- 1Division of Biochemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy and Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Science, Keio University, Tokyo, Japan

- 2International Research and Developmental Center for Mucosal Vaccines, The Institute of Medical Science, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan

The intestinal surface is constitutively exposed to diverse antigens, such as food antigens, food-borne pathogens, and commensal microbes. Intestinal epithelial cells have developed unique barrier functions that prevent the translocation of potentially hostile antigens into the body. Disruption of the epithelial barrier increases intestinal permeability, resulting in leaky gut syndrome (LGS). Clinical reports have suggested that LGS contributes to autoimmune diseases such as type 1 diabetes, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and celiac disease. Furthermore, the gut commensal microbiota plays a critical role in regulating host immunity; abnormalities of the microbial community, known as dysbiosis, are observed in patients with autoimmune diseases. However, the pathological links among intestinal dysbiosis, LGS, and autoimmune diseases have not been fully elucidated. This review discusses the current understanding of how commensal microbiota contributes to the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases by modifying the epithelial barrier.

Introduction

The intestinal mucosa is exposed to a myriad of external antigens such as food antigens, food-borne pathogens, and commensal microbes that reside in the intestinal lumen. Therefore, the intestine serves as a barrier tissue whereby a monolayer of intestinal epithelial cells establishes a multilayered physicochemical barrier (1). The intestinal epithelial barrier contributes to the maintenance of biological homeostasis by segregating the internal and external milieus by restricting the infiltration of external antigens and the leakage of endogenous substances. To this end, intestinal epithelial cells form tight junctions (TJs) (2). TJ protein complexes tightly connect epithelial cells to reduce paracellular permeability. The main integral proteins of the TJs include occludin and claudins (3, 4). Their intracellular domains are associated with zonula occludens (ZO) proteins that connect the junctional complexes with myosin 1C, an important component of the actin cytoskeleton (5, 6). Furthermore, myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) acts with peri-junctional actomyosin rings to regulate the contractility of actin fibers, thereby influencing TJ structure and permeability (7, 8).

The mucosal barrier also includes mucin, antimicrobial peptides, and dimeric (or more polymeric) IgA secreted by goblet cells, Paneth cells, and plasma cells, respectively (9–11). These effector molecules constitute a barrier between luminal microbes and intestinal epithelium to prevent microbial adherence to the epithelium. However, mucosal barrier dysfunction (especially the disruption of TJs) often leads to enhanced intestinal permeability (12), a pathological status termed “leaky gut syndrome” (LGS). LGS initiates inflammatory responses in the intestine and in extraintestinal tissue (13, 14). Thus, the translocation of commensal microbes into the body disturbs immune homeostasis by inducing systemic inflammation; however, the commensal microbiota is important for shaping the gut immune system while they remain confined in the intestinal lumen (15). Such beneficial effects are ascribed to certain microbial products that promote the proliferation and differentiation of intestinal epithelial cells and multiple immune cell subsets including regulatory T cells and T helper type 17 (Th17) cells (16). Indeed, germ-free mice exhibit defects in the maturation of gut-associated lymphoid tissues and mesenteric lymph nodes, leading to attenuated production of secretory IgA (S-IgA) (17).

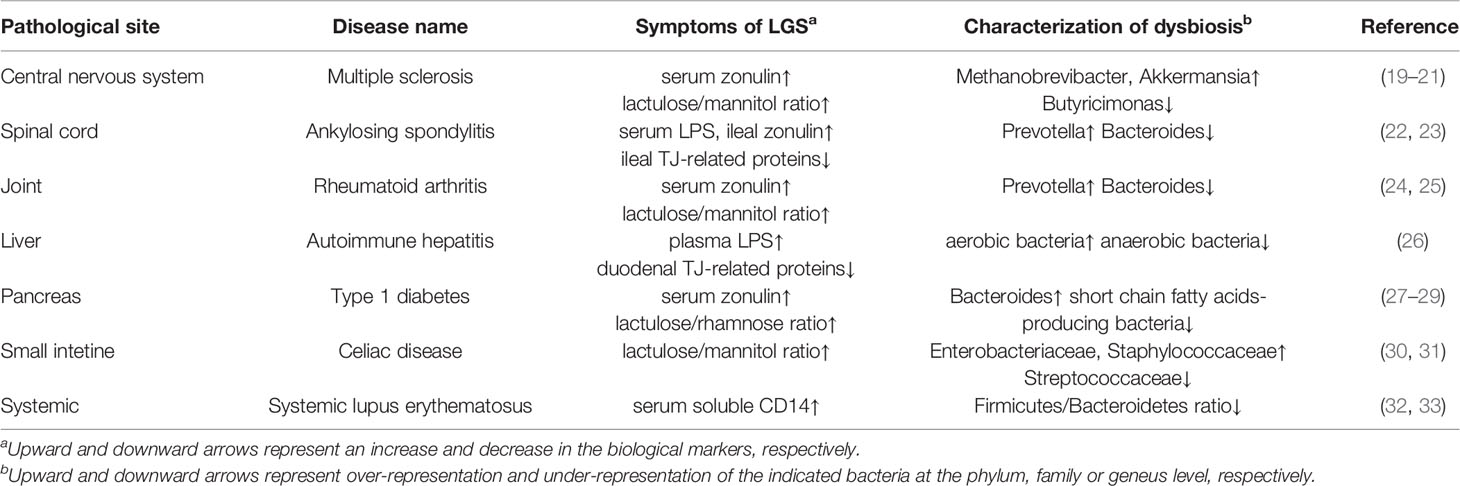

Altered microbial composition, termed dysbiosis, has been implicated in mucosal barrier dysfunction and inflammatory responses, which predispose the host animals to systemic diseases (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, food allergy, obesity, and autoimmune diseases) (18). Accumulating reports have revealed that both LGS and dysbiosis are evident in some patients with autoimmune diseases (Table 1). In humans, lactulose/mannitol or lactulose/rhamnose tests have been used to assess intestinal permeability by measuring the urinary excretion of unabsorbed lactulose and absorbed mannitol or rhamnose. The lactulose/mannitol or lactulose/rhamnose ratio increases in patients with multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 diabetes, or celiac disease (19, 24, 27, 30). Moreover, serum concentrations of lipopolysaccharide and soluble CD14 are indicators of intestinal permeability. Elevated serum lipopolysaccharide concentration and reduced TJ-related protein concentrations are observed in patients with ankylosing spondylitis or autoimmune hepatitis (22, 26). Likewise, serum soluble CD14 concentrations are elevated in those with systemic lupus erythematosus (32). These patients with autoimmune disease exhibit altered microbial compositions, compared with healthy volunteers (20, 23, 25, 26, 28, 31, 33). Thus far, it remains uncertain whether LGS and dysbiosis are causes or consequences of autoimmune diseases.

Early research has shown that proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., tumor necrosis factor-α [TNF-α] and interferon-γ) impair TJ integrity (34–36), whereas immunosuppressive cytokines (e.g., interleukin [IL]-10 and transforming growth factor-β) reinforce the TJs (37, 38). IL-22 secreted by intestinal immune cells is also vital for epithelial homeostasis (i.e., epithelial repair and intestinal stemness) as well as epithelial barrier functions (39). In support of this view, IL-22 induces claudin-2 to facilitate the clearance of enteric pathogens under physiological conditions (40). However, under inflammatory conditions such as Crohn’s disease, constitutive expression of claudin-2 by IL-22 eventually leads to an increment of intestinal permeability (41, 42). Thus, the cytokine milieu is a critical factor that influences epithelial barrier function. Given that the gut commensal microbiota plays an essential role in regulating gut immunity, the microbiota should affect the epithelial barrier by regulating cytokine-induced barrier changes. In this review, we discuss the link between the commensal microbiota and epithelial barrier function, as well as the potential contribution of dysbiosis-associated LGS to the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases.

Regulatory Mechanisms of the TJ Barrier

The innate immune system can sense pathogen-associated molecular patterns via pattern recognition receptors, including Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing proteins (i.e., NOD1 and NOD2) (43). Intestinal epithelial cells also express most TLRs and both NODs, among which TLR2 and TLR4 signaling may influence the integrity of TJ complexes. TLR2 recognizes lipopeptides, which are major cell wall components of bacteria. TLR2 signaling activates protein kinase C (PKC) and consolidates junctional complexes by recruiting ZO-1 in vitro (44). In contrast, TLR4 signaling (mediated by myeloid differentiation primary response 88 [MyD88]) enhances intestinal permeability, both in vitro and in vivo (45). TLR4 signaling activates MLCK by initiating the canonical nuclear factor-κB pathway (46, 47), leading to cytoskeletal contraction that relaxes the TJ barrier. Thus, the epithelial sensing of various pathogen-associated molecular patterns by pattern recognition receptors positively or negatively regulates intestinal permeability at TJs.

Endogenous machinery to suppress TJs is regulated by zonulin, a eukaryotic analog of the ZO toxin produced by Vibrio cholerae (48). In humans, zonulin was identified as pre-haptoglobin (preHp)-2, the precursor of haptoglobin, which is enzymatically cleaved into the mature protein (49). Zonulin was released when mammalian small intestinal tissues were cocultured with pathogenic and nonpathogenic bacteria ex vivo (50). This observation suggested that bacterial exposure is a critical inducer of zonulin, although the underlying mechanism remains unclear. Furthermore, gliadin (a glycoprotein present in wheat)-dependent zonulin release is well-documented, especially in studies of celiac disease. Gliadin binds to the chemokine receptor CXCR3 (expressed by intestinal epithelial cells) to facilitate zonulin secretion in the MyD88-dependent pathway (51). Zonulin possesses epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like and proteinase-activated receptor 2 (PAR2)-activating peptide-like motifs; thus, it serves as a ligand for EGF receptor (EGFR) and PAR2 on intestinal epithelial cells (49). Zonulin-dependent activation of PAR2 reinforces EGFR signaling, which further activates PKC and leads to the phosphorylation of ZO-1 and myosin 1C (52). This sequence of events disrupts the associations of ZO-1 with the other TJ molecules and myosin 1C. Activated PKC also phosphorylates G-actin and causes actin polymerization (53). These effects of PKC activation synergistically promote TJ disassembly and enhance intestinal permeability. However, considering that TLR2 signaling-dependent activation of PKC recruits ZO-1 to TJs, the effect of PKC on TJ assembly remains controversial and may depend on the targets of phosphorylation. Furthermore, EGFR activation by EGF in the breast milk inhibits TLR4 signaling to protect neonates and infants from necrotizing enterocolitis (21). Thus, the effect of EGFR signaling on epithelial barrier functions may be context-dependent. In patients with celiac disease, the expression of CXCR3 is upregulated in the small intestine, including the epithelium (51). This event may enhance zonulin secretion, thereby causing barrier dysfunction and an inflammatory response to gluten.

The biological impact of zonulin on the intestinal epithelial barrier and the immune system has been defined in studies of zonulin-overexpressing mice, in which the mouse Hp1 gene is replaced with the human Hp2 (hHp2) gene (29). Consequently, hHp2 knock-in enhanced intestinal permeability and promoted the development of dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced colitis (54). hHp2 knock-in mice also exhibited a proinflammatory immune response mediated by RORγt+ cells, especially IL7R+ CD3- RORγt+ (most likely, group 3) innate lymphoid cells in the small intestine (55). These data illustrate that zonulin overexpression may be implicated in the pathogenesis of chronic inflammatory diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease, and autoimmune diseases (56). Indeed, the serum concentrations of zonulin were significantly elevated in patients with multiple sclerosis, ankylosing spondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis and type 1 diabetes compared with those concentrations in healthy volunteers (22, 24, 57, 58). Furthermore, enhanced intestinal permeability, combined with the upregulation of zonulin and downregulation of TJ-related proteins, was evident in mice with collagen-induced arthritis, a model of rheumatoid arthritis (24). Importantly, these pathological events were observed before the onset of arthritis; treatment with a zonulin antagonist, larazotide, ameliorated the disease symptoms by improving barrier function. Thus, LGS mediated by zonulin most likely contributes to the development of collagen-induced arthritis. In human clinical trials, larazotide acetate also improved the symptoms in patients with celiac disease (59). Taken together, these observations support the importance of zonulin as a biomarker of intestinal permeability and a promising therapeutic target for LGS-associated autoimmune diseases (Table 1). Nevertheless, recent reports have shown that zonulin is inappropriate as a biomarker for irritative bowel syndrome, functional dyspepsia and non-Coeliac wheat sensitivity (60). There was only a weak correlation between zonulin level and intestinal permeability (61). This could be due to the detection method; widely distributed ELISA for zonulin measurement fails to quantify zonulin levels correctly. It is, therefore, paramount to establish the precise measurement system and to further investigate the causal relationship of zonulin and LGS-associated diseases using animal models like hHP2 knock-in mice.

Barrier Maintenance by Microbial Products

The commensal microbiota produces a considerable amount of various fermentation products (62), such as short-chain fatty acids (derived from dietary fibers and mucin glycans) (63), indoles (derived from tryptophan), and hydroxy fatty acids (derived from unsaturated long-chain fatty acids). Therefore, the commensal microbiota is often regarded as “a hidden organ.” Commensal microbiota-derived metabolites have substantial impacts on host physiological functions through metabolic reprograming (64), epigenetic modifications (65), and the activation of specific receptors like G protein-coupled receptors (GPRs) and aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR). There is increasing evidence that microbial metabolites can serve as exogenous regulators for the TJ barrier. For instance, butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid, augments the TJ barrier by inducing the hypoxia response. Colonocytes actively utilize butyrate as a critical energy source via beta-oxidation and subsequent oxidative phosphorylation. This metabolic process, which requires oxygen consumption, contributes to the establishment of anaerobic conditions in the colonic lumen and results in the stabilization of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) in colonocytes (66). Consequently, butyrate upregulates Cldn1 (encoding Claudin-1) and Ocln (encoding occludin) in a HIF-1-dependent manner, thereby conferring resistance to barrier disruption and bacterial translocation upon infection with Clostridium difficile (67).

Microbial indoles also regulate the integrity of TJs. In intestinal epithelial cells, indole-3-propionic acid downregulates TNF-α and upregulates TJ-related proteins in a pregnane X receptor (PXR)-dependent manner (68). PXR-deficient mice exhibit an LGS-like phenotype and high susceptibility to indomethacin-induced enteritis. Because PXR/TLR4-double deficiency rescues the LGS-like phenotype, indole-3-propionic acid presumably counteracts TLR4-mediated barrier dysfunction. Additionally, oral administration of indole-3-ethanol, indole-3-pyruvate, and indole-3-aldehyde mitigates DSS-induced colitis by securing the TJ barrier in an AhR-dependent manner (69). AhR signaling downregulates the expression of MLCK, which results in the dephosphorylation (and subsequent activation) of non-muscle myosin II-A and ezrin under inflammatory conditions. Importantly, both myosin II-A and ezrin are TJ-associated actin regulatory proteins that can destabilize TJ complexes (70, 71).

Urolithin A (derived from polyphenols) also acts as a TJ modulator through AhR signaling (72). Urolithin A-dependent activation of AhR upregulates the expression levels of Cldn4, Ocln, and ZO-1 by inducing Cyp1A1 and Nrf2. The administration of urolithin A mitigates barrier dysfunction and colitis development in the mouse model of 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid-induced colitis; this protective effect is attenuated in mice lacking either Nrf2 or AhR. These findings imply that urolithin A requires both AhR- and Nrf2-dependent pathways to enhance the TJ barrier.

Gut-resident Lactobacillus spp. produces unique hydroxy fatty acids such as 10-hydroxy-cis-12-octadecenoic acid (HYA) (73). HYA binds to GPR40 on Caco-2 intestinal epithelial cells to activate the mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular-signal-regulated kinase pathway, thereby upregulating TJ-related proteins (74). Treatment with HYA was protective against IFN-γ and TNF-α-induced barrier disruption in vitro and the development of DSS-induced colitis in vivo. Furthermore, HYA considerably enhances the fecal IgA concentration in the NC/nga mouse model of atopic dermatitis (75), indicating that the protective effect of HYA on the colitis model may be attributed to the reinforcement of an epithelial barrier and an augmented S-IgA response.

Multiple lines of investigation have suggested that epithelial barrier dysfunction may result from the loss of beneficial species due to intestinal dysbiosis. In db/db mice that spontaneously develop type 2 diabetes, epithelial dysfunction is accompanied by underrepresentation of the major butyrate producer, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii (76). F. prausnitzii is also nearly absent from Crohn’s disease-associated gut microbiota (63, 77). Importantly, F. prausnitzii produces microbial anti-inflammatory molecule, which consolidates TJ integrity by upregulating ZO-1. Treatment of db/db mice with the F. prausnitzii-derived anti-inflammatory molecule restored ZO-1 expression and improved intestinal permeability. Additionally, the outer membrane protein of Akkermansia muciniphila, Amuc_1000*, upregulates Cldn3 and Ocln at least partially through the activation of TLR2 signaling (78). High-fat diet (HFD)-induced obesity is associated with a lower abundance of A. muciniphila, while the administration of Amuc_1000* reduces body fat mass by alleviating HFD-induced endotoxemia. Notably, A. muciniphila is regarded as a mucin-degrading species, which may affect the mucin barrier (79, 80). Taken together, these observations imply that specific symbionts shape epithelial barrier function by providing beneficial metabolites and proteins.

Barrier Disruption by Specific Microbes

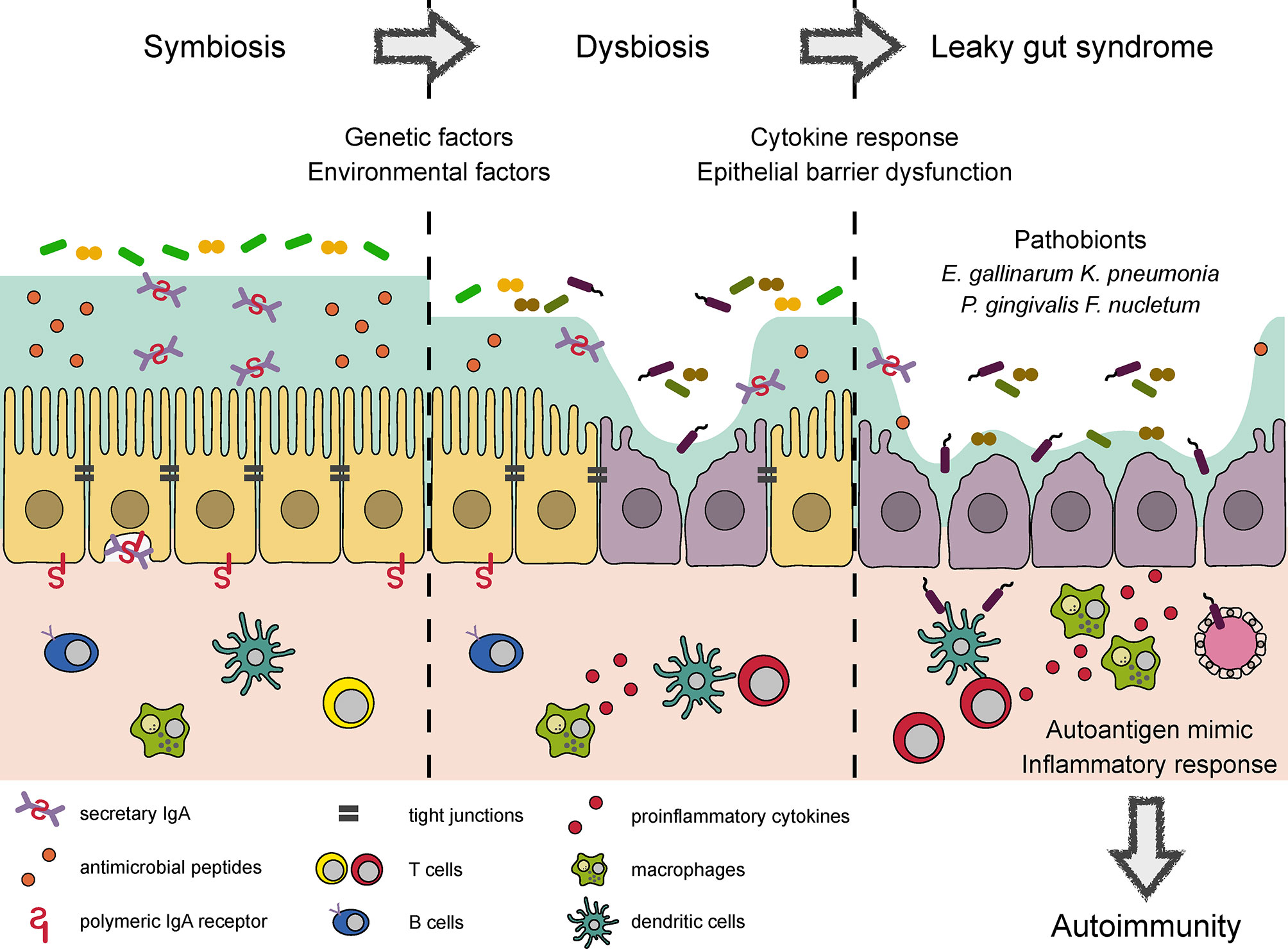

Intestinal pathobionts are often overrepresented in the microbiota of patients with inflammatory disorders, where they accelerate systemic inflammation by translocating across the epithelial barrier to reach extraintestinal tissue (Figure 1). A notable example of such pathobionts is Enterococcus gallinarum, which is frequently detected in the livers of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and autoimmune hepatitis (81). In systemic lupus erythematosus model (NZW × BXSB F1 hybrid) mice, colonization by E. gallinarum caused barrier dysfunction and bacterial translocation to the liver, thereby exacerbating autoantibody production through the upregulation of hepatic autoantigen expression. The monoassociation of E. gallinarum in germ-free mice also recapitulated an LGS-like phenotype with enhanced bacterial translocation to the liver, presumably due to the induction of Hp/zonulin and the reciprocal downregulation of TJ-related molecules (e.g., Cldn3 and Ocln).

Figure 1 Conceptual diagram of autoimmune responses induced by dysbiosis and LGS. Several bacterial products reinforce epithelial barrier and regulate the mucosal immune response to maintain symbiotic relationship in the intestine. Environmental factors such as a westernized diet and drugs cause dysbiosis, which impairs epithelial barrier function and elicits proinflammatory response. Microbial adhesion to epithelial cells and the induction of proinflammatory cytokines further damage TJ integrity, leading to LGS. LGS enhances bacterial translocation to the systemic circulation. Some of the translocated bacteria provide mimotopes or serve as adjuvants to initiate or worsen autoimmune responses, respectively.

Patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) possess several bacterial species with barrier-disrupting property (82). More than 70% of patients with PSC exhibit comorbid ulcerative colitis (UC). Fecal microbiota transplantation from PSC-UC patients to germ-free mice provoked systemic translocation of E. gallinarum, Proteus mirabilis, and Klebsiella pneumonia. Among these species, K. pneumonia can damage epithelial cells, leading to enhanced intestinal permeability. Eventually, colonization by the PSC-UC microbiota or a mixture of the three bacterial strains exacerbated of 3,5-dicarbethoxyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine-induced hepatobiliary injury by activating hepatic Th17 response.

There is compelling evidence for a link between oral and gut microbiota. In particular, oral dysbiosis and proton pump inhibitor usage facilitate the translocation of otherwise oral-indigenous bacteria to the intestine (83). Importantly, Porphyromonas gingivalis, a periodontopathic bacterium, may predispose hosts to systemic inflammation and autoimmunity by inducing LGS. In support of this view, the administration of P. gingivalis has been shown to alter the gut microbial composition and suppress the expression of TJ-related proteins, thereby augmenting the systemic translocation of bacteria and their products (84, 85). The administration of P. gingivalis accelerates metabolic syndrome, collagen-induced arthritis, and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) (84, 86, 87). Another oral microbe, Fusobacterium nucleatum, also induces intestinal dysbiosis and LGS by suppressing the expression of both ZO-1 and occluding. Therefore, F. nucleatum-treated mice are highly susceptible to DSS-induced colitis (88). Notably, F. nucleatum is often detected in patients with colorectal carcinoma (89, 90). Based on these data, specific oral pathobionts presumably play vital roles in the development of inflammatory disorders through LGS (Figure 1). However, the underlying mechanism by which oral pathobionts disrupt the gut microbial community remains to be elucidated.

Pathological Contribution of Dysbiosis and LGS to Autoimmune Diseases

Exogenous (e.g., diet and drugs) and endogenous factors (e.g., antimicrobial peptides, S-IgA, and the mucin layer) are known to affect the gut microbial community. For instance, a HFD reduces the abundance of Bacteroidetes and reciprocally enhances the abundances of Firmicutes and Proteobacteria (91). Low-fiber diet and high-glucose intake enhance the proportions of mucin-degrading bacteria (79, 80). These findings suggest that a westernized diet affects the microbial community. Antibiotics is another major contributor to alter microbial composition (92); as mentioned above, proton pump inhibitors also promote the translocation of oral pathobionts to the intestine (83).

In addition, mutations in several genes (i.e., NOD2 and XBP1) and the presence of environmental stress (e.g., obesity and irradiation) causes Paneth cell dysfunction, which impairs the secretion of antimicrobial peptides and causes dysbiosis (93). Furthermore, patients with selective IgA deficiency who have serum IgA concentrations of < 7 mg/dL exhibit intestinal dysbiosis and high susceptibility to allergic and autoimmune diseases (e.g., type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus) (94–96). Sutterella spp. are known to possess S-IgA-degrading activity (97). Colonization with Sutterella spp. enhances susceptibility to DSS-induced colitis by reducing the amount of luminal S-IgA.

Polarized protein sorting abnormalities cause barrier dysfunction and dysbiosis. In polarized epithelium, adaptor protein-1B (AP-1B) complex mediates clathrin-dependent polarized protein sorting (98). We previously showed that a deficiency of Ap1m2 (encoding the μ1B subunit of AP-1B complex) interferes with the basolateral sorting of several cytokine receptors (e.g., IL-6st, IL-17RA, tumor necrosis factor-RII, and transforming growth factor-βRI) (99). These abnormalities attenuate cytokine signaling and downregulate the expression of antimicrobial peptides in the intestinal epithelium. Ap1m2 deficiency also disturbs IgA transcytosis to the intestinal lumen due to the inappropriate sorting of polymeric immunoglobulin receptor. Consequently, Ap1m2-deficient mice exhibit dysbiosis and LGS, leading to the spontaneous development of Th17-mediated chronic colitis. The importance of AP-1B-mediated maintenance of epithelial integrity in systemic immune homeostasis is currently under investigation.

Microbial adhesion to the epithelium could initiate a sequence of inflammatory responses by activating signal transduction via TLRs and zonulin signaling, leading to the loss of TJ integrity. Such chronic barrier dysfunction causes bacterial translocation and an inflammatory response that further damages the TJ barrier and also induce epithelium apoptosis by inflammatory cytokines (100). This vicious cycle potentiates the autoimmune response in genetically susceptible patients and may trigger an acquired autoimmune response even in genetically normal individuals. Indeed, an experimental observation has verified that LGS promotes genetically induced autoimmunity. Induction of LGS by DSS administration leads to the activation of autoreactive T cells in the intestine of type 1 diabetes model NOD mice carrying an islet-reactive T cell receptor (101). Eventually, this response elicits diabetes; however, antibiotics treatment canceled the disease development.

Accumulating evidence implies that cross-reactivity to microbial antigens may trigger autoimmune responses. Common microbial peptides (GTP-binding protein engA) with homology to myelin basic protein induce the antigen-specific T cell response by low-affinity T cell recognition (102). In this study, the humanized mice carrying HLA-DR2 haplotype (DRB1*1501) and myelin basic protein-specific human T cell receptor developed multiple sclerosis-like symptoms upon immunization with the microbial peptides. Besides, P. gingivalis may act as a mimic antigen to induce autoimmunity. It is well documented that patients with rheumatoid arthritis possess antibodies against anti-citrullinated proteins such as α-enolase, contributing to the pathogenesis (103). Human α-enolase shares homology with P. gingivalis-derived α-enolase, and thereby the human citrullinated α-enolase-specific antibodies cross-reacts with citrullinated P. gingivalis α-enolase (104). Ruff et al. recently demonstrated that the DNA methyltransferase of Roseburia intestinalis, a major commensal species, also serves as a mimotope of human β2-glycoprotein I in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome (105). This mimotope presumably facilitates the generation of autoreactive Th1 cells and autoantibodies. Administration of R. intestinalis to NZW × BXSB F1 hybrid mice causes antiphospholipid syndrome-like symptoms by inducing autoimmunity to β2-glycoprotein I. Miyauchi et al. also revealed that The UvrABC system protein A (UvrA) expressed by Lactobacillus reuteri is a mimotope of mouse myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein, an antigen used to induce EAE (106). Monoassociation by L. reuteri alone moderately promotes EAE progression; however, co-association with Erysipelotrichaceae possessing an epithelium-attaching property markedly worsens disease progression.

Segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) also attaches to the ileal epithelium to elicit the intestinal immune response such as Th17 response. This effect is mediated by serum amyloid A and reactive oxygen species by epithelial cells (107). Antigen presentation of SFB-derived antigens by intestinal dendritic cells is also required to induce Th17 cells (108). Accordingly, colonization by SFB facilitated the development of EAE due to enhanced Th17 response (109). Meanwhile, the SFB-dependent Th17 response suppressed the bacterial translocation in constitutively MLCK-activated mice (110). Based on these observations, SFB could be a double-edged sword that consolidates the barrier integrity but augments the autoimmune response in a context-dependent manner.

Collectively, genetic and environmental factors affect the microbial composition, leading to epithelial barrier dysfunction directly and/or indirectly by means of inflammatory responses. These pathological changes enhance the systemic translocation of luminal bacteria, some of which provide mimotopes or augment autoimmune responses (Figure 1).

Conclusion and Perspectives

The commensal microbiota has critical regulatory influences on epithelial barrier function. While the dysbiosis-mediated induction of LGS initiates an inflammatory response, some microbial products reinforce TJ integrity. Given that the commensal microbiota contributes to the development of LGS-associated autoimmune diseases, interventions targeting the microbiota are emerging as new therapeutic strategies to prevent or cure autoimmune diseases. Probiotics and fecal microbiota transplantation have been investigated in clinical trials for the treatment of type 1 diabetes, multiple sclerosis, and rheumatoid arthritis (111, 112). However, the pathological mechanism underlying LGS-dependent autoimmunity remains mostly unknown. Moreover, the precise location (e.g., proximal or distal intestine) where epithelial barrier dysfunction occurs initially has yet to be determined. Further investigations using LGS model animals are needed to elucidate the pathogenesis and provide proof-of-concept for promising therapies for autoimmune diseases.

Author Contributions

YK wrote the manuscript and prepared the figure and table. KH critically revised the manuscript and obtained grants. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (20H00509, 20H05876, and JPJSBP 120207405 to KH), AMED-Crest (20gm1010004h0105 and 20gm1310009h0001 and to KH), and The Naito Foundation (KH).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Peterson LW, Artis D. Intestinal Epithelial Cells: Regulators of Barrier Function and Immune Homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol (2014) 14:141–53. doi: 10.1038/nri3608

2. Suzuki T. Regulation of Intestinal Epithelial Permeability by Tight Junctions. Cell Mol Life Sci (2013) 70:631–59. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1070-x

3. Furuse M, Hirase T, Itoh M, Nagafuchi A, Yonemura S, Tsukita S, et al. Occludin: A Novel Integral Membrane Protein Localizing At Tight Junctions. J Cell Biol (1993) 123:1777–88. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.6.1777

4. Furuse M, Fujita K, Hiiragi T, Fujimoto K, Tsukita S. Claudin-1 and -2: Novel Integral Membrane Proteins Localizing At Tight Junctions With No Sequence Similarity to Occludin. J Cell Biol (1998) 141:1539–50. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.7.1539

5. Gumbiner B, Lowenkopf T, Apatira D. Identification of a 160-kDa Polypeptide That Binds to the Tight Junction Protein ZO-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (1991) 88:3460–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3460

6. Fanning AS, Ma TY, Anderson JM. Isolation and Functional Characterization of the Actin Binding Region in the Tight Junction Protein ZO-1. FASEB J (2002) 16:1835–7. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0121fje

7. Madara JL, Moore R, Carlson S. Alteration of Intestinal Tight Junction Structure and Permeability by Cytoskeletal Contraction. Am J Physiol - Cell Physiol (1987) 253:C854–61. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1987.253.6.c854

8. Turner JR, Rill BK, Carlson SL, Carnes D, Kerner R, Mrsny RJ, et al. Physiological Regulation of Epithelial Tight Junctions is Associated With Myosin Light-Chain Phosphorylation. Am J Physiol - Cell Physiol (1997) 273:C1378–85. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.4.c1378

9. Johansson MEV, Hansson GC. Immunological Aspects of Intestinal Mucus and Mucins. Nat Rev Immunol (2016) 16:639–49. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.88

10. Bevins CL, Salzman NH. Paneth Cells, Antimicrobial Peptides and Maintenance of Intestinal Homeostasis. Nat Rev Microbiol (2011) 9:356–68. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2546

11. Johansen FE, Pekna M, Norderhaug IN, Haneberg B, Hietala MA, Krajci P, et al. Absence of Epithelial Immunoglobulin a Transport, With Increased Mucosal Leakiness, in Polymeric Immunoglobulin Receptor/Secretory Component-Deficient Mice. J Exp Med (1999) 190:915–21. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.7.915

12. Ahmad R, Sorrell MF, Batra SK, Dhawan P, Singh AB. Gut Permeability and Mucosal Inflammation: Bad, Good or Context Dependent. Mucosal Immunol (2017) 10:307–17. doi: 10.1038/mi.2016.128

13. Fasano A, Shea-Donohue T. Mechanisms of Disease: The Role of Intestinal Barrier Function in the Pathogenesis of Gastrointestinal Autoimmune Diseases. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol (2005) 2:416–22. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0259

14. Mu Q, Kirby J, Reilly CM, Luo XM. Leaky Gut as a Danger Signal for Autoimmune Diseases. Front Immunol (2017) 8:598. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00598

15. Belkaid Y, Harrison OJ. Homeostatic Immunity and the Microbiota. Immunity (2017) 46:562–76. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.04.008

16. Rooks MG, Garrett WS. Gut Microbiota, Metabolites and Host Immunity. Nat Rev Immunol (2016) 16:341–52. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.42

17. Round JL, Mazmanian SK. The Gut Microbiota Shapes Intestinal Immune Responses During Health and Disease. Nat Rev Immunol (2009) 9:313–23. doi: 10.1038/nri2515

18. Levy M, Kolodziejczyk AA, Thaiss CA, Elinav E. Dysbiosis and the Immune System. Nat Rev Immunol (2017) 17:219–32. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.7

19. Buscarinu MC, Romano S, Mechelli R, Pizzolato Umeton R, Ferraldeschi M, Fornasiero A, et al. Intestinal Permeability in Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis. Neurotherapeutics (2018) 15:68–74. doi: 10.1007/s13311-017-0582-3

20. Jangi S, Gandhi R, Cox LM, Li N, Von GF, Yan R, et al. Alterations of the Human Gut Microbiome in Multiple Sclerosis. Nat Commun (2016) 28:12015. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12015

21. Good M, Sodhi CP, Egan CE, Afrazi A, Jia H, Yamaguchi Y, et al. Breast Milk Protects Against the Development of Necrotizing Enterocolitis Through Inhibition of Toll-like Receptor 4 in the Intestinal Epithelium Via Activation of the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor. Mucosal Immunol (2015) 8:1166–79. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.30

22. Ciccia F, Guggino G, Rizzo A, Alessandro R, Luchetti MM, Milling S, et al. Dysbiosis and Zonulin Upregulation Alter Gut Epithelial and Vascular Barriers in Patients With Ankylosing Spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis (2017) 76:1123–32. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210000

23. Wen C, Zheng Z, Shao T, Liu L, Xie Z, Le Chatelier E, et al. Quantitative Metagenomics Reveals Unique Gut Microbiome Biomarkers in Ankylosing Spondylitis. Genome Biol (2017) 18:142. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1271-6

24. Tajik N, Frech M, Schulz O, Schälter F, Lucas S, Azizov V, et al. Targeting Zonulin and Intestinal Epithelial Barrier Function to Prevent Onset of Arthritis. Nat Commun (2020) 11:1995. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15831-7

25. Scher JU, Sczesnak A, Longman RS, Segata N, Ubeda C, Bielski C, et al. Expansion of Intestinal Prevotella Copri Correlates With Enhanced Susceptibility to Arthritis. Elife (2013) 2:e01202. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01202.001

26. Lin R, Zhou L, Zhang J, Wang B. Abnormal Intestinal Permeability and Microbiota in Patients With Autoimmune Hepatitis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol (2015) 8:5153–60.

27. Harbison JE, Roth-Schulze AJ, Giles LC, Tran CD, Ngui KM, Penno MA, et al. Gut Microbiome Dysbiosis and Increased Intestinal Permeability in Children With Islet Autoimmunity and Type 1 Diabetes: A Prospective Cohort Study. Pediatr Diabetes (2019) 20:574–83. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12865

28. De Goffau MC, Luopajärvi K, Knip M, Ilonen J, Ruohtula T, Härkönen T, et al. Fecal Microbiota Composition Differs Between Children With β-Cell Autoimmunity and Those Without. Diabetes (2013) 62:1238–44. doi: 10.2337/db12-0526

29. Levy AP, Levy JE, Kalet-Litman S, Miller-Lotan R, Levy NS, Asaf R, et al. Haptoglobin Genotype is a Determinant of Iron, Lipid Peroxidation, and Macrophage Accumulation in the Atherosclerotic Plaque. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol (2007) 27:134–40. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000251020.24399.a2

30. Sapone A, Lammers KM, Casolaro V, Cammarota M, Giuliano MT, De Rosa M, et al. Divergence of Gut Permeability and Mucosal Immune Gene Expression in Two Gluten-Associated Conditions: Celiac Disease and Gluten Sensitivity. BMC Med (2011) 9:23. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-23

31. Sánchez E, Donat E, Ribes-Koninckx C, Fernández-Murga ML, Sanz Y. Duodenal-Mucosal Bacteria Associated With Celiac Disease in Children. Appl Environ Microbiol (2013) 79:5472–9. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00869-13

32. Ayyappan P, Harms RZ, Buckner JH, Sarvetnick NE. Coordinated Induction of Antimicrobial Response Factors in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Front Immunol (2019) 10:658. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00658

33. Hevia A, Milani C, López P, Cuervo A, Arboleya S, Duranti S, et al. Intestinal Dysbiosis Associated With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. MBio (2014) 5:1548–62. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01548-14

34. Ye D, Ma I, Ma TY. Molecular Mechanism of Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Modulation of Intestinal Epithelial Tight Junction Barrier. Am J Physiol - Gastrointest Liver Physiol (2006) 290:496–504. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00318.2005

35. Mankertz J, Amasheh M, Krug SM, Fromm A, Amasheh S, Hillenbrand B, et al. Tnfα Up-Regulates Claudin-2 Expression in Epithelial HT-29/B6 Cells Via phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase Signaling. Cell Tissue Res (2009) 336:67–77. doi: 10.1007/s00441-009-0751-8

36. Bruewer M, Utech M, Ivanov AI, Hopkins AM, Parkos CA, Nusrat A. Interferon-γ Induces Internalization of Epithelial Tight Junction Proteins Via a Macropinocytosis-Like Process. FASEB J (2005) 19:923–33. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3260com

37. Madsen KL, Lewis SA, Tavernini MM, Hibbard J, Fedorak RN. Interleukin 10 Prevents Cytokine-Induced Disruption of T84 Monolayer Barrier Integrity and Limits Chloride Secretion. Gastroenterology (1997) 113:151–9. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(97)70090-8

38. Howe KL, Reardon C, Wang A, Nazli A, McKay DM. Transforming Growth Factor-β Regulation of Epithelial Tight Junction Proteins Enhances Barrier Function and Blocks Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia Coli O157:H7-induced Increased Permeability. Am J Pathol (2005) 167:1587–97. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61243-6

39. Keir ME, Yi T, Lu TT, Ghilardi N. The Role of IL-22 in Intestinal Health and Disease. J Exp Med (2020) 217:e20192195. doi: 10.1084/jem.20192195

40. Tsai PY, Zhang B, He WQ, Zha JM, Odenwald MA, Singh G, et al. Il-22 Upregulates Epithelial Claudin-2 to Drive Diarrhea and Enteric Pathogen Clearance. Cell Host Microbe (2017) 21:671–81.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.05.009

41. Schmechel S, Konrad A, Diegelmann J, Glas J, Wetzke M, Paschos E, et al. Linking Genetic Susceptibility to Crohn’s Disease With Th17 Cell Function: IL-22 Serum Levels are Increased in Crohn’s Disease and Correlate With Disease Activity and IL23R Genotype Status. Inflammation Bowel Dis (2008) 14:204–12. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20315

42. Zeissig S, Bürgel N, Günzel D, Richter J, Mankertz J, Wahnschaffe U, et al. Changes in Expression and Distribution of Claudin 2, 5 and 8 Lead to Discontinuous Tight Junctions and Barrier Dysfunction in Active Crohn’s Disease. Gut (2007) 56:61–72. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.094375

43. Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pattern Recognition Receptors and Inflammation. Cell (2010) 140:805–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.022

44. Cario E, Gerken G, Podolsky DK. Toll-Like Receptor 2 Enhances ZO-1-associated Intestinal Epithelial Barrier Integrity Via Protein Kinase C. Gastroenterology (2004) 127:224–38. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.04.015

45. Guo S, Al-Sadi R, Said HM, Ma TY. Lipopolysaccharide Causes an Increase in Intestinal Tight Junction Permeability In Vitro and In Vivo by Inducing Enterocyte Membrane Expression and Localization of TLR-4 and CD14. Am J Pathol (2013) 182:375–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.10.014

46. Nighot M, Al-Sadi R, Guo S, Rawat M, Nighot P, Watterson MD, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Increase in Intestinal Epithelial Tight Permeability Is Mediated by Toll-Like Receptor 4/Myeloid Differentiation Primary Response 88 (Myd88) Activation of Myosin Light Chain Kinase Expression. Am J Pathol (2017) 187:2698–710. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2017.08.005

47. Nighot M, Rawat M, Al-Sadi R, Castillo EF, Nighot P, Ma TY. Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Increase in Intestinal Permeability Is Mediated by TAK-1 Activation of IKK and MLCK/MYLK Gene. Am J Pathol (2019) 189:797–812. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2018.12.016

48. Wang W, Uzzau S, Goldblum SE, Fasano A. Human Zonulin, a Potential Modulator of Intestinal Tight Junctions. J Cell Sci (2000) 113(Pt 24):4435–40.

49. Tripathi A, Lammers KM, Goldblum S, Shea-Donohue T, Netzel-Arnett S, Buzza MS, et al. Identification of Human Zonulin, a Physiological Modulator of Tight Junctions, as Prehaptoglobin-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2009) 106:16799–804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906773106

50. Asmar R, Panigrahi P, Bamford P, Berti I, Not T, Coppa GV, et al. Host-Dependent Zonulin Secretion Causes the Impairment of the Small Intestine Barrier Function After Bacterial Exposure. Gastroenterology (2002) 123:1607–15. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.36578

51. Lammers KM, Lu R, Brownley J, Lu B, Gerard C, Thomas K, et al. Gliadin Induces an Increase in Intestinal Permeability and Zonulin Release by Binding to the Chemokine Receptor Cxcr3. Gastroenterology (2008) 135:194–204.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.023

52. Goldblum SE, Rai U, Tripathi A, Thakar M, De Leo L, Di Toro N, et al. The Active Zot Domain (Aa 288–293) Increases ZO-1 and Myosin 1C Serine/Threonine Phosphorylation, Alters Interaction Between ZO-1 and its Binding Partners, and Induces Tight Junction Disassembly Through Proteinase Activated Receptor 2 Activation. FASEB J (2011) 25:144–58. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-158972

53. Fasano A, Fiorentini C, Donelli G, Uzzau S, Kaper JB, Margaretten K, et al. Zonula Occludens Toxin Modulates Tight Junctions Through Protein Kinase C-dependent Actin Reorganization, In Vitro. J Clin Invest (1995) 96:710–20. doi: 10.1172/JCI118114

54. Sturgeon C, Lan J, Fasano A. Zonulin Transgenic Mice Show Altered Gut Permeability and Increased Morbidity/Mortality in the DSS Colitis Model. Ann N Y Acad Sci (2017) 1397:130–42. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13343

55. Miranda-Ribera A, Ennamorati M, Serena G, Cetinbas M, Lan J, Sadreyev RI, et al. Exploiting the Zonulin Mouse Model to Establish the Role of Primary Impaired Gut Barrier Function on Microbiota Composition and Immune Profiles. Front Immunol (2019) 10:2233. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02233

56. Sturgeon C, Fasano A. Zonulin, a Regulator of Epithelial and Endothelial Barrier Functions, and its Involvement in Chronic Inflammatory Diseases. Tissue Barriers (2016) 4:e1251384. doi: 10.1080/21688370.2016.1251384

57. Camara-Lemarroy CR, Silva C, Greenfield J, Liu W-Q, Metz LM, Yong VW. Biomarkers of Intestinal Barrier Function in Multiple Sclerosis are Associated With Disease Activity. Mult Scler (2019) 26:1340–50. doi: 10.1177/1352458519863133

58. Sapone A, De Magistris L, Pietzak M, Clemente MG, Tripathi A, Cucca F, et al. Zonulin Upregulation is Associated With Increased Gut Permeability in Subjects With Type 1 Diabetes and Their Relatives. Diabetes (2006) 55:1443–9. doi: 10.2337/db05-1593

59. Leffler DA, Kelly CP, Green PHR, Fedorak RN, Dimarino A, Perrow W, et al. Larazotide Acetate for Persistent Symptoms of Celiac Disease Despite a Gluten-Free Diet: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Gastroenterology (2015) 148:1311–9.e6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.02.008

60. Talley NJ, Holtmann GJ, Jones M, Koloski NA, Walker MM, Burns G, et al. Zonulin in Serum as a Biomarker Fails to IdentifyFunctional Dyspepsia and non-Coeliac Wheat Sensitivity. Gut (2020) 69:1719–22. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318664

61. Massier L, Chakaroun R, Kovacs P, Heiker JT. Blurring the Picture in Leaky Gut Research: How Shortcomings of Zonulin as a Biomarker Mislead the Field of Intestinal Permeability. Gut (2020) 9:gutjnl–2020-323026. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323026

62. Krautkramer KA, Fan J, Bäckhed F. Gut Microbial Metabolites as Multi-Kingdom Intermediates. Nat Rev Microbiol (2020) 19:77–94. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-0438-4

63. Yamada T, Hino S, Iijima H, Genda T, Aoki R, Nagata R, et al. Mucin O-glycans Facilitate Symbiosynthesis to Maintain Gut Immune Homeostasis. EBioMedicine (2019) 48:513–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.09.008

64. Kim M, Qie Y, Park J, Kim CH. Gut Microbial Metabolites Fuel Host Antibody Responses. Cell Host Microbe (2016) 20:202–14. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.07.001

65. Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Fukuda S, Endo TA, Nakato G, Takahashi D, et al. Commensal Microbe-Derived Butyrate Induces the Differentiation of Colonic Regulatory T Cells. Nature (2013) 504:446–50. doi: 10.1038/nature12721

66. Kelly CJ, Zheng L, Campbell EL, Saeedi B, Scholz CC, Bayless AJ, et al. Crosstalk Between Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Intestinal Epithelial HIF Augments Tissue Barrier Function. Cell Host Microbe (2015) 17:662–71. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.03.005

67. Fachi JL, Felipe J de S, Pral LP, da Silva BK, Corrêa RO, de Andrade MCP, et al. Butyrate Protects Mice From Clostridium Difficile-Induced Colitis Through an HIF-1-Dependent Mechanism. Cell Rep (2019) 27:750–61.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.03.054

68. Venkatesh M, Mukherjee S, Wang H, Li H, Sun K, Benechet AP, et al. Symbiotic Bacterial Metabolites Regulate Gastrointestinal Barrier Function Via the Xenobiotic Sensor PXR and Toll-Like Receptor 4. Immunity (2014) 41:296–310. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.014

69. Scott SA, Fu J, Chang PV. Microbial Tryptophan Metabolites Regulate Gut Barrier Function Via the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2020) 117:19376–87. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2000047117

70. Vicente-Manzanares M, Ma X, Adelstein RS, Horwitz AR. Non-Muscle Myosin II Takes Centre Stage in Cell Adhesion and Migration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol (2009) 10:778–90. doi: 10.1038/nrm2786

71. Fehon RG, McClatchey AI, Bretscher A. Organizing the Cell Cortex: The Role of ERM Proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol (2010) 11:276–87. doi: 10.1038/nrm2866

72. Singh R, Chandrashekharappa S, Bodduluri SR, Baby BV, Hegde B, Kotla NG, et al. Enhancement of the Gut Barrier Integrity by a Microbial Metabolite Through the Nrf2 Pathway. Nat Commun (2019) 10:1–18. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07859-7

73. Kishino S, Takeuchi M, Park SB, Hirata A, Kitamura N, Kunisawa J, et al. Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Saturation by Gut Lactic Acid Bacteria Affecting Host Lipid Composition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2013) 110:17808–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312937110

74. Miyamoto J, Mizukure T, Park SB, Kishino S, Kimura I, Hirano K, et al. A Gut Microbial Metabolite of Linoleic Acid, 10-hydroxy-cis-12-octadecenoic Acid, Ameliorates Intestinal Epithelial Barrier Impairment Partially Via GPR40-MEK-ERK Pathway. J Biol Chem (2015) 290:2902–18. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.610733

75. Kaikiri H, Miyamoto J, Kawakami T, Park SB, Kitamura N, Kishino S, et al. Supplemental Feeding of a Gut Microbial Metabolite of Linoleic Acid, 10-hydroxy-cis-12-octadecenoic Acid, Alleviates Spontaneous Atopic Dermatitis and Modulates Intestinal Microbiota in NC/nga Mice. Int J Food Sci Nutr (2017) 68:941–51. doi: 10.1080/09637486.2017.1318116

76. Xu J, Liang R, Zhang W, Tian K, Li J, Chen X, et al. Faecalibacterium Prausnitzii -Derived Microbial Anti-Inflammatory Molecule Regulates Intestinal Integrity in Diabetes Mellitus Mice Via Modulating Tight Junction Protein Expression. J Diabetes (2020) 12:224–36. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12986

77. Quévrain E, Maubert MA, Michon C, Chain F, Marquant R, Tailhades J, et al. Identification of an Anti-Inflammatory Protein From Faecalibacterium Prausnitzii, a Commensal Bacterium Deficient in Crohn’s Disease. Gut (2016) 65:415–25. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307649

78. Plovier H, Everard A, Druart C, Depommier C, Van Hul M, Geurts L, et al. A Purified Membrane Protein From Akkermansia Muciniphila or the Pasteurized Bacterium Improves Metabolism in Obese and Diabetic Mice. Nat Med (2017) 23:107–13. doi: 10.1038/nm.4236

79. Desai MS, Seekatz AM, Koropatkin NM, Kamada N, Hickey CA, Wolter M, et al. A Dietary Fiber-Deprived Gut Microbiota Degrades the Colonic Mucus Barrier and Enhances Pathogen Susceptibility. Cell (2016) 167:1339–53.e21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.043

80. Khan S, Waliullah S, Godfrey V, Khan MAW, Ramachandran RA, Cantarel BL, et al. Dietary Simple Sugars Alter Microbial Ecology in the Gut and Promote Colitis in Mice. Sci Transl Med (2020) 12:eaay6218. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aay6218

81. Manfredo Vieira S, Hiltensperger M, Kumar V, Zegarra-Ruiz D, Dehner C, Khan N, et al. Translocation of a Gut Pathobiont Drives Autoimmunity in Mice and Humans. Science (80-) (2018) 359:1156–61. doi: 10.1126/science.aar7201

82. Nakamoto N, Sasaki N, Aoki R, Miyamoto K, Suda W, Teratani T, et al. Gut Pathobionts Underlie Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction and Liver T Helper 17 Cell Immune Response in Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis. Nat Microbiol (2019) 4:492–503. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0333-1

83. Imhann F, Bonder MJ, Vila AV, Fu J, Mujagic Z, Vork L, et al. Proton Pump Inhibitors Affect the Gut Microbiome. Gut (2016) 65:740–8. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310376

84. Arimatsu K, Yamada H, Miyazawa H, Minagawa T, Nakajima M, Ryder MI, et al. Oral Pathobiont Induces Systemic Inflammation and Metabolic Changes Associated With Alteration of Gut Microbiota. Sci Rep (2014) 4:1–9. doi: 10.1038/srep04828

85. Nakajima M, Arimatsu K, Kato T, Matsuda Y, Minagawa T, Takahashi N, et al. Oral Administration of P. Gingivalis Induces Dysbiosis of Gut Microbiota and Impaired Barrier Function Leading to Dissemination of Enterobacteria to the Liver. PloS One (2015) 10:e0134234. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134234

86. Sato K, Takahashi N, Kato T, Matsuda Y, Yokoji M, Yamada M, et al. Aggravation of Collagen-Induced Arthritis by Orally Administered Porphyromonas Gingivalis Through Modulation of the Gut Microbiota and Gut Immune System. Sci Rep (2017) 7:6955. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07196-7

87. Polak D, Shmueli A, Brenner T, Shapira L. Oral Infection With P. Gingivalis Exacerbates Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. J Periodontol (2018) 89:1461–6. doi: 10.1002/JPER.17-0531

88. Liu H, Hong XL, Sun TT, Huang XW, Wang JL, Xiong H. Fusobacterium Nucleatum Exacerbates Colitis by Damaging Epithelial Barriers and Inducing Aberrant Inflammation. J Dig Dis (2020) 21:385–98. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12909

89. Castellarin M, Warren RL, Freeman JD, Dreolini L, Krzywinski M, Strauss J, et al. Fusobacterium Nucleatum Infection is Prevalent in Human Colorectal Carcinoma. Genome Res (2012) 22:299–306. doi: 10.1101/gr.126516.111

90. Kostic AD, Gevers D, Pedamallu CS, Michaud M, Duke F, Earl AM, et al. Genomic Analysis Identifies Association of Fusobacterium With Colorectal Carcinoma. Genome Res (2012) 22:292–8. doi: 10.1101/gr.126573.111

91. Zhang C, Zhang M, Pang X, Zhao Y, Wang L, Zhao L. Structural Resilience of the Gut Microbiota in Adult Mice Under High-Fat Dietary Perturbations. ISME J (2012) 6:1848–57. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.27

92. Feng Y, Huang Y, Wang Y, Wang P, Song H, Wang F. Antibiotics Induced Intestinal Tight Junction Barrier Dysfunction is Associated With Microbiota Dysbiosis, Activated NLRP3 Inflammasome and Autophagy. PloS One (2019) 14:e0218384. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218384

93. Salzman NH, Bevins CL. Dysbiosis-a Consequence of Paneth Cell Dysfunction. Semin Immunol (2013) 25:334–41. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2013.09.006

94. Berbers RM, Franken IA, Leavis HL. Immunoglobulin A and Microbiota in Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol (2019) 19:563–70. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000581

95. Jorgensen GH, Gardulf A, Sigurdsson MI, Sigurdardottir ST, Thorsteinsdottir I, Gudmundsson S, et al. Clinical Symptoms in Adults With Selective IgA Deficiency: A Case-Control Study. J Clin Immunol (2013) 33:742–7. doi: 10.1007/s10875-012-9858-x

96. Ludvigsson JF, Neovius M, Hammarström L. Association Between IgA Deficiency & Other Autoimmune Conditions: A Population-Based Matched Cohort Study. J Clin Immunol (2014) 34:444–51. doi: 10.1007/s10875-014-0009-4

97. Moon C, Baldridge MT, Wallace MA, Burnham CAD, Virgin HW, Stappenbeck TS. Vertically Transmitted Faecal IgA Levels Determine Extra-Chromosomal Phenotypic Variation. Nature (2015) 521:90–3. doi: 10.1038/nature14139

98. Fölsch H, Ohno H, Bonifacino JS, Mellman I. A Novel Clathrin Adaptor Complex Mediates Basolateral Targeting in Polarized Epithelial Cells. Cell (1999) 99:189–98. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81650-5

99. Takahashi D, Hase K, Kimura S, Nakatsu F, Ohmae M. The Epithelia-Specific Membrane Trafficking Factor AP-1B Controls Gut Immune Homeostasis in Mice. Gastroenterology (2011) 141:621–32. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.056

100. Andrews C, McLean MH, Durum SK. Cytokine Tuning of Intestinal Epithelial Function. Front Immunol (2018) 9:1270. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01270

101. Sorini C, Cosorich I, Lo CM, De Giorgi L, Facciotti F, Lucianò R, et al. Loss of Gut Barrier Integrity Triggers Activation of Islet-Reactive T Cells and Autoimmune Diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2019) 116:15140–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1814558116

102. Harkiolaki M, Holmes SL, Svendsen P, Gregersen JW, Jensen LT, McMahon R, et al. T Cell-Mediated Autoimmune Disease Due to Low-Affinity Crossreactivity to Common Microbial Peptides. Immunity (2009) 30:348–57. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.01.009

103. Firestein GS, McInnes IB. Immunopathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Immunity (2017) 46:183–96. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.02.006

104. Lundberg K, Kinloch A, Fisher BA, Wegner N, Wait R, Charles P, et al. Antibodies to Citrullinated α-Enolase Peptide 1 are Specific for Rheumatoid Arthritis and Cross-React With Bacterial Enolase. Arthritis Rheum (2008) 58:3009–19. doi: 10.1002/art.23936

105. Ruff WE, Dehner C, Kim WJ, Pagovich O, Aguiar CL, Yu AT, et al. And B Cells Cross-React With Mimotopes Expressed by a Common Human Gut Commensal to Trigger Autoimmunity. Cell Host Microbe (2019) 26:100–13.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.05.003

106. Miyauchi E, Kim SW, Suda W, Kawasumi M, Onawa S, Taguchi-Atarashi N, et al. Gut Microorganisms Act Together to Exacerbate Inflammation in Spinal Cords. Nature (2020) 585:102–6. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2634-9

107. Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Ando M, Kamada N, Nagano Y, Narushima S, et al. Th17 Cell Induction by Adhesion of Microbes to Intestinal Epithelial Cells. Cell (2015) 163:367–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.058

108. Goto Y, Panea C, Nakato G, Cebula A, Lee C, Diez MG, et al. Segmented Filamentous Bacteria Antigens Presented by Intestinal Dendritic Cells Drive Mucosal Th17 Cell Differentiation. Immunity (2014) 40:594–607. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.03.005

109. Lee YK, Menezes JS, Umesaki Y, Mazmanian SK. Proinflammatory T-cell Responses to Gut Microbiota Promote Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2011) 108:4615–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000082107

110. Edelblum KL, Sharon G, Singh G, Odenwald MA, Sailer A, Cao S, et al. The Microbiome Activates CD4 T-Cell–Mediated Immunity to Compensate for Increased Intestinal Permeability. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol (2017) 4:285–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.06.001

111. de Oliveira GLV, Leite AZ, Higuchi BS, Gonzaga MI, Mariano VS. Intestinal Dysbiosis and Probiotic Applications in Autoimmune Diseases. Immunology (2017) 152:1–12. doi: 10.1111/imm.12765

Keywords: epithelial barrier, leaky gut syndrome, microbiota, dysbiosis, gut immune system, autoimmune diseases

Citation: Kinashi Y and Hase K (2021) Partners in Leaky Gut Syndrome: Intestinal Dysbiosis and Autoimmunity. Front. Immunol. 12:673708. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.673708

Received: 28 February 2021; Accepted: 06 April 2021;

Published: 22 April 2021.

Edited by:

Stefan Jordan, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, GermanyReviewed by:

Kathryn A. Knoop, Mayo Clinic, United StatesChristian Neumann, Charité Medical University of Berlin, Germany

Copyright © 2021 Kinashi and Hase. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Koji Hase, aGFzZS1rakBwaGEua2Vpby5hYy5qcA==

Yusuke Kinashi

Yusuke Kinashi Koji Hase

Koji Hase