Abstract

The complex transmission profiles of vector-borne zoonoses (VZB) and vector-borne infections with animal reservoirs (VBIAR) complicate efforts to break the transmission circuit of these infections. To control and eliminate VZB and VBIAR, insecticide application may not be conducted easily in all circumstances, particularly for infections with sylvatic transmission cycle. As a result, alternative approaches have been considered in the vector management against these infections. In this review, we highlighted differences among the environmental, chemical, and biological control approaches in vector management, from the perspectives of VZB and VBIAR. Concerns and knowledge gaps pertaining to the available control approaches were discussed to better understand the prospects of integrating these vector control approaches to synergistically break the transmission of VZB and VBIAR in humans, in line with the integrated vector management (IVM) developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) since 2004.

Introduction

Zoonoses are infections transmitted from animals to humans (Murphy, 1998). In fact, “zoonosis” is a relatively new word coined by German scientist Rudolf Virchow in the late 19th century, which combines Greek words “zoon” (animal) and “noson” (disease) (Chomel, 2009). Due to increased overlap of habitats by humans and wildlife, climate change, certain economic, cultural and dietary practices, as well as invasion of alien species and convenient international travels, the healthcare and economic burden exerted by zoonoses has increased significantly (Woolhouse and Gowtage-Sequeria, 2005; Jones et al., 2008; Grace et al., 2012; Karesh et al., 2012; Kulkarni et al., 2015). Zoonoses are caused by a variety of pathogens encompassing viruses, bacteria, parasites, fungi, and prions (Taylor et al., 2001; Woolhouse and Gowtage-Sequeria, 2005; Jones et al., 2008). Theoretically, the transmission of a zoonosis can be prevented by segregating humans and the animals that serve as natural hosts of the pathogen (Chomel, 2009; Karesh et al., 2012). However, control and prevention strategies may face additional challenges when the zoonosis is vector-borne, as reflected by knowlesi malaria, a potentially fatal zoonosis transmitted by simio-anthropophilic anopheline mosquitoes (Tan et al., 2008; Jiram et al., 2012; Vythilingam et al., 2014; Wong et al., 2015; Lau et al., 2016). Similar obstacles happen with vector-borne infections possessing animal reservoirs, such as the tsetse fly-transmitted Trypanosoma brucei, the sand fly-transmitted leishmaniasis, and the mosquito-borne Sindbis virus (SINV), Zika virus (ZIKV), and yellow fever virus (Balfour, 1914; Njiokou et al., 2006; Singh et al., 2013; Vorou, 2016; Steyn et al., 2020; Kushwaha et al., 2022). Since the involving animals cannot be culled just to break the transmission circuit to humans (Lee et al., 2022), vector control is a critical component of breaking the transmission of vector-borne zoonoses (VBZ) and vector-borne infections with animal reservoirs (VBIAR). Vector control programs aim at either reducing the population of the vectors, or avoiding, if not reducing the exposure of the targeted vectors to humans (Wilson et al., 2020). Notably, a wide variety of arthropods and arachnids with different biological behaviors have been verified as medically important disease vectors (Table 1). The diverse array of vectors, animal reservoirs, and activities engaged by humans in the vicinity contribute different challenges to the control and elimination of these diseases. Here, we discussed the main vector control strategies in the current scenario, highlighted the strengths, limitations, and concerns arising from these approaches, knowledge gaps that deserve to be filled, and possibility of integrating multiple approaches of vector management into the control and elimination of VBZ and VBIAR.

Table 1

| VBDs | Causative agent | Vector | Animal reservoir | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malaria | Human: Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium malariae, Plasmodium ovale spp. | Mosquito: Anopheles spp. | N/A | Warren and Wharton (1963), Vythilingam et al. (2001, 2005, 2006), da Rocha et al. (2008), Tan et al. (2008), Sinka et al. (2010), Sinka et al. (2011), Jiram et al. (2012), Sinka et al. (2012), Vythilingam (2012), Vythilingam and Hii (2013), Vythilingam et al. (2013), Vythilingam et al. (2014), Wong et al. (2015), Lau et al. (2016), Liew et al. (2021), and Vythilingam et al. (2021) |

| Zoonotic: Plasmodium knowlesi, Plasmodium cynomolgi, Plasmodium inui, Plasmodium simium, Plasmodium brasilianum | Mosquito: Leucosphyrus group of mosquitoes | Simian primates | ||

| Babesiosis | Babesia microti, Babesia divergens, Babesia duncani, Babesia venatorum | Tick: Ixodes spp. | Cattle, roe deer and rodents | Donnelly and Peirce (1975), Spielman (1976), Lewis and Young (1980), Walter and Weber (1981), Mylonakis (2001), Gray et al. (2002), and Bonnet et al. (2009) |

| Dengue | Dengue virus (DENV) | Mosquito: Aedes aegypti, Ae. albopictus, Ae. polynesiensis, Ae. scutellaris group | Monkey (sylvatic dengue strains) | Siler et al. (1926), Chan et al. (1971), Rosen and Gubler (1974), Gubler (1988), Moore and Mitchell (1997), Rigau-Perez and Gubler (1997), Scott et al. (1997), Hotta (1998), Tsuda et al. (2002), Gubler et al. (2007), Lambrechts et al. (2010), and Higa (2011) |

| Yellow fever | Yellow Fever virus (YFV) | Mosquito: Aedes spp., Haemagogus spp. | Monkeys | Haddow (1969), Barrett and Higgs (2007), and Young et al. (2014) |

| Chikungunya | Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) | Mosquito: Ae. aegypti, Ae. albopictus | Primates | Niyas et al. (2010) and Kumar et al. (2012) |

| O’nyong’nyong fever | O’nyong’nyong virus (ONNV) | Mosquito: Anopheles spp. | N/A | Shore (1961), Johnson (1988), and Young et al. (2014) |

| Sindbis fever | Sindbis virus (SINV) | Mosquito: Culex spp., Culiseta spp. | Birds | Laine et al. (2004), Young et al. (2014), and Sang et al. (2017) |

| Zika | Zika virus (ZIKV) | Mosquito: Aedes spp. | Primates | Dick (1952), Marchette et al. (1969), and Vorou (2016) |

| Rift Valley fever | Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV) | Mosquito: Aedes spp., Culex spp. | Ruminants | Davies (1975), Davies and Highton (1980), Chevalier et al. (2004), and Sang et al. (2017) |

| West Nile fever | West Nile virus (WNV) | Mosquito: Culex spp. | Birds | Taylor and Hurlbut (1953) and Shirato et al. (2005) |

| Japanese encephalitis | Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) | Mosquito: Culex spp., Ae. togoi, Ae. japonicus, Ae. vexans nipponii, An. annularis, An. vagus | Birds, pigs (amplifier host) | Sucharit et al. (1989), Vythilingam et al. (1994), Vythilingam et al. (1995), Vythilingam et al. (1997), Weng et al. (1999), Das et al. (2005), Nitatpattana et al. (2005), van den Hurk et al. (2006), Seo et al. (2013), and de Wispelaere et al. (2017) |

| Murray Valley encephalitis | Murray Valley encephalitis virus (MVEV) | Mosquito: Culex annulirostris | Birds | Marshall (1988), Mackenzie et al. (1994), Kurucz et al. (2005), and Floridis et al. (2018) |

| Tick-borne encephalitis | Tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) | Tick: Ixodes spp., Dermacentor spp. | Small mammals | Kozuch and Nosek (1971), Labuda and Randolph (1999), and Biernat et al. (2014) |

| Kunjin encephalitis | Kunjin virus (KUNV) | Mosquito: Culex annulirostris | Birds | Doherty et al. (1963), Kay et al. (1984), Marshall (1988), Hall et al. (2002), and Hall et al. (2006) |

| Colorado tick fever | Colorado tick fever virus (CTFV) | Tick: Dermacentor andersoni | Squirrels, chipmunks, mice | Florio et al. (1944), Florio and Miller (1948), Florio et al. (1950), and Emmons (1988) |

| Lymphatic filariasis | Human: Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi, Brugia timori | Mosquito: Anopheles spp., Culex spp., Aedes spp., Mansonia spp. | Cats, dogs, monkeys, pangolins (B. malayi) | Edeson and Wilson (1964), Cheong et al. (1981), Chiang et al. (1984), Hii et al. (1984), Zahedi and White (1994), Kanjanopas et al. (2001), Vythilingam (2012), Muslim et al. (2013), Vythilingam et al. (2013), WHO (2013), Aagaard et al. (2015), Mulyaningsih et al. (2019), and Nunthanid et al. (2020) |

| Zoonotic: Brugia pahangi | Mosquito: Armigeres subalbatus | Cats and dogs | ||

| Serous cavity filariasis | Mansonella perstans, Mansonella ozzardi | Midge: Culicoides spp. | N/A | Manson (1891) |

| Subcutaneous filariasis | Loiasis: Loa loa | Deer fly: Chrysops spp. | N/A | Kleine (1915), Connal (1921), Macfie and Corson (1922), Fischer et al. (1997), Lawrence (2004), Boussinesq (2006), Kelly-Hope et al. (2017), and Hendy et al. (2018) |

| Mansonella streptocerca | Midge: Culicoides spp. | N/A | ||

| Onchocerciasis / river blindness: Onchocerca volvulus | Black fly: Simulium spp. | N/A | ||

| Sleeping sickness (African trypanosomiasis) | Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense, Trypanosoma brucei gambiense | Tsetse fly: Glossina spp. | Cattle (T. brucei rhodesiense) Primates & ungulates (T. brucei gambiense)# | Bruce (1895, 1915) and Njiokou et al. (2006) |

| Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis) | Trypanosoma cruzi | True bug/kissing bug/triatomine/reduviid bug: Rhodnius prolixus, Triatoma infestans | Small rodents | Chagas (1909), Jurberg and Galvão (2006), Rassi et al. (2010), and WHO (2015) |

| Leishmaniasis | Leishmania | Phlebotomine sandfly: Phlebotomus spp., Lutzomyia spp. | Dogs | Swaminath et al. (1942), Mukhopadhyay et al. (2000), and Guerbouj et al. (2007) |

| Epidemic typhus (louse-borne typhus) | Rickettsia prowazekii | Human body louse: Pediculus humanus humanus | Flying squirrels (sylvatic typhus) | McDade et al. (1980), McDade and Newhouse (1986), and Durden (2019) |

| Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) | Rickettsia rickettsii | Tick: Dermacentor variabilis, Dermacentor andersoni, Rhipicephalus sanguine | Small mammals | Kohls (1947) and Ahantarig et al. (2013) |

| Queensland tick typhus (QTT) | Rickettsia australis | Tick: Ixodes holocyclus, I. tasmania | Bandicoots, rodents | Fenner (1946), Domrow and Derrick (1964), Sexton et al. (1991), and Barker and Walker (2014) |

| Scrub typhus | Orientia tsutsugamushi | Mite: Leptotrombidium spp. | Rodents | Shirai et al. (1981), Pham et al. (2001), Lerdthusnee et al. (2003), and Weitzel et al. (2022) |

| Tularemia (rabbit fever) | Francisella tularensis | Tick: Amblyomma spp., Dermacentor spp., Haemaphysalis spp., Ixodes spp. | Rabbits, hares, other small rodents | Parker et al. (1924), Gurycová (1998), Sjöstedt (2007), Kugeler et al. (2009), Männikkö (2011), Maurin et al. (2011), Yeni et al. (2021), and Troha et al. (2022) |

| Deer fly: Chrysops discalis | Deers | |||

| Lyme disease | Borrelia burgdorferi, Borrelia mayonii | Tick: Ixodes spp. | Avians, mammals | Wilson et al. (1985), Steere (2001), Lo Re et al. (2004), and Couper et al. (2020) |

| Bubonic plague | Yersinia pestis | Oriental rat flea: Xenopsylla cheopis | Rodents | Bacot and Martin (1914), Bacot (1915), Burroughs (1947), and Pollitzer (1954) |

| Anaplasmosis | Anaplasma phagocytophilum | Tick: Ixodes spp. | Mammals, birds | Chen et al. (1994), Ohashi et al. (2005), Katargina et al. (2012), and Bakken and Dumler (2015) |

| Ehrlichiosis | Ehrlichia chaffeensis, Ehrlichia ewingii, Erhlichia muris eauclairensis | Ticks: Amblyomma spp., Ixodes spp. | Mammals | Anderson et al. (1993), Lockhart et al. (1997), and Ganguly and Mukhopadhayay (2008) |

Vector-borne diseases (VBDs) and the respective vectors and animal reservoirs.

Humans are the main reservoir for T. brucei gambiense but this parasite has been isolated from primates and ungulates.

The trilogy of vector control strategies

In general, vector control strategies can be classified into chemical, biological and environmental management approaches (Bos, 1991). Each of these approaches gained research and public attention at different time points and comes with its own advantages and disadvantages. These approaches are inter-related, where simultaneous application of multiple approaches can produce either synergistic effect against the propagation of vectors, or antagonistic effect that disputes the vector control program. Therefore, a thorough understanding on each vector control approach is crucial for a successful vector control that can lead to the eradication of respective vector-borne diseases (WHO, 2012). This is particularly crucial for the management of VBZ and VBIAR, as the transmission profiles of these infections are usually more complex, involving more organisms. In fact, some of these diseases have multiple transmission cycles. For example, Trypanosoma cruzi has an urban transmission cycle involving humans, and sylvatic cycle involving wildlife (Orozco et al., 2013), whereas yellow fever virus has sylvatic, intermediate/savannah and urban transmission cycles (Valentine et al., 2019; Cunha et al., 2020; Gabiane et al., 2022). Of note, each transmission cycle may involve different vectors with distinct biological properties and behaviors that further complicate transmission blocking via vector control program. Worse still, many of these infections have incompletely deciphered transmission risk factors (Swei et al., 2020). Due to such complexity, a well-designed multi-pronged strategy that integrates multiple approaches may be more suitable to control the transmission of VBZ and VBIAR.

Environment management approach

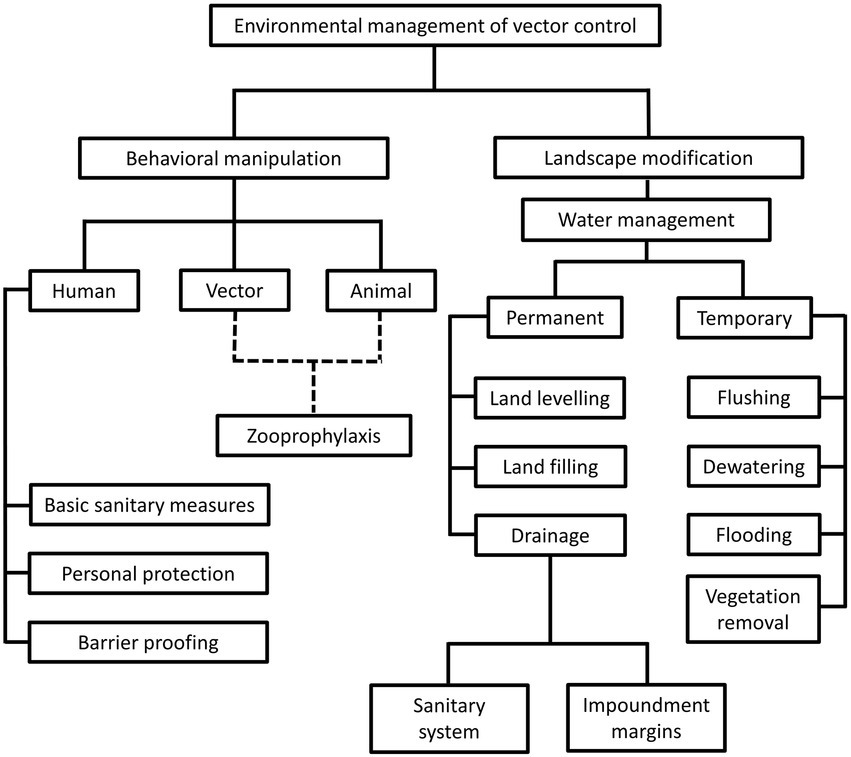

The environment management approach was the predominant vector control method prior to World War II (WWII). During this period, comprehensive understanding on local vector behavior and ecology dynamics, along with specifically tailored environmental management plans were the prerequisites toward a successful vector control (Quiroz-Martinez and Rodriguez-Castro, 2007; Wilson et al., 2020). The environment approach revolves around behavioral manipulation and landscape modification (Figure 1). Behavioral manipulation can be directed at humans, animals or the vectors involved (Ault, 1994). For example, community members can be trained to practice good sanitary measures around their housing compound, set up barrier proofing against mosquitoes (such as usage of bed net and mosquito screens), and employs personal protection when exploring places with high vector density (Demers et al., 2018; Wilson et al., 2020). Zooprophylaxis can be employed to distract vectors from biting humans (or animals that serve as natural reservoirs of the targeted pathogen), by introducing another animal with similar or better feeding attractiveness to the targeted vectors (Charlwood et al., 1985; Sousa et al., 2001). In this context, the mosquito behavior is manipulated. On the other hand, landscape modification revolves around temporary and permanent strategies of water management, with the goal of removing suitable breeding grounds for the vectors (Watsons, 1921). Vector control via environment management has been employed against the transmission of malaria (Le Prince and Orenstein, 1916; Watsons, 1921; Utzinger et al., 2001; Lindsay et al., 2002; Ferroni et al., 2012), lymphatic filariasis (van den Berg et al., 2013; Davis et al., 2021), yellow fever (Le Prince and Orenstein, 1916; Soper and Wilson, 1943), African trypanosomiasis (Jackson, 1941; Jackson, 1943; Jackson, 1948; Scott, 1966; Hargrove, 2003; Headrick, 2014), and leishmaniasis (Busvine, 1993; Steverding, 2017) in different parts of the world. However, this approach does not work in a “one size fits all” manner. For example, the zooprophylaxis approach reported promising results in Papua New Guinea and São Tomé (Charlwood et al., 1985; Sousa et al., 2001). However, this approach experienced failure in places such as Ethiopia, the Gambia, and Pakistan (Bouma and Rowland, 1995; Ghebreyesus et al., 2000; Bøgh et al., 2001). Such contradicting outcomes were due to various factors, including the types of vectors targeted in these studies. Indeed, the success of zooprophylaxis relies on the prerequisites that the involving vectors must be zoophilic and exophilic (outdoor feeders), in addition to the adequate segregation between the human and animal living spaces (Asale et al., 2017).

Figure 1

Different strategies under the environmental management of vector control. This approach revolves around behavioral alteration of humans, animals and vectors, as well as landscape modification, to create barriers between humans and vectors. Of note, the “zooprophylaxis” under “behavioral manipulation” involves the introduction of animals that are not pathogen reservoirs, to distract the blood-seeking vectors from humans and animals that serve as natural reservoirs of pathogens. This method involves behavioral alteration of animals and vectors, as indicated by the dotted lines in the diagram. On the other hand, landscape modification consists of permanent and temporary water management strategies to change the breeding environment of vectors.

A thorough evaluation and understanding on the stakeholders and targeted areas, along with long-term engagement (commitment) by the government and community members are needed to ensure a higher success rate of vector control via environment management. However, these can only be achieved with adequate time, financial support, and sustainable manpower. In addition, the benefits brought by this approach may be shadowed by unpredictable and potentially irreversible negative impact cast upon the environment, as exemplified by the bush clearing effort in parts of Africa during the 1950s and 1960s to control the population of tsetse flies (Scott, 1966; Hargrove, 2003; Pilossof, 2016). Hence, this vector control approach may not be an ideal solution for all diseases. Nevertheless, this approach is still a valuable tool for a sustained elimination of the targeted vector-borne diseases, provided that the approach is designed carefully by taking all biological, environmental, legal and socio-economic factors into consideration.

Chemical vector control

Chemical vector control strategies have gained popularity, especially after the WWII, due to the rapid and potent effect of these methods. The development, marketing and application of various insecticides has been the mainstream of chemical vector control strategy. Attempts to employ chemicals for pest control were recorded as early as the 1840s (Table 2). However, the discovery of dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane (DDT) revolutionized the approach to control vector population. The insecticidal properties of DDT were discovered in 1939 (Mellanby, 1992; Davies et al., 2007). Following the halted supply of chrysanthemum-derived pyrethrum from Japan due to WWII, DDT became the mainstream chemical player in vector control (Wilson et al., 2020), especially after its involvement in the successful control of typhus outbreak in Europe (Wheeler, 1946). Following this much publicized success against lice, DDT was proven to be potent against many other vectors such as the mosquito, tsetse fly, sandfly and blackfly (Ismail et al., 1975; Loyola et al., 1990, 1991; Roberts and Alecrim, 1991; Casas et al., 1998; Hargrove, 2003; Dias, 2007; Rijal et al., 2019). Nevertheless, the negative impacts brought by DDT to non-targeted organisms and environment were discovered after years of mass application. As a result, the application of this powerful chemical was discontinued abruptly in the 1970s (Davies et al., 2007). Subsequently, other insecticide groups such as organophosphates, carbamates and synthetic pyrethroid gained popularity in many vector control programs. This has stimulated various chemical-oriented vector combating strategies, such as the long-lasting insecticidal net (LLIN), indoor residual spraying (IRS), as well as outdoor residual spraying (ORS; Bonsall and Goose, 1986; Bhatt et al., 2015; Rohani et al., 2020; Tangena et al., 2020; Chaumeau et al., 2022).

Table 2

| Year | Description | Methods | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1840 | Discovery of insecticidal properties of a Tanacetum (Chrysanthemum) cinerariifolium (Compositae)-derived compound (pyrethrum), subsequently its successful extraction and commercial production | N/A | Ujváry (2010) |

| 1930s | Discovery of insecticidal properties of organophosphates (OP) and carbamate. | N/A | Hill (1995) and Glaser (1999) |

| 1939 | Discovery of insecticidal properties of dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) against flies, mosquitoes and beetles by Paul Muller | N/A | Mellanby (1992) and Davies et al. (2007) |

| 1943 | First application of DDT in Italy to control typhus epidemic | Dusting 10% DDT powder onto clothing of infested individuals to kill body lice | Wheeler (1946) |

| 1946–1991 | Widespread application of DDT and other organochlorines (OC) in various locations to control vector-borne diseases | Aerial spraying and indoor residual spraying (IRS) | Ismail et al. (1975), Loyola et al. (1990), Loyola et al. (1991), Roberts and Alecrim (1991), Casas et al. (1998), and Hargrove (2003) |

| 1949 | Development of the first synthethic pyrethroids | N/A | Davies et al. (2007) and Matsuo (2019) |

| 1955–1969 | Introduction and implementation of Global Malaria Eradication Program by WHO | Control program varied across different locations | Najera et al. (2011) |

| 1972 | DDT usage was banned by US Environment Agency | N/A | Mellanby (1992) and Davies et al. (2007) |

| 1970s – present | Development of pyrethroid-treated net (ITN) for malaria control. Organophosphates and carbamates are more widely used as replacements for OC due to hazardous effect imposed by DDT | Organophosphates: residual spraying, space spraying and larviciding. Carbamates: residual spraying | Bonsall and Goose (1986), Dorta et al. (1993), van den Berg et al. (2012), Tangena et al. (2020), and van den Berg et al. (2021a,b) |

Brief overview of insecticides in vector control.

Various chemicals have been developed and marketed as readily available larvicides and adulticides. The high availability and instantaneous killing effect of these products have created a dogma that the chemicals are the best way forward in vector management (Casida and Quistad, 1998; Thomas, 2018). Nevertheless, the biology of arthropods plays a critical role in determining the success rate of insecticide-mediated vector control programs. For instance, IRS and LLIN are not suitable for exophagic and exophilic mosquitoes with peak biting time in the early evening (Dolan et al., 1993; Rohani et al., 1999; Smithuis et al., 2013; Wong et al., 2015). Besides, behavioral adaptation of endophilic mosquitoes toward avoidance of insecticide-treated houses or rapid exit from the insecticide-treated buildings will minimize the exposure of these vectors to the insecticides, compromising the efficacy of the applied insecticide (Killeen, 2014). Importantly, the rampant usage of these chemicals has fuelled insecticide resistance in arthropods (Kleinschmidt et al., 2018; Tangena et al., 2020). Moreover, these chemicals may cast negative impacts to the ecosystem, although of lower toxicity than DDT. For example, synthetic pyrethroids are harmful to aquatic environment (Thatheyus and Selvam, 2013; Prusty et al., 2015), whereas organophosphates poisoning remains prevalent among communities involved in agricultural industry, despite being classified as non-persistent pesticides (Jaipieam et al., 2009; Kaushal et al., 2021). Due to these disadvantages, the chemical approach must be considered carefully in vector control programs against VBZ and VBIAR, particularly those with sylvatic transmission cycle.

Despite the non-specific harm to the environment due to their toxicity, the rapid and potent effect of insecticides against different vectors grants them the high popularity in pest and vector control. Many researchers have investigated ways of accelerating the degradation of these chemicals to minimize their adverse effects to the environment, while retaining their potency against the pests (Zhang and Qiao, 2002; Kaushal et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2022). Meanwhile, the discovery of pyrethrum from chrysanthemum plant continues to inspire scientists to find novel compounds that can serve as bio-insecticides. For example, bioactive metabolites of Streptomyces have been reported to demonstrate good potential of becoming bio-insecticide candidates (Amelia-Yap et al., 2022). Such discovery has been driven by the need of novel, environment-friendly insecticide compounds, following rapid development of insecticide resistance and concerns over environment harm cast by chemical-based insecticides.

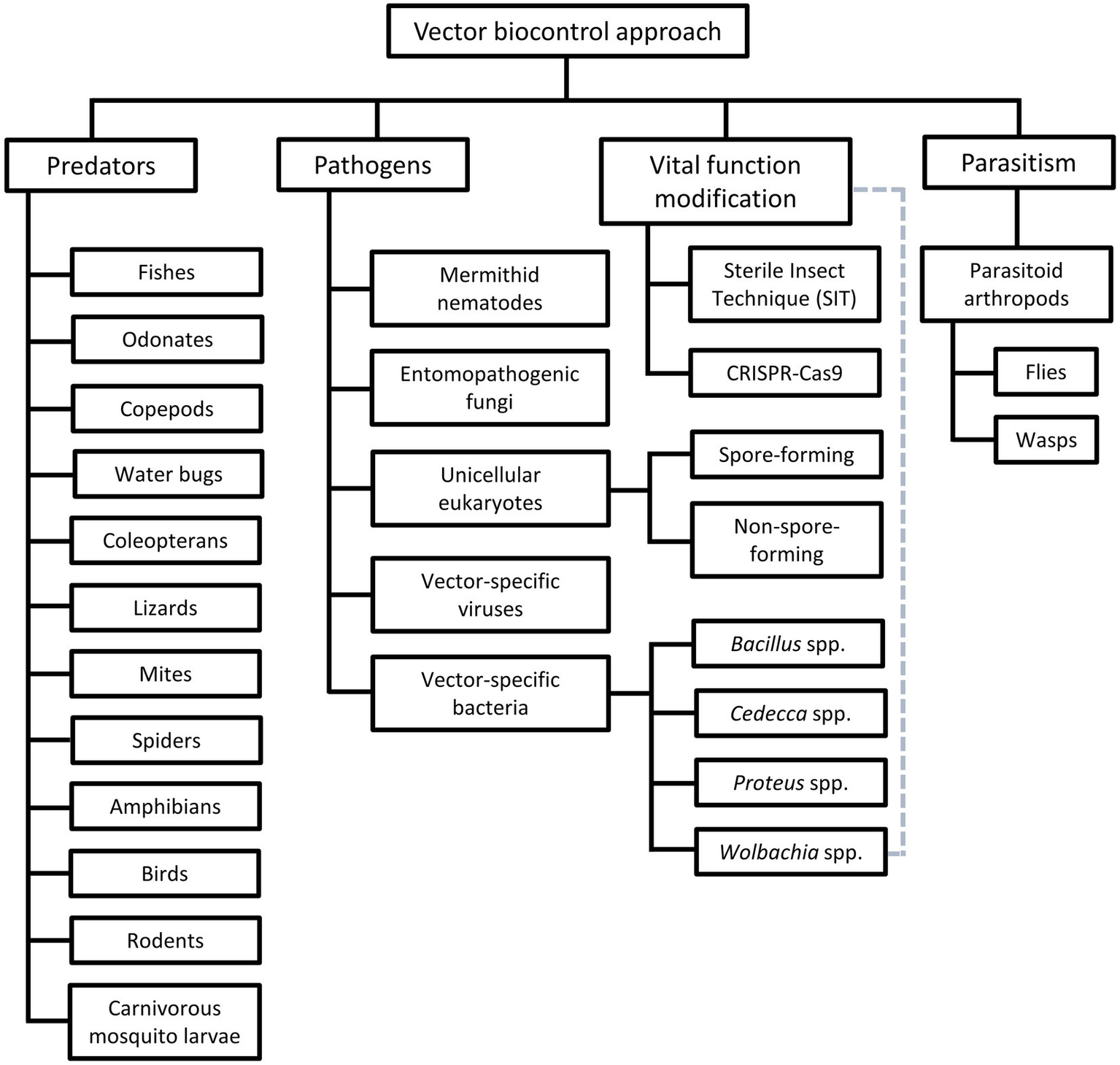

Vector biocontrol approach

Among the vector control strategies, biocontrol approaches have received increasing attention and popularity over the past two decades. Therefore, various organisms and strategies have been put forward as potential vector biocontrol candidates. In general, biocontrol approach explores the potential of using organisms and microorganisms to control the vector population (van den Bosch et al., 1982; Kamareddine, 2012; Okamoto and Amarasekare, 2012; Benelli et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2017; Kwenti, 2017; Thomas, 2018), based on the natural predation, pathobiological or parasitism relationship between the candidates and the targeted vectors (Table 3). Biological manipulation targeting certain vital functions of the vectors have been explored as a new approach in vector biocontrol (Gillette, 1988; Iturbe-Ormaetxe et al., 2011; Benelli et al., 2016). Theoretically, the biocontrol approach is more target-specific, thus of lower risk of imparting off-target effects to the environment. Prior to the new millennium, biocontrol approach was not as widely applied as its chemical and environmental counterparts, due to the relative ease of implementing the other two approaches (Quiroz-Martinez and Rodriguez-Castro, 2007; Shaalan and Canyon, 2009; Vershini and Kanagappan, 2014; Vinogradov et al., 2022). Nevertheless, biocontrol approach has received increasing attention following encouraging results obtained from the mass-application of Wolbachia-infected Aedes aegypti, genetically modified mosquitoes, sterile male triatomine bugs and tsetse flies. In fact, with the increased prevalence of VBZ and VBIAR, vector biocontrol approach may offer novel and sustainable strategies to control the transmission of these infections. Biological control approach can be categorized based on the natural relationship between the biocontrol agents and the respective vectors (Figure 2), as elaborated in the next few paragraphs of this review.

Table 3

| Biocontrol agent type | Biocontrol agent | Commonly used strains/species | Remark | Limitation | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predator | Larvivorous fish | Aphanius dispar Aplocheilus spp. Chanda nama Colisa spp. Carassius auratus Catla catla Cirrhinus mrigala Ctenopharyngodon idella Cyprinodontidae Cyprinus carpio Danio rerio Gambusia affinis Labeo rohita Macropodus cupanus Nothobranchius guentheri Oreochromis spp. Oryzias melastigma Poecilia reticulata Sarotherodon niloticus Tilapia spp. | Natural predator of larvae: reduces number of mosquito larvae | A threat to native aquatic fauna. Inconsistency in terms of efficacy | Connor (1922), Menon and Rajagopalan (1978), Rupp (1996), Walton (2007), Chandra et al. (2008a), Louca et al. (2009), Griffin and Knight (2012), and Subramaniam et al. (2015) |

| Dragonfly | Nymph and adult Anax immaculifrons Brachydiplax sobrina Neurothemis fluctuans Orthetrum chrysis Orthethrum sabina | Reduces the number of the vector population through feeding on immature and adult | Critically affected by water quality, thus field application can be limited | Sebastian et al. (1990), Singh et al. (2003), Chatterjee et al. (2007), Quiroz-Martinez and Rodriguez-Castro (2007), Shaalan and Canyon (2009), Vershini and Kanagappan (2014), Vatandoost (2021), and Ramlee et al. (2022) | |

| Larvivorous mosquito larva | Psorophora subgenus Psorophora Sabethes cyaneus Toxorhynchites spp. Lutzia spp. Sabethes spp. Trichoprosopon spp. Runchyomyia spp. Culex fuscanus Anopheles barberi Tripteroides spp. Topomyia spp. Wyeomyia subgenus Dendromyia Eretmapodites spp. Aedes subgenus Alanstomea Aedes subgenus Mucidus | Decreases number of mosquito larvae | Spatial limitations for application, especially for some sylvatic species. Risk of cannibalism among larvivorous mosquito larva | Chapman (1974), Lounibos (1980), Focks et al. (1985), Annis et al. (1989), Annis et al. (1990), Rawlins et al. (1991), Brown (1996), Mogi and Chan (1996), Amalraj and Das (1998), Collins and Blackwell (2000), Aditya et al. (2006), Benelli et al. (2016), Huang et al. (2017), Donald et al. (2020), and Hancock et al. (2022) | |

| Larvivorous copepod | Megacyclops spp. Mesocyclops spp. Macrocylops spp. | Reduces mosquito larvae density | Copepods are affected by water temperature, low oxygen content and accumulation of toxins in water. Some copepods are intermediate host for guinea-worm and fish tape worm | Marten et al. (1989), Lardeux et al. (1992), Manrique-Saide et al. (1998), Schaper (1999), Vu et al. (2005), Marten and Reid (2007), Soumare and Cilek (2011), Mahesh Kumar et al. (2012), and Vinogradov et al. (2022) | |

| Beetle | Diving beetle (Dystiscidae) Water scavenger beetle (Hydrophilidae) | Reduces number of vector immatures | Incomplete habitats overlap. Alternative prey preference. Emigration. Limited research | Juliano and Lawton (1990), Lundkvist et al. (2003), Chandra et al. (2008b), Shaalan and Canyon (2009), and Vinogradov et al. (2022) | |

| Water bug | Backswimmer (Notonectidae) Giant water bugs (Belostomatidae) Waterboatmen (Corixidae) | Reduces number of vectors: feeds by holding its prey with pincers and injecting a strong liquefying enzyme into it | Greatly affected by water quality, limiting its spatial reach to the vectors. Difficulty in mass production | Bay (1974), Murdock et al. (1984), Venkatesan and Jeyachandra (1985), Sankaralingam and Venkatesan (1989), Aditya et al. (2004), Aditya et al. (2005), Shaalan et al. (2007), Shaalan and Canyon (2009), Selvarajan and Kakkassery (2019), and Vinogradov et al. (2022) | |

| Mite | Acari spp. Eustigmaeus johnstoni (affects sand fly) Pimeliaphilus plumifer (affects true bugs) | Feeds on vector immature. Affects the physiological aspects of vector: reduces nymph molting rate, reduces adult longevity, increases mortality in 3rd–5th instar nymph, reduces number of viable eggs laid by infected female | Difficulty is mass-rearing | Martinez-Sanchez et al. (2007), Badakhshan et al. (2013), and Dinesh et al. (2014) | |

| Spider | Web-building spider. Hunting spiders (Active and passive hunter) | Feeds on vector immatures and adults | Consideration on different biological factors to ensure successful establishment of control | Ximena et al. (2005), Hadole and Vankhede (2013), Fischhoff et al. (2018), and Ndava et al. (2018) | |

| Lizard | Gehydra dubia Hemidactylus frenatus Tarentola mautitanica (prey: true bug) | Feeds on adults | Possible threat to native fauna | Castello and Gil Rivas (1980) and Canyon and Hii (1997) | |

| Frog and toad | Bufo spp. Euphlycytis spp. Hoplobatrachus spp. Polypedates cruciger Ramanella spp. | Predates on eggs of mosquito | Can be invasive toward native fauna | Raghavendra et al. (2008) and Bowatte et al. (2013) | |

| Bird | Scrub jay Chicken Yellow-billed oxpecker (Buphagus africanus) Red-billed oxpecker (Buphagus erythrorhycus) | Predates on ticks (scrub jay: ticks on deer; chicken: ticks on cattle; yellow-billed oxpecker: ticks on buffaloes; red-billed oxpecker: ticks on ungulate) | Oxpecker could induce wound enlargement on the mammalian host given that it prefers host with most ticks. Assessment of tick population needs to be performed before introduction programme (scrub jay and oxpeckers) | Moreau (1933), van Someren (1951), Mundy and Cook (1975), Bezuidenhout and Stutterheim (1980), Isenhart and DeSante (1985), Hassan et al. (1991), Mooring and Mundy (1996), Weeks (1999), and Plantan et al. (2012) | |

| Rodent | Sorex araneus | Predates on ticks | Not advisable as rodent transmits several diseases | Short and Norval (1982) | |

| Parasitism | Parasitoid arthropods | Tachinid fly (parasitizes true bug) Chalcid wasp (parasitizes tick) Ixodiphagus hookeri (Encyrtid wasp-parasitizes tick) | Immatures of vector is attacked when the eggs of the parasitoid arthropods hatch and feed on it | Highly sensitive to insecticides. Mass-rearing in laboratory can be difficult, especially the diet preparation | Mather et al. (1987), Tijsse-Klasen et al. (2011), Wang et al. (2014), Kwenti (2017), Wang et al. (2019), and Buczek et al. (2021) |

| Pathogens | Nematode | Mermithid nematode (Perutilimermis culicis, Romanomermis spp., Reeseimermis nielseni, Diximermis peterseni, Hydromermis churchillensis). Rhabditoid nematode (Neoaplectana carpocapsae) Stenernematid nematode (ticks) | Parasitic relationship: Reduces number of mosquitoes. Causes biological castrations through interference in mosquito reproduction | Limited resources on the parasitic effects of nematodes against the adult mosquitoes. Environmental parameters limitations such as temperature, pH, salinity, and oxygen level | Petersen et al. (1972), Petersen and Willis (1972), Reynolds (1972), Chapman (1974), Mitchell et al. (1974), Levy and Miller (1977), Molloy and Jamnback (1977), Zhioua et al. (1995), Peng et al. (1998), Samish and Glazer (2001), Secundio et al. (2002), and Poinar (2018) |

| Entomopathogenic fungus | Beauveria spp. Coelomomyces spp. Culicinomyces spp. Entomophthora spp. Lagenidium spp. Metarhizium spp. Phytium spp. Smittium spp. Fusarium oxysporum | Upon contact to external cuticle, toxins are released by the infective spores. Modifies physiology of insect: reduces likelihood for blood-feeding, survival, and fecundity | Slow killing. Production of zoospore is difficult and affected by UV irradiation. Some strains can affect non-target arthropods. Beauveria bassiana are inactive against adults in laboratory (Anopheles, Aedes, Culex). Entomophthora coronata has been reported to cause phycomycosis in man and horses. Smittium spp. has reduced pathogenicity against mosquitoes | Clark et al. (1966), Clark et al. (1968), Anderson and Ringo (1969), Ginsberg et al. (2002), Scholte et al. (2004), Scholte et al. (2007), Paula et al. (2011a,b), and Fischhoff et al. (2018) | |

| Non-spore-forming unicellular eukaryotes | Ciliate: Tetrahymena spp. Flagellate: (Crithidia spp. Blastocrithidia spp. Eugregarine Ascogregarina culicis Psychodiella spp. (found only in sand flies) Schizogregarine: Caulleryella spp. Helicosporida) | Stunts growth of larvae and increased mortality. Effects on host’s biological aspects especially on females are more profound in nutrient-deficient conditions | Pathogenicity highly depends on internal and external conditions. Host-specific | Corliss (1954, 1960), Chapman et al. (1967), Anderson (1968), Barrett (1968), McCray et al. (1970), Reynolds (1972), Wu and Tesh (1989), Sulaiman (1992), Mourya et al. (2003), Albicócco and Vezzani (2009), Lantova et al. (2011), and Lantova and Volf (2012, 2014) | |

| Microsporida | Thelohania spp. Nosema spp. Pleistophora spp. Stempellia spp. | Swollen thorax and abdomen/ benign subcutaneous pale spots on mosquito larvae. Reduces life span of infected female mosquito | Most of them cannot be transmitted perorally. Spores from different species are difficult to identify morphologically | ||

| Bacteria | Bacillus sphaericus Bacillus thuriengiensis Bacillus thuringiensin var. thuringiensin Cedecca lapegei Proteus mirabilis Different Wolbachia strains | Pathobiological effect against vectors: target is killed by an enterotoxin from crystal protein of spore. Suppresses late instars and pupae. Affects reproductive system. Shortens vectors’ life | Inconsistent efficacy | Lacey and Inman (1985), Novak et al. (1986), Arredondo-Jimenez et al. (1990), Hassanain et al. (1997), Robert et al. (1997), Stouthamer et al. (1999), Armengol et al. (2006), Lacey (2007), Panteleev et al. (2007), Hedges et al. (2008), Werren et al. (2008), Brelsfoard and Dobson (2009), Kambris et al. (2009), Moreira et al. (2009a), Wiwatanaratanabutr and Kittayapong (2009), Bian et al. (2010), Ritchie et al. (2010), Ahantarig and Kittayapong (2011), Hoffmann et al. (2011), Iturbe-Ormaetxe et al. (2011), Walker et al. (2011), Mousson et al. (2012), van den Hurk et al. (2012), Bian et al. (2013), Aliota et al. (2016a,b), Dutra et al. (2016), Jeffries and Walker (2016), Ahmad et al. (2017), Chouin-Carneiro et al. (2019) and Nazni et al. (2019) | |

| Virus | Mosquito-specific densovirus (MDV) Cytoplasmic polyhedrosis virus (CPV or near reovirus) Nuclear polyhedrosis virus (NPV or baculovirus) Deltabaculovirus (dipteran-specific NPVs) Mosquito Iridescent Virus (MIV or iridovirus) Entomopoxvirus (EPV) | Intranuclear protein inclusions in Anopheles subpictus. Infections in nuclei in midgut and gastric caeca of An. sollicitans. Kills fourth instar mosquito larvae | Host-specific. Slow killing, hence, studies are being performed by genetic modification of the virus to have quicker effect on the vectors | Anderson (1970), Warburg and Pimenta (1995), Jehle et al. (2006), Szewczyk et al. (2009), Szewczyk et al. (2011) | |

| Vital function modification | Sterile Insect Technique (SIT) | Tsetse fly Mosquito | Genetic suppression strategy by creating sterile male vector | Sex segregation of sterile insects in mass production. Inconsistent lifespan affecting release to the wildlife | Alphey and Andreasen (2002), Phuc et al. (2007), and Vreysen et al. (2014) |

| Release of Insects carrying a Dominant Lethal (RIDL) | Mosquito | Release of male vector carrying dominant lethal transgene to mate with wild female vector will results in the death of progeny due to the lethal effect from the transgene | Reduced biological fitness of modified insect, affecting release to the wild | Fu et al. (2010), Harris et al. (2012), Carvalho et al. (2015), Dong et al. (2018), and O’Leary and Adelman (2020) | |

| Genetic Sexing Strain (GSS) | Mosquito New World screwworm fly (Agriculture pest) | Genetically engineered male with insecticide resistance phenotype. Accidentally “leaked” females will be killed by the respective insecticide prior to release | Production difficulty | Fu et al. (2010) and Dong et al. (2018) | |

| CRISPR/Cas 9 system | Mosquito Sand fly | Manipulation of gene expression to alter vectorial capacity, survival and fertility of vector | Production difficulty, stability issues | Dong et al. (2018) |

List of available vector biocontrol agents.

Figure 2

Different groups of vector biocontrol approach. Gray dotted lines reflect the characteristics of the Wolbachia method that combines the features of biocontrol approaches mediated by pathogens and vital function modification.

Biocontrol via predators

The potential of prey–predator relationship in vector control was explored before the era of mass insecticide application. For example, attempts to reduce the larval population of Stegomyia calopus (vector of yellow fever) in Ecuador with freshwater fish were initiated as early as the 1910s (Connor, 1922). Various aquatic and amphibian animals were put forward as potential candidates to control mosquito population, based on their predatory nature to the targeted pests. In this review, emphasis is given to medically relevant examples. Of note, most of these predator-driven strategies target the aquatic stages of mosquitoes because the mosquito larvae share a relatively confined living space with the predators. Thus, the aquatic prey–predator encounter does not rely as much on the overlapping active hours of the prey and predator, as compared to the flying adults. In addition, efficient and persistent predation on the vector offspring will inevitably control the vector population, and hence disease transmission (Kumar and Hwang, 2006; Walker and Lynch, 2007; Louca et al., 2009; Griffin and Knight, 2012).

Among the predators, larvivorous fishes have a prolific history as a biocontrol agent against pests, particularly mosquitoes. Larvivorous fishes were introduced into over 60 countries in 20th century to control vector populations (Gerberich and Laird, 1985). Their popularity was attributed mainly to their adaptability to a wide variety of natural and man-made water bodies that serve as mosquito breeding grounds, as well as their rapid reproduction rates (Hadjinicolaou and Betzios, 1973; Motabar, 1978; Chandra et al., 2008a). Numerous field trials with these predators demonstrated between 70 and 97% reduction of mosquito larvae (Connor, 1922; Menon and Rajagopalan, 1978; Fletcher et al., 1992; Kumar et al., 1998; Chandra et al., 2008a; Louca et al., 2009; Griffin and Knight, 2012). For instance, Aphanius dispar (Arabian toothcarp) managed to suppress the population of Anopheles arabiensis and Anopheles gambiae in wells, cisterns and barrels in Djibouti (Louis and Albert, 1988). However, the application of larvivorous fish has raised several concerns. The effect of an alien species to the native fauna and flora needs to be considered and monitored carefully. For example, the continuous introduction of Gambusia affinis (Western mosquitofish) into Greece from 1927 to 1937 resulted in the decline of an endemic species Valencia letourneuxi (Corfu toothcarp), due to living resource competition between the two species (Economidis, 1995; Economidis et al., 2000). Similar adverse effects associated with G. affinis have been reported from Australia and United States (Motabar, 1978; Arthington, 1991; Walton, 2007).

Similarly, odonates (particularly the larvae) are ferocious and imperative predators of many insects. Members of the order Odonata include various dragonflies and damselflies (Shaalan and Canyon, 2009; Vatandoost, 2021). Given their high predation capacity, relatively long aquatic life cycle (usually 1–2 years), and shared aquatic larval habitat with mosquito juveniles, odonates are potential vector biocontrol candidates. Indeed, field trials demonstrated significant reduction of mosquito larvae in water reservoirs by dragonfly nymphs (Sebastian et al., 1980, 1990; Chatterjee et al., 2007; Mandal et al., 2008). For example, a trial release of dragonfly nymphs in Myanmar reported a significant decrease of Ae. aegypti population in 2–3 weeks, and the effect persisted till the end of the 4-month-long trial (Sebastian et al., 1990). Similar findings were reported from India (Mandal et al., 2008). The odonate adults are agile aerial predators that prey on many insects (Vatandoost, 2021). Nevertheless, diet analyses of wild-caught dragonfly adults inferred that mosquitoes are rarely taken in large numbers by odonate adults (Pritchard, 1964; Sukhacheva, 1996; Pfitzner et al., 2015). In addition, the active hours (feeding time) of odonate adults (most species are diurnal) do not overlap with the active hours of many medically important vectors (Pfitzner et al., 2015; Vatandoost, 2021). Furthermore, the lifespan of odonate adults is relatively short (1–8 weeks). Hence, the potential of odonate adults as vector biocontrol agents is not as attractive as their juveniles.

The population of many mosquito vectors can be controlled by another mosquito via predation. Larvae of mosquitoes from 13 genera prey upon larvae of other arthropods (Harbach, 2007). All members of genera Toxorhynchites, Lutzia and Psorophora (subgenus Psorophora) are obligate predators of other arthropod larvae (Steffan and Evenhuis, 1981; Annis et al., 1990; Rawlins et al., 1991; Collins and Blackwell, 2000; Aditya et al., 2006; Wilkerson et al., 2021; Hancock et al., 2022), whereas larvae of Sabethes, several species of Culex and Anopheles are facultative predators (Lounibos, 1980; Mogi and Chan, 1996; Shaalan and Canyon, 2009; Hancock et al., 2022). Of these, Toxorhynchites has received relatively high research attention, mainly because the adult is non-hematophagous (blood feeding), hence not imposing risk as pest or disease vector (Shaalan and Canyon, 2009). Previously, the release of Toxorhynchites amboinensis larvae led to a 45% reduction of Ae. aegypti population in urban areas of New Orleans (Focks et al., 1985). Similar success was reported with T. splendens (Annis et al., 1989; Aditya et al., 2006) and T. moctezuma (Rawlins et al., 1991). Apart from their direct effect via ferocious predation, the presence of Toxorhynchites larvae can delay the prey’s developmental time and increase the prey’s mortality. This is probably due to the stress experienced by the prey in the presence of the predator, or the predator-derived kairomones (Andrade, 2015; Zuharah et al., 2015). Nevertheless, the mechanism behind this effect has yet to be completely deciphered. Despite the earlier reported success, the application of Toxorhynchites as biocontrol agent has been hindered by several factors. Firstly, sylvatic species such as T. rutilus are not well adapted to urban environment, which restricts its application despite the good predation capacity (Focks et al., 1983). Nevertheless, a more recent surveillance demonstrated the presence of T. rutilus in urban areas, albeit of low numbers (Wilke et al., 2019). Indeed, this discovery has reignited the hope of applying Toxorhynchites as a vector biocontrol agent in urban areas (Schiller et al., 2019). Besides, the slow population expansion of Toxorhynchites is another challenge that needs to be overcome. Under the natural settings, Toxorhynchites produces few offspring, which limits their efficacy and capacity in vector biocontrol. This is further aggravated by the cannibalistic nature of Toxorhynchites immatures, especially under food-restricted conditions (Donald et al., 2020).

Copepods of genera Megacyclops, Mesocyclops, and Macrocyclops are crustaceans that feed primarily on the first instar of mosquito larvae. Copepods can adapt to a large variety of water bodies and micro aquatic habitats such as phytotelmata (structures of terrestrial plants that allow formation of water pockets). Such high adaptability allows copepods to be explored as vector biocontrol agents in different settings (Vinogradov et al., 2022). In fact, the discovery of copepod’s potential in vector biocontrol was rather accidental, following an observed reduction of Ae. aegypti and Ae. polynesiensis larvae from ovitraps set in a study site at Tahiti, after unintentional introduction of copepods to the ovitraps (Riviere and Thirel, 1981). Subsequently, field trials from different regions confirmed the effectiveness of copepods in various water bodies (including drains and land crab burrows) against larvae of medically important mosquitoes, particularly of genera Aedes and Ochlerotatus (Lardeux et al., 1992; Kay et al., 2002). Importantly, the introduced copepods can adapt and colonize nearby water bodies, allowing sustained effort of mosquito larval control (Kay et al., 2002). Although being used mainly against Aedes spp., copepods have been used against other vectors such as Anopheles spp. and Culex spp. (Riviere and Thirel, 1981; Marten et al., 1989; Lardeux, 1992; Lardeux et al., 1992; Vu et al., 1998; Schaper, 1999; Marten et al., 2000; Kay et al., 2002; Zoppi de Roa et al., 2002; Soumare and Cilek, 2011). Despite their ability to adapt to different sizes of water bodies, copepods are particularly sensitive to temperature changes, chlorine content, low oxygen levels, and presence of toxin within the water (Brown, 1996; Vinogradov et al., 2022). Moreover, it is important to highlight that several species of copepods serve as the intermediate hosts of medically important parasites such as Drancunculus medinensis (guinea-worm) and Dibothriocephalus latus/ Diphyllobothrium latum (fish tape worm; Marten and Reid, 2007; Vinogradov et al., 2022). Therefore, careful consideration and planning must be done prior to application of this method. For example, non-vector copepod species can still be considered as biocontrol agents in certain parts of Africa that are endemic for dracunculiasis (Marten and Reid, 2007).

Water bugs, such as the backswimmers (family: Notonectidae), giant water bugs (family: Belostomatidae) and waterboatmen (family: Corixidae) are important predaceous insects under the order Hemiptera (Shaalan and Canyon, 2009). The potential of Anisops assimilis (common backswimmer) to control mosquito population was reported officially for the first time in 1939, following the observation that the backswimmer-harboring water containers were void of mosquito larvae, in contrast to the surrounding backswimmer-free water bodies that were infested with active mosquito larvae (Graham, 1939). Although field and laboratory trials using water bugs to control mosquito larvae exhibited promising results, they are hardly utilized as biocontrol agents due to the high cost and difficulty of mass rearing, as well as logistical challenges (Bay, 1974; Murdock et al., 1984; Venkatesan and Jeyachandra, 1985; Sankaralingam and Venkatesan, 1989; Aditya et al., 2004, 2005, 2006; Selvarajan and Kakkassery, 2019).

Predatory coleopterans from the families Dytiscidae (diving beetle) and Hydrophilidae (water scavenger beetle) are commonly found in ground pools, permanent and temporary ponds (Shaalan and Canyon, 2009). Despite the lower research interest, several studies on the predatory effect of beetles on mosquito reported promising results (Nilsson and Soderstrom, 1988; Juliano and Lawton, 1990; Nilsson and Savensson, 1994; Aditya et al., 2006; Chandra et al., 2008b). However, the efficacy of coleopterans as vector biocontrol agents may be compromised by their diet preference (when mosquitoes are not the only insects presented), species emigration and cannibalism (Juliano and Lawton, 1990; Lundkvist et al., 2003).

Currently, the potential of predators discussed above has not been thoroughly explored, and most of the reported studies focused on mosquitoes (Kim and Merritt, 1987; Werner and Pont, 2003). Notably, several natural predator-based biocontrol strategies have been attempted against non-mosquito vectors, notably the parasitic VBIAR. For example, Tarentola mautitanica, an insectivorous lizard, has been proposed as a candidate to control the population of Triatoma infestans (kissing bug) that spreads Chagas disease (Castello and Gil Rivas, 1980). Mites and spiders have been suggested as biocontrol agents of Phlebotomus spp. (sand fly) that transmits leishmaniasis (Dinesh et al., 2014).

Pathogenesis-mediated vector biocontrol

Besides predatory animals, pathogens have been proposed as biocontrol agents against vectors. In fact, a number of these pathogens have been applied in the field. These candidates vary in sizes and behavior, encompassing both prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms. The nematodes are probably the largest candidates on the list. The mermithids are members of an endoparasitic nematode family. These nematodes are highlighted as potential vector biocontrol candidates, due to their parasitic relationship with various arthropods and several arachnids (Stabler, 1952; Chapman, 1974). The hatched pre-parasitic juveniles of mermithid nematodes aggressively infect mosquito larvae (usually the early instars) by paralyzing the targeted hosts, followed by penetration of cuticular wound to establish the infection (Sanad et al., 2017). Once infected, the mermithid parasites take over the cellular function regulatory authority of their hosts. If infection occurs during the early larvae instar, the parasitized mosquito larvae are halted from pupating as the infecting parasites develop within (Stabler, 1952; Allahverdipour et al., 2019). When the nutrient resource supplied by the infected host is exhausted, the nematode, now at its third-stage juvenile post-parasite stage, emerges out of the host, which results in the death of the host (Stabler, 1952). The emerged post-parasite stage then molts into the free-living adult to reproduce and lay eggs. Multiple mermithids may repeatedly infect an already infected larva, giving rise to a phenomenon called superparasitism (Sanad et al., 2017). Different research groups have demonstrated the mosquito larvicidal effect of several mermithids such as Romanonermis iyengari (against Ae. aegypti, Ae. albopictus, An. gambiae, Anopheles culicifacies, Anopheles stephensi, Anopheles subpictus, Armigeres subalbatus, Culex pipiens, Culex quinquefasciatus, Culex sitiens, Culex tritaeniorhynchus, and Mansonia annulifera), Diximermis peterseni (against Anopheles crucians, Anopheles quadrimaculatus, and Anopheles punctipennis) and Strelkovimermis spiculatus (against Aedes albifasciatus and Cx. pipiens; Petersen and Willis, 1974; Levy and Miller, 1977; Poinar and Camino, 1986; Santamarina Mijares and Perez Pacheco, 1997; Paily and Balaraman, 2000; Sanad et al., 2013, 2017; Abagli and Alavo, 2019; Abagli et al., 2019). However, the lack of culturable mermithids hinders mass application of this nematode as a biocontrol agent (Kendie, 2020).

Entomopathogenic fungi are another group of insect pathogens that have been explored as a potential vector biocontrol agent (Chapman, 1974). Fungi of genera Beauveria and Metarhizium have been shown to exert high mortality to medically important mosquitoes of genera Anopheles, Culex and Aedes (Blanford et al., 2011; Accoti et al., 2021). The fungal infection exhausts the mosquitoes due to increased metabolic rate and reduces their frequency of taking blood meals. As a result, the lifespan, oviposition rate, as well as the chance of infected mosquitoes to acquire and transmit medically important pathogens reduces greatly (Blanford et al., 2011). Interestingly, the fungi have been reported to affect both the larval and adult stages of mosquitoes (Blanford, 2005; Blanford et al., 2011). However, the virulence of fungi is influenced by various factors (Scholte et al., 2007; Paula et al., 2011b; Alkhaibari et al., 2017). For example, most fungi may lose their potency after a few months (Scholte et al., 2007). Besides, the lethality of entomopathogenic fungi is influenced by the nutritional state of the targeted vector (Paula et al., 2011b). Furthermore, different forms of fungi may demonstrate different potency against the mosquitoes. For instance, Ae. aegypti is more susceptible to the blastospores of Metarhizium, whereas Cx. quinquefasciatus is more susceptible to the conidia forms. On the other hand, An. stephensi is susceptible to both forms of Metarhizium (Alkhaibari et al., 2017). Notably, it is difficult to culture and mass produce fungi (Accoti et al., 2021). More importantly, these entomopathogenic fungi have been reported to cause symptomatic infections in immuno-compromised humans, raising safety concerns regarding this vector biocontrol agent (Henke et al., 2002; Tucker et al., 2004; Lara Oya et al., 2016; Goodman et al., 2018). These drawbacks render fungi a less attractive vector biocontrol option.

Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelis (Bti) is a bacterium commonly used as a household larvicide. This bacterium produces delta endotoxins (known as the “Cry” or “Cyt” toxins) during its sporulation, which are potent insecticide proteins (Tabashnik, 1992; Wu et al., 1994; Ben-Dov et al., 1995). The toxin has been demonstrated to kill larvae of Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus effectively, by disrupting the osmotic balance of the midgut epithelial cells upon ingestion (Chapman, 1974; Promdonkoy and Ellar, 2003; Lacey, 2007). Importantly, Bti does not pose direct ecological or health threats as it does not affect any off-target organisms including fishes, birds, mammals, and many other insects (Fayolle et al., 2015; Poulin and Lefebvre, 2018; Poulin et al., 2022). Nevertheless, research is underway to evaluate the indirect impact of Bti application, particularly its impacts on local ecological systems (Novak et al., 1986; Arredondo-Jimenez et al., 1990; Kumar et al., 1998; Ritchie et al., 2010; Fayolle et al., 2015; Poulin and Lefebvre, 2018; Poulin et al., 2022). Resistance against Cry toxin has yet to be reported. Nevertheless, development of tolerance toward some of the Cry toxins (Cry4Aa and Cry11Aa) was reported in a population of Ae. sticticus (Tetreau et al., 2013).

Viruses, such as the mosquito-specific densoviruses (MDV) may be used against the vectors too (Chapman, 1974). MDVs are highly infectious to its targets due to its capability of establishing vertical and horizontal transmission (Johnson and Rasgon, 2018). Upon infection, MDV causes a plethora of pathogeneses on their targets, which lead to apoptosis of infected larvae (Roekring and Smith, 2010), and shortening of adult lifespan (Suchman et al., 2006). Interestingly, MDV has been shown to reduce the viral load of type II DENV in Ae. albopictus (Wei et al., 2006). Besides, MDV can be genetically modified to cater for different conditions of vector control. For instance, a recombinant Ae. aegypti densovirus (AeDNV) expressing BmK IT1(an insect-specific toxin) was demonstrated to exert higher pathogenicity to Ae. albopictus (Gu et al., 2010). Despite these advantages, large-scale implementation of MDV-mediated vector biocontrol strategy may not be easy due to the relatively low stability of viral particles outside the hosts (Johnson and Rasgon, 2018). Nevertheless, advancement of technology may make this method more feasible for mass application in the future.

The potential vector biocontrol candidates above share a drawback that need to be overcome for mass application. It remains uncertain how sustainable these biocontrol agents can exist in the environment for a long-lasting controlling effect against the vector population. This is especially crucial for VBZ and VBIAR with complex and sporadic transmission profiles. Besides, candidates with healthcare risk concerns should not be employed until all doubts are scientifically cleared. Nevertheless, biocontrol candidates such as Bti and entomopathogenic fungi have been commercialized recently (Akutse et al., 2020).

Manipulation of vital biological functions

Alternative approaches that revolve around the manipulation of vector’s biology have been explored to develop a strategy that preserves the relatively target-specific nature of most pathogenesis-mediated biocontrol approaches while overcoming the drawbacks faced by these strategies. Hence, genetic manipulation of vector’s vital functions has gained increasing research attention. Sterile Insect Technique (SIT) is one of the successful examples of such approach (Baumhover et al., 1955; Lofgren et al., 1974; Patterson et al., 1977). In the SIT approach, the male vector is made infertile via radiation exposure or chemosterilization (Serebrovsky, 1940; Baxter, 2016). Subsequently, when these sterile males are released into the wild and mate with females, non-viable offspring are produced. As a result, the targeted vector population is reduced. This technique was successfully employed to control the infestation of the New World screwworm fly (Cochliomyia hominivorax) in the United States, whose maggots are capable of causing myiasis with severe tissue damages (Baumhover et al., 1955). SIT worked well against C. hominivorax because each female fly mates only once. As SIT-modified insects do not produce any offspring, the success of this technique depends on the persistent release of sterile male specimens to compete with the fertile wild type (WT) males for mating. Subsequently, this technique was attempted against mosquitoes in the 1970s, which yielded encouraging results. The population of Anopheles albimanus in El Salvador was reduced by 99% after implementing this technique for 5 months (Lofgren et al., 1974). Several mosquito-targeting field trials were performed in Burkina Faso, France, India, Myanmar, and United States. The experimented mosquitoes were Ae. aegypti, An. gambiae, An. quadrimaculatus, Cx pipiens, and Cx quinquefasciatus (Weidhaas et al., 1962; Dame et al., 1964; Laven, 1967; Davidson et al., 1970; Patterson et al., 1970; Curtis, 1976; Grover et al., 1976; Patterson et al., 1977; Curtis et al., 1982). These field trials yielded mixed results. For example, in India, the population of targeted mosquitoes was not effectively controlled with this approach, due to the immigration of mated WT females from the locations adjacent to the trial sites. In addition, political turmoil significantly affected the execution of this approach, which confounded the success of this strategy (Curtis, 1976; Curtis et al., 1982).

Despite the reported success, SIT is accompanied with several drawbacks. Firstly, there are concerns among the public members regarding the off-target effect of chemosterilizing agents to the environment (Bartumeus et al., 2019). Laboratory bioassays on non-target predators such as the common house spider (Achaeranea tepidariorum) revealed the significant reduction in fertility among the spiders that consumed the chemosterilized mosquitoes (Bracken and Dondale, 1972). Nevertheless, this issue can be overcome via simple bulk detoxification using acid and alkaline, which eliminates residues of chemosterilizing agents without compromising the efficacy of this method (Sharma, 1976). Secondly, the difficulty to precisely segregate male and female specimens in the insect colony implies the possibility of sterilizing female specimens by mistake (Sharma et al., 1976; McInnis et al., 1994; Parker, 2005). Accidental release of these mistakenly treated females will result in mating competition with the fertile WT females. As a result, the dispersal of sterile males will be compromised. In addition, radiation used in sterilization will significantly shorten the lifespan of these irradiated insects, which compromises the success of this technique in the field (Alphey and Andreasen, 2002). To overcome this issue, the concept of homozygous female-specific lethal genes has been applied, giving rise to techniques such as Genetic Sexing Strain (GSS) and Release of Insects carrying a Dominant Lethal Gene (RIDL; Franz, 2005; Fu et al., 2010; Harris et al., 2011; Carvalho et al., 2015; O’Leary and Adelman, 2020). RIDL enables selection of the developmental stage corresponding to the manifestation of engineered lethal traits. The insertion of a repressible dominant lethal transgene into the mosquito genome confers conditional fatality (such as tetracycline-dependent survival) to its late juvenile stage. In this approach, the engineered male mosquitoes are released to mate with the WT females. Instead of completing metamorphosis, the produced juveniles that carry a copy of the engineered gene will die in the absence of tetracycline (Phuc et al., 2007). Indeed, field trials of Ae. aegypti OX513A in Cayman Islands and Brazil demonstrated strong suppression of the targeted mosquito population (Harris et al., 2012; Carvalho et al., 2015). In addition, female-specific flightless phenotype and DENV-susceptible phenotype that are genetically engineered in Ae. aegypti have improved the gender segregation and impeded vector competence to DENV, respectively (de Valdez et al., 2011; Buchman et al., 2020). These techniques minimize the “leakage” of “accidentally treated females” into the wild (Franz, 2002; Calkins and Parker, 2005; Franz, 2005; Koskinioti et al., 2021). In general, the attempts to overcome the shortcomings of SIT revolve around gene editing, which was highly challenging decades ago. However, the discovery and establishment of CRISPR/Cas9 system allows gene editing to be performed much more easily (Gupta et al., 2019). This molecular advancement facilitates the application of SIT against different vectors.

Besides facilitating SIT in vector biocontrol approach, CRISPR/Cas9 can be applied to genetically design arthropod vectors that are not receptive to pathogens transmitted by them under normal circumstances. For example, the knock-out of FREP1 gene has been shown to reduce the susceptibility of An. gambiae to Plasmodium spp. (Dong et al., 2018). Gene drive is another genetic engineering concept that has enjoyed a great push in vector control research following the establishment of CRISPR/Cas9 technology. The CRISPR/Cas9- integrated gene drive method allows the targeted genes to be propagated and inherited much more rapidly than the Mendelian rates, resulting in fast replacement or displacement of the targeted traits in a population (Leung et al., 2022). Recently, this technology has been applied on An. gambiae, resulting in a successful halting of Plasmodium development within the genetically modified mosquitoes, as well as compromising the survival of the homozygous transgenic females (Hoermann et al., 2022). In addition, other gene editing methods, such as the application of homing endonuclease genes (HEG) have been explored to control the malaria vectors (Windbichler et al., 2007; Deredec et al., 2011). Nevertheless, such genetically engineered mosquitoes suffered compromised fitness that hindered their sustainable establishment in the wild. This drawback is in fact a major concern, as modification of one gene may lead to unexpected outcomes on the experimented organism (Resnik, 2014, 2017). If the mutants with unexpected and undesirable traits (following gene editing) thrive in the wild, the ecosystem may be threatened in an unprecedented manner. Nevertheless, the successful application of vital function modification to control a myiasis causative agent with wild and domestic animals as reservoirs reflects the great potential of this approach to control VBZ and VBIAR. Importantly, techniques stemming from this approach should be tested, evaluated, and validated thoroughly before mass application.

Wolbachia as a novel vector biocontrol approach

As elaborated earlier, the pathogenesis-mediated biocontrol agents are arthropod pathogens that shorten the lifespan of vectors, whereas genetic manipulation of arthropod vital functions works by halting the vectors’ population expansion. The application of Wolbachia in vector biocontrol is a unique approach that combines the characteristics of both approaches. Wolbachia are maternally inherited, gram-negative, obligate intracellular endosymbiotic bacteria found in many arthropods such as mites, spiders, scorpions and isopods (Werren et al., 2008). Wolbachia are found in various organs and tissues within the infected arthropod (Werren, 1997; Werren et al., 2008). Besides, medically important filarial nematodes carry Wolbachia as well (Lau et al., 2015).

Approximately 60% of the insects are positive for Wolbachia. Interestingly, Ae. aegypti is Wolbachia-free under normal condition (Kittayapong et al., 2000; Rasgon and Scott, 2004). In the early 2000s, Xi et al. (2005) successfully performed an experimental infection on Ae. aegypti with Wolbachia wAlbB strain (henceforth wAlbB) derived from Ae. albopictus. Subsequently, this finding was explored further, with trial release of wAlbB-infected Ae. aegypti in several locations reported increased resistance of the vector to DENV, ZIKV, and CHIKV (Bian et al., 2010; Aliota et al., 2016a,b; Chouin-Carneiro et al., 2019; Nazni et al., 2019). Meanwhile, the infection of Ae. aegypti by another more virulent strain of Wolbachia (wMelPop strain) has been shown to reduce the number of Ae. aegypti significantly (Rasgon et al., 2003; Ritchie et al., 2015). These findings highlight the potential of Wolbachia as a tool in vector control program. Therefore, the mechanisms behind the effects cast by Wolbachia on the infected mosquitoes have received increasing research attention over the past two decades.

Wolbachia have evolved and developed various mechanisms to manipulate the host’s cellular biology toward their survival advantage, namely cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI), parthenogenesis, feminization, and male killing (O'Neill et al., 1997; Werren, 1997; Werren et al., 2008). CI happens when a Wolbachia-infected male mates with either a Wolbachia-negative female or a female infected with a different strain of Wolbachia, resulting in non-viable progeny (Werren, 1997). This principle forms the basis of “Incompatible Insect Technique (IIT)” that drives many Wolbachia-mediated biocontrol programs against Ae. aegypti in China, the United States, and Singapore (Ritchie et al., 2015; Mains et al., 2019; Zheng et al., 2019; Soh et al., 2021). Parthenogenesis refers to the development of eggs into progenies without fertilization, whereas feminization involves development of genetic male into female. Wolbachia has been shown to induce feminization in several crustaceans and insects (Werren, 1997; Cordaux et al., 2001; Kageyama et al., 2002; Negri et al., 2006; Werren et al., 2008; Asgharian et al., 2014; Scola et al., 2015). Meanwhile, male killing happens when the affected males experience a significantly shorter lifespan than the affected females. CI, parthenogenesis, feminization, and male killing trigger disruption of gender ratio in the affected population toward female dominance. Using these strategies, Wolbachia manipulates the population structure of the infected arthropods, which facilitates the spread and establishment of Wolbachia in the wild (Hoffman and Turelli, 1997; Werren, 1997; Werren et al., 2008). Coupled with the reported resistance to virus infection by the Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes, the establishment of Wolbachia in the vector population may suppress the transmission of these pathogens to humans. In fact, countries such as Malaysia, Indonesia, Laos, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, Australia, Fiji, Vanuatu, Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico have released Wolbachia -infected female Ae. aegypti to establish a stable Wolbachia-infected mosquito colony in the wild (Nazni et al., 2019; World Mosquito Program, 2022). Besides mosquitoes, Wolbachia has been explored for the control of black flies and sand flies. However, difficulties in colony maintenance of black flies and sand flies, coupled with the relatively low Wolbachia load post-infection in these insects giving rise to the undetectable CI among these insects. This implied the unsuitability of Wolbachia for the control of these non-mosquito vectors. Therefore, the versatility of the Wolbachia biocontrol approach remains to be validated (Crainey et al., 2010; Bordbar et al., 2014).

Despite the promising advantages of Wolbachia-mediated vector biocontrol approach, this method has several shortcomings and concerns. Similar to SIT, the Wolbachia method faces the issue of accidental “female leakage” that may compromise the efficacy of IIT-driven vector control strategy. For instance, IIT that incorporates Wolbachia can be dampened by mass production. Accidental release of Wolbachia-infected females during field trial could affect the population suppression goal. Nevertheless, this may not be considered as an absolute disadvantage, as Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes have been claimed to be less susceptible to the medically important pathogens that they carry (Bian et al., 2010; Nazni et al., 2019). To date, the long-term impact of Wolbachia on the targeted mosquitoes has not been well studied, partly due to the relatively short discovery history of this vector biocontrol candidate. Furthermore, the interaction dynamics among the arthropod host, Wolbachia, and the medically important pathogens carried by the arthropod remains to be fully deciphered. Nevertheless, few studies on this topic revealed interesting findings. For example, a previous study demonstrated that the Wolbachia-infected Culex tarsalis became more susceptible to West Nile Virus, with much higher viral load post-infection, as compared to the Wolbachia-free specimens (Dodson et al., 2014). Since Wolbachia has been shown to interfere with interactions between the arthropod host and the medically important pathogens that it carries, it is of utmost importance to consistently assess the efficacy and impact of Wolbachia deployed in vector control programs. Besides, the wMelPop-related strains have been demonstrated to be temperature-sensitive, raising doubts about the sustainability of this approach in areas with higher temperature (Ulrich et al., 2016; Ross et al., 2017). Succinctly, these concerns deserve more research attention despite the higher research difficulty, where longitudinal study covering adequately long duration is needed.

Besides, concerns have been raised regarding the possibility of Wolbachia to cause pathology to humans. Although Wolbachia can be found in mosquito salivary glands, the bacteria are not available in saliva, as backed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) screenings (Wu et al., 2004; Moreira et al., 2009b). In addition, Wolbachia are larger than the mosquito salivary duct (Moreira et al., 2009b). Hence, it is relatively unlikely for the bacteria to be transmitted to humans via mosquito bites. Moreover, human volunteers exposed to Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes over extended period of time revealed absence of antibody specific to Wolbachia in their blood (Popovici et al., 2010). Of note, responses to Wolbachia or Wolbachia-derived antigens by other key players in human immune system remained unclear. Based on currently available information, Wolbachia application has been considered as a relatively safe vector biocontrol approach. There are environmental concerns regarding this approach as well. In fact, the major environmental concern is extrapolated from the public health concern, where Wolbachia may spread to other organisms across the mosquito-related food chain in the ecosystem. This may disrupt the ecosystem dynamics, hence threatening the biodiversity in the affected environment. Fortunately, Wolbachia has been proven to be unable to establish itself throughout the mosquito-associated food chain (Popovici et al., 2010). Notably, natural cross-species infestation of Wolbachia is extremely rare (Werren et al., 1995; Werren, 1997), let alone a sustained establishment that allows vertical transmission (Hoffman and Turelli, 1997; Turelli, 2010).

Importantly, Wolbachia vector control approach may work well against a disease transmission that involves only one species of arthropod as vector. The effects of Wolbachia infection varies with different species of vectors. Hence, infections with multiple vectors, or those with incomplete list of vectors cannot employ this method as vector control program. The clearance of one vector by the bacteria may allow other vectors to thrive, rendering the disease control futile. Knowlesi malaria is an example of VBZ with multiple vectors, and the list of knowlesi malaria vectors is expanding for the moment (Ang et al., 2020; Jeyaprakasam et al., 2020; Pramasivan et al., 2021; Vythilingam et al., 2021). Apart from this, the actual efficacy of Wolbachia approach to reduce disease transmission has been questioned. Over the past few years, an increasing number of countries have participated in the release of Wolbachia-infected Ae. aegypti. Nevertheless, many of these countries still experience increased burden of dengue transmission after persistent release of these mosquitoes (Kementerian Kesihatan Malaysia, 2022). The difficulty to establish stable Wolbachia colony within the environment, stability and sustainability of this method in the field, and relative attractiveness of Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes during mating may contribute to the challenges faced by this approach to secure a more obvious disease transmission chain breakage in these countries. Obviously, more investigations are needed to better understand this approach, and its practicality, as well as its sustainability in the field.

Prospects and challenges of vector control against VBZ and VBIAR

The control and eradication of VBZ and VBIAR hardly rely on a single approach of vector management, due to the complexity of their transmission circuit. Hence, the application of integrated vector management (IVM) that incorporates multiple vector control approaches may increase the success rate of breaking the transmission circuit of these infections (WHO, 2012). To implement a successful and sustainable IVM, the components of IVM triads (biological, environmental, and chemical) should be covered during the designing of the vector control plan (Figure 3). Adaptation and customization of vector control strategies according to the targeted locations are required to ensure high success. For example, the landscape of a targeted location can be modified to facilitate the implementation of vector biocontrol strategies. At the same time, environment-friendly chemicals that can promote biocontrol strategy (such as predator attractants and pheromone-like substances) can be applied. IVM is a multi-prong approach against the vectors, where the selected strategies may complement each other to bring down the vector population. Moreover, IVM may minimize the risk of complete failure faced by a vector control program, as other components in the IVM may continue to work normally when one component is breaking down. For instance, ORS (chemical approach) may be completely stopped during the total lockdown of sudden onset (as exemplified by the COVID-19 pandemic-triggered lockdown in many countries). If the affected area has a well-constructed and maintained drainage system that hampers oviposition by the vectors (environmental management approach), the vector population in that area may not increase after ORS is brought to an abrupt halt. In short, multiple components should be explored to synergize the vector control effort.

Figure 3

Integrated Vector Management (IVM) involving different components in planning and implementation. Multiple components are factored into an IVM strategy to optimize the output of vector control.