p. 118) examine the discourse on refugees and the rise and reinvigoration of new and old topoi, observing “discursive shifts” influencing the “configuration of migration categories such as migrant or refugees.” Lichtenstein (2021, p. 267) deploys a “standardized content analysis” to observe changes in media frames of news coverage of the “migration crisis” in German public broadcasting news as well as infotainment formats and their relation to communication by the German government following the New Year’s Eve incident in Cologne in 2015 which involved molestation of women party goers.

Studies using computational methods, for example, Griebel and Vollmann (2019, p.1) have examined how migration was represented in German political discourses during the so-called refugee crisis (2015–2017) by conducting a corpus-based study that combines a quantitative approach focusing on collocations with a qualitative critical discourse analysis (CDA) of “culturalization regimes,” revealing different “discursive coalitions” in a left-wing and a conservative German newspaper based on values of openness and closure, respectively. Frequent keywords and collocations of a set of search terms related to migration, like “Flüchtling” (refugee), are used as statistical cues for lexical formations typical of a discourse as represented in corpus subsets. This study shows how the left-leaning newspaper tends to support an open society, although with instances of contested elements of closure, and the conservative counterpart leans more towards closure and problematizes migration, while also presenting a range of perspectives that depend on the perceived usefulness or perceived threat of people coming to Germany.

Similarly, De Smedt and Jaki (2018, p. 35) created an online corpus of political debates in Germany, consisting of 125,000 tweets posted around the 2017 federal election, to uncover discourse topics used by different political factions by extracting keywords from corpus subsets. They show that fans of the right-wing populist party AfD write about “Islam, refugees, crime, and left-wing voters (Gutmenschen, Linksfaschisten)” and that hate speech is often associated with racial slurs as well as “references to violence, danger and death” (De Smedt and Jaki, 2018, p. 36). In their extensive examination of a large-scale corpus of Facebook and Twitter data, Baumgarten et al. (2019, p. 1) conducted a comparative analysis of “linguistic instantiations of hate speech” in both the German and Danish contexts. Their investigation shows obvious as well as covert forms of hate speech directed at minority groups, with a particular emphasis on Muslims, and they further identify discourse specific slurs, “dehumanizing metaphors” and linguistic patterns.

Heiss and Matthes (2020) conducted a content analysis of 13,358 Facebook posts by Austrian and German political parties as well as their respective candidates to understand the “potential reciprocal relationship” between right-wing populist communication and anti-immigrant attitudes, anti-elitist attitudes, and the expression of anxiety or anger. Their findings reveal that right-wing actors in both countries exhibit a pronounced proclivity for employing anti-immigrant attitudes in their discourse, surpassing all other actors examined in that context (Heiss and Matthes, 2020, p. 303). In order to understand the social media tactics of the German right-wing party AfD, Serrano et al. (2019) employ a “unified multi-platform analysis” encompassing data derived from prominent social media platforms related to Germany’s leading political parties. They found that the AfD demonstrated “online superiority” (p. 214) over other parties, attributed in part to the influence of social bots. The study also highlights the AfD’s strategy of spreading anti-immigration sentiments to bolster its popularity on social media (Serrano et al., 2019).

Paasch-Colberg et al. (2021) provide a “modularized framework” to differentiate between several forms of hate speech and offensive language targeting immigrants and refugees, conducting a structured text annotation of user comments on German news sites, Facebook pages, YouTube channels and a right-wing blog. With an aim to overcome the challenge of a “hate/no-hate dichotomy” (p. 177), they combine qualitative text annotation with “standardized labeling,” “in which hate speech is not directly identified by coders but results from …[a] combination of different characteristics,” which they identify as “negative stereotyping, dehumanizing speech and expression of violence” (p. 172). Similarly, Gründl (2022) and Puschmann et al. (2022) have developed automated dictionary-based content analysis approaches to measure official populist communication and right-wing populist conspiracy theories in the German speaking context on social media.

3 Methods and data

Our method differs from extant approaches in two ways. Building on the extreme speech framework, we identify speech as located within a field of power, which is historically constituted and conjunctural, and therefore, the severity and implications of hateful content cannot be gauged by looking at the content of the passage alone or with academic coders alone (Udupa et al., 2023). We address the first problem by combining content features of extreme expressions in combination with identifying the target groups and the linguistic means to disseminate the speech. Extreme speech theory emphasizes that the same extreme expression can be subversive or repressive based on who uses it, against which groups and under what historically shaped conditions of power. This compounds the problem of annotation, leading to limitations of labeling using predetermined characteristics of problematic speech.

We have sought to address this second problem by building on existing work in the German context, but developing it further. This was achieved through our ethnographically backed analysis which not only involved collaborative data gathering but also integrated emic perspectives and contextual knowledge through several rounds of interactions among factcheckers as community intermediaries, anthropologists, and NLP experts. We partnered with five factcheckers in Germany in a multinational team of collaborators. Their input guided multiple iterations of the annotation framework, prioritizing their insights in evaluating content across platforms. Initial annotations by factcheckers laid the groundwork for subsequent annotations and analysis by anthropologists and NLP experts.

Alongside iterating the annotation scheme, factcheckers were requested to gather extreme speech passages from different social media platforms and label the passages. Each gathered passage ranged from a minimum sequence of words that comprises a meaningful unit in a particular language to about six to seven sentences. The project did not specify which social media platform to source the passages from, and followed factcheckers’ knowledge about relevant platforms. Factcheckers in Germany collected the passages from Twitter, YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, Telegram, and comments posted on social media handles of news organizations, right-wing bloggers, or politicians with large numbers of followers.

In the first level of coding, factcheckers categorized them into three types: “derogatory extreme speech” to denote expressions that do not conform to accepted norms of civility within specific regional contexts, “exclusionary extreme speech” expressions that call for or imply exclusion of historically disadvantaged and vulnerable groups from the “in-group” (Udupa et al., 2023, p. 4), and “dangerous speech,” including expressions that have a reasonable chance to trigger harm and violence against target groups (Benesch, 2012). Further, target groups for each instance of labeled speech were marked. After the completion of this process, 50% of the annotated passages were cross-annotated by another factchecker to check the interannotator agreement scores. Cohen’s kappa (κ, McHugh, 2012), Krippendorff’s alpha (α, Krippendorff, 2011), intraclass correlation coefficient (two-way mixed, average score ICC(3, k) for k = 2; Cicchetti, 1994) and accuracy were measured, which is the percentage of passages where both annotators agreed (Maronikolakis et al., 2022). For the three labels of derogatory, exclusionary and dangerous speech, we obtained the values of κ = 0.23, α = 0.24 and ICC(3, k) = 0.41, which is considered “fair” (Cicchetti, 1994; Maronikolakis et al., 2022).

Following this phase, and also during each step of the annotation process, we clarified the categories through different rounds of discussion with factcheckers. Anthropologists played a crucial role in initiating the framework and guiding discussions to understand culturally and contextually specific nuances in extreme speech. Based on the exchanges, we also refined the list of target groups and engaged in further discussion when substantial disagreements among factcheckers surfaced. These discussions were part of a reflexive process in which anthropologists and factcheckers were simultaneously highlighting their experiences of navigating such online materials, and thereby iteratively calibrating the labels to determine the meaning and implications of passages. Through this process, we obtained 5,000 extreme speech passages from social media conversations in Germany appearing between February and April 2021.

Following our theoretical framework of assessing the content in combination with target groups, we checked which types of extreme speech were common against different target groups identified in the annotation scheme as ethnic minorities, immigrants, religious minorities, sexual minorities, women, racialized groups, politicians, legacy media, the state, civil society advocates for inclusive societies, and any other. This initial check revealed that immigrants were the largest target group in the German dataset, prompting us to take up anti-immigrant discourse for closer inspection. Of the total 5,000 labeled passages, 47% (2,355 passages) were marked as directed against immigrants. Of them, factcheckers labeled 1,315 passages as exclusionary, 1,038 as derogatory, and 2 as dangerous. Following the factcheckers’ annotation of the initial dataset, two of the authors, both anthropologists, devised another annotation framework specifically tailored for the predominant target category within the dataset, namely immigrants.

Subsequently, an anthropologist on the team carried out detailed qualitative content coding of this corpus, building on some of the key pointers from first level coding done by factcheckers, as the foundation for both our subsequent analyses: thematic analysis and lexical discourse analysis. We adopted theoretically informed inductive thematic coding, employing a bottom-up approach and deriving labels for themes and styles of anti-immigrant extremist speech from our ethnographic research on right-wing nationalist discourse online, supplemented by relevant literature (Aslanidis, 2018; Paasch-Colberg et al., 2021; Puschmann et al., 2022) and dialogues with factcheckers. One of the authors (LN), proficient in both German and English, conducted the coding, identifying themes and styles by examining passages in their original language within the posts and clustering the segments into overarching themes and styles based on their content.

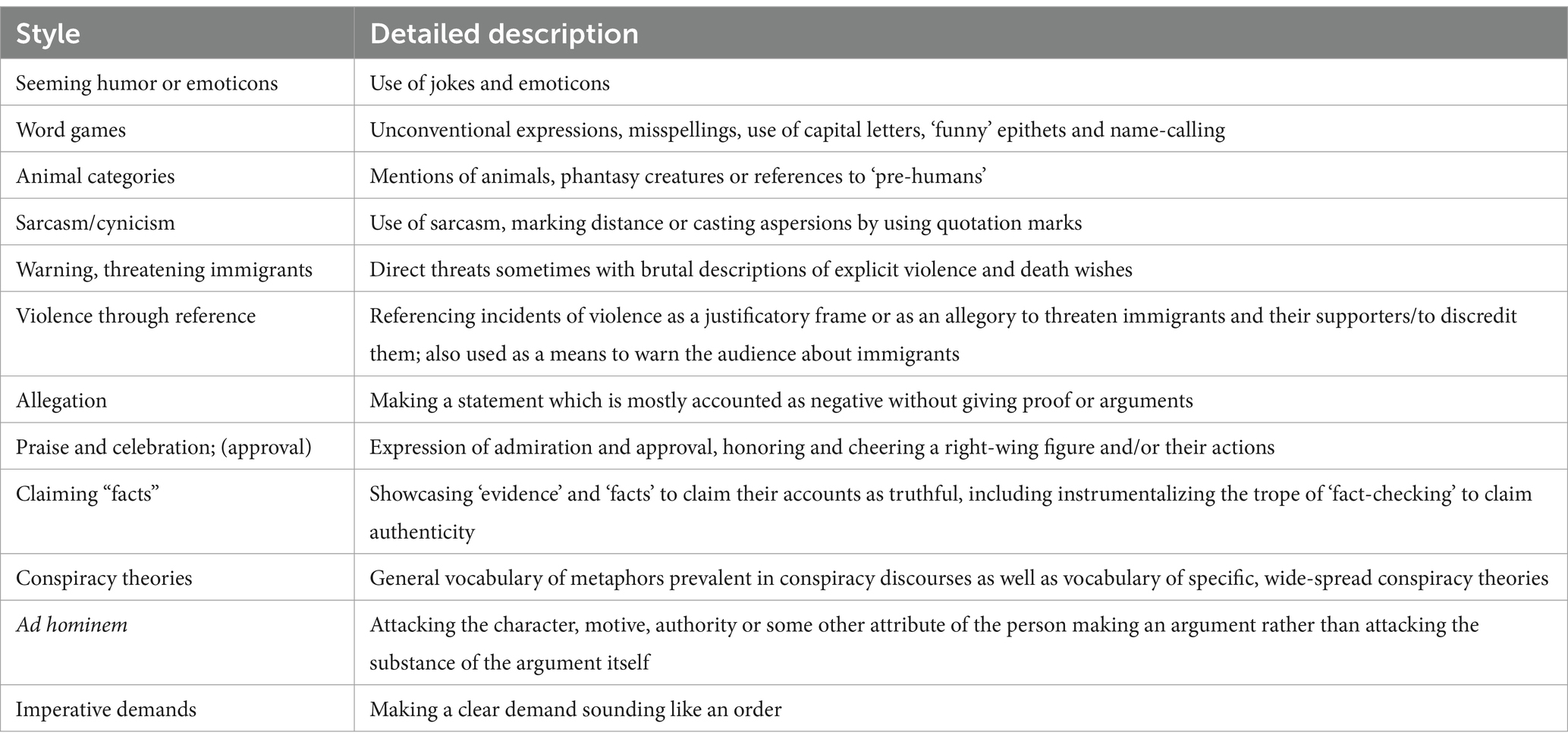

The annotator could assign up to two labels for each category per passage (see Tables 1, 2). We adopted a multi-label classification system due to the observation that many passages exhibited a combination of multiple themes and styles. This decision was made to accommodate the complexity of the content, allowing each text to be assigned two labels within a category. Any additional fitting labels beyond the two major themes or styles were noted under “comments” in a separate column. The labels provided in the comments section were not included in the analysis presented in this paper. Instead, this option was offered as supplementary information intended to facilitate the examination of sections where more than two labels were apparent. While these additional labels were not formally incorporated into the primary analysis, they served as valuable context for understanding the complexity and nuances within passages that exhibited multiple thematic or stylistic elements.

To determine the inter-annotator agreement for this thematic coding, 50% of the texts in the corpus were cross-annotated by a second annotator who is also an anthropologist and native German speaker fluent in English. Since the annotation scheme of our content coding is a multi-label classification, i.e., each text could receive more than one label of a category, we first determined the overlap accuracy, which is the agreement on one or both labels in percentage, as a simple agreement measure for each category. We then calculated Cohen’s kappa for each individual label of a category, effectively turning the task into a binary classification per label, allowing for a differentiated analysis of the agreement between the annotators for different labels. Finally, the average kappa value across all labels was calculated as a summary agreement measure. The category concerned with the themes of anti-immigrant discourse has an overlap agreement of 79% and the Cohen’s kappa average is 0.38.3 The category used to analyze the styles used to disseminate the anti-immigrant message has an overlap agreement of 78% and a Cohen’s kappa average of 0.34. Both these measures indicate a notable agreement between the two annotators for themes and styles in anti-immigrant extreme speech.

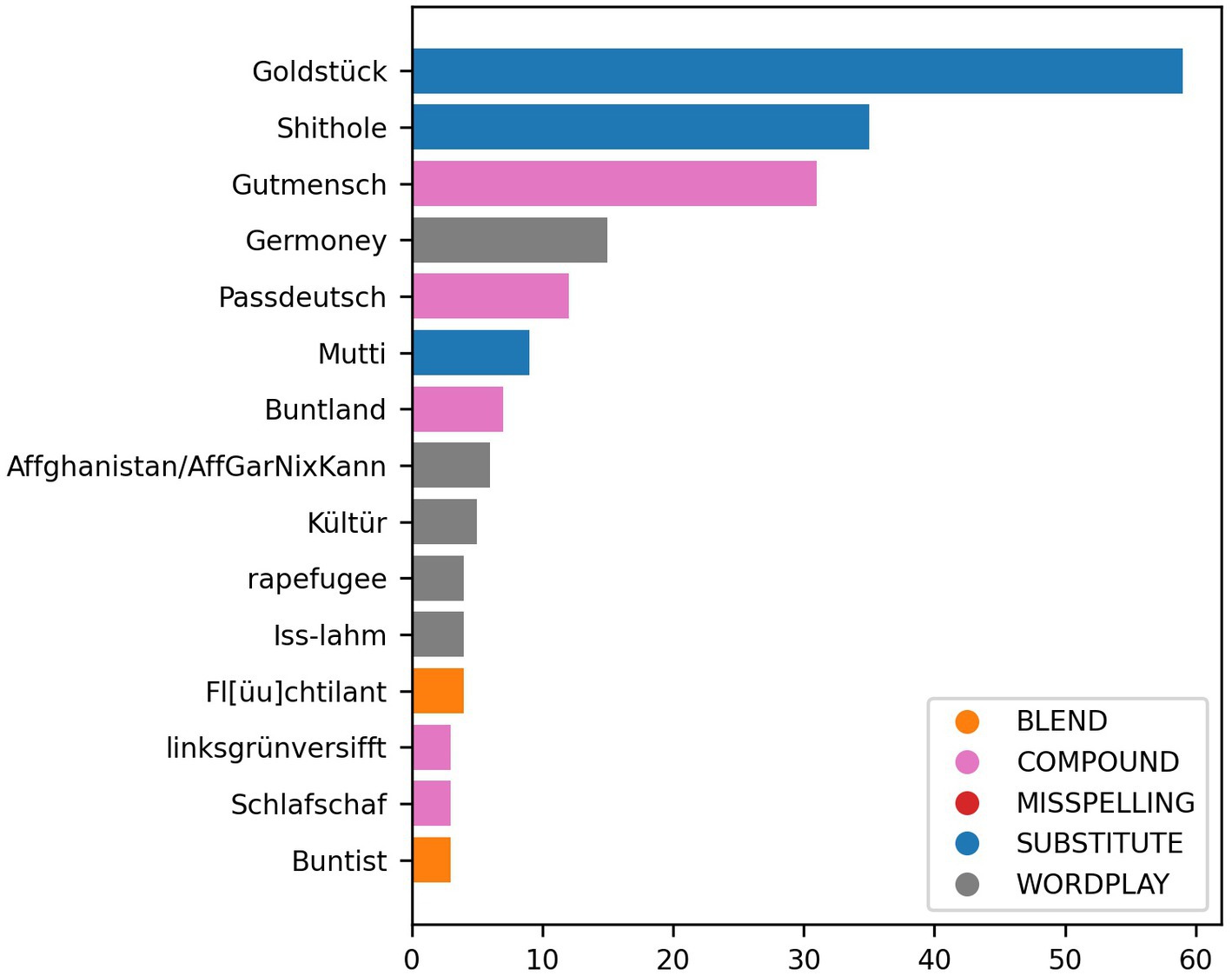

Additionally, during the annotation process and as the foundation of the linguistic analysis, we analyzed the frequency distribution and linguistic characteristics of neologisms, substitute words, word games, and alternative spellings in the corpus, extracted during the translation of texts into English. We used translatability as a criterion, selecting expressions lacking English counterparts in automatic translation or not translated accurately with their context-specific meaning. This method allowed us to pinpoint discourse-specific elements. After categorizing these expressions based on different types of lexical innovation (see Figure 1), we excluded slurs, which constitute a significant portion of innovative lexical items in anti-immigrant discourses. Instead, we focused on other, more nuanced forms of lexical innovation beyond mere insults in online extremist speech discourse, exploring the conditions and forces shaping its language. By considering the frequency of these extracted expressions featuring lexical innovation in the corpus as an indicator of their entrenchment in the lexicon of this sociolect, we compiled a list of discourse-specific expressions.

Figure 1. Frequencies of a manually selected subset of discourse-specific expressions featuring different types of lexical innovation that appear in more than 2 of the 2,355 texts, considering spelling variants via pattern search with regular expressions.

4 Results

In the following discussion, we present the analysis in two sections. The first encompasses a thematic analysis, examining themes and styles of the content. The second section is dedicated to a lexical discourse analysis, specifically focusing on the typology and sources of lexical innovations within anti-immigrant extreme speech, conceptualized as a form of “anti-language” as defined by Halliday (1976, p. 570).

4.1 Thematic analysis

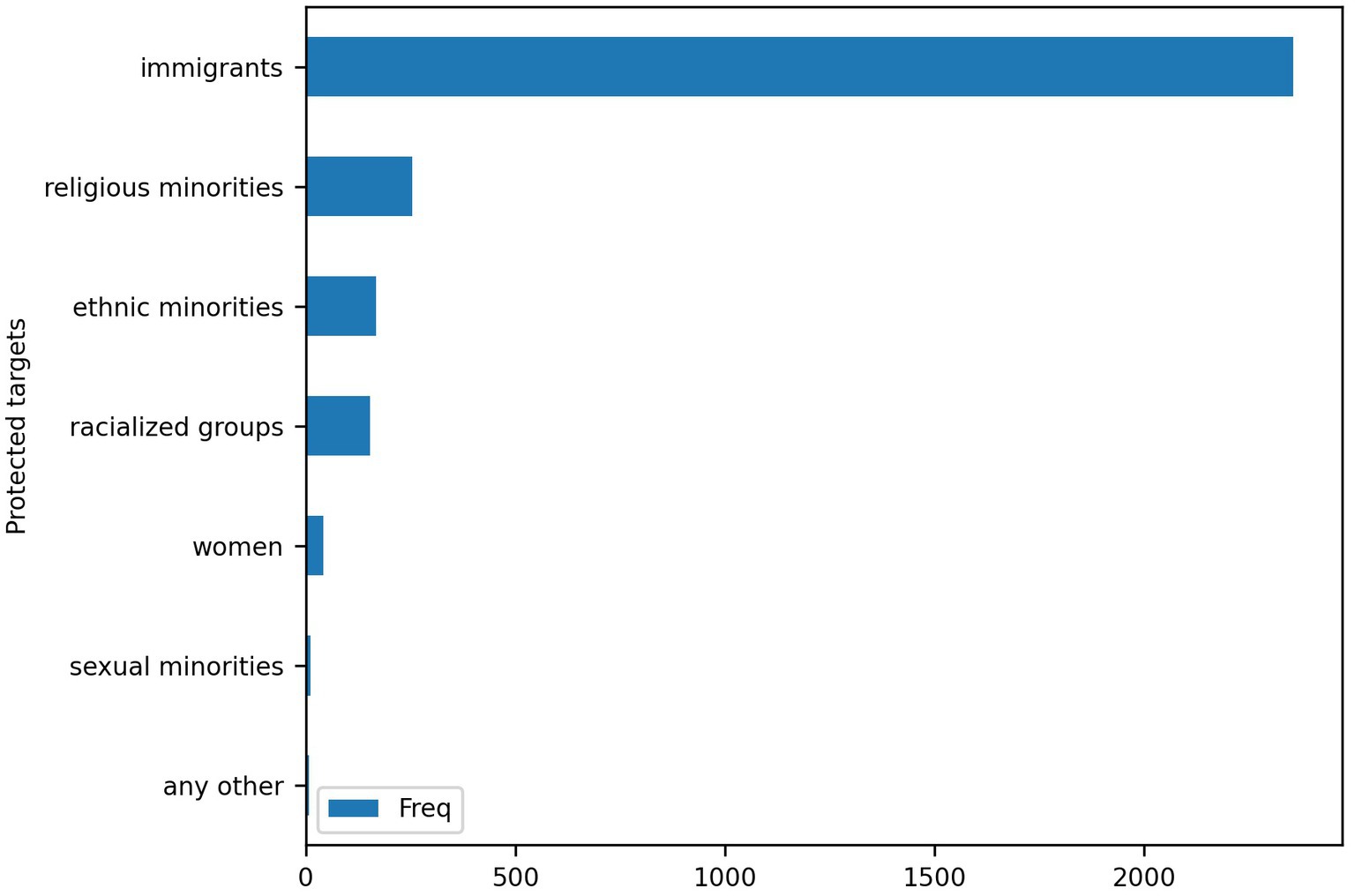

Our first observation relates to co-occurring target groups in a single passage. In the first level of coding, factcheckers could choose up to two main target groups for a passage. Among instances where immigrants were marked as targets, factcheckers identified 636 passages as containing one other target group, including religious minorities, ethnic minorities, racialized groups, women and sexual minorities (see Figure 2)4.

The most common target label that went together with immigrants was “religious minorities” with 254 passages, revealing that message posters marked immigrants largely in terms of religion. The second most common target label was “politicians” with 166 passages, suggesting that anti-immigrant discourse and anti-politician rhetoric are closely connected in the discourse.

This initial phase of annotation by factcheckers was followed by theoretically informed inductive thematic coding conducted by anthropologists, as explained in the previous section. This thematic analysis forms the basis for subsequent results we present below.

4.1.1 Themes

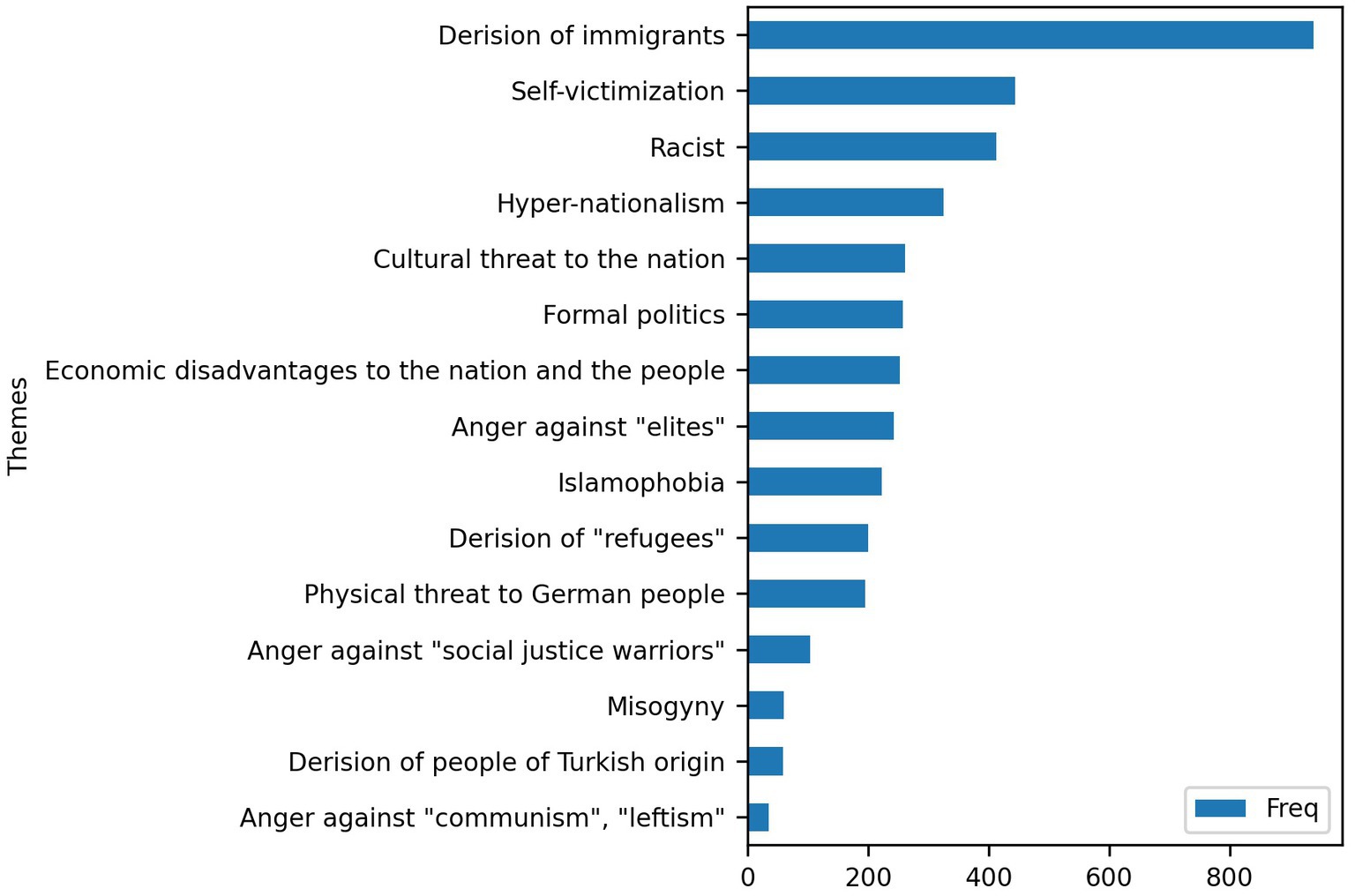

The thematic elements of anti-immigrant discourse, which we illustrate with examples, range from directly racist and Islamophobic messages to concerns about threats and economic disadvantage to the nation as well as anti-elite sentiments (see Table 1 for themes; see Figure 3 for frequency of themes).5 The examples presented here contain objectionable language and tropes, which we do not endorse in any way but cite them with the objective of advancing a critical discussion. The examples presented here were originally written and analyzed in German and translated into English for this paper.

Owing to the very nature of the sampled data, direct derision of immigrants was the most frequently occurring theme with 940 passages. Such expressions construe immigrants as having an excessive number of children and taking undue advantage of state welfare:

…thats how it is. The first thing they do, when they get their first money, is to run to the office and ask for more money, because smoking is so expensive here.

And the child benefit comes still in addition, here they make twice as many children as at home, where they also already make too many.

Although messages express widespread disdain towards immigrants in general, there were also direct comments against refugees marked distinctly as recent arrivals in 200 passages. In these passages, refugees were linked to the war in Syria, partly reflecting the period of data collection which was before the arrivals of Ukrainian refugees. Framing them as “war children,” posters portrayed them as having no inhibitions or respect for other cultures, of being ungrateful for the accommodation and support they receive and of being more likely to be supporters of IS:

Example 1: Instead of introducing WAR CHILDREN who bring the war right along because they know nothing else and have no inhibitions or respect. Do not know where borders are and do not want to integrate anyway. One should help them only in the homeland. Or give them the bare necessities. 😉

Example 2: Now first of all IS supporters from Syria are rescued ...., and then there is the refugee camp on Lesbos and the uninvited hotel guests on Gran Canaria....

Social media commentators also drew a distinction between refugees who were escaping the war and migrants who enter the country to seek ‘profit’, reproducing the thinking that economic migrants are not ‘real’ refugees (van Dijk, 1998) and moreover, are prone to violent behavior:

Well, if you let the pack, sorry I meant economic refugees, in our country it results in something like this!!! Who reads the latest crime section, notes that is unfortunately not an isolated case! Foreigners are therefore more often involved in serious crimes, that’s a fact. Here unfortunately no Gutmensch [do-gooder] theory of left ecological spinners helps!

However, many passages demonstrate that the distinction made is not rigorous but fluid, suggesting that refugees may not be “risk[ing] their lives to “escape” from these countries” (passage from dataset), but seeking to exploit Germanys’ social funds instead of contributing to the economy. Contradicting media reports, these passages claimed that refugees are unskilled and therefore unable to contribute to the country’s prosperity. The dataset does not contain instances of mockery towards economically successful migrants or skilled workers.

Nationalist tropes, which comprise some of the largest thematic strands, deeply frame the anti-immigrant discourse. Nationalist and xenophobic tropes were expressed in different ways — through self-victimization in 444 passages, hypernationalism in 325 passages, cultural threat to the nation in 261 passages, physical threat to German people in 195 passages, Islamophobia in 222 passages and economic disadvantages to the nation and the people in 253 passages. For instance, comparing Syria with Germany after WWII, a post stated how German peoples’ ancestors did not flee Germany after the war, but instead acted patriotically, and stayed to build up the country. Such hypernationalist tropes raised a drumbeat around Germany’s achievements in the fields of culture and economy, praising German culture and priding how patriotic Germans would do anything, including the use of arms, to protect the country and urging fellow Germans to kick out the immigrants.

Nationalist sentiment was pronouncedly expressed in what we marked as the trope of self-victimization, which was the second most common theme in the overall dataset. These passages make use of the vocabulary around how ‘good German people’ are victims of the ‘migration crisis’, facing a difficult situation of not being able to access benefits they deserve while immigrants—the “freeloaders”—reap them:

Example 1: The inner cities are then full of freeloaders from all over the world, who get the rent paid by the state and the German taxpayers, who finance this, have to live in the prefabricated housing on the outskirts of the city.

Example 2: And the German pensioners who have partly rebuilt our country have to collect bottles so they have something to eat. Poor Germany, as a woman you are afraid to go out on the streets in the evening, and then some wonder where our... hate comes from…

Self-victimization extended to perceptions of different kinds of threats — cultural threat to the nation, physical threat to German women because of the perceived sexually violent male immigrants as well as economic threat because of welfare drain:

Of course, we cannot integrate them at all. They are only meant to destroy us as an ethnic group and culture. They are supposed to destroy the largely homogeneous peoples and cultures of Central Europe (the innovation workshop of the world), take away our civilizational and technological progress, make us ready for the NOW [New World Order: conspiracy theory originating from the 1990s, warning about the rise of a supranational world regime built by elites and secret societies]. Or at least eliminate us as competitors to China and the USA.

Nationalist tropes came with another common populist sentiment—a feeling of being left behind by the political establishment and the state. It is expressed as anger against elites in 243 passages and skepticism towards formal politics in 258 passages:

Asylum industry is a flourishing business with turnover and profit of several hundreds of billions of euros for all involved, from traffickers to high-ranking politicians and government officials. That is why all those who have conquered the place at this “feeding trough” praise so-called “welcome culture.” Number of votes for Red-Green lobby of this culture shows how seriously ill German society is.

Skepticism towards legacy institutions like the mainstream media, the state, the centrist political parties, left-wing activists and parties as well as the green party is widely present:

Germany is run down any way, no matter in red-green, black-red or black-green [referring to left, center, green political parties]. This country is only attractive for millions of Africans/Arabs without school education.

Reflecting the period of collection, extreme speech against politicians was largely directed at the then Chancellor Angela Merkel, sometimes using misogynistic messages, as found in 60 passages. Aside from an aversion towards the political establishment and its members, there were similar expressions aimed against the so-called social justice warriors in 104 passages:

For our left-green do-gooders, the #Umvolkung [general fear of replacement of the German people by an “other” population] cannot go fast enough. I just wonder what they want to live on with the #refugees when the high achievers have left the country.

“Left-green do-gooders” are blamed for bringing foreign people into the country and causing trouble for ‘the German people’. They are ‘warned’ of the threats that immigrants pose.

Importantly, the anti-immigrant discourse was prominently driven by passages that had an overt racist content or what Lentin (2016) describes as “frozen” racist themes, found in 413 passages. Explicit racist content comprised the third most frequent theme in our dataset. Such employed a specific vocabulary to discriminate based on assumed natural and cultural differences. This vocabulary serves to homogenize groups, create polarization, and reinforce the naturalization of cultural differences. It also hierarchizes and negatively evaluates those considered ‘Other,’ while justifying and legitimizing power differences, economic exploitation, and various forms of social and political exclusion (Wodak and Reisigl, 2015, p. 578):

Example 1: I also have friends, they are not all like that. But the reality is different. Unfortunately, what you just reported is a minority. Most of them, at least 80 to 90 percent, are junk. Merkel’s n* belong in the kennel.

Example 2: The WOMEN BUTCHER looks as if he could not dull a little water [German saying meaning that somebody seems innocent]! They all look like that! Sometime one will have to bring the FORBIDDEN WORD GENE into the conversation! THESE ARE AFGHAN GENES that such people have stored away for hundreds of years. This was always handled in AFGHANISTAN in such a way, for centuries and this is stored in the hereditary property of them! They do not know it at all differently!

Expressions of “biological racism” figured alongside “cultural racism” and civilizational difference, proposing that immigrants are culturally so far apart that they can never be integrated:

All those raised in an archaic culture are ticking time bombs. Even if they live unobtrusively and seemingly integrated in Europe for several years, at some point the medieval culture breaks through again. You can see it in this case and also with the man who pushed the boy in front of the train in Frankfurt. Why do not we make sure that all those whose culture is completely incompatible with our European one are deported immediately?

While such direct racist expressions with discriminatory othering were present, anti-immigrant discourse is driven by a variety of other tropes as discussed earlier. Importantly, most of these messages marked recent arrivals from Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq as ‘problematic’, while the longer patterns of Turkish guest worker migration were exempt from such hostile framing. Derision of people of Turkish origin was the second least frequent theme in the dataset with 59 passages, suggesting that although Turkish immigrants have had a contested position in Germany since the 1970s (Wilhelm, 2013), the more recent right-wing populist discourses in Germany have directed their anger against latest arrivals of refugees and asylum seekers from Muslim majority countries and Africa. Homophobia and hate against the LGBTQI+ communities were nearly absent in the dataset.

4.1.2 Styles

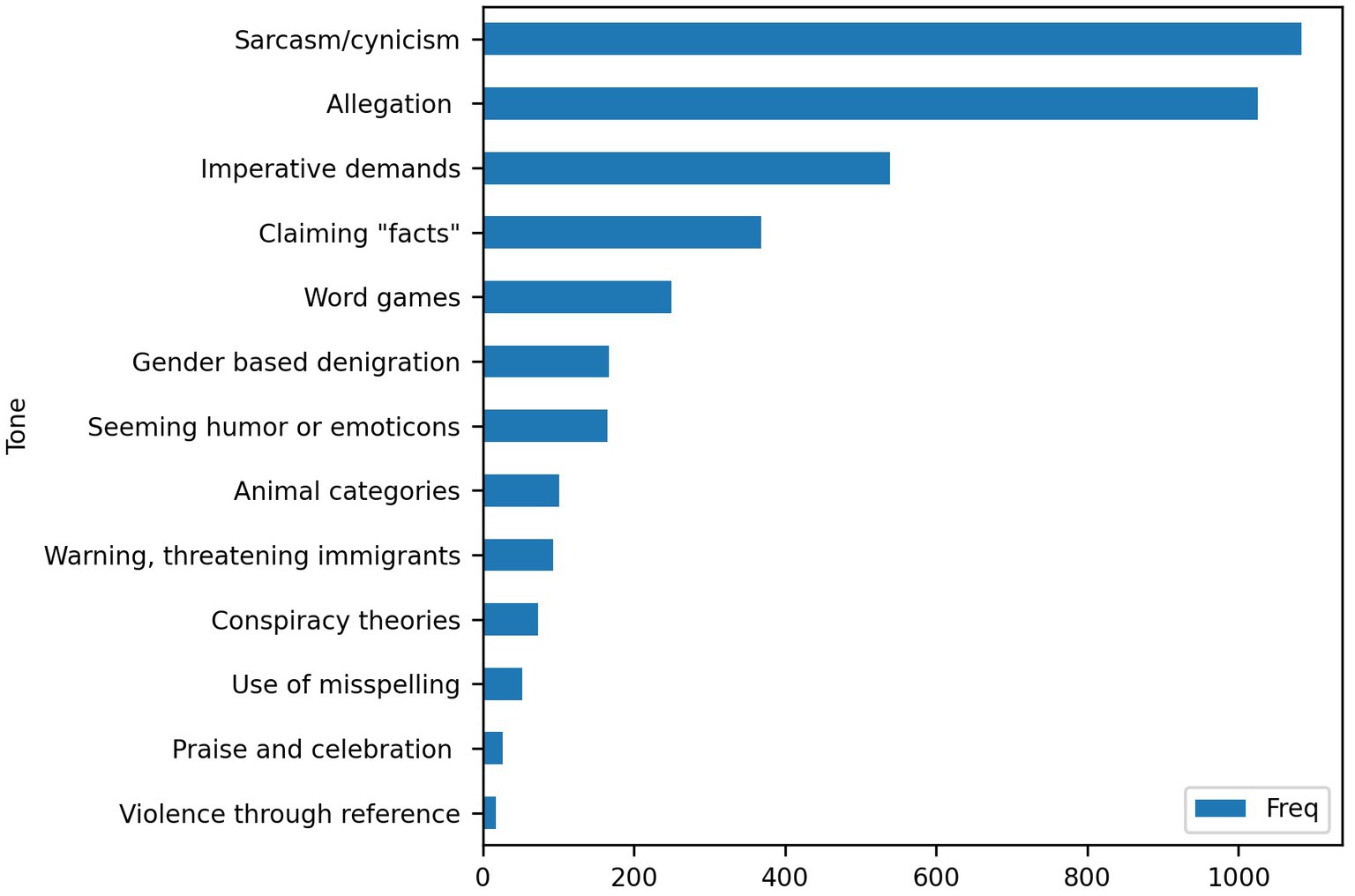

The second annotation category, which examined the style of the passages, shows noteworthy discourse specific characteristics (see Table 2 for styles; see Figure 4 for frequency of styles). We define “style” as the distinctive manner or approach in which anti-immigrant discourse is presented or expressed through language.

The most dominant style in the dataset is sarcasm and cynicism with 1,083 passages. With the use of sarcasm and cynicism in nearly every second passage, we observed how this style was widely used to portray a sense of dominance and superiority, by engaging with the “fun” of exchanging such expressions (Udupa, 2019). This was illustrated by the vast use of word games and misspellings in 302 passages, humor and emoticons in 165 passages or animal categories in 101 passages to degrade and ridicule immigrants and people who supported immigration:

Example 1: I see. If the foreigners behave decently, the Umvolkung is “perfectly okay.” Well then go back to sleep.

Example 2: The many poor n*, Arabs, Islamists, etc. have to go somewhere! If no state wants the invaders, ultimately only Doitscheland [“Deutschland” written incorrectly] remains!

The second most common style of making allegations was found in 1024 passages:

Many Kuffnucken [pejorative term for immigrants] asylum cheats also have no desire to sweep the streets, because drug trafficking is much more lucrative!

The third category of imperative demands with 539 passages portrays the same felt sense of superiority and authority and the right to make such statements:

Deeds must come and the best the day before yesterday! Kick them out...all out of here!!!

Claiming ‘facts’ with 368 passages was also a popular style. Distinct from ‘allegations’ which made sweeping statements by calling on the readers to accept them as already true, the style of facts-claiming showcased ‘evidence’ with an effort to explain a supposedly logical correlation between ‘facts’. This category is often connected to criticism towards politicians’ actions or inactions, or actions supposedly done by immigrants or ‘facts’ about their characteristics based on ethnic, religious, or cultural background. Seen only in 73 passages, explicit conspiracy thinking is not common in our dataset and so is the category of praise and celebration. Expressing admiration and approval, honoring, and cheering a right-wing figure were only found in 26 passages. Further, ad hominem attacks were not present because derision was more commonly directed at immigrants and the political class as a whole and not individuals.

Across dominant styles, a specific variant of anti-immigrant discourse becomes apparent: texts that are carefully crafted, spanning multiple sentences and employing intricate linguistic structures to convey the message. These expressions exhibit syntactic complexity through means such as subordination, sentence variety, and the use of adverbial connectors (see following Example 1, ‘in fact’, ‘however’), as well as various layers of semantic richness achieved through diverse vocabulary and rhetorical sophistication:

Example 1: These people are deliberately let into the country. Politicians tell the population that Germany needs skilled workers. In fact, this is how companies want to get cheap labor. However, only a relatively small percentage comes to work. Many know the German social system and nest themselves in it, without the intention of ever doing regular work.

Example 2: Our German students have to squeeze into crushingly overcrowded school buses up and down the country in Corona times, exposing themselves to an increased risk of infection, thus ultimately endangering all their families, because the cities are too stingy to approve additional buses for the children. Empty buses and bus drivers abound! All this while asylum cheats and arsonists are gondolaed [sarcastically referring to a gondola ride] by government jets across continents for free! For these unwanted guests money is available in abundance!

We define this phenomenon of using long passages and a combination of styles and themes as ‘argumentative racism’. Creating a latent racist discourse, it advances a range of arguments against immigrants, while still emphasizing ‘natural’ and cultural differences and internal homogenization, thus sustaining power differences and exclusionary practices, defined as ‘racism’ by Wodak and Reisigl (2015, p. 578). ‘Argumentative racism’ thus perpetuates covert racist discourse by appealing to reason through purported ‘facts’ and to social legitimacy through linguistic sophistication. Hiding their racist messages in sophisticated and complexly crafted sentences helps to evade social media content moderation filters that are trained to detect obvious forms of racism, while also portraying felt superiority, responsibility and eloquence in sharing the populist anti-immigrant opinion in a veiled manner. From a linguistic perspective, this kind of argumentative racism attuned to platform and legal speech regulations has a specific set of features, which we discuss below.

4.2 Lexical discourse analysis

For our linguistic analysis we build on Swales (1990, p. 26) argument that one of the main linguistic features that characterizes a discourse community is the use of a “specific lexis.” While pragmatic discourse markers and structural features (see Knoblock, 2022) also contribute to the rhetorical genre of a discourse, lexical-semantic features are among the strongest cues for differentiating text types (Kessler et al., 1997, p. 34). Supporting this observation, our analysis reveals that the anti-immigrant corpus in the study characterized by ‘argumentative racism’ is marked by various forms of lexical innovations.

To investigate this relexicalization, we analyzed the frequency distribution and the linguistic characteristics of neologisms, substitute words, word games and alternative spellings in the corpus (see Figure 1). These elements were identified as discourse-specific expressions, as described in the methods section. Figure 5 illustrates the frequencies of the top 15 expressions in the corpus.

4.2.1 Typology of lexical innovations

In the context of the German anti-immigrant discourse as represented in our corpus, lexical innovation is driven by the formation of neologisms using word formation devices. One example is blending, e.g., Flüchtilant, a blend of “refugee” and “asylum seeker,” or Buntist, a blend of “colorful” and “fundamentalist.” Compounding is also evident, for instance Passdeutsche/r, meaning “passport German”; Schlafschaf, “sleep-sheep,” or Linksgrünversifft, combining “left,” “green” and “filthy.” Additionally, substitute expressions with context-specific, alternative meanings are used, such as Goldstücke, literally “pieces of gold,” referring to refugees, which is a typical trait of online hate speech discourse (see Taylor et al., 2017), and Mutti, “mom” as a nickname for former chancellor Angela Merkel.

There are also alternative spellings, including deliberate misspellings, e.g., Nahtsi/Naath-Tziehhs for “Nazi(s)” and innovative abbreviated forms, like Nafri for “North African.” Each individual expression is infrequent in the corpus due to the variability of possible misspellings, which allows them to be used to bypass filtering systems on social media platforms.

The corpus also contains a type of lexical innovation where alternative spellings are combined with the formation of new words in a kind of language game. This involves wordplays like homophonic puns and metaphorical expressions to coin new words or phrases, e.g., Germoney, blend of “Germany” and “money,” used as alternative spelling for “Germany,” alluding to Germany’s generous support for refugees; Affghanistan, blend of “Affe,” “Ape,” and “Afghanistan,” a racist insult, apparent only in written language; Kültür, a blend of “Kultur” (culture) and “Türkei” (Turkey), and Iss-lahm, a wordplay combining “Islam” and “lame.” These expressions are often double entendres, having a hidden, second meaning, i.e., transporting an innuendo, thus being functional similar to substitute expressions used to obscure meaning.

4.2.2 Sources of lexical innovation

Following Grzega’s (2004) typology of factors triggering lexical change, we identify five main sources that drive the lexical innovation found in the German anti-immigrant corpus (see Grzega and Schöner, 2007, p. 36): (i) insult, (ii) wordplay/punning, (iii) disguising language, (iv) linguistic proscriptivism, and (iii) world view change. Aside from insult and wordplay discussed in the previous sections, our analysis revealed that the other three sources are closely linked.

Lexical innovations indicate that speakers attempt to circumvent speech regulation in various ways in an attempt to disguise hate speech as free speech using “‘misnomers’ [i.e.] words that individuals have decided to coin in order to deceive the hearer by disguising unpleasant concepts” (Grzega and Schöner, 2007, p. 27). These bypass strategies include alternative spellings of typical hate speech related keywords, as well as using substitute expressions that take on new meanings within the extreme speech community. An example of this strategy is the substitute expression Goldstücke, “pieces of gold,” which is frequently used (see Figure 1) as an anti-immigrant discourse-specific term for refugees. This term was coined as a sarcastic reference in the context of a speech by a left-leaning politician in 2016, where he expressed that refugees’ contribution to society, specifically their belief in the dream of Europe, holds greater value than gold. In a 2018/19 lawsuit, a Facebook user unsuccessfully sued the platform for blocking his account. He had made a post suggesting a connection between Goldstücke and knife murder, which Facebook deemed as hate speech.6 This case exemplifies the intent of the anti-immigrant discourse community to bypass, and play with, censorshop by using cover terms and substitute expressions.

The need for cover strategies arises mainly from institutional proscriptivism7 enforced by laws such as Germany’s NetzDG, which requires social media platforms to remove hateful content. Thus, in the context of anti-immigrant discourse, the disguising function of lexical innovation does not arise primarily from an in-group motivation to keep one’s speech secretive to outsiders, but rather to circumvent institutional restrictions. Another motivation for the lexical innovation encountered in the corpus is to encode new concepts based on the desired “changes in the categorization of the world” (Grzega and Schöner, 2007, p. 24). One example is the neologism Buntland, “colorful land,” used to describe mainstream German society as too diverse and heterogeneous for the world view of German anti-immigrant discourse. This illustrates that cultural coding, providing novel conceptualizations and metaphors to encode discourse-specific meanings and cultural values that assert the group’s worldview vis-à-vis what is seen as the mainstream discourse, is a major motivation for the lexical innovation in the German anti-immigrant corpus.

4.2.3 Anti-immigrant extreme speech as anti-language

All these factors, meaning proscriptivism, disguising language and world view change, contribute to the emergence of a non-standard language variety that is primarily characterized by relexicalization (Halliday, 1976, p. 571). This discourse community-specific code, or sociolect, can be interpreted as an anti-language – that is “a nonstandard dialect that is consciously used for strategic purposes, defensively to maintain a particular social reality or offensively for resistance and protest [...]” (Halliday, 1976, p. 580). Similar to the instances of anti-language discussed by Halliday, for example, vagabond speech in Elizabethan England or the sociolect used by criminals in modern Calcutta, the German anti-immigrant speech is used for secrecy/disguising as well as “communicative force or verbal art” (Halliday, 1976, p. 572). It is used to express a group-specific world view and a group identity asserting against what is perceived as a hostile “mainstream” discourse. By coining new words, using metaphorical expressions, adapting existing words beyond their conventional meaning, or using orthographic and/or phonetic ambiguity in the online medium to transport an alternative or double meaning, the anti-immigrant discourse community fabricates an in-group-specific speech variety, which not only allows to obfuscate relevant parts of its communication that are not legally allowed and/or socially accepted by society, but also helps to create and maintain a counter-reality by coding discourse-specific concepts and metaphors expressing a world view divergent from ‘official’ public discourse (Halliday, 1976, pp. 572, 576–577). This analysis ties in with the results from the qualitative content coding, where self-victimization shows up as the second most frequent topic, indicating, that the members of this discourse community feel oppressed by the actions and policies implemented by “mainstream” society. While anti-language can create alternative reality (Halliday, 1976, p. 581), the effects of such subcultural practices upon normalizing hateful expressions and reconfiguring officially sanctioned “mainstream” discourse needs continuous investigation.

5 Conclusions and future directions

5.1 Conclusion

In this paper, we have employed thematic and linguistic discourse analysis based on data gathering and reflexive labeling developed in collaboration with factcheckers to delineate the key thematic elements, styles and lexical innovations including linguistic camouflage strategies such as substitute words and wordplay found in anti-immigrant discourses in online user comments in Germany. The variety of tropes mobilized to target immigrants and the prominence of sarcasm and wordplay illustrates what might be called “argumentative racism”– the blending of covert racism with complex argumentation styles, which is simultaneously alert to prevailing state and corporate regulations of speech. Such innovations pose particular challenges to hate speech classifiers and automated detection.

Populist axis of up/down and nationalist axis of in/out (Brubaker, 2017) are both seen in the anti-immigrant discourse, as commentators express anger and frustration toward elites and the political establishment blamed for supporting undeserving immigrants who can never integrate into the cultural fabric of Germany. Hyper-nationalist narratives are marshalled in equal measure to raise alarm over cultural threat to the nation and nostalgia for the former times when the country in which they played a central role was not yet so “bunt” [colored]. The ethnographically developed annotation scheme presented in this article contributes towards capturing these varieties and a granular understanding of anti-immigrant discourses. Although Turkish guestworkers and their German descendants have been subjects of heated discussions in Germany for more than 50 years (Wilhelm, 2013), anti-immigrant discourses on social media channels are today primarily aimed against new groups of immigrants who have entered the country since 2021, especially asylum seekers, and immigrants coming from North African and majority Muslim countries.

5.2 Limitations and potential directions for future research

This article draws upon online posts sourced from various social media and online venues through collaborative efforts. We opted not to have factcheckers trace the posts to specific social media platforms, because of our focus on analyzing the discourses rather than platform distribution. We thus placed the emphasis on understanding the discourse that permeates various platforms pertinent to the daily operations of local factcheckers. However, while we did not track platforms, future research could explore whether certain discourse specific elements were more prominent on one platform compared to another, as well as possible correlations between platforms and themes or styles of anti-immigrant discourse.

Future research should further combine this analysis with ethnographic fieldwork to delineate the motivations of actors and various networks they are embedded within that shape anti-immigrant discourses discussed here. In addition, analysis of text based passages should be extended to videos, memes or emoticons that propel ‘argumentative racism’. The methodology of collaborating with community partners to gather and label data should be explored further to develop annotation schemes that can remain alert to linguistic innovations and shifting tropes within dynamic extreme speech ecosystems.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethics approval was obtained for the study involving human data in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Informed consent forms were received from all participating factcheckers. The social media data was accessed and analyzed in accordance with the platforms’ terms of use and all relevant institutional/national regulations.

Author contributions

LN: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. SU: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. AW: Writing - review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement number 957442) as well as from and the Bavarian Research Institute for Digital Transformation (bidt).

Acknowledgments

We thank Miriam Homer for her excellent research assistance, and all the fact-checkers and partner organizations who have generously given their time and expertise for the project. We especially thank Anna-Sophie Barbutev, Eva Casper, Aylin Dogan, Julia Ley, and Marita Wehlus for collaborating with us on the project.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The passage is translated from German into English by the authors. Subsequent passages cited in the article are also translated, except illustrative examples for discourse specific vocabularies.

2. ^For details on the NetzDG, see https://www.bmj.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Gesetzgebung/RefE/NetzDG_engl.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=4.

3. ^Cohen’s kappa ranges from −1 to 1 (1 indicates perfect agreement, 0 indicates agreement no better than chance, and values less than 0 indicate disagreement worse than chance). In general, a kappa value between 0.81 and 1.00 is considered almost perfect agreement, 0.61 to 0.80 substantial agreement, 0.41 to 0.60 moderate agreement, 0.21 to 0.40 fair agreement, 0.00 to 0.20 slight agreement, and less than 0.00 poor agreement.

4. ^Under derogatory speech, anti-immigrant speech also had “politicians,” “the state” and “civil society advocates for inclusive societies” and “legacy media” as other target groups.

5. ^In the following sections “sentiment” refers to (collective) feelings or attitudes of individuals or groups as represented through language and discourse, and reflecting in our case nationalist, right-wing, populist and anti-immigrant themes.

6. ^For details on the lawsuit see https://www.rnd.de/politik/landgericht-bremen-begriff-goldstueck-kann-hetze-sein-E5SLROYFL4MJR6IUHLG4NBRTQI.html.

7. ^See Grzega and Schöner (2007, p. 36) “Institutional and non-institutional linguistic pre- and proscriptivism (i.e., legal and peer-group linguistic pre- and proscriptivism, aiming at “demarcation”).”

References

Arlt, D., Schumann, C., and Wolling, J. (2020). Upset with the refugee policy: exploring the relations between policy malaise, media use, trust in news media, and issue fatigue. Communications 45, 624–647. doi: 10.1515/commun-2019-0110

Aslanidis, P. (2018). Measuring populist discourse with semantic text analysis: an application on grassroots populist mobilization. Qual. Quant. 52, 1241–1263. doi: 10.1007/s11135-017-0517-4

Awan, I. (2014). Islamophobia and twitter: a typology of online hate against Muslims on social media: islamophobia and twitter. Policy Internet 6, 133–150. doi: 10.1002/1944-2866.POI364

Batorski, D., and Grzywińska, I. (2018). Three dimensions of the public sphere on Facebook. Inf. Commun. Soc. 21, 356–374. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2017.1281329

Baumgarten, N., Bick, E., Geyer, K., Iversen, D. A., Kleene, A., Lindø, A. V., et al. (2019). ‘Towards balance and boundaries in public discourse: expressing and perceiving online hate speech (XPEROHS)’, RASK: international journal of. Lang. Commun. 50, 87–108. Available at: https://www.sdu.dk/-/media/files/om_sdu/institutter/isk/forskningspublikationer/rask/rask+50/baumgarten+et+al.pdf

Benesch, S. (2012). Dangerous speech: A proposal to prevent group violence. New York: World Policy Institute.

Bleich, E. (2014). Freedom of expression versus racist hate speech: explaining differences between high court regulations in the USA and Europe. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 40, 283–300. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2013.851476

Canovan, M. (1999). Trust the people! Populism and the two faces of democracy. Political Studies 47, 2–16. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.00184

Cicchetti, D. V. (1994). Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychol. Assess. 6, 284–290. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.6.4.284

De Smedt, T., and Jaki, S. (2018). “(2018) ‘the Polly Corpus: online political debate in Germany’” in 6th conference on computer-mediated communication (CMC) and social media corpora (CMC-corpora 2018). eds. R. Vandekerckhove, D. Fišer, and L. Hilte (University of Antwerp: Antwerp), 33–36.

Dostal, J. M. (2015). The Pegida movement and German political culture: is right-wing populism Here to stay? Polit. Q. 86, 523–531. doi: 10.1111/1467-923X.12204

Garnett, S. (2018). Agonies of pluralism: Germany and the new right. Soundings 69, 62–79. doi: 10.3898/SOUN:69.04.2018

Griebel, T., and Vollmann, E. (2019). We can(‘t) do this: a corpus-assisted critical discourse analysis of migration in Germany. J. Lang. Polit. 18, 671–697. doi: 10.1075/jlp.19006.gri

Gründl, J. (2022). Populist ideas on social media: a dictionary-based measurement of populist communication. New Media Soc. 24, 1481–1499. doi: 10.1177/1461444820976970

Grzega, J. (2004). Bezeichnungswandel: Wie, Warum, Wozu? Ein Beitrag zur englischen und allgemeinen Onomasiologie. Heidelberg: Winter.

Grzega, J., and Schöner, M. (2007). English and general historical lexicology: Materials for onomasiology seminars. Eichstätt-Ingolstadt: Katholische Universität.

Halliday, M. A. K. (1976). Anti-Languages. Am. Anthropol. 78, 570–584. doi: 10.1525/aa.1976.78.3.02a00050

Hameleers, M. (2021). They are selling themselves out to the enemy! The content and effects of populist conspiracy theories. Int. J. Public Opinion Res. 33, 38–56. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/edaa004

Hanzelka, J., and Schmidt, I. (2017). Dynamics of cyber hate in social media: a comparative analysis of anti-Muslim movements in the Czech Republic and Germany. Int. J. Cyber Criminol. 11, 143–160. doi: 10.5281/ZENODO.495778

Heim, T. (2017). “Pegida als leerer Signifikant, Spiegel und Projektionsfläche - eine Einleitung” in Pegida als Spiegel und Projektionsfläche: Wechselwirkungen und Abgrenzungen zwischen Pegida, Politik, Medien, Zivilgesellschaft und Sozialwissenschaften (Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden).

Heiss, R., and Matthes, J. (2020). Stuck in a nativist spiral: content, selection, and effects of right-wing populists. Polit. Commun. 37, 303–328. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2019.1661890

Inglehart, R., and Norris, P. (2017). Trump and the populist authoritarian parties: the silent revolution in reverse. Perspect. Polit. 15, 443–454. doi: 10.1017/S1537592717000111

Ivarsflaten, E. (2008). What unites right-wing populists in Western Europe?: re-examining grievance mobilization models in seven successful cases. Comp. Pol. Stud. 41, 3–23. doi: 10.1177/0010414006294168

Jacobs, K., and Spierings, N. (2019). A populist paradise? Examining populists. Inform. Commun. Soc. 22, 1681–1696. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2018.1449883

Jagers, J., and Walgrave, S. (2007). Populism as political communication style: an empirical study of political parties’ discourse in Belgium. Eur J Polit Res 46, 319–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00690.x

Kaiser, J. (2021). “Localized hatred: the importance of physical spaces within the German far-right online Counterpublic on Facebook” in Digital hate - the global conjuncture of extreme speech. eds. S. Udupa, I. Gagliardone, and P. Hervik (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press), 211–226.

Kazin, M. (1998). The populist persuasion: an American history. 1st Edn. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Kessler, B., Nunberg, G., and Hinrich, S. (1997). “Automatic detection of text genre” in 35th annual meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and 8th conference of the European chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Association for Computational Linguistics: Madrid, Spain), 2–38.

Klein, M., and Falter, J. W. (1996). “Die dritte Welle rechtsextremer Wahlerfolge in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland” in Rechtsextremismus: Ergebnisse und Perspektiven der Forschung. eds. J. W. Falter, H.-G. Jaschke, and J. R. Winkler (Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften), 288–312. doi: 10.1007/978-3-322-97077-0_17

Knoblock, N. (2022). The grammar of hate: Morphosyntactic features of hateful, aggressive, and dehumanizing discourse. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Krämer, B. (2014). Media populism: a conceptual clarification and some theses on its effects: media populism. Commun. Theory 24, 42–60. doi: 10.1111/comt.12029

Kriesi, H. (2014). The populist challenge. West Eur. Polit. 37, 361–378. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2014.887879

Lentin, A. (2016). Racism in public or public racism: doing anti-racism in “post-racial” times. Ethn. Racial Stud. 39, 33–48. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2016.1096409

Lichtenstein, D. (2021). “No government mouthpieces: changes in the framing of the migration crisis” in German news and infotainment media, studies in communication sciences. 21, 267–284. doi: 10.24434/j.scoms.2021.02.005

Maronikolakis, A., Wisiorek, A., Nann, L., Jabbar, H., Udupa, S., and Schütze, H. (2022) Listening to affected communities to define extreme speech: dataset and experiments. Available at: http://arxiv.org/abs/2203.11764 (Accessed June 24, 2022).

McHugh, M. L. (2012). Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem. Med., 22, 276–282. doi: 10.11613/BM.2012.031

Mudde, C. (2010). The populist radical right: a pathological normalcy. West Eur. Polit. 33, 1167–1186. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2010.508901

Paasch-Colberg, S., Strippel, C., Trebbe, J., and Emmer, M. (2021). From insult to hate speech: mapping offensive language in German user comments on immigration. Media Commun. 9, 171–180. doi: 10.17645/mac.v9i1.3399

Puschmann, C., Karakurt, H., and Nachtwey, O. (2022). RPC-Lex: a dictionary to measure German right-wing populist conspiracy discourse online. Convergence 28, 1144–1171. doi: 10.1177/13548565221109440

Rensmann, L. (2006). “Populismus. Gefahr für die Demokratie oder nützliches Korrektiv?” in Populismus und ideologie. ed. F. Decker (Wiesbaden, Germany: VS), 59–80.

Schaub, M., and Morisi, D. (2020). Voter mobilisation in the echo chamber: broadband internet and the rise of populism in Europe. Eur J Polit Res 59, 752–773. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12373

Schmuck, D., and Hameleers, M. (2020). Closer to the people: a comparative content analysis of populist communication on social networking sites in pre- and post-election periods. Inf. Commun. Soc. 23, 1531–1548. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2019.1588909

Serrano, J.C.M., Shahrezaye, M., Papakyriakopoulos, O., and Hegelich, S. (2019) The rise of Germany’s AfD: a social media analysis, In Proceedings of the 10th international conference on social media and society. SMSociety’19: International Conference on Social Media and Society, Toronto ON Canada: ACM, 214–223

Siapera, E. (2019). Organised and ambient digital racism: multidirectional flows in the Irish digital sphere. Open Library Human. 5:13. doi: 10.16995/olh.405

Stier, S., Posch, L., and Strohmaier, M. (2017). When populists become popular: comparing Facebook use by the right-wing movement Pegida and German political parties. Inf. Commun. Soc. 20, 1365–1388. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2017.1328519

Swales, J. M. (1990). Genre analysis: English in academic and research settings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Taylor, J., Peignon, M., and Chen, Y.-S. (2017). Surfacing contextual hate speech words within social media. arXiv. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1711.10093

Thränhardt, D. (2002). Include or exclude: discourses on immigration in Germany. J. Int. Migration Integrat. 3, 345–362. doi: 10.1007/s12134-002-1019-2

Törnberg, A., and Wahlström, M. (2018). Unveiling the radical right online: exploring framing and identity in an online anti-immigrant discussion group. Sociol. Forskning 55, 267–292. doi: 10.37062/sf.55.18193

Udupa, S. (2019). Nationalism in the digital age: fun as a Metapractice of extreme speech. Int. J. Commun. 13, 3143–3163. doi: 10.5282/ubm/epub.69633

Udupa, S., Maronikolakis, A., and Wisiorek, A. (2023). Ethical scaling for content moderation: extreme speech and the (in)significance of artificial intelligence. Big Data Soc. 10:205395172311724. doi: 10.1177/20539517231172424

van Dijk, T. A. (1998). Semantics of a press panic: the Tamil invasion. Eur. J. Commun. 3, 167–187. doi: 10.1177/0267323188003002004

Vollmer, B., and Karakayali, S. (2017). The volatility of the discourse on refugees in Germany. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 16, 118–139. doi: 10.1080/15562948.2017.1288284

Wilhelm, C. (2013). Diversity in Germany: a historical perspective. German Polit. Soc. 31, 13–29. doi: 10.3167/gps.2013.310203

Keywords: anti-immigrant discourse, extreme speech, online populism, ethnography, content analysis, corpus-based discourse analysis, non-standard language variety

Citation: Nann L, Udupa S and Wisiorek A (2024) Online anti-immigrant discourse in Germany: ethnographically backed analysis of user comments. Front. Commun. 9:1355025. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1355025

Edited by:

Ufuoma Akpojivi, University of the Witwatersrand, South AfricaReviewed by:

Afrooz Rafiee, Radboud University, NetherlandsFriederike Windel, The City University of New York, United States

Copyright © 2024 Nann, Udupa and Wisiorek. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Leah Nann, bGVhaC5uYW5uQGxtdS5kZQ==

†ORCID: Leah Nann https://orcid.org/0009-0002-6506-6230

Sahana Udupa https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3647-9570

Axel Wisiorek https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6058-0460

Leah Nann

Leah Nann Sahana Udupa1†

Sahana Udupa1†