- Department of Nephropathy, The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, Henan, China

Introduction: The targeted-release budesonide formulation (Nefecon) addresses IgA nephropathy (IgAN) by inhibiting mucosal immune dysregulation in gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), leading to reduced production of galactose-deficient IgA1 (Gd-IgA1). Randomized controlled trials (NEFIGAN, NefIgArd) have shown that Nefecon effectively decreases proteinuria and decelerates the progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in patients with IgA nephropathy (IgAN). However, evidence in real-world clinical settings and high-risk subgroups remains limited.

Methods: We performed a retrospective cohort study involving 60 IgAN patients treated with Nefecon (16 mg/day) for no less than 6 months at the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University between October 2024 and November 2025. The study focused on evaluating alterations in proteinuria and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Subgroup analyses were further carried out according to the use of concomitant immunosuppressive therapy, baseline proteinuria levels, and baseline renal function.

Results: Proteinuria decreased significantly after 4 and 6 months of Nefecon treatment (median reduction 31.9% and 43.5%, respectively; both p < 0.001), while eGFR remained stable. Patients receiving Nefecon plus glucocorticoid/immunosuppressive therapy achieved greater proteinuria reduction than those on Nefecon monotherapy (48.1% vs. 35.8% at 6 months, p=0.04). Notably, patients with a baseline eGFR < 35 mL/min/1.73 m² showed a 38.9% reduction in proteinuria (p=0.002) without additional renal deterioration. Nefecon was well tolerated, with adverse events being mild.

Conclusion: In routine clinical practice, Nefecon effectively reduces proteinuria and preserves renal function in IgAN, even in patients excluded from randomized trials. The combination with immunosuppressive therapy may provide additive benefit that requires further validation. These findings extend trial results to real-world settings and highlight Nefecon as a practical treatment option for high-risk IgAN patients.

Introduction

IgA nephropathy (IgAN) is the most common primary glomerulonephritis worldwide and a leading cause of end-stage kidney disease. In China (1), IgAN accounts for nearly half of biopsy-confirmed glomerular diseases, with up to 50% of patients progressing to kidney failure within 10–15 years (2, 3). Despite the high burden, current therapies such as glucocorticoids and immunosuppressants carry limited efficacy and substantial toxicity (1), leaving a major unmet need for safer, more effective interventions.

Recent studies emphasize mucosal immunity’s involvement in IgAN pathogenesis, especially the excessive production of galactose-deficient IgA1 in gut-associated lymphoid tissue (4–6). Nefecon, an oral targeted-release budesonide formulation, locally targets the distal ileum to directly suppress the pathogenic process. Phase 2b/3 trials (NEFIGAN, NefIgArd) showed that Nefecon effectively decreases proteinuria and maintains renal function (5–7), resulting in its endorsement in the 2025 KDIGO guideline for high-risk IgAN (8).

However, randomized trials often exclude patients with advanced CKD, recent or concurrent immunosuppressant use, or poor treatment adherence. Consequently, the real-world effectiveness and safety of Nefecon, particularly in Asian populations and high-risk subgroups, remain unclear. We performed a retrospective study on a Chinese cohort of IgAN patients, including those with eGFR <35 mL/min/1.73 m² undergoing immunosuppressive therapy, to assess the clinical utility of Nefecon in real-world settings.

Materials and methods

Study framework and subjects

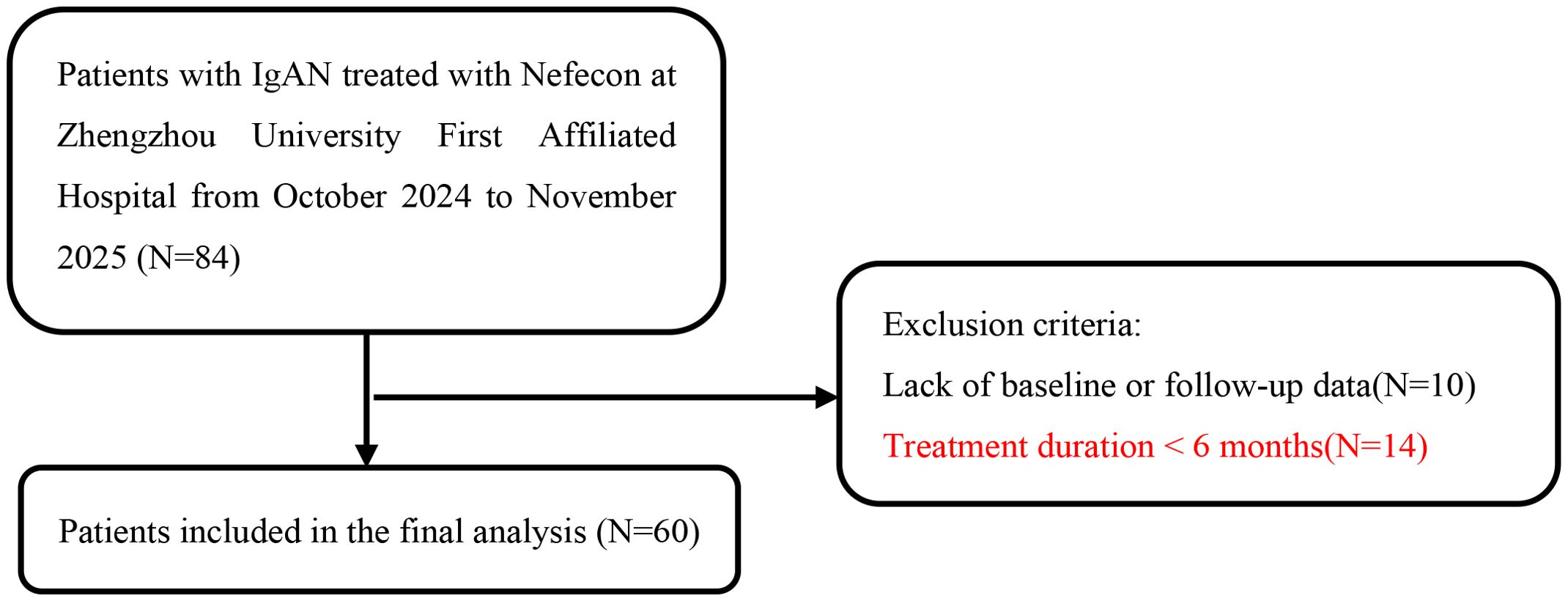

At the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, this retrospective study involved 84 patients with biopsy-confirmed IgA nephropathy who were treated with Nefecon between October 2024 and November 2025. The inclusion criteria included: (1) Primary IgAN verified through renal biopsy; (2) Age between 18 and 70 years; (3) The proteinuria was at least 0.5 g/d and eGFR of at least 25 mL/min/1.73m² at Nefecon treatment initiation; (4) Daily oral administration of 16 mg Nefecon. Exclusion criteria include: (1) absence of baseline or follow-up data; (2) treatment duration of less than 6 months. A total of 60 IgAN patients treated with Nefecon were included (Figure 1). The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki Guidelines and was approved by the medical ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University (number. 2025-KY-0919).

Data collection

Baseline characteristics encompassed age, gender, body mass index (BMI), presence of diabetes and hypertension, mean arterial pressure (MAP), proteinuria, albumin, eGFR, serum creatinine, and uric acid (UA). Proteinuria was measured using 24-hour proteinuria at all time points for all patients. eGFR was calculated using the CKD-EPI formula (9). Proteinuria and eGFR were recorded at each follow-up. Data on medications, such as glucocorticoids, immunosuppressants, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors (RAASi), and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, were documented.

Renal biopsy specimens were scored using the Oxford MEST-C classification (10, 11) (M: mesangial hypercellularity; E: endocapillary hypercellularity; S: segmental glomerulosclerosis; T: tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis; C: crescents).

Outcomes and follow-up

Primary outcomes were changes in proteinuria and eGFR during follow-up. Secondary outcomes encompassed the cumulative frequency of patients achieving a 50% reduction in proteinuria, along with subgroup analyses based on varying treatment regimens, baseline proteinuria levels, and renal function. Baseline (time 0) is defined as the initiation of Nefecon treatment. All subsequent data were revised as of November 30, 2025.

Safety endpoints were the incidence of adverse events (AEs), including hypertension, peripheral edema, muscle spasms, acne, headache, respiratory infections, glucose intolerance, and abnormal liver function. Severe adverse events (SAEs) were defined as all-cause death and other life-threatening conditions requiring hospitalization.

Statistical analysis

Categorical data were expressed as numbers and percentages. Continuous data with normal distribution were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), while non-normally distributed data were reported as median and interquartile range. Group differences were analyzed using the independent-samples t-test for data with normal distribution and the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test for data without normal distribution. Temporal variations in variables were assessed using the paired-samples t-test for data with normal distribution and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for data without normal distribution. For the subgroups with a small sample size (eGFR < 35 mL/min/1.73 m²), we employed exploratory analysis and noted that the statistical power of these analyses was relatively low and needed to be verified in a larger sample group. SPSS 27.0 software facilitated the statistical analysis. Statistical tests were conducted as two-tailed, with significance set at p < 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of study population

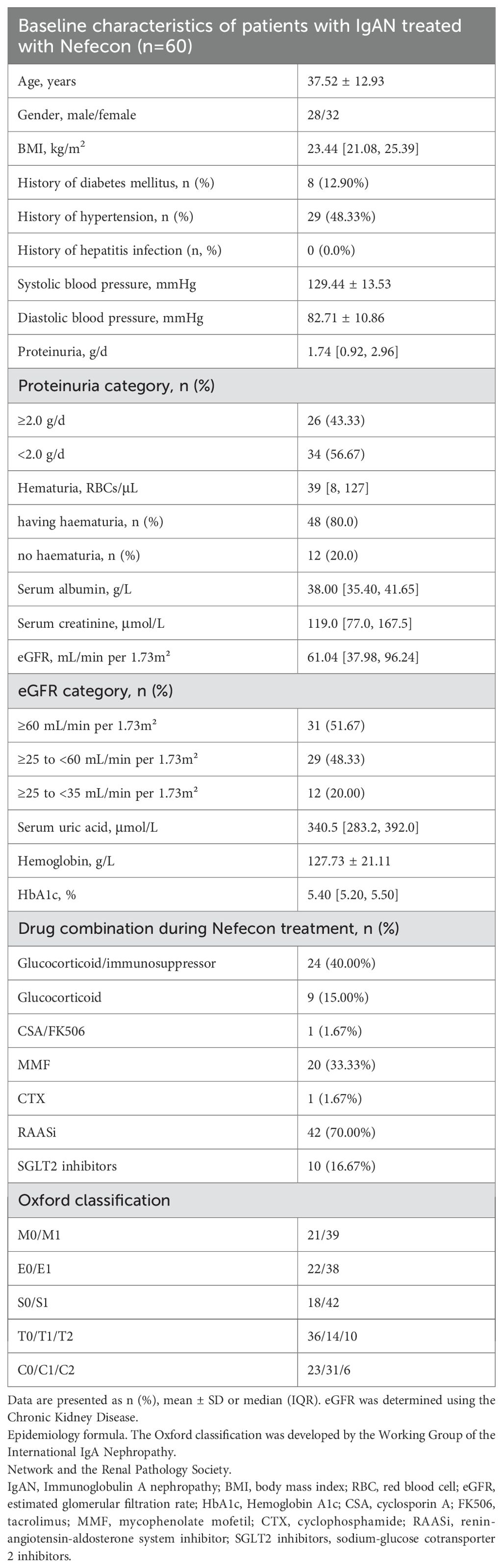

From October 2024 to November 2025, 60 IgAN patients treated with Nefecon were included. The time between IgAN diagnosis and the start of Nefecon treatment was 24 months, with a range of 1 to 60 months. Patients were monitored bi-monthly, with a median follow-up duration of 4 [2, 6] months. Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics. The mean age was 37.52 years, 47% were male, and the mean BMI was 23.44 kg/m².Initial proteinuria measured 1.74 [0.92, 2.96] g/day, while the baseline eGFR was 61.04 [37.98, 96.24] mL/min/1.73 m².

Treatment regimens

All patients received treatment with Nefecon at a dose of 16mg. The expected duration of Nefecon treatment was 9 months. 24 (40.00%) patients were also given Glucocorticoid/immunosuppressor therapy, 42 (70.00%) patients were given RAASi therapy, and 10 (16.67%) patients were given SGLT2i therapy, with the dosage being the maximum or tolerated dose.

Primary outcomes

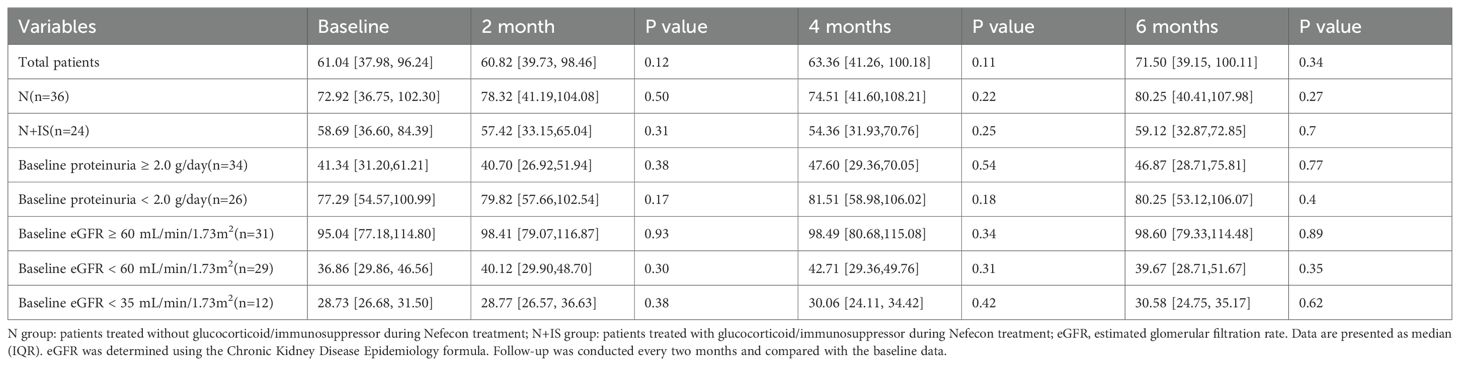

The changes in proteinuria and eGFR over time are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Change of proteinuria and eGFR during follow-up period. Data are expressed as median, upper quartile, and lower quartile. Follow-up was conducted every two months and compared with the baseline data. eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

At month 2, the proteinuria decreased from 1.74 [0.92, 2.96] to 1.62 [0.77, 2.72] g/day, with a reduction rate of 16.6% [-37.7, 39.9] (p=0.24). At month 4, the proteinuria dropped to 1.22 [0.65, 2.03] g/day, representing a reduction rate of 31.9% [-15.5, 48.1] (p<0.001). At month 6, the proteinuria decreased to 0.91 [0.31, 1.44] g/day (p<0.001), with a reduction rate of 43.5% [15.5, 68.3]. A statistically significant reduction in proteinuria was observed after 4 months of treatment.

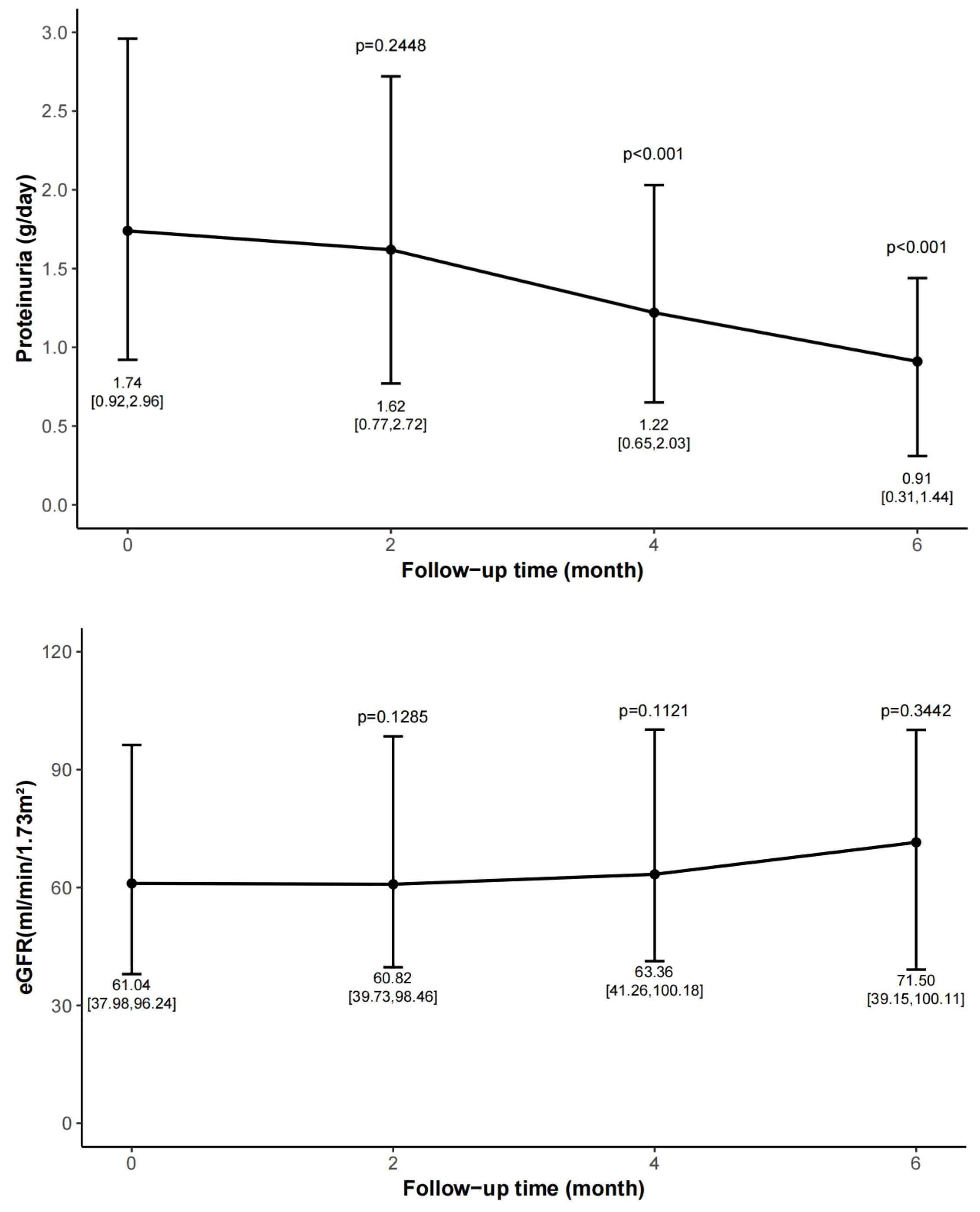

The eGFR remained stable throughout the follow-up period. The eGFR measured at 2, 4, and 6 months were 60.82 [39.73, 98.46] mL/min/1.73 m² (p=0.12 vs. baseline), 63.36 [41.26, 100.18] mL/min/1.73 m² (p=0.11 vs. baseline), and 71.50 [39.15, 100.11] mL/min/1.73 m² (p=0.34 vs. baseline), respectively.

Secondary outcomes

In 24 patients (40.00%), the reduction in proteinuria exceeded 50%, and in 19 patients (31.67%), proteinuria decreased to less than 0.5 g/day.

Subgroup analyses

According to whether the patients received glucocorticoid/immunosuppressor treatment during the treatment with Nefecon, the patients were further divided into the Nefecon group (Group N, n=36, 60.00%) and the Nefecon plus glucocorticoid/immunosuppressor group (Group N+IS, n=24, 40.00%). Baseline proteinuria (1.62 [0.90, 2.49] vs. 2.39 [1.66, 3.57] g/day, p=0.13) and eGFR (72.92 [36.75, 102.30] vs. 58.69 [36.60, 84.39] mL/min/1.73 m², p=0.17) levels showed no significant differences between the groups.

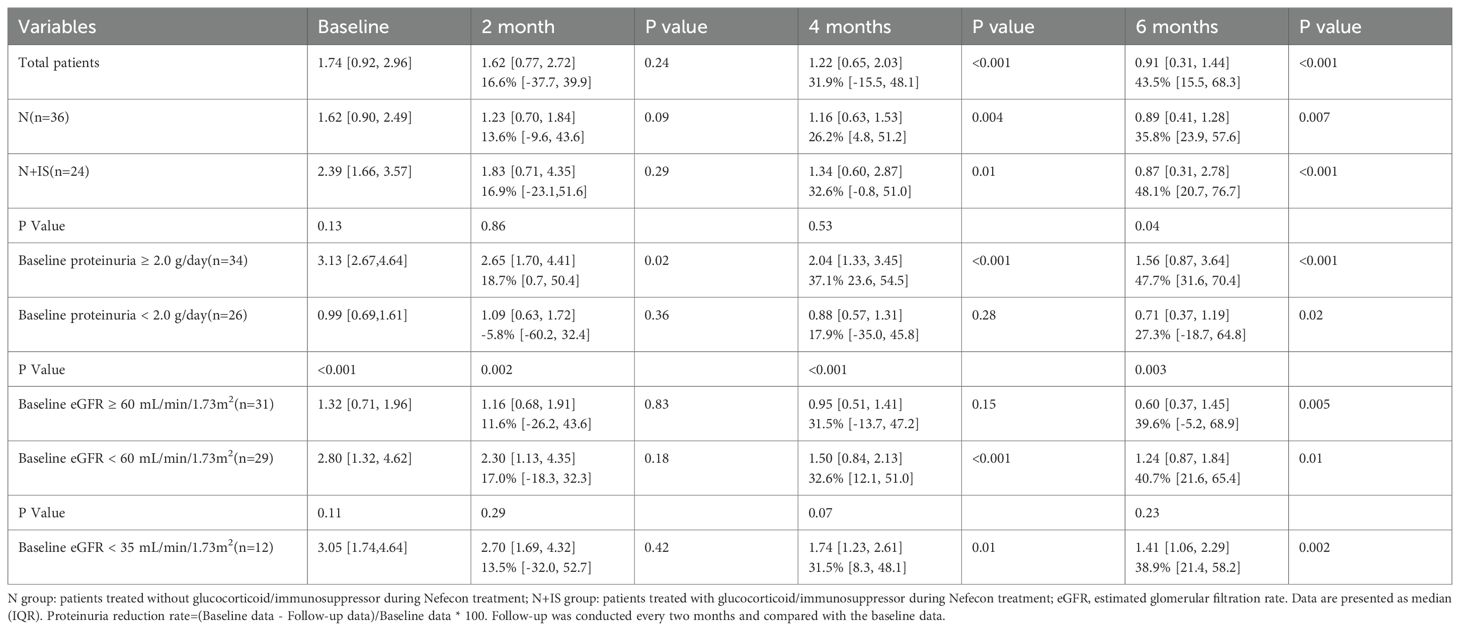

The changes in proteinuria and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) over time in the two groups are presented in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. After 4 months of follow-up, proteinuria levels decreased significantly in both groups. At month 4, proteinuria in Group N decreased to 1.16 [0.63, 1.53] g/day (p=0.004), whereas that in Group N+IS decreased to 1.34 [0.60, 2.87] g/day (p=0.01). After 6 months, the reduction rate of proteinuria in Group N+IS was more pronounced (48.1% [20.7, 76.7] vs. 35.8% [23.9, 57.6], p=0.04) (Table 2). In addition, eGFR levels remained stable over time in both groups (Table 3).

Table 2. Proteinuria (g/d) and proteinuria reduction rate (%) during treatment compared with baseline data.

Subgroup analyses were conducted based on baseline proteinuria levels (<2.0 vs. ≥2.0 g/d) and eGFR categories (≥60 vs. <60 mL/min/1.73 m²). The group with baseline proteinuria ≥2.0 g/d showed a significantly greater reduction in proteinuria (47.7% [31.6, 70.4] vs. 27.3% [-18.7, 64.8], p=0.003), whereas no significant difference was observed in proteinuria reduction between groups with varying baseline eGFR levels (39.6% [-5.2, 68.9] vs. 40.7% [21.6, 65.4], p=0.23) (Table 2).

Among 12 patients with a baseline eGFR < 35 mL/min/1.73 m², proteinuria decreased by 38.9% [21.4, 58.2] (p=0.002) during treatment (Table 2), while eGFR levels remained stable (Table 3). For this subgroup, we employed exploratory analysis and indicated that the statistical power of these analyses was relatively low and required validation in a larger sample group.

Adverse events related to Nefecon

Most patients tolerated Nefecon well. The blood sugar control was stable (the HbA1c at baseline was 5.40%, and at 6 months it was 5.53%, p = 0.32), and no new diabetes cases occurred; the blood pressure was well controlled (systolic/diastolic blood pressure: at baseline it was 129.44/82.71 mmHg, and at 6 months it was 127.36/80.58 mmHg, p > 0.05); and there were no severe infections (only 4 cases of upper respiratory tract infections, accounting for 6.7%). No serious adverse events (AEs) were reported. Mild AEs included acne (13.3%), weight gain (11.7%), facial swelling (10.0%), fatigue (8.3%), limb pain (6.7%), hypertension (6.7%), menstrual disorders (6.7%), elevated blood sugar (5.0%), peripheral edema (5.0%), and hirsutism (3.3%). No one has stopped using Nefecon because of AEs.

Discussion

The exact mechanisms underlying IgAN remain unclear. Emerging evidence suggests that the intestinal mucosal immune system and mucosal-derived Gd-IgA1 play a role in the pathogenesis of primary IgAN. In IgAN patients, elevated circulating Gd-IgA1 levels lead to autoantibody production and immune complex formation, which deposit in the glomerular mesangium. This activates the complement alternative or lectin pathways and inflammatory responses, resulting in kidney damage (4, 12). Nefecon acts on Peyer’s patches in the terminal ileum to decrease the production of Gd-IgA1 at its origin. The 2025 KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Immunoglobulin A Nephropathy (IgAN) and Immunoglobulin A Vasculitis (IgAV) advises using Nefecon for IgAN patients at risk of disease progression (8). The NefIgArd Phase III trial demonstrated that Nefecon significantly reduces proteinuria in IgAN patients with eGFR>35 mL/min/1.73 m², while maintaining stable renal function and exhibiting no serious adverse reactions (6, 7).

Our research offers real-world evidence supporting the efficacy and tolerability of Nefecon in IgAN patients, supplementing findings from controlled clinical trials. Consistent with the NEFIGAN and NefIgArd trials, a significant reduction in proteinuria was observed after 4 months of follow-up, with median reduction rates of 31.9% at 4 months and 43.5% at 6 months. During the treatment process, although there was no statistical difference, eGFR did show an improvement.

Furthermore, our study extends these findings to patient groups often excluded from RCTs. First, we demonstrated that concomitant use of Nefecon with glucocorticoids or immunosuppressants produced greater reductions in proteinuria compared to Nefecon alone. This suggests an exploratory finding through complementary mechanisms — while Nefecon targets mucosal IgA production, immunosuppressants act on systemic immune pathways. Secondly, we noted advantages in patients with severe renal impairment (eGFR <35 mL/min/1.73 m²), a group previously excluded from key trials. In these patients, Nefecon reduced proteinuria without accelerating renal decline, consistent with recent retrospective reports (13), and underscoring its potential value even in late-stage disease.

Finally, 18 patients did not receive RAASi during Nefecon treatment. Potential reasons include 8 patients having a baseline eGFR below 30 mL/min/1.73 m², 2 patients experiencing rapid renal function decline, and 8 patients showing intolerance to blood pressure.

The N+IS subgroup exhibited heterogeneity in immunosuppressive regimens, We recognize that these factors introduce residual confounding that cannot be fully eliminated in a retrospective study. Thus, the observed greater proteinuria reduction in the N+IS group should be interpreted with caution. We emphasize that this potential additive benefit is preliminary and hypothesis-generating, not definitive evidence of synergy. To validate these findings, future prospective trials with standardized immunosuppressive protocols and rigorous randomization to treatment arms are essential. Such studies will better control for confounding variables and clarify whether the observed additive effect is truly attributable to the combination therapy or confounded by baseline disease severity and regimen heterogeneity.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting our findings. The study’s retrospective, single-center design and limited sample size restrict its generalizability. The absence of a control group and short follow-up duration preclude firm conclusions regarding long-term renal function preservation (stable eGFR during follow-up). Moreover, we did not assess biomarker changes such as serum Gd-IgA1, which could provide mechanistic insights. We explicitly emphasize that the study’s findings are exploratory and hypothesis-generating, rather than definitive evidence of causal relationships. A multi-center prospective controlled trials with a large sample size and extended follow-up is necessary to confirm Nefecon’s clinical efficacy.

Conclusion

In summary, this study fills an important knowledge gap by evaluating Nefecon in real-world Chinese IgAN patients, including high-risk groups often excluded from trials. The findings underscore Nefecon’s safety and efficacy as a therapeutic option, with exploratory evidence of potential additive benefits when combined with immunosuppressants. These results are hypothesis-generating, suggesting the need for future multicenter studies with extended follow-up to validate its long-term advantages and establish optimal combination strategies.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the medical ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University (number. 2025-KY-0919). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The human samples used in this study were acquired from primarily isolated as part of your previous study for which ethical approval was obtained. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

ZZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZH: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Software, Writing – original draft. LW: Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. LY: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. RG: Data curation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. YW: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. QL: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing. YG: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. LT: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This project was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 82370727) and the “Three Hundred” Special Program for Clinical Research-oriented Doctors in Henan Province (grant no. HNCRD202421).

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the support from the Renal Pathology Laboratory at the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Zhang H and Barratt J. Is IgA nephropathy the same disease in different parts of the world? Seminars in Immunopathology. Seminars in Immunopathology. (2021) 43(5)707–715. doi: 10.1007/s00281-021-00884-7

2. Tang C, Chen P, Si FL, Lv JC, Shi SF, Zhou XJ, et al. Time-varying proteinuria and progression of IgA nephropathy: A cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. (2024) 84:170–178.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2023.12.016

3. Pitcher D, Braddon F, and Wang BHMOASSWNT. Long-term outcomes in IgA nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol: CJASN. (2023) 18:727–38. doi: 10.2215/CJN.0000000000000135

4. Barratt J, Rovin BH, Cattran D, Floege J, Lafayette R, Tesar V, et al. Why target the gut to treat IgA nephropathy? Kidney Int Rep. (2020) 5:1620–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2020.08.009

5. Fellstrom BC, Barratt J, Cook H, Coppo R, Feehally J, De Fijter JW, et al. Targeted-release budesonide versus placebo in patients with IgA nephropathy (NEFIGAN): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial. Lancet. (2017) 389:2117–27. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30550-0

6. Lafayette R, Kristensen J, Stone A, Floege J, Tesar V, Trimarchi H, et al. Efficacy and safety of a targeted-release formulation of budesonide in patients with primary IgA nephropathy (NefIgArd): 2-year results from a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet. (2023) 402:859–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01554-4

7. Zhang H, Lafayette R, Wang B, Ying L, Zhu ZY, Stone A, et al. Efficacy and safety of nefecon in patients with IgA nephropathy from Mainland China: 2-year NefIgArd trial results. Kidney360. (2024) 5:1881–92. doi: 10.34067/KID.0000000583

8. Floege J, Barratt J, Cook HT, Noronha IL, Reich HN, Suzuki Y, et al. Executive summary of the KDIGO 2025 clinical practice guideline for the management of immunoglobulin A nephropathy (IgAN) and immunoglobulin A vasculitis (IgAV). Kidney Int. (2025) 108:548–54. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2025.04.003

9. Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, Feldman HI, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. (2009) 150:604–12. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006

10. Cattran DC, Coppo R, Cook HT, Feehally J, Roberts ISD, Troyanov S, et al. The Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy: rationale, clinicopathological correlations, and classification. Kidney Int. (2009) 76:534–45. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.243

11. Trimarchi H, Barratt J, Cattran DC, Cook HT, Coppo R, Haas M, et al. Oxford Classification of IgA nephropathy 2016: an update from the IgA Nephropathy Classification Working Group. Kidney Int. (2017) 91:1014. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.02.003

12. Yeo SC, Cheung CK, and Barratt J. New insights into the pathogenesis of IgA nephropathy. Pediatr Nephrol: J Int Pediatr Nephrol Assoc. 2018. 33:763–77. doi: 10.1007/s00467-017-3699-z

Keywords: CKD progression, EGFR, IgA nephropathy, Nefecon, proteinuria

Citation: Zhai Z, Huang Z, Wang L, Yu L, Gou R, Wang Y, Li Q, Guo Y and Tang L (2026) Efficacy and safety of Nefecon in IgA nephropathy: real world clinical practice. Front. Immunol. 17:1761804. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2026.1761804

Received: 06 December 2025; Accepted: 21 January 2026; Revised: 20 January 2026;

Published: 05 February 2026.

Edited by:

Wu Liu, Capital Medical University, ChinaReviewed by:

Xavier Fulladosa, Bellvitge University Hospital, SpainXiao Li, Shandong Provincial Qianfoshan Hospital, China

Copyright © 2026 Zhai, Huang, Wang, Yu, Gou, Wang, Li, Guo and Tang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lin Tang, dGFuZ2xpbkB6enUuZWR1LmNu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Zihan Zhai

Zihan Zhai Zhibin Huang

Zhibin Huang Liuwei Wang

Liuwei Wang Lu Yu

Lu Yu Rong Gou

Rong Gou Yulin Wang

Yulin Wang Qiuhong Li

Qiuhong Li Yanhong Guo

Yanhong Guo Lin Tang

Lin Tang