Abstract

In type 1 diabetes (T1D), chronic autoimmune responses lead to the destruction of β-cells in pancreatic islets. As more of the β-cell mass is destroyed, the disease progresses, resulting in insulin deficiency. Recent discoveries uncovering the mechanisms behind the autoimmune attack on β-cells have allowed for a better understanding of the development of the disease and categorizing it into stages of progression. Further, FDA approval of the first drug for the prevention of T1D demonstrated the potential for early intervention therapies. Meanwhile, for patients whose β-cell mass is fully destroyed, islet transplantation has been shown to achieve long-term insulin independence. However, this procedure requires lifelong immunosuppression, which can increase the risk of infections and malignancies. Here, we will review recent advances in immunomodulation approaches for the prevention of type 1 diabetes and strategies for islet cell replacement. First, we introduce the pathogenesis of T1D and the stages of the disease that require different immunomodulatory approaches. Then, we will discuss current immunotherapies for the prevention of T1D, highlighting strategies such as antigen-specific, immune blockade, and cell-based therapies, which aim to stop autoimmune attack for patients at early stages of T1D. Afterwards, we discuss advancement for islet replacement approaches, highlighting islet engineering, device encapsulation, and immunomodulatory biomaterials, which aim to prolong the survival of transplanted islets and minimize the need for immunosuppression. We expect this review to provide a comprehensive understanding of current advances in immunomodulatory therapies for T1D.

1 Introduction

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is a chronic autoimmune disease in which insulin-producing islet β-cells are destroyed by the host immune system, causing the lifelong need for exogenous insulin supply. T1D affects more than 9.5 million people worldwide, and that number is expected to grow to between 13.5 and 17.4 million individuals by 2040 (1, 2). Additionally, the incidence of T1D is increasing in both youth and older adults (3, 4). For instance, T1D incidence among youth aged 10–24 years has grown from 7.78 in 1990 to 11.07 in 2019 per 100,000 individuals (3). At the same time, several studies have demonstrated a peak in T1D incidence among older adults (4). Of the 503,000 newly diagnosed cases of T1D in 2024, 56% were adults, further emphasizing the increasing incidence of T1D in that population (5).

T1D development tends to occur in individuals with a genetic predisposition triggered by environmental or immunological events. Genetic predisposition is determined by specific combinations of genes in the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) region, which affect how T cells recognize and tolerate foreign and self-molecules (6). It is also influenced by polymorphism in genes encoding protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTPN22) (7), cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA4) (8, 9), IL-2 receptor subunit a (IL2Ra) (10) and other genes involved in regulating immune responses. Additionally, polymorphism in insulin (INS) leads to the escape of autoreactive T cells from the thymus (11, 12). These genetic factors play a crucial role in shaping the immune response.

T1D development is closely linked with β-cells mass destruction, and the disease progresses as more β-cells are lost (Figure 1A) (13, 14). For earlier stages of T1D, where most of the β-cells’ mass is still intact, there is an opportunity window for immunotherapies to prevent further autoimmune attack and destruction of β-cells (15). For advanced T1D patients, where β-cell mass is severely reduced, maintaining normoglycemia with insulin is challenging (16). The recent FDA approval of Lantidra, the first allogeneic islet therapy for T1D, established islet transplantation as a viable option for some patients, enabling tighter blood glucose control (17). This was a significant milestone for the field as it was the first cell therapy approved for the treatment of T1D. However, this procedure requires extensive immunosuppression to prevent islet graft rejection. The heavy immunosuppressive regimen puts the patient at risk of infections, malignancies, worsening islet graft function, and organ damage (18–20). This highlights the urgent need for novel interventions to prevent autoimmune attack on β-cells and delay disease progression. In parallel, innovative strategies must be developed to support the long-term survival of transplanted islets in advanced-stage patients without systemic immunosuppression.

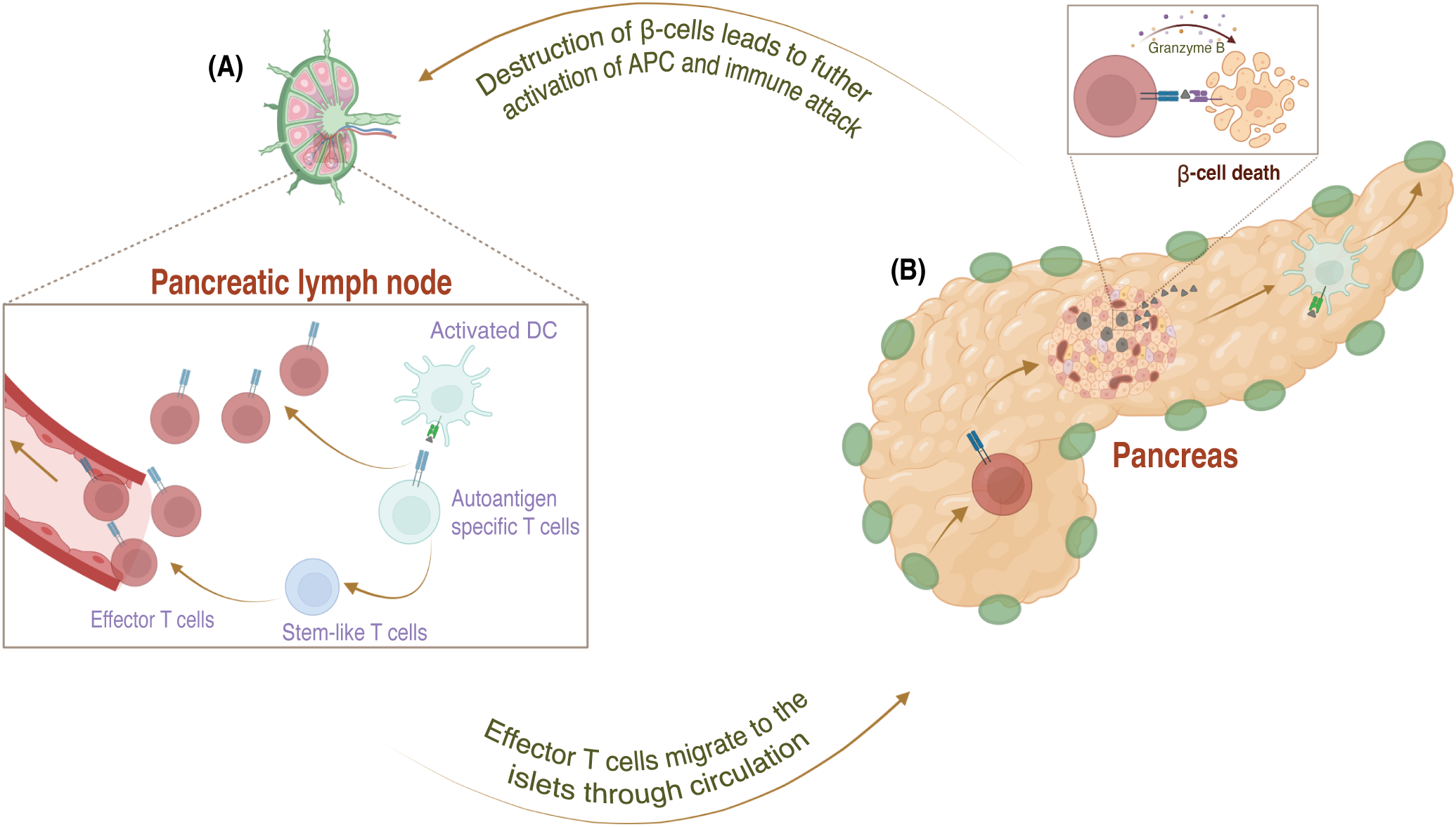

Figure 1

The immunomodulatory strategies as Type 1 diabetes progresses. (A) Type 1 diabetes progresses as the β-cells mass is lost. There are several stages of T1D: Stage 1 is characterized by two or more autoantibodies; Stage 2 includes two or more autoantibodies along with β-cell dysfunction: Stage 3 corresponds to clinical T1D; and Stage 4, which is long-standing T1D. (B) Approaches for the prevention of the onset and β-cell replacement as the disease progresses. (i) Antigen-specific strategies utilizing autoantigens have been investigated for individuals at stage 1 or at risk of T1D. These approaches present antigens in a non-inflammatory environment to shift the phenotype of autoreactive T cells by anergy or tolerizing them to become type 1 regulatory cells. These approaches rely on tolerogenic dendritic cells. Hence, nanoparticles that can shift dendritic cell phenotype to become tolerogenic are often utilized for antigen delivery. (ii) While for stage 2 & 3 T1D patients, immune blockade approaches targeting T cells, antigen-presenting cells, and proinflammatory cytokines could be promising to prevent autoimmune attack on β-cells. (iii) Additionally, cell-based therapies utilizing regulatory T cells and tolerogenic dendritic cells have the potential to inhibit the activity of autoreactive effector T cells in stages 2 & 3 of the disease. (iv-vi) For patients at the later stage of T1D, β-cell replacement utilizing engineered islets, encapsulation in biomaterials, and utilizing immunomodulatory biomaterials to enhance islet graft survival have been explored. (iv) Islets have been engineered to downregulate MHC class and overexpress CD47 to prevent their recognition and destruction by the immune system. (v) Alternatively, encapsulation of islets can mitigate immune clearance, which has been investigated in the clinic. (vi) Biomaterials incorporating chemically modified coating, immunomodulatory agents (including cytokines, chemokines, checkpoint ligands), and immunomodulatory drugs have been explored for long-term graft protection. NP, nanoparticle; tDC, tolerogenic dendritic cells; Tr1, type 1 regulatory T cell; Grzm B, granzyme B; Teff, effector T cell; Treg, regulatory T cell; MHC, major histocompatibility complex.

This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of immunomodulatory approaches across all stages of T1D progression. First, we will discuss prevention strategies, such as antigen-specific, immune blockade, and cell-based therapies, which aim to protect endogenous β-cells. Then we will review the strategies for islet replacement, which are necessary at the later stages when majority of β-cells mass is destroyed, including utilizing engineered islets, islet encapsulation in macro or micro device and utilizing immunomodulatory biomaterials for long-term survival graft islets (Figure 1B). These approaches are inherently linked, as advances in immune modulation directly impact the success and durability of β-cell replacement therapies by preventing graft rejection and recurrent autoimmunity. Overall, we expect this review to provide an extensive summary of the latest advancements and remaining gaps in the field of immunomodulation for prevention and cure for T1D.

2 Immunological mechanism of T1D

Although the immune mechanisms leading to β-cell autoimmunity are heterogeneous, T1D is believed to be a T-cell-mediated autoimmune disease. The defects in both central and peripheral tolerance lead to the generation of autoreactive T cells (12, 21). In central tolerance, naïve T cells travel from the bone marrow to the thymus, undergoing positive and negative selection to develop into CD8 or CD4 cells. T cells acquire their T-cell receptor (TCR) after the positive selection stage, where they demonstrate that they recognize MHC molecules. This is followed by negative selection, where a broad array of peripheral tissue self-antigens is displayed by medullary thymic epithelial cells (mTECs) to deplete self-reactive T cells from the pool, which demonstrate high-affinity TCR binding to MHC presenting self-antigen (22). In the case of T1D, various parameters can influence the efficiency of negative selection. For instance, low expression of insulin due to the polymorphism at the INS gene promoter results in defective negative selection of insulin-reactive T cells. At the same time, expression of the PTPN22 gene leads to diminished TCR signaling and consequent reduction of apoptosis of autoreactive T cells (23, 24).

Once autoreactive T cells reach the periphery, dendritic cells in the pancreatic draining lymph nodes serve as antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and present fragments of islet molecules from damaged β-cells to these T cells. Additionally, these dendritic cells secrete cytokines interleukin (IL)-12 and -15, enhancing the expression of costimulatory molecules and activating the autoreactive T cells (11, 25). Activated autoreactive T cells then differentiate into effector T cells and migrate to the islets through the circulation. A small population of autoreactive T cells exists in the pancreatic lymph node as stem-like T cells continuously sustaining anti-islet immunity. This is important because effector T cells have a short lifespan and do not persist once they reach the islet niche (12, 25, 26). Upon reaching the islets, the autoreactive effector T cells initiate insulitis, an infiltration of immune cells into the pancreatic islets, marking immune-mediated β-cells for destruction. During this process, autoreactive effector CD8 cells destroy β-cells by secreting IFNγ and granzyme B (Figure 2), while CD4 cells contribute by secreting proinflammatory cytokines (21, 26–30). Although immune cells play an essential role in the destruction of β-cells, recent findings also suggest that β-cells themselves are prone to self-destruction due to their susceptibility to stress and limited self-defense (21). This suggests that escaped autoreactive T cells, in tandem with susceptible β-cells, may lead to autoimmunity in T1D.

Figure 2

The mechanism of pathogenesis in Type 1 diabetes in the periphery. (A) In the pancreatic lymph node, APCs activate these autoreactive T cells, which escape negative selection, by presenting antigens from damaged β-cells and providing a co-stimulatory signal via secretion of proinflammatory cytokines. Activated autoreactive T cells differentiate into effector cells and migrate to the pancreatic islets through the bloodstream. (B) In the pancreas, effector T cells attack the β-cells by secreting interferon (IFN)-γ and granzyme (B) The initial destruction of β-cells leads to a vicious cycle that fuels the immune attack and speeds up the destruction of even more β-cells.

3 Prevention approaches for T1D

Recent advancements in early genetic and antibody-based screening, coupled with an enhanced understanding of the pathogenesis of disease, have significantly accelerated the progression in T1D prevention efforts (31, 32). Consequently, the ability to identify at-risk patients allowed for the development and evaluation of stage-specific prevention strategies. For instance, antigen-specific strategies have been explored for patients at the early stage of T1D to alter autoreactive T-cell response. This approach relies on utilizing antigens presented in a tolerogenic context to silence autoreactive T cells (33). For individuals at stage 2 and stage 3, approaches such as immune blockade and cell-based immunotherapies have been pursued. The immune blockade approaches encompass monoclonal antibodies that target T cells, antigen-presenting cells, or proinflammatory cytokines, thereby preventing these immune components from driving disease progression. Meanwhile, cell-based therapies involve engineering immune cells, (e.g., Tregs, dendritic cells) immunomodulatory stromal cells (e.g., MSCs) or platelets to enhance their tolerogenic function to prevent autoimmune attack (Figure 1B). Together, these approaches reflect a shift toward precision prevention in T1D, emphasizing the importance of tailoring immunotherapeutic interventions to the underlying immunological landscape and disease stage. However, for individuals in stage 4, the research focus shifts towards islet replacement strategies. A major barrier in this field has been the reliance on systemic immunosuppression, which carries significant risks. To address this, next-generation therapies have been developed to achieve localized immunomodulation.

3.1 Antigen-specific

As preclinical models have allowed a greater understanding of T1D disease mechanisms, antigen-specific strategies have become a point of interest. By presenting the autoantigens in a tolerogenic environment through controlled delivery of the antigens themselves or manipulation of immune cells, antigen-specific aims to combat autoimmune responses. Many antigen-specific strategies are discussed in this review, from antigen-specific regulatory T cells to tolerogenic dendritic cells pulsed with personalized peptides. This section focuses on autoantigens, the most notable being insulin, which has seen much exploration in clinical trials (34).

Autoantigens, or self-antigens, are produced within the body and are recognized as threats to the immune systems of patients with autoimmune diseases. The most prominent autoantigens used to test for T1D, which are now targeted in clinical trials for T1D prevention, are insulin, proinsulin, and glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD65) (Table 1) (35). In recent years, efforts have mainly been centered on assessing whether insulin administration can affect immune tolerance in high-risk, younger patients as a preventative measure for T1D development. Studies in NOD mice revealed that insulin can achieve tolerance by elevating anti-inflammatory cytokine levels and Tregs (77). NOD mice, widely regarded as the gold standard preclinical model for Type 1 Diabetes, exhibit disease pathogenesis that closely mirrors human T1D, making them invaluable for studying autoimmunity and evaluating therapeutic strategies (78, 79). In 2015, Bonafacio et al. demonstrated that high oral insulin doses in children were safe, causing no hypoglycemia, and induced a protective immune profile characterized by an elevated ratio of regulatory T cells to IFN- γ-expressing cells (80). Since then, studies have found that oral insulin is safe in both children and adults, with the most recent clinical study finding oral insulin to reduce blood glucose levels in adults (36, 41). However, the efficacy of oral insulin as a standalone treatment requires further exploration, as it has shown mixed results across clinical trials. For instance, in the trial involving infants at risk of T1D, oral insulin was ineffective in preventing the development of islet autoantibodies (37). While in another trial, oral insulin was shown to be effective only in a subset of patients with high levels of IA-2 autoantibodies (38). Currently, another clinical trial is investigating a different insulin administration route (intramuscular), utilizing insulin B chain with MAS-1 adjuvant (39).

Table 1

| Target | Treatment name(s) | Progress | Limitations | Status | References, Clinicaltrials.gov identifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin | Oral insulin | Safety objective reached | Treatment not associated with immune response | Phase 2 completed 2017 Phase 2 completed 2024 |

(35–38), NCT02547519 NCT00419562 NCT03364868 |

| Insulin B chain | MER3101 | Results not posted | Results not posted | Phase 1 in progress | (39), NCT03624062 |

| Proinsulin | Gold nanoparticles conjugated with proinsulin peptide | Safe and well tolerated | Small number of participants | Phase 1 completed 2019 | (40), NCT02837094 |

| GAD65 | GAD-alum with Vitamin D/D3 supplementation | Preserves C-peptide levels; | Efficacious in genetically selected group | Phase 2 trials completed 2021 | (41), NCT03345004 |

| CD3 on T cells | Teplizumab (anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody) | Delayed T1D progression in stage 2 patients | Most patients experience adverse effects | Teplizumab FDA approved (2022) | (42–44), NCT03875729, NCT01030861 |

| CD2 on T cells; inhibits T cell stimulation with CD58 | Alefacept (LFA-3-Ig) | Insulin secretion preserved long-term in 30% of patients | β-cell function not preserved | Phase 2 trial terminated | (45, 46), NCT00965458 |

| T-cell surface markers | Anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) | Preserves β-cell function; CD4 exhaustion | Prevented T1D in only 50% of high-risk individuals | Phase 2 completed 2018 | (47–52), NCT02215200 |

| CD2 on T cells and NK cells | Siplizumab (monoclonal antibody) | Results not posted | Results not posted | Phase 2 terminated | (53, 54), NCT05574335, NCT06025110 |

| B7; inhibit co-stimulation of T cells through interaction of B7 with CD28 | Abatacept (CTLA4-Ig) | Preserved insulin secretion and reduced follicular helper T cell population | Did not delay T1D progression, adverse effects | Phase 2 completed 2022 | (55–59), NCT00505375, NCT01773707 |

| CD40 on antigen presenting cells | Frexalimab (anti-CD40L) | Results not posted | Results not posted | Phase 2 trial recruiting | (60) NCT06111586 |

| CD20 on B cells | Autologous Tregs + Rituximab (anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) | Delayed C-peptide level reduction | Adverse effects, did not delay T1D progression | Phase 1/2 trial completed 2022 | (61, 62), NCT00279305, NCT06688331 |

| TNF- α | Golimumab (anti-TNF-α monoclonal antibody) | Long-term benefits, lower reduction in C-peptide | Small number of eligible patients | Phase 2 trials completed 2021 | (63, 64), NCT02846545, NCT02846545 |

| TNF- α | Etanercept (TNF-α inhibitor), GAD-alum, Vitamin D | Feasible and well-tolerated | No effect on β-cell function | Phase 2 completed 2019 | (65), NCT02464033 |

| IL-6 | Tocilizumab (IL-6 receptor inhibitor) | reduced T cell IL-6R signaling | Did not slow β-cell loss of function | Phase 2 completed 2020 | (66), NCT02293837 |

| IL-8 | Ladarixin (IL-8 receptor inhibitor) | Some differences in HbA1C levels | No effect on β-cell function, no change in C-peptide levels | Phase 2 completed 2019 | (67), NCT02814838 |

| GLP-1R | Liraglutide + Tregs | Results not posted | Results not posted | Results not posted | (68), NCT03011021 |

| IL-21, GLP-1R | NN-8828 (anti-IL-21), liraglutide (GLP-1 RA) | Changes in C-peptide and HbA1C levels | Therapeutic effects did not last after treatment stopped | Phase 2 completed 2019 | (69), NCT02443155 |

| IL-12 and IL-23 | Ustekinumab (a monoclonal antibody targeting the p40 subunit) | Well tolerated; higher C-peptide levels | Delayed efficacy | Phase 2 completed 2021; Phase 2/3 in progress | (70) ISRCTN 14274380, NCT03941132 |

| Tregs | Autologous polyclonal Tregs + low dose IL-2 | Expands exogenously administered Tregs | Off-target effects | Phase 1 completed 2021 | (71), NCT02772679 |

| Tregs | Polyclonal expanded Tregs | Safe | Did not preserve C-peptide levels | Phase 2 completed 2020 | (72), NCT02691247 |

| CD4 T cells | PIpepTolDC (Tolerogenic DCs pulsed with islet antigen) | Long-term reduction in T-cell autoreactivity | Assessment pending on if β-cell function is preserved | Phase 1 in progress | (73, 74), NCT04590872 |

| CD8 T cells | AVT001 (Autologous Dendritic Cells) | Less decline from normal C-peptide levels | No significant change in HbA1c and insulin dose | Phase 1/2 completed in 2023 | (75), NCT03895996 |

| Inflammatory immune response | Mesenchymal Stem Cells | Increased Treg population, more anti-inflammatory cytokines, improved HbA1C levels | Limited patients meet eligibility criteria | Status unknown, but likely that Phase 1/2 trial completed in 2020 | (76), NCT04078308 |

Current therapies in clinical trials for the prevention of the onset of diabetes.

Another molecule of interest is proinsulin, the insulin precursor. Proinsulin has been proven effective in preserving β-cell function, but its positive immunomodulatory effects are not uniform across patients (35, 81, 82). Recently, Tatovic et al. tested the safety of gold nanoparticles conjugated with proinsulin peptide. Using microneedles as a delivery system, this method was safe in patients, which may provide a possibility to further optimize proinsulin in clinical trials, using the anti-inflammatory properties of gold (40). On the preclinical front, proinsulin has been combined with other immunomodulatory therapies like IL-10 or anti-CD3 to enhance efficacy in vivo. These efforts aim to address the challenge with current treatment efficacy being dependent on disease duration at the time of administration and continuous oral administration of proinsulin (83).

GAD65 is another autoantigen critical in T1D disease progression and a potential marker of impaired β-cell function (84). GAD combined with aluminum hydroxide, GAD-alum, has been tested in clinical trials. Salami et al. used GAD-alum in healthy children at risk for diabetes, finding that the treatment was associated with lower levels of cytotoxic and autoreactive T cells long-term. However, the trial was terminated early, leading to a small cohort size (85). Ludvigsson et al. combined intra-lymphatic administration of GAD-alum with vitamin D, an immunomodulatory agent, preserving C-peptide levels, a biomarker for insulin production, in patients of a specific haplotype (86). Another well-established autoantigen involved in T1D pathogenesis is insulinoma-associated protein 2 (IA-2). Its presence has been implicated as a good predictor of T1D, but not much work has been done to assess IA-2’s utility for T1D treatment (87). Oral delivery of the intracellular domain of IA-2 using bacterium-like particles in NOD mice prevented T1D onset (88). Zn-T8 has been explored as a diagnostic tool for T1D, but not as a treatment (89, 90).

More recently discovered autoantigens are islet-specific glucose-6-phosphatase catalytic subunit-related protein (IGRP) and chromogranin A (ChGA). IGRP-specific T cells are upregulated in T1D patients (91). Similarly, changes in ChGA concentration can indicate T1D disease progression (92, 93). In NOD mice, a liposome targeting IGRP delayed T1D onset by lessening the activity of autoreactive T cells (94). ChGA-targeted therapies have not been tested in clinical trials, but ChGA deficiency has been shown to reduce T cell autoreactivity and protect mice from T1D (95). In NOD mice, Jamison et al. tested nanoparticles containing an insulin-ChgA hybrid peptide, which prevented T1D by impairing T cells’ ability to produce proinflammatory cytokines; an increase in Tregs and a decrease in effector T cells (Teffs) was observed. Recent work has identified other potential autoantigen targets involved in T1D that may become more prominent in the future, including toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), Tetraspanin, prolyl-4-hydroxylase β subunit (P4Hb), insulin gene enhancer protein (ISL-1), and GRP78 (35, 83, 96–101).

These tolerance-inducing strategies, using autoantigens, seem the most highly tested therapeutic among those discussed in this review. However, challenges persist in this area. Namely, recent clinical trials have primarily served as safety checkpoints, with limited efficacy for patient outcomes. Doses, combinatorial regimes, and administration routes must be refined to improve effectiveness. Further, due to the vast array of immune patterns in T1D patients, it is plausible that certain autoantigens are effective in specific patient groups, rather than serving as a universal cure, presenting a screening barrier for widespread adoption (34). The delivery route remains critical, with ongoing trials investigating intravenous, intranasal, oral, and intralymphatic administration. Further research is needed to standardize delivery methods and optimize antigen-specific therapies for different patient subgroups (102). In this area, therapies targeting immune cells may provide an alternate route.

3.2 Immune blockade

Immune blockade strategies are among the most prominent efforts to prevent autoimmune-mediated β-cell destruction. These approaches target essential T-cell activation, co-stimulation, and inflammatory signaling pathways to preserve β-cell function. This section explores the mechanisms of action currently targeted under investigation in clinical trials and the challenges limiting the wide use of these therapies.

3.2.1 T-cell blockade

Several therapies targeting T cells have been investigated to prevent the progression of T1D (Table 1). The most notable one is teplizumab, an Fc receptor, non-binding humanized anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody, which received FDA approval in 2022. This was a significant milestone since it was a first drug approved for preventing the progression of T1D in patients at stage 2 of the disease (Figure 3A) (42). Treatment with teplizumab comprises a 14-day daily intravenous (IV) course, which has been shown to delay the progression of the disease in 43% of patients for 48.4 months in the phase 2 trial (43). However, due to the nature of the systemic administration of the treatment, multiple adverse events were observed in patients treated with teplizumab. An integrated analysis from five clinical trials revealed that most patients (99.5%) who received the teplizumab course experienced at least one adverse effect associated with the treatment (44). Although adverse events were generally transient, the response to teplizumab among stage 2 patients was heterogeneous (103).

Figure 3

Mechanism of action for promising immunotherapies in clinical trials targeting T cells, APCs, and cytokines for preventing Type 1 Diabetes. (A-D) T cell blockade therapies aim to suppress autoreactive T cells. (A) Anti-CD3 depletes the T cells by binding to CD3 on T cells and preventing their activation. (B) LFA3-Ig antibody prevents T cell activation by targeting CD2 and blocking its interaction with CD58, a critical co-stimulatory signal. (C) Anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) broadly depletes T cells by binding to multiple surface markers, including CD2, CD3, and CD25, etc. (D) CTLA4-Ig inhibits T cell activation by binding to B7, preventing its interaction with the co-stimulatory receptor CD28. (E-F) APC blockade strategies focus on disrupting the activation of antigen-presenting cells. (E) Anti-CD40L blocks the CD40L-CD40 interaction, halting the activation of APCs and subsequent inflammatory signaling. (F) Anti-CD20 targets CD20 on B cells, inducing their apoptosis and reducing autoantibody production. (G-I) To counteract the pro-inflammatory environment of T1D, cytokine blockade therapies target key inflammatory pathways. (G) TNF-α inhibitors behave like TNF receptor 2 or directly block TNF-α, suppressing this pro-inflammatory cytokine’s effects. (H) IL-21 inhibitor neutralizes the pro-inflammatory signaling of this cytokine (I) while anti-12p40/IL23p40 targets the p40 subunit shared by IL-12 and IL-23.

Other therapies targeting the activation of T cells via costimulatory and co-inhibitory signals in new-onset T1D patients, such as LFA-3-Ig, anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG), CTLA4-Ig, have been investigated in clinical trials and showed transient protection of β-cells. For instance, a phase 2 trial in patients with recent-onset T1D treated with LFA-3-Ig fusion protein (alefacept), which binds to CD2 and inhibits T cell co-stimulation with CD58, demonstrated insulin production preserved in 30% of subjects for up to two years post-treatment. LFA-3-Ig was administered via intramuscular injections weekly for two 12-weeks, separated by a 12-week interval. Despite promising results, the trial was terminated due to the discontinuation of production by the drug manufacturer, and enrollment was reduced to 49 participants. (Figure 3B) (45, 104). The peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from trial participants revealed that alefacept allowed for the preservation of β-cells by exhausting CD8 T cells. However, the higher numbers or frequencies of islet antigen–reactive CD4+ T cells were associated with poor response to alefacept, suggesting that dosing may be inadequate to eliminate islet antigen-reactive CD4+ T cells in specific individuals (45, 46). While the clinical trials with LFA-3-Ig were terminated, CTLA4-Ig and anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) are still under investigation (32).

ATG broadly depletes the T cells by recognizing their surface markers, such as TCR/CD3, CD4, CD8, CD25, CD45, HLA class I, and HLA-DR, and binding to them, which leads to T cell killing via complement activation, antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity, or activation-induced cell death (Figure 3C) (47, 48). Although the FDA has approved ATG to prevent renal allograft rejection (49), its efficacy in delaying the progression of type 1 diabetes is still under investigation. A phase 2 trial by TrialNet demonstrated that a 2-day course of treatment with low-dose ATG-infused IV preserved β-cell function for one year in new-onset stage T1D patients (50). Responders to the treatment revealed CD4 exhaustion and temporarily elevated levels of IL-6, CXCL10, and TNF-α two weeks posttreatment (51). The most recent study with children at stage 2 of T1D treated with a 2-day course of a low dose of ATG demonstrated that three subjects (50%) remained diabetes free after 1.5, 3, and 4 years of follow-up, while the other three developed stage 3 within 1–2 months after therapy (52). Siplizumab, a humanized anti-CD2 monoclonal antibody, has also shown depletion of Teffs and promotion of Tregs in vitro (105). Siplizumab was investigated in clinical trials for patients with new-onset T1D; however, the trial was terminated early due to the company’s decision (53). Another dose-finding clinical trial with Siplizumab in patients recently diagnosed with T1D was terminated as well due to excessive lymphodepletion (54).

Humanized CTLA4-Ig fusion protein is a cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen four fused to modified human immunoglobulin G and is another widely studied treatment for preventing the onset of T1D (106). CTLA-4 binds to B7 molecules on antigen-presenting cells (APCs), thereby inhibiting T cell activation and proliferation by blocking the critical B7-CD28 costimulatory signaling pathway(Figure 3D) (107).CTLA4-Ig, abatacept, is already FDA-approved for treating prophylaxis of acute graft versus host disease (108) and rheumatoid arthritis (109); however, similar to ATG, its efficacy for delaying the onset of T1D is still being explored. A recent phase 2 placebo-controlled clinical trial on stage 1 T1D patients who received monthly abatacept IV infusion for 12 months showed that the treatment preserved insulin secretion and reduced the frequency of a subset of ICOS+ follicular helper T (Tfh) cells, which previously was reported to be an indication of successful clinical response in T1D patients (55, 56). Inducible co-stimulatory molecule (ICOS) plays a critical role in positively regulating T cell function, and its elevated expression is linked to an increase in circulating peripheral helper T cells (Tph) (57, 58). However, abatacept infusions did not delay the progression of the disease (56). Previously, abatacept has demonstrated promise in stage 3 T1D by delaying the loss of insulin production by 9.6 months when administered over two years. However, its systemic delivery has been associated with infusion-related adverse effects in 22% of patients, highlighting the need for safer and more targeted approaches for immunotherapy (59).

3.2.2 Antigen-presenting cell blockade

Antigen-presenting cells are also targeted to prevent the progression of T1D, as they participate in the development of the disease by priming autoreactive β-cell-pecific T cells and promoting the activation of autoantibody secretors (110–112). Additionally, APCs can lead to islet graft recognition and subsequent rejection (113–115). One of the currently explored APC blockade therapies is the anti-CD40 ligand (CD40L) antibody (Figure 3E). CD40L expressed on activated T cells binds to CD40, which is strongly expressed on APCs, such as dendritic cells and B cells. CD40 and CD40L interaction leads to inflammatory responses such as B cell activation and differentiation, production of antibodies and proinflammatory cytokines, and T cell clonal expansion (116–118). Although anti-CD40 therapies have also been extensively investigated, they are less efficacious than anti-CD40L targeting approaches in graft rejection prevention (119). For instance, anti-CD40 has been investigated in clinical trials by Novartis (120). Still, the clinical trial was discontinued at phase 2 because it was less efficacious compared to the established regimen for kidney transplant (121). While CD40L targeting therapies have shown promising results in clinical trials for the treatment of autoimmune diseases such as Sjögren’s disease (122), systemic lupus erythematosus (123), and multiple sclerosis (124), it still needs to be explored more in the context of T1D.

Recently, anti-CD40L antibody (frexalimab) has been under investigation in phase 2 clinical trials for preserving endogenous insulin production in newly onset T1D patients (60). Additionally, anti-CD40L has been explored for islet graft rejection mitigation. For instance, preclinical work by Anwar et al. demonstrated an engineered anti-CD40L antibody (tegoprubart) that reduces the risk of thromboembolic events for promoting islet survival in diabetic nonhuman primates (NHPs). Among two NHPs that received the islets and tegoprubart, one demonstrated long-term graft survival for 182 days and increased Treg frequency, while the other one rejected the graft after 2 weeks; however, it showed partial graft function after the second islet transplantation (118). All these promising studies with anti-CD40L lead to an ongoing clinical trial by Eledon in collaboration with the University of Chicago Transplant Institute for evaluating anti-CD40L to prevent rejection of transplanted islets (125).

Another commonly explored therapy for APC blockade is anti-CD20. CD20 is mainly expressed on the surface of B cells (Figure 3F) (126). Hence, anti-CD20 is called B-cell-depleting therapy (61). Previously, a phase 2 clinical trial with rituximab, an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, revealed that four infusions of rituximab over 1 month in recent-onset T1D patients delayed the reduction in C-peptide by 8.2 months (61). This encouraged another clinical trial in combination with autologous expanded Tregs to improve efficacy. However, although the combination with Tregs was better than the Treg alone group, the treatment did not significantly delay the T1D progression (62). Additionally, like in the previous study, there were significant adverse events, 93% in the first study (127) and 80% in the combination study (62), associated with the treatment.

3.2.3 Cytokine blockade

Cytokines play a complex role in T1D pathogenesis, and inflammatory cytokines have been associated with the pathogenesis of T1D as they can exacerbate the condition (128, 129). Several cytokines, such as IFN-γ, IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α (130–132), IL-6 (133), IL-8 (134), IL-12 (135), IL-21 (136), IL-23 (137) have been implicated in β-cell destruction. Several anti-cytokine therapies have been under investigation in clinical trials to address the negative effects of these pro-inflammatory cytokines (Table 1). One such therapy is anti-TNF-α, a monoclonal antibody (golimumab) that demonstrated a 43% lower reduction in C-peptide levels compared to control after 52 weeks of biweekly subcutaneous injections in phase 2 clinical trials in new-onset T1D youth (63). A 2-year follow-up study showed similar trends (64). However, 23% of the golimumab group experienced adverse events associated with the treatment (63). Another TNF-α-blocking therapy is etanercept, which binds to TNFα by acting like its receptor (Figure 3G) (138). The pilot trial, which used a combination of etanercept, GAD-alum, and vitamin D, showed that the treatment was well tolerated but failed to delay the progression of T1D in patients with recent onset (65). IL-6 receptor inhibitor (tocilizumab) is another recently investigated cytokine blockade therapy for new-onset T1D patients. A phase 2 trial with tocilizumab administered IV monthly for 7 months did not delay the loss of β-cells function or change frequencies of CD4 or Treg subsets (66). Another phase 2 clinical trial evaluating the IL-8 receptor inhibitor (ladarixin) administered twice daily in three cycles of two weeks on and two weeks off, in newly diagnosed T1D patients, failed to demonstrate efficacy in delaying disease progression (67). Both studies showed no adverse events associated with the treatment.

Another phase 2 trial evaluated the efficacy of the combination of anti-IL-21 antibody (Figure 3I) (NN-8828) and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA), liraglutide, in adults with recent onset of T1D. Liraglutide was utilized as a GLP-1 RA, which has been shown to be effective in improving glycemic control in T1D patients (139). Anti-IL-21 was administered intravenously every six weeks, while liraglutide was given via subcutaneous injections once daily for 54 weeks. This combination resulted in 48% higher C-peptide levels and a 34% reduction in hypoglycemia in the treatment group after 54 weeks; however, these effects did not last after treatment was discontinued. Additionally, no changes in immune cells were observed (69). A liraglutide and ex vivo expanded Treg combination therapy is currently being assessed in a Phase 1/2 clinical trial. Ustekinumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting the p40 subunit shared by IL-12 and IL-23, was recently investigated in adolescents with recent-onset T1D (Figure 3H). Subcutaneous injections of ustekinumab at weeks 0, 4, and then every 8 weeks until week 44 resulted in 49% higher C-peptide levels than controls at 52 weeks and were well tolerated in patients. While these results are promising, the delayed efficacy of ustekinumab and anti-IL21 compared to less specific T-cell blockade therapies raises concerns about their ability to delay disease progression effectively before the complete loss of β-cell function (70).

Overall, immune blockade strategies have been shown to be efficacious in delaying diabetes onset in some patients with T1D. Furthermore, FDA approval of teplizumab furthered interest in targeting immune players involved in autoimmune attack against β-cells. Building on this momentum, other T cell and APC blockade monoclonal antibodies, initially developed for promoting graft tolerance, are now being repurposed to be investigated for T1D prevention. However, several limitations are associated with these approaches, such as systemic side effects, limited longevity of tolerance, and increased risk of immune-related complications. Although blockades of pro-inflammatory cytokines are currently being explored as an alternative, more targeted approach, the results from clinical trials show that inhibiting these proinflammatory signals may not be enough for robust and sustained control of autoimmunity.

Importantly, most clinical trials evaluate these therapeutics for patients at stage 3 of the disease, potentially missing the opportunity window for preserving more β-cell function. This highlights the need for more advanced and precise screening to identify at-risk individuals earlier and evaluate these interventions for earlier stages of disease. Looking ahead, utilizing regenerative approaches in combination with developing more targeted delivery methods may allow for safer, more durable, and more effective prevention of diabetes progression.

3.3 Cell-based therapies

Cell-based immune therapies have also emerged as a promising treatment for T1D. Therapies in this area seek to target cells involved in T1D pathogenesis and use them to induce tolerance in host immune systems. Tregs and tolerogenic dendritic cells (tDCs) have garnered particular attention in this area. Recent clinical studies have proven the safety of autologous Tregs in human patients (Table 1). However, a strong and desirable immune response was not generated through this method alone (71, 140). Combinatorial regimens and engineered Tregs are being tested in preclinical models to improve efficacy and tolerance. Similarly, tDCs exhibit significant immunoregulatory functions, promoting Treg induction and inhibiting proinflammatory responses. Clinical trials have proven the safety of autologous tDCs, with a current phase 1 clinical trial for T1D assessing a vaccine made of host dendritic cells and a proinsulin protein. Current efforts similarly focus on improving tDC efficacy through genetic engineering or combinatorial regimens in preclinical and clinical trials. Outside of tDCs and Tregs, other cell types such as platelets and MSCs have also been explored for localized immunomodulation. This section reviews recent efforts in cell-based therapies, including insights from clinical trials, engineering efforts, and combinatorial regimens, while addressing remaining challenges in translating these approaches to the clinic.

3.3.1 Regulatory T cell therapy

T cells play a significant role in the inflammation and progression of T1D as cytotoxic T cells destroy pancreatic β-cells. An imbalance between effector T cells and regulatory T cells has also been observed in early T1D development before disease onset (141). Tregs can suppress autoreactive T cells, a critical T1D onset and progression component. For this reason, a depleted Treg population has been implicated in T1D pathogenesis (142, 143). Due to the anti-inflammatory nature of Tregs and their role in autoimmunity, they have been of interest for immunomodulatory therapies (144, 145). While Tregs are also explored for prolonging islet grafts, this section will mostly discuss their application in T1D prevention, where their therapeutic application has been more extensively pursued. Despite their therapeutic promise, Tregs can be hard to isolate from blood and other tissues, making it difficult for T-reg-based therapies to be viably used. Therefore, many therapies focus on engineering effector T cells into Tregs ex vivo to prevent the onset of T1D. Although Tregs are also explored for prolonging islet transplantation survival in clinical trials, this section will mostly discuss prevention effects as more efforts are done in this front.

Clinical trials have primarily been conducted with autologous polyclonal Tregs, which have been well tolerated in patients under a standard immunosuppressive regimen, supporting the safety of Treg therapies (140). Combining Treg therapies with low-dose IL-2 has also been tested in clinical trials. Low-dose IL-2 has been shown to induce an anti-inflammatory gene expression profile in T1D, selectively expand Tregs, and reduce the frequency of IL-21+ T cells (146). In a phase 1 trial by Bluestone et. al, T1D patients were treated with polyclonal Tregs and low-dose IL-2. The IL-2 increased endogenous Tregs within patients’ peripheral blood but also had an off-target effect and expanded cytotoxic cells. Although the Treg infusion was deemed safe, these authors stressed the importance of developing Treg therapies that are more specific to the patient Treg population and avoid off-target effects (71). This previous work can better inform future clinical trials of engineered Tregs and combinatorial regimens. In NOD mouse models, Tregs have also been used with other immunosuppressive agents such as cytokines, antibodies, and standard immunosuppressants to improve engraftment of donor Tregs (147, 148). Further, preclinical work in NOD mice has developed Treg engineering through chimeric antigen receptor technology and genetic engineering.

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) technology is a relatively new method to create Tregs for autoimmune diseases like T1D. Engineered Tregs using CARs allow for the redirection of Treg specificity towards specific targets, which is of special interest as antigen-specific Tregs have been more effective in preventing autoimmune disease onset than polyclonal Tregs (144, 149, 150). Using CAR Tregs to suppress the autoreactivity in T1D can help improve the efficacy of Treg-based therapies (151). Tenspolde et. al, for example, used CARs to change T cell specificity towards insulin and FOXP3 transduction to redirect Teffs to Tregs. Although the generated Tregs did not prevent diabetes progression in NOD mice, they were still detectable after 4 months and mimicked the activity of natural Tregs. Their method was the first recorded instance in literature of using CAR technology to convert Teffs to Tregs for T1D (152). The MHC class II peptide complex has also been a target for CAR Treg technology. This is mainly due to previous work proving that Tregs can regulate immunosuppression by depleting MHC class II peptides (153, 154). Spanier et. al, for example, created the first T cell receptor-like CAR specific for an MHC class II peptide using a monoclonal antibody. In a NOD mouse model, T1D was suppressed entirely when treated with a 3:1 Treg/BDC2.5 T cell ratio (149). Zhang et al. showed that a single infusion of CAR T cells, MHC class II showed antigen-specific Tregs induced through this method, exert a greater protective effect than nonspecific polyclonal Tregs (155, 156). CAR T-regs have been used in clinical trials with some success, primarily as a therapy for solid tumors. While the targets for T1D CAR therapies are different and these previous trials utilize effector T cells rather than regulatory T cells, these examples show that CAR T cell therapy has been proven safe in humans and can likely be adapted for T1D treatment (157, 158).

Engineering gene expression is another method to engineer Treg specificity and T-reg mediated immunoregulation. In this area, many efforts focus on regulating Forkhead box protein 3 (FOXP3) expression, which is essential for Treg suppressive activity (159–161). Most recent studies in this area have used homology-directed repair (HDR) based gene editing to alter the expression of FOXP3. Gene editing through this method has been used to create stable and high expression of FOXP3 in primary human CD4+ T cells, which displayed T-reg-like properties long-term and suppressed polyclonal islet-specific T cells from individuals with T1D and prevented diabetes onset in a T1D mouse model (162, 163). Uenishi et al. used similarly engineered Tregs enriched and expanded with rapamycin to prevent T1D in NOD mice, showing that engineered Tregs can be combined with standard immunosuppressants and enhance T1D outcomes (164). Outside of FOXP3 expression regulation, Rafiqi et al. inhibited the eukaryotic initiation factor 5a (eIF5a), which is overexpressed in T1D patients and promotes a proinflammatory environment, as well as a key pathway in T cell maturation. A Treg phenotype was induced when this method was used on isolated human effector T cells. While these Tregs remain untested in vivo, the group has previously shown that this inhibition is safe in humanized mouse models and on islets in vitro (165, 166).

Clinical trials with Tregs have primarily served to verify the safety of autologous polyclonal Tregs in T1D patients. The focus of preclinical models has been engineering Tregs to enhance their specificity or manufacturing Tregs from Teffs cells. Current clinical trials have allowed for some testing of how autologous polyclonal Tregs are tolerated in patients, potential side effects, doses, and effective administration routes may vary for engineered Tregs. More broadly, concerns also include storage and complex manufacturing processes. In addition, Treg exhaustion can be a further point of concern that limits the efficacy of this therapy (167).

3.3.2 Dendritic cell therapy

Dendritic cells (DCs) are another portion of the immune system being assessed to help form a method of regulating T1D. While there are DCs that tend to be more pro-inflammatory and have been implicated in the pathogenesis of T1D, there are other DCs more associated with immunosuppressive capacities, referred to as tolerogenic dendritic cells (tDCs) (168, 169). Tolerogenic dendritic cells are an immature to semi-mature form of dendritic cells and are functionally distinct from fully mature, pro-inflammatory DCs. Compared to proinflammatory DCs, they exhibit low expression of MHC class II and co-stimulatory molecules such as CD80, CD86, and CD40. Additionally, they are characterized by high expression of IL10 and TGF-β, as well as expression of PD-L1 and PD-L2 (170, 171).They can trigger immunosuppressive activity by influencing T cell populations, increasing Treg activity, and suppressing effector T cells (172–174). Further, tDCs are essential in regulating immune activity, and T1D onset has been associated with fewer tDCs in the pancreatic area (168, 175, 176). Therefore, therapies involving engineered tDCs present a promising avenue to T1D therapies.

Autologous DCs’ safety has previously been evaluated in humans, and current efforts in clinical trials focus on improving the therapy’s efficacy (177). The AVT001 autologous DC therapy targets the Q/E CD8+ Treg pathway, which is defective in many people with type 1 diabetes. This treatment was recently completed in a phase 1/2 clinical trial intended to evaluate the safety of the treatment in patients. Treatment was associated with less decline from normal C-peptide levels, but other indicators like HbA1c and insulin did not demonstrate significant change from baseline (75). However, these results indicate preservation of insulin secretion and show that DC therapies can be viable as T1D treatments. Another clinical trial, in phase 1, utilized vaccines with tDCs pulsed with a proinsulin peptide (73). After verifying this method’s safety, it could selectively stimulate Tregs and reduce effector T cell populations in vivo. This reduction was preserved even two years after treatment, and improved glycemic control was observed in eight of nine patients. These promising results suggest that this method can alter the immune system towards autoantigen-specific tolerance (74).

Preclinical work in NOD mice aims to further enhance the capabilities of tDCs to prevent the onset of T1D. For example, Passeri et al. created tDCs by genetically engineering monocytes with lentiviral vectors co-encoding for immunodominant antigen-derived peptides and IL-10. In two T1D mouse models, the engineered DCs completely prevented disease development in 38% and 45% of recipients by inducing Tregs and downregulating Teffs (178). Further, human dendritic cells engineered with this method were able to inhibit T effector cell responses and promote Treg populations in celiac disease patients in vitro (178). These results support the versatility of this method and its potential viability in clinical trials.

Current work in clinical trials has shown the safety and impact of autologous tDCs on the immune system of T1D patients. However, none of these trials exhibit high efficacy for T1D treatment. Current preclinical trials focus on engineering tDCs to improve effectiveness, with some promising results. However, barriers remain for adoption in clinical trials regarding doses, administration routes, and potential immunogenicity of engineered tDCs in humans.

3.3.3 MSCs therapies

Other immune cells have also been explored to prevent the onset of T1D. MSCs, for example, have been a cell chassis of interest due to their immunomodulatory properties. MSCs have also been investigated in clinical trials as a treatment modality for T1D. Carlsson et. al’s 2014 study first verified the safety of MSCs in T1D patients, and more recent work has been focused on evaluating long-term safety and benefits of this method (179). In a phase 1/2 clinical trial by Izadi et. al, each patient received two doses of bone marrow-derived MSCs and was followed up with for one-year post-transplantation. MSC transplantation was safe long-term and shifted serum cytokine populations from proinflammatory to anti-inflammatory, emphasizing MSCs’ immunomodulatory effects (76). To provide more mechanistic analysis, Wu et al.’s preclinical study found that umbilical cord-derived MSCs helped improve C-peptide levels by inhibiting T cell proliferation (180). MSCs induce immune tolerance by suppressing autoimmune attack from effector T cells and shifting the immune environment to a more anti-inflammatory phenotype (e.g., through secretion of cytokines). Other studies have also noted MSCs’ ability to promote the generation and expansion of regulatory T cells and M2-like macrophages (181). MSCs have also been explored for islet transplantation. For instance, a study by Wang et al. demonstrated the use of engineered MSCs to express PD-L1 and CTLA4-Ig and co-transplanted them with islets in a T1D mouse model. Without systemic immunosuppression, the allograft survived for up to 100 days and had reduced infiltration by T-effector cells with a higher Treg presence (182). However, despite preliminary promising results, there is still a need for more effective and complete immunomodulation, which is the subject of exploration in many preclinical models. As with other therapies, patient-specific characteristics like lifestyle or autoantigens can further affect treatment efficacy, presenting an additional consideration when creating MSC-based therapies (183). Another consideration is poor MSC survival during transplantation due to host immune system attack, requiring long-term immunosuppression, and oxidative stress, among other factors (184).

3.3.4 Platelet cell therapies

Another cell population of interest is platelets. Zhang et al. engineered platelets to express programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1), a commonly explored immunomodulatory checkpoint ligand, achieving long-term reversal of new diabetes onset in 58% of 10-week-old NOD mice treated with ten IV injections of the modified platelets. Notably, these engineered platelets released platelet microparticles (PMPs), which exhibited enhanced infiltration into the pancreas due to their smaller size. Additionally, mice treated with the engineered platelets showed reduced pancreas-infiltrating CD8+ T cells and increased T regs within the pancreas (185). More recently, Zhang et al. bioengineered platelets to produce higher-than-normal amounts of immune checkpoint ligands, including PD-L1, PD-L2, B and T lymphocyte attenuator (BTLA), and Galectin-9 (Gal-9). With this technique, the amount and activity of pancreas-infiltrating T cells were reduced with an increase in Tregs and macrophage polarization towards the M2-like phenotype (186). Despite these results, the therapeutic potential of platelets is limited by their short lifespan, requiring frequent administration. Additionally, platelets may face targeting specificity and stability challenges, which could reduce their efficacy and increase off-target effects (187).

Many cells are involved in T1D and can be harnessed for cell-based therapies. We have discussed MSCs and platelets, including their work in clinical and preclinical models and their drawbacks. While MSCs have immunomodulatory capabilities, poor cell survival presents a drawback. For platelets, their short lifespan limits clinical applicability. Similar disadvantages must be considered with these and other cell types potentially employed in this space.

4 Cell replacement therapies

Despite significant advances in insulin therapy and glucose monitoring technologies, Type 1 diabetes (T1D) remains a lifelong disease characterized by progressive β-cell loss, glycemic instability, and a substantial risk of acute and chronic complications. Even with intensive insulin management, many patients experience hypoglycemia unawareness, glycemic variability, and reduced quality of life, highlighting the fundamental limitation of exogenous insulin in replicating the dynamic, glucose-responsive function of endogenous β-cells. As a result, restoring functional β-cell mass remains the only strategy with the potential to provide durable physiological glycemic control. However, current β-cell replacement approaches are restricted to a small subset of patients with severe disease, require lifelong immunosuppression, and face significant barriers related to graft survival, immune rejection, donor availability, and long-term durability. These limitations underscore the urgent need to improve β-cell replacement therapies beyond existing clinical protocols (188–190).

Allogeneic islet transplantation replenishes the lack of functional β-cells in patients with T1D. The Edmonton protocol, which is the main procedure for transplanting donor human islets by infusion into the hepatic portal vein of the recipient, played a revolutionary role in the islet transplantation field since the early 2000s. Long-term follow-ups in patients receiving human islets have shown promising results in terms of better insulin independence for up to 20 years after transplantation (191–194). As a result, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved Lantidra by CellTrans, the first allogeneic (donor) pancreatic islet cellular therapy made from deceased donor pancreatic cells for treating type 1 diabetes. Lantidra is approved for the treatment of adults with type 1 diabetes who are suffering from severe hypoglycemia. The procedure involves administering 5000 islet equivalents/kg body weight via transhepatic access into the hepatic portal vein. 63% of the patients met the efficacy endpoint determined by HbA1c levels ≤6.5% and absence of severe hypoglycemic events (SHEs) through 1 year after last transplant (195). However, some critical challenges still need to be solved, such as a regulatory framework, like manufacturing consistency, or long-term efficacy. Additionally, transplanted islets are susceptible to instances of blood-mediated inflammatory reactions and rejection, which could lead to their early destruction. Graft rejection can occur through direct recognition, where host T cells identify donor antigens, or indirect recognition, where host antigen-presenting cells (APCs) present donor islet antigens to host T cells alongside costimulatory signals. Alloantigen-specific T cells are activated in both scenarios, destroying donor islets by CD8+ T cells (196–198).

Another point of consideration is that selecting an appropriate transplantation site for donor islets can significantly affect the efficacy of the transplanted cells. The most common transplantation site is the intrahepatic vein due to its accessibility and favorable blood supply. It allows fast diffusion of oxygen and nutrients to the cells and insulin into the blood system. However, this site also poses several challenges, such as instant blood-mediated inflammatory reaction (IBMIR), which leads to immediate loss of a significant portion of transplanted islets, reducing the overall efficacy of the procedure (199). IBMIR is caused by direct exposure of islets to the bloodstream, triggering pro-inflammatory cytokines to be released, which is followed by the activation and recruitment of innate immune cells, enhancing the inflammation and destruction of islets (200). Additionally, transplantation into the intrahepatic vein requires immunosuppressants as the liver’s immune environment can contribute to alloimmune and autoimmune responses against the transplanted islets. Another implantation site is the subcutaneous space, which is also easily accessible but has a relatively poor blood supply, which can impair islet survival and function (201). Finally, transplanting islets into the mesenteric fat offers a better vascularized environment than subcutaneous tissue. Nonetheless, this approach is still under investigation, and long-term outcomes remain uncertain (201).

In contrast, transplantation under the kidney capsule is widely used as a preclinical benchmark site, as it provides a confined and well-vascularized environment that supports robust islet engraftment and facilitates mechanistic studies of revascularization and immune responses. Nevertheless, the kidney subcapsular space has important limitations for Type 1 diabetes therapy, including poor clinical translatability, limited volume, a lack of physiological insulin drainage into the portal circulation, and continued susceptibility to autoimmune and alloimmune attacks in the absence of immunomodulation (202).

Cell therapies have been developed to overcome some of the limitations of using donor islets. One such example is Vertex’s ongoing phase 3 clinical trial using stem cell-derived islets to achieve glycemic correction in patients with T1D (Table 2). This trial investigates zimislecel (formerly known as VX-880), which involves the delivery of the insulin-producing cells via infusion into the hepatic (liver) portal vein. This approach demonstrated insulin independence in 10 out of 12 participants for 1 year (210). However, this platform still requires ongoing immunosuppression, using tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) to suppress T-cell activation and inhibit lymphocyte proliferation, respectively, and therefore to ensure the immune cells do not attack transplanted cells. The need for immunosuppression drugs for life comes with several risks, such as developing kidney diseases (218, 219), infections (220), cancer (221), or β-cells toxicity-related issues (19). These issues highlight the need to develop novel approaches that can improve islet transplantation.

Table 2

| Therapy type | Target/ additional information | Treatment name(s) | Progress | Limitations | Current status | Reference, clinicaltrials.gov identifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Encapsulation | Engrafted pancreatic endoderm cells become islets | VC-02 (stem cell-derived pancreatic endoderm cells) | Safe, positive C-peptide levels in some patients | Only 35% of initial islet mass survived | Phase 1/2 completed 2023 | (203), NCT03163511 |

| Encapsulation | Subcutaneous implant, without immunosuppression and with oxygen supply | Human islets in Beta Air device | Results not posted | Results not posted | Phase 1/2 in progress | (204), NCT02064309 |

| Implantation Device | Abdominal wall pre-vascularized device for 3 weeks with immunosuppression regimen | Sernova Cell Pouch | Stimulated C-peptide levels for 9 months; persistent graft function; reduced HbA1C and insulin dosage | Currently only 7 patients tested; preliminary results; invasive surgery | Phase 1/2 recruiting | (205), NCT03513939 |

| Implantation Device | Subcutaneous abdominal implantation of pre-vascularized device for 22–130 days before islet transplantation | Sernova Cell Pouch | Results not posted | Results not posted | Phase 1/2 terminated | (206), NCT01652911 |

| Implantation Device | Perforated device to deliver cells | VCTX210A, VCTX211 (devices to deliver genetically engineered allogeneic pancreatic endoderm cells) | Results not posted | Results not posted | Phase 1 completed (VCTX210A); Phase 1/2 in progress (VCTX211) | (207, 208), NCT05210530, NCT05565248 |

| Implantation Device | Immunoprotective device that does not require additional immunosuppression | VX-264 (encapsulated stem cell derived islet therapy) | Trial stopped early due to lack of efficacy | Lack of efficacy led to termination | Phase 1/2 terminated (update posted 2025) | (209), NCT05791201 |

| Stem Cell Derived Therapy | Hepatic Portal Vein infusion | Zimislecel (VX-880) | 12 participants treated; restored endogenous insulin secretion; 92% insulin reduction; 10/12 insulin-independent at 1 year; HbA1c <7% and >70% time in range | Requires immunosuppression; durability beyond 1 year still uncertain | Phase 3 recruiting following successful Phase 1/2 | (210, 211), NCT04786262 |

| Stem Cell Derived Therapy | Intramuscular transplantation | Hypoimmune islets | First-in-human treated July 2025; C-peptide detected; insulin production confirmed; HbA1c improved; effect ongoing at 6 months | N=1; short follow-up; donor islet supply constraints; long-term safety unknown | Phase 1 recruiting | (194, 212) NCT06239636 |

| Monoclonal antibody | CD40 on antigen presenting cells | Tegoprubart (anti-CD40L) | Promising results in preclinical model | Results not posted | Phase 1/2 trial recruiting | (125), NCT06305286 |

| MSC + Islets | Transplantation of islets and MSCs in T1D patients | Allograft islets and autograft MSCs | Results not posted | Results not posted | Current status unknown | (213), NCT00646724 |

| Polyclonal Tregs | CD4+ T cells | Ex vivo-selected, and ex vivo-expanded autologous polyTregs combined with islet transplantation | Results not posted | Results not posted | Phase 1 in progress | (214), NCT03444064 |

| Islet + Treg cells | Tregs from either donor or recipient administered with islets | Clinical Islet Transplantation with Apheresis, Isolation and Reintroduction of Recipient Regulatory T Cells | Results not posted | Results not posted | Phase 1 in progress | (215), NCT05973734 |

| Polyclonal Tregs | CD4+ T cells | cePolyTregs (cryopreserved PolyTregs) | Results not posted | Results not posted | Phase 1 in progress | (216), NCT05349591 |

| Encapsulation/Xenotransplantation | Encapsulated porcine islets + device for patients with established T1D and severe hypoglycemia | OPF-310 | Phase I/II trial began; testing safety & dose (6000 or 12,000 IEQ/kg) | Early stage; unknown long-term safety, immune reaction, encapsulation device durability; supply/scaling of xenogeneic islets | Phase I/II recruiting/ongoing | NCT06575426 (217) |

Strategies for islet replacement.

4.1 Islet engineering for enhanced immune evasion

In addition, to address some of the previously mentioned issues, several groups are trying to engineer islets to enhance immune evasion while keeping the functionality of donor islets. One of these strategies is the use of hypoimmune islets, which are genetically engineered pancreatic islets designed to evade immune system detection and rejection. The use of hypoimmune islets allows for the elimination of lifelong immunosuppression while achieving glycemic correction. Hu et al. developed human allogeneic gene-engineered hypoimmune islets, which showed glycemic correction in pre-clinical trials. The authors achieved hypoimmunity by eliminating MHC class I and II expression by knocking out the genes β2-microglobulin (B2M) and class II major histocompatibility complex transactivator (CIITA), respectively, using CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing techniques. In addition, they overexpressed CD47 to prevent phagocytosis by macrophages and natural killer (NK) cell-mediated destruction. The findings demonstrate that the hypoimmune (HIP) islets evaded rejection and restored normal blood glucose in allogeneic humanized mice, autoimmune NOD mice, and STZ-induced diabetic mice for at least 30 days (222). In addition, this same group applied their HIP modifications to induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and tested their survival in a fully immunocompetent, allogeneic rhesus macaque model without immunosuppression. The key findings showed that HIP-iPSCs survived for over 16 weeks after transplantation, significantly longer than unmodified iPSCs, which were rapidly rejected. These HIP cells successfully differentiated into multiple cell types without triggering immune activation, confirming their ability to evade both innate and adaptive immune responses (223). Additionally, the same team also similarly engineered primary pancreatic islets derived from rhesus macaques to create “hypoimmune pseudo-islets”. The authors implanted the engineered cells into a fully immunocompetent diabetic cynomolgus monkey without administering immunosuppressive drugs and showed significant improvements in glucose regulation by observing an initial increase and later stabilization in serum C-peptide levels correlated with controlled blood glucose levels (224). The technology derived from these findings is currently undergoing phase 1 clinical trials as the first in-human safety study of hypoimmune pancreatic islet transplantation in adult subjects with type 1 diabetes (Table 2) (225).

On the other hand, Parent et al. followed a different approach by modifying human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) into insulin-producing cells to minimize the immune system’s recognition and rejection of these cells, by deleting specific HLA genes responsible for presenting antigens to immune cells. The authors removed the highly polymorphic HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C genes, except for retaining the common HLA-A2 allele and the less variable HLA-E, HLA-F, and HLA-G genes. By using humanized mouse models, the researchers demonstrated that these genetically altered islet cells experienced significantly reduced NK cell activity and diminished T-cell-mediated alloimmune responses while not impairing the cells’ ability to function as insulin-producing β-cells (226). Similarly, Gerace et al. genetically engineered human stem cell-derived islets (SC-islets) to express PD-L1 and HLA-E, two immune-regulatory molecules that inhibit T cell and NK cell responses. Using CRISPR-Cas9, the authors knocked out HLA class I molecules to reduce allogeneic recognition while overexpressing PD-L1 to engage inhibitory PD-1 receptors on T cells. The engineered islets were encapsulated in a retrievable device and implanted into immunocompetent mice. These modifications allowed the islets to evade immune rejection and maintain function without systemic immunosuppression.

4.2 Islet encapsulation in micro or macro devices to evade immune clearance

Encapsulation of islets in a biomaterial has previously been shown to be promising in preclinical studies for the long-term survival of transplanted islets by providing an immune-isolative layer to avoid direct graft recognition without immunosuppression (203, 227–231) (203, 228–232) (203, 227–230, 233). Additionally, microencapsulated stem-cell-derived β-cells have been evaluated in clinical trials. Shapiro et al. initially developed a macro-device made of a multi-layer platform made of expanded polytetrafluoroethylene with engineered portals and an external polyester mesh that provides stability. Pancreatic endoderm cells (PEC) were then housed within the macro-encapsulation device, which provided immune protection from the host (VC-02) (Table 2) (203). This platform was tested in a phase 1/2 clinical trial for T1D and demonstrated positive C-peptide levels in 35,3% of patients as early as 6 months post-implant. The device was implanted subcutaneously under the immunosuppression regimen initiated with ATG and maintained with, mycophenolate mofetil and tacrolimus, common immunosuppression drugs to avoid transplant rejection. This clinical trial showed the potential of microencapsulation devices to house β-cells for immune protection and correction of blood glucose levels in type 1 diabetes patients. Despite promising outcomes, analysis of retrieved devices revealed that only 35% of the initial islet mass survived, a significantly lower percentage compared to preclinical studies. This discrepancy may be attributed to a more robust foreign body response in humans, among other contributing factors (231). These findings suggest that current immune isolation strategies, such as microencapsulation and standard immunosuppression regimens, are insufficient to fully mitigate the foreign body response, thereby limiting the long-term survival of transplanted islets. The implantation of foreign materials triggers a cascade of responses that leads to inflammation and recruitment of the immune cells at the site of the implant. This process results in a dense fibrous capsule formation around the device. This fibrotic barrier hinders the exchange of essential nutrients and oxygen, as well as the diffusion of insulin, ultimately compromising the viability of implanted islets and limiting the functionality and longevity of the implant (232, 234, 235).

In parallel, Sernova Biotherapeutics has developed a promising encapsulation platform known as the Cell Pouch™ System, which is an implantable, vascularizing device engineered to house and support insulin-producing cells. So far, for the ongoing phase 1/2 clinical trial at the University of Chicago, the Cell Pouch™ has shown encouraging results in patients with type 1 diabetes who suffer from hypoglycemia unawareness (Table 2). In Cohort A, which involved the implantation of the 8-channel Cell Pouch followed by donor islet transplantation, all six patients achieved sustained insulin independence, with durations ranging from 5.5 months to over four years. The first patient maintained insulin independence for more than 50 months, with HbA1c levels consistently within the non-diabetic range (≤6.5%). Histological analyses confirmed the presence of well-vascularized and functioning islets, producing insulin, glucagon, and somatostatin, even five years post-transplant. In the newer Cohort B, featuring an upgraded 10-channel Cell Pouch with 50% more islet capacity, preliminary data from seven patients show continued production of C-peptide and improved HbA1c levels, suggesting effective and durable islet function. The device has been well-tolerated across all participants, with no significant safety concerns reported, further supporting the potential of the Cell Pouch as a long-term, scalable therapy for restoring natural insulin production in T1D patients (236).

On the other hand, to further enhance the clinical translatability of encapsulation platforms, another approach utilizing oxygen-generating or supplementing technologies is explored. This strategy allows for the survival of high-density encapsulated islets, which can be beneficial for reducing implant size. For instance, Evron et al. demonstrated a device housing encapsulated islets within an alginate protected by an outer polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) membrane, thereby shielding them from host immune responses. These encapsulated islets were supplied with oxygen through the adjacent chamber, which was replenished daily through an external port. This device allowed for the survival of encapsulated allogeneic islets at a surface density of 4,800 islet equivalents/cm3 for more than 7 months in diabetic rats (237). This device is currently investigated in clinical trials (238). Another study by Wang et al. utilized an oxygen-generating device that recycles carbon dioxide generated by islets and converts it into oxygen via lithium peroxide particulates. Here, islets were encapsulated in alginate hydrogel and connected via a hollow silicon tube to the gas tank containing the PFC-immersed lithium oxide formulation. This approach allowed for the survival of rat islets in the diabetic mouse model for over three months (239). Krishnan et al. developed a different oxygen-generating method using electrochemical water splitting by proton-exchange membrane electrolysis to achieve functional survival of encapsulated rat islets at ~1,000 islets/cm2, when implanted in the subcutaneous space of diabetic mice for over 1 month (240). A different approach by Pham et al. utilized body moisture via electrolysis to support a high density of 60,000 IEQ/mL islets. This device allowed for survival of allogeneic islets for up to 3 months in a diabetic rat model (241).

4.3 Immunomodulatory biomaterials

Building on the promise of encapsulation devices, immunomodulatory biomaterials are being developed to enhance graft survival, minimize immune rejection, and avoid systemic toxicity associated with traditional immunosuppression. These materials can create a localized immune-privileged site through foreign body evading-chemical modifications, sustained release of cytokines or chemokines, presentation of checkpoint ligands, or localized delivery of immunosuppressive drugs. This section outlines the diverse strategies used to modulate the local immune environment, their application in preclinical studies, and challenges that remain for durable and scalable translation for curing T1D.

4.3.1 Chemically modified biomaterial for evading foreign body response