Abstract

This paper argues that the significance of the Warnock Report after 40 years goes beyond the impact of its deliberations and recommendations on UK policy and practice and its wider international influence. The Report's significance also highlights the nature of provision for pupils with special educational needs (SEN) and disabilities and the changing context of policy making in contemporary liberal democratic society. This paper shows the strong inter-connection between SEN and inclusion with other aspects of educational provision as the basis for proposing that future policy directions depend on general policy processes. It then argues that policy for pupils with SEN illustrates the democratic deficits in educational and policy-making processes in general. It uses this analysis to conclude that without grappling with these bigger policy issues we cannot expect some crucial questions in the field to be addressed more coherently and convincingly either conceptually or practically. Drawing on a post-democracy political analysis (Crouch, 2000) and contemporary ideas about deliberative democracy (Fishkin, 2018), with a recognition of the plural values that underlie policy tensions (Dahl, 1982). It proposes an Education Framework Commission (EFC). The Commission would set policy priorities as a settlement that has the potential to reconcile plural and sometimes contrary value positions. It would aim to design a 10 year consensual educational policy framework, within which political parties and governments will work; a framework that could be renewed after this period. An EFC would cover all key aspects of education including designs for including the diversity of learners. Finding common ground between different social and political value perspectives involves deliberative democratic principles and approaches that could influence representative democratic policy making. Though this proposal arises in an English context it has international relevance to the project of renewing ideas and values about the nature of schooling in a way that takes genuine account of SEN and disabilities.

Introduction

The argument in this paper is that while commemorating the significance of the landmark Warnock Report published 40 years ago, we need to look at the policy context of provision for pupils with special educational needs (SEN). This is not just to examine how what counts as special educational provision is inter-connected with other aspects of educational provision, but also how SEN policy making is inter-connected to broader educational policy. It is mainly the policy and provision aspects of the Warnock Report that we are remembering in 2019.

In looking at the policy context of provision for this hard to define sub-group of pupils we also need to consider the quality of general educational policy making and ideas about how this can be improved. This takes us well beyond special needs and inclusive education to questions about the quality of educational and social policy making, with England as the main focus of the paper. This paper will address some of these matters and consider policy making ideas that go well beyond the kind of Government committee review so well-exemplified by the Warnock Committee. So, the paper will conclude that without grappling with these general policy issues we cannot expect some of the important questions in the SEN and inclusive education field to be addressed more coherently and more convincingly either conceptually or practically.

Policy Trends and Issues

The Warnock Committee was set up in 1974 by Margaret Thatcher, then Education Secretary (Minister of Education), with a broad remit that concluded in 1978 in a report of over 400 pages. There has not been a national review of this scale and thoroughness since as the breadth of chapter coverage and detail indicates. For example, its coverage of teacher education and training is as relevant today as it was 40 years ago. It presented 30 detailed recommendations covering all phases of teacher preparation, continuing professional development, and the importance of inter-professional training. It had a chapter about research and development in the field, covering the coordination of research, setting up a national Special Education Research Group, and considered how to translate research into practice.

The central legacy of the Warnock Report has been the concept of “special educational needs,” its identification and assessment for individual pupils and the planning of provision underpinned by statutory protections. Though the thinking about SEN had been developed earlier (Gulliford, 1971), it was the Committee's adoption and promotion of it that established its significance. However, many of the current policy and provision problems in this area can be attributed to this individualized focus in the Report as implemented in the 1981 educational legislation (National Archives, 2019). This legislative translation of the key Warnock concepts into the statutory system for assessment of SEN (Statementing system) has dominated the field right up to the latest changes in the Children and Families Act 2014. There has been little change in the basic system despite the refinements by successive governments. This is despite the latest legislation having been promoted as “a radically different system” [(Department for Education (DfE), 2011)]. The basic design of a protected individual identification and assessment system of additional needs and provision is still the cornerstone of the system. What has changed is the context of education policy and practice, and how the system is understood.

It was noted many years ago that while the Warnock Report's thinking about the SEN concept recognized a basic dilemma about the identification of some children as needing additional or different provision, it did not address the dilemma in its analysis of the education system and recommendations (Norwich, 1996). The Warnock position was for abandoning categories of educational handicap in order to avoid adverse labeling but promoted a new category of SEN in order to protect resources for a vulnerable minority. The Report stated that: “we have found ourselves on the horns of a dilemma” (page 45). It referred to it in these terms; abolishing statutory categories may give rise to concerns about protecting the interests of children with disabilities. Subsequently Mary Warnock herself acknowledged the problem at the heart of her Committee's Report some years later (Warnock, 1991).

The dilemma is whether to identify and risk stigma or whether not to identify and risk losing protected provision, which has been called the dilemma of difference (Minow, 1990; Norwich, 2008). It could be that by referring to a dilemma but not elaborating about the tensions and how to address them, it was likely that the 1981 legislation would ignore them.

This identification dilemma and other related dilemmas about differences in curriculum design and school placement for pupils with SEN reflect that provision for this identified group is both integral to general provision and a distinct aspect of education. It is a perspective which I have argued before contrasts with two other influential perspectives (Norwich, 1996). One is that SEN concerns what is additional to and different from ordinary education, that it is a specialization with separate institutional sub-systems and labeled professionals, training and associations. This is the position that is mainly to do with what is distinctive; and is represented by the English legislative system in how SEN was defined and put into operation for the last 40 years. The other perspective that contrasts with the integral/distinct one opposes any labeled identity for the field. In this perspective, which mostly focuses on what is integral, SEN is seen to arise from the inability of the mainstream education to include, accommodate and provide for the diversity of learners. Here the focus is on making the mainstream more responsive to, and inclusive of, diversity in order that difference need not lead to discrimination and be marked out with stigmatizing labels. This is what Cigman (2007) has called universal inclusion (an inclusion with no place for separate labels or systems) and is adopted by the Inclusion Index in operational terms (Booth and Ainscow, 2011).

In recognizing a third perspective that connects the integral and distinctive aspect of this field, I suggested that the concept of connective specialization might be useful (Norwich, 1996) and I continue to see its usefulness. It also relates to more recent ideas about inclusive special education (Hornby, 2015). Connective specialization refers to the interdependence of different specialisms and the sharing of a relatedness to the whole (Young, 1995). As a double-aspect concept it captures the link between contrary tendencies toward specialization and integration; the tensions between the values of meeting individual needs while doing so without marking out some children as different. The connective specialization concept therefore implies some balancing between distinctness and integralness (or inclusion, to use the current term). It stands against fixed dichotomies between one or other alternative, e.g., a focus on environmental barriers to be removed (social model) as opposed to focusing on difficulties (deficit model), or assessment being about individual needs as opposed to assessing children in terms of general categories. Connective specialization implies abandoning the opting for one side of the dichotomy to the exclusion of the other and denying any value to the other connected alternative.

Connective Specialization and the Inter-Dependence of the SEN System

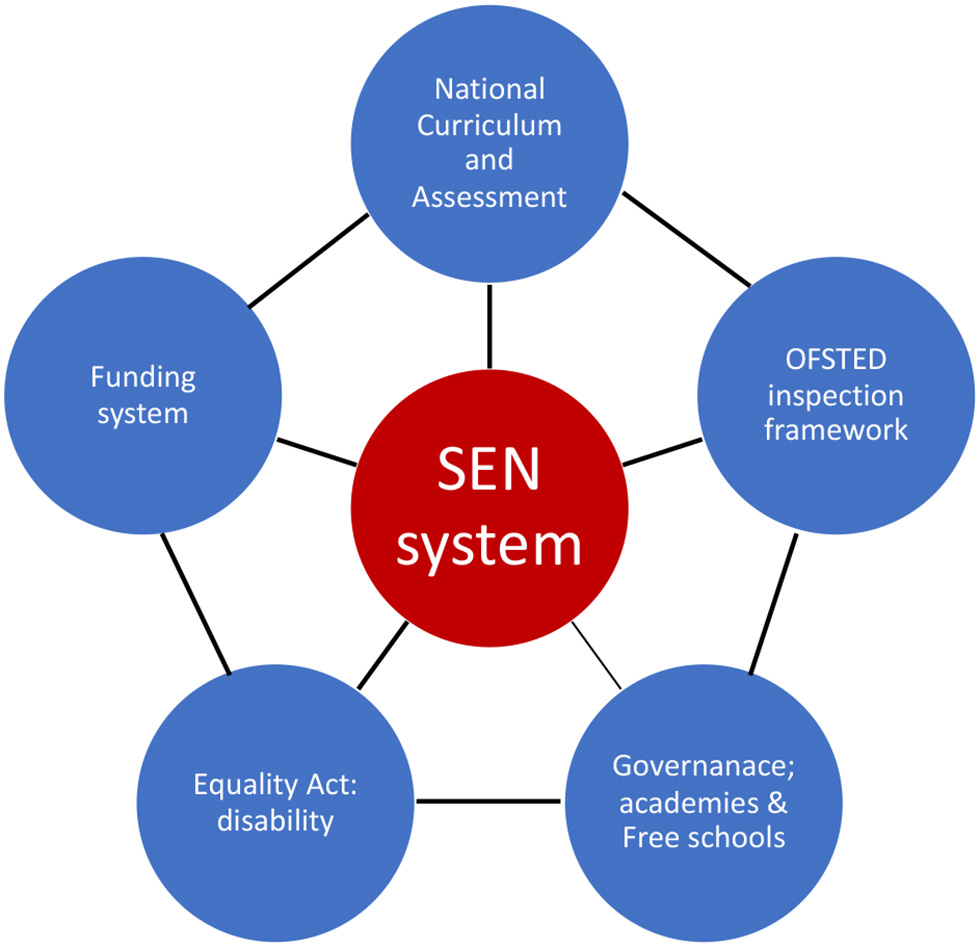

Connective specialization is relevant to understanding the position and inter-dependence of the SEN system with other parts of the English school education system. Figure 1 is a simplified mapping of the complex inter-dependency of the SEN system with other key sub-systems. Much of the current Code of Practice, which sets out guidance about assessment practices and provision for children and young people with SEN and disabilities covers the system of individual needs assessment and statutory provision protections, which is the responsibility of local authorities [(Department for Education (DfE), 2015)]. This continues in much detail and in an updated form, the kind of guidance set out in previous Codes of Practice in the SEN system. Though the Code refers to some of the other aspects of provision which are crucial to provision for those with SEN/disabilities, it does so in very general and superficial ways. For example, there is only one brief section on the school curriculum and SEN, which makes brief reference to the National Curriculum statement on inclusion [(Department for Education (DfE), 2015) section 6.12].

Figure 1

Interdependence of the SEN system with other sub-systems.

The current Code of Practice refers to SEN and disability using the acronym SEND without any commentary on the relationship between the parallel and overlapping system of disability discrimination legislation from 2001, now under the Equality Act 2010. This legislation introduced the dual systems of definitions, guidance and responsibilities which does not fit well the SEN system, either in where responsibilities lie or how the terms SEN and disability relate to each other. This unresolved matter is illustrated in how the “SEN” term has now been coupled with the term “disabilities” to the compound term SEND. While local authorities are responsible for issuing Education, Health and Care Plans (EHCPs; formerly Statements) which ensure legally protected provision, their powers have been weakened by the new governance system of Academies and Free schools (a form of state -funded independent schools), with greater reliance on market forces in the school system. The growth of Academies and Free schools since 2010 (influenced by the US Charter schools and Swedish friståendeskolors) has changed the landscape of schooling in mainstream, special schools and alternative provision. Academies now form into Multi-Academy Trusts (MATs) with member schools which may be geographically dispersed. Though Academies have to take account of the SEND Code of Practice, there have been concerns that Academies might have less commitment to the rights of pupils with SEN/disabilities (Black et al., 2019).

Figure 1 also shows the interdependence of the SEN system with the National Curriculum and assessment arrangements [(Department for Education (DfE), 2014)] and Ofsted accountability. Recent changes to the National Curriculum have resulted in a narrowing of what is learned and how it is assessed. Despite changes to the Office for Standards in Education (Ofsted) inspection framework, the centrality of the academic progress criteria has been retained (Douglas et al., 2017). As mentioned above, Figure 1 also represents the impact of reduced funding on, among other things, decreased support staffing in schools, and increased pressure from parents for more statutory assessment and EHCPs [(Department for Education (DfE), 2018)].

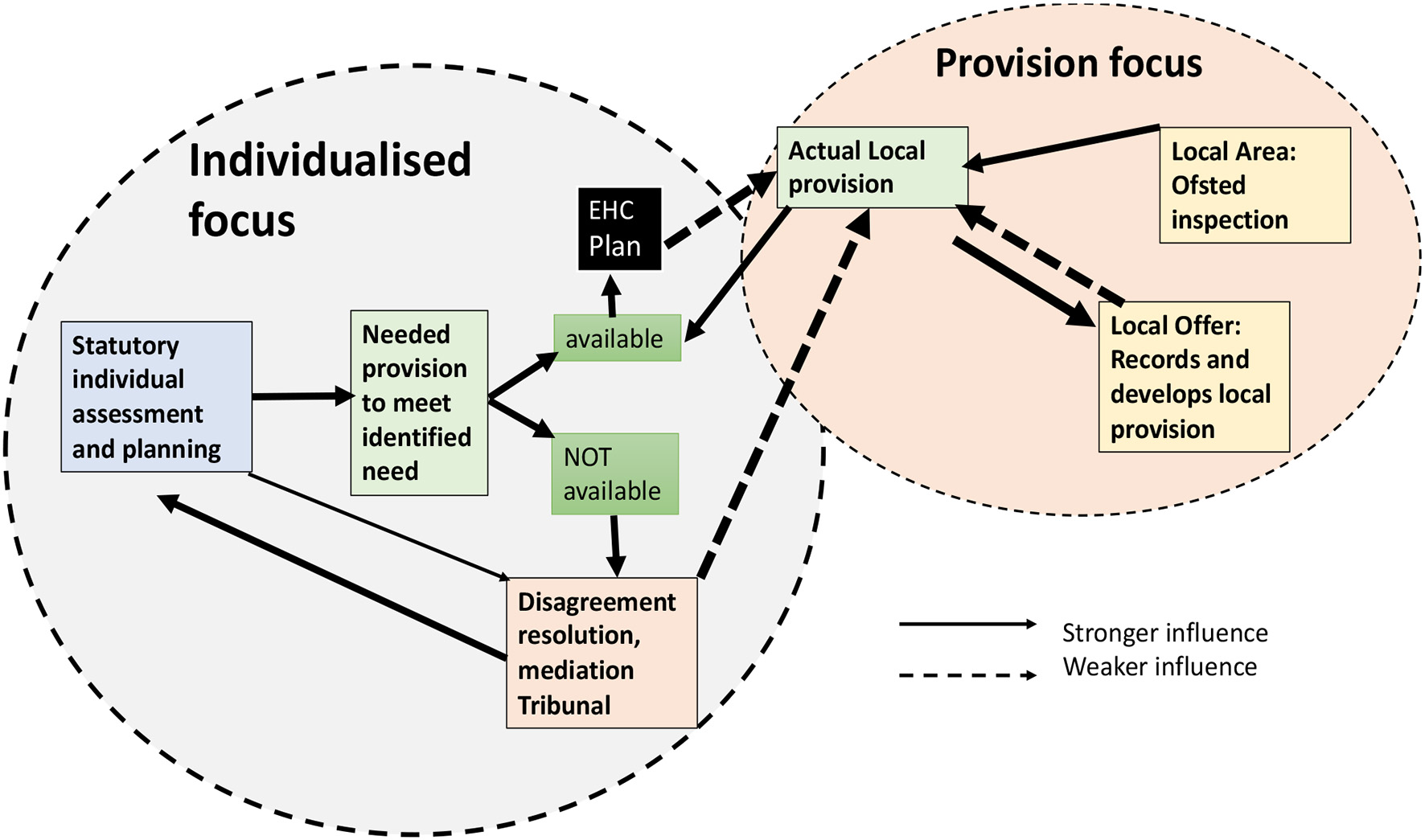

Based on this interdependence analysis, it is clear that the interests of those with SEN and disabilities require a broader position, one that focuses on the availability of provision and its adaptation and flexibility in inclusive ways. Figure 2 shows in a schematic way how the current system requires both an individual and also a provision focus. The historical legacy of the Warnock report through the 1981 legislation has been developed into a system of individual needs assessment and provision planning. The left-hand circle shows that the key decision in this process depends on the availability of needed provision. When it is unavailable this might lead to a disagreement between parents and the local authority which might be dealt with by disagreement resolution, mediation, and/or tribunal approaches. This process enables some fitting between what is considered to be needed and what is available, but not without the struggling and stress sometimes associated with this statutory provision decision making system. As Figure 2 shows what is available for an individual pupil depends on the actual system of provision in a local area, which is the center point of a provision-focused approach.

Figure 2

The inter-relationship between an individualized and provision focused approach.

Figure 2 also shows some weaker influences on actual local provision, the individual statutory need assessment processes, on one hand, and the Local Offer system, on the other. Under the latest SEN Code of Practice [(Department for Education (DfE), 2015)] the local offer is meant to not only provide information to parents and carers of children with SEN and disabilities about what additional provision is available to them. It is also to provide a process by which, through consultation, provision might be developed. This is, for example, one function of Parent and Carer Forums in the UK. However, whether such fora have the potential to influence the design of the pattern of provision in an area is doubtful given the split between middle tier governance local authorities and the regional school commissioners that oversee academies. Though the new SEN Code recognizes the relationship between individual EHC Plans and population needs for provision planning purposes [(Department for Education (DfE), 2015) p. 43], there is no clear operational system that connects these foci. This overview of the weak contemporary systems for reviewing and developing actual provision for pupils with SEN is also underlined by a lack of a coherent and well-grounded national strategy about what is meant by inclusion in school education and how it might be put into operation (SEN Policy Research Forum, 2016).

The legal protections currently used for individualized assessment and provision planning, a Warnock legacy, could also apply to appropriate general provision. This would involve developing a provision-focused approach, while managing the relationship between it and an individualized focused approach. The implication is that there could be a reduced focus on individual assessment and provision planning, and more focus on general provision planning for those with SEN with a presumption for inclusive arrangements. This could translate into providing statutory assessment only when parents opt for it, in contrast to current statutory system for all individual plans. A legacy of the focus on planning for individual needs, which stemmed from the Warnock Report, has been too much focus on individual needs assessment and the neglect of protections for the planning of the general system of provision.

Broader Policy Framework and Perspective

So, there is a need to adopt a broader policy framework in which SEN and disability in education is seen to be interconnected with other aspects of education, on one hand, and for more balance between an individualized and provision-focused approach, on the other. This inevitably has to be seen in terms of issues about: the general system and its specialization; education markets and their regulation; the public sector and its relationship to the private sector; the relationship between national, local and school responsibilities (Norwich, 2014). As the introduction of the EHC Plan process shows, the SEN framework goes beyond education into other areas of national policy, such as health and social services. How provision for pupils with SEN and disability is designed is part of general policy and political decision-making.

What follows is also informed by a perspective that recognizes that policy depends on several basic values, which can sometimes be compatible, but several values can also come into tension during the process of policy formation. The discussion above about how the Warnock Report recognized a dilemma of difference over SEN identification, but did not carry through with its analysis of policy dilemmas, is the basis for this broader policy framework. This framework derives from various theorists who have suggested plural values can result in tensions that can lead to dilemmas of plural democracy (Dahl, 1982; Berlin, 1990). There are possible tensions between: equality (same) vs. equity (fairness); choice (preference) vs. equity (fairness); participation (own agency) vs. protection (other's agency) n; and difference as enabling vs. difference as stigmatizing. In recognizing plural values, it means that when these values cannot be reconciled fully, there may need to be some balancing, some hard choices with some loss of what is valued. To have, for example, choice and equity, some balancing or “trade-off” is required (Norwich, 2014).

This policy dilemma analysis needs to be set within the current political context. Here, Crouch's (2000) post-democracy perspective is also relevant to this analysis of education policy. In a post-democracy view, there are elections with governments falling and there is freedom of speech. But democracy has become progressively limited, as shown by: a small, detached elite taking tough decisions; abuses of democratic institutions; politicians having a poor reputation and lacking trust with the population through the use of spin and hype; and policy development seen in terms of political expedience. For example, in a recent extensive study of diverse citizens across England to explore the depth and variety of views about contemporary society (Gaston, 2018), the political class was regarded with hostility and sometimes disdain. Though some individual politicians were not subject to such criticism, there was also disapproval of the professionalization of politics and concerns about disconnection from ordinary people.

As causes of post-democracy, Crouch (2000) identified: (i) privatization, the entanglement of public and private sectors, and globalization; (ii) fewer common goals for diverse groups to identify with, more divisiveness, and the rise of populist parties; and (iii) unbalanced public debates with a poor-quality national discussion. More recently Crouch (2011) tends to support approaches that energize citizenship, including state funding of political parties and the use of citizen assemblies. The aim is to reclaim a central place in decision-making, perhaps through social media, to engage citizens in participating in public debates and join advocacy groups. As might be expected this perspective has been criticized for not seeing the potential for a major reversal, only for measures to mitigate the adverse effects of post-democracy. Such criticisms reflect disagreement with Crouch's position on economic markets. Crouch recognizes the strengths of the capitalist firm for its innovation and responsiveness to customers and so does not take a hostile view to what markets can do in some circumstances. But, he does recognize the damage that market behavior can cause (negative externalities: external costs on others with no compensation) and so advocates a form of social investment welfare state, a version of a mixed economy (Crouch, 2012).

Expressions of post-democracy can be seen in some of the recent trends in education policy and current failures of education policy formation. The introduction of the academies programme by the UK Coalition Government (2010–15) was a major move toward taking education governance out of local government influence. The issues associated with this move and the introduction of MATs set up a more market-oriented school system, even if it is not a full privatization, as in the cases of moving nationalized industries into the private sector (e.g., rail system). The 2010–15 UK government tended to deny positive accomplishments by the previous government. This was shown in the way that the UK Coalition Government, when introducing its plans for the new 2014 SEN legislation, denied the positive achievements of the previous Labor Government in this field (SEN Policy Research Forum, 2012). It has been argued that policies are adopted for short-term political gain with rhetorical policy zig-zagging, rather than for well-founded policy reasons for the longer term (Bell, 2015). As an example, the UK Advisory Committee for Mathematics Education called for better mathematics education policy that is “joined-up, long-term, evidence-informed, transparent and well-designed” [(Advisory Committee for Mathematics Education (ACME), 2014)]. There has been a break in the relationship between government policy and professional knowledge (for example, Government curriculum advisors resigning over National Curriculum reforms; Guardian, 2012). There is also a tendency to project and justify a false sense of certainty about education policy, with an unwillingness to recognize publicly education policy tensions and uncertainties.

Education Framework Commission

One way forward could be to establish an Education Framework Commission (EFC) to work on the assumption that policy should be formed as a settlement that reconciles contrary value positions. The Commission would aim to design a 10 year consensual educational policy framework, within which the current and future governments will work, and that would be renewed after this period. The aim of an EFC would be to:

Raise the level of national educational policy discussion and debate

Design a shared and informed medium-term (e.g., 10 year) education policy framework

Seek and maximize common ground across different social and political interests, outside the political market of politicians attracting voters at elections

Represent key stakeholders, including: representatives from political parties; teachers and school leaders; parent/carers; pupils; local authorities and middle tier organizations; key bodies, such as Ofsted; third sector and voluntary groups; employers and business; unions and professional associations, etc.

Break down unnecessary polarizations through adopting a position about the role of academic and professional research and evaluation in informing policy and practice

Lobby political parties and MPs to enact legislation to establish the 10 year binding Framework for future education legislation, along the lines of climate change and other cross-party initiatives and legislation.

An EFC could be seen as a response to the national post-democracy condition in attempting to raise the level of discussion and debate about education policy to consider issues of justice in education, the role of education in society, environmental sustainability, and the economy and how education can prepare for and influence these socio-economic changes, for example. It would be expected to relate directly to issues of human diversity and in that respect address issues of SEN and disability, not as isolated from other aspects of diversity and general design, as so often happens in the SEN and disability field. The idea is to have an organization that is independent of Government and the Department for Education. Bell (2015) as a former permanent secretary at the Department for Education has called for an independent body to set longer-term educational policy that is separate from the shifting demands of party politics. The EFC would contribute to this purpose, but the proposal is for it to be independently funded so that it does not act as a Government agency, though it would have strong links with the Department for Education, education agencies, politicians, and political parties. This independence from Government would give it more control over its agenda and working practices than if it were a Government agency.

It is clear that such an EFC would resemble some current practices, such as Parliamentary Select Committees and reviews, such as the Cambridge Primary Review (2009) and the Warnock Committee Enquiry, the focus on this paper. Table 1 illustrates some of the points of comparison between an EFC, Parliamentary Select Committee and previous Education Reviews

Table 1

| EFC | Select committee | Previous reviews e.g., Cambridge primary review | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relation to Government/Parliament | Independent | Related | Independent |

| Reflect different political ideology | Involve cross party ideology | Involve cross party ideology | Not explicitly |

| Extent of enquiry | In-depth and theory and research informed | To some extent | In-depth and theory and research informed |

| Public deliberation | Actively seek public deliberation | Calls for interest group evidence | Calls for interest group evidence |

| Coverage | Holistic overview | Focused topics | Middle level e.g., primary education |

Key points about EFC in relation to Select Committees and Previous Education Reviews.

Table 1 shows the ways in which the idea of an EFC is similar and distinctive from well-known review systems. An EFC would be similar to the Cambridge Review of Education in its independence and its use of in-depth enquiry that is theory and research informed. But, it would be different in the following ways: i. involving cross-party political positions; ii. producing a holistic framework that went beyond primary education and iii. actively seeking public deliberation. An EFC would resemble a Select Committee in involving cross-party political positions but differ in all the other aspects: the extent of enquiry, public deliberation and coverage. From this, it is clear that the EFC would be more like an Educational Review than a Select Committee but integrates elements from both systems.

An EFC would have some similarities to the recent Social Metrics Commission's (SMC) development of a new measure of poverty for the UK (Social Metrics Commission (SMC), 2018). The SMC presents itself as “an independent and rigorously non-partisan organization” to help policy makers and the public understand and take action to tackle poverty. It presents its goal as developing “new poverty metrics for the UK which will have both long-term political support and effectively identify those who are in poverty” [(Social Metrics Commission (SMC), 2018): p. 4]. It adopts an approach that brought together left and right-wing thinkers, policy and measurement experts and stakeholder consultations to agree on a final poverty measure. This consensual approach might be easier to achieve when there is a specific topic, like poverty metrics, than policy that bears on social justice positions related to education. An EFC also compares with the Institute for Public Policy Research's (IPPR, 2018) Commission on Economic Justice, established in 2016 after the UK referendum vote to leave the European Union. The Commission members were described as coming from “all walks of life and different political viewpoints” and having “voted on different sides of the EU referendum” (IPPR, 2018; p. 1). Though it was claimed that the Commission was independent of all political parties, there can be some doubts about how far the membership reflected a fuller range of political views, outside the scope usually associated with a “progressive think tank,” as the IPPR describes itself. Though the report describes the Economic Justice Commission as reaching a “remarkable degree of agreement,” given the “breadth of Commissioners”(IPPR, 2018: p. 1), little is said about where there were disagreements and conflicts of views and how they were handled. An EFC would resemble the IPPR's Economic Justice Commission more than the SMC's poverty metrics project, given the broad education framework at stake. However, the IPPR Commission differs from the idea of an EFC in that an EFC's purpose is to initiate a national conversation about education through public deliberation, not to arrive at a report that “can spark a national conversation on why we need a change of direction and what that direction should be” (page 1), as the IPPR Commission did.

Rationale for an EFC

Fishkin (2018) describes various types of democracies, including “competitive democracy,” the one most widely accepted in Western democracies, as one embodying electoral competition in a context of constitutional guarantees for individual rights. Using (Schumpeter, 1942) description of a competitive democracy as a “competitive struggle for the people's vote,” Fishkin argues that this form of democracy is less about reflecting a collective will than a process of forming the collective will, a kind of “manufactured will” which is the product of a competitive political process. Though constitutional guarantees protect against majority tyranny, election competition is what matters, when parties and candidates can mislead the voters. These points relate to contemporary and wide-spread mistrust of politicians and the political processes (Van der Meer, 2017).

Fishkin talks about two other forms of democracy, elite deliberation, and participatory democracy. The former involves elite conventions or bodies that consider competing arguments (e.g., constitutional conventions, the US Senate, or perhaps the UK House of Lords). But, as Fishkin argues, with party politics and elections determining the composition of these bodies, this can limit opportunities for representatives to deliberate. The latter, participatory democracy, emphasizes mass participation combined with equal counting. Though this might have an educational function, it does not enable deliberation. For Fishkin, it is deliberative democracy which combines deliberation with equal weighting of views through using what he calls a “deliberative microcosm.” This draws on ancient Athenian practices in modern forms, such as citizen assemblies (see below for current practices). So, for Fishkin (2018), deliberative democracy is a counter to the worst excesses of competitive democracy by asking the simple question: “What would the people think under good conditions for thinking about the issue in question? (Fishkin, 2018; p. 7)” It requires both external and internal validity; external validity with the assembly participants being representative of citizens and internal validity with deliberation done under good conditions to produce the final judgements. In his model, Fishkin sees a need to link deliberative democracy to the lawmaking process based on representative democracy, not to replace representative democracy. This model involves treating deliberative democratic forms as priority setting for representative democracy which he proposes can be done in advance, during, or after representative democratic procedures.

These ideas about deliberative democracy have been developed by contemporary philosophers. Habermas (1996), for instance, identified how the prospect of legitimacy is weak in modern societies given the potential for misunderstanding and conflict over what is good and right. The modernization process engenders pluralism and functional differentiation reducing the resources for consensual resolution of conflicts. This is where Habermas was keen to show how his theory of communicative action could have institutional impact with public discussion and debate over practical issues and questions. This was the basis for his discourse theory of deliberative democracy. Another philosopher, Sen (2009), known for his capability approach to social justice, saw public reasoning or deliberative democracy as central to his approach. Democracy was more than elections and votes, involving government by discussion, which includes “political participation, dialogue and public interaction (page 326).” For Sen, the political ideals of democracy—public participation, dialogue, and public interaction—can be distinguished from the institutional forms of contemporary democracy—competitive elections, political parties, and ballots. These forms are the means to the ideal and in this way Sen cautions against thinking that having these forms is the same as meeting the ideals. This opens up the prospect of developing other forms of democracy.

EFC: Opportunities and Risks

An EFC promises benefits but has risks too. It could be an opportunity to increase national participation in debates about education, and so increase understanding, which is itself a public and political educational activity. It would seek to involve people who disagree with each other to listen and engage with one another. This would be facilitated by activities taking place outside the electoral cycle (e.g., ahead or after elections). An EFC would involve a deliberative democratic approach and as Fishkin (2018) suggests this could contribute to priority setting in the representative democratic system.

Citizen assemblies (CA) as a form of deliberative democracy have come to public attention in the UK in the wake of the disagreements and uncertainties about Britain leaving the European Union (Brexit). CAs brings together a randomly selected and representative group Aof citizens to consider an issue or question through learning, deliberation, and decision-making over a fixed number of hours. Expert advice is provided to participants with facilitated discussion. A CA has been advocated and undertaken as a way of resolving differences about the UK's future relationship with the European Union (EU) (UCL Constitution Unit, 2017). CA have also had prominence with its use in Ireland to design the form of the referendum on the laws about abortion. Perhaps less well-known has been the use of a CA by two House of Commons Select Committees (Health and Social Care Committee; and Housing, Communities, and Local Government Committee). These committees commissioned a CA on the long-term funding of adult social care (INVOLVE House of Commons, 2018). INVOLVE is a UK public participation charity with a mission to put people at the heart of decision-making and support people and decision-makers to work together to solve challenges. INVOLVE is one of several UK organization that are members of Democracy R&D which is an international network of organizations and associations aiming to develop, implement, and promote ways to improve democracy1. This network is based on the assumption that democracy should include a role for randomly-selected everyday people, as in CAs. The growth of interest and use of CAs internationally is illustrated through the work of the Stanford University Center for Deliberative Democracy in the United States of America (USA) (Fishkin, 2018).

An EFC could not only be informed by CA strategies but other current or developing approaches. Finding common ground between opposing educational perspectives is very challenging, so there is a place for established conflict resolution strategies. It could be argued that the current acute social divisions and policy crises have been more pronounced than for a long time. This post-democracy situation, as described above, could be seen to have led to the rise of populist and nationalist politics, calling more than before for citizens to engage with different views and find common ground. The “More in Common” organization has been recently set up as a charity in memory of the assassination of the MP Jo Cox who stood for this approach. This is a new international initiative which aims to build communities and societies that are stronger, more united and more resilient to the increasing threats of polarization and social division. Their approach is to “develop and deploy positive narratives that tell a new story of “us,” celebrating what we all have in common rather than what divides us”2. This involves needing to move out of personal comfort zones, seeking out difficult debates, searching out people we disagree with and listening to them before reacting to their views. This seeking of common ground can be seen as a way of coping with the tensions between positive and negative qualities and integrating them into a cohesive and realistic whole, whether in relation to self, others or socio-political values. When this cannot be achieved there is splitting, a kind of either—or, and all-or-nothing thinking or a good-or-bad feeling, which can be understood as a defense mechanism as theorized in psychoanalytic object relation theory (Fairbairn, 1994). So, the More in Common approach from this perspective avoids the excesses of denigration and idealization.

These More in Common ideas have an affinity with implications drawn from (Haidt, 2012) moral psychology which he used to argue for ways of fostering collaboration between partisan opponents. Based on these ideas a bipartisan working group was convened in the USA under the auspices of two established and well-known US think-tanks with opposing ideological orientations. This group produced a consensual plan for reducing poverty based on opportunity, responsibility and security (AEI/Brookings, 2015). This US initiative goes beyond the UK initiative discussed above to develop a new consensual measure of poverty (Social Metrics Commission (SMC), 2018). It is an example of one of the elements of the core idea of an EFC.

There are two other approaches which are relevant to how an EFC might function, one promoted by a voluntary organization (Citizen Shift)3 and the other by an international agency (the OECD). The former is the “citizen shift” idea and approach (New Citizenship, 2014) which assumes that western democracies have reached the limits of a consumer identity as the dominant model of the relationship between individuals and the economy and society. This organization promotes the alternative idea of the citizen, which is not just about the freedom to choose between options, but being active in forming those options. This is seen to involve a shift from representative to participatory democracy and for business to shift from profit to purpose. These shifts are not either-or but expand on the consumer idea. So, profits are to be made, but with more emphasis on explicit service of social or environmental purposes. These ideas have clear links with the participative democratic ones, discussed above, the idea that shifts do not mean abandoning fully what has been dominant before. The other approach relevant to an EFC is the approach called “futures thinking” which involves taking a longer-term perspective on the future rather than the common short term focus often associated with the contemporary business model and consumerism. There is a tradition of futures thinking in education and in relation to SEN and inclusive education (Black, 2018) both for school teaching and for policy making (OECD, 2018). The OECD have promoted futures thinking as a perspective that goes beyond the confines of immediate and short-term constraints. Based on the assumption that current attitudes and action frameworks are open to change, the OECD has established an initiative about Schooling for Tomorrow (SfT) using expert analyses, case studies, country reports, and publications. This has included materials with strategies that show how groups can initiate futures thinking in education. These approaches have direct relevance to an EFC.

Nevertheless, it would be very challenging to establish an EFC, not only in terms of its funding base and the scope of the framework to be designed but how far it reflected common ground between participants with opposing positions. The aim would be to formulate the Framework in as specific terms as possible to avoid excessive use of constructive ambiguity. However, it would be expected that the Framework would be open to some degree of interpretation in specific policy-making by political parties, so enabling ideological differences to emerge at election time. Despite this, an EFC could reconnect policymakers with citizens by being responsive to parents/carers, children and young people, and professional and citizen interests, and so raise the policy horizons about the education system.

There are further risks with an EFC. One is that EFC could become marginalized by not managing to engage a wide group of stakeholders with diverse enough views, values and affiliations. It might also not engage key members of political groupings and parties. However, this depends on how it is set up in the first instance. The inclusiveness of the EFC process is built into the citizen assembly method of involving representative participants, but using CAs to construct a broad-based framework will be a continuing challenge. An EFC type of organization might also be captured by a group not committed to its principles. This calls for some scrutiny system with powers to intervene in the running of the EFC organization. Achieving consensus beyond vague generalities might also prove to be very hard to achieve. However, the process is worthwhile despite these risks and challenges if only to find out how far the process can be taken and where there are pitfalls. This is an opportunity for learning about educational policy making and change.

Concluding Comments: Implications For Special Needs and Inclusive Education

This paper has proposed that the significance of the Warnock Report of 40 years ago goes beyond its deliberations, recommendations, and its policy and practice legacy and impact. The Report's significance is also to highlight the nature of provision for pupils with SEN and disabilities and the changing context of policy making in contemporary society. The key point in this paper is that given the strong inter-connection between SEN and inclusion with other aspects of educational provision, future policy directions depend on general policy processes. This calls for a perspective well beyond special needs and inclusive education to one about the quality of general educational and social policy making that takes account of diversity. This paper has argued that to do so requires recognizing the democratic deficits in the policy-making process that impact on quality in the special needs and inclusive education field. It uses this analysis to conclude without grappling with these general policy issues we cannot expect some of the important questions in the SEN and inclusive education field to be addressed more coherently and more convincingly either conceptually or practically.

The idea of an EFC is based on seeking a medium term and working resolution of the political value tensions that underlie educational policy decisions. The deployment of deliberative democratic approaches is proposed as a way of dealing with some of the issues experienced in contemporary democratic processes. This is not some “third way” approach with false promises of what can be achieved, as it assumes that ideological differences and tensions will remain but may be moderated through common ground seeking strategies. Examples of such strategies that test, renew, and build on what there is in common have been discussed. For instance, a CA has been tried in the area of the longer-term funding of social care by two House of Commons Select Committees, but not for the development of a broad policy framework. Though this analysis and proposal arise in the English-UK system, the ideas drawn on are of international origin and the significance of the proposal can be applied and adapted to other countries and their educational policy making. The principles and approaches discussed here have wider applicability beyond education policy, but education is a good place to start given the public educational purpose inherent in a Commission. Here is a proposal that could renew ideas and values about the nature of schooling that takes genuine account of SEN and disabilities.

Statements

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1.^INVOLVE https://www.involve.org.uk

2.^More in Common https://www.moreincommon.com

3.^Citizen Shift www.Newcitizenship.Org.Uk

References

1

Advisory Committee for Mathematics Education (ACME) (2014). A Blueprint for Maths Education. Available online at: http://acme-uk.org/media/18410/issue_1_blueprint_final_version_10june.pdf (accessed February 14, 2019).

2

AEI/Brookings (2015). Opportunity, Responsibility and Security: a Consensus Plan for Reducing Poverty and Restoring the American Dream. Washington, DC: AEI/Brookings Working Group on Poverty and Opportunity. Brooking Institution.

3

BellD. (2015). Political Interference Is Damaging Schools, Speech to the Association of Science Education's Annual Conference. Available online at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-30711726 (accessed February 14, 2019).

4

BerlinI. (1990). The Crooked Timber of Humanity. London: Fontana Press.

5

BlackA. (2018). Future secondary schools for diversity: where are we now and were could we be?Rev. Educ. 7, 36–87. 10.1002/rev3.3124

6

BlackA.BessudnovA.LiuY.NorwichB. (2019). Academisation of schools in England and placements of pupils with special educational needs: an analysis of trends, 2011-2017. Front. Educ. 10.3389/feduc.2019.00003. [Epub ahead of print].

7

BoothT.AinscowM. (2011). Index for Inclusion; Developing Learning and Participation in Schools, 3rd Edn. Bristol: CSIE.

8

Cambridge Primary Review (2009). Cambridge Primary Review Report. Available online at: https://www.robinalexander.org.uk/cambridge-primary-review/#!prettyPhoto (accessed February 14, 2019).

9

CigmanR. (2007). A question of universality: inclusive education and the principle of respect. J. Phil. Educ.40, 775–793. 10.1111/j.1467-9752.2007.00577.x

10

CrouchC. (2000). Coping With Post-Democracy. London: Fabian Society.

11

CrouchC. (2011). The Strange Non-death of Neo-liberalism. London: John Wiley and Sons.

12

CrouchC. (2012). There is an Alternative to Neoliberalism That Still Understands the Markets. Guardian June 12. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2012/jun/27/alternative-neoliberalism-still-understands-markets (accessed February 14, 2019).

13

DahlR. A. (1982). Dilemmas in Pluralist Democracy: Autonomy and Control. Newhaven, CT: Yale University Press.

14

Department for Education (DfE) (2018). Special Educational Needs in England: January 2018. London: DfE. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/special-educational-needs-in-england-january-2018 (accessed February 14, 2019).

15

Department for Education (DfE) (2014). The National Curriculum for England to be Taught in All Local-Authority-Maintained Schools. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/national-curriculum (accessed February 14, 2019).

16

Department for Education (DfE) (2015). Special Educational Needs and Disability Code of Practice: 0 to 25 Years. London: DfE.

17

Department for Education (DfE) (2011). Support and Aspiration: A New Approach to Special Educational Needs and Disability. London: DfE.

18

DouglasG.Easterlow,G WareJ.HeaveyA. (2017). A Worthwhile Investment? Assessing and Valuing Educational Outcomes for Children and Young People With SEND. SEN Policy Research Forum. Available online at: https://blogs.exeter.ac.uk/sen-policyforum/past-policy-papers/ (accessed February 14, 2019).

19

FairbairnW. R. D. (1994). From Instinct to Self: Selected Papers, Vol. I and II, eds ScharffD.Fairbairn BirtiesE. . Northvale, NJ: Aronson.

20

FishkinJ. (2018). Random assemblies for lawmaking? Prospects and limits. Polit. Soc.46, 359–379. 10.1177/0032329218789889

21

GastonS. (2018). Insights From Focus Groups Conducted in England for the Project, At Home in One's Past. London: Demos.

22

Guardian (2012). Michael Gove's Own Experts Revolt Over 'Punitive' Model for Curriculum. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2012/jun/17/michael-gove-national-curriculum (accessed February 14, 2019).

23

GullifordR. (ed). (1971). Special Educational Needs.London: Routledge, Kegan and Paul.

24

HabermasJ. (1996). Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy. Transl. by W. Rehg. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

25

HaidtJ. (2012). The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. New York, NY: Pantheon.

26

HornbyG. (2015). Inclusive special education: development of a new theory for the education of children with special educational needs and disabilities. Br. J. of Spec. Educ. 42, 234–256. 10.1111/1467-8578.12101

27

INVOLVE and House of Commons (2018). Citizens' Assembly on Social Care: Recommendations for Funding Adult Social Care. London: Involve UK.

28

IPPR (2018). The Final Report of the IPPR Commission on Economic Justice. London: IPPR

29

MinowM. (1990). Making All the Difference, Inclusion, Exclusion, and American Law. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

30

National Archives (2019). Education Act 1981. Available online at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1981/60/enacted (accessed June 14, 2019).

31

New Citizenship (2014). This Is the #Citizenshift: A Guide to Understanding and Embracing The Emerging Era of the Citizen. Available online at: Www.Newcitizenship.Org.Uk (accessed February 14, 2019).

32

NorwichB. (1996). Special needs education or education for all: connective specialisation and ideological impurity. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 23, 100–104. 10.1111/j.1467-8578.1996.tb00957.x

33

NorwichB. (2008). Dilemmas of Difference, Inclusion an Disability: International Perspectives and Future Directions. London: Routledge.

34

NorwichB. (2014). Addressing Tensions and Dilemmas in Inclusive Education. Living With Uncertainty. London: Routledge

35

OECD (2018). Schooling for Tomorrow - The Starterpack: Futures Thinking in Action. Available online at: http://www.oecd.org/education/school/schoolingfortomorrow-thestarterpackfuturesthinkinginaction.htm (accessed February 14, 2019).

36

SchumpeterJ. A. (1942). Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

37

SEN Policy Research Forum (2012). The Coalition Government's SEN Policy: Aspirations and Challenge? Available online at: http://blogs.exeter.ac.uk/sen-policyforum/files/2016/08/29.Aspiration-policy-paper-Dec-12.pdf (accessed February 14, 2019).

38

SEN Policy Research Forum (2016). An Early Review of the New SEN/Disability Policy and Legislation: Where Are We Now? ed B. Lamb, K. Browning, A. Imich, and C. Harrison. Available online at: http://blogs.exeter.ac.uk/sen-policyforum/files/2017/05/Early-review-final-vers-4-paper-May-17.pdf (accessed February 14, 2019).

39

SenA. (2009). A Theory of Justice. London: Allen Lane and Harvard University Press.

40

Social Metrics Commission (SMC) (2018). A New Measure of Poverty for the UK. London: Social Metrics Commission.

41

UCL Constitution Unit (2017). Citizen Assembly and Brexit; Summary Report. Available online at: http://citizensassembly.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/CAB-summary-report.pdf (accessed February 14, 2019).

42

Van der MeerT. W. G. (2017). Political trust and the crisis of democracy. Polit. Behav.1–22. 10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.77

43

Warnock Report (1978). Special Educational Needs. Report of the Committee of Enquiry into the Education of Handicapped Children and Young People. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

44

WarnockM. (1991). House of Lords Debate on Special Educational Needs, Vol. 532. London: Hansard. 971.

45

YoungM. (1995). A curriculum for the 21st century?: towards a new basis for overcoming the academic/vocational divisions, in Redefining the Future: Perspectives on Students With Learning Difficulties and Disabilities in Further Education, eds MaudsleyE.DeeL. (London: Institute of Education, University of London), 52–68.

Summary

Keywords

special educational needs (SEN), inclusive education/schools, value dilemmas, deliberative democracy, education policy

Citation

Norwich B (2019) From the Warnock Report (1978) to an Education Framework Commission: A Novel Contemporary Approach to Educational Policy Making for Pupils With Special Educational Needs/Disabilities. Front. Educ. 4:72. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00072

Received

21 February 2019

Accepted

04 July 2019

Published

17 July 2019

Volume

4 - 2019

Edited by

Geoff Anthony Lindsay, University of Warwick, United Kingdom

Reviewed by

Anthea Gulliford, University of Nottingham, United Kingdom; Fraser Lauchlan, University of Strathclyde, United Kingdom

Updates

Copyright

© 2019 Norwich.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Brahm Norwich b.norwich@exeter.ac.uk

This article was submitted to Special Educational Needs, a section of the journal Frontiers in Education

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.