- 1State Key Laboratory of Experimental Hematology, National Clinical Research Center for Blood Diseases, Institute of Hematology & Blood Diseases Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, Tianjin, China

- 2Department of Hematology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University, Hematology Research Center of Yunnan Province, Kunming, China

- 3Central Laboratory, Fujian Medical University Union Hospital, Fuzhou, China

Alveolar macrophages (AMs) are pivotal for maintaining lung immune homeostasis. We demonstrated that deletion of liver kinase b1 (Lkb1) in CD11c+ cells led to greatly reduced AM abundance in the lung due to the impaired self-renewal of AMs but not the impeded pre-AM differentiation. Mice with Lkb1-deficient AMs exhibited deteriorated diseases during airway Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) infection and allergic inflammation, with excessive accumulation of neutrophils and more severe lung pathology. Drug-mediated AM depletion experiments in wild type mice indicated a cause for AM reduction in aggravated diseases in Lkb1 conditional knockout mice. Transcriptomic sequencing also revealed that Lkb1 inhibited proinflammatory pathways, including IL-17 signaling and neutrophil migration, which might also contribute to the protective function of Lkb1 in AMs. We thus identified Lkb1 as a pivotal regulator that maintains the self-renewal and immune function of AMs.

Introduction

Alveolar macrophages (AMs) act as the first sentinels of the pulmonary innate immune system (1), whose niche in the alveolar space is important for monitoring pulmonary homeostasis. Under steady conditions, AMs are primarily derived from fetal monocytes and maintain their niche by proliferative self-renewal (1, 2). Studies have shown that AM development is highly dependent on granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) receptor signaling, as both Csf2ra- and Csf2rb-deficient mice are devoid of AMs (3). GM-CSF has a lung-specific role in the perinatal development of AMs via induction of PPAR-γ in fetal monocytes, which may promote the differentiation of pre-AMs into mature AMs (4). In addition, reports have identified that another cytokine, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), is critical for the development and maturation of AMs (2, 5). Although these studies have examined the development of AMs, the potential molecular mechanisms underlying the self-renewal of terminally differentiated AMs are not well understood.

The number of AMs is maintained at constant levels to sustain pulmonary homeostasis and respiratory function and to initiate the response to inhaled pathogens in the lung (1). AMs have a role in regulating response to infections and epithelial injury. AMs can interact with alveolar epithelial cells, dendritic cells (DCs) and T cells through cell surface receptors and chemokine/cytokine networks to finely regulate the immune response to environmental pathogens and lung particles (6, 7). Anti-inflammatory molecules are highly expressed in AMs, in which the CD200 receptor can bind its ligand on alveolar epithelial cells to inhibit the inflammatory response induced by the Toll-like receptor (8). In addition, signal-regulatory protein-α, which is expressed on AMs, inhibits macrophage activation and phagocytosis by binding surfactant proteins A and D (6, 9). AMs also release TGF-β, which prevents DC-mediated activation of effector T cells to inhibit immune responses (1). AMs recognize opsonized microorganisms and facilitate pathogen clearance using different receptors, such as immunoglobulin receptors and complement receptors (10, 11). How AMs recognize the presence of pathogens or products of injury and respond directly to provide optimal host protection and the potential molecules that regulate these responses remain to be discovered.

Liver kinase b1 (Lkb1), a serine–threonine kinase and tumor suppressor, was first identified in Peutz–Jeghers syndrome (12, 13). Lkb1 participates in multiple processes, including cell polarity, cell cycle arrest, embryonic development, hematopoietic stem cell maintenance, apoptosis and metabolism (14). In various tissues, Lkb1 plays an important role in regulating glucose homeostasis and energy metabolism. In addition, there is also evidence that has highlighted a prominent role for Lkb1 in the function of macrophages (15). Lkb1 inhibits the activation and inflammatory function of innate macrophages (16, 17). However, the roles of Lkb1 in regulating the homeostasis of AMs and specific airway inflammation need to be investigated.

Here, we investigated the role of Lkb1 in the maintenance of AM self-renewal and immune homeostasis. We found that disruption of Lkb1 impaired the self-renewal of AMs, contributing to the reduction of AMs, which led to aggravated symptoms and excessive accumulation of neutrophils in Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) pneumonia and asthma. In addition, we found that many critical immune genes of AMs are regulated by Lkb1. Transcriptomic sequencing also revealed that Lkb1 inhibits proinflammatory pathways, including IL-17 signaling and neutrophil migration pathways. Therefore, we identified Lkb1 as a crucial maintainer of AM self-renewal and immune homeostasis.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Mice were housed in specific pathogen-free barrier facilities. Mice were used in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Institute of Hematology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. C57BL/6 mice, Lkb1f/f mice, AMPKα1f/f mice and Cd11cCre mice were all purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). The mice were backcrossed with C57BL/six mice for at least seven generations. Lkb1f/f mice and AMPKα1f/f mice were crossed with Cd11cCre mice to generate Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice and Cd11cCreAMPKα1f/f mice, respectively. Mice were used at 6–8 weeks old, unless otherwise indicated.

Cell Isolation and Preparation

For analysis of cell surface markers, single cell suspensions were prepared from BAL fluid, lung, medLN, kidney, liver and thymus. To obtain BAL fluid cells, mice were sacrificed and pinned upright to a dissection board. The tracheas were exposed, and a small opening was cut with surgical scissors. A 1 ml syringe with a needle was inserted into the tracheal opening, and the alveolar cavity was washed with 500 µl PBS at least six times. BAL fluid was obtained and transferred to a 10 ml tube. The lung, medLN, kidney, liver and thymus single-cell suspensions were prepared using the same procedure as follows. The target tissues were finely ground with a filter, and the red blood cells were lysed with 200 µl erythrocyte lysate (Solarbio) for 10 min at 4°C. Leukocytes were washed with PBS to obtain single cell suspensions.

Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometry antibodies and their clone numbers are listed in Table S2. Cell surface staining was performed at 4°C for 30–40 min in the dark. The cells were stimulated with phorbol myristate acetate (50 ng/ml) and ionomycin (500 ng/ml) for 4–5 h for intracellular cytokine staining. Intracellular staining with Ki67 was performed using Foxp3 staining kits (eBioscience). The antibodies we used were purchased from Biolegend, BD Bioscience, eBioscience, and Invitrogen. The indicated AM populations were sorted by FACSAria III (BD Biosciences) from BAL fluid or lung. The purity of sorted populations was >99%, unless otherwise indicated. Data were obtained on a FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software (FlowJo LLC, Ashland, Oregon).

Bone Marrow Chimera Model

Recipient CD45.1+CD45.2+ mice (8–10 weeks old) were lethally irradiated twice with 400 cGy. Irradiated recipient mice were then intravenously injected with 1 × 107 BM cells, which were from Lkb1f/f (CD45.1+) mice and Cd11cCreLkb1f/f (CD45.2+) mice at a ratio of 3:1. Chimeric mice were housed in sterile caging for 8 weeks to allow for reconstitution.

Apoptosis Detection

According to the instructions of the manufacturers, Annexin V and PI staining were performed with an apoptosis detection kit (Biolegend) to test the apoptosis of AMs from Lkb1f/f mice and Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice by flow cytometry (Canto II, BD Biosciences).

S. aureus Pneumonia Model

Lkb1f/f and Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice were intranasally challenged with 5 × 104 colony-forming units (CFU) per animal of S. aureus in 50 μl PBS. The mouse body weight was monitored until the mouse died or up to 6 days. The secretion of inflammatory cytokines by T cells in the lung and medLN and the percentage of neutrophils and eosinophils in the lung and BAL fluid were analyzed by flow cytometry 3 days after challenge. BAL fluid was obtained for culture on day 3 after challenge to calculate CFU.

Encapsome and Clodrosome

Encapsome and Clodrosome are the products of Encapsula NanoSciences (SKU# CLD-8901). The clodronate was encapsulated with liposomes to form a multilamellar liposome suspension, which is called Clodrosome. Encapsome is the control liposome of Clodrosome, in which clodronate was not added to the liposomes. The larger particles were removed from the liposomes, and all the preparation processes were performed under sterile conditions. When treated with Clodrosome, the phagocytic cells in animals recognize liposomes as invasive foreign particles and remove liposomes by phagocytosis. Then, the liposomes released the clodronate into the cytosol, leading to cell death. The recognition and phagocytosis mechanism of Encapsome was the same as that of Clodrosome. Since the Encapsome did not contain clodronate, the phagocytic cells were not killed.

AMs Depletion

Lkb1f/f mice were intranasally challenged with 100 μl (500 μg) Encapsome or Clodrosome (5 mg/ml, from Encapsula NanoSciences, SKU# CLD-8901) per mouse once a day, one to two times a week.

HDM Asthma Model

Lkb1f/f and Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice were intraperitoneally anesthetized with chloral hydrate (Solarbio) and then intranasally challenged with 25 μg HDM (Greer Laboratories Inc., Lenoir, NC, USA) per animal in 50 μl PBS on days 0, 2, 4, 7, 9, 11, 14, 15, and 16 (12). On day 17, the mice were sacrificed, and the secretion of inflammatory cytokines by T cells in the lung and medLNs and the percentage of neutrophils and eosinophils in the lung and BAL fluid were analyzed by flow cytometry.

RNA-Seq

CD45+ CD11c+ SiglecF+ AMs in the lungs of Lkb1f/f and Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice were sorted for RNA sequencing. The purity of sorted populations was more than 99%. RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) for RNA sequencing analysis on the BGISEQ500 platform (BGI-Shenzhen, China). DESeq2 (v1.4.5) was used for the differential expression analysis (18) with a Q value ≤0.05. RNA transcriptome sequencing datasets were analyzed and edited using GlueGO in Cytoscape software (19). We have submitted the RNA-Seq datasets to the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), and the accession number is GSE167349.

Histological Analyses

Samples were harvested from the lungs on day 3 after S. aureus infection and fixed with 10% formalin immediately. Samples were washed using 70% ethanol and embedded in paraffin. Then, they were cut into 6-μm thick slices and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The presented data are from individual lung. All slices used for analysis were encoded and read blindly. Photomicrographs were taken at a 10 × and 40 × magnification.

Lung Injury Score

Two investigators quantified the lung injury score blindly according to published criteria of American Thoracic Society Documents (20). Each sample was analyzed for at least five fields. Five independent parameters of lung injury scoring system were as follows: A. neutrophils in the alveolar space; B. neutrophils in the interstitial space; C. hyaline membranes; D. proteinaceous debris filling the airspaces; E. alveolar septal thickening. The calculation was: scores = [(20 × A) + (14 × B) + (7 × C) + (7 × D) + (2 × E)]/(number of fields × 100). The resulting score is a continuous value between zero and one (inclusive).

Statistics

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Software (Prism 5.00, San Diego, CA, USA). The statistical significance of the difference between the two groups was calculated, and the P-value was determined. According to the number of comparison groups, Student’s t-test or two-way ANOVA was performed. P <0.05 was considered statistically significant. *P <0.05; **P <0.01; ***P <0.001.

Results

Loss of Lkb1 Leads to a Marked Reduction of AMs

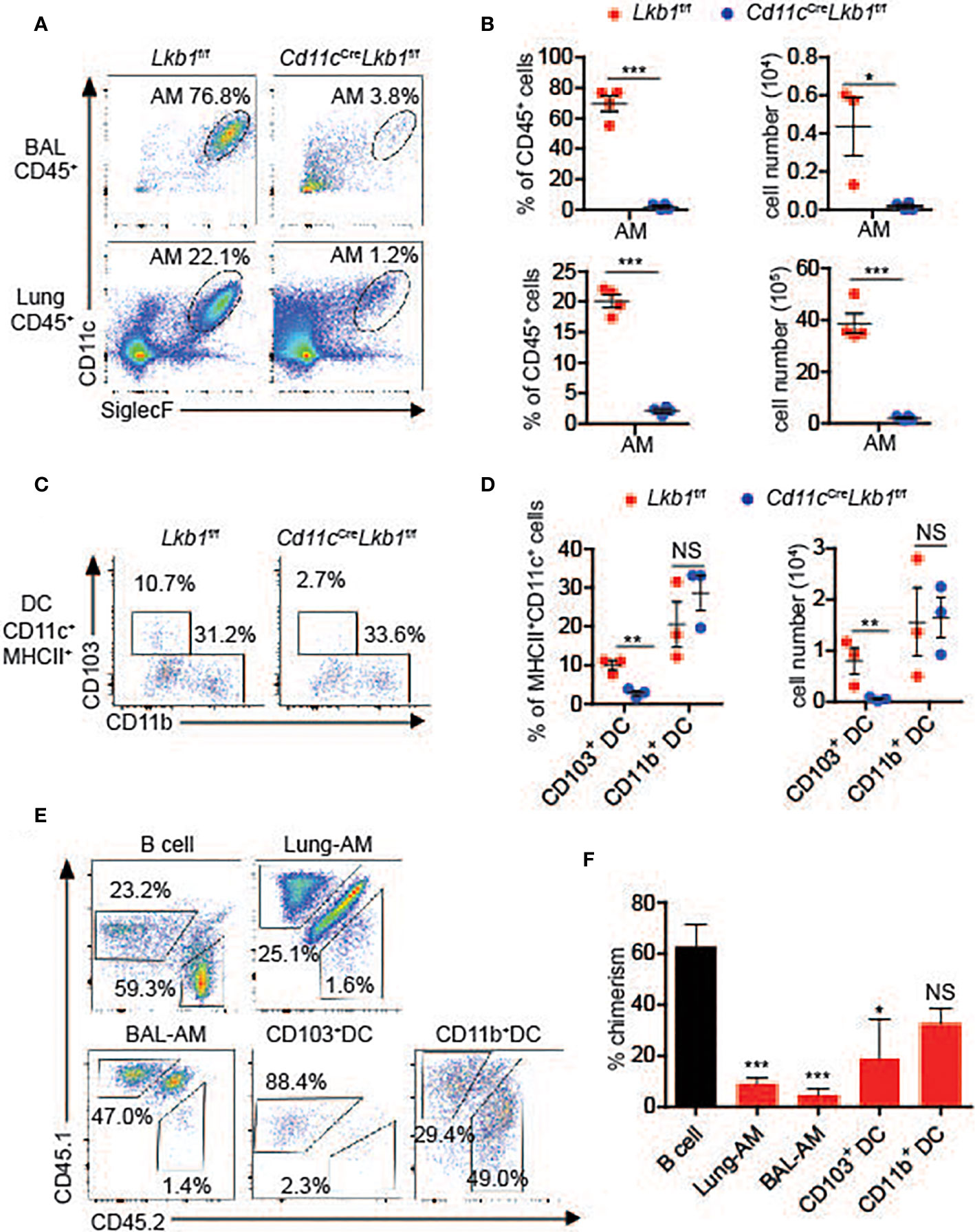

CD11c is highly expressed on AMs, and studies have shown that LysmCre-mediated recombination results in inefficient gene deletion in AMs (1, 4, 21). Therefore, we used Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice, in which Lkb1 was deleted in CD11c+ cells, including DCs and macrophages, to explore the function of Lkb1 in AMs. Interestingly, we found that the numbers of AMs and CD103+ DCs were prominently decreased in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid and/or lungs from Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice (Figures 1A–D). Conversely, lung interstitial macrophages (IMs), lung CD11b+ DCs and DCs in other tissues, including the kidney, liver and thymus, were unaffected (Figures 1C, D and Figures S1A–C). We then investigated whether cell-intrinsic or cell-extrinsic factors contributed to AM reduction using a mixed bone marrow chimera model in which Lkb1-deficient (CD45.2+) bone marrow (BM) cells and wild type (CD45.1+) BM cells were mixed at a ratio of 3:1 and then transferred into CD45.1+ CD45.2+ host mice. We observed significant impairment only in AM and CD103+ DC accumulation (Figures 1E, F), indicating that the homeostatic defects of AMs and CD103+ DCs were cell intrinsic.

Figure 1 Loss of Lkb1 leads to a marked reduction in AMs in Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice. (A) The AM frequency among CD45+ leucocytes in BAL fluid and lungs from Lkb1f/f mice and Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice was analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) The percentages and absolute numbers of AMs in BAL fluid and lungs from Lkb1f/f mice and Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice (n = 4). (C) Flow cytometry analysis of CD103+ and CD11b+ DC frequencies among CD11c+ MHCII+ DCs in the lungs of Lkb1f/f mice and Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice. (D) The percentages and absolute numbers of CD103+ and CD11b+ DCs in the lungs of Lkb1f/f mice and Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice (n = 4). (E) Mixed bone marrow chimeras were established by mixing Lkb1-deficient (CD45.2) BM cells and wild type (CD45.1) BM cells (3:1) and transferring them to CD45.1+ CD45.2+ host mice. Chimeras were analyzed by flow cytometry. (F) The bar chart shows the frequency of chimerism contributed by Lkb1-deficient cells to the indicated control B cells (n = 3–5). Each symbol (B, D) represents a mouse, and the results are presented as the mean ± S.D., NS (not significant), P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, (by Student’s t-test) (B, D, F). All data represent at least three independent experiments.

Impaired Self-Renewal Contributes to the Reduction of Lkb1-Deficient AMs

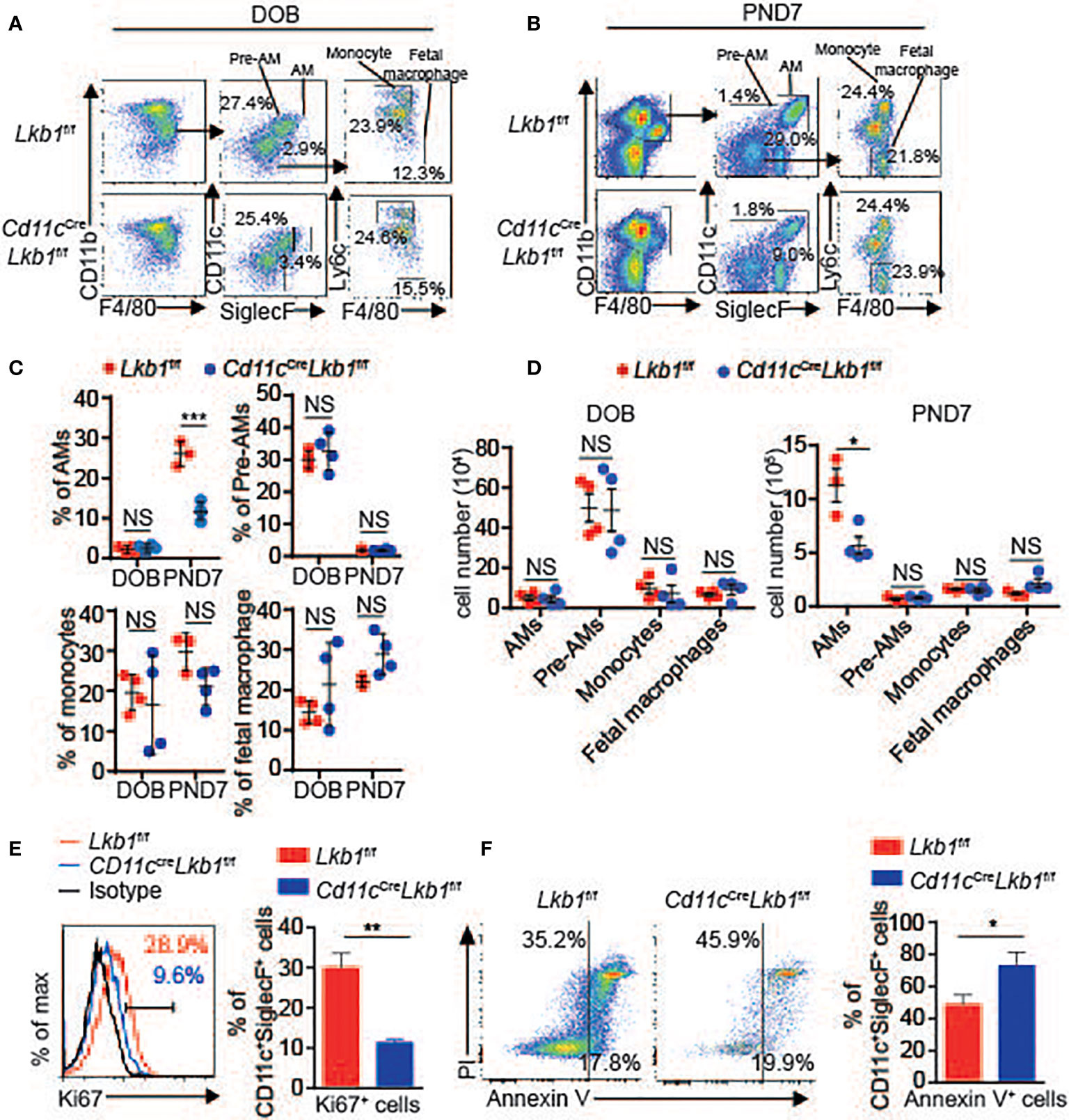

The development of AMs, including the stepwise process from monocytes, prealveolar macrophages (pre-AMs) and mature AMs in neonatal mice, is essential for maintaining the AM population (1). To determine whether the development of AMs was retarded and participated in their absence, we analyzed the numbers of monocytes, pre-AMs and mature AMs in the lungs of Cd11cCreLkb1f/f and Lkb1f/f mice on DOB (day of birth) and PND7 (postnatal day 7). The mature AM population was comparable between Lkb1f/f and Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice on DOB. Although the percentage and absolute number of mature AMs in Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice were significantly reduced, we observed that the percentages and absolute numbers of monocytes, fetal macrophages and pre-AMs were comparable in Lkb1f/f and Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice at PND7 (Figures 2A–D). These results indicated that the reduction in the AM pool occurred postnatally but not prenatally. Since the AM population is autonomously maintained by proliferative self-renewal throughout life (1), we thus examined whether self-renewal was impaired and contributed to AM reduction in Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice. Results showed that Lkb1-deficient AMs exhibited increased apoptosis and reduced proliferation compared to wild type AMs (Figures 2E, F). These results suggest that impaired self-renewal rather than AM development contribute to AM reduction in Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice.

Figure 2 Lkb1 deletion leads to increased apoptosis and impaired proliferation. (A, B) Representative flow chart showing the gating scheme to identify mature AMs (gated as CD11c+ SiglecF+ F4/80+ CD11bint), pre-AMs (gated as CD11c+ SiglecF− F4/80+ CD11bint), monocytes (gated as CD11bhigh Ly6c+ CD11c- SiglecF− F4/80low) and fetal macrophages (gated as CD11b+ F4/80+ Ly6c− CD11c− SiglecF-) in the lungs of Lkb1f/f and Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice on DOB (A) and PND7 (B). (C, D) The percentages (C) and absolute numbers (D) of mature AMs, pre-AMs, monocytes and fetal macrophages in the lungs of Lkb1f/f and Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice on DOB and PND7 (n = 3–4). (E) Expression of Ki67 in AMs from Lkb1f/f and Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice (n = 3). (F) Annexin V and PI staining of AMs and quantification of apoptotic AMs (assessed as Annexin V-positive cells) from Lkb1f/f and Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice (n = 3). Each symbol (C, D) represents a mouse, and the results are presented as the mean ± S.D., NS (not significant) P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, (by Student’s t-test) (C, D, E, F). All data represent at least three independent experiments.

Cd11cCreLkb1f/f Mice are More Susceptible to S. aureus Infection

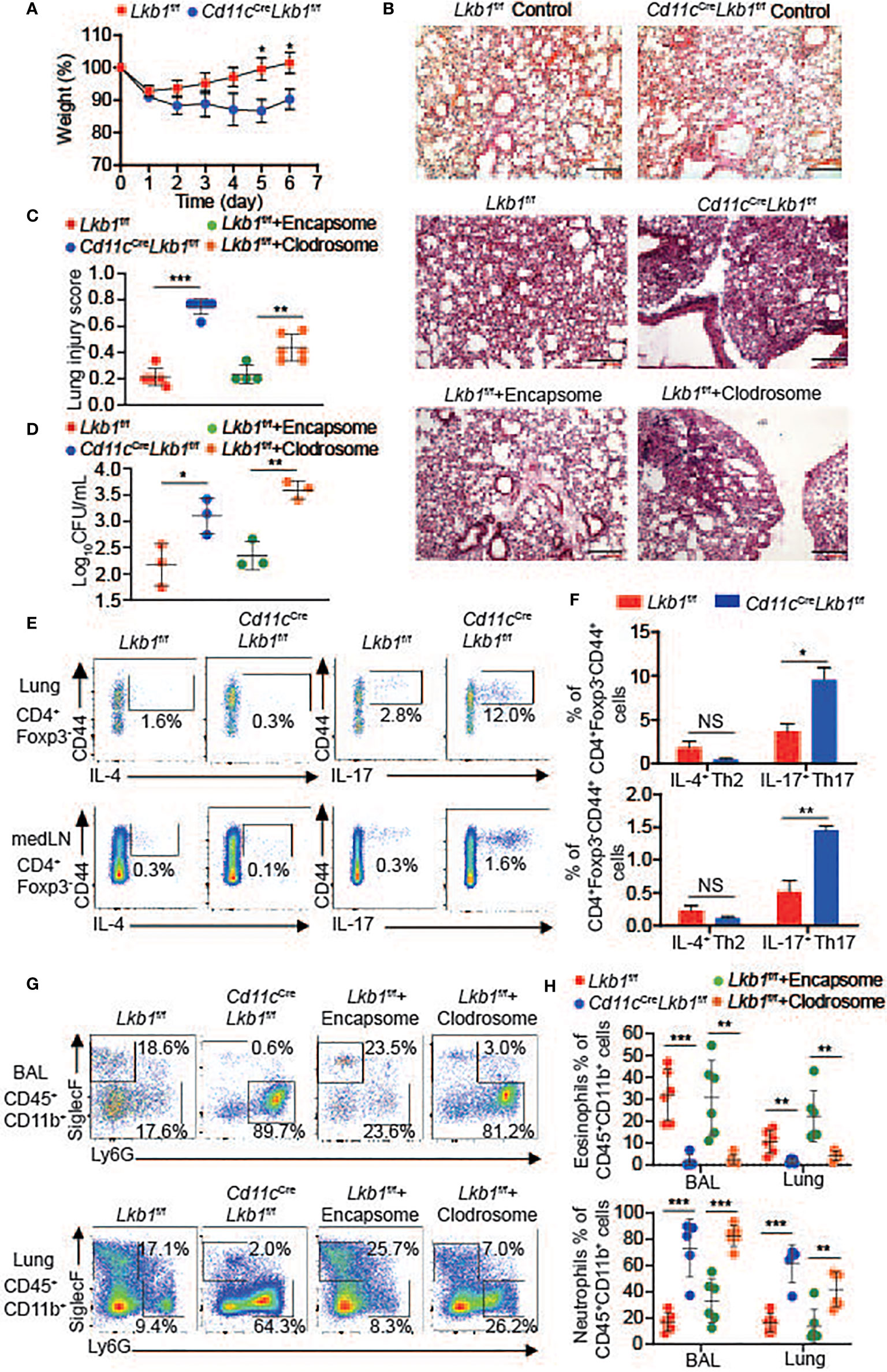

The AM pool is maintained at constant levels to ensure lung homeostasis, respiratory function and the pulmonary response of scavenging inhaled pathogens (22). Therefore, we detected the impact of decreased AM number on the pulmonary response using an S. aureus pneumonia model. Compared to Lkb1f/f mice, Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice presented much more body weight loss and severe inflammation by pathologic analysis (Figures 3A–C and Figure S2A). Moreover, we evaluated the bacterial scavenging capacity of AMs by culturing BAL fluid from Lkb1f/f and Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice challenged with S. aureus pneumonia. BAL fluid from Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice produced more colonies than that from Lkb1f/f mice, indicating that Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice had defects in bacterial scavenging capacity (Figure 3D). In addition, we observed an increased percentage of T helper 17 (Th17) cells in the lung and mediastinal lymph node (medLN) in Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice (Figures 3E, F). There is evidence that IL-17 enhances neutrophil accumulation under inflammatory conditions (23, 24). Indeed, an increased frequency of neutrophils and a significant reduction in eosinophils were observed in the lungs and BAL in Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice (Figures 3G, H). These results indicate that Th17/neutrophilic inflammation was driven by Lkb1 ablation in AMs. We next determined whether loss of AMs also contributes to neutrophilic lung inflammation during S. aureus pneumonia. Lkb1f/f mice intranasally administered Clodrosome but not control liposomes-Encapsome exhibited approximately 70% depletion of AMs with no change in DCs, including CD11b+ DCs or CD103+ DCs (Figures S3A–D). Consistent with the phenotype in Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice, Lkb1f/f mice without AMs also exhibited more severe pathology, impaired bacteria-scavenging capacity and an imbalance between eosinophils and neutrophils in the lung during S. aureus pneumonia (Figures 3B–D, G, H and Figure S2A). Although the potential role of CD103+ DCs may not be completely excluded, AM deletion in Lkb1f/f mice caused almost the same degree of changes in lung pathology and neutrophil and eosinophil variation as observed in Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice; thus, we concluded that AMs exerted a dominant role in S. aureus infection and might be involved in maintaining the balance between eosinophils and neutrophils in the lung during S. aureus pneumonia.

Figure 3 Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice are more susceptible to S. aureus infection. (A) The relative weights of Lkb1f/f and Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice challenged with S. aureus intranasally (n = 9–11). (B) Images show histopathological sections of lungs from naive Lkb1f/f mice, Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice, and Lkb1f/f, Cd11cCreLkb1f/f and Lkb1f/f mice intranasally administered Encapsome or Clodrosome, intranasally challenged with S. aureus, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (scale bar, 100 μm). (C) The lung injury score was evaluated blindly by two independent investigators (n = 6). (D) Quantification of BAL fluid CFUs cultured for 48 h from Lkb1f/f, Cd11cCreLkb1f/f and Lkb1f/f mice intranasally administered Clodrosome or Encapsome and intranasally challenged with S. aureus. (E, F) Flow cytometry analysis (E) and the frequencies (F) of CD4+ Foxp3− CD44+ IL-4+ Th2 cells or CD4+ Foxp3− CD44+ IL-17+ Th17 cells in the lung and medLNs from Lkb1f/f and Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice challenged with S. aureus intranasally (n = 3). (G, H) Flow cytometry analysis (G) and quantification of the percentages (H) of eosinophils (CD45+ CD11b+ Siglec-F+) and neutrophils (CD45+ CD11b+ Ly6G+) in BAL fluid and lungs from Lkb1f/f, Cd11cCreLkb1f/f and Lkb1f/f mice intranasally administered Encapsome or Clodrosome and challenged with S. aureus intranasally (n = 3). Each symbol (C, D, H) represents a mouse, and the results are presented as the mean ± S.D., NS (not significant) P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (by Student’s t-test) (C, D, F, H), two-way ANOVA (A). All data represent at least two to three independent experiments.

Cd11cCreLkb1f/f Mice Develop More Severe Pathology in Asthma

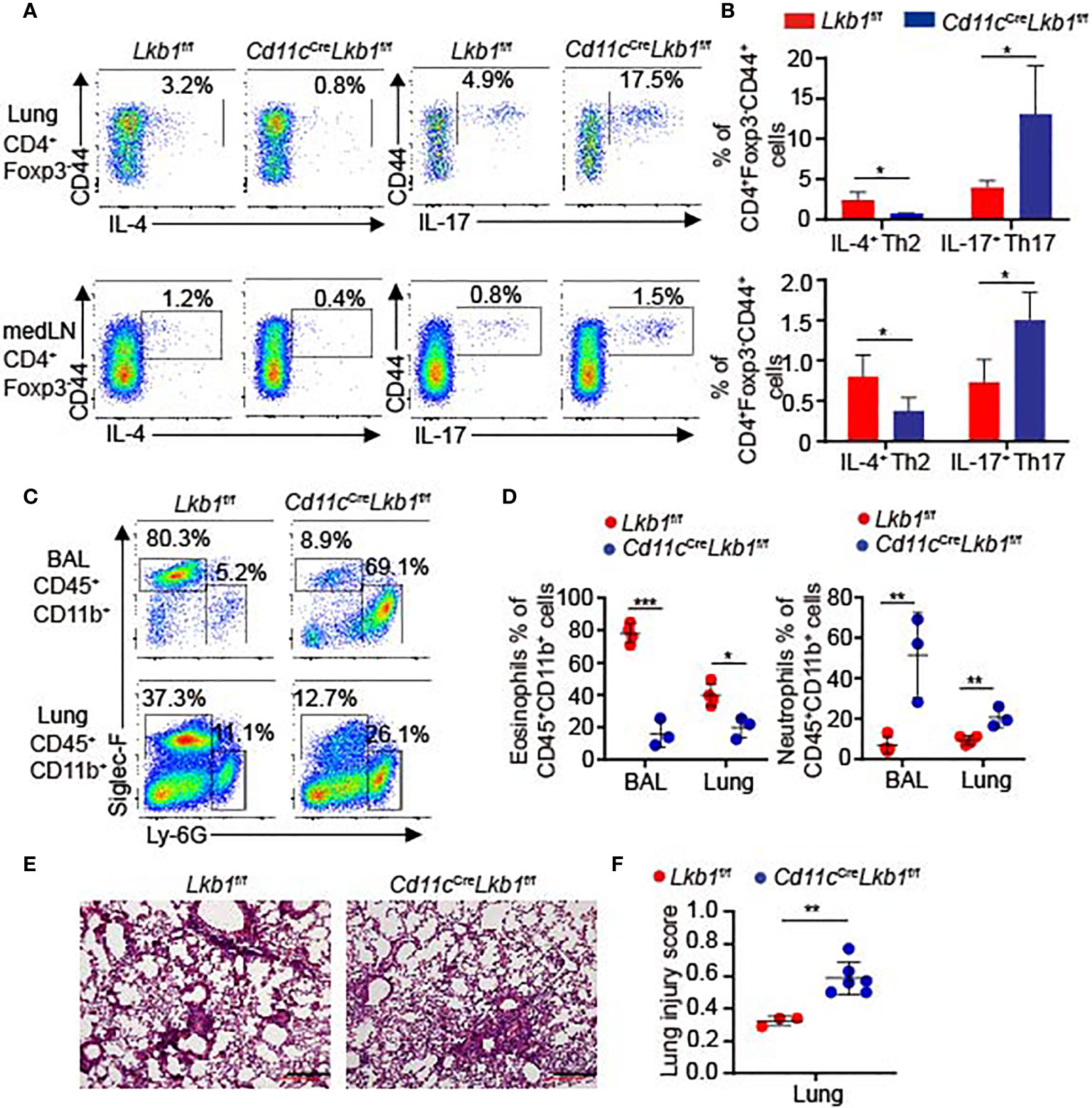

We also utilized an asthma model to investigate whether the lung inflammatory response was functionally affected in Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice. Lkb1f/f and Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice were challenged with house dust mite (HDM) allergen intranasally. We observed a significant reduction in IL-4-producing T helper 2 (Th2) cells and an increased frequency of IL-17-producing Th17 cells in the lungs and medLNs of Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice (Figures 4A, B). The typical feature of Th2-polarized allergies is the robust recruitment of eosinophils, whereas IL-17 increases neutrophil recruitment (25). Remarkably, we observed that eosinophil accumulation was decreased, while the percentages of neutrophils were significantly increased in BAL fluid and lungs from Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice (Figures 4C, D). Moreover, Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice manifested more severe pathology in the lung than Lkb1f/f mice (Figures 4E, F). These results indicate that the immunoprotective function is impaired in Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice during allergic inflammation. AMs were directly deleted by intranasal administration of Clodrosome in Lkb1f/f mice to verify the crucial role of AMs in asthma. Although Lkb1f/f mice with AM depletion developed more severe pathology and displayed defects in recruiting eosinophils in the lung (Figures S4A–D), no significant increase in neutrophils was observed in the lungs of Lkb1f/f mice in the absence of AMs. These results suggest that AMs exert a dominant role in protecting the host from allergic inflammation and participate in regulating the balance of neutrophils and eosinophils during lung inflammation.

Figure 4 Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice developed more severe pathology in asthma. (A, B) Flow cytometry analysis (A) and the frequency (B) of CD4+ Foxp3- CD44+ IL-4+ Th2 cells or CD4+ Foxp3- CD44+ IL-17+ Th17 cells in the lung and medLNs from Lkb1f/f and Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice intranasally challenged with HDM allergens (n = 3–4). (C) Flow cytometry analysis of eosinophils (CD45+ CD11b+ Siglec-F+) and neutrophils (CD45+ CD11b+ Ly6G+) in BAL fluid and lungs from Lkb1f/f and Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice intranasally challenged with HDM allergen. (D) Quantification of the percentages of eosinophils and neutrophils in BAL fluid and lungs from Lkb1f/f and Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice intranasally challenged with HDM allergen (n = 3–4). (E) Images show histopathological sections of lungs from Lkb1f/f and Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice intranasally challenged with HDM allergen and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (scale bar, 100 μm). (F) The lung injury score was evaluated blindly by two independent investigators (n = 3–6). Each symbol (D, F) represents a mouse, and results are presented as the mean ± S.D., *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, (by Student’s t-test) (B, D, F). All data represent at least three independent experiments.

Lkb1 Regulates Critical Immune and Metabolic Gene Expression in AMs

Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is an important downstream target of Lkb1 for regulating metabolism (14). To investigate whether AMPK was involved in AM reduction caused by Lkb1 deletion, we generated Cd11cCreAMPKα1f/f mice in which AMPK was specifically deleted in CD11c+ cells. However, we found that the numbers of AMs or DCs were not significantly different between AMPKα1f/f and Cd11cCreAMPKα1f/f mice (Figures S5A–D). These results indicate that the function of Lkb1 in maintaining AM abundance is independent of AMPK.

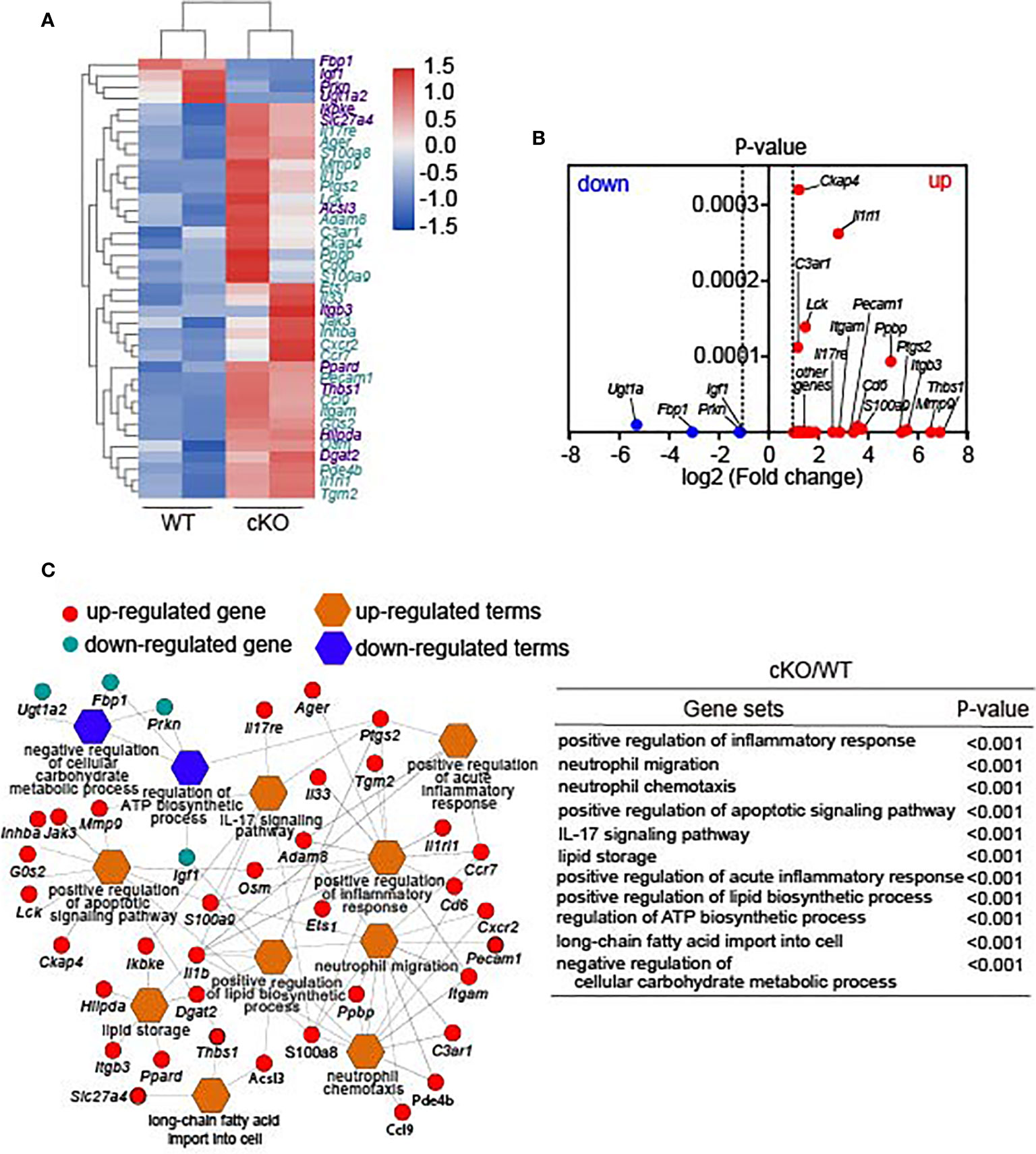

To explore the potential molecular mechanisms of Lkb1 in regulating the homeostasis and functions of AMs, we further analyzed the transcriptome sequencing of AMs sorted from Cd11cCreLkb1f/f and Lkb1f/f mice. Remarkably, there were 508 transcripts with a ≥2- or ≤-2-fold change in Lkb1-deficient AMs. Expression of a wide variety of genes critically involved in immune function was increased in Lkb1-deficient AMs, including those encoding secreted cytokines and chemokines (Il1b, Il33, Cc19), their related receptors (Il1rl1, Il17re, C3ar1) associated with immune activation, factors in the acute inflammatory response (Ptgs2) (26), and molecular and chemokine receptors in neutrophil migration and chemotaxis (Itgb3, Itgam, Pecam1, Ccxr2, Ccr7) (27). The increased expression of inflammatory mediators in Lkb1-deficient AMs might contribute to the more severe pathology in Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice during S. aureus infection and allergic inflammation. Four genes were observed to have significantly reduced expression in Lkb1-deficient AMs, including Igf-1, Fbp1, Prkn and Ugtla2. Igf-1 enhances phagocytosis and bacterial killing in AMs (28, 29), which could explain the impaired bacterial scavenging capacity in AMs from Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice during S. aureus infection. The Ugtla2 gene regulates glycogen/glucose level and promotes the storage of glycogen (30), and the Fbp1 gene encodes fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase 1, which inhibits glycolysis and tumor growth (31). Pathogenic variants in Prkn led to mitochondrial autophagy (32). In addition, some genes critically participating in lipid metabolism exhibited increased expression, such as fatty acid synthesis (Dgat2) (33) and transport (Slc27a4) and lipid synthesis, storage and β-oxidation (Acsl3, Dgat2, Hilpda) (34). Inhba and Osm genes, which inhibit cell proliferation, and the G0s2 gene, whose function is promoting apoptosis, were increased in Lkb1-deficient AMs (Figures 5A, B) (35). Furthermore, GO (Gene Ontology) enrichment and pathway analysis revealed that positive regulation of the apoptotic signaling pathway was upregulated (Figure 5C, Table S1), which could explain the higher apoptosis proportion in Lkb1-deficient AMs. In addition, some pathways related to immune responses and metabolism were also enriched in Lkb1-deficient AMs (Figure 5C). Immune response-related pathways, including positive regulation of the (acute) inflammatory response and the IL-17 signaling pathway, were upregulated in Lkb1-deficient AMs, confirming the crucial function of Lkb1 in the suppression of the inflammatory response. Metabolism-related pathways, including positive regulation of the lipid biosynthetic process pathway, long-chain fatty acid import into cells and lipid storage, were upregulated in Lkb1-deficient AMs. The pathway for regulating the ATP biosynthetic process was downregulated in Lkb1-deficient AMs, which could be the potential mechanism through AM reduction occurs. These results suggest that Lkb1 operates as a pivotal mediator of AM immune protective function and metabolic homeostasis in the lung.

Figure 5 Lkb1 regulates critical immune and metabolic gene expression in AMs. (A) Heat map showing differentially expressed genes between AMs from Lkb1f/f and Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice; genes labeled purple are related to metabolism, and genes labeled blue are related to immune function. (B) Volcano plot showing differentially expressed genes in Lkb1-deficient AMs compared to AMs from Lkb1f/f mice. (C) Network displaying the related genes involved in the pathways enriched in Lkb1-deficient AMs. The list (right) of gene sets and corresponding P-values are shown. CD45+ CD11c+ SiglecF+ AMs were sorted from the lungs of at least five to 10 mice in each sample with a FACSAria III (BD Biosciences). A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Discussion

In our study, we demonstrated that mice with CD11c+ cell-specific deletion of Lkb1 exhibited a dramatically decreased number and percentage of AMs. However, the CD11c+ cell-specific deletion of AMPKα1 did not cause any reduction in AMs, indicating that the function of Lkb1 in maintaining the homeostasis of AMs was independent of the classical AMPK signaling pathway. Previous studies have shown that proliferative self-renewal is essential to maintain the AM population (36). However, the molecular mechanisms underlying the self-renewal of terminally differentiated AMs are not well understood. In our study, we found that loss of Lkb1 impaired AM self-renewal, reflected by increased apoptosis and reduced proliferation. Therefore, Lkb1 acts as a key regulator of AM self-renewal and homeostasis.

AMs play a crucial role in the maintenance of lung homeostasis and innate immune responses to pathogens (37). AMs certainly contribute to the development of severe inflammation (38–40), but they also play an important role in limiting excessive inflammation caused by infection. In the absence of AMs, influenza virus infection led to reduced viral clearance and increased inflammation and pathology (41–43). Here, we found that Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice exhibited defects in bacterial scavenging capacity and aggravated infection in response to S. aureus pneumonia. It is well known that DCs are an essential bridge between innate and adaptive immunity that induce a T cell-specific immune response. AMs can suppress the induction of an adaptive immune response via their effects on alveolar and interstitial DCs and T cells. Similarly, increasing evidence suggests that AMs also have an important role in regulating T cell differentiation and the immune response in the lung. Previous studies have demonstrated that AMs suppress immune responses by inhibiting DC-mediated T cell activation and TGF-β production (44–46). A recent study revealed that CARD9S12N could turn AMs into IL-5-producing cells, facilitating the pathologic responses mediated by Th2 cells (47). However, the mechanisms that underlie AMs regulating the immune response remain incompletely understood.

Interestingly, Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice manifested excessive accumulation of neutrophils and a significant reduction in eosinophils in response to S. aureus pneumonia and asthma, indicating that Lkb1 plays a dominant role in maintaining the balance between eosinophilic and neutrophilic mediators of lung inflammation. Additionally, as shown in transcriptome analysis, the IL-17 signaling pathway was significantly enhanced in Lkb1-deficient AMs, which might lead to neutrophil accumulation and more severe pathology in S. aureus infection in Cd11cCreLkb1f/f mice. Recent study also demonstrated that LysmCreLkb1f/f mice manifested more severe lung inflammation during Klebsiella pneumonia. These result indicated that Lkb1 is essential for local host defense during S. aureus and Klebsiella pneumonia by maintaining adequate AM numbers in the lung (48). In our study, we found that in addition to preserving AM abundance, Lkb1 may also protect the host from immune pathology and tissue damage by inhibiting expression of genes involved in immune activation and inflammation. Compared to other tissue macrophages, the different signatures involved in lipid metabolism of AMs highlighted their important role in the maintenance of airway homeostasis (49). Lkb1-deficient AMs might experience metabolic stress due to the lack of expression of cellular metabolic program-related genes, such as Ugtla2, Fbp1 and Prkn. Although Lkb1-AMPK signaling could be activated under cellular stress conditions, increasing evidence has demonstrated that Lkb1 regulates lipid oxidation and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production independent of AMPK (50, 51). Therefore, it is unclear whether the cellular stress of Lkb1-deficient AMs is dependent or independent of AMPK signaling. AMPK conditional knockout mice had no effect on the AM pool, indicating that Lkb1 maintains the abundance of AMs independent of its classic downstream AMPK.

In conclusion, our results revealed an important role for Lkb1 in the maintenance of self-renewal and immune homeostasis in AMs. Lkb1 has crucial roles in suppressing signaling pathways related to the inflammatory response, including the IL-17 signaling pathway and neutrophil migration and chemotaxis signaling pathways. Our findings extend the understanding of AM homeostasis and function and the lung immune regulatory mechanism, indicating that the Lkb1 pathway may represent a potential therapeutic target to intervene in pulmonary inflammatory diseases.

Data Availability Statement

We have submitted the RNA-Seq datasets to Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and the accession number is GSE167349.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Institute of Hematology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Author Contributions

QW, CS, and XF designed the study. QW, SC, and TL performed the experiments and analyzed the data. QY, JL, YT, YM, and JC helped with some experiments. QW and CS wrote the paper. XF edited the paper. EJ and XF helped to obtain funding for the research. ZH, HH, MS, MH, EJ, and XF oversaw the project. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81670171 to EJ, 81870090 to XF), the Nonprofit Central Research Institute Fund of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (2018PT32034 to HL, 2019-RC-HL-013 to XF), the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS, 2016-12M-1-003), the Tianjin Science Funds for Distinguished Young Scholars (17JCJQJC45800 to XF), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (3332019095 to CS).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

S. aureus was provided by Prof. Yuanfu Xu in our laboratory.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2021.629281/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Kopf M, Schneider C, Nobs SP. The Development and Function of Lung-Resident Macrophages and Dendritic Cells. Nat Immunol (2015) 16:36–44. doi: 10.1038/ni.3052

2. Yu X, Buttgereit A, Lelios I, Utz SG, Cansever D, Becher B, et al. The Cytokine Tgf-β Promotes the Development and Homeostasis of Alveolar Macrophages. Immunity (2017) 47:903–12. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.10.007

3. Schneider C, Nobs SP, Heer AK, Kurrer M, Klinke G, van Rooijen N, et al. Alveolar Macrophages are Essential for Protection From Respiratory Failure and Associated Morbidity Following Influenza Virus Infection. PloS Pathog (2014) 10:e1004053. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004053

4. Schneider C, Nobs SP, Kurrer M, Rehrauer H, Thiele C, Kopf M. Induction of the Nuclear Receptor PPAR-γ by the Cytokine GM-CSF is Critical for the Differentiation of Fetal Monocytes Into Alveolar Macrophages. Nat Immunol (2014) 15:1026–37. doi: 10.1038/ni.3005

5. Lambrecht BN. Tgf-β Gives an Air of Exclusivity to Alveolar Macrophages. Immunity (2017) 47:807–9. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.11.005

6. Hussell T, Bell TJ. Alveolar Macrophages: Plasticity in a Tissue-Specific Context. Nat Rev Immunol (2014) 14:81–93. doi: 10.1038/nri3600

7. Westphalen K, Gusarova GA, Islam MN, Subramanian M, Cohen TS, Prince AS, et al. Sessile Alveolar Macrophages Communicate With Alveolar Epithelium to Modulate Immunity. Nature (2014) 506:503–6. doi: 10.1038/nature12902

8. Snelgrove RJ, Goulding J, Didierlaurent AM, Lyonga D, Vekaria S, Edwards L, et al. A Critical Function for CD200 in Lung Immune Homeostasis and the Severity of Influenza Infection. Nat Immunol (2008) 9:1074–83. doi: 10.1038/ni.1637

9. Janssen WJ, McPhillips KA, Dickinson MG, Linderman DJ, Morimoto K, Xiao YQ, et al. Surfactant Proteins a and D Suppress Alveolar Macrophage Phagocytosis Via Interaction With Sirpα. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2008) 178:158–67. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200711-1661OC

10. Schneberger D, Aharonson-Raz K, Singh B. Monocyte and Macrophage Heterogeneity and Toll-Like Receptors in the Lung. Cell Tissue Res (2011) 343:97–106. doi: 10.1007/s00441-010-1032-2

11. Gordon SB, Read RC. Macrophage Defences Against Respiratory Tract Infections: The Immunology of Childhood Respiratory Infections. Br Med Bull (2002) 61:45–61. doi: 10.1093/bmb/61.1.45

12. Hemminki A, Avizienyte E, Roth S, Loukola A, Aaltonen LA, Järvinen H, et al. A Serine/Threonine Kinase Gene Defective in Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome. Nature (1998) 391:184–7. doi: 10.1038/34432

13. Jenne DE, Reimann H, Nezu J, Friedel W, Loff S, Jeschke R, et al. Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome is Caused by Mutations in a Novel Serine Threonine Kinase. Nat Genet (1998) 18:38–43. doi: 10.1038/ng0198-38

14. Shackelford DB, Shaw RJ. The LKB1-AMPK Pathway: Metabolism and Growth Control in Tumour Suppression. Nat Rev Cancer (2009) 9:563–75. doi: 10.1038/nrc2676

15. Liu Z, Zhu H, Dai X, Wang C, Ding Y, Song P, et al. Macrophage Liver Kinase B1 Inhibits Foam Cell Formation and Atherosclerosis. Circ Res (2017) 121:1047–57. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311546

16. Liu Z, Zhang W, Zhang M, Zhu H, Moriasi C, Zou MH. Liver Kinase B1 Suppresses Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Nuclear Factor κb (Nf-κb) Activation in Macrophages [Published Correction Appears in J Biol Chem. 2019 Jul 5;294(27):10737]. J Biol Chem (2015) 290:2312–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.616441

17. Liu Z, Dai X, Zhu H, Zhang M, Zou MH. Lipopolysaccharides Promote s-Nitrosylation and Proteasomal Degradation of Liver Kinase B1 (LKB1) in Macrophages In Vivo. J Biol Chem (2015) 290:19011–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.649210

18. Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNA-Seq Data With Deseq2. Genome Biol (2014) 15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8

19. Bindea G, Galon J, Mlecnik B. Cluepedia Cytoscape Plugin: Pathway Insights Using Integrated Experimental and in Silico Data. Bioinformatics (2013) 29:661–3. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt019

20. Matute-Bello G, Downey G, Moore BB, Groshong SD, Matthay MA, Slutsky AS, et al. Acute Lung Injury in Animals Study Group. An Official American Thoracic Society Workshop Report: Features and Measurements of Experimental Acute Lung Injury in Animals. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol (2011) 44:725–38. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0210ST

21. Chen S, Yang Q, Liu J, Huang H, Shi M, Feng X. Tsc1 Controls the Development and Function of Alveolar Macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2018) 498:592–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.03.027

22. Gibbings SL, Goyal R, Desch AN, Leach SM, Prabagar M, Atif SM, et al. Transcriptome Analysis Highlights the Conserved Difference Between Embryonic and Postnatal-Derived Alveolar Macrophages. Blood (2015) 126:1357–66. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-01-624809

23. Allen JE, Sutherland TE, Rückerl D. IL-17 and Neutrophils: Unexpected Players in the Type 2 Immune Response. Curr Opin Immunol (2015) 34:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2015.03.001

24. Chesné J, Braza F, Mahay G, Brouard S, Aronica M, Magnan A. IL-17 in Severe Asthma. Where do We Stand? Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2014) 190:1094–101. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201405-0859PP

25. Alcorn JF, Crowe CR, Kolls JK. TH17 Cells in Asthma and COPD. Annu Rev Physiol (2010) 72:495–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135926

26. Hellmann J, Tang Y, Zhang MJ, Hai T, Bhatnagar A, Srivastava S, et al. Atf3 Negatively Regulates Ptgs2/Cox2 Expression During Acute Inflammation. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat (2015) 116–117:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2015.01.001

27. Wu Y, Stabach P, Michaud M, Madri JA. Neutrophils Lacking Platelet-Endothelial Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 Exhibit Loss of Directionality and Motility in CXCR2-Mediated Chemotaxis. J Immunol (2005) 175:3484–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3484

28. Geertz R, Kiess W, Kessler U, Hoeflich A, Tarnok A, Gercken G. Expression of IGF Receptors on Alveolar Macrophages: IGF-Induced Changes in Inspi Formation, [Ca2+]I, and Phi. Mol Cell Biochem (1997) 177:33–45. doi: 10.1023/A:1006836631673

29. Bessich JL, Nymon AB, Moulton LA, Dorman D, Ashare A. Low Levels of Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 Contribute to Alveolar Macrophage Dysfunction in Cystic Fibrosis. J Immunol (2013) 191:378–85. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300221

30. He J, Gao Y, Wu G, Lei X, Zhang Y, Pan W, et al. Molecular Mechanism of Estrogen-Mediated Neuroprotection in the Relief of Brain Ischemic Injury. BMC Genet (2018) 19:46. doi: 10.1186/s12863-018-0630-y

31. Grasmann G, Smolle E, Olschewski H, Leithner K. Gluconeogenesis in Cancer Cells - Repurposing of a Starvation-Induced Metabolic Pathway? Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer (2019) 1872:24–36. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2019.05.006

32. El-Hattab AW, Suleiman J, Almannai M, Scaglia F. Mitochondrial Dynamics: Biological Roles, Molecular Machinery, and Related Diseases. Mol Genet Metab (2018) 125:315–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2018.10.003

33. Zammit VA. Hepatic Triacylglycerol Synthesis and Secretion: DGAT2 as the Link Between Glycaemia and Triglyceridaemia. Biochem J (2013) 451:1–12. doi: 10.1042/BJ20121689

34. Padanad MS, Konstantinidou G, Venkateswaran N, Melegari M, Rindhe S, Mitsche M, et al. Fatty Acid Oxidation Mediated by Acyl-Coa Synthetase Long Chain 3 is Required for Mutant KRAS Lung Tumorigenesis. Cell Rep (2016) 16:1614–28. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.07.009

35. Zagani R, El-Assaad W, Gamache I, Teodoro JG. Inhibition of Adipose Triglyceride Lipase (ATGL) by the Putative Tumor Suppressor G0S2 or a Small Molecule Inhibitor Attenuates the Growth of Cancer Cells. Oncotarget (2015) 6:28282–95. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5061

36. Deng W, Yang J, Lin X, Shin J, Gao J, Zhong XP. Essential Role of Mtorc1 in Self-Renewal of Murine Alveolar Macrophages. J Immunol (2017) 198:492–504. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501845

37. Kawasaki T, Ito K, Miyata H, Akira S, Kawai T. Deletion of Pikfyve Alters Alveolar Macrophage Populations and Exacerbates Allergic Inflammation in Mice. EMBO J (2017) 36:1707–18. doi: 10.15252/embj.201695528

38. Högner K, Wolff T, Pleschka S, Plog S, Gruber AD, Kalinke U, et al. Macrophage-Expressed IFN-β Contributes to Apoptotic Alveolar Epithelial Cell Injury in Severe Influenza Virus Pneumonia [Published Correction Appears in Plos Pathog. 2016 Jun;12(6):E1005716]. PloS Pathog (2013) 9:e1003188. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003188

39. Herold S, Steinmueller M, von Wulffen W, Cakarova L, Pinto R, Pleschka S, et al. Lung Epithelial Apoptosis in Influenza Virus Pneumonia: The Role of Macrophage-Expressed TNF-Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand. J Exp Med (2008) 205:3065–77. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080201

40. Bem RA, Bos AP, Wösten-van Asperen RM, Bruijn M, Lutter R, Sprick MR, et al. Potential Role of Soluble TRAIL in Epithelial Injury in Children With Severe RSV Infection. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol (2010) 42:697–705. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0100OC

41. Kim HM, Lee YW, Lee KJ, Kim HS, Cho SW, van Rooijen N, et al. Alveolar Macrophages are Indispensable for Controlling Influenza Viruses in Lungs of Pigs. J Virol (2008) 82:4265–74. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02602-07

42. Tate MD, Pickett DL, van Rooijen N, Brooks AG, Reading PC. Critical Role of Airway Macrophages in Modulating Disease Severity During Influenza Virus Infection of Mice. J Virol (2010) 84:7569–80. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00291-10

43. Tumpey TM, García-Sastre A, Taubenberger JK, Palese P, Swayne DE, Pantin-Jackwood MJ, et al. Pathogenicity of Influenza Viruses With Genes From the 1918 Pandemic Virus: Functional Roles of Alveolar Macrophages and Neutrophils in Limiting Virus Replication and Mortality in Mice. J Virol (2005) 79:14933–44. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.23.14933-14944.2005

44. Strickland D, Kees UR, Holt PG. Regulation of T-Cell Activation in the Lung: Isolated Lung T Cells Exhibit Surface Phenotypic Characteristics of Recent Activation Including Down-Modulated T-Cell Receptors, But are Locked Into the G0/G1 Phase of the Cell Cycle. Immunology (1996) 87:242–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.460541.x

45. Holt PG, Oliver J, Bilyk N, McMenamin C, McMenamin PG, Kraal G, et al. Downregulation of the Antigen Presenting Cell Function(s) of Pulmonary Dendritic Cells In Vivo by Resident Alveolar Macrophages. J Exp Med (1993) 177:397–407. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.2.397

46. Thepen T, Van Rooijen N, Kraal G. Alveolar Macrophage Elimination In Vivo is Associated With an Increase in Pulmonary Immune Response in Mice. J Exp Med (1989) 170:499–509. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.2.499

47. Xu X, Xu JF, Zheng G, Lu HW, Duan JL, Rui W, et al. CARD9S12N Facilitates the Production of IL-5 by Alveolar Macrophages for the Induction of Type 2 Immune Responses. Nat Immunol (2018) 19:547–60. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0112-4

48. Otto NA, de Vos AF, van Heijst JWJ, Roelofs JJTH, van der Poll T. Myeloid Liver Kinase B1 Depletion is Associated With a Reduction in Alveolar Macrophage Numbers and an Impaired Host Defense During Gram-Negative Pneumonia. J Infect Dis (2020) 10:jiaa416. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa416

49. Gautier EL, Shay T, Miller J, Greter M, Jakubzick C, Ivanov S, et al. Gene-Expression Profiles and Transcriptional Regulatory Pathways That Underlie the Identity and Diversity of Mouse Tissue Macrophages. Nat Immunol (2012) 13:1118–28. doi: 10.1038/ni.2419

50. Jeppesen J, Maarbjerg SJ, Jordy AB, Fritzen AM, Pehmøller C, Sylow L, et al. LKB1 Regulates Lipid Oxidation During Exercise Independently of AMPK. Diabetes (2013) 62:1490–9. doi: 10.2337/db12-1160

Keywords: alveolar macrophages, Lkb1, self-renewal, immune function, immune homeostasis

Citation: Wang Q, Chen S, Li T, Yang Q, Liu J, Tao Y, Meng Y, Chen J, Feng X, Han Z, Shi M, Huang H, Han M and Jiang E (2021) Critical Role of Lkb1 in the Maintenance of Alveolar Macrophage Self-Renewal and Immune Homeostasis. Front. Immunol. 12:629281. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.629281

Received: 14 November 2020; Accepted: 01 April 2021;

Published: 22 April 2021.

Edited by:

Hideki Nakano, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), United StatesReviewed by:

Sanja Arandjelovic, University of Virginia, United StatesTaku Kuwabara, Toho University, Japan

Copyright © 2021 Wang, Chen, Li, Yang, Liu, Tao, Meng, Chen, Feng, Han, Shi, Huang, Han and Jiang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Erlie Jiang, amlhbmdlcmxpZUAxNjMuY29t; Mingzhe Han, bXpoYW5AaWhjYW1zLmFjLmNu; Huifang Huang, aHVhbmdodWlmQDEyNi5jb20=; Mingxia Shi, c2hteGlhMjAwMkBzaW5hLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Qianqian Wang

Qianqian Wang Song Chen1†

Song Chen1† Tengda Li

Tengda Li Yuan Meng

Yuan Meng Xiaoming Feng

Xiaoming Feng Mingzhe Han

Mingzhe Han