Abstract

With global viral emergence and increasing antiviral resistance, there is an urgent need for innovative immunomodulatory strategies. Gut microbiota modulation has gained attention as a promising therapeutic approach. Clostridium butyricum (C. butyricum) plays a pivotal role in shaping microbial composition, preserving intestinal barrier integrity, and enhancing mucosal immunity. Its major metabolites, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), further strengthen mucosal defenses and exert antiviral and anti-inflammatory effects. This review proposes a unified “gut-centric hypothesis” that intestinal barrier integrity, microbial homeostasis, and mucosal immune balance collectively determine the host’s resilience to viral invasion and inflammation. The collective findings delineate a mechanistic axis whereby C. butyricum orchestrates antiviral and anti-inflammatory immunity through the induction of type I/III interferons, modulation of inflammasome signaling, and expansion of regulatory immune populations, reinforcing its therapeutic promise. This review provides a new conceptual framework linking probiotic action to antiviral immunity, identifying C. butyricum as a potential next-generation microbial therapeutic for viral and inflammatory diseases.

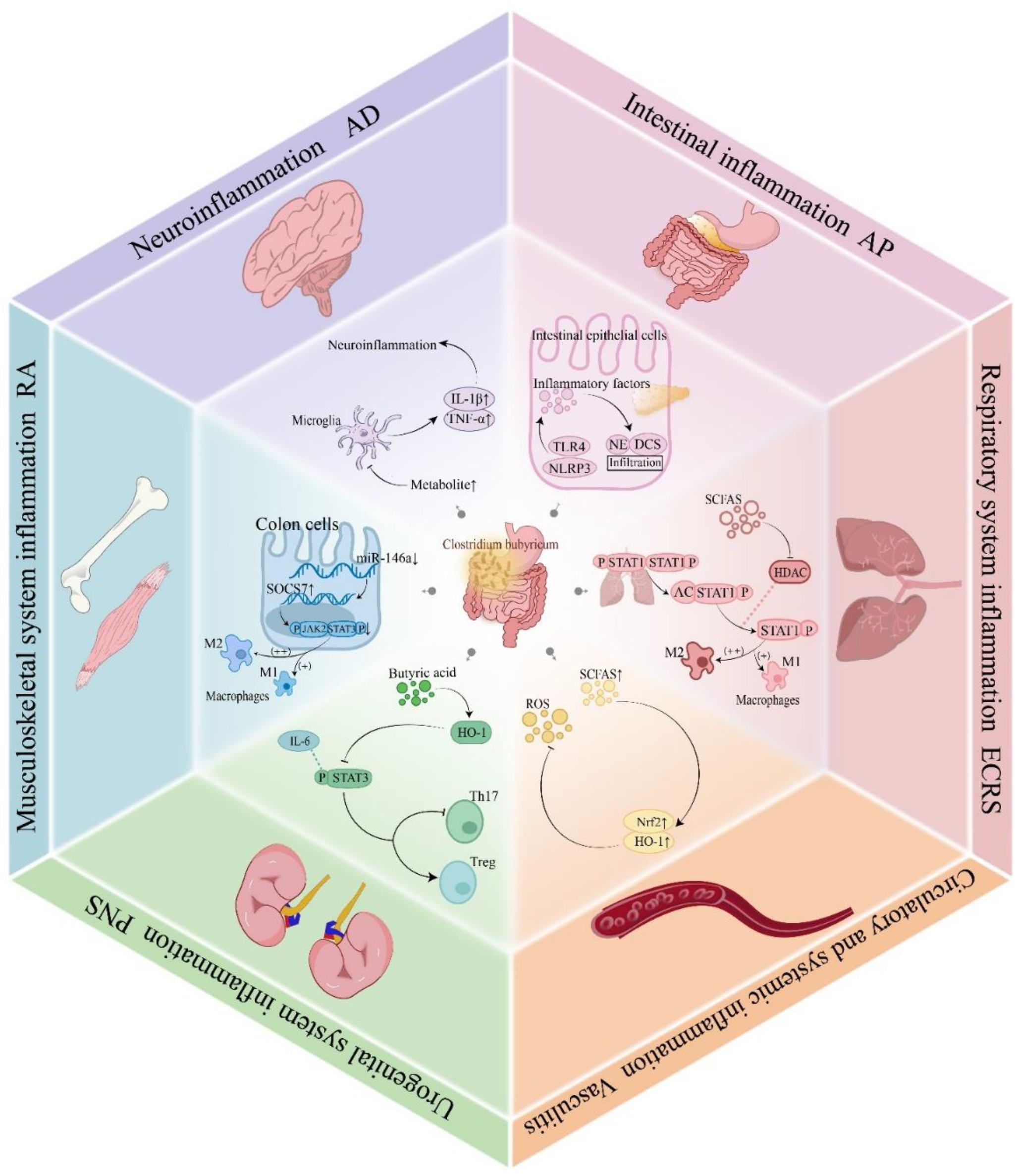

Graphical Abstract

1 Introduction

Clostridium butyricum, an anaerobic bacterium that produces butyrate and forms spores, is vital for gut health. Prazmowski first isolated it from the intestinal tract of pigs in 1880 due to its unique metabolic properties (1). C. butyricum produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) via the butyrate kinase (buk) pathway, which are primary metabolites formed by the bacterial fermentation of dietary fiber in the gut (1, 2). These metabolites protect intestinal health and promote bile acid metabolism, influencing the host’s health status (3). As a key probiotic, C. butyricum is widely used in Japan, South Korea, China, and other regions. It plays a crucial role in balancing gut microbiota, enhancing immunity, and preventing gut-related diseases (1).

Recent interest has grown in the potential of C. butyricum and SCFAs in combating viruses and alleviating inflammation. The gut, as the body’s largest immune organ, maintains mucosal immune homeostasis, defends against external threats, and oversees self-surveillance. C. butyricum modulates the activity of mucosal immune cells and inflammatory factors, alleviating inflammatory responses and enhancing defense against viral infections. It strengthens the body’s ability to defend against pathogens and fosters immune tolerance. Additionally, C. butyricum directly combats viral infections by inhibiting viral invasion and replication. SCFAs primarily exert effects through gene and protein regulation, suppressing histone deacetylases to modulate virus-related gene expression and enhance interferon production. By activating G-protein-coupled receptors, they refine the functions of intestinal dendritic cells, macrophages, and other immune cells, amplifying both antiviral and anti-inflammatory responses, thus playing a pivotal role in mucosal immunity.

This review proposes the “gut-centric hypothesis”, highlighting the role of C. butyricum in regulating gut immunity. C. butyricum is a promising drug target that enhances intestinal barrier function and modulates type I/III interferon responses, providing strategies against emerging viruses. Its dual activity in antiviral and anti-inflammatory responses underscores its potential in clinical treatments. This research offers a new perspective for foundational studies in mucosal immunology and has broad applications in developing interventions for mucosal immunity, addressing viral infections, and treating inflammatory diseases.

While C. butyricum’s role in gut immunity has been noted, several areas require further exploration. This review addresses critical gaps: the mechanisms of C. butyricum in gut mucosal immunity, its specific applications in viral infections and inflammatory diseases, and its potential as an antiviral and anti-inflammatory therapeutic bacterium.

2 Antiviral functions and inflammation alleviation of C. butyricum and its key metabolites

C. butyricum is known for its production of SCFAs and its ability to adjust host immune and metabolic functions. This review explores how C. butyricum and its SCFAs induce intestinal mucosal immunity in antiviral defense and alleviate inflammation, focusing on their effects on gut microbiota, barrier function, immune regulation, inflammatory signaling pathways, and antiviral responses.

2.1 C. butyricum and its key metabolites regulate gut microbiome

As a probiotic, C. butyricum’s primary function is to regulate intestinal health. It modulates intestinal mucosal immunity by influencing gut microbiota and enhancing its defensive function. It promotes the growth of beneficial bacteria, especially those with high butyryl-CoA gene content, and inhibits pathogenic species proliferation (4). SCFAs lower the pH in the intestinal lumen, inhibit harmful bacteria proliferation, and optimize microbiome structure (4). The increase in Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium was observed in mouse models supplemented with C. butyricum, further validating their role in regulating the gut ecosystem. C. butyricum regulates bile acid levels to inhibit the proliferation and cytotoxin production of Clostridioides difficile. It also competes with Helicobacter pylori for adhesion sites on gastric epithelial cells, effectively suppressing its growth (5, 6). Furthermore, C. butyricum significantly inhibits multiple pathogenic bacteria, including Staphylococcus aureus, Vibrio cholerae, Shigella flexneri, and Salmonella spp, by secreting antimicrobial peptides (7–10). It also prevents infections caused by enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (7).

On a molecular level, C. butyricum modulated gut microbiota structure by inhibiting Wnt/β-catenin pathways (9). This resulted in two primary outcomes: inhibition of pathogenic bacteria and bile acid-metabolizing strains, and increased proliferation of SCFA-producing microbial communities.

2.2 C. butyricum and its key metabolites modulate the intestinal barrier

The intestinal barrier is essential for mucosal immunity. When the barrier is compromised, bacteria and toxins can enter the bloodstream, triggering autoimmune and inflammatory responses. C. butyricum and its metabolites enhance intestinal barrier function, preventing pathogens from penetrating the intestinal epithelium and strengthening mucosal immune defense. Butyric acid, the primary energy source for intestinal epithelial cells, promotes metabolism and repair, enhances stress tolerance, and stabilizes barrier function (1). SCFAs upregulated tight junction proteins such as ZO-1, occludin, and cadherin by inducing local hypoxia and activating hypoxia-inducible factor, reinforcing intercellular junctions (11, 12). Additionally, SCFAs improved the transmembrane resistance of epithelial cells by activating the AMPK pathway and reducing apoptosis via the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway (13). Butyrate also stimulated mucin secretion in goblet cells and activate the MAPK pathway, contributing to improved infection resistance (14).

2.3 Gut-immune axis: C. butyricum and its key metabolites regulate immune cell differentiation and function

The gut-immune axis connects gut microbiota, the intestinal immune system, and systemic immune responses. C. butyricum influences the intestinal mucosal immune response against viruses and inflammation by modulating T cells, B cells, and dendritic cells function and differentiation. It promotes regulatory T cells differentiation, and modulates T and B cell function. Administration of C. butyricum in mouse models significantly enhanced Treg differentiation and abundance. SCFAs promoted Treg differentiation and stimulated IL-22 production by CD4+T cells via G protein-coupled receptor 41 and HDAC function, boosting immune modulation (15, 16). These findings indicate that SCFAs contribute to anti-infection immunity by influencing T-cell differentiation. SCFAs also directly modulated T-cell differentiation and participated in cell-specific immunity. Butyrate did not inhibit FoxP3+ T cells but impeded the proliferation of CD4+ T cells, likely due to its immunomodulatory specificity or ability to regulate genes associated with lymphocyte differentiation (17). Additionally, butyrate enhanced immunomodulation by combining GPR43-induced granzyme B (GZMB) (18).

C. butyricum significantly impacts B-cell maturation. SCFAs promote metabolic pathways, including acetyl-coenzyme A biosynthesis, oxidative phosphorylation, glycolysis, and fatty acid biosynthesis (19). As an HDAC inhibitor, SCFAs upregulate the genes related to B-cell differentiation, such as Aicda and Prdm1, thereby supporting B-cell differentiation and maturation (19). This reduces circulating IgE levels, alleviating allergic reactions while supporting antibody production and adaptive immune responses (20). SCFAs also regulate the intestinal mucosal immune response by modulating the differentiation, maturation, and activation of various immune cells, including dendritic cells, macrophages, and T cells, through the TLR2 pathway. By inhibiting HDAC activity, SCFAs induce the production of B10 cells with anti-inflammatory functions. These mechanisms are crucial for maintaining intestinal mucosal immune homeostasis and combating inflammation.

2.4 C. butyricum and its key metabolites modulate inflammation-related pathways

Inflammatory factors play a critical role in intestinal mucosal immunity. C. butyricum modulates the intestinal immune response by regulating inflammatory factor expression, preventing excessive inflammation, and protecting the gut from pathogen invasion. C. butyricum and SCFAs regulate inflammatory factors through the NF-κB and TLR4 signaling pathways. The inflammatory process is key in the onset and progression of many pathological conditions. Activating TLR4 enhances anti-inflammatory cytokines generation, such as IL-10, while inhibiting pro-inflammatory mediators like IL-1β and IL-6. C. butyricum facilitates retinol metabolism, increasing retinoic acid levels to further alleviate inflammatory responses (21). By promoting prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) synthesis and inhibiting matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) expression, SCFAs improve infection-induced immunopathological states (22). Inhibiting mast cell degranulation also alleviates respiratory inflammation and reduces tissue damage.

SCFAs significantly decrease the release of pro-inflammatory chemokines, including CCL3, CCL4, CCL5, CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11, impairing immune cell migration to inflammation sites. Butyrate reduces LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine expression by inhibiting key TLR4 pathway molecules, such as TRAF6, TRAF3, and IRF3 (23–26). Butyric acid also reduces NF-κB activation by downregulating TRAF6, further inhibiting pro-inflammatory cytokines transcription.

2.5 C. butyricum and its key metabolites interact with viruses and inflammatory processes

The mucosal immune system combats pathogens entering the body. C. butyricum and its metabolites activate intestinal mucosal immune responses, enhancing the gut’s defense against viruses while modulating inflammation. C. butyricum promotes interferon production, activates the NF-κB pathway to inhibit inflammatory signaling molecules, and replicates various RNA and DNA viruses (27, 28). Furthermore, C. butyricum’s antiviral and anti-inflammatory effects depend on the key components within its metabolites—SCFAs. These limit viral spread by regulating JAK and IRF pathways and inhibiting endothelial cell adhesion molecule expression, thereby enhancing host immune defense (29, 30). They also modulate intestinal immune cells to inhibit inflammation and maintain host immune homeostasis.

3 Antiviral mechanisms of C. butyricum and its key metabolites

3.1 Influenza virus

Influenza viruses are classified into four types based on nucleoproteins and matrix proteins: A, B, C, and D (31). The subtypes of Influenza A that primarily infect humans are H1N1 and H3N2, while the lineages of Influenza B viruses are Victoria and Yamagata. Recently, C. butyricum has gained attention as an agent against influenza viruses.

Oral administration of C. butyricum alleviated inflammation caused by the influenza virus in a murine model, potentially due to FFAR3 and fatty acid β-oxidation pathway stimulation that enhances CD8+ T cells activity (32). C. butyricum can directly modulate intestinal mucosal immunity, enhancing the antiviral activity of CD8+T cells by binding to GPR43 and inducing Acetyl-CoA production (33). These processes increase oxidative phosphorylation, glycolysis, and other metabolic functions. Interferons play a central role in the intestinal mucosal immune response. C. butyricum upregulates IFN-λ production by inducing the ω-3 fatty acid 18-hydroxy eicosapentaenoic acid (18-HEPE), which activates G protein-coupled receptor 120(GPR120) and interferon regulatory factors (IRF-1 and IRF-7) (34, 35). IFN-λ interacts with the IFNLR1 on the cell surface to activate the JAK-STAT pathway, initiating antiviral gene expression. The proteins encoded by these genes inhibit viral replication and prevent viral assembly and release. Additionally, IFN-λ inhibits macrophage infection and enhances the host immune response (36). The Acetate-GPR43-NLRP3-MAVS-IFN-I pathway was proposed as a potential target for treating respiratory viral infections (37). (Figure 1) Acetate salts can also elevate IFN-β levels, enhancing antiviral capabilities (38). The inhibitory effect of butyrate on the influenza virus was confirmed by a positive correlation between butyrate levels and lymphocyte ratio, as well as MxA(GPR120) expression, and negatively with viral load (39). Acetate also reduced influenza viral load by enhancing anti-inflammatory mediators.

Figure 1

Mechanisms of C. butyricum against the influenza virus. Oral administration of C. butyricum in mice induces the production of ω-3 fatty acid 18-hydroxy eicosapentaenoic acid (18-HEPE), which activates GPR120 and IRF-1/-7, promoting the production of IFN-λ in lung epithelial cells and enhancing the ability to combat influenza. The metabolite acetate binds to GPR43, promoting CD8+ T cell generation and stimulating GZMB secretion. Through binding with the GPR43 receptor and in the presence of NLRP3, acetate enhances the virus RNA-triggered MAVS aggregation, promoting IRF3 activation and IFN-I production, thereby inhibiting the influenza virus spread.18-HEPE: 18-hydroxy-eicosapentaenoic acid; GPR120, G protein-coupled receptor 120; IRF-1/-7, Interferon regulatory factors 1/-7; IFN-λ, Interferon-λ; GPR43, G protein-coupled receptor 43; CD8+ T cells, CD8+ T lymphocytes; GZMB, Granzyme B; NLRP3, NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing protein 3; MAVS, Mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein; IRF3, Interferon regulatory factor 3; IFN-I, Type I interferons.

3.2 SARS-CoV-2

SARS-CoV-2, a respiratory virus, also impacts the gastrointestinal tract. The metabolites of C. butyricum are crucial in combating SARS-CoV-2 infection. SARS-CoV-2 infection causes a leaky gut and systemic inflammation. Butyrate, an energy source for intestinal epithelial cells, restores intestinal barrier integrity by promoting tight junction proteins like Claudin-1 and Occludin. It enhances intestinal barrier function and boosts immune defense against viruses by promoting Mucin and antimicrobial peptide secretion from goblet cells (40). Clinical research confirms that calcium butyrate improves gut microbiota dysbiosis in SARS-CoV-2 patients, reduces secondary infections, and decreases virus-induced respiratory damage (41).

SARS-CoV-2 infections often involve a cytokine storm, releasing large amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines and causing systemic inflammation (42). Butyrate impeded the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines by binding to the G protein-coupled receptor 109a(GPR109a), activating regulatory Tregs and inhibiting overactive T cell responses (16, 40, 43), thus regulating intestinal mucosal immunity and alleviating systemic inflammation.

It also activates M2-type macrophages, increasing the anti-inflammatory factor IL-10 and decreasing pro-inflammatory factor IL-6 levels. Additionally, propionate inhibits the overactivation of pro-inflammatory signaling pathways and HDAC activity, attenuating the cytokine-mediated systemic inflammatory response.

Butyrate and acetate inhibit viral replication and enhance host immunity through various mechanisms. Butyrate hinders SARS-CoV-2 binding to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor by upregulating Adam17, which prevents the virus from entering host cells (43, 44), thereby enhancing the defensive function of the intestinal immune system. Besides, butyrate directly inhibited SARS-CoV-2 replication by downregulating HMGB1 expression (43). Additionally, it also upregulated the intracellular expression of IRF7 and interferon receptor through calmodulin phosphatase-binding protein-1 and the TLR signaling pathway, enhancing host resistance to the virus (45, 46). Acetate stimulated B cells to produce specific antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, further inhibiting virus transmission (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Mechanisms of C. butyricum-derived butyrate against SARS-CoV-2. In lung epithelial cells, butyrate upregulates t Adam17, inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 binding to the ACE-2 receptor and preventing viral entry. It also regulates Treg cells via the GPR109a receptor, suppressing excessive T-cell activation and reducing inflammatory factors IL-10 and IL-18. In intestinal epithelial cells, butyrate promotes mucus (Mucins) and antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) secretion by goblet cells, protecting the intestinal barrier. Adam17, A disintegrin and metalloproteinase 17; ACE-2, Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; GPR109a, G protein-coupled receptor 109a; Treg, Regulatory T cells; IL-10, Interleukin-10; IL-18, Interleukin-18; Mucins, Mucins; AMPs, Antimicrobial peptides.

3.3 Human immunodeficiency virus

HIV is a global public health concern due to its immunoinhibition and destruction of CD4+T cells. Although antiretroviral therapy(ART) can inhibit viral load effectively, complete eradication of HIV remains challenging. C. butyricum has gained attention for its ability to modulate intestinal immunity and inflammatory response.

C. butyricum inhibits microbial translocation due to HIV infection by reducing harmful bacteria. It replenished lost CD4+ T cells after HIV infection, which enhanced intestinal immune function (47). SCFAs, which are the key metabolites, also play an important role in immune response. Specifically, propionate mitigated HIV-induced immune system destruction through Th1 and Th17 cell inhibition and facilitates regulatory Treg development, preserving immune homeostasis and reducing chronic inflammation. Acetate reduced inflammation by inhibiting neutrophil migration (48). Additionally, C. butyricum induces the production of type I interferon and increases the expression of antiviral proteins. For example, APOBEC family proteins and bone marrow stromal antigen 2 (BST-2) proteins inhibited HIV replication through gene mutation and inhibiting viral release. Type I interferon not only counteracted the HIV-mediated immune escape response but also enhanced the antiviral response of plasmacytoid dendritic cells (PDCs). This improves the immune response in HIV-infected patients.

However, C. butyricum also exerts a detrimental effect on HIV. Butyrate may accelerate the progression of HIV infection by inhibiting HDAC activity and promoting HIV-1 gene expression. Furthermore, acetate significantly decreased the release of α-defensin, an active anti-HIV molecule, in older women, weakening the immune system’s ability. Thus, the influence of C. butyricum on HIV is dual: it modulates intestinal immunity and induces interferon production, while potentially promoting viral progression under certain conditions.

3.4 Herpes simplex virus type 2

Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 is a common pathogen that causes recurring diseases. As a beneficial gut bacterium, C. butyricum improves the skin and mucosa’s microenvironment, enhancing barrier integrity and immune function and protecting against viral invasion. It hampers HSV-2 replication in vitro. Lactic acid, a metabolite of C. butyricum, inhibits the envelope fusion glycoproteins of HSV-2 by altering environmental pH, thus preventing the virus’s entry and spread (49). It also strengthens the body’s ability to combat viral infections by releasing IFNs and pro-inflammatory cytokines (50). Additionally, C. butyricum regulates immune cell proportions by promoting regulatory Treg generation and reducing Th1 and Th17 activation, which inhibits HSV-2 spread and reduces tissue damage caused by infection (27).

3.5 Respiratory syncytial virus

RSV is a seasonal virus that severely affects children under two years of age, leading to viral bronchiolitis. C. butyricum helps combat the virus through various mechanisms. It protects the gut barrier by reducing dysbiosis and improving gut function disrupted by RSV infection, thus indirectly alleviating lung inflammation. It reduced the severity of lung inflammation and decreased tissue damage by modulating the gut-lung axis. Studies showed that the risk of RSV infection is significantly reduced in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant recipients (allo-HCT) with higher levels of butyrate-producing bacteria (51). In animal experiments, butyrate enhanced anti-inflammatory and repair capabilities by reducing inflammatory cell infiltration in the lungs and promoting macrophage polarization toward the M2 phenotype (52). Acetate downregulated pro-inflammatory factors iNOS and IL-1β, and upregulated anti-inflammatory factors Arg-1 and IL-10. Propionate induces type-I interferon-β production and up-regulates antiviral ISGs by GPR43, thereby inhibiting RSV replication and spread. Acetate activated the GPR43 receptor to promote IFN-β production and strengthen host antiviral defenses in lung epithelial cells (53). It also enhanced host recognition of RSV RNA by upregulating RIG-I expression, inhibiting viral replication, and decreasing viral load (54) (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Mechanisms of C. butyricum metabolites against RSV infection. In lung epithelial cells, butyrate inhibits the NF-κB and p38 signaling pathways, downregulating pro-inflammatory factors iNOS and IL-1β, while upregulating the expression of anti-inflammatory factors Arg-1 and IL-10, effectively alleviating inflammation induced by RSV infection. Acetate activates the GPR43 receptor, inducing the production of IFN-β and enhancing the host’s antiviral capability. Additionally, acetate can directly inhibit viral replication by upregulating the expression of RIG-I, and by triggering MAVS aggregation, it induces the production of interferons to exert antiviral effects.NF-κB, Nuclear factor kappa B; p38, p38 signaling pathway; iNOS, Inducible nitric oxide synthase; IL-1β, Interleukin-1β; Arg-1, Arginase-1; IL-10, Interleukin-10; GPR43, G protein-coupled receptor 43; IFN-β, Interferon-β; RIG-I, Retinoic acid-inducible gene I protein; MAVS, Mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein; IRF3, Interferon regulatory factor 3.

3.6 Hepatitis B virus

Approximately 296 million people are infected with HBV, a major cause of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Probiotic therapy has been recognized as an adjunctive therapy to treat liver diseases related to HBV, due to its effects on regulating gut flora and improving liver function. Recent studies show that C. butyricum can enhance liver function and alleviate symptoms in HBV-induced cirrhosis (55).

Sodium butyrate reduced LPS entry into the bloodstream and inhibited the TLR4-mediated increase in intestinal epithelial permeability, which preserved intestinal barrier integrity (56). Simultaneously, C. butyricum alleviated chronic liver inflammation and immune dysregulation caused by HBV infection by regulating inflammatory factors. Additionally, it induced the production of type I interferons, activating the expression of ISGs and the antiviral protein TRIM5 (57). After binding to its receptor, type I interferons activate the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, which in turn activates the IFI6 gene (58). The activated IFI6 can downregulate HBV gene expression and inhibit its replication. HBV infection is known to generate excessive superoxide radicals in host cells, leading to oxidative stress. However, extracellular polysaccharides of C. butyricum possess strong antioxidant properties, protecting DNA from damage (59). It is important to note that interferon-induced MX2 and IFIT3 promote HBV replication in some cases (60) (Figure 4). Current research is insufficient and lacks clinical trials; further investigation into the specific mechanisms of C. butyricum in HBV infection and its clinical efficacy is needed.

Figure 4

Mechanisms of C. butyricum against HBV infection. C. butyricum stimulates IFN-α production upon binding to its receptor and activates the JAK/STAT signaling pathway. This will trigger a cascade of events that induces the expression of ISGs and the synthesis of the antiviral protein TRIM5. Furthermore, C. butyricum can activate the IFI6 gene, which interacts with the EnhII/Cp promoter region (nt1715-1770), inhibiting HBV replication. However, under certain circumstances, interferon-induced MX2 may paradoxically facilitate HBV replication. IFN-α, Interferon-alpha; JAK/STAT pathway, Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription pathway; ISGs, Interferon-stimulated genes; TRIM5, Tripartite motif-containing protein 5; IFI6, Interferon-induced protein 6; EnhII/Cp promoter, Enhancer II/core promoter; MX2, Myxovirus resistance protein 2.

3.7 Other viruses

Previous sections discussed the antiviral activities of C. butyricum against specific viruses. It also exhibits antiviral activities against other viruses. The following discussion presents the antiviral activities of C. butyricum against additional viral infections, focusing on immune regulation and viral replication inhibition.

Sodium butyrate activates the GPR109a receptor and regulates the PERK-eIF2α signaling pathway, inhibiting ERS-mediated apoptosis (61). This mechanism is crucial in RV infection, protecting cells from virus-induced apoptosis and providing potential intervention points for RV prevention and control. C. butyricum modulates interferon-related factors to inhibit BVDV replication (62). It also inhibited PEDV replication through the NF-κB pathway, induced interferon production and downstream ISGs, thereby enhancing antiviral potency (63). Apart from that, C. butyricum inhibited the replication of NDV efficiently in vitro (27). C. butyricum’s antiviral action also involves immune regulation. SCFAs that C. butyricum produces activate the gut-liver axis immune pathway to regulate CD8 T-cell expression and enhance the host’s immune response against FAdV-4 (64). They also caused T lymphocytes and monocytes to adhere to endothelial cells to increase the immunological defenses of the body against EHV-1 (29). During the primary stage of CAHV infection, C. butyricum induced a strong immune response, enhancing Longfin tuna survival rates (29). Clinical studies demonstrated that C. butyricum significantly reduces the risk of lower respiratory tract viral infections in patients undergoing allo-HCT (51). C. butyricum, its key metabolic product SCFAs, and prebiotics exert distinct effects on various viruses in animal experiments. However, clinical trials are still lacking to confirm these findings in humans (Table 1).

Table 1

| Probiotics, prebiotics, and SCFAs | Experimental subjects | Dosage of probiotics, prebiotics, and SCFAs | Virus type | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. butyricum | Mice | 500 mg/kg/day | Influenza virus | Mice supplemented with C. butyricum showed significantly lower mortality and viral load in the lungs compared to the control group. Additionally, IFN-λ expression was upregulated. | (32) |

| Acetate, Propionate, and Butyrate | 1-day-old SPF Chickens | Sodium acetate (80 mM), Sodium propionate (10 mM), and Sodium butyrate (20 mM) | Fowl adenovirus-4 (FAdV-4) | Chickens supplemented with SCFAs showed significantly higher survival rates during acute viral infection compared to the control group. Additionally, the number of activated T cells and MHC II-expressing monocytes increased. | (64) |

| Butyrate | Mice | Sodium butyrate (200 mg/kg) | Bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) | Butyrate treatment significantly reduced BVDV RNA levels in the duodenum, jejunum, spleen, and liver while significantly increasing the expression of ZO-1 mRNA and protein induced by BVDV. | (62) |

| C. butyricum | Gilthead seabream (~5 g average weight) | 1 × 104 cfu/g added to the diet and 1 × 106 cfu/L added to water | Carp herpesvirus (CaHV) | The experimental group with C. butyricum had a significantly reduced viral load and increased survival rate compared to the control group. Moreover, expression levels of innate immunity-related genes (e.g., IL11, IRF7, PKR, and Mx) were also elevated. | (65) |

| Acetate, Propionate, and Butyrate | Pigs | 500 μM acetate, propionate, and butyrate | Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus (PEDV) | The supplementation with SCFAs significantly reduced viral load and upregulated the expression of IFN and ISGs. | (63) |

| C. butyricum | Mice | 1 × 108 CFU/mL, 200 μL/day | Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) | The C. butyricum-supplemented group showed reduced total inflammatory cells and viral load in the lungs of RSV-infected mice compared to the control group. Additionally, levels of macrophages, lymphocytes, and neutrophils were decreased. | (52) |

| High-fiber diet + Acetate, Propionate, or Butyrate (one of them) | Mice | Final concentration 200 mM in drinking water | Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) | The group supplemented with SCFAs had significantly lower viral loads and lung inflammation compared to the control group, with increased IFN-β levels. | (53) |

| Sodium butyrate (SB), Sodium propionate (SPr), and Sodium acetate (SAc) | Horses | 0.5 or 5 mM SB, SPr, and SAc | Equine Herpesvirus 1(EHV1) | The group supplemented with short-chain fatty acids showed reduced innate immune responses in the upper respiratory tract post-EHV1 infection and decreased adhesion of blood-derived monocytes and T lymphocytes to horse endothelial cells. | (29) |

| Butyrate | Mice | 20 mmol/L sodium butyrate | Human papillomavirus (HPV) | HPV16E6/E7 immortalized keratinocytes treated with butyrate had significantly extended survival times and improved cell differentiation compared to the control | (66) |

| Inulin (dietary fiber) | Mice | 30% inulin supplementation | Influenza virus | The group supplemented with inulin showed reduced respiratory inflammation, vascular damage, and subsequent hemorrhage, with activated CD8 T-cells enhancing antiviral immunity compared to the control group. | (32) |

| Sodium butyrate, Sodium propionate, Sodium acetate mixture | Mice | 67.5 mM Sodium butyrate (Sigma 303410), 40 mM Sodium acetate (Sigma S2889), and 25.9 mM Sodium propionate (Sigma P1880) | SARS-CoV-2 | The mixture of butyrate, propionate, and acetate significantly reduced the expression of ACE2 in the gut and lungs and inhibited nasal infections. Additionally, it improved coagulopathy associated with SARS-CoV-2. | (67) |

C. butyricum and its probiotics in antiviral animal models.

4 Alleviating inflammatory diseases: mechanisms of C. butyricum and its metabolites

4.1 Digestive system inflammatory diseases

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) involves inflammatory lesions in the rectum and colon. C. butyricum helps alleviate colitis. Mice treated with C. butyricum showed reduced inflammatory cell infiltration and less damage to the mucus layer in the colon compared to the control group. It also significantly decreased intestinal pathogens like Shigella and Escherichia coli (68). High concentrations of butyrate (80–140 mM) reduced epithelial cell proliferation in colitis mice and enhanced tissue repair (69). Additionally, C. butyricum inhibited TLR2 signaling and IL-17 secretion, improving the local mucosal immune response and providing protection against intestinal inflammation.

C. butyricum shows potential therapeutic benefits of in liver inflammation, particularly in hepatitis and steatohepatitis. Gut-liver immune modulation has emerged as a promising approach in probiotic therapy for liver diseases. In a mouse model of steatohepatitis, the treatment with C. butyricum resulted in a significant reduction in inflammatory responses (70). The levels of inflammatory factors decreased significantly, while the butyrate content in the gut increased markedly. This result was confirmed in clinical trials with NAFLD patients (71). Additionally, C. butyricum alleviates gut microbiota imbalance in NAFLD patients, reduces blood lipid levels, alleviates liver fibrosis, and mitigates liver function damage.

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a common abdominal inflammatory disease. In mouse models, C. butyricumcan prevent AP, possibly by inhibiting neutrophil and dendritic cell infiltration in the pancreas. It also inhibits the TLR4 signaling pathway and the formation of the NLRP3 inflammasome (72). Gut microbiota analysis in mice confirmed C. butyricum’s beneficial effects on gut-pancreas axis homeostasis, showing a significant reduction in Desulfovibrionaceae and increased abundances of Verrucomicrobiaceae, Clostridiaceae, and Lactobacillaceae.

4.2 Respiratory system inflammatory diseases

Upper respiratory tract inflammation, exemplified by eosinophil-dominated chronic sinusitis, is characterized by as type 2 inflammation with an increase in eosinophils, as well as elevated production of type 2 cytokines such as IL-5 and IL-13. Butyrate inhibits the production of type 2 cytokines in nasal polyp-derived cells (73). This may be achieved by inhibiting IL-6 and TNF-α production, leading to macrophage polarization toward the M2 type. In the future, C. butyricum may serve as a potential therapeutic target for ECRS.

For lower respiratory tract inflammation, such as allergic bronchitis, and pneumonia. C. butyricum treatment significantly alleviates allergic airway inflammation and mucus secretion in allergic mice (74). Among the administration routes, aerosol delivery is the most effective, potentially enhancing T cell differentiation and inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome signaling pathways.

4.3 Urogenital system inflammatory diseases

Chronic endometritis is linked to an imbalance in the female reproductive tract microbiota and pathogenic infections. Staphylococcus aureus is a common pathogen, and C. butyricum can inhibit its growth, thereby reducing tissue damage and inflammatory responses (75). Primary nephrotic syndrome (PNS) is a prevalent glomerular disease in children. The C. butyricum treatment group showed significant improvements in body weight and inflammatory responses. Butyrate, a metabolite of C. butyricum, is crucial for Treg cell differentiation. The balance between Th17 and Tregs is key in managing PNS-induced inflammation, suggesting that C. butyricum may mitigate the immune-inflammatory response in PNS by regulating the Th17/Tregs balance (76).

4.4 Musculoskeletal system inflammatory diseases

Rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, and gouty arthritis are common forms of arthritis characterized by bone destruction and joint degeneration. In mouse models, C. butyricum alleviated RA, potentially by producing butyrate to reduce IL-17-producing cells or by inhibiting HDAC2 in osteoclasts and HDAC8 in T cells, thus decreasing bone destruction (77, 78). C. butyricum reduced ACLT-induced bone destruction and loss (79). Additionally, it can inhibit the production of IL-1β, TNF-α, and cartilage-degrading matrix metalloproteinase-3 (MMP-3), blocking cartilage degradation, which may help in OA prevention and treatment. We observed that macrophage polarization levels correlated with the severity of gout (80). C. butyricum regulates macrophage polarization to counteract gouty arthritis by inhibiting miR-146a expression.

4.5 Circulatory and systemic inflammatory diseases

Vasculitis is a group of autoimmune diseases characterized by inflammation and necrosis of blood vessel walls. In a diabetic mouse model, supplementation with C. butyricum increases the level of its metabolite butyrate, activates the Nrf2 signaling pathway, and upregulates the HO-1 pathway, thereby reducing oxidative stress and alleviating HG-induced vascular inflammation (81). In studies of sepsis, C. butyricum stimulates intestinal epithelial cell proliferation and improves intestinal tissue damage. Intravenous administration of butyrate markedly reduces HMGB1 mRNA levels in rat tissues, alleviating the inflammatory response and protecting septic organs.

4.6 Neuroinflammatory diseases

Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) is a chronic central nervous system autoimmune disease. Administration of C. butyricum significantly reduced neuropathological inflammation in the lumbar spinal cord. Compared to the control group, lymphocyte infiltration and myelin damage were both reduced (82). Furthermore, the incidence of physical disability was significantly lower in the C. butyricum treatment group (83). Similarly, in an Alzheimer’s disease (AD) mouse model, treatment with C. butyricum inhibited the phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 in Aβ-induced BV2 microglial cells, thus alleviating microglia-mediated neuroinflammation (Figure 5). C. butyricum produces distinct effects in different models of inflammatory diseases (Table 2).

Figure 5

Mechanisms of C. butyricum in inflammatory diseases. C. butyricum colonizes the intestine and produces short-chain fatty acids that inhibit phosphorylation of the STAT1 signaling pathway, activate the Nrf2/HO-1 antioxidant pathway, downregulating the expression of miR-146a, prohibiting the overactivation of microglia, reducing inflammatory cell infiltration, and promoting M2 polarization of macrophages. These mechanisms provide regulatory effects on inflammatory diseases across six major systems, including the respiratory, circulatory, urogenital, musculoskeletal, neural, and digestive. STAT1, Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 1; Nrf2, Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; HO-1, Heme oxygenase-1; miR-146a, MicroRNA-146a; IFN-α, Interferon-alpha.

Table 2

| Probiotic, prebiotic, and SCFA types | Experimental subjects | Dosage of probiotic, prebiotic, and SCFAs | Type of inflammation | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Butyrate | Mice infected with Lactobacillus in rodents | Butyrate (80–140 mM) | Colitis | Mice supplemented with butyrate showed a significant increase in body weight compared to the control group, a reduction in intestinal epithelial cell proliferation, and an increase in the expression of the Muc2 gene in the gut. | (69) |

| Synbiotic containing C. butyricum and Chitosan Oligosaccharides (COS) | Mice | 10 CFU of Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens and 70 mg/kg COSs daily | Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) | The experimental group showed significantly enhanced colon length, reduced inflammatory markers, and increased expression of tight junction proteins compared to the control group. Additionally, it reduced ROS levels and increased SCFA levels. | (84) |

| C. butyricum | Mice | 200 μL Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens for 6 weeks | Primary Nephrotic Syndrome (PNS) | The treatment group showed improvements in weight loss, a decrease in 24-hour urinary protein levels, and correction of renal dysfunction in PNS mice. | (76) |

| C. butyricum | Mice | Supplemented with 108 CFU/mL of Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens for 20 days | Colitis | Compared to the control group, the experimental group showed a significant reduction in inflammatory responses. IL-6 and IL-1β mRNA expressions were significantly elevated, while MUC2 expression was reduced. The cell composition was also altered, with a decrease in macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), and mast cells. | (85) |

| C. butyricum | Mice | 1 × 107 CFU/200 μL PBS once daily for 7 days | Endometritis | After administration, there was a significant reduction in erythema induced by Staphylococcus aureus, and a marked reduction in MPO activity in the mice. | (75) |

| Clostridium butyric acid live bacterial capsules | NAFLD patients | 400 mg Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens live capsule orally three times daily in addition to oral Rosuvastatin for 6 months | Hepatitis | The combined treatment group showed significant reductions in total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), free fatty acids (FFA), total bilirubin (TBIL), and direct bilirubin (DBIL). | (71) |

| C. butyricum | Mice | 200 μL CB suspension every other day for 60 days | Vasculitis | Compared to the control group, the treatment group showed a significant increase in butyrate levels in blood vessels, a reduction in ROS levels, and an increase in Nrf2 and HO-1 levels. | (81) |

| C. butyricum | Mice | 9.6 × 108 CFU/kg/day | Pancreatitis | Compared to the control group, C. butyricum treatment alleviated AP-related intestinal inflammation and barrier dysfunction, inhibiting pathogen infiltration into the pancreas. The relative abundance of Desulfovibrionaceae decreased, while the abundance of Clostridiaceae, Lachnospiraceae, and Lactobacillaceae increased. | (72) |

| Sodium Butyrate | Mice | 500 mg/kg/day via oral gavage | Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) | Compared to the control group, the intervention group showed significantly higher levels of butyrate in the blood and altered macrophage polarization, with a reduction in M1 phenotype and an increase in M2 macrophages. | (80) |

| C. butyricum | Mice | 0.2 mL daily by oral gavage | Allergic Airway Inflammation | The treatment group showed a significant reduction in airway inflammatory cell abundance and eosinophil recruitment, improving autophagy in lung cells of allergic mice. | (74) |

C. butyricum and its metabolites in inflammatory disease animal models.

5 Discussion

C. butyricum has significant potential in combating viruses and inflammation by regulating intestinal mucosal immunity. It induces interferon production, inhibits viral invasion and replication, and regulates inflammatory factors, demonstrating a powerful anti-infective effect. These mechanisms suggest that C. butyricum influences systemic immune responses through gut microbiota modulation, supporting the gut-immune axis and highlighting the gut’s role in overall health and disease.

We propose the “gut-centric hypothesis,” suggesting that the integrity of the intestinal barrier, gut microbiota balance, and optimal mucosal immune status are key components in the body’s response to viral invasion and inflammation mitigation. This serves as the basis for targeting probiotics in treating viral and inflammatory infections via the gut.

The antiviral impacts of C. butyricum and SCFAs depend on viral type and environmental conditions. For instance, butyrate modulates the immune response to HIV but can also increase HIV-1 and BZLF1 gene expression, activate latent viruses, and accelerate disease progression by inhibiting HDAC activity (86). Additionally, SCFAs inhibit the CXCR2 receptor, preventing CD4+T cell accumulation at infection sites and weakening host immunity (87, 88). High concentrations of SCFAs impair neutrophil responses to HIV by reducing the secretion of antimicrobial peptides, α-defensins, and chemokines, delaying the release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) (48).

SCFAs have a dual role in regulating inflammation. They reduce the production of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and LPS-induced IL-10 in human monocytes without affecting other cytokine and chemokine secretion, exerting an anti-inflammatory effect (89, 90). Conversely, they activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, promoting a pro-inflammatory response in inflammatory contexts. This dual effect may relate to differences in cell types and pathological environments (91).

Not all C. butyricum species are beneficial bacteria. Pathogenic C. butyricum strains include those producing botulinum neurotoxin E (BoNT/E), associated with infant botulism and adult intestinal botulism, and the minority strain MIYAIRI 588, which causes bacteremia in patients, a phenomenon potentially linked to genomic mutations (92–94).Some C. butyricum strains are associated with neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis (CB1002) (95).

6 Conclusions and future perspectives

This review highlights the potential applications of C. butyricum and its metabolites in fighting viruses and reducing inflammation. C. butyricum induces interferon production and significantly inhibits viral invasion and inflammation, showing promise as a clinical probiotic for enhancing intestinal immunity against infections.

There is substantial evidence supporting the use of C. butyricum in treating viral infections and inflammation; however, its mechanisms of action and role in modulating the gut-immune axis need further investigation. Probiotic therapy can restore a healthy mucosal immune status in the gut, facilitating effective responses to viral invasion and inflammation. Future research should focus on large-scale clinical trials to evaluate the efficacy and safety of C. butyricum in various viral infections, particularly gut and respiratory infections. Additionally, further investigation into the regulatory mechanisms of C. butyricum on the host immune system is necessary, especially regarding how different doses and ratios impact the intestinal barrier and immune status. Exploring combinations of C. butyricum with existing antiviral and anti-inflammatory drugs may optimize treatment strategies.

Currently, the application of C. butyricum faces several challenges, such as limited viral specificity and a y narrow antimicrobial spectrum. Clinical dosing is difficult to control, and it should be inactivated when used in combination with antibiotics. Efficacy varies among individuals, storage conditions are demanding, it is prone to inactivation at room temperature, and large-scale clinical trials are lacking. However, these limitations present opportunities for future research. By exploring these areas, we can advance the clinical application of C. butyricum in antiviral therapy and enhance our understanding of its regulatory mechanisms in intestinal immunity, supporting the development of effective and safe probiotic therapies for viral prevention and inflammation modulation.

Statements

Author contributions

SQ: Methodology, Formal Analysis, Data curation, Visualization, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Investigation. SL: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. KY: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. SL: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. XMS: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. DZ: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. ZX: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. XFS: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. RL: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by the Key Specialized Research and Development Breakthrough of Henan Province (242102311071) and the Startup Foundation for Doctor of Xinxiang Medical University (XYBSKYZZ202159).

Acknowledgments

All figures were created with Adobe Illustrator.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Stoeva MK Garcia-So J Justice N Myers J Tyagi S Nemchek M et al . Butyrate-producing human gut symbiont, Clostridium butyricum, and its role in health and disease. Gut Microbes. (2021) 13:1–28. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2021.1907272

2

Zhang D Jian YP Zhang YN Li Y Gu LT Sun HH et al . Short-chain fatty acids in diseases. Cell Commun Signal. (2023) 21:212. doi: 10.1186/s12964-023-01219-9

3

Yang Q Zaongo SD Zhu L Yan J Yang J Ouyang J . The potential of clostridium butyricum to preserve gut health, and to mitigate non-AIDS comorbidities in people living with HIV. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. (2024) 16:1465–82. doi: 10.1007/s12602-024-10227-1

4

Miao RX Zhu XX Wan CM Wang ZL Wen Y Li YY . Effect of Clostridium butyricum supplementation on the development of intestinal flora and the immune system of neonatal mice. Exp Ther Med. (2018) 15:1081–6. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.5461

5

Erawijantari PP Mizutani S Shiroma H Shiba S Nakajima T Sakamoto T et al . Influence of gastrectomy for gastric cancer treatment on faecal microbiome and metabolome profiles. Gut. (2020) 69:1404–15. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319188

6

Takahashi M Taguchi H Yamaguchi H Osaki T Kamiya S . Studies of the effect of Clostridium butyricum on Helicobacter pylori in several test models including gnotobiotic mice. J Med Microbiol. (2000) 49:635–42. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-49-7-635

7

Ma M Zhao Z Liang Q Shen H Zhao Z Chen Z et al . Overexpression of pEGF improved the gut protective function of Clostridium butyricum partly through STAT3 signal pathway. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. (2021) 105:5973–91. doi: 10.1007/s00253-021-11472-y

8

Zhao X Yang J Ju Z Wu J Wang L Lin H et al . Clostridium butyricum Ameliorates Salmonella Enteritis Induced Inflammation by Enhancing and Improving Immunity of the Intestinal Epithelial Barrier at the Intestinal Mucosal Level. Front Microbiol. (2020) 11:3389/fmicb.2020.00299. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00299

9

Chen D Jin D Huang S Wu J Xu M Liu T et al . Clostridium butyricum, a butyrate-producing probiotic, inhibits intestinal tumor development through modulating Wnt signaling and gut microbiota. Cancer Lett. (2020) 469:456–67. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.11.019

10

Kuroiwa T Kobari K Iwanaga M . Inhibition of enteropathogens by Clostridium butyricum MIYAIRI 588. Kansenshogaku Zasshi. (1990) 64:257–63. doi: 10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi1970.64.257

11

Kelly CJ Zheng L Campbell EL Saeedi B Scholz CC Bayless AJ et al . Crosstalk between microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids and intestinal epithelial HIF augments tissue barrier function. Cell Host Microbe. (2015) 17:662–71. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.03.005

12

Long M Yang S Li P Song X Pan J He J et al . Combined Use of C. butyricum Sx-01 and L. salivarius C-1–3 Improves Intestinal Health and Reduces the Amount of Lipids in Serum via Modulation of Gut Microbiota in Mice. Nutrients. (2018) 10:810. doi: 10.3390/nu10070810

13

Lee JS Tato CM Joyce-Shaikh B Gulen MF Cayatte C Chen Y et al . Interleukin-23-independent IL-17 production regulates intestinal epithelial permeability. Immunity. (2015) 43:727–38. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.09.003

14

Burger-van Paassen N Vincent A Puiman PJ van der Sluis M Bouma J Boehm G et al . The regulation of intestinal mucin MUC2 expression by short-chain fatty acids: implications for epithelial protection. Biochem J. (2009) 420:211–9. doi: 10.1042/bj20082222

15

Yang W Yu T Huang X Bilotta AJ Xu L Lu Y et al . Intestinal microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids regulation of immune cell IL-22 production and gut immunity. Nat Commun. (2020) 11:4457. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18262-6

16

Arpaia N Campbell C Fan X Dikiy S van der Veeken J deRoos P et al . Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature. (2013) 504:451–5. doi: 10.1038/nature12726

17

Fontenelle B Gilbert KM . n-Butyrate anergized effector CD4+ T cells independent of regulatory T cell generation or activity. Scand J Immunol. (2012) 76:457–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2012.02740.x

18

Yang W Yu T Liu X Yao S Khanipov K Golovko G et al . Microbial metabolite butyrate modulates granzyme B in tolerogenic IL-10 producing Th1 cells to regulate intestinal inflammation. Gut Microbes. (2024) 16:2363020. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2024.2363020

19

Kim M Kim CH . Regulation of humoral immunity by gut microbial products. Gut Microbes. (2017) 8:392–9. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2017.1299311

20

Cait A Hughes MR Antignano F Cait J Dimitriu PA Maas KR et al . Microbiome-driven allergic lung inflammation is ameliorated by short-chain fatty acids. Mucosal Immunol. (2018) 11:785–95. doi: 10.1038/mi.2017.75

21

Xu J Xu H Li J Zhou Y Nie Y . Sa1862 clostridium butyricum generated anti-inflammatory metabolites to regulate mucosal immunity response to gut microbiota by activating retinol metabolism. Gastroenterology. (2024) 166:S-556. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(24)01747-5

22

Juan Z Zhao-Ling S Ming-Hua Z Chun W Hai-Xia W Meng-Yun L et al . Oral administration of Clostridium butyricum CGMCC0313–1 reduces ovalbumin-induced allergic airway inflammation in mice. Respirology. (2017) 22:898–904. doi: 10.1111/resp.12985

23

Sam QH Ling H Yew WS Tan Z Ravikumar S Chang MW et al . The divergent immunomodulatory effects of short chain fatty acids and medium chain fatty acids. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:6453. doi: 10.3390/ijms22126453

24

Nastasi C Candela M Bonefeld CM Geisler C Hansen M Krejsgaard T et al . The effect of short-chain fatty acids on human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Sci Rep. (2015) 5:16148. doi: 10.1038/srep16148

25

Xiong RG Zhou DD Wu SX Huang SY Saimaiti A Yang ZJ et al . Health benefits and side effects of short-chain fatty acids. Foods. (2022) 11:2863. doi: 10.3390/foods11182863

26

Liu J Chang G Huang J Wang Y Ma N Roy AC et al . Sodium butyrate inhibits the inflammation of lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice by regulating the toll-like receptor 4/nuclear factor κB signaling pathway. J Agric Food Chem. (2019) 67:1674–82. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b06359

27

Chathuranga K Shin Y Uddin MB Paek J Chathuranga WAG Seong Y et al . The novel immunobiotic Clostridium butyricum S-45–5 displays broad-spectrum antiviral activity in vitro and in vivo by inducing immune modulation. Front Immunol. (2023) 14:3389/fimmu.2023.1242183. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1242183

28

Ariyoshi T Hagihara M Takahashi M Mikamo H . Effect of clostridium butyricum on gastrointestinal infections. Biomedicines. (2022) 10:483. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10020483

29

Poelaert KCK Van Cleemput J Laval K Descamps S Favoreel HW Nauwynck HJ . Beyond gut instinct: metabolic short-chain fatty acids moderate the pathogenesis of alphaherpesviruses. Front Microbiol. (2019) 10:3389/fmicb.2019.00723. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00723

30

Majumdar A Siva Venkatesh IP Basu A . Short-chain fatty acids in the microbiota-gut-brain axis: role in neurodegenerative disorders and viral infections. ACS Chem Neurosci. (2023) 14:1045–62. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.2c00803

31

Hutchinson EC . Influenza virus. Trends Microbiol. (2018) 26:809–10. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2018.05.013

32

Trompette A Gollwitzer ES Pattaroni C Lopez-Mejia IC Riva E Pernot J et al . Dietary fiber confers protection against flu by shaping ly6c(-) patrolling monocyte hematopoiesis and CD8(+) T cell metabolism. Immunity. (2018) 48:992–1005.e1008. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.04.022

33

Qiu J Shi C Zhang Y Niu T Chen S Yang G et al . Microbiota-derived acetate is associated with functionally optimal virus-specific CD8(+) T cell responses to influenza virus infection via GPR43-dependent metabolic reprogramming. Gut Microbes. (2024) 16:2401649. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2024.2401649

34

Hagihara M Yamashita M Ariyoshi T Eguchi S Minemura A Miura D et al . Clostridium butyricum-induced ω-3 fatty acid 18-HEPE elicits anti-influenza virus pneumonia effects through interferon-λ upregulation. Cell Rep. (2022) 41:111755. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111755

35

Wackerhage H Kabasakalis A Seiler S Heck H . Is the vLamax for Glycolysis What the V˙O2 max is for Oxidative Phosphorylation? Sports Med. (2025) 55:1853–66. doi: 10.1007/s40279-025-02259-6

36

Mallampalli RK Adair J Elhance A Farkas D Chafin L Long ME et al . Interferon lambda signaling in macrophages is necessary for the antiviral response to influenza. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:3389/fimmu.2021.735576. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.735576

37

Niu J Cui M Yang X Li J Yao Y Guo Q et al . Microbiota-derived acetate enhances host antiviral response via NLRP3. Nat Commun. (2023) 14:642. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-36323-4

38

Antunes KH Singanayagam A Williams L Faiez TS Farias A Jackson MM et al . Airway-delivered short-chain fatty acid acetate boosts antiviral immunity during rhinovirus infection. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2023) 151:447–457.e445. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2022.09.026

39

Lu W Fang Z Liu X Li L Zhang P Zhao J et al . The potential role of probiotics in protection against influenza a virus infection in mice. Foods. (2021) 10:902. doi: 10.3390/foods10040902

40

Chen J Vitetta L . The role of butyrate in attenuating pathobiont-induced hyperinflammation. Immune Netw. (2020) 20:e15. doi: 10.4110/in.2020.20.e15

41

Grinevich VB Kravchuk YA Ped VI Sas EI Salikova SP Gubonina IV et al . Management of patients with digestive diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic: Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Gastroenterological Scientific Society of Russia. Exp Clin Gastroenterology. (2020) 7):4–51. doi: 10.31146/1682-8658-ecg-179-7-4-51

42

Chang PV Hao L Offermanns S Medzhitov R . The microbial metabolite butyrate regulates intestinal macrophage function via histone deacetylase inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2014) 111:2247–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322269111

43

Li J Richards EM Handberg EM Pepine CJ Raizada MK . Butyrate regulates COVID-19-relevant genes in gut epithelial organoids from normotensive rats. Hypertension. (2021) 77:e13–6. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.120.16647

44

Topchiy T Ardatskaya MD Butorova LI Маslovskii LV Мinushkin ОN . Features of the intestine conditions at patients with a new coronavirus infection. Ter Arkh. (2022) 94:920–6. doi: 10.26442/00403660.2022.07.201768

45

Wei J Alfajaro MM Hanna RE DeWeirdt PC Strine MS Lu-Culligan WJ et al . Genome-wide CRISPR screen reveals host genes that regulate SARS-CoV-2 infection. bioRxiv. (2020) 184:76–91. doi: 10.1101/2020.06.16.155101

46

Blanco-Melo D Nilsson-Payant BE Liu WC Uhl S Hoagland D Møller R et al . Imbalanced host response to SARS-coV-2 drives development of COVID-19. Cell. (2020) 181:1036–1045.e1039. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.026

47

Kazemi A Djafarian K Speakman JR Sabour P Soltani S Shab-Bidar S . Effect of probiotic supplementation on CD4 cell count in HIV-infected patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Diet Suppl. (2018) 15:776–88. doi: 10.1080/19390211.2017.1380103

48

Carrillo-Salinas FJ Parthasarathy S Moreno de Lara L Borchers A Ochsenbauer C Panda A et al . Short-chain fatty acids impair neutrophil antiviral function in an age-dependent manner. Cells. (2022) 11:2515. doi: 10.3390/cells11162515

49

Weed DJ Pritchard SM Gonzalez F Aguilar HC Nicola AV . Mildly acidic pH triggers an irreversible conformational change in the fusion domain of herpes simplex virus 1 glycoprotein B and inactivation of viral entry. J Virol. (2017) 91:e02123–02116. doi: 10.1128/jvi.02123-16

50

Feng E Balint E Vahedi F Ashkar AA . Immunoregulatory functions of interferons during genital HSV-2 infection. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:3389/fimmu.2021.724618. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.724618

51

Haak BW Littmann ER Chaubard JL Pickard AJ Fontana E Adhi F et al . Impact of gut colonization with butyrate-producing microbiota on respiratory viral infection following allo-HCT. Blood. (2018) 131:2978–86. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-01-828996

52

Zhu W Wang J Zhao N Zheng R Wang D Liu W et al . Oral administration of Clostridium butyricum rescues streptomycin-exacerbated respiratory syncytial virus-induced lung inflammation in mice. Virulence. (2021) 12:2133–48. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2021.1962137

53

Antunes KH Fachi JL de Paula R da Silva EF Pral LP Dos Santos A et al . Microbiota-derived acetate protects against respiratory syncytial virus infection through a GPR43-type 1 interferon response. Nat Commun. (2019) 10:3273. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11152-6

54

Antunes KH Stein RT FrancesChina C da Silva EF de Freitas DN Silveira J et al . Short-chain fatty acid acetate triggers antiviral response mediated by RIG-I in cells from infants with respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. EBioMedicine. (2022) 77:103891. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.103891

55

Xia X Chen J Xia J Wang B Liu H Yang L et al . Role of probiotics in the treatment of minimal hepatic encephalopathy in patients with HBV-induced liver cirrhosis. J Int Med Res. (2018) 46:3596–604. doi: 10.1177/0300060518776064

56

Fang W Xue H Chen X Chen K Ling W . Supplementation with sodium butyrate modulates the composition of the gut microbiota and ameliorates high-fat diet-induced obesity in mice. J Nutr. (2019) 149:747–54. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxy324

57

Chen S Li S Chen L . Interferon-inducible Protein 6-16 (IFI-6-16, ISG16) promotes Hepatitis C virus replication in vitro. J Med Virol. (2016) 88:109–14. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24302

58

Sajid M Ullah H Yan K He M Feng J Shereen MA et al . The functional and antiviral activity of interferon alpha-inducible IFI6 against hepatitis B virus replication and gene expression. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:3389/fimmu.2021.634937. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.634937

59

Cai G Geng Y Liu Y Yang S Li X Sun H et al . Structure, antioxidant properties, and protective effects on DNA damage of exopolysaccharides from Clostridium butyricum. J Food Sci. (2023) 88:2704–12. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.16609

60

Alfaiate D Lucifora J Abeywickrama-Samarakoon N Michelet M Testoni B Cortay JC et al . HDV RNA replication is associated with HBV repression and interferon-stimulated genes induction in super-infected hepatocytes. Antiviral Res. (2016) 136:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.10.006

61

Zhao Y Hu N Jiang Q Zhu L Zhang M Jiang J et al . Protective effects of sodium butyrate on rotavirus inducing endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated apoptosis via PERK-eIF2α signaling pathway in IPEC-J2 cells. . J Anim Sci Biotechnol. (2021) 12:69. doi: 10.1186/s40104-021-00592-0

62

Zhang Z Huang J Li C Zhao Z Cui Y Yuan X et al . The gut microbiota contributes to the infection of bovine viral diarrhea virus in mice. J Virol. (2024) 98:e0203523. doi: 10.1128/jvi.02035-23

63

He H Fan X Shen H Gou H Zhang C Liu Z et al . Butyrate limits the replication of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in intestine epithelial cells by enhancing GPR43-mediated IFN-III production. Front Microbiol. (2023) 14:3389/fmicb.2023.1091807. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1091807

64

Lee R Yoon BI Hunter CA Kwon HM Sung HW Park J . Short chain fatty acids facilitate protective immunity by macrophages and T cells during acute fowl adenovirus-4 infection. Sci Rep. (2023) 13:17999. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-45340-8

65

Li T Ke F Gui J-F Zhou L Zhang X-J Zhang Q-Y . Protective effect of Clostridium butyricum against Carassius auratus herpesvirus in gibel carp. Aquaculture Int. (2019) 27:905–14. doi: 10.1007/s10499-019-00377-3

66

Li M McGhee EM Shinno L Lee K Lin YL . Exposure to microbial metabolite butyrate prolongs the survival time and changes the growth pattern of human papillomavirus 16 E6/E7-immortalized keratinocytes in vivo. Am J Pathol. (2021) 191:1822–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2021.06.005

67

Brown JA Sanidad KZ Lucotti S Lieber CM Cox RM Ananthanarayanan A et al . Gut microbiota-derived metabolites confer protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Gut Microbes. (2022) 14:2105609. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2022.2105609

68

Zhao J Jiang L He W Han D Yang X Wu L et al . Clostridium butyricum, a future star in sepsis treatment. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. (2024) 14:3389/fcimb.2024.1484371. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2024.1484371

69

Jiminez JA Uwiera TC Abbott DW Uwiera RRE Inglis GD . Butyrate Supplementation at High Concentrations Alters Enteric Bacterial Communities and Reduces Intestinal Inflammation in Mice Infected with Citrobacter rodentium. mSphere. (2017) 2:e00243–00217. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00243-17

70

Zhou D Pan Q Liu XL Yang RX Chen YW Liu C et al . Clostridium butyricum B1 alleviates high-fat diet-induced steatohepatitis in mice via enterohepatic immunoregulation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2017) 32:1640–8. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13742

71

Zhu W Yan M Cao H Zhou J Xu Z . Effects of clostridium butyricum capsules combined with rosuvastatin on intestinal flora, lipid metabolism, liver function and inflammation in NAFLD patients. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). (2022) 68:64–9. doi: 10.14715/cmb/2022.68.2.10

72

Pan LL Niu W Fang X Liang W Li H Chen W et al . Clostridium butyricum strains suppress experimental acute pancreatitis by maintaining intestinal homeostasis. Mol Nutr Food Res. (2019) 63:e1801419. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201801419

73

Toyama M Kouzaki H Shimizu T Hirakawa H Suzuki M . Butyrate inhibits type 2 inflammation in eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2024) 714:149967. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2024.149967

74

Li L Sun Q Xiao H Zhang Q Xu S Lai L et al . Aerosol inhalation of heat-killed clostridium butyricum CGMCC0313–1 alleviates allergic airway inflammation in mice. J Immunol Res. (2022) 2022:8447603. doi: 10.1155/2022/8447603

75

Liu J Tang X Chen L Zhang Y Gao J Wang A . Microbiome dysbiosis in patients with chronic endometritis and Clostridium tyrobutyricum ameliorates chronic endometritis in mice. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:12455. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-63382-4

76

Li T Ma X Wang T Tian W Liu J Shen W et al . Clostridium butyricum inhibits the inflammation in children with primary nephrotic syndrome by regulating Th17/Tregs balance via gut-kidney axis. BMC Microbiol. (2024) 24:97. doi: 10.1186/s12866-024-03242-3

77

Moon J Lee AR Kim H Jhun J Lee SY Choi JW et al . Faecalibacterium prausnitzii alleviates inflammatory arthritis and regulates IL-17 production, short chain fatty acids, and the intestinal microbial flora in experimental mouse model for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. (2023) 25:130. doi: 10.1186/s13075-023-03118-3

78

Kim DS Kwon JE Lee SH Kim EK Ryu JG Jung KA et al . Attenuation of rheumatoid inflammation by sodium butyrate through reciprocal targeting of HDAC2 in osteoclasts and HDAC8 in T cells. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:3389/fimmu.2018.01525. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01525

79

Chen LC Lin YY Tsai YS Chen CC Chang TC Chen HT et al . Live and dead clostridium butyricum GKB7 diminish osteoarthritis pain and progression in preclinical animal model. Environ Toxicol. (2024) 39:4927–35. doi: 10.1002/tox.24367

80

Song S Shi K Fan M Wen X Li J Guo Y et al . Clostridium butyricum and its metabolites regulate macrophage polarization through miR-146a to antagonize gouty arthritis. J Adv Res. (2025) S2090-1232:00354–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2025.05.036

81

Zhou T Qiu S Zhang L Li Y Zhang J Shen D et al . Supplementation of clostridium butyricum alleviates vascular inflammation in diabetic mice. Diabetes Metab J. (2024) 48:390–404. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2023.0109

82

Chen H Ma X Liu Y Ma L Chen Z Lin X et al . Gut microbiota interventions with clostridium butyricum and norfloxacin modulate immune response in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mice. Front Immunol. (2019) 10:3389/fimmu.2019.01662. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01662

83

Sun J Xu J Yang B Chen K Kong Y Fang N et al . Effect of Clostridium butyricum against Microglia-Mediated Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's Disease via Regulating Gut Microbiota and Metabolites Butyrate. Mol Nutr Food Res. (2020) 64:e1900636. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201900636

84

Liu Z Bai P Wang L Zhu L Zhu Z Jiang L . Clostridium tyrobutyricum in combination with chito-oligosaccharides modulate inflammation and gut microbiota for inflammatory bowel disease treatment. J Agric Food Chem. (2024) 72:18497–506. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.4c03486

85

Xiao Z Liu L Jin Y Pei X Sun W Wang M . Clostridium tyrobutyricum Protects against LPS-Induced Colonic Inflammation via IL-22 Signaling in Mice. Nutrients. (2021) 13:215. doi: 10.3390/nu13010215

86

Imai K Yamada K Tamura M Ochiai K Okamoto T . Reactivation of latent HIV-1 by a wide variety of butyric acid-producing bacteria. Cell Mol Life Sci. (2012) 69:2583–92. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-0936-2

87

Vinolo MA Rodrigues HG Nachbar RT Curi R . Regulation of inflammation by short chain fatty acids. Nutrients. (2011) 3:858–76. doi: 10.3390/nu3100858

88

Maslowski KM Vieira AT Ng A Kranich J Sierro F Yu D et al . Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor GPR43. Nature. (2009) 461:1282–6. doi: 10.1038/nature08530

89

Aguilar EC Leonel AJ Teixeira LG Silva AR Silva JF Pelaez JM et al . Butyrate impairs atherogenesis by reducing plaque inflammation and vulnerability and decreasing NFκB activation. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. (2014) 24:606–13. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2014.01.002

90

Cox MA Jackson J Stanton M Rojas-Triana A Bober L Laverty M et al . Short-chain fatty acids act as antiinflammatory mediators by regulating prostaglandin E(2) and cytokines. World J Gastroenterol. (2009) 15:5549–57. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.5549

91

Wang W Dernst A Martin B Lorenzi L Cadefau-Fabregat M Phulphagar K et al . Butyrate and propionate are microbial danger signals that activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in human macrophages upon TLR stimulation. Cell Rep. (2024) 43:114736. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2024.114736

92

Sada RM Matsuo H Motooka D Kutsuna S Hamaguchi S Yamamoto G et al . Clostridium butyricum bacteremia associated with probiotic use, Japan. Emerg Infect Dis. (2024) 30:665–71. doi: 10.3201/eid3004.231633

93

Muldrew KL . Rapidly fatal postlaparoscopic liver infection from the rarely isolated species clostridium butyricum. Case Rep Infect Dis. (2020) 2020:1839456. doi: 10.1155/2020/1839456

94

Scalfaro C Iacobino A Grande L Morabito S Franciosa G . Effects of megaplasmid loss on growth of neurotoxigenic clostridium butyricum strains and botulinum neurotoxin type E expression. Front Microbiol. (2016) 7:3389/fmicb.2016.00217. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00217

95

Ferraris L Balvay A Bellet D Delannoy J Maudet C Larcher T et al . Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis: Clostridium butyricum and Clostridium neonatale fermentation metabolism and enteropathogenicity. Gut Microbes. (2023) 15:2172666. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2023.2172666

Summary

Keywords

antiviral effects, Clostridium butyricum , intestinal barrier, mucosal immunity, relieve inflammation, short-chain fatty acids

Citation

Qian S, Li S, Ye K, Lu S, Sha X, Zhang D, Xu Z, Song X and Li R (2026) The role of Clostridium butyricum and its metabolites in modulating gut mucosal immunity: implications for viral infections and inflammatory diseases. Front. Immunol. 17:1763817. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2026.1763817

Received

09 December 2025

Revised

24 January 2026

Accepted

02 February 2026

Published

18 February 2026

Volume

17 - 2026

Edited by

Panida Sittipo, Burapha University, Thailand

Reviewed by

Maria Touraki, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece

Victor Baba Oti, Griffith University, Australia

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Qian, Li, Ye, Lu, Sha, Zhang, Xu, Song and Li.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shaoju Qian, 211032@xxmu.edu.cn; Ruixue Li, liruixue186@126.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.