Abstract

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic recurrent gastrointestinal disease that seriously affects the quality of life of patients around the world. It is characterized by recurrent abdominal pain, diarrhea, and mucous bloody stools. There is an urgent need for more accurate diagnosis and effective treatment of IBD. Accumulated evidence suggests that gut microbiota plays an important role in the occurrence and development of gut inflammation. However, most studies on the role of gut microbiota in IBD have focused on bacteria, while fungal microorganisms have been neglected. Fungal dysbiosis can activate the host protective immune pathway related to the integrity of the epithelial barrier and release a variety of pro-inflammatory cytokines to trigger the inflammatory response. Dectin-1, CARD9, and IL-17 signaling pathways may be immune drivers of fungal dysbacteriosis in the development of IBD. In addition, fungal-bacterial interactions and fungal-derived metabolites also play an important role. Based on this information, we explored new strategies for IBD treatment targeting the intestinal fungal group and its metabolites, such as fungal probiotics, antifungal drugs, diet therapy, and fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). This review aims to summarize the fungal dysbiosis and pathogenesis of IBD, and provide new insights and directions for further research in this emerging field.

1 Introduction

Intestinal microbiota, including bacteria, fungi, and viruses, represent a complex microbial ecosystem (1) and are an important part of human health. Although the fungi account for only about 0.1% of the intestinal microbial community (2), they play a decisive role in the dynamic balance of intestinal microbial composition and mucosal immune response, and have a disproportionate significance in the intestinal ecosystem (3). The abnormal changes of intestinal fungi are closely related to human digestive system diseases. In this review, we identify significant changes in intestinal microecology associated with common diseases and explore the association between fungi and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) through basic and clinical research conducted by multiple research teams (4).

A number of studies (5–9) have shown that intestinal fungi can trigger inflammation by regulating the host's immune response, potentially increasing the host's susceptibility to various diseases and exacerbating IBD. It is worth noting that the abundance of fungi in the intestine is much lower than that of bacteria, and the instability of fungal structures makes it difficult to fully describe the composition of normal fungi (7). While traditional research has mainly focused on the effect of intestinal bacteria on IBD, research on intestinal fungi is mostly scattered and lacks systematic analysis and summarization.

This study explored the functions of fungi in various aspects of human gastrointestinal health, focusing on fungal microbiota imbalance, fungal-bacterial interactions, the influence of fungal metabolites, and fungal-based treatment strategies in IBD patients. By systematically integrating the understanding of the role of fungi in the pathogenesis of IBD, the important position of fungi in the intestinal ecosystem is revealed, addressing a significant gap in the field of intestinal microecology These findings will greatly enrich our understanding of the biological diversity and disease relevance of the human gut microbiome.

2 Intestinal fungal colonization in healthy people

Fungi are present in the GIT of all healthy individuals (10, 11), where they can influence the immune system (5) and produce health-affecting secondary metabolites (12, 13). Therefore, understanding a healthy mycobiota may aid in the identification of disease-contributing fungal species and allow a better determination of important fungal-bacterial relationships. The development of molecular biology techniques has significantly deepened the understanding of intestinal fungal diversity. The 18S rRNA gene sequencing provides a basic framework for fungal classification, while ITS2 sequencing has become a sensitive tool for detecting low-abundance fungi, with higher resolution than 18S rRNA gene sequencing, which can distinguish species and strain-level differences (10). However, this technique may omit some fungal information. In contrast, metagenomic sequencing can completely retain the genetic information of fungi by directly extracting the nucleic acids from the sample, allowing for the analysis of the functional genes within the microbiota and revealing the interactions between microorganisms, the environment, and the host (14).

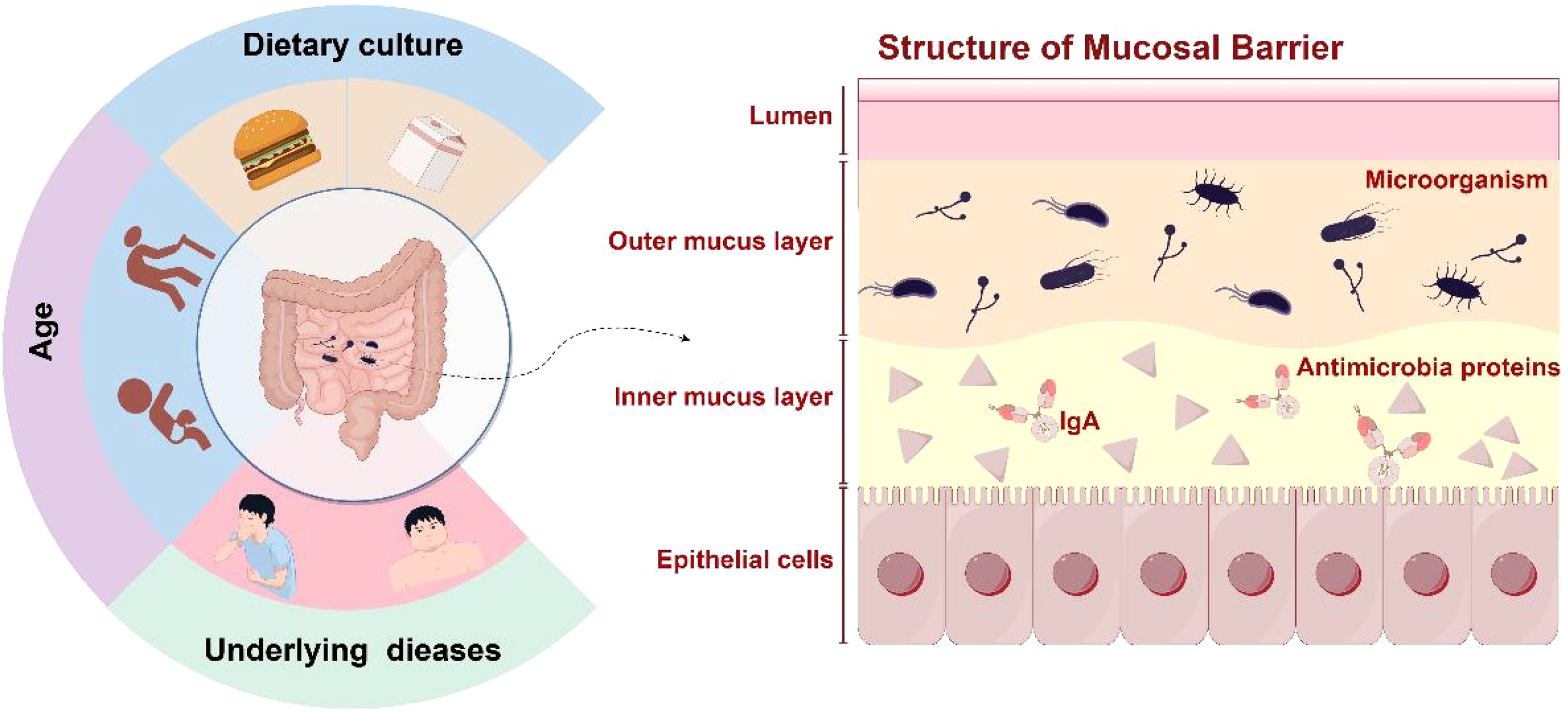

A number of studies have revealed the core composition of the human intestinal fungal group through high-throughput sequencing technology. Analysis of 317 fecal samples by the Human Microbiome Project (HMP) (10) showed that Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Malassezia spp., and Candida albicans were the core fungi with higher prevalence in healthy people. The Chinese Guangzhou Nutrition Health Study (GNHS) (15), based on a cohort of 1,244 middle-aged and elderly people, further expanded this conclusion by identifying 26 core fungal genera, including Saccharomyces, Candida, Aspergillus, and Malassezia, among which Ascomycota and Basidiomycota are dominant. Both studies confirmed the universality of Malassezia and Candida, suggesting that they may play a fundamental role in intestinal microecology. However, sequencing results may be affected by a variety of factors (Figure 1), such as potential diseases carried by volunteers (16), dietary culture (17), age (18), and other factors (19). The GNHS cohort study suggested that age may be a key factor in shaping individual differences in the intestinal fungal group. The abundance of Aspergillus and Penicillium in the body showed significant changes with age (20). Further analysis revealed that the abundance of Bacillus and Trichoderma spp. in the intestines of the elderly decreased significantly, while Malassezia was found to be enriched.

Figure 1

Factors influencing intestinal microbes. Microbial disorders alter the production of surface mucus, epithelial function, and intestinal immune defenses.

As mentioned above, there is a relatively stable core fungal community in the intestine of healthy individuals. Although its abundance is low, it maintains a dynamic balance under the normal regulation of the host's immune system. This homeostasis provides an important baseline for identifying disease-related fungal groups. Current studies have shown that the intestinal fungal communities are not only involved in the regulation of host metabolism but may also affect the disease process through a two-way interaction with the immune system. Research is urgently needed to construct a phylogenetic map of intestinal microecology and to analyze the colonization characteristics of fungi using functional metagenomics and metabolomics techniques. It is worth exploring:

-

(1) Fungi are transient microorganisms that exchange between the human gastrointestinal tract and the external environment. Genetic defects and environmental factors associated with IBD can induce the accumulation and penetration of pathogenic bacteria into intestinal tissues, thereby further promoting an imbalance in the microbial microbiota and inflammation (21). This colonization pattern suggests that disease status may significantly affect the intestinal residence characteristics of fungi, and the detection results can be used as an auxiliary index for disease diagnosis (4).

-

(2) Various types of fungi exist in the gastrointestinal tract of healthy humans, forming a stable core fungal community. When immune surveillance is impaired, these symbiotic fungi can become opportunistic pathogens, potentially leading to chronic inflammation by triggering TH1/TH17 immune responses or disrupting the Treg cell regulatory network (2, 22). In addition, the imbalance of fungi may disrupt the host's regulatory mechanisms for inhibiting inflammation and play an important role in the promotion of the pathogenesis of IBD (21). This mechanism provides a theoretical basis for the targeted regulation of fungal microbiota in the prevention and treatment of IBD.

Regardless of the answer, the role of the intestinal fungal colonization in the occurrence or treatment of diseases cannot be ignored. Analyzing the biodiversity of intestinal fungi and its correlation with diseases remains of great significance. Fungi play a key role in the ecological adaptation of the human gastrointestinal environment by participating in the degradation of fermentable substrates (i.e., polysaccharides, proteins, and lipids) and the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites (23). The Pezizomycotina species are involved in regulating a wider range of metabolic pathways than other fungi, with specific functions concentrated on secondary metabolism, as well as amino acid and carbohydrate transport and metabolism (4). Specifically, these fungi can produce a large number of plant cell wall-degrading enzymes (PCWDEs) for cellulose, hemicellulose, starch, and pectin, which indicates that the Pezizomycotina species may actively participate in the decomposition of plant polysaccharides in the intestines of certain organisms. In addition, Saccharomycotina species have significant proteolytic ability. It is worth noting that fungal secondary metabolites have unlimited potential in treating certain diseases and in synthetic biology. They are a prolific source of antibiotics (such as penicillin and cephalosporins) and immunosuppressive drugs (24), and they play a positive role in maintaining human intestinal health.

3 Inflammatory bowel disease

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic autoinflammatory disease involving the gastrointestinal tract and extraintestinal organs. IBD, includes several clinical histologic variants, such as ulcerative colitis (UC), Crohn's disease (CD), and indeterminate colitis (IC) (21, 25–27). UC is characterized by chronic inflammation of the large intestine with aberrant activation of the immune system (28), manifesting as diffuse and persistent colonic inflammation extending proximally from the rectum. About 40-70% of UC patients are characterized by mild inflammation of the upper gastrointestinal tract (29).CD commonly involves the terminal ileum and colon and may present as an inflammatory, penetrating, stenotic, or mixed phenotype (30). While the inflammation and damage in UC are limited to the mucosa, CD may be a transmural process (30). The latest global epidemiological data show that the prevalence of IBD has reached 0.5-1.5% in European and American countries (31), while the annual incidence in Asia is increasing to a rate of 0.3-0.5%. It is expected that the number of global IBD patients will exceed 8 million by 2025 (32). IBD not only causes severe physiological dysfunction, such as diarrhea, rectal bleeding, and abdominal pain (33–35), but also significantly increases the risk of colorectal cancer.

The pathogenesis of IBD involves three main factors: individual and genetic susceptibility, the gastrointestinal microbial community, and immunological characteristics of the gastrointestinal mucosa (36). The primary pathogenesis of the two forms of IBD (UC and CD) is related to the imbalance of the symbiotic microbiota living in the intestine. When the intestinal barrier function is impaired, symbiotic bacteria and their metabolites penetrate the mucosal layer, triggering the abnormal activation of dendritic cells and leading to a cascade release of pro-inflammatory factors such as IL-6 and TNF-α, which form a chronic inflammatory cycle (21, 37, 38). In addition, active intestinal inflammation is accompanied by excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (39), which leads to oxidative damage, participates in the activation of the intestinal immune system, and exacerbates the inflammatory response (40).

The current clinical treatment for IBD still faces multiple challenges: traditional 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) preparations are only effective for mild UC (41, 42), immunosuppressants (such as azathioprine) are slow to take effect, and there is a risk of bone marrow suppression (43, 44). Although biological agents (such as anti-TNF agents) can quickly induce remission, about 30% of patients develop primary drug resistance (45). Additionally, long-term use may increase the risk of opportunistic infections, such as tuberculosis and lymphoma. Although surgery (such as total colectomy) can cure UC, the postoperative quality of life of patients is reduced, and the recurrence rate of CD is as high as 50% (46). Therefore, new therapies such as targeting intestinal microecology and regulating immune response have emerged as research hotspots. However, their long-term efficacy and safety still need to be further verified.

4 IBD and fungal disorders

Alterations in the gut microbiota play a key role in the onset, progression, and severity of IBD. Diet-related factors, including childhood exposure to antibiotics and dietary emulsifiers (47–49), as well as the Western diet, which contains several high-fat foods and refined sugars, participate in IBD pathogenesis (50, 51). These factors can lead to ecological disorders and are closely related to intestinal inflammation. Intestinal microbes establish a link between the environment and the intestine. Diverse microbial ecosystems inhabit the human body and play a critical role in maintaining host health, including various fungal species known as "fungalome" (10). The study of intestinal fungal microbiota and its correlation with gastrointestinal diseases, especially IBD, has attracted much interest in recent years (Table 1). These studies have provided a new perspective on the etiology and non-invasive diagnosis of gastrointestinal diseases (27, 52). Although research on the fungal group is still in its infancy stage, it is rapidly gaining recognition for its potential role in human disease.

Table 1

| Disease | Sample | Fungal changes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crohn’s disease | Feces | Candida albicans↑ | (54, 57) |

|

Candida↑, Entyloma↑, and Trichosporon↑ Hanseniaspora↓, Hypsizygus↓, Wallemia↓ |

(56) | ||

|

Candida↑

Aspergillus↓, Penicillium genera↓ unclassified Sordariomycetes↓ |

(164) | ||

| Mucosa | Cystofilobasidiaceae family↑, Dioszegia genera↑, Candida glabrata↑ | (62) | |

|

Ascomycetes↑, Basidiomycetes↓ Malassezia restricta↑, Cladosporium↑ Fusarium↓ |

(165) | ||

| Debaryomyces hansenii↑ | (63) | ||

| Ulcerative colitis | Feces | Dipodascus↑, Entyloma↑ | (56) |

| Candida↑ | (4, 9) | ||

| Mucosa |

Scytalidium↑, Morchella↑, Paecilomyces↑ Humicola↓, Wickerhamomyces↓ |

(166) | |

|

Candida↑

Saccharomyces↓ |

(8) | ||

| IBD | Feces |

Candida albicans↑

Saccharomyces cerevisiae↓ |

(54) |

| Shannon diversity↓ | (4) |

Changes in fungal microbiota in IBD patients.

↑ indicates a significant increase in fungal abundance/activity.

↓ indicates a significant decrease in fungal abundance/activity.

The gastrointestinal tract contains highly diverse fungi, which is the most studied fungal niche in humans. A total of 66 genera (divided into about 180 species) have been identified via ITS amplicon sequencing and whole genome sequencing of marker genes in DNA purified from feces. Ascomycota and Basidiomycota are dominant in the fungal group (53–55). Notably, Candida, Saccharomyces, and Cladosporium are the most abundant fungal genera in healthy individuals (38). In a small sample study in Japan (56) with 18 UC patients, 20 CD patients, and 20 healthy controls, sequencing results showed that there was no change in the abundance ratio of Ascomycota and Basidiomycota during IBD remission. However, another study (54) showed that the expansion of Basidiomycota and the reduction of Ascomycota occur during the onset of IBD. The study investigated the imbalance of fungal microbiota in IBD patients and found that the fungal burden of colonic mucosa increases during CD and UC (57, 58). Besides, several studies have shown that the abundance of C. albicans increases in IBD patients (54, 57). Furthermore, the abundance of C. albicans and Candida parapsilosis is increased in the inflammatory mucosa of CD patients (59). Meanwhile, the incidence and abundance of culturable C. albicans are increased in the feces of IBD patients (37, 60). Furthermore, the proportion of Candida tropicalis (61) is increased in the intestinal tract of CD patients and is positively correlated with the incidence of familial CD. Similarly, the abundance of Candida glabrata (62) and Debaryomyces hansenii (63) also increases in CD patients, especially in the inflammatory mucosa. Fungal dysregulation occurs in IBD patients, indicating that fungi play an indispensable role in maintaining the balance of intestinal microbiota.

5 Interaction of fungi with the host immune system

Fungi are common inhabitants of the intestinal barrier surface. The stability of the fungal community is essential for maintaining intestinal health. Abnormal changes in the fungal community(dysbiosis) can affect surface mucus production, epithelial function, and intestinal immune defense, thereby damaging the intestinal barrier and increasing its permeability (7, 64). Furthermore, changes in intestinal barrier permeability can allow opportunistic fungi or their components to enter the circulatory system (65, 66). At present, research on the interaction between specific fungi and the host immune system not only focuses on C. albicans (67) and S. cerevisiae (54), but also explores other fungi, such as Cryptococcus neoformans (68, 69) and Aspergillus fumigatus (70). However, there is still a lack of understanding regarding how the host immune system timely and accurately recognizes various mechanisms of fungal invasion and colonization (71).

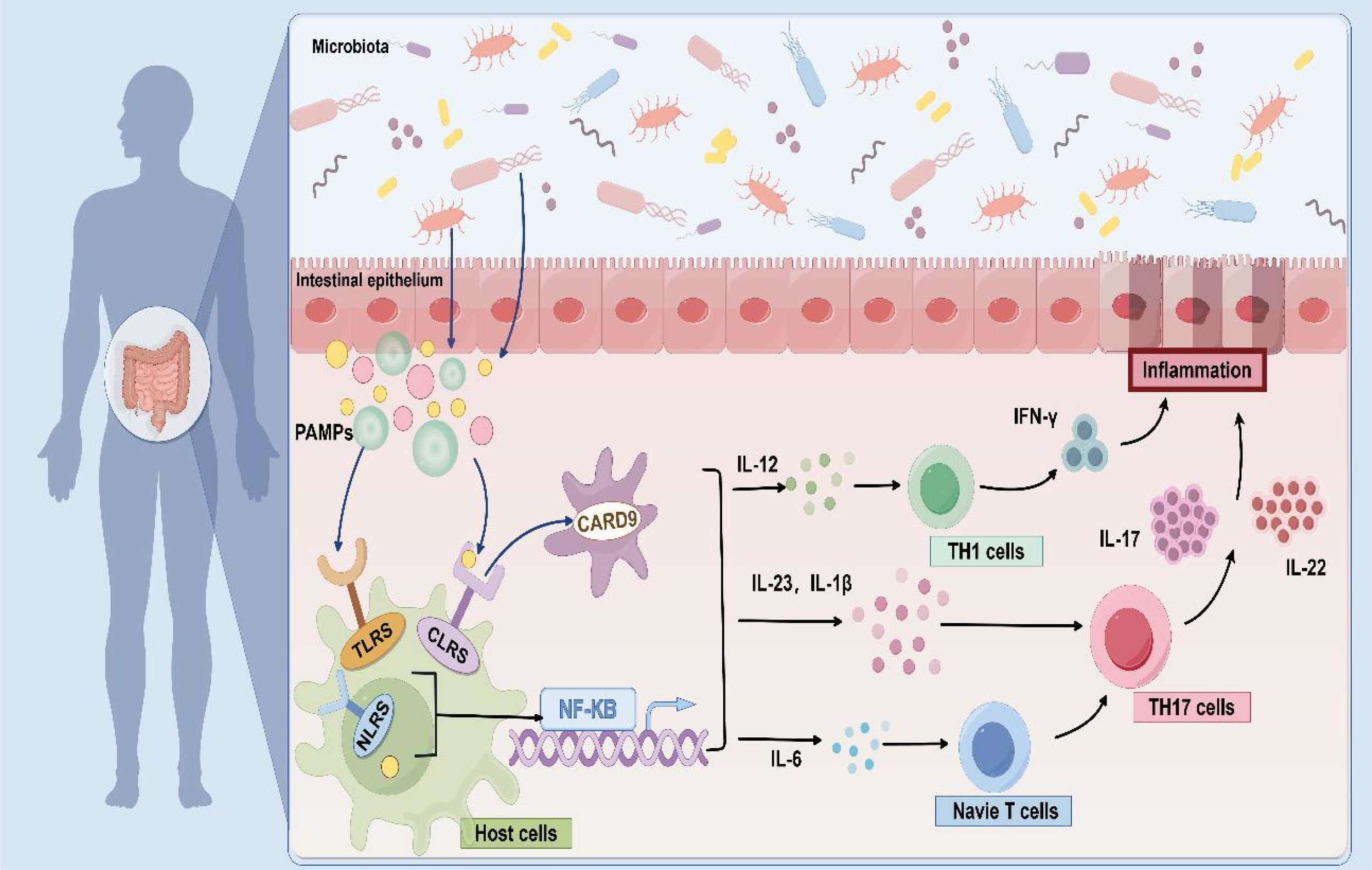

Fungi can induce unique local and systemic cytokine signals through multiple pathways. Dectin-1, CARD9, and IL-17 signaling pathways may be immune drivers of fungal dysbacteriosis in the development of IBD and participate in the regulation of the stability of the intestinal internal environment. The signaling cascade suggests that fungal dysbiosis can activate host protective immune pathways related to epithelial barrier integrity (72), release various pro-inflammatory cytokines to trigger inflammatory responses, thus promoting the occurrence and development of IBD. As an important part of the immune system, macrophages can recognize various complexes, such as β-glucan on the fungal cell wall (66, 73), then activate the body's innate and acquired immune response through the release of a variety of cytokines (74). Macrophages can also trigger inflammatory responses associated with IBD (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Fungal-induced immune response. As pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), fungal cell wall components are recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), and which activate various signal cascades by inducing CARD9 to release a variety of cytokines, such as IL-12, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-23, and so on. These cytokines further promote TH1 and TH17 cell responses and initiate immune function to modulate fungal immune recognition.

Phagocytes express and activate members of the C-type lectin receptors (CLRs), Dectin-1, Dectin-2, and Mincle (75), as well as pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) (76), such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs) (77) and Nod-like receptors (NLRs) during this immune response, which have secondary roles on the surface of the host cells. Taking C. neoformans as an example, its capsular polysaccharide can be recognized by TLR4, thereby initiating an immune response (78). Additionally, the cell wall components of A. fumigatus can activate the NLRP3 inflammasome and cause inflammation (79). Phagocytes then recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and signaling, inducing a signaling cascade via caspase-associated recruitment domain 9 (CARD9) (80) and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines in response to innate immunity, and dendritic cells to release TH17 and TH1 in response to acquired immunity (81).

The pro-inflammatory environment further drives the differentiation of TH17 cells, closely linking the immune system with intestinal tissue and becoming central to the fungal immunopathology of IBD. The Dectin-1-CARD9 axis specifically induces TH17 cells to produce IL-17 and IL-22 by regulating the secretion of IL-23 and IL-1β (2, 74, 82). It's important to highlight that there are differences in the regulation of type 17 immunity by different fungi. This immune response is particularly significant when C. albicans is present; its β-glucan can activate dendritic cells through Dectin-1, promote the secretion of IL-12 and TNF-α, and enhance the pathogenicity of TH17 cells (83). S. cerevisiae has been reported to promote the induction of Treg cells through the Dectin-1-Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) signal transduction axis and to directly inhibit the production of IFN-γ, which differentiates TH1 cells, through a TLR2-dependent mechanism, thereby reducing the inflammatory response in a dual manner (84, 85). Malassezia can aggravate skin and mucosal inflammation in patients by activating the IL-23/IL-17 axis (86). This two-way regulation mechanism suggests that targeting the fungi may become a new direction for IBD treatment. For example, Dectin-1 and Dectin-2 double gene knockout can effectively prevent intestinal inflammation by changing the intestinal microbiota of bacteria (87).

6 Pathogenic mechanism of fungi

The previous section discusses the abnormal activation of the host immune system by intestinal fungi, which leads to an inflammatory response. Therefore, it is necessary to explain the process of fungal pathogenesis. Fungi can elicit immune responses from susceptible hosts through various mechanisms, including mycelium formation, secretion of fungal cytolytic peptide toxins, and secretion of EVs, thus leading to the development of diseases.

6.1 Candidalysin

Candidalysin is one of the fungus-derived metabolites that plays a key role in host-microbe interactions. Candidalysin is potentially responsible for invasive mucosal infections and tissue damage, which can impact IBD (88). Candidalysin activates epithelial pro-inflammatory responses via two mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways (p38/c-Fos transcription factor and MEK/ERK/MKP1) and induces downstream immune responses (89, 90), including neutrophil recruitment and innate type 17 immunity (91). MAPK signaling is a "danger-response" pathway that releases large amounts of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GMCSF), triggering the recruitment of neutrophils, macrophages, and other immune cells, thus inducing local inflammatory response (6).

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) may be activated through the shedding of endogenous ligands, such as amphiregulin (AREG), epigen (EPG), and epiregulin (EREG) from epithelial cells through Ca2+ in-flow and Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), thereby activating downstream mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling (c-Fos transcription factor and MKP1), thus activating epithelial immunity (6).

Studies have shown that Candidalysin can also induce MAPK signaling through MEK1/2 and ERK1/2, leading to the activation of the AP-1 transcription factor c-Jun/c-Fos and up-regulation of the secretion of neutrophil-collecting chemokine (C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 8, CXCL8). This results in the recruitment of several neutrophils to the site of infection, triggering excessive inflammation and causing vascular endothelial cell injury (88).

6.2 Extracellular vesicles

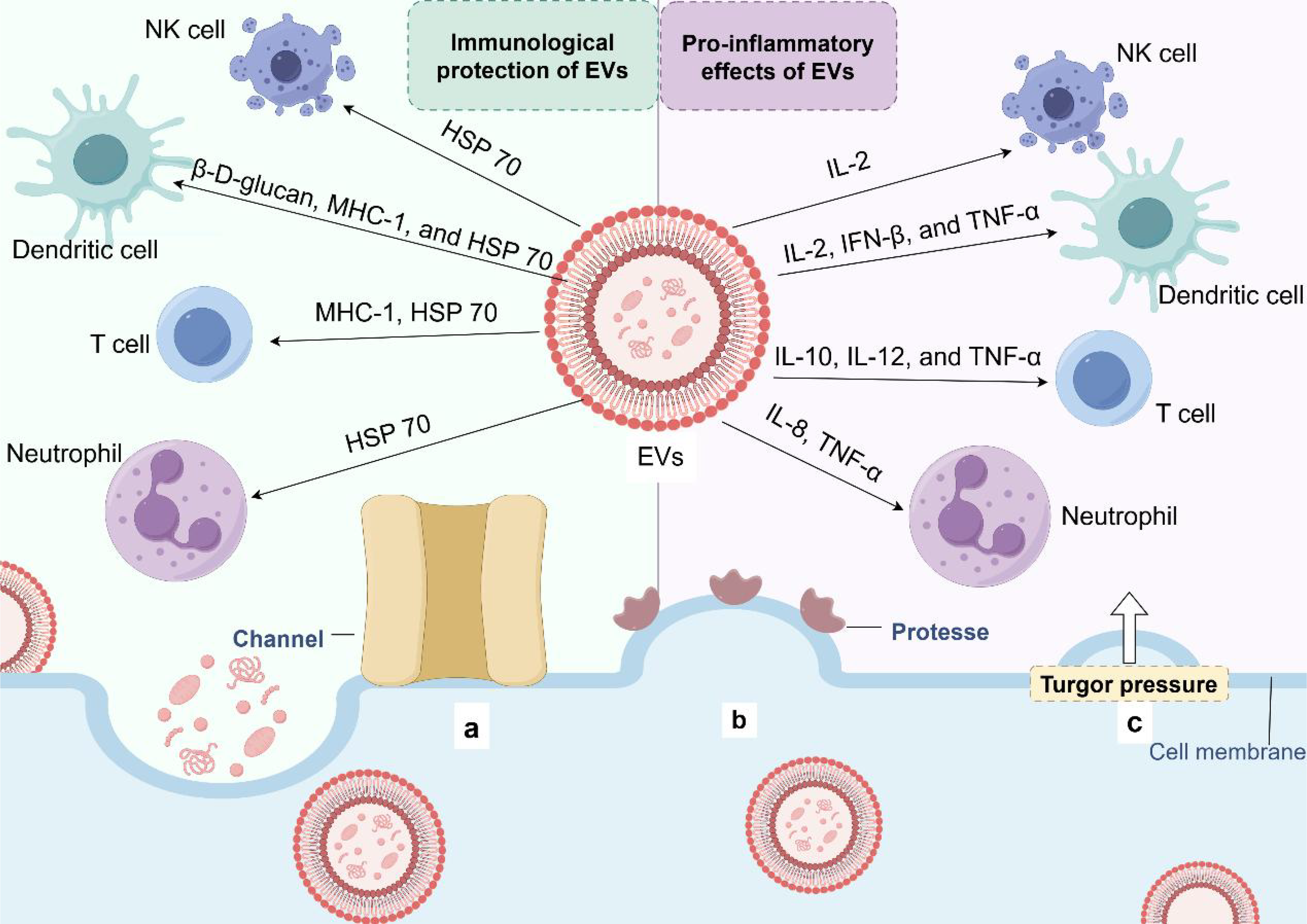

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) produced by eukaryotes, archaea, and bacteria are lumen-containing spheres with a diameter of 20-500 microns. EVs consist of a lipid bilayer containing lipids, proteins, polysaccharides, pigments, and nucleic acids (92). The release of EVs is an alternative transport mechanism for macromolecules across the fungal cell wall (93, 94). The vesicles move outward across the cell wall, eventually reaching the extracellular environment (95–100). Besides, the impact of EVs in pathological and physiological processes is under investigation (101–104). The cell wall and capsule structure are major pathogenic factors in most fungal species because they protect cells from unfavorable environmental conditions and host immune factors, ensuring their survival (105). Therefore, the involvement of fungal EVs in the biogenesis and maintenance of capsule and cell walls can be considered a pathogenic mechanism. Recent studies have shown that these vesicles are associated with key virulence factors. Besides, EVs are biologically active, causing host cell death (106) and triggering an immune response (107, 108).

EVs from several pathogenic fungi play a “double-edged sword” role in the regulation of the immune system (109) (Table 2, Figure 3). EVs play an important role in fungal infection and dissemination, acting as mediators of cellular communication, thus influencing interactions between fungi and host cells (macrophages (110, 111) and dendritic cells (112, 113)) and transmitting virulence factors to the host. EVs increase cryptococcal passage across the blood-brain barrier and allow cryptococcal-derived EVs to accumulate in fungal brain damage, suggesting a novel role for EVs in fungal pathogenesis (114). Fungal EVs can directly influence biofilm production and regulate dimorphism in C. albicans. Studies have shown that yeast-produced C. albicans EVs can induce filamentation and growth of C. albicans (115). EVs reduce the intracellular ROS and apoptosis of C. albicans by activating the L-arginine/NO pathway, thus enhancing the damage to the host cell caused by C. albicans (106).

Table 2

| Types | Functions | |

|---|---|---|

| Pro-inflammatory | Immune potential | |

| Candida albicans EVs | In the early stage of C. albicans infection, blood monocytes released EVs with a large number of functional important microRNAs, which induced significant growth and hyphal formation of C. albicans (167). | Fungal EVs from C. albicans activate humoral immune responses, which decreases the fungal load in immunosuppressed mice and produce immune protection (168). |

| EVs have an interchangeable role in biofilm drug tolerance and dispersion, and are the core of biofilm pathogenicity (169). | EVs decrease the adhesion and invasion ability of C. albicans by inhibiting the differentiation of yeast into hyphae, which reduces fungal virulence (108). | |

| EVs inhibit ROS production by activating the L-arginine / nitric oxide pathway to reduce apoptosis and promote the growth of C. albicans (106). | EVs derived from Candida haemulonii var. vulnera have immunogenicity and stimulate bactericidal function in mouse macrophages by stimulating the production of ROS (170). | |

| EVs activate inflammatory responses in polymorphonuclear cells and RAW264.7cells in vitro (171). | In vivo experiments demonstrated that EVs inoculated with C. albicans provided a protective response mediated by TLR4-dependent activation in mice infected with fungi (172). | |

| Cryptococcus neoformans EVs | EVs regulate the generation of inflammatory cytokines through bone marrow-derived dendritic cells and macrophages (173). | Protective antigens are present on the surface of EVs, producing a strong antibody response in mice and have the potential as a vaccine (174). |

| Aspergillus flavus EVs | EVs stimulate macrophages to generate inflammatory mediators, enhance the phagocytosis and killing effect of macrophages, and promotes M1 macrophage polarization in vitro (175). | EV proteome cargo in fungal endophthalmitis has host immune-related proteins, such as complement component 8α, acting as an crucial antibacterial immune effector (176). |

| Talaromyces marneffei EVs | The RAW264.7 macrophages interact with EVs upregulating IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-α levels, promoting inflammatory response (177). | EVs can effectively regulate the function of macrophages, thereby activating these innate immune cells and enhancing their antibacterial activity (178). |

The bidirectional immunoregulatory effect of EVs.

Figure 3

Extracellular vesicle release and immune potential. (a) Protein channels may modulate the transport of EVs in the extracellular environment. (b) The 'loose' effect of cell wall-modifying enzymes may promote EV release. (c) EVs pass through the wall under the influence of turgor pressure.

6.3 Fungal-bacterial interactions

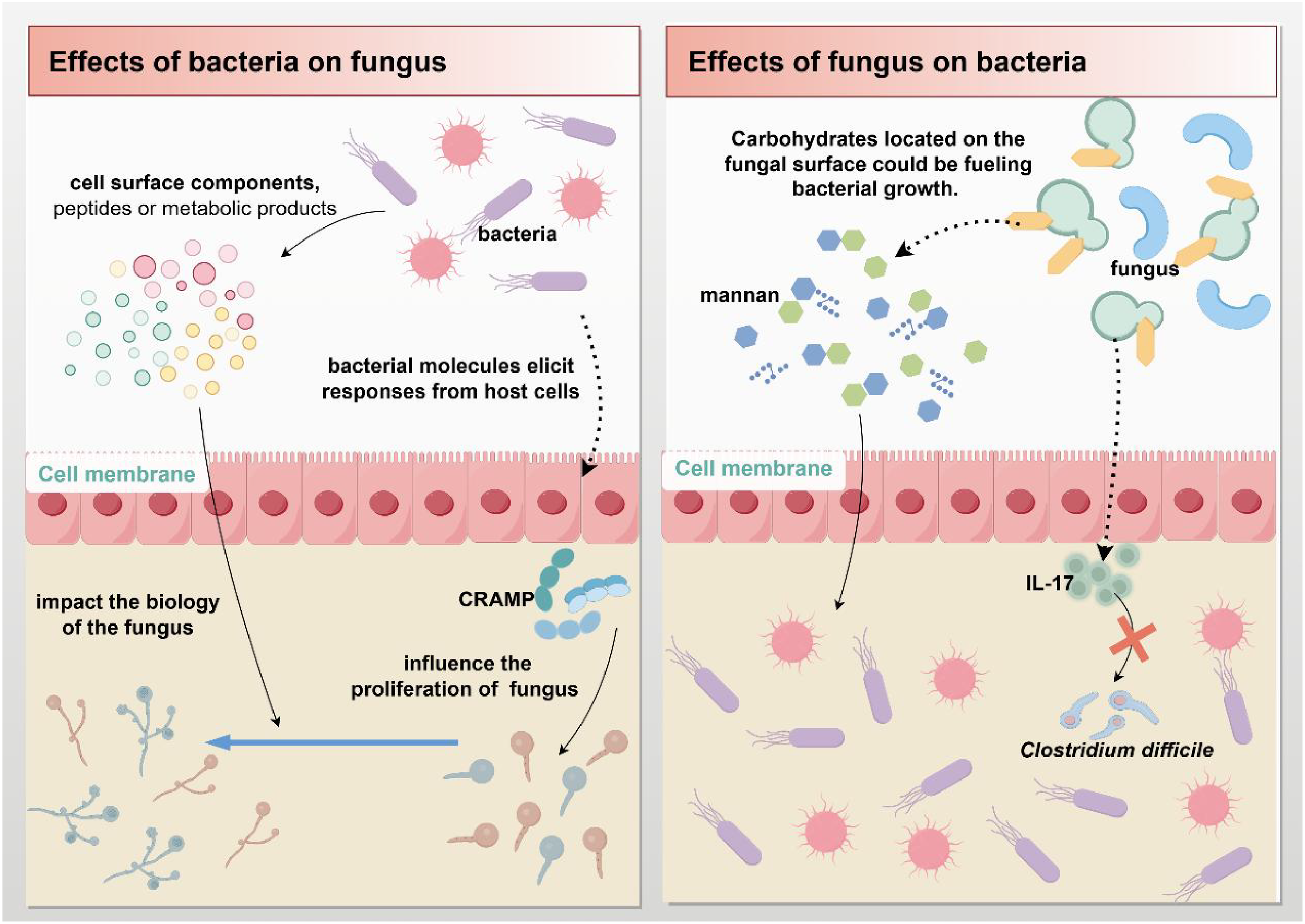

Fungi or any other microbial group can function alone in a crowded ecosystem, such as the human gut (116). Dysbiosis of the intestinal microbiota, a collective feature of complex interactions between prokaryotic and eukaryotic microbial communities, can affect immunity and render normally benign symbiotic organisms pathogenic (117). The importance of these fungal-bacterial interactions in human health and disease has attracted much attention in recent years. Intestinal fungi and bacteria interact with each other in various ways, including chemical or physical interactions, competition for nutrients or adhesion sites, and hybrid biofilm formation (61) (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Fungal-bacterial interactions. Gut microbes can directly or indirectly influence each other's biological processes by secreting molecules (such as cell surface components, peptides, and metabolites) or triggering immune responses from host cells.

6.3.1 Bidirectional action of bacteria on fungi

Studies have shown that gut bacteria can affect the proliferation of C. albicans or other fungi (or influence any other fungal trait) through at least two primary mechanisms: First, an indirect pathway involving bacterial molecules (or microorganisms) triggering host cell responses on fungi (116). Bacteria limit fungal proliferation by stimulating the production of intestinal mucosal immune defenses, particularly the antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin-related antimicrobial peptide (CRAMP) (118). Second, the release of molecules, such as cell surface components, peptides, or metabolites, which can directly influence fungal biology (116). Bacteria can promote C. albicans infection and increase the risk of disease through released peptidoglycan subunits (119–121). An in vitro co-culture study found that Escherichia coli can produce a soluble factor that kills C. albicans in a magnesium-dependent manner (122).

Meanwhile, studies have shown that pathogenic bacteria in the gut can produce fungal modifying compounds and secreted enzymes, which affect the composition of the intestinal fungal community (123). Streptococcus mucosus produces two secreted proteins, Tfe1 and Tre2, which induce antifungal effects by reacting with C. albicans and yeasts (124). Peptides and toxins secreted by the bacteria may also act on nearby cells, thus inhibiting fungal infection and colonization. Enterococcus faecalis is a Gram-positive commensal bacterium that parasitizes the human gastrointestinal tract. E. faecalis can produce an active peptide containing 68 amino acids (EntV), which can inhibit the formation of C. albicans hyphae and prevent biofilm formation (125, 126).

6.3.2 Bidirectional action of fungi on bacteria

Fungi and bacteria have similar morphologies on the surface of the intestinal mucosa and can interact with each other. Dysregulation of the fungal microbiota in the intestine often leads to changes in the composition of the bacterial microbiota (117). C. albicans can increase resistance of Staphylococcus aureus to antibiotics by secreting farnesol (127, 128). Also, carbohydrates on fungal surfaces can promote bacterial growth. The simpler sugars produced by the digestion of mannan by Bacteroides spp. enzymes promote the proliferation of Bacteroides spp (129). Meanwhile, fungi are resistant to bacterial infections. A study showed that C. albicans can protect mice against lethal Clostridium difficile infection, partly through the promotion of the production of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-17 (130).

These findings indicate that intestinal fungi closely interact with bacteria. This interaction may play an important role in the development of IBD. However, studies on the interactions between intestinal fungi and bacteria in IBD patients are still in the infancy stage, and the specific modes of interaction are unclear. Therefore, more in-depth studies are needed to reveal the physical and chemical interactions between intestinal fungi and bacteria in IBD.

7 Fungal-based treatment

The previous sections expound on the role of fungi in various aspects of human gastrointestinal health, focusing on fungal-host immune system interactions, fungal-bacterial interactions, and the influence of fungal metabolites. The following section focuses on exploring the treatment of IBD by targeting fungi based on the aforementioned pathogenic mechanisms.

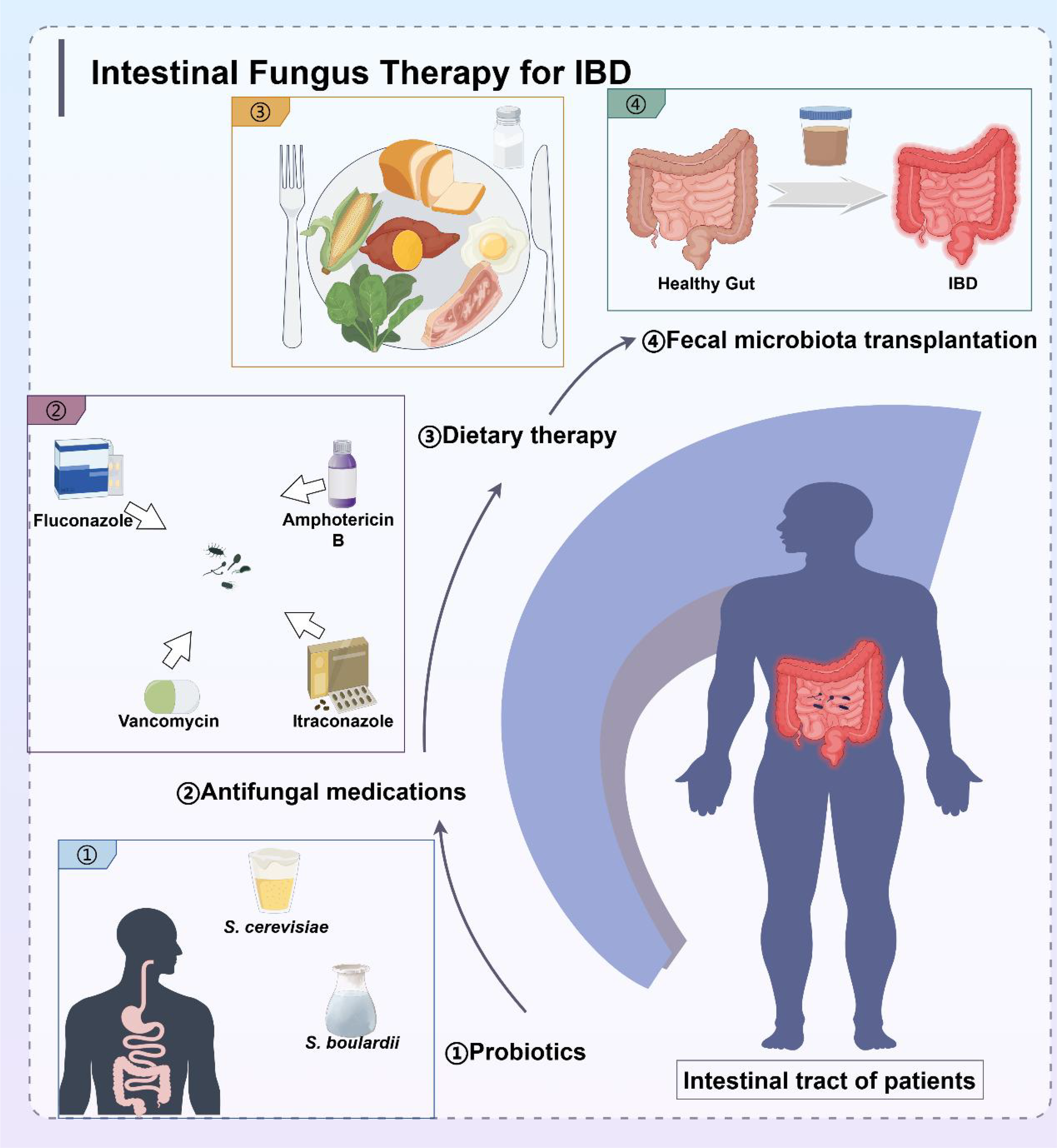

Standard clinical treatment for IBD consists of drugs that modulate the inflammatory pattern of gastrointestinal tract, including mesalazine, azathioprine, anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and glucocorticoids (131). However, these drugs have serious side effects. Besides, some patients require higher doses throughout the treatment. Although the exact etiology of IBD is unknown, the critical role of gut fungi in the development and persistence of IBD highlights the importance of fungal microbiota-host interactions in health and disease. Therefore, targeting the intestinal fungal group and its metabolites may be a novel strategy for IBD treatment. The gut fungal microbiota affects the host by modulating physiological, pathophysiological, and immune processes. Experimental animal studies and clinical data have demonstrated that gut mycobiome ameliorates inflammation, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic strategy for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Probiotics (132), antifungal medications, dietary therapy, and fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) are the most common IBD treatments (Figure 5). UC typically involves a local mucosal immune response, whereas CD is mostly a transmural process that engages a broader cross-level immune response. Due to these different immune mechanisms, the correlation between fungi and bacteria in UC and CD patients varies significantly. Specifically, the positive and negative correlations between bacteria and fungi in UC patients are stronger than those in CD patients, which also leads to differences in the treatment methods for these two diseases. Antifungal therapy and probiotic therapy are more conducive to the recovery and healing of colon injury of UC, while most patients with CD eventually require surgical treatment, with fungal-based treatment playing a supportive role.

Figure 5

Treatment strategies for IBD targeting intestinal microbiota, including probiotics, antifungal medications, dietary therapy, and fecal microbiota transplantation.

7.1 Probiotics

The beneficial effects of probiotics have been clearly demonstrated to prevent the recurrence of pouchitis in patients after colectomy (133), and certain specific probiotics also seem to directly regulate intestinal pain. Although bacteria, such as Lactobacillus spp. and Bifidobacterium spp., are the most widely used probiotic microorganisms, some fungi can become probiotics due to their health benefits (134). Fungal probiotics possess several favorable properties: First, fungi are naturally resistant to antibiotics and can thus be used in combination with them to treat certain diseases (135). S. cerevisiae is the most studied fungal probiotic and probably the most promising fungal probiotic species. The intervention of S. cerevisiae can increase the diversity of intestinal microbiota in mice with UC, improve the microbiota structure, decrease the relative abundance of the harmful bacteria Escherichia-Shigella (136) and Turicibacter (137), and increase the relative abundance of the beneficial bacterium Lactobacillus (136). Additionally, S. cerevisiae can significantly improve the physiological condition of mice with colitis, alleviate the histopathological damage of the colon, and enhance the intestinal mucus layer (136). S. cerevisiae can alleviate UC by up-regulating the expression of tight junction protein-related genes in Caco-2 cells (136, 138) and down-regulating the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokine-related genes (136, 139, 140). Kunyeit et al. examined the effects of food-derived S. cerevisiae, as a probiotic, on cell morphology and filament formation (141). The results showed that S. cerevisiae significantly inhibited the mycelial development of Candida tropicalis and Candida parapsilosis, and could better resist pathogenic damage from fungi.

Saccharomyces boulardii is another probiotic fungus with ecological regulatory effects that has been widely used for UC treatment. Sougioultzis et al. (142) found that S. boulardii induces anti-inflammatory activity through the production of a low molecular weight soluble substance that inhibits NF-κB activation in monocytes and intestinal epithelial cells. Animal experiments have shown that S. boulardii solution can significantly alleviate intestinal inflammation in rats with 2, 4, 6-Trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid (TNBS)-induced colitis (143). In vitro explant experiments showed that S. boulardii recovers the tight junctions between intestinal epithelial cells, restores and strengthens the intestinal barrier function by enhancing E-cadherin expression via RAB11A-dependent endosomal recycling (144).

7.2 Antifungal medications

Antimicrobial treatment reduces bacterial abundance and can indirectly affect fungal microbiota. A study has shown that in the case of intestinal inflammation, the positive and negative effects of fungi depend on the presence of Enterobacteriaceae bacteria. Specifically, mice treated with vancomycin (targeting Gram-positive bacteria) were completely protected from colitis, while mice treated with colistin (targeting Enterobacteriaceae) retained the colitis phenotype but were no longer affected by fungal administration (145). Fluconazole, an antifungal drug, is commonly used to treat fungal infections such as candidiasis and candidemia in patients with immunosuppressed IBD. In a study involving 89 UC patients, 20 patients with high fungal colonization showed a significant decrease in the disease activity index, as reflected by clinical, endoscopic, and histological criteria, after 4 weeks of fluconazole treatment compared to the placebo group and the probiotic Lacidofil group (36). Studies have shown that amphotericin B and itraconazole can be used to treat infections caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, significantly reducing or completely eradicating the pathogen (146, 147). The incidence of Histoplasma capsulatum infection is high in patients with colitis. Itraconazole can alleviate the symptoms of IBD, especially in UC patients, can achieve both clinical and endoscopic remission (148). The above drugs restore the balance of intestinal microorganisms through antifungal drug treatment, which proves the feasibility of targeted fungal treatment for IBD.

7.3 Dietary therapy

Studies have demonstrated that diet can shape the composition of the gut microbiota. Gut microbes utilize diet-derived nutrients to grow and colonize the gut (149). In contrast, host cells use microbial metabolites as substrates for energy production and immunomodulators to maintain gut homeostasis. This symbiotic relationship between the gut microbiota and the host is critical to the human health (21). Dietary therapies can independently influence the composition of microbiota to reduce inflammation, and changes in the composition of a single food group may have profound effects. Switching from a plant-based to an animal-based diet radically alters bacterial taxa and metabolism, causing alterations to bile acid and sulphide metabolism, both of which influence the development of UC (150). Consumption of certain diets, such as Western diets characterized by high fat and low fiber may induce dysbiosis of the gut microbiota, disrupting intestinal homeostasis and promoting intestinal inflammation (151). A study comprising 98 healthy adults (152) reported that the abundance of Candida was positively associated with a carbohydrates-rich diet and negatively associated with a diet rich in protein, fatty acids, and amino acids (153). The abundance of Aspergillus was negatively associated with recent intake of short-chain fatty acids (152). Dietary fiber is broken-down to short-chain fatty acids by gut microbes, providing a protective effect. A clinical study (154) showed that the intake of fruits and vegetables was negatively correlated with the risk of IBD and its subtypes. Additionally, dietary fiber intake was negatively correlated with the incidence of CD, but not with UC. Herba houttuyniae is a potential dietary intervention, and the extract Sodium houttuyfonate induces β-glucan production and stimulates intestinal macrophages to clear colonized C. albicans (155, 156). Coconut oil reduces gastrointestinal colonization by the opportunistic pathogen C. albicans and has anti-inflammatory, hypolipidemic, and antidiabetic effects (157).

7.4 Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT)

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) is a strategy used to transfer feces from a healthy donor to the gut of a patient with IBD (158), with the aim of restoring microbial homeostasis. To date, some patients with IBD treated with FMT show variable response, with about 30% of patients with UC achieving clinical remission (159). The therapeutic efficacy of FMT has been attributed to gut bacteria for a long time, however, in recent years the important role of gut fungi in FMT outcomes has also been revealed (160).

Patients with IBD are susceptible to C. difficile infections and often exhibit increased abundance of C. albicans (161). Studies have shown that FMT modulates the intestinal fungal composition of patients (162) and is particularly effective in UC patients with high abundance of intestinal Candida. FMT treatment decreased C. albicans abundance in patients with UC and alleviated IBD severity by inhibiting the pro-inflammatory immune response induced by intestinal fungi (162). However, only a small group of patients showed good response to FMT, and further studies are needed to explore whether other intestinal fungi may influence its efficacy. The latest research (163) has demonstrated that C. albicans exhibits antagonism with Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Lactobacillus, and Salmonella, suggesting that it may be a promising treatment for C. albicans.

However, the role of intestinal fungi in FMT is not fully understood with some questions remaining to be unanswered (158). Further studies should explore the adverse effects of FMT and develop strategies to prevent damage to the host (72). For example, the presence of C. albicans in the feces can inhibit the clearance of C. difficile when fecal fungal transplants are administered to treat C. difficile infections. In addition, complex fungal-bacterial interactions may decreased the efficacy of FMT.

8 Conclusions

This paper analyzes the relationship between dysfunctional fungal microbiota and inflammatory bowel disease, as well as the pathogenic mechanisms of intestinal fungi. Although there are significant differences in the experimental studies of intestinal fungal colonization among healthy individuals in various countries and regions, there are commonalities in the dynamic changes associated with IBD. Fungal-host immune interactions and fungal-bacterial interactions are considered important mechanisms by which the intestinal fungal modulates IBD. Fungi can induce unique local and systemic cytokine signals through various mechanisms. TH17 cells play a critical role in linking the immune system to intestinal tissues, helping to regulate specific symbiotic bacteria and fungi, which is crucial for the pathogenesis of fungal infections. By understanding the fungal-bacterial-host interactions, we can identify patients at risk of IBD and develop customized interventions for the microbiome to reduce the serious side effects of traditional IBD treatments. Nevertheless, there are some limitations that need to be mentioned. Firstly, although genome sequencing technology was employed to identify key fungal species, there is currently little data for describing the fungal microbiome, especially those involved in the development of IBD. Secondly, the impact of intestinal fungal-bacterial associations in IBD are not fully understood. To increase our understanding of the specific role of microbiome in health and disease, more studies are advocated.

Statements

Author contributions

SC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MY: Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XY: Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YZ: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HS: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MZ: Data curation, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 82374429 and 82004427), the Key Research and Development Program of Hunan Province (no. 2024JK2122), the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (nos. 2023JJ30460 and 2023JJ30), the High-level Talent Project of Hunan Provincial Health Commission (No. 20240304116), the Guidance Project of Academician Liu Liang’s Expert Workstation (no. 22YS003), and the Youth Talent Support Project of the Chinese Association of Traditional Chinese Medicine (No. 2024-QNRC2-B25).

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Prof. Qinghua Peng from Hunan University of Chinese Medicine for his continuous help and support to our study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

IBD, Inflammatory bowel disease; CD, Crohn's disease; UC, Ulcerative colitis; IC, Indeterminate colitis; ITS, Internal Transcribed Spacer; HMP, Human Microbiome Project; GNHS, Guangzhou Nutritional Health Study; PCWDEs, plant cell wall-degrading enzymes; ROS, reactive oxygen species; 5-ASA, 5-aminosalicylic acid; CLRs, C-type lectin receptors; PRRs, pattern-recognition receptors; TLRs, Toll-like receptors; NLRs, Nod-like receptors; PAMPs, pathogen-associated molecular patterns; CARD9, caspase-associated recruitment domain 9; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; COX-2, Cyclooxygenase-2; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MEK, mitogen-activated extracellular signal-regulated kinase; ERK, extracellular regulated protein kinases; MKP1, MAPK phosphatase 1; GMCSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; MMP, Matrix metalloproteinases; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; NLRP3, NOD-like receptor thermal protein domain associated protein 3; CXCL8, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand; EVs, Extracellular Vesicles; CRAMP, cathelicidin related antimicrobial peptide; TNF, anti-tumor necrosis factor; TNBS, 2,4,6-Trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid; FMT, fecal microbiota transplantation.

References

1

Allegretti JR Khanna S Mullish BH Feuerstadt P . The progression of microbiome therapeutics for the management of gastrointestinal diseases and beyond. Gastroenterology. (2024) 167:885–902. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2024.05.004

2

Leonardi I Gao IH Lin W-Y Allen M Li XV Fiers WD et al . Mucosal fungi promote gut barrier function and social behavior via Type 17 immunity. Cell. (2022) 185:831–846.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.01.017

3

Brown GD Denning DW Gow NAR Levitz SM Netea MG White TC . Hidden killers: human fungal infections. Sci Transl Med. (2012) 4:165rv13. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004404

4

Yan Q Li S Yan Q Huo X Wang C Wang X et al . A genomic compendium of cultivated human gut fungi characterizes the gut mycobiome and its relevance to common diseases. Cell. (2024) 187:2969–2989.e24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2024.04.043

5

Iliev ID Funari VA Taylor KD Nguyen Q Reyes CN Strom SP et al . Interactions between commensal fungi and the C-type lectin receptor Dectin-1 influence colitis. Sci (New York NY). (2012) 336:1314–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1221789

6

Ho J Yang X Nikou S-A Kichik N Donkin A Ponde NO et al . Candidalysin activates innate epithelial immune responses via epidermal growth factor receptor. Nat Commun. (2019) 10:2297. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09915-2

7

Qin X Gu Y Liu T Wang C Zhong W Wang B et al . Gut mycobiome: A promising target for colorectal cancer. Biochim Et Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. (2021) 1875:188489. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2020.188489

8

Li XV Leonardi I Putzel GG Semon A Fiers WD Kusakabe T et al . Immune regulation by fungal strain diversity in inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. (2022) 603:672–8. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04502-w

9

Jangi S Hsia K Zhao N Kumamoto CA Friedman S Singh S et al . Dynamics of the gut mycobiome in patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2024) 22:821–830.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.09.023

10

Nash AK Auchtung TA Wong MC Smith DP Gesell JR Ross MC et al . The gut mycobiome of the Human Microbiome Project healthy cohort. Microbiome. (2017) 5:153. doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0373-4

11

Rao C Coyte KZ Bainter W Geha RS Martin CR Rakoff-Nahoum S . Multi-kingdom ecological drivers of microbiota assembly in preterm infants. Nature. (2021) 591:633–8. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03241-8

12

Guillamón E García-Lafuente A Lozano M D’Arrigo M Rostagno MA Villares A et al . Edible mushrooms: role in the prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Fitoterapia. (2010) 81:715–23. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2010.06.005

13

Ianiro G Tilg H Gasbarrini A . Antibiotics as deep modulators of gut microbiota: between good and evil. Gut. (2016) 65:1906–15. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312297

14

Kim CY Ma J Lee I . HiFi metagenomic sequencing enables assembly of accurate and complete genomes from human gut microbiota. Nat Commun. (2022) 13:6367. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-34149-0

15

Shuai M Fu Y Zhong H-L Gou W Jiang Z Liang Y et al . Mapping the human gut mycobiome in middle-aged and elderly adults: multiomics insights and implications for host metabolic health. Gut. (2022) 71:1812–20. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-326298

16

Galloway-Peña J Iliev ID McAllister F . Fungi in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. (2024) 24:295–8. doi: 10.1038/s41568-024-00665-y

17

Kolodziejczyk AA Zheng D Elinav E . Diet-microbiota interactions and personalized nutrition. Nat Rev Microbiol. (2019) 17:742–53. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0256-8

18

Mercer EM Ramay HR Moossavi S Laforest-Lapointe I Reyna ME Becker AB et al . Divergent maturational patterns of the infant bacterial and fungal gut microbiome in the first year of life are associated with inter-kingdom community dynamics and infant nutrition. Microbiome. (2024) 12:22. doi: 10.1186/s40168-023-01735-3

19

Blake SJ Wolf Y Boursi B Lynn DJ . Role of the microbiota in response to and recovery from cancer therapy. Nat Rev Immunol. (2024) 24:308–25. doi: 10.1038/s41577-023-00951-0

20

Strati F Di Paola M Stefanini I Albanese D Rizzetto L Lionetti P et al . Age and gender affect the composition of fungal population of the human gastrointestinal tract. Front Microbiol. (2016) 7:1227. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01227

21

Caruso R Lo BC Núñez G . Host-microbiota interactions in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Immunol. (2020) 20:411–26. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0268-7

22

Deng Z Ma S Zhou H Zang A Fang Y Li T et al . Tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2 mediates C-type lectin receptor-induced activation of the kinase Syk and anti-fungal TH17 responses. Nat Immunol. (2015) 16:642–52. doi: 10.1038/ni.3155

23

Solomon KV Haitjema CH Henske JK Gilmore SP Borges-Rivera D Lipzen A et al . Early-branching gut fungi possess a large, comprehensive array of biomass-degrading enzymes. Science. (2016) 351:1192–5. doi: 10.1126/science.aad1431

24

Wu X Xia Y He F Zhu C Ren W . Intestinal mycobiota in health and diseases: from a disrupted equilibrium to clinical opportunities. Microbiome. (2021) 9:60. doi: 10.1186/s40168-021-01024-x

25

Franzosa EA Sirota-Madi A Avila-Pacheco J Fornelos N Haiser HJ Reinker S et al . Gut microbiome structure and metabolic activity in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Microbiol. (2019) 4:293–305. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0306-4

26

Mills RH Dulai PS Vázquez-Baeza Y Sauceda C Daniel N Gerner RR et al . Multi-omics analyses of the ulcerative colitis gut microbiome link Bacteroides vulgatus proteases with disease severity. Nat Microbiol. (2022) 7:262–76. doi: 10.1038/s41564-021-01050-3

27

Federici S Kviatcovsky D Valdés-Mas R Elinav E . Microbiome-phage interactions in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Microbiol Infect. (2023) 29:682–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2022.08.027

28

Podolsky DK . Inflammatory bowel disease (2). N Engl J Med. (1991) 325:1008–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110033251406

29

Rosen MJ Dhawan A Saeed SA . Inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. (2015) 169:1053–60. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1982

30

North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition Colitis Foundation of America Bousvaros A Antonioli DA Colletti RB Dubinsky MC et al . Differentiating ulcerative colitis from Crohn disease in children and young adults: report of a working group of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. (2007) 44:653–74. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31805563f3

31

Ng SC Shi HY Hamidi N Underwood FE Tang W Benchimol EI et al . Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. (2017) 390:2769–78. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32448-0

32

Kaplan GG . The global burden of IBD: from 2015 to 2025. Nat Rev Gastro Hepat. (2015) 12:720–7. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.150

33

Baumgart DC Sandborn WJ . Inflammatory bowel disease: clinical aspects and established and evolving therapies. Lancet (London England). (2007) 369:1641–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60751-X

34

Baumgart M Dogan B Rishniw M Weitzman G Bosworth B Yantiss R et al . Culture independent analysis of ileal mucosa reveals a selective increase in invasive Escherichia coli of novel phylogeny relative to depletion of Clostridiales in Crohn’s disease involving the ileum. ISME J. (2007) 1:403–18. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2007.52

35

Strober W Fuss I Mannon P . The fundamental basis of inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Invest. (2007) 117:514–21. doi: 10.1172/JCI30587

36

Zwolinska-Wcislo M Brzozowski T Budak A Kwiecien S Sliwowski Z Drozdowicz D et al . Effect of Candida colonization on human ulcerative colitis and the healing of inflammatory changes of the colon in the experimental model of colitis ulcerosa. J Physiol Pharmacol. (2009) 60:107–18.

37

Iliev ID Leonardi I . Fungal dysbiosis: immunity and interactions at mucosal barriers. Nat Rev Immunol. (2017) 17:635–46. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.55

38

Limon JJ Skalski JH Underhill DM . Commensal fungi in health and disease. Cell Host Microbe. (2017) 22:156–65. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.07.002

39

Pereira C Grácio D Teixeira JP Magro F . Oxidative stress and DNA damage: implications in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammation Bowel Dis. (2015) 21:2403–17. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000506

40

Bourgonje AR Feelisch M Faber KN Pasch A Dijkstra G van Goor H . Oxidative stress and redox-modulating therapeutics in inflammatory bowel disease. Trends Mol Med. (2020) 26:1034–46. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2020.06.006

41

Lim W-C Wang Y MacDonald JK Hanauer S . Aminosalicylates for induction of remission or response in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2016) 7:CD008870. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008870.pub2

42

Le Berre C Honap S Peyrin-Biroulet L . Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. (2023) 402:571–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00966-2

43

Winter JW Gaffney D Shapiro D Spooner RJ Marinaki AM Sanderson JD et al . Assessment of thiopurine methyltransferase enzyme activity is superior to genotype in predicting myelosuppression following azathioprine therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. (2007) 25:1069–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03301.x

44

Neurath MF . Current and emerging therapeutic targets for IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2017) 14:269–78. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.208

45

Kim K-U Kim J Kim W-H Min H Choi CH . Treatments of inflammatory bowel disease toward personalized medicine. Arch Pharm Res. (2021) 44:293–309. doi: 10.1007/s12272-021-01318-6

46

Fang X Vázquez-Baeza Y Elijah E Vargas F Ackermann G Humphrey G et al . Gastrointestinal surgery for inflammatory bowel disease persistently lowers microbiome and metabolome diversity. Inflammation Bowel Dis. (2021) 27:603–16. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izaa262

47

Ng SC Bernstein CN Vatn MH Lakatos PL Loftus EV Tysk C et al . Epidemiology and Natural History Task Force of the International Organization of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IOIBD). Geographical variability and environmental risk factors in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. (2013) 62:630–49. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303661

48

Kaplan GG Ng SC . Understanding and preventing the global increase of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. (2017) 152:313–321.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.020

49

Sanmarco LM Chao C-C Wang Y-C Kenison JE Li Z Rone JM et al . Identification of environmental factors that promote intestinal inflammation. Nature. (2022) 611:801–9. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05308-6

50

Khalili H Chan SSM Lochhead P Ananthakrishnan AN Hart AR Chan AT . The role of diet in the aetiopathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2018) 15:525–35. doi: 10.1038/s41575-018-0022-9

51

Dhaliwal J Tuna M Shah BR Murthy S Herrett E Griffiths AM et al . Incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in south Asian and Chinese people: A population-based cohort study from Ontario, Canada. Clin Epidemiol. (2021) 13:1109–18. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S336517

52

Kumbhari A Cheng TNH Ananthakrishnan AN Kochar B Burke KE Shannon K et al . Discovery of disease-adapted bacterial lineages in inflammatory bowel diseases. Cell Host Microbe. (2024) 32:1147–1162.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2024.05.022

53

Mukherjee PK Sendid B Hoarau G Colombel J-F Poulain D Ghannoum MA . Mycobiota in gastrointestinal diseases. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2015) 12:77–87. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2014.188

54

Sokol H Leducq V Aschard H Pham H-P Jegou S Landman C et al . Fungal microbiota dysbiosis in IBD. Gut. (2017) 66:1039–48. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310746

55

Zhang L Zhan H Xu W Yan S Ng SC . The role of gut mycobiome in health and diseases. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. (2021) 14:17562848211047130. doi: 10.1177/17562848211047130

56

Imai T Inoue R Kawada Y Morita Y Inatomi O Nishida A et al . Characterization of fungal dysbiosis in Japanese patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol. (2019) 54:149–59. doi: 10.1007/s00535-018-1530-7

57

Panpetch W Hiengrach P Nilgate S Tumwasorn S Somboonna N Wilantho A et al . Additional Candida albicans administration enhances the severity of dextran sulfate solution induced colitis mouse model through leaky gut-enhanced systemic inflammation and gut-dysbiosis but attenuated by Lactobacillus rhamnosus L34. Gut Microbes. (2020) 11:465–80. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2019.1662712

58

Zhong M Xiong Y Zhao J Gao Z Ma J Wu Z et al . Candida albicans disorder is associated with gastric carcinogenesis. Theranostics. (2021) 11:4945–56. doi: 10.7150/thno.55209

59

El Mouzan M Wang F Al Mofarreh M Menon R Al Barrag A Korolev KS et al . Fungal microbiota profile in newly diagnosed treatment-naïve children with Crohn’s disease. J Crohn’s Colitis. (2017) 11:586–92. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw197

60

Katsipoulaki M Stappers MHT Malavia-Jones D Brunke S Hube B Gow NAR . Candida albicans and Candida glabrata: global priority pathogens. Microbiol Mol Biol reviews: MMBR. (2024) 88:e0002123. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.00021-23

61

Hoarau G Mukherjee PK Gower-Rousseau C Hager C Chandra J Retuerto MA et al . Bacteriome and mycobiome interactions underscore microbial dysbiosis in familial Crohn’s disease. mBio. (2016) 7:e01250–16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01250-16

62

Liguori G Lamas B Richard ML Brandi G da Costa G Hoffmann TW et al . Fungal dysbiosis in mucosa-associated microbiota of Crohn’s disease patients. J Crohn’s Colitis. (2016) 10:296–305. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv209

63

Jain U Ver Heul AM Xiong S Gregory MH Demers EG Kern JT et al . Debaryomyces is enriched in Crohn’s disease intestinal tissue and impairs healing in mice. Sci (New York NY). (2021) 371:1154–9. doi: 10.1126/science.abd0919

64

Paone P Cani PD . Mucus barrier, mucins and gut microbiota: the expected slimy partners? Gut. (2020) 69:2232–43. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322260

65

Upperman JS Potoka DA Zhang X-R Wong K Zamora R Ford HR . Mechanism of intestinal-derived fungal sepsis by gliotoxin, a fungal metabolite. J Pediatr Surg. (2003) 38:966–70. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(03)00135-0

66

Chikina AS Nadalin F Maurin M San-Roman M Thomas-Bonafos T Li XV et al . Macrophages maintain epithelium integrity by limiting fungal product absorption. Cell. (2020) 183:411–428.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.048

67

Bertling A Niemann S Uekötter A Fegeler W Lass-Flörl C von Eiff C et al . Candida albicans and its metabolite gliotoxin inhibit platelet function via interaction with thiols. Thromb Haemost. (2010) 104:270–8. doi: 10.1160/TH09-11-0769

68

Zhai B Wozniak KL Masso-Silva J Upadhyay S Hole C Rivera A et al . Development of protective inflammation and cell-mediated immunity against Cryptococcus neoformans after exposure to hyphal mutants. mBio. (2015) 6:e01433–01415. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01433-15

69

Heung LJ . Innate immune responses to cryptococcus. J Fungi (Basel). (2017) 3:35. doi: 10.3390/jof3030035

70

Arunachalam D Ramanathan SM Menon A Madhav L Ramaswamy G Namperumalsamy VP et al . Expression of immune response genes in human corneal epithelial cells interacting with Aspergillus flavus conidia. BMC Genomics. (2022) 23:5. doi: 10.1186/s12864-021-08218-5

71

Pellon A Sadeghi Nasab SD Moyes DL . New Insights in Candida albicans Innate Immunity at the Mucosa: Toxins, Epithelium, Metabolism, and Beyond. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. (2020) 10:81. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00081

72

Wang L Zhang K Zeng Y Luo Y Peng J Zhang J et al . Gut mycobiome and metabolic diseases: The known, the unknown, and the future. Pharmacol Res. (2023) 193:106807. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2023.106807

73

Viola MF Boeckxstaens G . Niche-specific functional heterogeneity of intestinal resident macrophages. Gut. (2021) 70:1383–95. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323121

74

Speakman EA Dambuza IM Salazar F Brown GD . T cell antifungal immunity and the role of C-type lectin receptors. Trends Immunol. (2020) 41:61–76. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2019.11.007

75

Thompson A Davies LC Liao C-T da Fonseca DM Griffiths JS Andrews R et al . The protective effect of inflammatory monocytes during systemic C. albicans infection is dependent on collaboration between C-type lectin-like receptors. PloS Pathog. (2019) 15:e1007850. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007850

76

Takeuchi O Akira S . Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell. (2010) 140:805–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.022

77

Gross O Gewies A Finger K Schäfer M Sparwasser T Peschel C et al . Card9 controls a non-TLR signalling pathway for innate anti-fungal immunity. Nature. (2006) 442:651–6. doi: 10.1038/nature04926

78

Dang EV Lei S Radkov A Volk RF Zaro BW Madhani HD . Secreted fungal virulence effector triggers allergic inflammation via TLR4. Nature. (2022) 608:161–7. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05005-4

79

Pinzan CF Valero C de Castro PA da Silva JL Earle K Liu H et al . Aspergillus fumigatus conidial surface-associated proteome reveals factors for fungal evasion and host immunity modulation. Nat Microbiol. (2024) 9:2710–26. doi: 10.1038/s41564-024-01782-y

80

Strasser D Neumann K Bergmann H Marakalala MJ Guler R Rojowska A et al . Syk kinase-coupled C-type lectin receptors engage protein kinase C-δ to elicit Card9 adaptor-mediated innate immunity. Immunity. (2012) 36:32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.015

81

Garcia-Rubio R de Oliveira HC Rivera J Trevijano-Contador N . The fungal cell wall: candida, cryptococcus, and aspergillus species. Front Microbiol. (2019) 10:2993. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02993

82

Backert I Koralov SB Wirtz S Kitowski V Billmeier U Martini E et al . STAT3 activation in Th17 and Th22 cells controls IL-22-mediated epithelial host defense during infectious colitis. J Immunol (Baltimore Md: 1950). (2014) 193:3779–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303076

83

Bojang E Ghuman H Kumwenda P Hall RA . Immune sensing of candida albicans. J Fungi (Basel Switzerland). (2021) 7:119. doi: 10.3390/jof7020119

84

Dillon S Agrawal S Banerjee K Letterio J Denning TL Oswald-Richter K et al . Yeast zymosan, a stimulus for TLR2 and dectin-1, induces regulatory antigen-presenting cells and immunological tolerance. J Clin Invest. (2006) 116:916–28. doi: 10.1172/JCI27203

85

Lee C Verma R Byun S Jeun E-J Kim G-C Lee S et al . Structural specificities of cell surface β-glucan polysaccharides determine commensal yeast mediated immuno-modulatory activities. Nat Commun. (2021) 12:3611. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-23929-9

86

Sparber F De Gregorio C Steckholzer S Ferreira FM Dolowschiak T Ruchti F et al . The skin commensal yeast malassezia triggers a type 17 response that coordinates anti-fungal immunity and exacerbates skin inflammation. Cell Host Microbe. (2019) 25:389–403.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.02.002

87

Wang Y Spatz M Da Costa G Michaudel C Lapiere A Danne C et al . Deletion of both Dectin-1 and Dectin-2 affects the bacterial but not fungal gut microbiota and susceptibility to colitis in mice. Microbiome. (2022) 10:91. doi: 10.1186/s40168-022-01273-4

88

Swidergall M Khalaji M Solis NV Moyes DL Drummond RA Hube B et al . Candidalysin is required for neutrophil recruitment and virulence during systemic candida albicans infection. J Infect Dis. (2019) 220:1477–88. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz322

89

Moyes DL Runglall M Murciano C Shen C Nayar D Thavaraj S et al . A biphasic innate immune MAPK response discriminates between the yeast and hyphal forms of Candida albicans in epithelial cells. Cell Host Microbe. (2010) 8:225–35. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.08.002

90

Ponde NO Lortal L Tsavou A Hepworth OW Wickramasinghe DN Ho J et al . Receptor-kinase EGFR-MAPK adaptor proteins mediate the epithelial response to Candida albicans via the cytolytic peptide toxin, candidalysin. J Biol Chem. (2022) 298:102419. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2022.102419

91

Verma AH Richardson JP Zhou C Coleman BM Moyes DL Ho J et al . Oral epithelial cells orchestrate innate type 17 responses to Candida albicans through the virulence factor candidalysin. Sci Immunol. (2017) 2:eaam8834. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aam8834

92

Deatherage BL Cookson BT . Membrane vesicle release in bacteria, eukaryotes, and archaea: a conserved yet underappreciated aspect of microbial life. Infect Immun. (2012) 80:1948–57. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06014-11

93

Rodrigues ML Nosanchuk JD Schrank A Vainstein MH Casadevall A Nimrichter L . Vesicular transport systems in fungi. Future Microbiol. (2011) 6:1371–81. doi: 10.2217/fmb.11.112

94

Rizzo J Chaze T Miranda K Roberson RW Gorgette O Nimrichter L et al . Characterization of extracellular vesicles produced by aspergillus fumigatus protoplasts. mSphere. (2020) 5:e00476–20. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00476-20

95

Rodrigues ML Nimrichter L Oliveira DL Frases S Miranda K Zaragoza O et al . Vesicular polysaccharide export in Cryptococcus neoformans is a eukaryotic solution to the problem of fungal trans-cell wall transport. Eukaryot Cell. (2007) 6:48–59. doi: 10.1128/EC.00318-06

96

Eisenman HC Frases S Nicola AM Rodrigues ML Casadevall A . Vesicle-associated melanization in Cryptococcus neoformans. Microbiol (Reading England). (2009) 155:3860–7. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.032854-0

97

Vallejo MC Matsuo AL Ganiko L Medeiros LCS Miranda K Silva LS et al . The pathogenic fungus Paracoccidioides brasiliensis exports extracellular vesicles containing highly immunogenic α-Galactosyl epitopes. Eukaryot Cell. (2011) 10:343–51. doi: 10.1128/EC.00227-10

98

Vargas G Rocha JDB Oliveira DL Albuquerque PC Frases S Santos SS et al . Compositional and immunobiological analyses of extracellular vesicles released by C andida albicans: Extracellular vesicles from Candida albicans. Cell Microbiol. (2015) 17:389–407. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12374

99

Nimrichter L De Souza MM Del Poeta M Nosanchuk JD Joffe L Tavares PDM et al . Extracellular vesicle-associated transitory cell wall components and their impact on the interaction of fungi with host cells. Front Microbiol. (2016) 7:1034. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01034

100

Rayner S Bruhn S Vallhov H Andersson A Billmyre RB Scheynius A . Identification of small RNAs in extracellular vesicles from the commensal yeast Malassezia sympodialis. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:39742. doi: 10.1038/srep39742

101

Bielska E Sisquella MA Aldeieg M Birch C O’Donoghue EJ May RC . Pathogen-derived extracellular vesicles mediate virulence in the fatal human pathogen Cryptococcus gattii. Nat Commun. (2018) 9:1556. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03991-6

102

Ikeda MAK de Almeida JRF Jannuzzi GP Cronemberger-Andrade A Torrecilhas ACT Moretti NS et al . Extracellular vesicles from sporothrix brasiliensis are an important virulence factor that induce an increase in fungal burden in experimental sporotrichosis. Front Microbiol. (2018) 9:2286. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02286

103

Piffer AC Kuczera D Rodrigues ML Nimrichter L . The paradoxical and still obscure properties of fungal extracellular vesicles. Mol Immunol. (2021) 135:137–46. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2021.04.009

104

Costa JH Bazioli JM Barbosa LD Dos Santos Júnior PLT Reis FCG Klimeck T et al . Phytotoxic tryptoquialanines produced in vivo by penicillium digitatum are exported in extracellular vesicles. mBio. (2021) 12:e03393–20. doi: 10.1128/mBio.03393-20

105

Zhao K Bleackley M Chisanga D Gangoda L Fonseka P Liem M et al . Extracellular vesicles secreted by Saccharomyces cerevisiae are involved in cell wall remodelling. Commun Biol. (2019) 2:305. doi: 10.1038/s42003-019-0538-8

106

Wei Y Wang Z Liu Y Liao B Zong Y Shi Y et al . Extracellular vesicles of Candida albicans regulate its own growth through the L-arginine/nitric oxide pathway. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. (2023) 107:355–67. doi: 10.1007/s00253-022-12300-7

107

Brown L Wolf JM Prados-Rosales R Casadevall A . Through the wall: extracellular vesicles in Gram-positive bacteria, mycobacteria and fungi. Nat Rev Microbiol. (2015) 13:620–30. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3480

108

Honorato L De Araujo JFD Ellis CC Piffer AC Pereira Y Frases S et al . Extracellular vesicles regulate biofilm formation and yeast-to-hypha differentiation in candida albicans. mBio. (2022) 13:e00301–22. doi: 10.1128/mbio.00301-22

109

Lai Y Jiang B Hou F Huang X Ling B Lu H et al . The emerging role of extracellular vesicles in fungi: a double-edged sword. Front Microbiol. (2023) 14:1216895. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1216895

110

Campos RMS Jannuzzi GP Ikeda MAK De Almeida SR Ferreira KS . Extracellular vesicles from sporothrix brasiliensis yeast cells increases fungicidal activity in macrophages. Mycopathologia. (2021) 186:807–18. doi: 10.1007/s11046-021-00585-7

111

Gandhi J Naik MN Mishra DK Joseph J . Proteomic profiling of aspergillus flavus endophthalmitis derived extracellular vesicles in an in-vivo murine model. Med Mycol. (2022) 60:myac064. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myac064

112

Zamith-Miranda D Heyman HM Couvillion SP Cordero RJB Rodrigues ML Nimrichter L et al . Comparative Molecular and Immunoregulatory Analysis of Extracellular Vesicles from Candida albicans and Candida auris. mSystems. (2021) 6:e0082221. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00822-21

113

Chan W Chow FW-N Tsang C-C Liu X Yao W Chan TT-Y et al . Induction of amphotericin B resistance in susceptible Candida auris by extracellular vesicles. Emerg Microbes Infect. (2022) 11:1900–9. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2022.2098058

114

Huang S-H Wu C-H Chang YC Kwon-Chung KJ Brown RJ Jong A . Cryptococcus neoformans-derived microvesicles enhance the pathogenesis of fungal brain infection. PloS One. (2012) 7:e48570. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048570

115

Bitencourt TA Hatanaka O Pessoni AM Freitas MS Trentin G Santos P et al . Fungal extracellular vesicles are involved in intraspecies intracellular communication. mBio. (2022) 13:e0327221. doi: 10.1128/mbio.03272-21

116

Pérez JC . The interplay between gut bacteria and the yeast Candida albicans. Gut Microbes. (2021) 13:1979877. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2021.1979877

117

Peleg AY Hogan DA Mylonakis E . Medically important bacterial–fungal interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol. (2010) 8:340–9. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2313

118

Fan D Coughlin LA Neubauer MM Kim J Kim MS Zhan X et al . Activation of HIF-1α and LL-37 by commensal bacteria inhibits Candida albicans colonization. Nat Med. (2015) 21:808–14. doi: 10.1038/nm.3871

119

Xu X-L Lee RTH Fang H-M Wang Y-M Li R Zou H et al . Bacterial peptidoglycan triggers Candida albicans hyphal growth by directly activating the adenylyl cyclase Cyr1p. Cell Host Microbe. (2008) 4:28–39. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.05.014

120

Tan CT Xu X Qiao Y Wang Y . A peptidoglycan storm caused by β-lactam antibiotic’s action on host microbiota drives Candida albicans infection. Nat Commun. (2021) 12:2560. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22845-2

121

Rollenhagen C Agyeman H Eszterhas S Lee SA . Candida albicans END3 mediates endocytosis and has subsequent roles in cell wall integrity, morphological switching, and tissue invasion. Microbiol Spectr. (2022) 10:e0188021. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.01880-21

122

Cabral DJ Penumutchu S Norris C Morones-Ramirez JR Belenky P . Microbial competition between Escherichia coli and Candida albicans reveals a soluble fungicidal factor. Microbial Cell. (2018) 5:249–55. doi: 10.15698/mic2018.05.631

123

Trunk K Peltier J Liu Y-C Dill BD Walker L Gow NAR et al . The type VI secretion system deploys antifungal effectors against microbial competitors. Nat Microbiol. (2018) 3:920–31. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0191-x

124

Filyk HA Osborne LC . The multibiome: the intestinal ecosystem’s influence on immune homeostasis, health, and disease. EBioMedicine. (2016) 13:46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.10.007

125

Brown AO Graham CE Cruz MR Singh KV Murray BE Lorenz MC et al . Antifungal activity of the enterococcus faecalis peptide entV requires protease cleavage and disulfide bond formation. mBio. (2019) 10:e01334–19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01334-19

126

Zeise KD Woods RJ Huffnagle GB . Interplay between candida albicans and lactic acid bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract: impact on colonization resistance, microbial carriage, opportunistic infection, and host immunity. Clin Microbiol Rev. (2021) 34:e0032320. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00323-20

127

Jabra-Rizk MA Meiller TF James CE Shirtliff ME . Effect of farnesol on Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation and antimicrobial susceptibility. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. (2006) 50:1463–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.4.1463-1469.2006

128

Yapıcı M Gürsu BY Dağ İ . In vitro antibiofilm efficacy of farnesol against Candida species. Int Microbiol. (2021) 24:251–62. doi: 10.1007/s10123-021-00162-4

129

Cuskin F Lowe EC Temple MJ Zhu Y Cameron E Pudlo NA et al . Human gut Bacteroidetes can utilize yeast mannan through a selfish mechanism. Nature. (2015) 517:165–9. doi: 10.1038/nature13995

130

Markey L Shaban L Green ER Lemon KP Mecsas J Kumamoto CA . Pre-colonization with the commensal fungus Candida albicans reduces murine susceptibility to Clostridium difficile infection. Gut Microbes. (2018) 9:497–509. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2018.1465158

131

Roy S Dhaneshwar S . Role of prebiotics, probiotics, and synbiotics in management of inflammatory bowel disease: Current perspectives. World J Gastroenterol. (2023) 29:2078–100. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v29.i14.2078

132

Britton RA Hoffmann DE Khoruts A . Probiotics and the microbiome-how can we help patients make sense of probiotics? Gastroenterology. (2021) 160:614–23. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.11.047

133

Gionchetti P Rizzello F Venturi A Brigidi P Matteuzzi D Bazzocchi G et al . Oral bacteriotherapy as maintenance treatment in patients with chronic pouchitis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. (2000) 119:305–9. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.9370

134

Czerucka D Piche T Rampal P . Review article: yeast as probiotics – Saccharomyces boulardii. Aliment Pharm Ther. (2007) 26:767–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03442.x

135