- 1Faculty of Arts, Celtic Studies and Philosophy, Arts and Humanities Institute, Maynooth University, Maynooth, Ireland

- 2Media Communication and Cultural Studies, Goldsmiths University of London, London, United Kingdom

Introduction: Digital feminist fabulations offer a mode of resistance to algorithmic patriarchies that govern visibility and acceptability on social media platforms. Following Bergson (1932/1977) and Deleuze and Guattari (1994), and building on Haraway’s (2013, 2016) theorisation of fabulation as a practice of radical collective imagination, this study examines how feminist and queer visual cultures on Instagram respond to patriarchal censorship. Social media moderation policies often reproduce heteronormative, white, and able-bodied norms by restricting the visibility of diverse bodies and sexualities. In this context, feminist digital fabulation becomes a creative intervention into algorithmic injustice.

Methods: This paper draws on a four-year qualitative digital ethnography tracking the online practices of ten feminist and queer artists on Instagram. Data collection included longitudinal observation of public posts, artist statements, comment threads, and semi-structured interviews with each artist. The study focuses on the case of Christine Yahya (@pink\_bits), a Sydney-based Armenian-Australian queer feminist artist and designer, to offer an in-depth analysis of one artist’s fabulatory resistance to platform regulation. Yahya’s work illustrates bodies and experiences marginalised in public discourse, including representations of disability, fatness, menstruation, masturbation, and mental illness.

Results: Findings indicate that Yahya’s art practice functions as a feminist digital fabulation in response to repeated shadowbanning and content removal on Instagram. Yahya creates stylised, illustrative representations of “bodies we are told to hide,” drawing attention to corporealities censored or invisibilised by content moderation systems. Rather than retreating in the face of moderation, Yahya transforms content reduction into a creative prompt. Her illustrations reimagine censored subjects as central, joyful, and unapologetically visible, working against the logics of algorithmic sorting and exclusion. These images do not only resist dominant visual cultures but actively produce alternative bodily imaginaries.

Discussion: This case study demonstrates how feminist digital fabulation operates as a creative political response to algorithmic governance. Yahya’s work offers a situated example of what Haraway (2016) calls “speculative fabulation” —a mode of world-building that defies normative constraints through collective reimagining. The practice of producing art that “troubles regulatory boundaries” generates a form of knowledge and critique that emerges within, and against, the infrastructures of platform capitalism. In doing so, Yahya’s digital art challenges the techno-patriarchal ideologies embedded in content moderation protocols and offers a vital feminist aesthetic that reclaims public visual space. This study contributes to cultural studies and digital media scholarship by theorising feminist fabulation as an embodied, affective, and strategic mode of resistance to algorithmic censorship.

Fabulation as a scholarly framework

Feminist scholarship on fabulation is inspired by the work of Haraway (2013, 2016) and often draws on Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of fabulation as it appears in What is Philosophy? (Deleuze and Guattari, 1994). In his earlier works, and later in What is Philosophy? Deleuze responds to, and changes, Henri Bergson’s notion of fabulation. Many aspects of Bergson’s thought attracted Deleuze. Firstly, the concept of multiplicity, secondly, duration (time) which is part of Deleuze’s famous “becomings” (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987). Another aspect that attracted Deleuze, which is indeed connected to the first, is Bergson’s criticism of the concept of Kant’s negation in Creative Evolution (see Leonard and Moulard-Leonard, 2022). Both Deleuze and Bergson see fabulation as a powerful means of thought, but they emphasise different political potentials. In “The Two Sources of Morality and Religion” (Bergson, 1932/1977), Bergson introduces the concept of “la fonction fabulatrice” (storytelling, the social fabulatory or mythical function) which is translated in English as “the myth-making function” (see Bergson, 1932/1977, pp. 108, 109, 119, and 124 as examples). The myth-making function is also referred to as the process of fabulation, namely, the human capacity to create narratives as a response to the limitations of intellect and reason. This is the process by which “A fiction, if its image is vivid and insistent, may indeed masquerade as perception” (Bergson, 1932/1977, p. 109). Fabulation gives new meaning to things. It is the process by which the older woman becomes known to some as “the evil witch,” a weed in one country is known as a vital source of nourishment in another country, a bank note (a printed piece of paper) has financial value in some countries and not in others, and so on. Bergson uses the idea of fabulation to explain the imaginative function that allows people to construct stories with moral or social significance that can serve to unify or divide communities. This function is pragmatic: it helps individuals and societies create coherence, to maintain status quo and protect against existential threats. For example, the construction of race and racisms are practices of fabulation that maintain Colonial status quo, in which “whiteness, among Whites, and petty Whites in particular, is neither an absolute nor an ontological fact. It is a social relation constantly reproduced by the forces that privilege it” (Bouteldja, 2023, p. 101). Bergson saw fabulation as productive, as a way of generating visions about how individuals in societies are connected. It is a luxury that society is able to develop only after people have safety and comfort. He asks: “How is it possible to relate to a vital need those fictions which confront and sometimes thwart our intelligence, if we have not ascertained the fundamental demands of a life?” (Bergson, 1932/1977, p. 111). His understanding of fabulation as religion, as social order, remained somewhat conceptually limited, as it was rooted in what he perceived as the moral needs of a community, reinforcing social norms rather than critically considering them.1

Deleuze’s writings on fabulation, particularly his later work with Guattari, reinterpret fabulation as a creative, political force with a more radical potential than Bergson’s conservative framing. In What is Philosophy? Deleuze and Guattari argue that fabulation is not simply about creating myths for cohesion but is a powerful creative act of transformation (Deleuze and Guattari, 1994, p. 171). Here, fabulation is central to art and philosophy: “the artist is a seer, a becomer” (Deleuze and Guattari, 1994, p. 171), fabulation is a way to bring “forth events” (Deleuze and Guattari, 1994, p. 199), to envision becomings that can break with conventional identities and social norms. Deleuze takes fabulation beyond Bergson’s social function, re-casting it as a disruptive or revolutionary practice (Deleuze and Guattari 1994, pp. 117–201). Fabulation allows communities to envision and assert new identities, to make futures that challenge dominant ideologies. This approach aligns fabulation with what Deleuze (1995) calls “minor literature,” a form of writing through which minorities claim voice and express collective desires. Here, fabulation is the imaginative force that gives public audiences to experiences that official histories and dominant narratives often silence, making it a vehicle for political resistance and change. In contrast to Bergson’s fabulation as primarily social and stabilising force, Deleuze and Guattari view fabulation as dynamic and radical, capable of creating new worlds, becomings, and subjectivities that disrupt existing social orders. Explaining their use of fabulation, Deleuze and Guattari (1994, p. 171) state: “Creative fabulation. Goes beyond the perceptual states and affective transitions of the lived.” Fabulation is the materialisation of a motif in fiction, art, philosophy or music: it is a new meaning made in a creative text.

Research methods and creative practices can be modes of fabulation. Haraway (2016) famously presents science fiction as a practice of fabulation in Staying with the Trouble. Haraway introduces “speculative fabulation” as a means of envisioning alternate realities, bridging science, feminism and fiction to challenge dominant narratives. Haraway advocates for making kin, not babies, saying: “The task is to make kin in lines of inventive connection as practice of learning to live and die well in a thick present” (Haraway, 2016, p. 1). Inventive connection is thus a form of speculative fabulation, urging us to reimagine human and non-human relationships in order to create a more liveable future. Haraway’s work highlights storytelling as a powerful critical and creative method to create worlds of possibility. Stories “propose and enact patterns for participants to inhabit, somehow, on a vulnerable and wounded earth” (Haraway, 2016, p. 10). Here, storytelling is not a method of keeping the status quo like it is for Bergson, rather, storytelling is an active, constructive force that enables feminist and environmental critique and vision.

Donna Haraway’s work on feminist fabulation is most fully developed in The Companion Species Manifesto (Haraway, 2013) and Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Haraway, 2016). In these texts, Haraway argues that storytelling is a vital method for feminist and ecological thought, offering a way to challenge anthropocentrism, binary thinking and narratives of linear progress. Feminist fabulation is not simply imaginative fantasy, but a speculative and materialist practice of world-making that unsettles dominant epistemologies and reorients attention to multispecies entanglements. One of the central aspects of Haraway’s approach is her embrace of storytelling as a method that combines science fiction, speculative fabulation, string figures, and speculative feminism—what she refers to collectively as “SF.” This multiplicity of SF signals her intention to traverse the boundaries of traditional academic disciplines and forms of knowledge. Her fabulations are not utopian or escapist; they are rooted in the “trouble” of the present and are committed to ethical responsibility in the context of the Anthropocene and the Capitalocene. Haraway’s insistence on “making kin, not babies” articulates a post-anthropocentric ethics that prioritizes alliances and relationality over reproductive futurism or human exceptionalism.

Haraway’s approach to feminist fabulation has had significant impact across a range of scholarly disciplines, including feminist theory, science and technology studies (STS), environmental humanities, posthumanism, literary and cultural studies. In the environmental humanities and posthumanist theory, scholars such as Rosi Braidotti, Anna Tsing, and Deborah Bird Rose have taken up fabulation as a mode for thinking with nonhuman others and for developing ecological ethics grounded in multispecies entanglement. The concept of the Chthulucene, introduced by Haraway as an alternative to the Anthropocene, has gained traction in discussions of extinction, more-than-human futures, and environmental justice. In feminist science studies, fabulation has been used to critique and reimagine technoscientific knowledge practices. Scholars such as Michelle Murphy and Mel Y. Chen have drawn on Haraway’s work to develop frameworks that attend to environmental toxicity, data politics, and the materiality of chemical and racialized life. In queer and decolonial theory, fabulation resonates with speculative world-building and alternative temporalities. Writers such as Eva Hayward, Alexis Pauline Gumbs, and Vanessa Agard-Jones explore the generative possibilities of fabulation for imagining otherwise, while also remaining attentive to histories of erasure and resistance. In this context, feminist fabulation becomes a method for disrupting colonial futurities and for foregrounding submerged or marginalized modes of storytelling and ontology.

Haraway’s influence extends into creative and practice-based research, where her fabulatory method is used in fields such as performance studies, speculative design, and eco-fiction to enable creative-critical engagement with climate, species and social imaginaries. However, her work is not without critique. Some scholars argue that Haraway’s notion of kinship risks universalizing experience or obscuring the particularities of colonial and racial histories. More recently, Jungnickel (2022) and Jungnickel (2024) combines historical research, craft and performance to not just recreate cycling costumes worn by women but to make contemporary feminist medias and agendas. Jugnickel’s method allows her to engage with the material culture of the past, highlighting the gendered politics of embodiment and materiality. Jugnickel’s methods re-enact and re-create historical garments in order to generate new understandings of historical phenomena. Similarly, Coleman (2020) facilitates collaging workshops and other collaborative activities that present participants’ hopes, fears and expectations. These visual practices of fabulation allow participants to make objects that present their worlds in new ways. Coleman’s (2020, p. 50) “future-oriented affect” links fabulation to the felt experiences of time and temporality, emphasising how storytelling can materialise futures in the present. This approach connects with feminist theories of affect, showing how narratives shape not just what we think but what we feel about possible futures. In particular, Coleman (2020, p. 53) examines how popular media, and the material politics of glitter, can “pre-fabricate” futures, reinforcing or resisting dominant expectations and ideologies.

Feminist scholarship on fabulation builds Donna Haraway’s foundational work, now encompassing a range of theories on storytelling, narrative construction, and imagination in feminist frameworks - especially Science Fiction (Truman, 2021). For example, Isabelle Stengers has also contributed to fabulation in feminist theory through her concept of “cosmopolitics” (Stengers, 2010). Donna Haraway compares Stengers’ cosmopolitics to fabulations, saying “Isabelle Stengers’s kind of fleshy cosmopolitics and SF writers’ practices of worlding page number.” Stengers emphasises the creative process of ‘slowing down’ thinking, allowing room for alternative ways of understanding and valuing the world. She argues that fabulation allows marginalised or silenced perspectives to emerge, providing narrative space for “minor voices” in the face of dominant knowledge systems. In her view, fabulation is a critical process that makes space for speculative possibilities in political and philosophical thought, where new worlds can be imagined collectively.

Across these and other works, feminist fabulation has shifted from conceptual frameworks to applications in feminist media studies and art making (Manning, 2019) framing storytelling (in our case, digital storytelling on Instagram) as a means of creating politically and ethically charged ‘what if’ scenarios. This scholarship underscores the fact that fabrication is not just imaginative but also deeply situated in material and affective practices that shape our capacity to envision change. Taking inspiration from Haraway’s multispecies storytelling (Haraway, 2016, p. 10) we have drawn together the words of Christine Yahya across three different mediums as a source of analysis for our research. Through thematic analysis of 2 interview transcripts, textual analysis of yahya social media posts, and an aesthetic visual analysis of their art works, we stitch together a story made up of Fabulations from yahya posting and art practices. The data presented here is drawn from a 4 year Digital Ethnographic study which explored the ways feminist and queer Instagram artists used social media posts and art making practices to create spaces of belonging online for marginalised groups (Willcox, 2023). The interview transcripts, illustrations and social media posts are read together as layered fabulations on feminist digital art making.

Below is an image taken from the work of Yahya’s Instagram page (@pink_bits) who we introduced above as queer, feminist artist and graphic designer living and working in Sydney, Australia.

Figure 1 shows yahya edited animation, which states that “femxle sexual pleasure is important.” She told us that this was her first post deleted by Instagram. It was an animation of a woman masturbating. She refers to her post as “relatable and unoffensive” and points out to her followers that “a womxn’s body is still considered taboo in many ways” and a sexual womxn is highly taboo.

Figure 1. Yahya’s moderated animation about masturbation. Image reproduced from Instagram with permission from @pink_bits.

Although art about men masturbating is also moderated on Instagram, the ways women’s bodies are moderated on the platform are unique, as male nipples are allowed and women’s are not, unless in the context of breastfeeding or breast cancer surgery (Yahya, 2024). This speaks to the ways content moderation processes can reflect normative biases around bodies and the ways women’s bodies are more often sexualised in public spaces (Willcox, 2025). Yahya goes on to describe these restrictive measures in one of our interviews through the ways the moderation, promotion and visibility is constructed to ensure creators stay trapped within their own bounds of creative practice:

I feel like when you are popular, or if you find popularity for a particular reason, Instagram rewards your engagement by creating the same thing repetitively… If I create something maybe about like, I don’t know, psoriasis or masturbation or disability – something else that’s not as consumable by the algorithm, it just hides everything, and it’s kind of shitty. (Yahya, 2022)

For Yahya, creating content that is outside the bounds of her artistic brand is when she feels she is more at risk of being moderated, removed or reduced. She says in the caption on the below Instagram post “female pleasure is important, it is not offensive, it needs representation and I’ll continue to illustrate it” (Yahya, 2022). Moderation is experienced as personal to Yahya, and, as she states in the excerpt above, drawing things that aren’t as consumable by the algorithm means Instagram hides everything “and it’s kind of shitty.” Instagram is a part of her everyday lived reality, and having content about bodies deleted affects the way she feels about her body. Yahya describes this affect by relaying her experience growing up with an eating disorder in one of our interviews:

As an eating disorder survivor, coming through my teenage years and early twenties, like it was quite rough. So seeing imagery, even though I made it, was still helpful for, you know, imagining a body that I can identify with …And in my work, I want to provide more imagery of, you know, just bodies being bodies and not bodies that are like not straining to be small and straining to not take up any space and, you know, are under pressure to look the way that, you know, society says we should look. (Yahya, 2022)

This comment on her experience as an eating disorder survivor demonstrates how fabulating, or visually re-imagining bodies she can identify with in the artwork that she makes, helps Yahya in her recovery. Her work is a bodily response to societal expectations of women’s bodies and affects the ways she feels she belongs within her own body. Saying that she draws bodies that aren’t straining to uphold the ways society expects them to look shows Yahya’s intention of making more space in media narratives for diverse bodies to be celebrated and accepted. This is an example of a fabulation on a digital platform as a feminist method of ‘refusal,’ because it brings together the idea that creativity can remake the experience of the body through resistance, but also, creates space for more diverse bodies embedded in social media.

When Yahya’s image of female masturbation (Figure 1) was taken down through a content moderation process, this prompted a reaction to the modes of exclusion where a body she drew, or could relate to, was deemed to not fit within the ways “society says we should look” (Yahya, 2022). She says in one of her Instagram captions for Deleuze and Guattari, fabulation, is not about the notion of cohesion but is a powerful act of becoming and transformation through creation. For Yahya, this act of creation is about taking up the challenge of pushing against regulatory guidelines which enforce restrictive notions of which bodies can be seen/accepted or celebrated in public space and which cannot. Media narratives that reinforce the ‘thin ideal’ attached to women’s bodies are one of the reasons she says she developed an eating disorder, and changing these narratives is her way of claiming back the agency she feels she lost. This is a form of fabulation, using digital animation to construct bodies as an explicitly transgressive act. It challenges norms by amplifying the visibility of non-normative bodies in social media spaces, creating images that disrupt conventional ideas of acceptability regarding gender, race, sexuality, class, disability, and other intersecting identities.

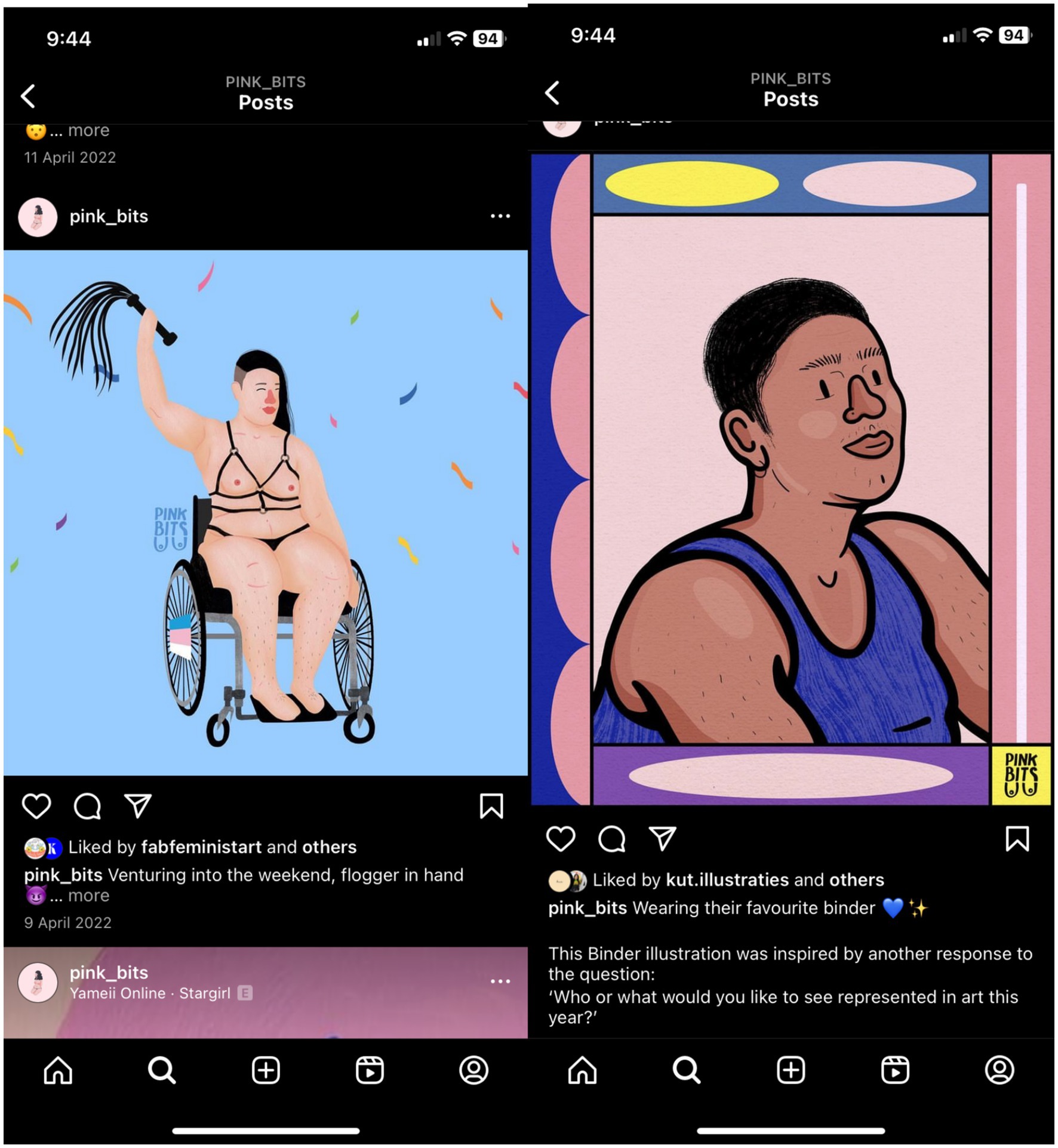

Yahya draws figures in her work which are often colourful, cute and fun. They are purposely ‘accessible’ she says so that she can draw about topics such as those in Figure 2 and access a broader public without having her content removed or reduced. The figure on the left is of a person in a wheelchair holding a “flogger” dressed in a kinky outfit. This theme of disability and sexuality is also something which often comes up in Yahya’s work, and is something she explicitly wants to create more media representation about (Aspler et al., 2022; Hall, 2018; Kaur and Saukko, 2022; Miller, 2017). The figure on the right of Figure 2 is a drawing Yahya made in response to a question she asked her followers “Who or what would you like to see represented in art this year?.” In response to this, she created a trans or non binary person wearing a binder. This action of asking her followers what kind of bodies they wanted to see in art work and then creating the artwork about a marginalised body, is another example of a feminist fabulation. The method of making meaning in this instance, comes from calling out for collective transformation through participatory engagement in the re-creation of bodies in digital spaces against normative boundaries of public visibility.

Figure 2. Yahya’s illustrations responding to followers interests in representation (2024). Image reproduced from Instagram with permission from @pink_bits.

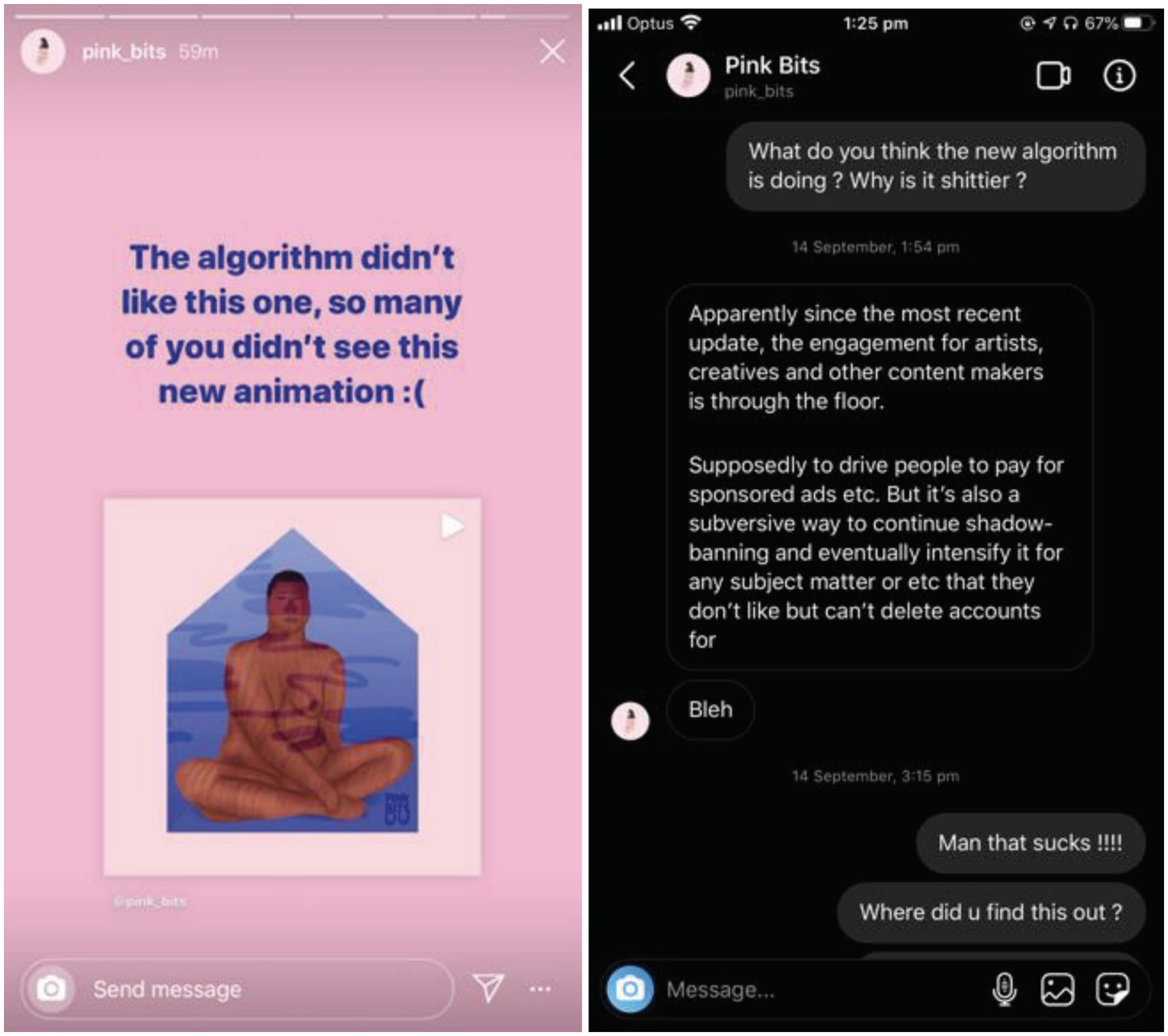

In Figure 3, in response to the image on the left, Yahya (2020) says she thinks the new moderation algorithms drive people to pay for sponsored ads but are also “a subversive way of continuing to shadowban any subject matter that they (Instagram) do not like but cannot delete accounts for.”

Figure 3. Yahya’s moderated animation, and a DM conversation about this (2019). Image reproduced from Instagram with permission from @pink_bits.

Analysing Yahya’s words and images makes it clear that her work is responsive to the exclusion of certain bodies through media narratives, yet she participates in, and contributes to, media narratives herself. Thus, this flow of agency between and among the body and Instagram needs to be considered in more detail. Yahya benefits from ‘calling out’ content moderation to her followers. However, by blaming what she calls ‘the algorithm’ for the moderation of her images, she gives digital platforms a “god like power” which neglects the fact that she is also an actor in making media narratives focus on bodies. Although there is a very different focus to her narrative on bodies than those that focus on reinforcing patriarchal beauty ideals, “anything that does modify a state of affairs by making a difference is an actor … makes a difference in the course of some other agent’s actions” (Latour, 2005, p. 71, quoted in Bucher, 2018, p. 51). Algorithmic systems can reconfigure bodies just as much as bodies can reconfigure algorithmic systems. The interplay between Yahya’s Instagram use and content moderation processes demonstrates the agentic flow of algorithmic feedback loops in the way that “agential intra-actions are causal enactments” (Barad, 2007, p. 176). This is reflected in Yahya’s description of using the features of Instagram to bolster profit:

I launched a new store maybe like a year ago, and I realised oh, I’m not reaching anyone. Anytime I post about a new product that I’ve made, my engagement goes down insanely. So I was like, OK, I’ll do a sale and I’ll sponsor a post. I’ll play the game, I’ll put some money behind it so it gets a bit seen. And then they decided that my advertisement didn’t meet with their guidelines, and so they wouldn’t let me sponsor any content, so people wouldn’t really see it. And I was like, ugh … (Yahya, 2022)

This interview excerpt shows how Yahya tries to advertise her work or do what Cotter (2019) calls “play the algorithm game,” but finds she still does not meet the guidelines, so her content cannot be sponsored. Playing the game here means learning the rules and making art and content that fits within these rules. While it wasn’t clear what specific post she was referring to in our interview, by relying on algorithmic systems and media narratives for visibility while also fighting back against Instagram’s rules on content moderation, Yahya demonstrates how complex the creation of the feminist fabulation can be as it requires participation and engagement from an audience or a collective, to transform and make new meaning through acts of creation.

Conclusion

The process of playing the algorithm game while ‘refusing back’ the system by which Yahya feels oppressed is a “feminist fabulation” because it shows the work of making meaning through creative process. Such ventures make “Possibilities of better worlds, and ideas of other worlds, other beings” (Hickey-Moody, 2023, p. 185). When fabulation is situated in algorithmic systems and patriarchal media infrastructures, to ‘refuse’ through fabulation requires:

A semblance of transcendence that is expressed not in a thing to be represented but in the paradigmatic character of projection and in the “symbolic” character of perspective. According to Bergson the Figure is like fabulation: it has a religious origin. But, when it becomes aesthetic, its sensory transcendence enters into a hidden or open opposition to the suprasensory transcendence of religion. (Deleuze and Guattari, 1994, p. 193)

Rather than think through religion, we think through the philosophy, political ideology and belief systems of feminism in this article. As a feminist fabulation is built on the notion of resistance, artists and specifically feminist Instagram artists, form key examples of how we might think through what it takes to fabulate aesthetically, to create new meaning in patriarchal spaces via creative means. This offers up an invitation to other artists, researchers and content creators to dive deeper into the meaning of feminist fabulation, offering space to create subtle transgressions through collective creation.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because this data is owned by Marissa Willcox. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Marissa Willcox bS5nLndpbGxjb3hAdXZhLm5s.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by RMIT University Human Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

AH-M: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MW: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The internet perpetuates patriarchal ideas by amplifying existing societal biases and inequalities through its platforms and algorithms. Social media often prioritizes content that reinforces traditional gender roles, as such material tends to generate high engagement. Additionally, online spaces can reproduce toxic masculinities through harassment, objectification of women and exclusionary behaviour. Algorithms designed without gender equity in mind may marginalize feminist or gender-diverse voices while disproportionately exposing women and marginalized groups to abuse. The underrepresentation of women in tech further influences the design and governance of online spaces in ways that maintain patriarchal norms.

References

Aspler, J., Harding, K. D., and Cascio, M. A. (2022). Representation matters: race, gender, class, and intersectional representations of autistic and disabled characters on television. Stud. Soc. Justice 16, 323–348. doi: 10.26522/ssj.v16i2.2702

Bergson, H. (1932/1977). The two sources of morality and religion. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Bouteldja, H. (2023). Rednecks and barbarians: Uniting the white and racialized working class. London: Pluto Press.

Coleman, R. (2020). Glitterworlds: The future politics of a ubiquitous thing. London: Goldsmiths Press.

Cotter, K. (2019). Playing the visibility game: how digital influencers and algorithms negotiate influence on Instagram. New Media Soc. 21, 895–913. doi: 10.1177/1461444818815684

Deleuze, G., and Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis: MIT Press.

Hall, M. (2018). Disability, discourse and desire: analysing online talk by people with disabilities. Sexualities 21, 379–392.

Haraway, D. J. (2013). SF: Science Fiction, Speculative Fabulation, String Figures, So Far. Ada J. Gend. New Media Technol. 3, 1–18. doi: 10.7264/N3KH0K81

Haraway, D. J. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, NC. Manchester, UK Duke University Press.

Hickey-Moody, A. (2023). Faith stories: Sustaining meaning and community in troubling times. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Jungnickel, K. (2022). Speculative sewing: Researching, reconstructing, and re-imagining wearable technoscience. Soc. Stud. Sci. 53, 146–162. doi: 10.1177/03063127221119213

Jungnickel, K. (2024). Convertible, multiple and hidden: the inventive lives of women’s sport and activewear 1890–1940. Sociol. Rev. 72, 588–610. doi: 10.1177/00380261231153754

Kaur, H., and Saukko, P. (2022). Social access: role of digital media in social relations of young people with disabilities. New Media Soc. 24, 420–436. doi: 10.1177/14614448211063177

Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social: an introduction to actor-network-theory. New York: Oxford University Press.

Leonard, L., and Moulard-Leonard, V. (2022) "Henri Bergson", the Stanford Encyclopaedia of philosophy. Available online at: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2022/entries/bergson/ (Accessed December 3, 2024).

Manning, E. (2019). Experimenting immediation: collaboration and the politics of fabulation. Immediation 361, 26–39.

Miller, R. A. (2017). My voice is definitely strongest in online communities: students using social media for queer and disability identity-making. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 58, 509–525. doi: 10.1353/csd.2017.0040

Truman, S. E. (2021). Feminist speculations and the practice of research-creation: Writing pedagogies and intertextual affects. New York, NY: Routledge.

Willcox, M. (2023). “Bodies, belongings and becomings: An ethnography of feminist and queer Instagram artists,” in School of Media and Communication. Melbourne: RMIT University. doi: 10.25439/rmt.27597819

Willcox, M. (2025). Algorithmic agency and Instagram content moderation: #Iwanttoseenyome. Front. Cult. Commun. 9:1385869. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1385869

Yahya, C. (2024). Pink bits [Instagram account]. Available online at: https://www.instagram.com/pink_bits/

Keywords: digital media activism, feminism, philosophy, intersectionality, intersectionality analysis, digital art

Citation: Hickey-Moody AC and Willcox MG (2025) Feminist fabulation as refusal: Christine Yahya’s @pink_bits illustrating ‘bodies we are told to hide’. Front. Commun. 10:1542825. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1542825

Edited by:

Abdelmjid Kettioui, Moulay Ismail University, MoroccoReviewed by:

Martina Karels, St. Francis College, United StatesKaoutar Berrada, Moulay Ismail University, Morocco

Copyright © 2025 Hickey-Moody and Willcox. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marissa Grace Willcox, bS53aWxsY294QGdvbGQuYWMudWs=

Anna Catherine Hickey-Moody

Anna Catherine Hickey-Moody Marissa Grace Willcox

Marissa Grace Willcox