- 1Department of Orthopedics, The Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University, Luzhou, China

- 2Department of Orthopedics, The Second People’s Hospital of Neijiang, Neijiang, China

- 3Department of Neurology, The Second People’s Hospital of Neijiang, Neijiang, China

Diffuse gliomas remain lethal primary brain tumors. Immune-checkpoint inhibitors have not delivered durable benefit for most patients, reflecting myeloid-dominant immunosuppression and spatially organized immune exclusion. In this mini-review we summarize ligand–receptor multi-omics—single-cell RNA/CITE-seq, single-cell chromatin accessibility, and spatial proteo-transcriptomics—that resolve microglia- and monocyte-derived TAM programs and malignant state continua, and we appraise translational opportunities spanning TAM reprogramming (CSF1–CSF1R), perivascular SPP1–CD44 disruption, and innate–adaptive combinations targeting CD47–SIRPα, CD39–CD73, and PD-1/PD-L1. We also discuss challenges—including ontogeny-aware state definitions, heteromer-aware databases, chromatin gating of receivers (requiring accessible regulatory DNA for the receptor and its program), spatial registration, and limited assay standardization—that temper implementation. By integrating myeloid-informed readouts (SPP1–TAM burden, CD39–CD73 proximity, HMOX1+ IL-10 niches, serum IL-8), emerging strategies aim to restore antigen presentation, enable effector ingress, and remodel vascular–stromal interfaces. Our synthesis provides an appraisal of reproducible communication architectures in glioma and outlines pragmatic reporting standards and trial-ready pharmacodynamic endpoints for myeloid-informed precision immuno-oncology. We hope these insights will assist researchers and clinicians as they design multi-omics pipelines and interventions to convert suppressive ecosystems into responsive ones.

1 Introduction

Diffuse gliomas develop in an immune microenvironment dominated by tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) from brain-resident microglia and infiltrating monocytes; these lineages regulate tumor growth, therapy resistance, and outcome through context-dependent interactions with malignant, stromal, and lymphoid compartments (1–4). Single-cell atlases and CITE-seq in human and murine glioblastoma resolve microglia- versus monocyte-derived TAM programs with conserved lipid-handling, hypoxia-adaptation, and antigen-presentation modules, and reveal stage-specific shifts in lineage composition at recurrence, underscoring the central role of myeloid ecology in progression (5–7). Spatially resolved profiling shows that perivascular, invasive-front, and necrotic niches are enriched for discrete TAM states and immunoregulatory interfaces, linking myeloid topology to effector-cell exclusion and pharmacodynamic heterogeneity (8–10). These data establish myeloid circuits as core—rather than ancillary—determinants of immune failure in glioma.

Mechanistically, glioma–myeloid crosstalk is organized by chemokine/growth-factor axes (recruitment, survival, polarization) and immune checkpoints that constrain phagocytosis and T-cell function. CSF1–CSF1R signaling sustains TAM viability and skews polarization; in proneural glioma models, CSF1R blockade remodels rather than depletes TAMs and attenuates tumor growth, highlighting circuitry that can be pharmacologically reprogrammed (11–13). The CCL2/monocyte-chemoattractant (MCP) family drives CCR2+ monocyte recruitment; when MCPs are perturbed, trafficking is rerouted with CXCL2-dependent neutrophil influx, underscoring chemokine redundancy/plasticity; therefore LR maps should be interpreted as state- and niche-contingent and recomputed under perturbation with compensation-aware statistics (e.g., tracking gain of CXCL2–CXCR2 neutrophil edges when MCPs are blocked) (14–16). Brain-resident microglia maintain CX3CR1-linked tissue residency programs yet acquire disease-associated states in glioma, whereas infiltrating macrophages dominate hypoxic cores and necrotic zones, consistent with spatial specialization of ligand–receptor activity (17–20). Beyond recruitment and maintenance, specific contact and soluble interactions impose immune suppression and invasion: SPP1–CD44 signaling is upregulated in glioblastoma and integrates with STAT3/CEBP-β-driven programs to promote immunoregulatory TAM phenotypes and tumor aggressiveness (21–23); TGF-β signaling further enforces antigen-presentation deficits and exclusionary stromal remodeling; the CD47–SIRPα axis inhibits macrophage phagocytosis; and PD-L1–PD-1 engagement dampens T-cell effector function within TAM-dense niches.

Resolving this crosstalk leverages multi-omics. Single-cell RNA and CITE-seq define sender/receiver cell states; single-cell chromatin profiling adds cis-regulatory logic for myeloid polarization; and spatial proteogenomics/transcriptomics localize active interfaces in situ (24–26). Computational frameworks infer and prioritize ligand–receptor (LR) interactions from these data: CellPhoneDB implements a curated, multimeric LR repository with statistical enrichment tests; NicheNet links ligands to downstream gene programs to nominate functional signals; and CellChat models pathway-level communication using a mass-action formulation, enabling comparative analyses across patients, regions, and disease stages (27–29). Comparative benchmarking emphasizes that LR inference should be integrated with spatial context, adjacency-aware metrics (e.g., contact-graph proximity), and chromatin constraints to reduce false positives and to distinguish adjacency-driven signaling from mere co-expression, a requirement that is particularly acute in glioma where microglia and monocyte-derived macrophages co-localize yet differ in ontogeny, accessibility landscapes, and effector coupling (30–32).

In this review, we synthesize the ecology of glioma TAMs and delineate the ligand–receptor architecture that encodes immune evasion across single-cell, chromatin-accessibility, and spatial modalities, with the goal of establishing reproducible analytic standards and translational readouts for myeloid-informed intervention; the purpose of this article is to provide a rigorous, multi-omics framework for mapping TAM–tumor ligand–receptor crosstalk in glioma and specifying how these interactions mechanistically implement immune escape.

2 Single-cell and multi-omics map of TAM–tumor crosstalk in glioma

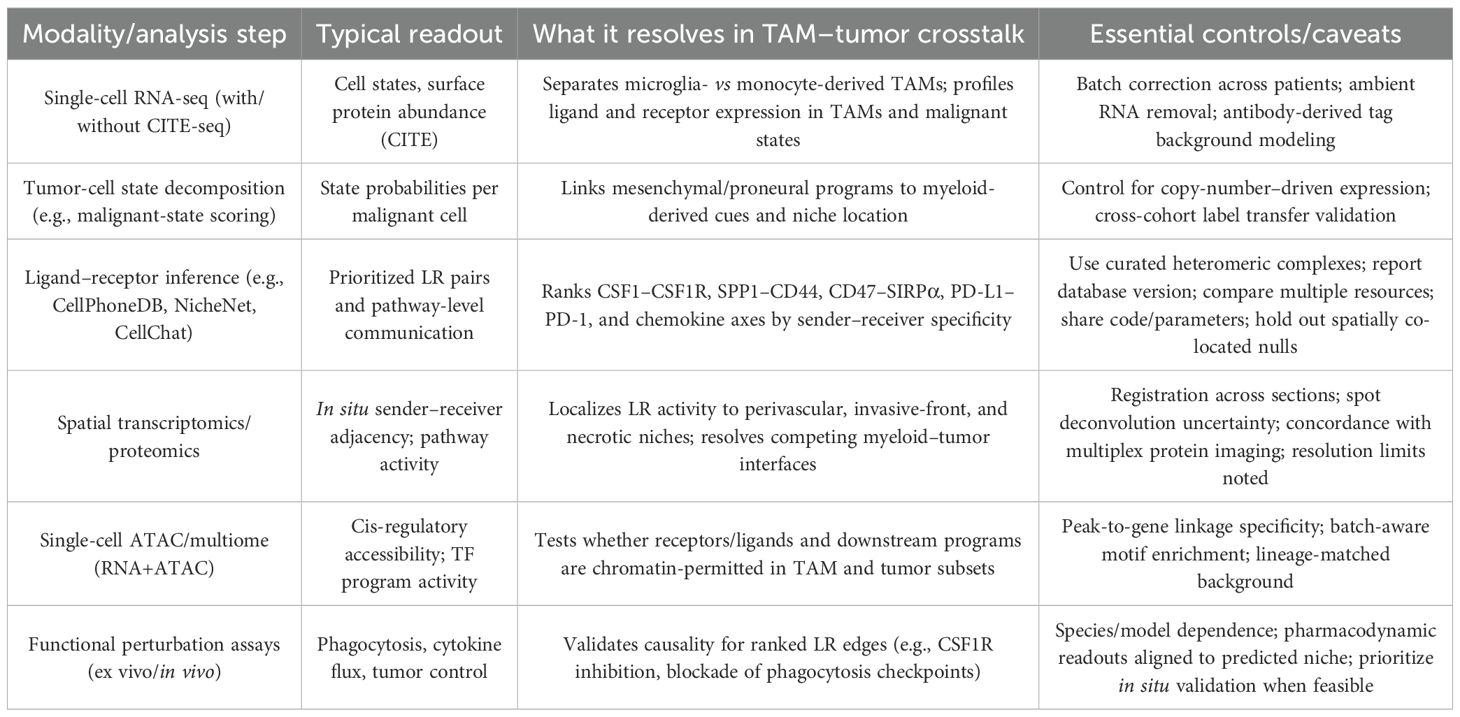

Single-cell atlases resolve TAMs into microglial and monocyte-derived lineages with distinct transcriptional programs and region-specific distributions across glioma. In human tumors, scRNA-seq distinguishes blood-derived macrophages—enriched for immunoregulatory cytokines and altered metabolic pathways—from microglial TAMs that preferentially populate tumor margins, establishing ontogeny as a principal axis of heterogeneity (33–35). Matched scRNA/CITE-seq in patients and mouse models recovers conserved lipid-handling and hypoxia-adaptation modules and delineates dendritic and monocyte/macrophage subsets that vary with disease stage, linking composition to progression (36–39). On the malignant side, glioblastoma cells span dynamic state continua (astrocyte-like, oligodendrocyte-progenitor-like, neural-progenitor-like, mesenchymal-like) that correlate with—and likely respond to—myeloid-derived cues (40, 41). Ligand–receptor inference consistently prioritizes axes that organize this crosstalk: CSF1–CSF1R signaling supports TAM survival and polarization and is pharmacologically reprogrammable in proneural GBM; notably, CSF1R blockade remodels rather than depletes TAMs in vivo (42, 43). A second, frequently recovered interface is SPP1 (osteopontin)–CD44, which is enriched at perivascular niches and couples macrophage programs to mesenchymal tumor traits and treatment resistance (44, 45). Integrating these layers with spatially resolved profiling demonstrates that perivascular corridors, invasive fronts, and necrotic cores harbor distinct TAM–tumor exchanges, refining cell-state co-localization into mechanistic, niche-specific signaling maps that explain immune exclusion and heterogeneous drug responses (46–49). Table 1 shows the principal single-cell and multi-omics modalities, their readouts, the specific questions they address in TAM–tumor communication, and essential controls.

Table 1. Core modalities for mapping TAM–tumor ligand–receptor crosstalk in glioma and the inferences each supports.

Multi-omics integration provides orthogonal evidence for specific immune-evasion circuits. Spatial proteo-genomics that overlays pathway proteins onto transcript-defined states shows that mesenchymal and proneural cores are layered with distinct TAM interfaces and that communication intensity varies across regions, resolving why bulk signatures underperform as biomarkers in GBM (50–52). Spatially organized Notch and hypoxia programs further partition tumor cores and rims, with accompanying shifts in myeloid partners, strengthening the case that LR predictions should be filtered by niche topology to avoid co-expression false positives (11, 53, 54). At the metabolic–innate checkpoint intersection, glioblastoma increases fatty-acid oxidation and upregulates CD47, creating phagocytosis-proof tumor cells; phagocytic checkpoints on TAMs can be overcome only when innate signals are combined with genotoxic or STING agonism, aligning LR maps with actionable dependencies (55, 56). Systematic benchmarking of communication tools indicates that database coverage and model assumptions materially change predicted edges—including sensitivity to database versioning, receptor isoforms, and spatial resolution—recommending consensus across complementary resources, parameter sharing, and pathway-aware statistics when prioritizing LR pairs for perturbation.

These single-cell, chromatin, and spatial layers converge on a reproducible architecture in which ontogeny-defined TAM programs and state-defined tumor programs engage through a limited set of crosstalk axes—CSF1/CSF1R for maintenance and polarization, SPP1–CD44 for mesenchymal reinforcement and perivascular conditioning, and CD47–SIRPα and PD-L1–PD-1 as dominant effector brakes—whose intensity and topology vary by niche.

3 Spatial ecosystems and circuit topology of immune evasion in glioma

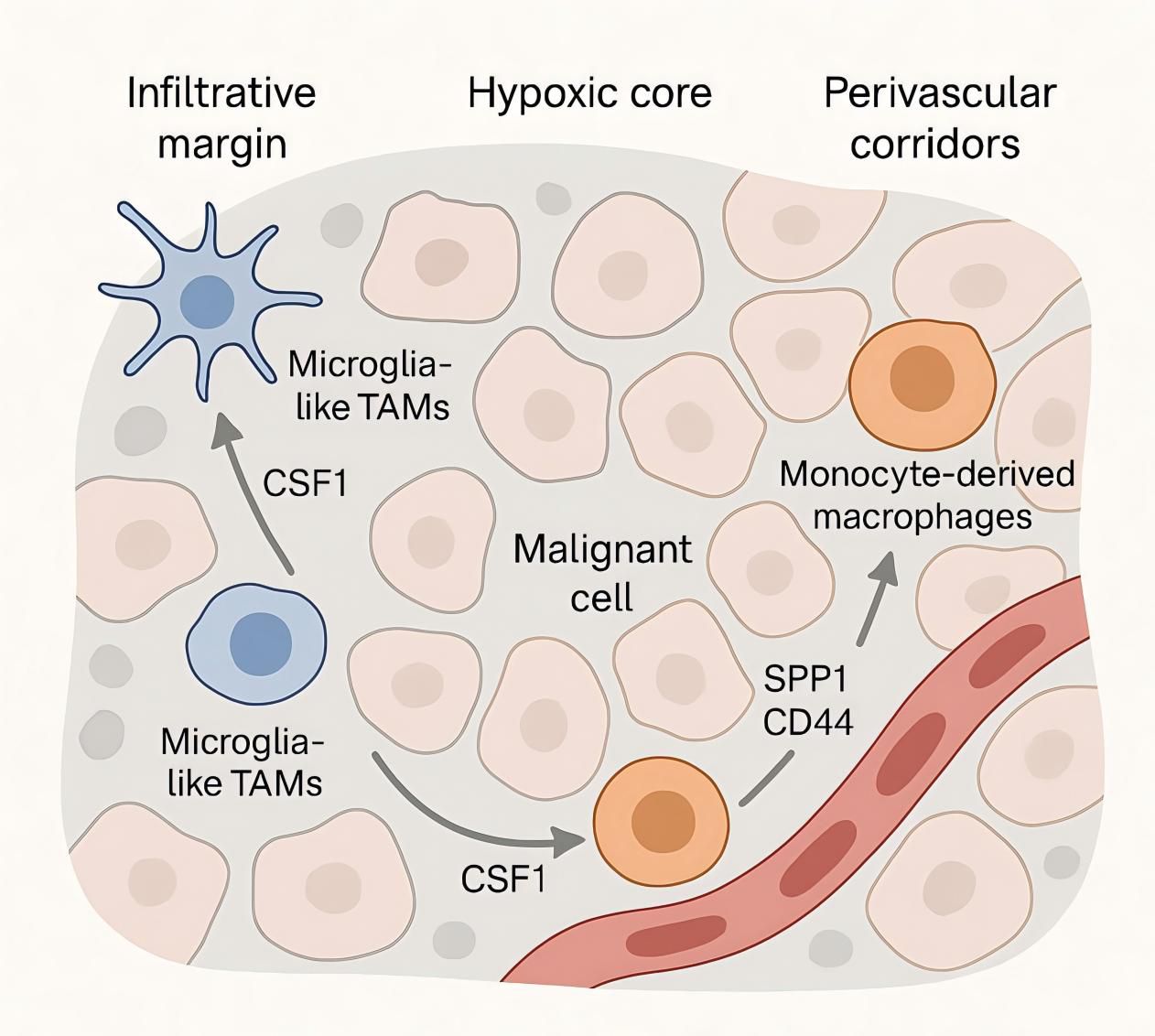

Spatially resolved maps in glioma demonstrate that immune evasion is encoded by niche-specific adjacency between ontogeny-defined TAM states and malignant programs. As shown in Figure 1, microglia-like TAMs preferentially accumulate at infiltrative margins, whereas monocyte-derived macrophages dominate hypoxic cores; multiplex imaging and spatial transcriptomics further resolve immune neighborhoods associated with outcome in glioblastoma, including survival-linked myeloperoxidase-positive macrophage subsets and variable lymphoid access at tumor borders (57–59). Perinecrotic regions show the strongest immunosuppressive signatures with dense myeloid content, while perivascular corridors exhibit distinct inflammatory and angiogenic signaling, indicating that spatial topology—not bulk abundance—governs checkpoint engagement and effector exclusion.

Figure 1. Spatial niches and signaling of tumor-associated macrophages in the glioma microenvironment—margins vs cores.

These ecosystems are organized by a limited set of ligand–receptor circuits whose activity depends on location and lineage. Single-cell atlases across species and disease stages define competition and specialization between microglia- and monocyte-derived TAMs, providing the sender–receiver context for niche-restricted signaling (60, 61). Within perivascular corridors, infiltrating monocyte-derived and border-associated/perivascular macrophages are the dominant SPP1 producers (microglia contribute less); SPP1—both secreted and matrix-bound (ECM-tethered)—engages CD44 on mesenchymal-shifted glioma cells and endothelial/pericyte compartments; CD44 isoform usage (CD44s with context-dependent CD44v6/v10) and integrin co-receptors (e.g., αvβ3/αvβ5) tune adhesion/angiogenic outputs that reinforce mesenchymal programs (62, 63). Hypoxic and mesenchymal zones are enriched for HMOX1+ myeloid cells that release IL-10 and drive spatially localized T-cell dysfunction through JAK/STAT-dependent programs, providing a cytokine circuit that couples TAM proximity to effector exhaustion (64, 65). A complementary metabolic checkpoint is topologically organized by CD39+ microglia adjacent to CD73+ tumor cells, producing adenosine-rich interfaces that suppress antitumor immunity; the strength of CD39–CD73 co-localization correlates with adverse clinical features, underscoring a spatially constrained purinergic pathway of immune escape.

These data support a circuit topology in which perivascular SPP1–CD44 and angiogenic signals consolidate mesenchymal programs and vascular remodeling; perinecrotic hubs concentrate IL-10–dominated myeloid signaling and adenosine metabolism; and border zones variably permit lymphoid ingress depending on TAM continuity at tumor–stroma interfaces (55, 66, 67). This model explains why co-expression overestimates communication: signaling requires chromatin-permitted receptors in adjacent receiver states within specific niches. It also nominates quantitative spatial readouts—macrophage–tumor interface length, CD39–CD73 proximity, and enrichment of IL-10–linked HMOX1+ myeloid neighborhoods—as mechanistic biomarkers to benchmark interventions that reprogram TAMs, disrupt perivascular SPP1–CD44, or attenuate purinergic and cytokine checkpoints in glioma.

4 Translational readouts and interventions: biomarkers and myeloid-directed therapeutics

Translational readouts should quantify myeloid–tumor LR activity and spatial deployment. Tissue biomarkers that index SPP1+ TAM programs and perivascular SPP1–CD44 signaling associate with mesenchymal traits and poor outcome in glioma and can be captured by RNA panels or multiplexed protein assays (40, 68, 69); spatial adjacency metrics such as CD39+ myeloid–CD73+ tumor proximity and enrichment of HMOX1+ IL-10–secreting myeloid neighborhoods provide orthogonal evidence of immunosuppressive niches and should be prospectively standardized as pharmacodynamic endpoints (39, 70, 71). Circulating readouts that reflect myeloid trafficking complement tissue metrics; in glioma models, IL-8 neutralization enhances the efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade, supporting baseline and on-treatment IL-8 as a negative biomarker and as a targetable axis (16, 19, 72). A composite panel that integrates SPP1–TAM burden, CD39–CD73 spatial proximity, HMOX1/IL-10 myeloid niches, and IL-8 levels can report on the intensity and topology of myeloid circuits that gate effector function and should be embedded in trial schemas evaluating myeloid-directed agents.

Therapeutic strategies that directly modulate these circuits are feasible and should be layered onto contemporary glioma backbones with predefined mechanistic endpoints. CSF1R blockade remodels, rather than depletes, TAMs in proneural glioma models and constrains tumor growth, establishing a paradigm of pharmacologic reprogramming of maintenance signals; subsequent studies corroborate antitumor effects of CSF1R inhibition and highlight context dependence that argues for biomarker-guided selection (15, 73). Myeloid checkpoint inhibition at the phagocytosis axis is mechanistically justified: the CD47–SIRPα pathway suppresses macrophage effector function across solid tumors, yet in glioma, CD47 blockade shows limited activity as monotherapy and demonstrates improved phagocytic and antitumor effects when combined with genotoxic stressors, supporting rational combinations with standard therapy or opsonizing antibodies. Targeting macrophage-intrinsic signaling can convert suppressive programs: PI3Kγ functions as a switch enforcing immunosuppressive transcriptional states in myeloid cells; its inhibition restores inflammatory outputs and synergizes with PD-1 blockade in preclinical models, nominating PI3Kγ inhibitors for evaluation in glioma with embedded myeloid pharmacodynamics (57, 74, 75). Purinergic signaling is a spatially organized checkpoint: co-localization of CD73+ tumor cells with CD39+ microglia amplifies extracellular adenosine that suppresses T cells via high-affinity A2A receptors and conditions myeloid cells via lower-affinity A2B; hypoxia/HIF-1α upregulates CD73, strengthening this axis—rationalizing anti-CD73 or adenosine-receptor antagonists with spatial biomarkers as inclusion/response criteria. Trial designs should incorporate on-treatment reduction of SPP1–TAM signatures, attenuation of CD39–CD73 proximity, depletion or reprogramming of HMOX1+ IL-10 niches, and restoration of effector cell access as primary pharmacodynamic endpoints to attribute benefit to myeloid modulation.

5 Outlook and standards for integrative ligand–receptor multi-omics in glioma

Integrative ligand–receptor (LR) profiling in glioma should progress from descriptive atlases to standardized, decision-oriented pipelines that co-register single-cell RNA (± CITE-seq), single-cell chromatin accessibility (scATAC or multiome), and spatial readouts with harmonized metadata, tissue-region annotation, and predefined endpoints (11, 76, 77). A practical state dictionary for sender/receiver modeling is justified by existing atlases and should minimally include microglia-derived and monocyte-derived TAM programs, mesenchymal/proneural malignant states, and region-specific endothelial and stromal compartments (78–81); these choices are supported by foundational glioblastoma single-cell studies resolving malignant state continua and myeloid ontogeny, and by datasets that map myeloid subset diversity and spatial bias in experimental and human gliomas.

In silico LR inference should use curated, heteromer-aware resources—databases that encode multi-subunit stoichiometry (e.g., α/β chains) and isoform-specific binding (e.g., CD44 variants)—with transparent statistics, and should favor consensus across complementary tools. CellPhoneDB tests enrichment of multimeric complexes (enrichment paradigm), NicheNet scores ligands by regulatory potential on target programs (regulatory-potential paradigm), and CellChat estimates pathway-level mass-action flow (mass-action paradigm); when outputs disagree, treat two-of-three concordance (plus spatial/chromatin support) as high confidence and reserve tool-unique calls for exploratory validation. Cross-tool agreement should be explicitly reported, and permutation-based nulls should reflect tissue structure (e.g., region-stratified or spatially permuted cells) rather than only global label shuffling (4, 82, 83). Edges should be ‘gated’ by scATAC/multiome evidence: (i) receiver-side promoter/enhancer accessibility with peak-to-gene linkage for the receptor (e.g., co-accessibility/correlation above a preset threshold), (ii) activity of downstream TF motifs (e.g., chromVAR/GSVA deviation > ~1–2 SD), and (iii) sender-side accessibility for the ligand; applying these filters materially reduces co-expression false positives, with accepted edges summarized at the donor–receiver–pathway level.

Spatial registration is required to distinguish adjacency-dependent signaling from mere co-abundance. Spatial transcriptomics and multiplexed imaging should localize LR activity to perivascular, invasive-front, and perinecrotic ecosystems and quantify: (a) LR intensity—unitless, per donor–receiver pair mass-action–style scores (normalized ligand × receptor per cell); (b) communication burden—we define this as per-niche or patient-level aggregates (sum/mean of accepted edges normalized by sender/receiver counts); and (c) proximity scores—adjacency-aware metrics (interface length, inverse distance or co-localization indices on a contact graph) computed within regions (55, 61, 84). In glioma, perivascular SPP1–CD44 signaling and mesenchymal programs, and the purinergic CD39–CD73 interface between microglia and tumor cells, are recurrently enriched in defined niches; spatial frameworks that quantify these arrangements have been associated with prognostic and biological stratification and therefore constitute suitable benchmarks for LR pipelines.

Method reporting should include pre-analytical variables (fixation, dissociation, steroid exposure), an explicit region map (core, rim, invasive margin, perivascular, perinecrotic), doublet and ambient-RNA handling, batch correction strategy, and cross-cohort label transfer performance. Minimal LR-specific reporting should enumerate database versions, multimer handling, null model specification, per-edge effect sizes and false-discovery rates, and the criteria for chromatin gating. Spatial sections should include segmentation and registration procedures, spot deconvolution uncertainty, and cross-modality concordance (85–87). Where possible, open-source code and parameter files should be deposited with derived matrices so that LR calls can be recomputed without raw data access.

Functional validation should be embedded early using positive-control axes that are established in glioma and that exercise distinct mechanistic classes. CSF1–CSF1R can benchmark maintenance/polarization signals; SPP1–CD44 can benchmark perivascular mesenchymal reinforcement; and CD39–CD73 can benchmark metabolic checkpoint topology (56, 88, 89). Small-scale perturbations (ex vivo receptor blockade, phagocytosis/cytokine readouts) should be aligned to sender/receiver states predicted by the pipeline and, for spatial claims, should preferentially sample regions where adjacency scores are highest.

Clinical translation should move from single markers to composite communication scores with spatial context. A pragmatic panel for early-phase studies would combine: (i) a communication burden for perivascular SPP1–CD44 and a mesenchymal-state readout in tumor cells; (ii) a spatial purinergic-axis metric quantifying CD39+ microglia–CD73+ tumor proximity; and (iii) circulating or tissue chemokine indices that track myeloid trafficking. Practical hurdles include tissue accessibility for region-resolved assays, assay standardization across platforms, and turnaround times compatible with clinical decision-making. Prospective designs should prespecify pharmacodynamic success as reduction of targeted communication scores with concomitant restoration of effector access, and should stratify by IDH status and steroid exposure to minimize confounding.

Benchmarking should use multi-institutional samples with repeated sections from the same tumor to measure technical and biological variance, and should include orthogonal perivascular-interactome or spatial-omics datasets as “hold-out” validation. Published glioma spatial studies already provide suitable templates for region-matched validation and for evaluating whether LR calls generalize across platforms and centers; future releases should prioritize needle-biopsy–compatible protocols to facilitate clinical implementation.

Author contributions

DZ: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Resources, Data curation, Conceptualization, Visualization, Validation. YM: Validation, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Visualization. DF: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Conceptualization, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Pombo Antunes AR, Scheyltjens I, Lodi F, Messiaen J, Antoranz A, Duerinck J, et al. Single-cell profiling of myeloid cells in glioblastoma across species and disease stage reveals macrophage competition and specialization. Nat Neurosci. (2021) 24:595–610. doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-00789-y

2. Wang L, Jung J, Babikir H, Shamardani K, Jain S, Feng X, et al. A single-cell atlas of glioblastoma evolution under therapy reveals cell-intrinsic and cell-extrinsic therapeutic targets. Nat Cancer. (2022) 3:1534–52. doi: 10.1038/s43018-022-00475-x

3. Abdelfattah N, Kumar P, Wang C, Leu JS, Flynn WF, Gao R, et al. Single-cell analysis of human glioma and immune cells identifies S100A4 as an immunotherapy target. Nat Commun. (2022) 13:767. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28372-y

4. Watson SS, Zomer A, Fournier N, Lourenco J, Quadroni M, Chryplewicz A, et al. Fibrotic response to anti-CSF-1R therapy potentiates glioblastoma recurrence. Cancer Cell. (2024) 42:1507–1527. e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2024.08.012

5. Coy S, Wang S, Stopka SA, Lin JR, Yapp C, Ritch CC, et al. Single cell spatial analysis reveals the topology of immunomodulatory purinergic signaling in glioblastoma. Nat Commun. (2022) 13:4814. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-32430-w

6. Khan F, Pang L, Dunterman M, Lesniak MS, Heimberger AB, and Chen P. Macrophages and microglia in glioblastoma: heterogeneity, plasticity, and therapy. J Clin Invest. (2023) 133. doi: 10.1172/JCI163446

7. Ravi VM, Neidert N, Will P, Joseph K, Maier JP, Kückelhaus J, et al. T-cell dysfunction in the glioblastoma microenvironment is mediated by myeloid cells releasing interleukin-10. Nat Commun. (2022) 13:925. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28523-1

8. Jin S, Plikus MV, and Nie Q. CellChat for systematic analysis of cell–cell communication from single-cell transcriptomics. Nat Protoc. (2025) 20:180–219. doi: 10.1038/s41596-024-01045-4

9. Cesaro G, Nagai JS, Gnoato N, Chiodi A, Tussardi G, Klöker V, et al. Advances and challenges in cell–cell communication inference: a comprehensive review of tools, resources, and future directions. Briefings Bioinf. (2025) 26:bbaf280. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbaf280

10. Sang-Aram C, Browaeys R, Seurinck R, and Saeys Y. Unraveling cell–cell communication with NicheNet by inferring active ligands from transcriptomics data. Nat Protoc. (2025), 1–29. doi: 10.1038/s41596-024-01121-9

11. Liu Z, Sun D, and Wang C. Evaluation of cell-cell interaction methods by integrating single-cell RNA sequencing data with spatial information. Genome Biol. (2022) 23:218. doi: 10.1186/s13059-022-02783-y

12. Palla G, Spitzer H, Klein M, Fischer D, Schaar AC, Kuemmerle LB, et al. Squidpy: a scalable framework for spatial omics analysis. Nat Methods. (2022) 19:171–8. doi: 10.1038/s41592-021-01358-2

13. Raredon MSB, Yang J, Kothapalli N, Lewis W, Kaminski N, Niklason LE, et al. Comprehensive visualization of cell–cell interactions in single-cell and spatial transcriptomics with NICHES. Bioinformatics. (2023) 39:btac775. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btac775

14. Sundaram L, Kumar A, Zatzman M, Salcedo A, Ravindra N, Shams S, et al. Single-cell chromatin accessibility reveals Malignant regulatory programs in primary human cancers. Science. (2024) 385:eadk9217. doi: 10.1126/science.adk9217

15. Kim KH, Migliozzi S, Koo H, Hong JH, Park SM, Kim S, et al. Integrated proteogenomic characterization of glioblastoma evolution. Cancer Cell. (2024) 42:358–377.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.12.015

16. Zhang P, Rashidi A, Zhao J, Silvers C, Wang H, Castro B, et al. STING agonist-loaded, CD47/PD-L1-targeting nanoparticles potentiate antitumor immunity and radiotherapy for glioblastoma. Nat Commun. (2023) 14:1610. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-37328-9

17. Maute R, Xu J, and Weissman IL. CD47–SIRPα-targeted therapeutics: status and prospects. Immuno-Oncology Technol. (2022) 13:100070. doi: 10.1016/j.iotech.2022.100070

18. Li H, Guo L, Su K, Li C, Jiang Y, Wang P, et al. Construction and validation of TACE therapeutic efficacy by ALR score and nomogram: a large, multicenter study. J Hepatocellular Carcinoma. (2023), 1009–17. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S414926

19. Xu H, Russell SN, Steiner K, O'Neill E, and Jones KI. Targeting PI3K-gamma in myeloid driven tumour immune suppression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the preclinical literature. Cancer Immunology Immunotherapy. (2024) 73:204. doi: 10.1007/s00262-024-03779-2

20. Mason K, Sathe A, Hess PR, Rong J, Wu CY, Furth E, et al. Niche-DE: niche-differential gene expression analysis in spatial transcriptomics data identifies context-dependent cell-cell interactions. Genome Biol. (2024) 25:14. doi: 10.1186/s13059-023-03159-6

21. Almet AA, Cang Z, Jin S, and Nie Q. The landscape of cell–cell communication through single-cell transcriptomics. Curr Opin Syst Biol. (2021) 26:12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.coisb.2021.03.007

22. Zhang P, Zhang H, Tang J, Ren Q, Zhang J, Chi H, et al. The integrated single-cell analysis developed an immunogenic cell death signature to predict lung adenocarcinoma prognosis and immunotherapy. Aging (Albany NY). (2023) 15:10305. doi: 10.18632/aging.205077

23. Guan X, Sun L, Shen Y, Jin F, Bo X, Zhu C, et al. Nanoparticle-enhanced radiotherapy synergizes with PD-L1 blockade to limit post-surgical cancer recurrence and metastasis. Nat Commun. (2022) 13:2834. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-30543-w

24. Gottschalk RA and Germain RN. Linking signal input, cell state, and spatial context to inflammatory responses. Curr Opin Immunol. (2024) 91:102462. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2024.102462

25. Su K, Wang F, Li X, Chi H, Zhang J, He K, et al. Effect of external beam radiation therapy versus transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for non-diffuse hepatocellular carcinoma (≥ 5 cm): a multicenter experience over a ten-year period. Front Immunol. (2023) 14:1265959. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1265959

26. Vandereyken K, Sifrim A, Thienpont B, and Voet T. Methods and applications for single-cell and spatial multi-omics. Nat Rev Genet. (2023) 24:494–515. doi: 10.1038/s41576-023-00580-2

27. Rachid Zaim S, Pebworth MP, McGrath I, Okada L, Weiss M, Reading J, et al. MOCHA’s advanced statistical modeling of scATAC-seq data enables functional genomic inference in large human cohorts. Nat Commun. (2024) 15:6828. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-50612-6

28. Bae S, Lee H, Na KJ, Lee DS, Choi H, and Kim YT. STopover captures spatial colocalization and interaction in the tumor microenvironment using topological analysis in spatial transcriptomics data. Genome Med. (2025) 17:33. doi: 10.1186/s13073-025-01457-1

29. Yang J, Shi P, Li Y, Zuo Y, Nie Y, Xu T, et al. Regulatory mechanisms orchestrating cellular diversity of Cd36+ olfactory sensory neurons revealed by scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq analysis. Cell Rep. (2024) 43. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2024.114671

30. Bill R, Wirapati P, Messemaker M, Roh W, Zitti B, Duval F, et al. CXCL9: SPP1 macrophage polarity identifies a network of cellular programs that control human cancers. Science. (2023) 381:515–24. doi: 10.1126/science.ade2292

31. He S, Su L, Hu H, Liu H, Xiong J, Gong X, et al. Immunoregulatory functions and therapeutic potential of natural killer cell-derived extracellular vesicles in chronic diseases. Front Immunol. (2024) 14:1328094. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1328094

32. Ren Y, Huang Z, Zhou L, Xiao P, Song J, He P, et al. Spatial transcriptomics reveals niche-specific enrichment and vulnerabilities of radial glial stem-like cells in Malignant gliomas. Nat Commun. (2023) 14:1028. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-36707-6

33. Magri S, Musca B, Pinton L, Orecchini E, Belladonna ML, Orabona C, et al. The immunosuppression pathway of tumor-associated macrophages is controlled by heme oxygenase-1 in glioblastoma patients. Int J Cancer. (2022) 151:2265–77. doi: 10.1002/ijc.34270

34. Liu R, Liu J, Cao Q, Chu Y, Chi H, Zhang J, et al. Identification of crucial genes through WGCNA in the progression of gastric cancer. J Cancer. (2024) 15:3284. doi: 10.7150/jca.95757

35. Liu H, Zhao Q, Tan L, Wu X, Huang R, Zuo Y, et al. Neutralizing IL-8 potentiates immune checkpoint blockade efficacy for glioma. Cancer Cell. (2023) 41:693–710.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.03.004

36. Tang W, Lo CWS, Ma W, Chu ATW, Tong AHY, and Chung BHY. Revealing the role of SPP1+ macrophages in glioma prognosis and therapeutic targeting by investigating tumor-associated macrophage landscape in grade 2 and 3 gliomas. Cell Bioscience. (2024) 14:37. doi: 10.1186/s13578-024-01218-4

37. Reinfeld BI, Madden MZ, Wolf MM, Chytil A, Bader JE, Patterson AR, et al. Cell-programmed nutrient partitioning in the tumour microenvironment. Nature. (2021) 593:282–8. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03442-1

38. Li X, Xu H, Du Z, Cao Q, and Liu X. Advances in the study of tertiary lymphoid structures in the immunotherapy of breast cancer. Front Oncol. (2024) 14:1382701. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1382701

39. Manoharan VT, Abdelkareem A, Gill G, Brown S, Gillmor A, Hall C, et al. Spatiotemporal modeling reveals high-resolution invasion states in glioblastoma. Genome Biol. (2024) 25:264. doi: 10.1186/s13059-024-03407-3

40. Wang X, Sun Q, Liu T, Lu H, Lin X, Wang W, et al. Single-cell multi-omics sequencing uncovers region-specific plasticity of glioblastoma for complementary therapeutic targeting. Sci Adv. (2024) 10:eadn4306. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adn4306

41. Yang W, Wang P, Xu S, Wang T, Luo M, Cai Y, et al. Deciphering cell–cell communication at single-cell resolution for spatial transcriptomics with subgraph-based graph attention network. Nat Commun. (2024) 15:7101. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-51329-2

42. Efremova M, Vento-Tormo M, Teichmann SA, and Vento-Tormo R. CellPhoneDB: inferring cell–cell communication from combined expression of multi-subunit ligand–receptor complexes. Nat Protoc. (2020) 15:1484–506. doi: 10.1038/s41596-020-0292-x

43. Li H, Zhou J, Li Z, Chen S, Liao X, Zhang B, et al. A comprehensive benchmarking with practical guidelines for cellular deconvolution of spatial transcriptomics. Nat Commun. (2023) 14:1548. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-37168-7

44. Jackson KC and Pachter L. A standard for sharing spatial transcriptomics data. Cell Genomics. (2023) 3:100374. doi: 10.1016/j.xgen.2023.100374

45. Moses L and Pachter L. Museum of spatial transcriptomics. Nat Methods. (2022) 19:534–46. doi: 10.1038/s41592-022-01409-2

46. Guilhamon P, Chesnelong C, Kushida MM, Nikolic A, Singhal D, MacLeod G, et al. Single-cell chromatin accessibility profiling of glioblastoma identifies an invasive cancer stem cell population associated with lower survival. Elife. (2021) 10:e64090. doi: 10.7554/eLife.64090

47. Cao Q, Zhang Q, Chen YQ, Fan AD, and Zhang XL. Risk factors for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in Chengdu: a prospective cohort study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. (2022) 26:9447–56.

48. Mendez JS, Cohen AL, Eckenstein M, Jensen RL, Burt LM, Salzman KL, et al. Phase 1b/2 study of orally administered pexidartinib in combination with radiation therapy and temozolomide in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncology Adv. (2024) 6:vdae202. doi: 10.1093/noajnl/vdae202

49. Xu JG, Chen S, He Y, Zhu X, Wang Y, Ye Z, et al. An antibody cocktail targeting two different CD73 epitopes enhances enzyme inhibition and tumor control. Nat Commun. (2024) 15:10872. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-55207-9

50. Winzer R, Nguyen DH, Schoppmeier F, Cortesi F, Gagliani N, and Tolosa E. Purinergic enzymes on extracellular vesicles: Immune modulation on the go. Front Immunol. (2024) 15:1362996. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1362996

51. Braganhol E, de Andrade GPB, Santos GT, and Stefani MA. ENTPD1 (CD39) and NT5E (CD73) expression in human glioblastoma: an in silico analysis. Purinergic Signalling. (2024) 20:285–9. doi: 10.1007/s11302-023-09951-0

52. Heumos L, Schaar AC, Lance C, Litinetskaya A, Drost F, Zappia L, et al. Best practices for single-cell analysis across modalities. Nat Rev Genet. (2023) 24:550–72. doi: 10.1038/s41576-023-00586-w

53. Schott M, León-Periñán D, Splendiani E, Strenger L, Licha JR, Pentimalli TM, et al. Open-ST: High-resolution spatial transcriptomics in 3D. Cell. (2024) 187:3953–3972.e26. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2024.05.055

54. Kuemmerle LB, Luecken MD, Firsova AB, Barros de Andrade Sousa E L, Straßer L, Mekki II, et al. Probe set selection for targeted spatial transcriptomics. Nat Methods. (2024) 21:2260–70. doi: 10.1038/s41592-024-02496-z

55. Xu Z, Wang Y, Xie T, Luo R, Ni HL, Xiang H, et al. Panoramic spatial enhanced resolution proteomics (PSERP) reveals tumor architecture and heterogeneity in gliomas. J Hematol Oncol. (2025) 18:58. doi: 10.1186/s13045-025-01710-5

56. Yu KKH, Basu S, Baquer G, Ahn R, Gantchev J, Jindal S, et al. Investigative needle core biopsies support multimodal deep-data generation in glioblastoma. Nat Commun. (2025) 16:1–23. doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-58452-8

57. Greenwald AC, Darnell NG, Hoefflin R, Simkin D, Mount CW, Gonzalez Castro LN, et al. Integrative spatial analysis reveals a multi-layered organization of glioblastoma. Cell. (2024) 187:2485–2501.e26. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2024.03.029

58. Williams CG, Lee HJ, Asatsuma T, Vento-Tormo R, and Haque A. An introduction to spatial transcriptomics for biomedical research. Genome Med. (2022) 14:68. doi: 10.1186/s13073-022-01075-1

59. Zheng Y, Carrillo-Perez F, Pizurica M, Heiland DH, and Gevaert O. Spatial cellular architecture predicts prognosis in glioblastoma. Nat Commun. (2023) 14:4122. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-39933-0

60. Moffet JJD, Fatunla OE, Freytag L, Kriel J, Jones JJ, Roberts-Thomson SJ, et al. Spatial architecture of high-grade glioma reveals tumor heterogeneity within distinct domains. Neuro-Oncology Adv. (2023) 5:vdad142.

61. Shen L, Zhang Z, Wu P, Yang J, Cai Y, Chen K, et al. Mechanistic insight into glioma through spatially multidimensional proteomics. Sci Adv. (2024) 10:eadk1721. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adk1721

62. Sun C, Wang A, Zhou Y, Chen P, Wang X, Huang J, et al. Spatially resolved multi-omics highlights cell-specific metabolic remodeling and interactions in gastric cancer. Nat Commun. (2023) 14:2692. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-38360-5

63. Guichet PO, Guelfi S, Teigell M, Hoppe L, Bakalara N, Bauchet L, et al. Notch1 stimulation induces a vascularization switch with pericyte-like cell differentiation of glioblastoma stem cells. Stem Cells. (2015) 33:21–34. doi: 10.1002/stem.1767

64. Skarne N, D’Souza RCJ, Palethorpe HM, Bradbrook KA, Gomez GA, and Day BW. Personalising glioblastoma medicine: explant organoid applications, challenges and future perspectives. Acta Neuropathologica Commun. (2025) 13:6. doi: 10.1186/s40478-025-01928-x

65. Bonnett SA, Rosenbloom AB, Ong GT, Conner M, Rininger ABE, Newhouse D, et al. Ultra high-plex spatial proteogenomic investigation of giant cell glioblastoma multiforme immune infiltrates reveals distinct protein and RNA expression profiles. Cancer Res Commun. (2023) 3:763–79. doi: 10.1158/2767-9764.CRC-22-0396

66. Hong DS, Postow M, Chmielowski B, Sullivan R, Patnaik A, Cohen EEW, et al. Eganelisib, a first-in-class PI3Kγ inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors: results of the phase 1/1b MARIO-1 trial. Clin Cancer Res. (2023) 29:2210–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-22-3313

67. Zhou Y, Guo Y, Chen L, Zhang X, Wu W, Yang Z, et al. Co-delivery of phagocytosis checkpoint and STING agonist by a Trojan horse nanocapsule for orthotopic glioma immunotherapy. Theranostics. (2022) 12:5488. doi: 10.7150/thno.73104

68. Martins TA, Kaymak D, Tatari N, Gerster F, Hogan S, Ritz MF, et al. Enhancing anti-EGFRvIII CAR T cell therapy against glioblastoma with a paracrine SIRPγ-derived CD47 blocker. Nat Commun. (2024) 15:9718. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-54129-w

69. Hamed AA, Hua K, Trinh QM, Simons BD, Marioni JC, Stein LD, et al. Gliomagenesis mimics an injury response orchestrated by neural crest-like cells. Nature. (2025) 638:499–509. doi: 10.1038/s41586-024-08356-2

70. Koo H and Sa JK. Proteogenomic insights into glioblastoma evolution: neuronal reprogramming and therapeutic vulnerabilities. Brain Tumor Res Treat. (2025) 13:81. doi: 10.14791/btrt.2025.0018

71. Cao Q, Wu X, Zhang Q, Gong J, Chen Y, You Y, et al. Mechanisms of action of the BCL-2 inhibitor venetoclax in multiple myeloma: a literature review. Front Pharmacol. (2023) 14:1291920. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1291920

72. Hsieh WC, Budiarto BR, Wang YF, Lin CY, Gwo MC, So DK, et al. Spatial multi-omics analyses of the tumor immune microenvironment. J Biomed Sci. (2022) 29:96. doi: 10.1186/s12929-022-00879-y

73. Ravi VM, Will P, Kueckelhaus J, Sun N, Joseph K, Salié H, et al. Spatially resolved multi-omics deciphers bidirectional tumor-host interdependence in glioblastoma. Cancer Cell. (2022) 40:639–655.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2022.05.009

74. De Rosis S, Monaco G, Hu J, Hett E, Lappano R, Marincola FM, et al. The dark matter in cancer immunology: beyond the visible–unveiling multiomics pathways to breakthrough therapies. J Trans Med. (2025) 23:808. doi: 10.1186/s12967-025-06839-y

75. Liu L, Kitano J, Shigenobu S, and Ishikawa A. Co-profiling of single-cell gene expression and chromatin landscapes in stickleback pituitary. Sci Data. (2025) 12:41. doi: 10.1038/s41597-025-04376-3

76. Wu X, Zhou Z, Cao Q, Chen Y, Gong J, Zhang Q, et al. Reprogramming of Treg cells in the inflammatory microenvironment during immunotherapy: a literature review. Front Immunol. (2023) 14:1268188. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1268188

77. Wu R, Veličković M, and Burnum-Johnson KE. From single cell to spatial multi-omics: unveiling molecular mechanisms in dynamic and heterogeneous systems. Curr Opin Biotechnol. (2024) 89:103174. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2024.103174

78. Zhang D, Deng Y, Kukanja P, et al. Spatial epigenome–transcriptome co-profiling of mammalian tissues. Nature. (2023) 616:113–22. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-05795-1

79. Al-Mansour FSH, Almasoudi HH, and Albarrati A. Mapping molecular landscapes in triple-negative breast cancer: insights from spatial transcriptomics. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch Pharmacol. (2025), 1–19. doi: 10.1007/s00210-025-04057-3

80. Wankhede DS and Selvarani R. Dynamic architecture based deep learning approach for glioblastoma brain tumor survival prediction. Neurosci Inf. (2022) 2:100062. doi: 10.1016/j.neuri.2022.100062

81. Karimi E, Yu MW, Maritan SM, Perus LJM, Rezanejad M, Sorin M, et al. Single-cell spatial immune landscapes of primary and metastatic brain tumours. Nature. (2023) 614:555–63. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05680-3

82. Guimarães GR, Maklouf GR, Teixeira CE, de Oliveira Santos L, Tessarollo NG, de Toledo NE, et al. Single-cell resolution characterization of myeloid-derived cell states with implication in cancer outcome. Nat Commun. (2024) 15:5694. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-49916-4

83. Haley MJ, Bere L, Minshull J, Georgaka S, Garcia-Martin N, Howell G, et al. Hypoxia coordinates the spatial landscape of myeloid cells within glioblastoma to affect survival. Sci Adv. (2024) 10:eadj3301. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adj3301

84. Wang Y, Luo R, Zhang X, Xiang H, Yang B, Feng J, et al. Proteogenomics of diffuse gliomas reveal molecular subtypes associated with specific therapeutic targets and immune-evasion mechanisms. Nat Commun. (2023) 14:505. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-36005-1

85. van Vlerken-Ysla L, Tyurina YY, Kagan VE, and Gabrilovich DI. Functional states of myeloid cells in cancer. Cancer Cell. (2023) 41:490–504. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.02.009

86. Jiang D, Wu X, Deng Y, Yang X, Wang Z, Tang Y, et al. Single-cell profiling reveals conserved differentiation and partial EMT programs orchestrating ecosystem-level antagonisms in head and neck cancer. J Cell Mol Med. (2025) 29:e70575. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.70575

87. Enfield KSS, Colliver E, Lee C, Magness A, Moore DA, Sivakumar M, et al. Spatial architecture of myeloid and T cells orchestrates immune evasion and clinical outcome in lung cancer. Cancer Discov. (2024) 14:1018–47. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-23-1380

88. Zhou X, Liu X, and Huang L. Macrophage-mediated tumor cell phagocytosis: opportunity for nanomedicine intervention. Advanced Funct materials. (2021) 31:2006220. doi: 10.1002/adfm.202006220

Keywords: glioma, tumor-associated macrophages, microglia, ligand–receptor signaling, single-cell RNA sequencing, spatial transcriptomics, immune evasion

Citation: Zhang D, Ma Y and Feng D (2025) Mapping TAM–tumor crosstalk in glioma via ligand–receptor multi-omics: mechanisms of immune evasion. Front. Immunol. 16:1699915. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1699915

Received: 05 September 2025; Accepted: 03 November 2025;

Published: 21 November 2025.

Edited by:

Shengshan Xu, Jiangmen Central Hospital, ChinaReviewed by:

Cristiana Tanase, Victor Babes National Institute of Pathology (INCDVB), RomaniaHao Zhang, Chongqing Medical University, China

Copyright © 2025 Zhang, Ma and Feng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Daxiong Feng, bWVueXU4MTAzMjRAMTYzLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Dong Zhang1,2†

Dong Zhang1,2† Daxiong Feng

Daxiong Feng