Abstract

GmcA is a FAD-containing enzyme belonging to the GMC (glucose-methanol-choline oxidase) family of oxidoreductases. A mutation in the Rhizobium leguminosarum gmcA gene was generated by homologous recombination. The mutation in gmcA did not affect the growth of R. leguminosarum, but it displayed decreased antioxidative capacity at H2O2 conditions higher than 5 mM. The gmcA mutant strain displayed no difference of glutathione reductase activity, but significantly lower level of the glutathione peroxidase activity than the wild type. Although the gmcA mutant was able to induce the formation of nodules, the symbiotic ability was severely impaired, which led to an abnormal nodulation phenotype coupled to a 30% reduction in the nitrogen fixation capacity. The observation on ultrastructure of 4-week pea nodules showed that the mutant bacteroids tended to start senescence earlier and accumulate poly-β-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) granules. In addition, the gmcA mutant was severely impaired in rhizosphere colonization. Real-time quantitative PCR showed that the gmcA gene expression was significantly up-regulated in all the detected stages of nodule development, and statistically significant decreases in the expression of the redoxin genes katG, katE, and ohrB were found in gmcA mutant bacteroids. LC-MS/MS analysis quantitative proteomics techniques were employed to compare differential gmcA mutant root bacteroids in response to the wild type infection. Sixty differentially expressed proteins were identified including 33 up-regulated and 27 down-regulated proteins. By sorting the identified proteins according to metabolic function, 15 proteins were transporter protein, 12 proteins were related to stress response and virulence, and 9 proteins were related to transcription factor activity. Moreover, nine proteins related to amino acid metabolism were over-expressed.

Introduction

Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae is an aerobic, Gram-negative, nitrogen-fixing bacterium that can live under the conditions of microaerobe, aerobe and form symbiotic relationships with Pisum sativum (pea) and Vicia cracca (vetch) under the condition of nitrogen limitation (Karunakaran et al., 2009). Organisms of this genus play a critical role in soil fertility, inducing the formation of symbiotic nodules on the roots of leguminous plants, where bacteroids reduce atmospheric nitrogen to ammonia available for plant uptake (Bhat et al., 2015). The symbiosis between rhizobia and legumes can be characterized by a mutual exchange of signal molecules between the two partners (Janczarek et al., 2015; López-Baena et al., 2016). After attachment of the bacteria to the plant root, the plant supports bacterial infection via host-derived infection threads (Haney and Long, 2010). Successful nodulation requires the activation of cell division in the cortex to form the nodule primordium (Blanco et al., 2009). In nodules, the nitrogenase enzyme, which is extremely sensitive to oxygen, has a low turnover number and a large requirement of chemical energy in the form of ATP and reducing potential (Clarke et al., 2011; Okazaki et al., 2015). In addition to reducing N2 and protons, nitrogenase can also reduce several small, non-physiological substrates, including a wide array of carbon-containing compounds (Seefeldt et al., 2013). It was found that uptake hydrogenases allow rhizobia to recycle the hydrogen generated in the nitrogen fixation process within the legume nodule (Baginsky et al., 2002).

Oxidoreductases catalyze a large variety of specific reduction, oxidation, and oxyfunctionalization reactions, which are important in redox processes, transferring electrons from a reductant to an oxidant (Hollmann and Schmid, 2004; Jeelani et al., 2010). Oxidoreductases included laccases, GMC (glucose-methanol-choline) oxidoreductases, copper radical oxidases and catalases (Beckett et al., 2015). The family of GMC flavoprotein oxidoreductases, which includes glucose/alcohol oxidase and glucose/choline dehydrogenase from prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms, was first outlined by Cavener (1992). Members of the GMC oxidoreductase family share a common structural backbone of an adenine-dinucleotide-phosphate-binding βαβ-fold close to their amino terminus (Iida et al., 2007). The group of GMC flavoprotein oxidoreductases encompasses glucose oxidase from the mold Aspergillus niger, the glucose dehydrogenase from Thermoplasma acidophilum and Drosophila melanogaster, methanol oxidase from yeast Hansenula polymorpha, and choline dehydrogenase from Escherichia coli (Ahmad et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2013). In the leaf beetle subtribe Chrysomelina sensu stricto, GMC oxidoreductases enabled chemical defenses and were important for adaptive processes in plant–insect interactions (Rahfeld et al., 2014). In E. coli, choline dehydrogenase catalyzes the flavin-dependent, two-step oxidation of choline to glycine betaine, which acts as an osmoprotectant compatible solute that accumulates when the cells are exposed to drastic environmental changes in osmolarity (Yilmaz and Bülow, 2010). However, little is known about the functional diversity of the rhizobium GMC family.

Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae, which has been widely used as a model to study nodule biochemistry, is able to nodulate and fix nitrogen in symbiosis with several legumes (Karunakaran et al., 2009). Here, we investigated the roles of a GMC oxidoreductase GmcA in free-living bacteria and during nitrogen-fixing symbiosis on pea by analyzing the phenotypes of a mutant strain. Proteome analysis provides clues to explain the differences between the gmcA mutant and wild-type nodules.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Growth and Media

The strains, plasmids and primers used in this study are listed in Table 1. Rhizobium strains were grown at 28°C in either Tryptone Yeast extract (TY) (Beringer and Hopwood, 1976) or Acid Minimal Salts medium (AMS) (Poole et al., 1994) with D-glucose (10 mM) as a carbon source and NH4Cl (10 mM) as a N source (referred to as AMS Glc/NH4+). For growth and qRT-PCR experiments, cells were grown in AMS Glc/NH4+. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations (μg/mL): ampicillin (Amp), 50; gentamicin (Gm), 20; kanamycin (Km), 20; neomycin (Neo), 80; spectinomycin (Spe), 100; streptomycin (Str), 500; tetracycline (Tc), 5. Strains were grown at 28°C with shaking (200 rpm) for liquid media. To monitor culture growth, optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was measured on three independent cultures.

TABLE 1

| Strains | Description | |

| RL3841 | Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae, Strr | |

| RLgmcA | Rl3841 gmcA:pk19mob, Strr Neor | |

| RLgmcA (pBBRgmcA) | RLgmcA carrying gmcA gene, Strr Neor Gmr | |

| Plasmids | Description | |

| pK19mob | pK19mob pUC19 derivative lacZ mob; Kmr | |

| pRK2013 | Helper plasmid for mobilizing plasmids; Kmr | |

| pKgmcA | gmcAF/gmcAR PCR product in pK19mob, Kmr | |

| pBBRgmcA | cgmcAF/cgmcAR PCR product in pBBR1MCS-5, Gmr | |

| Primer | Description | Sequence1 |

| gmcAF | Sense primer for pRL100444 (gmcA) mutation | TTTAGATCTGGCGGGTTCCTTTGCGGTAA |

| gmcAR | Antisense prime for pRL100444 (gmcA) mutation | TTTCTGCAGTCAGCTCACCGGTCGCCTTT |

| MgmcA | Mapping PCR primer for gmcA gene | CGCCCGACGGATTGTAGAAT |

| pK19A | pK19mob mapping primer | ATCAGATCTTGATCCCCTGC |

| pK19B | pK19mob mapping primer | GCACGAGGGAGCTTCCAGGG |

| gyrB1-F | Sense primer for qRT-PCR of GyrB1 | GGCATCACCAAAAGGGAAAA |

| gyrB1-R | Antisense primer for qRT-PCR of GyrB1 | GCGAGGAGAATTTCGGATCA |

| cgmcAF | Sense primer for gmcA complementation | TTTGGTACCAGCTCACTGTCGATCTCTCC |

| cgmcAR | Antisense prime for gmcA complementation | TTTTCTAGACCTTTATCCGGTTGAGCTGG |

| QgmcA -for | Sense primer for qRT-PCR of gmcA | CGCCGCCTCGCTCGGCAAGA |

| QgmcA-rev | Antisense primer for qRT-PCR of gmcA | ATGCTCATGGAACTGCGAAG |

| gyrB1-F | gyrB1 primers for qRT-PCR | GGCATCACCAAAAGGGAAAA |

| gyrB1-R | GCGAGGAGAATTTCGGATCA | |

| QkatG-F | katG primers for qRT-PCR | GCAACTATTACGTCGGTCTG |

| QkatG-R | TCTCATCGATGACATTTTCC | |

| QkatE-F | katE primers for qRT-PCR | CTCTCATCGATGACTTCCAT |

| QkatE-R | GGGACTCATATGTTTCGAAG | |

| QorhB_F | Sense primer for qRT-PCR of orhB | CGGGCAGGCTGACATTGAGG |

| QorhB_R | Antisense primer for qRT-PCR of orhB | GCTGCTCAGAGAAAGATCAC |

| QhmuS-F | hmuS primers for qRT-PCR | AAGACCAGTCGCAGGAATTT |

| QhmuS-R | GAAGAACTCATGCGTATCGG | |

| QnifD_F | Sense primer for qRT-PCR of nifD | GCAACTATTACGTCGGTCTG |

| QnifD_R | Antisense primer for qRT-PCR of nifD | TCTCATCGATGACATTTTCC |

| QfdxB_F | Sense primer for qRT-PCR of fdxB | ATGGCGAAGACGACTTTAAT |

| QfdxB_R | Antisense primer for qRT-PCR of fdxB | ATGAGTCTGGCAGTTCTTGG |

Strains, plasmids, and primers.

1Restriction sites in primer sequences are underlined.

Construction and Complementation of the gmcA Gene Mutant of R. leguminosarum 3841

Primers gmcAF and gmcAR were used to PCR amplify an internal region of the gmcA gene from R. leguminosarum bv. viciae 3841 genomic DNA (Johnston and Beringer, 1975). The 650-bp gmcA PCR product was cloned into the PstI and XbaI sites of pK19mob, resulting in plasmid pKgmcA. The plasmid pKgmcA was conjugated with R. leguminosarum bv. viciae 3841 using pRK2013 as a helper plasmid, as previously described (Figurski and Helinski, 1979; Karunakaran et al., 2010). Insertions into the gmcA gene of strain RL3841 were selected by neomycin resistant AMS medium with 30mM pyruvate as a sole carbon source and confirmed by PCR using MgmcA and a pK19mob-specific primer (either pK19A or pK19B) (Karunakaran et al., 2010).

To complement the gmcA mutant, primers cgmcAF and cgmcAR were used to amplify the complete gmcA gene from strain RL3841. The PCR product was digested with KpnI and XbaI and cloned into pBBR1MCS-5, resulting in plasmid pBBRgmcA. Plasmid pBBRgmcA was conjugated into the mutant strain RLgmcA using pRK2013 as a helper plasmid to provide the transfer genes, as previously described (Karunakaran et al., 2010).

Hydrogen Peroxide Resistance Activity

Logarithmic phase cultures of mutant strain RLgmcA and wild-type RL3841 were collected and washed twice in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (1×; 136 mM NaCl, 2.6 mM KCl, 8.0 mM Na2HPO4, and 1.5 mM KH2PO4). Cells with an optical density (OD600) 1 were treated with H2O2 at different concentrations (0, 1, 5, and 10 mmol/L) for 1 h. Strains were thoroughly washed with distilled water to remove any remaining oxidant, and the diluted TY plate method was used to evaluate the bacterial survival rate. The experiment consisted of three independent experiments, each of which had three repeats, and statistical differences were analyzed with one-way ANOVA (P < 0.05).

Enzyme Activity Experiments

For analysis of glutathione reductase and glutathione peroxidase activities, logarithmic phase cultures of mutant strain RLgmcA and wild-type RL3841 with an optical density (OD600) 1 were collected, and treated with 5 mM H2O2 for 1 h. H2O2-treated PBS cells were collected by centrifugation at 5,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C. The cells were held in an ice-water bath and sonicated for 15 min. The sonicate was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. Glutathione reductase and glutathione peroxidase activities were determined using a peroxidase assay kit (Beyotime, China). The experiment consisted of three independent experiments, each of which had three repeats, and statistical differences were analyzed with one-way ANOVA (P < 0.05).

Plant Growth and Microscope Study of Nodules

Pea seeds were surface sterilized in 95% ethanol for 30 s and then immersed in a solution of 2% sodium hypochlorite for 10 min. R. leguminosarum bv. viciae strains were inoculated with 107 CFU per seed at the time of sowing. Plants were incubated in a controlled-environment chamber with an 18-h photoperiod (day/night temperature, 22 and 20°C). For dry weight determination, plants were grown in a 2-L beaker filled with sterile vermiculite, watered with nitrogen-free nutrient solution and harvested at 7 weeks (Cheng et al., 2017). The shoot was removed from the root and dried at 70°C in a dry-heat incubator for 3 days before being weighed. Acetylene reduction was determined at flowering (4 weeks) in peas, as previously described (Allaway et al., 2000). The experiment consisted of two independent experiments, each of which had five repeats, and statistical differences were analyzed with one-way ANOVA (P < 0.05).

Nodules at 4 weeks post infection were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde and postfixed in 1.5% osmium tetroxide. Root nodules were sectioned and were then stained with toluidine blue. Ultra-thin sections stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate were observed using a Hitachi H-7100 transmission electron microscope (Yan et al., 2004). For light microscopy, thick sections were cut on a microtome and stained.

Rhizosphere Colonization

Rhizosphere colonization assays were performed as previously described (Cheng et al., 2017). Pea seedlings were grown for 7 days, as described above, for acetylene reduction, and inoculated with RLgmcA and RL3841 in the cfu ratios 1000:0, 0:1000, 1000:1000, and 10000:1000. After 7 days (14 days after sowing), shoots were cut-off and 20 mL of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was added to the roots and vortexed for 15 min at speed 10 (Karunakaran et al., 2006). After vortexing, the samples were serially diluted and plate counted on TY medium plates containing either streptomycin (for wild-type RL3841 and mutant RLgmcA together) or streptomycin and neomycin (for RLgmcA), giving the total number of viable rhizosphere- and root-associated bacteria (Barr et al., 2008). Each treatment consisted of 10 replications, and statistical differences were analyzed with one-way ANOVA (P < 0.05).

RNA Isolation and Quantitative Reverse Transcription–PCR (RT-PCR)

Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR was used to determine differences in the expression of genes. Cell samples were collected from free-living R. leguminosarum cultivated in AMS liquid medium, or free-living cells treated with 5 mM H2O2 for 1 h or root nodules, which were harvested from pea that had been inoculated with R. leguminosarum strains at 2, 4, and 6 weeks. The nodules of plants were harvested and grinded into a regular fine powder with liquid nitrogen. Total RNA of each sample was extracted using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen) and quantified by NanoDrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific) (Smith et al., 1985). cDNA was prepared using SuperScriptTM II reverse transcriptase and random hexamers. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using the SYBR Premix ExTaq (Takara, Dalian, China) on the BIO-RAD CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System. Primers for katG, katE, hmuS, ohrB, rhtA, and nifD are detailed in Table 1. Gyrb1 was used as a reference housekeeping gene and the obtained data were analyzed as previously described (Prell et al., 2009). Statistical analysis of data sets was performed using REST (Pfaffl et al., 2002).

Protein Extraction and LC-MS/MS Analysis

The 4-week-nodule samples were grinded into cell powder in liquid nitrogen. The cell powder was transferred to a 5-mL centrifuge tube. Four volumes of lysis buffer (8 M urea, 1% protease inhibitor cocktail) was then added to the cell powder, and the slurry was sonicated three times on ice using a high intensity ultrasonic processor. Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 12,000 g for 10 min at 4°C, the supernatant was collected, and the protein content was determined using BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockland, IL, United States). The resulting proteins were reduced by 5 mM dithiothreitol at 56°C for 30 min, and then alkylated in 11 mM iodoacetamide for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. Each protein sample was then diluted by 100 mM tetraethyl ammonium bromide (TEAB) to obtain a urea concentration of less than 2 and 1:100 trypsin-to-protein mass ratio for a second digestion of 4 h. Following trypsin digestion, the peptides then were desalted by Strata X C18 SPE column and vacuum-dried. The peptides were reconstituted in 0.5 M TEAB and processed according to the manufacturer’s instructions of the tandem mass tag (TMT) kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, United States). Concisely, one unit of TMT reagent was dissolved and reconstituted in acetonitrile. The peptide mixtures were then incubated at room temperature for 2 h and pooled, desalted and dried by vacuum centrifugation.

The tryptic peptides were dissolved in solvent A (0.1% formic acid in aqueous solution) and loaded directly onto a reversed phase analytical column (75 μm i.d. × 15 cm length). The loaded material was eluted from this column in a linear gradient of 6–22% solvent B (0.1% formic acid in 98% acetonitrile) over 26 min, 23–35% in 8 min, climbing to 80% in 3 min and holding at 80% for 3 min with a flow rate of 400 nL/min. The MS proteomics data were deposited to NSI source, followed by tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) by using a Q ExactiveTM Plus (Thermo) coupled online to the ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC). The electrospray voltage was set to 2.0 kV. For the full scan mode, the m/z scan range was from 350 to 1,800. The intact peptides were detected in the Orbitrap at a resolution of 70,000. Peptides were selected to run MS/MS analysis using NCE setting as 28 and the fragments were measured using a resolution of 17,500 in the Orbitrap. The MS analysis alternated between MS and data-dependent tandem MS scans with 15.0 s dynamic exclusion. Automatic gain control (AGC) was set to accumulate 5 × 104 ions with the Fixed first mass of 100 m/z. Experiments were conducted in triplicate.

Data Analysis

The resulting MS/MS data were processed and prepared for a database search using the MaxQuant version 1.5.2.8 (Cox and Mann, 2008). The resulting tandem mass spectra were searched against the R. leguminosarum genome database concatenated with a reverse decoy database (Young et al., 2006). Trypsin/P was specified as the cleavage enzyme allowing up to four missing cleavages. The precursor mass tolerance was set to 20 ppm for the first search and 5 ppm for the main search, and the tolerance of the ions was set to 0.02 Da for fragment ion matches. Carbamidomethylation of cysteines was considered as a fixed modification, and oxidation of methionine was specified as variable modifications. A false discovery rate (FDR) of 1% was specified, and the minimal peptide score for modified peptides was set to 40. Protein expression was analyzed statistically using Student’s t-tests (p < 0.05). Up-regulated and down-regulated proteins were defined as having fold changes (FC) > 1.2 and <0.83, respectively.

Results

Bioinformatic Analysis of the R. leguminosarum gmcA Gene

Rhizobium leguminosarum gmcA gene (pRL100444) is predicted to encode a 550-amino acid polypeptide with an expected molecular mass of 60.5 kDa and a pI value of 8.19 (Young et al., 2006). The amino acid sequence of GmcA contained a consensus motif of a FAD/NAD(P)-binding domain in its N-terminal part and two GMC oxidoreductase signature patterns (Supplementary Figure S1), suggesting that GmcA should be included into the glucose-methanol-choline (GMC) flavin-dependent oxidoreductase family.

Antioxidation Analysis of a R. leguminosarum gmcA Mutant

To confirm the function of the gmcA gene in growth performance, antioxidation and symbiotic nitrogen fixation ability, a mutant RLgmcA strain of this gene was constructed by single crossover homologous recombination. In liquid AMS minimal medium with glucose as a carbon source and NH4Cl as a nitrogen source, there is no significant difference in growth between the mutant RLgmcA and wild-type RL3841 (data not shown).

The importance of GmcA for protection against oxidative stress was investigated by carrying out survival assays of the mutant RLgmcA in the presence of oxide hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). The survival rates of RLgmcA were not significantly affected by H2O2 treatments at low concentrations of 0.5 and 1 mmol/L compared with the wild-type RL3841 strain, whereas the antioxidative capacity of mutant RLgmcA was significantly decreased by these treatments with H2O2 at higher concentrations of 5 and 10 mmol/L (Table 2). The role of R. leguminosarum GmcA in controlling protein glutathionylation status was investigated by quantifying glutathione reductase and glutathione peroxidase activities in 5 mM H2O2-induced oxidative stress conditions. The results showed that the glutathione reductase activity of mutant RLgmcA was not different from that of wild-type strain RL3841, but its glutathione peroxidase activity was significantly lower (Table 3). Thus, GmcA may play important roles in oxidative stress resistance and cellular detoxification in R. leguminosarum.

TABLE 2

| Strain | H2O2 (mM) | ||||

| 0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 10.0 | |

| RL3841 | (6.72 ± 0.71) × 108 a | (4.27 ± 0.27) × 108 a | (3.85 ± 0.18) × 108 a | (2.73 ± 0.14) × 107 a | (1.01 ± 0.21) × 107 a |

| RLgmcA | (7.03 ± 1.00) × 108 a | (3.80 ± 0.17) × 108 a | (3.21 ± 0.29) × 108 a | (1.59 ± 0.19) × 107b | (4.07 ± 0.90) × 106b |

Tolerance of R. leguminosarum stains to different concentrations of H2O2.

All data are averages (±SEM) from three independent experiments. a,bDifferent letters indicates the value is significantly different from that of the wild-type RL3841 control (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.05).

TABLE 3

| Strains R. leguminosarum | Glutathione reductase (U/mg protein) | Glutathione peroxidase (U/mg protein) |

| RL3841 | 0.399 ± 0.041a | 0.406 ± 0.029a |

| RLgmcA | 0.408 ± 0.031a | 0.018 ± 0.006b |

| RLgmcA(pBBRgmcA) | 0.409 ± 0.030a | 0.385 ± 0.031a |

Oxidase activity of R. leguminosarum gmcA mutant.

All data are averages (±SEM) from three independent experiments. a,bDifferent letters indicates the value is significantly different from that of the wild-type RL3841 control (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.05).

Pea Rhizosphere Colonization by R. leguminosarum Strains

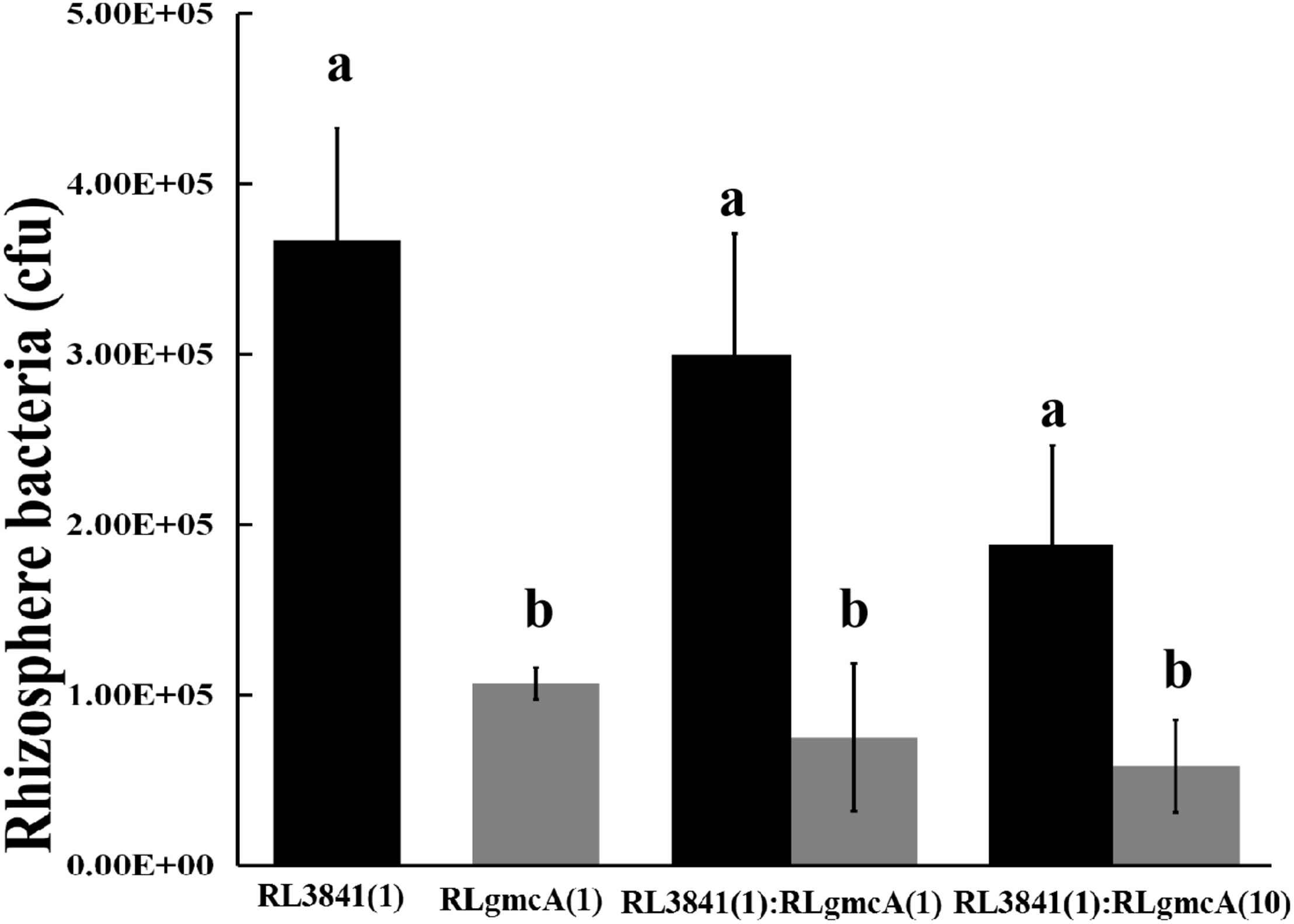

Competition between the gmcA mutant RLgmcA and the wild type RL3841 for growth in the pea rhizosphere was measured by inoculating a low number of bacteria into the pea rhizosphere (103 to 104 bacteria per seedling) and determining total bacteria after 7 days. When the mutant RLgmcA and the wild type RL3841 were inoculated alone into short-term colonization of sterile pea rhizosphere, the percentage of bacteria recovered after 7 days was significantly lower for the mutant than for the wt strain (Figure 1). When inoculated in equal ratios, RLgmcA accounted for only 25% of bacteria recovered (t-test; P ≤ 0.01). Even when strain RLgmcA was inoculated at a 10-fold excess over the wild type, it still accounted for only 41% of bacteria recovered (Figure 1). The decreased ability of the gmcA mutant to grow in a sterile rhizosphere of peas shows that GmcA is essential for colonization of the pea rhizosphere by R. leguminosarum.

FIGURE 1

Competition of the wild type (RL3841) (black bars) and the gmcA mutant (RLgmcA) (gray bars) in sterile rhizospheres. Inoculation ratios are given on the x-axis, with 1 corresponding to 1,000 CFU. Number of bacteria (per plant) recovered from 10 plants (mean ± SEM) are shown. a,bDifferent letters indicate the value is significantly different between mutant RLgmcA and wild-type RL3841 control (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.05).

The Symbiotic Phenotype of R. leguminosarum Strains

To observe the nodulation status and measure nitrogenase activity of the gmcA mutant strain, pea seedlings were inoculated with the mutant RLgmcA or wild-type RL3841. Four weeks later, the number, shape and structure, and acetylene reduction activity (ARA) values of the nodules were measured. No statistically significant difference was observed in the number of nodules per plant between plants inoculated strain RLgmcA and plants inoculated with wild-type RL3841 (Table 4 and Supplementary Figure S2). R. leguminosarum bv. viciae formed determinate nodules on pea, while the gmcA mutant elicited more elongated, rather than spherical, nodules compared to the wild type and showed a 30.36% decrease in ARA and a 40% drop in the dry weight of plants compared to the wild type (Table 4). When recombinant plasmid pBBRgmcA was introduced into mutant RLgmcA, plants inoculated with the resulting strain RLgmcA(pBBRgmcA) formed normal nodules and showed no significant difference in nitrogen-fixing ability and the dry weight of plants compared to the RL3841-inoculated plants (Table 4).

TABLE 4

| Strain | Nodules per plant | Acetylene reduction (μ moles acetylene per plant per h) | Dry weight per plant (g) |

| RL3841 | 137.3 ± 13.2a | 2.24 ± 0.14a | 1.86 ± 0.20a |

| RLgmcA | 131.3 ± 11.3a | 1.56 ± 0.05b | 1.10 ± 0.18b |

| RLgmcA(pBBRgmcA) | 135.5 ± 11.3a | 2.12 ± 0.16a | 1.80 ± 0.16a |

| WC | 0 | 0 | 0.35 ± 0.09c |

Symbiotic behavior of R. leguminosarum gmcA mutant.

All data are averages (±SEM) from ten independent plants. a,b,cDifferent letters indicates the value is significantly different from that of the wild-type RL3841 control (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.05). WC, water control without inoculation.

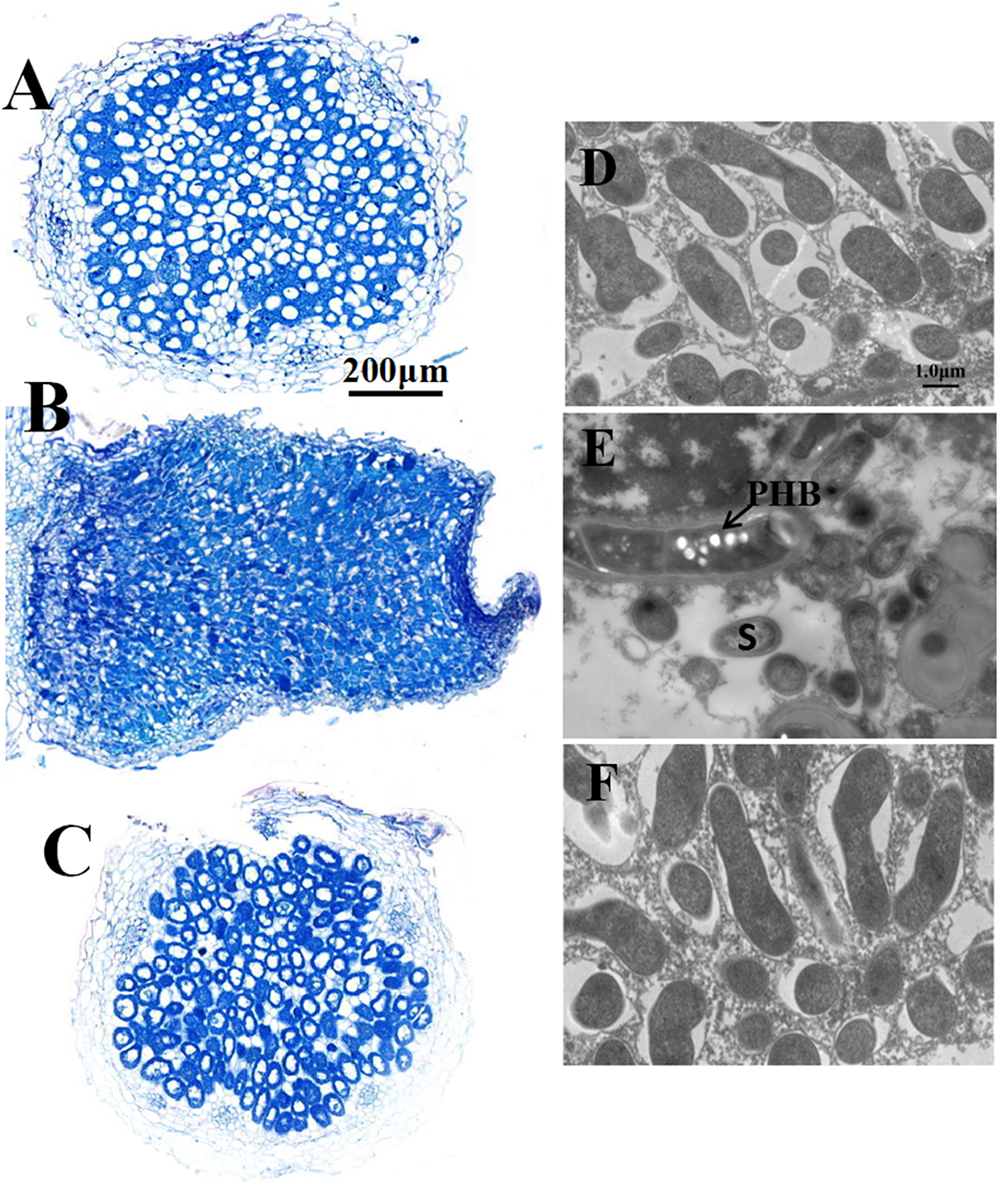

Four-week-old nodules were further examined by both light and electron microscopy. The nodules induced both by wild type RL3841 and by mutant RLgmcA turned blue when stained with toluidine blue. These observations were corroborated by light microscopic analysis. Both the nodules were filled by Rhizobia-infected cells (Figures 2B,C). The ultrastructural structure of the infected cells was observed by transmission electron microscopy. In the mutant infected nodule cells, bacteroids underwent premature senescence. Bacteroids in pea plants inoculated by R. leguminosarum bv. viciae usually did not produce visible PHB granules, but in the mutant bacteroids, the poly-b-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) was also distinctly observed (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2

Structure of 4-week-old pea nodules and bacteroids. Nodules were induced by RLgmcA(pBBRgmcA) (A,D), RLgmcA (B,E), RL3841 (C,F). The wild-type RL3841 forms normal spherical (determinant) nodules (C), while the gmcA mutant forms elongated nodules (B). PHB, poly-β-hydroxybutyrate. S, senescing bacteroid. Scale bars = 200 μm (A–C) and 1 μm (D–F).

Expression Level of the gmcA Gene in Nodules Induced by R. leguminosarum 3841

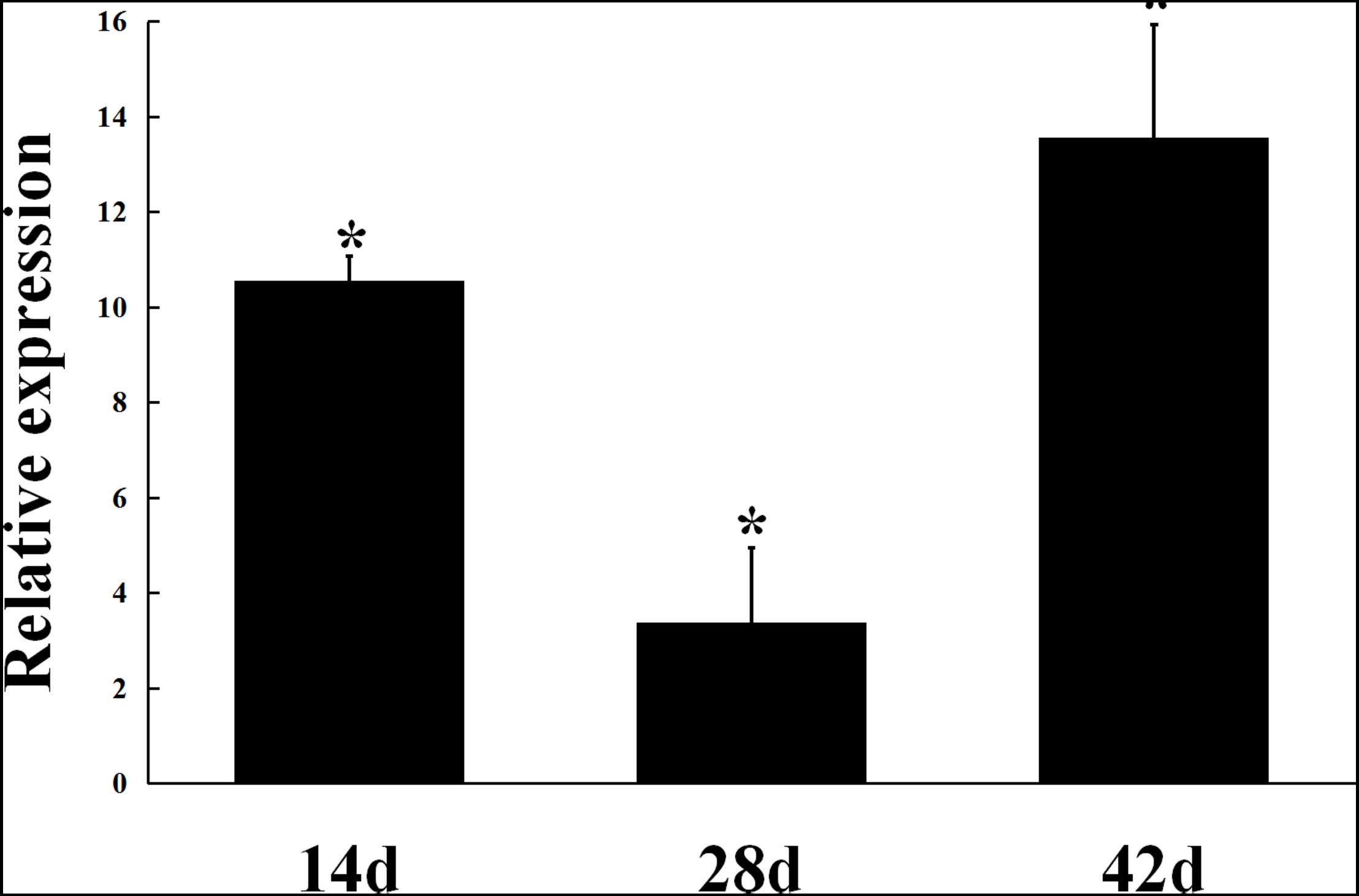

The expression of gmcA was significantly up-regulated in the early stage (14 days), maturation stage (28 days) and late stage (42 days) of nodule development and senescence in comparison to that in free-living cells (Figure 3). During symbiosis, gmcA gene has the highest expression level in nodules at 42 days after inoculation. Thus, these results showed that gmcA gene expression was induced during R. leguminosarum-pea symbiosis and suggest that this gene plays an important role in bacteroid persistence in old nodules.

FIGURE 3

Expression patterns of gmcA gene in symbiotic nodules. Gene expression levels were examined by real-time RT-PCR. Nodules were collected on different days after inoculation with RL3841. Relative expression of gmcA gene in symbiotic nodule bacteroids compared with RL3841 wild type cells growth in AMS Glc/NH4+ medium. Data are the average of three independent biological samples (each with three technical replicates). Superscript asterisk indicates significant difference in relative expression (>2-fold, P ≤ 0.05).

Analysis of the Relative Expression of Genes Involved in Redoxin Production and Nitrogen Fixation in the gmcA Mutant

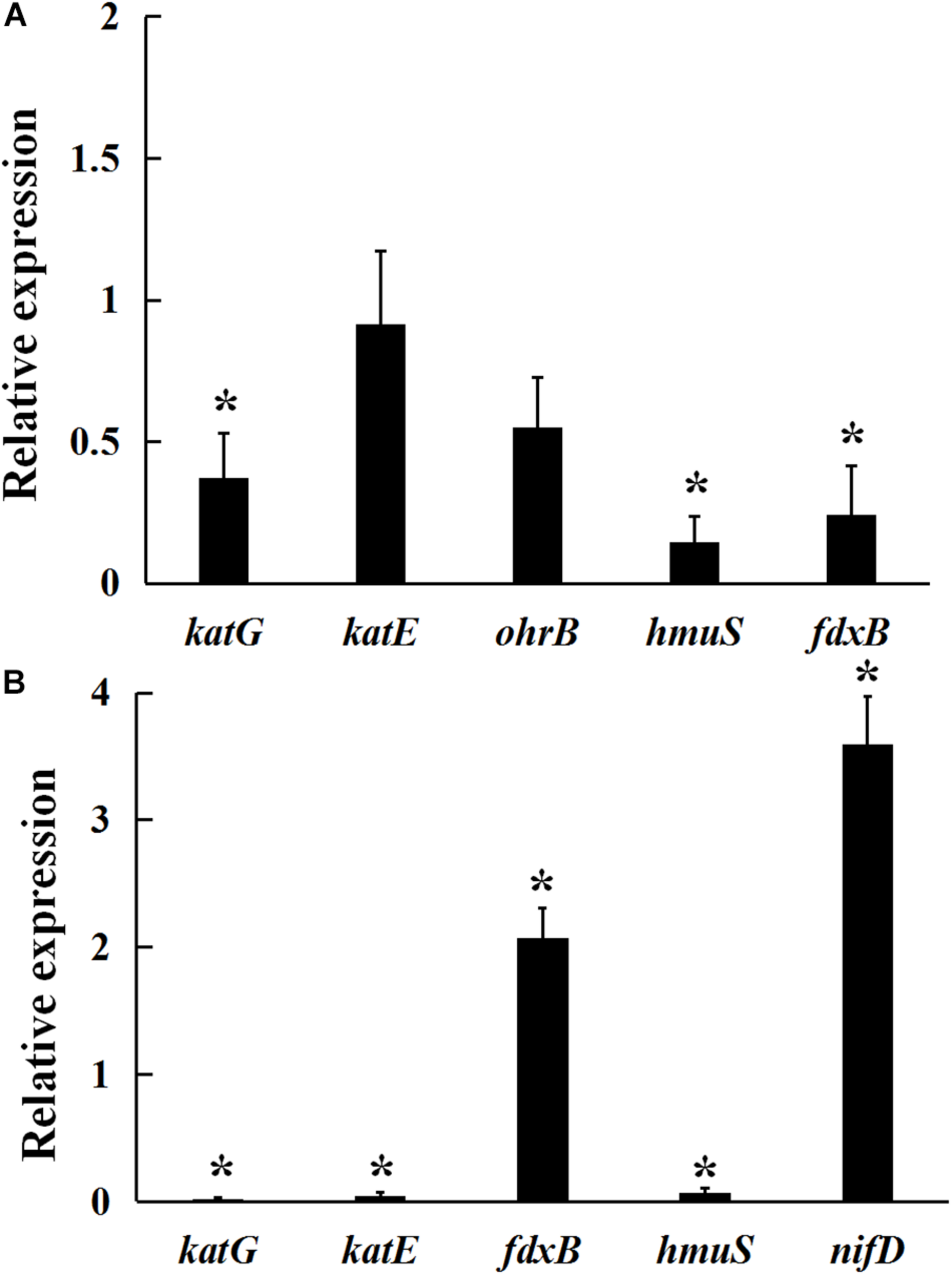

As shown in Figure 4A, under 5 mmol/L H2O2-induced oxidative stress condition, a significant decrease in katG, fdxB, and hmuS gene expression was observed in the gmcA mutant, suggesting that GmcA plays an important role in cellular redox balance. Since a large reduction in the nitrogen-fixing capacity of nodules inoculated with mutant strain was observed, qRT-PCR was used to assess whether the N-fixation system, e.g., nitrogenase genes, was affected in the transcription of ribosomal RNAs in the GmcA-deficient mutant. The expression of nifD and fdxB was analyzed in pea root nodules using qRT-PCR (Figure 4B). Unexpectedly, the expression level of nifD and fdxB was found to be significantly increased in 4-week-old nodules inoculated with gmcA mutant strain compared with control nodules. Thus, GmcA may function in redox balance and antioxidant defense system in the pea root nodules. hmuS gene expression was significantly down-regulated in gmcA mutant, both under H2O2-induced oxidative stress condition and in 4-week-old nodule, suggesting gmcA is involved in iron transport and regulation of iron homeostasis.

FIGURE 4

Relative expression of genes involved in hydrogen peroxide stresses (A) and 4-week-nodule bacteroids (B) in gmcA mutant compared with wild-type RL3841 measured by qRT-PCR. The value of relative gene expression in wild-type strain (A) or bacteroid (B) is given to 1.0, and the ratio was the expression level of each gene in mutant RLgmcA vs. in wild-type RL3841. Data are the average of three independent biological samples (each with three technical replicates). Superscript asterisk indicates significant difference in relative expression (>2-fold for up-expression or <2-fold for down-expression, P ≤ 0.05).

Protein Differential Expression Analysis

A quantitative proteomic approach using UPLC coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC/LC-MS/MS) was performed to compare differential gmcA mutant root bacteroids in response to wild type infection. Proteomics analysis identified peptides derived from a total of 2002 distinct protein groups in gmcA mutant bacteroids and 2000 in wild-type bacteroids, with molecular weights ranging from 7 to 317 kDa. A total of 60 differentially expressed proteins (P < 0.05) were identified. Among these proteins (Table 5), 33 proteins were up-regulated in gmcA mutant nodule bacteroids and 27 proteins were down-regulated. Cell surface protein (RL4381) was absent in the gmcA mutant bacteroids, while invasion associated protein (RL1020) and lipoate-protein ligase B (RL2555) were not found in the wild-type bacteroids. Thirty-two differential protein-encoding genes were localized in plasmids pRL7, pRL8, pRL9, pRL10, pRL11, and pRL12. Cellular localization of the differentially expressed proteins showed that thirty-nine proteins localized to the cytoplasm, thirteen proteins localized to periplasmic space, five proteins located in the outer membrane, two were extracellular proteins, and one protein existed in the inner membrane (Table 5).

TABLE 5

| Gene ID | Gene Name | Cellular localization | Protein description | MW [kDa] | pI | Ratio | P-value |

| Stress response and virulence | |||||||

| RL3853 | Cytoplasmic | FAD-dependent oxidoreductase | 47.38 | 5.71 | 6.15 | 0.0004 | |

| RL4381 | Outermembrane | cell surface protein | 66.06 | 4.46 | 1.58 | NP1 | |

| pRL90097 | pdxA2 | Cytoplasmic | 4-hydroxythreonine-4-phosphate dehydrogenase | 34.66 | 6.39 | 1.23 | 0.0332 |

| pRL100245 | Cytoplasmic | LLM class flavin-dependent oxidoreductase | 38.97 | 5.20 | 1.22 | 0.0082 | |

| pRL80022 | Cytoplasmic | alpha/beta hydrolase | 35.12 | 6.03 | −0.40 | 0.0011 | |

| pRL80023 | cutM | Cytoplasmic | carbon monoxide dehydrogenase subunit M protein | 30.42 | 5.56 | −0.48 | 0.0012 |

| pRL80041 | hisD | Cytoplasmic | Histidinol dehydrogenase | 47.16 | 5.39 | −0.60 | 0.0115 |

| RL1020 | Periplasmic | invasion associated protein | 22.08 | 5.45 | −0.85 | NP2 | |

| pRL120603 | gabD3 | Cytoplasmic | NAD-dependent succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase | 52.53 | 5.29 | −0.74 | 0.0344 |

| pRL90027 | adhA | Cytoplasmic | alcohol dehydrogenase | 37.15 | 5.93 | −0.77 | 0.0008 |

| pRL120056 | mcpR | Cytoplasmic | methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein | 68.73 | 5.01 | −0.77 | 0.0426 |

| pRL90018 | fixN2 | Innermembrane | Putative cytochrome oxidase transmembrane component FixN | 60.90 | 8.98 | −0.82 | 0.0074 |

| Amino acid metabolism | |||||||

| pRL100242 | Cytoplasmic | amino acid synthesis family protein | 21.17 | 6.29 | 1.45 | 0.0159 | |

| pRL110557 | glxB | Cytoplasmic | glutamine amidotransferase | 31.99 | 5.21 | 1.42 | 0.0190 |

| RL0041 | hisE | Cytoplasmic | Phosphoribosyl-ATP pyrophosphatase | 11.51 | 5.19 | 1.30 | 0.0496 |

| pRL100099 | Cytoplasmic | Nif11 family protein | 14.45 | 8.86 | 1.23 | 0.0152 | |

| RL2075 | gatC | Cytoplasmic | Aspartyl/glutamyl-tRNA(Asn/Gln) amidotransferase subunit C | 10.19 | 4.73 | 1.22 | 0.0082 |

| pRL100192 | Outermembrane | glutamate N-acetyltransferase | 20.33 | 6.71 | 1.21 | 0.0024 | |

| pRL90221 | Cytoplasmic | Putative glutamine amidotransferase protein | 28.31 | 5.18 | −0.72 | 0.0244 | |

| Carbohydrate metabolism | |||||||

| pRL110453 | Cytoplasmic | Concanavalin A-like lectin/glucanase domain | 22.05 | 5.00 | 1.25 | 0.0237 | |

| RL0916 | dgoK | Cytoplasmic | 2-dehydro-3-deoxygalactonokinase | 31.49 | 5.69 | −0.73 | 0.0076 |

| RL0874 | RL0874 | Cytoplasmic | aldo/keto reductase | 38.21 | 5.45 | −0.78 | 0.0000 |

| pRL110598 | Cytoplasmic | L-fuconate dehydratase | 47.20 | 5.17 | −0.82 | 0.0137 | |

| pRL120643 | groSp12 | Cytoplasmic | co-chaperone GroES | 11.37 | 5.48 | −0.83 | 0.0003 |

| RL2555 | lipB | Cytoplasmic | lipoate-protein ligase B | 26.70 | 5.22 | −0.99 | NP2 |

| Transporter activity | |||||||

| RL4326 | Periplasmic | Putative transmembrane protein | 98.15 | 5.59 | 1.39 | 0.0122 | |

| RL3066 | Periplasmic | Putative transmembrane protein | 17.22 | 8.09 | 1.35 | 0.0090 | |

| RL2491 | Cytoplasmic | Conserved hypothetical exported protein | 9.75 | 5.38 | 1.28 | 0.0001 | |

| pRL100386 | Periplasmic | VWA domain-containing protein | 74.90 | 4.84 | 1.24 | 0.0122 | |

| RL3065 | Periplasmic | Conserved hypothetical exported protein | 14.77 | 5.88 | 1.23 | 0.0151 | |

| pRL70182 | Periplasmic | Conserved hypothetical exported protein | 36.84 | 5.32 | 1.21 | 0.0265 | |

| pRL80026 | livJ | Periplasmic | ABC transporter substrate-binding protein | 45.36 | 5.81 | −0.33 | 0.0006 |

| pRL80060 | Periplasmic | ABC transporter substrate-binding protein | 29.75 | 5.35 | −0.53 | 0.0007 | |

| pRL80085 | Cytoplasmic | Autoinducer 2 ABC transporter substrate-binding protein | 35.70 | 6.02 | −0.60 | 0.0448 | |

| RL2775 | ropA1 | Outermembrane | Porin | 36.80 | 3.92 | −0.71 | 0.0111 |

| RL4402 | Cytoplasmic | ABC transporter substrate-binding protein | 35.94 | 4.96 | −0.72 | 0.0115 | |

| RL1499 | ropA2 | Outermembrane | Porin | 36.71 | 4.01 | −0.77 | 0.0001 |

| pRL100415 | Periplasmic | ABC transporter substrate-binding protein | 37.92 | 5.17 | −0.79 | 0.0492 | |

| pRL120671 | Periplasmic | nitrate ABC transporter substrate-binding protein | 36.00 | 5.50 | −0.83 | 0.0123 | |

| pRL100325 | fhuA1 | Outermembrane | outer membrane siderophore receptor | 78.19 | 4.64 | −0.83 | 0.0203 |

| Nucleotide metabolism | |||||||

| RL0952 | Cytoplasmic | RNA-binding domain transcriptional regulator | 83.38 | 6.67 | 1.34 | 0.0278 | |

| RL2475 | holB | Cytoplasmic | Putative DNA polymerase III, delta subunit | 36.35 | 5.90 | 1.26 | 0.0409 |

| RL1785 | rplX | Cytoplasmic | 50S ribosomal protein L5 | 11.21 | 10.37 | 1.23 | 0.0038 |

| RL2183 | Cytoplasmic | nucleotidyltransferase | 33.59 | 8.80 | −0.82 | 0.017 | |

| Transcription factor activity | |||||||

| pRL100146 | Periplasmic | transcriptional regulator | 23.94 | 9.57 | 1.33 | 0.0243 | |

| RL4412 | priA | Cytoplasmic | primosome assembly protein PriA | 80.82 | 6.32 | 1.30 | 0.0382 |

| RL3457 | Extracellular | SH3-like domain, bacterial-type; uncharacterized protein | 21.84 | 4.62 | 1.25 | 0.0082 | |

| RL0425 | ptsN | Cytoplasmic | PTS IIA-like nitrogen regulatory protein PtsN | 16.65 | 5.70 | 1.23 | 0.0007 |

| RL1379 | rosR | Cytoplasmic | MucR family transcriptional regulator | 15.62 | 6.96 | 1.22 | 0.0055 |

| RL0133 | Cytoplasmic | YbaB/EbfC family nucleoid-associated protein | 11.42 | 5.18 | 1.22 | 0.0007 | |

| pRL100196 | nifA | Cytoplasmic | nif-specific transcriptional activator | 56.46 | 9.05 | 1.21 | 0.0011 |

| pRL80079 | Cytoplasmic | sugar-binding transcriptional regulator | 35.34 | 5.71 | −0.38 | 0.0072 | |

| pRL80046 | Cytoplasmic | TetR/AcrR family transcriptional regulator | 25.32 | 8.01 | −0.46 | 0.0112 | |

| Unknown function proteins | |||||||

| pRL100106 | Periplasmic | Uncharacterized protein | 28.65 | 6.19 | 1.59 | 0.0363 | |

| RL1874 | Cytoplasmic | Uncharacterized protein | 13.23 | 4.66 | 1.35 | 0.0185 | |

| RL3516 | Extracellular | DUF2076 domain-containing protein | 27.48 | 4.26 | 1.24 | 0.0017 | |

| RL4728 | Periplasmic | DUF1013 domain-containing protein | 26.14 | 5.91 | 1.23 | 0.0005 | |

| RL2820 | Cytoplasmic | Uncharacterized protein | 7.40 | 9.46 | 1.23 | 0.0494 | |

| pRL80010 | Cytoplasmic | Uncharacterized protein | 9.58 | 9.51 | −0.21 | 0.0189 | |

| pRL80005 | Cytoplasmic | Uncharacterized protein | 59.58 | 5.52 | −0.47 | 0.0028 | |

Differential expression proteins in 4-week nodule mutant bacteroids relative to wild-type bacteroids.

Protein expression was analyzed statistically using Student’s t-tests (P < 0.05). Np1, no protein in mutant; Np2, no protein detected in wild type.

By sorting the identified proteins according to metabolic function, most of the differences in expression were found among transporter activity (15 proteins), followed by 12 proteins related to stress response and virulence, 9 proteins related to transcription factor activity, 7 proteins related to amino acid metabolism, 6 proteins related to carbohydrate metabolism, and 4 proteins related to nucleotide metabolism. This change in metabolism was mirrored by corresponding changes in proteins involved in the regulation of transcription, among which, a nif-specific transcriptional activator NifA and a nitrogen regulatory protein PtsN were highly expressed in the mutant bacteroids. The main groups of differentially expressed proteins identified were transport proteins, of which 6 were ABC-type nitrate/nitrite transporters. The result showed gmcA mutant was affected in transport, especially in nitrate transport. Further analysis of the differentially expressed proteins identified a subset involved in stress response and virulence. The number of affected oxidoreductases, cytochrome oxidase, dehydrogenase, hydrolase, dehydrogenase, surface, and invasion associated proteins also suggests that GmcA function in antioxidant capacity in the root nodules and that the loss of these proteins could result in antioxidant defect. Finally, the loss of GmcA resulted in the differential expression of seven proteins with unknown function in the nodule bacteroids.

Discussion

The family of GMC oxidoreductases includes glucose/alcohol oxidase and glucose/choline dehydrogenase. Members of this family catalyze a wide variety of redox reactions with respect to substrates and co-substrates (Sützl et al., 2018). An important issue is that gmcA expression is elevated in nitrogen-fixing bacteroids of the pea root nodules, but the function of GmcA in root nodule bacteria nitrogen fixing system is poorly understood. In this study, we took advantage of a gmcA mutant strain of R. leguminosarum to examine what role GmcA may play in symbiotic nitrogen fixation. Our data demonstrated that GmcA is required for the nodule senescence and cellular detoxification that is affected, regarding its nitrogen fixation capacity and oxidative stress response.

Mutation of R. leguminosarum gmcA did not affect the growth of free-living bacteria but led to decreased antioxidative capacity under the conditions of 5 and 10 mM hydrogen peroxide H2O2. The direct link between GmcA and H2O2 detoxification has been less reported, while in most wood-rotting fungi, the members of GMC oxidoreductase superfamily play a central role in the degradation process because they generate extracellular H2O2, acting as the ultimate oxidizer (Ferreira et al., 2015). Our results suggested that cells with GmcA tolerate internally generated or exogenously applied H2O2. Cellular oxidoreductases catalyze redox processes by transferring electrons from a reductant to oxidant and are important for protection against oxidative stress (Bisogno et al., 2010). The ferredoxin-like protein (FdxB) and iron transport protein HmuS are ubiquitous electron transfer proteins participating in the iron-sulfur cluster biosynthesis and a wide variety of redox reactions (Chao et al., 2005; Gu et al., 2008). In Rhizobium, the peroxidases and the catalases KatG (catalase HPI), KatE (catalase), and OhrB (organic hydroperoxide resistance) were known to participate in the antioxidant defense mechanism against H2O2-induced stress (Vargas Mdel et al., 2003), and the two electron transfer proteins FdxB and HmuS are also involved in a wide variety of redox reactions (Chao et al., 2005; Gu et al., 2008). This cell cytotoxicity was relieved by inducing transcription of antioxidant genes (Jung and Kim, 2003). Expression levels of katG, fdxB, and hmuS genes were significantly down-regulated in the gmcA mutant under H2O2-induced oxidative stress. It has been reported that decreased ferredoxin-NADP(H) oxidoreductase (FNR) results in a more oxidized glutathione pool, while increasing FNR content results in a more reduced glutathione pool (Goss et al., 2012). Glutathione reductase activity in mutant RLgmcA was not different from that wild-type strain, but the absence of GmcA was associated with a 96.5% decrease in cellular glutathione peroxidase activity. Cellular peroxide deficit damages cellular macromolecules by reactive oxygen species (ROS), and glutathione peroxidases are one of the important ROS scavengers in the cell (Islam et al., 2015). The decrease of glutathione peroxidase activity is related to an uncontrolled increase of ROS (Giergiel et al., 2012).

Pea plants inoculated with the gmcA mutant exhibited a large decrease in the nitrogen-fixing activity of root nodules (reduced by more than 30%), although, the protein expression of NifA and PtsN was higher in the mutant bacteroids compared to that of wild type bacteroids. Two genes, nifD and fdxB, involved in metabolism related to nitrogen fixation and bacteroid maturation in pea root nodules (Capela et al., 2006) also had a higher level of expression in the mutant bacteroids. It has been reported that GMC oxidoreductases are involved in extracellular hydrogen peroxide and iron homeostasis (Rohr et al., 2013). Iron is required for symbiotic nitrogen fixation as a key component of multiple ferroproteins involved in this important biological process (Takanashi et al., 2013). hmuS was chosen based on previous studies, which showed that it was involved in iron transport (Chao et al., 2005). hmuS exhibited higher expression level in the mutant bacteroids, demonstrating the involvement of GMC in the regulation of iron homeostasis. Proteomic analysis of the mutant nodule bacteroids indicated that most of the differentially expressed proteins were involved in transporter activity, metabolism, and stress responses. These transporters may aid in regulation of ion and membrane potential homeostasis through their transport of nitrate, which is known to regulate the symbiosis (Vincill et al., 2005). These results indicated that GmcA is involved in a variety of metabolic processes, as has been described in A. niger and E. coli (Etxebeste et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2013).

The electron microscope investigation revealed that gmcA mutant altered the ultrastructure of pea nodules. GmcA can likely play a role in nodule senescence, since senescent parameters such as increased activities of enzymes of amino acid metabolism, PHB production, and an increase in the number of disintegrated bacteroids occurred. In addition, glutathione peroxidase activity dramatically decreased, and amino acid metabolism reflecting arginase activity was increased. R. leguminosarum bv. viciae forms determinate nodules on pea and usually does not produce visible PHB granules during symbiosis. PHB granules occurred in undergoing senescence bacteroids, which indicated that the energy and carbon metabolism has shifted (Xie et al., 2011). The PHB and tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycles both start with acetyl-CoA. Under aerobic conditions, the TCA cycle is responsible for the complete oxidation of acetyl-CoA and formation of intermediates required for ATP production, but under oxygen limitation condition, when there is an inhibition of the TCA cycle by NADH or NADPH, the bacteroids favor PHB synthesis. During PHB synthesis, there is apparently a concomitant reduction in protein synthesis, a process coupled to ATP formation and utilization (Tal et al., 1990). In the symbiosis of the GmcA-deficiency mutant RLgmcA, the low expression of the catalase-peroxidase gene (katG), alpha/beta hydrolase (pRL80022), carbon monoxide dehydrogenase (pRL80023), succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase (pRL120603), and alcohol dehydrogenase (pRL90027) inhibited NAD(P)H oxidase activity. To allow continued operation of the TCA cycle, NAD(P)H was channeled into other biosynthesis reactions, such as PHB synthesis, for acting as reducing equivalents (Xie et al., 2011).

The gmcA gene expression is significantly up-regulated during the whole nodulation process, and its highest expression level occurred at 42 days after inoculation. Moreover, the R. leguminosarum gmcA mutant was unable to compete efficiently in the rhizosphere with its wild-type parent, which shows that bacterial GmcA is important for adaptation to the microenvironment of the plant host. Overall, considering the poor nitrogen-fixing ability of its nodules, the mutant in gmcA gene had a profound influence on the whole nodulation process.

Statements

Data availability statement

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD017485.

Author contributions

GC conceived and designed the study. QZ, SL, and HW performed the experiments. GC, QZ, DH, and XL analyzed the results. GC and QZ wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31772399) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, South-Central University for Nationalities (grant no. CZY18022).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank PTM Biolabs Co., Ltd. (Hangzhou, China) for the mass spectrometry analysis.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2020.00394/full#supplementary-material

FIGURE S1Analysis of the protein domains of GmcA in Rhizobium leguminosarum 3841. BetA, choline dehydrogenase or related flavoprotein; GMC_oxred_C, GMC oxidoreductase; GMC_mycofac_2, GMC family mycofactocin-associated oxidoreductase.

FIGURE S2Plant growth test of the symbiotic ability of R. leguminosarum. (A) Control plant root inoculated with the wild type RL3841, (B) Plant root inoculated with RLgmcA.

References

1

AhmadB.HaqS. K.VarshneyA.Moosavi-MovahediA. A.KhanR. H. (2010). Effect of trifluoroethanol on native and acid-induced states of glucose oxidase from Aspergillus niger.Biochemistry75486–493. 10.1134/S0006297910040139

2

AllawayB.LodwigE.CromptonL. A.WoodM.ParsonsR.WheelerT. R.et al (2000). Identification of alanine dehydrogenase and its role in mixed secretion of ammonium and alanine by pea bacteroids.Mol. Microbiol.36508–515. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01884.x

3

BaginskyC.BritoB.ImperialJ.PalaciosJ. M.Ruiz-ArguesoT. (2002). Diversity and evolution of hydrogenase systems in rhizobia.Appl. Environ. Microbiol.684915–4924. 10.1128/AEM.68.10.4915-4924.2002

4

BarrM.EastA. K.LeonardM.MauchlineT. H.PooleP. S. (2008). in vivo expression technology (IVET) selection of genes of Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar viciae A34 expressed in the rhizosphere.FEMS Microbiol. Lett.282219–227. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01131.x

5

BeckettR. P.NtombelaN.ScottE.GurjanovO. P.MinibayevaF. V.LiersC. (2015). LiersRole of laccases and peroxidases in saprotrophic activities in the lichen Usnea undulata.Fungal Ecol.1471–78. 10.1016/j.funeco.2014.12.004

6

BeringerJ. E.HopwoodD. A. (1976). Chromosomal recombination and mapping in Rhizobium leguminosarum.Nature264291–293. 10.1038/264291a0

7

BhatS. V.BoothS. C.McGrathS. G. K.DahmsT. E. S. (2015). Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae 3841 Adapts to 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid with “Auxin-Like” morphological changes, cell envelope remodeling and upregulation of central metabolic pathways.PLoS ONE10:e0123813. 10.1371/journal.pone.0123813

8

BisognoF.Rioz-MartínezA.RodríguezC.LavanderaI.De GonzaloG.Torres PazminoD.et al (2010). Oxidoreductases working together: concurrent obtaining of valuable derivatives by employing the PIKAT method.Chemcatchem2946–949. 10.1002/cctc.201000115

9

BlancoF. A.MeschiniE. P.ZanettiM. E.AguilarO. M. (2009). A small gtpase of the rab family is required for root hair formation and preinfection stages of the common bean–rhizobium symbiotic association.Plant Cell212797–2810. 10.2307/40537042

10

CapelaD.FilipeC.BobikC.BatutJ.BruandC. (2006). Sinorhizobium meliloti differentiation during symbiosis with alfalfa: a transcriptomic dissection.Mol. Plant Microbe Interact.19363–372. 10.1094/MPMI-19-0363

11

CavenerD. R. (1992). Gmc oxidoreductases. A newly defined family of homologous proteins with diverse catalytic activities.J. Mol. Biol.223811–814. 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90992-S

12

ChaoT. C.BuhrmesterJ.HansmeierN.PuhlerA.WeidnerS. (2005). Role of the regulatory gene rirA in the transcriptional response of Sinorhizobium meliloti to iron limitation.Appl. Environ. Microb.715969–5982. 10.1128/AEM.71.10.5969-5982.2005

13

ChengG.KarunakaranR.EastA. K.MunozazcarateO.PooleP. S. (2017). Glutathione affects the transport activity of Rhizobium leguminosarum 3841 and is essential for efficient nodulation.FEMS Microbiol. Lett.364:fnx045. 10.1093/femsle/fnx045

14

ClarkeT. A.FairhurstS.LoweD. J.WatmoughN. J.EadyR. R. (2011). Electron transfer and half-reactivity in nitrogenase.Biochem. Soc. Trans.39:201. 10.1042/BST0390201

15

CoxJ.MannM. (2008). MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification.Nat. Biotechnol.261367–1372. 10.1038/nbt.1511

16

EtxebesteO.Herrero-GarcíaE.CorteseM. S.GarziaA.Oiartzabal-AranoE.de los RíosV.et al (2012). GmcA is a putative glucose-methanol-choline oxidoreductase required for the induction of asexualdevelopment in Aspergillus nidulans.PLoS ONE7:e40292. 10.1371/journal.pone.0040292

17

FerreiraP.CarroJ.SerranoA.MartínezA. T. (2015). A survey of genes encoding H2O2-producing gmc oxidoreductases in 10 polyporales genomes.Mycologia1071105–1119. 10.3852/15-027

18

FigurskiD. H.HelinskiD. R. (1979). Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.761648–1652. 10.1073/pnas.76.4.1648

19

GiergielM.LopuckiM.StachowiczN.KankoferM. (2012). The influence of age and gender on antioxidant enzyme activities in humans and laboratory animals.Aging Clin. Exp. Res.24561–569. 10.3275/8587

20

GossT.TwachtmannM.MulkidjanianA.SteinhoffH. J.KlareJ. P.HankeG. T.et al (2012). Impact of ferredoxin:nadp(h) oxidoreductase on redox poise of the glutathione pool and fenton reaction capacity of thylakoid membranes: a connection to pre-acquired acclimation in arabidopsis.Free Radical Biol. Med.53:S42. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.08.509

21

GuS. Y.YanX. X.LiangD. C. (2008). Crystal structure of tflp: a ferredoxin-like metallo-β-lactamase superfamily protein from Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis.Proteins72531–536. 10.1002/prot.22069

22

HaneyC. H.LongS. R. (2010). Plant flotillins are required for infection by nitrogen-fixing bacteria.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.107478–483. 10.2307/40536299

23

HollmannF.SchmidA. (2004). Electrochemical regeneration of oxidoreductases for cell-free biocatalytic redox reactions.Biocatalysis2263–88. 10.1080/10242420410001692778

24

IidaK.Cox-FosterD. L.YangX.KoW. Y.CavenerD. R. (2007). Expansion and evolution of insect gmc oxidoreductases.BMC Evol. Biol.7:75. 10.1186/1471-2148-7-75

25

IslamT.MannaM.ReddyM. K. (2015). Glutathione peroxidase of Pennisetum glaucum (PgGPx)is a functional Cd2+ dependent peroxiredoxin that enhances tolerance against salinity and drought stress.PLoS ONE10:e0143344. 10.1371/journal.pone.0143344

26

JanczarekM.RachwałK.MarzecA.GrządzielJ.Palusińska-SzyszM. (2015). Signal molecules and cell-surface components involved in early stages of the legume-rhizobium interactions.Appl. Soil Ecol.8594–113. 10.1016/j.apsoil.2014.08.010

27

JeelaniG.HusainA.SatoD.AliV.SuematsuM.SogaT.et al (2010). Two atypical L-cysteine-regulated nadph-dependent oxidoreductases involved in redox maintenance, L-cystine and iron reduction, and metronidazole activation in the enteric protozoan Entamoeba histolytica.J. Biol. Chem.28526889–26899. 10.1074/jbc.M110.106310

28

JohnstonA. W.BeringerJ. E. (1975). Identification of the rhizobium strains in pea root nodules using genetic markers.J. Gen. Microbiol.87343–350. 10.1099/00221287-87-2-343

29

JungI. L.KimI. G. (2003). Transcription of ahpC, katG, and katE genes in Escherichia coli is regulated by polyamines: polyamine-deficient mutant sensitive to H2O2-induced oxidative damage.Biochem. Bioph. Res. Co.301915–922. 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00064-0

30

KarunakaranR.EberT. K.HarveyS.LeonardM. E.RamachandranV.PooleP. S. (2006). Thiamine is synthesized by a salvage pathway in Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae strain 3841.J. Bacteriol.1886661–6668. 10.1128/jb.00641-06

31

KarunakaranR.HaagA. F.EastA. K.RamachandranV. K.PrellJ.JamesE. K.et al (2010). BacA is essential for bacteroid development in nodules of galegoid, but not phaseoloid, legumes.J. Bacteriol.1922920–2928. 10.1128/JB.00020-10

32

KarunakaranR.RamachandranV. K.SeamanJ. C.EastA. K.MouhsineB.MauchlineT. H.et al (2009). Transcriptomic analysis of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae in symbiosis with host plants Pisum sativum and Vicia cracca.J. Bacteriol.1914002–4014. 10.1128/JB.00165-09

33

LiuX.OhtaT.KawabataT.KawaiF. (2013). Catalytic mechanism of short ethoxy chain nonylphenol dehydrogenase belonging to a polyethylene glycol dehydrogenase group in the gmc oxidoreductase family.Int. J. Mol. Sci.141218–1231. 10.3390/ijms14011218

34

López-BaenaF. J.Ruiz-SainzJ. E.Rodríguez-CarvajalM. A.VinardellJ. M. (2016). Bacterial molecular signals in the Sinorhizobium fredii-soybean symbiosis.Int. J. Mol. Sci.17:755. 10.3390/ijms17050755

35

OkazakiS.TittabutrP.TeuletA.ThouinJ.GiraudE. (2015). Rhizobium-legume symbiosis in the absence of nod factors: two possible scenarios with or without the T3SS.ISME J.10193–203. 10.1038/ismej.2015.103

36

PfafflM. W.HorganG. W.DempfleL. (2002). Relative expression software tool (REST(c)) for group-wise comparison and statistical analysis of relative expression results in real-time PCR.Nucleic Acids Res.30:E36. 10.1093/nar/30.9.e36

37

PooleP. S.BlythA.ReidC.WaltersK. (1994). myo-Inositol catabolism and catabolite regulation in Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae.Microbiology1402787–2795. 10.1099/00221287-140-10-2787

38

PrellJ.BourdèsA.KarunakaranR.Lopez-GomezM.PooleP. S. (2009). Pathway of {gamma}-aminobutyrate (GABA) metabolism in Rhizobium leguminosarum 3841 and its role in symbiosis.J. Bacteriol.1912177–2186. 10.1128/JB.01714-08

39

RahfeldP.KirschR.KugelS.WielschN.StockM.GrothM.et al (2014). Independently recruited oxidases from the glucose-methanol-choline oxidoreductase family enabled chemical defences in leaf beetle larvae (subtribe Chrysomelina) to evolve.Proc. R. Soc. B28120140842. 10.1098/rspb.2014.0842

40

RohrC. O.LevinL. N.MentaberryA. N.WirthS. A.MonikaS. (2013). A first insight into Pycnoporus sanguineus BAFC 2126 transcriptome.PLoS ONE8:e81033. 10.1371/journal.pone.0081033

41

SeefeldtL. C.YangZ. Y.DuvalS.DeanD. R. (2013). Nitrogenase reduction of carbon-containing compounds.Biochim. Biophys. Acta18271102–1111. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2013.04.003

42

SmithP. K.KrohnR. I.HermansonG. T. (1985). Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid.Anal. Biochem.16376–85. 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90442-7

43

SützlL.LaurentC. V. F. P.AbreraA. T.SchützG.LudwigR.HaltrichD. (2018). Multiplicity of enzymatic functions in the CAZy AA3 family.Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol.1022477–2492. 10.1007/s00253-018-8784-0

44

TakanashiK.YokoshoK.SaekiK.SugiyamaA.SatoS.TabataS.et al (2013). LjMATE1: a citrate transporter responsible for iron supply to the nodule infection zone of Lotus japonicus.Plant Cell Physiol.54585–594. 10.1093/pcp/pct118

45

TalS.SmirnoffP.OkonY. (1990). Purification and characterization of D-(2)-b-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase from Azospirillum brasilense Cd.J. Gen. Microbiol.136645–649. 10.1099/00221287-136-4-645

46

Vargas MdelC.EncarnacionS.DavalosA.Reyes-PerezA.MoraY.Garcia-de los SantosA.et al (2003). Only one catalase, katG, is detectable in Rhizobium etli, and is encoded along with the regulator OxyR on a plasmid replicon.Microbiology1491165–1176. 10.1099/mic.0.25909-0

47

VincillE. D.SzczyglowskiK.RobertsD. M. (2005). GmN70 and LjN70. Anion transporters of the symbiosome membrane of nodules with a transport preference for nitrate.Plant Physiol.1371435–1444. 10.1104/pp.104.051953

48

XieF.ChengG.XuH.WangZ.LeiL.LiY. (2011). Identification of a novel gene for biosynthesis of a bacteroid-specific electron carrier menaquinone.PLoS ONE6:e28995. 10.1371/journal.pone.0028995

49

YanH.XiaoG.ZhangJ.HuY.YuanF.ColeD. K.et al (2004). SARS coronavirus induces apoptosis in Vero E6 cells.J. Med. Virol.73323–331. 10.1002/jmv.20094

50

YilmazJ. L.BülowL. (2010). Enhanced stress tolerance in Escherichia coli and Nicotiana tabacum expressing a betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase/choline dehydrogenase fusion protein.Biotechnol. Progr.181176–1182. 10.1021/bp020057k

51

YoungJ. P.CrossmanL.JohnstonA.ThomsonN.GhazouiZ.HullK.et al (2006). The genome of Rhizobium leguminosarum has recognizable core and accessory components.Genome Biol.7:R34.

Summary

Keywords

Rhizobium leguminosarum, the glucose-methanol-choline oxidoreductase GmcA, symbiotic nitrogen fixation, antioxidant and symbiotic gene expression, quantitative proteomics

Citation

Zou Q, Luo S, Wu H, He D, Li X and Cheng G (2020) A GMC Oxidoreductase GmcA Is Required for Symbiotic Nitrogen Fixation in Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae. Front. Microbiol. 11:394. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00394

Received

18 November 2019

Accepted

26 February 2020

Published

24 March 2020

Volume

11 - 2020

Edited by

Nikolay Vassilev, University of Granada, Spain

Reviewed by

Jose María Vinardell, University of Seville, Spain; Clarisse Brígido, University of Évora, Portugal

Updates

Copyright

© 2020 Zou, Luo, Wu, He, Li and Cheng.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Guojun Cheng, chengguojun@mail.scuec.edu.cn

This article was submitted to Plant Microbe Interactions, a section of the journal Frontiers in Microbiology

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.