- 1College of Life Science and Technology, Tarim University, Alar, Xinjiang, China

- 2State Key Laboratory Incubation Base for Conservation and Utilization of Bio-Resource in Tarim Basin, Alar, Xinjiang, China

- 3Department of Nursing, The First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, China

Tumor cells undergo extensive metabolic reprogramming during malignant proliferation, with serine—a key nonessential amino acid—playing multiple roles in tumor metabolism. To maintain high serine levels, tumor cells upregulate phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase to enhance endogenous synthesis and concurrently increase exogenous uptake. Serine deprivation demonstrates antitumor potential across various malignancies; however, its clinical application remains limited by inadequate tumor selectivity and systemic toxicity. Recent advances in nanodelivery systems offer precise strategies to modulate tumor serine metabolism. Serine deprivation via these systems improves tumor-specific targeting while minimizing off-target toxicity to normal tissues. Therefore, this review aims to outline serine metabolism and its regulatory networks, evaluate the therapeutic potential and limitations of serine deprivation, and highlight recent advances in nanodelivery strategies targeting serine metabolism for cancer therapy, thereby providing insights for the development of novel anticancer approaches.

1 Introduction

Tumor cell proliferation and survival depend on their unique metabolic reprogramming, characterized by altered energy metabolism and elevated demand for biomolecules such as amino acids, nucleotides, and lipids (1, 2). Advances in tumor metabolism highlight the regulatory mechanisms of metabolic reprogramming—recognized as a hallmark of malignant tumors (3, 4)—as a pivotal focus in tumorigenesis and progression (5). Tumor cells reprogram their metabolic pathways to meet elevated energy demands, generate metabolic precursors essential for rapid proliferation, and supply substrates for macromolecule biosynthesis, including proteins (6), lipids (7), and nucleic acids (8, 9). Among these phenomena, the “Warburg effect” exemplifies tumor metabolic reprogramming, where glucose is preferentially converted to lactate under aerobic conditions instead of producing ATP efficiently via oxidative phosphorylation (10). This phenomenon is a hallmark of autonomous metabolic reprogramming across diverse malignant tumors. Its discovery has fundamentally advanced the field by initiating extensive investigations into the mechanisms of metabolic reprogramming in cancer (11). Beyond the glucose metabolic abnormalities of the Warburg effect, tumor cells exhibit additional metabolic dysregulation, particularly in lipid (12) and amino acid metabolism (13). Amino acids, the primary cellular nutrients and energy sources after glucose, serve as essential substrates for protein synthesis. Reprogrammed amino acid metabolism is central to tumorigenesis and cancer progression (14, 15).

Amino acid metabolic reprogramming involves coordinated alterations in uptake rates, metabolic pathways, key metabolic enzyme expression, and metabolite production within tumor cells during tumorigenesis and progression. These systemic modifications enable them to meet the demands of rapid proliferation and facilitate survival within the hostile tumor microenvironment (16, 17). Across diverse tumor types, amino acids—glutamine, serine, arginine, tryptophan, and aspartate—drive metabolic reprogramming and regulate key biological processes including proliferation, invasion, migration, and immune evasion (15, 18–20). Serine is the third most consumed nutrient by tumor cells, after glucose and glutamine, and represents the second-largest amino acid—associated metabolic reprogramming event after glutamine (21, 22). Although glutamine metabolism has been widely studied in the context of tumor metabolic reprogramming, serine metabolism is emerging as a key focus in cancer metabolism research (23, 24). Serine is a central node in one-carbon metabolism (25–27), acting as a substrate for protein synthesis (28), a methyl-group donor, and a phospholipid precursor that supports nucleotide biosynthesis and membrane biogenesis—processes essential for malignant cell proliferation (29, 30). Tumor cells enhance serine metabolism by upregulating the phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PHGDH)-mediated de novo synthesis pathway (31, 32) and activating exogenous transport systems (33).

Across diverse tumor models, inhibition of the serine synthesis pathway (SSP) or exogenous serine uptake suppresses proliferation, promotes immune infiltration, and inhibits metastasis, highlighting the blockade of serine metabolism as a promising target for antitumor therapy (34, 35). Nevertheless, conventional serine-deprivation strategies face several challenges, including limited tumor targeting specificity (36), off-target effects on serine uptake in normal cells (37), and tumor cell adaptation to evade therapeutic pressure through the activation of compensatory metabolic pathways, such as upregulated SSP activity (38). These limitations compromise the efficacy and safety of such therapies. Recent advances in the development of nanodelivery systems offer innovative solutions to address these challenges (39). Nanocarriers with active or passive targeting capabilities enable selective accumulation of therapeutics in the tumor microenvironment or specific tumor cells, thereby significantly enhancing antitumor efficacy while reducing off-target toxicity to normal tissues (40–42). This approach may enhance the antitumor efficacy of serine deprivation therapy and provide new insights and technical support for metabolism-based antitumor research.

Therefore, this review aims to summarize a comprehensive overview of tumor cell dependence on serine metabolism and its primary sources. After evaluating the therapeutic potential and limitations of serine-deprivation strategies in cancer treatment, the findings could guide the development of a nanodelivery-based approach for more targeted, effective, and safer antitumor treatments.

2 Sources of serine

The high metabolic demand for serine makes tumor cells dependent on extracellular serine uptake and on de novo production via the SSP (26, 27). Serine acquisition in the human body primarily occurs through the following pathways (1): uptake of extracellular serine via amino acid transporters such as SLC1A4 (43, 44), and (2) conversion of glycine to serine by SHMT1/2, facilitated by the glycine cleavage system (45). Although serine and glycine are interconvertible, extracellular glycine cannot substitute for serine in supporting tumor cell proliferation because the reverse conversion of glycine to serine consumes one-carbon units (45). Additionally, tumor cells can synthesize serine via the SSP, a key route for endogenous serine biosynthesis (34, 46). Studies show that over 80% of intracellular serine in tumor cells is produced through the SSP. Inhibition of the SSP impairs tumor cell proliferation, even in the presence of abundant extracellular serine or glycine (47). For example, in human breast cancer cells with PHGDH gene amplification, PHGDH knockout significantly reduced cell proliferation, an effect not rescued by excess serine supplementation in the culture medium (48, 49). Hence, the SSP is essential for tumor cell proliferation and survival.

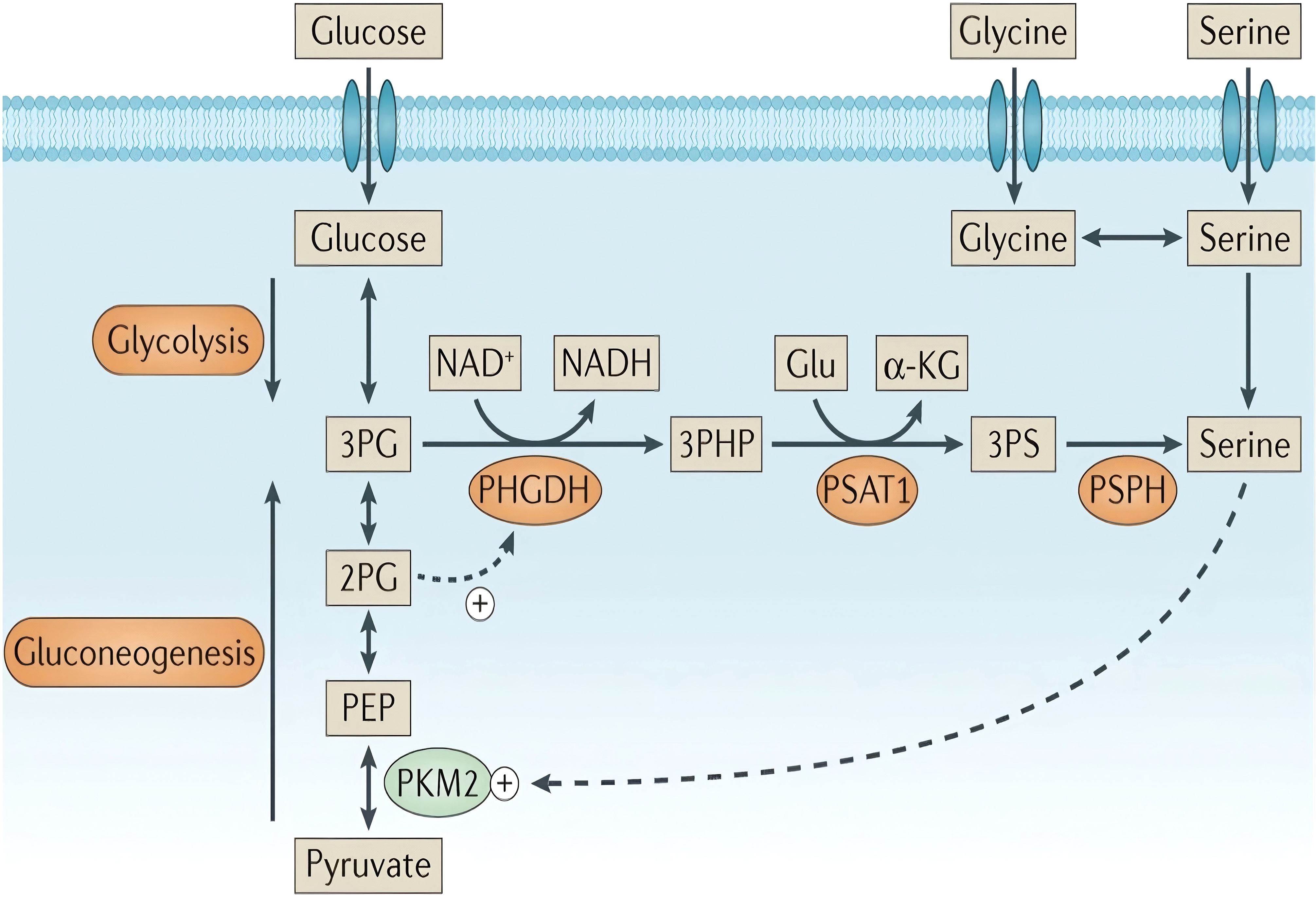

In tumor cells, serine and glycine are obtained either through uptake by neutral amino acid transporters or de novo synthesis through the SSP. The de novo SSP, a key glycolytic branch exemplifying the Warburg effect (i.e., high glycolytic flux), is catalyzed by three enzymes (Figure 1, highlighted by an orange-yellow oval). In the first step, PHGDH catalyzes the oxidation of the glycolytic intermediate 3-PG to 3-phosphohydroxypyruvate (3-PHP), concurrently reducing NAD+ to NADH, and functions as the rate-limiting enzyme of the pathway. Additionally, 2-phosphoglycerate (2-PG) activates PHGDH (Figure 1, dashed line). Subsequently, phosphoserine aminotransferase (PSAT1) catalyzes the transamination of 3-PHP and glutamic acid to form 3-phosphoserine (3-PS) and α-ketoglutarate (α-KG). Finally, phosphoserine phosphatase (PSPH) dephosphorylates 3-PS to produce serine (50–52). Under serine-deprived conditions, reduced pyruvate kinase M2 activity redirects 3-PG flux into the SSP, promoting its compensatory activation.

Figure 1. Serine synthesis pathway. “+” denotes activation, while dashed arrows indicate allosteric regulation. Copyright 2016, Springer Nature. α-KG, α-ketoglutarate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate.

In response to limited exogenous serine availability, tumor cells undergo metabolic reprogramming to upregulate the endogenous SSP, sustaining their survival and proliferation (38). During this adaptive response, the tumor suppressor gene p53 promotes de novo serine biosynthesis by transcriptionally activating key SSP enzymes (53). In melanoma (54) and breast cancer (55), PHGDH gene copy number is significantly increased, supporting the notion that tumor cells upregulate endogenous SSP activity in response to metabolic stress.

3 Key metabolic networks of serine

3.1 Serine and central carbon metabolism

The de novo SSP and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle share key intermediate metabolites, positioning serine metabolism as a central hub for tumor cell energy production and biosynthesis (Figure 2). SSP-derived α-KG serves as an anaplerotic substrate for the TCA cycle (55–57). Within the TCA cycle, α-KG is converted to oxaloacetate through sequential reactions, which then condense with acetyl-CoA to form citrate (Figure 2, mitochondrial TCA cycle). After cytosolic export, citrate is sequentially converted to acetyl-CoA by ATP-citrate lyase (ACLY), linking mitochondrial metabolism to the cytosolic de novo fatty acid synthesis pathway (58) (Figure 2, left-hand compartment of the cytosol). Furthermore, α-KG serves as an amino group acceptor for synthesizing nonessential amino acids, including glutamate, proline, and arginine. Therefore, serine metabolism is closely linked to the tumor cell biomass production and energy metabolism. Active SSP consumes substantial amounts of glutamate/glutamine, potentially competing with α-KG-producing other pathways, such as glutamate dehydrogenase. To maintain the TCA cycle, tumor cells often replenish α-KG via glutaminolysis. This indicates tumor metabolic plasticity: upregulated SSP drives enhanced glutamine metabolism, a phenomenon termed “glutamine addiction” (57).

Figure 2. Overview of serine metabolism. Serine metabolism is closely linked to one-carbon metabolism, including the folate and methionine cycles, supporting the de novo synthesis of nucleic acid precursors (purines and pyrimidines), redox regulators (NADPH and GSH), and the methylation donor SAM. These metabolites are essential for cell proliferation, survival, differentiation, and epigenetic regulation. Copyright 2024, Springer Nature. SAM, S-adenosylmethionine.

3.2 Serine and one-carbon metabolism

Serine is the primary donor of one-carbon units and is essential for intracellular one-carbon metabolism. Cytosolic-synthesized serine is transported into the mitochondrial matrix by the mitochondrial transporter Sideroflexin 1 (SFXN1) (59). SFXN1 localizes to the inner mitochondrial membrane, with its N-terminus in the matrix and C-terminus in the intermembrane space. Upon entering the intermembrane space, serine is specifically recognized and bound by SFXN1 and transported into the mitochondrial matrix, initiating one-carbon metabolism (59). SFXN1 drives malignant tumor progression via canonical (metabolic) and noncanonical (non-metabolic) pathways. SFXN1 inhibition, mimicking mitochondrial serine deprivation, exerts anti-proliferative effects on tumors similar to those of dietary serine deprivation (60). In the mitochondria, serine hydroxymethyltransferase 2 catalyzes the transfer of the hydroxymethyl group of serine to tetrahydrofolate, producing glycine and 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate (5,10-CH2-THF) (Figure 2, folate cycle) (45, 61, 62). 5,10-CH2-THF, a one-carbon unit carrier, can be enzymatically converted into other one-carbon unit forms for diverse biosynthetic processes.

5,10-CH2-THF is exported into the cytosol as formate by methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 2 and subsequently converted by methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 1 into 10-formyltetrahydrofolate (Figure 2, right cytosolic compartment). This metabolite provides essential one_carbon units for purine and thymidylate synthesis, supporting DNA replication and cellular proliferation in tumor cells (63). 5,10-CH2-THF also participates in mitochondrial tRNA formylation, a critical step for mitochondrial protein synthesis (64). Therefore, serine one-carbon metabolism is upregulated in rapidly proliferating cancer cells to satisfy the high nucleotide demand.

Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase reduces 5,10-CH2-THF to 5-methyl-THF. Subsequently, methionine synthase catalyzes the conversion of 5-methyl-THF and homocysteine to methionine (Met). Met adenosyltransferase adenosylates Met to produce the universal methyl donor S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) (45). Various methyltransferases convert SAM to S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH), releasing methyl groups in the process. Ultimately, SAH is hydrolyzed to homocysteine, thereby completing the Met cycle (Figure 2). SAM serves as the principal methyl donor in most cellular methylation reactions (RNA, DNA, and histone methylation) (65, 66). SAM and SAH expression levels regulate methylation balance, a key factor in tumor epigenetic regulation (67, 68).

Serine metabolism is crucial for maintaining intracellular redox balance in tumor cells. Intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) critically regulate cellular homeostasis and function (69). ROS exert concentration-dependent effects on cellular fate: low levels promote proliferation, moderate levels induce genomic instability and mutagenesis, and excessive levels trigger cellular senescence or apoptosis (70–72). ROS levels in tumor cells are elevated due to enhanced metabolism, upregulated cell receptor signaling, and increased oxidase activity (73, 74). In response to oxidative stress, tumor cells initiate a self-protective program by upregulating the serine metabolism pathway to produce reducing equivalents, limiting ROS accumulation and supporting cell survival and proliferation (75). During serine metabolism, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) is reduced to nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH), and serine catabolism via the folate cycle generates GSH, a key intracellular antioxidant (75, 76).

Serine metabolism intersects central carbon and one-carbon pathways, contributing to diverse complex cellular biochemical reactions. The high metabolic activity of tumor cells drives elevated nutrient demand. Serine supplementation promotes tumor cell growth, proliferation, and metastasis. Therefore, given the metabolic dependency of tumor cells on serine, targeted interventions on serine metabolism—such as dietary restriction or pharmacological inhibition of serine synthesis—offer a promising anticancer strategy. Nevertheless, safe and effective therapeutic targeting of serine metabolism remains a major challenge.

4 Potential and challenges of serine deprivation therapy

4.1 Dietary serine restriction

Serine is essential for tumor growth, prompting the development of novel anticancer therapies that restrict its uptake or metabolism in tumor cells (34, 77). Dietary serine restriction is a direct strategy to reduce its bioavailability to tumor cells. Since serine and glycine are interconvertible, a serine- and glycine-free diet (-SG diet) is typically used to restrict both amino acids simultaneously. This diet markedly inhibits the proliferation of the serine-dependent colorectal cancer (CRC) cell line HCT116 in vitro and significantly reduces tumor burden in mouse models of intestinal cancer (Apc inactivation-driven) and lymphomas (Myc activation-driven) in vivo (78). Scott et al. further report that an -SG diet inhibits the growth of glioblastoma in vitro and in vivo, prolonging survival in tumor-bearing mice with good tolerability. Additionally, that serine deprivation synergizes with radiotherapy to enhance therapeutic efficacy in vivo. Based on these findings, a clinical trial is being designed to assess its clinical translational potential (79).

In addition to directly suppressing tumors, the serine deficient (Ser Def) diet or -SG diet also enhances antitumor immunity (37, 77, 80, 81). Saha et al. report that serine depletion in CRC cells induces mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to cytosolic accumulation of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). Cytosolic mtDNA is detected by cGAS, activating the innate immune cGAS–STING pathway in vitro and enhancing antitumor immune infiltration in vivo. The Ser Def diet also reprograms the tumor immune microenvironment from an “immunosuppressive” to an “immune-supportive” state, thereby restricting tumor growth (81). The -SG diet enhances antitumor immunity in vivo by promoting the infiltration and accumulation of cytotoxic T cells (particularly CD8+ T cells) in tumor tissues, thereby suppressing CRC cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo. However, the -SG diet enhances glycolysis and increases lactate accumulation, leading to programmed death-ligand 1 lactylation and promoting immune evasion. Consequently, combining the -SG diet with anti-PD-1 antibodies effectively blocks this immune evasion and produces synergistic antitumor effects in vivo (77). Their single-arm, phase I trial (ChiCTR2300067929) shows that the -SG diet is feasible and safe for modulating systemic immunity, indicating its potential as a combination strategy (77).

Furthermore, SFXN1 mediates serine transport from the cytosol into the mitochondrial matrix and its inhibition mimics serine deprivation at the organelle level, activating a novel innate immune mechanism (59, 60, 82). Li et al. report that SFXN1 knockdown significantly reduced cell proliferation and migration in vitro, potentially by inhibiting ERK phosphorylation and CCL20 expression; in vivo, targeting SFXN1 decreased Tregs infiltration and suppressed tumor growth (60). Beyond its classical role in one-carbon metabolism, Zhang et al. report a novel pathway through which SFXN1 promotes bladder cancer metastasis through the suppression of PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1)-dependent mitophagy. SFXN1 knockout disrupts this pathway and markedly suppresses proliferation and metastasis in vitro and in vivo (82). The -SG diet also significantly increases cancer cell sensitivity to radiotherapy in vitro and in vivo (83). These studies provide strong preclinical evidence for the antitumor efficacy and immunomodulatory mechanisms of serine deprivation, highlighting its therapeutic potential.

Nonetheless, implementing dietary serine restriction in clinical settings remains challenging due to various practical limitations. Dietary serine restriction may adversely affect certain normal tissues. Pranzini et al. show that dietary serine deprivation reduces fibers width and inhibits AKT-mTORC1 signaling in vitro (Figure 3A), resulting in impaired protein synthesis, enhanced protein degradation, and upregulation of the muscle atrophy-associated genes Atrogin1 and MuRF1 in vitro (Figure 3B), thereby contributing to cancer-associated weight loss and muscle wasting in vivo (84). Epidemiological evidence shows a nonlinear inverse association between dietary serine intake and cognitive performance (P = 0.014; Figure 3C), suggesting that serine restriction may impair cognitive function in patients with cancer (85). During early pathogen infection in vivo, genes of the serine-glycine-one-carbon (SGOC) metabolic network are coordinately upregulated in CD8+ T cells to support the biosynthetic demands of their rapid proliferation. Among these, Shmt1 and Shmt2 are the most strongly upregulated genes (Figure 3D) (37). Moreover, the limited clinical efficacy of dietary serine restriction is primarily attributed to the compensatory activation of the endogenous SSP following exogenous serine deprivation (Figure 3E) (34, 52). The upregulation of SSP-associated genes promotes CRC cell proliferation and induces resistance to 5-fluorouracil in vitro and in vivo (38).

Figure 3. Potential adverse effects of dietary serine restriction on normal tissues. (A) Representative microscopic pictures of C2C12 myotubes. Copyright 2024, Springer Nature. (B) Dietary serine restriction increases the expression of muscle atrophy-associated genes Atrogin1 and MuRF1. Copyright 2024, Springer Nature. (C) SDST results show a downhill-shaped nonlinear relationship between serine intake and cognitive performance (P = 0.014). Copyright 2024, Royal Society of Chemistry. (D) Temporal expression patterns of SGOC metabolism-related genes in CD8+ T cells during the immune response to LmOVA infection. The heatmap illustrates relative expression levels of SGOC-related genes across various subsets of CD8+ OT-I T cells from the IMMGEN database, including naive, early effector (days 0.5, 1, 2, and 6), late effector (days 8, 10, and 15), and memory (days 45 and 100) T cells. Copyright 2017, Elsevier. (E) Dietary serine deprivation activates the SSP and enhances endogenous serine production. Copyright 2021, Cell Press. SDST, Symbol-Digit Substitution Test; SGOC, serine, glycine, one-carbon; SSP, serine synthesis pathway; IMMGEN, Immunological Genome Project.

While dietary serine restriction shows significant efficacy in preclinical studies, therapeutic strategies targeting this pathway must carefully balance anticancer benefits with the potential adverse effects on normal tissues. Because more than 80% of intracellular serine in tumor cells originates from the SSP, direct inhibition of its key enzymes may offer greater therapeutic efficacy than that of dietary restriction alone. Consequently, dietary serine restriction is more likely to function as an adjuvant or complementary approach within combination therapies.

4.2 Targeting key enzymes in the serine synthesis pathway to restrict serine biosynthesis

4.2.1 Inhibition of PHGDH

Emerging evidence demonstrates that the expression levels of key enzymes in the SSP are strongly associated with patient prognosis across multiple cancers. PHGDH, the rate-limiting enzyme in this pathway (86), is overexpressed and drives tumor proliferation, invasion, and therapeutic resistance in various malignancies. In gliomas, PHGDH interacts with the oncogenic transcription factor FOXM1 to promote glioma cell proliferation and invasion (87). In pancreatic cancer, PHGDH expression is significantly upregulated and correlates strongly with tumor size, lymph node metastasis, and clinical stage; furthermore, it serves as an independent prognostic biomarker in affected patients (88, 89). In gastric cancer, PHGDH is significantly overexpressed in multidrug-resistant cells and facilitates resistance development through activation of the PHGDH/IGF2BP1-TCF7L2 axis. Elevated PHGDH expression is strongly associated with poor clinical outcomes in patients with gastric cancer (90). Genetic knockout or site-specific mutation of the PHGDH gene markedly inhibits tumor cell proliferation, underscoring its potential as a therapeutic target in cancer treatment (35, 91). In cervical cancer cells, PHGDH knockout downregulates Bcl-2 expression while upregulating cleaved caspase-3 levels in vitro, thereby promoting tumor cell apoptosis in vivo (92). Moreover, PHGDH facilitates pancreatic cancer progression in vivo by enhancing translation initiation through interactions with eIF4A1 and eIF4E, whereas its downregulation significantly suppresses tumor growth and prolongs overall survival (93).

Recent preclinical studies have evaluated several small-molecule PHGDH inhibitors, demonstrating robust antitumor activity and highlighting their potential as therapeutic agents (94, 95). Spillier et al. report that the anti-alcoholism drug disulfiram inhibits PHGDH enzymatic activity by promoting the conversion of its active tetrameric form into an inactive dimer in vitro, thereby exerting significant anticancer effects (96). PHGDH overexpression induces resistance to erlotinib in tumor xenograft mouse models, whereas treatment with the PHGDH inhibitor NCT-503 effectively restores erlotinib sensitivity in vitro and in vivo (97). Additionally, compared with monotherapy, the combination of a PHGDH inhibitor with gemcitabine or cisplatin produces synergistic antitumor effects in vitro and in vivo (98). Beyond its canonical roles, emerging evidence shows noncanonical functions of serine metabolism in driving tumor metastasis. In the cytosol, Soflea et al. demonstrate that purine depletion significant upregulates SSP genes, leading to the accumulation of the intermediate metabolite 3-PS. This metabolite enhances cell migration in vitro and in vivo, an effect that can be effectively blocked by PHGDH inhibition (99).

Targeting serine metabolism, particularly via PHGDH inhibition, not only suppresses tumor growth through nutrient deprivation but also crucially blocks compensatory pro-metastatic adaptations mediated by the SSP that can be triggered by other therapies, such as chemotherapy. By disrupting these stress-induced adaptive pathways in tumors, PHGDH and SFXN1 inhibitors may offer more comprehensive and durable therapeutic efficacy when combined with conventional treatments. However, despite promising preclinical evidence, no PHGDH inhibitor has yet progressed to clinical trials.

4.2.2 Inhibition of PSATl

Overexpression of PSAT1–the second key enzyme in the SSP–is implicated in the progression of various malignant tumors (100–108). Elevated PSAT1 expression markedly enhances cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, and is strongly correlated with poor patient prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (102, 103). Similarly, in breast cancer, PSAT1 overexpression promotes these malignant phenotypes (including enhanced proliferative, migratory, and invasive capacities) and is associated with reduced overall survival (107, 108). Collectively, preclinical studies across multiple cancers demonstrate the therapeutic potential of targeting PSAT1 as an antitumor strategy. Ye et al. demonstrate that PSAT1 knockdown effectively suppresses the proliferation, migration, and invasion of clear cell renal cell carcinoma cells while promoting apoptosis, as confirmed in vitro and in vivo (104). Furthermore, in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and lung adenocarcinoma, PSAT1 silencing not only inhibits tumor growth but also acts synergistically with serine deprivation or erlotinib treatment, respectively, to overcome drug resistance in vitro and in vivo (109, 110).

Although pharmacological inhibition of PSAT1 holds significant promise as an anticancer strategy, the development of PSAT1-specific inhibitors remains in its early stages. Through computational simulations, Zhang et al. predicted that coniferin and tetrahydrocurcumin exhibit strong binding affinities to PSAT1, suggesting their potential as candidate inhibitors. However, these predictions require further validation through in vitro and in vivo experiments (111). Therefore, future studies should accelerate the identification of PSAT1 inhibitors and their clinical translation by integrating computational technologies (including virtual screening, molecular docking, and simulations) with systematic experimental validation.

4.2.3 Inhibition of PSPH

Inhibition of PSPH, the terminal enzyme in the SSP, effectively suppresses key malignant phenotypes in cancer. PSPH induces autophagy in HCC cells via the AMPK/mTOR/ULK1 signaling pathway, thereby inhibiting apoptosis, while enhancing proliferation and invasion, which collectively accelerate HCC progression (112). Moreover, PSPH suppresses the accumulation of 2-hydroxyglutarate, leading to the activation of proto-oncogene expression and facilitating melanoma growth and metastasis (113). A study also reports that PSPH overexpression in NSCLC tissues is strongly correlated with advanced clinical stages and increased metastatic potential. Knockdown of PSPH significantly suppresses the invasive and migratory abilities of NSCLC cells in vitro (114). Currently, PSPH inhibitors remain in the preclinical research phase, with no candidate having advanced clinical trials. Emerging evidence suggests that PSPH knockdown increases tumor cell sensitivity to PD-1 inhibitors. Metformin-mediated PSPH suppression mimics this immunostimulatory effect and acts synergistically with PD-1 targeted therapy (115). Collectively, these findings support PSPH as a promising and druggable therapeutic target in cancer treatment.

In summary, serine deprivation therapy—encompassing dietary restriction and inhibition of the SSP—represents a promising yet underdeveloped strategy in cancer therapeutics. However, its clinical translation has been significantly limited by two major bottlenecks: off-target toxicity and compensatory metabolic adaptations. Therefore, future progress will depend on overcoming these challenges through the development of highly selective inhibitors coupled with precision delivery strategies.

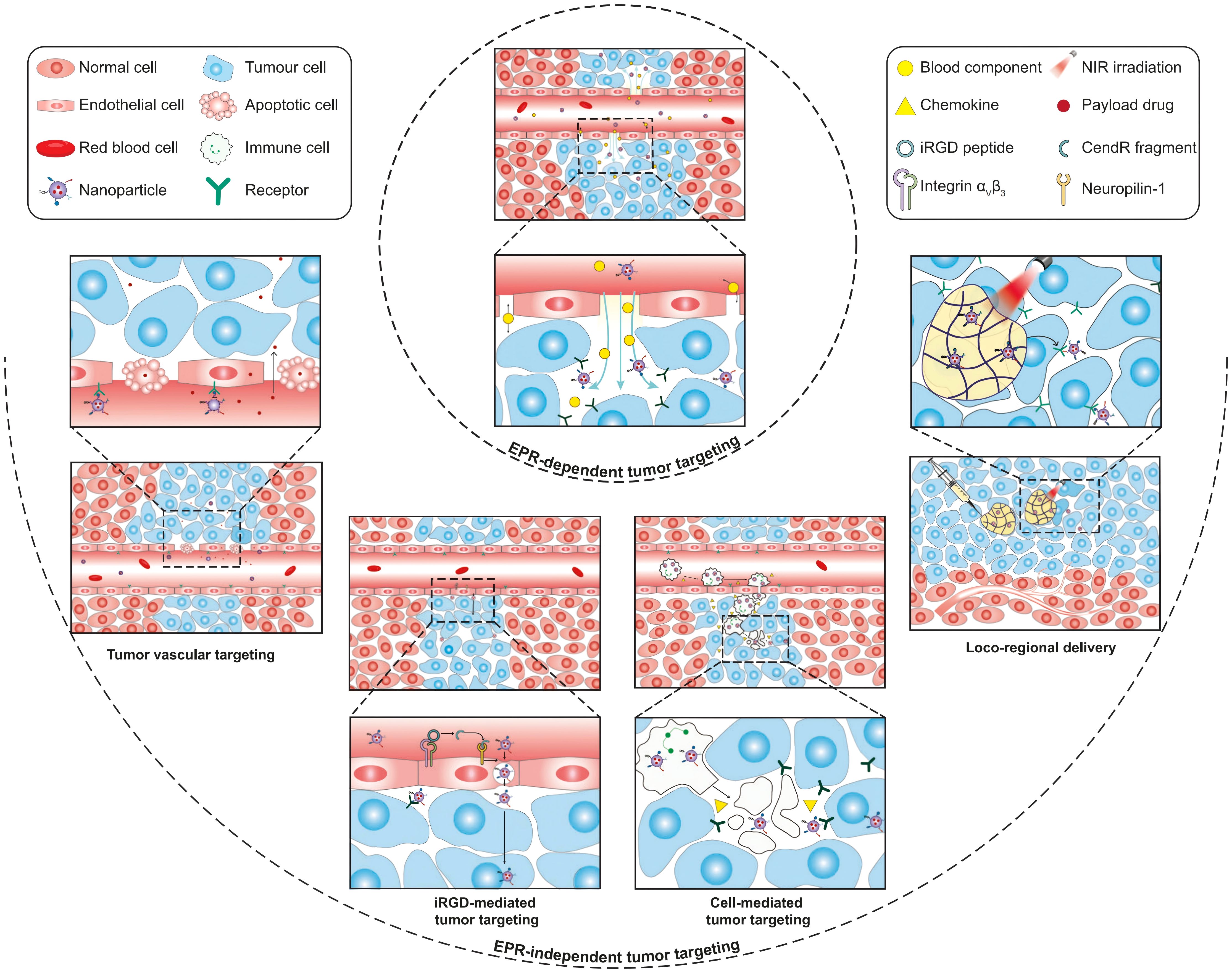

5 Nanodelivery systems for serine deprivation

Research on SSP inhibition has primarily focused on PHGDH-targeting compounds, including NCT-503 (116), CBR-5884 (117), and WQ-2101 (118). However, these inhibitors generally exhibit poor aqueous solubility and insufficient target specificity, limiting their therapeutic potential. Nanodelivery systems offer a promising strategy to address these pharmacological challenges (119, 120). Encapsulating hydrophobic drugs within nanocarriers not only enhances their solubility and stability but also facilitates tumor-specific delivery through passive targeting (e.g., the enhanced permeability and retention [EPR] effect) (121, 122) and active targeting strategies (e.g., ligand modification) (123–125). To address the substantial heterogeneity of the EPR effect, several EPR-independent tumor-targeting strategies have been proposed, including tumor vascular targeting, cell-mediated tumor delivery, iRGD-mediated tumor targeting, and locoregional administration (125) (Figure 4). These approaches collectively enhance therapeutic efficacy while reducing systemic toxicity.

Figure 4. Schematic illustration of EPR-dependent and EPR-independent strategies for nanoparticle delivery to tumors. Copyright 2023, Springer Nature. EPR, enhanced permeability and retention.

5.1 Passive targeting and active targeting strategies of nanodelivery systems

At present, research on the nanodelivery systems utilizing passive targeting for the delivery of PHGDH inhibitors in tumor treatment remains limited, though recent studies report preliminary validation. Ma et al. developed a nanoparticle formulation, NCT-503@Cu-HMPB, with Figure 5A schematically illustrating its synthesis process. This nanoformulation undergoes acid-triggered degradation within the acidic tumor microenvironment, leading to the simultaneous release of Cu2+ and NCT-503, thereby inducing pH-responsive cuproptosis and inhibiting serine metabolism, as depicted in the mechanistic illustration (Figure 5B). In vivo fluorescence imaging revealed strong Cy5.5 fluorescence signals localized at the tumor site, demonstrating the effective tumor-targeted accumulation of Cu-HMPB mediated by the EPR effect (Figure 5C). Consequently, treatment with this nanoparticle markedly suppresses tumor growth (Figure 5D) without inducing evident toxicity in major normal organs in vivo (Figure 5F) (126). Additionally, transcriptomic analysis in vivo (Figure 5E) confirms that NCT-503@Cu-HMPB simultaneously activates cuproptosis and apoptosis pathways while inhibiting serine synthesis-mediated proliferation, highlighting its potential as a dual-action anticancer therapy (126).

Figure 5. Antitumor effects of NCT-503@Cu-HMPB through induction of cuproptosis and inhibition of serine metabolism. (A) Schematic diagram of the synthesis process of NCT-503@Cu-HMPB. (B) Schematic diagram of the antitumor mechanism of NCT-503@Cu-HMPB via the induction of cuproptosis and inhibition of serine metabolism. (C) In vivo fluorescence colocalization imaging of Cu-HMPB labeled with Cy5.5 in 4T1-lucia tumor-bearing mice. (D) Tumor growth curves of 4T1 xenografts in nude mice. (E) Heatmap showing differentially expressed genes involved in the cuproptosis and apoptosis pathways between the nanomedicine-treated and control groups. (F) H&E staining of major organs from BALB/c mice treated with NCT-503@Cu-HMPB or untreated, assessed on days 1, 7, and 28. Copyright 2025, Wiley. H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

Currently, research on active targeting-based nanodelivery of PHGDH inhibitors for tumor treatment remains limited. Nevertheless, active targeting strategies developed for other therapeutic agents provide valuable insights for designing future PHGDH inhibitor delivery systems (127, 128). For instance, Han et al. conjugated cRGD peptides to the surface of Ag2S nanoparticles through amide bonding, thereby enhancing the tumor-targeting capability of the nanocarrier, significantly improving antitumor efficacy, and minimizing off-target toxicity in nontumor tissues in vivo (129). Similarly, Ren et al. developed nanoassemblies named MC@RL/Apt, composed of a red blood cell-liposome hybrid membrane-camouflaged Mn–Ce6 nanocomplex. In vitro studies show that MC@RL/Apt functions as an efferocytosis inhibitor by suppressing macrophage phagocytosis of apoptotic cells and promoting macrophage polarization toward the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype. Consequently, treatment with MC@RL/Apt effectively suppresses tumor growth and elicits robust antitumor immune responses in vivo (130). This study not only highlights the advantages of nanocarriers in drug protection and targeted delivery but also demonstrates that active targeting strategies can precisely modulate the TIME. Collectively, these findings validate the efficacy of passive and active targeting approaches in nanoscale delivery systems in vitro and in vivo, providing valuable guidance for the rational design of nanocarriers to deliver PHGDH inhibitors.

5.2 Nano-based co-delivery system

However, nanomaterial-based delivery strategies for PHGDH inhibitors face challenges in completely depleting all sources of serine within tumors, as tumor cells can still import exogenous serine to partially sustain their growth (33). Montrose et al. report that in colon cancer models, combining the Ser Def diet (which restricts exogenous supply) with PSAT1 knockout (which blocks endogenous synthesis) results in greater tumor growth suppression in vitro and in vivo than that of either intervention alone (105). This finding indicates that the concurrent inhibition of exogenous and endogenous serine sources in tumor cells significantly enhances antitumor efficacy, offering a promising therapeutic strategy (105, 131). GPNA and V-9302 act as competitive inhibitors of the ASCT2 transporter by binding to its substrate-binding site, thereby blocking serine uptake and depleting tumor cells of exogenous serine (132).

While the co-delivery of PHGDH and ASCT2 inhibitors remains unreported, studies demonstrate the potential of nanocarrier-based co-delivery systems to achieve synergistic therapeutic effects through the simultaneous transport of multiple agents. For example, Yu et al. developed a polymeric nanosystem for the co-delivery of resiquimod (R848) and rifapentine, which synergistically reprograms macrophages and enhances intracellular antibacterial activity in bacterial infection models, achieving significantly higher efficacy than that of monotherapy in vitro and in vivo (133). Similarly, Sun et al. constructed a cyclodextrin-based nanoparticle for the co-delivery of ginsenoside Rg3 and quercetin, which effectively suppresses tumor growth and remodels the tumor microenvironment, demonstrating strong chemo-immunotherapeutic synergy in a CRC model in vitro and in vivo (134). Collectively, these studies establish a solid technical foundation for developing nanocarrier-based co-delivery strategies. Building on this foundation, the co-delivery of PHGDH and ASCT2 inhibitors using nanodelivery systems may enable the comprehensive blockade of exogenous and endogenous serine sources within tumors while leveraging nanosystem-targeting strategies to promote drug accumulation at tumor sites. This strategy is expected to enhance antitumor efficacy, and reduce adverse effects on nontumor tissues.

In summary, nanosystem-based strategies encompassing targeted delivery and co-delivery approaches hold considerable potential to improve the therapeutic efficacy of PHGDH inhibitors. However, research specifically addressing the nanodelivery of PHGDH inhibitors remains limited, as most existing studies focus on nanodelivery systems for other therapeutic agents. The feasibility, synergistic interactions, and safety profiles of such approaches require further extensive preclinical validation. Therefore, continued in-depth research is warranted to overcome these challenges and accelerate clinical advancement.

6 Summary and outlook

In conclusion, the metabolic reliance of tumor cells on serine metabolism constitutes a key therapeutic vulnerability for targeted cancer treatment. The SSP is primarily regulated by three rate-limiting enzymes: PHGDH, PSAT1, and PSPH. Current research predominantly focuses on developing PHGDH inhibitors; however, no PHGDH inhibitor has received clinical approval from the FDA. In contrast, research on inhibitors targeting PSAT1 and PSPH remains underdeveloped, with only limited progress in drug discovery efforts. The off-target distribution of PHGDH inhibitors may induce adverse effects in nontumor tissues, but nanoparticle-based delivery systems offer a promising strategy to address this challenge. The co-delivery of PHGDH and ASCT2 inhibitors using nanoparticle-based delivery systems represents a highly promising direction for future cancer therapy research. However, the feasibility, synergistic efficacy, and safety profile of this strategy require systematic preclinical validation. Therefore, future studies should focus on developing selective inhibitors targeting PHGDH, PSAT1, PSPH, and ASCT2, while optimizing nanoparticle-based delivery systems to enhance delivery efficiency. In addition, further exploration of combination therapeutic strategies is warranted to facilitate the clinical translation and broader application of serine metabolism-targeted therapies.

Author contributions

HL: Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YL: Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

PHGDH, phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase; SSP, serine synthesis pathway; 3-PG, 3-phosphoglycerate; 3-PHP, 3-phosphohydroxypyruvate; 2-PG, 2-phosphoglycerate; PSAT1, phosphoserine aminotransferase; α-KG, α-ketoglutarate; PSPH, phosphoserine phosphatase; 3-PS, 3-phosphoserine; TCA, tricarboxylic acid; ACLY, ATP-citrate lyase; SFXN1, Sideroflexin 1; 5,10-CH2-THF, 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate; SAM, S-adenosylmethionine; SAH, S-adenosylhomocysteine; ROS, reactive oxygen species; NAD+, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; NADH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; CRC, colorectal cancer; -SG, serine- and glycine-free diet; mtDNA, mitochondrial DNA; PINK1, PTEN-induced kinase 1; SGOC, serine-glycine-one-carbon; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; EPR, enhanced permeability and retention.

References

1. Do LK, Lee HM, Ha YS, Lee CH, and Kim J. Amino acids in cancer: Understanding metabolic plasticity and divergence for better therapeutic approaches. Cell Rep. (2025) 44:115529. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2025.115529

2. Zhang LY, Zhao JN, Su CYY, Wu JX, Jiang L, Chi H, et al. Organoid models of ovarian cancer: resolving immune mechanisms of metabolic reprogramming and drug resistance. Front Immunol. (2025) 16:1573686. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1573686

3. Xia LZ, Oyang LD, Lin JG, Tan SM, Han YQ, Wu NY, et al. The cancer metabolic reprogramming and immune response. Mol Can. (2021) 20:28. doi: 10.1186/s12943-021-01316-8

4. Gore M, Kabekkodu SP, and Chakrabarty S. Exploring the metabolic alterations in cervical cancer induced by HPV oncoproteins: From mechanisms to therapeutic targets. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Can. (2025) 1880:189292. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2025.189292

5. Altea-Manzano P, Decker-Farrell A, Janowitz T, and Erez A. Metabolic interplays between the tumour and the host shape the tumour macroenvironment. Nat Rev Can. (2025) 25:274–92. doi: 10.1038/s41568-024-00786-4

6. Mossmann D, Müller C, Park S, Ryback B, Colombi M, Ritter N, et al. Arginine reprograms metabolism in liver cancer via RBM39. Cell. (2023) 186:5068–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.09.011

7. Koundouros N and Poulogiannis G. Reprogramming of fatty acid metabolism in cancer. Br J Can. (2020) 122:4–22. doi: 10.1038/s41416-019-0650-z

8. Xu XM, Peng Q, Jiang XJ, Tan SM, Yang YQ, Yang WJ, et al. Metabolic reprogramming and epigenetic modifications in cancer: from the impacts and mechanisms to the treatment potential. Exp Mol Med. (2023) 55:1357–70. doi: 10.1038/s12276-023-01020-1

9. Huang D, Cai H, and Huang HY. Serine metabolism in tumor progression and immunotherapy. Discov Oncol. (2025) 16:628. doi: 10.1007/s12672-025-02358-w

10. Li ZZ, Sun CJ, and Qin ZH. Metabolic reprogramming of cancer-associated fibroblasts and its effect on cancer cell reprogramming. Theranostics. (2021) 11:8322–36. doi: 10.7150/thno.62378

11. Vaupel P, Schmidberger H, and Mayer A. The Warburg effect: essential part of metabolic reprogramming and central contributor to cancer progression. Int J Radiat Biol. (2019) 95:912–9. doi: 10.1080/09553002.2019.1589653

12. Yang K, Wang XK, Song CH, He Z, Wang RX, Xu YR, et al. The role of lipid metabolic reprogramming in tumor microenvironment. Theranostics. (2023) 13:1774–808. doi: 10.7150/thno.82920

13. Pranzini E, Pardella E, Paoli P, Fendt SM, and Taddei ML. Metabolic reprogramming in anticancer drug resistance: A focus on amino acids. Trends Can. (2021) 7:682–99. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2021.02.004

14. Wang ZH, Wu XY, Chen HN, and Wang K. Amino acid metabolic reprogramming in tumor metastatic colonization. Front Oncol. (2023) 13:1123192. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1123192

15. Wang WM and Zou WP. Amino acids and their transporters in T cell immunity and cancer therapy. Mol Cell. (2020) 80:384–95. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.09.006

16. Wei Z, Liu XY, Cheng CM, Yu W, and Yi P. Metabolism of amino acids in cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol. (2021) 8:603837. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.603837

17. Liu XH, Ren B, Ren J, Gu MZ, You L, and Zhao YP. The significant role of amino acid metabolic reprogramming in cancer. Cell Commun Signal. (2024) 22:380. doi: 10.1186/s12964-024-01760-1

18. Wang JT, Wang W, Zhu F, and Duan QH. The role of branched chain amino acids metabolic disorders in tumorigenesis and progression. BioMed Pharmacother. (2022) :153:113390. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113390

19. Zhang JR, Chen MJ, Yang YX, Liu ZQ, Guo WN, Xiang PJ, et al. Amino acid metabolic reprogramming in the tumor microenvironment and its implication for cancer therapy. J Cell Physiol. (2024) 239:e31349. doi: 10.1002/jcp.31349

20. Wang D and Wan X. Progress in research on the role of amino acid metabolic reprogramming in tumour therapy: A review. BioMed Pharmacother. (2022) 156:113923. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113923

21. Li ZY and Zhang HF. Reprogramming of glucose, fatty acid and amino acid metabolism for cancer progression. Cell Mol Life Sci. (2016) 73:377–92. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-2070-4

22. Butler M, van der Meer LT, and van Leeuwen FN. Amino acid depletion therapies: starving cancer cells to death. Trends Endocrinol Metab. (2021) 32:367–81. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2021.03.003

23. Sun LH, Suo CX, Li ST, Zhang HF, and Gao P. Metabolic reprogramming for cancer cells and their microenvironment: Beyond the Warburg Effect. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Can. (2018) 1870:51–66. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2018.06.005

24. Liu YW, Zong XY, Altea-Manzano P, and Fu J. Amino acid metabolism in breast cancer: Pathogenic drivers and therapeutic opportunities. Protein Cell. (2025) 16:506–31. doi: 10.1093/procel/pwaf011

25. Tombari C, Zannini A, Bertolio R, Pedretti S, Audano M, Triboli L, et al. Mutant p53 sustains serine-glycine synthesis and essential amino acids intake promoting breast cancer growth. Nat Commun. (2023) 14:6777. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-42458-1

26. Wang SX, Yuan XX, Song GB, Yang L, Jin JY, and Liu WQ. Serine metabolic reprogramming in tumorigenesis, tumor immunity, and clinical treatment. Adv Nutr. (2023) 14:1050–66. doi: 10.1016/j.advnut.2023.05.007

27. Zhang J, Bai J, Gong C, Wang J, Cheng Y, Zhao J, et al. Serine-associated one-carbon metabolic reprogramming: a new anti-cancer therapeutic strategy. Front Oncol. (2023) 13:1184626. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1184626

28. Wang YQ, Wu H, and Hu X. Quantification of the inputs and outputs of serine and glycine metabolism in cancer cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. (2025) 768:110367. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2025.110367

29. Petrova B, Maynard AG, Wang P, and Kanarek N. Regulatory mechanisms of one-carbon metabolism enzymes. J Biol Chem. (2023) 299:105457. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2023.105457

30. Li AM and Ye J. Reprogramming of serine, glycine and one-carbon metabolism in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. (2020) 1866:165841. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2020.165841

31. Liu XJ, Liu BX, Wang JW, Liu HB, Wu JS, Qi YW, et al. PHGDH activation fuels glioblastoma progression and radioresistance via serine synthesis pathway. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. (2025) 44:99. doi: 10.1186/s13046-025-03361-3

32. Luo L, Wu XY, Fan JW, Dong LX, Wang M, Zeng Y, et al. FBXO7 ubiquitinates PRMT1 to suppress serine synthesis and tumor growth in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Commun. (2024) 15:4790. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-49087-2

33. Conger KO, Chidley C, Ozgurses ME, Zhao HP, Kim YM, Semina SE, et al. ASCT2 is a major contributor to serine uptake in cancer cells. Cell Rep. (2024) 43:114552. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2024.114552

34. Tajan M, Hennequart M, Cheung EC, Zani F, Hock AK, Legrave N, et al. Serine synthesis pathway inhibition cooperates with dietary serine and glycine limitation for cancer therapy. Nat Commun. (2021) 12:366. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20223-y

35. Wei L, Lee D, Law CT, Zhang MS, Shen J, Chin DW, et al. Genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 library screening identified PHGDH as a critical driver for Sorafenib resistance in HCC. Nat Commun. (2019) 10:4681. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12606-7

36. Baksh SC, Todorova PK, Gur-Cohen S, Hurwitz B, Ge Y, Novak JSS, et al. Extracellular serine controls epidermal stem cell fate and tumour initiation. Nat Cell Biol. (2020) 22:779–90. doi: 10.1038/s41556-020-0525-9

37. Ma EH, Bantug G, Griss T, Condotta S, Johnson RM, Samborska B, et al. Serine is an essential metabolite for effector T cell expansion. Cell Metab. (2017) 25:345–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.12.011

38. Chen ZK, Xu JC, Fang K, Jiang HY, Leng ZY, Wu H, et al. FOXC1-mediated serine metabolism reprogramming enhances colorectal cancer growth and 5-FU resistance under serine restriction. Cell Commun Signal. (2025) 23:13. doi: 10.1186/s12964-024-02016-8

39. Li JC, Lv ZZ, Guo YR, Fang J, Wang A, Feng YL, et al. Hafnium (Hf)-chelating porphyrin-decorated gold nanosensitizers for enhanced radio-radiodynamic therapy of colon carcinoma. ACS Nano. (2023) 17:25147–56. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.3c08068

40. Cheng Z, Li MY, Dey RJ, and Chen YH. Nanomaterials for cancer therapy: current progress and perspectives. J Hematol Oncol. (2021) 14:85. doi: 10.1186/s13045-021-01096-0

41. Rosenblum D, Joshi N, Tao W, Karp JM, and Peer D. Progress and challenges towards targeted delivery of cancer therapeutics. Nat Commun. (2018) 9:1410. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03705-y

42. Li XC, Liu YH, Ke JJ, Wang ZH, Han MD, Wang N, et al. Enhancing radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma: nano-epidrug effects on immune modulation and antigenicity restoration. Adv Mater. (2024) 36:e2414365. doi: 10.1002/adma.202414365

43. Elazar D, Alvarez N, Drobeck S, and Gunn TM. SLC1A4 and serine homeostasis: implications for neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders. Int J Mol Sci. (2025) 26:2104. doi: 10.3390/ijms26052104

44. Zhang SB, Huang F, Wang YS, Long YF, Li YP, Kang YL, et al. NAT10-mediated mRNA N4-acetylcytidine reprograms serine metabolism to drive leukaemogenesis and stemness in acute myeloid leukaemia. Nat Cell Biol. (2024) 26:2168–82. doi: 10.1038/s41556-024-01548-y

45. McBride MJ, Hunter CJ, Zhang ZY, TeSlaa T, Xu XC, Ducker GS, et al. Glycine homeostasis requires reverse SHMT flux. Cell Metab. (2024) 36:103–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2023.12.001

46. Chan FF, Kwan KK, Seoung DH, Chin DW, Ng IO, Wong CC, et al. N6-Methyladenosine modification activates the serine synthesis pathway to mediate therapeutic resistance in liver cancer. Mol Ther. (2024) 32:4435–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2024.10.025

47. Sowers ML, Herring J, Zhang W, Tang H, Ou Y, Gu W, et al. Analysis of glucose-derived amino acids involved in one-carbon and cancer metabolism by stable-isotope tracing gas chromatography mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. (2019) 566:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2018.10.026

48. Sullivan MR, Mattaini KR, Dennstedt EA, Nguyen AA, Sivanand S, Reilly MF, et al. Increased serine synthesis provides an advantage for tumors arising in tissues where serine levels are limiting. Cell Metab. (2019) 29:1410–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.02.015

49. Mullarky E, Lucki NC, Beheshti Zavareh R, Anglin JL, Gomes AP, Nicolay BN, et al. Identification of a small molecule inhibitor of 3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase to target serine biosynthesis in cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2016) 113:1778–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521548113

50. He LQ, Ding YQ, Zhou XH, Li TJ, and Yin YL. Serine signaling governs metabolic homeostasis and health. Trends Endocrinol Metab. (2023) 34:361–72. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2023.03.001

51. Yun HJ, Li M, Guo D, Jeon SM, Park SH, Lim JS, et al. AMPK-HIF-1α signaling enhances glucose-derived de novo serine biosynthesis to promote glioblastoma growth. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. (2023) 42:340. doi: 10.1186/s13046-023-02927-3

52. Li XY, Gracilla D, Cai L, Zhang MY, Yu XL, Chen XG, et al. ATF3 promotes the serine synthesis pathway and tumor growth under dietary serine restriction. Cell Rep. (2021) 36:109706. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109706

53. Shi TZ, Yuan ZH, He YY, Zhang DL, Chen ST, Wang XJ, et al. Competition between p53 and YY1 determines PHGDH expression and Malignancy in bladder cancer. Cell Oncol (Dordr). (2023) 46:1457–72. doi: 10.1007/s13402-023-00823-8

54. Jasani N, Xu XN, Posorske B, Kim Y, Wang KZ, Vera O, et al. PHGDH induction by MAPK is essential for melanoma formation and creates an actionable metabolic vulnerability. Cancer Res. (2025) 85:314–28. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-24-2471

55. Possemato R, Marks KM, Shaul YD, Pacold ME, Kim D, Birsoy K, et al. Functional genomics reveal that the serine synthesis pathway is essential in breast cancer. Nature. (2011) 476:346–50. doi: 10.1038/nature10350

56. Huang X, Yang X, Xiang L, and Chen Y. Serine metabolism in macrophage polarization. Inflamm Res. (2024) 73(1):83–98. doi: 10.1007/s00011-023-01815-y

57. Qiu Y, Stamatatos OT, Hu Q, Ruiter Swain J, Russo S, Sann A, et al. The unique catalytic properties of PSAT1 mediate metabolic adaptation to glutamine blockade. Nat Metab. (2024) 6:1529–48. doi: 10.1038/s42255-024-01104-w

58. Yang L, Venneti S, and Nagrath D. Glutaminolysis: a hallmark of cancer metabolism. Annu Rev BioMed Eng. (2017) 19:163–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071516-044546

59. Kory N, Wyant GA, Prakash G, Uit de Bos J, Bottanelli F, Pacold ME, et al. SFXN1 is a mitochondrial serine transporter required for one-carbon metabolism. Science. (2018) 362:eaat9528. doi: 10.1126/science.aat9528

60. Li Y, Yang W, Liu C, Zhou S, Liu X, Zhang T, et al. SFXN1-mediated immune cell infiltration and tumorigenesis in lung adenocarcinoma: a potential therapeutic target. Int Immunopharmacol. (2024) 132:111918. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2024.111918

61. Yang M and Vousden KH. Serine and one-carbon metabolism in cancer. Nat Rev Can. (2016) 16:650–62. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.81

62. Geeraerts SL, Heylen E, De Keersmaecker K, and Kampen KR. The ins and outs of serine and glycine metabolism in cancer. Nat Metab. (2021) 3:131–41. doi: 10.1038/s42255-020-00329-9

63. Ducker GS, Chen L, Morscher RJ, Ghergurovich JM, Esposito M, Teng X, et al. Reversal of cytosolic one-carbon flux compensates for loss of the mitochondrial folate pathway. Cell Metab. (2016) 23:1140–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.04.016

64. Morscher RJ, Ducker GS, Li SH, Mayer JA, Gitai Z, Sperl W, et al. Mitochondrial translation requires folate-dependent tRNA methylation. Nature. (2018) 554:128–32. doi: 10.1038/nature25460

65. Gou DM, Liu R, Shan XQ, Deng HJ, Chen C, Xiang J, et al. Gluconeogenic enzyme PCK1 supports S-adenosylmethionine biosynthesis and promotes H3K9me3 modification to suppress hepatocellular carcinoma progression. J Clin Invest. (2023) 133:e161713. doi: 10.1172/JCI161713

66. Pan SJ, Fan M, Liu ZN, Li X, and Wang HJ. Serine, glycine and one−carbon metabolism in cancer (Review). Int J Oncol. (2021) 58:158–70. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2020.5158

67. Zeng JD, Wu WKK, Wang HY, and Li XX. Serine and one-carbon metabolism, a bridge that links mTOR signaling and DNA methylation in cancer. Pharmacol Res. (2019) 149:104352. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.104352

68. Bhootra S, Jill N, Shanmugam G, Rakshit S, and Sarkar K. DNA methylation and cancer: transcriptional regulation, prognostic, and therapeutic perspective. Med Oncol. (2023) 40:71. doi: 10.1007/s12032-022-01943-1

69. Ren YQ, Wang RZ, Weng SY, Xu H, Zhang YY, Chen S, et al. Multifaceted role of redox pattern in the tumor immune microenvironment regarding autophagy and apoptosis. Mol Can. (2023) 22:130. doi: 10.1186/s12943-023-01831-w

70. Sies H, Belousov VV, Chandel NS, Davies MJ, Jones DP, Mann GE, et al. Defining roles of specific reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cell biology and physiology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2022) 23:499–515. doi: 10.1038/s41580-022-00456-z

71. Glorieux C, Liu SH, Trachootham D, and Huang P. Targeting ROS in cancer: rationale and strategies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. (2024) 23:583–606. doi: 10.1038/s41573-024-00979-4

72. Moloney JN and Cotter TG. ROS signalling in the biology of cancer. Semin Cell Dev Biol. (2018) 80:50–64. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.05.023

73. Cheung EC and Vousden KH. The role of ROS in tumour development and progression. Nat Rev Can. (2022) 22:280–97. doi: 10.1038/s41568-021-00435-0

74. Zhao W, Zhuang P, Chen Y, Wu Y, Zhong M, and Lun Y. Double-edged sword” effect of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in tumor development and carcinogenesis. Physiol Res. (2023) 72:301–7. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.935007

75. Liu X, Liu YZ, Liu Z, Lin CW, Meng FC, Xu L, et al. CircMYH9 drives colorectal cancer growth by regulating serine metabolism and redox homeostasis in a p53-dependent manner. Mol Can. (2021) 20:114. doi: 10.1186/s12943-021-01412-9

76. Fan J, Ye JB, Kamphorst JJ, Shlomi T, Thompson CB, and Rabinowitz JD. Quantitative flux analysis reveals folate-dependent NADPH production. Nature. (2014) 510:298–302. doi: 10.1038/nature13236

77. Tong H, Jiang ZD, Song LL, Tan KQ, Yin XM, He CY, et al. Dual impacts of serine/glycine-free diet in enhancing antitumor immunity and promoting evasion via PD-L1 lactylation. Cell Metab. (2024) 36:2493–510. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2024.10.019

78. Maddocks ODK, Athineos D, Cheung EC, Lee P, Zhang T, van den Broek NJF, et al. Modulating the therapeutic response of tumours to dietary serine and glycine starvation. Nature. (2017) 544:372–6. doi: 10.1038/nature22056

79. Scott AJ, Mittal A, Meghdadi B, O’Brien A, Bailleul J, Sravya P, et al. Rewiring of cortical glucose metabolism fuels human brain cancer growth. Nature. (2025) 646:413–22. doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-09460-7

80. Rodriguez AE, Ducker GS, Billingham LK, Martinez CA, Mainolfi N, and Suri V. et al, Serine metabolism supports macrophage IL-1β production. Cell Metab. (2019) 29:1003–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.01.014

81. Saha S, Ghosh M, Li J, Wen A, Galluzzi L, Martinez LA, et al. Serine depletion promotes antitumor immunity by activating mitochondrial DNA-Mediated cGAS-STING signaling. Cancer Res. (2024) 84:2645–59. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-23-1788

82. Zhang B, Dong G, Guo X, Li H, Chen W, Diao W, et al. SFXN1 promotes bladder cancer metastasis by restraining PINK1-dependent mitophagy. Oncogene. (2025) 44:2893–906. doi: 10.1038/s41388-025-03460-7

83. Falcone M, Uribe AH, Papalazarou V, Newman AC, Athineos D, Stevenson K, et al. Sensitisation of cancer cells to radiotherapy by serine and glycine starvation. Br J Can. (2022) 127:1773–86. doi: 10.1038/s41416-022-01965-6

84. Pranzini E, Muccillo L, Nesi I, Santi A, Mancini C, Lori G, et al. Limiting serine availability during tumor progression promotes muscle wasting in cancer cachexia. Cell Death Discov. (2024) 10:510. doi: 10.1038/s41420-024-02271-1

85. Chen JY, Fang SH, Cai ZM, Zhao Q, and Yang N. Dietary serine intake is associated with cognitive function among US adults. Food Funct. (2024) 15:3744–51. doi: 10.1039/D3FO04972H

86. Chen C, Zhu TY, Liu XQ, Zhu DR, Zhang Y, Wu SF, et al. Identification of a novel PHGDH covalent inhibitor by chemical proteomics and phenotypic profiling. Acta Pharm Sin B. (2022) 12:246–61. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.06.008

87. Liu JL, Guo SL, Li QZ, Yang LX, Xia ZB, Zhang LJ, et al. Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase induces glioma cells proliferation and invasion by stabilizing forkhead box M1. J Neurooncol. (2013) 111:245–55. doi: 10.1007/s11060-012-1018-x

88. Zheng MZ, Guo J, Xu JM, Yang KY, Tang RT, Gu XX, et al. Ixocarpalactone A from dietary tomatillo inhibits pancreatic cancer growth by targeting PHGDH. Food Funct. (2019) 10:3386–95. doi: 10.1039/C9FO00394K

89. Song ZW, Feng C, Lu YL, Lin Y, and Dong CY. PHGDH is an independent prognosis marker and contributes cell proliferation, migration and invasion in human pancreatic cancer. Gene. (2018) 642:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2017.11.014

90. Chen SY, Li TY, Liu D, Liu Y, Long ZB, Wu Y, et al. Interaction of PHGDH with IGF2BP1 facilitates m6A-dependent stabilization of TCF7L2 mRNA to confer multidrug resistance in gastric cancer. Oncogene. (2025) 44:2064–77. doi: 10.1038/s41388-025-03374-4

91. Liu J, Zhang C, Wu H, Sun XX, Li YC, Huang S, et al. Parkin ubiquitinates phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase to suppress serine synthesis and tumor progression. J Clin Invest. (2020) 130:3253–69. doi: 10.1172/JCI132876

92. Jing Z, Heng W, Xia L, Ning W, Yafei Q, Yao Z, et al. Downregulation of phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase inhibits proliferation and enhances cisplatin sensitivity in cervical adenocarcinoma cells by regulating Bcl-2 and caspase-3. Cancer Biol Ther. (2015) 16:541–8. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2015.1017690

93. Ma XH, Li BY, Liu J, Fu Y, and Luo YZ. Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase promotes pancreatic cancer development by interacting with eIF4A1 and eIF4E. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. (2019) 38:66. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1053-y

94. Spillier Q and Frédérick R. Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PHGDH) inhibitors: a comprehensive review 2015-2020. Expert Opin Ther Pat. (2021) 31:597–608. doi: 10.1080/13543776.2021.1890028

95. Zhao JY, Feng KR, Wang F, Zhang JW, Cheng JF, Lin GQ, et al. A retrospective overview of PHGDH and its inhibitors for regulating cancer metabolism. Eur J Med Chem. (2021) 217:113379. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113379

96. Spillier Q, Vertommen D, Ravez S, Marteau R, Thémans Q, Corbet C, et al. Anti-alcohol abuse drug disulfiram inhibits human PHGDH via disruption of its active tetrameric form through a specific cysteine oxidation. Sci Rep. (2019) 9:4737. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-41187-0

97. Dong JK, Lei HM, Liang Q, Tang YB, Zhou Y, Wang Y, et al. Overcoming erlotinib resistance in EGFR mutation-positive lung adenocarcinomas through repression of phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase. Theranostics. (2018) 8:1808–23. doi: 10.7150/thno.23177

98. Yoshino H, Enokida H, Osako Y, Nohata N, Yonemori M, Sugita S, et al. Characterization of PHGDH expression in bladder cancer: potential targeting therapy with gemcitabine/cisplatin and the contribution of promoter DNA hypomethylation. Mol Oncol. (2020) 14:2190–202. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12697

99. Soflaee MH, Kesavan R, Sahu U, Tasdogan A, Villa E, Djabari Z, et al. Purine nucleotide depletion prompts cell migration by stimulating the serine synthesis pathway. Nat Commun. (2022) 13:2698. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-30362-z

100. Li X, Wang S, Nie X, Hu YX, Liu OX, Wang YX, et al. PSAT1 regulated by STAT4 enhances the proliferation, invasion and migration of ovarian cancer cells via the PI3K/AKT pathway. Int J Mol Med. (2025) 55:88. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2025.5529

101. Liu JY, Liu LP, Antwi PA, Luo YW, and Liang F. Identification and validation of the diagnostic characteristic genes of ovarian cancer by bioinformatics and machine learning. Front Genet. (2022) 13:858466. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2022.858466

102. Ding XR, Liu HR, Xu QH, Ji T, Chen RX, Liu ZC, et al. Shared biomarkers and mechanisms in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and non-small cell lung cancer. Int Immunopharmacol. (2024) 134:112162. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2024.112162

103. Guo K, Qi D, and Huang B. LncRNA MEG8 promotes NSCLC progression by modulating the miR-15a-5p-miR-15b-5p/PSAT1 axis. Cancer Cell Int. (2021) 21:84. doi: 10.1186/s12935-021-01772-8

104. Ye JL, Huang X, Tian S, Wang JC, Wang HF, Feng HY, et al. Upregulation of serine metabolism enzyme PSAT1 predicts poor prognosis and promotes proliferation, metastasis and drug resistance of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Exp Cell Res. (2024) 437:113977. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2024.113977

105. Montrose DC, Saha S, Foronda M, McNally EM, Chen J, Zhou XK, et al. Exogenous and endogenous sources of serine contribute to colon cancer metabolism, growth, and resistance to 5-Fluorouracil. Cancer Res. (2021) 81:2275–88. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-1541

106. Vié N, Copois V, Bascoul-Mollevi C, Denis V, Bec N, Robert B, et al. Overexpression of phosphoserine aminotransferase PSAT1 stimulates cell growth and increases chemoresistance of colon cancer cells. Mol Can. (2008) 7:14. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-7-14

107. Zhu SX, Wang XY, Liu L, and Ren GS. Stabilization of Notch1 and β-catenin in response to ER- breast cancer-specific up-regulation of PSAT1 mediates distant metastasis. Transl Oncol. (2022) 20:101399. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2022.101399

108. Metcalf S, Dougherty S, Kruer T, Hasan N, Biyik-Sit R, Reynolds L, et al. Selective loss of phosphoserine aminotransferase 1 (PSAT1) suppresses migration, invasion, and experimental metastasis in triple negative breast cancer. Clin Exp Metast. (2020) 37:187–97. doi: 10.1007/s10585-019-10000-7

109. Jie H, Wei J, Li ZL, Yi M, Qian XY, Li Y, et al. Serine starvation suppresses the progression of esophageal cancer by regulating the synthesis of purine nucleotides and NADPH. Cancer Metab. (2025) 13:10. doi: 10.1186/s40170-025-00376-4

110. Luo MY, Zhou Y, Gu WM, Wang C, Shen NX, Dong JK, et al. Metabolic and nonmetabolic functions of PSAT1 coordinate signaling cascades to confer EGFR inhibitor resistance and drive progression in lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. (2022) 82:3516–31. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-21-4074

111. Zhang J, Gangwar S, Bano N, Ahmad S, Alqahtani MS, and Raza K. Probing the role of coniferin and tetrahydrocurcumin from traditional Chinese medicine against PSAT1 in early-stage ovarian cancer: An in silico study. PloS One. (2025) 20:e0313585. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0313585

112. Zhang JL, Wang EH, Zhang L, and Zhou B. PSPH induces cell autophagy and promotes cell proliferation and invasion in the hepatocellular carcinoma cell line Huh7 via the AMPK/mTOR/ULK1 signaling pathway. Cell Biol Int. (2021) 45:305–19. doi: 10.1002/cbin.11489

113. Rawat V, Malvi P, Della Manna D, Yang ES, Bugide S, Zhang X, et al. PSPH promotes melanoma growth and metastasis by metabolic deregulation-mediated transcriptional activation of NR4A1. Oncogene. (2021) 40:2448–62. doi: 10.1038/s41388-021-01683-y

114. Liao L, Ge MX, Zhan Q, Huang RF, Ji XY, Liang XH, et al. PSPH mediates the metastasis and proliferation of non-small cell lung cancer through MAPK signaling pathways. Int J Biol Sci. (2019) 15:183–94. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.29203

115. Peng ZP, Liu XC, Ruan YH, Jiang D, Huang AQ, Ning WR, et al. Downregulation of phosphoserine phosphatase potentiates tumor immune environments to enhance immune checkpoint blockade therapy. J Immunother Can. (2023) 11:e005986. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2022-005986

116. Pralea IE, Moldovan RC, Țigu AB, Moldovan CS, Fischer-Fodor E, and Iuga CA. Cellular responses induced by NCT-503 treatment on triple-negative breast cancer cell lines: A proteomics approach. Biomedicines. (2024) 12:1087. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines12051087

117. Gong KX, Huang YG, Zheng YQ, Zhu YF, Hao WB, and Shi K. Preclinical efficacy of CBR-5884 against epithelial ovarian cancer cells by targeting the serine synthesis pathway. Discov Oncol. (2024) 15:154. doi: 10.1007/s12672-024-01013-0

118. Tseng CY, Fu YH, Kuo CY, Hou HA, Ou DL, and Lin LI. Modulating metabolic reprogramming by phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PHGDH) inhibitors in omipalisib-refractory AML. Blood. (2023) 142:1432. doi: 10.1182/blood-2023-185713

119. Bhalani DV, Nutan B, Kumar A, and Singh Chandel AK. Bioavailability enhancement techniques for poorly aqueous soluble drugs and therapeutics. Biomedicines. (2022) 10:2055. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10092055

120. Xu HT and Liu B. Triptolide-targeted delivery methods. Eur J Med Chem. (2019) 164:342–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.12.058

121. Kim M, Lee JS, Kim W, Lee JH, Jun BH, Kim KS, et al. Aptamer-conjugated nano-liposome for immunogenic chemotherapy with reversal of immunosuppression. J Control Rel. (2022) 348:893–910. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2022.06.039

122. Yang C, Ming H, Li BW, Liu SS, Chen LH, Zhang TT, et al. A pH and glutathione-responsive carbon monoxide-driven nano-herb delivery system for enhanced immunotherapy in colorectal cancer. J Control Rel. (2024) 376:659–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2024.10.043

123. Shi PZ, Cheng ZR, Zhao KC, Chen YH, Zhang AR, Gan WK, et al. Active targeting schemes for nano-drug delivery systems in osteosarcoma therapeutics. J Nanobiotechnol. (2023) 21:103. doi: 10.1186/s12951-023-01826-1

124. Zhang L, Su HL, Wang HL, Li Q, Li X, Zhou CQ, et al. Tumor chemo-radiotherapy with rod-shaped and spherical gold nano probes: shape and active targeting both matter. Theranostics. (2019) 9:1893–908. doi: 10.7150/thno.30523

125. Fan DH, Cao YK, Cao MQ, Wang YJ, Cao YL, and Gong T. Nanomedicine in cancer therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. (2023) 8:293. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01536-y

126. Ma Q, Gao SS, Li CY, Yao JJ, Xie YM, Jiang C, et al. Cuproptosis and serine metabolism blockade triggered by copper-based pRussian blue nanomedicine for enhanced tumor therapy. Small. (2025) 21:e2406942. doi: 10.1002/smll.202406942

127. Hu YH, Nie W, Lyu L, Zhang XF, Wang WY, Zhang YC, et al. Tumor-microenvironment-activatable nanoparticle mediating immunogene therapy and M2 macrophage-targeted inhibitor for synergistic cancer immunotherapy. ACS Nano. (2024) 18:3295–312. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.3c10037

128. Li YY, Jin YY, He XF, Tang YH, Zhou M, Guo WJ, et al. Cyclo(RGD) peptide-decorated silver nanoparticles with anti-platelet potential for active platelet-rich thrombus targeting. Nanomedicine. (2022) 41:102520. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2022.102520

129. Han RX, Liu QY, Lu Y, Peng JR, Pan M, Wang GH, et al. Tumor microenvironment-responsive Ag2S-PAsp(DOX)-cRGD nanoparticles-mediated photochemotherapy enhances the immune response to tumor therapy. Biomaterials. (2022) 281:121328. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.121328

130. Ren Y, Fan Q, Yao X, Zhang J, Wen K, Qu X, et al. A phosphatidylserine-targeted self-amplifying nanosystem improves tumor accumulation and enables efficient tumor therapy by modulating anticancer immunity. Biomaterials. (2026) 324:123526. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2025.123526

131. Buqué A, Galluzzi L, and Montrose DC. Targeting serine in cancer: is two better than one? Trends Can. (2021) 7:668–70. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2021.06.004

132. Jiang HL, Zhang N, Tang TZ, Feng F, Sun HP, and Qu W. Target the human alanine/serine/cysteine transporter 2(ASCT2): achievement and future for novel cancer Therapy. Pharmacol Res. (2020) 158:104844. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104844

133. Yu YJ, Yan JH, Chen QW, Qiao JY, Peng SY, Cheng H, et al. Polymeric nano-system for macrophage reprogramming and intracellular MRSA eradication. J Control Rel. (2023) 353:591–610. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2022.12.014

Keywords: metabolic reprogramming, serine synthesis pathway, phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase, serine deprivation, nanodelivery systems

Citation: Liu H and Liu Y (2025) Recent progress in serine metabolism reprogramming in tumors and strategies for serine deprivation. Front. Oncol. 15:1669565. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1669565

Received: 20 July 2025; Accepted: 20 November 2025; Revised: 27 October 2025;

Published: 03 December 2025.

Edited by:

Tao Liu, University of New South Wales, AustraliaReviewed by:

Giovannino Silvestri, University of Maryland Medical Center, United StatesSuchandrima Saha, Stony Brook Medicine, United States

Copyright © 2025 Liu and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yanping Liu, MjAzNzE1QGhvc3BpdGFsLmNxbXUuZWR1LmNu

Huimei Liu

Huimei Liu Yanping Liu3*

Yanping Liu3*