Abstract

Yellow mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) is a highly beneficial beetle that serves as an excellent source of edible protein as well as a practical study model. Therefore, studying its immune system is important. Like in other insects, the innate immune response effected through antimicrobial peptides production provides the most critical defense armory in T. molitor. Immune deficiency (Imd) signaling is one of the major pathways involved in the humoral innate immune response in this beetle. However, the nature of the molecules involved in the signaling cascade of the Imd pathway, from recognition to the production of final effectors, and their mechanism of action are yet to be elucidated in T. molitor model. In this review, we present a general overview of the current literature available on the Imd signaling pathway and its identified interaction partners in T. molitor.

Introduction

Insects are the most diverse group among all living organisms. They are considered to be ahead in the “evolutionary marathon” since the Devonian period owing to their ability to survive in diverse ecological habitats (1). The signature of distinct pathogenic infections from Gram-positive/-negative bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites along insect life cycle exert extreme evolutionary pressure that has resulted in the development of an enhanced immune system (2, 3). Unlike the mammalian hosts, insects do not have adaptive immune system to aid them in production of antibodies and various memory cells (4). In fact, the diversity and specificity of immune priming and most specifically transgenerational immune priming (TGIP) advocated to provide clues to the immunologic memory in few insects (4). Hence, they rely on innate immune responses to protect themselves against infections and maintain homeostasis, thereby adapting to their ecological niches (5, 6).

Innate immunity is highly conserved among all living organisms. Despite the fundamental differences between insects and mammals, their battle with common pathogens for millions of years has resulted in the development of similar immunity-related molecular machinery (4). This immunity is classified into cellular immunity, including phagocytosis, encapsulation, and nodulation (7, 8), and humoral immunity, which mediates clotting (9), melanin synthesis (10), and antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) production (11, 12). In insects, AMP production, the hallmark of innate immunity (13), is mainly mediated by two intracellular signaling pathways via nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) transcription factors: (i) Toll pathway, whose primary role was identified in dorso-ventral axis formation in Drosophila embryo (14), and in Gram-positive bacterial and fungal infection-related immune responses as identified by Hoffman et al. (15), and (ii) immune deficiency (Imd) pathway, which plays a role against Gram-negative bacterial infections (16).

IMD protein in insects shares similarity with receptor-interacting protein (RIP) of mammalian tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) (6, 17). The insect body is able to distinguish meso-diaminopimelic acid (DAP)-type peptidoglycans (PGNs) in the Gram-negative bacterial cell wall as non-self by the peptidoglycan-recognition proteins (PGRP), PGRP-LC and PGRP-LE (18, 19). The recognition of bacterial infection by PGRPs in Drosophila leads to the subsequent activation of the Imd pathway by recruiting the death domain-containing intracellular protein, Fas-associated protein with death domain (FADD), and caspase-8 homolog death-related ced-3/Nedd2-like (Dredd) protein. The downstream intracellular cascade transcription factor Relish is phosphorylated and translocated into the nucleus, where it binds to the transcription response elements of AMP genes (18, 20).

Among all the insects used to study immune responses and host-pathogen interactions, yellow mealworm, Tenebrio molitor, has become an attractive model owing to (i) its convenience and cost-effective breeding, (ii) relatively large body size benefiting researchers to collect sufficient hemolymph samples, (iii) identification of molecular nature of its immune response, and (iv) suitability for the development of potential strategies of pest control and management (4).

The Imd pathway in T. molitor is relatively well-established and extensively studied in the past decade, including some studies from our research group. In this review, we have highlighted the findings related to Imd signaling, mode of action of all the receptors, death domains, positive and negative regulators, and relative effectors in T. molitor. We also discuss numerous open-ended questions regarding PGRP-driven bacterial recognition, intracellular domain interaction with T. molitor inhibitor of NF-κB (IκB) kinase (IKK) complex, putative cross-talk of this signaling pathway with other immune pathways such as Toll and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and antimicrobial specificity of final effectors, which can only be addressed by further experiments.

A Brief History of Imd Signaling in Insects

The discovery of adaptor protein IMD in 1995 has opened new avenues related to innate immunity in invertebrates (21). Initially, this pathway was assumed to be solely involved in sensing Gram-negative bacteria. The regulation of Imd signaling pathway can be attributed to components that are conserved across the invertebrate species. These components include the pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) such as PGRP-LC and PGRP-LE, the IMD, transforming growth factor-activated Kinase 1 (TAK1), FADD, the caspase-8 homolog, Death-related ced-3/Nedd-2-like protein (DREDD), the inhibitor of κB kinase (IKK) complex, and the NF-κB transcription factor Relish (22). In insects such as flies, mosquitoes and beetles, the PRRs such as PGRP-LC and PGRP-LE, form complexes with DAP-type PGN of Gram-negative bacteria. Alternative splicing of PGRP-LC results in three PGRP-LC protein isoforms (-LCa, -LCx, and -LCy) (23, 24). While PGRP-LCx is required for polymeric DAP-type PGN recognition, both PGRP-LCa and PGRP-LCx are essential to detect monomeric DAP-type PGN. PGRP-LCa, a co-receptor for PGRP-LCx, binds to the monomeric PGN fragment called tracheal cytotoxin (TCT) (25–28). PGRP-LE elicits both extra- and intracellular functions. A short form of PGRP-LE, mediates its expression on the cell surface, binds to PGN and modulates Imd signaling. In contrast, the full-length PGRP-LE is expressed in the cytoplasm, where it recognizes TCT fragments independently from PGRP-LC by directly interacting with IMD protein (29). Following recognition, the PGRPs form homo- and heterodimers, resulting in the recruitment of IMD (16). The intracellular cascade is then activated by the interaction of IMD with FADD and sequential activation of DREDD, TAK1, TAK binding protein 2 and 3 (TAB2/3), and the IKK complex (11). Subsequently, Relish is phosphorylated at multiple N-terminal sites by the IKK complex and thereafter cleaved by DREDD (30, 31). While the N-terminal transcription factor domain is released by endoproteolytic cleavage, the C-terminal part (Rel-49) remains in the cytoplasm and the active N-terminal part (Rel-68) is translocated into the nucleus, leading to the activation of antimicrobial response, elicited by the production of AMPs (32, 33). Further, IMD signaling is supplemented by TAB2, E3 ligase inhibitor of apoptosis 2 (IAP2), which associates with the E2-ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes UEV1a, Bendless (Ubc13), and Effete (Ubc5) and the transcription cofactor Akirin (22, 34).

Additional interactions of the Imd pathway with other immune signaling pathways have been reported in different insects. Evolutionary dynamics lead to various host-pathogen interactions. Therefore, insects of different orders, for instance, fruit flies, mosquitoes, and honey bees, express various immune-related genes during their interaction with pathogens. Following viral and parasitoid infections in Drosophila, unpaired (upd) 1, upd2, and upd3 in hemocytes bind to the dimerized Domeless receptor and activate Jak kinase (Hopscotch), resulting in phosphorylation and dimerization of STATs (Start92E) (35). Although honey bees lack upd orthologs, they can recognize viral infections via the same pathway and regulate relevant antimicrobial effectors such as Thioester-containing protein (TEPs) (36). Imd signaling engages with transcriptional factors after recognizing viral PAMPs. The viral patterns have been shown to stimulate REL2-regulated genes. Moreover, an specific binding sites for D. melanogaster NF-κB transcription factors and REL1A of Aedes aegypti have been found in TEP22 protein (37). Additionally, TAK1 and TAB2/3 activate the JNK pathway, leading to either the expression of AMP genes or apoptosis (36). Furthermore, phospholipase A2 (PLA2) has been identified and characterized in a wide range of animals and has diverse functions, including but not limited to host immune response. The induction of PLA2 activity in Spodoptera exigua is controlled by Imd signaling (38).

Imd signaling can be triggered by Gram-negative bacteria and other pathogenic sources, including fungal infections (39). Reduced survivability in Relish mutants of D. melanogaster and induced NF-κB REL2 in fat bodies and midgut of mosquitoes with fungal infection have been reported previously (40).

Negative regulators of Imd signaling have also been studied and identified. A membrane-bound non-catalytic PGRP-LF functions as a negative regulator of the PGRP-LC-mediated Imd pathway in D. melanogaster (41). Hence, some catalytic PGRPs like PGRP-SC1 and PGRP-LB are reported as negative regulator of Imd signaling via amidase activity against PGN (42). Moreover, in mosquitoes and honey bees, poor Imd response upon knock-in (Pirk), Rudra, and PGRP-LC-interacting inhibitor of Imd signaling (PIMS) are the other negative regulators of the pathway (35, 36). PIMS depletes the level of PGRP-LC from the plasma membrane and abrogates Imd signaling, maintaining a balanced Imd response subsequent to bacterial infections (43). The negative regulation has also been attributed to the enzyme transglutaminase that mediates cross-linking of Relish and suppresses innate immunity to commensal bacteria in the gut of Drosophila (44).

Summary of Previous Reports on Imd Signaling in T. molitor

Despite the application of Drosophila as a powerful study model, using larger insects such as T. molitor has been benefiting researchers with more accessible biochemical investigations. As in other insects, the Imd pathway in T. molitor initiates an immune response by sensing invaders through PRRs such as PGRP-LC or PGRP-LE (45). Downstream of the intracellular signaling cascade, Relish enhances the production of AMPs to eliminate pathogens (46). Imd pathway components in T. molitor such as PGRP-LE, IMD protein, FADD, Dredd, TAK1, IKK gamma, IKK epsilon, and Relish have already been identified by our research group. Functional roles of these components have been examined using numerous pathogens, including but not limited to Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Candida albicans, and Listeria monocytogenes, as immune elicitors. Knocking down Imd pathway components using RNA interference (RNAi) technology has shed light on various aspects, such as post-infection mortality rates and reduction in AMP levels (Table 1).

Table 1

| Genes | Known Functions | Pathogens | Associated Organs | Regulated AMPs | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TmPGRP-LE | Recognition receptor | E. coli | Gut |

TmTene-1 TmTene-4 TmCole-A TmCole-C TmDef TmCec-2 TmAtta-1b TmAtt-2 |

(45) |

| TmIMD | Adapter molecule in Imd pathway | E. coli | Whole body |

TmTene-1 TmTene-2 TmTene-4 TmDef-like TmCole-A TmCole-C TmAtta-1a TmAtta-1b TmAtta-2 |

(47) |

| TmIKKγ | Regulatory molecule - inhibitor of nuclear factor-κB (IκB) kinase (IKK) complex |

E. coli

S. aureus C. albicans |

Fat bodies Hemocytes Gut |

TmTene-1 TmTene-2 TmTene-4 TmDef TmDef-like TmCole-A TmCole-C TmAtta-1a TmAtta-1b TmAtta-2 |

(48) |

| TmIKKϵ | Regulatory molecule - inhibitor of nuclear factor-κB (IκB) kinase (IKK) complex | E. coli | Fat bodies |

TmTene-1 TmTene-2 TmTene-4 TmDef TmDef-like TmCole-A TmCole-C TmCec-2 TmAtta-1a TmAtta-1b TmAtta-2 |

(49) |

| TmRel | Transcription factor (NF-κB) | E. coli | Fat bodies Hemocytes Gut |

TmTene-1 TmTene-2 TmTene-4 TmDef TmDef-like TmCole-A TmCole-C TmAtta-1a TmAtta-1b TmAtta-2 |

(46) |

Summary of the Imd pathway compartments that regulate antimicrobial peptide production in T. molitor.

The expression of nine AMP genes (Tenecin1, Tenecin4, Attacin1a, Attacin1b, Attacin2, ColeoptericinA, ColeoptericinC, Defensin, and Defensin-like) in the insect gut reduced in response to E. coli infection post-PGRP-LE knockdown (45). Moreover, T. molitor larvae demonstrate an increased mortality rate post L. monocytogenes infection following PGRP-LE silencing. However, another study presented conflicting results under similar experimental conditions in a different T. molitor larval stage (50).

Silencing of TmImd increases mortality after E. coli and C. albicans infections owing to the reduced expression of nine AMP genes (Tenecin1, Tenecin2, Tenecin4, Defensin-like, ColeoptericinA, ColeoptericinC, Attacin1a, Attacin1b, and Attacin2) and five AMP genes (Tenecin2, Defensin-like, ColeoptericinA, Attacin1a, and Attacin2), respectively (47).

Likewise, IKK epsilon-silenced T. molitor larvae showed enhanced susceptibility post-E. coli infection owing to reduced expression of 12 AMP genes (Tenecin1, Tenecin2, Tenecin4, Defensin, Defensin-like, ColeoptericinA, ColeoptericinC, Attacin1a, Attacin1b, Attacin2, Thaumatin-like protein1, and Thaumatin-like protein2) in fat bodies, which are the major immune organ in insects. Reduced expression of 10 AMP genes (Tenecin1, Tenecin4, Defensin, ColeoptericinA, ColeoptericinC, Cecropin-2, Attacin1b, Attacin2, Thaumatin-like protein1, and Thaumatin-like protein2) in the gut and four AMP genes (Defensin, Defensin-like, ColeoptericinC, and Attacin2) in the hemocytes following IKK-epsilon knockdown elevated the risk of E. coli infection-mediated mortality (49). In addition, silencing the IKK gamma gene enhanced the susceptibility of T. molitor larvae to E. coli, S. aureus, and C. albicans infections (48). The understanding of the T. molitor Imd signaling cascade under pathogenic stress is still under examination. Understanding the complexity and intricate cross-talk mechanisms in response to varied pathogens would provide interesting insights of the defense mechanisms in the beetle innate immunity.

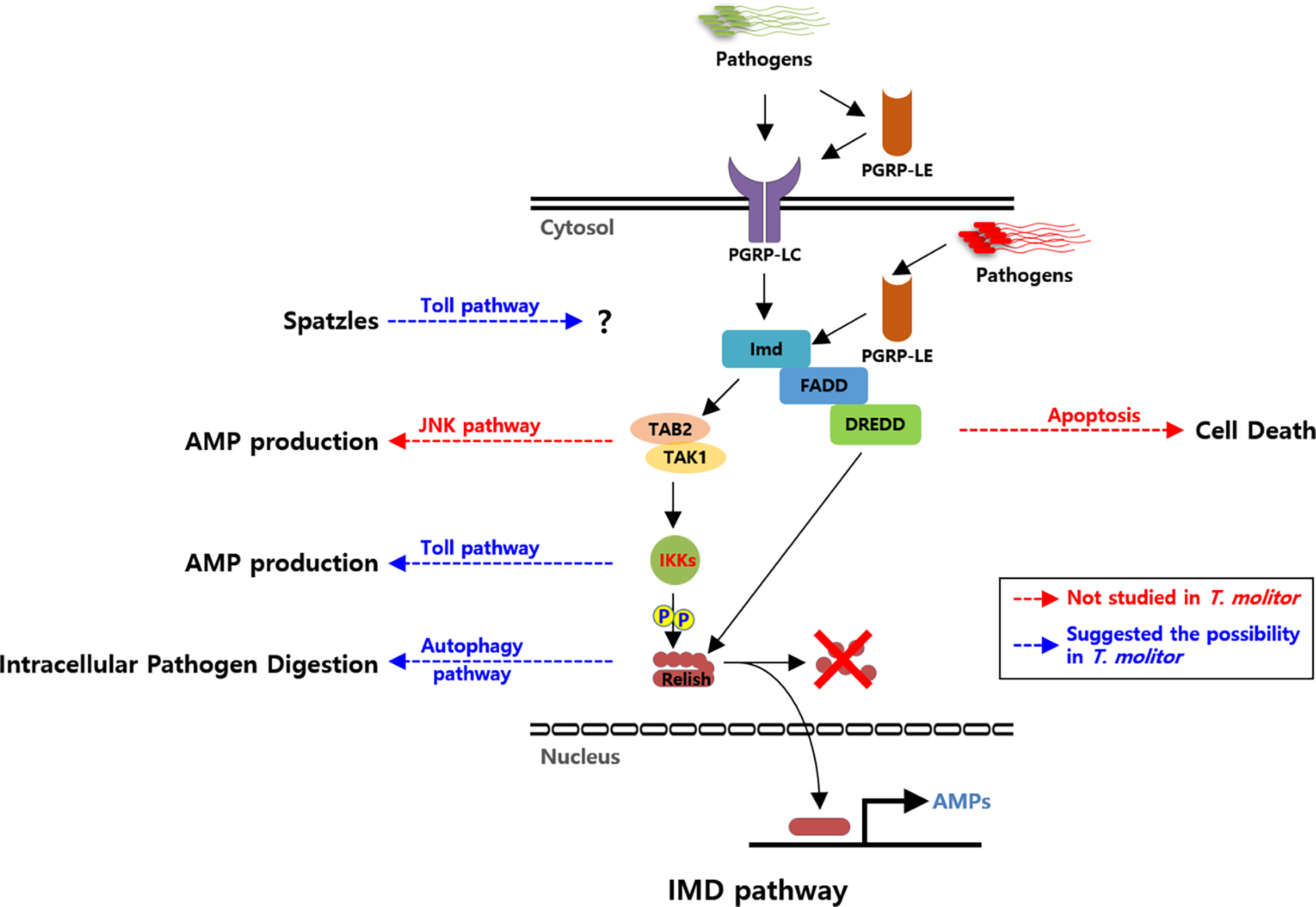

Further investigations on the downstream molecules in the Imd pathway and transcription factor Relish have proven the role of Imd signaling in bacterial (Gram-negative and Gram-positive) and fungal infections. For instance, in dsTmRelish-treated larvae, mortality of almost 90% was attributed to the downregulation of AMPs such as Tenecin3, Tenecin4, ColeoptericinA, and Attacin1a in all tissues. Hence, direct interaction of Relish and production of AMPs against E. coli infection in T. molitor support the role of Imd signaling in the host-mediated immune response (46). Additionally, Relish plays a critical role in inducing autophagy-related genes against L. monocytogenes infection in the fat bodies and hemocytes of T. molitor (51) (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Schematic illustration of the proposed Imd pathway in Tenebrio molitor and its possible cross-talks. Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs; PGRP-LC and PGRP-LE) are triggered by DAP-type PGN of the bacterial cell wall. Recognition of Gram-negative bacteria further triggers the recruitment of intracellular proteins TmIMD, TmFADD, and TmDREDD. TmTAK1/TmTAB2, activated by TmIMD, further activates TmIKK complex. TmRelish is subsequently phosphorylated by the TmIKK complex and then cleaved by TmDredd. Eventually, it leads to the translocation of TmRelish into the nucleus, where it binds to the relevant transcription response elements and triggers AMP production. Solid black arrows indicate the identified interactions between Imd signaling compartments. Blue dashed arrows indicate putative cross-talks between Imd and other signaling pathways via TmIKKs complex, TmRelish, and ligand Spaetzle in T. molitor. Red dashed arrows indicate the putative cross-talks identified in other insects. Abbreviations: PGRP; Peptidoglycan recognition protein, IMD; Immune deficiency, FADD; Fas-associated protein with death domain, DREDD; death-related ced-3/Nedd2-like protein, TAK1; Transforming growth factor-activated kinase1, TAB2; TAK binding protein 2, IKK; Inhibitor of nuclear factor-κB (IκB) kinase, AMP; Antimicrobial peptide, JNK; c-Jun N-terminal kinase.

Cross-Regulation of Imd and Toll Pathways in T. molitor

Cross-regulation of Imd and Toll pathways have been previously documented in various insects, such as Drosophila, Tribolium castaneum, and Plautia stali (20). Studies on T. molitor also provided evidence for the cross-regulation of Imd and Toll pathways (Figure 1). Generally, insects elicit distinct immune responses depending on the pathogen source. For instance, Toll signaling in Drosophila can be activated solely after recognizing lysine-type PGN of Gram-positive bacteria or fungal beta-1,3-glucan (52). In contrast, the Imd pathway is activated simply by recognizing DAP-type PGN of Gram-negative bacteria or certain Gram-positive bacilli (53). However, in T. molitor, polymeric DAP-type PGN of Gram-negative bacteria can trigger both Imd and Toll pathways (54). The studies that have proposed the intracellular cross-regulation between these two signaling pathways are listed in Table 2.

Table 2

| Genes | Signaling pathway | Pathogens | Associated Organs | Effects on the other immune pathway | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TmPGRP-LE | Autophagy | L. monocytogenes | Whole body | decreased larval survivability | (50) |

| TmIKKγ | Toll |

E. coli

S. aureus C. albicans |

Fat bodies Hemocytes Gut |

Positive regulation of TmDorX2 | (48) |

| TmIKKϵ | Toll | E. coli | Fat bodies Gut |

Positive regulation of TmDorX2 | (49) |

| TmRel | Autophagy | L. monocytogenes | Fat bodies | Positive regulation of TmAtg1 and TmVps34 | (51) |

| Gut | Positive regulation of TmVps34, TmAtg9, TmAtg5, and TmAtg8 |

Potential evidence for the interactions between Imd pathway and other immune signaling pathways in T. molitor.

Knockdown of IKK gamma causes decreased survivability after E. coli, S. aureus, and C. albicans infections. IKK gamma silencing resulted in the downregulation of Transcription factors Relish and DorX2-encoding genes downstream of Imd and Toll pathways, respectively. Consequently, the gene expression of ten relevant AMPs was also suppressed. Concurrently, DorX1 expression was upregulated, suggesting that IKK gamma can act as a positive and negative regulator of Toll and Imd signaling pathways (48). Furthermore, IKK epsilon, another unit of the IKK complex, was involved in the expression of three NF-κBs (DorX1, DorX2, and Relish) and AMPs in fat body tissues. These results suggest that IKK epsilon plays a pivotal role in regulating Toll and Imd pathways in the fat body tissues of T. molitor. Nevertheless, the survivability of larvae was not affected by the invasion of S. aureus and C. albicans post-IKK epsilon knockdown, whereas they showed susceptibility after E. coli infection (49).

Additionally, lysine-type PGN of Gram-positive bacteria in Drosophila can be sensed by PGRP-SA and Gram-negative binding protein 1 (GNBP-1) (15). In contrast, various studies have clarified that PGRP-SA of Bombus ignitus, Apis mellifera, and Megachile rotundata tended to bind to DAP-type PGN rather than lysine-type PGN (55). In T. molitor, PGRP-SA plays an important role in survivability against bacterial (Gram-negative and Gram-positive) and fungal infections (56). Furthermore, Toll receptor can be activated by its ligand, Spaetzle (Spz). This protein is a zymogen and is cleaved to its mature form by a chain of serine protease activation, following pathogen recognition by PRRs (24, 57). The immunological roles of Spz isoforms (Spz1b, Spz-like, Spz4, Spz5, and Spz6) in T. molitor have been investigated using RNAi (58–62). Among them, TmSpz1b, TmSpz-like, and TmSpz5 showed anti-Gram-negative bacterial (E. coli) activity (58, 61, 62). Moreover, silencing of TmSpz1b downregulated the expression of TmDorX1 and TmRel in the immune organs (58). Similarly, TmSpz-like knockdown suppressed the expression of all NF-κB genes (61). The TmSpz5-silenced larvae, however, showed a decreased expression of TmRel after Gram-negative bacterial infection but an increased expression of the same after a Gram-positive bacterial infection in the Malpighian tubules (62). Collectively, the activation of either Toll or Imd signaling pathways interferes with the other through unknown interactions between their components (Table 3).

Table 3

| Genes | Pathogens | Activating Organs | Effects on Imd pathway | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TmPGRP-SA | E. coli | Fat bodies Gut |

Positive regulation of TmRelish | (56) |

| TmSpz1b | E. coli | Fat bodies Hemocytes |

Positive regulation of TmRelish | (58) |

| TmSpz-like | E. coli | Whole body | Positive regulation of TmRelish | (61) |

| TmSpz5 | E. coli | Malpighian tubules | Positive regulation of TmRelish | (62) |

| S. aureus | Malpighian tubules | Negative regulation of TmRelish |

Summary of Toll pathway compartments affecting the regulation of Imd signaling in T. molitor.

Another pathway that supposedly interacts with Imd signaling is autophagy, a conserved cellular mechanism that maintains homeostasis by eliminating dysfunctional cellular components and intracellular pathogens mediating its delivery to the lysosomes (63, 64). PGRP-LE recognizes the intracellular pathogen Listeria and induces autophagy (64). Furthermore, the transcription factor Relish can regulate the expression of autophagy-related genes in T. molitor through unknown mechanisms. This was briefly addressed in a study wherein silencing of TmRelish in T. molitor larvae decreased the mRNA levels of TmAtg1 in the fat bodies and hemocytes subsequent to Listeria infection (47). This proposes a cross-talk between Listeria-induced autophagy and Imd pathway in T. molitor (63).

Final Remarks

We have provided a comprehensive overview of the Imd signaling cascade in T. molitor and insights into future research directions that would improve understanding of this signaling cascade in beetles. The existing genome sequencing information have identified players associated with the Imd signaling cascade; however, several aspects remain unanswered. These include (i) the precise mechanism of the Imd pathway compartments such as FADD, Dredd, TAK1, and TAB2, (ii) cross-talks with other signaling pathways, such as Toll, JNK, and autophagy, and (iii) the putative functions of this signaling in development and apoptosis, similar to its counterpart, TNFR signaling, in mammals. Therefore, further studies are essential to bridge these gaps in the literature.

Funding

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and future Planning (Grant No. 2019R1I1A3A01057848) and Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture and Forestry (IPET) through Agricultural Machinery/Equipment Localization Technology Development Program, funded by Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (MAFRA) (no.321055-05).

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Author contributions

YH and YJ: design manuscript concepts. MA and HJ: wrote the draft manuscript. MA, HJ, and YJ: wrote the manuscript. BP, YH, and YJ: revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1

Kawahara R Chernykh A Alagesan K Bern M Cao W Chalkley RJ et al . Community Evaluation of Glycoproteomics Informatics Solutions Reveals High-Performance Search Strategies for Serum Glycopeptide Analysis. Nat Methods (2021) 18(11):1304–16. doi: 10.1038/s41592-021-01309-x

2

Ferrandon D Imler JL Hoffmann JA . Sensing Infection in Drosophila: Toll and Beyond. Semin Immunol (2004) 16(1):43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2003.10.008

3

Kojour MAM Han YS Jo YH . An Overview of Insect Innate Immunity. Entomol Res (2020) 50(6):282–91. doi: 10.1111/1748-5967.12437

4

Ali Mohammadie Kojour M Baliarsingh S Jang HA Yun K Park KB Lee JE et al . Current Knowledge of Immune Priming in Invertebrates, Emphasizing Studies on Tenebrio Molitor. Dev Comp Immunol (2022) 127:104284. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2021.104284

5

Medzhitov R Janeway C Jr . Innate Immunity. N Engl J Med (2000) 343(5):338–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008033430506

6

Sheehan G Garvey A Croke M Kavanagh K . Innate Humoral Immune Defences in Mammals and Insects: The Same, With Differences? Virulence (2018) 9(1):1625–39. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2018.1526531

7

Karp RD . Inducible Humoral Immunity in Insects: Does an Antibody-Like Response Exist in Invertebrates? Res Immunol (1990) 141(9):932–4. doi: 10.1016/0923-2494(90)90196-6

8

Rizki TM Rizki RM . The Cellular Defense System of Drosophila Melanogaster. Insect Ultrastructure: Springer; (1984) p:579–604. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-2715-8_16

9

Hoffmann JA . Innate Immunity of Insects. Curr Opin Immunol (1995) 7(1):4–10. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80022-0

10

Cerenius L Lee BL Soderhall K . The proPO-System: Pros and Cons for its Role in Invertebrate Immunity. Trends Immunol (2008) 29(6):263–71. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.02.009

11

Lemaitre B Hoffmann J . The Host Defense of Drosophila Melanogaster. Annu Rev Immunol (2007) 25:697–743. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141615

12

Merrifield RB Vizioli LD Boman HG . Synthesis of the Antibacterial Peptide Cecropin A (1-33). Biochemistry (1982) 21(20):5020–31. doi: 10.1021/bi00263a028

13

Hetru C Hoffmann JA . NF-kappaB in the Immune Response of Drosophila. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol (2009) 1(6):a000232. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000232

14

Belvin MP Anderson KV . A Conserved Signaling Pathway: The Drosophila Toll-Dorsal Pathway. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol (1996) 12:393–416. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.393

15

Gobert V Gottar M Matskevich AA Rutschmann S Royet J Belvin M et al . Dual Activation of the Drosophila Toll Pathway by Two Pattern Recognition Receptors. Science (2003) 302(5653):2126–30. doi: 10.1126/science.1085432

16

Georgel P Naitza S Kappler C Ferrandon D Zachary D Swimmer C et al . Drosophila Immune Deficiency (IMD) is a Death Domain Protein That Activates Antibacterial Defense and can Promote Apoptosis. Dev Cell (2001) 1(4):503–14. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(01)00059-4

17

Kleino A Silverman N . The Drosophila IMD Pathway in the Activation of the Humoral Immune Response. Dev Comp Immunol (2014) 42(1):25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2013.05.014

18

Fukuyama H Verdier Y Guan Y Makino-Okamura C Shilova V Liu X et al . Landscape of Protein-Protein Interactions in Drosophila Immune Deficiency Signaling During Bacterial Challenge. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2013) 110(26):10717–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304380110

19

Bischoff V Vignal C Duvic B Boneca IG Hoffmann JA Royet J . Downregulation of the Drosophila Immune Response by Peptidoglycan-Recognition Proteins SC1 and SC2. PLoS Pathog (2006) 2(2):e14. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020014

20

Nishide Y Kageyama D Yokoi K Jouraku A Tanaka H Futahashi R et al . Functional Crosstalk Across IMD and Toll Pathways: Insight Into the Evolution of Incomplete Immune Cascades. Proc Biol Sci (2019) 286(1897):20182207. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2018.2207

21

Lemaitre B Kromer-Metzger E Michaut L Nicolas E Meister M Georgel P et al . A Recessive Mutation, Immune Deficiency (Imd), Defines Two Distinct Control Pathways in the Drosophila Host Defense. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1995) 92(21):9465–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9465

22

Zhang W Tettamanti G Bassal T Heryanto C Eleftherianos I Mohamed A . Regulators and Signalling in Insect Antimicrobial Innate Immunity: Functional Molecules and Cellular Pathways. Cell Signal (2021) 83:110003. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2021.110003

23

Werner T Liu G Kang D Ekengren S Steiner H Hultmark D . A Family of Peptidoglycan Recognition Proteins in the Fruit Fly Drosophila Melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2000) 97(25):13772–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.25.13772

24

Werner T Borge-Renberg K Mellroth P Steiner H Hultmark D . Functional Diversity of the Drosophila PGRP-LC Gene Cluster in the Response to Lipopolysaccharide and Peptidoglycan. J Biol Chem (2003) 278(29):26319–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300184200

25

Chang CI Chelliah Y Borek D Mengin-Lecreulx D Deisenhofer J . Structure of Tracheal Cytotoxin in Complex With a Heterodimeric Pattern-Recognition Receptor. Science (2006) 311(5768):1761–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1123056

26

Chang CI Ihara K Chelliah Y Mengin-Lecreulx D Wakatsuki S Deisenhofer J . Structure of the Ectodomain of Drosophila Peptidoglycan-Recognition Protein LCa Suggests a Molecular Mechanism for Pattern Recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2005) 102(29):10279–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504547102

27

Kaneko T Goldman WE Mellroth P Steiner H Fukase K Kusumoto S et al . Monomeric and Polymeric Gram-Negative Peptidoglycan But Not Purified LPS Stimulate the Drosophila IMD Pathway. Immunity (2004) 20(5):637–49. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(04)00104-9

28

Mellroth P Karlsson J Hakansson J Schultz N Goldman WE Steiner H . Ligand-Induced Dimerization of Drosophila Peptidoglycan Recognition Proteins In Vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2005) 102(18):6455–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407559102

29

Kaneko T Yano T Aggarwal K Lim JH Ueda K Oshima Y et al . PGRP-LC and PGRP-LE Have Essential Yet Distinct Functions in the Drosophila Immune Response to Monomeric DAP-Type Peptidoglycan. Nat Immunol (2006) 7(7):715–23. doi: 10.1038/ni1356

30

Silverman N Zhou R Stoven S Pandey N Hultmark D Maniatis TA . Drosophila IkappaB Kinase Complex Required for Relish Cleavage and Antibacterial Immunity. Genes Dev (2000) 14(19):2461–71. doi: 10.1101/gad.817800

31

Stoven S Silverman N Junell A Hedengren-Olcott M Erturk D Engstrom Y et al . Caspase-Mediated Processing of the Drosophila NF-kappaB Factor Relish. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2003) 100(10):5991–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1035902100

32

Erturk-Hasdemir D Broemer M Leulier F Lane WS Paquette N Hwang D et al . Two Roles for the Drosophila IKK Complex in the Activation of Relish and the Induction of Antimicrobial Peptide Genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2009) 106(24):9779–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812022106

33

Stoven S Ando I Kadalayil L Engstrom Y Hultmark D . Activation of the Drosophila NF-kappaB Factor Relish by Rapid Endoproteolytic Cleavage. EMBO Rep (2000) 1(4):347–52. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd072

34

Myllymaki H Valanne S Ramet M . The Drosophila Imd Signaling Pathway. J Immunol (2014) 192(8):3455–62. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303309

35

Gilbert LI . Insect Molecular Biology and Biochemistry. San Diego, USA: Academic Press (2012).

36

McMenamin AJ Daughenbaugh KF Parekh F Pizzorno MC Flenniken ML . Honey Bee and Bumble Bee Antiviral Defense. Viruses (2018) 10(8):395. doi: 10.3390/v10080395

37

Russell TA Ayaz A Davidson AD Fernandez-Sesma A Maringer K . Imd Pathway-Specific Immune Assays Reveal NF-kappaB Stimulation by Viral RNA PAMPs in Aedes Aegypti Aag2 Cells. PLoS Negl Trop Dis (2021) 15(2):e0008524. doi: 10.1101/2020.06.30.179879

38

Sajjadian SM Vatanparast M Kim Y . Toll/IMD Signal Pathways Mediate Cellular Immune Responses via Induction of Intracellular PLA 2 Expression. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol (2019) 101(3):e21559. doi: 10.1002/arch.21559

39

Hedengren M Asling B Dushay MS Ando I Ekengren S Wihlborg M et al . Relish, a Central Factor in the Control of Humoral But Not Cellular Immunity in Drosophila. Mol Cell (1999) 4(5):827–37. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80392-5

40

Ramirez JL Muturi EJ Barletta ABF Rooney AP . The Aedes Aegypti IMD Pathway is a Critical Component of the Mosquito Antifungal Immune Response. Dev Comp Immunol (2019) 95:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2018.12.010

41

Maillet F Bischoff V Vignal C Hoffmann J Royet J . The Drosophila Peptidoglycan Recognition Protein PGRP-LF Blocks PGRP-LC and IMD/JNK Pathway Activation. Cell Host Microbe (2008) 3(5):293–303. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.04.002

42

Zaidman-Remy A Herve M Poidevin M Pili-Floury S Kim MS Blanot D et al . The Drosophila Amidase PGRP-LB Modulates the Immune Response to Bacterial Infection. Immunity (2006) 24(4):463–73. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.02.012

43

Lhocine N Ribeiro PS Buchon N Wepf A Wilson R Tenev T et al . PIMS Modulates Immune Tolerance by Negatively Regulating Drosophila Innate Immune Signaling. Cell Host Microbe (2008) 4(2):147–58. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.07.004

44

Shibata T Sekihara S Fujikawa T Miyaji R Maki K Ishihara T et al . Transglutaminase-Catalyzed Protein-Protein Cross-Linking Suppresses the Activity of the NF-κb-Like Transcription Factor Relish. Sci Signaling (2013) 6(285):ra61. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003970

45

Keshavarz M Jo YH Edosa TT Han YS . Tenebrio Molitor PGRP-LE Plays a Critical Role in Gut Antimicrobial Peptide Production in Response to Escherichia Coli. Front Physiol (2020) 11:320. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.00320

46

Keshavarz M Jo YH Patnaik BB Park KB Ko HJ Kim CE et al . TmRelish is Required for Regulating the Antimicrobial Responses to Escherichia Coli and Staphylococcus Aureus in Tenebrio Molitor. Sci Rep (2020) 10(1):4258. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-61157-1

47

Jo YH Patnaik BB Hwang J Park KB Ko HJ Kim CE et al . Regulation of the Expression of Nine Antimicrobial Peptide Genes by TmIMD Confers Resistance Against Gram-Negative Bacteria. Sci Rep (2019) 9(1):10138. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46222-8

48

Ko HJ Jo YH Patnaik BB Park KB Kim CE Keshavarz M et al . IKKgamma/NEMO Is Required to Confer Antimicrobial Innate Immune Responses in the Yellow Mealworm, Tenebrio Molitor. Int J Mol Sci (2020) 21(18):6734. doi: 10.3390/ijms21186734

49

Ko HJ Patnaik BB Park KB Kim CE Baliarsingh S Jang HA et al . TmIKKepsilon Is Required to Confer Protection Against Gram-Negative Bacteria, E. Coli by the Regulation of Antimicrobial Peptide Production in the Tenebrio Molitor Fat Body. Front Physiol (2021) 12:758862. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.758862

50

Tindwa H Patnaik BB Kim DH Mun S Jo YH Lee BL et al . Cloning, Characterization and Effect of TmPGRP-LE Gene Silencing on Survival of Tenebrio Molitor Against Listeria Monocytogenes Infection. Int J Mol Sci (2013) 14(11):22462–82. doi: 10.3390/ijms141122462

51

Keshavarz M Jo YH Edosa TT Han YS . Two Roles for the Tenebrio Molitor Relish in the Regulation of Antimicrobial Peptides and Autophagy-Related Genes in Response to Listeria Monocytogenes. Insects (2020) 11(3):188. doi: 10.3390/insects11030188

52

Lemaitre B Nicolas E Michaut L Reichhart JM Hoffmann JA . The Dorsoventral Regulatory Gene Cassette Spatzle/Toll/cactus Controls the Potent Antifungal Response in Drosophila Adults. Cell (1996) 86(6):973–83. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80172-5

53

Zhai Z Huang X Yin Y . Beyond Immunity: The Imd Pathway as a Coordinator of Host Defense, Organismal Physiology and Behavior. Dev Comp Immunol (2018) 83:51–9. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2017.11.008

54

Yu Y Park JW Kwon HM Hwang HO Jang IH Masuda A et al . Diversity of Innate Immune Recognition Mechanism for Bacterial Polymeric Meso-Diaminopimelic Acid-Type Peptidoglycan in Insects. J Biol Chem (2010) 285(43):32937–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.144014

55

Liu Y Zhao X Huang J Chen M An J . Structural Insights Into the Preferential Binding of PGRP-SAs From Bumblebees and Honeybees to Dap-Type Peptidoglycans Rather Than Lys-Type Peptidoglycans. J Immunol (2019) 202(1):249–59. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800439

56

Keshavarz M Jo YH Edosa TT Bae YM Han YS . TmPGRP-SA Regulates Antimicrobial Response to Bacteria and Fungi in the Fat Body and Gut of Tenebrio Molitor. Int J Mol Sci (2020) 21(6):2113. doi: 10.3390/ijms21062113

57

Weber AN Tauszig-Delamasure S Hoffmann JA Lelievre E Gascan H Ray KP et al . Binding of the Drosophila Cytokine Spatzle to Toll is Direct and Establishes Signaling. Nat Immunol (2003) 4(8):794–800. doi: 10.1038/ni955

58

Bae YM Jo YH Patnaik BB Kim BB Park KB Edosa TT et al . Tenebrio Molitor Spatzle 1b Is Required to Confer Antibacterial Defense Against Gram-Negative Bacteria by Regulation of Antimicrobial Peptides. Front Physiol (2021) 12:758859. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.758859

59

Edosa TT Jo YH Keshavarz M Bae YM Kim DH Lee YS et al . TmSpz4 Plays an Important Role in Regulating the Production of Antimicrobial Peptides in Response to Escherichia Coli and Candida Albicans Infections. Int J Mol Sci (2020) 21(5):1878. doi: 10.3390/ijms21051878

60

Edosa TT Jo YH Keshavarz M Bae YM Kim DH Lee YS et al . TmSpz6 Is Essential for Regulating the Immune Response to Escherichia Coli and Staphylococcus Aureus Infection in Tenebrio Molitor. Insects (2020) 11(2):105. doi: 10.3390/insects11020105

61

Jang HA Patnaik BB Ali Mohammadie Kojour M Kim BB Bae YM Park KB et al . TmSpz-Like Plays a Fundamental Role in Response to E. Coli But Not S. Aureus or C. Albican Infection in Tenebrio Molitor via Regulation of Antimicrobial Peptide Production. Int J Mol Sci (2021) 22(19):10888. doi: 10.3390/ijms221910888

62

Ali Mohammadie Kojour M Edosa TT Jang HA Keshavarz M Jo YH Han YS . Critical Roles of Spatzle5 in Antimicrobial Peptide Production Against Escherichia Coli in Tenebrio Molitor Malpighian Tubules. Front Immunol (2021) 12:760475. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.760475

63

Jo YH Lee JH Patnaik BB Keshavarz M Lee YS Han YS . Autophagy in Tenebrio Molitor Immunity: Conserved Antimicrobial Functions in Insect Defenses. Front Immunol (2021) 12:667664. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.667664

64

Yano T Mita S Ohmori H Oshima Y Fujimoto Y Ueda R et al . Autophagic Control of Listeria Through Intracellular Innate Immune Recognition in Drosophila. Nat Immunol (2008) 9(8):908–16. doi: 10.1038/ni.1634

Summary

Keywords

Tenebrio molitor , Imd pathway, innate immunity, antimicrobial peptides, cross-regulation

Citation

Jang HA, Kojour MAM, Patnaik BB, Han YS and Jo YH (2022) Current Status of Immune Deficiency Pathway in Tenebrio molitor Innate Immunity. Front. Immunol. 13:906192. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.906192

Received

28 March 2022

Accepted

16 June 2022

Published

04 July 2022

Volume

13 - 2022

Edited by

Erjun Ling, Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences (CAS), China

Reviewed by

Amr A. Mohamed, Cairo University, Egypt; Yonggyun Kim, Andong National University, South Korea

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Jang, Kojour, Patnaik, Han and Jo.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yong Hun Jo, yhun1228@jnu.ac.kr

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

This article was submitted to Comparative Immunology, a section of the journal Frontiers in Immunology

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.