- Digital Public Relations Study Program, Communication and Social Science Faculty, Telkom University, Bandung, Indonesia

This study investigates the proliferation of herbal medicine advertising on local radio stations in West Java, Indonesia, with attention to regulatory gaps, media ethics, and public health risks. Using a qualitative case study approach, data were collected between late 2023 and 2024 through interviews, observation, and document analysis. Informants included radio personnel, officials from the West Java Regional Food and Drug Supervisory Agency (BBPOM), and relevant industry stakeholders. Data were gathered between late 2023 and 2024, a period that witnessed significant shifts in media financing and advertising practices. Findings show that economic pressures during and after the COVID-19 pandemic led stations to rely heavily on herbal advertisers—some of whom acquired influence over content or ownership. This dependency compromised editorial autonomy and blurred regulatory compliance, with many ads promoting unverified health claims, testimonials, and products beyond approved uses. The study highlights fragmented enforcement among BBPOM, the National Agency of Drug and Food Control (BPOM), the Regional Broadcasting Commission (KPID), and the Ministry of Communication and Informatics (Kominfo), enabling misleading content to persist. Interpreted through the lens of political economy and neoliberal governance, the findings reveal how market survivalism and cultural trust in “natural” remedies reshape media practices. This research contributes to understanding how commercial pressures and institutional disconnection endanger ethical health communication in Indonesia’s evolving broadcast landscape.

Introduction

Despite the increasing disruption of conventional mass media by digital platforms, radio continues to hold cultural and communicative significance in Indonesia. It remains a vital source of information and a preferred advertising platform, especially in semi-urban and rural areas, due to its affordability familiarity, and reach (Utami and Herdiana, 2021). Unlike visual media, radio’s strength lies in its immersive use of sound and language, which enhances audience engagement and allows for targeted persuasive communication (Devi, 2020).

One sector that has strategically leveraged radio’s influence is the herbal medicine industry, which saw an advertising surge particularly during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Globally, herbal medicine use continues to grow, with the World Health Organization estimating that up to 80% of the population in developing countries and a significant proportion in developed countries rely on traditional herbal remedies as part of their primary healthcare. The global market for herbal medicine was valued at over USD 170 billion in 2022, and is projected to reach USD 600 billion by 2033 (Anbarasan et al., 2023; World Health Organization, 2019). Other data suggest that 70–95% of the global population has used some form of traditional, complementary, or alternative medicine at least once in their lives (Mukherje, 2019). In Indonesia, the widespread acceptance of herbal products is driven by the perception that remedies made from natural substances are safer and less harmful than synthetic pharmaceuticals (Kurniasari et al., 2023).

The integration of herbal advertising into radio programming in Indonesia, particularly in West Java, the country’s most populous province, has escalated beyond conventional commercial arrangements. By 2023, research observations showed that some herbal product entrepreneurs had shifted from being advertisers to becoming owners or major stakeholders in radio stations, thereby influencing not only content but institutional direction.

This phenomenon, while economically adaptive, raises critical concerns about the credibility of health communication, regulatory oversight, and ethical broadcasting standards. Law no. 32/2002 on Broadcasting mandates fair and accurate advertising, and KPI (Komisi Penyiaran Indonesia/Indonesian Broadcasting Commission) enforces program ethics and Broadcast Program Standards (SPS/Standar Program Siaran). However, rising advertisement volumes and minimal content filtering suggest systemic enforcement weaknesses (Pemerintah Indonesia, 2002).

This study is guided by the interpretive hypothesis that the rise in herbal medicine advertising on Indonesian radio (particularly during and after the COVID-19 pandemic) has reshaped not only the volume and nature of advertising but also the ownership dynamics and editorial autonomy within local broadcasting ecosystems. These shifts are interpreted as the result of intersecting factors: the decline in conventional advertising revenue, strategic financial positioning by herbal entrepreneurs, inconsistent regulatory enforcement, and opportunistic practices among both advertisers and media operators. Rather than serving as a testable proposition, this hypothesis provides a conceptual lens to explore the broader implications for public health communication, media ethics, and the regulatory landscape in Indonesia’s commercial radio sector.

Literature review

In health communication studies, herbal medicine advertisements are commonly categorized into three main formats: (1) commercial advertising, which aims to promote products through persuasive language and brand imagery; (2) testimonial-based advertising, which employs personal anecdotes or user experiences to build trust and influence decision-making; and (3) informational or public service advertising, which presents educational content often blended with subtle promotional undertones (Kristiana et al., 2013; Pambudi and Kholidah, 2020).

This typology illustrates both the strategic diversity and the potential risk of health misinformation, particularly when scientific substantiation is lacking.

This concern is reflected internationally. In Sri Lanka, Rufaideen et al. (2022) found that only 8.1% of radio-broadcasted herbal ads included distribution permits, and just over half included manufacturer details—raising serious issues of transparency and consumer traceability. Similar problems have emerged in Nigeria, where media collusion with herbal companies has allowed unchecked dissemination of therapeutic claims without regulatory vetting (Ahaiwe, 2019).

In Indonesia, these issues are compounded by limited oversight from regulatory bodies, particularly the disconnect between KPI (Komisi Penyiaran Indonesia/Indonesia’s Broadcasting Commission) and BBPOM/BPOM (provincial and national food and drug agencies). Testimonial-based herbal ads frequently violate Law no. 32/2002 on Broadcasting, which prohibits misleading health content, yet they continue to be aired due to enforcement gaps (Pemerintah Indonesia, 2002; Republik Indonesia, 1999).

The cultural affinity for traditional herbal remedies deepens this vulnerability. Sangkaen and Sumarauw (2022) argue that lifestyle shifts—including declining physical health and over-reliance on processed food—have created renewed interest in “natural” alternatives. Marketing efforts that focus on brand credibility, perceived safety, and affordability further reinforce the appeal of herbal products (Kurniasari et al., 2023). In Ghana, similar findings were reported by Opoku (2021), who noted that expert endorsements and exaggerated efficacy claims were highly influential in shaping public attitudes toward herbal therapies.

Importantly, such trends are echoed in Ethiopia, where studies led by Yeshak et al. revealed that the concomitant use of herbal and conventional medicine is widespread among patients with chronic conditions like diabetes and hypertension. In these cases, lack of disclosure to physicians, unregulated dosage, and limited patient education were identified as critical health risks (Meshesha et al., 2020; Gebregeorgise et al., 2019; Tilahun et al., 2018). These findings directly parallel the situation in Indonesia, where mass media serves as the primary interface between herbal producers and consumers, often without the involvement of licensed healthcare professionals.

Moreover, Dr. Yeshak’s pharmacological research, such as her analysis of the toxicity and bioactivity of medicinal plant extracts (Hika et al., 2020), demonstrates that many traditionally used herbs exhibit potent physiological effects. Yet, without proper regulatory channels, these effects remain poorly communicated in advertising content, placing consumers at risk of misuse. As Yeshak et al. emphasize across multiple publications (2018–2020), the absence of clinical trials, poor consumer education, and inconsistent labeling in herbal products compromise both patient safety and therapeutic accountability. These issues are amplified when herbal narratives are commercially repackaged and broadcasted via mass media, as is increasingly the case in Indonesian radio.

Thus, the Indonesian context reflects a global pattern where traditional medicine is commodified without regulatory safeguards, often supported by fragmented media oversight and low public health literacy. The strategic alignment of herbal medicine entrepreneurs with financially vulnerable radio stations creates a media ecosystem that rewards repetition over verification, and persuasion over pharmacological evidence.

Theoretical framework

This study adopts a critical interpretive framework that combines the political economy of media, neoliberal governance theory, and cultural sociology to examine the proliferation of herbal medicine advertising on Indonesian radio. These perspectives frame the issue as a complex intersection of market forces, regulatory retreat, and cultural legitimation, rather than a simple shift in media content.

Capitalism and the political economy of media

From a political economy standpoint, Indonesian radio stations function within a market-driven cultural industry where content is shaped by the need for revenue, not public service (Mosco, 2009). During the COVID-19 pandemic, many local stations, especially in semi-urban areas, faced sharp declines in conventional advertising. In response, they turned to herbal medicine entrepreneurs as alternative financial backers. These transactions reflect capitalism’s amoral logic of surplus extraction, where platforms and audience trust become commodified and health discourse is adapted to advertising needs—regardless of accuracy or risk.

Neoliberalism and deregulated media environments

Overlaying the economic analysis is a neoliberal framework in which the state withdraws from protective regulation in favor of “market-led” governance (Harvey, 2005). In the Indonesian context, this is evident in the lack of coordination between KPI, the broadcasting regulator, and BPOM/BBPOM, the health product authorities. Testimonial-style ads, often lacking scientific substantiation, are broadcast widely, promoting self-treatment as a form of consumer empowerment. This aligns with Rose’s (2007) concept of the “responsibilized self,” in which individuals are expected to manage their own health risks in a deregulated environment.

Cultural imaginaries and the return to the organic

The popularity of herbal medicine in Indonesia is not solely economic but rooted in cultural imaginaries that position natural remedies as safe, authentic, and traditional. Recent studies emphasize that during public health crises, traditional medicine becomes a symbolic refuge, offering culturally resonant narratives of healing that are seen as trustworthy and accessible. These narratives, however, can be commercialized through media, leading to their decontextualization and exploitation for profit. This process often strips traditional practices of their cultural safeguards and embeds them within marketing logics that normalize misinformation and hinder regulatory control (Dew and Liyanagunawardena, 2023).

In summary, this framework conceptualizes herbal advertising on radio as a socio-political phenomenon shaped by economic dependency, neoliberal policy gaps, and cultural perceptions of healing. It helps explain why such content proliferates and why regulation remains weak, despite clear legal frameworks.

Methodology and data

To answer the research question, this study employed a qualitative case study approach situated within the constructivist paradigm. This epistemological framework assumes that reality is constructed through social interactions and that knowledge emerges from context-dependent interpretations of experience (Creswell and Poth, 2018). As the central concern of this study involves how herbal medicine advertising has shaped radio content, ownership, and regulatory dynamics in West Java, the constructivist paradigm is well-suited to explore the meanings assigned by media actors, regulators, and industry stakeholders to these transformations.

The case study design was selected for its suitability in investigating complex phenomena in bounded systems and real-world contexts (Yin, 2018). Herbal medicine advertising on Indonesian radio is shaped by a convergence of media economics, health regulation, and cultural practices. These interactions are best understood holistically, within their specific institutional and regional environments.

To ensure purposive depth, the study employed purposive sampling (Palinkas et al., 2015), selecting individuals with direct knowledge of radio operations and policy oversight. The sample included:

• Eight radio station managers and four support staff, representing three regional broadcasting zones in West Java:

o Central/North: Bandung City

o North: Indramayu Regency

o South: Ciamis and Pangandaran Regencies

These participants held strategic roles such as content directors, operational supervisors, and advertising coordinators, with 5–20 years of experience.

• Two expert informants from PRRSNI (Persatuan Radio-Radio Siaran Nasional Indonesia) West Java, the regional chapter of the Indonesian National Private Radio Association, with over a decade of experience in media governance and broadcasting policy.

• Two regulatory officials from BBPOM Bandung (Balai Besar Pengawas Obat dan Makanan/Regional Office of the Indonesian Food and Drug Supervisory Agency), who oversee compliance with advertising laws pertaining to food and traditional medicine in West Java.

Data collection occurred between late 2023 and late 2024, combining semi-structured, in-depth interviews with non-participant observation. Interviews were conducted in person, audio-recorded, and transcribed for analysis. Observational field notes were documented at station offices and regulatory institutions. The guiding themes were:

(a) the intensity and frequency of herbal medicine advertisements on radio,

(b) the economic role of herbal advertising in post-pandemic broadcasting survival,

(c) the regulatory challenges involved in supervising health-related advertising content,

(d) shifts in media ownership attributed to herbal advertising partnerships.

Operationalization of advertising intensity

To ensure analytic clarity, advertising intensity is defined as a multi-dimensional indicator comprising:

• The frequency of herbal advertisements per day or week aired on a station.

• The share of total commercial airtime occupied by herbal products.

• The number of distinct herbal medicine clients and total product brands advertised.

• The percentage of total radio revenue attributed to herbal advertising, where disclosed.

• Changes in these metrics across the pre-pandemic (2018–2019) and pandemic (2020–2022) periods.

Though direct financial disclosures were limited due to proprietary constraints, triangulation with multiple informants, internal station documents (when accessible), and direct observation of programming schedules allowed for approximated comparative assessment. For instance, several managers reported that by 2021, herbal advertisements constituted 60–80% of total commercial airtime, up from less than 30% in 2019. Furthermore, respondents confirmed that three station takeovers occurred during this period, facilitated by sustained advertising relationships that evolved into ownership transitions. This claim is corroborated by contract and partnership documents observed during site visits and triangulated across management, PRRSNI, and BBPOM informants.

Regulatory gaps

Despite oversight by KPID, BBPOM, BPOM, and Kominfo, enforcement remains fragmented. BBPOM lacks sanctioning authority and must escalate violations to BPOM, causing delays. KPID’s limited power often results in only temporary warnings. As one BBPOM official noted, sanctions require lengthy processes while problematic ads remain on air. The absence of unified regulation and high dependency on herbal revenue mean stations often choose financial survival over compliance.

Data analysis and validation

Data were analyzed thematically and categorized under four themes: economic survival, regulatory gaps, advertiser influence, and public health concerns. Non-essential data were excluded through reduction. Source triangulation across radio managers, regulators, and associations ensured credibility. Final interpretations reflect collaborative synthesis across research team members.

Results and discussion

Herbal medicine advertising intensity: expansion, dynamics, and theoretical implications

Based on the results of this study, advertising intensity refers to the frequency, duration, and breadth of herbal medicine advertisement presence on radio, including the number of advertiser clients, the proportion of airtime allocated, and its impact on radio revenue streams. In the West Java case study, intensity also includes how herbal advertisers increasingly embedded themselves in the operational and ownership structure of local stations, a phenomenon amplified during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Radio management in the observed regions showed a high degree of openness to all forms of collaboration offered by herbal medicine entrepreneurs. These advertisers were often considered “life-saving partners” by station managers, particularly during the acute economic downturn.

This situation occurred because it was triggered by business and operational pressures, where advertising as the main contributor to revenue had experienced symptoms of decline for 1–2 years (in 2018 and 2019) before the Corona Pandemic (2020–2022) and occurred evenly in West Java. The peak during the pandemic was that advertising revenue plummeted by 70%, and that was with ads left only from old clients who were loyal and trusted each other. Older clients also only have less than half of their usual budget. Many advertisers are shifting their advertising budgets from conventional media to new internet-based media, for example, the IG (Instagram) account contains information about a city that is a new favorite place for advertisers.

At the same time, government advertising, which is usually a source of mainstream advertising because it is consistent in advertising, also reduces the budget as a result of the government’s PAD (Pendapatan Asli Daerah/Regional Original Revenue) decline and the remaining budget is also diverted to the city’s information IG. Therefore, the severe situation due to the impact of fierce competition is no longer radio with others, or radio with television, but the phenomenon of radio competition with IG-based social media accounts has emerged. A station manager from Indramayu stated:

“By 2020, we had lost all event-based revenue, and our only reliable clients were from herbal medicine. They offered consistency when no one else would.”

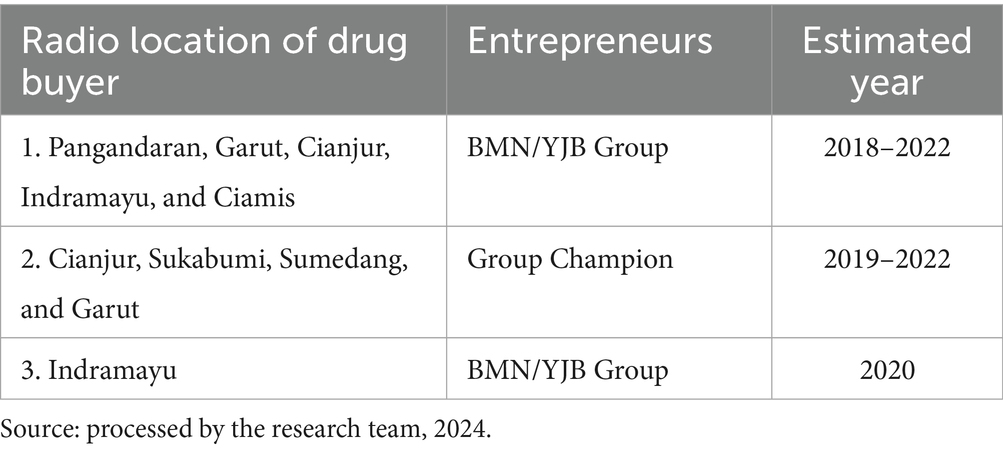

In addition to declining advertising, the Corona Pandemic has also made the contributor to the revenue of the two radios, namely event management from off air activities, even non-existent at all in line with the PSBB (Large-Scale Social Restrictions) policy from the government. A situation that does not allow radio crews to create crowded events, ranging from music concerts to sponsored cooking demonstrations, so the selection of herbal medicine advertisements is a realistic choice. Because of this high intensity, a number of radios in West Java were even finally bought by herbal medicine entrepreneurs (see Table 1), so that the change of ownership made herbal advertising content more often played on the radio.

In addition to taking over radio, for radios that have not been bought, they also tend to take makeshift advertising content from herbal medicine entrepreneurs even though it is not necessarily in accordance with the SPS (Broadcast Program Standard) rules from KPID as a derivative of Law No. 32/2022 concerning Broadcasting.

Especially if the herbal practitioner has been advertising for a long time (loyal), then the radio manager fully believes the advertising content without worrying about the risk of using drugs to his listeners in the future. Whether it is advertising content in the form of regular spots or advertorial lips read by broadcasters. As one manager in Sukabumi remarked:

“If the product has been aired for a year without complaints, why should we question the content now? We trust the client.”

This comment reflects the institutional normalization of unvetted content, especially among small to mid-sized stations. Only large, well-capitalized broadcasters were able to maintain editorial screening mechanisms, while others traded compliance for survival.

Findings from this study indicate that radio managers largely accommodated the demands of herbal medicine entrepreneurs, viewing them as critical sources of financial stability during a period of intense commercial uncertainty. This trend became especially pronounced in the years immediately preceding and during the COVID-19 pandemic, when traditional advertising revenue and off-air activities declined sharply.

Such managerial decisions reflect not only economic necessity but also broader structural forces that shape the operational logic of media institutions. As Morrisan (2016) explains, radio station managers are responsible for planning, organizing, directing, and supervising business functions, including meeting revenue targets and managing expenditures. These roles become even more pronounced under crisis conditions, where economic pressures intensify and institutional survival becomes paramount. In the case of West Java, many radio managers embraced advertising partnerships with herbal medicine entrepreneurs not out of ideological alignment, but as a pragmatic response to declining conventional revenue streams and disappearing event-based income during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This dynamic is emblematic of the broader political economy of media, where content and ownership are shaped by the pursuit of financial viability over public service ideals. As Mosco (2009) argues, “political economy is the study of the social relations, particularly the power relations, that mutually constitute the production, distribution, and consumption of resources, including communication resources.” He further emphasizes that under capitalist logic, media industries “treat audiences as commodities to be sold to advertisers,” reshaping content to align with market demands rather than public interest. In this context, advertising is not merely a source of income—it dictates editorial decisions and reconfigures content to meet commercial imperatives.

Devi (2020) and McQuail, as cited in Nasution (2018), similarly note that advertising functions as a central pillar in sustaining industrial media, particularly under conditions of heightened competition and operational uncertainty. Morissan (Nasution, 2018) adds that success in broadcasting is as much a function of marketing creativity as it is of programmatic or technical innovation.

Indeed, the findings of this study confirm that the sale of broadcasting licenses to herbal entrepreneurs such as the Jawara Group and BMN/YJB Group is not an isolated act of institutional weakness, but a rational adaptation within a media system increasingly defined by economic determinism. As Heryanto (2017) observes, the ideological stance and communicative outputs of media are often subordinate to the structural imperatives of funding models and cultural industry logics. Editorial independence is compromised when revenue streams are consolidated in the hands of a few dominant clients—in this case, advertisers offering products with unverified health claims.

Herbal medicine entrepreneurs, for their part, have become increasingly literate in media strategy. As Saputra et al. (2023) highlight, radio retains significant persuasive power due to its deep audience engagement, emotional intimacy, and wide reach across both urban and rural populations. These attributes make radio an ideal vehicle for health product promotion. As Baskoro and Sucahya (2023) emphasize, herbal advertisers are fully aware that long-term survival for many radio stations depends on securing stable commercial partnerships. By aligning their business strategies with the financial needs of these broadcasters, herbal companies have secured not only airtime but, in some cases, direct editorial influence.

The resulting content, however, frequently violates existing regulatory frameworks. Many herbal advertisements aired on radio stations lacked required registration numbers, included exaggerated healing claims, or featured unverifiable testimonial content—clear breaches of the Broadcast Program Standards (SPS) and Law No. 32/2002 on Broadcasting (Pemerintah Indonesia, 2002). These violations persist in part because the enforcement ecosystem is fragmented. As a BBPOM official in West Java explained, their agency can only report infractions to the central BPOM in Jakarta, which slows the sanctioning process and allows problematic advertisements to continue airing unchecked (BPOM, 2021).

This regulatory gap is symptomatic of broader neoliberal governance dynamics. Following Harvey (2005), neoliberalism entails a state withdrawal from its traditional role as a regulator, transferring responsibility to market actors and individual consumers. In the Indonesian case, this manifests as a disconnect between media regulators (KPI) and health authorities (BPOM/BBPOM), where enforcement authority is diffuse and rarely results in meaningful consequences. Rose (2007) refers to this phenomenon as the “responsibilized self,” wherein citizens are expected to make informed health choices based on commercial messages, even when those messages are misleading or unregulated.

This deregulation is compounded by deep-rooted cultural imaginaries that associate herbal medicine with safety, authenticity, and tradition. As Dew and Liyanagunawardena (2023) explains, the cultural authority of traditional medicine stems from its deep embedding in community knowledge systems, where it serves not merely as a substitute for biomedical treatment but as a culturally grounded response to illness. In moments of health crisis or institutional distrust, traditional remedies offer a symbolic and spiritual alternative that resonates with local identities and self-care practices. This restorative function of traditional medicine allows it to “reclaim therapeutic meaning” in ways that biomedicine often fails to provide, particularly when health systems are perceived as inaccessible or impersonal. In the Indonesian context, as affirmed by Sangkaen and Sumarauw (2022) and Kurniasari et al. (2023), herbal remedies are widely regarded as gentler and safer than synthetic pharmaceuticals, reinforcing a culturally resonant sense of wellness. This cultural capital empowers herbal product companies to market their goods as natural and harmless —even when such claims lack scientific validation or regulatory approval.

Similar dynamics have been documented globally. In Sri Lanka, Rufaideen et al. (2022) found that only 8.1% of herbal advertisements included legally required distribution numbers, and less than 54% listed manufacturer contact details. In Nigeria, Ahaiwe (2019) observed frequent collusion between broadcasters and herbal sellers, enabling unverified health claims to enter public discourse without oversight. Opoku (2021), examining herbal advertising in Ghana, concluded that testimonial narratives and expert endorsements were central to public trust—even when those claims were unverifiable. In Indonesia, studies by Kristiana et al. (2013), as well as Pambudi and Kholidah (2020), document the use of exaggerated language, overclaims, and promises of exclusive, side-effect-free cures—often backed by emotionally persuasive testimonies.

Taken together, these findings confirm that the surge in herbal medicine advertising on Indonesian radio represents more than a temporary adaptation to economic disruption. It signals a deeper structural transformation characterized by:

• Economic dependency of broadcasters on niche advertisers;

• Regulatory incapacity due to institutional fragmentation;

• Cultural legitimization of traditional remedies as safe and desirable alternatives.

By interpreting these findings through the combined lenses of political economy, neoliberal governance, and cultural sociology, this study offers a comprehensive framework for understanding why unverified herbal advertising continues to proliferate, despite clear legal and ethical concerns. The phenomenon is not merely a failure of enforcement, but a consequence of systemic pressures and cultural logics that have reshaped both media and health communication in post-pandemic Indonesia.

Implications of intensity herbal medicine advertising: a political-economic and cultural analysis

The findings from this study revealed a notable gap in regulatory compliance practices among radio station managers in West Java regarding herbal medicine advertisements. A majority of the key informants, including both primary radio operators and supporting stakeholders, admitted that they did not routinely verify the operational legality of the products being advertised—particularly whether these products held valid distribution permits from BBPOM (Badan Pengawas Obat dan Makanan/Regional Indonesian Food and Drug Supervisory Agency).

This lack of verification was not attributed to ignorance of regulatory norms, but rather to the economic pressures faced by the radio industry. One station manager rationalized the practice by stating:

“We are a private business. Our priority is to survive. If we had to double-check every product’s legality, we might lose the few advertisers we have left.”

However, this pragmatism has public health and ethical implications. Several loyal listeners, according to the respondents, expressed discontent as their preferred radio content became saturated with herbal advertising, which most of which had never previously appeared. A significant portion of this content included healing testimonials, presented as endorsements from supposedly recovered patients. These raised concerns among both audiences and regulators regarding their authenticity and potentially misleading nature.

A regulatory official from BBPOM West Java offered a clear stance on the issue:

“Testimonials in herbal advertisements are no longer allowed in public media. They fall into the category of overclaiming because they exaggerate and often mislead listeners. We’ve seen ads suggesting one product can cure everything—from indigestion and heart problems to stroke and even COVID-19.”

Such exaggerated claims were especially prevalent during the pandemic, with ads asserting that a single product could address “1,000 diseases.” Another genre of overclaiming was frequently found in adult vitality supplements, which, according to the research team’s fieldwork, often employed bombastic, sensational, and emotionally charged language to enhance perceived efficacy.

In addition to these messaging concerns, BBPOM West Java regularly encountered inconsistencies between the claims made in aired advertisements and the data originally submitted during the licensing process. One regulator described a typical example:

“A product might be licensed to relieve flu symptoms. But in the actual broadcast, it gets promoted as a remedy for cough, asthma, or entirely different conditions not mentioned in the original permit.”

This divergence not only constitutes a breach of the licensing terms, but also poses a medical safety risk. As the agency emphasized, herbal products—like pharmaceutical drugs—must be used based on proper dosage and individual health profiles, including the patient’s body weight and condition. However, most herbal advertising, especially on radio, tends to generalize usage instructions and promotes a one-size-fits-all approach, which could endanger consumers who use the product without appropriate guidance.

The situation is further complicated by a post-pandemic surge in new herbal medicine manufacturers. BBPOM noted a growing trend of individuals who, after experiencing personal recovery from herbal treatments, were inspired to commercialize those remedies. According to an official:

“We’ve seen a sharp increase in consultation requests about licensing herbal products since COVID. But many of the applicants are driven by personal experience, not clinical evidence. They’re enthusiastic, but often lack any pharmacological or scientific background.”

These aspiring entrepreneurs often encounter regulatory barriers because they do not employ qualified pharmaceutical or medical professionals, which is a requirement for formal product registration. Moreover, their products are typically supported by personal anecdotes rather than empirical studies or peer-reviewed medical literature, which raises questions about their scientific validity.

BBPOM West Java has reiterated the importance of evidence-based product claims and compliance with advertising standards to protect the public. Without stronger oversight and alignment between regulatory enforcement and media accountability, the proliferation of unverified herbal claims through mainstream radio may continue to pose serious risks to consumer safety.

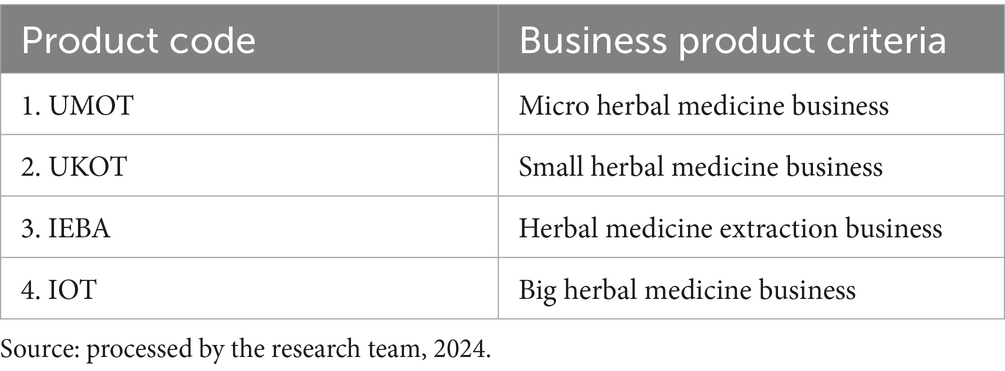

Therefore, seeing this phenomenon, the classification of herbal medicine entrepreneurs is made very detailed by BBPOM to be included on the product cover (see Table 2) to maintain and anticipate the quality of the herbal medicine.

In addition to the information from Table 2, the criteria for herbal medicines are also divided into three referring to the content of the medicine. Namely TM (traditional medicine), FF (Fito Pharmaka/herbal medicines that have passed tests on animals and humans), and FFHT (standardized herbal medicine).

BBPOM West Java also assesses the importance of upholding the rules regarding herbal advertising because there is a phenomenon of alternative clinics also often prescribing herbal medicines to people who are patients. BATRA, the BBPOM code for alternative medicine, is required to take care of a permit to the center if the herbal medicine is packaged as packaged drugs such as capsules, syrups, and derivatives. BATRA is allowed to BBPOM not to take care of its permit if it provides herbal medicine to patients in the form of herbal medicine taken at the treatment location. As for the existence of a radio that also becomes an outlet for the sale of herbal medicines, it is considered not a problem as long as the drugs sold already have a distribution permit from BBPOM.

BBPOM West Java has been in charge of supervising violations in terms of advertising in conventional mass media such as radio and then reported to the head office (BPOM/Food and Drug Supervisory Agency in Jakarta) for the execution of its sanctions. This pattern occurs because the Central BBPOM has synergized with the Central KPI and the Ministry of Communication and Informatics which has strong authority related to broadcasting media operational permits. According to informants at BBPOM West Java, during the 2018–2022 period, they have reported hundreds of violations of the advertisement with the fastest sanction being the reduction of advertisements in conventional mass media.

The findings of this study align with earlier research showing that distorted and non-compliant herbal medicine advertisements are not an isolated phenomenon, but part of a larger pattern in the Indonesian media landscape. Supardi et al. (2011) conducted a cross-sectional descriptive study in Jakarta, Yogyakarta, Denpasar (Bali), Medan (North Sumatra), and Banjarmasin (South Kalimantan). Their results demonstrated widespread advertising violations in traditional medicine promotions, particularly on local media platforms. These violations included overclaiming, broadcasting of unregistered products, and deviations between what was approved by BPOM and what was eventually aired. Their earlier study in 2007 revealed that out of 717 advertisements, 60% were deemed ineligible due to exaggerated claims or the absence of prior review by BPOM.

This trend has continued. According to BPOM RI (2021), in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, 15.89% of 577 applications for herbal advertising were rejected for non-compliance with regulations, and 3.92% required revisions. These figures reflect systemic gaps in pre-broadcast scrutiny and regulatory follow-through, especially in radio advertisements.

Similar advertising violations have been observed internationally. In Nigeria, Ahaiwe (2019) found that manipulative herbal ads, promoted as miracle cures, ultimately harmed public health. In Sri Lanka, Rufaideen et al. (2022) reported that only 8.1% of herbal ads included registration numbers and just 53.3% listed manufacturer contact details, reflecting poor regulatory compliance.

In Indonesia, Kristiana et al. (2013) documented misleading strategies such as guaranteed recovery claims, side-effect denial, and patient endorsements—frequently aired without proper registration. Pambudi and Kholidah (2020) added that absolute terms like “safe,” “risk-free,” or “number one” were common and often exceeded permitted airtime durations. Despite these infractions, such ads were persuasive in driving public preference toward traditional medicine.

This effect is understandable given media saturation. Dana (2011) estimated exposure to 3,000 ads per day, which shapes belief systems. Kristiana et al. (2013) noted that herbal providers often offer complete packages, from diagnosis to spiritual treatment, making their services attractive to the public.

From a political economy lens, this reflects Mosco’s (2009) argument that in market-dependent media, broadcasters commodify both their platform and audience trust. Herbal ads dominate not because of accuracy, but due to advertisers’ financial clout (Heryanto, 2017; Nasution, 2018). Weak enforcement by BBPOM and KPID, due to fragmented authority, illustrates Harvey’s (2005) neoliberal critique—where the state retreats and enforcement becomes inefficient. Rose (2007) frames this shift as burdening individuals with the responsibility to interpret health messages, even when the content is misleading.

Such disjunction was confirmed by BBPOM West Java officers, who noted frequent mismatches between aired claims and licensed content. This aligns with Supardi et al. (2011), who previously found high rates of overclaims and unregistered ads, persisting despite updates to BPOM regulations in 2017 and 2019. The situation worsened post-pandemic as new herbal entrepreneurs (many lacking formal pharmacological knowledge) entered the market (BPOM RI, 2021).

Culturally, this is reinforced by a symbolic trust in traditional medicine. As Dew and Liyanagunawardena (2023) argues, during health crises, communities often turn to traditional remedies not only because they are accessible but because they are perceived as pure, spiritually grounded, and culturally authentic. These remedies offer a sense of safety and identity when institutional healthcare systems are seen as distant or inadequate. In Indonesia, Sangkaen and Sumarauw (2022) and Kurniasari et al. (2023) confirm that such beliefs support consumer loyalty to herbal narratives. This study found repeated examples of exaggerated claims such as “1 product cures 1,000 diseases,” which persisted across multiple stations. A BBPOM official warned: “We’ve seen ads suggesting one product can cure everything—from indigestion and heart problems to stroke and even COVID-19.”

The appeal of herbal remedies is also economic. As Alugbin (2019) noted, they can be obtained without prescription or clinical bureaucracy, making them more accessible than pharmaceutical options. This convenience has contributed to the sharp increase in distribution permits—from 5,128 in 2017 to 11,404 by 2021 (BPOM RI, 2021).

Regulatory disconnection and structural incoherence

Despite Indonesia’s comprehensive regulatory framework—including Law No. 32/2002 on Broadcasting (Pemerintah Indonesia, 2002), KPID’s SPS (Gazette of the Republic of Indonesia, 2016), BPOM regulations (2017; 2019), and the Consumer Protection Law (1999)—enforcement is hindered by fragmented authority. BBPOM can only monitor and report; KPID can issue warnings but lacks sanctioning power. As Supardi et al. (2011) observed, contracts between broadcasters and advertisers often bypass pre-approval. Susetyo et al. (2019) note KPID fulfills its mandate, yet remains largely supervisory. Economic vulnerability further weakens oversight—Pambudi and Kholidah (2020) show that many stations rely on herbal ads for survival, discouraging strict compliance.

Toward integrated governance

Rather than isolated lapses, the persistence of violations reveals structural disconnection. Regulatory silos among BBPOM, KPID, BPOM, and Kominfo lead to delays and jurisdictional confusion. To resolve this, a formal inter-agency task force is needed, grounded in an MoU and including PRSSNI to represent media industry realities. The task force should conduct joint ad reviews, maintain a shared violation database, coordinate sanctions, and deliver media literacy outreach. Such integration responds to Harvey’s (2005) critique of state retreat in neoliberal systems, restoring regulatory accountability through collective governance.

The political economy of herbal advertising

These issues reflect deeper market dynamics. Herbal advertisers are not only content funders—they reshape media ownership and narratives. As Heryanto (2017) and McQuail (Nasution, 2018) argue, commercial media structurally favors capital over public interest. Mosco (2009) describes how communication becomes commodified, while Rose (2007) warns of “responsibilized” consumers navigating deregulated risk alone. This media-health-commercial nexus thrives on weak oversight and strong cultural legitimacy, posing enduring challenges to public health ethics and media accountability in Indonesia.

Conclusion

This study reveals how the post-pandemic rise in herbal medicine advertising has reshaped Indonesia’s radio landscape economically, institutionally, and ethically. Herbal advertisers have not only filled the financial void left by declining state and corporate sponsorship but, in several cases, have also taken on roles of content control and ownership. This transformation reflects deeper structural dynamics, including economic determinism in the media industry, regulatory fragmentation, and a cultural reorientation toward “natural” remedies in response to biomedical uncertainty and institutional distrust.

Through the lens of political economy and neoliberal governance, the findings show how media institutions, especially in peripheral regions such as West Java, are increasingly steered by market survival imperatives. As regulation fails to keep pace with commercialization, the public becomes more vulnerable to persuasive and frequently exaggerated health claims. The proliferation of testimonial-based advertising and cure-all narratives, often lacking scientific validation or dosage guidance, presents tangible risks to public health.

Theoretically, this research contributes to the understanding of how commercial actors reshape media ecosystems under neoliberal conditions, where state institutions retreat from their protective functions and individuals are expected to independently navigate complex health decisions. It further enriches regional media studies by revealing how economic precarity in smaller broadcast markets creates openings for health entrepreneurs to embed themselves not only in advertising flows but also in editorial direction and institutional control.

To respond to these risks, the study advocates the creation of a dedicated multi-agency task force. This is not merely a call for enhanced synergy but a proposal for a formal institutional framework. The task force should unite KPI, BBPOM, BPOM, Kominfo, and PRSSNI under a Memorandum of Understanding that includes mandates for pre-broadcast review mechanisms, synchronized sanction systems, centralized monitoring of violations, and widespread public education through media literacy campaigns. Only through institutional reform and cross-sector enforcement can the ethical integrity of health communication be preserved within Indonesia’s evolving media economy.

Future research should examine how institutional disjuncture across Indonesia’s broadcasting, health, and information systems enables the persistence of misleading herbal advertising. Comparative analyses across media markets and deeper investigations into the cultural power of testimonial narratives could clarify how traditional health beliefs are commodified and how that affects both regulatory effectiveness and public trust in an era of increasing digital and commercial influence.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not necessary for this study in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

MA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DP: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, SW: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. SP: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. AA: Visualization, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ahaiwe, E. O. (2019). Advertising media regulation and sale of herbal medicines in Nigeria: implication for public health and safety. RSU J. Strateg. Internet Bus. 4, 612–631.

Alugbin, M. (2019). Register shift and sexuality: a discourse reading of herbal medicine advertisements, UNIUYO Journal of Humanities (UUJH), 23, 283–298.

Anbarasan, S., Manikandan, S., Prasanth, D., et al. (2023). A comprehensive review on global market value, commercialization and product development of herbal medicines. Phytomedicine Plus 3:100333. doi: 10.1016/j.phyplu.2022.100333

Baskoro, R. F., and Sucahya, M. (2023). Mandiri FM Cilegon radio broadcasting management strategy in attracting listeners’ interest in the Nyenyore program. LONTAR: Jurnal Ilmu Komunikasi 11, 177–184. doi: 10.30656/lontar.v11i2.7814

BPOM RI (2021). Laporan Tahunan 2021 Badan Pengawas Obat Dan Makanan Republik Indonesia. Laporan Tahunan BPOM TA 2021: 1–179. Available online at: https://www.pom.go.id/new/files/2022/LAPORANTAHUNAN2021/0.BPOM/LAPTAHBPOM2021.pdf

Creswell, J. W., and Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). California: Sage Publications.

Devi, I. C. (2020). Songgolangit FM radio convergence strategy in the middle of the broadcasting industry competition in Ponorogo. J. Islam. Commun. 1, 1–18. doi: 10.21154/qaulan.v1i0.2380

Dew, K., and Liyanagunawardena, S. (2023). Traditional Medicine and Global Public Health. In: P. Liamputtong (eds) Handbook of Social Sciences and Global Public Health. Springer, Cham. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-25110-8_16

Gazette of the Republic of Indonesia. (2016). Pedoman Perilaku Penyiaran (P3) Dan Standar Program Siaran. Available online at: http://www.kpi.go.id/download/regulasi/P3SPS_2012_Final.pdf

Gebregeorgise, D. T., Bilal, A. I., Habte, B. M., Tilahun, Z., Fenta, T. G., and Yeshak, M. Y. (2019) Concomitant use of medicinal plants and conventional medicines among hypertensive patients in five hospitals in Ethiopia Ethiop. J. Health Dev. 33 174–180. Available online at: https://ejhd.org/index.php/ejhd/article/view/2385

Heryanto, G. G. (2017). Ekonomi Politik Media Penyiaran: Rivalitas Idealisme Nilai Islami Dan Mekanisme Pasar. Communicatus Jurnal Ilmu komunikasi 1, 85–98. doi: 10.15575/cjik.v1i1.1212

Hika, D., Mammo, W., Hymete, A., Tolessa, T., and Yeshak, M. Y. (2020). Blood pressure lowering effect of the aqueous extract of Satureja. Ethiop. Pharm. J. 36, 81–90. doi: 10.4314/epj.v36i2.3

Kristiana, L., Andarwati, P., and Nuraini, S. (2013). Kajian Regulasi Iklan Sarana Pengobatan Tradisional Di Surat Kabar. Bulet. Penelit. Sist. Kesehat. 16, 48–57.

Kurniasari, R., Indratno, D. L., and Wahyujatmiko, R. S. (2023). Pengaruh Brand Image, Harga, Kualitas Dan Kemasan Terhadap Minat Beli Konsumen Jamu Sabdo Palon Di Sukoharjo. Edunomika 8, 1–10.

Meshesha, S. G., Yeshak, M. Y., Gebretekle, G. B., Tilahun, Z., and Fenta, T. G. (2020). Concomitant use of herbal and conventional medicines among patients with diabetes mellitus in public hospitals of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. :3145630. doi: 10.1155/2020/3145630

Mukherje, P. K. (2019). Quality Control and Evaluation of Herbal Drugs Evaluating Natural Products and Traditional Medicine, Amsterdam: Elsevier, Available at: https://bit.ly/3GwYe7Q

Nasution, N. (2018) Strategi Manajemen Penyiaran Radio Swasta Kiss Fm Dalam Menghadapi Persaingan Informasi Digital Jurnal Interak.: Jurnal Ilmu Komun. 2 167–178. Available online at: https://jurnal.umsu.ac.id/index.php/interaksi/article/view/2094

Opoku, Eleanor Amoabea. (2021). Effects of social media use on the academic performance of students of public tertiary institutions in Ghana. (10206539): 1–13. University of Ghana. Available online at: http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh

Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J. P., Duan, N., and Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 42, 533–544. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

Pambudi, Dwi Bagus, and Kholidah, Nur. (2020). Aspek Hukum Mengenai Penayangan Periklanan Pengobatan Dan Kesehatan Tradisional Berdasarkan Regulasi Di Indonesia. Proceeding of The 11th University Research Colloquium 2020: Bidang Sosial Humaniora dan Ekonomi 11(1): 193–198. Availbale online at: http://repository.urecol.org/index.php/proceeding/article/view/989/958.

Pemerintah Indonesia (2002). Undang-Undang Nomor 32 Tahun 2002 Tentang Penyiaran. Indonesia: Ministry of Communication and Digital, 1–34.

Republik Indonesia (1999). Undang-Undang Nomor 8 Tahun 1999 Perlindungan Konsumen. Undang-Undang Nomor 8 Tahun 1999 (8): 1–19. Available online at: https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Home/Details/45288/uu-no-8-tahun-1999

Rose, N. (2007). The politics of life itself: Biomedicine, power, and subjectivity in the twenty-first century. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rufaideen, F., Liyanage, C. K., Ranasinghe, C., and Ranasinghe, P. (2022). Evaluation of ayurvedic and herbal product advertisements on electronic and print media in a developing country. J. Pharm. Health Serv. Res. 13, 109–114. doi: 10.1093/jphsr/rmac009

Sangkaen, A., and Sumarauw, T. (2022) Dampak Psikologis Iklan Obat Herbal Di Media Sosial Terhadap Kaum Pria Usia 50 Tahun J. Psychol. 3 63–70. Available online at: https://ejournal-iakn-manado.ac.id/index.php/humanlight/article/download/1199/773

Saputra, M. I., Alfiazahra, A., Gunadi, V. J., Anggawen, A. S., and Ariani, S. A. (2023). The audience’s acceptance of a single parent in the film “Susah Sinyal”. Commun Jurnal Ilmu komunikasi 7, 21–42. doi: 10.15575/cjik.v7i1.25594

Supardi, S., Handayani, R., Herman, M., Raharni, R., and Susyanty, A. (2011). Kebijakan Periklanan Obat Dan Obat Tradisional Di Indonesia. Bulet. Penelit. Sist. Kesehat. 14, 59–67. doi: 10.22435/bpsk.v14i1Jan.2296

Susetyo, S., Ikram, I., Mulyaningsih, H., Raidar, U., Benjamin, B., and Ratnasari, Y. (2019). Peran Komisi Penyiaran Daerah (Kpid) Provinsi Lampung Dalam Pengawasan Lembaga Penyiaran Di Provinsi Lampung. SOSIOLOGI: Jurnal Ilmiah Kajian Ilmu Sosial dan Budaya 21, 97–109. doi: 10.23960/sosiologi.v21i2.40

Tilahun, Z., Bilal, A. I., Teshome, D., Habte, B. M., Yeshak, M. Y., and Fenta, T. G. (2018). Concomitant use of medicinal plants and conventional medicines among adult patients with diabetes in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Ethiop. Pharm. J. 34, 25–32. doi: 10.4314/epj.v34i1.3

Utami, R. I., and Herdiana, A. (2021). Pemaknaan Pendengar Terhadap Iklan Testimoni Nutrisi Herbal Nariyah Di Radio Kasihku FM Bumiayu Dalam Teori Resepsi Stuart Hall. Sadharananikarana: Jurnal Ilmiah Komunikasi Hindu 3, 509–520. doi: 10.53977/sadharananikara.v3i2.356

World Health Organization (2019). WHO global report on traditional and complementary medicine. Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241515436

Keywords: herbal medicine advertising, Indonesian radio, media regulation, food and drug supervisory agency, public health communication, political economy of media

Citation: Abdurrahman MS, Putra DKS, Widyaningrum SY, Ali A and Parsono S (2025) Between public health and commercial pressure: health communication and media oversight in Indonesia local radio. Front. Commun. 10:1495147. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1495147

Edited by:

Mariamawit Y. Yeshak, Addis Ababa University, EthiopiaReviewed by:

Nugroho Agung Pambudi, Sebelas Maret University, IndonesiaDilu Teshome, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia

Copyright © 2025 Abdurrahman, Putra, Widyaningrum, Ali and Parsono. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Muhammad Sufyan Abdurrahman, bXVoYW1tYWRzdWZ5YW5AdGVsa29tdW5pdmVyc2l0eS5hYy5pZA==

Muhammad Sufyan Abdurrahman

Muhammad Sufyan Abdurrahman Dedi Kurnia Syah Putra

Dedi Kurnia Syah Putra