- 1Department of Computational Media, University of California, Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA, United States

- 2Immergo Labs, Santa Cruz, CA, United States

Acculturative stress disproportionately impacts first-generation Latine-Americans, leading to significant mental health risks stemming from intergenerational cultural norms around gender identity and sexuality. Facilitating communication is critical in reducing this stress, yet it can be challenging for Latine individuals to take the first step in expanding their views due to limited resources, cultural pressure, and motivational needs. On the other hand, serious games provide a unique opportunity to address this challenge by introducing novel experiences to encourage the growth of perspectives in acculturative norms. This article presents a narrative review that bridges three key concepts: (1) acculturative stress in Latine-American communities, (2) modern behavior change theory and model, and (3) the design of serious games. We conclude by proposing a framework for Acculturative Game Design (AGD) and discuss considerations for fostering the support of intergenerational relationships around Latine identity.

1. Introduction

Many Latine1 individuals migrate to the United States in search of a better life and a brighter future for themselves and their children. According to data from 2019, 60.5 million Latine individuals reside in the US, with 19.8 million immigrants (Batalova and Hanna, 2021), and the rest are US-born. Latine immigrants undergo acculturation, a process of adopting the cultural traits of their new environment. While this adaptation is challenging for immigrants, their US-born children, the first generation,2 grapple with straddling two cultures - that of their familial roots and their American surroundings (Berry, 2015). This duality can cause tensions in communication, identity formation, and social integration. Starting a conversation between these two generations may be challenging, especially when topics like gender identity and sexuality are involved. The influence of religion, deeply rooted in many Latine communities, plays a significant role in shaping beliefs and attitudes toward these subjects. For example, Espin (2018) highlights that religious teachings and traditional cultural norms in Latine communities often stress conservative perspectives on gender roles and sexuality, sometimes leading to friction between traditional views and the evolving identities of first-generation children. Not every Latine family experiences a strain in their relationship and neglect from parent to child; however, the clash of identity and familial values can still occur (Gerena, 2021). This can lead to difficulties in communication between parents and children due to language barriers and the blending of different cultural backgrounds (Berry, 2015).

First-generation Latine children may face challenges in discovering their gender identity and sexuality, which may differ from their parents' teachings. This can lead to a distance between the child and their parents and fear of rejection (Gerena, 2021). This distance, lack of communication, and acculturation can contribute to mental health struggles for first-generation Latine children. Studies have shown that Latine individuals born in the United States have higher rates of psychiatric disorders compared to Latine immigrants (Alegría et al., 2008; Pumariega et al., 2010). In 2015, a survey found that 18.9% of Latine students in 9th–12th grade considered attempting suicide, 15.7% planned to attempt suicide, 11.3% attempted suicide, and 4.1% attempted suicide that resulted in medical treatment (Kann et al., 2014). A more recent report has linked increased suicide risk among Latine individuals to factors such as family dysfunction, lower socioeconomic status, acculturation, and identifying as Latino homosexual (Rothe and Pumariega, 2018). Studies have also found that Latine individuals are particularly vulnerable to psychological stresses related to immigration and acculturation and are often under-treated due to communication barriers with healthcare providers (American Psychiatric Association, 2017).

The LGBTQ+3 population, a minority group, also has significant statistics regarding mental health. Research shows that individuals who identify as LGBTQ+ are more likely to have mental health issues and substance misuse than heterosexual individuals (Silvestre et al., 2013; Semlyen et al., 2016). They are also two and a half times more likely to experience anxiety, depression, and substance abuse, which are often triggered by negative social stigmas and discrimination (Kates et al., 2018). Prejudices against LGBTQ+ individuals can occur when receiving health care, preventing them from seeking further care (Safer et al., 2016). A lack of a social support network increases the likelihood of developing mental health disorders for LGBTQ+ individuals who experience familial and/or peer rejection (Hsieh, 2014). Additionally, the rate of suicide attempts is higher for LGBTQ+ youth than heterosexual youth (Kann et al., 2016). Many of these issues stem from discriminatory and intolerant environments for LGBTQ+ individuals (Silvestre et al., 2013).

The mental health struggles among youth, irrespective of their cultural or ethnic background, are of significant concern. Across different communities, the increasing rates of mental health issues can be attributed to various factors, ranging from socio-economic challenges to pressures of modern living (Twenge et al., 2019). It is universally acknowledged that seeking assistance from peers, family, or medical professionals can be pivotal in addressing these challenges. While these concerns apply broadly, certain groups face unique challenges. For the Latine community, cultural, socio-economic, and acculturative factors exacerbate the situation. Specifically, cultural taboos surrounding mental health in many Latine communities can deter individuals from seeking the help they need (Cabassa, 2016). Socio-economic factors further compound this: in 2017, at least 18% of Latine individuals reported not having insurance (Noe-Bustamante, 2020), and in 2019, 15.7% of Latine individuals lived in poverty (Creamer, 2020), restricting their access to healthcare resources.

For the Latine community, these challenges have intergenerational implications. It is of utmost importance for both the parental migrant generation and the first-generation children to foster open communication, which can act as a buffer against mental and emotional strain. Acculturation, characterized by individuals reconciling or reassessing their cultural beliefs against those of the dominant culture, can be a source of stress, especially in the presence of low family support (Rivera, 2007). The established stigma against seeking mental health services in the Latine culture further hinders addressing these issues (Cabassa, 2016). Thus, promoting communication between first-generation children and Latine immigrants about wellbeing becomes indispensable. Extant research confirms that such social support from family and friends significantly bolsters mental and emotional health (Turner and Marino, 1994).

Starting a conversation between these two generations may be challenging, particularly regarding gender identity and sexuality. Not every Latine family experiences a strain in their relationship and neglect from parent to child; however, the clashing of identity between familial values still occurs (Gerena, 2021). To address the significant burden of acculturative stress on mental health in Latine communities, it is crucial to begin an intergenerational dialogue that requires tremendous motivation among all stakeholders to mitigate this stress. This stress can be mitigated by challenging assumptions, expanding perspectives, providing social support, and being open-minded to diverse views (Yakunina et al., 2013; Thomas and Sumathi, 2016). However, resources for Latine communities in fostering this communication are often limited, unknown, or unevenly distributed. One potential strategy to help this intergenerational growth of views and communication is through serious games.

Serious games have increasingly gained attention as a potent medium for achieving significant behavioral and cognitive outcomes across various sectors. Within the educational domain, serious games have been documented to improve knowledge retention, engagement, and critical thinking, and they allow for practical simulation of real-world scenarios (Holloway et al., 2012; Thang, 2018; Conde, 2020; Conde et al., 2020). Health-focused serious games have also shown success in physical therapy, cognitive rehabilitation, and even pain management (Duval et al., 2018; Hurd et al., 2019). Studies have evidenced that games can shift attitudes and beliefs by providing experiential learning and fostering empathy, where players can deeply immerse in diverse roles and contexts, thereby gaining insights into varied perspectives (Greitemeyer and Osswald, 2010). One of the mechanisms through which games in health work is by enhancing self-efficacy, enabling users to better manage their conditions through virtual simulations and feedback (Hamari et al., 2016). In therapeutic contexts, serious games can provide a controlled and supportive environment where individuals can confront challenges, practice coping strategies, and reflect on their experiences (Holloway et al., 2012; Duval et al., 2018; Elor et al., 2018, 2019; Thang, 2018; Conde et al., 2020). For instance, therapeutic games have been developed to address issues ranging from PTSD to anxiety, and they function by employing principles from cognitive-behavioral therapy, narrative therapy, and exposure therapy (Fleming et al., 2017).

The underlying theoretical model that supports the efficacy of serious games is based on the idea that active, experiential learning can facilitate more profound understanding and bring about attitude and behavioral changes (Gee, 2008). Games uniquely engage players by offering them agency, allowing them to make decisions, and giving immediate feedback, making the learning experience more meaningful and impactful (Steinkuehler and Duncan, 2008). Given the ability of serious games to facilitate a shift in perceptions and beliefs, they present a promising medium for addressing acculturative stress within Latine communities. Acculturation, or the process of cultural adaptation, can be fraught with tensions arising from intergenerational differences in views on identity, sexuality, and other critical aspects of self. Thus, leveraging serious games to instigate conversations around these differences can bridge understanding and enhance communication within this community.

In light of this potential, this narrative review delves deeper into the application of serious games in fostering intergenerational dialogue within Latine communities. We begin by presenting a comprehensive review of three relevant pivotal concepts to this endeavor and propose a thought framework geared toward acculturative game design considerations. We aim to explore how serious games may strengthen intergenerational bonds and promote a more harmonious understanding of identity and sexuality.

1.1. Search strategy

This narrative review comprehensively examined three primary themes: Latine culture, motivation, and the design and application of serious games.

• Latine culture: for a nuanced understanding of Latine culture, we used keywords such as latine/x/a/o culture/cultural norms, LGBTQ+, sex/gender, acculturation, and assimilation. Our goal was to find peer-reviewed articles that deeply engaged with the lived experiences, cultural challenges, and identity dynamics of the Latine community.

• Motivation: to decipher the motivational underpinnings that make serious games effective, we employed search terms like behavior change, Self-Determination Theory, intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and user engagement. We aimed to unearth published papers that connected these motivational theories to game mechanics and user experiences.

• Serious game design and application: recognizing the centrality of game design to our inquiry, our search terms were broadened to include games, gamification, flow, serious games, serious game design, game mechanics, narrative design, game-based learning, and transformative game design. This allowed us to delve into game design's technical and transformative aspects. We also reviewed commercially released or published games promoting empathy, health, and awareness related to LGBTQ+ issues. This helped us gauge the current landscape and identify innovative design solutions that align with our objectives.

Our research spanned from January to June 2022. Given its expansive collection of scholarly publications, we predominantly utilized Google Scholar as our primary research portal. To ensure our research's breadth and depth, we consulted specialized databases such as APA PsychNet and PubMed. By diversifying our search, we aimed to capture a holistic and multidimensional perspective on the potential of serious games in addressing acculturative stress within the Latine community.

1.2. Contributions

This paper explores the intersection of Latine culture with Self-Determination Theory and serious game design, focusing on intergenerational communication. Although there is a significant amount of research on behavior theory and serious games, there is limited research on serious games and acculturation. To the best of our knowledge, this paper is one of the first to examine Latine cultural norms in designing a framework for understanding how games can reduce acculturative stress.

There are four primary goals of this paper:

1. To provide a background on Latine cultural identity and the impact of acculturation on this minority community;

2. To examine modern behavior change theories and establish the motivation for intergenerational communication;

3. To examine and explore serious games that challenge assumptions;

4. To propose a framework on how to use serious games to stimulate conversation between a first-generation child and their parent.

2. Latine culture and the strain of acculturation

To understand the mental health crisis caused by acculturative stress, it is important first to understand the foundation of Latine cultural norms regarding sex and gender roles. These norms can lead to a disconnect in communication due to an intergenerational divide and a disconnection in identity between the Latine immigrant parent and their first-generation children.

2.1. Cultural norms on sex and gender

Latine culture is diverse, stemming from a rich background of socioeconomic, regional, and structural societal growth (Cauce and Domenech-Rodriguez, 2002). However, a common expectation among Latine families is that first-generation Latine children should behave according to their parent's cultural values (Cauce and Domenech-Rodriguez, 2002). Gender expectations and religious beliefs from Latine culture, along with its resulting parental guidance norms, influence the mindset of children on the topics of sex and gender, particularly for daughters (Villarruel, 1998; Ma et al., 2014; Velazquez et al., 2017). Latine mothers express the importance of virginity as a form of self-respect, leading to fewer conversations on sex and sexual health interventions (Villarruel, 1998; Velazquez et al., 2017). As a result, parents often place stricter rules on female adolescents regarding dating than male adolescents (Hovell et al., 1994). Because girls are taught to care for the family, the cultural value of familismo (family oriented) is placed heavily on them, and they are expected to find a partner who shares the same value (Flores et al., 1998).

There is a clear difference how Latine girls and boys are treated and expected to behave, starting with household responsibilities. Parents expect Latine girls to assist with indoor tasks such as cooking and cleaning, while they expect boys to handle outdoor chores (Raffaelli and Ontai, 2004). In addition, parents expect their daughters to adhere to traditional gender roles and expectations, such as dressing in a “feminine” way, not engaging in rough play, and being responsible for cooking and caring for the family (Raffaelli and Ontai, 2004). Children assigned female at birth are given higher restrictions vs. their male relatives regarding social activities or other outdoor privileges (e.g., going out after school, how late to stay out on school nights, getting a license to drive) (Raffaelli and Ontai, 2004). While gender role expectations have shifted in the US, many Latine parents still teach their children traditional views, impacting how they view themselves and their place in society (Huston and Alvarez, 1990). These gender expectations are not unique to Latine culture; they can be observed across many different cultures and races. However, in the Latine community, these expectations are reinforced by the values of machismo and marianismo (Cauce and Domenech-Rodriguez, 2002).

2.1.1. Machismo and marianismo in the community

The cultural concepts of machismo and marianismo perpetuate the Latine community's adherence to traditional gender roles (Sequeira, 2009). Machismo is a characterization associated with Latine men that emphasizes masculine behavior, values, and attitudes (Kauth et al., 1993). This can result in discriminatory acts against women and a belief that Latine men should treat women as inferior (Kauth et al., 1993). Latine men are presumed to act lustfully toward women and father male babies to appear as a macho man (Stevens, 1973). Alleged machistas are sometimes violent to their spouse and possibly other members of their household (Domenach et al., 1981). Additionally, those who identify as a machista often believe that their perspective should be the only one considered and may become combative with those who disagree (Stevens, 1973). Finally, society often expects macho men to consume large amounts of alcohol without becoming inebriated (Giraldo, 1972).

Marianismo, also known as Mariology, is the phenomenon toward Latine women to adhere a feminine role influenced by the religious figure of the Virgin Mary. Five characteristics comprise the marianismo phenomenon—familismo (family-oriented), virginity, subordination, keep to themselves to maintain harmony, and spirituality (Da Silva et al., 2021). Marianistas4 are often viewed as “semi-divine, morally superior and sp[i]ritually stronger than men” (Stevens, 1973). Latine women are taught from a young age to be nurturing and family-oriented, taking care of their families, husbands, and children, which satisfies the familismo trait (Castillo et al., 2010; Da Silva et al., 2021). They are expected to fulfill the man's domestic and sexual needs (Kauth et al., 1993), remain faithful (Castillo et al., 2010), and paradoxically, protect their virginity to maintain their honor (Stevens, 1973). Latine women are also expected to be forgiving to those who cause them pain, physically and emotionally, and show deference to their Latine husbands unconditionally (Stevens, 1973). This can lead to Latine individuals staying in an abusive relationship (Kulkarni, 2007). Not only must Latine women be compliant, but they must also honor the cultural value of respeto (respect) no matter what (Reyes, 2013). This ideology expects women to hold their tongues and avoid disagreements to preserve a harmonious relationship (Klevens, 2007). Lastly, it is the role of marianistas to strengthen the religious and spiritual growth of their family, as expected of a good wife and mother (Reyes, 2013).

The roles of machismo and marianismo are closely linked to traditional gender roles within families. While machismo parenting practices, such as authoritative parenting, can lead to positive outcomes for children (Hill et al., 2003), such as high self-esteem and self-confidence (Delgado, 2017), they can also negatively impact a father's involvement in care-taking and emotional nurturing (Glass and Owen, 2010). The community and upbringing of the Father influence their idealized parental role (Raffaelli and Ontai, 2004). Similarly, marianismo can lead to a reinforcement of feminine behaviors in daughters, and machismo reinforces masculine behaviors in sons (Raffaelli and Ontai, 2004). This can result in the belief, mentioned previously, that virginity is an honorable trait and is passed down between generations (Villarruel, 1998). Additionally, research has shown that mothers and fathers often communicate differently with their children based on that gender (Leaper et al., 1998).

The interplay between machismo and marianismo creates a dynamic where one reinforces the other. Machismo, which emphasizes traditional masculine characteristics such as dominance and virility, normalizes the corresponding traditional feminine gender role of marianismo, which includes being submissive, chaste, and dependent (Comas-Diaz, 1988). This reinforcement of gender roles can lead to a disconnect between first-generation children and their immigrant parents, as cultural norms may not align between the two generations. Understanding the concept of acculturation, or cultural norms, is key to understanding this divide.

2.2. Acculturation

“Acculturation is the dual process of cultural and psychological change that takes place as a result of contact between two or more cultural groups and their individual members”5 (Berry, 2015). In other words, customs, values, or beliefs may change within a group or an individual when two or more cultures come into contact and influence one another; this is mainly found within immigrant populations moving to a new society. Cultural influence and change can happen as a result of “colonization, military invasion, migration, [or] sojourning (e.g., tourism, international study, and overseas posting)” (Berry, 2015). The changes that could happen can be physical, biological, political, economic, and social at individual and group levels (Berry, 1991). Acculturation is particularly relevant in multicultural societies like the US, where one out of five children is a child of an immigrant (Hernandez et al., 1998). However, research on children's adaptation to different cultures can be inconsistent, with some studies showing maladaptation (Bashir, 1993), while others show adaptation (Harris, 1999) to cultural identity.

Berry et al. (1992) propose four distinct strategies of acculturation within an individual:

1. Assimilation occurs when a minority culture loses its identifiable characteristics (foods, beliefs, ideologies) and absorbs into a majority group it comes in contact with;

2. Integration, in which an individual adopts practices from the dominant culture while retaining its own culture;

3. Separation, in which an individual maintains their culture and rejects the adoption of the dominant culture;

a) Segregation, where the dominant culture can control and maintain the minority cultures;

4. Marginalization occurs when an individual (or a group) withdraws or is excluded from their traditional culture and the larger society's culture.

As Latine culture and its people enter the US, we can observe them undergoing acculturation. Latine culture's influence manifests in various aspects of American culture, such as food, fashion, and even language (Cole, 2019). Examples include Mexican American infused cuisines like Chipotle and El Pollo Loco; traditional Latine clothing items like Panama Hats, Ponchos, Ruana; and Spanish words like cilantro and siesta being increasingly used by Americans. Additionally, Latine culture has also been influenced by American culture, with Spanish speakers incorporating English loanwords into their conversation, such as “bye,” “parking,” “email,” chequear (to check), and beicon (bacon).

Acculturation can have both positive and negative effects at the group level. One example is the use of gender-neutral Spanish language terms in the US. Spanish linguistics are traditionally gendered, so the original word to describe a Latine or a group of Latines is Latino/s. As a push for gender-neutral language gains momentum in the US to be more inclusive to all gender identities (Wayne, 2005; Elrod, 2014; Moser and Devereux, 2019), as it should be, academics have begun to replace the word Latino with Latin@ or Latinx as an attempt to neutralize the gendered word (Slemp, 2020). Although the intention is good, this change of Latin@ and Latinx alienates Spanish-monolingual speakers (deOnís, 2017). The “@” in Latin@ does not have a concrete phonetic sound, and the “x” in Latinx cannot be pronounced as “x” is pronounced as a “j” sound in Spanish. The use of these new terms by the dominant culture (US) to define the submissive culture in research and education can be problematic as Latine monolingual speakers cannot even pronounce them (Patterson, 2017). An alternative solution is using the word Latine, which is gender-neutral, easy to pronounce, and widely adopted in Latin America (deOnís, 2017). Another example of poor acculturation is the celebration of Cinco de Mayo in the United States. People in the United States celebrate Cinco de Mayo more than people in Mexico, although it is a Mexican holiday (Carlson, 1998; Mendoza and Miranda, 2021; Moné, 2021). Although thought to be Mexican independence day, it is a commemorative regional holiday to celebrate the victorious win of the Battle of Puebla. People in the United States—who are typically not associated with Mexico in any way—use it as an excuse to celebrate and do stereotypical Mexican activities such as drink margaritas, eat tacos, and wear unpleasant mustaches, sombreros, and ponchos (Hofmann, 2012; Mendoza and Miranda, 2021; Moné, 2021). These examples show how acculturation can happen at the group level and the importance of understanding its potential consequences.

When acculturating, individuals may experience changes in behavior, such as learning or shedding traits and characteristics from their original and new culture (Berry et al., 1992). Any conflict during an individual's acculturative development can lead to acculturative stress (Berry, 1970), manifesting as mental health problems such as confusion, anxiety, and depression (Berry, 1976). Resolving the issue is not easily fixed by adopting or assimilating to a new culture. Children and adolescents, who tend to acculturate faster than their immigrant parents (Szapocznik and Hernandez, 1988), are particularly susceptible to acculturative stress due to differences in family values (Szapocznik and Kurtines, 1993).

In theory, as people challenge outdated stereotypical gender role expectations like machismo and marianismo, Latine immigrants who are acculturating should adopt and embrace egalitarian views on gender and sexuality, given the history of fighting for equal rights in the United States (Buechler, 1990). However, research found that Latine immigrants tend to maintain traditional attitudes toward gender (Bejarano et al., 2011) with men being more conservative (Bejarano et al., 2011). However, Latine immigrant women and those who immigrate from Mexico (Bejarano et al., 2011) are more accepting of these new expectations (Parrado and Flippen, 2005). Generations succeeding the immigrant generation tend to hold more egalitarian views as they have spent more time in the United States (Bejarano et al., 2011). As first-generation Latine children spend more time in the United States, they become exposed to diverse sexual and gender identities that may differ from the values taught by their parents.

2.3. Minority of a minority

The intersection of minority groups and Latine culture is an important aspect to consider when reflecting on the impact of machismo and marianismo on acculturative stress. By taking inspiration from accessible design, Nakamura highlights the importance of including sub-communities in the design of adaptive technologies (Nakamura, 2019). Nakamura notes that advances in machine learning algorithms have been made possible by the increasing accessibility of big data and computing power. However, these algorithms are susceptible to a “white guy problem,” where the training data is not diverse regarding race and gender (Crawford, 2016). This leads to software that mislabels people of different races and those with disabilities, resulting in instances of algorithmic racism6 (Crawford, 2016; Nakamura, 2019) and loss of economic value. Marginalization and segregation can occur when research only focuses on the dominant community and leaves vulnerable groups behind. In order to avoid these kinds of issues, it is crucial to include diverse perspectives in research and development, which benefits not only historically marginalized communities but society as a whole (Nakamura, 2019). Therefore, understanding the complexities of minority groups within Latine culture is essential in achieving this goal.

2.3.1. LGBTQ+ Latine

In 2013, New Mexico, California, and Texas were home to approximately one-third of Latine same-sex couples, and it was estimated that there are 1.4 million LGBTQ+ Latine individuals living in the United States (Gates and Kastanis, 2013). However, these statistics are likely underestimations, as many LGBTQ+ individuals may choose not to disclose their identity. Additionally, people between the ages of 18–29 are three times more likely to identify as LGBTQ+ than seniors (Gates and Newport, 2012). Despite being a sub-group within a minority population, the number of individuals, 1.4 million individuals, makes it a significant population to consider.7

The LGBTQ+ Latine population faces challenges related to Minority Stress Theory, which suggests that sexual minorities are negatively impacted by stigmatization and discrimination in their cultural or social environment (Meyer, 2003). This theory is especially relevant for the intersecting communities of LGBTQ+ and Latine individuals (Fernández, 2016), as they face marginalization within their communities and families (Ryan et al., 2010). LGBTQ+ Latine and other underrepresented races have a higher risk for suicide attempts than white LGBTQ+ folks (Meyer et al., 2008). Many LGBTQ+ Latines, especially first-generation individuals, fear rejection or negative reactions if they reveal their identity to their families (Human Rights Campaign, 2012; Ocampo, 2014). This fear is often rooted in cultural gender norms associated with the machismo and marianismo phenomena (Merighi and Grimes, 2000). Lack of parental support can also lead to worse health outcomes for LGBTQ+ individuals (Needham and Austin, 2010). As an example, Alfred Magallanes, a gay Latino, faced difficulties in developing his sexual identity in the absence of resources and a supportive community during his time in high school and community college (Magallanes, 2012).

A 2012 survey revealed that 37% of LGBTQ+ Latine families were not accepting of LGBTQ+ sexual orientations, while 57% reported being accepting (Human Rights Campaign, 2012). Religion is a factor that affects Latine parents' mixed reactions to their child's LGBTQ+ identity (Barnes and Meyer, 2012), with 83% of Latine affiliated with Catholicism, Protestantism, or other religions (Taylor P. et al., 2019). Fernández's 2016 study found that Latine parents' perspectives on LGBTQ+ can improve over time after their child comes out. However, the parents often do not share this information with other family members due to worries of negative responses (Fernández, 2016). That same study found that Latine parents did not know any services to help them understand their child's LGBTQ+ identity, but they would find parent counseling and parents of LGBTQ+ support groups beneficial (Fernández, 2016). A healthy relationship between a parent and an LGBTQ+ child provides a safe and supportive environment to develop their identity (Ryan et al., 2010; Bregman et al., 2013). In a 2012 survey, the top three things that LGBTQ+ Latine hoped for were a “change in others” understanding, tolerance, and/or hate of LGBT people, [a] change related to the parents or family situation, and [a] change related to their honesty and openness about their sexual orientation” (Human Rights Campaign, 2012).

Therefore, it is crucial to develop new resources that can promote intergenerational communication toward and challenge the cultural gender roles (such as machismo and marianismo) that limit personal identity. This can be achieved by fostering supportive and safe relationships that encourage the growth of inclusive perspectives.

2.4. Reflections on culture

To summarize this section, first-generation Latine children are expected to conform to the cultural values of machismo and marianismo (Cauce and Domenech-Rodriguez, 2002) enforced by their parents. However, the acculturation process (Berry, 2015) can expose them to new attitudes on gender and sexuality that conflict with the values they grew up with. This can lead to acculturative stress (Berry, 1970), especially if a first-generation Latine explores their LGBTQ+ identity that differs from their parents' cultural background. To avoid rejection, closeted first-generation Latine may become distant from their parents (Gerena, 2021), and their health suffers because of discriminatory environments (Ryan et al., 2009, 2010). Having a supportive environment from their parents would make self-discovery easier for Latine children (Ryan et al., 2010; Bregman et al., 2013). The Latine cultural value of familismo (family-oriented) can be leveraged to facilitate conversations and create a supportive environment.

Supporting Latine immigrants and promoting intergenerational communication can help reduce stigma against LGBTQ+ Latine and create a stable environment for all generations to grow together. Involving both generations, particularly those in marginalized positions such as LGBTQ+, is vital in creating resources that foster this type of communication. Future research should consider including both of the generations discussed in this section and other subsequent generations. The goal is to challenge cultural assumptions and norms and strengthen the bond between generations for a more positive relationship. Before identifying the means of developing new resources, it is essential to understand how people are motivated to pursue this intergenerational dialogue.

3. Motivation and behavior change

This section examines modern behavioral theories concerning motivation toward understanding the psychological needs to support Latine communities in sparking conversations to reduce acculturative stress. It focuses on self-determination theory, intrinsic motivation, behavior change model, and methods of researching motivation. Behavior change theories are approaches to understanding change in human behaviors in health, education, and more.

3.1. Self-determination theory

Rooted in psychology and education, the Self-determination Theory (SDT) emerged as a macro-theory on human motivation and behavior. Against the backdrop of a shifting understanding in psychology, this theory emerged to delve deeper into the inherent growth tendencies and innate psychological needs.

At its core, SDT postulates three essential psychological needs—competence, autonomy, and relatedness—vital for individuals to cultivate new habits and alter perspectives (Deci and Ryan, 2013; Ryan and Deci, 2017a).

• Competence denotes the proficiency and aptitude to perform a task or activity effectively;

• Autonomy encompasses the freedom to make one's decisions and choices;

• Relatedness signifies the inherent desire for interpersonal connection and belonging.

The crux of SDT consists of these three intertwined needs, asserting that individuals can flourish and evolve when these needs are fulfilled.

SDT's underpinnings are twofold: Firstly, there is an inherent human tendency to pursue growth and understanding, and secondly, the idea that intrinsic factors, such as the quest for knowledge or independence, motivate this growth. However, external environments can influence and shape these intrinsic motivators over time (Deci and Ryan, 1985). This duality is encapsulated in the concepts of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, which are elaborated upon in subsequent sections.

Numerous studies across diverse fields like health promotion (Williams et al., 2006; Fortier et al., 2012; Teixeira et al., 2012), therapeutic interventions leading to behavioral shifts (Ryan and Deci, 2008; Britton et al., 2011), and the cultivation of human connections (La Guardia and Patrick, 2008; Deci and Ryan, 2014) suggest SDT's applicability and robustness.

When broaching the importance of intergenerational communication and the intricacies of navigating sensitive relational dynamics, SDT emerges as a particularly relevant guide. The intrinsic motivation grounded in autonomy and relatedness becomes paramount for fostering satisfying relationships, whether romantic, familial, or platonic (Deci et al., 2006; La Guardia and Patrick, 2008; Lynch et al., 2009; Van Lange et al., 2011). These principles apply to romantic bonds and resonate deeply with close friendships and familial ties, underscoring the universality of SDT's tenets. Ultimately, it all starts with intrinsic motivation.

3.1.1. Motivation

Motivation is the cornerstone of understanding why individuals act in certain ways. Rooted in psychological and behavioral sciences, motivation studies have been instrumental in decoding human behavior, tracing back to foundational work in early experimental psychology (White, 1959). Without any external drivers, humans innately possess a curiosity, a playfulness, that compels them to explore and learn. This is evident from the observations made in developmental and cognitive psychology, which emphasize the innate human tendencies to seek challenges and new experiences (Ryan and Deci, 2000, 2017b). Over the years, the field of psychology has witnessed the emergence of various theories that delineate the nuances of motivation. The duality of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation stands paramount among these.

Intrinsic motivation emanates from the human tendency to engage in activities for the sheer pleasure and satisfaction derived from the act itself (Deci and Ryan, 1985; Ryan and Deci, 2017b). Cognitive Evaluation Theory (CET), stemming from the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) school of thought, delves deeper into intrinsic motivation. CET posits that external factors can augment or diminish intrinsic motivation. Rooted in cognitive and social psychology, CET asserts the paramountcy of autonomy (or free choice) and how external factors like positive feedback can enhance intrinsic motivation. In contrast, negative feedback or competition may stymie it (Deci, 1971; Zuckerman et al., 1978). Thus, intrinsic motivation is not an isolated interplay but deeply embedded in the broader dynamics between the individual and their environment (Ryan and Deci, 2000, 2017b).

Conversely, extrinsic motivation is driven by external stimuli, often manifesting as rewards or external pressures (Deci and Ryan, 1985). As one navigates through life's stages, the interplay between intrinsic and extrinsic motivations evolves, often marked by increasing external demands, like educational pressures or professional responsibilities (Ryan and Deci, 2000). Within the Self-Determination Theory framework, the Organismic Integration Theory (OIT) elaborates on the spectrum of extrinsic motivation. Particularly, it examines the nuanced transformation of external motivations into self-driven motives—a process termed internalization. Understanding OIT is crucial, especially when considering acculturative stress in Latine communities where external societal pressures and intrinsic cultural values often intersect.

The very foundation of intrinsic motivation can be traced back to Robert W. White's pioneering concept of “effectance motivation” (White, 1959). Drawing from experimental studies on animal motivation from the early 20th century and inspired by Woodworth's idea of “competence” from 1958, White theorized the inherent human need to impact one's environment effectively. This idea blossomed into the rich tapestry of intrinsic motivation studies that we have today.

Given the salience of intrinsic motivation in navigating intergenerational relationships, particularly in Latine communities grappling with acculturative stress, we shall underscore its nuances in this article. But, before we delve deeper, it is pertinent to understand the intricacies of behavior change introduced through the Transtheoretical Model.

3.2. Transtheoretical Model

Various models can be used to understand the behavior change process, but this section will focus on the Transtheoretical Model (TTM). Rooted in the realm of health psychology and behavioral therapy, TTM, also dubbed as the Stages of Change Model, stands out as a holistic approach toward understanding the trajectory of individual behavior modification (Prochaska and DiClemente, 1982; Prochaska and Velicer, 1997).

At its heart, TTM stems from a combination of experiential and behavioral processes, encapsulating the myriad challenges and strategies that individuals encounter as they embark on transformative journeys be it for health, mental wellbeing, or personal growth. Such goals can be as ubiquitous as a New Year's resolution or as specific as curbing alcohol intake.

TTM posits six sequential stages detailing an individual's path to behavior change:

1. Precontemplation, where individuals remain oblivious to or in denial of problematic behaviors, envisaging no imminent change (within 6 months);

2. Contemplation, marking the individual's acknowledgment of the issue, weighing the pros and cons of initiating change;

3. Preparation, signifying a proactive stance toward imminent change (in the ensuing month);

4. Action, wherein individuals have actively amended their behavior, striving for sustenance;

5. Maintenance, a testament to behavior change resilience, sustained for over half a year, characterized by:

(a) Diminished propensity to revert to previous behaviors.

6. Termination, the pinnacle of behavioral transformation, where old temptations wane, ushering in unyielding self-efficacy.

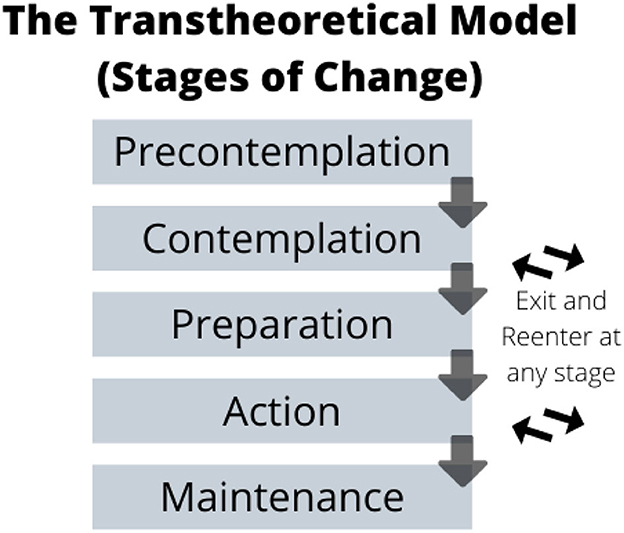

The cyclical nature of TTM, illustrated in Figure 1, underscores the reality that individuals can oscillate between stages, underlining the non-linear, often tumultuous journey of behavior change. Notwithstanding the allure of the Termination stage, the unpredictability of life's events and intrinsic human tendencies often make the preceding stages more germane, hence the research emphasis on them (Prochaska and Velicer, 1997).

Figure 1. This is the Transtheoretical Model, also known as the Stages of Change Model. This figure shows the model in a linear progression without the last stage—termination. Figure based on Prochaska and Velicer's (1997) theoretical framework.

TTM's versatility is evident in its successful applications across diverse arenas, encompassing health interventions (Marcus and Simkin, 1994; Bridle et al., 2005; Mostafavi et al., 2015), addressing intimate partner violence (Burke et al., 2001, 2004), therapy regimes (Brogan et al., 1999; van Leer et al., 2008), and numerous others (Lach et al., 2004; Horwath et al., 2010).

In the context of our research on serious games for alleviating acculturative stress in Latine communities, understanding the behavioral stages outlined by TTM becomes pivotal. By identifying the stages most pertinent to the target audience, game designs can be tailored to resonate more deeply, facilitating smoother transitions through stages of change and fostering a more sustainable behavioral impact.

3.3. Reflections on motivation

To summarize this section, the theory of Self-Determination Theory (SDT) on human motivation can help explain the psychological needs for a person to change perspectives and behaviors (Deci and Ryan, 2013; Ryan and Deci, 2017a). A key emphasis of SDT is identifying innate psychological needs, namely competence, autonomy, and relatedness, which are essential factors driving intrinsic motivation. This theory emerged as a counter-response to behaviorist theories, advocating that external rewards and punishments are not the sole drivers of behavior. Instead, SDT suggests that aligning external factors with internal needs can foster lasting behavioral change and personal growth. Considering Latine intergenerational relationships, SDT offers insights into understanding the intrinsic motivations behind behavior changes within these relationships. For instance, addressing psychological needs can bridge the communication gap and mitigate the effects of acculturative stress, making SDT particularly apt for our research context (Deci et al., 2006; La Guardia and Patrick, 2008; Lynch et al., 2009; Van Lange et al., 2011).

On the other hand, the Transtheoretical Model (TTM) is grounded in health psychology, examining the stages of change individuals undergo while modifying behaviors (Prochaska and Velicer, 1997). Its conception sought to unify disparate theories of therapy and behavioral change, thereby offering a comprehensive framework for understanding behavior modification. However, it is pertinent to note that TTM is linear and often reactive, addressing behavioral shifts only once they surface as substantial issues—it does not consider social contexts, so this model is for an individual who is going through a behavior change without any disruptions (e.g., external reasons such as money, work, friends, family, etc.) and has a clear plan for their goal—not everyone has a straightforward course. Another issue with the model is that there is no clear indicator that someone has passed onto the next stage, thus making it hard to tell where a person is in the behavior change process concerning the model. As stated before, although the termination stage is the goal when attempting to change a behavior, that is not a realistic stage for a human being as life continues. Therefore, the “Maintenance” stage is the more reasonable goal for a person to reach as the individual will sustain the new behavior until they relapse.

The reactionary mentality has significant issues and burdens on healthcare, with proponents calling for moving away from the “fixing it” mentality to supporting healthy living proactively (Hudson, 2003; Waldman and Terzic, 2019). Applying this paradigm, our research posits that proactively addressing the onset of acculturative stress through tailored interventions, such as serious games, can potentially preempt the exacerbation of stress and its ramifications in the Latine community (Turner and Marino, 1994; Rivera, 2007; Rothe and Pumariega, 2018). Specifically, in the case of Latine intergenerational relationships, there is an opportunity to proactively address acculturative stress and build a stable communication through serious games or similar resources.

4. Serious games and gamification

Serious Games is a term used to describe games with a significant purpose beyond entertainment (Djaouti et al., 2011). In behavioral health, they serve as innovative tools for intervention and support. To share some examples, serious games have been used for various purposes, such as training or learning in areas such as behavioral health (Duval et al., 2018; Hurd et al., 2019), physical therapy (Elor et al., 2018, 2019), and education (Holloway et al., 2012; Thang, 2018; Conde, 2020; Conde et al., 2020). While games often receive criticism for their potential negative impacts (Djaouti et al., 2011; Grossman and DeGaetano, 2014), designing them with an educational or therapeutic focus can render them effective and enjoyable. Specifically in the Latine communities, where acculturative stress can be prominent, serious games offer a promising avenue for providing culturally sensitive and engaging therapeutic interventions. These games not only serve as a medium of education but also as a means of engaging individuals in therapeutic activities in an enjoyable manner (Abt, 1987). They provide a safe environment for players to navigate and learn from diverse situations, proving to be a cost-effective and less time-consuming alternative to traditional methods, and play a pivotal role in skill development (Corti, 2006).

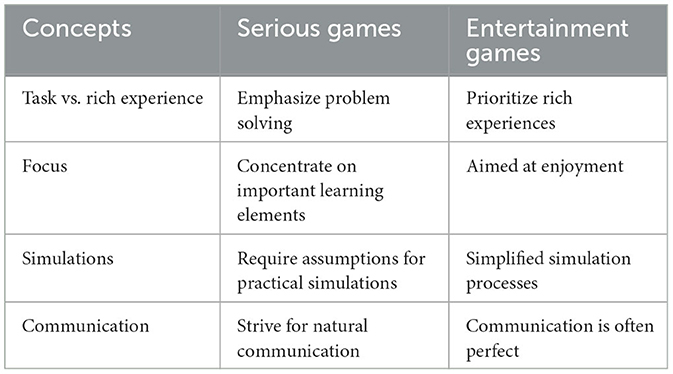

There are a few key differences between serious games and entertainment games, as shown in Table 1, which describes how a game can fall into each category (Susi et al., 2007). Serious games can have various impacts on the player, including physiological, social, educational, informational, and motor skill/spatial effects (Susi et al., 2007). There are several taxonomies of serious games (Laamarti et al., 2014; De Lope and Medina-Medina, 2017), with commonalities including identifying the application of the game (e.g., education, health, etc.), modality (how the player experiences the game through the senses), and the way it can be played (what platform is the game played on). Serious games are slowly gaining recognition in academia, with numerous conferences, journals, and organizations dedicated to their development and applications (Susi et al., 2007). For instance, the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) Digital Library published more than 8,000 serious games-related publications in 2021 alone [The Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) Digital Library (2021–2022)].

Table 1. Table providing the differences between serious and entertainment games (based on Susi et al., 2007).

Serious games can help individuals understand and experience different perspectives and recognize themselves in various situations (Ryan and Deci, 2017c). This can be achieved through understanding motivation in games, flow theory, gamification, and examining examples of games that challenge assumptions. We can apply serious games to address acculturative stress by exploring these aspects.

4.1. Games and motivation

Games allow players to immerse themselves in new situations and gain new perspectives (Ryan and Deci, 2017c). Games have satisfied the psychological needs for competence, autonomy, and relatedness, and the “immediacy, consistency, and density” make them enjoyable and engaging (Ryan et al., 2006; Ryan and Deci, 2017c).

Competency, as a reminder, refers to the ability to perform a task or activity efficiently (Ryan and Deci, 2017a). Games meet this need by implementing different difficulty levels for people to play—easy, normal, hard, and sometimes master (e.g., Kena : Bridge of Spirits and Beat Saber), numerous levels as in Level 1, 2, 3, 4, etc. (e.g., Toy Blast! and Candy Crush), or ranking systems to show each level of mastery (e.g., Call of Duty and Halo). Players feel competent when they successfully complete a difficult game task using their accumulated skill set (Ryan and Deci, 2017c), similar to playing a sport (Yim and Graham, 2007; Berryman, 2010; Glännfjord et al., 2017). The clarity of goals (e.g., higher scores, quests, solving puzzles, and so on) also contributes to the competence satisfaction (Ryan and Deci, 2017c). The game's difficulty level must be just right to ensure a steady flow of play; this concept will be further discussed in the next section (Nakamura and Csikszentmihalyi, 2014).

Intrinsic motivation also contributes to satisfying the competence need (Tyack and Mekler, 2020). Positive feedback can stimulate intrinsic motivation (Deci and Ryan, 1980); it is common for games to implement granular (e.g., sound effects that you did something well), sustained (e.g., a progress bar), and/or cumulative (e.g., a final high score) feedback for the player (Ryan and Deci, 2017c). Games often include features such as points, badges, scores, and other incentives to provide positive feedback (Pierce et al., 2003; Nagle et al., 2014; Taylor S. et al., 2019). However, rewards can diminish intrinsic motivation (Deci et al., 1999), thus making the rewards a conflicting feature (Lyons, 2015) and may not always enhance the player's experience (McKernan et al., 2015) (e.g., Sackboy: A Big Adventure's sticker book).

The next aspect is autonomy, which refers to the ability to make choices and decisions independently (Ryan and Deci, 2017a). In video games, players are granted autonomy through features such as customization and personalization options (Kim et al., 2015; De Castro et al., 2019). For example, in Animal Crossing: New Horizons, players have the utmost control to redesign an entire island from the ground up. The player can choose where buildings go, the color scheme and patterns around every corner, and make the smallest customization to the avatar's phone case. Additionally, some games allow players to make choices in social interactions, such as the dialogue wheel in Mass Effect, allows players to choose different responses in conversation with a non-playable character (NPC). The dialogue wheel allows the player to choose different routes of Paragon (good interactions) or Renegade (bad interactions), therefore establishing different relationships to NPCs. Other games, such as Red Dead Redemption, offer open-world mechanics that allow players to explore and choose their own quests (Ryan and Deci, 2017c). In Red Dead Redemption 2, players can go around collecting different breeds of horses if they wish to. The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild has a linear plot for players to follow and fulfill while also adopting open-world mechanics. Players can make their own adventure by accomplishing side quests such as finding all collectables (900 “Korok Seeds”) or completing all puzzle dungeons (120 Shrines). When players have the freedom to make their own choices (e.g., customizations, dialogue control, and open-world mechanics), they experience greater enjoyment, immersion, and a sense of connection (Sundar and Marathe, 2010; Birk et al., 2016).

Finally, relatedness refers to the need for social connections. Multiplayer cooperative games, online or local, provide a connection between players working together to complete a quest (e.g., Guacamelee! 2) (Cole and Griffiths, 2007; Dabbish, 2008; Depping and Mandryk, 2017), while communication options during play also facilitate relatedness (Hostetter, 2011; Lew et al., 2020). There are many instances of how communication can be implemented into games: chatbox in Minecraft, avatar facial reactions in Rec Room, avatar physical reactions in Portal 2, and audio-chat from microphones in Call of Duty. Players can also form parasocial relationships with NPCs (Tyack and Wyeth, 2017; Bopp et al., 2019), developing attachments and experiencing real emotions. For example, gamers have honest, deep reactions to beloved characters from a narrative twist from The Last of Us Part II (Byrd, 2020). Video games provide opportunities for players to connect with other players and NPCs (Whitbourne et al., 2013; Weissman, 2017).

In conclusion, video games have the potential to be highly fulfilling and engaging, satisfying the needs for competence, autonomy, and relatedness. When these three needs from the Self-Determination Theory are at their peak, player motivation is heightened, leading into the flow state.

4.1.1. Flow theory

Flow is a state of engagement that occurs when a person's activities are balanced with their skills and abilities (Csikszentmihalyi and Csikzentmihaly, 1990; Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). Flow theory, conceptualized by Csikszentmihalyi, captures these moments when individuals are entirely absorbed in an activity, blending cognitive and affective experiences (Csikszentmihalyi and Csikzentmihaly, 1990; Csikszentmihalyi, 2000).

The prerequisites of experiencing flow, as Csikszentmihalyi theorized, are: (1) Activities that challenge individuals yet align harmoniously with their skills, ensuring neither overwhelming nor under-stimulating experiences; and (2) Clear, well-defined goals complemented by immediate feedback, facilitating the individual's grasp on their progress (Nakamura and Csikszentmihalyi, 2014). Flow characteristics include deep concentration (Deci and Ryan, 2013), an altered perception of time, and satisfaction (Nakamura and Csikszentmihalyi, 2014), applicable across various contexts ranging from artistry and sports to academia and, notably, gaming.

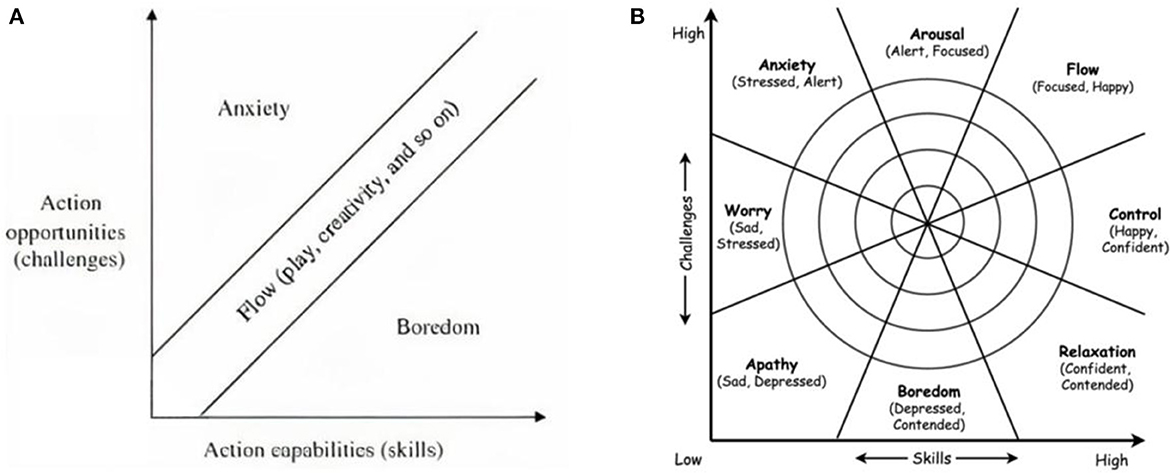

Csikszentmihalyi graphically represented Flow as a channel where balanced challenge and skill lead to a flow state (Csikszentmihalyi, 2000), as illustrated in Figure 2A. If the challenge becomes greater than the skills (above the channel), an individual will start to feel anxious. If the skills are greater than the challenge presented (below the channel), the individual will feel bored.

Figure 2. (A) Shows the original Flow Theory Model by Nakamura and Csikszentmihalyi (2014), where the depth of flow increases with higher challenge and higher skillset but any alteration to the balance could fall into Anxiety or Boredom. Reproduced with permission from SNCSC. (B) Shows the newer Flow Theory Model, where it is broken into eight quadrants and different channels surrounding the center of where the quadrants meet (reproduced from Yazidi et al., 2020, licensed under CC BY 4.0 International).

Researchers have identified a few weaknesses in Csikszentmihalyi's model, where it diminishes the quality of experience (Delle Fave and Massimini, 1988). To account for this, Delle Fave and Massimini redefined flow to be present when the challenge and skill are above average levels. Csikszentmihalyi later remodeled the Flow graph to include different possibilities for the state of consciousness (Mihaly, 1997), as shown in Figure 2B. According to this new model, depending on how challenging the task can become or if the skill set can match it, the person can get into different states of mind. It is comprised of eight quadrants—Flow, Control, Relaxation, Boredom, Apathy, Worry, Anxiety, and Arousal—with rings coming out from the center point to indicate the intensity one can feel in each state. Flow theory has been widely studied and applied in various fields such as the arts (Bakker, 2005; Wright et al., 2006; Cunha and Carvalho, 2012; Chilton, 2013), sports (Jackson and Csikszentmihalyi, 1999; Young and Pain, 1999; Stamatelopoulou et al., 2018), writing (Gute and Gute, 2008; Zuniga and Payant, 2021), and games (Wan and Chiou, 2006; Sharek and Wiebe, 2011; Kiili et al., 2012; Salisbury and Tomlinson, 2016).

In gaming, Flow becomes “Game Flow,” enriching player experiences through elements of “concentration, challenge, skills, control, clear goals, feedback, immersion, and social interaction” (Sweetser and Wyeth, 2005; Sweetser et al., 2012). Notably, these elements do not uniformly resonate across all game genres, they generally signify player satisfaction (Sweetser and Wyeth, 2005).

In our research on acculturative stress in Latine communities, Flow and GameFlow theories take center stage. Games, by virtue of their design, have the potential to induce flow states, encapsulating users in engaging narratives and challenges. Leveraging this, we can craft experiences that resonate deeply with Latine players, facilitating enjoyment and fostering intergenerational dialogues. For instance, tailoring games that reflect Latine culture or history can bridge generational gaps, enhancing mutual understanding and alleviating acculturative stress.

However, it is worth acknowledging that the universal appeal of games might be partially encompassing (Quora, 2022). In such instances, gamification, integrating game elements into non-gaming contexts, offers an alternative to capture GameFlow's essence in more familiar environments.

4.2. Gamification

Gamification applies game-like features to non-game contexts to enhance skills, motivation, and engagement (Hamari, 2007). While traditionally used in fields like healthcare (Miller et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2017), education (Prensky, 2003; Caponetto et al., 2014; Khaleel et al., 2015; Saleem et al., 2021), and business (Perryer et al., 2016; Ferreira et al., 2017; Suh et al., 2017), its efficacy in fostering profound attitudinal or belief changes remains debated. The core of gamification lies in engaging users through mechanics such as points, leaderboards, achievements, and levels to enhance motivation (Hamari et al., 2014). This approach aims to satisfy the Self-Determination Theory's three core psychological needs: competence, autonomy, and relatedness (Suh et al., 2018).

While the number of video game players grows, with a rise during the COVID-19 pandemic (Entertainment Software Association, 2022), gamification's appeal remains distinct from the immersive experiences of video games. The challenge lies in adding game-like elements and meaningfully engaging users to achieve specific goals. For example, the badges provided by smartwatches, such as Fitbit, did not sustainably increase motivation (Deci et al., 1999; Garnett and Button, 2015). It is essential to differentiate gamification from serious games. Whereas gamification adds game elements to existing content, serious games employ typical game mechanics with specific purposes like training or education (Deterding et al., 2011). Given the distinction and potential limitations, the subsequent sections will focus more on serious games as they provide more immersive experiences, allowing players to embody characters, which might offer more promise in addressing acculturative stress in Latine communities.

4.3. Serious games that challenge assumptions

Some games challenge assumptions and focus on LGBTQ+ topics. Examples of these kinds of games are: slices of life on transgender awareness [One night, hot springs (npckc, 2018), Mainichi (Brice, 2012)] and awareness of LGBTQ+ love and discrimination [Another Dream (Pitcures, 2020), Queerskins: A Love Story (Szilak and Tsiboulski, 2018)]. Other kinds of games are raising awareness on dating [InvestiDate (Harrison, 2022)], mental health [Homestay (Smith, 2018)], and gender and race [Sweetxheart (Small, 2019)]. These games have received positive reviews, won awards, and have been praised for their awareness of sensitive subjects. For example, Homestay won the Games for Change award for Best XR For Change, Sweetxheart was nominated for Most Significant Impact Finalist, One night, hot springs had “Overwhelmingly Positive” reviews (1,946), and Another Dream won Best XR for Change Experience in 2020. These games have intuitive features, are easy to follow, and are relatable. Homestay is a notable game example of mental health and acculturation in Canada, but this interactive narrative can only be experienced with virtual reality (VR) technology. However, a noted limitation is the accessibility of some of these experiences. For instance, Homestay's narrative is exclusively available through virtual reality (VR) technology, creating a barrier for those without VR access.

4.4. Reflections on games

Engaging with the current literature reveals an inherent tension in the domain of serious games. A prevailing criticism centers around the 'fun' aspect or the perceived lack thereof in such games (Deterding et al., 2011). This challenge is pivotal, as it may deter users from fully engaging, thereby hindering the intended behavioral or cognitive impacts. As suggested by the idea of gamification, one solution is to integrate game-like elements into existing non-game contexts, offering a potentially more viable alternative to developing an entirely new game (Deterding et al., 2011).

Serious games can potentially benefit players through training or learning (Djaouti et al., 2011). They provide a safe environment for players to experience new situations and perspectives (Corti, 2006; Ryan and Deci, 2017c), satisfying psychological needs as defined by the Self-Determination Theory (Ryan et al., 2006; Ryan and Deci, 2017c). This leads to a state of GameFlow and motivation to continue playing (Sweetser and Wyeth, 2005). Although there is a wide audience for games (Entertainment Software Association, 2022), not everyone considers themselves a fan (Quora, 2022). As a solution, gamification elements can cater to individuals who enjoy playful elements without full digital games.

We can use principles of serious games, gamification, and motivation to improve intergenerational communication through media creation. Current games that challenge assumptions and raise awareness, such as One night, hot springs (npckc, 2018), Mainichi (Brice, 2012), Homestay (Smith, 2018), and more, can serve as inspiration. This is just a small sample of commercially and academically available games that can be used for brainstorming suggestions. By exploring serious games and gamification, we can create media to help reduce acculturative stress.

5. Toward games that challenge assumptions in the Latine community

Historically, the acculturation process for Latine-Americans has been a turbulent journey shaped by societal norms and expectations. As we delve into the intricate relationship between Latine-American acculturation, behavior change, and serious games, we recognize serious games' profound potential to alter this trajectory. This section takes a critical stance to outline the evolution of these three themes and presents a design framework that reduces acculturative stress through a participatory research process.

5.1. The power of serious games: changing thoughts, assumptions, and beliefs

Games are not merely forms of entertainment. They shape cognitive processes, influence players' emotions, and cultivate understanding and empathy. By leveraging agency principles, games allow players to make choices, resulting in empowerment and behavioral change (Gee, 2008). Through embodied cognition, players gain experiential understanding by taking on roles that might be different from their own, promoting empathy and perspective-taking (Wilson, 2002). The nature of situated learning in games allows learning in context, fostering an authentic understanding of cultural nuances (Lave and Wenger, 1991). These elements, combined with the ability to weave cultural narratives and the displacement mechanism of games, create a medium that can challenge and transform deeply ingrained beliefs.

5.2. Considerations for serious games around acculturative stress

The cultural tapestry of the Latine-American experience has been woven with threads of resilience, diversity, and adaptation. The history of Latine-American acculturation is deeply rooted in gender identity and sexuality, underscoring the strain of acculturation (Berry, 1970). The perpetuation of traditional values like machismo and marianismo serves as both a cultural anchor and a source of discord (Cauce and Domenech-Rodriguez, 2002). Understanding the strain of acculturation demands a deeper dive into the effects of these values on first-generation Latine-Americans. The inadvertent pressure from parents to conform can drive wedges in families, intensifying feelings of alienation and leading to potential mental health implications (Berry, 1976; Gerena, 2021).

Why have serious games not been a primary method to address this acculturation challenge? The potential of serious games in this context is twofold: firstly, to challenge these norms, and secondly, to provide a bridge for intergenerational dialogue. Grounded in the Self-Determination Theory, the success of these games hinges on meeting the triad of psychological needs: competence, autonomy, and relatedness (Deci and Ryan, 2013; Ryan and Deci, 2017a). The Transtheoretical Model further nuances our understanding by highlighting the stages individuals navigate as they challenge deeply ingrained norms (Prochaska and DiClemente, 1982; Prochaska and Velicer, 1997). The overarching question remains: How can serious games, steeped in cultural understanding, successfully navigate these complex waters? Given the potential of serious games to create safe experiences (Corti, 2006; Ryan and Deci, 2017c), why have they yet to be fully embraced by the Latine community? Critical examination suggests that while games offer a platform, the cultural intricacies of the Latine community have not been adequately represented or understood.

5.3. Recommendations for game design

Building an effective serious game for the Latine community demands an intricate balance of cultural sensitivity and game mechanics. Experiences that resonate with the Latine community are not merely about creating a game; from our point of view, it is about creating a narrative that feels familiar, genuine, and empowering. In the context of this narrative review, we propose the following considerations for future game design and research:

1. Inclusivity from the outset: involve the Latine and LGBTQ+ communities from the ideation phase. This fosters a sense of ownership and ensures authentic representation.

2. Cultural nuances: the game mechanics should reflect cultural nuances. For instance, weaving in elements that echo familial bonds, traditions, and the duality of experiencing two cultures.

3. Learn from groundwork: many existing Latine organizations, such as Somos Familia and TransLatin@ Coalition, have laid crucial groundwork (CaliforniaLGBTQ, 2020). Collaborate with them to understand the community's pulse and needs.

4. Modularity: design games that are modular. Different modules can address varying levels of acculturative stress, allowing players to engage at their own pace and depth.

5. Language sensitivity: offer bilingual options or interweave Spanglish to resonate more deeply with the diverse linguistic backgrounds of the Latine community.

6. Feedback: regularly gather feedback and be open to iterations. The community's needs will evolve, and the game should mirror this evolution.

7. Accessibility: ensure that the games are accessible on various platforms and consider the socio-economic diversity within the Latine community.

Exploring these recommendations not only strives for a game that the Latine community can relate to but also paves the way for research in serious games to emerge as powerful tools for positive cultural and societal change. As such, engaging the Latine and LGBTQ+ communities is not just an option but a necessity. However, it is crucial to question: Do these initiatives achieve widespread impact? Are they leveraging the full potential of gamification? Our epistemic stance urges exploring these questions and emphasizes the integration of community voices in game design rather than mere consultation.

5.4. Proposing an acculturative game design thought framework

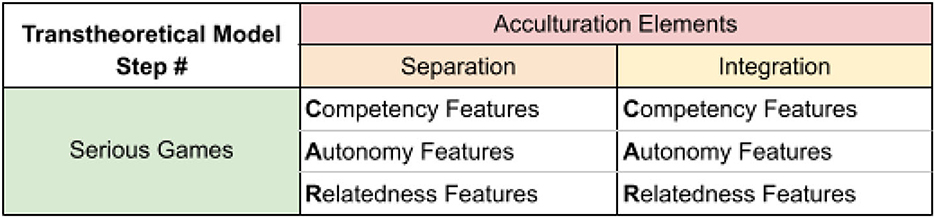

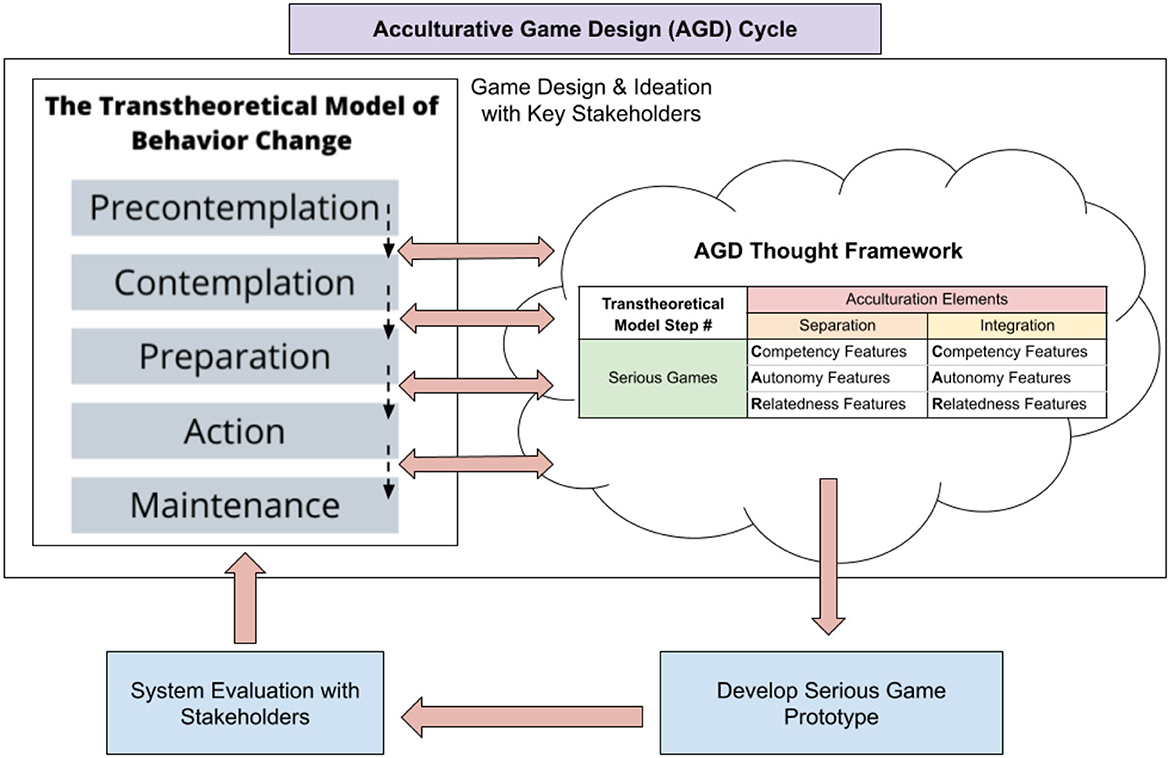

Our increasingly globalized world necessitates more adaptable tools for cultural understanding. To bridge our narrative review, we present the Acculturative Game Design (AGD) Thought Framework, depicted in Figure 3. This framework is a design tool and an epistemic stance toward understanding acculturation in the Latine community. It amalgamates the principles of behavior change with game design, pivoting on the strategies of Integration and Separation (Sam and Berry, 2010). A critical question for future researchers: How can this framework be used to design games that do not just entertain but empower the Latine community toward positive acculturation?

Figure 3. The Acculturative Game Design (AGD) Thought Framework, a participatory design tool for generating game features around stimulating intergenerational dialogues to reduce acculturative stress. The AGD Thought Framework integrates concepts of medium framing and acculturation toward generating game features inspired by Self-Determination Theory.

As illustrated in Figure 4, The AGD Thought Framework is intended to be used in participatory design practices (Elizarova and Dowd, 2017) and follows an iterative game design process. For example, one such experiment of AGD to discover elements of a serious game might look like the following:

1. Recruit a group of representative stakeholders, including the Latine community and LGBTQ+ from intergenerational backgrounds.

2. Conduct a workshop using the AGD Thought Framework with key stakeholders.

• During the workshop, participants are introduced to the concepts of Acculturation, Serious Games, and Behavior Change:

- Acculturation.

- Separation.

- Integration.

- Serious games.

- Precontemplation.

- Contemplation.

- Preparation.

- Action.

- Maintenance.

• Participants fill out the AGD table individually and then engage in group discussions.

• The process is repeated for all five stages of the Transtheoretical Model.

3. Analyze the workshop materials and generate suggestions for game mechanics.

4. Evaluate system prototype with stakeholders and repeat the cycle to make design improvements.

Figure 4. This is the AGD cycle. The AGD Thought Framework can be workshopped with stakeholders for each transition in the Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change. The materials from the workshop can be collected and analyzed to design a serious game prototype. Next, take the prototype, evaluate it with stakeholders again, and reiterate on the AGD Thought Framework.

In considering this thought framework for future research, we present the following considerations:

1. Theoretical underpinnings: the framework is deeply rooted in the Self-Determination Theory and the Transtheoretical Model. However, it is crucial to consider how the Latine cultural context interweaves with these theories. How can we ensure that the principles of competence, autonomy, and relatedness are universal and culturally specific?

2. Critical analysis: serious games have the power to reshape narratives, but they also risk perpetuating stereotypes if not designed with care. The question remains: Can a game genuinely capture the depth of the Latine experience without trivializing it? Furthermore, while games can serve as tools for dialogue, there is a pressing need to evaluate their effectiveness critically. Does increased game engagement equate to improved understanding and reduced acculturation stress?

3. Epistemic stance: our framework champions a participatory research approach, emphasizing the Latine community's role in co-constructing the game narrative. This stance recognizes the community not as mere research subjects but as partners in knowledge creation.

4. Holistic approach: addressing acculturative stress demands a two-pronged approach. On the one hand, the Integration strategy encourages a harmonious blend of cultural identities; on the other, the Separation strategy recognizes the potential challenges of this blending. Our framework challenges the binary nature of these strategies, prompting designers to recognize the fluidity of cultural identities.

5. Applying a media lens: in integrating the Self-Determination Theory, Transtheoretical Model, and acculturation elements, game designers must decide on the medium—Serious Games or gamified activities. It is not just about the mode of delivery but the depth of engagement and experience it can offer.

6. Future implications: as we put forward the AGD Thought Framework, it is essential to remain critical and adaptive. The Latine community is not monolithic; as the socio-cultural landscape evolves, so should our framework.

To summarize, the AGD Thought Framework serves more than just a thought experiment for game design; it's a call to action. A call for deeper engagement, encouraging critical introspection, and fostering collaborative creation. By harnessing insights from diverse generations, this framework addresses acculturative stress within communities, all through a united and collaborative process. At its core, this framework functions as an inaugural stepping stone, wielding the potential to guide discussions surrounding acculturation, serious games, and behavior change within the Latine community and beyond. This dynamic tool does not just offer its benefits later in the design journey—it is most powerful when employed early in the developmental process when ideas are still taking shape and the essence of the game is being discovered.

5.5. Limitations and future work

In examining the potential role of serious games in alleviating acculturative stress among Latine communities, it is essential to acknowledge certain limitations that warrant consideration. While our review encompassed an exhaustive analysis of ~200 relevant papers, it is prudent to recognize the existence of a broader landscape of literature concerning Latine-American acculturation, behavior change theories, and the growing field of serious games.

A noteworthy aspect requires a closer examination of the theoretical underpinnings that constitute our conceptual framework. The amalgamation of diverse theoretical constructs without a comprehensive grasp of their origins carries inherent risks, a point underscored by Miettinen's scholarly work (Miettinen, 2000). Miettinen astutely cautions against eclecticism, emphasizing the significance of grounding theories within a coherent and informed epistemological framework.

It is important to emphasize that we advocate for scholars to adopt our framework and to adapt and change it as they explore acculturative stress within the context of serious games. Our framework serves as a guiding scaffold for understanding and addressing acculturative stress through serious games, albeit one among multiple conceivable approaches. This framework holds potential in various applications, such as developing immersive “slice-of-life” games that amplify awareness regarding acculturative stress and its intersection with matters of gender identity and sexuality from the perspective of first-generation Latine individuals. Moreover, we posit the viability of extending the applicability of the AGD Framework to examine acculturative stress within different cultural milieus, thereby highlighting its versatility and cross-cultural relevance.

6. Conclusion

This article reviews the research on Latine-American acculturation, behavior change theory, and serious games, intending to propose a framework for reducing acculturative stress. We explore the pressures of Latine cultural values of machismo and marianismo on intergenerational Latine identity. Additionally, we consider strategies for behavior change and motivation by looking through the lenses of Self-Determination Theory and the Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change. Next, we explored the impact of serious games and gamification on supporting real-world challenges such as mental health and beyond. This review culminates in introducing the Acculturative Game Design (AGD) Thought Framework, which represents a new approach to facilitating intergenerational communication around Latine identity. While there is undoubtedly more work to be done, this article constitutes a first step in the innovative field of serious games around acculturation and provides a basis for future research.

Author contributions