- School of Education, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, United Kingdom

This paper draws on a Scottish longitudinal study. It focuses on the variability of a sample of focal children's wellbeing and attainment trajectories on the journey through education from the age of 3 to school leaving at 16–18 years old in one Scottish Council area, in order to respond to the question What aspects of the intersection of wellbeing, attainment, and school transitions help to explain school leaving outcomes? The relationships between wellbeing and attainment either side of primary and secondary school start are explored and the ways these may link to transition experiences and educational outcomes at school leaving are raised. A new interpretation of Bronfenbrenner's “mature” bioecological system model which considers person, processes and educational contexts over time frames the methodology, methods and findings of a data rich exploratory-interpretive longitudinal study and discusses their relationship to current dilemmas surrounding educational outcomes in Scotland at the present time. The role of wellbeing and attainment measures as proxies for school success is considered and found to be too narrow a concept in the form experienced by the focal group of study participants. While wellbeing needs to be much more clearly defined and fostered, concepts of attainment predicated only on maths and literacy (and on some measures, science) are found to be insufficient in that they may discriminate against too many. Attention to the opportunities offered and risks inherent in periods of educational transition allow identification of, and reflection upon the qualities of a good educational transition from both early childhood education to school start, and subsequently in the move to secondary education. It is found that a “good transition” though it exists, is not available to all children: consequently more equitable approaches are advocated, and alternatives for practical and policy action are proposed. Study of educational transitions dates back fifty years: is it not time for systems themselves to change?

Introduction

Transitions occur throughout life, individually, in the family, in society, and as we journey from early childhood, through early education, primary, and secondary schooling and on into adult life. The value of early childhood experience, and of early education, is increasingly understood as a “good”, but a gap exists in understanding how benefits may be sustained by transitions processes as children move from early childhood to primary schooling and later from primary to secondary education. Few studies have focused specifically on possible relationships between transitions experiences and school outcomes with a single cohort of participants over time. An argument is developed for the potential relationship between a good transition and later school success as understood through the dual lens of wellbeing and attainment over time.

Numbers of early longitudinal studies discuss the impact that school entry may have upon later school performance (e.g., Pollard and Filer, 1999; Entwisle et al., 2005): suggesting that the nature of early transitions may influence longer-term outcomes. To understand the impact of early experience on later outcomes we need to know those outcomes: consequently numeracy and literacy are frequently used as proxies for attainment and what is often referred to as “school success”. Others emphasise the importance of wellbeing and belonging as influential.

A consideration of child wellbeing raises a number of principles for transition. Lippman et al. (2009) suggest the importance of examining positive wellbeing and argue for the development of constructs for positive wellbeing for both children and youth, rather than presenting problem behaviours and situations. A focus on positive wellbeing means acknowledging strengths, rather than focusing on difficulties. Thriving, notwithstanding social or family circumstances, means focusing on human and social capital. Similarly Ungar et al. (2019) in making a positive case for fostering resilience as part of wellbeing, also focus on strengths. They emphasise positive wellbeing, finding common ground in measures and embracing self-report. Mashford-Scott et al. (2012) acknowledge the importance of children's wellbeing in relation to learning and development and the need to know how children experience wellbeing: they also argue the importance of the voice of the child accessed through self-report. Lippman et al. (2009) find a fragmentation and overlap of constructs in wellbeing measures and a need for reliability and validity for diverse groups. They find Bronfenbrenner's ecological approach “a useful time-space structure for integrating the several theories and concepts that explain positive child development” (p. 9): a hybridisation of the “mature” version of Bronfenbrenner's ecological approach supports the conceptual framing, design and analysis of the current study (Dunlop, 2021, forthcoming).

Lester and Cross (2015) established strong school climate predictors and factors protective of emotional and mental wellbeing, through multi-level modelling of data generated in their repeated self-completion questionnaire with 1,800 11–14 year olds. Peer support in the last year of primary school was predictive of wellbeing, feeling safe in the first year of secondary school was protective of wellbeing, and in the following year for mental wellbeing. Feeling connected to school, support from peers and feeling safe in school protected emotional wellbeing. Further the role of school belonging links to wellbeing and learning processes (Allen et al., 2018). Self-esteem has long been understood as a precursor to subjective wellbeing (Du et al., 2017), however Miller and Parker (2006) had found evidence of discrepancies between teacher assessment of children's self-esteem and children's own views. For wellbeing it matters for children to “have a say” (Graham and Fitzgerald, 2011) about all that affects them, given there are doubts about teachers' capacity to judge subjective wellbeing (Urhahne and Zhu, 2015). These ideas clarify roles for education in fostering wellbeing as an outcome of education (Spratt, 2016) and in the present study influenced the choice of research materials appropriate firstly to young children and subsequently to ensure the voice of young people in transition to secondary is heard through self-report.

Laevers' work shows a child's sense of emotional wellbeing and levels of involvement as linked aspects in engagement in early childhood experiences. He argues that these elements initiate effective interactions with others: he proposes 10 action points, one of which is “the way in which the adult supports the ongoing activities with stimulating interventions (Action Point 5)” (Laevers, 2000, p. 26). In later work the ways in which adults interact with children assumed greater emphasis (Laevers, 2015). Frydenberg and Lewis' (1993, 2000) work links the concept of coping with change to resilience, finding gendered differences in coping, and focusing (Frydenberg, 2017) on the ways in which coping as a process, in a range of situations, offers up an outcome of resilience. This leads to identifying the need to look at agency in transitions, understanding resilience as a process, building understanding of resilience in family, school and community, raising individual awareness of wellbeing and linking these concepts to social capital and vulnerability at times of transition.

Attainment is commonly used to describe end-point outcomes, whereas achievement is more to do with how well you have done in relation to previous personal attainment or personal effort. Attainment is understood to be cumulative (Magnuson et al., 2016) involving both academic and social skills and implicating engagement in the educational process. Most studies focus on middle childhood onwards, and either exclusively on the earliest years (McDermott et al., 2013) or not focusing on the earliest years at all, despite some earlier evidence of links between the nature of school entry, the thorny issue of school readiness and later achievement (Duncan et al., 2007). The effects of secondary school experience on academic outcomes are better documented, and numbers of researchers have found relationships between attainment and secondary school transitions (Langenkamp, 2011; Langenkamp and Carbonaro, 2018) including disruption of social ties (Grigg, 2012) and lack of engagement (Gasper et al., 2012). McLeod et al. (2018) focused on ECE attendance and the relationship with longer term outcomes and Taggart et al. (2015) linked the quality of preschool education and the home learning environment to outcomes throughout education until 16+. These studies reinforce the approaches used in the present study which led, e.g., to considering “transitions readiness” rather than school readiness, as well as focusing upon parental engagement and participation, children's social worlds at times of transition and their home learning environments (Dunlop, 2020a).

Others claim “a robust body of evidence suggesting that children's early educational experiences can have cascading effects on school and later life outcomes” (Little et al., 2016, p. 1). Such claims emphasise the potential importance of the first educational transitions and the need for clarification about what is understood by “transition”. Here both Bronfenbrenner's (2005, p.53) statement that the “developmental importance of ecological transitions derives from the fact that they almost invariably involve a change in role” (Bronfenbrenner, 2005, p.53), and Cowan's “We view transitions as occurring when there are qualitative shifts in the individual's self-concept and world view, major life roles, and central relationships.” (Cowan, 1991) link to the focus on changes in role, status and identity in the present study. Sameroff's model of development (Sameroff, 2009) captures the mutual and transactional influence of child and environment. Times of transition expose children and those who engage with them in new developmental trajectories, as his work illustrates. Bronfenbrenner, in later iterations of his model addresses both contextualism and relational development (Tudge et al., 2016).

Further a review of three decades of transitions research found that early intervention may fade out without successful transitions (Kagan and Neuman, 1998) but there are few attempts to study the impact of transitions' claims over a pupil career with a single cohort of students, rather than extracting such data from large cohort studies. Primary-secondary transition studies have generated some evidence about transition to secondary which links to later wellbeing and attainment (Riglin et al., 2013). The coincidence of secondary transition with early adolescence, and linked risk and protective factors are also well-documented (Evans et al., 2018; Jindal-Snape et al., 2019), factors such as identity, sense of self as a learner, coper and friend became central to the primary-secondary phase of this study.

Turning to the Scottish context, education policy is determined as a devolved matter. There are features of Scottish policy that influence transitions, attainment, and wellbeing during the journey through education from 3 to 18. Scottish policy has for some time focused on improving the wellbeing and life course trajectories of children and young people (Scottish Government, 2018a). On the “Getting it right for every child” model, embedded in Scottish policy and practice and later formalised through The Children and Young People Act (Scotland) (2014), wellbeing is defined through eight indicators which embrace different facets of a child's life: children should be supported to be safe, healthy, active, nurtured, achieving, respected, responsible, and included.

Commissioned research into the resilience of pupils in transition to secondary school (Newman and Blackburn, 2002) and published self-evaluation guidance (HMIe, 2006) reinforced the importance of children's wellbeing at times of transition but emphasised the need for full attention to be given to learning, teaching, and curriculum issues. Recent Scottish Government publications illustrate a continuing focus on Scottish children's wellbeing (Scottish Government, 2018a) and attainment profiles (Scottish Government, 2018b). Closing the poverty related attainment gap has become a core aspiration of the Scottish Government today. In 2019 the principles of the curriculum were re-visited and a “curriculum refresh” was undertaken putting learners at the center of education and emphasising the original messages of Curriculum for Excellence while setting them in today's context through five key contributions: “understanding the learners,” “knowing the big ideas,” “being clear on practical approaches,” “using meaningful learning networks,” and “knowing your own learning and support needs” (The Scottish Government, 2019a). In the academic session 2019–2020 a new Health and Wellbeing Census (Scottish Government, 2020a) was due to be launched in Scotland before Covid-19 related school closures intervened. Among the aims of this census, which will now be introduced when the timing is right, is “to develop better understanding on some of the factors which influence pupil attainment and achievement.”

The Scottish Attainment Challenge intends to improve the lives of young people as they go through their school education. A priority is “Building leadership capacity within schools in order to improve the learner journey, particularly at key transitions stages such as the transition from primary to secondary education” (Scottish Government, 2018c, p. 8). The National Improvement Framework and Improvement Plan (Scottish Government, 2018c) has included a focus on transitions which aims to develop specialisms in transitions between primary and secondary school, support families, improve curriculum collaboration between sectors of education and incorporate the results of a commissioned literature review of primary-secondary transitions (Jindal-Snape et al., 2019) into the National Improvement Framework. Most recently new practice guidance for the early years in Scotland emphasises once again the importance of transitions in the early years, calling for greater consistency in practice to ensure continuity through the transition to school (Scottish Government, 2020b). This guidance includes a strong section on why transitions matter, providing helpful support especially now as countries begin to emerge from the 2020 and 2021 Covid-19 pandemic lockdowns to bring children back into early years and school settings.

Social disadvantage continues to compromise school attainment and wellbeing, and child poverty has increased—currently in Scotland a quarter (24%) of all children now live in relative poverty (after housing costs) (The Scottish Government, 2019b), and is predicted to rise substantially by 2020–2021 (Congreve and McCormick, 2018). Pertinent in the Scottish context of a 3–18 curriculum, there remains a need to know whether curriculum reform has achieved an aspired-for continuum of learning and development in practice, and to ensure that present policy and curriculum frameworks provide a coherent approach to wellbeing and attainment from early childhood into school and from primary to secondary education to the benefit of children and young people.

Whether navigating a first transition successfully helps children and young people to cope well with later transitions remains largely unexplored. Ideas of “positive” or “successful” transition remain contested and there is a lack of evidence of the influence of a “good” transition, if it exists, upon subsequent transitions and later school outcomes and coping strategies. To understand the role that transitions may play in securing or undermining lasting benefits, it is necessary to study transitions over time with the same cohort of children.

The study aimed to identify factors that may serve to explain, relationally rather than causally, what makes for a good first transition to school by studying children's learning and development in the everyday contexts of early childhood and primary school and linked on a systems approach to home experiences and self and other perceptions of children and young people as learners, copers and friends at two periods of major educational transition. Therefore, the driving question for the informing longitudinal study (Dunlop, 2020a) was “What explanatory factors link individual experiences of school transitions and later outcomes?”

Reflections on the literature lead to six sub questions (SQ) as follows:

S.Q.1. What is the role of personal attributes, wellbeing and attainment, perceptions of self in educational transitions?

S.Q.2. What kinds of educational and wellbeing trajectories can be identified for the focal children over time?

S.Q.3. What is the day-to-day experience of children in education environments either side of the two major transitions?

S.Q.4. What are the perspectives of different stakeholders during transitions?

S.Q.5. How do attainment and wellbeing trajectories relate to each other at the two major transitions?

S.Q.6. In what ways does the nature of each child's transition experience relate to their educational outcomes at school leaving?

Notwithstanding the broader focus indicated in these main study questions, this particular research paper presents wellbeing, attainment, and case study data from a longitudinal study of one cohort's journey through school from the age of three until school leaving between 16–18 years old, in order to focus on “What aspects of the intersection of wellbeing, attainment, and school transitions help to explain school leaving outcomes?”

Materials and Methods

A Longitudinal Study of Educational Transitions

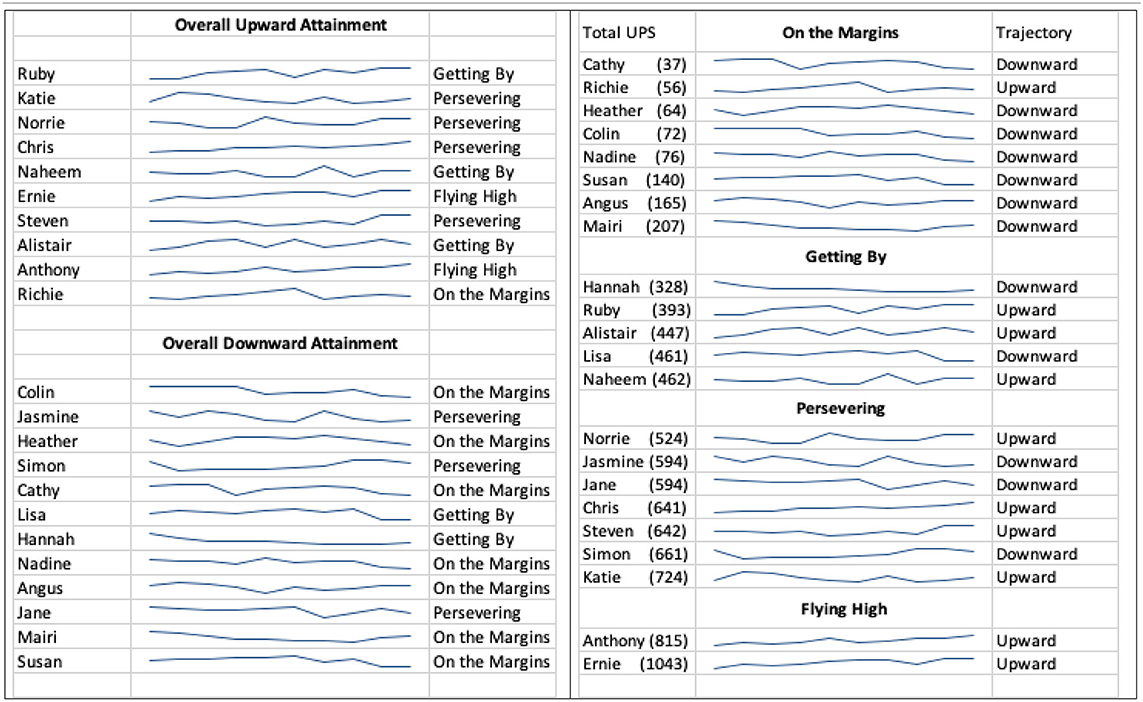

The 22 focal children at the heart of this study of educational transitions each had quite different educational attainments as they left school education. This section will present their wellbeing and attainment storey, over their school career, from their pre-school year until school leaving. Four groups emerge: those on the margins, those who get by, those who persevere against the odds, and those who fly high.

The intention of presenting these wellbeing and attainment journeys is to know what the group of focal children in this study had achieved in their journey through education, how they fared in relation to their peers and to then be able to unravel the reasons for their varied wellbeing and attainment in relation to the two main transitions in education and school outcomes through the use of four illustrative case studies.

Framing the Study Design

In any study the researcher's ontological and epistemological perspectives determine the approach taken to the procedures and logic they should follow (Waring, 2017). My own position is one of recognising the creativity and competence of children and the complexities they are faced with as they journey through education. A theoretical framework, based on a hybridised socio-bio-ecological model (Dunlop, 2020a) informed the framing of the Navigating Educational Transitions study, data collection and anaylsis. This innovative framework was based on the interaction of person, process and context over time and allowed comparison of the two macrosystems of early childhood transitions and primary-secondary transitions, a reflection of Bronfenbrenner's original proposition 1 (Bronfenbrenner, 1989, [p. 231]). Wellbeing and attainment were identified as significant developmental outcomes: understanding of these two developmental processes was developed in context with an eye to relationships, individual attributes and participation in the educational experiences available.

Following published criteria for the inclusion of studies claiming to be informed by Bronfenbrenner's work (Tudge et al., 2009), the research design was based on what they call “the mature” version of Bronfenbrenner's theory (p. 202) and as explained includes each element of his Person-Process-Context -Time (PPCT) model.

Study Design

Applying this framework to study design, data sources therefore aimed to provide insight into individual attributes; educational experiences at home and school; the perspectives of family, teachers and the children themselves, and to focus on the two identified developmental outcomes: wellbeing and attainment. Observation, video recordings, classroom discourse, child group conversations, stakeholder perspectives through questionnaire and interview, environmental ratings, video tours, self-report, wellbeing and coping ratings, assessment and attainment protocols and case study were each included. In the PPCT framework each data source was designed to draw out data either side of the two major educational transitions: from early years settings into school and between primary and secondary education.

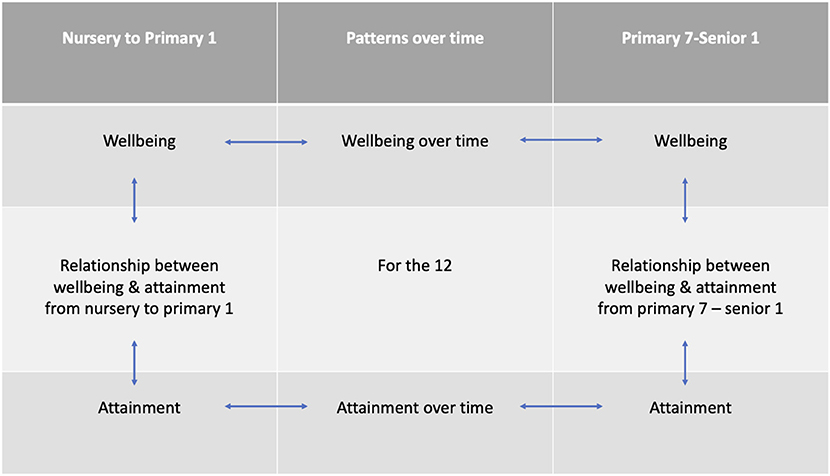

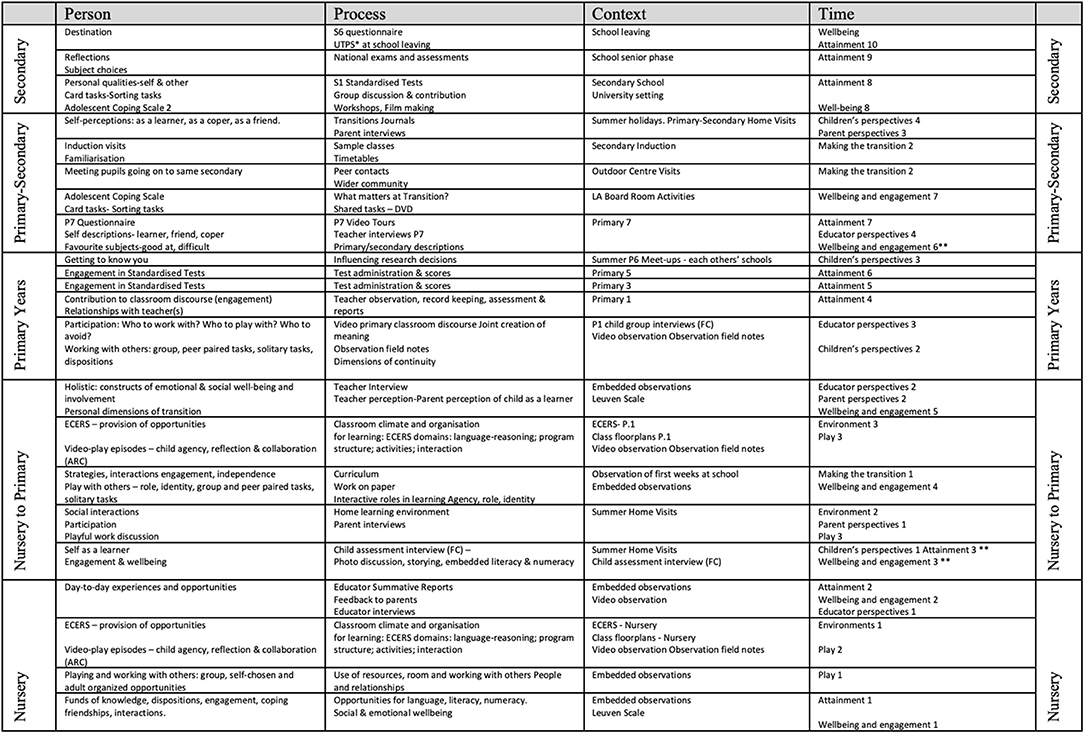

The whole study design evolved over time: primarily qualitative, some decisions were made to gather quantitative data. The data collected over the lifetime of the study is tabulated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Person-Process-Context-Time Model of Data Collected. *UTPS, Universal Tariff Points Score; ECERS, Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale; *Timepoints not included in trajectories.

Data was gathered over two periods of 3 years in the contexts of nursery, home, schools, local authority, and university venues. Selected data from the study allowed the development of both wellbeing and attainment trajectories over time for a focal group of children: these are used to answer the question posed in this paper on the intersection of wellbeing, attainment and school transitions and the way they may help to explain school leaving outcomes. Wellbeing data was gathered over both transition phases until early secondary school, the home wellbeing data is not included in the school based trajectories. Attainment data was gathered over the full period of the study from school year 1996–1997 to the school year 2009–2010. The years of my retirement from full-time work have afforded the opportunity to work with the volume of data generated in comprehensive way, and importantly to link this to the present time. A multi-layered and mixed method approach (Lincoln, 2010) was taken to gathering data over time in pedagogically relevant ways in which researcher presence respects the complexity of educational contexts and the learning, teaching, interactions and relationships within them (Nind et al., 2016; Blaisdell et al., 2019) so that research approaches and pedagogy are closely aligned.

Participants

Four primary schools in four different areas representative of the local authority demographic were selected by the local authority for inclusion in a study which originally set out to understand continuity and discontinuity in the transition from early childhood settings to primary school, and would later consider the transition to secondary education for the last year of primary education and the first 2 years of secondary school. In the overall study the same six class cohort (n = 150) was followed through two major educational transitions from the age of three to secondary school leaving. The experiences of the cohort as a whole form a backdrop for the more intensive study of the focal children.

In the January parents enrolled 150 children in the four selected primary schools to start school in August of the same year. Enrolment details for each child normally included gender, date of birth, home address, resident parents and siblings, parental employment, first language and ethnicity. Using these data, stratified purposive sampling identified one fifth of the children (n = 30) as a focal group who would be studied more intensively. This group reflected the profile of the 150 children as a whole in that 10% lived with a single parent, 10% of families were unemployed, 10% were from an ethnic minority, there were an almost equal number of boys and girls with fewer of the children in the older 6 months (n = 68) on entry to school and more who had not turned five upon school entry, in the younger 6 months (n = 82). Almost one third of the children (n = 45) were in the youngest 3 months of eligibility and therefore started school before they were 5 years old.

Of the 30 originally identified focal children, two with additional support needs were excluded from the study by the host authority and one requested a different school placement. Of the 27 children at the outset of the study, the family of one child relocated to another part of the country, while four moved to out of area schools within 3 years of school start: leaving a total of 22 participating focal children over time.

A particular focus is given to ethics of longitudinal research. Two types of consent were sought—parental consent on an opt-out basis to observe and record the early learning and school experiences of the 150 children in their nursery settings for 6 months prior to school start and for the first year of their primary education, and parental consent on an opt-in basis for the sample of focal children. The final study report (Dunlop, 2020a) focuses on experiences of the 150, bringing further detail from the focal group of 22 individuals. In any study of day-to day experience the reciprocal relationship between research and practice needs to be addressed: ethical considerations are relevant throughout the research process and issues may change over time in long-longitudinal work.

Ethical approval was therefore sought and received at four different time points for this study. Firstly at the outset of the study through parental consent and with child assent (Dockett et al., 2013; Phelan and Kinsella, 2013) for home-based assessments and for observation and discussion in the first 2 years of school. Secondly when the children were in their last year at Primary School, through class-based discussion before questionnaire completion, and in small groups of the focal children in each class where rights, risks and benefits of taking part in longitudinal research were debated. A home visit was arranged to create an opportunity to discuss the study further, to understand the data already collected in earlier years and to ensure individuals and their families had all the information needed in order to make an informed decision to continue in the study, to allow continuing use of data already collected or to withdraw.

Thereafter all 22 participants and their families gave continuing permission for their data to be used in the study. One participant decided in P7 to discontinue active participation in the study and the parents of another preferred their child to avoid involvement outside of school. Twenty focal children therefore remained active during the transition to S1 of whom 12 continued their active participation for the first 3 years of secondary education. Researcher engagement continued with the host local authority leading to application for ethical approval for the Transitions Continuation Study for S4 and S5 and finally for the Transitions Sixth Year follow up. In each iteration of ethical approval consent to academic publication, while protecting participants' identity, was included. A further follow-up study is under consideration at the present time, with the aim of gaining insight into the cohort's young adult lives.

Materials

Wellbeing and Coping and Engagement Over Time

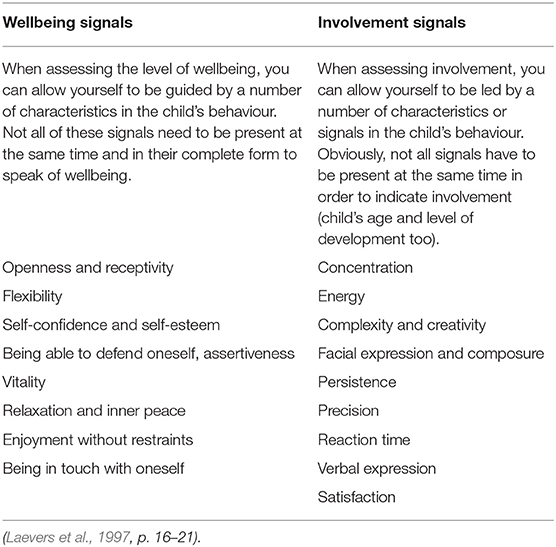

The tools used were the Leuven Involvement Scale for Young Children (LIS-YC) (Laevers, 1994) and The Adolescent Coping Scale (Frydenberg and Lewis, 1993): both carry their own protocols for completion and analysis. Wellbeing and involvement measures gathered at four early years timepoints (Nursery, P1 Christmas, P1 Summer and P2) were standardised across the 22 focal children to provide each with an individual standardised score to produce trajectories of wellbeing over the nursery-primary transition. At the primary-secondary transition wellbeing and coping materialised as an issue and led to a search for a structured means of investigating this. The Leuven scale uses Leavers' wellbeing and involvement observational methods (Table 1) which were easily integrated into the overall observational approach. The intention in using both wellbeing and involvement measures was to establish an understanding of wellbeing in the nursery and school classrooms and to gauge the levels of involvement (engagement) of children in areas of the curriculum in nursery and early primary.

Two raters coded a sample of material following the Child Monitoring System protocols. Both raters had attended a 3 days intensive training programme in which practical workshops watching and coding video episodes had been a feature. Their intra-rater consistency was well-established with this system. Following the inter-rater exercise wellbeing and involvement observations were rated on the same model for each of the Focal Children in both nursery and primary.

The Frydenberg and Lewis Adolescent Coping Scale (ACS) self-report approach provided a means to consider wellbeing at the primary-secondary transition. They find the concept of coping with change is linked to resilience. The Short Form of the Frydenberg and Lewis (1993) Adolescent Coping Scale (ACS) was used as the best known protocol available at the time to judge student coping as the focal group transitioned to secondary school. Coping was understood to be a useful proxy for wellbeing, it was then possible to compute Nursery to P7 wellbeing trajectories by using the two sets of standardise scores. Similarly for the 12 for whom full data is held wellbeing trajectories could be computed across both transitions, over seven timepoints.

The short version of the ACS has two forms for participants to complete—the general short form and the specific short form. In completion of the general form participants are asked to think of a situation which they find challenging and indicate how they would cope. They are offered 18 possible ways of responding and use a Likert Scale of five response options ranging from “not used” to “used a great deal.” In the specific form the strategies are considered in relation to the specific issue chosen: in this study the specific issue was transition to secondary school. Definition and examples of the conceptual areas of coping (Huxley et al., 2004) based on the Adolescent Coping Scale (Frydenberg and Lewis, 1993) use the following approaches: seek social support, focus on solving the problem, work hard and achieve, worry, invest in close friends, seek to belong, wishful thinking, not cope, tension reduction, social action, ignore the problem, self-blame, keep to self, seek spiritual support, focus on the positive, seek professional help, seek relaxing diversions, and physical recreation. The protocol clusters these ways of coping under the three over-arching categories of productive coping/problem solving, reference to others and non-productive coping. From their responses it is possible to establish what dimensions of coping young people use most frequently.

The responses the focal children gave before and after the Primary-Secondary transition allowed wellbeing trajectories to be plotted for the 12 who completed the scale twice, by computing individual standardised scores from Nursery to Senior Year 1 (S1). For the remaining ten focal children who completed in Primary School but not in Secondary, their individual standardised scores were added to their early years wellbeing profiles to give a Nursery-Primary Year 7 (P7) trajectory.

Attainment Over Time

Data on the focal children and young people's school attainment was gathered over a 12–14 years period, depending on individual dates of school leaving. Attainment data over the whole educational journey is available for all 22 focal children. The forms of data are varied and present a challenge to creating learning trajectories for the each pupil's school career. In summary the range includes observation, teacher report, pupil profiles based on observational data and teacher judgment, a specifically designed pre-school assessment generating numerical scores for each item, externally designed assessments standardised for the Local Authority, and the National Assessments and Examinations of the time. The timing of data gathered is visible in Figure 1 which shows the full data gathering process for the complete study.

Educational Journeys Over Time

In longitudinal study it is not uncommon to find case studies as the main focus in qualitative work (e.g., Pollard and Filer, 1999; Warin and Muldoon, 2009), and less frequently as illustrative examples in quantitative work/mixed-method design (Siraj-Blatchford, 2010): the case may be as large as a school or a sector of the education system, but may also be framed at an individual level.

Where the case is identified at an individual level, while it focuses on the individual child's experience, at home, in nursery and at school, such experience is rarely seen in isolation, given the person, process, context, and time (PPCT) factors at work. With a number of focal children in the same class, case studies can elaborate the researcher's understanding of the class as a whole.

Procedure

The procedures used to form wellbeing and attainment trajectories and to create the narrative case studies are addressed in this section.

Generating Wellbeing Trajectories

The data from six of the seven wellbeing time-points and at each of nine attainment time-points generated individual standardised scores for wellbeing and attainment. The same formula of subtracting the mean score (for all 22, 18, or 12 children according to data gathered) from the individual raw score, then calculating the standard deviation to generate an individual standardised score, was used for all wellbeing and attainment results. This allowed integration of the different forms of data. In these ways a range of trajectories were developed allowing the presentation of attainment and wellbeing over time, as well as creating the potential to explore individual and group patterns within and across the major transitions, as exemplified through four case studies in the presentation of results.

Generating Attainment Trajectories

By standardising scores from the variety of assessments, it is possible to combine these scores to generate a single scale which allows pupils' attainment over time to be understood continuously. Individual comparative performance across the two selected curricular (developmental) areas over time may also be understood. In this way it is also possible to plot group outcomes over time to see who is improving, declining, or maintaining performance relative to their starting points and to the group.

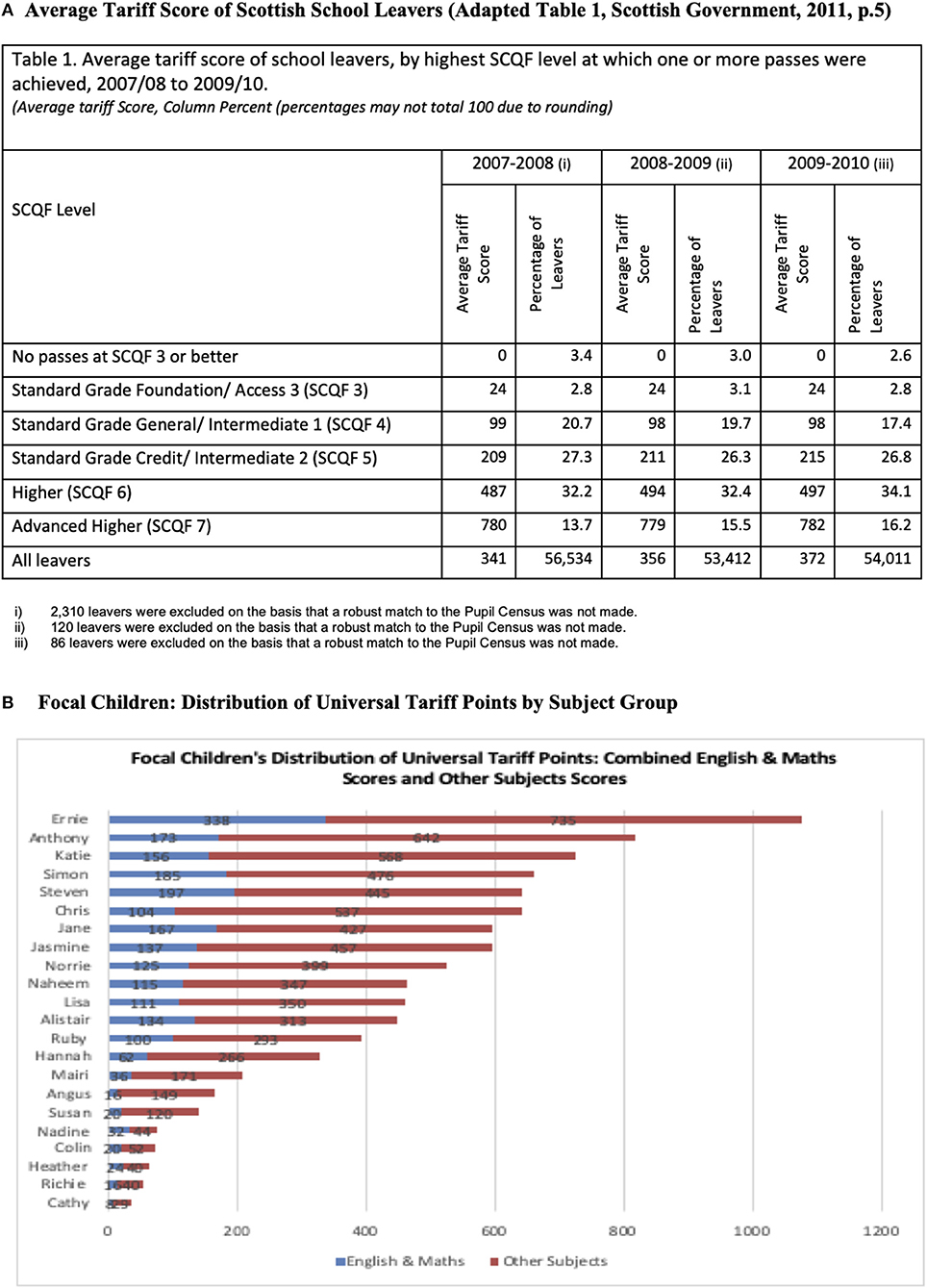

Ten time-points came into strong view the first four clustered around the transition to school: in the summer term of nursery education, at home over the holiday period before school start (not included in the trajectories presented here), at the end of the first term in school and at the end of the first year in school. The next time-points of summer of the second and third years in school, each drew on teacher report in Primary(P)2 and in P3 upon the standardised testing introduced by the Local Authority in P3. A lighter touch at P5 in that no other contributing data was gathered at this time-point, was followed by a second more intense focus on the children's experience during the P7 year before transition to secondary education in S1 the year following that change. A final time-point, which serves to understand the full educational journey from 3 to 18 (or 16 for some leavers), draws together national assessments and examination results in S4, S5, and S6: the Senior Phase of secondary education. Given that there are different grading systems for different types of assessment, it was decided at first to use the Universities and Colleges Admissions Service (UCAS) tariff points to convert the national Higher and Advanced Higher exam results from A, B, C... into numbers. There is no such tariff for the other results that represent pupils' highest level of achievement in years S4 and S5, e.g., Access 2 and 3 or Intermediate Certificates that had replaced Standard Grades and were the precursor of the current National 4 and 5 awards.

A different solution was sought, resulting in the use of The Unified Points Score Scale (UPS) which is an extended version of the UCAS Scottish Tariff points system (Scottish Government, 2009, 2011; The Scottish Government, 2010). The different forms of Literacy/English and Numeracy/Maths attainment data collected during this long-longitudinal study were used to develop standardised scores and to plot individual attainment trajectories over a school career. A final score looks across all subjects by standardising the points gained cumulatively from all other subjects taken by each individual from Access level through to Advanced Higher. Alongside these attainment data, a range of explanatory factors including environments, individual attributes and the children's sense of themselves as learners, copers and friends, were considered for all of the children (Dunlop, 2020a), and are exemplified through four case study examples.

Generating Nested Case Studies of Educational Journeys: Over Time

Both qualitative and quantitative data contributed to the case studies developed for the 22 focal children, in which the approach is akin to the Mosaic Approach (Clark, 2004), where a picture or pattern is built up through the adding of segments—the segments of the planned case studies at both nursery-primary and primary-secondary transition include environments, interactions, individual attributes, wellbeing, and attainment. Case study data was generated through observations and interviews, consideration of the quality of learning environments, attainment and wellbeing measures, self-report, parent, teacher, and individual perspectives and group activities. In the case studies presented these different elements are drawn upon.

Results

This section presents patterns across the wellbeing and attainment trajectories of the 22 focal children who attended early childhood, primary and secondary school in the particular Local Authority. How these journeys through education align or not at the two major transitions in education allows discussion of the intersection of wellbeing, attainment and transitions to emerge. By relating these experiences to attainment outcomes in core subjects at school leaving and then across all subjects studied, the question of the validity of using outcomes in Literacy/English and Numeracy/Maths as proxies for school success is opened up. A brief indication of the wider explanatory factors considered (Dunlop, 2021, forthcoming) is included. Finally four case studies are used to illustrate emerging patterns in individual educational journeys.

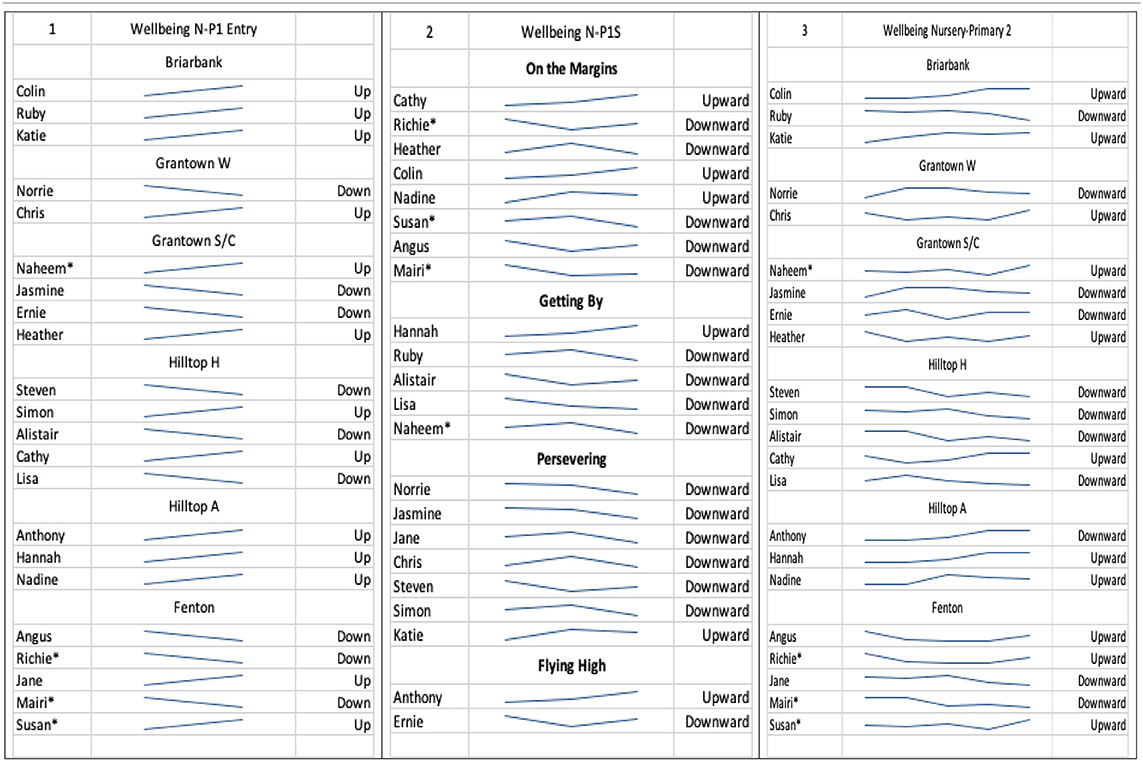

Wellbeing Trajectories Over Time

In this study children's wellbeing was explored through whole class screening to gauge the ambient atmosphere in nursery and early primary classes either side of the transition. Focused observations of the 22 focal children using the Laevers (1994) phenomenological approach to wellbeing and involvement in nursery and primary1 (Table 1) generated wellbeing scores either side of transition to school (n = 22). Sparklines Table 2.1 shows that for 13 children their overall wellbeing as observed in nursery and the first term in school had an upward trajectory on entry to school, for the remaining nine wellbeing dropped in the early months of school. For six children this upward wellbeing profile continued through to the end of their first year in school, but for 16 children their overall wellbeing dropped between their last nursery term and their last P1 term (Table 2.2). This downward trend occurred for all children attending three (Grantown W, Grantown S/C, and Fenton) out of the six P1 classes, in one class the three focal children all sustained an upwards trajectory and in the other two there was a mix of a fall and a rise in wellbeing among the different children. The extent to which these trends link to individual attributes and experiences, or seem to be explained more generally for groups of children, emerges when the nature of classroom interactions, dominant pedagogy, classroom environments, and teacher wellbeing is considered.

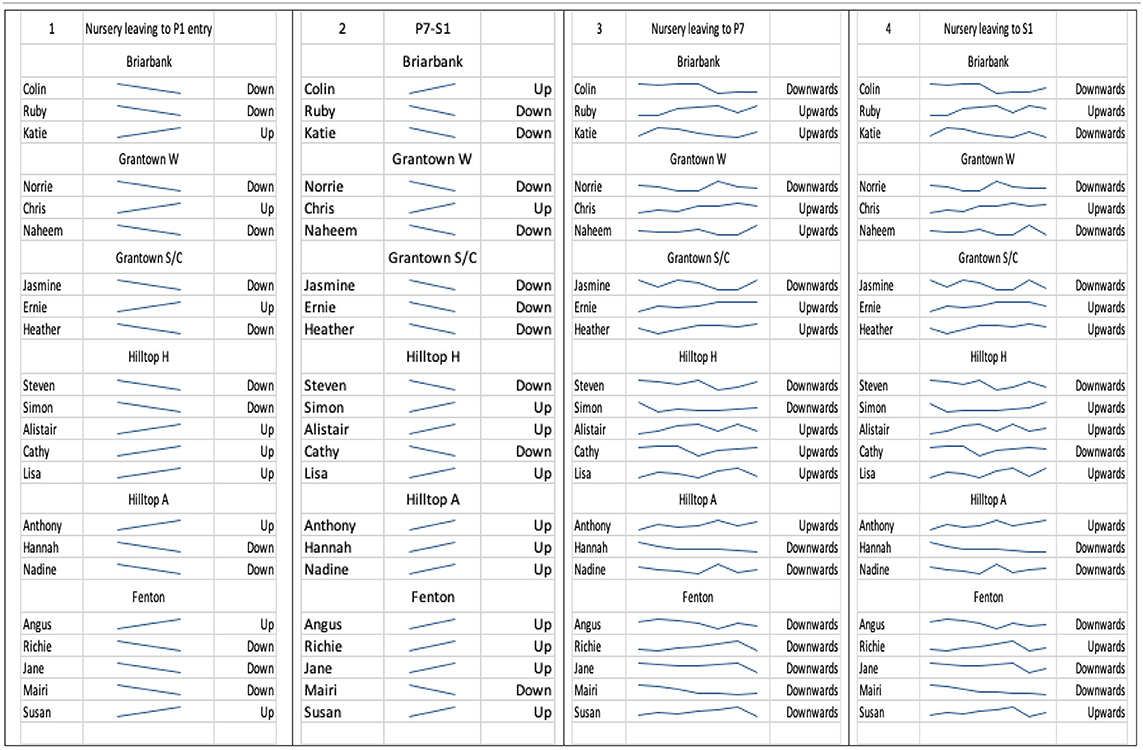

Table 2. Sparkline wellbeing trajectories: Nursery-P1 entry; Nursery to P1-summer by later attainment groups; Nursery -P2 summer.

The desire to know how long it took any particular child to feel well in school meant a further set of observations were undertaken in the last term of the first year in school, Table 2.2 applies the later attainment groupings to illustrate the relationship between early wellbeing and later school outcomes. Taking account of teacher assessments of personal, social and emotional development, wellbeing scores were also generated for P2, allowing a picture to emerge of how long any particular child may take to adjust and feel content in school. When children moved on to P2 their wellbeing profiles change again, and the group is evenly split (Table 2.3) with 11 children now experiencing an upward trajectory and 11 a downwards one.

For the second major transition, from the end of primary school through to the first year in secondary education, a self-report protocol was used. By P7 when 18 children took part in the first round of the ACS self-report, again the focal group was equally divided between upward and downward wellbeing as shown by class attended in Table 3.1.

Table 3. (1) Wellbeing across time nursery to P7 (n = 18); (2) Wellbeing nursery to S1 (n = 12); (3) Available wellbeing over time (n = 22).

For the second round of ACS in their first year of school 12 participating children (Table 3.2) completed the self-report. Six reported positively about the transition to secondary, while six felt their wellbeing and capacity to cope was on a downward trend. Table 3.3 illustrates the available wellbeing data for all focal children. Ten trajectories are downward in nature, but looking at this overall data 12 sustained upwards trajectories in the longer term.

How these data align with attainment data over time is addressed in the section “Reflections on the Results Presented”.

Attainment Trajectories Over Time

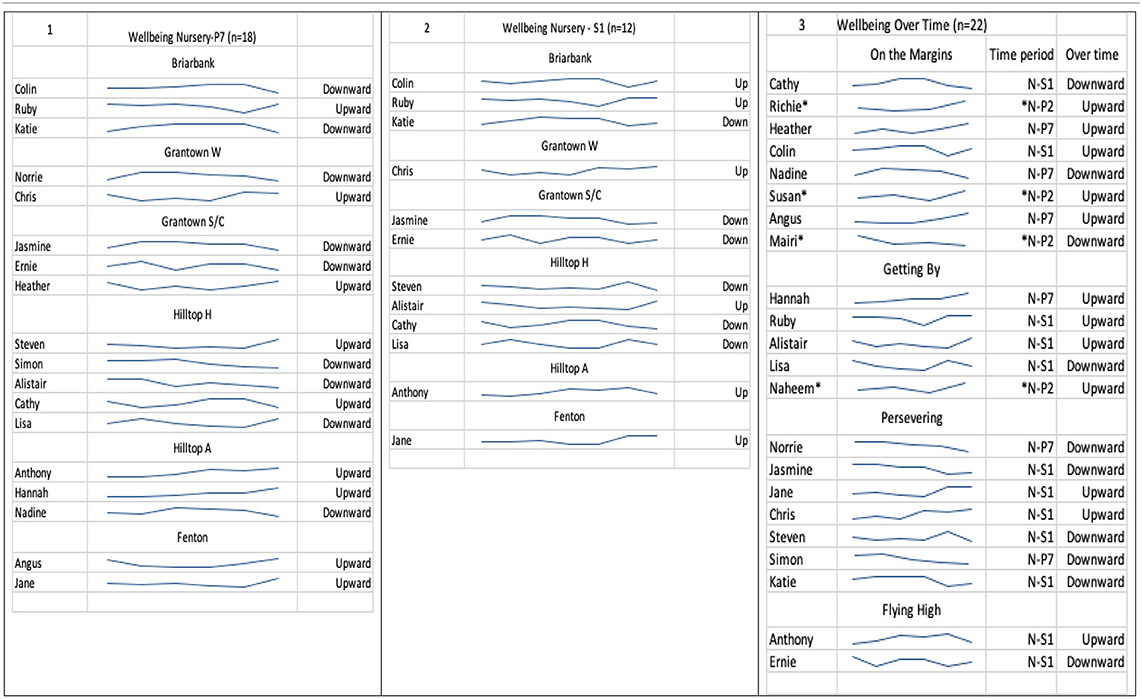

The challenge of working with different forms of data in terms of analysis over time is recognised. The data was collected over the three phases of the longitudinal study at 10 time periods, nine of which are presented here (excluding home-based assessment in the summer before school start) and is an analysis of the qualitative and quantitative data held that is relevant to profiling attainment, including school leaving data from the Senior Phase—time-period 10 up until each individual's school leaving date. An example of each type of trajectory is included in each of the following case studies. Two tables present the attainment trajectories by class attended. In Table 4.1 the direction of attainment from nursery leaving to P1 entry shows that 13 of the focal children dipped in numeracy and literacy attainment in their first school term, while for nine attainment rose. By the end of their first year in school (Table 4.2) 19 children sustain their initial trajectories of dips and upwards trends, dip continues, while two of the youngest, Ruby and Richie, recover from the dip, and Angus' initial positive trajectory drops. By the summer of their second year in school (Table 4.3) nine children continue this downward attainment trend, six sustain an upward trend and the other seven have more fluctuating profiles. In the Case Study Section some explanatory factors for consistency and change are considered.

Table 4. Attainment sparklines: (1) Nursery leaving to P1 entry; (2) Nursery leaving to P1 summer; (3) Nursery leaving to P2 summer.

In Table 5 the four columns show attainment trends in the first (5.1) and second (5.2) major educational transition. Columns 5.3 and 5.4 show the direction attainment took from nursery to P7 and from Nursery to S1. A number of studies refer to the secondary school dip: it is well-understood that there is a dip in confidence, wellbeing, and attainment for many children in the transition to secondary education (Galton et al., 1999, 2003; McLellan and Galton, 2015), with a need for more professional focus on the academic as well as the social side of transitions. In the present study for the focal children more than half (n = 12) experienced such a dip in attainment, however 10 did indeed experience such a dip.

Table 5. Attainment: (1) Nursery to school entry; (2) Primary 7-senior 1; (3) Nursery leaving to P7; (4) Nursery leaving to S1.

The attainment trends in literacy (English) and numeracy (Maths) over the 22 focal children's nursery to school leaving career are linked to their total Universal Tariff Points Scores in Table 6, showing that in three of the four attainment quartiles there is a mix of upward and downward attainment profiles. For 12 of the 22 focal children their attainment dropped overall from nursery until school leaving, while for 10 attainment rose over time. In both the “On the Margins” group and the “High Fliers” there is considerable consistency in the direction of attainment, with only Richie showing an upward trend over time despite his overall scores being well-below the mean. This raises questions about what “doing well” may mean, with those in the “Getting By” and “Persevering” quartiles achieving both because of, and against the odds.

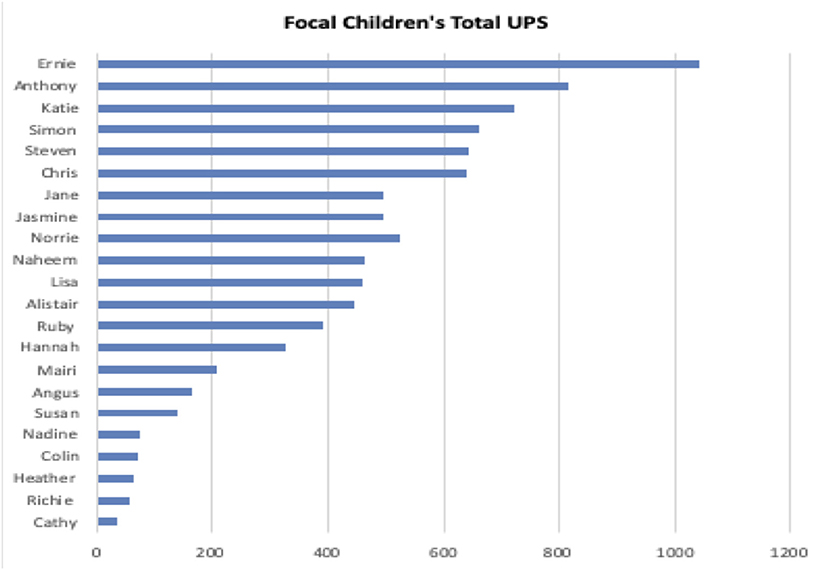

The total Universal Tariff Points (T-UPS) each of the focal children had accumulated by school leaving are shown in Figure 2, given in detail in Table 6. Of the 22 children whose attainment data is reported here, six * left school at the end of S4, aged 16; 2 ** left a year later at S5 and 14 continued in school until the end of S6: the last year of schooling in Scotland.

Figure 2. Focal children's SQA national assessment in S4, S5, and S6 showing total scores accumulated in English and Maths and in all other subjects taken.

These data may be compared with the Scottish average tariff points scored in each relevant year in Figure 3, with the significance of such positioning shown in the four case studies that follow.

For S4 leavers in the study the national average of Scottish school leavers was 341 T-UPS; for S5 leavers it was 356 and for S6 leavers it was 372. Of the six focal children who left school in S4, only Susan (140 T-UPS) had more than 80 tariff points and all were considerably below the Scottish average for school leavers. Two of these six moved to new schools: Cathy (Case Study), 37 T-UPS, and Heather with 88 T-UPS points; one was recorded as unemployed and three went on to college to complete further study. Lisa (461) and Hannah (328) who left in S5 fell each side of the national average in their year of 356 T-UPS, while 12 of the 14 who stayed on to 6th year achieved above average T-UPS and two had lower than average scores but fall into the group of school leavers who accumulate more tariff points the longer they stay in school, and therefore do better than expected. For those who left in sixth year the variation in points achieved was 836 T-UPS, with Mairi achieving 207 points and Ernie (Case Study) achieving 1,043. When all 22 focal children's school leaving outcomes are considered this gap between tariff points widens to 1,006 T-UPS. The following case studies profile Ernie and Cathy: children who lie at the extremes of this range, and positions Ruby in the “getting by” group, while Steven is in the “persevering” group.

Consideration of attainment through a school career, how it accumulates in school leaving attainment and the future impact of academic outcomes on individual lives each raise many issues. Trajectories are rarely evenly upward or downward: to understand what affects not only the end point differences, but the fluctuations in the journey through education, the intersection of wellbeing and attainment with major educational transitions is presented by plotting their alignment.

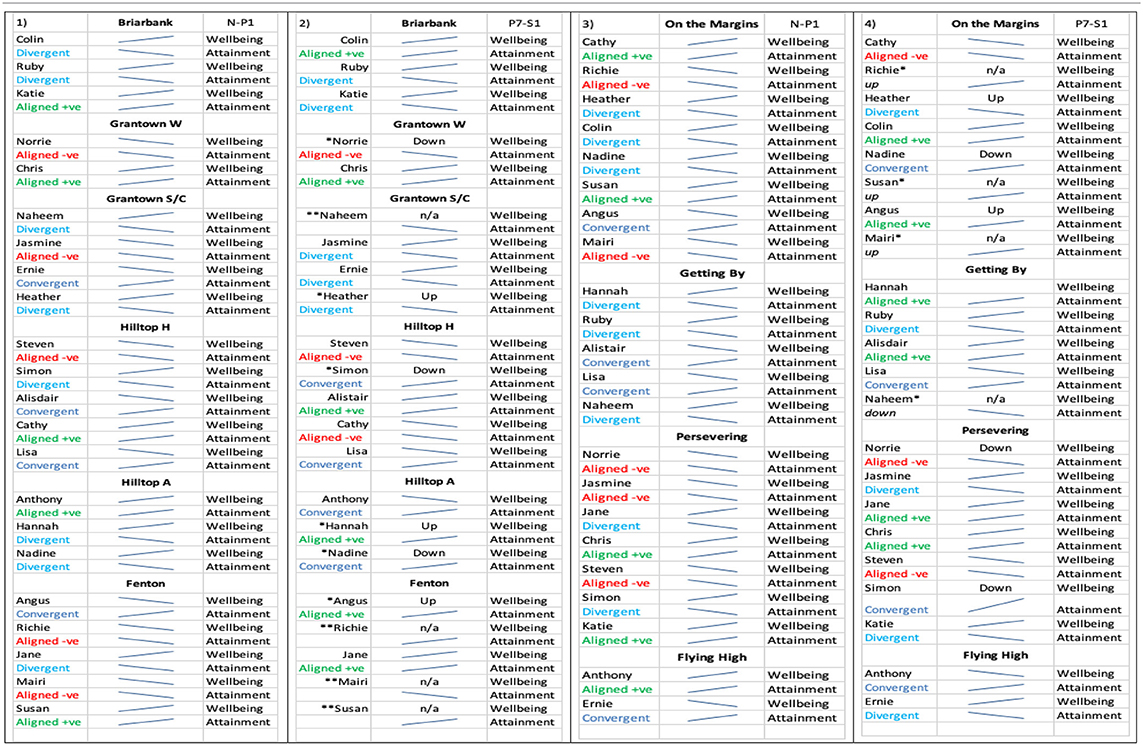

Aligning Wellbeing and Attainment Over Time

Turning to what extent wellbeing and attainment align over time, and particularly at transition, two ways of looking at this are important as shown in the model in Figure 4: firstly is there alignment of wellbeing and attainment within each transition and secondly are the early patterns sustained across transitions? Direction of travel in pedagogical wellbeing (Pyhältö et al., 2010) is also visible in these trajectories through the upward and downward alignments and the more divergent or convergent pathways as addressed in the following discussion.

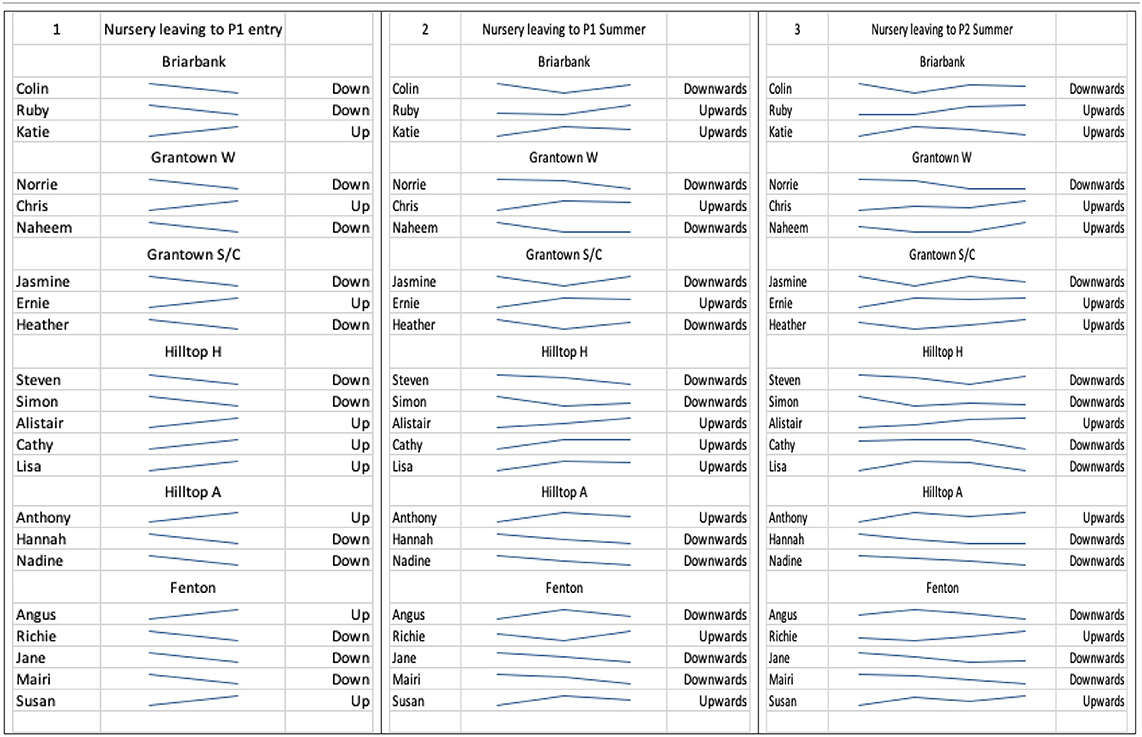

At the Nursery to Primary 1 transition (Table 7.1) 10 of the focal children's trajectories in wellbeing and attainment were aligned: in five of these both wellbeing and attainment improved over the transition whereas five children's wellbeing and attainment both dropped. For a further eight focal children attainment and wellbeing diverges in the move from nursery to Primary 1 and for the remaining four wellbeing and attainment converge: coming closer together over time. In many ways such alignments are the more expected outcome: the literature suggests a relationships between positive wellbeing, engagement and attainment (Upadyaya and Salmela-Aro, 2013; Cadime et al., 2016; Mowat, 2019) and conversely a drop in engagement and wellbeing may herald a drop in attainment. The extent to which this sample of children reflects the peer group, variability is to be expected in attainment and wellbeing at times of transition. Patterns of wellbeing and attainment within and across transitions is shown through sparklines of available evidence in Table 7—alignment of wellbeing and attainment within and across Transitions.

Table 7. Alignment of wellbeing and attainment: (1) N-P1 by class; (2) N-P1 by attainment groups; (3) P7-S1 by class; (4) P7_S1 by attainment groups.

At Primary to Secondary transition seven of the 18 children for whom both wellbeing and attainment data are held show consistent patterns across transitions; for five wellbeing and attainment align by primary secondary transition with upward trajectories; for the other six children patterns vary across the two transitions (for six of these children* wellbeing data is round one ACS only). Looking at wellbeing and attainment across transitions it is possible to identify four children whose wellbeing and attainment aligns at both transitions—two downwards (Norrie and Steven), one upwards (Chris) and the fourth (Cathy) mixed. For two (Ruby and Heather) the divergence between wellbeing and attainment is maintained as a pattern through both transitions, while Lisa experiences greater convergence between wellbeing and attainment as a pattern through both transitions. The wellbeing data are incomplete for four children**, however the nature of their attainment is replicated in both transitions, with Naheem and Mairi showing falling attainment and Richie and Susan showing rising attainment over both transitions. For the remaining 12 children there is a mix of divergent to aligned (Colin, Hannah, Jane); aligned to divergent (Katie, Jasmine); divergent to convergent (Simon, Nadine); and convergent to divergent (Ernie) trajectories over the two major transitions. By considering their wellbeing and attainment, separately and together, this sample of children's experience can be embedded in the wider picture of school-learning and accountability of the time as presented in Figure 3—Average Tariff Score of School Leavers and Focal Group Tariffs. Finally columns three and four in Table 7 group the focal children in terms of their attainment quartile. Again alignments are very mixed, suggesting that wellbeing and attainment are but two factors intersecting with transitions in education.

Reflections on the Results Presented

The results presented confirm that homogeneity should never be expected in any group of school pupils or school leavers. Overall this longitudinal study suggested that a “push for sameness” exists in our education systems, perhaps as a way to manage the reality of diversity. This negates the very real differences that exist between children and which merit differentiated approaches if each is to do as well as possible while maintaining their self-respect and sense of belonging (Allen, 2018a,b) in school. Consequently grouping children by characteristics is inevitably going to be a fluid and changing process. In reality individual learning is rarely linear, though in education we have worked hard to present logical sequences of learning and what is to be taught in hierarchies of difficulty. With younger children particularly, this means taking account of an increasing abstraction in thinking to establish foundations in learning and to continue to build on these throughout school education. To some extent this accounts for the focus on literacy and numeracy as tool subjects through which other learning is made much more accessible. Many variables exist to knock this planning sideways, for example: changes of teacher, changes in pedagogy, grouping on a basis of ability, results, or indeed socially. Consequently in longitudinal study different ways to bunch children together are likely to emerge. One of the ways is presented here, through the following case studies.

Four Case Studies: On the Margins, Getting By, Persevering, and Flying High

For the representative sample of 22 focal children in this study, attainment over their school career, as previously explained, varied by 1006 UPS Tariff points. Grouping on a basis of UPS tariff points quartiles (Q) results in four groups of uneven size—Q1 = eight lower achieving children, Q2 = five low middling; Q3 = seven high middling, and Q4 = two high flyer. Of course attainment is not the only characteristic of these 22 children, nor the only way to group them. A focus on any characteristic, for example wellbeing, post-school destinations, socio-economic status, family social capital, resilience during transition or indeed humour, appearance and gender would all result in different groupings. Grouping by attainment places some children on the lower margins of their year group, some who get by, others who persevere against different odds and some who are high fliers: but these groups only have an academic consistency. As soon as wellbeing, personal dispositions, individual strengths and circumstances and classroom and school contexts are taken into account then diversity becomes apparent in all its glorious differences. One case study from each of these academic quartiles is presented here. The wellbeing and attainment trajectories generated and what they may mean are exemplified through the following case studies which draw on a range of explanatory factors.

Case Study 1—On the Margins

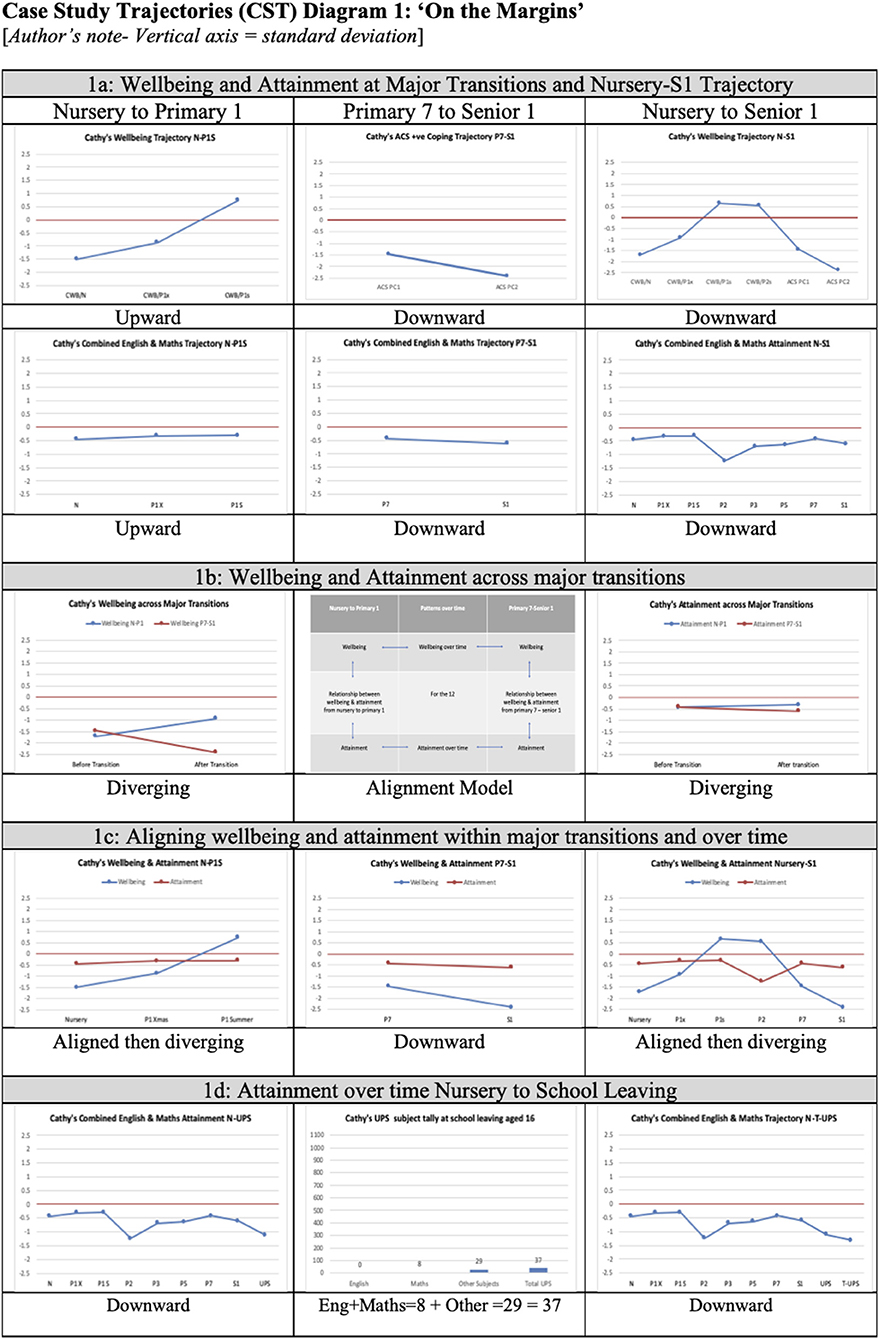

Case Study Trajectories (CST) Diagram 1—“On the Margins”

Cathy attended Nursery School in the mornings and a private nursery in the afternoons, coping with two quite different settings, and the lunchtime commute between them with her grandparents while her parents were at work. Cathy enjoyed her morning nursery more when her friend Laurie was there with her, settling in to a wide range of activities and chatting with other children but nudging Laurie to reply if adults spoke with them. Knowing Laurie was going on to a different school staff were aware this represented a bit of a challenge. Only with her teacher, Mrs. French, was Cathy more forthcoming: with her she participated in storeys and discussion.

With others from her morning nursery which had an overall Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale (ECERS) (Harms et al., 1980, 1998, 2005) score of 6.4, Cathy moved at just over 4½ to Hilltop Primary School P1 which was less tuned to younger children (ECERS score 4.3). As in nursery Cathy formed a good relationship with her teacher, finding some security in the increased formality and predictability of a teacher-led approach where child choice was quite limited. Her wellbeing moves from 1.5 standard deviations below the mean in nursery (she herself says later she was happier in her other nursery) to 0.75 above at the end of Primary 1 and then plateaus.

Cathy's self-report ACS score in P7 is little above her wellbeing score in nursery days, and drops further during the transition to secondary when at 11 years 7 months (Case Study Trajectories- CST Ia). She goes to Fernbank Secondary School with the majority of her class, and her capacity to cope becomes non-productive (ACS Round 2). Similarly her slightly upwards attainment trajectory in the move to primary school changes to a downward trajectory in the move to secondary and overall from nursery to S1 (CST1a) (Diagram 1). Cathy's Primary 7 teacher talks warmly about her—“Cathy has a fine sense of humour- she enjoys my jokes. She is very friendly and outgoing but not pushy—she's not a high flier, but is quite confident socially. She will be fine in High School—I can't see her getting in with a bad crowd.” (TI). Cathy's father took on the P7 parental interview: he believed that Cathy would transfer well to secondary, was very positive about her nursery and primary experience, having three ambitions for her secondary education: that Cathy would do well, that she will get on well with others and would hopefully have good teachers. His one concern for secondary was bullying. Cathy attended all of the primary-secondary transitions research group sessions from P7-S2, contributing in a lively way and enjoying the company of others in the group.

Cathy's wellbeing and attainment profiles diverge (CST1b) across both major transitions. An initial upward alignment within the first transition (CST1c) becomes a downward alignment of wellbeing and attainment from P7-S1 as reflected in the full nursery-S1 trajectory. On leaving Secondary school at the end of S4 at 15½, her future destination was recorded as “transfer to another High School?” She leaves Fernbank with no UPS points in English, only 8 UPS points in Maths and 29 in other subjects (CST1d) with an overall UPS score of 37 points. Cathy's own attainment trajectory remains below the mean throughout a 12 years educational journey. For Cathy this is not the end of the school storey, later in S6 she responded by letter and questionnaire that she had been very unhappy in her original secondary school, had been badly bullied, and had left to go to a different school in the neighbouring council area. She concludes “Going into a new secondary is a big step but when you get there it is fun and easy. I cope with new experiences very well now because of everything that has happened. In the end I did better in my exams than I thought I would. I'm worried about growing up, but at the same time I can't wait. I've applied for a bank job and some college courses: mainly administration. Also I may go to University.” [Transitions continuation study: S6].

For much of her educational journey and particularly at times of transition, Cathy is quietly at the margins of the school experience. She found relationships with particular teachers supportive and encouraging (nursery, P. 1 and P. 7) and over time became visibly more confident with her peer group, however this proved not to be an easy path until at 15½ she moved to a different secondary school and reported being transformed by the experience.

Case Study 2—Getting By

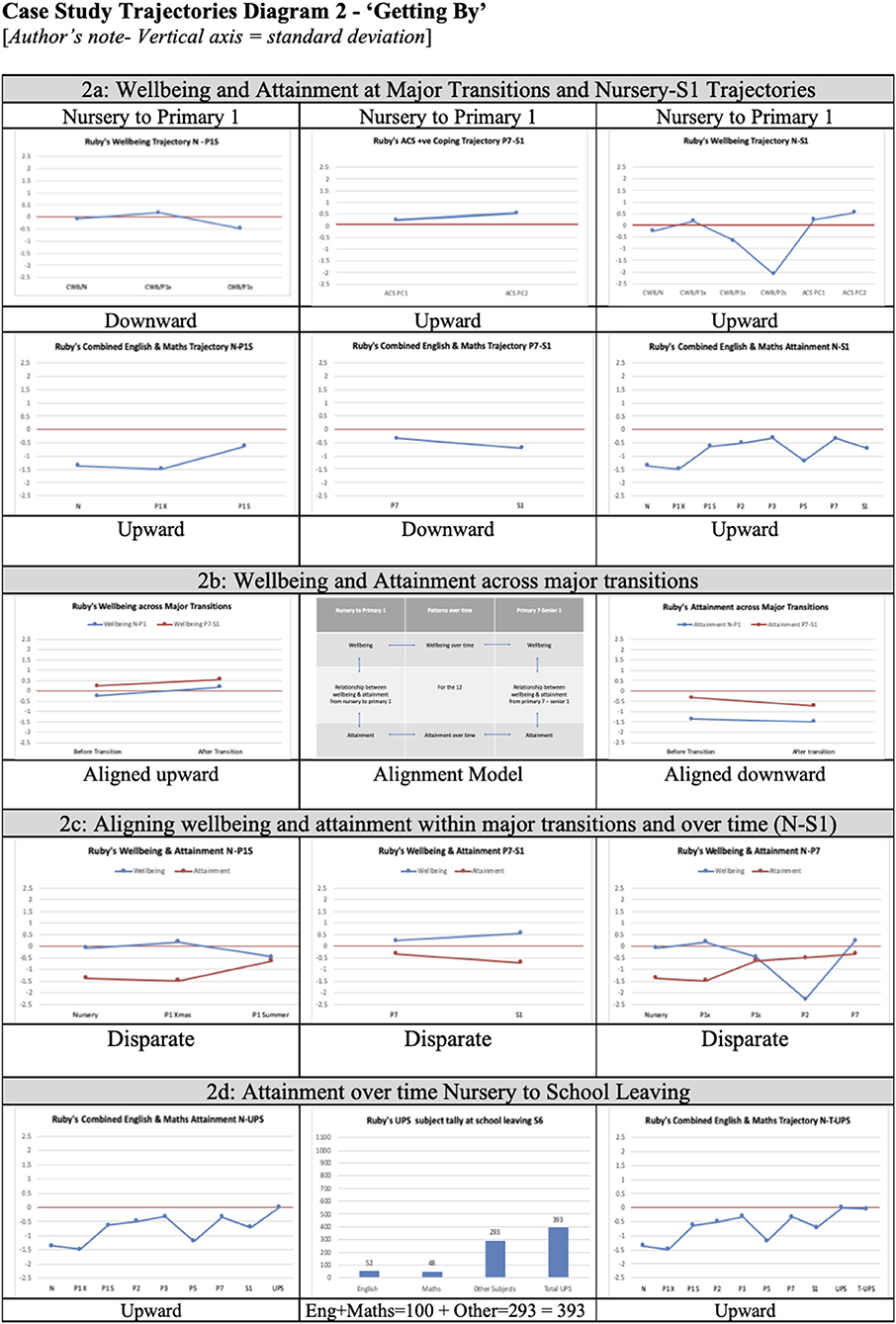

Case Study Trajectories (CST) Diagram 2—“Getting By”

Ruby lived with her parents nearby Briarbank Nursery: starting there at 3 years 7 months. She was the first of two (later three) children, her father was working, while her mother was at home with the two children. With her nursery classmates Ruby benefited from a well-developed environment, with particular strengths in language and reasoning (7.0), adult-child interaction (6.4), and programme structure (7.0) with an overall ECERS score of 6.0. When Ruby moved to Briarbank Primary at 4 years 7 months, the collaborating nursery and primary 1 teachers saw the value of starting school with a friend (Ladd, 1990) and she was placed beside her slightly older nurturing friend Katie from nursery. Ruby was a novice in the school classroom, although she apprenticed herself to Katie (Rogoff, 1990) as had happened in nursery and Katie continued to scaffold Ruby's learning. Ruby took some time to understand and play the role of a school child, in contrast to Katie who was firmly school child from the start.

Every morning in Briarbank P.1 began with a “morning workshop" —a time when children could choose how to spend their time. The ECERS score was, like the nursery, an overall 6.0, with a continuity of quality across the same three dimensions of language and reasoning (7.0), adult-child interaction (7.0), and programme structure (7.0). The nursery teacher and her primary colleague had visited each other's classrooms, taken time to get to know each other and had shared information about the incoming children.

By Primary 7 Ruby was still friendly with Katie, she had developed a great sense of humour and together they undertook the school video tour (ST.1) element of the study. Her P.7 teacher wasn't worried about Ruby's move to secondary (TI.1), she found her a “very bright, cheerful little girl.” In school work, her strengths were her language work, with good spelling and a good imagination for storey writing. Ruby's general knowledge was noted to be very good (T1.2), and although capable in Maths, she lacked a bit of confidence and was reported as “tending to sit back and not push herself .” Similarly there had been letters home about the importance of getting homework done: her teacher reported that “she can, but doesn't: sometimes homework is incomplete.” At 11 years 7 months she started with a number of her classmates at the very big Briarfield Secondary School. When completing the Adolescent Coping Scale either side of transitions to school Ruby rates herself in general terms as a productive coper, solving issues herself or in reference to others.

At each transition Ruby's wellbeing initially improved (CST 2a) (Diagram 2) though in early primary it had dropped by the end of the school year, whereas her attainment dropped on school start and rose by the school year end. Despite such fluctuations wellbeing and attainment went upwards overall in the years from nursery to senior 1 with wellbeing (upward) and attainment (downward) consistently across the two major transitions (CST 2b), but quite disparate when considered within major transitions (CST 2c). Overall she achieved an upward attainment trajectory in her 14 years educational journey (CST 2d). Her overall attainment in relation to the rest of the focal group is low (2nd attainment quartile) but it is a personal upwards trajectory which at 393 T-UPS is slightly above the national average for her year (Table 5). Ruby stayed on all through school, leaving at the end of S6. One third (n = 45) of the cohort (n = 150) were in the youngest quartile on starting school—Ruby was among the very youngest of this group and there is evidence in her trajectory through school that, although she “grew into herself” as a warm, funny and engaging person, school was always a bit of an effort: her attainment and wellbeing trajectories place her in the “getting by” quartile.

Post school she worked, but planned to go back to study with the intention of improving her grades. Her case raises many questions about the timing of school start which are addressed in the discussion, she maintained her sunny personality throughout and this outlook helped her to “get by" —it is worth reflecting on whether she might have had a different educational journey had she started school the following year. Ruby's combined English and Maths attainment trajectory shows progress over time. She had a certain happy-go-lucky approach to life and to school: “Getting By” characterises her approach accurately.

Case Study 3—Persevering

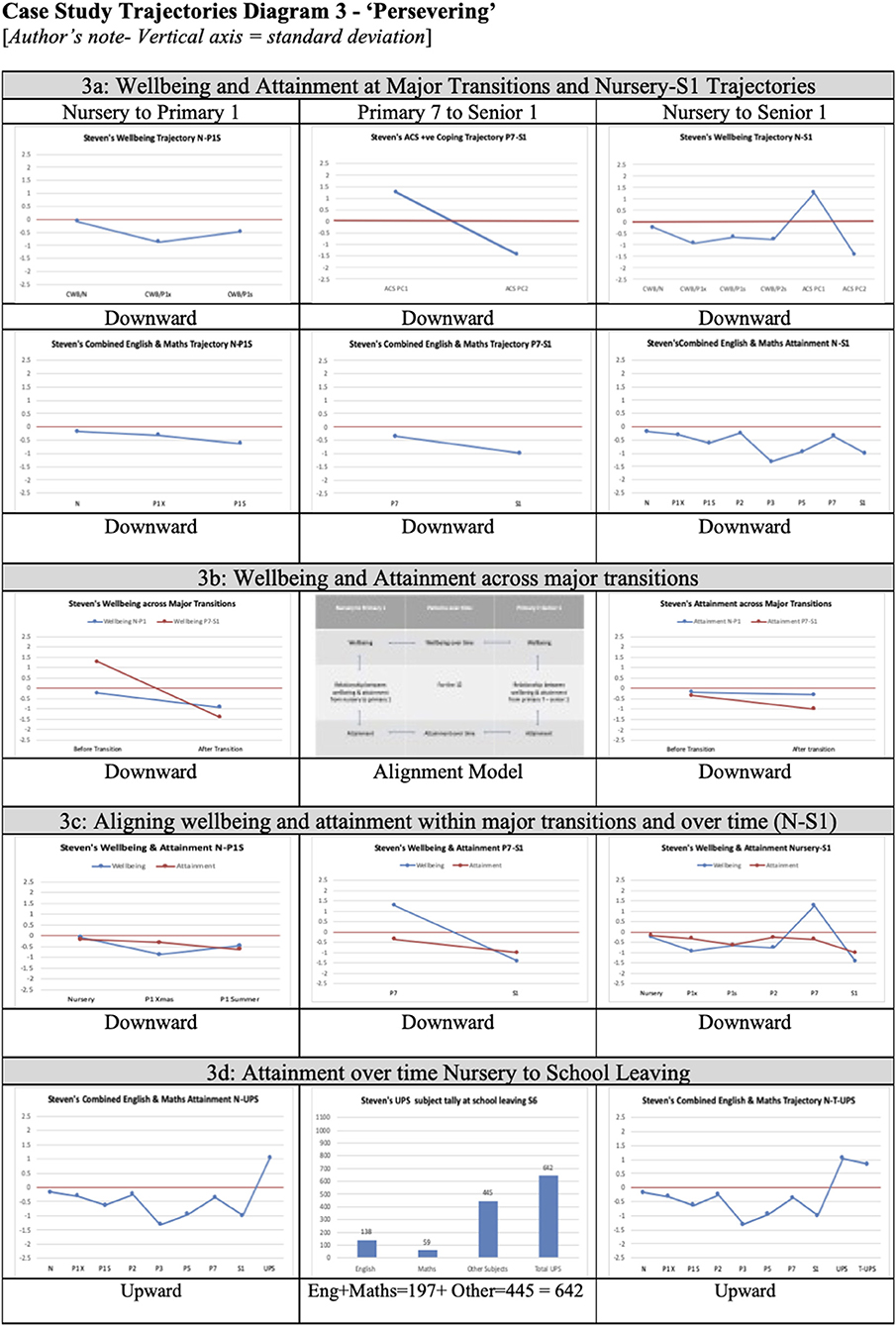

Case Study Trajectories (CST) Diagram 3—“Persevering”

Steven had a happy year at Greenbank Nursery School. He was 4½ at school start when he moved on to Hilltop Primary School with numbers of others from his nursery, and later with most of the class group to Fernbank Secondary at 11½, continuing on until S6. He was the first of two children, his mother was at home with the baby and his father worked fulltime. A cheery wee boy, Steven had been a very premature baby and was currently going to speech and language therapy. Although Steven's comprehension was good and he was imaginative in his play, in nursery he struggled to have people understand what he was trying to say, but this didn't seem in any way to intrude on his relationships with others where he engaged easily and was particularly keen on block play, creating circuits and obstacle courses with other boys in their self-formed groups often outside. His parents were vexed about what would be right for Steven and considered whether he would be well-served by his entitlement to a further year in nursery and how he might cope in primary school. They took the decision for Steven to start school with his nursery group, though he was just 4½, feeling the nursery supported and prompted their decision.

The tremendous nursery choice, range of experiences and freedom of movement was not replicated in primary school: apart from lunchtime the P1 children only left the classroom to go to the gym, the toilet or out at playtime. In P1 a sedentary uniformity was built into the day and yet because of their different starting points, the inexperience of their teacher in P1 and the children's dispositions, each experienced it differently. At Greenbank the staff were strong on interaction (6.0), language and reasoning (7.0) (ECERS overall 6.4) and this supported Steven well. In Hilltop P1 interaction (4.8) and language and reasoning (4.0) (ECERS overall 4.3) was much less engaging. Steven's poor articulation remained a concern and it was thought it might be symptomatic of other issues so it became important to explore his engagement with print and capacity to interpret meaning. The potential for early identification was taken seriously in Hilltop Primary and turned out to be a lasting benefit to Steven who was diagnosed by a specialist learning support teacher as dyslexic.

During both the transition to primary school and the subsequent transition to secondary school Steven's wellbeing and attainment dropped (CST3a) (Diagram 3). His initial dip in wellbeing on starting primary began to climb by the end of the school year, but Steven stayed below the focal group mean until P7 when his coping score rose to 1.25 standard deviations above the mean before dropping by 2.75 standard deviations on transition to secondary, dipping 1.5 standard deviations below the focal group mean. Although in P7 he reports a loss of confidence and worries about whether he will be able to keep up in secondary school, he is a productive coper. Steven's teacher (T1) described him as a quiet diligent boy who was well-behaved and polite. Finding he tries, she did not see him as a high flyer.

During self-completion of the Adolescent Coping scale he focuses on being dyslexic and what this means for transition to secondary: as a problem solver Steven's main strategy is to make sure people know. Across the two major transitions his wellbeing and attainment both drop (CST3b) but for attainment this is a very slight drop as he moves from Nursery to P1. Aligning wellbeing and attainment in relation to each other (CST3c) within each transition at P1 Steven's combined trajectory in English and Maths diverge, but move closer together once transition has passed, while at P7-S1 both wellbeing and attainment fall.

Steven's persevering disposition and warm personality serve him well and by school leaving in S6 his combined attainment in English and Maths had moved from being a consistently below average profile to just over one standard deviation above the mean for the focal group. When all other subjects are factored in, in relation to the group he maintains a score one standard deviation above the mean (CST3d): his combined English and Maths score sits at 197 UPS, he earns 445 UPS for his other subjects resulting in a total UPS score of 642, above the national average tariff score of 497 for those leaving with Highers and resulting in an offer for university: his perseverance pays off.

Case Study 4—Flying High

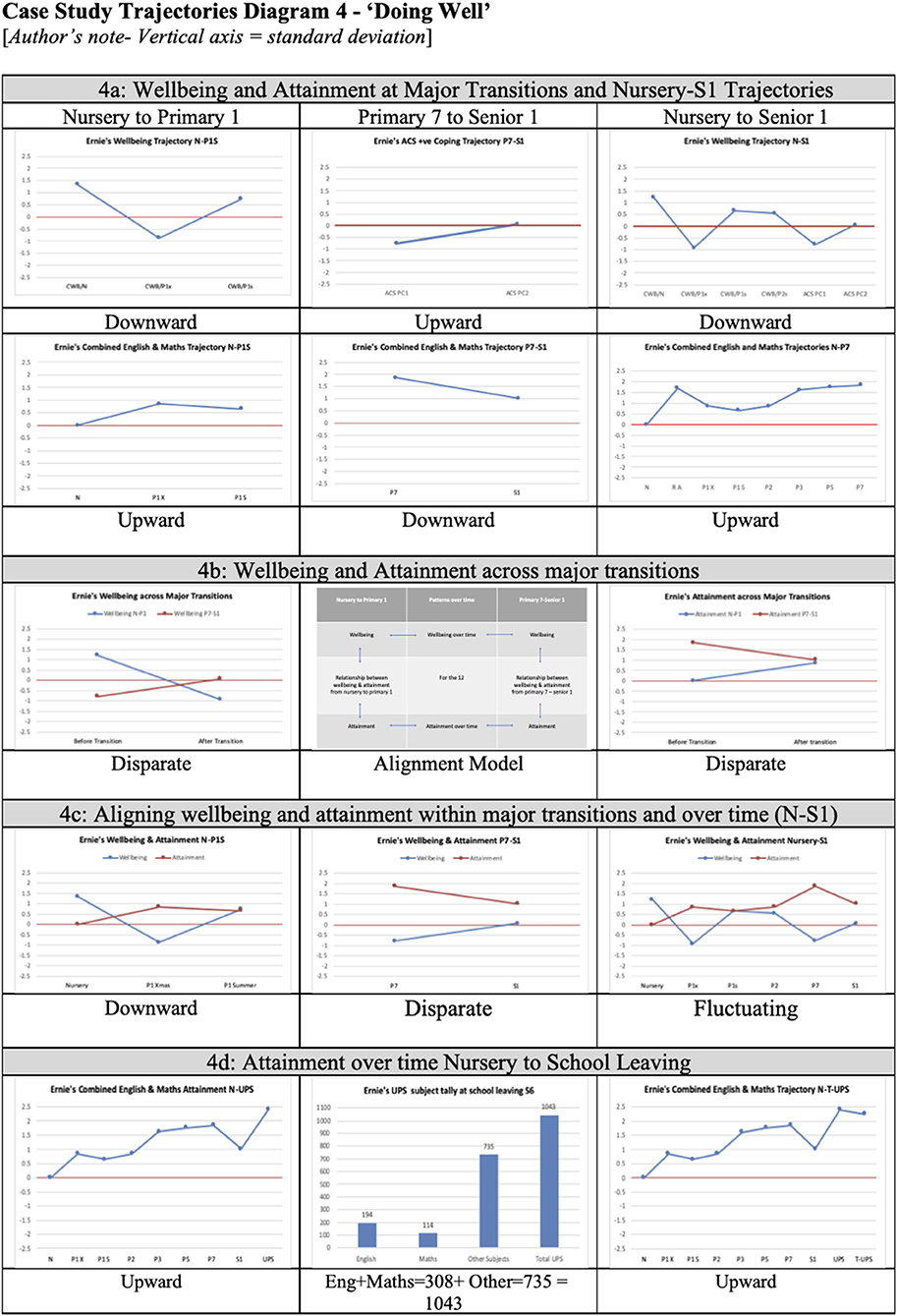

Case Study Trajectories (CST) Diagram 4—“Flying High”

Ernie was the older of two children, at the time his mother was at home caring for the baby and father was working full time. He was 5 years 1 month starting school, after a year of part-time nursery at Valley Nursery School where he involved himself in all available learning opportunities. Ernie particularly enjoyed being part of the small group with his key member of staff and contributed well at storey times and in group and self-chosen activities. In the weeks before nursery ended he spent some time every day making a Mr. Men book, he played orally with words and numbers, and had a special relationship with Mollie who was his best friend. Mollie was younger, but an active learner, and she often challenged Ernie's ideas as they enjoyed playing together and negotiating what they would do next. Ernie was a particularly numerate child, evidenced by a skill and speed in addition and subtraction, his knowledge of number word sequences and his capacity to play with number ideas and pose questions (home based assessment interview). On the ECERS profile Ernie's nursery had a higher average score in June (6.3) than his new primary class did in September (4.7).

He and Mollie were the only children from Valley Nursery School going to Grantown Primary School but unlike Ruby in Case Study 1, he was separated from Mollie who was placed in the parallel P1 class on a basis of age. For a while he looked lost and displaced and sought reassurance: constantly checking everything he was asked to do, and although this was recorded in his Christmas time summary, it was not addressed in any obvious way by his teachers. He brought this mathematical know-how to school but this was not picked up and he simply conformed and completed the Maths workbooks of the time with great ease and without question. In P1 group meetings with the researcher at the end of his first year in school, faced with a choice about what to do, Ernie said “Well I'd really like to draw a train going through a tunnel, but it's a bit hard, so I'll just do sums instead.” He proceeded to write challenging numerical problems, talk about them and solve them, going on to achieve his drawing challenge as well. Ernie moved school in P4 as the family had a house move. He continued in the study and at the primary-secondary transition he completed holiday diaries and a Transitions Journal that provided a detailed account of the summer before school, recording that he was excited, anxious and curious about what Secondary School would be like, in discussing the move with friends he confided that his friends said “It'll be fun and they can't wait. They don't say what they are worried about.” Thinking about himself as a learner Ernie says “I think I am a good learner and I learn quickly. When I am learning something new I am curious about it and look forward to it.” He continued with the study for the lifetime of the primary-secondary transitions group.

Ernie's early learning in nursery went at a gentle pace, he developed relationships but lacked confidence despite a continuously upward attainment trajectory. There are visible dips and recorded anxieties around transitions, as shown in the two rounds of the ACS gauging coping strategies: in round one at the end of P7 he comes out as a coper who problem solves and refers to others as and when needed. By the time he has navigated the transition to school, he has withdrawn from seeking so much help from others, still problem solves but is inclining to a less productive approach.

Throughout his educational journey Ernie's wellbeing fluctuates, rising in both early primary and early secondary once transition is accomplished (CST 4a) (Diagram 4), while his attainment drops at each major transition although remaining above the mean (CST 4a). The plotted wellbeing and attainment trajectories across major transitions (CST4b) are disparate and when considered together at major transitions do not align (CST4c) with wellbeing downwards overall in the move from nursery to primary 1, disparate during the primary-secondary transition and fluctuating over the six timepoints assessed from Nursery to Senior 1. Despite these odds Ernie's combined attainment (CST4d) in Literacy/English and Numeracy/Maths from nursery until school leaving starts at the mean and apart from the dips in attainment recorded in both the P1 and S1 assessments, rises 2.5 points above the mean. Ernie's Universal Points Scores in English and Maths (338), other subjects taken (735), and overall total (1,043) are each the highest among the focal group children, and are 25% above Scottish national averages of the time for those leaving with Advanced Higher. In comparison to his recorded starting point in nursery he flew high by the end of his school career, exceeding expectations. His destination notes record a place at University.

Discussion

On the Margins, Persevering, Getting By, or Flying High?

By considering both quantitative and qualitative data it has been possible to present the focal children's educational journeys through standardised trajectories of attainment and wellbeing illustrated by four case studies. While the four examples given are representative of four attainment groupings, it is the variability of their profiles and common ground between them that raises questions about the relationships between wellbeing, attainment, and transitions. Individual person characteristics such as reticence, humour, diligence, and anxiety contribute to how individuals experience their world. Bronfenbrenner categorises person characteristics into demand (e.g., age or gender), resource (e.g., past experiences, ability, and material resources such as family's economic situation), and force characteristics (e.g., temperament, dispositions) (Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 1998). Such characteristics also influence the interactions between individuals, including the proximal processes involved in the social practices of learning and teaching in classroom contexts. Such characteristics may be predictive or indeed protective. Could Cathy's quiet disposition, ways of coping and need for affirmation through teachers and friends have been predictive of the bullying which in her view pushed her further to the margins than she could tolerate? Might a later school start (Graue et al., 2003; Dee and Sievertsen, 2015) have been helpful for each of Cathy, Ruby and Steven who were equally young starting school? Ruby gets by through humour, positive connections between school environments, sustained peer scaffolding through friendship, teachers who took time to know her well and the resulting personal agency. For Steven, his diligence and perseverance in the face of learning challenges and the self-awareness that brought, combined with steady friendships and the school “know-how” he acquired, to help him succeed against the odds. For Ernie, he seems to succeed despite school: a highly numerate child with capacities that put him in a small percentage of children who are developing the skills he was by age six (Bobis et al., 2005), yet this was not recognised by his teachers. For Ernie the anxiety of not being recognised as a learner early on changed over time and by transition to secondary his knowledge of himself as a learner sustains and supports him as a high achiever.

Variability in Outcomes Influenced by Person, Processes, and Educational Contexts Over Time

The nature of each person's journey through school may vary considerably from her/his peers: this variation may be interpreted through other factors, e.g., relationships, school environment, individual choice, individual characteristics, family dynamics and their relationship with education, age, gender, ethnicity, and how each informs a sense of self and identity as a learner. Given such variation it is reasonable to think that the ways in which children make the transition from early childhood into full-time schooling is likely to have long lasting importance, and may be mirrored in their next major vertical transition: from primary to secondary schooling. Drawing from the literature, in particular from longitudinal studies, such factors indicate four major explanatory themes have a role to play in the study and understanding of transitions: overall attainment, individual characteristics, environment, and relationships. The nature of classroom environments (Allen, 2018c, part 3), school climate (Rudashill et al., 2018) and pedagogical wellbeing (Pyhältö et al., 2010) during these critical educational transitions also emerge as influential over time.

School Transitions—Explanatory Factors

It is likely there are many variables that can affect an individual's journey through education and their attainment up to the point of school leaving: these may include, for example, family aspiration, age of school start, teacher expectation, individual capacity, the quality of pre-school education and its capacity to offer the best possible start, the quality of primary and secondary education, the home learning environment, the ways in which relationships support learning, friendships, engagement in school life, adaptation to the different culture of the school, the learning environments, public policy, curriculum reform and its enactment in school, transitions processes, and significant others. The assertion in the literature of the time when the informing study began, was that a good first transition set children up for later school success and positive outcomes (Rimm-Kaufman and Pianta, 2000; Pianta and Kraft-Sayre, 2003). This raises the question of what is understood by positive outcomes. These attainment and wellbeing findings have therefore been complemented by a biographical approach to school experiences and outcome expectations through surfacing the focal children's early learning trajectories, their assessment profiles throughout the 14 years of study, their wellbeing profiles from nursery through to secondary education and their later biographical accounts, in the identification of key explanatory themes in the transitions journey.