Abstract

Introduction:

Citizens’ disengagement in political participation has become a problem in many democracies due to its negative consequences on the equal and inclusive representation of the population. However, little is known about the extent to which online platforms have become a useful tool for sustaining political participation for the most underrepresented groups (e.g., young adults and women). The present study investigates gender differences in the association between online civic participation and political participation (i.e., interest, opinion formation, and involvement) among young adults in Italy, and the mediating role of affinity with political disengagement in these associations.

Methods:

Data were collected from 1,149 young adults (68.9% women), ranging in age from 18 to 35 years old (Mage = 25.61, SD = 4.41) by using an online survey.

Results:

Results of the multiple-group (women vs. men) path analysis model evidenced that online civic engagement is directly and indirectly (through affinity with political disengagement) positively associated with high political participation, with few gender differences. Online civic participation is directly related to the ease of forming opinions in politics only for women.

Discussion:

Overall, findings suggest some potential benefit of online tools in reducing the gender gap in women’s participation in the political debate. Such findings may help inform the development of future programs aimed at fostering political participation among young adults.

1 Introduction

Citizens’ political participation is crucial for the protection of resilient democracies (European Commission, 2020). Political participation is an umbrella term that encompasses different facets (Barrett and Pachi, 2019), such as (a) conventional political participation, which refers to direct involvement in political processes (e.g., electoral campaigns, involvement in a party, voting), (b) non-conventional political participation (e.g., signing petitions, protests), and (c) psychological engagement (e.g., forming opinions about political matters).

For effective protection and maintenance of democracy, previous evidence has emphasized the importance of inclusive participation (European Commission, 2024). This means that all citizens, regardless of their characteristics (e.g., age, gender), must have equal opportunities to engage in democratic processes, decision-making, and policy implementation. However, recent decades have been characterized by a growing climate of mistrust and polycrisis that affects citizens’ interest and involvement in political participation (European Parliament, 2021, 2022, 2025), which, in turn, undermines inclusive participation. In fact, beyond the conventional involvement or psychological engagement of citizens, some individuals can also disengage from political processes due to a lack of interest in political and civic actions (Barrett and Pachi, 2019).

The ‘polycrisis’ (Morin, 1993) impacts individual perceptions of economic insecurity and disillusionment with the political system. After the economic crisis of 2008, the effects of the polycrisis are being felt more in certain countries and among specific groups of citizens, such as young people and women. For instance, international reports evidence that youths ranging from 18 to 30 reported higher levels of dissatisfaction and mistrust for the way politics currently operates, compared with adults (European Parliament, 2025; OECD, 2022). Moreover, young people in Italy are more dissatisfied with the way democracy works in their country compared with the majority of other European Union (EU) countries (European Parliament, 2021, 2022, 2025). In this context, gender differences also emerged, with young men reporting a greater interest in politics than young women, believing that the EU should invest more in young people’s participation in politics and decision-making (M 20% vs. F 16%).

However, dissatisfaction with politics does not necessarily translate into less participation. For example, Amnå and Ekman (2014) evidenced that many young adults can be properly defined as “standby” youths, namely those young adults who remain observant, educate themselves on politics, and are ready and able to get involved when called upon. These youths are interested in political debate, have their own opinion on political matters, and, when needed, they participate in the conventional or unconventional political life. Previous studies, indeed, evidenced that youths tend to participate more through platforms that are alternative to the traditional political forms, such as digital activism (ASviS, 2024; Boulianne, 2015). Therefore, with the actual growing use of digital technologies, online platforms have become a useful tool for young adults’ political engagement, opinion expression, and information exchange (Eurostat, 2023), thereby enhancing young adults’ participation in the civic and political debate (Lelkes, 2020).

Although previous findings suggested the positive consequences of online activities on young adults’ political participation, another topic that needs further understanding is the extent to which gender differences, which are largely expressed in real-life political participation (Castanho Silva, 2025; UN Women, 2024), persist in the online context or whether online tools may be useful for reducing the gender gap in participatory actions in the political debate. Previous studies about this topic presented mixed results. A recent study by Stefani and colleagues (Stefani et al., 2021) conducted with a sample of 1792 youths living in Italy did not evidence gender differences in the way in which men and women use online tools for discussing social and political issues, share political content on social media, or join online social and political groups. Conversely, other studies evidenced that men are more likely to use the internet for political participation compared with women (Cicognani et al., 2012; Fox and Lawless, 2014), evidencing that the gender gap evidenced in offline political participation is also reflected in online engagement.

Given these mixed findings, the present study used a sample of young adults (aged 18 to 35 years) living in Italy for examining gender differences in the association between online civic participation and political participation, while also considering the role of individuals’ affinity with political disengagement (i.e., idea that politics is inherently divisive and that it is preferable to avoid any discussion with other citizens). In particular, based on Barrett and Pachi’s (2019) framework, we used three indicators that rely on three different facets of political participation, which regards conventional and non-conventional actions (i.e., political involvement), political interest (or disengagement), and psychological engagement (i.e., opinion).

1.1 Gender differences in political participation

The data of UN Women (2024) highlighted the persistently low political participation of women worldwide (only 23.3% of women ministers, mainly distributed in Europe, North America, Latin America, and the Caribbean, and in the field of human rights, social affairs, and gender equality). For example, women in leadership roles across the 193 UN Member States represent a rather low percentage: 21% of Prime Ministers, 26% of parliamentarians, and 34% of local government positions (Meo and Raffa, 2024). Moreover, there is a consistently higher voter turnout among men, compared with women, which has been a trend across all European countries during the last European Parliament election in 2024 (Popa et al., 2024). This trend may be linked to the still low representation of women in politics and decision-making processes (Castanho Silva, 2025). In line with this plausible hypothesis, the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE, 2024) evidenced that women’s representation in the European Parliament decreased in the last elections of 2024 compared to previous years. For example, although the national legislation of many European countries mandates the application of a gender quota, the proportion of women elected members at the European Parliament has still been lower. These findings underscore the need to expand opportunities to enhance women’s participation in politics and decision-making processes.

The topic of gender differences in political participation is multifaceted, involving overlapping aspects. Gender may be defined as “a system of symbolic meanings that creates social hierarchies based on perceived associations with masculine and feminine characteristics” (Sjoberg, 2010). As such, gender relations reveal an underlying hierarchy of power. Gender norms are politically significant and often instrumentally justify inequality between men and women. For instance, women first gained political rights, then civil rights such as freedom of movement and employment, and only later achieved legal equality. When political parties were first established, they primarily involved men, who often approached women’s issues with indifference or hostility (Zincone, 1992). The Global Gender Gap Report 2024 (WEF, 2024) shows that gender equality is far from being achieved, even in countries with advanced capitalism and mature democracies. The report examines four key dimensions (economic participation and opportunities, level of education, health and survival, and political emancipation), placing Italy 87th out of 146 countries, evidencing a drop of eight positions compared to the previous year.

From a historical perspective, the extension of political participation in contemporary democracies to the masses, the establishment of universal suffrage, and equality in voting were generally achieved in the early 20th century. However, in many cases, women obtained the right to vote many years later than men. For instance, the extension of universal suffrage for Italian women was obtained only after the Second World War, while Switzerland established universal suffrage only in 1971, making the latter the last European country that recognize the vote and the possibility of women being elected (i.e., 65 years after Finland, 51 years after Sweden, 48 years after Ireland, 42 years after Great Britain, and 26 years after France and Italy) (Rokkan, 1970). Although equal rights have been achieved, this does not necessarily translate into equal political participation. Democracy is not ‘an immobile state’ but ‘a process that can be more or less developed’ (Gallino, 1978). Therefore, it is possible to identify various degrees of democratic quality, in a tension between ideal and actual practice that can also be analyzed according to different factors, such as the type and level of political participation, the frequency/intensity, the decision-making processes in which one can actually participate, the objects that can be decided, and the proportion of participants (Gallino, 1978).

Gender studies emphasize the need to “de-neutralize the concept of power, recognizing a structural impediment on the part of access to political, economic, and social resources, and remembering that power is something deep and rooted in culture and in daily practices” (Meo and Raffa, 2024). The assumption of gender as an analytical category, in fact, underscores the imbalance of relations between genders, raising questions of power, rights, representation, voice, and democracy. Gender imbalance is framed as a political issue tied to asymmetries of power across different institutional domains: economic, political, cultural, and religious. In each of these, women remain largely underrepresented.

Considering conventional political participation, previous studies have shown gender differences even in established democracies. Different “structures of political opportunities” (Rush, 2014) characterize the political recruitment process. The primary structure concerns the eligible population and the formal criteria to be part of the electorate, whereas the secondary structure concerns the formal and informal factors (e.g., socio-economic, personal characteristics, resources) that are linked to the different opportunities for the aspirants. According to Rush (2014), a significant gender gap exists in the transition between the two structures, which extends to the tertiary opportunity structure concerning the candidates who manage to obtain office and the “elected.” Thus, the ‘gender glass ceiling’ has only partly cracked, with women continuing to occupy lower levels of formal participation, especially in standing for election and in being voted. Furthermore, we need to take into account that in some contexts female politicians encounter different forms of discrimination, ranging from the tendency to be assigned specific policy areas, such as care work, to maltreatment, exclusion, and verbal abuse (Alemdar et al., 2020).

Milbrath (1965) and Milbrath and Goel (1977) proposed the model of social centrality to explain, using a spatial metaphor of society, that people located ‘in the centre’ of society are more likely to participate in politics, whereas those on the periphery are less likely to engage in political action. Hence, those who participate more have also more status, economic, cultural, cognitive and relational resources, along with more psychological resources (e.g., self-esteem, sense of efficacy), enjoy more centrality and, finally, are placed at the higher-rank of the social ladder and aim at the preservation of their privileges. Conversely, Pizzorno (1966) emphasized the role of identity and belonging in participatory processes, suggesting that fewer privileges may rely on expressive mobilizing resources in a circular dynamic that increases the consciousness of being part of a group/organization through participation.

From a longitudinal perspective, Tuorto and Sartori (2021) analyzed the gender gap in the Italian political turnout from 1948 to 2018, evidencing two different phases. The first one points out the initial characteristics for a strong mobilization of female voters, whereas the second one evidences the reverse phenomenon in the last 30 years. From 1948 to the 1970s, women in Italy showed a high propensity to go to the polls, with percentages similar to those of men. The absence of the gender gap appeared surprising at this stage of early republican history because it contradicted the basic assumptions of the previous models (Lipset, 1960; Milbrath, 1965; Tuorto and Sartori, 2021). However, the lack of a gender gap in this period might appear related to the combined effect of marriage and the Church, which influenced the political socialization of women, especially in rural areas (Tuorto and Sartori, 2021). Paradoxically, when women begin to take on more social centrality (e.g., by increasing their access to employment), they participate less in politics and voting, reflecting, on the one hand, the distance and detachment from official politics and, on the other hand, a critical awareness and manifestation of protagonism. Given that participation is shaped by structural, situational, and socialization factors, women can no longer be viewed as a homogeneous or socially marginal group; instead, gender roles intersect with diverse socioeconomic resources and forms of social capital (Cuturi et al., 2000). Welch (1977) highlighted that education, life stage, and social norms influence women’s political engagement. For instance, analyzing the Italian Second Republic period, when women have a high educational qualification or attributes that foster a sense of efficacy, electoral data of the young age group (18–30 years) evidenced that women vote more than men (Tuorto and Sartori, 2021).

Although progress has been made in narrowing the gender gap in participation due to an increase in many factors (e.g., women socioeconomic conditions), significant cultural barriers remain. According to the Eurobarometer (European Commission, 2024), more than one-third of citizens hold stereotypical views about women’s political ambitions and interests. Nearly one in five believe that women do not have the necessary skills for politics. Furthermore, the belief that men are more ambitious than women has grown than in the past (+12 percentage points), and 35% of respondents agree that women are less interested than men in positions of responsibility in politics (European Commission, 2024).

Gender differences also manifest in unconventional participation. Political participation often begins with access to information, followed by emotional and affective involvement (invisible participation), and finally transitions into visible participation (i.e., observable actions) aimed at influencing the policy-makers’ selection and public decision-making (Ceccarini and Diamanti, 2018; García Santamaría and Pérez Castaños, 2022). For example, in Italy, among individuals aged 14 and older, 27.0% of women discuss politics at least once a week, compared to 44.7% of men. Likewise, 45.4% of women follow political news on a weekly basis, versus the 61.8% of men. Furthermore, 15.6% of women listen to political debates, compared to 22.1% of men (ISTAT, 2021). Overall, these data evidenced that gender gaps persist not only in institutional roles but also in everyday civic actions and access to political debate.

1.2 Online communication and political participation

In contemporary societies, citizens’ political participation is expressed by using both traditional offline and new online digital tools. The possibility of carrying out a number of political activities in the digital sphere has led to an evolution of the concept of political participation (Heger and Hoffmann, 2023; Toros and Toros, 2022; Öz Döm and Bingöl, 2021) and a growing body of research on this topic.

Although widely definitions and empirical operationalizations have been made (Heger and Hoffmann, 2021; Vochocová et al., 2016), online political participation broadly encompasses several facets of participation, from e-voting and engagement in the electoral process through online platforms to online behavior aimed at sharing contents about politics or joining online political discussions (Heger and Hoffmann, 2021).

Scholars’ interest in online political participation is largely motivated by its potential to facilitate political engagement and contribute to a more egalitarian access to democracy (Heger and Hoffmann, 2021). Among different studies on online political participation, those on social media prompted divergent perspectives (Ahmed and Madrid-Morales, 2020). From the “mobilization scholar” perspective, social media may mitigate the phenomena of political inequalities by offering more opportunities to empower disengaged groups. Conversely, the “reinforcement scholars” perspective emphasizes that social media are a replication of offline spaces, thereby sustaining or even exacerbating existing offline disparities.

Although limited (Ahmed and Madrid-Morales, 2020; Vochocová et al., 2016), previous literature on the positive effect that online political participation might play in reducing gender inequalities showed mixed findings (Yolmo and Basnett, 2024). As observed by Heger and Hoffmann (2023) and Ahmed and Madrid-Morales (2020), some studies indicate that women demonstrate a lower level of engagement in online political activities (Bode, 2016; Cicognani et al., 2012; Heger and Hoffmann, 2021; Lutz, 2010; Strandberg, 2013; Theocharis and van Deth, 2018; Vochocová et al., 2016), while others have yielded similar levels of online political participation between men and women (Gil de Zúñiga et al., 2015; Stefani et al., 2021; Vesnic-Alujevic, 2012) or have found that the gender gap is decreasing in specific conditions, such as in specialized online platforms or topics (Bode, 2016; Lilleker et al., 2021; Oser et al., 2012) or in specific political and cultural contexts (Feezell, 2016; Oser et al., 2012). Thus, literature reflects both optimistic and pessimistic perspectives. The former evidenced the potential of online tools to offer greater accessibility and lower costs (e.g., economic and time), which may help overcome structural and cultural barriers for women’s participation (Xenos et al., 2014). The latter suggested that online tools have not fulfilled the possibility of reducing the gender gap in political participation. For instance, Heger and Hoffmann (2021) argued that offline political participation gender gap has merely shifted into a “digital gender divide” (p. 228). Indeed, they stress that “despite initial hopes for more egalitarian access to democracy, research has shown that political participation on the Internet remains as stratified as its offline counterpart. Gender is among the characteristics affecting an individual’s degree of political engagement on the Internet—even when controlling for socioeconomic status” (ivi, p. 226). In line with this pessimistic perspective, Abendschön and García-Albacete (2021) also evidenced that the gender gap in online political engagement is not simply a reflection of the traditional gender gap in offline political discussion activities, but it is a new gap grounded in a combination of the specifics of social media environments and gendered political socialization.

Given that the gender gap does not manifest uniformly across all forms of online engagement, it is crucial to take into account the interplay of gender with structural, institutional, cultural, social, economic, and intraindividual factors (Heger and Hoffmann, 2021; Vochocová et al., 2016). For example, previous studies showed that women tend to be less active in high-visibility online political participation (e.g., posting political comments) compared to men, while no gender differences emerged in low-visibility online actions (e.g., following and liking or sharing posts) (Abendschön and García-Albacete, 2021; Bode, 2016; Steinberg, 2015; Vochocová et al., 2016). This pattern has also been found in a recent study by Lilleker et al. (2021), using survey data from France, the UK, and the US, which showed small gender differences in many online political activities such as, searching or seeing information; sharing posts or contents about politics; commenting on political content. However, Lilleker et al. (2021) evidenced that women are more likely to participate actively in political discussion (e.g., commenting) when they perceive a higher sense of competence. Though, even in that case, women are likely to avoid the wider online environment to express their opinions, preferring Facebook, which seems to offer a perceived sense of safety and support due to its basis in close relationships. Moreover, gender differences emerged regarding the tone of communication, with men more likely to post negative comments than women (Vochocová et al., 2016).

Overall, these gender differences in the online realm may reflect gender socialization processes (Abendschön and García-Albacete, 2021; Bode, 2016). As pointed out by Bode (2016), girls and women are generally socialized to prioritize social relationships, to be nice and polite, and to regulate their emotions to protect the feelings of others. Consequently, women may avoid posting political content in order to preserve their social media relationships.

Further research exploring online political participation from a gendered perspective is necessary in order to understand contemporary gender political inequalities, to identify both facilitators of and obstacles to women’s political participation (Heger and Hoffmann, 2021), and to contribute to a more balanced public political debate.

1.3 The present study

The present study aims to examine gender differences in the association between online civic participation and three facets of political participation (i.e., interest, opinion formation, and involvement) among young adults (aged 18–35 years) in Italy, while also considering the perception of mistrust about politics and political participation. In detail, the aim of the present study was threefold. First, to understand whether our data reflect previous findings on a greater participation of men compared with women in politics, we examined whether women and men differ in the reported levels of study variables. Second, we explored whether women and men differ in the associations between online tools for civic participation and their reported interest and involvement in politics, and perceptions about the ease of forming an opinion about politics. Third, we investigated the mediating role of affinity with political disengagement in the association between online civic participation and political participation among women and men.

Thus, the present study tested a set of exploratory pathways regarding both direct and indirect relations between online civic engagement and political participation to offer a more nuanced comprehension of how online political tools relate to political participation among women and men youths in Italy.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Participants

The sample of the present study included 1,149 young adults (68.9% women) living in Italy, ranging in age from 18 to 35 years old (Mage = 25.61, SD = 4.41). Among the participants, 6.3% were high school students, 42.5% were university students, 7.8% were part-time workers, 30.7% were full-time workers, 4.3% were unemployed, and 8.4% reported a mixed occupation (e.g., university student and part-time worker). Regarding educational levels, 7.5% had a middle school diploma, 34.7% had a high school degree, 32.6% had a bachelor’s degree, 15.4% had a master’s degree, and 9.8% had a higher educational degree (e.g., Ph. D). Additionally, 23.5% of participants indicated low annual income, 61.7% indicated a medium annual income, and 14.8% reported a high annual income.

2.2 Procedure

The present study was part of a larger research project with a cross-sectional design aimed at investigating the protective and risk individual factors involved in facing the COVID-19 pandemic (Cirimele et al., 2022; Remondi et al., 2022; Thartori et al., 2021). The research project received ethical approval by the local Institutional Review Board at the Department of Psychology at Sapienza University of Rome. Participants were involved in the study using a snowball recruiting procedure (Fricker, 2008) and had to meet three inclusion criteria: (1) aged 18 to 35 years, (2) provide informed consent to participate, and (3) understanding of spoken and written Italian. Data collection was carried out from December 2020 to March 2021 through the online platform Qualtrics. An anonymous link has been circulated among participants who completed the online survey after providing informed consent. The completion of the survey took approximately 20 min.

2.3 Instruments

2.3.1 Sociodemographic variables

Ad-hoc questions were used to collect information about participants’ gender, age, educational level, and income.

2.3.2 Affinity with political disengagement

Individuals’ affinity with political disengagement was measured by developing one item adapted from the Portrait Values Questionnaire (Schwartz, 2007). Participants were asked to indicate how much the following description: “He/She believes that politics is divisive and that it is better not to discuss it with other people.” was similar or differ from them on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Not like me at all) to 6 (Very much like me).

2.3.3 Online civic participation

Participants’ online civic participation was assessed by adopting three items from the dimension Civic Participation of the Global Kids Online Child Questionnaire.1 Participants reported how often they have done a series of activities online during the past month (i.e., “I looked for resources or events about my local neighborhood”; “I looked for news online”; “I discussed political or social problems with other people online”), ranging from 1 (Never) to 6 (Almost all the time).

2.3.4 Political participation

Participants’ political participation was assessed by using three different items covering political interest (“How interested do you personally consider yourself in politics?”), political opinion (“How difficult do you personally find it to form an opinion on political issues?”), and political involvement: (“How involved do you personally feel in political affairs?”) on a 5-point Likert scale.

2.4 Data analytic approach

Preliminary, a series of descriptive analyses (means, standard deviations, skewness, kurtosis) were conducted among the variables of interest using SPSS 23.0. Moreover, Pearson’s r correlations were computed for a preliminary understanding of the associations between the variables of interest. Second, a series of univariate Analyses of Variance (ANOVA) were computed to examine differences among women and men in the reported levels of online civic participation, affinity with political disengagement, and the three dimensions of political participation (i.e., political interest, political opinion, and political involvement). Third, we implemented multiple group (men vs. women) path analysis models within the Structural Equation Modeling framework using the software Mplus 8.11 (Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2016). To test similarity or differences among men and women in the hypothesized associations, we compared a constrained model, in which all regression paths were constrained to be equal across groups, with an unconstrained model that freely estimated all paths. The comparison between the constrained and unconstrained model has been conducted using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC; Akaike, 1973), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and Sample-Size Adjusted BIC (SABIC; Schwarz, 1978), with lower values indicating greater model plausibility (Wang and Wang, 2019).

To test the mediation effect of affinity with political disengagement in the association between online civic participation and the three dimensions of political participation (i.e., political interest, political opinion, and political involvement), we used the model indirect function in Mplus 8.11, with the bootstrapping method with 5,000 replications and 95% Confidence Interval (CI). Using this approach, a mediation effect is considered significant when the 95% confidence interval does not include zero (Bollen and Stine, 1990; Lockwood and MacKinnon, 1998).

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive statistics

As shown in Table 1, all study variables were normally distributed, with skewness and kurtosis values below the cut-off of |1|. All Pearson’s r correlation resulted statistically significant. Specifically, online civic participation showed small positive correlations with the three dimensions of political participation, evidencing that more frequent use of online platforms for political purpose was associated with greater interest, involvement, and ease in forming opinion in politics among young adults. In contrast, affinity with political disengagement were small-to-moderate negatively correlated with political participation, suggesting that the more young adults perceive political divisiveness, the less likely they are to be interest or involved in political matters, and the more difficult they hold opinion about political issues.

Table 1

| Variables | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Online Civic Participation | 3.02 | 0.89 | 0.66 | 0.52 | - | ||||

| 2. Affinity with Political Disengagement | 3.14 | 1.38 | 0.16 | −0.62 | −0.13** | - | |||

| 3. Political Interest | 2.54 | 1.08 | 0.62 | −0.18 | 0.26** | −0.37** | - | ||

| 4. Political Opinion | 2.60 | 1.01 | 0.22 | −0.37 | 0.14** | −0.20** | 0.52** | - | |

| 5. Political Involvement | 2.33 | 1.08 | 0.77 | 0.14 | 0.22** | −0.30** | 0.63** | 0.41** | - |

Descriptive statistics and correlations for study variables.

p < 0.001.

3.2 Mean differences between women and men

As reported in Table 2, Fisher’s F test revealed significant mean differences between women and men on all variables, except for the affinity with political disengagement. In detail, men reported higher levels of online civic participation, political interest, political opinion, and political involvement than women.

Table 2

| Measures | Women | Men | F | df | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| 1. Online Civic Participation | 2.95 | 0.89 | 3.17 | 0.88 | 11.58 | 1, 838 | <0.01 |

| 2. Affinity with Political Disengagement | 3.18 | 1.37 | 3.03 | 1.42 | 2.62 | 1, 1,029 | 0.106 |

| 3. Political Interest | 2.34 | 0.98 | 2.94 | 1.16 | 60.61 | 1, 831 | <0.001 |

| 4. Political Opinion | 2.39 | 0.98 | 3.01 | 0.93 | 76.57 | 1, 828 | <0.001 |

| 5. Political Involvement | 2.22 | 1.02 | 2.54 | 1.14 | 15.85 | 1, 830 | <0.001 |

Mean differences between women and men in study variables.

3.3 Results of the multiple group path analysis

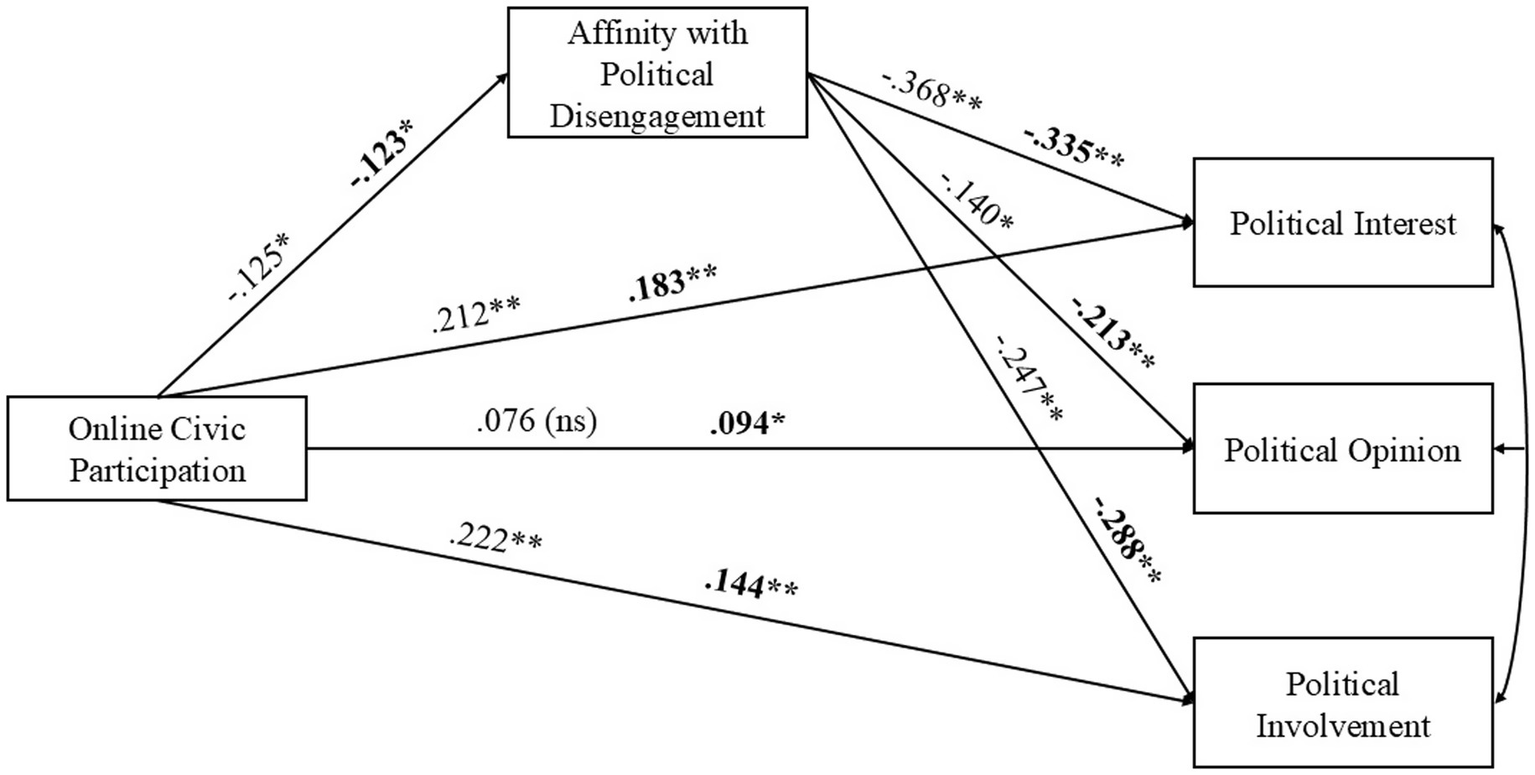

To examine the associations between online civic participation, affinity with political disengagement, and political participation (i.e., interest, opinion, involvement) among men and women, a multiple-group path analysis model has been implemented. Given the increase in the AIC, BIC, and SABIC indexes, results showed that the free model (AIC = 9244.14; BIC = 9414.45; SABIC = 9300.13) was preferable compared with the constrained model (AIC = 12183.51; BIC = 12326.86; SABIC = 12237.88). As shown in Figure 1, results evidenced similar associations among study variables across women and men. In particular, online civic participation was positively associated with all three facets of political participation, except for the political opinion among men, which was not significant. Moreover, online political participation was negatively associated with affinity with political disengagement, indicating that both women and men with a higher tendency to use online tools for civic participation also reported lower negative beliefs about politics and political debate. Finally, affinity with political disengagement was negatively associated with the three aspects of political participation among women and men.

Figure 1

Graphical representation of multiple group path analysis results. ns represent not significant path; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.001; Values in bold represent standardized regression coefficients for women; In sake of simplicity, covariations between political interest, opinion, and involvement has been tested but not reported.

3.4 Results of the indirect effects

We explored the mediation role of affinity with political disengagement in the associations between online political participation and the three dimensions of political participation (online political participation → affinity with political disengagement → political interest, opinion, and involvement) in women and men. Results indicated a positive indirect effect of online political participation on political participation, even though the affinity with political disengagement undermines political participation. Specifically, online political participation was negatively associated with affinity with political disengagement that, in turn, was negatively associated with the three dimensions of political participation. However, the positive indirect effect among both Women (W) and Men (M) on political interest (abW = 0.05, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.01, 0.08] and abM = 0.06, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [0.01, 0.13]), opinion (abW = 0.03, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.01, 0.06] and abM = 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.001, 0.06]), and involvement (abW = 0.04, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [0.01, 0.08] and abM = 0.04, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [0.01, 0.09]) suggested that online political participation is positively associated with political participation facets also by potentially mitigating the negative effect of the affinity with the idea that politics is inherently divisive and, as such increase political disengagement.

4 Discussion

The present study examined whether the use of online tools for political participation was significantly related to dimensions of political participation, such as the degree of interest and involvement in politics and the ease of forming opinions about politics among young adults (aged 18–35 years) in Italy, also beyond the affinity with political disengagement. Based on the markedly different historical roots and conditions of women and men in politics, we also examined gender differences in the abovementioned associations. Overall, results highlighted the direct and indirect positive association of online tools with political participation, as well as a few differences between women and men.

Regarding our first aim, we found that men reported higher levels of online political participation, political interest, and involvement, and ease of forming opinions about politics compared with women. This pattern is consistent with previous studies (Cicognani et al., 2012; Fox and Lawless, 2014) and international reports (European Commission, 2024; European Parliament, 2022), evidencing that, even in contemporary democratic Italian society, men tend to participate more in the political debate both offline and online.

Regarding our second aim, we found that online political participation is associated with higher political interest and involvement among both women and men. Thus, young adults who frequently used digital tools to access news, discover resources or events in their neighborhood, and discuss political or social issues also reported a greater interest and involvement in politics. These results reflect previous findings suggesting that the digital realm may offer opportunities and alternative platforms for supporting young people in exercising their capacity to engage in the political debate. However, the direct association of online political participation with the ease of forming opinions about politics was statistically significant for women and not for men. Women who reported higher levels of online political participation also perceive it easier to create their own opinions about political issues. Despite a lack of additional covariates (e.g., feminism) in our analysis that undermine the in-depth exploration of the political participation phenomena, one plausible explanation for this difference can be traced. Feminism paradigms, which highlighted the importance of empowering women in political engagement (Turner and Maschi, 2015), suggested that digital platforms may offer women with an empowering environment for political expression and political identity formation, while also providing alternative spaces beyond the traditionally male-dominated political structures (Heger and Hoffmann, 2021). Overall, we posit that perhaps online civic participation offers an autonomous and intimate space for deepening knowledge, comparing opinions, thereby facilitating the formation of one’s own opinion, without being exposed to high-visibility actions that might be in contrast with women’s general political socialization (Bode, 2016). Thus, online civic participation might be an effective way to support women’s interest, involvement, and perceived capabilities in politics.

As regards the third aim, online civic participation was also indirectly associated with the three facets of political participation, suppressing the negative mediating effect of affinity with the idea that politics is inherently divisive. Although affinity with political disengagement was negatively associated with political participation, supporting the detrimental effect of young adults’ mistrust and dissatisfaction with politics on their participation (European Parliament, 2021, 2022, 2025), our results highlighted a positive indirect effect from online political participation to political participation facets. Thus, the online realm may enable young people to participate in political dialogue. According to Amnå and Ekman (2014), it is plausible that, through the use of digital tools for civic participation, youths express their interest and involvement in politics, beyond the affinity with political disengagement.

This study highlighted the cross-sectional association of young adults’ online civic participation and three facets of political participation (i.e., interest, opinion, and involvement) among young adults (aged 18–25 years) in Italy. We examine these associations by considering the crucial role of gender in these associations and individuals’ affinity with political disengagement. In doing so, we used a large sample of young adults living in Italy, offering additional findings to an understudied topic in the Italian context.

Although this study has many strengths, we recognize some limitations that should be considered. First, the cross-sectional design did not allow us to interpret long-term or hypothesizing causal effects between the considered variables. Second, many other proximal (e.g., family socialitazion to politics) or distal (e.g., broad national communication) can influence these associations and were not considered in the present study. In fact, education, income, political knowledge, time spent online, feminism, political self-efficacy, personality traits has extensively demonstrated their role in boosting the citizens’ political and participation (Barrett and Pachi, 2019; Heger and Hoffmann, 2021; Zhang, 2022). Thus, we encourage future studies to explore this topic using a longitudinal design and considering additional involving factors. Third, the present study relied on one item to assess the affinity with political disengagement, which reflect an overall individuals’ perception of political divisiveness. Although previous findings evidenced that single-item may be capable to capture individuals’ attitudes (e.g., Ang and Eisend, 2018), our measure may be limited in the representation of a multidimensional meaning of political disengagement (e.g., lose of faith in the political institutions, lack of political knowledge; Zhang, 2022). Thus, future studies should consider to use a multiple-item measure to capture diverse facets of the political disengagement phenomena. Finally, although we used a large sample size, the use of the non-probabilistic snowball recruiting method strongly affected the generalizability of our results to the entire population (Ting et al., 2025). For example, as reported by the Italian Institute of Statistics (ISTAT, 2021), women in Italy between 18 and 35 years correspond to approximately the 49% of the total population. Therefore, the over representation of women in our sample may affect its representativeness.

5 Conclusion

The present findings advance understanding of the relations between online civic participation and political participation among young adults in the Italian context.

Findings yielded similar results to previous studies that highlight the positive consequences of digital tools for broad and political participation among young adults. Importantly, we evidenced that the online tools may foster opportunities for young women, who are largely underrepresented in conventional and unconventional forms of political participation, to increase their involvement in the political debate, thereby enhancing future equal representation. Moreover, we encourage future studies and interventions to consider the use of digital tools as a plausible democratic and autonomous space that may sustain specific groups of citizens in participating in political debate and civic actions.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional Review Board at the Department of Psychology at Sapienza University of Rome. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

FC: Formal analysis, Project administration, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Conceptualization. MM: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. GA: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. NÇ: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. CZ: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The present publication was funded by the EUROSTART 2024 (D.R. n. 7686/2024, Università degli studi di Palermo, Italy) project fund -Grant number: PRJ-1966 -GRASP. Gender Radicalisation AwarenesS and Prevention of risk: interdisciplinary participatory comparative research -CUP: B79J21038330001 (Principal Investigator: Prof. Marilena Macaluso, Dipartimento Culture e Società, Università degli studi di Palermo, Palermo, Italy).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

1

AbendschönS.García-AlbaceteG. (2021). It’s a man’s (online) world. Personality traits and the gender gap in online political discussion. Inf. Commun. Soc.24, 2054–2074. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2021.1962944

2

AhmedS.Madrid-MoralesD. (2020). Is it still a man’s world? Social media news use and gender inequality in online political engagement. Inf. Commun. Soc.24, 381–399. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2020.1851387

3

AlemdarZ.AkgülM.KöksalS.UysalG. (2020). Women’s political participation in Turkey: Female members of district municipal councils.

4

AkaikeH. (1973). Maximum likelihood identification of Gaussian autoregressive moving average models. Biometrika, 60, 255–265. doi: 10.1093/biomet/60.2.255

5

AmnåE.EkmanJ. (2014). Standby citizens: diverse faces of political passivity. Eur. Polit. Sci. Rev.6, 261–281. doi: 10.1017/S175577391300009X

6

AngL.EisendM. (2018). Single versus multiple measurement of attitudes. J. Advert. Res.58, 218–227. doi: 10.2501/JAR-2017-001

7

ASviS. (2024). Coltivare ora il nostro futuro. L’Italia e gli Obiettivi di Sviluppo Sostenibile. Italy.

8

BarrettM.PachiD. (2019). Youth civic and political engagement. 1st Edn. London: Routledge.

9

BodeL. (2016). Closing the gap: gender parity in political engagement on social media. Inf. Commun. Soc.20, 587–603. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2016.1202302

10

BollenK. A.StineR. (1990). Direct and Indirect Effects: Classical and Bootstrap Estimates of Variability. Sociological Methodology, 20, 115–140.

11

BoulianneS. (2015). Social media use and participation: a meta-analysis of current research. Inf. Commun. Soc.18, 524–538. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2015.1008542

12

Castanho SilvaB. (2025). No votes for old men: leaders' age and youth turnout in comparative perspective. Eur J Polit Res64, 276–295. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12694

13

CeccariniL.DiamantiI. (2018). Tra politica e società. Fondamenti, trasformazioni e prospettive. Bologna: il Mulino.

14

CicognaniE.ZaniB.FournierB.GavrayC.BornM. (2012). Gender differences in youths’ political engagement and participation. The role of parents and of adolescents’ social and civic participation. J. Adolesc.35, 561–576. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.10.002

15

CirimeleF.PastorelliC.FaviniA.RemondiC.ZuffianoA.BasiliE.et al. (2022). Facing the pandemic in Italy: personality profiles and their associations with adaptive and maladaptive outcomes. Front. Psychol.13:805740. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.805740

16

CuturiV.SampugnaroR.TomaselliV. (2000). L'elettore instabile: voto/non voto Milano Franco Angeli.

17

EIGE. (2024). Gender Equality Index 2024 – Sustaining momentum on a fragile path. Luxembourg.

18

European Commission. (2020). European democracy action plan: Making EU democracies stronger. Brussels: Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/ga/ip_20_2250 (Accessed April 9, 2025).

19

European Commission. (2024). Gender Stereotypes. Special Eurobarometer 545.Brussels.

20

European Parliament. (2021). EP Autumn 2021 Survey: Defending Democracy | Empowering Citizens. Brussels.

21

European Parliament. (2022).Youth and democracy in the European year of youth. Brussels.

22

European Parliament. (2025). Eurobarometer. Winter survey. Brussels.

23

Eurostat (2023). 96% of young people in the EU uses the internet daily

24

FeezellJ. T. (2016). Predicting online political participation: the importance of selection bias and selective exposure in the online setting. Polit. Res. Q.69, 495–509. doi: 10.1177/1065912916652503

25

FoxR. L.LawlessJ. L. (2014). Uncovering the origins of the gender gap in political ambition. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev.108, 499–519. doi: 10.1017/S0003055414000227

26

FrickerR. D. J. (2008). Sampling methods for online surveys, in fielding. The SAGE Handbook of Online Research Methods. 2nd Edn. Eds. N. G., Lee, R. M. and Blank, G. Fitzgerald (London: SAGE Publications), 162–183.

27

GallinoL. (1978). Dizionario di Sociologia. Turin: UTET.

28

García SantamaríaS.Pérez CastañosS. (2022). Diferencias de género en participación política de la juventud de la Unión Europea. Gender differences in European Union’s youth political participation, 17.

29

Gil de ZúñigaH.Garcia-PerdomoV.McGregorS. C. (2015). What is second screening? Exploring motivations of second screen use and its effect on online political participation. J. Commun.65, 793–815. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12174

30

HegerK.HoffmannC. P. (2021). Feminism! What is it good for? The role of feminism and political self-efficacy in women’s online political participation. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev.39, 226–244. doi: 10.1177/0894439319865909

31

HegerK.HoffmannC. P. (2023). Feminist women’s online political participation: empowerment through feminist political attitudes or feminist identity?J. Inform. Tech. Polit.20, 393–406. doi: 10.1080/19331681.2022.2119320

32

ISTAT (2021). Principali caratteristiche strutturali della popolazione. Italy: Istituto Nazionale di Statistica.

33

LelkesY. (2020). A bigger pie: the effects of high-speed internet on political behavior. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun.25, 199–216. doi: 10.1093/jcmc/zmaa002

34

LillekerD.KarolinaK.-M.BimberB. (2021). Women learn while men talk?: revisiting gender differences in political engagement in online environments. Inf. Commun. Soc.24, 2037–2053. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2021.1961005

35

LipsetS. M. (1960). Political man: The social bases of politics. Garden City, New York: Doubleday.

36

LockwoodC. M.MacKinnonD. P. (1998). Proceedings of the Twenty-Third Annual SAS Users Group International Conference.

37

LutzR. (2010). Das Mandat der Sozialen ArbeitSpringer-Verlag.

38

MeoM.RaffaV. (2024). “Gender rights and opposition to populism” in The rule of law in the EU: Challenges, actors and strategies. eds. AntoniolliL.RuzzaC. (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 175–190.

39

MilbrathL. (1965). Political participation: How and why do people get involved in politics?Boston: Rand McNally College Publishing Company.

40

MilbrathL. W.GoelM. L. (1977). Political participation: How and why do people get involved in politics?2nd Edn. Boston: Rand McNally College Publishing Company.

41

MorinE. (1993). For a crisiology1. Indust. Environ. Crisis Quart.7, 5–21. doi: 10.1177/108602669300700102

42

MuthénL. K.MuthénB. O. (1998–2016). Mplus user’s guide. Muthén & Muthén.

43

OECD (2022). Building Trust to Reinforce Democracy: Main Findings from the 2021 OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions. Paris: Publishing OECD.

44

OserJ.HoogheM.MarienS. (2012). Is online participation distinct from offline participation? A latent class analysis of participation types and their stratification. Polit. Res. Q.66, 91–101. doi: 10.1177/1065912912436695

45

Öz DömÖ.BingölY. (2021). Political participation of youth in Turkey: social media as a motivation. İnsan ve Toplum Bilimleri Araştırmaları Dergisi10, 605–625. doi: 10.15869/itobiad.804311

46

PizzornoA. (1966). Introduzione allo studio della partecipazione politica. Quad. Sociol.79, 17–60.

47

PopaS. A.HoboltS. B.van der BrugW.KatsanidouA.GattermannK.SoraceM.et al. (2024). European Parliament Election Study 2024, Voter Study. GESIS, Cologne. ZA8868 Data file Version 1.0.0.

48

RemondiC.CirimeleF.PastorelliC.GerbinoM.GregoriF.PlataM. G.et al. (2022). Conspiracy beliefs, regulatory self-efficacy and compliance with COVID-19 health-related behaviors: the mediating role of moral disengagement. Curr. Res. Ecol. Soc. Psychol.3:100069. doi: 10.1016/j.cresp.2022.100069

49

RokkanS. (1970). Citizens, election, parties. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

50

RushM. (2014). Politics and society. An introduction to political sociology. London: Routledge.

51

SchwartzS. (2007). Value Orientations: Measurement, Antecedents and Consequences Across Nations. In Measuring Attitudes Cross-Nationally. Eds. R. Jowell, C. Roberts and R. Fitzgerald (London: SAGE Publications) 169–203.

52

SchwarzG. (1978). Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann. Stat.6, 461–464. doi: 10.1214/aos/1176344136

53

SjobergL. (2010). Introduction, in Routledge (ed), gender and international security: feminist perspectives. pp. 1-14.

54

StefaniS.PratiG.TzankovaI.RicciE.AlbanesiC.CicognaniE. (2021). Gender differences in civic and political engagement and participation among Italian young people. Soc. Psychol. Bullet.16, 1–25. doi: 10.32872/spb.3887

55

SteinbergA. (2015). Exploring web 2.0 political engagement: is new technology reducing the biases of political participation?Elect. Stud.39, 102–116. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2015.05.003

56

StrandbergK. (2013). A social media revolution or just a case of history repeating itself? The use of social media in the 2011 Finnish parliamentary elections. New Media Soc.15, 1329–1347. doi: 10.1177/1461444812470612

57

ThartoriE.PastorelliC.CirimeleF.RemondiC.GerbinoM.BasiliE.et al. (2021). Exploring the protective function of positivity and regulatory emotional self-efficacy in time of pandemic COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health18:3171. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182413171

58

TheocharisY.van DethJ. W. (2018). The continuous expansion of citizen participation: a new taxonomy. Eur. Polit. Sci. Rev.10, 139–163. doi: 10.1017/S1755773916000230

59

TingH.MemonM. A.ThurasamyR.CheahJ. H. (2025). Snowball sampling: a review and guidelines for survey research. Asian J. Bus. Res.15, 1–15. doi: 10.14707/ajbr.250186

60

TorosS.TorosE. (2022). Social media use and political participation: the Turkish case. Turk. Stud.23, 450–473. doi: 10.1080/14683849.2021.2023319

61

TuortoD.SartoriL. (2021). Quale genere di astensionismo? La partecipazione elettorale delle donne in Italia nel periodo 1948-2018. SocietàMutamentoPolitica11, 11–22. doi: 10.13128/smp-12624

62

TurnerS. G.MaschiT. M. (2015). Feminist and empowerment theory and social work practice. J. Soc. Work. Pract.29, 151–162. doi: 10.1080/02650533.2014.941282

63

UN Women. (2024). Women’s leadership and political participation.

64

Vesnic-AlujevicL. (2012). Political participation and web 2.0 in Europe: a case study of Facebook. Public Relat. Rev.38, 466–470. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2012.01.010

65

VochocováL.VáclavŠ.MazákJ. (2016). Good girls don't comment on politics? Gendered character of online political participation in the Czech Republic. Inf. Commun. Soc.19, 1321–1339. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2015.1088881

66

WangJ.WangX. (2019). Structural Equation Modeling: Applications Using Mplus, 2nd Edn. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

67

WEF. (2024). Global Gender Gap 2024. Switzerland.

68

WelchS. (1977). Women as political animals? A test of some explanations for male-female political participation differences. Am. J. Polit. Sci.21, 711–730. doi: 10.2307/2110733

69

XenosM.AriadneV.LoaderB. D. (2014). The great equalizer? Patterns of social media use and youth political engagement in three advanced democracies. Inf. Commun. Soc.17, 151–167. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2013.871318

70

YolmoU. T. L.BasnettP. (2024). Gender perspectives on political awareness and participation in the digital era. Media Watch15, 367–385. doi: 10.1177/09760911241256323

71

ZhangW. (2022). Political disengagement among youth: a comparison between 2011 and 2020. Front. Psychol.13, 13–2022. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.809432

72

ZinconeG. (1992). Da sudditi a cittadini. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Summary

Keywords

online civic participation, political interest, political opinion, political involvement, gender difference, mistrust, young adults

Citation

Cirimele F, Macaluso M, Agolino G, Çabuk Kaya N and Zappulla C (2025) Gender differences in the use of online platforms for political participation. Front. Commun. 10:1625965. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1625965

Received

09 May 2025

Accepted

24 July 2025

Published

07 August 2025

Volume

10 - 2025

Edited by

Elsa Costa E. Silva, University of Minho, Portugal

Reviewed by

Inês Amaral, University of Coimbra, Portugal

Fabio Ribeiro, University of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro, Portugal

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Cirimele, Macaluso, Agolino, Çabuk Kaya and Zappulla.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Flavia Cirimele, flavia.cirimele@unipa.it

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.