- Department for German as a Second and Foreign Language, Institute for German Linguistics, Philipps-University Marburg, Marburg, Germany

In foreign language learning (FLL) advisory interactions, emotional responsiveness emerges as a central dimension, sustained through regulatory practices such as reappraisal, relabeling, self-disclosures, and simulated self-talk. Despite their importance, little is known about how novices without training in emotional regulation respond to learners' explicit negative emotional displays in contexts where emotions are backgrounded, generating tension in emotional reciprocity. This study examines the interactions of 28 pre-service teachers acting as FLL advisors for 28 international students in a service-learning context across two semesters. Data include audio recordings of 14 ad hoc advisory sessions and 14 seven-session counseling cycles, supplemented by team meetings. Using an interactional-linguistic approach, the study examines the linguistic resources that underlie emotional responsiveness and regulatory practices, focusing on their interplay and adaptive use across various interactions. Findings reveal a cluster of emotional-regulative practices along a continuum of increasing explicitness, complexity, and multidimensionality: emotional-regulative noticing, positive reorienting reappraisal in follow-up questions, emotionally supportive co-reasoning, transformative co-reasoning, postponed regulatory processing, extended meta-emotional episodes, and orchestrating multidimensional reappraisal in joint reasoning. All practices involve unpacking emotional displays into situated, narratively structured co-experiences, making them processable within the interactional interface of co-reasoning. Emotional responsiveness evolves dynamically across the counseling cycle, showing increased explicitness, functional recalibration, and argumentative integration, while context-dependent variations reflect advisors' adaptivity to the interactional history. The study highlights the need for systematic conceptualization of emotional responsiveness as a professional competency, providing a foundation for research on adaptive interpersonal regulation and emotionally responsive advising in FLL.

1 Introduction

The emotional dimension plays a central role in cognitive and motivational processes in learning, shaping the allocation of cognitive resources, depth of processing, problem-solving, and higher-order thinking (Hanin et al., 2021), as well as learning engagement, persistence, self-efficacy, and learning identity, including the adaptation of self-regulated learning strategies (Zhoc et al., 2020; Li and Lajoie, 2022). Fostering emotional literacy and self-regulation constitutes an important pedagogical objective (Mendonça, 2024), which is especially important in the intercultural context of foreign language learning (FLL) due to the specific emotional challenges inherent in the FLL process, as well as differences in emotion displays, interpretative frameworks, and normative expectations across languages and cultures (Boiger and Mesquita, 2012; Parkinson, 2023). The emotional responsiveness of significant others in learning contexts is crucial for supporting emo-cognitive equilibration and co-constructing positive emotional orientations for joint activities. However, this remains insufficiently integrated in instructional designs, reflected in teaching practices, while dedicated attention and space for engaging with learning-related emotions are often lacking. As a result, many emotional aspects remain latent and delegated to learners' self-regulation, functioning as “hidden items” and barriers that can significantly impede the learning process. Although such issues are supposed to be explicitly addressed in language learning counseling contexts, counselors often refrain from deeply engaging with them—frequently due to misconceptions regarding their self-perceived role as mere process facilitators rather than being responsible for addressing emotional dimensions, as well as the tendency to equate work on emotional aspects with psychotherapy—or simply because of insufficient training in this domain (Lazovic, 2025a). Amidst the tension between primary advisory goals and the emotional dimension, often regarded as “secondary or motivational,” a central challenge lies in integrating backgrounded, or inaccessible, emotional processes with advisory goals without compromising the primary focus. Practitioners face challenges regarding both the recognition and interpretation of emotions within the learner's specific learning system and the coherent, recipient-oriented deployment of regulatory resources and strategies. These must accommodate variable practices that enable functional, co-constructive processing, thereby supporting self-regulation and adaptively responding to dynamic interactive processes. The required approaches differ across ad hoc consultations and longer-term advisory sessions, necessitating context-sensitive adaptive strategies. Strengthening educators' emotional responsiveness and fostering variability and adaptability through a broad range of responsive regulatory actions is of considerable practical importance and should be regarded as a central component of professionalization.

Educators' emotional responsiveness is defined as the ability to provide learners with emotional support and to meet their individual needs, thereby fostering engagement and prosocial behavior, demonstrating emotional connection, sensitivity in managing interactions, and modeling positive peer relationships (Longobardi et al., 2022). Most studies have investigated this topic, focusing on subjective beliefs and the positive effects of learners' perception of teachers' emotional support on their sense of agency and self-efficacy (He et al., 2023; Kikas and Tang, 2019), conceptualizing it as teachers' attunement in relation to their sensitivity to learners' individual resources and displays of empathic adaptation (Silseth and Furberg, 2024). From an interactional perspective, this refers on the one side to the contextually sensitive “reading of multimodal emotional cues,” understanding of appraisal frameworks of the learner, and the interactions within the multifaceted dimensions of situated emotional experience, as well as an adaptive focus on specific resources to support emotional equilibration and the co-construction of emotions. These emotional reasoning processes, on the other hand, determine the character of emotional responsiveness, emotional display, and the recipient-oriented design of regulatory practices. While the majority of studies primarily focus on external regulatory practices, emotional responsiveness and interpersonal regulation still require a stronger conceptual, empirical, and interactional analytic foundation with linguistic grounding, with particular attention to the co-constructive dynamics through which interactants collaboratively manage these processes.

Despite a growing number of interactional-analytic studies about emotional regulatory work in therapeutic contexts, practices in the FLL advisory context have not been sufficiently examined from an interactional linguistics perspective, particularly regarding their contextual variability and adaptivity. A further research desideratum lies in understanding the different dynamics employed within a single ad hoc advisory session vs. across multiple counseling sessions, to understand the different adaptive or developmental processes involved. Similarly, the contexts of pre-service teachers, acting as FLL advisors, remain underexplored; yet, they are particularly relevant because they illustrate the micro-development of professional interactional competence and how experiences in new interactive contexts lay the groundwork for self-regulatory practice. Similarly, previous analyses have paid little attention to the contexts of service-learning, which, due to their rising significance, challenges, and the individualized engagement with learners (Reinders, 2016; Wirtherle, 2019; Macknish, 2023; Clanton Harpine, 2024), prove particularly suitable for fostering self-regulation, adaptivity, and empathy among pre-service teachers (Lazovic, 2025d) and—as the present study will demonstrate—enhancing their ability to adjust emotional responsiveness and integrate regulative practices in advisory goals.

Given the clear practical, theoretical, and empirical importance and need for more interactional linguistic studies exploring how emotional responsiveness and regulatory practices develop as co-constructive processes within ongoing interactional systems (Boiger and Mesquita, 2012) in the FLL counseling context, the present study aims to uncover the dynamics of novice advisors' emotional responsiveness and changes in the design of emotion-regulating practices. Drawing on two corpora of FLL counseling—one consisting of ad hoc advisory sessions and one longitudinal, with seven sessions conducted over the course of a semester—we analyze advisory interactions of pre-service teachers of German as a Foreign Language (GFL) in their third MA semester, acting in the service-learning context and for the first time as student teacher advisors (STAs) for international exchange students learning German as L3. To enable a fine-grained, microscopic interactional linguistic analysis, a case-study approach is employed with two comparable contexts: a single ad hoc advising session as the first case and an advising cycle consisting of seven sessions as the second. In both cases, the analysis focuses on interactional episodes in which learners display negative emotional states in situations where emotions are not the primary goal or topic of advising but instead emerge as salient factors influencing the learner's self, the learning process, and the advisory activity, thereby opening space for emotional responsiveness and calling for ad hoc or implicit emotion regulation. Beyond the analysis of learners' emotional displays, the study addresses centrally how novices recognize and respond to such displays within counseling interactions. It examines the emotion-regulatory practices they use and how these practices differ between ad hoc advising sessions and structured counseling cycles, which consist of seven sessions. Of particular interest is the kind of adaptivity or change observable in these responses in both contexts. The following sections present the theoretical framework, which integrates perspectives on emotion regulation with insights from interactional linguistics. Next, the materials and methods are described. The findings are then presented in two parts: practices observed in ad hoc advisory sessions and changes across a semester-long advisory cycle. The article concludes with a discussion of the results and a summary of the implications.

2 Theoretical and empirical perspectives on emotions and emotional regulation

Emotional experiences are dynamic collaborative “doings,” co-constructed with co-participants or “co-emoted” (De Leersnyder and Pauw, 2022). Transitional in nature (Boiger and Mesquita, 2012), emotions function as self-organizing systems (Lutovac et al., 2017), integrating bottom-up and top-down emotional processing in interaction (Parkinson, 2012), thereby generating an authentic emotional interface within the situated intercultural context (Koole and ten Thije, 1994a,b). According to the multilayered theory (Mendonça, 2024), emotions are multidimensional and narratively structured, guided by a specific inner logic of emotional reasoning (Mendonça, 2024, p. 153), supporting a coherent sense of (social) self. Their multilayered character emerges from the interaction of diverse processes, horizontally and vertically interconnected within emotional clusters that can stabilize and form affective habits and routines (Mendonça, 2024). These exhibit characteristic rhythmic flows of events that structure new experiences (Lampredi, 2024), giving rise to emotional episodes composed of multiple co-occurring emotional clusters. Emotional dynamics can be conceptualized as upward and downward spirals (Lutovac et al., 2017) that fluctuate dynamically in response to various factors, such as the emotional responsiveness of others. Specific emotions arising in the language learning process can be differentiated in terms of valence, activation/intensity, object-/topic-related triggers, and specific co-constructive dynamics, but also across the following interconnected levels:

• Relational emotions (Burkitt, 2017), understood as socially interactive emotions shaped by roles, transactions, and expectations within the context;

• Emotions related to the self-in-process, reflecting evaluations of one's ability to cope with the situation (Lazarus, 2006), self-worth/self-trust, and attributions of success and emotions related to outcomes (Perry et al., 2008; He et al., 2023; Savina and Fulton, 2024); these are situated within self-system frameworks (in the sense of ecological dynamic systems theory, Schutz, 2014), extending to identity processes and emotional experiences beyond the immediate learning activity, and related to personal history of learning;

• Epistemic emotions, connected to processes of acquisition, cognitive processing, and knowledge construction (Vogl et al., 2019);

• Meta-emotions are central for emotional regulation, supporting situational adaptivity and regulative self-monitoring (Mendonça and Sàágua, 2019).

Of particular relevance for educators is understanding the dynamics of emotional processes in their unfolding action flow, in a process-oriented perspective (Vermunt, 1995), and the dynamics of joint construction, which lays the foundation for the gradual transfer of control over the learning process from external guidance to self-regulation, as well as to adaptively organize and design emotional regulatory interventions.

Emotion regulation (ER), defined as the ability to monitor, evaluate, and modify emotions in a goal-oriented way (Thompson, 1994; Gross and Feldman Barrett, 2011), is an integral component of basic emotional processing (Mendonça, 2024). Since emotions are social co-constructions, ER is not solely a matter of self-regulation but co- or interpersonal regulation (Messina et al., 2021) and socially shared regulation (Liu and Ye, 2025; Mänty et al., 2023; De Backer et al., 2021). In the context of polyregulation (Ford B. Q. et al., 2019; Ladis et al., 2023), which involves multiple distinct regulatory approaches, these processes involve multidimensional regulations across multiple phases, highlighting a continuous interplay between individual and social regulatory dimensions. From a process-oriented perspective, ER strategies are clustered into strategies of attentional deployment (positive refocusing), situation selection and modification, appraisal transformation, and response modulation (Gross, 2014; Ford B. Q. et al., 2019). These can occur early in the process of emotion generation through antecedent-focused strategies or later via response-focused strategies (Campos et al., 2011), with evidence that early, process-oriented strategies are generally more effective than those targeting emotional responses (Sutton, 2007), highlighting the importance of considering the stage of the ER process when designing and adjusting interventions (McRae and Gross, 2020), which is relevant for the understanding of adaptive regulatory interventions examined here. Distinctions are commonly drawn between adaptive and maladaptive strategies or changing emotional valence when upregulating and/or downregulating (Gross et al., 2019). They can also be distinguished based on whether the interactants adopt a problem-oriented or emotion-oriented approach (Liu et al., 2021) or whether ER is response-dependent or response-independent (Zaki and Williams, 2013). In the FLL counseling context analyzed here, where ER is intentionally directed toward supporting self-regulation and facilitating a reflective inner compass (Assor et al., 2020), the Emotion Regulation Flexibility Framework (Kaur et al., 2025; Bonano and Burton, 2013) is of particular relevance, as it conceptualizes ER as a strategic repertoire that is implemented adaptively in response to contextual demands, regulatory goals, and responsiveness to feedback loops, leading to the development of context-sensitive ER tactics (Isaacowitz and Wolfe, 2024).

Numerous studies have highlighted different factors influencing the use of ER strategies, such as emotional intelligence (Peña-Sarrionandia et al., 2015; Chen and Liao, 2021), developmental trends that reveal dynamic interconnections between different strategies (Ha et al., 2025), associations with attachment style and perceived social support (Gökdag, 2021), emotional quality (Kozubal et al., 2023; Rottweiler, 2023; Boemo et al., 2022), and alignment with specific goals and contextual demands (Martínez-Priego et al., 2024; McRae and Gross, 2020). These point to preferred combinations of ER strategies, forming individual ER profiles within emotional clusters (Rottweiler, 2023). Few studies provide a holistic insight into the dynamics of interpersonal emotion regulation and polyregulation (Tran et al., 2023; Ladis et al., 2023). A growing body of evidence suggests the need to focus more on the flexible use of ER strategies and their dynamic interaction (Aldao et al., 2015; Troy et al., 2013; Moyal et al., 2023), as the absence of adaptive regulation skills has been shown to predict negative emotions such as anxiety (Schneider et al., 2018). Although the need to adopt a dynamic approach and to examine the dynamics of polyregulation has been acknowledged (Ladis et al., 2023; Chen and Liao, 2021), the interaction of different regulatory strategies remains insufficiently analyzed in authentic interactive contexts. Some studies (Rottweiler, 2023; Schneider et al., 2018) emphasize the importance of examining changes in regulatory processes from a longitudinal perspective, providing a starting point for subsequent interactional longitudinal analysis.

In terms of operationalization, interpersonal ER practices span a broad spectrum, ranging from explicit work on the meta-emotional layer and subjective beliefs to more implicit forms. These include micro-regulation through relabeling (Torre and Lieberman, 2018), strategies aimed at enhancing agency and upgrading epistemic stance, as well as supportive practices such as self-disclosure, more elaborated forms of joint emotional reasoning, or the expressive display of positive emotions and empathy (Savina and Fulton, 2024). These also include perspective-taking and social modeling, displaying understanding of how significant others cope with a given situation (Hofmann et al., 2016), as well as practices of reorienting the co-participant toward positive stimuli, generating alternative interpretations, highlighting schema-inconsistent information, correcting cognitions, and providing additional flexible processing resources (Marroquín, 2011). Suppression and displays of acceptance emerge as common ER strategies. Nevertheless, they do not produce positive outcomes, in contrast to reappraisal (Jurkiewicz et al., 2023), whose effectiveness appears to be moderated by perceived emotional responsiveness. These are further related to strategies of positive broadening (Fredrickson, 2004), positive reframing and proactive coping (Lutovac et al., 2017), imaginative reframing (Seebauer and Jacob, 2021), and goal-directed regulatory behaviors (Carstensen, 2006). Supporting reappraisal affordances, or opportunities for semantic reinterpretation, have been recognized as particularly important (Suri et al., 2018), and they appear to be especially facilitated in the context of joint reasoning processes (Jurkiewicz et al., 2023).

Horn and Maercker (2016) highlighted the specific functionality of co-reappraisal, in which interaction partners collaboratively work to reframe the meaning of a situation to achieve a shared new understanding. However, its effectiveness depends on the recipient's receptivity and the quality of the joint co-construction process (Pauw et al., 2024), which warrants further investigation through interactional linguistic analysis. Pauw et al. (2024) further show that emotionally poorly attuned advice can have negative outcomes, highlighting the importance of perceived emotional responsiveness, which not only enhances positive affect, coping efficacy, and relationship satisfaction but also influences the effectiveness of other ER strategies. Perceived responsiveness is partly shaped by the accuracy of perception, but a large portion is influenced by biased perceptions (Pauw et al., 2024, p. 11). Additional challenges may arise—according to Pauw et al. (2024), p. 12)—when the emotional responsiveness of the other is implicit or indirect and goes unnoticed, or when the regulating individual misinterprets the motivations underlying the use of interpersonal ER strategies, for example. A key point is the transition from displaying responsiveness to actively engaging in joint regulatory work. Liu et al. (2021) provide evidence of mismatches between emotional goals and interpersonally supportive ER strategies, indicating that co-participants do not always expect to co-regulate emotions but primarily pursue emotion-oriented goals related to their need for empathy and understanding. In contrast, supportive co-participants tend to rely more on problem-oriented than on emotion-oriented ER strategies. This underscores the need for conceptual differentiation and a more precise examination of the relationships between the display of emotional responsiveness, its perception, emotional stance alignment, and specific emotional order (Stevanovic and Peräkylä, 2015), as well as regulatory joint processes and interactional dynamics over time.

In order to broaden the methodological approaches commonly applied in ER research, this study adopts an interactional-analytical perspective and addresses several previously identified research gaps, particularly with regard to the fine-grained analysis of practices of novice FLL counselors in displaying emotional responsiveness and enacting regulatory strategies, while also examining how these practices evolve across two different time frames and contexts.

3 Emotionally responsive talk: insights from interactional linguistics

Emotional responsivity is a key interactive dimension, as the degree of arousal is closely tied to the perceived intensity of emotional responsiveness from co-participants (Peräkylä et al., 2015). Beyond recognizing co-participants' emotional states, emotionally responsive talk involves adaptively co-constructing the emotional experience in situ, thereby designing responses that align with co-participants' emotional orientations, expectations of responsiveness, and achieving attunement in emotional displays (Peräkylä, 2012). This can, among other things, involve implicitly or explicitly addressing some inferentially recognized emotional values in the co-participants' actions, or transforming them on their behalf by using specific expressions, or adapting the practice's design to align with the recognized emotional loads, or even amplifying certain emotions to upgrade some self-related processes. By using specific multimodal practices, the co-participants are co-constructing the relevance of the emotional layer, relational emotional meanings, and negotiating the situated interpretation and the function of specific emotional cues (Langlotz and Locher, 2013; Peräkylä and Ruusuvuori, 2012) as well as negotiating practices to respond in a manner that is going to be perceived and accepted as adequately and functionally emotionally responsive. Designing emotionally responsive turns presents challenges, particularly in foreign-language and intercultural contexts, as turns intended to be emotionally responsive may fail to align with an interactant's expectations. As a multidimensional co-construct, responsivity connects different perspectives on the emotional layer, encompassing the relevance, quality, and progression of specific emotional aspects, as well as their functional significance within the ongoing interaction. In order to understand these situated, co-constructive processes of designing and enacting emotionally responsive turns in situ, which arise from the attribution of emotional values to specific cues, their interactive negotiation, alignment, and the generation of shared emotions, they must be examined from a fine-grained, interactional linguistic perspective, which enables the reconstruction of situated processes of adaptive emotional responding. Due to the complexity of linking deep emotional processes with co-constructions at the interactional surface, the concept of “emotional display” is employed to capture the multimodality, fluidity, and different variations in the manifestation of emotions and emotional responsiveness in interactional practices.

Emotional display is not merely a constitutive part of an action but rather constitutes the very action that renders a response relevant (Peräkylä, 2012), projecting emotionally responsive turns, their design and sequential unfolding, even when such affective orientations remain beneath the surface of overt interaction. Of particular interest are emotional displays with ambiguous projective force, which create uncertainty about the type and intensity of emotional responsiveness expected from the co-participant and open space for negotiating emotional responsiveness. As complex, dynamically changing configurations of multimodal cues (Huynh, 2020; Peräkylä and Ruusuvuori, 2012), emotional displays negotiate and align emotional stances (Goodwin et al., 2012; Couper-Kuhlen, 2012), but most importantly, stretch the boundaries in actions, serving as a springboard for regulatory emotional processes (Peräkylä and Sorjonen, 2012). Emotionally responsive displays are crucial for anchoring emotional regulation, supporting interactional alignment, and modulating participants' emotional states.

Although the emotional layer cannot be reduced to a set of prototypical practices or resources, some interactive practices have been shown to be a central form of emotional doing (Mendonça, 2024), such as various narrative forms (Couper-Kuhlen, 2012). Similarly, some resources, such as metaphors, emotional words, response cries, claims of understanding, congruent assessments, prosodic matching/upgrading (Lee and Tanaka, 2016), or language switching (Acuña Ferreira, 2017), serve as typical practices that indicate affective involvement and invite emotional responsive actions. Some linguistic resources may appear to serve intersubjective understanding at first glance but in fact perform affiliative and emotionally responsive functions, such as alignment tokens, which reflect the dual role of interactional practices in coordinating both epistemic access and affective stance (Clayman and Raymond, 2021). Epistemic status proves to be in service of affiliation, since interactants fine-tune their epistemic claims to provide stance-congruent assessments or from a general position, respecting the epistemic domain of the other, indicating affiliation and maintaining emotional responsiveness (Koskinen and Stevanovic, 2022). Emotional responsiveness is integral to anticipatory, meaning, and inference-making processes, as well as joint (imaginative) reasoning (Larraín, 2017).

Displays of emotional responsiveness vary dynamically, shaped by the interactional history (Deppermann, 2018), transactive memory system (Wegner et al., 1985), and emotion-based implicatures (Schwarz-Friesel, 2010, 2013), influencing the situated appraisal processes and preference structures (Boiger and Mesquita, 2012; Parkinson, 2023; Godbold, 2014). Participants navigate between “cold and warm heart” and negotiate an appropriate “amount” of emotion (Rydén Gramner, 2023) by co-constructing feeling rules as fluid, situationally responsive norms, calibrating their emotional design in accordance with the co-participants' expectations of responsiveness, specific display rules, and standards of appropriateness (Fiehler, 1990). These processes are intertwined with the management of interpersonal relations, interactional roles and identities, and the negotiation of epistemic authority and deontic rights (Li, 2022). Social relationships shape the extent to which we are affected by others' emotional states, with social closeness influencing processes such as emotional contagion, shared appraisals of situations, and the co-experiencing of emotions (De Leersnyder and Pauw, 2022). Emotional responsiveness and co-constructing shared emotion emerge as a key mechanism for in-grouping, facilitating participation and the formation of group identity (Peräkylä, 2012). In institutional settings, characterized by asymmetrical rights and obligations, as well as specific institutional fingerprints and normative expectations (Muntigl et al., 2023), alternative forms may become more salient (Lee and Tanaka, 2016), leading to institutionally prestructured ways of expressing, experiencing, and responding to emotions (Peräkylä, 2012).

Building on an affiliative baseline with default values of communicating emotional stances and evaluative alignments (Stivers et al., 2011), grounded in the participants' empathic orientations and discursive or institutional norms, such a baseline may, in specific moments of interaction, be expanded through more elaborated or marked forms of emotional responsiveness, thereby shaping interpersonal regulatory practices with varying degrees of explicitness. These transitions, encompassing processes of emotional co-construction, co-regulation, and bonding, can occur ad hoc, cyclically, or in patterns, triggered by different factors and inferential processes. When activating a framework of emotional reciprocity (Stevanovic and Peräkylä, 2015), temporarily reorienting the interactional flow toward expanding the emotional layer, collisions between interactional goals or tensions within turn-taking may arise or change the dynamics and standards of emotional responsiveness in the following interaction(s). This interplay of subjective, social, and discursive emotional layers also includes the balancing between symmetry and intersubjective alignment and (functional) emotional undoing and reducing emotional responsiveness (Castellaro et al., 2024). This dynamic also functions as a resource for facilitating and aligning cognitive dimensions and affective processes.

Building on these general conceptual considerations relevant to understanding emotional responsiveness and its display, the present study focuses specifically on the context of foreign language learning counseling. Here, challenges often arise from culturally specific practices of labeling, communicating emotional experiences, differences in interpreting emotional cues and emotional responsiveness, and from selectively adapting existing emotional frameworks to new contexts (De Leersnyder and Pauw, 2022), as well as from differing dynamics in the negation of shared values of emotional cues. Within the field of counseling and therapy, numerous studies have already identified practices that facilitate emotional expression, self-awareness, and reflection of the clients, while strengthening the collaborative alliance through joint reasoning and leveraging emotional bonding to support other counseling goals. However, most of these studies have been conducted in contexts where emotional layers are already a primary focus of the counseling process, with high expectations of emotional responsiveness and regulatory work. Situations in which emotions are not the primary goal or topic of advising but instead emerge as salient yet latent factors influencing the advisory process, triggering ad hoc, emotionally responsive regulatory sequences, and warranting examination in relation to other advisory goals—forming the focus of the present study—remain largely unexplored.

These studies demonstrate that eliciting and overt emotional processing tend to be the weakest forms of emotional work (Muntigl et al., 2014, 2023), often prompting further storytelling rather than supporting reflective engagement. Preferred strategies include the formulation of prefaces as stepwise entries into clients' perspectives, the use of summarizing and reenactments, or vivid illustrations that demonstrate epistemic and affective alignment, thereby supporting self-regulation (Muntigl et al., 2014, 2023). Some of the practices analyzed include, among others, the use of specific words to modulate or generate new emotions with transformative potential for associated emotional clusters, leading to perceptual shift or supporting reappraisal, as well as practices that promote linguistic self-distancing (Shahane and Denny, 2022), for example, through shifts in pronoun usage or through repetition as a display of matched emotional stance with regulatory power (Schegloff, 1997). Furthermore, they encompass noticing practices, illustrated by the emotional impact, and modulated directives with a regulatory function (Muntigl et al., 2014, 2023). Unifying or adopting a generic perspective (Muntigl et al., 2014, 2023) is used to distance oneself from the emotional experience, shift perspectives, or direct the interaction toward a more investigative and self-regulatory orientation (Voutilainen, 2012).

Many of these practices serve to reconstruct an emotion from an expressed feeling within the framework of situated emotional experiencing, or conversely, to transform an emotion into a situated emotional experience, as will be demonstrated in the present study, in order to enable its corrective processing. A key aspect of this process is strengthening the empathic interface (Lazovic, 2025c) or empathic union, as a precondition for emotional bonding (Heritage and Lindström, 2012), and displaying emotional responsiveness. This can be achieved, for example, through the incorporation of empathic statements of understanding (Ford J. et al., 2019), self-disclosures, and simulated inner talk (Lazovic, 2025b,c). Displaying empathy (Stommel and te Molder, 2018) serves to validate clients' feelings and put them into perspective, which are combined with regulative practices of normalizing the experience (Svinhufvud et al., 2017) and presenting a problem as workable, thereby paving the way for advice-giving by negotiating the legitimacy of the client's (emotional) response to the problem. It relies on empathic modeling and active listening to extract key aspects, use them as resources for developing a problem-solving stance (Hutchby, 2005), and functionalize them while maintaining space for co-construction.

A key aspect is the adaptive modulation of emotional responsiveness, enabling the professional to either sustain the sequence's progressivity or temporarily suspend it to regulate affect and support emotionally charged interactions (Muntigl et al., 2014, 2023), according to perceived loads in the shared emotional landscape. Understanding how emotional responsiveness is modulated and adapted and how transitions to emotion regulation are enacted constitutes the starting point for our empirical exploration. In order to understand these multidimensional dynamics, it is necessary to examine situated practices across interactional trajectories over time, focusing on the co-construction of situated emotional experiences and the emergence of joint practices. However, longitudinal studies on emotional landscape in learning settings remain scarce and constitute an important research desideratum.

Extensive research on the development of interactional competencies in L2 settings shows a growing diversification of practices (Pekarek Doehler and Pochon-Berger, 2011, 2019), reflected in an expanding repertoire of context- and addressee-sensitive resources, as well as increased intersubjectivity (Pekarek Doehler and Pochon-Berger, 2011) and specialization of multimodal resources for distinct communicative purposes (Skogmyr Marian, 2023). This developmental process includes the gradual emergence of adaptivity to local contingencies and an increased orientation toward joint action, as interactional moves become progressively open to co-construction (Pekarek Doehler and Pochon-Berger, 2019; Skogmyr Marian, 2023). Studies on the professionalization of novices (Nguyen, 2012; Nguyen and Malabarba, 2025) further illustrate developmental changes, including the structuring of action, coordination of multiple action trajectories, adaptive focus management, addressee orientation, and flexible epistemic positioning. In the field of language learning advising, longitudinal research reveals increased empathy-displaying practices (Lazovic, 2025a), simulated perspective-taking through inner speech (Lazovic, 2025c), and the functionalization of self-disclosure (Lazovic, 2025b). These developments indicate a shift from ad hoc bonding strategies toward functional expansion and diversification, culminating in the specification of functions for argumentative purposes, particularly in addressing internal resistance and divergence. This shift is further reflected in changes to sequential positioning, as well as in action-tying and bridging.

Since emotional responsiveness and regulative work have not yet been studied from a longitudinal perspective, the present study draws on a micro-longitudinal interactional analysis of pre-service teachers acting for the first time as FLL advisors. By focusing on situations where emotions are not the primary goal or topic of advising but instead emerge as salient factors influencing the learning process and the advisory activity, we isolate interactional episodes in which learners exhibit negative (epistemic) emotions. Beyond analyzing learners' emotional displays, the study focuses on how novice counselors recognize and respond to such displays within counseling interactions. It examines emotion-regulatory practices and how these practices differ between ad hoc advising sessions and structured counseling cycles consisting of seven sessions. Of particular interest is the kind of adaptivity or change observable in these responses in both contexts, as well as the extent to which changes in learners' practices are evident, indicating positive transformations in their engagement and self-regulation.

4 Materials and methods

4.1 Participants

The study focuses on the practices of pre-service teachers of GFL in their third semester of a master's program, acting as student advisors (STAs) within a service-learning context. They voluntarily advise learners (L) of German as a third/additional language at proficiency levels B1 to C1, visiting Germany as exchange students. The study involves 28 STAs and 28 Ls across two different semesters, whose recorded interactions during advisory consultations constitute the primary basis for the subsequent interactional analysis. While the corpus covers a range of interactions, the present analysis adopts a case-study approach, focusing on two counseling contexts involving distinct STAs and Ls with varying L1 backgrounds, which are explored in depth through interactional analysis. Neither STAs nor Ls have prior or parallel experience in FLL counseling, making this a unique interactive context with controlled interaction parameters. The starting point of counseling sessions is biographical reflections on FLL and text-based feedback, involving two types of learner texts—a personal email and a pro–con essay. STAs provide individual support to enhance the L's language skills, which involves a range of adaptive activities, including developing learning strategies, recommending resources, providing feedback, and helping them overcome internal learning resistance, but most importantly, engaging learners in self-reflection and internal dialogue to build problem-solving abilities (Kato and Mynard, 2016). The goal was not to implement a specific advising approach but to adapt to learners' individual developmental dynamics by integrating elements from multiple approaches.

4.2 Materials

The material consists of audio recordings of counseling sessions and associated STA team meetings. Different datasets are used for the analysis: Dataset 1 comprises interactional data from 14 single, ad hoc advisory sessions, encompassing approximately 15 h of audio recordings. Dataset 2 encompasses longitudinal interactional data of 14 cases, documenting seven advisory sessions for each across one semester, with a total duration of approximately 135 h of recorded material. Dataset 3 contains recordings of four team meetings of the STAs (5 h) distributed throughout the consultation cycle, during which STAs discuss their experiences, problems, and solutions. By using the first two datasets, we employed a case study approach to compare emotional responsiveness and regulatory work in different counseling interactions. Specifically, we analyzed and compared an ad hoc, text-based advisory session on one side with a structured, longitudinal advising process spanning seven sessions (8 h) on the other. We ensured comparability by selecting cases with learners of the same gender and age and cases aligned in content and topic focus, since both primarily focus on lexical learning and learning strategies related to the academic context, alongside general reflections on language learning, which provided a common thematic basis for contrasting the interactional and emotional characteristics of the two settings. Similarly, the STAs involved here are comparable across all parameters, including age, gender, experience, background, and both interactive and reflective competencies. Conversely, the learners differ in their L1 backgrounds: the first is a teacher-education student whose L1 is Chinese, and the second is a student whose L1 is Arabic, preparing for the C1 exam and subsequent university admission test. This design enables the inclusion of linguistically and culturally diverse learners with limited authentic experience in German-speaking contexts. It allows for the examination of the advisor's adaptivity to culturally and linguistically diverse learners.

4.3 Procedures

Data were collected in a naturalistic educational setting in the university context of a master's program and within a service-learning context. Advisory sessions, including both ad hoc consultations and scheduled meetings, were audio-recorded over the course of one semester, with seven meetings distributed throughout. Participant confidentiality was ensured through anonymization of all data, and ethical approval for the study was obtained from the hosting institution. Interactants met independently, without additional contextual influences. All sessions were transcribed according to the GAT2 conventions (Selting et al., 2009), capturing verbal content and prosodic features relevant to interactional analysis. Non-verbal cues were not systematically recorded. The abbreviations A (for STA) and L (for learner) are used throughout the case analysis, in alignment with their notation in the transcripts. The study design prioritized ecological validity, aiming to document authentic interactional practices within the advisory context while providing detailed and verifiable transcripts for subsequent microanalytic examination.

4.4 Data analysis

The analysis is grounded in the framework of interactional linguistics (Couper-Kuhlen and Selting, 2018; Imo and Lanwer, 2019; Auer et al., 2020), which provides the methodological tools for examining the micro-level organization and the situated emergence of practices, as well as the description of linguistic structures as interactional resources designed for the accomplishment of recurrent tasks in social interaction. The analysis is microscopic, context-sensitive, and sequential, adopting a bottom-up, online perspective that follows real-time processing, enabling the examination of co-constructive dynamics from an emic viewpoint. Since the categories are empirically grounded rather than theoretically predetermined, the exploratory-analytical approach enables the emergence of the objects of investigation from the data itself and an unmotivated look, leading to analytic descriptions and inductive abstraction when analyzing the in situ-produced order and the participants' orientation toward it. The analysis shows how actions are implemented using linguistic resources and made interpretable for co-participants. To validate analytic interpretations, reference is made to participants' orientation, the next-turn proof procedure (Schegloff, 1996), and the display of understanding, all under the premise that actions are simultaneously context-shaped and context-renewing (Heritage, 1984). Utterances are considered both in their contextual embedding, interrelatedness, and projectivity, as they not only contribute to establishing common ground but also trigger expectations for subsequent actions and play a role in negotiating discursive norms and establishing recurring interactional patterns.

Through sequential analysis, we firstly analytically isolated instances in which the learner's negative emotional involvement or emotional state is explicitly manifested, either by direct naming of the negative emotion or through the use of expressions indicating negative epistemic emotions. In all of these episodes, emotions are not the primary objective or explicit focus of advising; instead, they arise as adverse emotional factors that influence the learner's self-concept, the learning process, and the advisory interaction. This serves as the organizing point for building a collection of interactional episodes for the analysis. Given that the analysis relies on audio recordings and thus lacks non-verbal emotional cues, the emphasis is placed on the advisor's emotional responsivity and regulatory practices, which reflect their appraisal of the emotional cues expressed in the learner's preceding turns. The fine-grained, multi-case analysis, chronologically organized, provides a basis for subsequently comparing the different practices of emotion display by learners, the emotional regulation practices of advisors, and the follow-up behaviors of learners, allowing for a detailed examination of the interactive dynamics of the interactional history (Deppermann, 2018).

To reconstruct changes over time, the analysis employs longitudinal interactional techniques, drawing from several studies (Nguyen, 2012; Pekarek Doehler and Pochon-Berger, 2019; Deppermann, 2018; Pekarek Doehler, 2021; Skogmyr Marian, 2023). First, to ensure comparability of the phenomena under investigation across interactional episodes, equivalent interactive episodes and practices were collected in each of seven sessions, using the learner's explicit emotional display as a starting point. Their chronological organization enabled cross-case comparisons in a single advisory session and over seven sessions. This analysis aims both to reveal regularities and consistently recurring aspects and to demonstrate changes and differences (Nguyen and Malabarba, 2025). The analysis of counseling sessions also considers thematic development, previous arguments, reuse of statements, growing common ground, and affiliative practices that have already been analyzed (Lazovic, 2025b,c), such as self-disclosure and simulated inner speech. After providing a fine-grained, descriptive, and analytical insight, the observed recurrences, variations, and differences are subsequently systematized, synthesized, and explained on a more abstract level. Rather than aiming to establish causal explanations, the study focuses on revealing the interactional dynamics at play, thereby providing a foundation for further interdisciplinary research.

4.5 Researcher positioning

At the time of data collection, the researcher (R) held a mentoring role for both groups, acting as a German teacher for L and as a trainer for the STAs by supporting them during group meetings and individual conversations initiated by the STAs according to their needs. Rather than adopting an instructive or suggestive role and influencing their behavior, R supported their autonomy in the process by providing motivating, open, constructive impulses, as well as fostering a cooperative atmosphere focused on collaborative problem-solving and resource orientation. While prior interactions and R's broader involvement in the process contributed to expanding epistemic perspectives by providing deeper insights into interactional and learning dynamics, the data analysis and interpretation strictly followed interactional-linguistic methodology and were not influenced by experiential biases, subjective preferences, or epistemic stances. The fact that the data were collected 7 years prior to the analysis further reinforced this by ensuring temporal and contextual distance. The interpretative basis was additionally secured through systematic reflection on and control of the researcher's own epistemic beliefs, complemented by critical discussions of the data in colloquia, in line with the interpretative logic inherent in interactional-linguistic approaches.

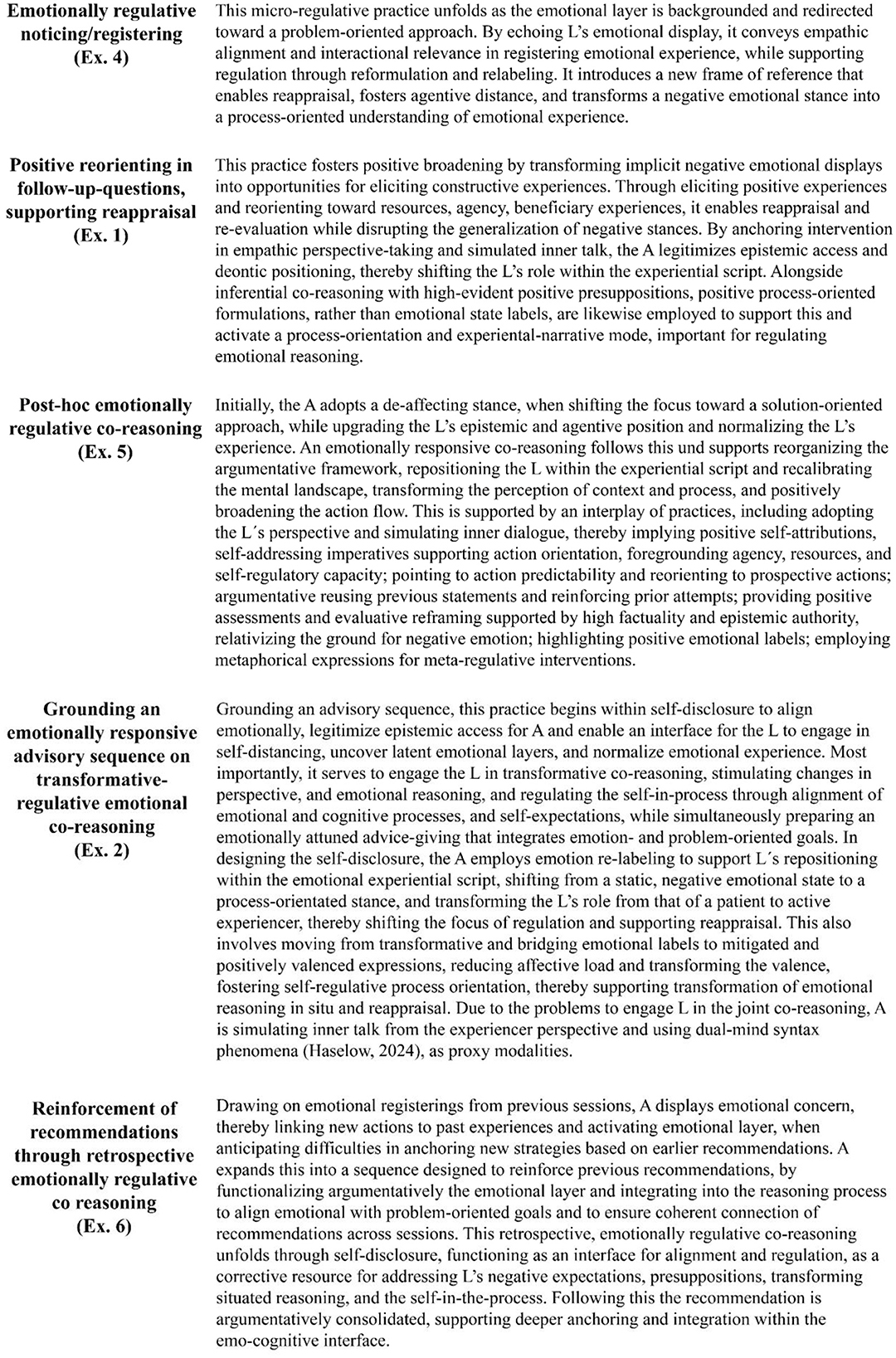

5 Findings

Before presenting the findings, an exploratory account of the STAs' reflections on the emotional dimension of advising (Lazovic, 2025a), extracted from group discussions (Dataset 3), is provided to contextualize the results. STAs generally notice the emotional load experienced by Ls, yet often encounter difficulties as emotions appear inaccessible to them. Some STAs express the need for emotional distancing and struggle to respond appropriately, indicating problems in handling emotional reciprocity. This is partly due to their belief in learners' capacity for automatic self-regulation, their conviction that language advising is not therapy, and their belief that emotions should not be explicitly addressed. STAs perceive challenges arising from the multidimensional nature of addressing both learning-related emotions and broader emotional baggage from diverse FL contexts, as well as from the emotional dynamics generated within the advising setting itself. STAs demonstrate, however, awareness of ER by fostering positive emotional experiences by upgrading positive valence in feedback actions, supporting narrative practices, and initiating small talk, while consciously avoiding epistemic imbalances. They are aware of their use of self-disclosures as de-affecting ER practices, as well as normalizing and broadening strategies while reframing self-expectations positively and supporting reappraisal. Some STAs employ a strategy of emotional challenging as a strategic intervention, either by inviting reflection on difficult emotions, confronting them, or deliberately activating emotional responses to strengthen emotional resilience. Across reflections, STAs emphasize the importance of calibrating the intensity of emotional engagement to avoid negative effects or loss of emotional bonds. This is partly confirmed and further elaborated in the following sections, which illustrate the interactional analysis of emotional responsiveness and regulatory work in two contexts: an ad hoc advisory session (Section 5.1) and a longitudinal case spanning seven sessions (Section 5.2).

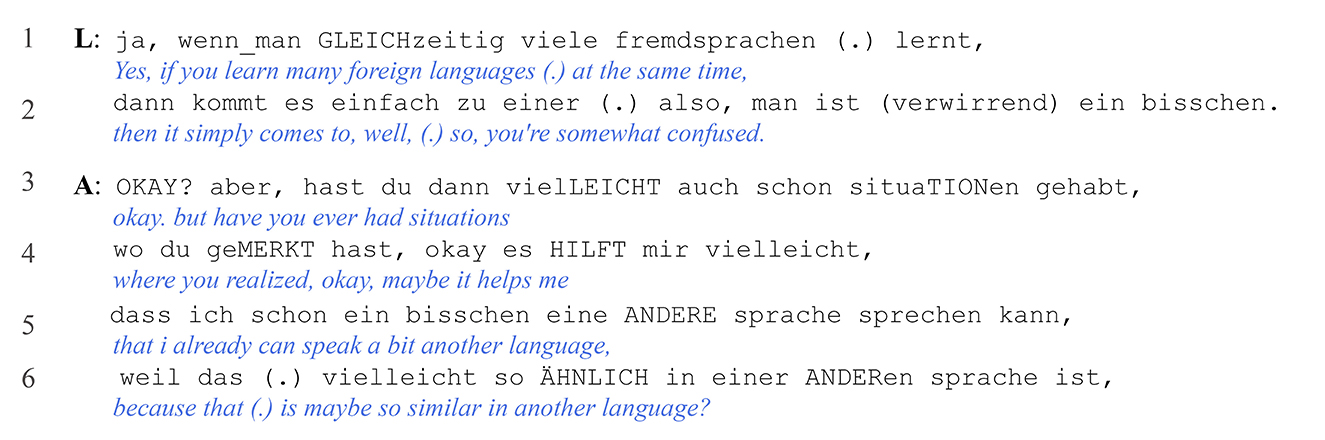

Example 1: “You are somewhat confused” (35.35–36.31 Min).

5.1 Emotional regulative work in an ad hoc advisory context

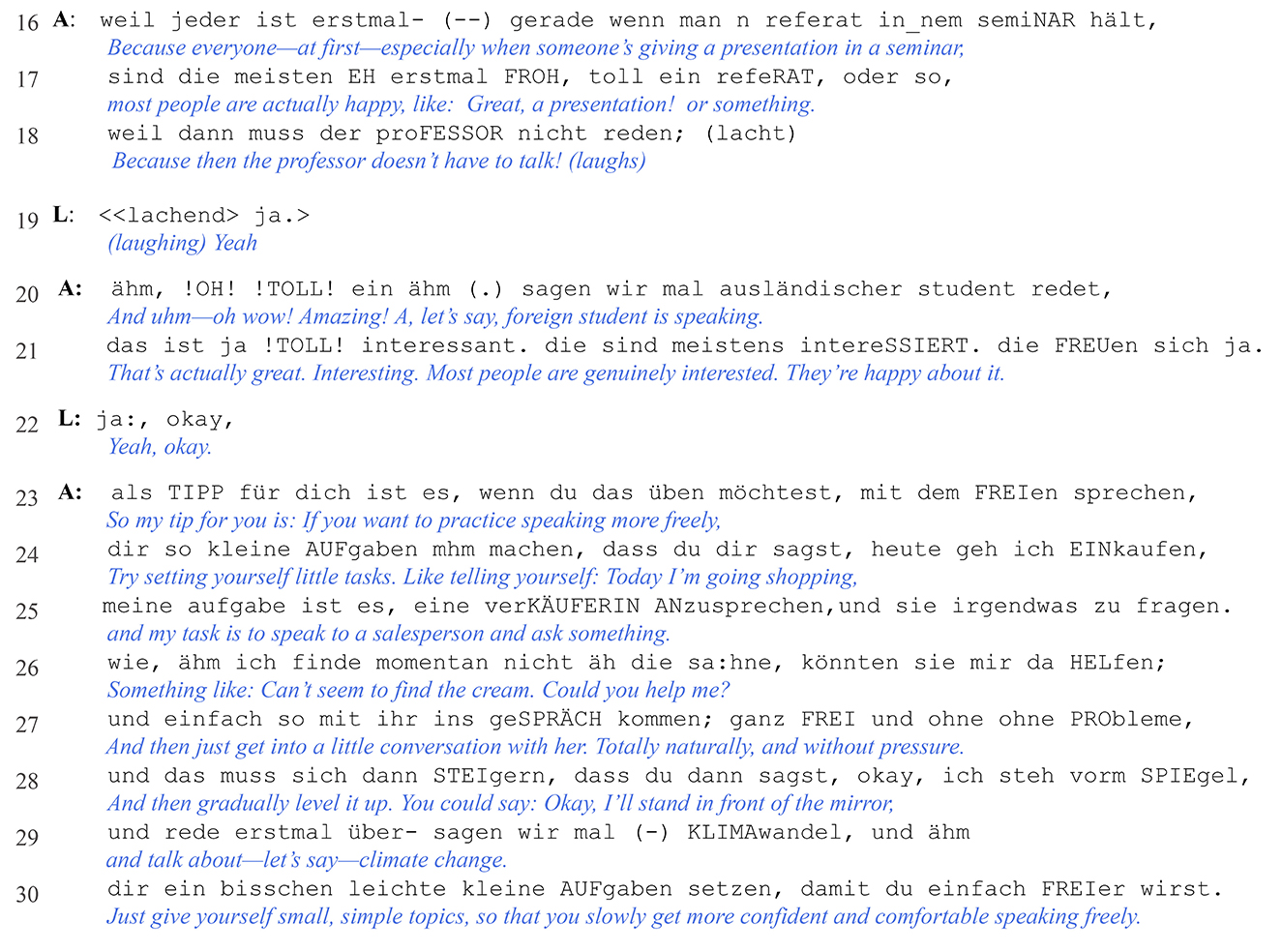

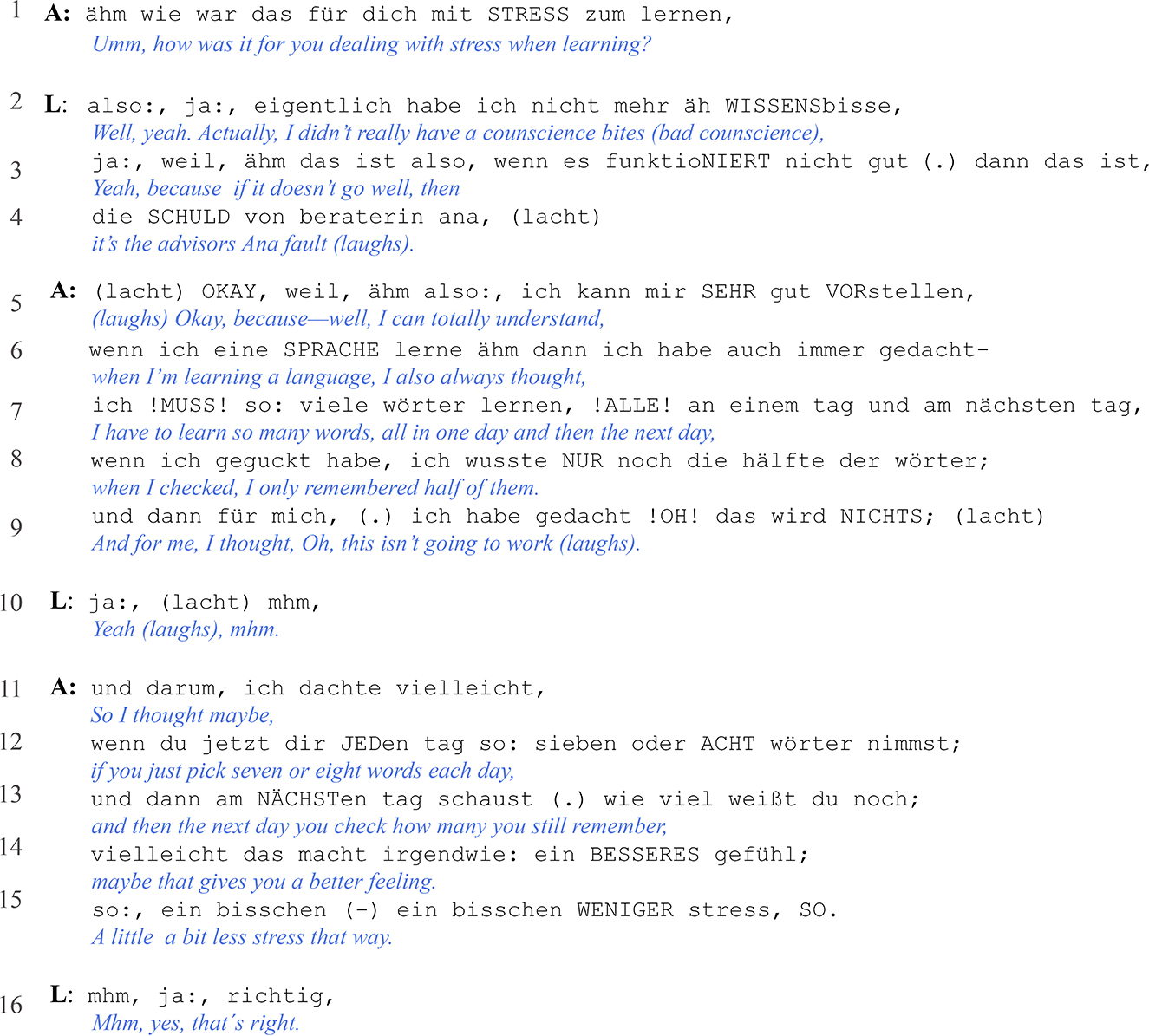

In ad hoc advisory interactions, emotional regulatory work predominantly unfolds indirectly, becoming increasingly salient through the initiation of reflection on “inner feelings” and used as an anchor for generating new learning approaches. Some previously analyzed practices aimed at balancing the emotional landscape include mitigating negative emotional valence in feedback (Lazovic, 2025a), normalizing through self-disclosures, and transforming through simulated inner self-talk (Lazovic, 2025b,c). When responding to expressions of negative epistemic emotions, STAs generally tend to focus their interventions on alleviating strain on the self and preserving the L's sense of self-efficacy, as well as normalizing negative emotional experiences, rather than engaging in diagnostic efforts to uncover the underlying cognitive and emotional dynamics. STAs also promote positive emotional experiences through practices such as epistemic self-downgrading, empathic aligning of perspectives, demonstrating understanding and positive emotional stances through reinterpretation and positive reframing of attributions, and resource-orienting, serving as strategies for positive broadening. The ad hoc advisory session analyzed here comprises three emotional episodes, showing the learner's increasingly explicit emotional displays, leading to different regulatory practices. The following example (1) illustrates the first emotional episode. It starts with L, indicating an implicit negative epistemic emotion for the first time in the interaction, when coordinating multilingual learning processes (line 2, verwirrend), using general rather than explicit self-reference and downgrading its relevance (ein bisschen). A follows with questions to deepen reflection, while simultaneously offering a positive reinterpretation that focuses on resources and evokes positive emotional experiences (lines 3–6). This is demonstrated by positive reorienting in follow-up questions, supporting reappraisal.

Following a display of understanding (“okay”), supporting normalizing and displaying default responsiveness, A transitions with an adversative aber (“but”) to an implicit regulative sequence, attributing a positive stance toward the learning process and presupposing a favorable emotional experience (L as beneficiary) as self-evident (schon gehabt, gemerkt). STA does not directly address negative emotions but instead replaces them with evident positive experiences, thereby activating compensatory and resource-oriented capacities. The following practice of simulating the learner's inner self-talk (lines 4–6), used as an empathic interface, is central to deeply anchoring this intervention, legitimizing epistemic access, and securing acceptance of the intervention while also foregrounding agency and scaffolding transformative processes. By evoking and presupposing positive emotional experiences (lines 5–6, drawing on previous knowledge, resources, and analogical thinking), this serves as a positive affective anchor that facilitates the cultivation of a solution-oriented mindset and supports positive broadening, as well as the self-regulatory system, by activating resource-oriented thinking. This practice of positive broadening, when eliciting positive and beneficiary experiences, reorients toward resources and agency, enabling reappraisal and reevaluation while disrupting the generalization of negative stances. By anchoring intervention in empathic perspective-taking and simulated inner talk, the A legitimizes epistemic access and deontic positioning, thereby shifting the L's role within the experiential script and activating a process-oriented mode, essential for regulating emotional reasoning.

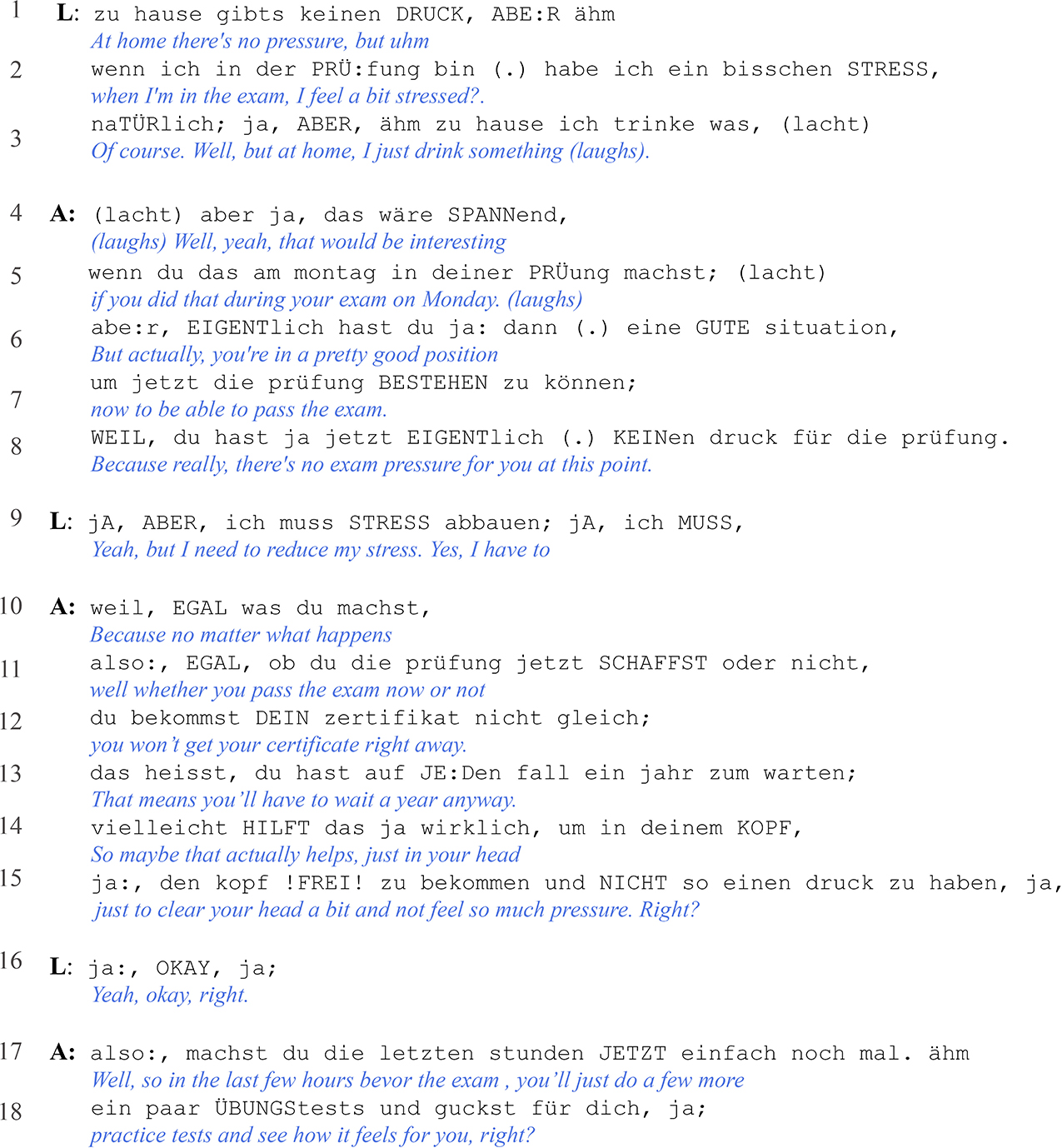

In the following episode (Example 2), L explicitly addresses difficulties in text comprehension, particularly in relation to unknown words (lines 1–3). This contains markers of emotional involvement, such as hesitation, pauses, and vague references to difficulty. Notably, it includes the lexical item “to hinder,” which, regardless of its core semantics, is marked by emphatic stress, evoking additional ambiguity as an emotional load cue. This triggers an emotionally based implicature on the part of A, who shifts the interactional focus toward emotional self-regulation rather than engaging in a diagnostic manner or offering concrete recommendations for addressing the comprehension problem. In doing so, A first displays emotional responsiveness, establishing an empathetic interface through reference to equivalent experience, and responds to the issue through self-disclosure (lines 4–8), formulating the epistemic emotion of being overwhelmed due to an excess of unknown vocabulary. This develops into transformative emotional co-reasoning, serving to ground an emotionally responsive advisory sequence that integrates emotion- and problem-oriented goals.

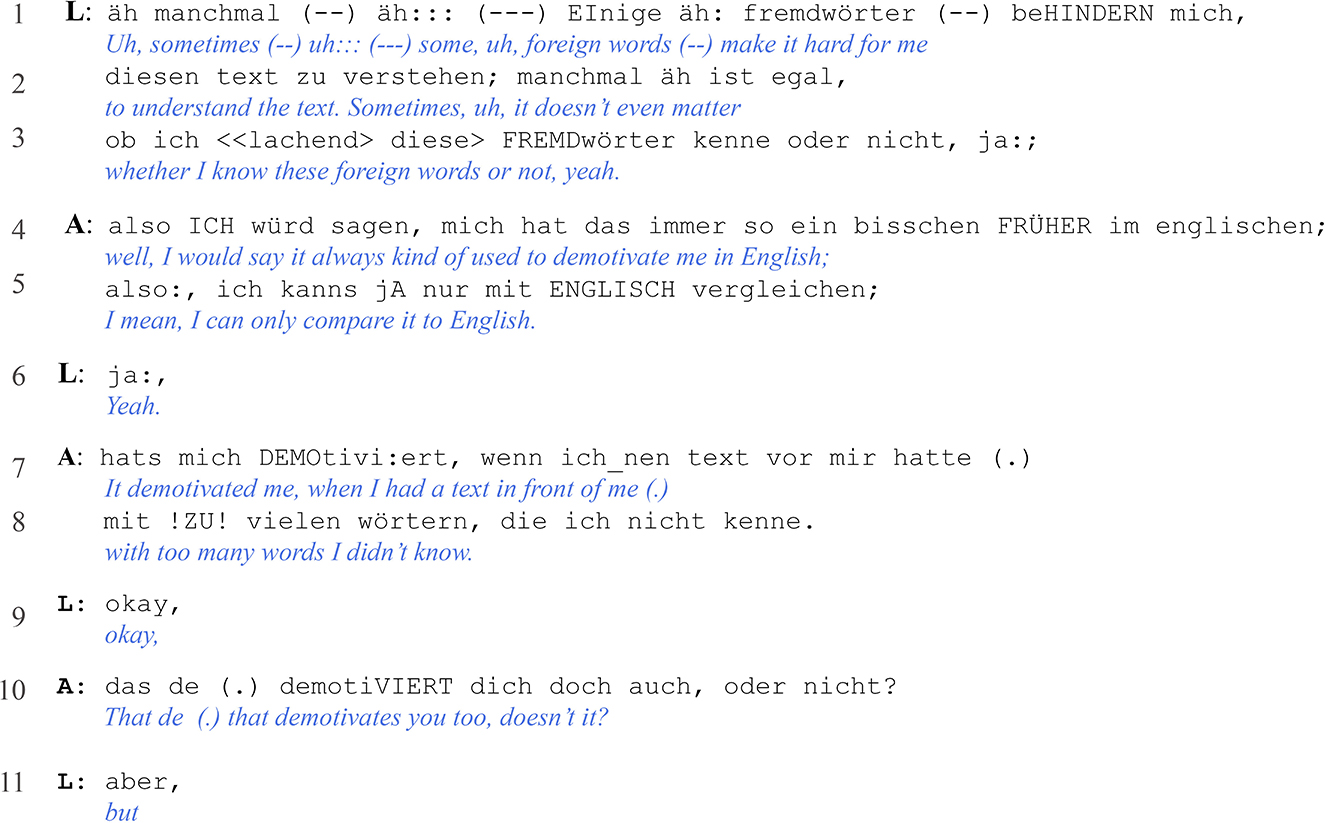

Example 2: “I always found it demotivating” (38.35–39 31 Min).

When aligning a self-disclosure to the L, the A redirects the emotional focus by referencing the state of being demotivated (line 7) and shifting the semantic role previously associated with the verb hinder—from the patient role (with static, negative emotional state, blocking action) to that of the experiencer, one undergoing an emotional process triggered by external conditions, preparing the shift for being able to self-control the emotional experience (hats mich demotiviert). Similarly, the sequential order, beginning with naming emotional experience, followed by actional script with agentive situative positioning, leading to a prominent prosodic emphasis on the intensifying particle zu (line 8) and explicit naming of the cause (too many words, not known)—serves to shift the attribution toward real, objective difficulties, thereby decoupling it from the emotional experience and self-attribution and shifting the focus of regulation. This repositioning in the emotional experiential script is followed by an assumption of equivalent emotional experience (line 10), thereby creating a space for initiating reflection on the emotional experiencing process itself as a basis for its regulation. Through emotional expression and reframing on behalf of the learner, A supports emotional awareness, acceptance, and shifts the focus to the mode of situated emotional experiencing, aiming to involve L in reflection but to scaffold the overcoming of emotional blockages through process orientation, acceptance of affect, supporting appraisal, and the fostering of agency. It serves to engage the L in transformative co-reasoning, stimulating changes in perspective, emotional reasoning, and regulating the self-in-process.

Although L signals misalignment at this point (aber, line 11), A continues with another paraphrase (line 12) of the empathic assumption of shared emotional experience. Here (lines 12–15), A reformulates a shared emotional experience with a softened, positively valenced expression (nicht so Lust haben), but avoids direct addressing, shifting to general subjects (man), which supports self-distancing and normalizes the emotional experience. Using question-tag ODER facilitates collaborative engagement with the shared experiential and emotional space. Since L minimally responds (line 13), indicating uncertainty, the practice of shared internal talk as inner dialogue is employed again (line 15) from the generic perspective of the experiencer in process, as well as dual-mind syntax phenomena (Haselow, 2024), foregrounding the modality of situated emotional experience processing while attenuating emotional intensity by reducing the affective load to a noticing-surprise interjection (oh) and diminishing the depth of the emotional experience. This also involves moving from transformative emotional labels (lines 7, 10) to mitigated (line 12) and positively valenced expressions (line 15), thereby scaffolding a reduction in affective load and transforming the emotional valence, which fosters a self-regulatory process orientation. This dynamic—from representative addressing a negative emotional state to its transformation into an emotional experience and subsequently to a reduction of affect and its normalization—functions as an emotion-regulatory scaffolding, serving here as emotional grounding prior to offering recommendations and as argumentative backup (line 16).

L is repositioned into the role of being able to self-regulate the process, which forms the basis for the recommendation of self-management and regulation of self-expectation within the process, specifically regarding the selection and control of challenge, cognitive load, or harmonization of emotional and cognitive dimensions. Transformative emotional co-reasoning is preparing an emotionally attuned advice-giving that integrates emotion- and problem-oriented goals.

A's recommendation to reduce cognitive load (lines 18–21), simplify learning processes, and align cognitive activity with emotional affordances or interfaces aims to harmonize self-expectations and ensure positive experiences of self-efficacy and demonstrates the emergence of advice that is not only aligned with but also enhances emotional self-regulatory work, demonstrating an emotionally responsive advisory practice that integrates emotion- and problem-oriented goals. This example, however, illustrates the problem of matching the empathic projection and fostering L's emotional responsiveness, which appears to become more explicit subsequently.

As the conversation progresses, L grows more comfortable sharing his emotions, reflecting the positive effects of strengthened emotional awareness in combination with A's emotionally responsive and empathic regulatory approaches. In the next episode, L initiates an explicitly meta-emotion-related advisory intervention, as illustrated in Example 3, where he directly asks about overcoming speaking anxiety (lines 1–5), indicating some prior emotional involvement through a comparison with L1 speakers. L starts by referencing a negative emotion shared by the entire group, upon which L bases his own emotional experience equivalently and formulates the advisory request (line 5), by using in-grouping as a face-saving attributional mechanism. L demonstrates emotional self-awareness and self-regulation orientation, thereby initiating a meta-emotional advisory action. Although anxiety in situations of free speaking is explicitly foregrounded, additional emotional dimensions—emerging from the conversational context and inferred empathically—surface in the counselor's emotional responsiveness, even when not overtly expressed, reflecting the multilayered emotional landscape that unfolds and develops over the course of the interaction, with increasing empathic interface. This leads to a complex advisory episode with different layers of regulatory intervention, beginning with explicitly addressing and correctively transforming presuppositions, shifting situational and self-perceptions, normalizing emotional experiences, and supporting through situated emotional co-reasoning. A begins (lines 6–7) with a mitigated rejection of the presupposition (du darfst nicht) by referencing L's previous statements (line 7) as false assumptions, followed by a corrective formulation of the emotional framing of the situation and a re-evaluation of the experience within the given context and with regard to the emotional load on participants (lines 9–10). Rather than a direct negation, which remains truncated (line 6), the utterance is reframed as a mitigated self-directed appeal to inferential activity of thinking (dann darfst du denken), thereby shifting the stance toward generalization (jeder, da) and explicit transformation of basic situation-related presuppositions, normalizing and softening the feeling of anxiety (line 9). This is then generalized and expanded to persons who may appear confident, successful, and free of anxiety (line 10) while, at the same time, engaging in reappraisal within the interpretive frame of ‘emotion hiding.”

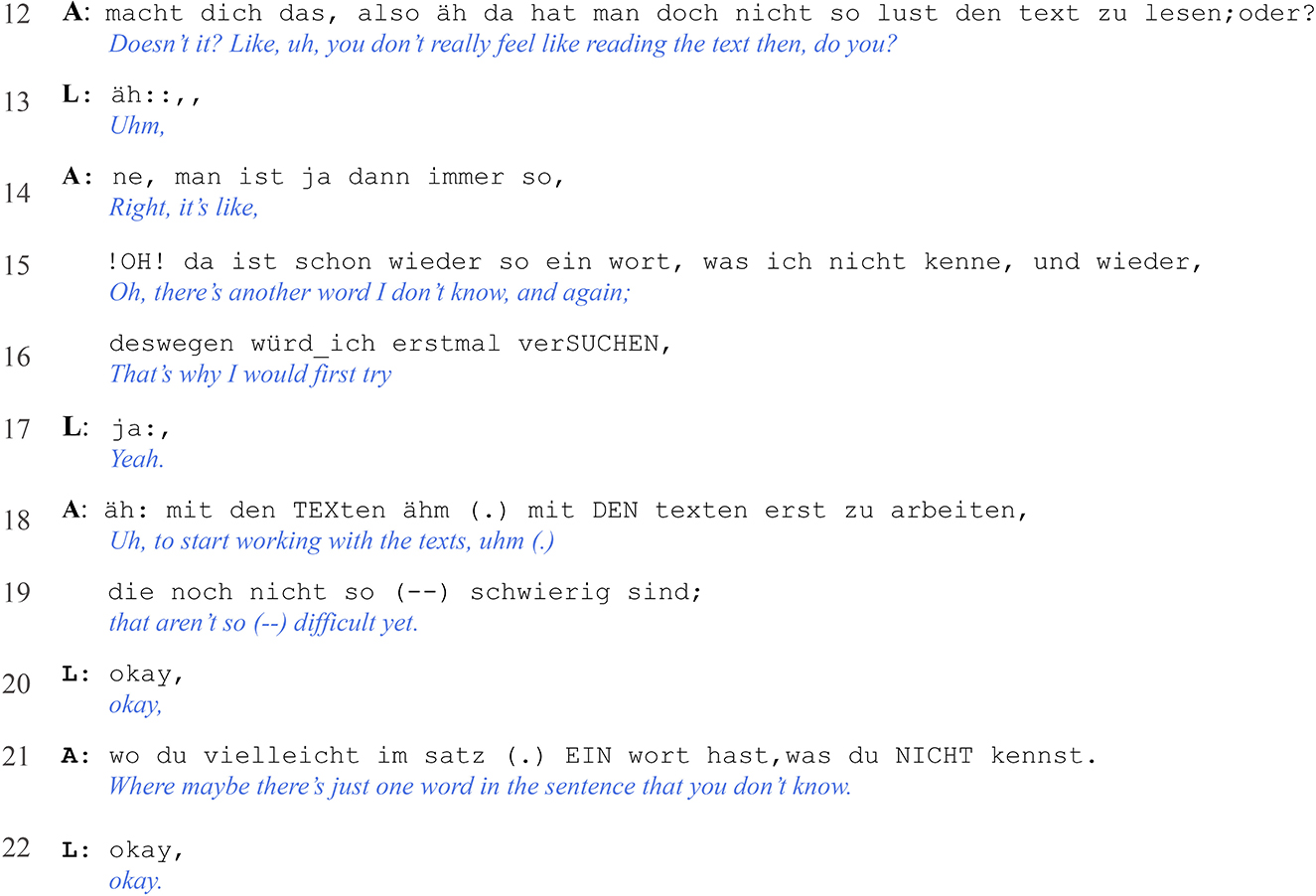

Example 3: “How can I overcome this speaking anxiety?” (49:26–51:53 Min.).

Following a discourse-structuring but epistemically reinforcing discourse marker, so (line 11), A transitions further to the social-interactive dimension of emotion by addressing interpretative frames related to others' perceptions and attitudes toward the self (lines 11, 13, 15) in the context of a university seminar. This is underscored by the use of generic pronouns (keiner) and the claim of the others' “positive intention,” implicitly contrasting with L's presumed negative expectations of others' opinions (line 11). These are combined with directives (du musst), aimed to invite self-correction in the inferential process (lines 12, 14), mitigated through the use of self-referential semantics (du dir), the strategic reuse and argumentative functionalization of the learner's own statements, and the mitigating use of einmal/erstmal, supporting process orientation. By simulating the inner talk of the hypothetical other in the seminar context (line 13), the advisor animates negatively projected self-assumptions, thereby enabling an emotional confrontation with direct negative formulations (du redest Blödsinn; ist der blöd), which are framed as self-generated negative self-assumptions internalized as projections. A intervenes in the appraisal process through social self-remodeling, aimed at distancing oneself from negative self-evaluations and reducing the projected significance of the other, by using the negative general pronoun (keiner). A first explicitly references the negative assumptions, as to be solved by self-acknowledging and self-admitting (line 12, must sich eingestehen, einreden), facilitating regulative self-awareness, and then reuses the learner's previous formulations on ER (line 14). This dynamic illustrates the shift from initially operating on self-awareness to directly addressing emotional self-regulation, as well as the increasing intensity in confronting the situated negative experience and transitioning from situational, external, and other-related social perceptions to internal self-related ones.

A is subsequently expanding this with further emotional layers (lines 16–21), aimed to replace the previously expressed negative emotion with a positively reframed affective stance in the process of situated and shared emotional experiencing, supporting in-grouping, reappraisal, and situation modification, once again through the practice of simulation of the participant's inner talk (lines 20–21). This manifests in positive evaluations, the naming of states or emotional actions, and the establishment of a positive affective stance, employed when staging the positive situational thinking of others (e.g., froh, toll, interessant, and freuen sich), which exerts a corrective influence on reappraisal processes through positive re-evaluation. A new mode of in-grouping is here constructed, grounded in the invocation of a shared epistemic and social identity as students (we vs. the professor), which overrides the previously established in-grouping based on a shared L1 (lines 16–19). This shift facilitates alignment and is affectively positively taken up by L (lines 19, 22).

This social-interactional alignment forms the basis for addressing the final and particularly sensitive dimension of social identity-related emotion embedded in the emotional cluster previously expressed by L, namely, the perceived difference and presupposed gap between international students and L1 speakers, which A, in an emotionally responsive manner, recognizes as a latent layer requiring regulation within this cluster. A builds on the preceding positive affective valence and alignment by staging a display of positive stance (line 20) and then integrates this dimension of otherness in an in-grouping manner, illustrating it within the ongoing framing. This is again followed by an explicit simulation of the inner speech (line 21), which is then framed as an expression of interest and enjoyment (interessiert/freuen sich) and explicitly labeled as a positive emotional stance. This abstraction of a positive emotional quality as the significant other's positive emotional stance in the context signals the conclusion and pre-closing of the emotion-regulatory sequence, which subsequently transitions into the core advisory phase with concrete recommendations.

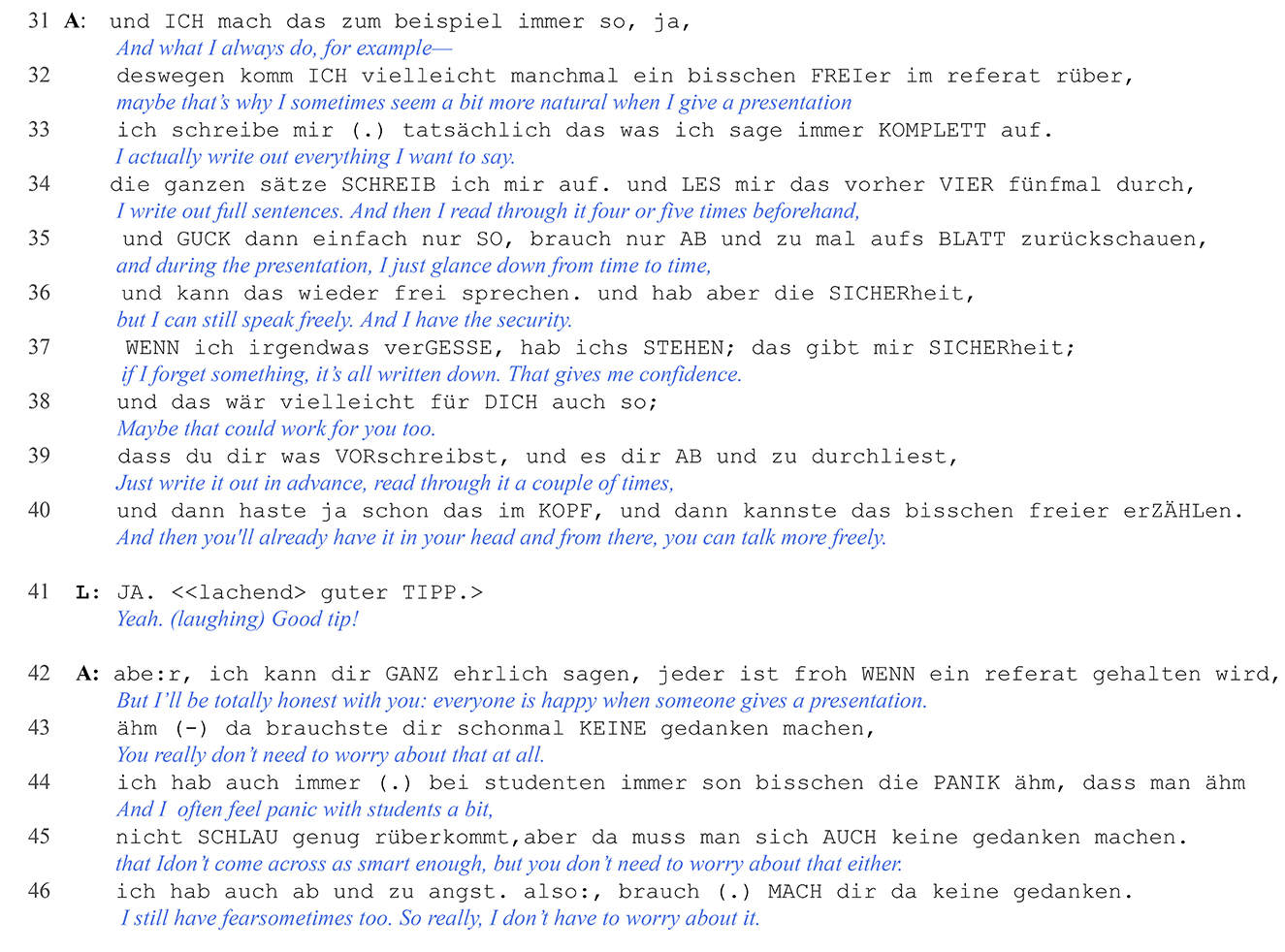

Recommendations are explicitly introduced as mitigated “tips,” highlighting the beneficiary role (für dich) and framed as an open, self-determined choice regarding their acceptance (line 23). The right-dislocated structure indicates a clear topical shift and a new focus. A offers two potential solutions, both showing emotional responsiveness and alignment: one by adopting the learner's perspective (lines 24–30), and the other through self-disclosure involving projected experience (lines 31–41). Both recommendations incorporate an emotional self-regulatory dimension, presented in a way that promotes positive emotional reasoning and self-management, thereby linking emotional goals to problem-oriented ones. These suggestions are not only designed to address the learner's current emotional difficulty but also align with the preceding emotion-regulatory interventions, indicating the use of the transactive memory system. This indicates working toward coherence in emotional clusters and developing emotionally regulatory strategies consistent at the discourse level. In designing this, A simulates emotional self-talk (dass du dir sagst), emphasizing agency, self-regulation, and a positive attitude toward learning experiences in concrete, everyday activities (lines 24–26, 28). Embedded within everyday-relevant framings, this design demonstrates empathic perspectivization in recipient-tailored action contexts, related to specific goals, supporting goal-oriented reasonings (line 30). A begins with simple and secure context references that strengthen a positive emotional stance (lines 24–27), before shifting to a more demanding context (lines 28–29), evoking experiential analogy, drawing on the metaphor of logical progression, framing it in a consecutive-additive manner (by frequent use of und dann), and presupposing self-regulation/monitoring. Within this advisory context, emotional framing occurs through simulating positively valenced emotional experiences, supporting self-efficacy and self-monitoring, as well as promoting positive emotional reasoning. In this way, the previously expressed negative emotion is transformed (frei, ohne Probleme), supporting emotional self-regulated experiencing within the process and indicating A's working on coherence within the emotional landscape. Alternating between direct and internally simulated speech, generic expressions, and recipient-addressing recommendations sustains an emotional dynamic that both relaxes and elevates the advisory process.

The next recommendation (lines 31–40), based on self-disclosure with high evidential power as repeated and generalized experience, demonstrates an indirect recommendation while displaying situated (emotional) reasoning, maintaining a positive stance when taking potential limitations into account, thus argumenting in a goal-oriented manner (line 33–37). A connects this directly with L's goal (line 32), highlighting the positive emotion of being free and safe in action (lines 32, 36, 37, 40), thereby navigating through the action flow in a process-oriented and goal-directed way, mitigating the emotional involvement. Subsequently, a proposal for L is formulated in a pointed manner and justified in a way that connects it to the preceding discourse (lines 38–40), highlighting the positive (emotional) outcome. This self-disclosure demonstrates an emotionally aligned, goal- and resource-oriented co-reasoning, with an implicitly advisory and suggestive character.

After the learner's affirmative response to the recommendation (line 41), A initiates a final wrap-up sequence that reactivates and argumentatively integrates key elements from the prior emotion-regulatory phase. This serves to stabilize the L's orientation toward the proposed strategy and align different emotional reasons and arguments coherently. Along with repetitions, the negative emotion is mitigated and transformed through self-disclosure (lines 44, 46), normalizing and shifting from an affective to a cognitive-reflective level. Beyond aligning shared experiences, the learner is positioned as “overthinking” within a reassuring directive, which suggests suppressing or regulating cognitive activity at a meta-emotional level (lines 43, 46). This reframes the emotional dimension cognitively, thereby transforming it into a solution-oriented manner.

Within the empathic interface, some self-related attributions are projected onto the L (lines 44–45), such as self-expectations regarding social recognition (schlau rüberkommen) and affective self-understanding and awareness (Panik haben). This contributes to a sense of in-grouping, counteracting L's previously expressed feeling of being positioned as part of an outgroup. As a form of affiliative positioning, this is a subtle intervention that involves shared or co-constructed emotion in the L's social self-perception, reinforcing relational alignment, affective inclusion, and supporting in-grouping while transforming the negatively charged emotion of anxiety into a more affective yet controllable, normalized state of emotional flow.

A similar form of emotional-regulatory wrap-up is equally evident at the end of the session, where concluding suggestions are articulated from a simulated, agentive perspective and attributed to L as positive reasoning. These take the form of concrete, coherently summarized, and condensed everyday scripts with self-regulative emotional reasoning in a generic, slogan-like form of self-imperatives, such as, in this case, the formulation “sich einfach trauen, einfach ins Gespräch kommen.” The formulation indicates the shift away from emotional state labeling (as static, obstructive, and disconnected from the new experience process) to situated, self-regulatory emotional processing embedded in a positively charged emotional framework.

5.2 Longitudinal insights into STA's emotional responsiveness and regulatory work

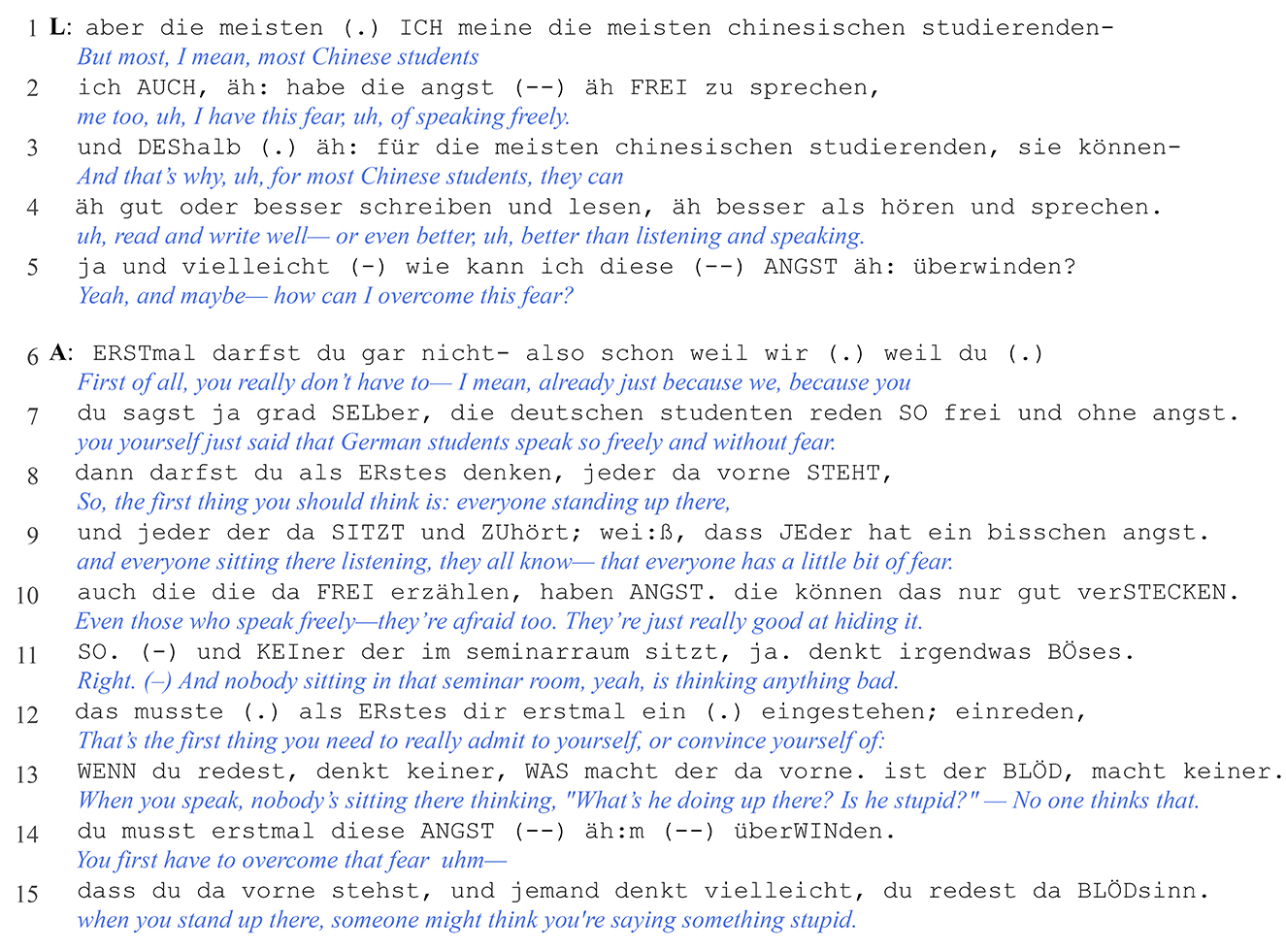

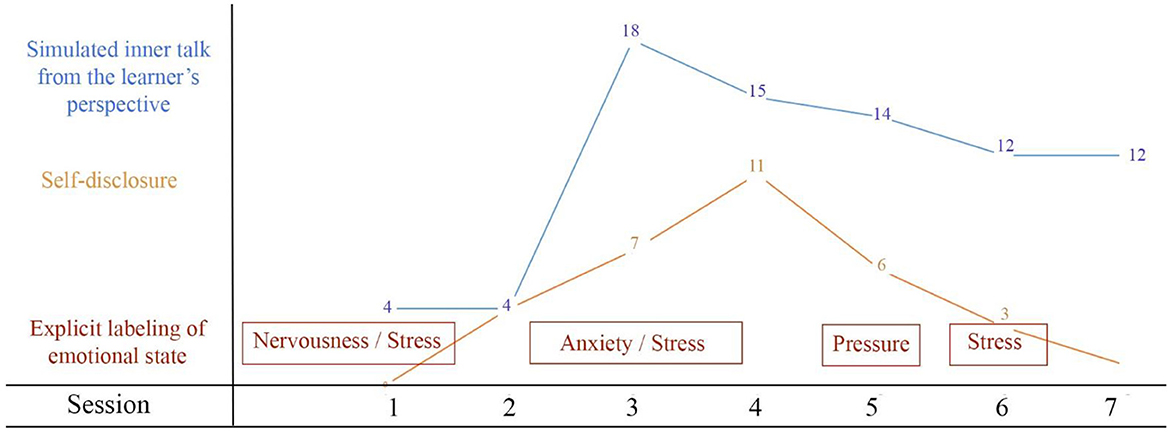

The analysis of the counseling cycle shows that negative emotions are rarely explicitly addressed and are typically related to anxiety (Figure 1). ER is achieved implicitly through self-disclosures and simulated inner dialogue from the learner's perspective (Lazovic, 2025b,c), with a significant increase in their use over the course of the counseling cycle (Figure 1). Over time, their emotional valence shifts from initially mitigating negative affective loads to a stronger focus on positive emotional values and resource-orienting. Our analysis examines the STA's emotional responsiveness throughout the counseling cycle, with a particular focus on sequences in sessions 1, 3, 4, and 6 where the learner signals or labels negative emotional states.

Figure 1. Frequency of self-disclosure and simulated inner speech across seven sessions, including explicit labeling of the learner's emotional state.

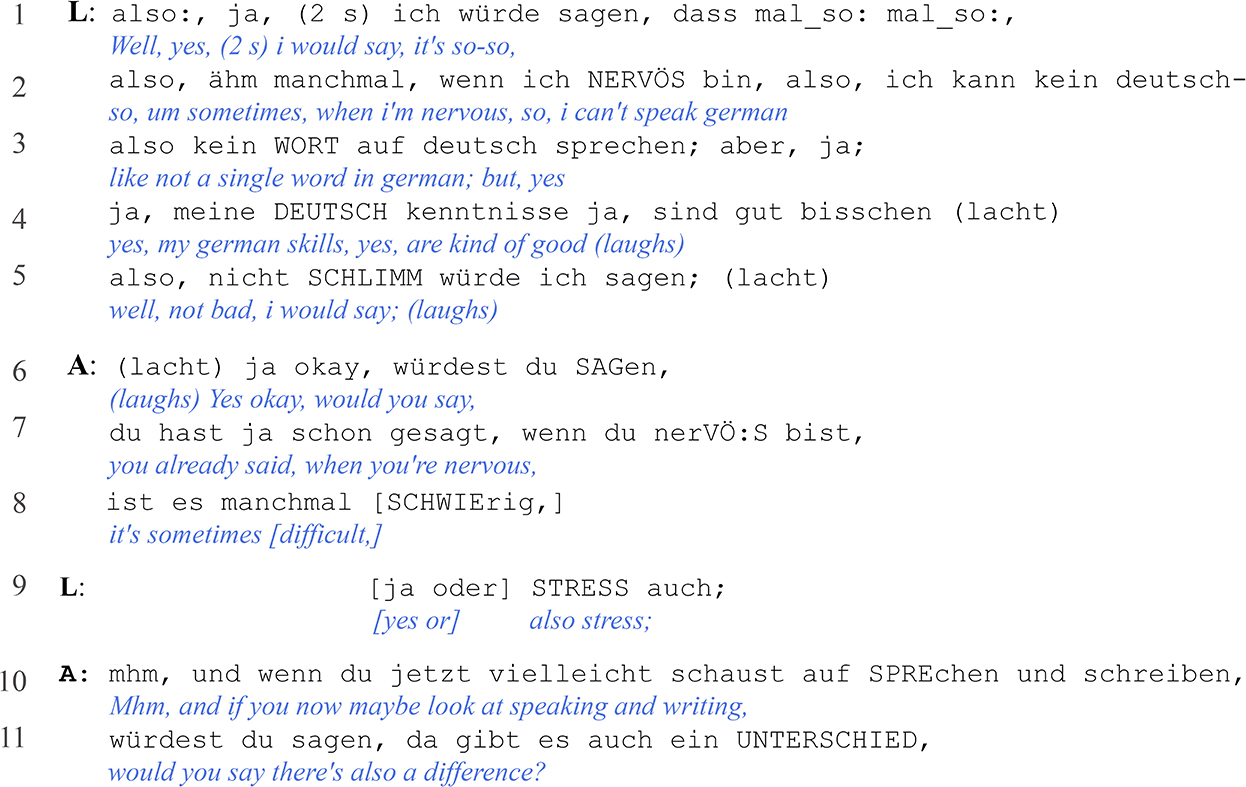

The first occurrence in the initial session of the counseling cycle is a response to STA's prompt regarding self-assessment (Ex. 4): L expresses relative satisfaction (nicht schlimm, line 5) and uncertainty, simultaneously expressing a perceived reduction in competence and an internal blockage, explicitly attributing these to a state of nervousness (line 2) or stress (line 9), without further elaboration. Rather than expanding on this emotional disclosure, A—following her pedagogical priorities—shifts the topical focus toward the perceived differences between writing and speaking (lines 10–11). The emotional dimension seems to be generally backgrounded, likely due to competing interactional goals and the still-forming relational basis between L and A. Nonetheless, A displays a form of basic emotional responsiveness (line 6, expressed through acceptance and a relaxed smile) and emotional noticing and registering by referencing and echoing L's wording (lines 7–8), indicating this emotional statement as interactionally relevant, yet mitigating its intensity through refocusing. L's affective self-assessment about the negative consequence (lines 2–3) is reformulated and relabeled into the softened and more normalized phrase it's sometimes difficult (line 8). This move shifts the affective framing from a static, state-related, general orientation toward a processual understanding of emotional experience. This is achieved through affective neutralization and relativization (sometimes), by introducing a new frame (difficult, related to complexity) and through upgrading epistemic certainty and factuality indicators (it is) for objective obstacles, thereby creating greater and relaxing agentive distance. This functions as both affiliative and micro-regulating, transforming the emotional stance in the process, but without going deeper into the regulatory work.

Example 4: “Sometimes, when I am nervous” (Session 1, 4:42–5:20).

Interestingly, up to session 3, no additional emotional self-disclaimers are produced by the learner, potentially due to reduced emotional responsiveness of A or a mismatch in expectations, but there is a marked increase in the use of the terms “schwer” or “schwierig,” which appear to function here as interactively co-constructed placeholders for emotionally charged experiences. Evident here is a difference between A and L, revealing distinct conceptualizations, since L tends to use schwer (hard) and A opts for schwierig (difficult). This contrast reflects differing perspectives on the nature of difficulty, being more experiential and affectively loaded in L's case and more cognitive, multidimensional, or task-oriented in A's.

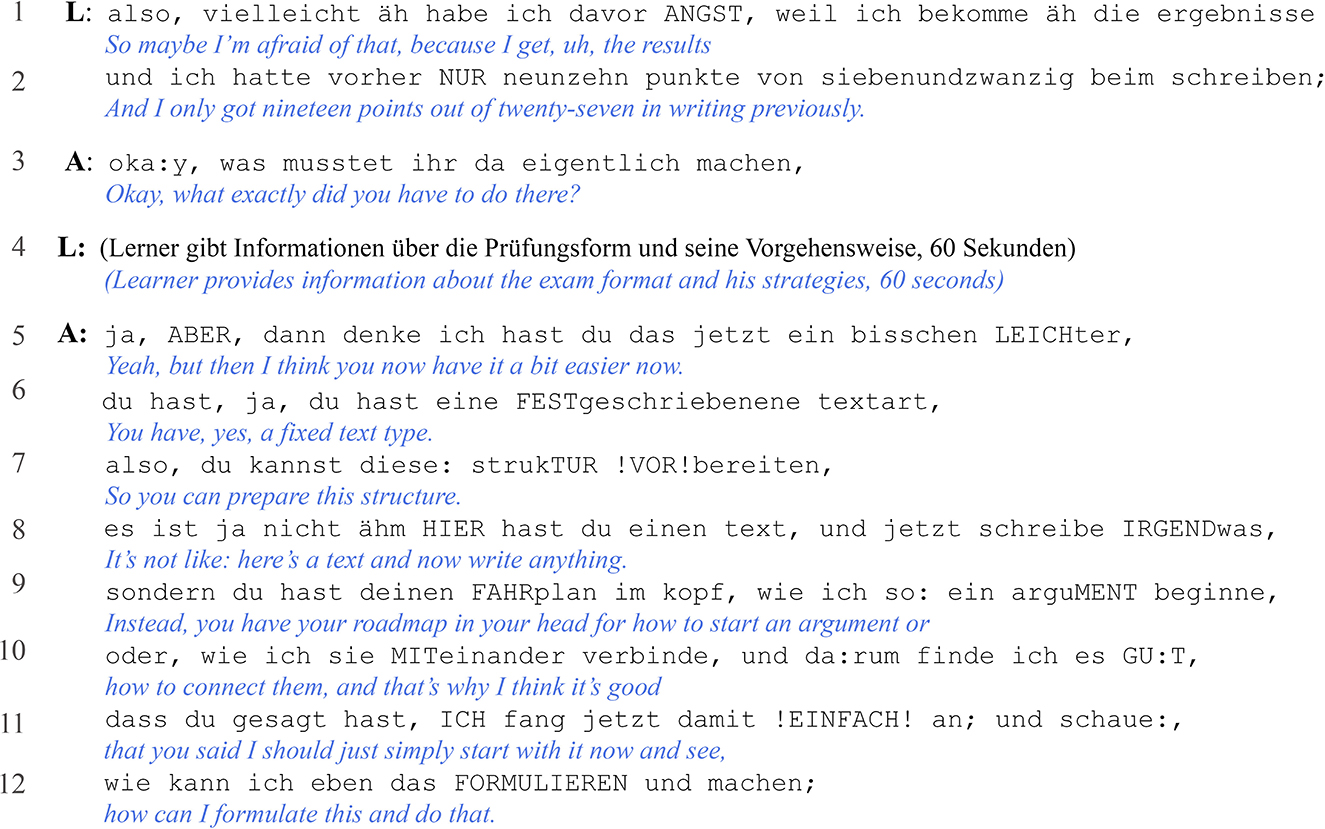

The L's renewed emotional disclosure in the third session (Example 5) conveys a sense of anticipatory anxiety related to achievement emotions in a test situation, emerging as a consequence of unmet self-efficacy following a previous unsuccessful attempt (lines 1–2). In response, A adopts a de-emotionalizing stance, posing a fact-oriented question about the exam format, displaying minimal emotional responsiveness (line 3, okay). This shifts the interactional focus away from the L's emotional experience and toward a solution-oriented contextual analysis. At the same time, the learner is epistemically upgraded by being positioned as the more knowledgeable. After L provides information about the exam, A proceeds with a sequence of post-hoc, emotionally supportive co-reasoning by positively framing the context, and emphasizing available resources and manageable steps in action (lines 5–12) to foster the learner's self-efficacy in approaching and solving the task and supporting reappraisal.