- 1School of Educational Science, Shenyang Normal University, Shenyang, China

- 2Institute of Leadership and Education Advanced Development, Academy of Future Education, Xi'an Jiaotong-Liverpool University, Suzhou, China

- 3College of Education and Human Development, University of Massachusetts Boston, Boston, MA, United States

This study explores Chinese college students' integrity status and the influencing factors to understand the best practices of Chinese colleges and universities on the issue of integrity cultivation, which is critical for the quality of Chinese higher education. A mixed method combining the quantitative and qualitative data were applied. Respondents from 63 Chinese higher education institutions to the questionnaire were received, which suggested the medium level of Chinese college students' integrity. Compared with the integrity education in western countries, Chinese higher education institutions pay attention to relationship integrity, financial integrity, and employment integrity in everyday life, in addition to academic integrity. The results of csQCA analysis indicated that the university management played an important role in students' integrity and the main influencing factors are policymaking that is appropriate to students' needs, the platform that caters to students' diversified interests, and the supportive environment for integrity. The interactions among the three factors affect and improve Chinese college students' integrity levels.

Introduction

There is a growing concern about students integrity in higher education. This can be partly attributed to the increasing number of reported cases, stories, and scandals about corruption, academic misconduct, and other breaches of integrity in colleges and universities worldwide (Kisamore et al., 2007; Macfarlane et al., 2014). Studies suggested that the possible causes of the integrity crisis including but are not limited to the expansion of higher education, the changing value underpinning higher education, the marketization of higher education, and the evolution of the internet and social media (Kezar, 2004; McNay, 2007; Prisacariu and Shah, 2016; Sefcik et al., 2020) Integrity has become a significant concern because it impacts higher education institutions in their reputation and credibility, attainment of educational goals (Macfarlane et al., 2014; Simola, 2017; Moyo and Saidi, 2019; Fudge et al., 2022), and the “charter between higher education and society” (Kezar, 2004).

A plethora of research has been conducted to understand the factors associated with academic dishonesty and misconduct, using the individual difference approach and contextual difference approach (Kisamore et al., 2007; Simola, 2017). These approaches focus on demographic variables, personality constructs, student behaviors, and situational factors, such as faculty and peer influences. Academic integrity draws the most attention, the discussions of which are becoming increasingly important in higher education not only in western countries but also among Chinese academics. The research focus looking into academic integrity is relevant recent and policy driven in China, which reflects the priority of strengthening academic ethics and culture in the development of the Chinese higher education system (Macfarlane et al., 2014). However, integrity, in a larger sense, is not confined to academic integrity. It refers to wholeness and completeness, a fuller understanding of which can foster holistic student development that extends beyond the classroom (Wong et al., 2016). This study describes the students' integrity using four categories after analyzing the various characteristics: academic integrity, relationship integrity, financial integrity, and employment integrity (Guo, 2017; Han, 2017; Hu, 2018; Qu, 2018). The four categories of integrity are the main areas of integrity education and the objectives for integrity management in Chinese higher education.

Many universities and colleges in China have launched independent units or designated specialist staff, to educate, prevent detect, and respond to integrity breaches (Guo, 2017; Zhou, 2019). Integrity, as one of the most important components of Chinese traditional values, has been emphasized in higher education policies and management practices (Chen, 2007; Liu, 2011). Compared to the myriad research on academic integrity education, individual and contextual factors related to students' integrity, little research has been conducted to explore the impact that university management has on students' integrity. This study aims to understand the Chinese college students' integrity status and answer the research question: what are the factors in relation to university management that influence students' integrity?

Theoretical framework

The definition of integrity

It is always a challenge to define integrity due to the large volume of qualities it can possibly encompass. In the context of higher education, academic integrity is an inseparable quality, which refers to the commitment to values of honesty, trust, fairness, respect, responsibility, and courage in learning, teaching, research, and community service (Moyo and Saidi, 2019). Academic integrity includes multiple constructs in terms of students' conduct in relation to university rules and procedures, such as academic misconduct. Academic misconduct, interchangeably, academic dishonesty, can be defined as fraudulent behavior involving some forms of academic deviance or deception whereby one's work is misrepresented (Kisamore et al., 2007; Eaton, 2017). Some examples of academic misconduct and academic dishonesty are cheating in exams, plagiarism, and inappropriate collaboration. Another related term to integrity is academic corruption, which usually refers to “misrepresenting one's educational background and work experience, plagiarism, distortion of research data, affixing one's name to someone else' publications, and making a false commercial advertisement, as well as other acts” (Yang, 2015).

In addition to academic integrity, the research on students' integrity is usually embodied in moral or ethics education, which is a critical part of Chinese higher education. According to Meindl et al. (2018), “moral” refers to “thoughts, desires, or actions that go against or suppress self-interest for the sake of promoting the interest of others; this could be the interest of individuals, groups, or collectives” (p. 4). Distinguished from the focus on wrongdoing, Reybold and Halx (2018) considered ethics as the enactment of integrity in everyday life where stakeholders within the university community intersect in multiple social and professional arenas. Integrity, in this sense, focuses more than wrongdoing. The findings of Wong et al.'s (2016) study suggested that some college students interpreted the notion of integrity beyond good academic conduct, such as “being honest with others,” “moral ethics,” and “professionalism.”

Integrity encompasses virtues of honesty, morality, and ethics, which implies a set of principles that involve a commitment to responsibilities to self and others (Wong et al., 2016; Reybold and Halx, 2018; Moyo and Saidi, 2019). Based on the specific definition and the interpretation, this study applied the four categories, academic integrity, relationship integrity, financial integrity, and employment integrity, to the understanding of Chinese college students' integrity.

Integrity education

Studies show that integrity education can have a positive impact on students' knowledge, perspectives, attitudes, and behaviors in terms of reducing breaches of integrity (Simola, 2017; Sefcik et al., 2020; Miron et al., 2021; Fudge et al., 2022). Integrity education is the attempt, usually referring to the educational programs intentionally designed, to facilitate students' moral development (Berkowitz, 2011; Meindl et al., 2018). Most education programs have a sole focus on academic integrity, but they vary dramatically across institutions, in terms of what to teach, when to deliver, how to assess, etc. Colleges and universities use academic integrity educational tutorials where faculty plays important roles in teaching and modeling desired conduct, and it is expected that the academic integrity literacies are embedded in the curriculum and pedagogy that is appropriate to the student's level of study (Miron et al., 2021; Fudge et al., 2022). Many other measures are taken in higher education, such as scaffolded authentic assessments culminated with interactive oral examinations, reliance on software checking for plagiarism, and usage of drama as a learning medium, to augment the development of students' integrity (Jagiello-Rusilowski, 2017; Kaktinš, 2019; Sotiriadou et al., 2020). Cam (2016) addressed that moral education should be distinguished from moral training in meeting academic standards in much the same way as other areas of study. Compared to the integrity education implemented in other countries and areas, Chinese colleges and universities conceptualize integrity education in university management and make it an important mandate for higher education institutions.

Although there is a positive correlation between the interventions and students' understanding of integrity, researchers argued that the effectiveness of integrity education programs tends to be limited (Meindl et al., 2018; Sefcik et al., 2020). The attention is paid to external elements of education instead of providing comprehensive information on values, or approaching education of moral consciousness, moral senses, and beliefs (Sefcik et al., 2020; Khashimova et al., 2021). While faculties realize and recognize the importance of integrity education, there are different perceptions of the roles that faculties take and there is a disparity between faculties' beliefs and practices, partially due to the lack of institutional support. Students may misperceive integrity when faculties fail to address the integrity issue proactively or institutions are perceived to have weak institutional policies (Eaton, 2017).

The role of higher education institutions

Higher education institutions need to create and maintain a culture of integrity that are integral to effective teaching, learning, research, and service (Wong et al., 2016). The faculties' and students' understanding of integrity requires an institutional level of clarification and support for maintaining the integrity and further the quality of higher education. “Providing clear and transparent guidelines in institutional policy enables stakeholders to understand their responsibilities and remain accountable for embedding a culture of integrity in their daily work” (Fudge et al., 2022). Similarly, avoiding the breaches of integrity that are likely to comprise the credibility requires “collaborative efforts and commitment from all stakeholders in higher education, namely, students, academics, non-academic and society as a whole” (Moyo and Saidi, 2019).

Researchers critique that higher education institutions nowadays have become a business that is functioning as an industry with economic goals and market-driven values (Kezar, 2004; Prisacariu and Shah, 2016). The changing environments and shifting professional expectations have created pressures for faculties and students to cut corners rather than operate with integrity (Chapman and Lindner, 2016). There is concern and debate about changes in the charter between higher education and society, which require policymakers and educational leaders to address higher education's role in the public good and to demand quality assurance around ethics and moral values (Kezar, 2004; McNay, 2007; Yang, 2015; Prisacariu and Shah, 2016). The demonstration that integrity is a priority within the community and that centralized and consistent processes are important for building a responsible culture of integrity (Hudd et al., 2009; Fudge et al., 2022).

Creating a healthy and supportive learning environment for both students and academics, and establishing institutional policies, require combined efforts from all stakeholders in higher education. When students have access to the knowledge of integrity and see that there is a commitment to integrity from all parties, integrity is more likely to be followed (Gottardello and Karabag, 2022). Besides the institutional level policymaking and environment building, higher education institutions could create and provide platforms, such as seminars and activities, for students to openly discuss issues of credibility and integrity and to exchange information with other students, faculties, and universities (Moyo and Saidi, 2019). This study aims to explore the relationship between students' integrity and policymaking, platform creation, and environment establishment given the fact that they are critical areas of university management.

Methods

This study applied the mixed-methods, combining quantitative and qualitative data analysis. Eighty-five higher education institutions (HEIs) located in the 34 cities of 14 provinces of Central and East China were selected via convenience sampling. Among the 85 universities, there are both 4-year research- and application-oriented universities (77.7%) and 3-year vocational colleges (22.3%). The majors offered at these HEIs include liberal arts, science, technology, engineering, and other areas that cover a wide range of disciplines.

An online questionnaire was adopted in this study. Since many Chinese colleges and universities have launched offices to work in the area of integrity, the respondents from the selected HEIs were the university or the school designated staff who were in the management position for students' integrity education. They were the faculties who were most familiar with students' integrity levels, students' needs, and issues of integrity. Three to five designated staff from each HEI were requested to participate in the study, and one respondent was accepted based on the verification of completeness and validity of their answers to the questionnaire, representing the HEI where the respondent worked. The instrument was designed and validated by the experts, based on the essential content and components of Chinese HEIs integrity education. The questionnaire comprised 33 questions, covering the topics of integrity policymaking, designated integrity office, integrity education, platform, portfolio, activities, role modeling, honor codes, penalties, sanctions, etc. These questions helped the researchers to understand the Chinese college students' integrity level from the management perspective and the university management practices.

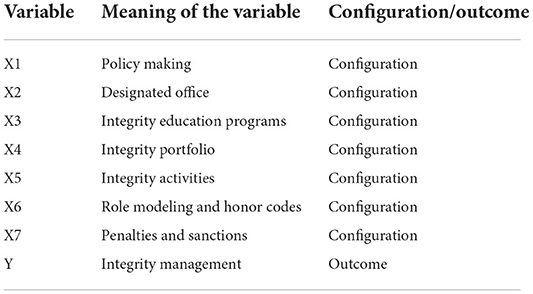

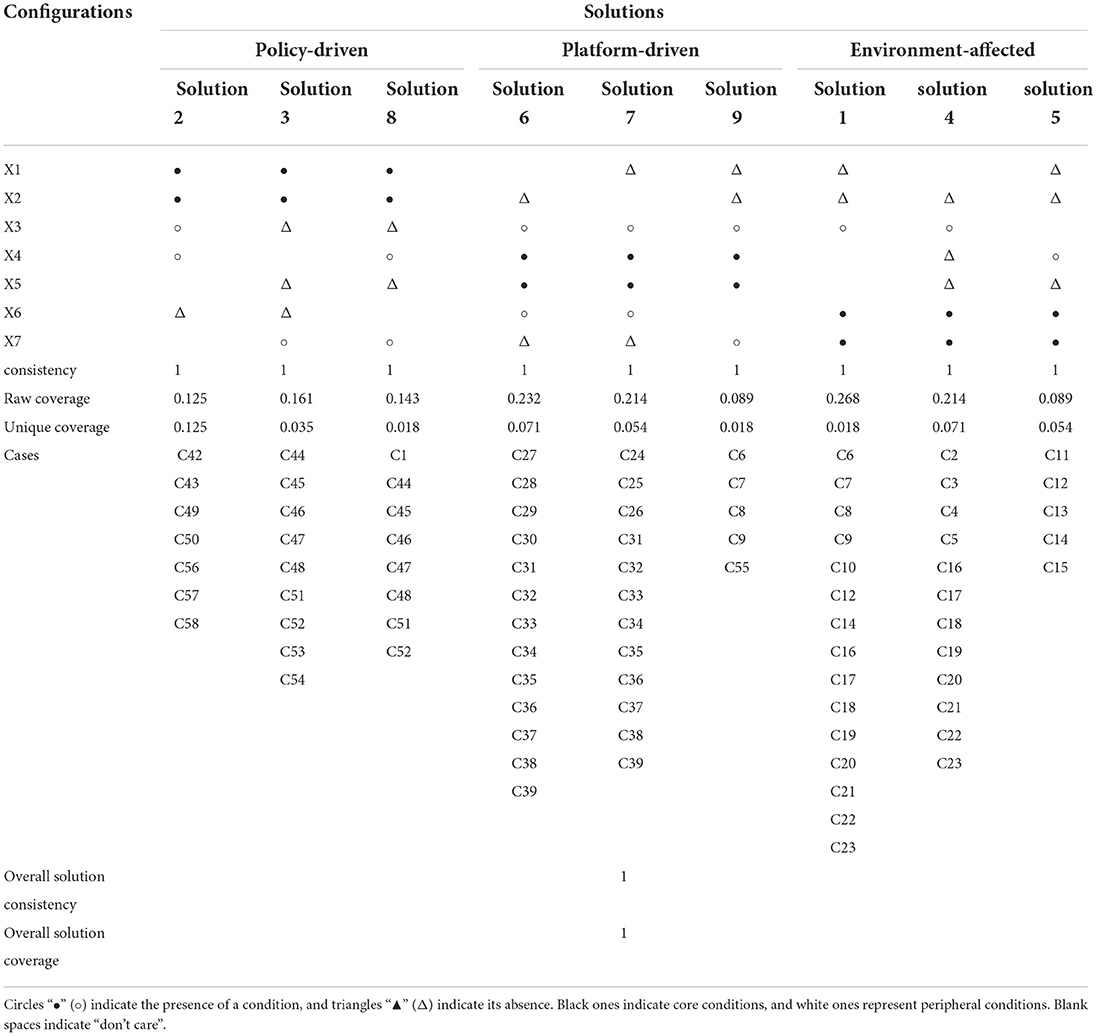

This study also adopted the Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) that was initiated by the American sociologist Professor Charles C. Ragin. QCA is “a set-theoretic configurational approach based on Boolean algebra…which conceptualizes causal relations as complex, that is, marked by conjunction, equifinality, and asymmetry” (Charles, 1987; Cilesiz and Greckhamer, 2020). In this work, the performance of university management of integrity was set as an outcome, while the seven main areas of integrity management—integrity policymaking, designated integrity office, integrity education and platform, integrity portfolio, activities, role modeling, honor codes, penalties, and sanctions were set as configuration (refer Table 1). It was expected that the students' integrity level and its influencing factors in relation to university management would be identified via the configuration analysis.

Data sources

Seventy-seven respondents were received with a return rate of 90.6%. Among the 77 respondents, 63 with completeness and validity to the questionnaire in academic integrity, relationship integrity, financial integrity, and employment integrity were accepted as representing their HEIs. Therefore, data of the 63 sample HEIs were collected and analyzed. The validity of the questionnaire is statistically significant (P < 0.05), and the internal consistency is high with an average Cronbach's Alpha above 0.6.

The outcome—the performance of university management of integrity—was compared among the 63 HEIs based on the questionnaire respondents. The critical value is taken after assigning “0” and “1” to the performance level. Similarly, the configuration—seven main areas of integrity management—was assigned “0” and “1” appropriate to the level. A true table was generated for the 63 HEIs' integrity configuration and outcome (refer to Table 2). Several categories were formed using the csQCA method, suggesting the solutions integrating various influencing factors to improve the performance of university management of students' integrity.

Results

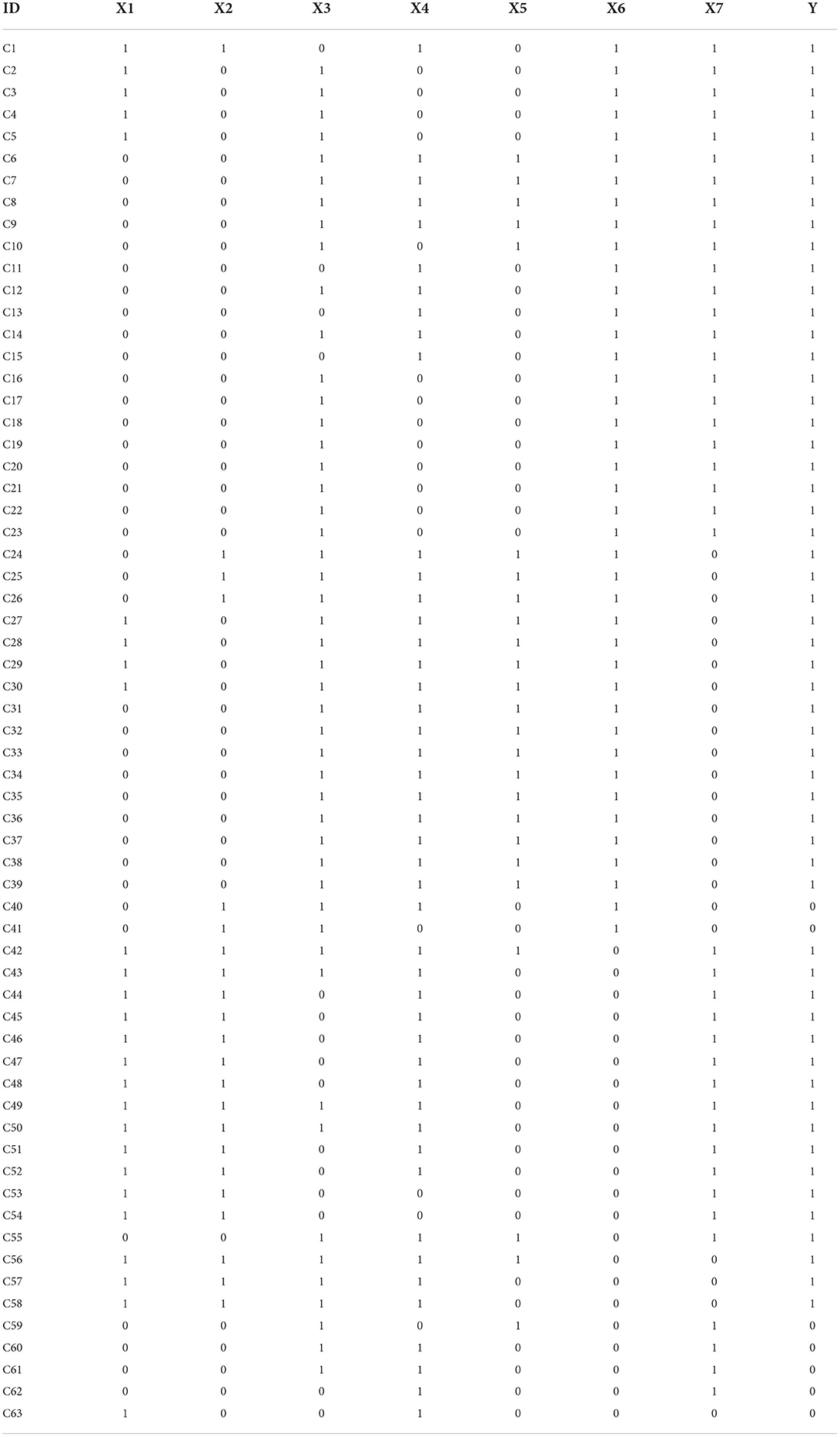

The results suggested that Chinese college students' integrity level was a little above average. In the questionnaire, integrity level was assigned with values from 1 to 5, from the lowest to the highest. The average values for four categories of integrity—academic integrity (Mean = 3.898), relationship integrity (Mean = 3.798), financial integrity (Mean = 4.063), and employment integrity (Mean = 4.036)—were between 3.7 and 4.1 (refer Figure 1). The financial and employment integrity was a little higher than academic and relationship integrity. Compared with what the literature described about students' integrity, the subjective evaluation of the university or the school designated staff appeared to be more positive. It was assumed that affiliation with the university might affect self-evaluation. The evaluation of the individual integrity category was close to the data found in the literature (Guo, 2017; Han, 2017; Hu, 2018; Qu, 2018), where the academic integrity level is relatively low and the relationship integrity level is the lowest but the most elusive, which should be paid more attention to.

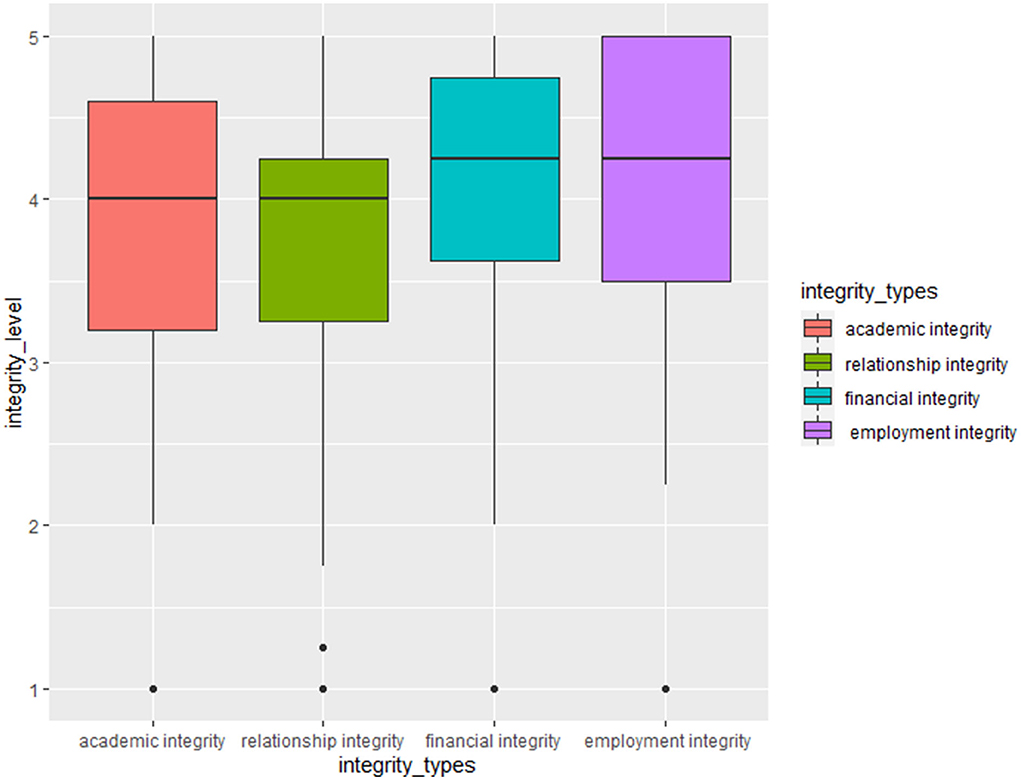

Nine solutions integrating various influencing factors to improve the performance of university management of students' integrity were obtained through csQCA analysis (refer to Table 3). Distinguished from the prior studies that focused on individual factors, the combination of influencing factors reflected the configuration interaction structure that supported the improvement of university management of integrity. For each solution, there are multiple combinations of core and assistant configurations, and some with non-core or non-assistant configurations. The solutions were put into categories based on the common and outstanding configurations. In particular, configurations X1 (policymaking) and X2 (designated office) were analyzed as core to Solutions 2, 3, and 8, which were inducted as policy-driven factors; Configurations X4 (integrity portfolio) and X5 (integrity activities) were the core to Solutions 6, 7, and 9, which implied the platform-driven factors; Configurations X6 (role modeling and honor codes) and X7 (penalties and sanctions) were the core to Solutions 1, 4 and 5, which suggested the environment-affected factors. Additionally, the result showed that the configuration X3 (integrity education programs), as the most important assistant configuration, impacted the majority of the solutions.

Discussion

Chinese higher education institutions have paid much attention to college students' integrity status and levels, which complies with the traditional value upheld in China's moral education. In addition to the academic integrity, relationship integrity, financial integrity, and employment integrity that are reflected in students' everyday life were also examined. From the university management perspective, it is worthwhile to rethink and attend to the broader definition of integrity and integrity education given the equal importance of the aforementioned categories in students' credibility and moral development beyond the classroom in the future. The students' breaches of integrity are a growing concern for HEIs because students' integrity matters for the morality, the quality, and the reputation of higher education. This study is significant in that it bridges the gap in the literature that overlooked the other aspects of integrity than academic integrity and suggests the interactions of factors in relation to university management that influences the students' integrity level.

The three comprehensive solutions that impact and potentially improve students' academic level are policymaking that is corresponding to students' needs, platform creation that is diversified and interest oriented, and environment establishment that positively affects students' understanding and practices of integrity. Underpinning the solutions is the valuing of integrity education, in specific.

First, Chinese HEIs integrity education is policy-driven. Many colleges and universities take the students' integrity as an indicator when determining student qualifications and eligibility for certain programs or positions. Policies, for instance, regarding scholarship application, students' leaders' code of conduct, advanced degree nomination, and employment references have made integrity an essential qualification, which guides the students to comply with the integrity expectations.

Second, the platform creation is addressed for students' integrity education. HEIs organize events and activities across the campus where integrity education is imprinted. The events and activities, such as the opening ceremony and graduate commencement, provide the opportunity for students to internalize their moral goals and motives. Other activities, such as debates, speech contests, and theaters, could bring the integrity topics up to an open discussion and exchange of ideas among students and faculties. Integrity portfolio, curriculum, and assessment are also important measures for students' integrity education, which assist students in understanding and preventing breaches of integrity. The positive intervention via the platform ensures an open, just, and effective evaluation of students' integrity.

Third, Chinese HEIs attend to the environmental establishment because they recognize that the situational context influences student behavior. On the one hand, the role modeling and honor codes are regarded as positive in inspiring student behavior aligned with that of the role models. The coherence of knowledge, cognition, and practice can be enhanced when the integrity behavior is recognized, appreciated, and appraised, especially with an actual reward of opportunities or other forms. On the other hand, the penalties and sanctions for the breaches of integrity present pressure and demonstrate disdain for unethical behaviors.

Last but not the least, there are still issues and limitations in integrity education at Chinese higher education institutions. The inconsistency in institutional level policy and policy implementation has allowed the students to think and act less seriously on integrity. The integrity is written in the institutional policy for rewarding opportunities, while the consequences of the breaches of integrity are relatively vague and simplified. When breaches happen, the primary penalty is usually slight and in the form of consultation. The consultation may work for certain scenarios, but it may also have possible damage to the integrity in the long term because the students may misinterpret the standard and consequences that mismatched to their unethical behaviors. It is suggested that the Chinese HEIs could build a mechanism that is conducted transparently and consistently in dealing with the consequences of breaches of integrity.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

XL claims the first authorship for initiating the research, designing the study, and collecting and analyzing the data. JZ claims the second authorship for framing the theoretical perspectives and research questions, assisting in data analysis, and translating the full manual script. WY claims the third authorship for reviewing, proofreading, and advising for the work. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was funded by China's National Office for Education Sciences Planning, under the project the study of quality assurance system construction of humanity and social sciences programs in Chinese higher education. The award number is DIA210351.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Berkowitz, M. W. (2011). What works in values education. Int. J. Educ. Res. 50, 153–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2011.07.003

Cam, P. (2016). A philosophical approach to moral education. J. Philos. Schools 3, 5–15. doi: 10.21913/JPS.v3i1.1297

Chapman, D. W., and Lindner, S. (2016). Degrees of integrity: the threat of corruption in higher education. Stu. Higher Educ. 41, 247–268. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2014.927854

Charles, R. (1987). The Comparative Method: Moving beyond Qualitative and Quantitative Strategies. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Chen, J. (2007). The Psychological Construction and Characteristics of the Integrity of Chinese People. CNKI. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CDFD&dbname=CDFD9908&filename=2007131039.nh&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=Jz9YzT9EGMPLI0EYeEm8EWiNUdRJ-of6DfNxRykWVNntG2RQy67Lz-KFgKvDHWef

Cilesiz, S., and Greckhamer, T. (2020). Qualitative comparative analysis in education research: its current status and future potential. Rev. Res. Educ. 44, 332–369. doi: 10.3102/0091732X20907347

Eaton, S. E. (2017). Comparative analysis of institutional policy definitions of plagiarism: a pan-canadian university study. Interchange 48, 271–281. doi: 10.1007/s10780-017-9300-7

Fudge, A., Ulpen, T., Bilic, S., Picard, M., and Carter, C. (2022). Does an educative approach work? A reflective case study of how two Australian higher education Enabling programs support students and staff uphold a responsible culture of academic integrity. Int. J. Educ. Int. 18, 1–20. doi: 10.1007/s40979-021-00099-1

Gottardello, D., and Karabag, S. F. (2022). Ideal and actual roles of university professors in academic integrity management: a comparative study. Stu. Higher Educ. 47, 526–544. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2020.1767051

Guo, A. (2017). Research on College Students' Integrity. CNKI. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CDFD&dbname=CDFDLAST2018&filename=1017076637.nh&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=DeopUJKEh782eXbu4U6VOHHrC1drXuYMDYra1BZHJ2xGigb1OK-8nl8Fkk0KsT

Han, X. (2017). Research on Chinese College Students' Integrity Education in the New Era. CNKI. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CMFD&dbname=CMFD201801&filename=1017860242.nh&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=5aIY6ejvt_A0BiACS78aqwOuE5lgF71xEMWGVyrY3bVEZxqMkpD3Fk6FHZVCnRWl

Hu, X. (2018). Research on College Students' Integrity and the Constructs. CNKI. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CDFD&dbname=CDFDLAST2019&filename=1019858098.nh&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=8-mYyoJ-iKjfyZWqteg-YNiD1PdxYptEGVc5nzFI5mEGlBIJ7UXVjwK10O3-poMo

Hudd, S. S., Apgar, C., Bronson, E. F., and Lee, R. G. (2009). Creating a campus culture of integrity: comparing the perspectives of full-and part-time faculty. J. Higher Educ. 80, 146–177. doi: 10.1080/00221546.2009.11772137

Jagiello-Rusilowski, A. (2017). Drama for developing integrity in higher education. Palgrave Commun. 3, 1–9. doi: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.29

Kaktinš, L. (2019). Does Turnitin support the development of international students' academic integrity? Ethics Educ. 14, 430–448. doi: 10.1080/17449642.2019.1660946

Kezar, A. J. (2004). Obtaining integrity? Reviewing and examining the charter between higher education and society. Rev. Higher Educ. 27, 429–459. doi: 10.1353/rhe.2004.0013

Khashimova, M. K., Mustafoeva, D. A., Kamilova, M. O., Saydullaev, A. N., and Mamazhanov, I. G. (2021). Integrated approach to moral education. Psychol. Edu. J. 58, 2885–2889. doi: 10.17762/pae.v58i1.1182

Kisamore, J. L., Stone, T. H., and Jawahar, I. M. (2007). Academic integrity: the relationship between individual and situational factors on misconduct contemplations. J. Bus. Ethics 75, 381–394. doi: 10.1007/s10551-006-9260-9

Liu, W. (2011). The Formation of Cohesion in Beliefs, Knowledge, and Practice and the Educational Intervention. CNKI. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CDFD&dbname=CDFD1214&filename=1011152665.nh&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=lHY12IspKsjL6yLcwcZBzyoLkeybUsn1O7WhaCm9CvWckGeHB74pLG8A_tDt4SOR

Macfarlane, B., Zhang, J., and Pun, A. (2014). Academic integrity: a review of the literature. Stu. Higher Educ. 39, 339–358. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2012.709495

McNay, I. (2007). Values, principles and integrity: academic and professional standards in higher education. Higher Educ. Manage. Policy 19, 1–24. doi: 10.1787/hemp-v19-art17-en

Meindl, P., Quirk, A., and Graham, J. (2018). Best practices for school-based moral education. Policy Insights Behav. Brain Sci. 5, 3–10. doi: 10.1177/2372732217747087

Miron, J., Eaton, S. E., McBreairty, L., and Baig, H. (2021). Academic integrity education across the Canadian higher education landscape. J. Acad. Ethics 19, 441–454. doi: 10.1007/s10805-021-09412-6

Moyo, C. S., and Saidi, A. (2019). The snowball effects of practices that compromise the credibility and integrity of higher education. South Afr. J. Higher Educ. 33, 249–263. doi: 10.20853/33-5-3574

Prisacariu, A., and Shah, M. (2016). Defining the quality of higher education around ethics and moral values. Q. Higher Educ. 22, 152–166. doi: 10.1080/13538322.2016.1201931

Qu, J. (2018). Research on the Current Status of Student Loans in Chinese Higher Education Institutions and the Corresponding Policies. CNKI. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CMFD&dbname=CMFD201901&filename=1018860006.nh&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=UxDahPVvOCrRIyis4aHakVNZNOb6QXkMjR3KRW0cZ-j6GlAC6VrwpVjT3Q0K951G

Reybold, L. E., and Halx, M. D. (2018). Staging professional ethics in higher education: a dramaturgical analysis of “doing the right thing” in student affairs. Innov. Higher Educ. 43, 273–283. doi: 10.1007/s10755-018-9427-1

Sefcik, L., Striepe, M., and Yorke, J. (2020). Mapping the landscape of academic integrity education programs: what approaches are effective? Assess. Eval. Higher Educ. 45, 30–43. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2019.1604942

Simola, S. (2017). Managing for academic integrity in higher education: insights from behavioral ethics. Scholarship Teach. Learn. Psychol. 3, 43–57. doi: 10.1037/stl0000076

Sotiriadou, P., Logan, D., Daly, A., and Guest, R. (2020). The role of authentic assessment to preserve academic integrity and promote skill development and employability. Stu. Higher Educ. 45, 2132–2148. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2019.1582015

Wong, S. S. H., Lim, S. W. H., and Quinlan, K. M. (2016). Integrity in and beyond contemporary higher education: what does it mean to university students? Front. Psychol. 7, 1094–1094. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01094

Yang, R. (2015). Corruption in China's higher education: a malignant tumor. Int. Higher Educ. 39, 18–20. doi: 10.6017/ihe.2005.39.7473

Zhou, D. (2019). Research on Integrity Mechanism in Higher Education Institutions. CNKI. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CMFD&dbname=CMFD202002&filename=1020020967.nh&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=0pheX8quueSceRFtA3SjU9rAFkaX-HtZbvEjw1ZA4XsJ431COkATw52nO7YwFiH_

Keywords: integrity, college students, university management, system construction, China

Citation: Li X, Zhao J and Yan W (2022) Integrity levels of Chinese college students: An analysis of influencing factors. Front. Educ. 7:843674. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.843674

Received: 26 December 2021; Accepted: 06 July 2022;

Published: 11 August 2022.

Edited by:

John Ziegler, Pennsylvania Western University (Formerly Edinboro University), United StatesReviewed by:

Nadia Parsazadeh, National Dong Hwa University, TaiwanValentine Joseph Owan, University of Calabar, Nigeria

Copyright © 2022 Li, Zhao and Yan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jin Zhao, amluLnpoYW9AeGp0bHUuZWR1LmNu

Xiaohong Li

Xiaohong Li Jin Zhao

Jin Zhao Wenfan Yan

Wenfan Yan