- 1Department of Veterinary Pharmacy, Clinical and Comparative Medicine, School of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Resources, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

- 2Graduate School for Cellular and Biomedical Sciences, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland

- 3Veterinary Public Health Institute, Vetsuisse Faculty, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland

- 4Section of Epidemiology, Vetsuisse Faculty, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

- 5Clinical Department for Farm Animals and Food System Science, Centre for Veterinary Systems Transformation and Sustainability University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna, Vienna, Austria

- 6Infectious Diseases Institute, College of Health Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

- 7Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries, Kampala, Uganda

- 8Veterinary Public Health, Ministry of Health, Kampala, Uganda

- 9WVS, Mission Rabies, Cranborne, Dorset, United Kingdom

- 10Department of Community Health & Behavioural Sciences, School of Public Health, College of Health Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

- 11Epidemiology and Public Health, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Allschwil, Switzerland

Introduction: Rabies, a neglected viral zoonotic disease endemic in Uganda, is one of the country’s top seven priority zoonotic diseases. In the period 2021 to 2024, it caused 190 human deaths. Rabies requires an integrated participatory One Health approach for its control. This approach may help reduce the estimated 59,000 annual global human rabies deaths. Over 99% of these deaths are due to bites from infected dogs. Access to the highly effective post exposure prophylaxis (PEP), mass dog vaccinations and rabies surveillance are prioritised in Uganda’s National Rabies Elimination Strategy that is aligned to the global target of eliminating dog-mediated rabies by 2030. Surveillance, required to guide and evaluate rabies control, is currently weak in Uganda, resulting in few cases being recorded. This leads to a “cycle of neglect” of the disease. Medical and animal health professionals require comprehensive surveillance data to inform post-bite responses. An integrated bite case management (IBCM) system presents the opportunity for information about the bite victim and biting animal to be obtained timely to support judicious and economical use of PEP in humans and management of the biting animal. IBCM has not yet been tested in Uganda where PEP is scarce.

Methods: A collaborative change research approach was therefore applied to progressively develop key elements of an IBCM form over three successive multidisciplinary and multi-sectoral stakeholder meetings, which noted that to attain effective joint surveillance, both animal- and human-related information should be obtained from an animal bite incident.

Results and Discussion: Stakeholders identified elements that were grouped under five categories: details of the human bite victim, details of the bite incident, details of biting animal, follow-up of the biting animal and laboratory diagnosis. Four existing rabies surveillance tools in the country were assessed against these categories. The process revealed gaps in the tools currently in use by government ministries hence exposing the silo system in rabies surveillance. This paper highlights the rich content of an IBCM form designed through a stakeholder participatory process, and its advantages over existing tools regarding data collected. It is hoped that its implementation will significantly strengthen joint human and dog rabies surveillance in Uganda.

Background

Rabies is a neglected viral zoonotic disease that causes an estimated annual death of 59,000 (95% C.I. 25-159,000) humans globally, occurring mostly in Africa and Asia (1). Over 99% of these deaths are due to bites from infected dogs. The disease is almost 100% fatal but timely post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) exists and can prevent fatalities (2, 3). Rabies is endemic in Uganda and is one of the country’s top seven priority zoonotic diseases. Half of the districts in the country, spread in all four regions, are considered hotspots for the disease and in the period 2021 to 2024, it is reported to have caused 190 human deaths. In the same period a total of 67,393 human animal bite cases were reported (4). Children are predominantly affected across Africa with children under 20 years accounting for 50% of dog bite cases in Uganda (5) thus being at higher risk of infection compared to adults.

Uganda’s National Rabies Elimination Strategy (NRES) is aligned to the global target of eliminating dog-mediated human rabies by 2030, an initiative of World Health Organisation (WHO), Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) & Global Alliance for Rabies Control (GARC) (6) – shortened as, “Zero by 30”. This ambitious goal is to be realised by large scale interventions such as effective surveillance, dog vaccination, PEP delivery, and education. This target is in line with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) number 3 (healthy lives and well-being for all at all ages) and 15 (sustainability of ecosystems) (7) and Uganda`s Third National Development Plan (NDPIII) (8).

Although prioritised in Uganda’s NRES, the current rabies and dog bite surveillance system is weak for both humans and animals (9). Surveillance is crucial to guide disease control, and if poorly performed, it leads to the well documented “cycle of neglect” of the disease, with low governmental priority dedicated to rabies control (10, 11). Application of a One Health approach – harnessing and combining the efforts of different disciplines and sectors - could enhance surveillance for zoonoses to improve timely case detection and reporting (12). The One Health High Level Expert Panel’s (OHHLEP) definition of One Health emphasises integration of concerted efforts that should aim at achieving sustainable balance and optimising the inter-dependently linked humans, animals, plants, and ecosystems (13). Zinsstag et al. (14) stress the added value of cooperative endeavours through the One Health approach in not only improving health and wellbeing of humans and animals but also fostering financial savings, social resilience and environmental sustainability.

Surveillance for rabies needs to be undertaken simultaneously in the animal and human sector for sustainable control and subsequent elimination. It is therefore a good example of an effort that requires a concerted One Health approach (14–16). Dogs are the main reservoir species of the disease with over 99% of human cases caused by dog bites (2, 3), while wildlife hold a negligible role for the transmission of rabies to humans (17). Therefore, detection and recording of dog rabies cases are thus pertinent to follow rabies outbreaks and to evaluate the effort of control programmes aiming for “Zero by 30”. Dog bites serve as a proxy of human rabies cases (1), and are the event that needs to be surveilled from the human medical side. Both medical and veterinary professionals need appropriate information on the bite victim, circumstances of the bite, and animal-related information, such as tracing and identification of the animal and rabies laboratory test results, to guide their subsequent actions, particularly the use of PEP. With judicious administration of PEP, vaccines can be saved for high-risk cases as was highlighted by Swedberg (18).

In most rabies endemic countries, the surveillance and reporting systems are often lack intersectoral coordination and collaboration, and therefore not fit-for-purpose for surveillance of a zoonosis and provisioning of PEP (19). This also applies to Uganda, where rabies surveillance and reporting systems are independently maintained by the Ministry of Health (MoH) and the Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries (MAAIF). The current records of animal bites contain the species of animal involved but lack any other highly relevant information about the biting animal such as, vaccination status, ownership, owner details and circumstances surrounding the dog bite (e.g. whether or not the animal was provoked).

The Integrated Bite Case Management (IBCM) is a joint rabies surveillance system that combines information on the human bite victim and the biting animal for purposes of risk assessment of the former so as to guide decision on PEP regimen based on the probable infection status of the latter (3). Already 20 years ago, by emphasizing the need to determine the true burden of rabies in Uganda, (20) recommended active animal bite surveillance studies.

Recent findings indicate the variation in implementation processes of IBCM in different epidemiological and geographical settings (19). In Tanzania, Lushasi et al. (21) examined records from health facilities pre- and post-implementation of IBCM, as well as conducted a survey post-implementation to assess knowledge of health workers in clinical signs of rabies. In the Philippines, Rysava et al. (22) had reported a one year-long longitudinal study conducted of animal bite patients for the purposes of investigating the health status of biting dogs and deriving the expenditure on PEP at the time. A study conducted in urban Haiti, with established road network and medical facilities, evaluated the cost-effectiveness of an entire IBCM model (23). A report about a government programme in the Philippines demonstrated success of an intersectoral effort implemented over three years (2007 to 2010) resulting in, among others, improvement in rabies surveillance, and reduced canine cases and human deaths (24). This programme involved a wide range of activities and sectors, including, agriculture, public health, education, environment, legal, and interior and local government. These four studies showed that IBCM is cost effective and can contribute to fostering joint action between the human and animal health sectors, enhancing the quality of surveillance data thus aiding better estimation of the disease burden, better patient care and thrifty use of PEP.

IBCM has not yet been implemented in Uganda and yet it is essential to have such a system so as to reserve the already scarce PEP to high-risk bite victims and ultimately reduce the costs for bite case management in humans (5). Stakeholders in Uganda need to reflect on the prevailing benefits and limitations on the monitoring, surveillance and reporting practices for rabies. For this, the first step is to design and validate an appropriate One Health surveillance form that can further be piloted. Experiences harnessed from the use of such a form, including barriers, constraints, and benefits, are essential to provide evidence-based guidance for potentially scaling up of One Health rabies surveillance. This paper discusses early steps undertaken by key stakeholders in a process aimed at designing an integrated One Health rabies surveillance system in Uganda.

Methods

Study design

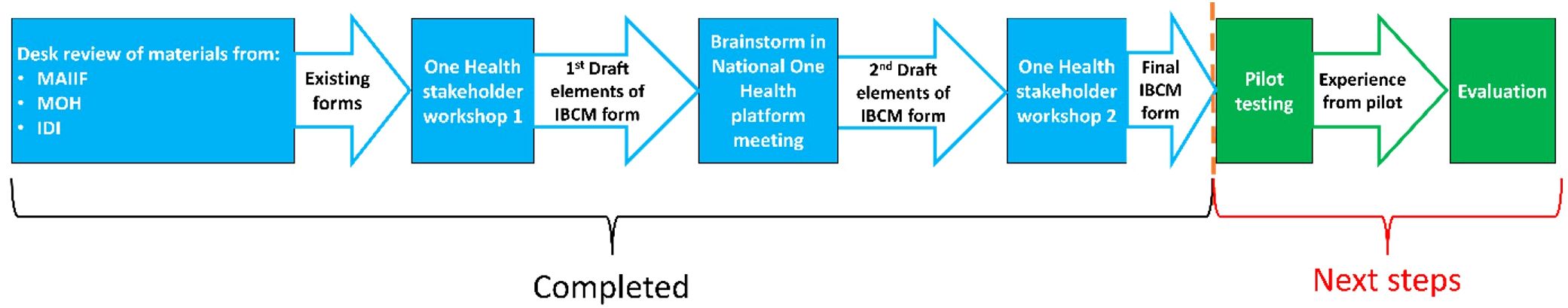

A collaborative change research approach (25, 26) was applied. Initially, informal interviews were conducted with officials from MoH and MAAIF responsible for disease surveillance about existing rabies data collection and reporting tools, followed by a desk review of existing surveillance tools. Thereafter, a participatory data collection process was applied through a series of three facilitated interactive stakeholder meetings in March, June, and August 2023. The IBCM-related outputs of each meeting were collected and used to cumulatively improve the quality of the information generated in the previous sessions (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The chronology of the processs of the change research approach for generating the key elements of a Ugandan IBCM form. MAAIF, Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries; MOH, Ministry of Health; IDI, Infectious Diseases Institute; IBCM, Integrated Bite Case Management.

Interviews with MoH and MAAIF officers and desk review

Two informal, unrecorded interviews were conducted with one official each responsible for data in MoH and MAAIF. The main aim of the discussion was to understand the stage of the integration of the rabies surveillance systems between the two ministries. These were the only ministries conducting rabies surveillance and maintaining databases of animal bites and rabies cases at the time.

Thereafter, a desk review of the available rabies surveillance frameworks for data capture and reporting was performed. The forms used by the MoH (the Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR)) and MAAIF {the Event Mobile Application (EMA-i), developed by the FAO}, and the proposed reporting form by Makerere University`s Infectious Diseases Institute (IDI) were reviewed. While the former two applied their data capture tools countrywide, the latter had piloted its version only in Arua District in northern Uganda. Each of the entry items in the data capture and reporting tools were examined to assess the type of information captured about both the biting animal and the respective human bite case. The analysis of these tools guided the development of the initial form used in the stakeholder meetings.

Stakeholder meetings

Participants of all the three stakeholder meetings were purposively selected based on their work experience with rabies and/or involvement in One Health activities. Official letters of invitation, detailing the purpose of the meetings, were sent by e-mail.

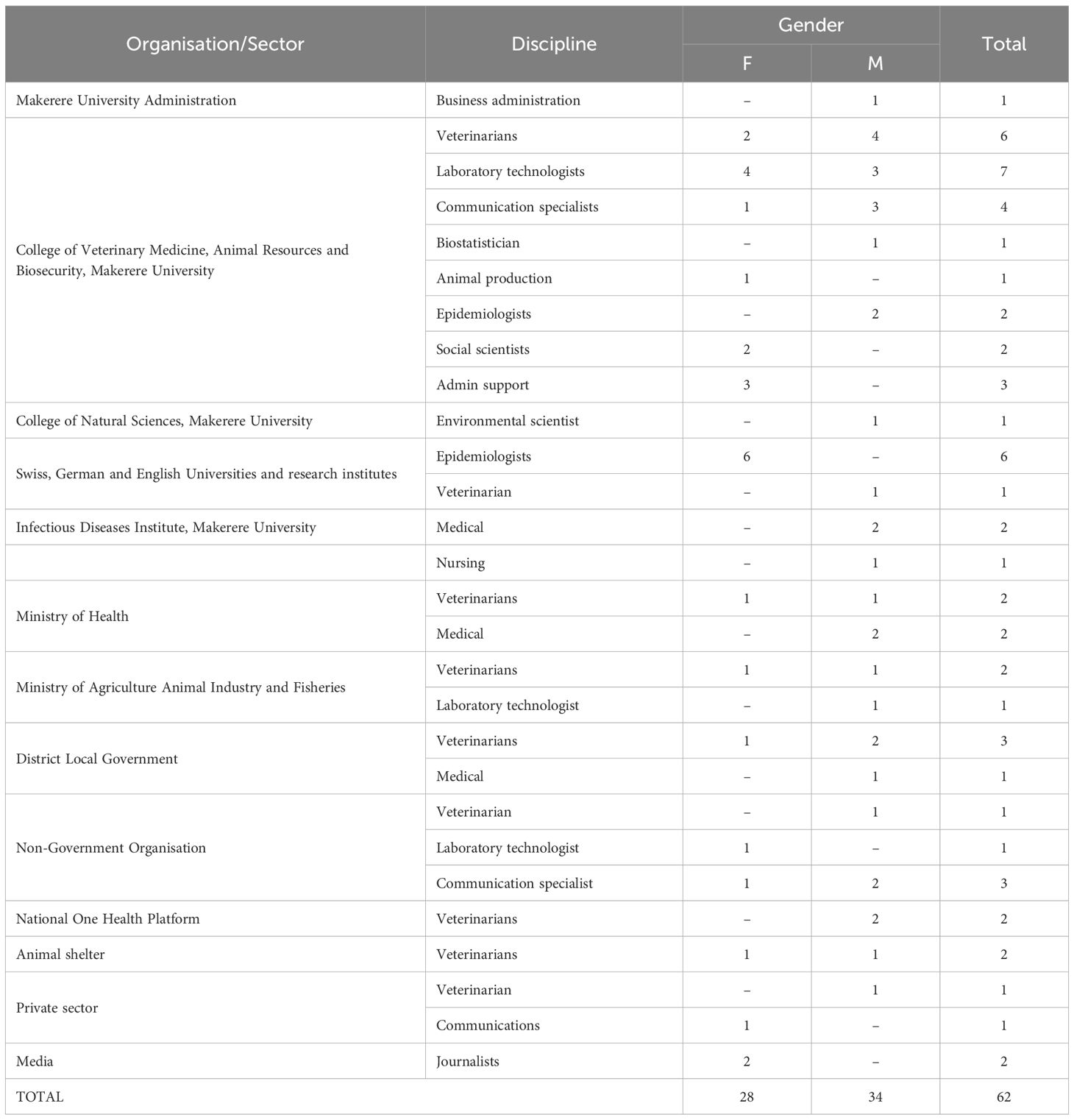

Meeting 1

The first stakeholders’ meeting (Meeting 1) was held on 6th and 7th March, 2023 in Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda. The meeting was jointly planned by the research team and rabies focal persons from MoH and MAAIF. The meeting was conducted in a hybrid manner, with the majority attending in person while a few international research team members joined from abroad online. The latter made presentations in the first session of the workshop about rabies diagnosis, characterising the rabies virus and shared experiences from other countries. The meeting had a multidisciplinary representation of 62 participants, including veterinary professionals, medical professionals, sociologists, laboratory technologists, epidemiologists and environment scientists as participants (Table 1). The participants were selected from academia, central government, local government, non-governmental organizations and the private sector.

Table 1. Categories of stakeholders participating in the first meeting to generate an integrated rabies surveillance form in Uganda in March 2023.

The first session involved introductory presentations on rabies, the e-Rabies Project funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (IZSTZ0_208430), and IDI, MoH and MAAIF efforts, thus far, in rabies surveillance. The subsequent sessions involved working in small groups, each comprised of not more than five members of mixed disciplines and sectors, to generate outputs that were presented and discussed in a facilitated plenary to arrive at a consensus on positions. Each of the groups discussed the following: reflections on the practices and experiences in their respective jurisdictions, reasons for the need of IBCM, strategies for implementation of IBCM and their associated anticipated challenges. Information obtained from group work and plenary discussions were synthesised into key themes. One of the key outputs of the synthesis was a set of elements for a proposed IBCM form, which was used as Draft 1 in the subsequent meeting.

The plenary also brainstormed on key success factors for rabies elimination in Uganda. To come up with key success factors for elimination of rabies in Uganda, the participants made individual submissions through an online tool, “Padlet” (https://padlet.com/). These submissions were then synthesised into themes and milestones extracted from each of them.

Meeting 2

The second stakeholders’ meeting (Meeting 2) was held from 5th to 10th June, 2023 in Ridar Hotel in Mukono District, Uganda. It was convened by the Ugandan National One Health Platform (NOHP) with the overall purpose of discussing the principles and justification for a national One Health policy. This is a necessary initial step in the stakeholder engagement processes of policy development in Uganda. Joint surveillance of zoonotic diseases across government ministries (MoH, MAAIF, Ministry of Water and Environment) and agencies, such as Uganda Wildlife Authority formed the specific topic of the meeting. The NOHP is a non-statutory multi-sectoral governmental body established to promote and coordinate One Health activities in Uganda. The meeting was facilitated by policy development experts from the government, supported by legal officers from the Solicitor General`s office. The categories of participants were similar to those in Meeting 1, with lawyers and policy design specialists included additionally; however, it was less international with all participants being Ugandan residents. In total, 59 people participated, with only a few of them having attended Meeting 1. Draft 1 of the IBCM form was presented in one of the sessions, and a discussion in the plenary was conducted to collect suggestions for improving its content. The modifications were incorporated in real time in a document projected on a large screen. The output of this process formed Draft 2 of the IBCM form.

Meeting 3

The third stakeholders’ meeting (Meeting 3) which was held on 29th and 30th August 2023 was again convened at Makerere University. Representation of invited participants and the processes were comparable to Meeting 1. Introductory presentations were made, covering output of the previous meetings and experiences from the field on rabies surveillance and dog bites by the local government departments of human and animal health. Group work was conducted in sizes of not more than five members of mixed sectors with the following tasks: Refine Draft 2 and review possible challenges of rabies joint surveillance and their mitigation measures. The outputs of each group were presented and compiled during a plenary discussion to produce the final version of the elements of the IBCM form (final draft).

Comparison of surveillance tools

The elements of the final draft of the IBCM form were subjected to a comparative analysis with the existing rabies surveillance tools identified in Uganda: the EMA-i, developed by the FAO and used by MAAIF, the IDSR system used by the MoH, and the paper-based form implemented by the IDI specifically for rabies surveillance. Additionally, the comparison was assessed against an internationally applied tool, the Rabies Exposure Assessment and Contact Tracing (REACT) App developed by Mission Rabies in collaboration with the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (International Rabies Taskforce, n.d.). The REACT App was developed as an IBCM tool that offers real-time data collection and tracking and is shown to provide comprehensive information on reporting, assessment, quarantine and follow up for both human and animal rabies exposure and cases. The comparison involved assessing whether the data elements outlined in the final draft were present or absent in each tool. Similarities and differences were recorded. This comparative assessment was a collaborative effort involving stakeholders from MAAIF, MoH, IDI, Mission Rabies, and other professionals who work regularly with these tools.

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee) of the School of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Resources, Makerere University (SVAR-IACUC/135/2023) and subsequently by the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (Research registration number HS3463ES).

Results

The key outputs of the above processes that will be discussed in this paper are, i) the common position amongst stakeholders on the need for joint surveillance, ii) the elements of the drafted IBCM form (Final Draft), iii) the tabulated output of the comparative analysis of the existing surveillance forms against the drafted IBCM form, and iv) a short summary of key success factors for rabies elimination perceived by the stakeholders.

Current practice and requirements of an IBCM form

It became clear from the informal interviews that each of the two ministries (MoH and MAAIF) collects its own data independent of the other and that there was no linkage between the two sets of information obtained about human bite cases and details of the animal involved in the bite.

Discussion from the meetings revealed stakeholders’ appreciation of the need for and significance of joint surveillance, and that unfortunately, the platforms used by the ministries responsible for human and animal health, do not capture all relevant information about rabies cases. The MoH uses the IDSR platform, which documents animal bites and patient information but neither animal-related information nor circumstances surrounding the dog bite. The information is transmitted from the District Health Officers to the MoH through the use of a phone SMS service. On the animal side, the MAAIF receives monthly reports from the District Veterinary Officers (DVOs), suspected disease event notifications from EMA-i mobile application and laboratory records of the National Animal Diseases Diagnosis and Epidemiology Centre (NADDEC). Previously these reports were sent by e-mail and postal services or through hand delivery of hard copies. They are now submitted electronically through e-mails as macro-enabled Excel sheets or an online web or mobile-based platform, EMA-i. The two online platforms (IDSR and EMA-i) are not linked and neither can they be accessed by staff outside the respective ministries. However, following the first workshop, it was reported that the veterinary office in at least one of the districts represented in the meeting started referring all bite cases to the district medical unit with all details of the available information on the biting animal and the incident of the bite. The meeting participants reported that bite victims, who eventually reach one of the rare public or private health units with available PEP, typically will receive their first dose. It was however not clear to them what proportion of victims complete the full course of PEP dosages recommended by WHO.

Elements of the drafted IBCM form

The key elements of the final draft of the IBCM form included both human and animal information. Three broad categories of these elements were identified in the first draft and maintained throughout the process of review. These include bite case information, medical information on the bite victim, and animal and veterinary information (Supplementary Table 1). The first category of data elements could be entered by either the medical or veterinary professional, depending on which professional the bite victim reports to first. The other two categories are specific to the respective professions. The bulk of the improvements (from first to final draft) of the form were mainly involving animal and veterinary information, and most were reflected in the second draft. Improvements made in this section mainly involved specifying animal species, its vaccination status, ownership status, confinement, and results of laboratory diagnosis. The human-related improvements made to the second draft involved mainly area of abode of bite victim, cause of wound (bite, scratches, or else), record of previous bite incidences, vaccination status, challenges faced in reporting (by victim or their helper), and fate of the victim. The three categories of elements in Table 1 were later regrouped into five for purposes of ease of presentation: details of the human bite victim, details of the bite incident, details of biting animal, follow-up of the biting animal and laboratory (diagnostic test and results).

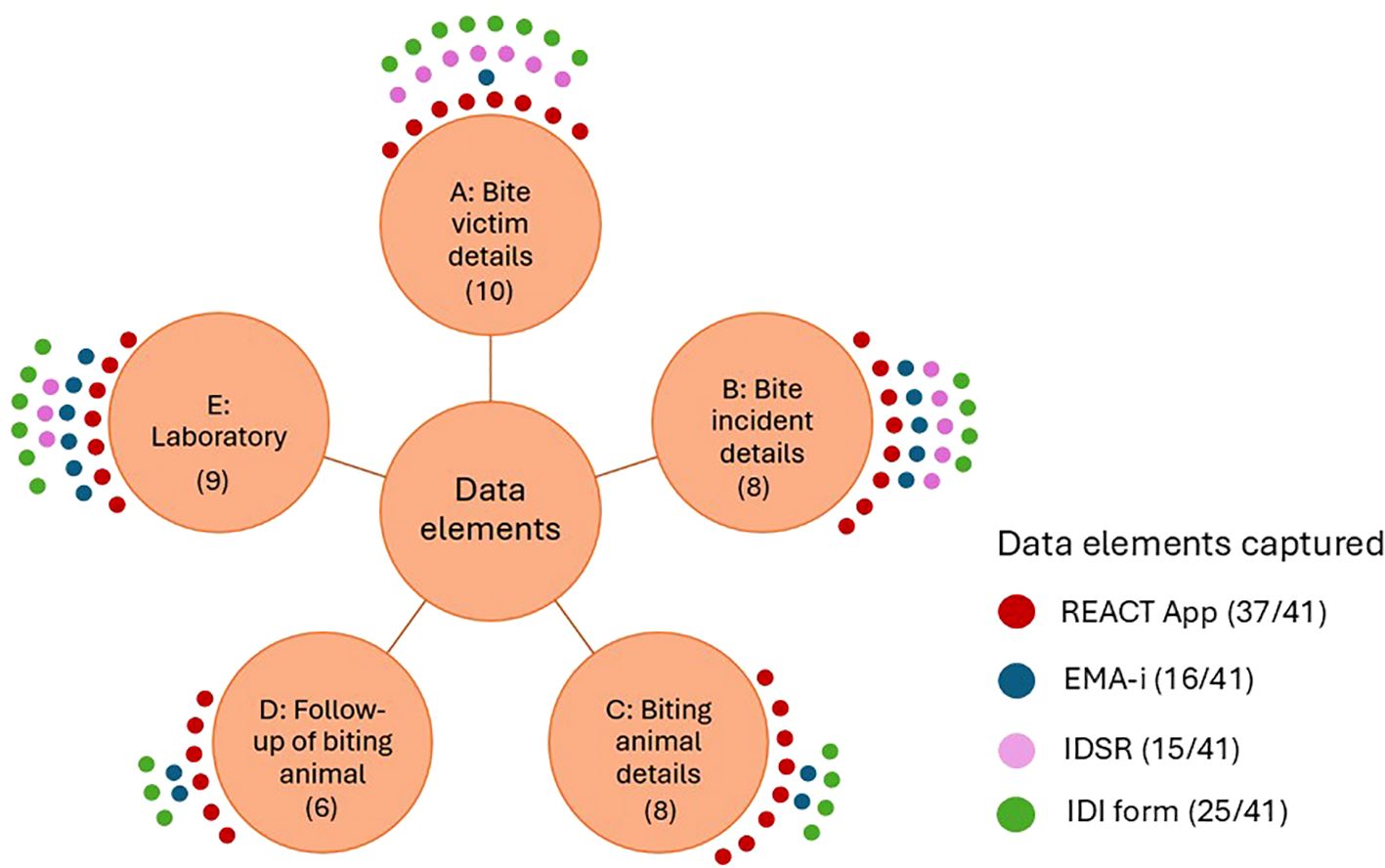

Comparison of the existing surveillance tools

Details of the comparative analysis of the existing surveillance tools against the final draft of the developed IBCM form is provided in Supplementary Table 2. The analysis revealed that the REACT App, being a tool that has been specifically designed for rabies surveillance, captures nearly all critical elements required for IBCM as outlined in the Final Draft, covering 37 out of 41 data points (Figure 2). It is the only surveillance tool that fully captures information about the biting animal, including test performed and laboratory findings, and helps to ensure feedback of results to all the stakeholders involved in the IBCM process.

Figure 2. Comparison of tools for integrated rabies surveillance. The maximum number of data elements for each of the categories was; (A) 10 elements; (B) 8 elements (C) 8 elements (D) 6 elements and (E) 9 elements, making total of 41 elements. Counts of the elements captured by each of the tools indicated in the figure by dots) were recorded and summed up to obtain a final score.

The IDI paper-based form also captures a majority of IBCM data elements, recording 25 out of 41 identified data points, including all key human-related information. Although it lacks some detailed documentation about the biting animal and its follow up, it is the only form that has the element on provocation of the dog.

In contrast, EMA-i is a smartphone-based application developed for real-time animal disease outbreak monitoring. While it includes some information related to animal bites and laboratory results (captures 16 out of 41 data points), it lacks specific rabies-related elements and does not capture detailed human-related data or detailed incident information. Currently, EMA-i is only accessed by MAAIF and government veterinary and wildlife officers, and excludes private veterinary practitioners.

The IDSR tool focuses mainly on human bite victims, using bite reports as a proxy for suspected rabies cases. With only 15 out 41 data elements captured, it scored lowest among the tools assessed. The systems include most human related data but lacks information on the biting animal, its follow up, and laboratory diagnostics. In the laboratory category, the only data point (out of a possible nine) it provides for is the test results.

None of the four forms considered the elements tribe and nationality of the bite victim that are included in the Final Draft.

Key success factors and milestones for rabies elimination

The meeting output related to the stakeholders’ views on key factors for the elimination of rabies in Uganda was synthesised under four main themes: application of appropriate methodological approaches, strengthening institutional (research and leadership) capacity, sustained access to vaccination, and effective community engagement. The key broad milestones extracted from the synthesised themes were:

a. Sustained cooperation between sectors at all levels of implementation of rabies control activities through One Health approaches.

b. Appropriate leadership and partner support to strengthen better knowledge of rabies epidemiology and enhanced surveillance.

c. Sustained access to PEP for humans and rabies vaccines and vaccination campaigns for dogs.

d. Enhanced community awareness, engagement and responsible dog ownership.

Discussion

The stakeholder participatory process produced elements of an IBCM form that captures both human and animal information relevant for joint rabies surveillance. It also highlighted the appreciation and need for cross-sectoral collaborative effort in rabies surveillance. Rabies is a classical disease that requires One Health approach for effective control and subsequent elimination, especially in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (16).

Study strengths and limitations

The multidisciplinary nature of participants and the sectors from which they were drawn fits within the classification of key One Health stakeholders (13, 14). They represented the key actors in rabies surveillance in Uganda. The multidisciplinary stakeholder approach also provided an avenue for free exchange and harnessing of ideas from different disciplines and sectors. It fosters the operationalisation and highlights the benefits of the One Health approach. Different approaches were used for designing IBCM forms in other countries (21, 23, 27). The key difference between this study’s methods and those used in the other countries is that we involved the key stakeholders in the conceptualisation and subsequent development of the form, typical of a participatory approach (28). These same stakeholders will participate in implementing the IBCM form, while improvements to the form and the implementation process is continued. Through this, they will harness benefits of the participatory approach such as, participating in and learning from the actions of the pilot phase of the study (29). Further benefits of the transdisciplinary approach used in our study include providing an environment of mutual respect between researchers and research participants, minimising power imbalances among and between the actors, and giving the participants opportunity to take part in actions that provide solutions to their own problems (28). The knowledge acquired from the collaborative engagement can be put to real-world action, which has been observed in our study. In one of the districts, the veterinary office initiated the process of referring bite victims to health units along with a form that contains information about the animal involved in the bite, bite incident information and where it happened. This change was adopted after meeting 1 and was reported in meeting 3. This is one of the fruits of participatory research approaches in which the research subjects themselves are involved thus fostering shared leadership to pursue the goal of positive social change (26). Another example using a similar approach was reported by Nana et al. (30); they registered success in the process of developing a One Health surveillance system for anthrax, a zoonotic disease, in Burkina Faso.

Some limitations in our methods should be acknowledged. While all the relevant disciplines were represented, there were disproportionate numbers for the various disciplines, veterinarians being the majority. However, the participatory nature of the discussions minimised the dominance of majority effect, because active participation was encouraged, and all opinions captured and considered on their own strength and not necessarily by majority. In addition, the meetings were held in the university or in a hotel, deliberately out of any of the government ministries to mute the undesirable effect of host dominance in One Health activities, hence creating an environment of free participation of all the stakeholders. Establishing power equilibrium is emphasised in participatory research (28). Another limitation is that top-level decision-makers did not participate in the meetings, although the national implementation of the IBCM needed their commitment. Their respective mid-level managers and implementers of the form participated in the meetings and as the practice is, they will advise their top-level leaders after the form has been piloted to seek approval for scaling out.

Current practice

The IDSR and EMA-i are currently not linked in Uganda, so information collected by either side is not available to the other. This is on one hand due to the respective ministries’ current policies on data sharing which do not recognise the One Health approach and its benefits in zoonotic disease surveillance. There is, however, an ongoing pilot collaborative project being conducted in some African, South American and Asian countries by University of Oslo and FAO to connect human health, and animal health and zoonoses surveillance within DHIS-2 (31). Uganda is not one of the pilot countries. Additionally, adoption of practices that reflect a One Health approach is still work in progress. Although the quadripartite recommends an effective coordination mechanism and a backbone of policy and legislation for the successful implementation of One Health national plans (32), the Ugandan NOHP is a non-statutory entity that lacks policy backing and the necessary resource support to execute full functions. The NOHP was borne out of an MoU for operationalising the One Health Framework of 2016 developed by the MAAIF, MoH, Ministry of Water and Environment and Uganda Wildlife Authority. Its key responsibility was oversight and coordination of the implementation of the Uganda One Health Strategic Plan 2018-2022, an inter-sectoral and multi-agency collaborative strategy. The plan addressed itself to the seven priority zoonotic diseases in Uganda, rabies being one of them. Strengthening surveillance of these priority diseases in humans, domestic animals and wildlife was one of the key actions (33). Despite the presence of the NOHP and respective plan, its operationalisation and implementation remain challenging. The current practice, i.e. the non-functioning One Health surveillance, leads for example to the failure to track the number of PEP doses taken by a bite victim hence the risk of death by victims bitten by rabid animals and perpetuation of false information on demand of PEP.

Content of the IBCM form

Having been developed by the ultimate users of the form and the information gathered by them, the form is therefore context-specific and thus most appropriate for use in rabies surveillance in Uganda. The rich output of elements identified here would be expected of a form created by the key actors in rabies surveillance in an inter- and transdisciplinary, participatory process. Its apt implementation will present, besides the expected improvement of rabies surveillance, a good opportunity for learning that will inform joint surveillance strategies for other zoonotic diseases.

The content of the IBCM form developed is comparable to those used by previous workers in other jurisdictions and contexts. We note several similarities and a few differences in detail between it and that which was applied in Tanzania by Lushasi et al. (21). In the latter case, unlike in the IBCM form developed, there was no direct provision for capturing information about the involvement of traditional healers, the administration of rabies immunoglobulin, challenges faced in reporting the incident and in specifying categories of domestic dogs (such as roaming but owned, roaming and not owned or stray). Some other elements were not captured by our form but included in the IBCM in Tanzania: bite victim behaviour at the time of reporting the case and record of tentative assessment decision (normal, rabies suspect, or other illness). These differences may not be lost in both situations because both forms have provision for “any other information” or “comments” in which such information that we believe would obviously arise from direct observation and further probing can be recorded.

The IBCM form developed, though, whether used in hard copy or electronic version, allows the entries to be initiated from either the human or animal health side. Besides bite victim information, there are other elements in the form that would make it possible for an entry initiated by the medical side to be identified and matched to entries made from the veterinary side, and vice versa. In this case therefore, the electronic version of the IBCM form will be accessible from both sides to enter cases and access the database albeit with administrative controls. This will overcome the hitherto silo mentality of information management therefore making joint data analysis, interpretation and reporting possible and easier. Confirmation of rabies is only possible through laboratory diagnosis. It is notable that the form has provision for capturing laboratory test results only for animals, although WHO recommends that clinical cases in humans should also be confirmed through laboratory-based techniques (World Health Organisation, n.d.). This gap suggests that it is not routinely done in Uganda thus contributing to under-reporting of dog-mediated rabies fatalities in humans. It also presents an area of interest in research and medical practice guidelines for rabies surveillance. It is important therefore to discern and stipulate the hitherto unknown cultural difficulties associated with testing human samples and to explore the scope of rabies case definition in medical practice in Uganda.

In principle, the form enables reporting of bites from all species of animals involved, including wildlife. A recent cross-sectional survey reported more human rabies cases and mortality in communities living closer to wildlife conservation areas compared to those living further away, although no direct claim of wildlife involvement in rabies transmission to humans was made (34). Another recent unpublished report about jackals biting humans in Busia in eastern Uganda also shows the non-negligible relevance of wildlife rabies during outbreaks. Therefore, recording of wildlife bite cases and wildlife infected by rabies found dead opportunistically into the IBCM forms would possibly improve rabies surveillance in wildlife in Uganda.

Comparison of tools used in Uganda

Comparison of data elements in the existing surveillance tools with those in the developed IBCM form revealed the latter’s comprehensive coverage of the elements of interest in rabies surveillance. The comparison brought to light the hitherto siloed nature of the rabies surveillance and reporting system currently used in Uganda (EMA-i and IDSR), also earlier reported by Hartnack (9). They are, unfortunately, incongruent and hence do not complement each other. The REACT app, IDSR, EMA-i and the IDI forms had additional specific areas of peculiarities relevant to the implementation of IBCM. Since IDSR and EMA-i were not designed with IBCM in mind, they each focused on only human- and animal-related information respectively unlike the others two that had both. The REACT App scored 100% on animal-related information which is attributable to the fact that it was developed specifically for rabies surveillance. Similarly, since the IDI form was also designed specifically for rabies surveillance, it had provision for recording whether the biting animal was provoked or not. This is a very important consideration in guiding the decision to or not to follow up the animal and yet was not explicitly stated in the other three tools (REACT, EMA-i, and IDSR). This decision will have an impact on investment in operations and PEP utilisation. Results of an earlier study in Chad (35) illustrated that a small proportion of bites are caused by rabid animals, which indicate the importance for follow up of biting animals with the aim of supporting frugal use of PEP.

None of the four compared surveillance tools captured tribe and nationality of the bite victim, two elements that were identified throughout the process of our study. These elements could possibly be pointers to some cultural and socio-economic practices that are relevant to dog management and bite prevention. The role of cultural and economic activities in dog movement and rabies transmission has been hinted on in south-east Asian and Oceanic regions (36). Perceptions that linked signs of rabies in humans to witchcraft have also been reported in South Africa (37).

The element of laboratory diagnosis in dogs is covered in all four tools, which was not surprizing because of its importance due to WHO requirement for confirmatory diagnosis (38). The IDSR captured information on test results, but not the other elements (such as, sample collected, date of collection, sample dispatch details, name of laboratory and reporting). In the EMA-I, there was no provision for specifying the laboratory from which tests are done. This may be due to an assumption that samples would end up in better equipped regional and central laboratories. This dependency on a few laboratories is a clear sign of inadequate rabies diagnostic capacities in the countryside, and would gain in evidence in case the identity of the testing laboratory would be captured. Currently, rabies diagnosis using FAT could only be done in two laboratories in the country - one at Makerere University and the other at the National Animal Diseases Diagnostics and Epidemiology Centre. Meanwhile, although it is only the REACT App that gives provision to record the test carried out, is important to consider it in the IBCM practice to verify if the gold standard was used in preference to many other recommended tests by the WHO (38).

Final case reporting to all stakeholders in the bite case was only considered in the REACT App despite its significance in building confidence in the disease surveillance system and enhancement of participation.

It is only the EMA-i form that had an indirect proxy for animal welfare. It captured information on “number of animals destroyed”. Although it was most likely not intended for animal welfare concerns, it is important to note that some communities in Uganda do kill animals suspected to be rabid, often using brutal means. Killing of large numbers is ethically questionable. Additionally, this form was designed for animal disease outbreak monitoring which may involve “destruction of animals”, a practice approved by WOAH, as a disease control measure in livestock, among others (39).

In summary, the comparative assessment between the existing tools shows that REACT is a comprehensive tool aligned with IBCM requirements identified in Uganda. In contrast, tools like IDI, EMA-i and IDSR each captures only a subset of necessary data. REACT facilitates a systematic and coordinated response to animal bites while offering real-time data collection and longitudinal case management in a smartphone-based application (40). The IDI form though captures many required data elements, its paper-based nature, limits its utility, underscoring the increasing need for digital solutions and real-time data access in rabies surveillance, especially in a rabies endemic country like Uganda.

Key success factors and milestones for rabies elimination

The key success factors that were identified in the study largely mirror the strategic actions in the “Zero by 30” plan and the NRES. Vital among them is the element of leadership, which is important in any strategic action, particularly involving multidisciplinary and multisectoral networks of people. Its significance in One Health is stressed by Stephen & Stemshorn (41) with reference to attributes of horizontal leadership: flexibility, absolute transparency, excellence at strategic analysis, managing relations, troubleshooting to find solutions and organizing work in complex models.

Adoption of IBCM will present a great opportunity for the country to advance its efforts towards rabies elimination and realise benefits stated by WHO thus, “Investing in rabies strengthens health systems, improves equity and access to healthcare and contributes to sustainable development” (6).

Future actions

The diversity of design and implementation approaches of IBCM as reported by Swedberg et al. (19) is instructive for every country to tailor it to their context. It is therefore pertinent to pilot and refine the form generated here to attain contextual fit. Currently, the pre-pilot of the IBCM is ongoing. Information is initially captured on paper by the veterinary or medical official the bite victim reports to first and later transferred to the digital application REACT by a different official who is trained in the use of the application. The REACT app was selected for this purpose to enable a pilot testing before the potential digitalisation and subsequent implementation of the developed IBCM form. The reason to have chosen the REACT app was based on its almost completeness of the 41 data elements identified in the final form, of which the REACT had 37. Additionally, other countries, such as Haiti and Vietnam, already used the REACT App for rabies surveillance with success (42, 43). Working with data collected over a 6.5-year period, they concluded that the use of an electronic application was superior to the paper-based method. The former presented a better reporting efficiency and the data was more comprehensive and complete.

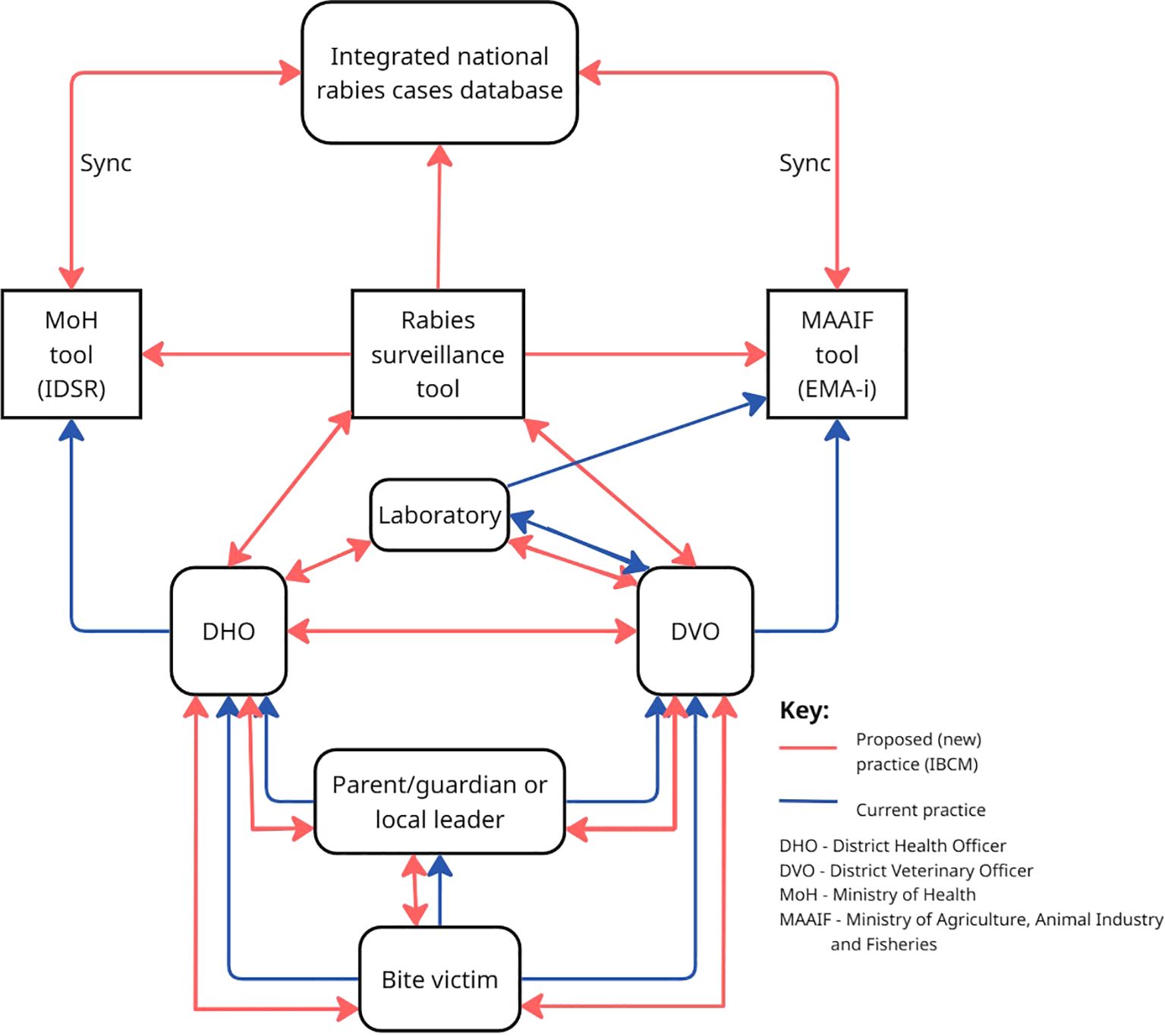

Alternatively, linking data captured by the IDSR and EMA-i tools would be a way to integrate rabies surveillance in a One Health approach. However, respective discussions with MoH and MAAIF were not conclusive. It required further technical and administrative consultations and higher-level agreements, which were beyond the scope of the stakeholder meetings. Nevertheless, ideas should further be explored in the near future to integrate the IBCM tool into the current surveillance systems in Uganda, since the technical ability for its development is available (Figure 3). It is noteworthy that no computer scientist participated to the meetings within our study, which calls for better integration of the technical experts during such One Health discussions. Collaborative investments by the two sectors were earlier recommended with the hope that surveillance would be improved and the true burden of the disease established to inform and guide national control actions (1). As is usually the case, the bite victim either directly (if an adult) or through a parent, guardian or local leader (if a child or adult who needs help) reports to the nearest veterinary office or medical unit as the first point of contact for capturing surveillance data. The DHO or DVO captures the initial data that was submitted by the medical or veterinary unit, respectively, as indicated in the form and also alerts their counterpart about the case. Involving both the public and private medical and veterinary facilities in this process is vital as non-reporting from the private practices would lead to incomplete data collection as was noted previously (20). In Figure 3, while the visualisation of the current system (blue arrows) reveals the lack of information flow between the medical and veterinary sectors, the proposed new system (red arrows) demonstrates direct information flow at various levels through the integrated surveillance tool and the proposed national rabies cases database. Testing and participatory review (piloting) of this strategy (shown in Figure 1 as next steps) is encouraged to generate learning points from experiences before countrywide scale out.

Conclusion

The paper highlights the significance of the involvement of One Health stakeholders in designing a template for an electronic IBCM system and its implementation strategies for effective surveillance of rabies in Uganda. Representatives of various professional disciplines and sectors agree to the implementation of IBCM to harness its benefits. They have, through a participatory process, developed an IBCM template with data elements for both the animal and human sectors that if implemented, will enhance rabies surveillance, judicious use of the scarce PEP and subsequently reduce the cost of rabies control in the developing countries. In addition, it is hoped that by implementing such a surveillance system data quality in the national database will be enhanced and ultimately contribute to the breaking of the “cycle of neglect” of rabies.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

SO: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. RG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. TA: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Resources. SH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Validation. DoA: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. DiA: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. FA: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. PB: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. SL: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. MN: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. JO: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Formal Analysis. FL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. JK: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. CK: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. ML: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. SD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Visualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Funding for this study was obtained from the Swiss National Science Foundation as part of a project entitled, “eRabies -on the way to rabies elimination in Uganda.” (IZSTZ0_208430).

Acknowledgments

The following are acknowledged for their respective contributions to the processes of these workshops: All workshop participants for their invaluable contributions. Dr. Anna Fahrion, Dr. Stephanie Mauti and Dr. Stella Mazeri for their technical presentations during the first workshop. Prof. Umar Kakumba, the former Deputy Vice-Chancellor, Makerere University for officiating and participating in the opening sessions of the first workshop. Prof. James Okwee-Acai, the Deputy Principal, COVAB for officiating and participating in the opening sessions of the first workshop. Dr. Andrew Kambugu, the Executive Director, Infectious Diseases Institute for officiating and participating in the opening sessions of the first workshop.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fitd.2025.1662211/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Hampson K, Coudeville L, Lembo T, Sambo M, Kieffer A, Attlan M, et al. Estimating the global burden of endemic canine rabies. PloS Negl Trop Dis. (2015) 9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003709

2. World Health Organisation. WHO guide for rabies pre and post exposure prophylaxis in humans (2014). Available online at: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/searo/India/health-topic-pdf/pep-prophylaxis-guideline-15-12-2014.pdf?sfvrsn=8619bec3_2 (Accessed June 25, 2024).

3. World Health Organisation. WHO Expert Consultation on Rabies Third report (2018). Available online at: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/272364/9789241210218-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (Accessed June 26, 2024).

4. MAAIF, and MoH. Uganda ministry of agriculture, animal industry and fisheries (MAAIF) and ministry of health (MoH); national rabies elimination strategy (NRES) for dog mediated rabies in Uganda. (2025). (Entebbe: MAAIF) pp. 2025–30. pp. 2025–30.

5. Omodo M, Ar Gouilh M, Mwiine FN, Okurut ARA, Nantima N, Namatovu A, et al. Rabies in Uganda: Rabies knowledge, attitude and practice and molecular characterization of circulating virus strains. BMC Infect Dis. (2020) 20. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-4934-y

6. World Health Organisation. Zero by 30: the global strategic plan to end human deaths from dog-mediated rabies by 2030 (2018). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241513838 (Accessed June 25, 2024).

7. United Nations. United nations sustainable development goals (2015). Available online at: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (Accessed June 25, 2024).

8. Government of Uganda. Third national development plan (NDPIII) 2020/21 – 2024/25 (2020). Available online at: https://www.npa.go.ug/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/NDPIII-Finale_Compressed.pdf (Accessed June 25, 2024).

9. Hartnack S. Animal health is often ignored, but indispensable to the human right to health. Int J Equity Health. (2022) 21:3. doi: 10.1186/s12939-021-01613-0

10. Scott TP, Coetzer A, Fahrion AS, and Nel LH. Addressing the disconnect between the estimated, reported, and true rabies data: The development of a regional African Rabies Bulletin. Front Vet Sci. (2017) 4:18. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2017.00018

11. Taylor LH, Hampson K, Fahrion A, Abela-Ridder B, and Nel LH. Difficulties in estimating the human burden of canine rabies. Acta Trop. (2017) 165:133–40. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2015.12.007

12. Stärk KDC, Arroyo Kuribreña M, Dauphin G, Vokaty S, Ward MP, Wieland B, et al. One Health surveillance - More than a buzz word? Prev Vet Med. (2015) 120:124–30. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2015.01.019

13. Food and Agriculture Organisation. Joint Tripartite (FAO, OIE, WHO) and UNEP Statement Tripartite and UNEP support OHHLEP’s definition of “One Health.” (2021). Available online at: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/54a0f96f-066e-4a16-a186-1a4bbd9d9303/content (Accessed June 26, 2024).

14. Zinsstag J, Hediger K, Osman YM, Abukhattab S, Crump L, Kaiser-Grolimund A, et al. The promotion and development of one health at swiss TPH and its greater potential. Diseases. (2022) 10:65. doi: 10.3390/diseases10030065

15. Octaria R, Salyer SJ, Blanton J, Pieracci EG, Munyua P, Millien M, et al. From recognition to action: A strategic approach to foster sustainable collaborations for rabies elimination. PloS Negl Trop Dis. (2018) 12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006756

16. Acharya KP, Acharya N, Phuyal S, Upadhyaya M, and Steven L. One-health approach: A best possible way to control rabies. One Health. (2020) 10:100161. doi: 10.1016/J.ONEHLT.2020.100161

17. World Health Organisation. (2024). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/rabies (Accessed October 15, 2025).

18. Swedberg C. An intersectoral approach to enhance surveillance and guide rabies control and elimination programs. (2023). (Glasglow: University of Glasglow)

19. Swedberg C, Mazeri S, Mellanby RJ, Hampson K, and Chng NR. Implementing a one health approach to rabies surveillance: lessons from integrated bite case management. Front Trop Dis. (2022) 3:829132. doi: 10.3389/fitd.2022.829132

20. Fèvre EM, Kaboyo RW, Persson V, Edelsten M, Coleman PG, and Cleaveland S. The epidemiology of animal bite injuries in Uganda and projections of the burden of rabies. Trop Med Int Health. (2005) 10:790–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01447.x

21. Lushasi K, Steenson R, Bernard J, Changalucha JJ, Govella NJ, Haydon DT, et al. One health in practice: using integrated bite case management to increase detection of rabid animals in Tanzania. Front Public Health. (2020) 8:13. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00013

22. Rysava K, Miranda ME, Zapatos R, Lapiz S, Rances P, Miranda LM, et al. On the path to rabies elimination: The need for risk assessments to improve administration of post-exposure prophylaxis. Vaccine. (2019) 37:A64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.11.066

23. Undurraga EA, Meltzer MI, Tran CH, Atkins CY, Etheart MD, Millien MF, et al. Cost-effectiveness evaluation of a novel integrated bite case management ana for the control of human rabies, Haiti 2014-2015. Am J Trop Med Hygiene. (2017) 96:1307–17. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0785

24. Lapiz SMD, Miranda MEG, Garcia RG, Daguro LI, Paman MD, et al. Implementation of an Intersectoral Program to Eliminate Human and Canine Rabies: The Bohol Rabies Prevention and Elimination Project. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. (2012) 6(12):e1891. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001891

25. Busch MD, Jean-Baptiste E, Person PF, and Vaughn LM. Activating social change together: A qualitative synthesis of collaborative change research, evaluation and design literature. Gateways. (2019) 12. doi: 10.5130/ijcre.v12i2.6693

26. Vaughn LM and Jacquez F. Participatory research methods – choice points in the research process. J Particip Res Methods. (2020) 1. doi: 10.35844/001c.13244

27. Rysava K, Espineda J, Silo EAV, Carino S, Aringo AM, Bernales RP, et al. One health surveillance for rabies: A case study of integrated bite case management in albay province, Philippines. Front Trop Dis. (2022) 3:787524. doi: 10.3389/fitd.2022.787524

28. Wilson E. Community-based participatory action research. In: Handbook of research methods in health social sciences. Singapore: Springer (2019). p. 285–98. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_87

29. Minkler M and Wallerstein N. Community based participatory research for health: Process to outcomes. Second. San Francisco: Jossey Bass (2008).

30. Nana SD, Duboz R, Diagbouga PS, Hendrikx P, and Bordier M. A participatory approach to move towards a One Health surveillance system for anthrax in Burkina Faso. PloS One. (2024) 19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0304872

31. DHIS2. DHIS2 for one health . Available online at: https://dhis2.org/one-health/ (Accessed October 15, 2025).

32. World Health Organisation. Control of neglected tropical diseases - rabies diagnosis . Available online at: https://www.who.int/teams/control-of-neglected-tropical-diseases/rabies/diagnosis (Accessed April 16, 2025).

33. NOHP. National one health platform (NOHP) Uganda one health strategic plan 2018-2022. (2018). (Kampala)

34. Atuheire CGK, Okwee-Acai J, Taremwa M, Terence O, Ssali SN, Mwiine FN, et al. Descriptive analyses of knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding rabies transmission and prevention in rural communities near wildlife reserves in Uganda: a One Health cross-sectional study. Trop Med Health. (2024) 52:48. doi: 10.1186/s41182-024-00615-2

35. Lechenne M, Mindekem R, Madjadinan S, Oussiguéré A, Moto DD, Naissengar K, et al. The importance of a participatory and integrated one health approach for rabies control: the case of N’Djaména, Chad. Trop Med Infect Dis. (2017) 2:43. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed2030043

36. Brookes VJ and Ward MP. Expert opinion to identify high-risk entry routes of canine rabies into papua new Guinea. Zoonoses Public Health. (2017) 64:156–60. doi: 10.1111/zph.12284

37. Godlonton J. Traditional and cultural beliefs, factors influencing post exposure treatment. In: Proceedings of the southern and eastern african rabies group/world health organization meeting (2001). (Lilongwe: WHO). Available online at: https://www.mediterranee-infection.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/SEARG-report-2001.pdf.

38. World Health Organisation, F, A. O. of the U. N. U. N. E. P, and W. O. for A. H. A guide to implementing the One Health Joint Plan of Action at national level (2023). Available online at: https://www.woah.org/app/uploads/2023/12/guide-to-implement-the-oh-jpa-v19-web.pdf (Accessed April 16, 2025).

39. Thornber PM, Rubira RJ, and Styles DK. Humane killing of animals for disease control purposes. Rev Scientifique Technique l’OIE. (2014) 33:303–10. doi: 10.20506/rst.33.1.2279

40. International Rabies Taskforce. React app . Available online at: https://rabiestaskforce.com/toolkit/react-app (Accessed April 23, 2025).

41. Stephen C and Stemshorn B. Leadership, governance and partnerships are essential One Health competencies. One Health. (2016) 2:161–3. doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2016.10.002

42. Ross YB, Vo CD, Bonaparte S, Phan MQ, Nguyen DT, Nguyen TX, et al. Measuring the impact of an integrated bite case management program on the detection of canine rabies cases in Vietnam. Front Public Health. (2023) 11:1150228. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1150228

Keywords: rabies, Uganda, One Health, IBCM, participatory, integrated, zoonotic, surveillance

Citation: Okech SG, Ghimire R, Odoch T, Hartnack S, Agado D, Akankwatsa D, Apio F, Babirye P, Lunkuse SM, Nakanjako MF, Opolot J, Lohr F, Kiguli J, Kankya C, Lechenne M and Dürr S (2025) Participatory approach in designing a One Health rabies surveillance form for integrated bite case management in Uganda. Front. Trop. Dis. 6:1662211. doi: 10.3389/fitd.2025.1662211

Received: 09 July 2025; Accepted: 29 October 2025;

Published: 19 November 2025.

Edited by:

Nobuo Saito, Nagasaki University, JapanReviewed by:

Frank Busch, Friedrich Loeffler Institute, GermanyKatinka De Balogh, Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, Italy

Copyright © 2025 Okech, Ghimire, Odoch, Hartnack, Agado, Akankwatsa, Apio, Babirye, Lunkuse, Nakanjako, Opolot, Lohr, Kiguli, Kankya, Lechenne and Dürr. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Samuel George Okech, c2FtdWVsLm9rZWNoQHVuaWJlLmNo; Ymxlc3NlZHNnb0BnbWFpbC5jb20=

Samuel George Okech

Samuel George Okech Rabina Ghimire

Rabina Ghimire Terence Odoch

Terence Odoch Sonja Hartnack4,5

Sonja Hartnack4,5 Dickson Akankwatsa

Dickson Akankwatsa Priscilla Babirye

Priscilla Babirye Frederic Lohr

Frederic Lohr Juliet Kiguli

Juliet Kiguli Clovice Kankya

Clovice Kankya Monique Lechenne

Monique Lechenne Salome Dürr

Salome Dürr