- Swansea University Medical School, Swansea, United Kingdom

Contract cheating, where students recruit a third party to undertake their assignments, is frequently reported to be increasing, presenting a threat to academic standards and quality. Many incidents involve payment of the third party, often a so-called “Essay Mill,” giving contract cheating a commercial aspect. This study synthesized findings from prior research to try and determine how common commercial contract cheating is in Higher Education, and test whether it is increasing. It also sought to evaluate the quality of the research evidence which addresses those questions. Seventy-one samples were identified from 65 studies, going back to 1978. These included 54,514 participants. Contract cheating was self-reported by a historic average of 3.52% of students. The data indicate that contract cheating is increasing; in samples from 2014 to present the percentage of students admitting to paying someone else to undertake their work was 15.7%, potentially representing 31 million students around the world. A significant positive relationship was found between time and the percentage of students admitting to contract cheating. This increase may be due to an overall increase in self-reported cheating generally, rather than contract cheating specifically. Most samples were collected using designs which makes it likely that commercial contract cheating is under-reported, for example using convenience sampling, with a very low response rate and without guarantees of anonymity for participants. Recommendations are made for future studies on academic integrity and contract cheating specifically.

Introduction

In 2014 there were 207 million students in Higher Education (HE), a number which has doubled since 2000 and accounts for one third of all school leavers (Unesco, 2017). HE now forms a significant part of the economy for many countries around the world and is the means by which many people are trained to undertake important roles in society; engineers, health professionals, lawyers etc. Assessment is the means by which HE providers determine whether their students have achieved the learning required for those roles. Some students “cheat” on some assessments, meaning they acquire academic credit for work which is not their own. For decades there has been research in to how and why students cheat; how common it is, and ways in which it could be addressed.

Contract cheating, first defined by Clarke and Lancaster in the mid 2000's, (Clarke and Lancaster, 2007) is a form of cheating where students actively get someone else to do their work for them. A recent definition is “a basic relationship between three actors; a student, their university, and a third party who completes assessments for the former to be submitted to the latter, but whose input is not permitted. ‘Completes’ in this case means that the third party makes a contribution to the work of the student, such that there is reasonable doubt as to whose work the assessment represents” (Draper and Newton, 2017).

Media accounts of this problem often identify commercial services as the third party, with money being paid by a student in return for some form of written assignment (Bartlett, 2009; Anonymous, 2013; Matthews, 2013; Henry et al., 2014; Bomford, 2016; Usborne, 2017). Most academic research to date has considered payment synonymous with a definition of contract cheating (e.g., Mahmood, 2009; Walker and Townley, 2012; Clarke and Lancaster, 2013; Wallace and Newton, 2014; Curtis and Clare, 2017; Rowland et al., 2017, 2018; Ellis et al., 2018), although a recent project has expanded the area of study to include other third parties such as friends and family members (Bretag et al., 2018; Harper et al., 2018).

Commercial contract cheating providers use persuasive marketing techniques to create a sense of urgency and legitimacy (Rowland et al., 2018) while protecting themselves from legal allegations of “fraud” by using terms and conditions which make their clients responsible for misuse of their products (Draper et al., 2017). Similar services are on offer through variants of the “gig economy” wherein students or agents advertise work (e.g., writing an assignment) on freelancing-type sites and writers bid for the opportunity to complete the work (Newton and Lang, 2016). The services they offer have a fast turnaround (Wallace and Newton, 2014) and the academic risks associated with their use are poorly understood by students (Newton, 2015).

The commercial aspect to contract cheating is perhaps the most troubling aspect of the behavior; making it a qualitatively different concept to that of “cut-and-paste” plagiarism, or obtaining inappropriate assistance from a friend or family member. The act of payment makes contract cheating deliberate, pre-planned and intentional. This is reflected in the recommended academic penalties for contract cheating, which are severe (Tennant and Duggan, 2008). Payment for cheating services is a significant concern to the international higher education sector. The independent body that checks standards and quality in UK higher education, the Quality Assurance Agency, recently published guidance for higher education providers on how to address the problem of contract cheating, stating “this guidance is concerned with third-party assistance that crosses the line into cheating; in other words, collusion with a paid-for element” (QAA, 2017). Similar guidance from the Australian regulator the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA) stated “….of particular concern is the proliferation of marketing-savvy commercial providers” (TEQSA, 2017).

Despite the obvious implications of contract cheating for quality and standards in HE, and the attendant concern from many stakeholders, we do not currently have a clear understanding of how common contract cheating is, or whether it is increasing. These are two of the questions which are addressed in the current study. Much of the media coverage suggests that contract cheating is a significant and increasing problem. In the UK we are told that “universities are gripped by an epidemic of so-called ‘essay mills,’ which sell essays, coursework or exam answers to students” (Turner, 2017) as “students in the UK are increasingly turning to third party essay writing services” (White, 2018), while in Canada “There's been an increase in university students doing "contract cheating” (Hunt, 2017) and in Australia “universities grapple with a rise in contract cheating” (Cook, 2017). This apparent increase has even led the Australian government to announce millions of dollars of extra funding for TEQSA to address the problem, on the basis that “new studies have found there is a growing trend among students to buy work from the increasing number of ‘essay mills’ that advertise themselves online” (Dodd, 2018).

The idea that contract cheating is on the rise has also found its way into the academic literature (e.g., Walker and Townley, 2012). The International Journal for Educational Integrity recently published a special collection on the “explosion in contract cheating,” with the rationale that “most commentators agree that there has been a global rise in contract cheating in recent years, across all disciplines” (IJEI, 2017). However, research data to support that assertion are currently lacking. A recent small scale synthesis of five different samples found no obvious increase in self-reported contract cheating over time (Curtis and Clare, 2017).

There are currently no reliable objective measures of the extent of contract cheating; a basic trait advertised by many contract cheating services is that their products are “plagiarism-free” (Newton and Lang, 2016; Draper et al., 2017) and thus difficult to identify with originality-detection software. Experimental studies of cheating behaviors, wherein students are essentially “set-up” to have the opportunity to cheat and the incidence is then measured, have declined in recent decades, possibly over ethical concerns (Whitley, 1998; Liebler, 2016).

Self-report of studies of general cheating behavior are numerous and well established. Liebler identified 411 studies between 1930 and 2013 which attempted to estimate how many undergraduate students have cheated in the USA. More than half (222) of these studies were survey-based (Liebler, 2016). In 1998, Whitley, when reviewing studies on the prevalence of cheating, found 107 studies published between 1970 and 1996 in the USA and Canada alone (Whitley, 1998). Self-report is obviously a potentially problematic measure of “undesirable” behaviors such as academic misconduct (Juni et al., 2006), although there are reports that rates of actual vs. self-report are positively correlated (Gardner et al., 1988).

Many self-report studies undertake some sort of factor analysis to identify traits/circumstances associated with self-report of cheating. A considerable number of factors have been shown to influence rates of self-reported cheating and these have been reviewed a number of times (e.g., Whitley, 1998; Megehee and Spake, 2008). A comprehensive review of all these factors is beyond the scope of the manuscript, but for illustration some of the factors identified include;

• Past cheating behavior (Nonis and Swift, 1998; Whitley, 1998; Quintos, 2017)

• An understanding of what constitutes cheating/academic integrity training (Christensen-Hughes and McCabe, 2006; O'Neill and Pfeiffer, 2012; Curtis et al., 2013)

• The use of honor codes (McCabe, 2016)

• Poor study conditions (Whitley, 1998)

• Academic level/year of study (Baetz et al., 2011; Ledesma, 2011; Ahmadi, 2014)

• Stress/lack of time (Park et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2013)

• Gender (men more likely to cheat) (Genereux and McLeod, 1995; Newstead et al., 1996; Nonis and Swift, 1998; Athanasou and Olasehinde, 2002; Selwyn, 2008; Baetz et al., 2011; Eret and Ok, 2014)

• Grades (poorly performing students more likely to cheat) (Genereux and McLeod, 1995; Newstead et al., 1996; Park et al., 2013)

• Dissatisfaction with/poor learning environment (Whitley, 1998; Balbuena and Lamela, 2015; Bretag et al., 2018)

• A “normalization” of cheating including the perception that others are doing it (Genereux and McLeod, 1995; Whitley, 1998; Stephens et al., 2007; Megehee and Spake, 2008; Quintos, 2017)

• Studying in a second language/language tutoring (Ledesma, 2011; Bretag et al., 2018).

• Lenient institutional approaches to cheating/likelihood of being caught (Christensen-Hughes and McCabe, 2006; Megehee and Spake, 2008; Balbuena and Lamela, 2015).

• Lack of motivation (Park et al., 2013)

• Discipline studied (Newstead et al., 1996; Selwyn, 2008; Sendag et al., 2012; Ahmadi, 2014; Eret and Ok, 2014)

• Age (younger students more likely to cheat) (Hilbert, 1985; Newstead et al., 1996; Christensen-Hughes and McCabe, 2006; Hart and Morgan, 2010; Ahmadi, 2014)

• Distance learning vs. face to face (Kidwell and Kent, 2008; Hart and Morgan, 2010)

• An expectation that cheating will result in positive outcomes (Whitley, 1998; Park et al., 2013).

This study sought to identify, as far as possible, all self-report survey samples which include specific questions about contract cheating. By bringing together a large corpus of samples it should then be possible to obtain a more accurate estimate of the frequency with which students report engaging in commercial contract cheating, for example by reducing the impact of outliers of under-and over-report. It should then enable the calculation of a baseline figure from the literature (Research Question 1) and enable testing for a trend over time, i.e., is contract cheating increasing (Research Question 2). Similar principles have been applied to the estimation of the numbers of scientists who have fabricated or falsified research findings (Fanelli, 2009) or engaged in plagiarism (Pupovac and Fanelli, 2015).

A large corpus of samples also allows the investigation of a third research question; how reliable is the research which underpins the media headlines, and upon which policy and even law might be based? Given the potential significance of contract cheating to academic quality and standards, it is important to understand the nature of the research itself. Education research has, by some accounts, a historically poor reputation, which has itself then been the subject of inquiry (e.g., Gorard et al., 2004). All of the research described here is survey-based, as is common in education research. There are a large number of factors to consider when designing and conducting survey-based research, and all of these factors can profoundly influence the quality of the resulting data (Butt et al., 2016; Sullivan and Calderwood, 2017).

Methods

This study set out to address specific questions from data collated from published survey-based samples. The studies potentially represent a large amount of data from a large number of participants. To maintain the accuracy and integrity of the analysis, the number of research questions asked here was deliberately limited and these were defined prior to commencement of the study, so as to avoid over-analysis and returning spurious findings. In addition the analysis was also kept simple and focused on the specific research questions, which were as follows;

1. How common is self-report of commercial contract cheating in Higher Education?

2. Is commercial contract cheating increasing in Higher Education?

3. How good is the evidence which might allow us to answer “1”+“2”

Identifying Samples

From May 2017 to March 2018, the database Google Scholar was used to identify primary research whose data included some measure of self-report of contract cheating by students.

In light of the concerns from regulators, lawmakers and the attendant media coverage, for the purposes of this study, self-report of contract cheating was identified as student participants answering “yes” to a question about whether they had purchased or in some other way paid money for an assignment (note that some samples asked “purchased or obtained,” see below).

Initial searches were made using Google Scholar using basic terms relating to contract cheating, identified using the experience of the author (Wallace and Newton, 2014; Newton, 2015; Newton and Lang, 2016; Draper et al., 2017; Ransome and Newton, 2017).

Where a study was identified which met the inclusion criteria (see below) then searches were also undertaken using the relevant contract cheating question from the survey instrument. For example, Nonis and co-workers asked participants to identify how often they had “Turned in a paper that you purchased from a commercial firm” (Nonis and Swift, 1998) and so a search was then undertaken with the quoted phrase. Manuscript text and reference lists were also “daisy chained” to identify relevant research from studies that cited them and also the research they cited.

The full list of terms searched was “purchased an essay,” “purchased an assignment,” “purchased assignments,” “purchased a dissertation,” “purchased a work,” “purchased coursework,” “essay purchased,” “purchased a term paper,” “paper that was purchased,” “essay that was purchased,” “paper that you purchased,” “essay that you purchased,” “purchased homework,” “purchasing homework,” “paid for an essay,” “paid for essays,” “paid for an assignment,” “paid for a dissertation,” “paid for a work,” “paid for a term paper,” “paid another student,” “paid for coursework,” “paid an essay,” “paid for homework,” “bought an essay,” “bought essays,” “bought an assignment,” “bought a work,” “bought a term paper,” “bought coursework,” “essay bought,” “coursework bought,” “bought homework,” “homework bought,” “buying an essay,” “buying an assignment,” “buying a dissertation,” “buying coursework,” “buying a term paper,” “pay someone to write it for,” “pay someone to write it,” “pay for an essay,” “pay for an assignment,” “pay for homework,” “pay for coursework,” ”academic integrity survey,” “survey of academic integrity,” “essay purchase,” “‘prevalence of cheating’ ‘essay mill’,” “‘prevalence of cheating’ ‘paper mill’,” “Turning in a paper obtained in large part from a Term paper ‘mill’/web site that did charge,” “‘paying someone else’ cheating,” “prevalence of contract cheating,” “prevalence of academic dishonesty,” “prevalence of plagiarism,” “cheating experience questionnaire,” “submitting coursework from an outside source,” “buying a term paper,” survey “term paper mill,” “used an essay mill,” “paid another” plagiarism, “hired a ghostwriter,” “paid a ghostwriter” “ghostwritten essay,” “ghostwritten assignment,” “submitting a paper purchased,” “turning in a paper purchased,” “submitting a paper purchased,” “submitted a paper purchased,” “hilbert unethical behavior survey.”

Google Scholar was used as the principle database for searching as it has better coverage of gray literature (Haddaway et al., 2015) and unpublished theses; providing direct links to full text downloads of these where they are hosted on (for example) university servers (Jamali and Nabavi, 2015) To test these findings, a preliminary comparison of search results was undertaken using a second database (Education Resources Information Center; ERIC). ERIC did not return any additional results and so Google Scholar was utilized as the sole source.

However there are some limitations when using Google Scholar to report search findings. It includes citations and multiple versions of the same papers, and there are limitations to specificity of the search interface (Boeker et al., 2013), for example it is not possible, at the time of writing, to exclude the results of one search from another, or to save or export search results. In the current study, Google Scholar also, with some of these search terms, returns hundreds of spurious non-academic results, for example from essay writing services themselves as well as guidance documents from education providers alongside other gray literature material. Although these “limitations” mean that Google Scholar casts a wide net in terms of search results, but they also mean it was not possible to identify, with any meaningful accuracy, how many papers were returned from each search term. For example, “buying an essay” returned 78 results at the time of searching. However most of these were handbooks from academic courses (warning against buying essays), legal documents and adverts for/documents from commercial essay writing services. Most searches returned large numbers of irrelevant/spurious results and very few relevant results.

The text and bibliography of review articles and book chapters about contract cheating and related topics were also examined (Dickerson, 2007; Mahmood, 2009; O'Malley and Roberts, 2012; Walker and Townley, 2012; Owings and Nelson, 2014; Lancaster and Clarke, 2016; McCabe, 2016; Newton and Lang, 2016) to identify studies which looked at prevalence.

All search results were individually assessed against the inclusion criteria, starting with the title, then (if appropriate) the abstract and then the full text. If a title demonstrably did not meet the inclusion criteria then it was excluded. If there was ambiguity, then the abstract was reviewed, and so on.

Inclusion Criteria

These are inclusion criteria for the data, as well as the samples; most samples addressed multiple forms of misconduct but only data that met these criteria were analyzed

• Study asked participants whether they had ever paid someone else to undertake an “assignment” or “homework” for them (this could be partially or completely).

◦ Samples that included payment as an option (e.g., “paid or obtained”) were included

◦ This question had to be a “primary” question, i.e., it was all asked together, in one question, of all participants (rather than a multi-question approach e.g. such as “have you ever used a ghostwriter” followed by a separate question of “did you ever pay for it” (e.g., Stella-Maris and Awala-Ale, 2017)

• Participants were students in Higher Education

• Data were reported in a form which allowed inclusion; reporting both total sample size and percent of respondents answering yes to the relevant contract cheating questions. (Many samples used Likert scales to ask, for example, “how often have you done this” and then reported only means. These studies are not included)

• English language publication

Exclusion Criteria (for Samples and Data)

This study did not analyse data regarding the following;

• Paying for examinations or some other in-person assignment

• Asking participants would they ever engage in contract cheating

• Asking participants how serious they think contract cheating is

• Asking participants ‘how common is contract cheating by others’

• Ambiguity over source (e.g. ‘obtaining an assignment from an essay mill or a friend’)

• Community College or Further Education

Metrics

All data were extracted twice to ensure accuracy. Fanelli (2009) undertook a systematic review of self-report of research misconduct by scientists; asking questions broadly similar to those under study here, using a conceptually similar dataset. Fanelli states “given the objectivity of the information collected and the fact that all details affecting the quality of studies are reported in this paper, it was not necessary to have the data extracted/verified by more than one person” (Fanelli, 2009) and the same principle was used here. The following data were recorded, where possible and are presented in full in the Table A1.

• The number of participants in the sample

• The total population size from which the sample was drawn

• The number who answered “yes” to having engaged in contract cheating as defined above

• The number of participants who engaged in the most frequently reported item of academic misconduct reported in the study (“highest cheating behavior” in Table A1)

• The year the study was undertaken, where stated. If this was a range (e.g., Jan 2002–March 2003) then the year which represented the largest portion of the timeframe was used (2002 in the example). If it was simply given as an academic year (e.g., 2008–2009) then the later of those 2 years was used). If this was not stated then the year the manuscript was submitted was used. If this was not stated then the publication year was used.

Some samples allowed participants to indicate how often they had/have engaged in contract cheating. The wording of these scales varied considerably; some asked participants whether they had “ever” engaged in the behavior, some “in the last year.” Some allowed frequency measures based on Likert scales, while others allowed for more specific measures such as “once, 2–3 times, more than 3 times” etc. The heterogeneity of these scales meant it was not possible to compare across them. Recent reports indicate that most students who engage in contract cheating are “repeat offenders” (Curtis and Clare, 2017) and so for the primary analysis all frequency measures were collapsed into a single “yes” category in order to identify all those students who self-report engaging in contract cheating at least once at some point during their studies, again following the principle set by Fanelli (2009). This measure is also important as it identifies the total numbers of students whose behavior might be criminalized if contract cheating were made illegal, and identifies the size of the customer base for contract cheating services.

Three samples (Scanlon and Neumann, 2002; Park et al., 2013; Abukari, 2016) asked more than one question about contract cheating. For example (Scanlon and Neumann, 2002) asked participants about “purchasing a paper from a term paper mill advertised in a print publication” and “purchasing a paper from an online term paper mill.” In these cases the average of the two questions was calculated, rather than including both as this would result in double counting of participants and so artificially inflate the total sample size. Where samples set out to include, and reported on, more than one sample, such as samples from different countries, or explicitly comparing undergraduate vs. postgraduate (e.g., Sheard et al., 2002, 2003; Christensen-Hughes and McCabe, 2006; Kirkland, 2009; Kayaoglu et al., 2016) then these were treated as separate. Samples that were separated into distinct samples Post hoc (e.g., age or study mode) were treated as a single sample. Where samples reported a “no response” option, then these were removed from the total sample size (Babalola, 2012; Abukari, 2016).

Nineteen samples asked questions about contract cheating that included an option of payment, for example “Submitting a paper you purchased or obtained from a website (such as www.schoolsucks.com) and claiming it as your own work” (Kirkland, 2009; Bourassa, 2011) or “Submitting coursework from an outside source (e.g., a former student offers to sell pre-prepared essays; essay banks)” (Franklyn-Stokes and Newstead, 1995; Newstead et al., 1996). A Mann-Whitney U test revealed no significant difference in percentages of students self-reporting engaging in contract cheating between those that required payment, and those which included it as an option (U = 452.5, P = 0.594) therefore all samples were included in the analysis.

The following calculations were also made;

Response rate is, simply “the percentage of people who completed the survey after being asked to do so” (Halbesleben and Whitman, 2013). The higher the response rate, the more likely the data are an accurate reflection of the total sample. Two measures were recorded here; first simply was the response rate reported (or were the data reported to allow a calculation of the response rate), and second, what then was the response rate. The “total sample” was defined as the total number of participants who were asked to, or had the opportunity to, fill out the survey, and response rate was the percentage of that sample who completed the survey returning useable data. “Unclassified” meant that insufficient data were reported to allow calculation of the response rate.

Method of sampling was identified as follows, where “population” refers to the population under study, for example, “engineering students at University X,” or “students at in Department Z at University Y.” “Convenience sampling” meant that, within the population identified, all were able to complete the survey and data were collected from volunteers within that population. “Random” sampling meant that a sample from the population was chosen at random. Participants then completed the survey voluntarily. “Unclassifiable” meant that insufficient information was provided to allow determination of the sampling method.

Piloting The use of a pilot or “pre-test” of a survey allows for the researcher to check clarity and understanding, thus increasing reliability and decreasing error (Butt et al., 2016). The identified studies were screened to determine whether they stated that a piloting phase was undertaken. This had to take the form of some pilot with student participants. Studies that stated the survey was piloted were recorded as “yes.” One of four options was recorded; (1) Y or (2) N for whether a piloting phase was described. Some studies used research instruments from, or elements of, previously published studies and these were recorded as (3) YP or (4) NP where the instrument was then piloted (or not) in the context of the study being analyzed.

Type of publication was recorded as one of (1) journal publication, (2) unpublished thesis, (3) conference paper or (4) “gray literature” report

Was ethical approval obtained for the study This was recorded as “yes” where the authors stated that ethical approval had been obtained, and “no” where such statements were not present.

Were participants assured of their anonymity Consequences for engaging in contract cheating are often serious for students (Tennant and Duggan, 2008) and thus for research to obtain accurate self-report, some assurances of anonymity should be given (not just confidentiality). To meet this criterion studies were screened to determine whether the data were collected anonymously and that participants were explicitly informed that their data would be treated as anonymous (or that it would be obvious). For a handful of studies this was a borderline judgment, for example where paper questionnaires were “returned to an anonymous collection box”—this would be scored as “no” because it is not reported that it is explicitly clear to the participants that the data are anonymous.

Results

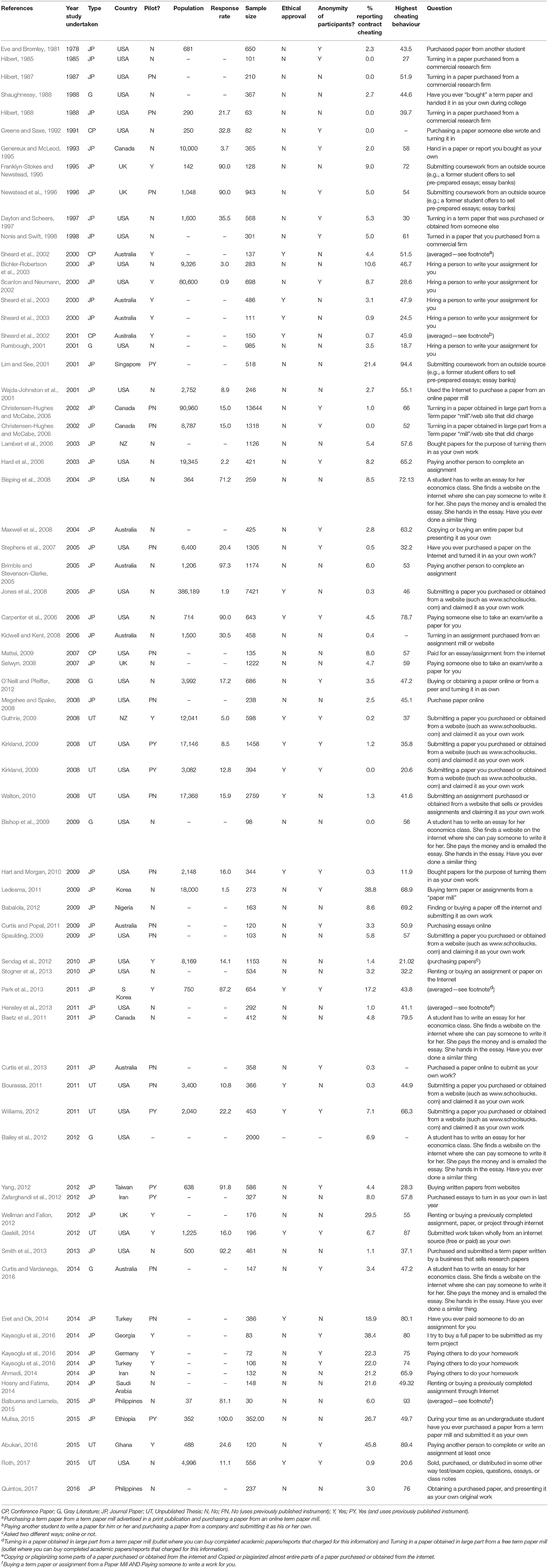

Seventy-one samples were identified from 65 studies, containing a total of 54,514 participants spanning years 1978–2016. The full list of publications and extracted data are shown in the Table A1. 52 (73.2%) were journal papers, 9 (12.7%) were unpublished theses, 6 (8.5%) were gray literature publications and 4 (5.6%) were conference papers.

How Common Is Self-Report of Commercial Contract Cheating in Higher Education

Of the 54,514 total participants, 1919 (3.52%) reported engaging in some form of commercial contract cheating. This finding was also reflected in the distribution of responses from the 71 samples, where the median was 3.5%. Nevertheless there was a wide range of responses, and these reflected some of the trends over time as shown below; in 7 of the samples, all before (inc) 2009, no students reported having engaged in contract cheating. The 10 samples with the highest rates of contract cheating (all over 20%) were all, except one, from 2009 or later.

Is Commercial Contract Cheating Increasing in Higher Education?

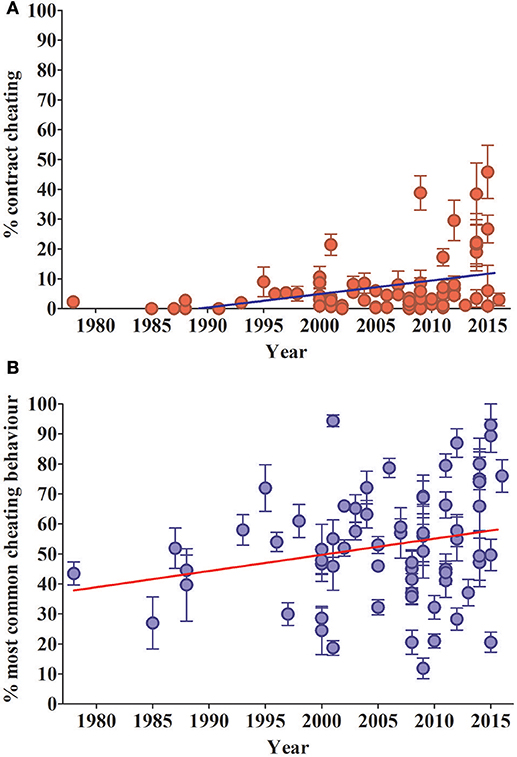

In Figure 1A, the data for percentage of students reporting having engaged in contract cheating are plotted against the year the study was undertaken. A Spearman Rank correlation analysis demonstrated a statistically significant positive correlation between these two variables, i.e., contract cheating appears to have increased over time [r(71) = 0.368, P = 0.0016].

Figure 1. Self-reports of commercial contract cheating have increased over time. (A) The plots show the percentage of respondents, in individual samples, who answered “yes” to having paid a third party to undertake assignments for them, ±95%CI. (B) The percentage of participants answering yes to engaging in the most commonly reported form of misconduct in the sample. These have also increased over time, ± 95%CI.

One possible explanation for this finding is that academic misconduct generally is increasing. Sixty seven of the samples reported on a range of academic misconduct behaviors and thus allowed extraction of data showing the most common single form of self-reported academic misconduct. These data showed a weaker but statistically significant positive correlation with year of study [r(67) = 0.247, P = 0.04] (Figure 1B) and the positive relationship between contract cheating and year of study remained significant from these 67 samples [r(67) = 0.353, P = 0.0034]. In addition, in these samples there is a strong positive correlation between levels of self-reported contract cheating and the single most common form of misconduct in a single study [r(67) = 0.593, P < 0.0001].

Thus both contract cheating, and misconduct generally, appear to be increasing. A simple linear regression model was fitted to predict contract cheating levels based on year. A significant regression equation was found [F(1, 65) = 10.63, p = 0.0018), with an R2 of 0.1406. A similar model for predicting engagement in the highest individual cheating behavior was close to significance [F(1, 65) = 3.621, p = 0.06], with an R2 of 0.053. The slopes of the two models were not significantly different [F(1, 130) = 0.053, p = 0.819].

Taken together then, these data suggest that contract cheating has increased over time, but that this is likely, at least in part, due to an overall increase in misconduct reported in the samples analyzed here.

To test the robustness of these findings, and their potential sensitivity to error, a simple split-sample test was undertaken, wherein the dataset was divided in two. Samples were arranged by date. Where more than one sample had the same date, they were sub-ordered by the percentage of students who self-report contract cheating. The sample was then split into two by placing “every other” sample into a different groups (i.e., sample 1 was placed into Group A, sample 2 into Group B, sample 3 into Group A, sample 4 into Group B, and so on). A Mann-Whitney U test of the percentage of students self-reporting contract cheating revealed no significant difference between the two groups (U = 627, P = 0.9770). Both groups were tested to determine whether they showed an increase in self-report of contract cheating over time. Both tests (Spearman Rank correlation and Linear Regression) were significant for both groups [Spearman Group A r(36) = 0.3445, P = 0.0396, Group B r(35) = 0.4019, P = 0.0167, Linear Regression group A F(1, 34) = 5.056, P = 0.0311, Group B F(1, 33) = 5.945, P = 0.0203]. These data show that findings of the main analysis are also returned when half the sample is excluded (and that it does not matter which half). This suggests that, in terms of the research questions being addressed here, the total sample is saturated and the findings are robust.

Quality Metrics of Studies

Sampling Method

Fifty of the 71 samples (70.4%) used convenience sampling. 14 (19.7%) did not provide sufficient information to determine the sampling method used. Seven samples (9.0%) stated that they used some sort of random/random stratified sample, but it is not clear how the stratification/randomization was undertaken. Completion of the survey was still then voluntary for these random samples.

Sample Size

Median sample size was 365. These were not normally distributed; 67 of the 71 samples were under 1,500. The lower quartile was 148 and the upper quartile was 643. The full range of sample sizes is shown in Table A1.

Response Rate

Only 34 of the 71 samples reported sufficient information to allow calculation of a response rate. An additional 5 provided estimates of the response rates based upon observations of (for example) the numbers of participants in a room who completed the survey, resulting in information relating to response rate for 39 of the 71 samples (55%). These 39 samples represented a total population of 718,526, with a total sample of 42,108, a response rate of 5.86%. The variance within the individual samples was considerable, ranging from 0.87 to 100%, with a median of 17.2%.

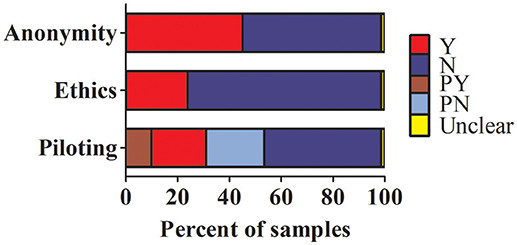

A summary of the following key quality metrics is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Summary of key quality metrics; were participants guaranteed anonymity, did the study report ethical approval, and was the survey instrument piloted before use. The percentage of samples meeting each criterion is shown in red (Y), while those which did not are shown in blue (N). For the piloting analysis, those samples which piloted the instrument before use and used a previously published instrument are dark red (PY), while those using an established instrument without piloting are pale blue (PN).

Piloting

Twenty-two (31%) of the samples described having piloted their survey with students. Of those, 7 (9.9%) used a previously published survey while 15 (21.1%) did not. 48 (67.6%) of the samples did not describe piloting, although 16 of those (22.5%) used a previously published survey. One study could not be classified.

Anonymity

Thirty-eight of the 71 samples (53.5%) did not describe having made it clear to students that their responses were anonymous.

Ethics

Fifty-three of the 71 samples (74.6%) did not state having obtained ethical approval for the study.

Discussion

A minority of students surveyed (3.52%) self-report having engaged in contract cheating. Two different analyses indicate that this is increasing, likely in part due to an overall increase in the self-report of cheating in general. These data strongly suggest that there is substance to the portrayal, by media and the policy makers, of contract cheating being “on the rise.” There are a number of implications of this finding. As described in the introduction, there are over 200 million students enrolled in Higher Education around the world (Unesco, 2017). The data analyzed here suggest that a historic average of 7 million of them are paying other people to complete their work. Since 2014, the data suggest that this figure is 31 million although these figures are likely under-reported as described below.

What follows then is a discussion of a number of issues to be considered when interpreting these data. For each issue, the current analysis is compared to the prior literature, and where possible, recommendations are then developed to address those limitations for future research. A similar approach is taken with policy recommendations.

A significant finding here is that the typical study has a low response rate, is from a convenience sample of volunteers, does not have obvious ethical approval and does not inform participants that their responses will be completely anonymous. These factors all seem likely to interact, as described below.

Over 70% of samples were obtained using some form of convenience sampling, the next biggest category (19.7%) being samples for which there was not enough information for their sampling method to be determined. This use of convenience sampling, and the attendant low response rate, raises questions about how representative the samples will be of the population under study. Consideration has to be made as to whether non-responders would have been more or less likely to have engaged in commercial contract cheating.

The effect of non-response has been studied for academic misconduct generally, where it has been shown that convenience sampling via self-report tends to underestimate cheating compared to a more rigorous randomized design (e.g., Scheers and Dayton, 1987), although some studies conclude that the two measures are at least correlated (Erickson and Smith, 1974).

In the survey literature more generally, a significant factor driving non-response is fear of data misuse (Haunberger, 2011). Contract cheating by students is associated with serious penalties (Tennant and Duggan, 2008) and almost all students know that it constitutes academic misconduct (Newton, 2015). Thus it would seem reasonable to conclude that students who have engaged in commercial contract cheating will be more fearful of data misuse and thus less likely to respond to a survey about cheating, or to an item about contract cheating within such a survey. This effect will then have been amplified by a lack of guaranteed anonymity for participants, in over 50% of the samples.

Cheating in general is considered a “deviant” or “undesirable” behavior, even if the motivations for engaging in it are complex. Commercial contract cheating services are illegal in some jurisdictions (Newton and Lang, 2016) and there is currently serious consideration to making them illegal in others (Draper and Newton, 2017; Irish Legal News, 2017). The literature on self-report and non-response bias in criminology is therefore relevant and suggests that those who do not self-report are more likely than average to have characteristics associated with an increased risk of engaging in deviant behavior (i.e., cheating in this case; Junger-Tas and Marshall, 1999).

There are also some general characteristics of participants who voluntarily complete surveys. These have been studied numerous times for multiple types of convenience sampling and are obviously subject to influence from the local context in which the sample is applied, but the general picture is that participants who volunteer/agree to participate in surveys are more likely to be older, female, well-educated, and from a higher socioeconomic background (Curtin et al., 2000; Goyder et al., 2002). These characteristics are in complete contrast to the factors associated with an increased likelihood of engaging in cheating as described in the introduction. These individuals are, when compared to the population average, more likely to be young, male participants from low socioeconomic background and lower education levels.

Taking all these interacting factors together then, it seems highly likely that non-responders are more likely to have engaged in commercial contract cheating, and thus the current rate is under-reported.

It is important to note that the studies being analyzed were designed for purposes other than the one for which they are being used here. Many are aimed at examining the occurrence of misconduct at a local level, using a convenience sample as a cheap and simple way of getting an estimated answer and with no intentions to generalize beyond their local context. Many studies acknowledge the limitations of their methodology and the critique undertaken here should not be seen as criticism of those researchers. However it is clear that there is an urgent need for the use of more rigorous research methods, beyond convenience sampling, to study academic misconduct in a wider context.

The findings reported here raise a number of additional interesting questions for further study. For example it is clear that the simple linear regression model does not fully account for the variance in the contract cheating data, and an eyeballing of the plot in Figure 1A suggests that there has been a long period with low levels of contract cheating followed by a sudden rise in recent years. Further modeling was not undertaken here due to the limitations of the data set as described above. For example, weighting by sample size may improve the fit of a model, but may undermine the validity of the findings since, with the current research questions, the representativeness of an individual sample is much more important than its size. Having a large convenience sample with the attendant low response rate simply increases the amount of data from unrepresentative participants.

Further research could also be informed by more rigorous study of other variables associated with commercial contract cheating, using representative samples with a high response rate. For example; is commercial contract cheating subject to the same drivers as other forms of misconduct? While it might seem reasonable to assume that this is the case, there are some suggestions otherwise. As described above, misconduct appears to be more commonly committed by male students, yet one of the highest rates of commercial contract cheating reported here was in an all-female sample (Hosny and Fatima, 2014). Commercial contract cheating might also be more subject to infrastructure, institutional and societal factors, since these can facilitate/mitigate the involvement of the third party. Examples may include the legality (or not) of commercial contract cheating, and more general levels of corruption. There are potentially other, perhaps less obvious, infrastructure issues. For example, Babalola reported that 8.2% of participants at a Nigerian university admitted to “buying a term paper or assignments from a ‘paper mill.”’ She considered that this figure was low, and driven in part by the requirement for a credit card to use paper mills when use of a credit card “is not common in Nigeria” (Babalola, 2012).

Another possible issue with interpretation of the data is surveillance bias; there are more samples in recent years. Potentially this is itself evidence of an increase in commercial contract cheating; researchers would presumably only ask about contract cheating if it were relevant at the time and many of the samples are focused on the use of the internet to facilitate cheating, something that was not an issue in the 1980s. This does mean that the impact of the older samples is potentially larger when considering a trend over time, and the older samples tend to show low rates of commercial contract cheating. However, the lower border of the data range is (repeatedly) zero. Thus if there had been more samples in the 1980s and they showed higher rates of commercial contract cheating and thus the trend over time isn't “real,” then that means the overall rate has been higher all along; this is possibly more concerning from a policy perspective. Similarly if the apparent increase is driven in part by the fact that samples are not being reported from a broader geographical and cultural sample, this implies that, had similar samples been obtained in the 1980s, we would again have seen a historically higher rate of commercial contract cheating. For example, the majority of the larger studies were conducted in North America, and yet the more recent samples, including those with a higher incidence of commercial contract cheating, were taken outside North America. It is therefore possible that commercial contract cheating has always been more common outside North America. This interpretation is also potentially further complicated by the fact that 9 of the samples are unpublished theses and 7 of these are from the USA. The simple principle of digital public publishing and cataloging of unpublished theses in the USA means there are more data collected from the USA. This study also only captures data from English-language samples, which may influence the data in a similar way.

A similar interpretation can be applied to the finding that self-report of cheating, in general, appears to have risen. On the one hand this may not mean that contract cheating has specifically increased. However, it does not change the finding that contract cheating has risen, with all the associated implications, and raises an additional set of concerns regarding additional forms of cheating.

There are other ways in which the scale of commercial contract cheating could be estimated, for example to look at the financial status of the industry. In 2014 Owings and Nelson reviewed what they called “The Essay Industry” and estimated that it “has annual revenues somewhere upward of $100 million with estimated minimum profits of $50 million.” Interestingly, they also stated that “There are no publicly traded firms in the essay industry because the product they are offering is often illegal,” a contrast to the situation in the UK where the practice is currently legal and many firms are registered as legitimate businesses with the UK government (Draper et al., 2017). A New Zealand law designed to curb commercial contract cheating was deployed in the prosecution of a company “Assignments4U.” In court it was revealed that the company had received ~800,000 USD (1.1 million New Zealand Dollars) over a 5 year period. However such cases are rare, and any analysis will not capture payments through the informal “gig economy.”

Rigby and colleagues took a different approach (Rigby et al., 2015), using a series of choice experiments on a sample of 90 UK undergraduate students. Eight different scenarios included a simple choice about whether or not to buy an essay. The different scenarios, when combined with demographic data about the participants and results from a parallel gambling study, modeled the influence of various factors including; gender, the quality of the essay, the price, the academic level of the student, the severity of the penalty, how risk-averse the students were and whether they were studying in a second language. Exactly half the students indicated that would be willing to purchase an essay under at least one of the scenarios, while 7 of the participants (7.8%) were willing to buy an assignment under every choice condition. All of the aforementioned factors influenced these choices, in ways that might be predicted; willingness to risk essay purchase was higher for participants with low risk aversion, for a good essay, lower risk of penalty, if the student was weak academically, studying in a second language, or male. The influence of studying in a second language was particularly strong, but the authors urge caution about generalizing from these analyses, given the relatively small size of the sample. However, this study also suggests that self-report of engagement in commercial contract cheating results in an underestimate.

The majority of the samples did not describe having secured ethical approval for the research (74.6%) or making it clear to participants that their responses were anonymous. There are some obvious caveats to any interpretation of this section of the results; absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. Many journals now require evidence of, or at least a statement regarding, having obtained ethical approval and thus this may have been obtained but is not reported. Judgments about anonymity were occasionally subjective, with some samples describing “confidentiality” or even “anonymity” but then (for example) having questionnaires handed out and collected by the researchers who were faculty at the host institution.

This review is essentially pragmatic in nature, driven by the principle that the question is more important than the method. However the limitations of the data, and their source, mean that it is not possible to fully adhere to strict principles of Systematic Review. For example, the present study was modeled, in part, on a single-author study by Fanelli who systematically reviewed survey studies of self-reported research misconduct by scientists (Fanelli, 2009). However, Fanelli excluded all studies which did not use random sampling; a reasonable quality metric for survey-based research. To apply that quality threshold here would have been to essentially dismiss almost all of the available research. Taking a pragmatic approach; including the convenience samples but with a consideration of the potential problems this brings, allows the research questions to be answered, albeit with limitations. This seems better than having no answer at all.

Pragmatism also informed the choice of Google Scholar as the database, for reasons described in the methods. However this pragmatic approach does come with additional limitations. For example it is very difficult to systematically capture and report the results of searches conducted using Google Scholar. This makes it near impossible to meaningfully present search results in a flow chart, as recommended by (for example) PRISMA guidelines (Liberati et al., 2009). This then raises two specific potential limitations. The first is whether another researcher could, using the methods described, repeat the study conducted here and obtain the same results. That should be possible given the search terms and the inclusion/exclusion criteria. A second limitation, not restricted to Google Scholar but compounded by it, is whether any samples have been missed by the search terms and the daisy-chaining from previous narrative reviews. It is impossible to prove a negative and so there may be samples that have not been identified. However the findings are fairly clear and consistent and are reproduced even when the sample is split in half. The typical sample size of the samples included here, as represented by the median sample size from the 71 samples included, is 365. This represents just 0.7% of the total sample reported here, and so even uncovering multiple additional typical samples would be unlikely to change the main findings.

Summary of Recommendations for Future Research on Contract Cheating

In order to address contract cheating, we need to understand it, and a basic question; “how common is it,” needs to be properly answered. Objective behavioral measures are clearly desirable. These could possibly be obtained using technological tools; the software company Turnitin has developed a tool to compare authorship across assignments (Turnitin, 2018), and this could yield interesting results to be compared with those obtained here. The size and scale of the essay mill industry could be thoroughly analyzed through financial records, and/or an analysis of the traffic to/from essay mills and search traffic related to their use/advertising. An analysis of cases detected across a broad sample of institutions with a large sample would also be helpful. Each of these approaches has limitations but a triangulation between data from these studies, including rigorous survey samples, would improve clarity.

Survey studies of self-reported behavior have a place, but in order to provide useful information they should be rigorous. This would be best conducted by an independent organization (i.e., not administered by staff at the university where the students are enrolled) and conducted on a defined, representative sample of the population. The instrument used would be piloted and validated with students to make sure that it is clear to participants that the survey is asking about contract cheating, with data collected anonymously and with ethical approval. Such an instrument could then be used repeatedly to obtain longitudinal data. There is also an urgent need to understand the reasons why students engage in commercial contract cheating and the characteristics of those students. This could come from a mixed-methods study of students who are known to have engaged in it and could then be used to stratify the sample for the aforementioned large survey, or to weight, or even just interpret, the findings.

There seems little value in further self-report studies from convenience samples, even large samples, particularly where we do not have a good grasp on even the basic demographics of the sample population.

Summary of Recommendations for Policy on Commercial Contract Cheating

The use of paid third parties by students does appear to be increasing. Improvements to assessment design, education, policy and the law all need to implemented in order to protect academic standards and quality, and the security of a university award. The use of face to face assessment methods (Newton and Lang, 2016), improved education and support for students (Newton, 2015) and staff (Ransome and Newton, 2017) and changes to the law to make provision of commercial contract cheating services illegal (Draper and Newton, 2017) could all limit the influence of contract cheating in Higher Education.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge colleagues for helpful discussion about the analysis and approach, and general encouragement to complete this paper, which started out as an idle search on Google Scholar, on a train in March 2017. In particular Dr Andrew Kemp, Ms Lety Kemp, Dr Lisa Wallace, and Professor Greg Fegan. The author would also like to acknowledge the hard work of all the academic integrity researchers whose studies were reviewed as part of this study.

References

Abukari, Z. (2016). Awareness and Incidence of Plagiarism Among Students of Higher Education: A Case Study of Narh-Bita College. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Ghana.

Ahmadi, A. (2014). Plagiarism in the Academic Context: a study of Iranian EFL Learners. Res. Ethics 10, 151–168. doi: 10.1177/1747016113488859

Anonymous (2013). Why I Write for an Essay Mill. Times Higher Education. http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/comment/opinion/why-i-write-for-an-essay-mill/2006074.article (Accessed 1 Aug, 2013).

Athanasou, J. A., and Olasehinde, O. (2002). Male and female differences in self-report cheating. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 8.

Babalola, Y. T. (2012). Awareness and Incidence of Plagiarism among Undergraduates in a Nigerian Private University. Afr. J. Lib. Arch. Inform. Sci. 22, 53–60.

Baetz, M., Zivcakova, L., Wood, E., Nosko, A., De Pasquale, D., and Archer, K. (2011). Encouraging active classroom discussion of academic integrity and misconduct in higher education business contexts. J. Acad. Ethics 9:217. doi: 10.1007/s10805-011-9141-4

Bailey, J., Tomar, D., and Chu, J. (2012). Paying for Plagiarism. Available online at: https://go.turnitin.com/webcast/paying-for-plagiarism

Balbuena, S. E., and Lamela, R. A. (2015). Prevalence, Motives, and Views of Academic Dishonesty in Higher Education. Text. Available online at: http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/doaj/23507756/2015/00000003/00000002/art00010

Bichler-Robertson, G., Potchak, M. C., and Tibbetts, S. (2003). Low self-control, opportunity, and strain in students' reported cheating behaviour. J. Crime Just. 26, 23–53. doi: 10.1080/0735648X.2003.9721169

Bishop, S., Drozd, J., Gosbin, D., and Guadalupe, V. (2009). Academic Dishonesty and the Use of Online Media Among Education Graduate Students. San Bernadino, CA: California State University, San Bernardino.

Bisping, T. O., Patron, H., and Roskelley, K. (2008). Modeling Academic Dishonesty: the role of student perceptions and misconduct type. J. Econ. Educ. 39, 4–21. doi: 10.3200/JECE.39.1.4-21

Boeker, M., Vach, W., and Motschall, E. (2013). Google scholar as replacement for systematic literature searches: good relative recall and precision are not enough. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 13:131. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-131

Bomford, A. (2016). The Man Who Helps Students to Cheat. BBC News. Available online at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-36276324

Bourassa, M. J. (2011). Academic Dishonesty: Behaviors and Attitudes of Students at Church-Related Colleges and Universities. University of Toledo. Available online at: https://etd.ohiolink.edu/pg_10?0::NO:10:P10_ACCESSION_NUM:toledo1302301033

Bretag, T., Harper, R., Burton, M., Ellis, C., Newton, P. M., Rozenberg, P., et al. (2018). Contract cheating: a survey of Australian University Students. Stud. High. Educ. 1–20. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2018.1462788

Brimble, M., and Stevenson-Clarke, P. (2005). Perceptions of the prevalence and seriousness of academic dishonesty in Australian Universities. Aus. Educ. Res. 32, 19–44.

Butt, S., Widdop, S., and Winstone, E. (2016). “The role of high quality surveys in political science research,” in Handbook of Research Methods and Applications in Political Science, eds H. Keman and J. J. Wodendoorp (Camberley, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing), 262–280.

Carpenter, D. D., Harding, T. S., Finelli, C. J., Montgomery, S. M., and Passow, H. J. (2006). Engineering students' perceptions of and attitudes towards cheating. J. Eng. Educ. 95, 181–194. doi: 10.1002/j.2168-9830.2006.tb00891.x

Christensen-Hughes, J. M., and McCabe, D. L. (2006). Academic misconduct within higher education in Canada. Can. J. High. Educ. Toronto 36, 1–21.

Clarke, R., and Lancaster, T. (2007). “Establishing a systematic six-stage process for detecting contract cheating,” in 2nd International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Applications, 2007, (New York, NY: ICPCA 2007), 342–247.

Clarke, R., and Lancaster, T. (2013). “Commercial aspects of contract cheating,” in Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Innovation and Technology in Computer Science Education (New York, NY: ITiCSE'13; ACM) 219–224.

Cook, H. (2017). Cheating “Hot Spots”: The Crackdown on Contract Cheating in Universities. The Sydney Morning Herald. Available online at: https://www.smh.com.au/national/cheating-hot-spots-the-crackdown-on-contract-cheating-in-universities-20171003-gytifj.html

Curtin, R., Presser, S., and Singer, E. (2000). The effects of response rate changes on the index of consumer sentiment. Public Opin. Q. 64, 413–428. doi: 10.1086/318638

Curtis, G. J., and Clare, J. (2017). How prevalent is contract cheating and to what extent are students repeat offenders? J. Acad. Ethics 2, 115–24. doi: 10.1007/s10805-017-9278-x

Curtis, G. J., Gouldthorp, B., Thomas, E. F., O'Brien, G. M., and Correia, H. M. (2013). Online Academic-Integrity Mastery Training May Improve Students' Awareness of, and Attitudes Toward, Plagiarism. Psychol. Learn. Teach. 12, 282–289. doi: 10.2304/plat.2013.12.3.282

Curtis, G. J., and Popal, R. (2011). An examination of factors related to plagiarism and a five-year follow-up of plagiarism at an Australian University. Int. J. Educ. Integr. 7. doi: 10.21913/IJEI.v7i1.742

Curtis, G. J., and Vardanega, L. (2016). Is plagiarism changing over time? A 10-year time-lag study with three points of measurement. Higher Educ. Res. Dev. 35, 1167–1179. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2016.1161602

Dayton, C. M., and Scheers, N. J. (1997). “Latent class analysis of survey data dealing with academic dishonesty,” in Applications of Latent Trait and Latent Class Models in the Social Sciences, 172–180.

Dickerson, D. (2007). Facilitated plagiarism: the saga of term-paper mills and the failure of legislation and litigation to control them. Villan. Law Rev. 52:21.

Dodd, T. (2018). Go8 Seeks Funding Details. The Australian, 2018. Available online at: https://www.theaustralian.com.au/higher-education/budget-2018-19bn-research-infrastructure-fund-welcomed/news-story/fbb4c48496b0f331ffd8530f6810ee0e

Draper, M. J., Ibezim, V., and Newton, P. M. (2017). Are essay mills committing fraud? an analysis of their behaviours vs the 2006 Fraud Act (UK). Int. J. Educ. Integr. 13:3. doi: 10.1007/s40979-017-0014-5

Draper, M. J., and Newton, P. M. (2017). A legal approach to tackling contract cheating? Int. J. Educ. Integr. 13:11. doi: 10.1007/s40979-017-0022-5

Ellis, C., Zucker, I. M., and Randall, D. (2018). The infernal business of contract cheating: understanding the business processes and models of academic custom writing sites. Int. J. Educ. Integr. 14:1. doi: 10.1007/s40979-017-0024-3

Eret, E., and Ok, A. (2014). Internet plagiarism in higher education: tendencies, triggering factors and reasons among teacher candidates. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 39, 1002–1016. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2014.880776

Erickson, M. L., and Smith, W. B. (1974). On the relationship between self-reported and actual deviance: an empirical test. Humboldt J. Soc. Relat. 1, 106–113.

Eve, R., and Bromley, D. (1981). Scholastic dishonesty among college undergraduates parallel tests of two sociological explanations. Youth Soc. 13, 3–22.

Fanelli, D. (2009). How many scientists fabricate and falsify research? A systematic review and meta-analysis of survey data. PLoS ONE 4:e5738. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005738

Franklyn-Stokes, A., and Newstead, S. E. (1995). Undergraduate cheating: who does what and why? Stud. High. Educ. 20, 159–172. doi: 10.1080/03075079512331381673

Gardner, W. M., Roper, J. T., Gonzalez, C. C., and Simpson, R. G. (1988). Analysis of cheating on academic assignments. Psychol. Record 38, 543–555. doi: 10.1007/BF03395046

Gaskill, M. (2014). Cheating in Business Online Learning: Exploring Students Motivation, Current Practices and Possible Solutions. Theses, Student Research, and Creative Activity, Department of Teaching, Learning and Teacher Education. Available online at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/teachlearnstudent/35

Genereux, R. L., and McLeod, B. A. (1995). Circumstances surrounding cheating: a questionnaire study of college students. Res. High. Educ. 36, 687–704. doi: 10.1007/BF02208251

Gorard, S., Rushforth, K., and Taylor, C. (2004). Is there a shortage of quantitative work in education research? Oxford Rev. Educ. 30, 371–95. doi: 10.1080/0305498042000260494

Goyder, J., Warriner, K., and Miller, S. (2002). Evaluating Socio-Economic Status (SES) bias in survey nonresponse. J. Offic. Statist. 18, 1–11.

Greene, A. S., and Saxe, L. (1992). Everybody (Else) Does It: Academic Cheating. Available online at: https://eric.ed.gov/?q=%22cheating+survey%22&id=ED347931

Guthrie, C. L. (2009). Plagiarism and Cheating: A Mixed Methods Study of Student Academic Dishonesty. Thesis, The University of Waikato. Available online at: https://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/handle/10289/4282

Haddaway, N. R., Collins, A. M., Coughlin, D., and Kirk, S. (2015). The role of google scholar in evidence reviews and its applicability to grey literature searching. PLoS ONE 10:138237. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138237

Halbesleben, J. R. B., and Whitman, M. V. (2013). Evaluating survey quality in health services research: a decision framework for assessing nonresponse bias. Health Serv. Res. 48, 913–930. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12002

Hard, S. F., Conway, J. M., and Moran, A. C. (2006). Faculty and college student beliefs about the frequency of student academic misconduct. J. High. Educ. 77, 1058–1080. doi: 10.1080/00221546.2006.11778956

Harper, R., Bretag, T., Burton, M., Ellis, C., Newton, P. M., Rozenberg, P., et al. (2018). Contract cheating: a Survey of Australian University Staff. Stud. High. Educ. 1–17. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2018.1462789

Hart, L., and Morgan, L. (2010). Academic integrity in an online registered nurse to baccalaureate in nursing program. J. Cont. Educ. Nurs. 41, 489–505. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20100701-03

Haunberger, S. (2011). To participate or not to participate: decision processes related to survey non-response. Bull. Sociol. Methodol. 109, 39–55. doi: 10.1177/0759106310387721

Henry, R., Flyn, C., and Glass, K. (2014). £630 and I'll Put You on the Way to a First, 2014. Available online at: http://www.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/news/article1422913.ece

Hensley, L. C., Kirkpatrick, K. M., and Burgoon, J. M. (2013). Relation of gender, course enrollment, and grades to distinct forms of academic dishonesty. Teach. High. Educ. 18, 895–907. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2013.827641

Hilbert, G. A. (1985). Involvement of nursing students in unethical classroom and clinical behaviors. J. Profess. Nurs. 1, 230–234. doi: 10.1016/S8755-7223(85)80160-5

Hilbert, G. A. (1987). Academic fraud: prevalence, practices, and reasons. J. Profess. Nurs. 3, 39–45. doi: 10.1016/S8755-7223(87)80026-1

Hilbert, G. A. (1988). Moral development and unethical behavior among nursing students. J. Profess. Nurs. 4, 163–167. doi: 10.1016/S8755-7223(88)80133-9

Hosny, M., and Fatima, S. (2014). Attitude of students towards cheating and plagiarism: University Case Study. J. Appl. Sci. 14, 748–757. doi: 10.3923/jas.2014.748.757

Hunt, S. (2017). Students' Use of Contract Cheaters Who Auction off Homework to Dark Web Ghostwriters Rising, Professor Warns | CBC News. CBC News Canada, 2017. Available online at; http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/contract-cheating-international-day-of-action-contract-cheating-1.4360193

IJEI (2017). The Rise of Contract Cheating in Higher Education: Academic Fraud Beyond Plagiarism. 2017. Available online at: https://www.springeropen.com/collections/cche

Irish Legal News (2017). “Essay Mills” to Be Subject to Prosecution under New Law. Irish Legal News. Available online at: http://www.irishlegal.com/7279/essay-mills-to-be-subject-to-prosecution-under-new-law/ (Accessed May 15, 2017).

Jamali, H. R., and Nabavi, M. (2015). Open access and sources of full-text articles in google scholar in different subject fields. Scientometrics 105, 1635–1651. doi: 10.1007/s11192-015-1642-2

Jones, S., Johnson-Yale, C., Millermaier, S., and Pérez, F. S. (2008). Academic Work, the Internet and U.S. College Students. Internet High. Educ. 11, 165–177. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2008.07.001

Junger-Tas, J., and Marshall, I. H. (1999). The self-report methodology in crime research. Crime Just. 25, 291–367. doi: 10.1086/449291

Juni, S., Gross, J., and Sokolowska, J. (2006). Academic cheating as a function of defense mechanisms and object relations. Psychol. Reports 98, 627–639. doi: 10.2466/pr0.98.3.627-639

Kayaoglu, M. N., Erbay, S., Flitner, C., and Saltaş, D. (2016). Examining students' perceptions of plagiarism: a cross-cultural study at tertiary level. J. Further High. Educ. 40, 682–705. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2015.1014320

Kidwell, L. A., and Kent, J. (2008). Integrity at a distance: a study of academic misconduct among university students on and off campus. Account. Educ. 17, S3–S16. doi: 10.1080/09639280802044568

Kirkland, K. (2009). Academic Honesty: Is What Students Believe Different From What They Do? Leadership Studies Ed.D. Dissertations. Available onlinbe at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/leadership_diss/38

Lambert, K., Ellen, N., and Taylor, L. (2006). Chalkface challenges: a study of academic dishonesty amongst students in New Zealand Tertiary Institutions. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 31, 485–503. doi: 10.1080/02602930600679415

Lancaster, T., and Clarke, R. (2016). “Contract cheating: the outsourcing of assessed student work,” in Handbook of Academic Integrity, ed T. Bretag (Singapore: Springer), 639–654. doi: 10.1007/978-981-287-098-8_17

Ledesma, R. G. (2011). Academic dishonesty among undergraduate students in a Korean University. Res. World Econ. 2:25. doi: 10.5430/rwe.v2n2p25

Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P., et al. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 6:e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100

Liebler, R. (2016). Collecting and reporting self-reports of the number of times cheated. College Student J. 50, 95–101.

Lim, V. K. G., and See, S. K. B. (2001). Attitudes toward, and intentions to report, academic cheating among students in Singapore. Ethics Behav. 11, 261–274. doi: 10.1207/S15327019EB1103_5

Mahmood, Z. (2009). Contract cheating: a new phenomenon in cyber-plagiarism. Commun. IBIMA 10, 93–97.

Mattei, N. (2009). Measuring the Effectiveness of a Required Ethics Class in an Undergraduate Engineering Curriculum. New Orleans, LA: American Society for Engineering Education.

Matthews, D. (2013). Essay Mills: University Course Work to Order. Times Higher Education. October 2013. Available online at: http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/features/essay-mills-university-course-work-to-order/2007934.article

Maxwell, A., Curtis, G. J., and Vardanega, L. (2008). Does culture influence understanding and perceived seriousness of plagiarism? Int. J. Educ. Integr. 4. doi: 10.21913/IJEI.v4i2.412

McCabe, D. L. (2016). “Cheating and honor: lessons from a long-term research project,” in Handbook of Academic Integrity, ed T. Bretag (Singapore: Springer), 187–198. doi: 10.1007/978-981-287-098-8_35

Megehee, C. M., and Spake, D. F. (2008). The impact of perceived peer behavior, probable detection and punishment severity on student cheating behavior. Market. Educ. Rev. 18, 5–19. doi: 10.1080/10528008.2008.11489033

Mulisa, F. (2015). The prevalence of academic dishonesty and perceptions of students towards its practical habits: implication for quality of education. Sci. Technol. Arts Res. J. 4, 309–315. doi: 10.4314/star.v4i2.43

Newstead, S. E., Franklyn-Stokes, A., and Armstead, P. (1996). Individual differences in student cheating. J. Educ. Psychol. 88, 229–241.

Newton, P. M. (2015). Academic integrity: a quantitative study of confidence and understanding in students at the start of their higher education. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 41, 482–497. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2015.1024199

Newton, P. M., and Lang, C. (2016). “Custom essay writers, freelancers, and other paid third parties,” in Handbook of Academic Integrity, ed T. Bretag (Singapore: Springer), 249–271. doi: 10.1007/978-981-287-098-8_38

Nonis, S., and Swift, C. (1998). Deterring cheating behavior in the marketing classroom: an analysis of the effects of demographics, attitudes, and in-class deterrent strategies. J. Market. Educ. 20, 188–199. doi: 10.1177/027347539802000302

O'Malley, M., and Roberts, T. S. (2012). Plagiarism on the rise? combating contract cheating in science courses. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Math. Educ. 20, 16–24.

O'Neill, H. M., and Pfeiffer, C. A. (2012). The impact of honour codes and perceptions of cheating on academic cheating behaviours, especially for MBA bound undergraduates. Account. Educ. 21, 231–245. doi: 10.1080/09639284.2011.590012

Park, E., Park, S., and Jang, I. (2013). Academic cheating among nursing students. Nurse Educ. Tod. 33, 346–352. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2012.12.015

Pupovac, V., and Fanelli, D. (2015). Scientists admitting to plagiarism: a meta-analysis of surveys. Sci. Eng. Ethics 21, 1331–1352. doi: 10.1007/s11948-014-9600-6

QAA (2017). Contracting to Cheat in Higher Education - How to Address Contract Cheating, the Use of Third-Party Services and Essay Mills. QAA. Available online at: http://www.qaa.ac.uk:80/publications/information-and-guidance/publication?PubID=3200

Quintos, M. A. M. (2017). A study on the prevalence and correlates of academic dishonesty in four undergrdauate degree programmes. Asia Pacific J. Multidiscip. Res. 5, 135–154.

Ransome, J., and Newton, P. M. (2017). Are we educating educators about academic integrity? A study of UK higher education textbooks. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 43, 126–137. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2017.1300636

Rigby, D., Burton, M., Balcombe, K., Bateman, I., and Mulatu, A. (2015). Contract cheating & the market in essays. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 111, 23–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2014.12.019

Roth, R. (2017). The Effect of Enrollment Status on Plagiarism Among Traditional and Non-Traditional Students. Doctoral Dissertations and Projects. Available online at: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/doctoral/1407

Rowland, S., Slade, C., Wong, K., and Whiting, B. (2017). “Just Turn to Us”: the persuasive features of contract cheating websites. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 1–14. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2017.1391948

Rowland, S., Slade, C., Wong, K.-S., and Whiting, B. (2018). ‘Just turn to us’: the persuasive features of contract cheating websites. Assess. Eval. Higher Educ. (2018) 43, 652–665. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2017.1391948

Rumbough, T. (2001). Controversial Uses of the Internet by College Students. University of Pennsylvania. Available online at: https://www.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/CSD1618.pdf

Scanlon, P. M., and Neumann, D. R. (2002). Internet plagiarism among college students. J. Coll. Stud. Develop. 43, 374–385.

Scheers, N. J., and Dayton, C. M. (1987). Improved estimation of academic cheating behavior using the randomized response technique. Res. High. Educ. 26, 61–69. doi: 10.1007/BF00991933

Selwyn, N. (2008). “Not Necessarily a Bad Thing …”: a study of online plagiarism amongst undergraduate students. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 33, 465–479. doi: 10.1080/02602930701563104

Sendag, S., Duran, M., and Fraser, M. R. (2012). Surveying the extent of involvement in online academic dishonesty (e-Dishonesty) related practices among university students and the rationale students provide: one university's experience. Comput. Hum. Behav. 28, 849–860. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2011.12.004

Shaughnessy, M. F. (1988). The Psychology of Cheating Behavior, Available online at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED303708

Sheard, J., Dick, M., Markham, S., Macdonald, I., and Walsh, M. (2002). “Cheating and plagiarism: perceptions and practices of first year IT students,” in Proceedings of the 7th Annual Conference on Innovation and Technology in Computer Science Education (New York, NY: ACM; ITiCSE'02), 183–187.

Sheard, J., Markham, S., and Dick, M. (2003). Investigating differences in cheating behaviours of IT undergraduate and graduate students: the maturity and motivation factors. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 22, 91–108. doi: 10.1080/0729436032000056526

Smith, T. R., Langenbacher, M., Kudlac, C., and Fera, A. G. (2013). Deviant reactions to the college pressure cooker: a test of general strain theory on undergraduate students in the United States. Int. J. Crim. Just. Sci. 8, 88–104.

Spaulding, M. (2009). Perceptions of Academic Honesty in Online vs. Face-to-Face Classrooms. J. Interact. Online Learn. 8, 183–198.

Stella-Maris, O., and Awala-Ale, A. (2017). Exploring students' perception and experience of ghostwriting and contract cheating in Nigeria higher education institutions. World J. Educ. Res. 4:551. doi: 10.22158/wjer.v4n4p551

Stephens, J. M., Young, M. F., and Calabrese, T. (2007). Does moral judgment go offline when students are online? A comparative analysis of undergraduates' beliefs and behaviors related to conventional and digital cheating. Ethics Behav. 17, 233–254. doi: 10.1080/10508420701519197

Stogner, J. M., Miller, B. L., and Marcum, C. D. (2013). Learning to E-Cheat: a criminological test of internet facilitated academic cheating. J. Crim. Just. Educ. 24, 175–199. doi: 10.1080/10511253.2012.693516

Sullivan, A., and Calderwood, L. (2017). “Surveys: longitudinal, cross-sectional and trend studies,” in The BERA/SAGE Handbook of Educational Research: Two Volume Set, eds D. Wyse, N. Selwyn, E. Smith, and L. Suter (London: SAGE Publications Ltd.), 395–415. doi: 10.4135/9781473983953.n20

Tennant, P., and Duggan, F. (2008). Academic Misconduct Benchmarking Research (AMBeR) Project Part II Executive Summary. Projects. Available online at: http://www.heacademy.ac.uk/assets/documents/AMBeR_PartII_Summary.pdf

TEQSA (2017). Good Practice Note: Addressing Contract Cheating to Safeguard Academic Integrity | Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency. Available online at: https://www.teqsa.gov.au/latest-news/publications/good-practice-note-addressing-contract-cheating-safeguard-academic

Turner, C. (2017). University Lecturers Are Topping up Earnings by Helping Students Cheat, Review Suggests. The Telegraph. Available online at: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/education/2017/10/07/university-lecturers-topping-earnings-helping-students-cheat/ (Accessed Oct. 7, 2017).

Turnitin, R. G. (2018). Turnitin - Authorship Investigation. Turnitin. Available online at: http://turnitin.com/en_us/authorship-investigation

Unesco, R. G. (2017). Six Ways to Ensure Higher Education Leaves No One Behind. 30. Available online at: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002478/247862E.pdf

Usborne, S. (2017). Essays for Sale: The Booming Online Industry in Writing Academic Work to Order. The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2017/mar/04/essays-for-sale-the-booming-online-industry-in-writing-academic-work-to-order (Accessed March 4, 2017).

Wajda-Johnston, V. A., Handal, P. J., Brawer, P. A., and Fabricatore, A. N. (2001). Academic dishonesty at the graduate level. Ethics Behav. 11, 287–305. doi: 10.1207/S15327019EB1103_7

Walker, M., and Townley, C. (2012). Contract cheating: a new challenge for academic honesty? J. Acad. Ethics 10, 27–44. doi: 10.1007/s10805-012-9150-y

Wallace, M. J., and Newton, P. M. (2014). Turnaround time and market capacity in contract cheating. Educ. Stud. 40, 233–236. doi: 10.1080/03055698.2014.889597