- Faculty of Humanities and Teacher Education, Volda University College, Volda, Norway

This article examines the at-school opportunities Norwegian high schools provide for involving migrant parents in their children’s education. The legal and societal expectations of systematic school-home cooperation with all parents at this time of transition to higher education or employment are relatively new in Norway. Thus, how schools act on these expectations as they meet migrant parents is under-researched. To address this gap, interviews with four leaders of three high schools with different sociocultural profiles and observations of meetings with parents at one of the schools were conducted as a part of this study. Examined through a Bourdieusian lens, parental involvement—or rather traditional lack of at-school parental involvement outside crises—can be interpreted as a form of high-school doxa. This unquestionable truth is now challenged as more rights are granted to parents, and new heterodox beliefs and discourses about parents of adolescents at school emerge. At the same time, the schools in the focus of this study appear to have limited room for imagining forms and content of non-crisis communication with the home, especially when parents do not directly claim their rights, as is true for many migrant families. This study thus contributes to the existing research on parental involvement and home-school relations by emphasizing the need for a professional discussion on more equitable and better situated forms of engaging parents, as well as the school’s areas of responsibility in including families in educational communities.

Introduction

Educators, researchers, and policymakers argue that, just like parents of younger children, parents of adolescents and young adults (those aged 16-19) have a strong potential for cooperating with their school to support the performance and well-being of students (Wang and Sheikh-Khalil, 2014; Vedeler, 2021). At the transition from high school (upper-secondary education) to higher education or career, students come to terms with the tensions between their developing individual autonomy and more pronounced expectations regarding their choices from both family and culture (Kryger, 2012; Ball et al., 2013). For students with migrant parents, this transition takes place in the context of negotiating multiple identities and belongings affected by race, religion, and language. Therefore, teachers need to reckon with the changes in the students’ life and use other strategies for relating to families than in lower grades (Hill et al., 2004; Deslandes and Barma, 2016). They should thus include all families in the dialogue and support around their children’s general well-being, schooling, and higher education and career plans as a part of the educational community (Epstein, 2008). This idealized representation of a democratic partnership is, however, criticized for being based on assumptions of homogeneity of families’ experiences and positioning with the school (Vincent, 2000). Parents with migrant experiences are a heterogeneous group and are defined for the purpose of the present study as parents or guardians who have moved to Norway as adults with experience of migration and studying in a different school system. Antony-Newman’s (2018) meta-synthesis confirms that migrant parents have different stories, distinctive educational expectations, and unique struggles that are often made invisible to the school. Studies looking at how schools meet migrant parents make an important contribution to the discussion on parents and power in education, exploring the differences the families’ sociocultural background make in terms of how confident and successful or compliant the parents are in approaching the schools and interpreting their codes (Crozier and Davies, 2007; Vincent, 2017; Pananaki, 2021). The significance of teachers’ perception of the role parents should play in their children’s education and efforts made by school leadership to make schools more friendly for all parents, as reflected in school practices, have been highlighted as particularly significant for ensuring equitable parental involvement (Kim, 2009; Rissanen, 2019).

At the transition to higher education and career, family migration experiences have been shown to play a significant role in student choices, strategies, and exploration of their identities. Most of the strategies adopted by migrant parents are pursued at home through high aspirations and the use of ethnic networks (Reay et al., 2001; Kindt, 2018). At the same time, there is a dearth of literature on the role high schools play in their encounters with migrant families. At-school parental involvement that is the focus of this paper is here broadly conceptualized as interactions between schools and students’ parents or guardians. The practices that high schools initiate, based on Epstein’s model, may take the form of organizing school meetings and activities, communicating with parents, and inviting them to volunteer at school and participate in school decision-making (Epstein et al., 2019). A case study involving two U.S. schools conducted by Villavicencio et al. (2021) adds several new age-appropriate contextualized forms of at-school parental involvement. These include mediating between families and students in conflict situations, being open for unplanned conversations, making home visits, and building legal, educational, and emotional support networks for migrant parents. Still, extant research consistently shows that schools are less likely to reach out to parents as their children reach higher grades and mostly do so when there are problems with performance (Seitsinger, 2019). At the upper-secondary level, there is little evidence for schools adopting practices associated with Foucault’s (1991) governmentality, where the teachers interfere in their students’ home culture in an effort to adjust the socialization process according to the non-migrant middle-class norms (e.g., Vandenbroeck and Bie, 2006; Bendixsen and Danielsen, 2020). In Norway, Vedeler’s (2021) recent study involving focus groups with teachers and school leaders shows that where school policy is not clear and deliberate, some high school teachers may choose to have less contact with parents, citing safeguarding the boundaries of student autonomy as their “natural” motivation. Older students may resist parental involvement in forms they see as inappropriate, and the parents, lacking school and community guidance, may retract in response rather than adapt the balance between autonomy and connection (Hoover-Dempsey et al., 2009; Deslandes and Barma, 2016; Jónsdóttir et al., 2017).

By focusing on the practices Norwegian high schools adopt for involving their students’ parents, this paper contributes to the broader research on the schools’ role in shaping the dispositions of students with migrant parents at the transition to higher education or career. I examine how three schools enact their role to create opportunities for parental involvement through their home-school encounters. Specifically, I look at how the practice was organized and what matters were discussed during the families’ encounters with these schools. In the following section, I present the theoretical tools adopted for this analysis that include Bourdieu’s concepts of doxa and field that help expose the mechanisms of the field of high school education and its traditional ways of imagining and doing at-school parental involvement.

Doxa and field change in at-school parental involvement

Bourdieu’s theory is often applied to question the school endeavors purported to be beneficial to all students. Bourdieusian analysis has contributed to the exposition of mechanisms of inequality in expansion of higher education, promotion of free school choice, or increasing parental access and representation (see, for example, Bourdieu, 1999; Holme, 2002; Pananaki, 2021). Following in this tradition, in this work, I use the concepts of field, doxa, capital, and habitus to examine how family backgrounds interact with schools’ social and cultural contexts. The relationship between the school and the home can be described as a struggle for recognition of various forms of capital (Bourdieu, 1984). In this struggle, the acquisition and engagement of different forms and amounts of capital depend on the students’ or their parents’ habitus. Habitus is the individual’s embodied history, including family socialization and early school experience, which manifests itself in the present in the form of behaviors, preferences, and perceptions deeply involved in choice and interpretation of present experiences. A field that the habitus matches is structured so that making choices comes naturally as “procedures to follow, paths to take” with the instruments and institutions set in place for the individual’s competent practice (Bourdieu, 1990, p. 53). An established institution will thus tend to have members with homogeneous habitus that seamlessly fit into their surroundings without the need for coercion or direct reference to rules. The institution will then function in “conductorless orchestration,” as the prevailing harmony does not require conscious guidance and can reproduce itself (Bourdieu, 1990, p. 59). Thus, at some high schools, staff and students would share history, language, social codes and a “common sense” regarding the manner and degree of parental involvement at schools and at home. Other schools would have evolved during a shorter time and thus resort more to coercion, not expecting students or parents to understand the implicit ways of the school’s practice. More recently developed theories of community cultural wealth and ethnic capital challenge deterministic interpretations of Bourdieu to insist that schools can change and develop appreciation for the capital students coming from non-majority homes possess (see for example Modood, 2004; Yosso, 2005).

Bourdieu highlights the role of the field’s doxa—“a set of inseparably cognitive and evaluative presuppositions” most people in a social field take for granted—in constructing the education system’s practices (Bourdieu, 2000). Those caught up in the field’s game would commonly comply with the doxa, including its imposed sense of limits of what is doable and not doable. Competing beliefs, however, can arise, as in the case of the emergence of more active parental involvement at high school. These changes may stem from the influence of the metafield, that is the field of power where the interests of business, cultural, and intellectual elites of the modern societies clash (Bourdieu, 1996; Lingard et al., 2005). However, in a field, any new discourse can only be mediated by recognized parties (Deer, 2008). This means that, although dominant beliefs can be challenged and changed, the power structures in the field would largely remain the same (Bourdieu, 2000). The middle-class parents—possessing the cultural, social, and economic capital appreciated by the school—are thus best positioned to shape the school field to their advantage (Reay, 1998; Lareau, 2011). Still, parents’ ethnic background, migration experience, and different combinations of capital (cultural vs. business middle-class) the families possess also affect how they operate at school. Middle-class families that have migrated to their host country may also experience difficulties in translating their high cultural or economic capital into that of the local schools, even though some gradually become more familiar with the local system through acquisition of social capital and additional education (Lareau and Horvat, 1999; Antony-Newman, 2020).

Norwegian high school context

High school is the first formal point of student selection in Norway, as admittance to the different tracks is based on grade point average. All students who have completed primary and lower secondary education are entitled to high school (upper secondary) education and nearly all (98%) enroll. However, not all students can apply to all tracks, as some tracks qualify students for higher education, others result in vocational certificates, and some combine both. The choice of track and subsequent choice of subjects and subject levels are presented as the young person’s independent decision (Hegna and Smette, 2017). In addition to tracking coming late in the schooling process, the understanding of independent and equal choice is reinforced by the absence of university fees and the availability of low-rate loans to support housing and living costs for those pursuing higher education. Vocational tracks are advertised as equally appropriate for all students due to the availability of relatively stable and well-paid vocational career paths. In practice, however, the vocational labor market and apprenticeships are less open for students with migration backgrounds, especially refugees (Jørgensen, 2018). In Norway, there is generally a close relationship between family background and educational and career choices, as students tend to enter occupational domains similar to those of their parents (Helland and Wiborg, 2019).

Since 2006, Norwegian high schools have been bound by law to organize regular general parent meetings (assemblies) and parent conferences, report on student academic progress, and send out warning letters if that progress or attendance may be insufficient for graduation (Norway Ministry of Education and Research, 2006). Unlike compulsory schools, high schools are not expected to involve parents in the decision-making through participation in school boards. Maintaining “ongoing contact” with all parents, irrespective of whether the student is seen as experiencing problems, is required and this responsibility is assigned to a contact teacher, even though the specifics of what ongoing contact means are not provided. This vagueness in the regulation may have a variable effect on the roles of parents depending on their backgrounds. Bæck (2017) argues that the new government policies endorsing parental involvement at school in practice encourage more involvement from middle-class parents, which may eventually increase rather than moderate social differences. This concern echoes Crozier’s (2001) earlier warning that treating all the parents equally without recognizing their ethnic diversity may contribute to “widening the gap between the involved and the uninvolved” (p. 338).

In Norway, a contact teacher has similar function to that of homeroom teachers in the U.S. school and form tutors in the UK. While teaching regular subjects, the contact teachers are responsible for attending to their students’ administrative issues, organizing special events, participating in teams formed to support students with special needs or in special circumstances, and keeping in contact with the home. In lower grades and some tracks in high school (sports, dance, and recently some specialized science tracks), the same teacher can follow the class over 2 or 3 years. In the teachers’ nationwide collective labor agreement (binding for all schools), one to two school hours per week are allocated to this function. This agreement that concerns teachers’ pay and working conditions has been recently renegotiated by the trade unions that have a strong influence in Norway. After teachers repeatedly complained of the increasing workload related to out-of-classroom assignments, extra time was included to cover contact teacher assignments. The time was doubled for classes with over 20 students in primary and middle school, but not in high school. As a result, high school teachers have received an extra 15 min of paid working hours per week per student (Bjurstrøm, 2022). This debate around legal distribution of work hours shows that many teachers view their student care responsibilities outside the classroom as a significant burden. The difference in hours allocated between school levels may indicate that the contact teacher role is valued less or is seen as less of a drain on teacher resources in high school. Against this backdrop, the aim of the present study was to examine the high schools’ role in encouraging parents to engage in the education of their children. As this is a relatively new topic, a contextualized exploratory multiple-case study was conducted, as described in the next section.

Materials and methods

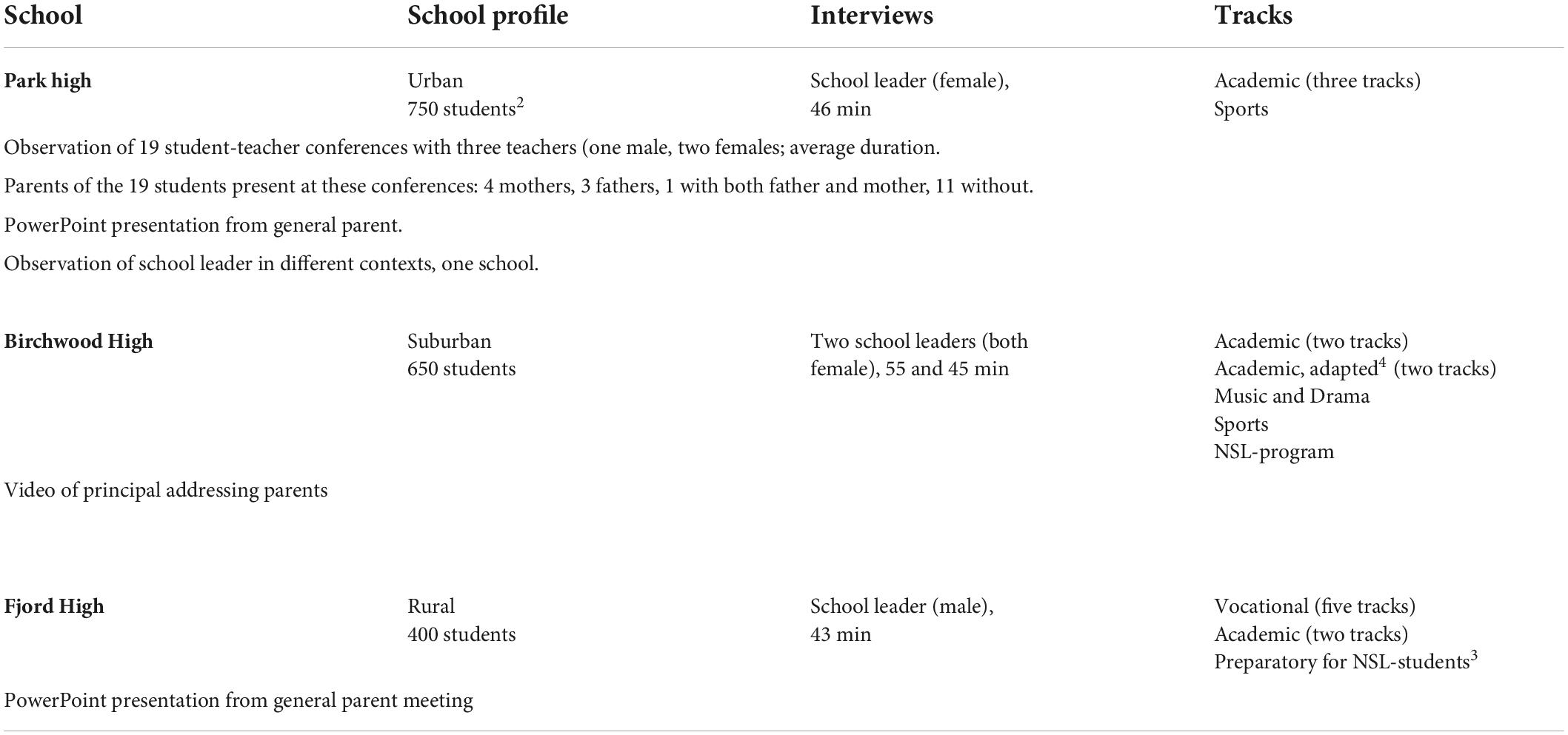

This paper draws upon the material gathered during a 3-year multiple-case study of three Norwegian senior high schools—one urban (Park High1), one rural (Fjord High), and one suburban (Birchwood High). High schools in Norway often specialize in either vocational or academic programs. Following maximum variation case selection strategy to provide rich complexity to the collected data (Flyvbjerg, 2006), I chose schools with different tracks and social histories to explore a breadth of approaches for involving migrant parents these schools adopted. I approached these specific schools as local teacher education programs indicated that they actively worked to involve migrant parents.

The schools: Contextual details

The urban Park High1 has a large population of students whose parents or grandparents have migrated to Norway, many from Southeast Asia, but also some students that have recently arrived from the Balkans, Middle East, and Eastern Europe. The assistant rector estimated the share of students with migrant backgrounds in the general academic tracks at 80%.2 Park specializes in academic programs and professional sports tracks but has also previously offered art programs. The school is open in the evenings for free tutoring (Homework Club), exam help, and access to training facilities. After the initial interviews, Park High became my main research site, as this school offered the level of access required for studying their school-home practices in more depth (see Table 1 for an overview of the data collected at the three schools that was used in this article).

Birchwood High hosts highly competitive academic tracks and is located in a suburb where some parents work in the city, some at large local construction projects, and a few are involved in agriculture. Polish, Kurdish, Urdu, and Dari are the most commonly spoken home languages by students with migrant parents at Birchwood. The school hosts both an induction program with Norwegian as a second language (NSL) for recently arrived migrant students and two adapted tracks that admit 30 migrant students who intend to continue into higher education.3

Fjord High is a rural school that hosts two academic tracks and five vocational tracks with further specialization, which are popular among local students. Students arrive from local fishing and agricultural villages and from the town located about an hour’s bus ride away. Both refugee students attending the local induction program and those already studying in the main tracks come to Fjord on this bus. Other youth travel to the town where the school offers a wider choice of academic, sports, and arts tracks. At the time of this study, approximately 25 students were receiving extra tuition in Norwegian while attending regular classes,4 many of whom were refugees and most were unaccompanied minors.

Exploratory multiple-case study methodology

The present study builds on interviews and observation notes selected from data gathered during a larger multiple-case study. Multiple data sources were brought together to provide deeper understanding of high school encounters with migrant parents in different contexts seen from different perspectives (Stake, 2006; Thomas, 2016). First, I present data from my semi-structured interviews (Rapley, 2012), lasting on average 45 min, with four school leaders—two principals, one assistant principal, and one department leader (see Table 1 for the details). I have asked them how the school-home cooperation was organized at their schools, what they expected of their students’ parents, and whether and in what way the parents were different. As all school leaders had teaching backgrounds and long experience (over 20 years on average), we also discussed school histories and the types of students and parents they had encountered over time, both migrant and non-migrant.

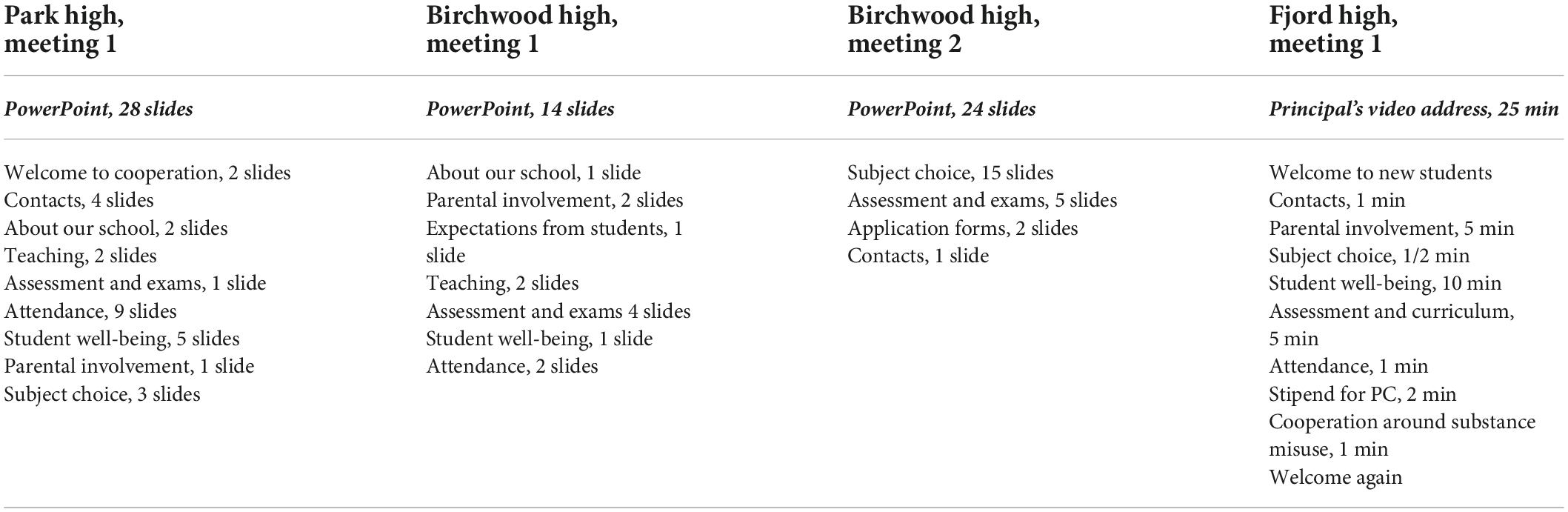

The current paper also builds on my observations of contact with parents at the main study site, Park High. I have analyzed notes of 19 teacher-student conferences (nine of which involved parents), as well as of my informal observations of the work of a school leader with special responsibility for parent contact—at her office, in the school corridors, in the school library and at the teachers’ quarters) —and the documents she provided. Due to COVID-19 travel restrictions and rescheduling of meetings, no observations at parent general meetings and evenings were possible. Instead, I used presentations made by the principals at these or pre-COVID meetings, two of which were available in PowerPoint format and one was a video file that Fjord shared with me. Other resources from the case study, including teacher, student, and parent interviews and other online and printed material representing the schools, provided background information. All text was transcribed and coded in the original Norwegian or my first language, with some elements of oral speech remaining. The citations used in this paper were translated and edited into more standard written English to better safeguard the informants’ identities.

The required ethics clearance from the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD) was granted for this project. Due to the restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, 15 of 19 of teacher-student conferences I observed were conducted online. Upon a discussion with the contact teachers and the ethics advisor from the NSD about maintaining student confidentiality and well-being, a conclusion was reached that video recording was inadvisable, as it could interfere with what the students and families would be willing to share in these conversations. The participants were informed that my role as an observer was limited to witnessing the school practices, rather than focusing on individual students. They were further advised that they could choose not to have me present in these meetings, and one did. Although I have not discussed individual students with the school leaders, some of the excerpts that might have unintentionally divulged identifying information had to be omitted from the school descriptions to avoid breaches of anonymity.

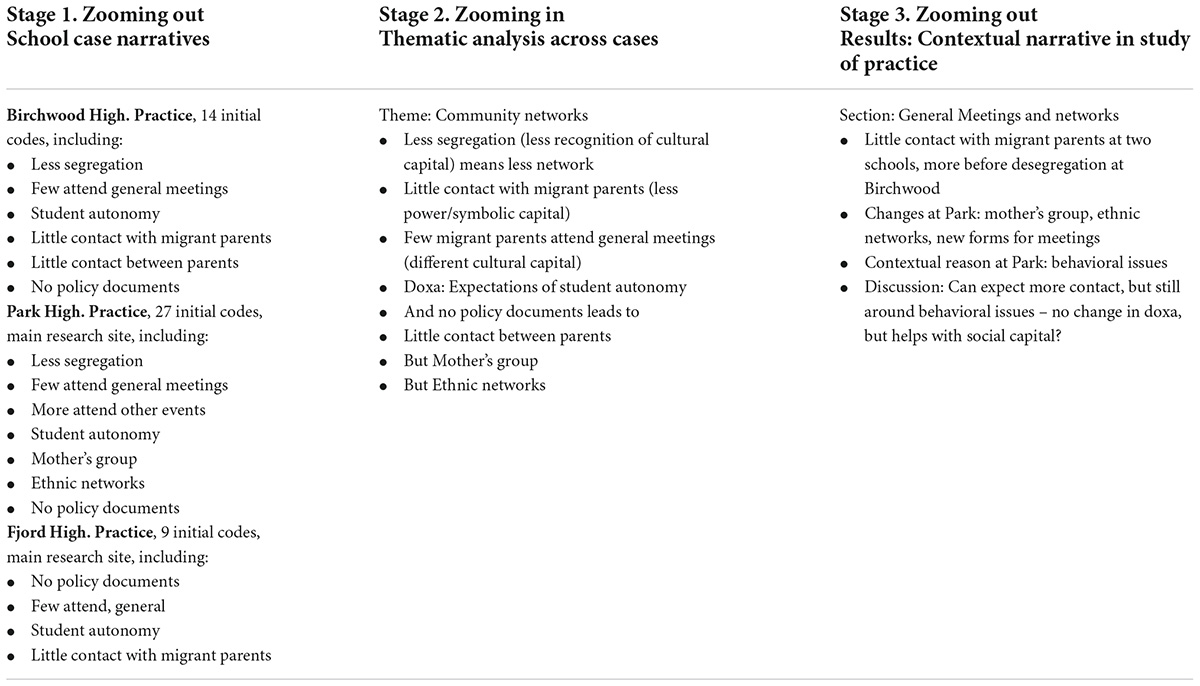

The analysis conducted as a part of my larger study involved a combination of intuitive processing and some elements of formal inductive coding (Simons, 2009). Interview and video transcripts, observation notes, and presentations were organized in NVivo software. The material was first used to construct narratives of school and individual leader cases. Shortened and anonymized versions of these initial school narratives (2–3 pages long) are used in the section “The schools: contextual details” and provide context for the discussion section. In the second stage of my analysis, the material from all data sources, including observation material from Park High, was coded inductively inside each of the cases. It is here that the practices schools adopted to involve parents, rather than what the research informants thought about their experiences with parents, came into focus. My final analysis conducted for this article was performed across the cases to identify a variety of common themes connected to school practices while defocusing in order to increase the study’s validity by being sensitive to the specific school and community contexts (Stake, 2006; Simons, 2009). The categories that emerged included General meetings, Crisis communication (at one-on-one and class level), Community networks, Concern for student autonomy and safety, Time and other resources, and Choices and assessment. Change was a theme that originated from the individual case narratives and permeated all categories. The interpretation of data in this study was not linear (Rule and John, 2015), but a simplified example describing the steps in the analysis process for theme Community networks is provided in Table 2. I take up the themes that emerged in the analysis in the next section to answer the research questions of how practice of involving parents at school was organized and what matters were discussed with or presented to the parents. Given the differences in the school contexts and available data, no systematic comparison was attempted. This strategy also aligns with the main objective of this article—establishing how difference was constructed in schools’ practices rather than examining discourses about parents and experiences with them. This focus was born out of my engagement with Bourdieu’s theory and previous research, as well as my interest in the schools’ enactment of the new regulation on involving parents at the high school level which had been in force in Norway since 2006. However, none of my informants remembered that change, so other elements of school governance became more central to the analysis, such as the collective labor agreements.

Results: School efforts to involve parents in children’s education, old practices, and change

At all three schools at which my study was conducted, the leaders agreed that parents were important for the students’ well-being and performance, including positive and negative influences. They particularly appreciated the subtler at-home forms of encouragement and care. Indicating the changes in the field of schooling, the leaders acknowledged that the old, for some nostalgic, days of academic gymnasium schools predating the reforms of the 1990s were relegated to history. The teacher could no longer go into the classroom, shut the door, teach the subject, and then go straight home to prepare the next day’s lectures alone. Cooperation was now widely expected not only with other teachers, but also with other professionals (including various specialized counselors, nurses, and psychologists) and social agencies, and with parents. In the words of the leader from Park High, “The autonomous teacher is gone.” Another important change that all three school leaders referred to was that, in the current system, the students have much greater legal rights in terms of the school’s responsibility for providing an environment free from bullying and generally supporting their well-being and learning. Birchwood and Fjord in particular have experienced that parents and students would accordingly refer to the new Section 9A-4 of the Education Act (Norway Ministry of Education and Research, 1998) that came into force in 2017, enforcing the students’ right to experience a “good physical and psycho-social environment.” This section, rather than changes to home-school cooperation regulations, came to mind of my informants when I talked about the changes in the legal framework of their work with parents. Still, the strategies, policies, and the amount of effort the schools and individual teachers invested in their encounters with parents varied across schools and teachers, as well as among what they recognized as different groups of parents. I now present forms of at-school involvement practices, general and one-on-one, before turning to matters discussed with parents at the three schools.

Forms of involving parents at school: How practice was organized

Generally, I found that contact with migrant parents did not constitute a significant part of the teachers’ job, with the exception of a few students that required special attention (due to being in some sort of difficulty or crisis) and some work related to testing and formal notices about attendance and grades. The framework of the collective labor agreement with approximately 2 h per week allocated for contact teacher work was mentioned by leaders at both Fjord and Birchwood when discussing this topic. There were no other local policy or strategy documents concerning parental involvement at the schools, and only Fjord had a section of its website dedicated to parents. The teachers and leaders at Birchwood and Fjord struggled to recruit migrant parents for my study, admitting that they had limited contact with student families, or had contact with parents who would not feel comfortable talking about rather difficult situations that required their involvement at school.

General meetings and community networks

Based on my interviews with school leaders and observations at schools, with the exception of critical situations, the expectations from all three schools in terms of at-school participation by parents were confined mainly to attendance at two to four general meetings during the first 2 of the 3 years of high school. The first general parent assembly soon after the start of the first school year was seen as particularly important. Still, all general meetings were held outside work hours to facilitate attendance and were considered the central arena for establishing and maintaining contact. There was, however, a marked difference in attendance between groups of parents and the efforts to invite parents varied from teacher to teacher. Having general parent meetings at the high-school level, although not legally required prior to 2006, was not new at any of the three schools, were this practice dates back to the 1990s and 1980s. In the past, at times of large refugee crises, Birchwood organized separate general meetings for parents with specific refugee backgrounds and invited interpreters. However, as the number of languages the parents could speak increased over time, having too many interpreters was deemed impractical as it would disrupt the meetings. The school leaders noted that there has also been less segregation of migrant students over the years. This means that schools now have fewer classes where all or most students are migrants or where no students have migrant backgrounds, reducing their visibility as a group and efforts made at including parents from specific ethnic groups. Judging by PowerPoint presentations and the video I received from the schools, these general meetings were now organized in a traditional format where the principal and some leaders welcomed the families and introduced themselves and the school, after which families moved to individual classrooms where contact teachers made their presentations followed by a few questions from the parents. The second general meeting was often reserved for discussions with subject teachers and was popular with the more involved parents at Park and Birchwood. Career guidance counselors were also available for the parents and students to ask questions at the end of these meetings.

For a few years, the urban Park High has been testing a new strategy, whereby a general parent assembly was replaced by meetings with the contact teacher, which in the views of the school leader would also allow the parents to get to know each other. I have also received a one-page description of Park’s attempt to organize a meeting where parents were more active. As a part of this initiative, contact teachers were supposed to hold a 20-min group discussion in a classroom setting about how parents “think middle school is different from high school” and what expectations they have of “the teachers and the school” with written answers presented in plenum. The following excerpt is taken from the description of the reasoning behind this new plan:

School-home collaboration project method aims to reach parents with immigrant backgrounds in a more dialogue-based way that seems engaging and in a slightly more “harmless” setting. The goal is to get immigrant parents more involved in the field so that they can help the school to help their children succeed in school.

Although the counselor who suggested the method was on parental leave during my study, it is interesting that the suggestion was still presented to me as a form of documentation. Not going into details of how migrant parents are presented in this discourse, in terms of school practice, which is the focus of this article, the idea of changing meeting form to reach out to parents is in this document seen as novel and requiring “committed school leaders and committed teachers.”

In terms of other opportunities for building networks, and thus maintaining and gaining social capital, when asked if parents formed any groups or if they mostly had one-on-one contact with the school, a school leader at Birchwood answered:

You used to know all the parents of your 10th grade, but suddenly you’re in our region. Now you can apply to seven different schools, and then here, you suddenly have no parent network. So, I, as a parent, also experienced going to parent meetings and not knowing anyone. It’s a bit like “hello,” but very distant.

The school leader argues that it is normal irrespective of parent background, for parents of all high school children to lose contact with each other as the students choose schools in different parts of the city or municipality. Contrary to this description of normality in this middle-class suburban school with migrant parents in the minority, urban Park High was hosting a newly established mothers’ group. According to the group’s leader that I interviewed, their purpose was mainly to empower the local women to support the community by, for example, patrolling the streets at night, and to help the newly arrived families orient themselves in the city’s public services. The school was not the organizer or the sole focus of the group’s program, but they offered parenting courses where the importance of attending parent meetings was specifically communicated. At Park, the leader hoped that the new parent network could help them reach the parents they “needed.”

At this school, the expectations regarding parental involvement were higher than at the two other schools, partly because of behavioral issues. I observed planning for a meeting at Park to address student behavior in one of the classes. A counselor led the discussion, listening to what the teachers who worked with the class experienced and giving advice on how to guide the meeting so that the conflict did not escalate, but all sides felt heard and appreciated, as exemplified by the following excerpt from my observation notes:

Counselor: [We need to master the] way to listen and understand, not comment, not justify ourselves, so that they [the students involved in a conflict] feel understood and listened to. Take up some challenges and how they experience them.

The counselor, the contact teacher, and the school leader came back to me after the meeting and said that they were thrilled and relieved when several parents came and showed support and understanding for the school. In my notes after the meeting, I quote the contact teacher saying:

It’s very good when the parents are, like, “I know how this feels, what you are faced with” when they support us. It is good that you’ve put some effort into [planning] this.

As I interpret it, parents were “needed” by the school partly because student behavior was, like in the situation I observed, more often perceived as a challenge. School leaders and teachers were thus disappointed when many parents did not meet up. Both general and individual meetings were seen as an important opportunity to establish and maintain contact and, apparently, control. Irrespective of the motivation behind the efforts to invite more parents and build a parent network, the parents at Park were visible. The leader expressed to me that she was surprised at how many parents now showed up for the open house the school organizes for potential applicants. Students attended and were actively involved in all the aforementioned meetings. This is also true of the so-called parent conferences, which in my experience were teacher-student conferences with parents in attendance, which are described below.

In sum, the two primary forms of at-school involvement including groups of parents were general meetings and school-initiated contact in crises. On those occasions, the attending parents were, as was the tradition, expected to be passive listeners, with room for only a few questions after presentations made by the school staff. When attempts to introduce dialogue were made, the discussion was still to be carefully planned and strongly controlled by the school. The parents could write or speak in front of a large audience and always on school territory. Only Park High leadership was concerned with building a community network that connected local parents and the school. Given the cultural heterogeneity of this school’s parent population, this effort can contribute to parents maintaining and developing their social capital, especially if it prompts the parents to see each other as a source of support. This initiative can be further strengthened if, hopefully, some of the Southeast Asian parents (a large group at Park), many of whom are already rich in school-related social and cultural capital, are also invited to join the group. This assertion also aligns with the findings of Li and Sun (2019) pointing to the importance of closer contact between schools and Asian immigrant families. They argue that when parents meet the school, students get new opportunities to negotiate the sociocultural differences that can create conflict between how education is approached at home and school, while teachers better understand the differences within this group, thereby avoiding the model minority stereotype.

One-on-one contact: Planned conferences and crisis communication

In terms of planned direct contact between parents and teachers, there is a legal requirement that high schools hold two annual parent-teacher conferences before the students reach the age of majority of 18 to discuss student progress and well-being. Starting from the compulsory school, students almost always attend these meetings, and sometimes take the lead in organizing them as a presentation of their recent work and progress. As high school students could, to a large degree, decide whether the parents needed to be there at all, I noted that the teachers often did not know whether the students’ parents would be attending.

At the online student-teacher meetings I observed under COVID-19 rules at Park, one or two parents were present at 8 out of 15 conferences. One of the three conferences I observed at the school premises was attended by a father. One teacher explicitly decided not to invite parents on this occasion, choosing instead to maintain contact via regular phone calls. The meetings were organized as 10-15 min conversations with individual students, where the teacher, once or twice, asked the parents whether they had “anything they wonder about,” and after receiving a short answer or a simple “no” followed by one more question and a brief response, the conversation returned to the student. On a few occasions, the parents were unsure whether the teacher was talking to them or the student, as the student was usually at the center. This dynamic is demonstrated in the following extract from an online conference with a first-year student. After suggesting some strategies to improve his English grade, the teacher turns to the father:

Teacher: Anything you wonder about?

Father: Generally, how it goes. Many things are new [after middle school. It’s] difficult to follow.

Teacher: A lot is new for us too. We see society turned upside down.

Father: What will happen to the assessments [under lockdown]?

Teacher: Assessments are so much more than just tests. Tests do not show the full extent of what students can do! We take a more holistic approach. I think it’s important. Some do well on the tests, some do very poorly. The math exam is fully digital, English – more listening, filling in, oral, choice. We don’t know much yet. Teachers are also waiting.

Father: [There’s] lots of change, from day to day.

Teacher: Some classes are quarantined for the fourth time. You [students] need to be at school, but it works when you come every other day.

Father: Better than nothing.

Teacher: I focus on 16 students. [Back to the student] Anything you wonder about?

All parents except one had migration background but did not seem to have problems understanding Norwegian. All three schools reported that they used interpreters in individual meetings whenever parents indicated that this was required. All students in the class I observed were born in Norway or came to Norway as small children, except for one. This student’s father, who has been in Norway for 4 years, was present and responded to the teacher with a few words. The student struggled somewhat with language related to educational and subject choices, but the teacher explained things several times until the point seemed to come through. The language barrier and time expectations could have made some parents more hesitant to ask more questions and the teacher reluctant to delve deeper into the matters they were discussing (the content of conversations is addressed in more detail in section “Matters to discuss with parents”).

Most attention was placed on students’ measurable goals and individual strategies for reaching them in the different core subjects, with the contact teachers dedicating more time to their subject areas. A few migrant parents engaged actively and naturally with these matters in their dialogue with the school, asking about homework, grades, and tutoring opportunities. However, most parents, including the only non-migrant (mother), took on a more subtle interest and caring role, often briefly praising the student for being clever, hard-working, or motivated. A leader at Park stated that the school alternated between inviting and not inviting parents to student-teacher meetings because the one-on-one time between the teacher and the student with complete focus on the student’s academic progress and goals was seen as necessary, as indicated below:

Because you may want to create motivation in the young person, and then the parents may be sitting there being very critical of their own child. We have to try to do a little bit of both.

None of the parents I have observed or interviewed in the larger study, however, appeared to be critical of their children. The COVID-19 lockdown has provided opportunities for gaining insight into more personal and familial exchanges between the teacher and the families in online meetings. I have observed the teacher expressing concern regarding the time spent by the student on schoolwork, proposing ways of going out to get some fresh air. I have also witnessed a short exchange about a recent loss of a family member, where the teacher responded, “When something like this happens, it will affect anyone. You should allow yourself. just always do your best.” One of the parents questioned their adolescents’ multitasking habits, and the teacher calmed her down:

It’s not good, but mine at home are the same. The brain works best when we sit and focus. […] But listening to music is effective. They don’t notice. [With] 23 [students] in the classroom, they’re not used to having it very quiet.

Here, the teacher can be seen as helping the parents to support student autonomy, in line with Deslandes and Barma’s (2016) observation that high school teachers need to be mindful of the challenge parents face in establishing a right balance between adolescents’ autonomy and connection to allow for openness in their relationship. However, these short exchanges never developed into full-scale mediation between parents and students, and the conversation quickly returned to the student and specific learning strategies and goals.

At Birchwood and Fjord, the direct information flow between the school and the parents for “non-problematic” students was limited unless initiated by the parents. No opportunities for parental engagement in school decision-making or digital communication were provided. Parents could ask for access to the students’ digital platform with grades and lesson plans. Based on the information gathered as a part of my larger study, students and teachers at all three schools concurred that most parents never made such requests. The leadership of all three schools spoke of their attempts to expand outreach to all parents by promoting the practice of the contact teacher routinely phoning or sending an e-mail to parents of the entire first-year class, making them welcome at school, and inviting them to the first general meeting. Several teachers commented that the parents were surprised when the school used the time just to welcome them, as they were used to be approached only in difficult situations. It appears that some parents (mostly non-migrants) did initiate communication with the school, usually by calling to raise a complaint or claim their child’s rights. At Birchwood, according to the information a school leader shared during the interview, a special hierarchy was developed for parent calls to prevent parents from routinely contacting the principal. At Park, where most parents had migrant backgrounds, the leader I interviewed and observed did have contact with several parents, as students that we met followed up on earlier conversations she had with their parents, and parents ringed while I was in her office. Even contact in times of difficulty or crisis could be limited to students under the legal age of 18. Older students could withdraw permission for the school to contact their parents and, as a leader at suburban Birchwood said, contact was generally “phases out” once students reached the age of 18.

To summarize, my findings concerning the form of one-on-one contact with the parents, digital or physical, correspond to those of Seitsinger (2019), who reported that high schools had contact with parents less than once a week. They also concur with the observations made by Deslandes and Barma (2016), indicating that parents of high school students perceive teachers as reluctant to make contact before things get “very serious” (p. 19). Some parents did have contact with the school, but they had to possess the relevant cultural capital in order to initiate it. Before turning to the content of school-parent encounters, I note that the agendas of these meetings were predominantly formulated and often carefully conceived by the staff. The school not only largely decided how meetings were organized but also formulated the matters to be discussed. In the next section, I analyze these discussion topics based on my observations, PowerPoint presentations from general meetings, and templates for student-teacher conferences.

Matters to discuss with parents

The matters the schools expected to discuss with the parents, outside crises, were predominantly related to students’ individual academic achievement and well-being expectations. At Park, the school leader, for example, said that some parents phone her often early in the year and share concerns that their child has not yet made any new friends. According to the interviews and presentations I studied, the typical themes of general meetings included teaching and attendance, assessment (the difference between summative and formative evaluations), student rights and ways to handle complaints, and subject and education choices (see summary in Table 3). These topics concur with those that emerged from Antony-Newman’s (2018) meta-synthesis of research on parental involvement of immigrants, showing that involvement was defined in narrow school-centric terms of academic performance, which meant that “issues of genuine inclusion of immigrant parents, their cultures and experiences are often side-lined” (p. 367; see also Doucet, 2011).

When presenting their expectations of parental involvement at the general assemblies, all school leaders highlighted the importance of school-home collaboration and provided contact information and dates for new meetings, as well as outlined the way student attendance was registered. The principal at Fjord defined the parental role at high school as follows:

Many people probably think that now the students and children are so big and mature, they are 16–17 years old, and now we as parents do not have to think so much about school anymore. But all experience shows that it is very important that you, parents, get into the school race together with the student by asking about how things are going at school, what kind of subjects you have had today, what did you learn today and so on. That’s very important. We do not expect you to be able to provide homework help in all sorts of subjects, but [to communicate] general interest in schooling. It helps to strengthen the opportunity for the student to graduate and pass the school year.

The school leader further expressed that they expected to be able to contact the parents even once the student turned 18, and the students signed special voluntary consent forms to enable this continuation. Birchwood also had a detailed summary of their view of parental involvement at high school, which according to its PowerPoint presentation, is:

• The students are approaching the age of the majority.

• Parents and guardians become less important.

• School is the students’ choice and responsibility.

• However, parents can support and help.

• Be aware of notifications about attendance.

• We call in parents and guardians when needed.

The schools appear to differ in their approach to parental involvement. It is more welcoming at Fjord that, as a school with mostly vocational programs, is not often approached by “complaining” middle-class parents, and is more reserved at Birchwood, where those parents are in the majority. It is also worth noting that no references to culture, religion, or social issues were made in any of the presentations, thus treating all parents as a homogenous group. Both presentations are in line with the findings obtained in the Norwegian (Vedeler, 2021) and international context (Hoover-Dempsey et al., 2009; Deslandes and Barma, 2016), showing that at-school involvement is not part of the natural, doxic ways of parents of high school students. The involvement is seen as largely instrumental, with the aim of supporting completion and ultimately graduation (see also Antony-Newman, 2018).

As described in the previous section, the parent conferences I observed loosely followed the school’s template that teachers were encouraged but not required to use. The template states the goals of the conversation as a reflection on the student’s academic ambitions, learning strategies, and classroom environment. The latter meets the requirements under Section 9A-4 of the Education Act adopted to counteract bullying and protect student well-being. The template also included questions related to student well-being, first-semester grades, learning strategies, teacher expectations, choice of subjects, and dreams and ambitions. In relation to the learning strategies, the teacher and student discussed organizing study groups and transitioning from school to university, requiring more independent learning strategies. The parents showed interest in homework, tutoring (Homework Club), and organizing the time and space for homework completion. All parties were concerned with the new formative assessment forms and subject choice.

When asked about parent complaints in their interviews, the leaders of all three schools talked about their responsibility to get the parents to trust that they work in the students’ best interests. At the same time, especially when migrant parents were concerned, the school leaders were sometimes convinced that the teachers and school counselors had a better understanding of students’ interests than their parents did and felt they would breach the students’ trust if they engaged with the parents. At Park High, there was also a clear concern for students’ safety at home, and the school provided room for a special “minority councilor” employed by the Directorate for Integration and Diversity specifically to counter “negative social control, forced marriage, and honor-related violence.” These concerns were notably made by teachers and school leaders based on their conversations with students and experience dealing with crises, given that they did not have long-term trusting relations with many of the parents. The schools especially guarded students’ independence in choosing subjects and higher education or career. Park and Birchwood saw it as their responsibility to guide the parents to understand that “not everyone should become a doctor or a lawyer” and that many other professions existed and that could be more appropriate for their children. Apart from minority councilor’s job description, in the three schools and outside general meeting context migrant parents were not treated as a homogeneous group. The school leaders, sometimes after being prompted to share their views about students outside induction classes, did indicate the somewhat essentialized categories of refugees, newly arrived students, work migrants, Muslims, and model minority Asian students, or remembered individual parents with whom they were in more regular contact. Both leaders interviewed at Birchwood said that, in their experience, differences between migrant parents are much greater than between “Norwegians.” Still, the school policies and practices did not indicate that the schools saw this heterogeneity as worth exploring in any depth. Moreover, the information leaders provided about individual students was not always confirmed in the interviews with those students.

Discussion: Schools’ shifting responsibility

The preceding analysis of interviews with school leaders, observation notes, and presentations indicates that the way the three schools in focus of this study addressed parental involvement was contextualized. Schools differed in terms of the matters discussed, including which parents got to have a say on their children’s education and choices. Differences were also noted in the degree to which teachers and school leaders saw engaging all families as their responsibility. Interestingly, as the schools moved from the more segregated practices of individual “migrant” classes to more inclusive practices, their attention to migrant parents waned. As a result, the doxa of minimal parental involvement beyond the context of crisis management was implicitly restored. The exception was made for parents who “knew the students” rights’ and had the right forms of capital (which mostly applied to parents that were not migrants) to position themselves as dominant in the field and make the school responsive and responsible. This created what Bourdieu (2000) calls the situation of “real inequality within formal equality” (p. 76). When crises occurred, the migrant parents were invited but were engaged in the discussion in a subordinate role of disciplinarians. Still, getting them on board was difficult, primarily because no time was invested by the school personnel to earn their trust, as pointed out by Deslandes and Barma (2016).

The ideal of free choice and the teachers’ concern with safeguarding student autonomy by not involving the parents unless this was deemed necessary correspond to some of the values demonstrated in Vedeler’s (2021) study of the Norwegian high school approach to all parents. The emphasis on student independence and individual choice can be connected to Gullestad’s (1996) descriptions of the modern quest of youth finding themselves and exploring their identity through resisting and reinterpreting family influences. The author argued that, to meet the needs of the modern flexible entrepreneurial economy, children needed to learn to be “tuned to indirect and subtle cues, to be a part of teamwork where the power relations can be more or less hidden” (p. 37). The modern parenting style Gullestad describes with its subtle expectations and focus on internal discipline today can be attributed especially to the cultural middle-class of academics, journalists, or writers, which can include teachers. In her interviews with middle-class high school students, Eriksen (2020, p. 108) observed that, in contrast to the cultural middle-class with its “detachment between parents and school” and internalized career ambitions, financial middle-class parents made quite explicit academic demands of their children and practiced direct consequences to award or punish school achievement. This assertion may indicate that the teacher practices identified in the present study are guided by habitus associated with their class rather than by any uniform Norwegian or Western culture they intend to instill in students whose migrant parents are not socialized with the same values of flexibility and identity exploration that form the cultural capital appreciated by the field of schooling (see also Lareau, 2011).

In line with this doxic understanding of parent role at high school, all three schools provided limited opportunities and had no expectation for parental involvement in positive or neutral cooperation. There were also no systematic guidelines for moderating conflicts between parents and children, and unplanned contact or access to community networks was rarely provided by the schools, unlike the findings reported by Villavicencio et al. (2021). Schools did not invite parents to discuss curriculum or the students’ home culture values, dreams, and educational plans, although at Park, they could be present at some of such discussions between teacher and student. Generally, families were recognized as an important part of the students’ life, which was seemingly expected to largely remain outside the school’s purview. In line with the national trends recognized in the general labor agreement, insufficient resources were allocated to support development of trust by all parents, as other pressing issues were given precedence (school behavior, new curriculum, new teaching and assessment methods, anti-bullying campaigns). These priorities describe the influence of the field of power that impacts what is recognized as valuable capital in the global field of education policy (Bourdieu, 1996; see also Lingard et al., 2005). The teachers, especially in the Norwegian context, still maintain a degree of autonomy from the field of power and could demonstrate resistance to the dominant practices by recognizing the migrant parents’ capital, as for example described by Rissanen (2022). As long as teachers only merit non-migrant middle-class parents’ attempts to interfere and remain unwilling to initiate change themselves, the school system will only serve to perpetuate inequalities in student performance, well-being, and educational aspirations. The findings yielded by this study confirm the observation made by Lareau and Horvat (1999) more than two decades ago that only parents who manage to engage their cultural and social capital in the school field by actively demanding attention and acting in the interests of individual students benefit from the legislative change. As a possible exception, staff at Park High, with its large population of students with migrant backgrounds, is readily discussing new ways of involving parents more, thus breaking with the traditional discourses on parents’ absence at high school from a position of power. However, these discussions still mostly focus on “hard-to-reach parents” (Crozier and Davies, 2007) who may be failing in their taken-for-granted role as emotional supporters and disciplinarians for their adolescent children. Some indications that schools are willing to take greater responsibility for broader involvement of all parents are emerging at Park High, both through new, more inclusive forms of involvement and communication, including this school’s cooperation with the local mothers’ group, as well as through unplanned telephone contacts and new conversations with parents about student well-being and future plans brought about by the recent COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion

A decade after the first policy changes introduced mandatory home-school communication in Norwegian high schools, the teachers that took part in the present study have developed a new awareness of the importance of parental involvement in students’ transition to higher education and work. At the same time, the schools appear to have limited room for imagining unorthodox forms and content of cooperation with the home. The focus on the relatively few formally organized occasions when parents meet the school staff is mostly on appraisal, attendance, and student behavior. These themes and forms of communication are more appropriate for the parents with middle-class habitus who are more concerned with their children’s performance and are more at ease in the school environment. Hence, many migrant parents’ reluctance to be involved in these limited roles may not be surprising. An unorthodox broader recognition of the families’ resources, interests, and futures beyond individual student performance on measurable outcomes would be a positive next step in expanding parental involvement in a diverse world. In light of Bourdieu’s analysis of the school as a stratified field, this recognition would be more difficult to accomplish at schools with a long history of “orchestrated” relations with parents in which parents’ more subtle forms of engagement with the children’s education are taken for granted (Bourdieu, 2000). It remains to be seen how the new stream of immigrants from Ukraine can affect the schools’ practices. The school system may perceive this development as a crisis requiring extra temporary investment to build mutual relationships, if only initially, to resort to some practices of governmentality common at lower grades (Bendixsen and Danielsen, 2020). At the same time, the relatively high level of education and perceived cultural closeness to this new group of parents could create an expectation of a more seamless orchestration with the school’s doxa and relieve the teachers of their sense of responsibility to initiate more contact. In this case, they will be unlikely to make sufficient room for the new migrant parents to engage their cultural capital. Still, as indicated by the findings reported here, there is an urgent need for a wider professional and political discussion on more equitable and situated forms of engaging parents with an emphasis on school responsibility for taking the initiative and establishing trust. To accomplish lasting change, additional resources should be made available for contact teachers in the collective labor agreement. As recognized parties in the field’s discourse, who possess a certain degree of reflexivity, teacher educators and teachers should take the lead in these discussions and demonstrate resistance to the field’s doxa. As this study indicates particularly strong doxic resistance against equitable involvement of parents at the upper-secondary level, further empirical research, including larger quantitative studies at high school, is needed. Change in practice is necessary if the schools are to fully benefit from cultural diversity. School leaders and staff then can appreciate all parents beyond their currently narrow roles of disciplinarians and complainers and to facilitate respectful inclusion of students and families of all backgrounds in educational communities and society.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available in order to maintain participant anonymity. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to JM, anVsaWEubWVsbmlrb3ZhQGhpdm9sZGEubm8=.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

JM was the only contributor to this article and has designed the study, completed ethical approval process, data collection, analysis, and all writing in the manuscript.

Funding

This research and open access publication was funded by Volda University College.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

- ^ All names are pseudonyms, and some details were omitted or changed to maintain confidentiality. Schools, and subsequently individual staff members, otherwise could be easily identified in the relatively small Norwegian context.

- ^ The schools in Norway do not collect or publish statistics on student or parent backgrounds. School profiles are based on interviews with the school leaders.

- ^ According to municipal information, the offer is adapted for students who need to strengthen their knowledge of Norwegian, English, and other general subjects, before they can apply for ordinary senior high school courses.

- ^ According to municipal information, the offer is adapted to students who can complete high school in the standard 3 years with some extra language support. The offer is designed for students who can compensate for academic gaps by “working hard” and who aim for higher education. The study requires approximately 3.5/6.0 grade points in science and/or social studies from secondary school.

References

Antony-Newman, M. (2018). Parental involvement of immigrant parents: A meta-synthesis. Educ. Rev. 71, 362–381. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2017.1423278

Antony-Newman, M. (2020). Parental involvement of Eastern European immigrant parents in Canada: Whose involvement has capital? Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 41, 111–126. doi: 10.1080/01425692.2019.1668748

Bæck, U.-D. K. (2017). It is the air that we breathe. Academic socialization as a key component for understanding how parents influence children’s schooling. Nordic J. Stud. Educ. Policy 3, 123–132. doi: 10.1080/20020317.2017.1372008

Ball, S., Macrae, S., and Maguire, M. (2013). Choice, pathways, and transitions post-16: New youth, new economies in the global city. London: Routledge.

Bendixsen, S., and Danielsen, H. (2020). Great expectations: Migrant parents and parent-school cooperation in Norway. Comp. Educ. 3, 349–364. doi: 10.1080/03050068.2020.1724486

Bjurstrøm, R. (2022). Ny arbeidstidsavtale for skolen: Flere får doblet kontaktlærerressursen [New employment contract for the school: Contact teacher resource doubled for many]. Utdanningsforbundet [Education Union]. Available online at: https://www.utdanningsforbundet.no/nyheter/2022/ny-arbeidstidsavtale-for-skolen-flere-far-doblet-kontaktlarerressursen/ (accessed January 17, 2022).

Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1996). The state nobility: Elite schools in the field of power. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bourdieu, P. (ed.) (1999). The weight of the world: Social suffering in contemporary society. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Crozier, G. (2001). Excluded parents: The deracialisation of parental involvement. Race Ethnicity Educ. 4, 329–341. doi: 10.1080/13613320120096643

Crozier, G., and Davies, J. (2007). Hard to reach parents or hard to reach schools? A discussion of home-school relations, with particular reference to Bangladeshi and Pakistani parents. Br. Educ. Res. J. 33, 295–313. doi: 10.1080/01411920701243578

Deer, C. (2008). “Doxa,” in Pierre Bourdieu. Key concepts, ed. M. Grenfell (New York: Acumen), 119–130.

Deslandes, R., and Barma, S. (2016). Revisiting the challenges linked to parenting and home-school relationships at the high school level. Can. J. Educ. 39, 1–32.

Doucet, F. (2011). Parent involvement as ritualized practice. Anthropol. Educ. Q. 42, 404–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1492.2011.01148.x

Epstein, J. L. (2008). Improving family and community involvement in secondary schools. Educ. Digest 73, 9–12.

Epstein, J. L., Sanders, M. G., Sheldon, S. B., Simon, B. S., Salinas, K. C., Jansorn, N. R., et al. (2019). School, family, and community partnerships: Your handbook for action. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin press.

Eriksen, I. M. (2020). Class, parenting and academic stress in Norway: Middle-class youth on parental pressure and mental health. Discourse Stud. Cult. Politics Educ. 42, 602–614. doi: 10.1080/01596306.2020.1716690

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qual. Inquiry 12, 219–245. doi: 10.1177/1077800405284363

Foucault, M. (1991). “On governmentality,” in The Foucault effect: Studies in governmentality, eds G. Burchell, C. Gordon, and P. Miller (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press), 87–104. doi: 10.7208/chicago/9780226028811.001.0001

Gullestad, M. (1996). From obedience to negotiation: Dilemmas in the transmission of values between the generations in Norway. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. 1, 25–42. doi: 10.2307/3034631

Hegna, K., and Smette, I. (2017). Parental influence in educational decisions: Young people’s perspectives. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 38, 1111–1124. doi: 10.1080/01425692.2016.1245130

Helland, H., and Wiborg, ØN. (2019). How do parents’ educational fields affect the choice of educational field? Br. J. Sociol. 70, 481–501. doi: 10.1111/1468-4446.12370

Hill, N. E., Castellino, D. R., Lansford, J. E., Nowlin, P., Dodge, K. A., Bates, J. E., et al. (2004). Parent academic involvement as related to school behavior, achievement, and aspirations: Demographic variations across adolescence. Child Dev. 75, 1491–1509. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00753.x

Holme, J. J. (2002). Buying homes, buying schools: School choice and the social construction of school quality. Harvard Educ. Rev. 72, 177–206.

Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., Ice, C. L., and Whitaker, M. C. (2009). “‘We’re way past reading together’: Why and how parental involvement in adolescence makes sense,” in Families, schools, and the adolescent: Connecting research, policy, and practice, eds N. E. Hill and R. K. Chao (New York, NY: Teachers College Press), 19–36.

Jónsdóttir, K., Björnsdottir, A., and Bæck, U.-D. K. (2017). Influential factors behind parents’ general satisfaction with compulsory schools in Iceland. Nordic J. Stud. Educ. Policy 3, 155–164. doi: 10.1080/20020317.2017.1347012

Jørgensen, C. H. (2018). “Young people’s access to working life in three Nordic countries: What is the role of vocational education and training?,” in Work and well-being in the Nordic countries, eds H. Hvid and E. Falkum (London: Routledge), 155–177.

Kim, Y. (2009). Minority parental involvement and school barriers: Moving the focus away from deficiencies of parents. Educ. Res. Rev. 4, 80–102. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2009.02.003

Kindt, M. T. (2018). Right choice, wrong motives? Narratives about prestigious educational choices among children of immigrants in Norway. Ethnic Racial Stud. 41, 958–976. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2017.1312009

Kryger, N. (2012). “Ungdomsidentitet – mellem skole og hjem [Youth identity – between school and home],” in Hvem sagde samarbejde, eds K. I. Dannesboe, N. Kryger, and C. Palludan (Aarhus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag), 89–129.

Lareau, A. (2011). Unequal childhoods: Class, race, and family life, 2nd Edn. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, doi: 10.1525/9780520949904

Lareau, A., and Horvat, E. M. (1999). Moments of social inclusion and exclusion: Race, class, and cultural capital in family-school relationships. Sociol. Educ. 72, 37–53. doi: 10.2307/2673185

Li, G., and Sun, Z. (2019). “Asian immigrant family school relationships and literacy learning: Patterns and explanations,” in The Wiley handbook of family, school, and community relationships in education, eds S. B. Sheldon and T. A. Turner-Vorbeck (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.), 29–51. doi: 10.1002/9781119083054.ch2

Lingard, B., Rawolle, S., and Taylor, S. (2005). Globalizing policy sociology in education: Working with Bourdieu. J. Educ. Policy 20, 759–777. doi: 10.1080/02680930500238945

Modood, T. (2004). Capitals, ethnic identity and educational qualifications. Cult. Trends 13, 87–105. doi: 10.1080/0954896042000267170

Norway Ministry of Education and Research (1998). The education act. Available online at: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NLE/lov/1998-07-17-61 (accessed September 5, 2022).

Norway Ministry of Education and Research (2006). Forskrift til opplæringslova [Regulation to the Education Act]. Available online at: https://lovdata.no/dokument/LTI/forskrift/2006-06-23-724 (accessed June 23, 2022).

Pananaki, M. M. (2021). The Parent–Teacher Encounter: A (mis)match between habitus and doxa (Doctoral dissertation). Stockholm: Stockholm University. Available online at: http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1544222/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed September 9, 2022).

Rapley, T. (2012). “The (extra)ordinary practices of qualitative interviewing,” in The SAGE Handbook of Interview Research: The comPlexity of the Craft, eds J. F. Gubrium, J. A. Holstein, A. B. Marvasti, and K. D. McKinney (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE publications), 541–554. doi: 10.4135/9781452218403.n38

Reay, D. (1998). “Bourdieu and cultural reproduction: Mothers’ involvement in their children’s primary schooling,” in Bourdieu and education: Acts of practical theory, eds M. Grenfell and D. James (London: Taylor and Francis), 55–71. doi: 10.1177/136548020200500306

Reay, D., Davies, J., David, M., and Ball, S. J. (2001). Choices of degree or degrees of choice? Class, ‘race’ and the higher education choice process. Sociology 35, 855–874. doi: 10.1177/0038038501035004004

Rissanen, I. (2019). School principals’ diversity ideologies in fostering the inclusion of Muslims in Finnish and Swedish schools. Race Ethnicity Educ. 24, 1–20. doi: 10.1080/13613324.2019.1599340

Rissanen, I. (2022). School–muslim parent collaboration in Finland and Sweden: Exploring the role of parental cultural capital. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 66, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2020.1817775

Rule, P., and John, V. M. (2015). A necessary dialogue: Theory in case study research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 14, 1–11. doi: 10.1177/1609406915611575

Seitsinger, A. M. (2019). “Examining the effect of family engagement on middle and high school students’ academic achievement and adjustment,” in The Wiley handbook of family, school and community relationships in education, eds S. B. Sheldon and T. A. Turner-Vorbeck (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell), 163–182. doi: 10.1002/9781119083054.ch8

Simons, H. (2009). Case study research in practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE publications. doi: 10.4135/9781446268322

Vandenbroeck, M., and Bie, M. B.-D. (2006). Children’s agency and educational norms: A tensed negotiation. Childhood 13, 127–143. doi: 10.1177/0907568206059977

Vedeler, G. W. (2021). Practising school-home collaboration in upper secondary schools: To solve problems or to promote adolescents’ autonomy? Pedagogy Cult. Soc. 1–19. doi: 10.1080/14681366.2021.1923057 [Epub ahead of print].

Villavicencio, A., Miranda, C. P., Liu, J. L., and Cherng, H. Y. S. (2021). ‘What’s going to happen to us?’ Cultivating partnerships with immigrant families in an adverse political climate. Harvard Educ. Rev. 91, 293–318. doi: 10.17763/1943-5045-91.3.293

Vincent, C. (2000). Including parents? Education, citizenship and parental agency. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Vincent, C. (2017). ‘The children have only got one education and you have to make sure it’s a good one’: Parenting and parent–school relations in a neoliberal age. Gender Educ. 29, 541–557. doi: 10.1080/09540253.2016.1274387

Wang, M. T., and Sheikh-Khalil, S. (2014). Does parental involvement matter for student achievement and mental health in high school? Child Dev. 85, 610–625. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12153

Keywords: parental involvement, high school, migrant parents, upper-secondary education, parental engagement

Citation: Melnikova J (2022) Migrant parents at high school: Exploring new opportunities for involvement. Front. Educ. 7:979399. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.979399

Received: 27 June 2022; Accepted: 30 August 2022;

Published: 21 September 2022.

Edited by:

Juana M. Sancho-Gil, University of Barcelona, SpainReviewed by:

Fernandoo Hernández-Hernández, University of Barcelona, SpainPauliina Alenius, Tampere University, Finland

Copyright © 2022 Melnikova. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Julia Melnikova, anVsaWEubWVsbmlrb3ZhQGhpdm9sZGEubm8=

Julia Melnikova

Julia Melnikova