- Faculty of Education and Social Work, The University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand

Research over several years has found that “effective learners tend to monitor and regulate their own learning and, as a result, learn more and have greater academic success in school” (Andrade, 2010, p. 90). In New Zealand primary schools, the primary purpose of assessment and evaluation is to improve students’ learning and teachers’ teaching as both respond to the information it provides. To bring this purpose to fruition, teachers need to be educated to facilitate genuine engagement by learners in assessment processes; known in New Zealand as having assessment capability. In this study, we investigated to what extent, and how, teacher candidates learn to involve their students in formative assessment of their own work. Participants were a cohort of undergraduate, elementary school teacher candidates in a 3-year undergraduate program taught across three campuses at one university in New Zealand. Surveys and interviews were used to investigate assessment capability. Although the survey results suggested the teacher candidates may be developing such capability, the interviews indicated that assessment capability was indeed an outcome of the program. Our findings demonstrate that these teacher candidates understood the reasons for involving their students and are beginning to develop the capability to teach and use assessment in these ways. However, developing assessment capability was not straight forward, and the findings demonstrate that more could have been done to assist the teacher candidates in seeing and understanding how to implement such practices. Our data indicate that a productive approach would be to partner teacher candidates with assessment capable teachers and with university lecturers who likewise support and involve the teacher candidates in goal setting and monitoring their own learning to teach.

Introduction

In New Zealand elementary schools, the primary purpose of assessment is to improve students’ learning and teachers’ teaching. To bring this purpose to fruition, teachers need to be educated to facilitate genuine engagement by learners in assessment processes, known in New Zealand as having assessment capability. Following a contextual introduction to assessment purposes and structures in New Zealand elementary education, this article provides an introduction to the place of formative assessment in bringing forth self-regulation. Next, an argument for increasing the assessment capability of teacher candidates grounded in the relationship between assessment and teaching is made to set the scene for the investigation of teacher candidates’ preparedness to involve their students in classroom assessment processes.

The New Zealand Context

Unlike many other Western education jurisdictions where standardized, state and national tests, or assessments are required throughout schooling, there are no compulsory tests in New Zealand elementary schools. Instead, accountability is ensured through three main approaches:

• elementary schools (for children aged 5–12) use overall teacher judgments rated by teachers against a set of national standards (set out as criteria with exemplars) in literacy and numeracy to monitor progress of all their students twice yearly1;

• a government agency, the Education Review Office,2 monitors every school’s performance and quality on a regular 3- to 5-year cycle; and

• a light random sample of students in years 4 (8 years olds) and year 8 (12 years old) is surveyed in subjects across the curriculum3 and the results reported to the Ministry of Education and published.

Within this accountability framework, schools are self-governing (Wylie, 2012) and have the freedom and responsibility to choose how to interpret and implement the national curriculum4 and how to use assessment and reporting within the guidelines provided. The guidelines for assessment in the New Zealand Curriculum (Ministry of Education, 2007) focus clearly on the formative purposes of assessment, situating information for learning and teaching at the center of the system. While they articulate the need for valid and reliable information and an interlinked system with information used for a range of purposes including accountability, “the primary purpose of assessment is to improve students’ learning and teachers’ teaching as both student and teacher respond to the information it provides” (Ministry of Education, 2007, p. 39). The NZ Curriculum explains that assessment to inform learning and teaching “is best understood as an ongoing process that arises out of the interaction between teaching and learning” (ibid).

Much of this evidence is “of the moment”. Analysis and interpretation often takes place in the mind of the teacher, who then uses the insights gained to shape their actions as they continue to work with the students. (ibid)

These policies and guidelines emphasizing formative assessment have been supported in implementation over several decades in New Zealand through extensive professional development programs (Poskitt, 2005, 2014) and the provision of assessment tools that schools and teachers can use to monitor achievement and progress [for a range of these see Ministry of Education5 and New Zealand Council for Education Research (NZCER)6].

In 2009, an assessment review was commissioned by the New Zealand Ministry of Education and resulted in a report, Directions for Assessment in New Zealand: Developing students’ assessment capabilities (DANZ) (Absolum et al., 2009). While concurring that the New Zealand approach to assessment leans in the right direction, the DANZ report argued that most of the important assessment decisions still tend to be made by teachers for students and that while teachers do involve students in some assessments, these tend to be of an informal, low stakes nature. DANZ and other authors since (Flockton, 2012; Booth et al., 2014, 2016, for example) have argued that equipping students with self-regulated learning (SRL) strategies will require teachers to facilitate genuine engagement by learners in assessment processes. This is referred to as developing “assessment capability” (Absolum et al., 2009).

In addition to assessment literacy (Stiggins, 1991; Popham, 2009) and building assessment competency (Stiggins, 2010) in which student involvement is one key component, assessment capable teachers “have the curricular and pedagogical capability, and the motivation, to engender assessment capability in their students” (Absolum et al., 2009). The distinguishing element here is the “expectation that teachers will encourage their students to feel deeply accountable for their own progress, and support them to become motivated, effective, self-regulating learners” (Booth et al., 2014, p. 140) (emphasis in original). This way of teaching is infused with formative assessment but also demands new skills, knowledge, and attitudes from teachers. For example, the teacher must also be a self regulating learner with explicit metacognitive awareness of assessment processes, results, and purposes (Absolum et al., 2009). In New Zealand, assessment for learning has been interpreted and implemented in ways that include assessment literacy and competency but it appears challenging for teachers to implement the deep, student centered approach, which brings about SRL, envisaged as assessment capability (Dixon et al., 2011; Flockton, 2012).

SRL and Assessment Capability

Research over several years has found that “effective learners tend to monitor and regulate their own learning and, as a result, learn more and have greater academic success in school” (Andrade, 2010, p. 90). In fact, research and theory since the mid-1980s has clarified how SRL enables students to take control of their own learning, leading to improved academic achievement (Zimmerman, 2001; Alton-Lee, 2003; Clark, 2012). Numerous models of SRL based on different theoretical perspectives have been developed (Montalvo and Gonzalez Torres, 2004), but simply put, SRL is

an active, constructive process whereby learners set goals for their learning and then attempt to monitor, regulate, and control their cognition, motivation, and behavior, guided and constrained by their goals and the contextual features of the environment. (Pintrich, 2000, p. 453)

Within the self-regulation process, self-assessment is formative self-appraisal in which students review the quality of their own work, make judgments about how well it meets the criteria and goals, and make continuous efforts to revise it to match what they understand the stated goals to mean. Thus self-assessment, in this sense, is a process of self-monitoring and improvement rather than self-grading or marking (Andrade, 2010). Engaging students in self-assessment as part of engendering self-regulation is not necessarily a straightforward process however. At least two complex activities are interwoven within the self-assessment process: metacognitive monitoring and feedback (Eyers, 2014).

Stemming from the work of Flavell in the 1970s metacognition involves cognitive monitoring in which “the monitoring of cognitive enterprises proceeds through the actions of and interactions among metacognitive knowledge, metacognitive experiences, goals/tasks, and actions/strategies” (Flavell, 1979, p. 909); or as Gipps (1994) puts it “thinking about thinking… (including) a variety of self-awareness processes to help plan, monitor, orchestrate and control one’s own learning” (p. 24). Such monitoring is sometimes presented as a series of steps such as setting expectations, critiquing the work in light of such expectations and then revising to better meet those expectations. Hattie and Timperley (2007) presented these as questions for the learner: “where am I going? (what are the goals?), how am I going? (what progress is being made toward the goal?), and where to next? (what activities need to be undertaken to make progress toward the goal?)” (p. 86). In reality though, all of these steps take place continuously and overlap in a complex internal self-evaluation process.

As well as self-feedback produced through these metacognitive processes, self-regulating learners also need support and feedback from external sources such as their teachers, peers and others when their self-monitoring reveals a discrepancy between current and desired performance or achievement (Butler and Winne, 1995; Clark, 2012; Eyers, 2014; Andrade and Brown, 2016). Bransford et al. (2000) concur, arguing that “frequent feedback is critical: students need to monitor their understanding and actively evaluate their strategies and their current levels of understanding” (p. 78). Such formative feedback (Clark, 2012) is a critical aspect of scaffolding self-monitoring, an overarching principle that, according to Andrade and Brown (2016), is required to bring about useful student involvement in the assessment process. They argue from the research evidence that “high-quality, verifiable self-assessments are more likely when students are taught how to self-assess, discuss and agree on criteria, have experience with the subject [of their learning] and have opportunities to practice self assessment” (p. 327).

Formative assessment and feedback is, thus, critical to developing student self-regulation. In fact Clark (2012) argues

that formative assessment encapsulates SRL (self-regulated learning), and…that there exists a bi-directional dynamic between the goals of formative assessment (which fosters SRL among students) and the strategies deployed by self-regulated learners, (whose learning strategies are pursuant of formative assessment goals). (p. 17)

Formative assessment in New Zealand, however, is not commonly understood by teachers in the way described by Clark (2012) and others, such as Black and Wiliam (1998) as providing the conditions to develop self-regulating learners. Rather than a dynamic process “designed to continuously support teaching and learning by emphasizing the meta-cognitive skills and learning contexts required for SRL” (Clark, 2012, p. 13), formative assessment, and assessment for/as learning, are commonly interpreted by New Zealand teachers as techniques such as setting goals, sharing success criteria or using diagnostic assessment tools that will help them how to plan for next steps in teaching (Absolum et al., 2009). The DANZ report highlights the need for teachers to move beyond these practices to enable “all young people to be educated in ways that develop their capacity to assess their own learning” (Absolum et al., 2009, p. 5), naming this as assessment capability.

In order to provide the conditions for SRL, assessment capable teachers not only need to believe it is important but also need to know how to incorporate three key conditions (Sadler, 1989) into their teaching. That is, assessment capable teachers need to be able to: collaboratively communicate goals and standards to students so they understand what constitutes quality work in their context; provide substantive opportunities for students to evaluate the quality of the work they have produced and help them to develop the metacognitive skills to engage in these practices; and provide opportunities for students to modify their own work during its production [for further explication see Booth et al. (2014) and Booth et al. (2016)]. A key element in this process is formative feedback. Clark (2012) argues that formative feedback is a “key causal mechanism” (Clark, 2012, p. 33) in the development of self regulation. It is through interactive formative feedback that teachers and students (and others) can coconstruct shared expectations and mutually engage in coregulating the learning experience.

Lipnevich et al. (2016) review various models of formative feedback asking when, where and how it works. Bringing together the work of Kluger and DeNisi (1996), Hattie and Timperley (2007), Shute (2008), and others, they show the complexity and deep practical knowledge needed by teachers required for coregulating the learning experience in ways that are productive of SRL. Furthermore, Lipnevich et al. (2016) demonstrate that it is critical to go beyond teacher feedback in such models in order “to examine what occurs in the feedback/learning process between the time when the student/s receive the feedback and the time when the student takes action (or chooses not to)” (p. 176). In summary, learning to use assessment for/as learning and become an assessment capable teacher is a very challenging task.

One way to improve teachers’ assessment capability is to begin to build the necessary capacity during teacher preparation. For example, Andrade and Brown (2016), in their review of self assessment in the classroom see a need for teacher candidates to have experiences implementing student self-assessment practices and opportunities to reflect upon the effectiveness of these for different students. They also promote using such practices with teacher candidates in order that they can appreciate and experience them as learners themselves. Given this challenge, and the importance of teacher preparation, we move now to consider studies regarding teacher preparation in assessment.

Previous Studies Regarding Teacher Preparation for Assessment

In an era of assessment and accountability reform, where schools and students are increasingly subjected to testing and evaluation, and formative practices are also promoted, studies continue to reveal deficiencies in the assessment preparation of teachers (Campbell, 2013). In the US, studies have revealed that teacher candidates need enhanced preparation in assessment and evaluation including designing assessments related to valued outcomes, using assessment evidence to inform teaching and learning, using high quality evaluation practices, and informing students, their parents and other stakeholders about outcomes (Brookhart, 2001). Many teacher preparation programs and certification agencies do not require coursework in assessment (Campbell, 2013), and, especially in the US, teacher preparation focuses mostly on measurement aspects of assessment, requiring teacher candidates to understand and demonstrate techniques such as test and item construction (Cizek, 2010; Stiggins, 2010; Campbell, 2013; McMillan, 2013) and summative marking and grading (Barnes, 1985).

Internationally since 2000, as the emphasis in classroom assessment has shifted toward formative assessment (McMillan et al., 2002; Kane, 2006; Hill and Eyers, 2016) and include students participating in their own assessment (Brown and Harris, 2013; Earl, 2013; Andrade and Brown, 2016), research attention to teacher candidate learning of formative assessment has also begun to shift. Studies have reported programs that prepare teacher candidates to use assessment for multiple purposes, engage with the complex nature of classroom assessment, and be able to critique such practices in light of assessment purposes, principles, and philosophies (DeLuca and Klinger, 2010; Eyers, 2014; Smith et al., 2014). Even though there is strong evidence about the importance of classroom assessment, studies have reported that teacher candidate preparation has been less than adequate and that preservice assessment teaching (when it occurs) can also be diluted through teaching practice experiences and/or particular personal characteristics of the teacher candidates themselves (Campbell, 2013). Furthermore, when they begin teacher education, teacher candidates generally demonstrate negative emotions about assessment (Crossman, 2007; Smith et al., 2014) have conceptions of assessment that are from those of practicing teachers (Brown and Remesal, 2012; Chen and Brown, 2013) and while they might value the ideals of formative assessment they do not know how to implement it (Winterbottom et al., 2008).

Recently though, studies have begun to tackle how teacher candidates learn about, and to enact, formative assessment (for example, Buck et al., 2010; Eyers, 2014; Smith et al., 2014). In a review of this literature (Hill and Eyers, 2016) four main influences were found: the teacher candidate conceptions that underpin such learning (for example, Brown, 2011; Brown and Remesal, 2012); the relationship between preservice assessment teaching and teacher candidate learning (for example, Buck et al., 2010; Siegel and Wissehr, 2011; DeLuca et al., 2012); the practical use by teacher candidates of assessment in classrooms during preparation (Graham, 2005; DeLuca and Klinger, 2010; Nolen et al., 2011; and others); and other factors such as personal dimensions (Eyers, 2014; Jiang, 2015), layered contexts (Nolen et al., 2011; Jiang, 2015) and broader policy and societal issues (Smith et al., 2014). Few, however, appear to have investigated how these aspects influence teacher candidates’ assessment learning in relation to beliefs and formative practices that encourage student self-regulation.

Assessment education is included in the teacher education program that is the focus of this article. In the second year of the 3-year elementary school undergraduate program, teacher candidates complete a course focused on classroom assessment. The semester long course includes a focus on summative assessment and testing, an introduction to common New Zealand standardized tests and diagnostic tools, formative assessment and feedback strategies, and processes for involving students in goal setting, peer, and self-assessment. Throughout the 3-year program, there are 15 weeks of teaching practice placements (practicum) where the teacher candidates work in classrooms for extended periods of time alongside mentor teachers. They spend 2 weeks in the first year, 5 weeks in the second year, and 10 weeks in the final year in classroom settings teaching alongside the classroom teacher. The third-year practicum is a significant opportunity to put what they have learnt into practice. It begins with a 3-week placement when school opens at the beginning of the school year and then continues later in the year in the same classroom for 7 contiguous weeks. During this time, the teacher candidates have full responsibility for running and teaching the class for a continuous 10-day period. We carried out this investigation to understand the extent to which our teacher candidates were becoming assessment capable through this program, and, perhaps more importantly, how the program influenced their assessment learning over their time in the program.

Methodology

In order to investigate how teacher candidates learn to become assessment capable teachers, we asked: To what extent, and how, do teacher candidates learn to involve their students in formative evaluation of their own work, during teacher preparation? To answer this question we drew from three existing data sources gathered about the assessment learning of one cohort of these elementary school teacher candidates. We looked for evidence that indicated that the teacher candidates understood how the teacher should involve or encourage the students in assessing their own learning and/or set personal goals and/or use self/peer assessment; that is, demonstrations of their developing assessment capability. Furthermore, we interviewed a group of teacher candidates and their assessment teacher educator to understand the sources of influence on teacher candidates’ assessment capability learning in order that we could enhance these in future iterations of the program.

Participants

Participants were a cohort of undergraduate, elementary school teacher candidates in a 3-year undergraduate program taught across three campuses at one university in New Zealand. These participants were a subset of a larger cohort (n = 720) across four universities who completed the “Beliefs about Assessment” questionnaire (Hill et al., 2013) at the beginning of the program in 2010. In the university that is the focus of this study, 224 of 250 teacher candidates entering the program agreed to participate. The participants in this cohort varied at entry in age (16 years to 58 years of age, mean = 23.72 years). Sixteen percent were male, and 84% female. Using the New Zealand census ethnicity categories, the cohort comprised 64% Pakeha/NZ European; 4% Māori; 4.5% Pasifika; 6% Asian; and 21.5% “other.” A teacher educator (Bev) was the other participant. With 16 years experience as an elementary school teacher and deputy principal, Bev has also been a program leader for teacher education. At the time of this study she had taught the teacher candidates in this cohort on the compulsory second year undergraduate classroom assessment course.

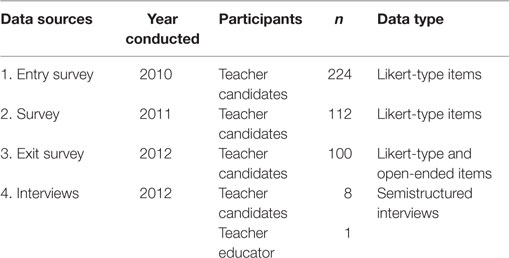

Data Sources and Procedures

Table 1 describes the data sources that contributed information about the teacher candidates’ developing assessment capability. Each data source and its associated analysis processes are described below.

Surveys

As noted above, consenting teacher candidates completed the “Beliefs about Assessment” questionnaire (Hill et al., 2013) when they entered the teacher education program and at the end of their second and third years in the program. The Beliefs about Assessment questionnaire comprised 46 Likert-type items and five open-ended items, which had been piloted with a sample of teacher candidates and found to yield sufficient variability and to not be redundant (Hill et al., 2013). The survey was administered at four universities in New Zealand (n = 720). The data in the findings about factor analyses are from the larger study involving all four universities, including the teacher candidates at the focus university; the data about changes in item responses are from teacher candidates at the focus university within the larger study, from which the interview participants were drawn.

The 46 Likert-type items in the survey were derived from literature on teacher candidates’ assessment conceptions and from the considerable experience of the research team (Hill et al., 2013). Items were posed as statements, and the teacher candidates were asked to indicate the degree to which they agreed, or not, with each statement (strongly disagree, disagree, agree, and strongly agree). A “don’t know” option was provided, but these data were coded as “missing” for the statistical analysis.

A factor analysis of the 46 items was performed on the full four-university data set each year that the survey was administered (2010–2012). An oblimin rotation was used, as the items were assumed not to be orthogonal.

Each university’s data was then analyzed separately to look for significant changes in agreement over the teacher preparation period. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) procedure was used to analyze these data, with year (2010–2012) as the independent variable, and responses to the items on the four-point scale as the dependent variables. A Bonferrroni adjustment was applied to reduce the likelihood of Type 1 errors arising from multiple comparisons. A Scheffe post hoc procedure provided further information about the nature of significant changes in response to particular items.

The open-ended questions at the end of the third year asked students to describe what they thought assessment was, and what it might look like for students and teachers in classrooms. For this study, the teacher candidates’ responses to the open ended questions were analyzed thematically to see if they included statements about assessment capability: how teachers should encourage their students to assess their own learning, set personal goals or participate in self or peer assessment. This was a deductive analysis, seeking evidence for the construct of assessment capability in the teacher candidates’ thinking about assessment, rather than an exhaustive analysis of all the teacher candidates’ responses. The aim of the analysis was to see if the teacher candidates’ written responses provided additional insight into their understanding of assessment capability, beyond the changes seen in the Likert-type items on the survey. Author 2 conducted the analysis. Author 1 then analyzed randomly selected responses to check the inter-rater consistency of coding decisions (in essence, were the responses relevant to assessment capability?). There were very few discrepancies and any found were resolved by consensus through discussion.

Interviews with Teacher Candidates

In-depth individual semistructured interviews were held with eight teacher candidates on four occasions throughout the final year of their program: at the beginning of the academic year; prior to their final 10-week school practicum; immediately following their practicum; and, at the end of the university year (see Appendix for the interview questions). The teacher candidates brought examples of assessment artifacts, tools or documents with them to the interview and were asked to explain how these had influenced their assessment beliefs, understandings, and practices. They were also asked to reflect on how university coursework and their practicum experiences related to assessment and, in the final interview, how confident they were to use assessment as beginning teachers.

The interviews were transcribed and uploaded to NVivo for computer assisted analysis. While the sequential interviews provided some information about change during the third year of the program, there did not appear to be any patterns of change across the year identifiable across the group. Rather, the interviews provided multiple opportunities to examine how different experiences had impacted their assessment understandings and beliefs. Therefore, in this article we focus on looking for evidence about teacher candidates’ knowledge and experiences to do with involving learners in their own assessment and exploring how their assessment capability learning occurred during the program. In particular, we remained alert for the influences reported in previous studies and looked for any further influences that might be operating. Thus, we conducted an inductive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2013) initially undertaking line by line coding of the transcripts and assigning codes related to the experiences teacher candidates associated with any mention of involving students in assessment. The purpose of the second cycle of coding was to condense the initial codes and to map these into categories that suggested the contexts where this type of learning took place. These categories have been used to organize the findings from the interview analysis. Trustworthiness of the emerging findings was enhanced through returning transcripts to the participants for checking and emendation and by conducting inter-rater consistency checks on the coding [see Eyers (2014), for more details].

Interviews with Teacher Educator

A semistructured interview was conducted with the teacher educator responsible for teaching the assessment course to the teacher candidates interviewed in the study. Among other aspects, the interview investigated how assessment was modeled and taught, including the assignments and feedback given which provided information about the program and the role of assessment preparation within it. Analysis took place after the teacher candidates’ interviews had been analyzed using a deductive analysis to look for ways in which the teacher educator’s responses aligned (or not) with the responses of the teacher candidates.

Findings

To answer the first part of the research question, the extent to which the teacher candidates appeared to understand the importance of involving their students in their own assessment, we focus on responses to the survey. We then turn to the second aspect, understanding how the teacher candidates learnt about this aspect through their program, through exploring the findings from the interviews supported by the evidence they brought to the interviews (for example, course booklets) and data from the teacher educator interview.

Extent of Change in Beliefs about Assessment Capability

The survey yielded two sources of evidence of teacher candidates’ learning about assessment capability in students. The first was a shift in the factor structure in the four-university data set; the second was statistically significant changes in responses by students in the focus university to four items that directly mention students’ assessment capability, that is, believing students should be involved in formative evaluation of their own work.

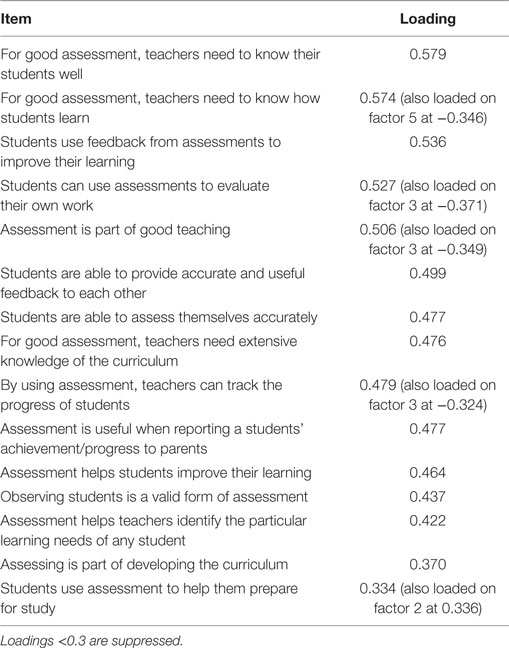

The annual factor analysis revealed a shift in patterns of response to the survey as the teacher candidates moved through teacher preparation. The results of this analysis are reported fully elsewhere (Hill et al., 2013). In this article, we present the emergence of a factor related to assessment capability in the third and final year of the survey as evidence of a growing awareness amongst the teacher candidates of assessment capability as an idea. The factor that emerged in the 2012 administration accounted for 12.93% of the variance and was the largest factor present in the analysis. It included the 15 items listed in Table 2 below. It appears from the emergence of this factor that the teacher candidates have come to see assessment capability in teacher and students as a linked set of ideas. The factor includes all the items relating to student assessment, along with items related to teacher actions that support the growth of assessment capability in students.

Table 2. Teachers and children both having a role in assessment for learning: emergent assessment capability factor, 2012.

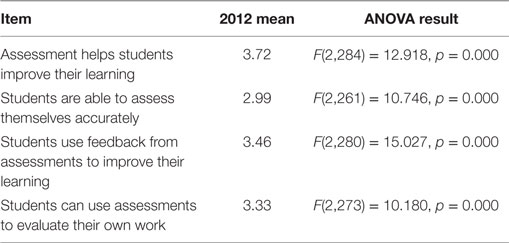

To look more closely at assessment capability regarding students, we turned to the responses of our own university’s teacher candidates. The 46-item survey contained five items that were directly related to teacher candidates’ views of students involvement in assessment. There was a statistically significant shift toward greater agreement with four of the items over the 3 years of teacher education. Table 3 shows the mean response to each of the four items on the final administration of the questionnaire and the ANOVA results for the four items.

While the shifts suggest a greater agreement with items to do with assessment capability, the amount of agreement differs among the items. The mean agreement with “students are able to assess themselves accurately” is not quite at “agree.” The most strongly endorsed item is “assessment helps students improve their learning,” which is closest to a mean of “strongly agree.”

Agreement with the fifth item, “students are able to provide accurate and useful feedback to each other,” did not change significantly over the 3 years of teacher preparation [F(2,263) = 0.642, p = 0.527]. The mean agreement in 2010 was 3.01 (already at agree) and this remained the same 2 years later (2012 mean—3.11).

The Scheffe post hoc procedure helped us to identify where the shift occurred across the 3 years. For three of the items (Students are able to assess themselves accurately, students use feedback from assessments to improve their learning and students can use assessments to evaluate their own work) the shift occurred between the first and second years of the teacher education program. Responses to the fourth item (Assessment helps students improve their learning) changed between the second and third years of the teacher education program.

However, in the open-ended qualitative items in the survey conducted at the end of the program where teacher candidates were asked open-ended questions about why they thought assessment was important, only 6 of the 215 teacher candidates provided responses that indicated the teacher should involve or encourage the students in assessing their own learning and/or set personal goals and/or use self/peer assessment. Quotations from four of the six respondents in the survey exemplify that these teacher candidates believed assessment: “tells the student how they are going and where to next”; “gives the teacher and students understanding of progress in learning”; “for students to improve their learning”; and “also students like to know how they can improve themselves.”

Thus, the survey results, while suggestive that there might be a change toward holding beliefs that involving students in their own assessment is a productive practice, did not provide a great deal of evidence about teacher candidates knowledge, understanding or learning about involving students in their own assessment.

Qualitative Changes in Learning about Assessment Capability

In contrast to the findings from the surveys, the eight teacher candidates who volunteered to be interviewed in-depth four times during their final year of the program demonstrated that they understood a great deal about using formative assessment for self-regulation and also explained much about how they had come to learn about this. As noted in the Methods section, we don’t differentiate between entry and exit views here, due to the fact that all of the interviews took place throughout the final year of the program and often involved teacher candidates drawing on experiences throughout the program to talk about their developing ideas. Thus, we bring together evidence of teacher candidate learning about their developing assessment capability from all four interviews in this section.

All eight teacher candidates talked about the benefits and uses of formative assessment. Six of them expressed positive views about the benefits of including students in their own assessment and described how they would incorporate it into their own practice. For example, toward the end of the program in the fourth interview, Carmen explained how she viewed the importance of building assessment capability with students.

I think assessment is also important for children. I think they need to see that they’ve made progress. By developing reflective practices in children where they can assess their own work I think that that is a really important part of being able to equip children to deal with all elements of life, not only just future study. (Int. 4)

These teacher candidates talked about involving students in goal setting, coconstructing criteria that they could use to know how well they were meeting these goals, and self and peer assessment.

Self and peer assessment, and teaching how to do that, is really effective. It gives them ownership and power. It is an empowering skill for them to have. I think you have to make the effort and I am not saying that in my class it is going to go well straight away but it is something that would be a focus for me. I think you can learn a lot from your peers. (Katelyn, Int. 4)

Assessment is important because it gives the student feedback so the students know where they are at so they can take responsibility for their learning as well. If they know what their achievement is then with the help of the teacher they know where to go next so they can start making goals for themselves. The student can take part in their own assessment, self-assessment. They can help with peer assessment, which is very helpful in the classroom. (Scarlett, Int. 1)

Thus, the teacher candidates provided evidence that they had positive perspectives about involving learners in their own assessment, knew that self and peer assessment assists students to become self regulating learners and saw value in assessment being a process shared with students rather than only the responsibility of the teacher. As the teacher candidates who were interviewed were volunteers and not selected because they might have particular views, we suspect that understanding about this aspect of formative assessment may have been more widespread across the cohort than the survey suggested but not picked up in the survey due to the nature of the questions.

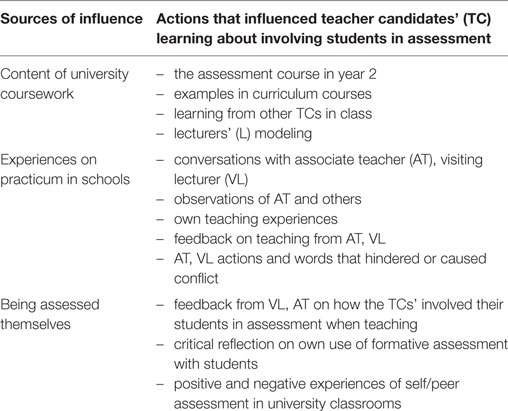

Influences on the Teacher Candidates’ Assessment Capability Learning

Information about the reasons for the shift toward developing assessment capability was also provided by the teacher candidates in the one to one interviews. The inductive analysis suggested three main sources (categories) of influence: content of their university courses; their experiences regarding assessment on practicum; and, learning about being involved in assessment as they experienced this themselves. Within each category, several different ways in which they were influenced were mentioned by the teacher candidates and the teacher educator (see Table 4). Each source of influence is described in more detail next drawing on direct quotations where appropriate to illustrate these influences.

Assessment Capability Learning through University Courses

The teacher candidates reported that they had learnt about encouraging students to become self regulating autonomous learners in at least three of their university courses and their course assignments. For example, one teacher educator used the self assessment strategies she was teaching about in her own classes, and, as one teacher candidate said

I found that was really quite helpful. A lot of us learn through that collaboration, that talking together. You are not just sitting down with a whole lot of writing or reading material. It is nutting out ideas, nutting out what it looks like, what it means to us. (Abigail, Int. 1)

Another of the teacher candidates commented how she had noticed how teacher educators had encouraged teacher candidates to become involved in assessing their own learning after being involved in the assessment course early in the second year of the program.

I noticed that lecturers were asking us questions that required a bit more critical thinking on our part, a lot of open-ended questions where we would dialogue in groups as opposed to the lecturer just up there feeding us information …. [the lecturer] was coming around observing, listening to our discussions then she would go back and say “I actually picked up on what this group said, let’s go back to that, their understanding of that.” …. When we would question and clarify in the classroom a lecturer would say “oh not quite, what does somebody else think?” and open it up for discussion. So I did see formative assessment happening, the whole scaffolding of the learning in that environment. (Rasela, Int. 1)

Rasela particularly noted how feedback from her assessment course lecturer impacted her self-monitoring in that course.

I was used to being an A-grade student then I got my first C + and then I needed to know why. Through the process of getting effective feedback and feed forward I was able to use that assignment and lift my second assignment to an A. …She (the lecturer) was honest in her feedback. I’d always written the way I had written in that assignment and I never got pulled up for incorrect APA referencing, (or for the) coherency of my structure. Through that assessment I was able to develop my academic writing. (Rasela, Int. 1).

Bev, the teacher educator responsible for teaching the assessment course, talked about purposefully using strategies to encourage self monitoring and evaluation among the teacher candidates.

What we are also modeling is assessment as learning. We are trying to get them using it to monitor their own progress. Sometimes they don’t get it. So where their assignments are coming in and they have clearly missed the mark, I always try and meet with them individually to talk to them. I will say “have you read the feedback?” and they will say “no, I just couldn’t face it.” I will say “let’s just have a look at what you’ve done and what the suggestions are.” I think if they know what to do, they’ll do it. Sometimes it is just too much information so then I will show them an exemplar and say “can you find these features?” and often they will say “oh, now I get it! It is often so much simpler than I was trying to show.” This is in one-on-one conferencing. (Bev, Teacher Educator)

One of the eight teacher candidates believed this type of modeling could happen even more across all courses.

For every course say, “this is how we are going to assess you because this is how we want you to assess children.”… Even if they said to us, “we are doing this because we want you to see how it works” and they could each model a different part of it… “this is your success criteria” and get us to build our own success criteria like they want us to do in class (on practicum). If a 10% course assignment was done like that you would get a good view of it. (Penny, Int. 1).

Learning about Assessment Capability while on Practicum in School Classrooms

As well as talking about how they learnt about formative assessment and self regulation at university, teacher candidates also described how they were involving students while they were teaching on practicum in local schools. Carmen gave several examples.

So for me there were a number of ways. The first way was obviously formative assessment, so using the thumbs up/thumbs down approach. I also had a self-reflection sheet at the end of the period and we had success criteria that (the students) had to go and look at and mark off that they had met the criteria. We were doing speeches so there was stuff around the introduction, body and conclusion, and there was a self-assessment that they did right at the end. I also did peer assessment for children to reflect on not only their own learning but around recognising how other people had done work then going back and using elements of that if they wanted to within their own work …. I used questionnaires with the students. I used self-assessment opportunities so every week where they actually link into competencies or the school’s virtues. Peer assessment was another important aspect of my practice. (Carmen, Int. 3)

The assessment course teacher educator agreed that being on practicum enabled the teacher candidates to practice using assessments in authentic contexts. Prior to the past 7 weeks of practicum, Scarlett noted that

I will be assessing through observation, listening to their conversations, asking them questions to find out if they understand this, have they grasped the idea. I will be assessing them against the success criteria that I have got. … I think there is room for self-assessment. It would help me see what they think of their work, where they think they are at and what they think they need to improve on … and peer assessment as well. (Scarlett, Int. 2)

Following this practicum the teacher candidates described having had a focus on formative feedback and self and peer evaluation as ways to move students toward taking responsibility for their own assessment and learning.

By using formative assessment during the learning and also looking at the work and giving verbal and written feedback. With a lot of their work, with our learning pathways, I would put a post-it note with some detailed feedback and hand it back to them to read it then get them to conference with me quickly about their thoughts on my comments, one-on-one. …We always set success criteria that are left on the board. I would always have on the whiteboard ‘self-check, peer-check, I’m the last person you come to’, to try and create that independent learner focus. (Angela, Int. 3)

There were inconsistencies, however, between schools in the extent to which students were supported to become self regulating. In some schools the emphasis was on teachers as assessors and in only one did the teacher candidate describe how teachers were encouraging students to take some responsibility for their learning and assessment was embedded in their philosophy and practice.

Yesterday all of my class were working on their maths goals. They were able to set these themselves. …I think (these) teachers are trying to create more independent learners, which is really new to me. They can log on from home and go and check where they are at with their goals. (Angela, Int. 1)

In contrast, Scarlett demonstrated that she believed in involving her students in their own evaluation but was restricted by her practicum school from carrying out such approaches.

I would like to have had the kids to set the success criteria themselves. Rather than me saying “this is what I want to see, this is what you have to achieve”, I would rather have the kids say “well this is what I think a good advertisement would look like.” …I would like to have the kids have more say in the assessment and that way they would have a better understanding of what is expected. (Scarlett, Int. 3)

Thus not only was there an inconsistent focus on assessment capability within courses at the university, there were also inconsistencies in practices across the schools, and among the lecturers evaluating the teacher candidates’ practice.

Learning about Assessment Capability while Being Assessed Themselves

The third context where teacher candidates learned about involving students in their own assessment was in being assessed themselves. First, being assessed by university lecturers while on practicum had reinforced student involvement in the assessment process. An example of this was given by one teacher candidate.

After the observation, she (the lecturer) said “it was really good to see how you kept bringing the students back to the WALT (‘we are learning to’ lesson goal), reinforcing the WALT and making sure they were very aware of their learning aims or outcomes. That was really really good to see. You were really very explicit in making sure the students were always focused on their learning, why they are learning this.” (Rasela, Int. 3)

Unfortunately however, visiting university lecturers did not all have such a focus on formative evaluation. In fact some did not provide feedback on assessment practices at all.

No, there were no discussions around assessment. She looked in my practicum folder. (Angela, Int. 3)

He just said my file was superb but nothing specific about assessment. I don’t remember anything directly about assessment. (Carmen, Int. 3)

The teacher candidates also gave examples of how they self-assessed themselves against the criteria for passing their practicum. Some of these criteria were related to assessment understanding and practice, although none specifically about involving students in their own assessment. Bringing these various experiences together, one teacher candidate showed how her own metacognitive approach to learning to teach was shaping her understanding and use of assessment, including her capabilities to involve her students in their own assessment.

I feel quite confident in assessment. … I feel really confident assessing them formatively. If I am having a conversation with a child and working one to one, I feel confident in assessing their understanding. …I still feel I’ve got lots to learn and I think I am going to do most of that learning through trial and error. … So if I’m teaching a lesson and then I decide that these (children) are not grasping it, its is a little bit too advanced for them, I would step back and take it down a notch, I will be monitoring and using the information to improve my teaching. You have to be flexible, don’t you? I am still learning so I am going to be changing what I am doing all the time. …There is a lot to learn but I don’t feel that I am going in “unarmed.” (Scarlett, Int. 4).

One of the teacher candidates provided a great deal of detail about how and why participating in a peer assessment activity at university had made her carefully consider involving students in their own assessment.

We were put into little groups (during university classes). There were four of us and then we each took it in turns to present. We had a set of criteria that we had to judge or mark. … I had a huge problem with the whole thing. It was that I was not qualified to enough to be able to do that properly. I can give you feedback but I don’t feel comfortable about actually giving you a mark.

I think to me peer assessment is a very powerful tool in the classroom but I just would use it differently. … What should have happened is that people could have done their presentations and we could have then provided feedback, not given a mark, which would then be recorded for the lecturer to look at. Those people then take their scripts away. They could consider the feedback that has been given to them. They could make modifications to their work and two or three days later they re-submit their scripts or final documentation. To me that would have been powerful. Much, much better because you’ve taken the feedback, you’ve looked at where it can take you next, you’ve incorporated that into your learning and at the end of the day it goes back to somebody who has the knowledge and know-all to actually create that final big-stakes stuff. It is big stakes. (Carmen, Int. 2)

This experience led Carmen to consider a great deal about her assessment learning and how it might influence her further when teaching on practicum and as a teacher. Interestingly, despite the incident being in conflict with her knowledge about appropriate peer evaluation practice, Carmen deepened her understanding of involving students in their own assessment through this experience. While the teacher educator may not have intended the activity to be so problematic, Carmen’s account suggests that learning about, and to use, self and peer assessment is complex and intertwined within the many experiences teacher candidates encounter during teacher preparation. In fact, all eight teacher candidates gave examples of conflicts and tensions noted in their assessment learning that made them reflect and reconsider theory and practice.

Discussion

The factor analysis from the larger sample, of which this cohort of teacher candidates was a part, suggested a shift toward believing that teachers and their students all have a role in assessment for learning. Furthermore, there were statistically significant shifts in responses to four of the five items related to assessment capability within the survey. Very few responses to the open ended questions, however, indicated increasing assessment capability. We believe this was due to the limited number of Likert-type items related to assessment capability and the very open-ended nature of the qualitative questions. In future surveys of teacher candidate learning about formative assessment it seems important to focus more specifically on the beliefs and practices connected with involving students in their own assessment. This recommendation is supported by the findings from the in-depth interviews which demonstrate a great deal of learning in this aspect of assessment. Given that the eight students volunteered and were not selected because they showed any particular preference for, or understanding of, involving their students in formative assessment, the interview findings demonstrate that far from being something that only experienced teachers are aware and can cope with (Andrade, 2010), involving students in their own assessment is considered and practiced by teacher candidates when the conditions encourage them to do so. In particular, the interview evidence demonstrates that when there is a focus on formative assessment integrated within the teaching and learning context, and an emphasis on involving students in assessment of their own learning, teacher candidates can and do shift their beliefs and practices in this direction.

In summary, the teacher candidates interviewed in this study demonstrated that they: realized involving students in self assessment is important; that students can evaluate their own work; that this is an important life skill; and, that they learnt ways to immerse students in goal setting, co-constructing assessment criteria, and working by themselves, with peers and with teachers to evaluate and access feedback for improvement. These views and practices are in line with Stiggins (2010) conceptions of assessment literacy and with assessment capability (Absolum et al., 2009; Booth et al., 2014). Even though developing this capability is challenging (Andrade, 2010; Flockton, 2012), our findings demonstrate that these teacher candidates understood the reasons for involving their students and are beginning to develop the capability to teach and use assessment in these ways.

The teacher candidates, however, demonstrated through their responses that learning to include students in formative assessment was not straight forward and that more could have been done to assist them in seeing and understanding how to implement such practices. In line with previous studies (DeLuca et al., 2012; Hill et al., 2013), having a classroom assessment course that teaches about such practices is important as well as intertwining formative assessment learning within other courses (Smith et al., 2014). Our participants confirmed that learning about including students in assessment by being included in it themselves in their university courses was helpful and, as evidenced, suggested that doing this more often in all courses would be helpful to their learning. They also indicated that even when their experiences as learners or their classroom observations ran counter to what they were being taught to do, these experiences provided food for thought, expanding and developing their ideas about formative assessment.

Consistent with previous studies (DeLuca and Klinger, 2010; Siegel and Wissehr, 2011; DeLuca et al., 2012; Hill et al., 2013) this study indicates that having a university course or courses focused on assessment was beneficial in terms of teacher candidate formative assessment learning. In particular, this study confirms the findings of Buck et al. (2010) that making formative practices explicit to teacher candidates by using them in university classrooms served to mitigate the tendency to use more traditional assessments such as tests but goes further in demonstrating that these teacher candidates understood and advocated for involving students as partners in the assessment process.

Practicum experiences, too, were important in extending learning about formative assessment and its use to develop SRL. Aligned with the findings of surveys (Mertler, 2003; DeLuca and Klinger, 2010; Alkharusi et al., 2011) and more in depth studies (Graham, 2005; Buck et al., 2010; Nolen et al., 2011; Taber et al., 2011; Eyers, 2014), experiencing and using assessment on practicum reinforced and extended assessment capability. Unfortunately, but perhaps predictably, the experiences practicum offered were inconsistent in the extent to which they enabled the teacher candidates to actually involve students as partners in the assessment process. As pointed out by DeLuca and Klinger (2010), because many teachers do not involve their students in formative self evaluation, teacher candidates “will be exposed to idiosyncratic practices leading to inconsistent knowledge, practices and philosophies as a result” (p. 434). This, therefore, highlights the importance of providing a sufficient amount, and consistency, of formative assessment for self-regulation across the teacher preparation program. As our findings demonstrate, the teacher candidates experienced including students in different ways in different settings and needed a strong theoretical framework and good role models so they could reflect on and critique less-than-optimal assessment occurrences. It is certainly not enough to leave the learning of this aspect of formative assessment to the hope that they will learn about it on practicum. In fact, our data indicates that an optimal approach would be to partner teacher candidates with assessment capable teachers who involve their students in formative assessment and with visiting university lecturers who likewise support and involve the teacher candidates in goal setting and monitoring their own learning to teach.

Despite tensions and even conflicts between theory and practice, much of what the teacher candidates learnt about in university and experienced in school classrooms was aligned. Due, perhaps, to a lack of national testing, the guidelines in the New Zealand Curriculum and provision of a range of standard diagnostic assessment tools which schools can access freely, elementary schools and teachers tend to approach classroom assessment mostly in formative ways. The teacher candidates spoke of observing and implementing ways to involve learners in SRL through formative assessment practices in schools, consolidating what they had been learning about in their university courses. However, this was the case for some more than others. In line with this finding, studies of the assessment practices of NZ teachers have reported that despite professional development in SRL strategies, not all teachers involve their students in formative assessment (for example, Dixon et al., 2011). This suggests the importance of including such practices in their university course work and assignments, as well as more careful placement of teacher candidates in schools and classrooms where they will observe assessment capable teachers and experience students being involved in formative assessment.

Conclusion

The findings of this investigation indicate that learning to involve students as partners in the formative assessment process is neither straightforward nor predictable. The experiences of the interview participants demonstrate the complex intertwining of conceptions, experiences and opportunities that form teacher candidates’ knowledge and understanding of, and commitment to, engaging their students in formative assessment. Negative experiences, where self assessment is not used or is discouraged, as well as positive experiences in both university and classroom settings, appear to combine in unpredictable ways with beliefs and past experiences to inform individual teacher candidates’ beliefs and practice.

The findings from this cohort do indicate that with enough of the right conditions in place, teacher candidates can graduate from teacher preparation programs with a great deal of understanding about, and a mindset for, involving students in ways known to be productive of SRL. Further investigation, through observations of teacher candidates in practicum settings and in their own classrooms after they graduate, is needed however, to see how they include such approaches in their practice. Surveys have not, to date, produced reliable findings about such teacher practices, and interviews, while effective, are not efficient for giving findings about the practices of large numbers of teacher candidates, and they cannot tell us what they actually do in practice. To investigate teacher candidates’ and new teachers’ actual assessment capability, observational studies are needed. In preparation for this we are marshaling descriptions of assessment capability that can be used by observers, themselves familiar with such practice, to extend our investigation of assessment capability learning. Such instruments might also be used by teacher candidates and teachers themselves in order to monitor their own assessment capability development.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations and guidelines of the University of Auckland Human Participants’ Ethics Committee. All participants gave written informed consent in accordance with the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee. The protocol was approved by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee.

Author Contributions

MH wrote and revised the article and led the project that included the survey reported in the article. FE assisted with the quant analysis, reviewed, and revised the article. Both MH and FE supervised the doctoral thesis of GE whose qualitative data is incorporated in the article. GE reviewed and revised parts of the article.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding

Part of this investigation was funded by the New Zealand Teaching and Learning Research Initiative Project No. 9278.

Footnotes

References

Absolum, M., Flockton, L., Hattie, J., Hipkins, R., and Reid, I. (2009). Directions for Assessment in New Zealand: Developing Students’ Assessment Capabilities. Available at: http://assessment.tki.org.nz/Media/Files/Directions-for-Assessment-in-New-Zealand

Alkharusi, H., Kazem, A. M., and Al-Musawai, A. (2011). Knowledge, skills, and attitudes of preservice and inservice teachers in educational assessment. Asia Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 39, 113–123. doi: 10.1080/1359866X.2011.560649

Alton-Lee, A. (2003). Quality Teaching for Diverse Students in Schooling: Best Evidence Synthesis. Wellington, NZ: Ministry of Education.

Andrade, H. L. (2010). “Students as the definitive source of formative assessment: academic self-assessment and the self-regulation of learning,” in Handbook of Formative Assessment, eds H. L. Andrade and G. J. Cizek (New York, NY: Routledge), 90–105.

Andrade, H. L., and Brown, G. T. L. (2016). “Student self-assessment in the classroom,” in The Handbook of Human and Social Conditions in Assessment, eds G. T. L. Brown and L. R. Harris (New York: Routledge), 319–334.

Barnes, S. (1985). A study of classroom pupil evaluation: the missing link in teacher education. J. Teach. Educ. 36, 46–49. doi:10.1177/002248718503600412

Black, P., and Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assess. Educ. 5, 7–74. doi:10.1080/0969595980050102

Booth, B., Dixon, H., and Hill, M. F. (2016). Assessment capability for New Zealand teachers and students: challenging but possible. SET: Res. Inform. Teach. 2, 28–35. doi:10.18296/set.0043

Booth, B., Hill, M. F., and Dixon, H. (2014). The assessment capable teacher: are we all on the same page? Assess. Matters 6, 137–157.

Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., and Cocking, R. R. (eds) (2000). How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2013). Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. London: SAGE.

Brookhart, S. M. (2001). The “standards” and classroom assessment research. Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education, Dallas, TX. ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED451189

Brown, G. T. L. (2011). “New Zealand prospective teacher conceptions of assessment and academic performance: neither student nor practising teacher,” in Democratic Access to Education, eds R. Kahn, J. C. Mc Dermott, and A. Akimjak (Los Angeles, CA: Antioch University Los Angeles, Department of Education), 119–132.

Brown, G. T. L., and Harris, L. (2013). “Student self-assessment,” in Sage Handbook of Research on Classroom Assessment, ed. J. H. McMillan (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE), 367–393.

Brown, G. T. L., and Remesal, A. (2012). Prospective teachers’ conceptions of assessment: a cross-cultural comparison. Span. J. Psychol. 15, 75–89. doi:10.5209/rev_SJOP.2012.v15.n1.37286

Buck, G. A., Trauth-Nare, A., and Kaftan, J. (2010). Making formative assessment discernable to pre-service teachers of science. J. Res. Sci. Educ. 47, 402–421. doi:10.1002/tea.20344

Butler, D. L., and Winne, P. H. (1995). Feedback and self-regulated learning: a theoretical synthesis. Rev. Educ. Res. 65, 245–281. doi:10.3102/00346543065003245

Campbell, C. (2013). “Research on teacher competency in classroom assessment,” in Sage handbook of Research on Classroom Assessment, ed. J. H. McMillan (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE), 71–84.

Chen, J., and Brown, G. T. L. (2013). High stakes examination preparation that controls teaching: Chinese prospective teachers’ conceptions of excellent teaching and assessment. J. Educ. Teach. 39, 541–556. doi:10.1080/02607476.2013.836338

Cizek, G. J. (2010). “An introduction to formative assessment,” in Handbook of Formative Assessment, eds H. Andrade and G. J. Cizek (New York, NY: Routledge), 3–18.

Clark, I. (2012). Foramtive assessment: assessment is for self-regulated learning. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 24, 205–249. doi:10.1007/s10648-011-9191-6

Crossman, J. (2007). The role of relationships and emotionsin student perceptions of learning and assessment. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 26, 313–327. doi:10.1080/07294360701494328

DeLuca, C., Chavez, T., and Cao, C. (2012). Establishing a foundation for valid teacher judgement on student learning: the role of pre-service assessment education. Assess. Educ. Princ. Pol. Pract. 20, 107–126. doi:10.1080/0969594X.2012.668870

DeLuca, C., and Klinger, D. A. (2010). Assessment literacy development: identifying gaps in teacher candidates’ learning. Assess. Educ. Princ. Pol. Pract. 17, 419–438. doi:10.1080/0969594X.2010.516643

Dixon, H. R., Hawe, E., and Parr, J. (2011). Enacting assessment for Learning: the beliefs practice nexus. Assess. Educ. Princ. Pol. Pract. 18, 365–379. doi:10.1080/0969594X.2010.526587

Earl, L. M. (2013). Assessment as Learning: Using Classroom Assessment to Maximize Student Learning, 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Eyers, G. (2014). Preservice Teachers’ Assessment Learning: Change, Development and Growth. Unpublished doctoral thesis, The University of Auckland, New Zealand.

Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: a new area of cognitive-developmental inquiry. Am. Psychol. 34, 906–911. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.906

Flockton, L. (2012). Commentary: directions for assessment in New Zealand. Assess. Matters 4, 129–149.

Graham, P. (2005). Classroom-based assessment: changing knowledge and practice through preservice teacher education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 21, 607–621. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2005.05.001

Hattie, J., and Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Rev. Educ. Res. 77, 81–112. doi:10.3102/003465430298487

Hill, M. F., and Eyers, G. (2016). “Moving from student to teacher: changing perspectives about assessment through teacher education,” in The Handbook of Human and Social Conditions in Assessment, eds G. T. L. Brown and L. R. Harris (New York, NY: Routledge), 57–76.

Hill, M. F., Gunn, A., Cowie, B., Smith, L. F., and Gilmore, A. (2013). “Preparing initial primary and early childhood teacher education students to use assessment,” in Final Report for Teaching and Learning Research Initiative. Available at: http://www.tlri.org.nz/tlri-research/research-completed/post-school-sector/learning-become-assessment-capable-teachers

Kane, M. T. (2006). “Validation,” in Educational Measurement, 4th Edn, ed. R. L. Brennan (Westport, CT: Praeger), 17–64.

Kluger, A. N., and DeNisi, A. (1996). The effects of feedback interventions on performance: a historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychol. Bull. 119, 254. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.119.2.254

Lipnevich, A. A., Berg, D. A. G., and Smith, J. K. (2016). “Toward a model of student response to feedback,” in The Handbook of Human and Social Conditions in Assessment, eds G. T. L. Brown and L. R. Harris (New York, NY: Routledge), 167–185.

McMillan, J. H. (2013). “Why we need research on classroom assessment,” in Sage Handbook of Research on Classroom Assessment, ed. J. H. McMillan (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE), 3–16.

McMillan, J. H., Myran, S., and Workman, D. (2002). Elementary teachers’ classroom assessment and grading practices. J. Educ. Res. 95, 203–213. doi:10.1080/00220670209596593

Mertler, C. A. (2003). Preservice versus inservice teachers’ assessment literacy: does classroom experience make a difference? Paper presented at the Mid-Western Educational Research Association, Columbus, OH.

Montalvo, F. T., and Gonzalez Torres, M. C. (2004). Self-regulated learning: current and future directions. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 2, 1–34.

Nolen, S. B., Horn, I. S., Ward, C. J., and Childers, S. A. (2011). Novice teacher learning and motivation across contexts: assessment tools as boundary objects. Cogn. Instr. 29, 88–122. doi:10.1080/07370008.2010.533221

Pintrich, P. R. (2000). “The role of goal orientation in self-regulated learning,” in Handbook of Self-Regulation, eds M. Boekaerts, P. Pintrich, and M. Zeidner (San Diego, CA: Academic Press), 451–502.

Popham, W. J. (2009). Assessment literacy for teachers: faddish or fundamental? Theory Pract. 48, 4–11. doi:10.1080/00405840802577536

Poskitt, J. (2005). Towards a model of school-base teacher development. New Zeal. J. Teachers Work 2, 136–151.

Poskitt, J. (2014). Transforming professional learning and practice in assessment for learning. Curric. J. 25, 542–566. doi:10.1080/09585176.2014.981557

Sadler, D. (1989). Formative assessment and the design of instructional systems. Instr. Sci. 18, 119–144. doi:10.1007/BF00117714

Siegel, M. A., and Wissehr, C. (2011). Preparing for the plunge: preservice teachers’ assessment literacy. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 22, 371–391. doi:10.1007/s10972-011-9231-6

Smith, L. F., Hill, M. F., Cowie, B., and Gilmore, A. (2014). “Preparing teachers to use the enabling power of assessment,” in Designing Assessment for Quality Learning: The Enabling Power of Assessment, eds V. Klenowski and C. Wyatt-Smith (Dordrecht, Germany: Springer), 303–323.

Stiggins, R. J. (1991). Relevant classroom assessment training for teachers. Educ. Meas. 10, 7–12. doi:10.1111/j.1745-3992.1991.tb00171.x

Stiggins, R. J. (2010). “Essential formative assessment competencies for teachers and school leaders,” in Handbook of Formative Assessment, eds H. L. Andrade and G. J. Cizek (New York, NY: Routledge), 233–250.

Taber, K. S., Riga, F., Brindley, S., Winterbottom, M., Finney, J., and Fisher, L. G. (2011). Formative conceptions of assessment: trainee teachers’ thinking about assessment issues in English secondary schools. Teach. Dev. 15, 171–186. doi:10.1080/13664530.2011.571500

Winterbottom, M., Brindley, S., Taber, K. S., Fisher, L. G., Finney, J., and Riga, F. (2008). Conceptions of assessment: trainee teachers’ practices and values. Curric. J. 19, 193–213. doi:10.1080/09585170802357504

Wylie, C. (2012). Challenges around Capability Improvement in a System of Self-Managed Schools in New Zealand. Available at: https://www.wested.org/wp-content/files_mf/1370998797resource1273.pdf

Zimmerman, B. J. (2001). “Theories of self-regulated learning and academic achievement: an overview and analysis,” in Self-Regulated Learning and Academic Achievement, 2nd Edn, eds B. J. Zimmerman and D. H. Schunk (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 1–37.

Appendix

Interviews with Teacher Candidates

Interview 1—beginning of university academic year following 3-week practicum:

1. What do you think assessment is?

2. What are the purposes of assessment?

3. Why is assessment important?

4. What do you think “effective assessment” means?

5. What ways do teachers gather assessment information?

6. How do teachers use the evidence gathered to inform teaching and learning?

7. In what ways do you think assessment affects students?

8. What have you learned about assessment from your university coursework so far?

9. What have you learned about assessment from your school practicum experiences so far?

10. In what ways, if any, have your beliefs and understandings about assessment changed since you began your teacher education program?

11. What aspects of your teacher education program have been particularly helpful for your learning about assessment?

12. In what ways could your teacher education program have been better in helping you to understand and use assessment?

13. What you are hoping to learn about assessment theory and practice this year both at university and on school practicum?

14. What assessment materials would you like to share to demonstrate your learning about any aspect of assessment theory or practice?

15. Can you explain why you chose these particular assessment examples?

16. Do you have anything else you would like to share about your beliefs, understandings and practices of assessment? If so, please explain.

Interview 2—before going on final school practicum:

1. What have you learned about assessment this semester?

2. Have any of your beliefs or understandings about assessment been challenged or changed?

3. What are you expecting to learn about assessment during your final school practicum?

4. What assessment practices and activities do you expect to use during your period of full responsibility?

5. What assessment materials would you like to share to demonstrate your learning about any aspect of assessment theory or practice?

6. Can you explain why you chose these particular assessment examples?

7. Do you have anything else you would like to share about your beliefs, understandings and practices of assessment? If so, please explain.

Interview 3—after period of full responsibility on school practicum:

1. What assessment activities and tools have you observed being used in the classroom?

2. Do you consider them to be effective or ineffective? Please explain.

3. Are you aware of the assessment policies and procedures if your practicum school? If so, can you give examples?

4. In what ways, if any, are students involved in assessment of their own learning?

5. How have you used assessment to monitor and evaluate children’s learning?

6. How have you used assessment data to make decisions about children’s learning?

7. In what ways have you used assessment information to improve your teaching?

8. Is there anything you would do differently in regards to assessment in your own classroom?

9. In what ways, if any, did your Associate Teacher or other school staff support your learning about assessment?

10. In what ways, if any, did your Visiting Lecturer support your learning about assessment?

11. In your Professional Conversation, how did you demonstrate achievement of your practicum learning outcomes and evidence of the New Zealand Teachers Council Graduating Teacher Standards in regard to assessment theory and practice?

12. What assessment materials would you like to share to demonstrate your learning about any aspect of assessment theory or practice?

13. Can you explain why you chose these particular assessment examples?

14. Do you have anything else you would like to share about your beliefs, understandings and practices of assessment? If so, please explain.

Interview 4—end of university academic year:

1. In what ways, if any, have your changed your beliefs about assessment during this final year of your teacher education program?

2. How have this year’s university coursework and school practicum experiences increased your theoretical understandings of assessment?

3. How have this year’s university coursework and school practicum improved your understanding and use of assessment practices and tools?

4. In what ways have you been able to make connections between your theoretical understandings of assessment and your experiences of classroom assessment?

5. In what ways, if any, have there been instances of conflict or confusion between what you have learned about assessment at university and what you have learned or observed about assessment on school practicum?

6. As you prepare to move into your first year of teaching, how would you evaluate your assessment capabilities?

7. In what ways, if any, could the teacher education program have better supported your learning about assessment?

8. What are your hopes and plans for teaching or further study next year?

9. What assessment materials would you like to share to demonstrate your learning about any aspect of assessment theory or practice?

10. Can you explain why you chose these particular assessment examples?

11. Do you have anything else you would like to share about your beliefs, understandings and practices of assessment? If so, please explain.

Keywords: formative assessment, assessment literacy, assessment capability, teacher candidates, student involvement in assessment

Citation: Hill MF, Ell FR and Eyers G (2017) Assessment Capability and Student Self-regulation: The Challenge of Preparing Teachers. Front. Educ. 2:21. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2017.00021

Received: 29 January 2017; Accepted: 01 May 2017;

Published: 29 May 2017

Edited by:

Susan M. Brookhart, Brookhart Enterprises LLC, United StatesReviewed by:

Leslie Ann Eastman, Lincoln Public Schools, United StatesHarm Tillema, Leiden University, Netherlands