- 1Research Department of Child Nutrition, University Hospital of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, St. Josef-Hospital, Ruhr University Bochum, Bochum, Germany

- 2Department of Anaesthesiology, Intensive Care and Pain Medicine, Ruhr- University Hospital Bergmannsheil, Bochum, Germany

- 3Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine, University Hospital Bonn, Bonn, Germany

- 4University Hospital of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, St. Josef-Hospital, Ruhr University Bochum, Bochum, Germany

Background: Breast milk is the best nutrition for newborns. Its composition is dynamic and adapted to the newborn’s individual needs. A variety of bioactive compounds, including bone-related molecules, have been described in breast milk. Osteocalcin (OCN) is a small non-collagenous, bone-derived protein. In its carboxylated form (cOCN) it plays a crucial role in bone metabolism and calcium homeostasis. The undercarboxylated form of osteocalcin (ucOCN) is suggested to have endocrine functions such as influencing neurotransmitter synthesis and glucose homeostasis. This study aimed to analyze whether the bone-related proteins cOCN and ucOCN are present in breast milk at different time points of the lactation phase and whether the amount is affected by lifestyle factors, such as dietary behavior, physical activity, BMI, age, or number of parities.

Methods: 98 mothers, aged 31.8 ± 4.7 years, participated in the study. Breast milk was collected at four points during the breastfeeding period (T1: 1–3 days postpartum (pp); T2: 7 days pp; T3: 14 days pp; T4: 3 months pp). Total protein, ucOCN and cOCN were analyzed by BCA (bicinchoninic acid) assay and enzyme immunoassay, respectively. Dietary habits, physical activity, and BMI were assessed.

Results: The median concentration of cOCN in relation to the total amount of protein decreased only marginally during the breastfeeding period (T1: 0.068 [0.021-0.207] ng/mg protein; T4: 0.045 [0.026-0.196] ng/mg protein), with total protein concentrations in breast milk decreasing. In contrast, the relative ucOCN concentration in relation to the total protein concentration was twice as high in the colostrum (0.125 [0.043-0.223] ng/mg protein) compared to mature breast milk (0.055 [0.028-0.091] ng/mg protein). The concentration of ucOCN in colostrum from primiparous women (0.138 [0.041 – 0.342] ng/mg protein) tended to be higher than the concentration in colostrum of multiparous women (0.062 [0.034 – 0.151] ng/mg protein, p = 0.094). This also applied for the cOCN concentration. Other lifestyle factors, e.g., physical activity, BMI, or age showed no associations with ucOCN concentrations in breast milk.

Conclusion: This study indicates that ucOCN and cOCN are components of breast milk. The function of both molecules in infants and mothers, still needs to be uncovered.

Clinical Trial Registration: https://www.bfarm.de, identifier DRKS00023072.

Introduction

Breast milk is the best nutrition for infants as it contains numerous nutrients required for optimal growth (1). The World Health Organization recommends to exclusively breastfeed for the first 6 months of life and to continue breastfeeding along with appropriate complementary feeding (2). Breastfeeding is associated with a reduced risk of infections and allergic diseases (3, 4). It protects from the development of diabetes mellitus type 2 and lowers the odds for obesity (5).

The composition of human milk is dynamic and changes during the lactation phase from colostrum to mature milk. It contains a wide range of nutrients, especially bioactive proteins (6). Furthermore, the composition varies inter- and intra-individually; it changes over the course of the day and can be influenced by maternal lifestyle factors, e.g., dietary habits (7–9). Although industrially produced infant formula has been optimized through constant research in recent years, it cannot yet fully imitate breast milk (10).

Breastfeeding is a major challenge for the maternal organism. Every day, 300 to 400 mg calcium is excreted into breast milk, the main source of which is the mother’s skeleton (11). Lactational bone loss is suggested to be a result of reduced estradiol levels found in lactating women that leads to an increased bone turnover, reflected by elevated bone resorption as well as bone formation markers such as osteocalcin (12, 13).

Human osteocalcin (OCN), also known as bone γ-carboxyglutamic acid-containing protein, is a small, non-collagenous protein consisting of 49 to 50 amino acids, synthesized and secreted by osteoblasts and odontoblasts, which is the most abundant non-collagenous protein in bone tissue (14). OCN plays a crucial role in bone metabolism and calcium homeostasis (15). There are two forms of OCN: the carboxylated OCN (cOCN) and the undercarboxylated OCN (ucOCN). The post-translational carboxylation occurs through a vitamin K-dependent carboxylase, which produces three γ-carboxyglutamic residues at positions 17, 21 and 24 in OCN (16, 17). Within the resorption lacunae of osteoclasts, the pH is low, which leads to the decarboxylation of osteocalcin and its release into circulation (18). ucOCN has been suggested to have endocrine functions in vivo, e.g., influencing neurotransmitter synthesis, which might lead to a reduction in anxiety and depression (19) or improving glucose tolerance by stimulating CyclinD1 and insulin expression in β-cells and adiponectin (20, 21). Furthermore, oral application of ucOCN in mice led to substantial increase of ucOCN in serum after 4 weeks with effects on insulin production and glucose utilization, suggesting that ucOCN can be resorbed partially from the intestine (22).

Breast milk contains a variety of bioactive compounds with immune modulating and growth promoting properties (23). These also include bone-related substances, such as osteoprotegerin, receptor activator of nuclear factor κ B ligand (RANKL) or cross-linked N-telopeptide of type I collagen (NTx), which might influence the function of the mammary gland as well as the growth and development of the neonate (24, 25). The aim of this study was to investigate whether another bone-related protein, cOCN and its undercarboxylated compound ucOCN, are also present in breast milk at different time points of the lactation phase.

Additionally, we aimed to identify maternal lifestyle factors with potential to influence the OCN level in breastmilk such as maternal body mass index (BMI), diet, or the number of parities, which have been shown to affect the composition of human breast milk per se (26, 27).

Methods

Study design and recruitment

Recruitment was undertaken by study personnel between November 2020 and November 2021. During this time, 100 women who were about to give birth or had just given birth were recruited in two large maternity units in Bochum (St. Elisabeth-Hospital) and Dortmund (Klinikum Dortmund), Germany. Two women withdrew consent shortly after participation.

For inclusion, the study subjects had to be at least 18 years old, fluent in German, willing to fully or partially breastfeed for at least 3 months, and own a freezer for short-term milk sample storage. Exclusion criteria were giving birth to a preterm infant (< 2500 g and/or < 37th week of gestation) and any form of diabetes (diabetes mellitus type 1, type 2 or gestational diabetes mellitus). As a reward for their participation, the participants received financial compensation of up to 30 € and an information booklet on child nutrition.

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The subjects were free to withdraw consent at any time. The study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and registered at the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS00023072). Approval was granted by the ethics committee of the Ruhr-University of Bochum, Germany (#20-7006.).

Sample processing and analysis

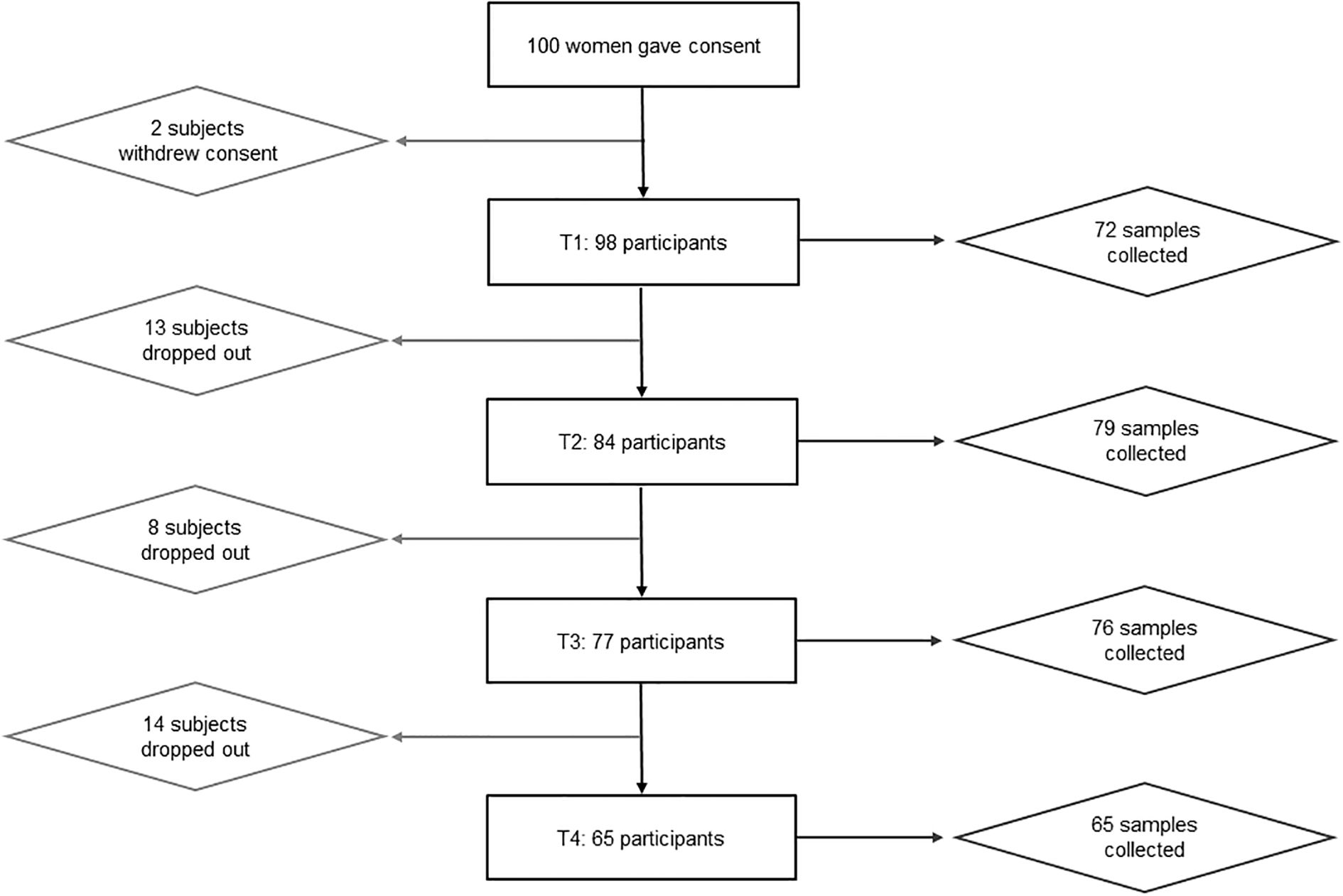

Breast milk samples were collected under standardized conditions at four-time points during the lactation period (Figure 1). Milk was collected between 8 am and 12 pm using an electric breast pump (Symphony®, Medela, Baar, Switzerland). It was essential that milk was pumped from the same breast for all time points, and mothers were instructed to fully empty the breast in the previous feed. Milk from that breast was pumped entirely, and an aliquot of 5 ml was stored at -18 °C until collection by the study staff. The remaining breast milk was available to feed the infant as needed. To ensure standardized conditions, the staff supported the study participants during the first sample collection. For the subsequent appointments, participants were free to collect the samples either in the presence of the study staff or on their own. If they chose to do it alone, the study staff was available by phone at any time.

Figure 1. Collection of milk. To ensure the collection of the 3 phases of breastmilk, 4 different time points were selected: T1 (colostrum) at 0–3 days postpartum (pp), T2 (transitory milk) at 7 ± 2 days pp; T3 and T4 (mature breast milk) at 30 ± 2 and 90 ± 2 days pp. At T1 breastmilk was collected at the hospital and the subjects were instructed into usage of the breastmilk pump. At T2 – T4 breastmilk samples were collected at home and immediately stored at -20 °C.

The samples were further processed after a maximum storage time of 7 days at -18 °C. Then samples were thawed, vortexed, and centrifuged at 1000 rpm at 4 °C for 10 minutes. Post centrifugation, the liquid phase was removed and transferred into a new tube; the fat phase was discarded, and the process was repeated once again. During this process, samples were kept on ice. The fat-reduced samples were then stored at -80 °C until further analysis.

Total protein was measured using a commercially available kit (BCA (bicinchoninic acid) Protein Assay Kit, Thermo Scientific™ Perice™, Rockfordt, USA). cOCN and ucOCN concentrations were analyzed using commercially available enzyme immunoassay (EIA) kits (#MK111 Gla-OC, #MK118 Glu-OC; Takara Bio Europe, France).

Data collection

To compare the measured cOCN and ucOCN concentrations, both values were adjusted with the total protein concentration.

The mother’s habitual diet, physical activity and health status were recorded at T1 and T4 using questionnaires from German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS) (28). Questionnaires also included questions regarding the mother’s age and school education. Mothers could choose between degrees Hauptschulabschluss, Realschulabschluss and Abitur, which corresponds to basic, secondary, and higher secondary education. Dietary habits were evaluated at T1 and T4 using the Healthy-Eating-Index (HEI), which is used to assess and quantify dietary quality. It compares the intake of 15 food groups (drinks, vegetables, fruits, fish, cereals, side dishes (potatoes, pasta, rice), nuts, milk and dairy products, cheese, eggs, meats and sausages, fat, sweets and snacks, sugary drinks and alcohol) with the German Nutrition Society (DGE) recommendations for a healthy diet (29). For 54 food items, mean consumption frequency (ranging from “never” to “more than 5 times per day”) over the last four weeks and mean portion sizes (e.g., teaspoons, tablespoons, cups, plates) were assessed. The score ranges from 0 (no adherence to recommendations) to 100 (highest adherence to recommendations) points (30). For further analysis, subjects were divided into tertiles according to their achieved HEI. As we expected lower influence of nutrition in participants with a HEI in the second HEI tertile, only the first tertile (= HEI low, HEI < 51.74) was compared to the third tertile (= HEI high, HEI > 58.45).

Furthermore, participants answered questions regarding their weight, height and physical activity at each time point. They were asked how often and for how long they had exercised on average per week over the last 4 weeks. Additionally, mothers were also asked how many days a week they were physically active to the point of sweating or getting out of breath and how long (in minutes) they were physically active on these days. Classifications of physical activity were based on the recommendation of the World Health Organization for pregnant and breastfeeding women to engage in at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity per week (31). Participants who engaged in at least 150 minutes of physical activity per week (exercising or sweating during other activities such as walking or housework) were considered physically active, and those who engaged in less than 150 minutes of physical activity per day were considered sedentary.

BMI was calculated from height and weight ((kg)/(height in m)2), and subjects with a BMI of ≥ 25 kg/m2 were considered overweight according to the WHO (32). Missing BMI values at T1 were supplemented with values from T2, if available.

To determine the influence of age on cOCN and ucOCN concentrations, the cohort was divided into a group < 35 years and a group ≥ 35 years of age, based on the age at which pregnancies are considered to be higher risk (33). Number of previous births was recorded and mothers were divided into primigravida (first pregnancy; miscarriages and abortions not considered) and multigravida (more than one delivery).

Statistics

SPSS version 29 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) was used for data analysis. Data was tested for normal distribution using Shapiro-Wilk test. OCN concentrations of different time points were analyzed using Friedman test for one-way repeated measures analysis of variance by ranks. Correction for multiple testing was performed using Bonferroni. Group differences of non-normally distributed data were analyzed using Mann-Whitney U test. Values of p < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Maternal characteristics

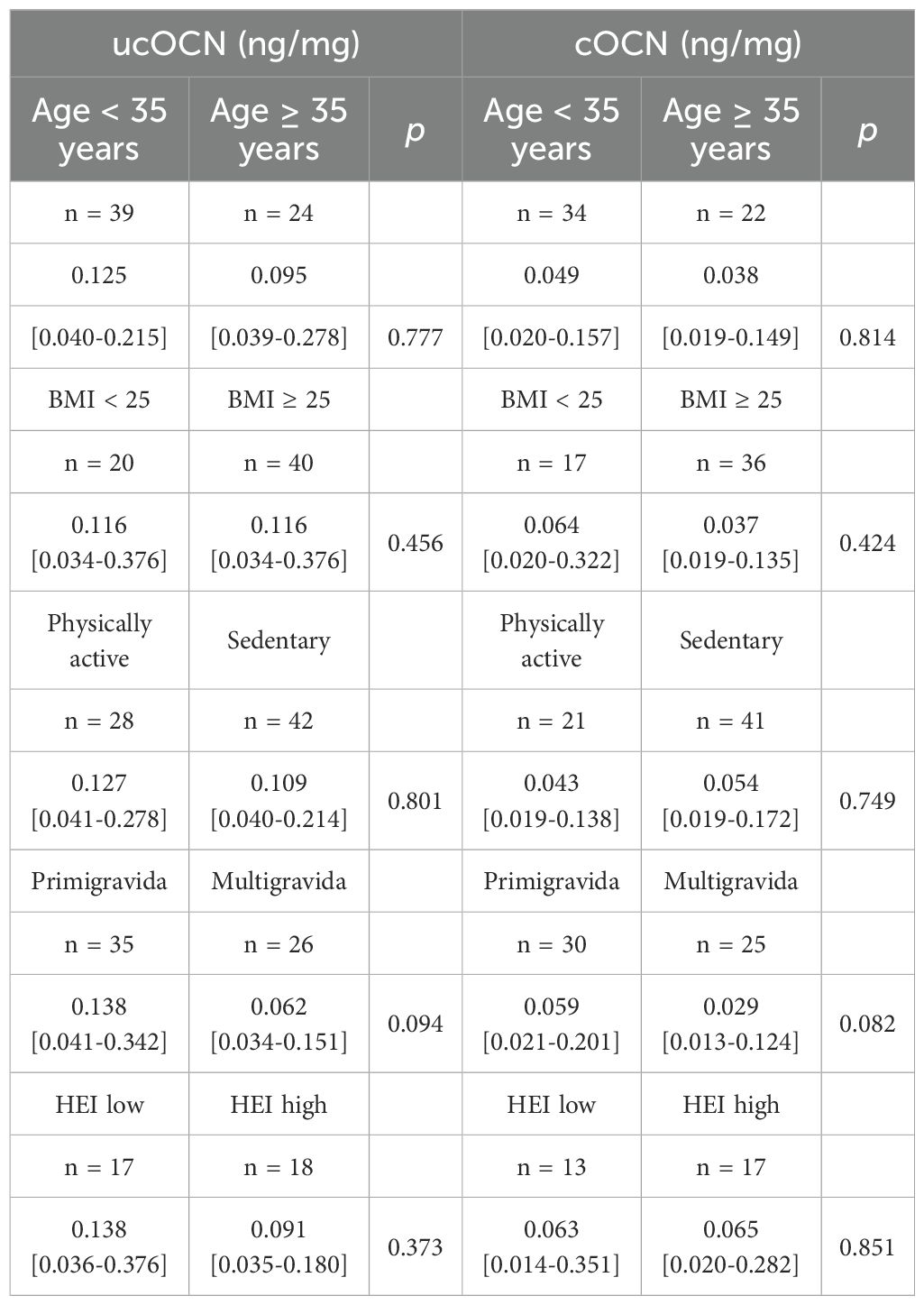

Out of the 100 mothers that were recruited, two withdrew their consent shortly after participation (Figure 2). Of the remaining 98 participants, 72 provided a milk sample at T1, 79 at T2, 76 at T3 and 65 at T4 (Figure 2). At T1, fewer samples were collected than at T2 due to issues with breastfeeding initialization or small sample volume (Figure 2). As 11 mothers were lost to follow up at T4, most comparisons were conducted with T3.

Figure 2. Flowchart showing participation. Out of 100 women that gave consent, only 65 participated until the end. Two participants withdrew their declaration of consent before the first appointment. Reasons for early termination of participation included, e.g., premature weaning, mastitis, discomfort during breastfeeding. At the first time point, only 72 out of 98 subjects were able to provide a breastmilk sample due to issues with breastfeeding initialization or too small sample volumes.

At the time of delivery, the participating mothers were between 21 and 42 years old (31.8 ± 4.7 years, Table 1), and for 55% this was their first pregnancy (primigravida). On average, mothers had gained 14.8 ± 5.8 kg during this pregnancy and had a mean BMI of 28.3 ± 6.7 at delivery (T1). 78% of mothers had attended higher secondary education, while 8% had basic education. Mothers achieved a HEI of 55.2 ± 9.3 at T1 and 52.3 ± 8.9 at T4 (Table 1).

OCN in breast milk

The concentration of cOCN in relation to the total protein concentration remained stable during the breastfeeding phase (Table 2), while ucOCN was almost twice as high (0.125 [0.043-0.223] ng/mg protein) in colostrum compared to the subsequent breastfeeding phases (p < 0.001 for all time points, Table 2). Similarly, the ucOCN/cOCN ratio was highest in colostrum and decreased during the breastfeeding phase (Table 2). Concentrations of total protein as well as protein-corrected cOCN and ucOCN from all participants without complete sample sets at all time points are displayed in Supplementary Table S1.

Table 2. Concentrations of total protein, carboxylated (cOCN) and undercarboxylated osteocalcin (ucOCN) over the course of lactation in mothers with complete sample sets.

Lifestyle factors and OCN in breast milk

At both time points (T1 and T3), the majority of study participants were physically active for less than 150 minutes per week, especially 30 days pp (71.1 ± 118 min; Table 1). ucOCN and cOCN concentrations in breast milk were not significantly different between physically active and sedentary mothers (Table 3, Supplementary Table S2). The same applied to participants with high HEI and low HEI.

Table 3. Concentrations of undercarboxylated (ucOCN) and carboxylated osteocalcin depending on selected lifestyle factors in colostrum (1-3 days postpartum).

ucOCN and cOCN concentrations were comparable between mothers with higher-risk pregnancy (≥ 35 years of age) and mothers < 35 years of age (Table 3, Supplementary Table S2). Furthermore, ucOCN and cOCN concentrations did not show any significant differences when comparing the BMI > 25kg/m2 group to the BMI ≤ 25kg/m2, neither at T1 nor at T3.

At T1, the protein concentrations of ucOCN and cOCN were slightly but insignificantly lower in multiparous women (ucOCN: 0.062 [0.034 – 0.151] ng/mg protein; cOCN: 0.029 [0.013 – 0.124] ng/mg protein) compared to primiparous women (ucOCN: 0.138 [0.041 – 0.342] ng/mg protein; cOCN: 0.059 [0.021 – 0.201] ng/mg protein). At T3 ucOCN tended to be lower in multiparous mothers (0.04 [0.02 – 0.06] ng/mg protein) than in primiparous (0.05 [0.03 – 0.10] ng/mg protein), but this difference also lacked significance (p = 0.056). At T3, this trend was no longer seen in cOCN (Supplementary Table S2).

Discussion

This study analyzed cOCN and ucOCN concentrations in human breast milk during the first 4 months of the breastfeeding period. While ucOCN was highest in colostrum and decreased in the following months, cOCN decreased only marginally over the course of lactation.

In 1993, Pittard et al. were the first to analyze total OCN in transitory breast milk of 11 women via radioimmunoassay method. However, total OCN concentrations were below 0.1 ng/ml breast milk (34), while we determined 0.094 – 13.02 ng/ml ucOCN and 0.057 – 10.09 ng/ml cOCN (both not adjusted for protein) in transitory breast milk (T2: 7 ± 2 days pp). An explanation could be differences in handling the milk samples. While Pittard et al. centrifuged once and discarded the cream, we first vortexed the samples and additionally centrifuged twice with discarding the cream after each centrifugation (34). Vortexing the samples might have led to dissolving proteins packed into milk fat globules or cells leading to higher concentrations of ucOCN and cOCN. Additionally, the double centrifugation might have led to smaller interference of fats in the assay and thereby granted higher concentrations of the OCN proteins.

To our knowledge the only previous measurement of OCN in breast milk was done by Pittard et al. (34). Therefore, the following discussion mainly focuses on observed changes in serum OCN. We cannot rule out, that breast tissue actively secretes OCN. To answer this question, it would therefore be useful to conduct follow-up studies comparing OCN concentrations in the blood with those in breast milk of breastfeeding mothers.

Transiently higher ucOCN concentrations in colostrum could have multiple causes: acute stress (35) caused by childbirth, physical activity of active labor (36), and potential mimicry of placental ucOCN secretion (37) might only be a few possible explanations. With regard to the latter point placenta was found to actively secrete ucOCN, which is resorbed by the fetus (37). ucOCN secretion into colostrum might therefore mimic this active secretion to provide the newborn with ucOCN with unknown effects for the child.

Acute stress response was found to be mediated by ucOCN in mice and humans (35). This effect was observed to be facilitated via glutamatergic neurons in bone, inhibiting γ-carboxylase in osteoblasts. Thereby, ucOCN is actively secreted by osteoblasts without changes in osteoclast activity (35). The resulting acute stress response is mediated by ucOCN inhibiting parasympathetic tonus (35). Potentially, higher ucOCN concentration in colostrum might result from the acute stress response during birth.

Interestingly, lower OCN blood concentration was observed in patients 48h after elective abdominal surgery, myocardial infarction or fracture (38). As the birth of a child potentially has a similar stressful effect on the body, the increase in OCN in breast milk is particularly interesting, especially in case of cesarean section. As Dockree et al. did not observe elevated blood lactate after cesarean section, but after vaginal delivery, birth mode potentially might be relevant (39). High intensity interval exercise not only leads to elevation of lactate but also to an elevated ucOCN blood concentration in men and women, while cOCN was unchanged (36). Additionally, in ovariectomized mice, lactate injections as well as high intensity interval training saved bone loss in both groups by stimulating osteoblast activity (40). Like physical activity, vaginal birth also leads to elevated blood lactate concentrations, possibly as a result of active pushing during the second half of active labor (39). Transient elevation of ucOCN might therefore be a result of active labor. Regrettably, mode of birth was not documented; therefore, we cannot exclude a potential effect of cesarean section vs. spontaneous birth on OCN in colostrum. This would also be of interest in consideration of lower OCN blood concentration after abdominal surgery (38). As ucOCN ranges in breast milk were quite large, elevation from active labor and decrease due to cesarean section might both occur, increasing the observed range of OCN in breast milk. Future research into the effects of birth mode on OCN breast milk could be of interest.

As to our knowledge, no OCN expressing cells have been described in human breast tissue, we expect the OCN observed in breast milk to originate from bone. Therefore, varying OCN concentrations could be indicative for differences in bone turnover. Bone turnover was found to be elevated in lactating women and mice, including significantly higher serum levels of OCN in lactating women than in non-lactating women (12, 41, 42). The regulation of bone turnover during lactation is primarily influenced by estradiol suppression due to prolactin increase and gonadotropic-releasing hormone which are both triggered by suckling (43). It would be of great interest to investigate whether the concentration of OCN in breast milk correlates with the extent of bone loss.

We found high fluctuations in OCN between individual mothers, particularly in the colostrum. However, association with different lifestyles factors such as physical activity, habitual diet, and BMI were not detected. Only parity might influence OCN concentration as we found a trend for higher OCN in primiparous mothers.

Previous research found a similar effect of the number of parities on the concentration of immune factors and lactocytes in breast milk (26, 27, 44). Akhter et al. discussed that primiparous women have higher total protein concentrations in serum than multiparous women because primiparous women are, on average, younger than multiparous women (26). However, we were unable to confirm this effect of age when examining the concentration differences in relation to age. Additionally, we adjusted OCN concentration for the total protein concentration in breast milk. Effects of higher total protein concentration in primiparous mothers would have been nullified by this method. We still observed a trend towards higher OCN concentration in breastmilk of primiparous mothers. Tomaszewska et al. discussed anatomical changes in the breast tissue as well as changes in breast milk microbiome of multiparous mothers (44). As we did not take tissue samples or characterize breast milk microbiome, these areas might also influence OCN concentration. Further research into breast tissue changes or influence of microbiome on OCN might identify more unknown sources of this protein.

Another explanation for the reduced OCN concentrations in breast milk of multiparous women could be a lower stress level compared to primiparous women (45, 46). As stress is associated with changes in OCN in healthy adults, patients with diabetes type 2 and depression as well as in mice (19, 35, 47), differences in stress level between primiparous and multiparous women might influence OCN in breast milk. Indeed, Chinese women perceived lower stress levels during their second pregnancy than during their first pregnancy (45), especially when the subjects had positive childbirth experiences (46). The extent to which the mothers felt stressed during pregnancy was not surveyed in our questionnaire. The connection between increased OCN concentrations due to stress requires further studies. Therefore, chronic stress and acute stress both might influence OCN concentration in breast milk.

In comparison to findings from other studies showing that an elevated BMI correlates with ucOCN concentrations (48), we could not find any association with BMI. As pregnancy is associated with physiological weight gain and weight loss was observed between T1 and T3, relevance of BMI on OCN in breastmilk might be debatable. BMI prior to and weight-gain during pregnancy is associated with several health outcomes for mother and child, but measurement of overweight at the end of pregnancy might not be useful as a parameter (49–51). In particular, using a BMI > 25 kg/m2 as threshold for overweight, might not be an appropriate indicator of overweight shortly after giving birth. Longitudinal analysis of women prior to pregnancy could help identifying the influence of weight gain during pregnancy on OCN in mother’s serum as well as breast milk.

The key question is whether OCN in breast milk has any significance for the health and development of the child. ucOCN in particular is thought to have hormonal effects and, as already mentioned, is associated with a lower risk of diabetes or cardiovascular disease (52). However, it is questionable whether the protein is absorbed by the child’s organism. Experimental data suggests that orally ingested OCN survives the gastrointestinal passage and is absorbed in the small intestine of mice (22). Additionally, a recent study described significantly higher median OCN serum concentrations in 4-month-old breastfed children compared to formula-fed children (53). However, whether OCN actually comes from breast milk or stems from an increased endogenous synthesis in breastfed infants still needs to be clarified.

Limitations

The study’s major weakness is that the study population is quite small, especially for subanalyses. Additionally, mass spectrometry potentially would have been the more accurate method to identify OCN, although this method is not established for OCN in breast milk either (54). Only one study previously analyzed OCN in breastmilk. As Pittard et al. used RIA, we chose a similar method even though the manual not explicitly stated breastmilk as a suitable medium (34). Thawing twice, compared to only once in Pittard et al., might additionally have led to smaller concentration of OCN due to breakdown of the protein (34). Keeping this in mind, we still were able to detect higher OCN values than Pittard et al. (34). Further studies on detection of OCN in breastmilk are needed to optimize measurement of OCN in general, and especially in breastmilk.

The main part of the discussion focuses on changes in OCN in serum which might translate into changes in breast milk, since only one previous study analyzed OCN in breast milk (34). Unfortunately, blood was not collected from participating mothers; therefore, we cannot analyze further parameters of maternal bone turnovers. As previously mentioned, birth mode might have influenced ucOCN concentration in colostrum. Including this information could have helped identify causes for the high variance of measured concentrations. It is unclear whether birth duration could also have affected the observed results in colostrum. Further studies should therefore include both characteristics.

As pregnant women are advised to supplement folic acid and iodine, many women tend to consume multivitamins marketed for pregnancy (55, 56). Here vitamin D and vitamin K might have been included. Both of these vitamins could have had an influence on OCN serum concentrations, but the validated questionnaire we used for information on habitual diet did not include questions on supplementation. Finally, self-reported data on habitual diet and physical activity always entail possible bias due to reporting errors, even though habitual diet was comparable to those of female adults in the general population (29).

Conclusion

The results of this study indicate that ucOCN and cOCN are components of breast milk, the concentration of which decrease from colostrum to mature breast milk during the lactation period. Nevertheless, further research is needed to confirm these results and to decipher what function ucOCN and cOCN might have for the newborn.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics committee of the Ruhr University of Bochum, Germany. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

OP: Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Investigation. BH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SN: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. TL: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Resources. KS: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the intramural Research funding from the Faculty of Medicine of the Ruhr University Bochum, FoRUM (F983R-2020).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fendo.2025.1715553/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Wang S, Wei Y, Liu L, and Li Z. Association between breastmilk microbiota and food allergy in infants. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. (2021) 11:770913. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.770913

2. Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJ, França GV, Horton S, Krasevec J, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet (London England). (2016) 387:475–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7

3. Hossain S and Mihrshahi S. Exclusive breastfeeding and childhood morbidity: A narrative review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:14804. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192214804

4. Kramer MS and Kakuma R. The optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding: a systematic review. Adv Exp Med Biol. (2004) 554:63–77. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-4242-8_7

5. Horta BL, Loret de Mola C, and Victora CG. Long-term consequences of breastfeeding on cholesterol, obesity, systolic blood pressure and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr (Oslo Norway 1992). (2015) 104:30–7. doi: 10.1111/APA.13133

6. Ballard O and Morrow AL. Human milk composition: nutrients and bioactive factors. Pediatr Clinics North America. (2013) 60:49–74. doi: 10.1016/J.PCL.2012.10.002

7. Italianer MF, Naninck EF, Roelants JA, van der Horst GT, Reiss IK, van Goudoever JB, et al. Circadian variation in human milk composition, a systematic review. Nutrients. (2020) 12:2328. doi: 10.3390/nu12082328

8. Bravi F, Wiens F, Decarli A, Dal Pont A, Agostoni C, and Ferraroni M. Impact of maternal nutrition on breast-milk composition: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. (2016) 104:646–62. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.120881

9. Ward E, Yang N, Muhlhausler BS, Leghi GE, Netting MJ, Elmes MJ, et al. Acute changes to breast milk composition following consumption of high-fat and high-sugar meals. Maternal Child Nutr. (2021) 17:e13168. doi: 10.1111/mcn.13168

10. Martin CR, Ling P-R, and Blackburn GL. Review of infant feeding: key features of breast milk and infant formula. Nutrients. (2016) 8:279. doi: 10.3390/nu8050279

11. Kovacs CS. Calcium and bone metabolism during pregnancy and lactation. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. (2005) 10:105–18. doi: 10.1007/s10911-005-5394-0

12. Nerius L, Vogel M, Ceglarek U, Kiess W, Biemann R, Stepan H, et al. Bone turnover in lactating and nonlactating women. Arch Gynecol Obstet. (2023) 308:1853–62. doi: 10.1007/S00404-023-07189-0

13. Møller UK, Streym S, Mosekilde L, Heickendorff L, Flyvbjerg A, Frystyk J, et al. Changes in calcitropic hormones, bone markers and insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) during pregnancy and postpartum: a controlled cohort study. Osteoporos Int J Established As Result Cooperation Between Eur Foundation Osteoporos Natl Osteoporos Foundation USA. (2013) 24:1307–20. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-2062-2

14. Hauschka PV, Lian JB, and Gallop PM. Direct identification of the calcium-binding amino acid, gamma-carboxyglutamate, in mineralized tissue. Proc Natl Acad Sci United States America. (1975) 72:3925–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.10.3925

15. Kruse K and Kracht U. Evaluation of serum osteocalcin as an index of altered bone metabolism. Eur J Pediatr. (1986) 145:27–33. doi: 10.1007/BF00441848

16. Hauschka PV and Carr SA. Calcium-dependent alpha-helical structure in osteocalcin. Biochemistry. (1982) 21:2538–47. doi: 10.1021/BI00539A038

17. Kapoor K, Pi M, Nishimoto SK, Quarles LD, Baudry J, and Smith JC. The carboxylation status of osteocalcin has important consequences for its structure and dynamics. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. (2021) 1865:129809. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2020.129809

18. Ferron M, Wei J, Yoshizawa T, Del Fattore A, DePinho RA, Teti A, et al. Insulin signaling in osteoblasts integrates bone remodeling and energy metabolism. Cell. (2010) 142:296–308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.003

19. Oury F, Khrimian L, Denny CA, Gardin A, Chamouni A, Goeden N, et al. Maternal and offspring pools of osteocalcin influence brain development and functions. Cell. (2013) 155:228–41. doi: 10.1016/J.CELL.2013.08.042

20. Lee NK, Sowa H, Hinoi E, Ferron M, Ahn JD, Confavreux C, et al. Endocrine regulation of energy metabolism by the skeleton. Cell. (2007) 130:456–69. doi: 10.1016/J.CELL.2007.05.047

21. Ferron M, Hinoi E, Karsenty G, and Ducy P. Osteocalcin differentially regulates beta cell and adipocyte gene expression and affects the development of metabolic diseases in wild-type mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci United States America. (2008) 105:5266–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711119105

22. Mizokami A, Yasutake Y, Higashi S, Kawakubo-Yasukochi T, Chishaki S, Takahashi I, et al. Oral administration of osteocalcin improves glucose utilization by stimulating glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion. Bone. (2014) 69:68–79. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.09.006

23. Szyller H, Antosz K, Batko J, Mytych A, Dziedziak M, Wrześniewska M, et al. Bioactive components of human milk and their impact on child's health and development, literature review. Nutrients. (2024) 16:1487. doi: 10.3390/nu16101487

24. Bouroutzoglou M, Malamitsi-Puchner A, Boutsikou M, Marmarinos A, Baka S, Boutsikou T, et al. Biochemical markers of bone resorption are present in human milk: implications for maternal and neonatal bone metabolism. Acta Paediatr (Oslo Norway 1992). (2014) 103:1264–9. doi: 10.1111/apa.12771

25. Vidal K, van den Broek P, Lorget F, and Donnet-Hughes A. Osteoprotegerin in human milk: a potential role in the regulation of bone metabolism and immune development. Pediatr Res. (2004) 55:1001–8. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000127014.22068.15

26. Akhter H, Aziz F, Ullah FR, Ahsan M, and Islam SN. Immunoglobulins content in colostrum, transitional and mature milk of Bangladeshi mothers: Influence of parity and sociodemographic characteristics. J Mother Child. (2020) 24:8–15. doi: 10.34763/jmotherandchild.20202403.2032.d-20-00001

27. Hirata N, Kiuchi M, Pak K, Fukuda R, Mochimaru N, Mitsui M, et al. Association between maternal characteristics and immune factors TGF-β1, TGF-β2, and igA in colostrum: an exploratory study in Japan. Nutrients. (2022) 14:3255. doi: 10.3390/NU14163255

28. Gößwald A, Lange M, Kamtsiuris P, and Kurth B-M. DEGS: Studie zur Gesundheit Erwachsener in Deutschland. Bundesweite Quer- und Längsschnittstudie im Rahmen des Gesundheitsmonitorings des Robert Koch-Instituts. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. (2012) 55:775–80. doi: 10.1007/s00103-012-1498-z

29. Kuhn D-A. Entwicklung eines Index zur Bewertung der Ernährungsqualität in der Studie zur Gesundheit Erwachsener in Deutschland (DEGS1). Robert Koch-Institut (2018).

30. Günther J, Hoffmann J, Spies M, Meyer D, Kunath J, Stecher L, et al. Associations between the prenatal diet and neonatal outcomes-A secondary analysis of the cluster-randomised geliS trial. Nutrients. (2019) 11:1889. doi: 10.3390/nu11081889

31. Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, Borodulin K, Buman MP, Cardon G, et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med. (2020) 54:1451–62. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955

32. Weir CB and Jan A. BMI Classification Percentile and Cut Off Points. StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL (2023).

33. Pinheiro RL, Areia AL, Mota Pinto A, and Donato H. Advanced maternal age: adverse outcomes of pregnancy, A meta-analysis. Acta Med Port. (2019) 32:219–26. doi: 10.20344/amp.11057

34. Pittard WB, Geddis KM, and Hollis BW. Osteocalcin and human milk. Biol Neonate. (1993) 63:61–3. doi: 10.1159/000243909

35. Berger JM, Singh P, Khrimian L, Morgan DA, Chowdhury S, Arteaga-Solis E, et al. Mediation of the acute stress response by the skeleton. Cell Metab. (2019) 30:890–902.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.08.012

36. Hiam D, Landen S, Jacques M, Voisin S, Alvarez-Romero J, Byrnes E, et al. Osteocalcin and its forms respond similarly to exercise in males and females. Bone. (2021) 144:115818. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2020.115818

37. Song L, Huang Y, Long J, Li Y, Pan Z, Fang F, et al. The role of osteocalcin in placental function in gestational diabetes mellitus. Reprod Biol. (2021) 21:100566. doi: 10.1016/j.repbio.2021.100566

38. Napal J, Amado JA, Riancho JA, Olmos JM, and González-Macías J. Stress decreases the serum level of osteocalcin. Bone Miner. (1993) 21:113–8. doi: 10.1016/s0169-6009(08)80013-x

39. Dockree S, O'Sullivan J, Shine B, James T, and Vatish M. How should we interpret lactate in labour? A reference study. BJOG an Int J Obstet Gynaecol. (2022) 129:2150–6. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.17264

40. Zhu Z, Chen Y, Zou J, Gao S, Wu D, Li X, et al. Lactate mediates the bone anabolic effect of high-intensity interval training by inducing osteoblast differentiation. J Bone Joint Surg Am Volume. (2023) 105:369–79. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.22.01028

41. Bornstein S, Brown SA, Le PT, Wang X, DeMambro V, Horowitz MC, et al. FGF-21 and skeletal remodeling during and after lactation in C57BL/6J mice. Endocrinology. (2014) 155:3516–26. doi: 10.1210/EN.2014-1083

42. Sowers M, Eyre D, Hollis BW, Randolph JF, Shapiro B, Jannausch ML, et al. Biochemical markers of bone turnover in lactating and nonlactating postpartum women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (1995) 80:2210–6. doi: 10.1210/JCEM.80.7.7608281

43. Athonvarangkul D and Wysolmerski JJ. Crosstalk within a brain-breast-bone axis regulates mineral and skeletal metabolism during lactation. Front Physiol. (2023) 14:1121579. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2023.1121579

44. Tomaszewska A, Porębska K, Jeleniewska A, Królikowska K, Lipińska-Opałka A, Rustecka A, et al. Parity influences the immune profile of human milk via increased T lymphocyte content. Acta Paediatr (Oslo Norway 1992). (2025) 114:3298–3308. doi: 10.1111/apa.70259

45. Cai Y, Shen Z, Zhou B, Zheng X, Li Y, Liu Y, et al. Psychological status during the second pregnancy and its influencing factors. Patient Prefer Adherence. (2022) 16:2355–63. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S374628

46. McKelvin G, Thomson G, and Downe S. The childbirth experience: A systematic review of predictors and outcomes. Women Birth J Aust Coll Midwives. (2021) 34:407–16. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2020.09.021

47. Nguyen MM, Anita NZ, Darwish L, Major-Orfao C, Colby-Milley J, Wong SK, et al. Serum osteocalcin is associated with subjective stress in people with depression and type 2 diabetes. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2020) 122:104878. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2020.104878

48. Kord-Varkaneh H, Djafarian K, Khorshidi M, and Shab-Bidar S. Association between serum osteocalcin and body mass index: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocrine. (2017) 58:24–32. doi: 10.1007/s12020-017-1384-4

49. Kries Rv, Ensenauer R, Beyerlein A, Amann-Gassner U, Hauner H, and Rosario AS. Gestational weight gain and overweight in children: Results from the cross-sectional German KiGGS study. Int J Pediatr Obes IJPO. (2011) 6:45–52. doi: 10.3109/17477161003792564

50. Kries Rv, Chmitorz A, KM R, Bayer O, and Ensenauer R. Late pregnancy reversal from excessive gestational weight gain lowers risk of childhood overweight–a cohort study. Obes (Silver Spring Md.). (2013) 21:1232–7. doi: 10.1002/oby.20197

51. Philippe K, Douglass AP, McAuliffe FM, and Phillips CM. Associations between lifestyle and well-being in early and late pregnancy in women with overweight or obesity: Secondary analyses of the PEARS RCT. Br J Health Psychol. (2025) 30:e12776. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12776

52. Riquelme-Gallego B, García-Molina L, Cano-Ibáñez N, Sánchez-Delgado G, Andújar-Vera F, García-Fontana C, et al. Circulating undercarboxylated osteocalcin as estimator of cardiovascular and type 2 diabetes risk in metabolic syndrome patients. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:1840. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-58760-7

53. Berggren SS, Dahlgren J, Andersson O, Bergman S, and Roswall J. Reference limits for osteocalcin in infancy and early childhood: A longitudinal birth cohort study. Clin Endocrinol. (2024) 100:399–407. doi: 10.1111/CEN.15036

54. Determe W, Hauge SC, Demeuse J, Massonnet P, Grifnée E, Huyghebaert L, et al. Osteocalcin: A bone protein with multiple endocrine functions. Clin Chim Acta Int J Clin Chem. (2025) 567:120067. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2024.120067

55. Koletzko B, Cremer M, Flothkötter M, Graf C, Hauner H, Hellmers C, et al. Diet and lifestyle before and during pregnancy - practical recommendations of the Germany-wide healthy start - young family network. Geburtshilfe Und Frauenheilkunde. (2018) 78:1262–82. doi: 10.1055/a-0713-1058

Keywords: lactation, human milk, osteocalcin, breastfeeding, bone

Citation: Prosperi O, Hanusch B, Naber S, Lücke T and Sinningen K (2025) Osteocalcin in human breast milk over the course of lactation. Front. Endocrinol. 16:1715553. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2025.1715553

Received: 29 September 2025; Accepted: 12 November 2025; Revised: 05 November 2025;

Published: 26 November 2025.

Edited by:

Yong-Can Huang, Peking University, ChinaCopyright © 2025 Prosperi, Hanusch, Naber, Lücke and Sinningen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kathrin Sinningen, a2F0aHJpbi5zaW5uaW5nZW5AcnViLmRl

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Olivier Prosperi1,2†

Olivier Prosperi1,2† Beatrice Hanusch

Beatrice Hanusch Kathrin Sinningen

Kathrin Sinningen