- 1Department of Community Medicine and Rehabilitation, Unit of Physiotherapy, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden

- 2Faculty of Health and Occupational Studies, Department of Occupational Health, Psychology and Sports Sciences, University of Gävle, Gävle, Sweden

Introduction: Telework is increasing in working life, especially in knowledge intense organizations as academic institutions. Managers are found crucial for performance and wellbeing outcomes in telework, but managers' perspective on leading teleworkers lacks attention.

Methods: This study aimed to investigate academic managers' experiences of leading teleworkers prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic, and their expectations for future leadership in telework. A qualitative study based on interviews with 16 academic middle managers was performed. Findings were analyzed inductively by a phenomenographic research approach.

Findings: The findings show that leading teleworkers was characterized by demands posed by remote and digital communication; regulation and policies; occupational health and safety management; and new norms for leadership.

Discussion: In conclusion, academic institutions need to improve organizational resources for managers' leading teleworkers to facilitate successful leadership and to secure sustainable work conditions for managers as well as for teleworking employees.

1 Introduction

Teleworking, i.e., to distribute a part of the working hours from an optional location outside the conventional workplace while maintaining contact with colleagues and managers using information and communication technologies (ICTs) (Allen et al., 2015), is growing in demand and predicted to become a key competitive factor for organizations in the future (Eurofound, 2022). This is partly because of the progressive digitalization in working-life (Chirico et al., 2021; Eurofound, 2022), partly due to the sudden rise in telework forced by the COVID-19 pandemic (Kniffin et al., 2021). Teleworking is also becoming a more attractive option for employers and employees because of the expected organizational and individual benefits. For organizations, teleworking is suggested to improve conditions for ecological and financial sustainability by decreasing the need for daily work commuting and large office spaces and by giving competitive advantages through expanded geographical reach for recruitment and collaborations (Kim et al., 2021). For individual employees, teleworking could allow greater autonomy in terms of flexibility to accommodate the place, time, and structure of work to private and professional circumstances, facilitating work-non-work balance, work performance and job satisfaction (Beckel and Fisher, 2022; Lunde et al., 2022). Outcomes of telework are, however, shown to vary significantly and challenges have also been associated with this way of working. For instance, the absence of conventional workplace structures can challenge individual prerequisites for sustainable physical, psychological, and social work conditions (Beckel and Fisher, 2022; Vartiainen and Vanharanta, 2024). Like, it can be difficult for employees to create functional spatial (De Macêdo et al., 2020) and temporal structures for working hours and breaks; separate and restrict work-nonwork roles and activities; and detach physically and psychologically from work after working hours (Kotera and Vione, 2020; Lunde et al., 2022). In addition, teleworking may change and complicate work processes, collaboration, and socialization because of communication mainly being practiced through ICTs, limiting face-to-face interaction and risking interactional difficulties and performance issues (Cortellazzo et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2021).

The possible negative effects of teleworking got more attention due to the transition to homebound work forced by the COVID-19 pandemic. The characteristics of the pandemic's homebound work were sometimes argued to exacerbate the challenges associated with traditional telework, especially regarding physical and psychological work-non-work boundaries, social interaction and digital working methods (Chirico et al., 2021; Peiró and Martínez-Tur, 2022). Because in this situation autonomy and spatial flexibility were generally limited or absent, which generated a remote work situation different to traditional telework (Chirico et al., 2021).

Following the pandemic's increase in teleworking and associated challenges, scholars (Antonacopoulou and Georgiadou, 2021), practitioners and employers (Eurofound, 2022) continue emphasizing the necessity for gaining more knowledge on how to promote sustainable, productive and healthy work conditions in telework. Existing research has primarily examined telework outcomes at the individual level, often guided by occupational (Margheritti et al., 2024; Rohwer et al., 2024) and leadership theories (Antonacopoulou and Georgiadou, 2021), using quantitative methods such as surveys (Lunde et al., 2022; Vartiainen and Vanharanta, 2024). Generally, these studies conclude that managers and leadership have a major impact on telework outcomes, e.g., by mediating the relationship between telework and work performance and wellbeing outcomes (Cortellazzo et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2021). Overall, managers' provision of instrumental and social resources has shown to significantly influence these outcomes among teleworkers and workgroups. Instrumental resources can include financial, technical and educational resources, while social resources encompass, e.g., relational support, recognition and performance feedback by managers and coworkers. This has, among other things, been illustrated through the job-demand resource (JD-R) theory (Bakker and Demerouti, 2018), which has frequently been used to analyze employee conditions in telework (see Perry et al., 2018). According to the JD-R theory (Bakker and Demerouti, 2018), wellbeing in work can be determined by the congruence between the resources in work and job demands (e.g., workload, tasks, time pressure, conflicts). While congruence between job demands and resources can contribute to employee job motivation and satisfaction of basic psychological needs at work; incongruence can start a “health-impairment process” with the risk of stress and both short- and long-term consequences to health and work performance (Bakker and Demerouti, 2018). Accordingly, previous studies have shown that managers' provision of resources in terms of strong social support can reduce psychological strain among teleworking employees (Brunelle, 2013; Nayani et al., 2018) and facilitate teleworkers' productivity and commitment to work (Kwon and Jeon, 2020). A strong social support by managers has also been seen to mitigate the negative impact of the geographical and social distance in telework on the quality of workgroup relationships (Brunelle, 2013).

The importance of managers providing teleworking employees with necessary work-related resources has also been concluded in studies guided by leadership theories (e.g., Antonacopoulou and Georgiadou, 2021; Varma et al., 2022). Above all, social support in terms of managers' trust-building efforts and the quality of the relationship between managers and their employees have emerged as critical for teleworking outcomes. For instance, relationship-oriented and transformational leadership approaches, characterized by considerate, motivational, and intellectually stimulating behaviors, have in some studies been associated with enhanced organizational performance, job satisfaction, and retention among teleworking employees (Varma et al., 2022). Similar beneficial outcomes have been recognized for leadership behaviors derived from transactional leadership (Howell and Hall-Merenda, 1999) and the leader-member exchange (LMX) theory, that is, managers focusing on providing resources (e.g., influence, information, economic reward, schedule latitude) in exchange for employee loyalty, collaboration and performance (Margheritti et al., 2024; Varma et al., 2022).

Because of the important role of managers in teleworking, a great deal of responsibility for telework arrangements, and the success of those, in organizations has been placed on managers and their leadership practice. Recent reviews have listed a wide range of demands that managers need to meet in order to create sustainable working conditions in telework. These include everything from major structural decisions regarding, e.g., policies and telework agreements to individually tailored work adjustments (Beckel and Fisher, 2022; Vartiainen and Vanharanta, 2024). Further, leadership roles and team management in virtual spaces have garnered significant attention, especially post the COVID-19 pandemic. It is argued that the competencies required for effective leadership in virtual environments differ substantially from traditional face-to-face interactions. Managers need to evaluate the preparation for digital transition and address inequalities in digital competencies in organizations. It is also important for managers to handle “digitalized competences” that is, the transformation of non-digital skills influenced by virtual spaces and tools (Peiró and Martínez-Tur, 2022).

Despite the identified importance of managers, less attention has been directed toward manager perspectives on leading teleworkers (Beckel and Fisher, 2022; Vartiainen and Vanharanta, 2024). Existing findings, however, indicate that telework may alter the power dynamics of organizational hierarchies by decreasing managers' influence over the place, time and structure of employee work (Cortellazzo et al., 2019). This might change managers' prerequisites to monitor and influence employees' work processes, work environment and relationship proximity, which possibly might affect managers' leadership and provision of resources to employees (Cortellazzo et al., 2019). Managers' perceptions of diminished influence have been linked to heightened surveillance of teleworkers or the restriction of telework opportunities, both of which can adversely affect employee wellbeing and erode trust in management (Eurofound, 2022; Groen et al., 2018).

While teleworking has become an available option among a wide range of professions, teaching- and science professionals are among the most frequent teleworkers (Eurofound, 2020). Academic institutions' prevailing digitalization, including a rising shift to telework and distance education, has been argued to increase employee workload and demands for self-regulation while reducing academic managers' influence over work processes (Batalheiro Ferreira, 2022; Warren, 2017). As in other occupational groups, staff in academic institutions are seen struggling with work-nonwork boundaries, social relationships and collaboration in telework (Plotnikof et al., 2020; Widar et al., 2022). For academic managers, telework and digital communication has been described as hindering managers' demonstration of concern and recognition for employees, complicating the cultivation of manager-employee trust and challenging managers' support of employee performance (Alward and Phelps, 2019; Sjöblom et al., 2022).

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the digitalization in academic institutions, creating a complex work environment for faculty staff as well as managers. While staff generally seemed to perceive more emotional difficulties due to the homebound work than their managers, managers could have a harder time adjusting to the work situation (Carillo et al., 2021). For instance, in some studies, the transition to more remote and digital solutions, such as that of distance teaching, was found particularly challenging for managers overseeing the process (Kniffin et al., 2021). Moreover, studies indicated that managers' leadership could change because of the pandemic situation, as to become more bureaucratic and even intrusive (Giedre Raisiene et al., 2022).

Although the outcomes of teleworking in academic institutions are largely consistent with those found in other occupational groups, the context for leadership is argued to be different (Alward and Phelps, 2019; Warren, 2017). Leadership in academic institutions is described as characterized by its inherent complexity, necessitating a nuanced understanding of diverse faculty dynamics, including staff of different functions, professions, academic fields, and nationalities. Managers in this context are responsible for harmonizing the varying professional identities with goals set by the organization, stakeholders, and politicians. The interplay of autonomy, collegiality, and the increasing digitalization and globalization further complicate academic leadership. As the nature of work continues to shift, the role of academic leaders is increasingly defined by their capacity to facilitate change and nurture trust among faculty members, thereby ensuring institutional resilience and effectiveness. Consequently, the complex nature of academic institutions is suggested to demand more adaptive leadership approaches than other sectors (Alward and Phelps, 2019; Warren, 2017).

Previous studies have investigated different aspects of academic leadership in telework, both prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic, however most studies have done so quantitively and through predefined theoretical frameworks (Beckel and Fisher, 2022; Cortellazzo et al., 2019). Although it is of relevance, it may also create empirical constraints. Considering the complex environment of academic institutions and the diverse nature of academic leadership, it is appropriate to adopt more qualitative and inductive study approaches as it would allow a more open and broad investigation of academic leadership in telework. Further, studies on telework, in academia and in other sectors, are often either limited to traditional telework or homebound work during the pandemic. Additionally, studies mostly include managers with limited or no experience of leadership in traditional telework arrangements (Allen et al., 2015; Cortellazzo et al., 2019). Overall, the methodological limitations restrict the findings' ecological validity. Investigating the perspective of managers experienced in leading both voluntary and forced remote workers could provide a more authentic insight in the context of leadership in telework. The aim of this study was therefore to investigate the perspectives on leadership in telework among academic managers with experience of leading traditional teleworkers prior to and homebound workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. The aim was also to explore these managers' expectations for academic leadership in future telework. Investigating these three-time perspectives could allow a greater understanding of the preconditions, opportunities and challenges for practicing leadership in teleworking.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study design

This study used a qualitative phenomenographic research approach, which relies on a second-order perspective where the aim is to identify the qualitatively different ways a certain phenomenon is experienced (Marton and Pong, 2005). The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Uppsala, Sweden (Reg. no. 2020-06012).

2.2 Study sample and recruitment

The study sample included 16 (8 female and 8 male) academic first-line or middle managers. Only managers with experience of leading teleworking employees who had held their managerial position at least 1 year prior to study start in March 2020 were included. This ensured that managers were experienced in leading teleworkers in an ordinary, i.e., non-pandemic, work setting. In total, 97 eligible participants from 16 Swedish universities were identified by personnel information provided by their universities' Human Resource (HR) departments or displayed on their universities' websites. To achieve sample variation and representativeness, participants were strategically selected based on their age, gender, academic field and their universities' geographical locations and sizes. Selected participants were sent an email invitation to participate, containing information on the study aim, procedure, and consent for participation. Email reminders were sent 2 and 4 weeks after the first invitation, and the interviews were then booked. The sampling was performed consecutively in order to reach the required number of participants. The final sample included academic managers from the fields of pedagogy, economics, odontology, public health, neurophysics, biology, and textile design, based at nine different public universities across both rural and urban areas in Sweden. On average, the participants had held their position as executive manager for 3 years (prior to the pandemic), their managerial responsibilities were about 68 percent of their total worktime, and their span of control constituted 8–150 (x 45) employees, which was representative of the study population.

2.3 Data collection

The interviews were conducted using a semi-structured interview guide, divided into three-time perspectives, and consisting of 13 open-ended questions, along with follow-up questions. The first-time perspective focused on leading teleworkers before the pandemic, addressing opportunities, challenges and resources. The second focused on leadership during the COVID-19 homebound work period, exploring changes in work practices and management strategies. The third looked at future telework leadership, including expected changes in leadership conditions and managerial needs. The interviews were held individually by one of the authors [LW] during digital meetings in Zoom® video platform (Version 5.7.7). The interviews lasted 41 to 67 min, were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. The data collection started in August 2020 and ended in September 2021, when the interview material was considered to have reached sufficient saturation (Guest et al., 2020).

2.4 Qualitative analysis

The data was analyzed using a phenomenographic approach to identify similarities, differences, and nuances in the participants' lived experiences. The analysis followed the seven steps described by e.g., Marton and Pong (2005). Accordingly: (1) Initially, the interview transcriptions were read through several times to form a naïve understanding of the content. (2) The material was then read through more deliberately to identify and highlight quotes capturing the study aim. The quotes were sorted into three-time perspectives, which were treated separately. (3) Quotes were compiled and condensed into smaller text-units containing only the essence of the main quotes constituent parts. (4) Text-units with similar essences were grouped and then contrasted to distinguish their uniqueness whereafter they were formed into categories. (5) Within each category, the content was analyzed to identify similarities, differences, and nuances, (6) which were manifested into subcategories. (7) Lastly, similar categories of each time perspective were brought together and aggregated into overarching main categories, resembling their common essence.

3 Findings

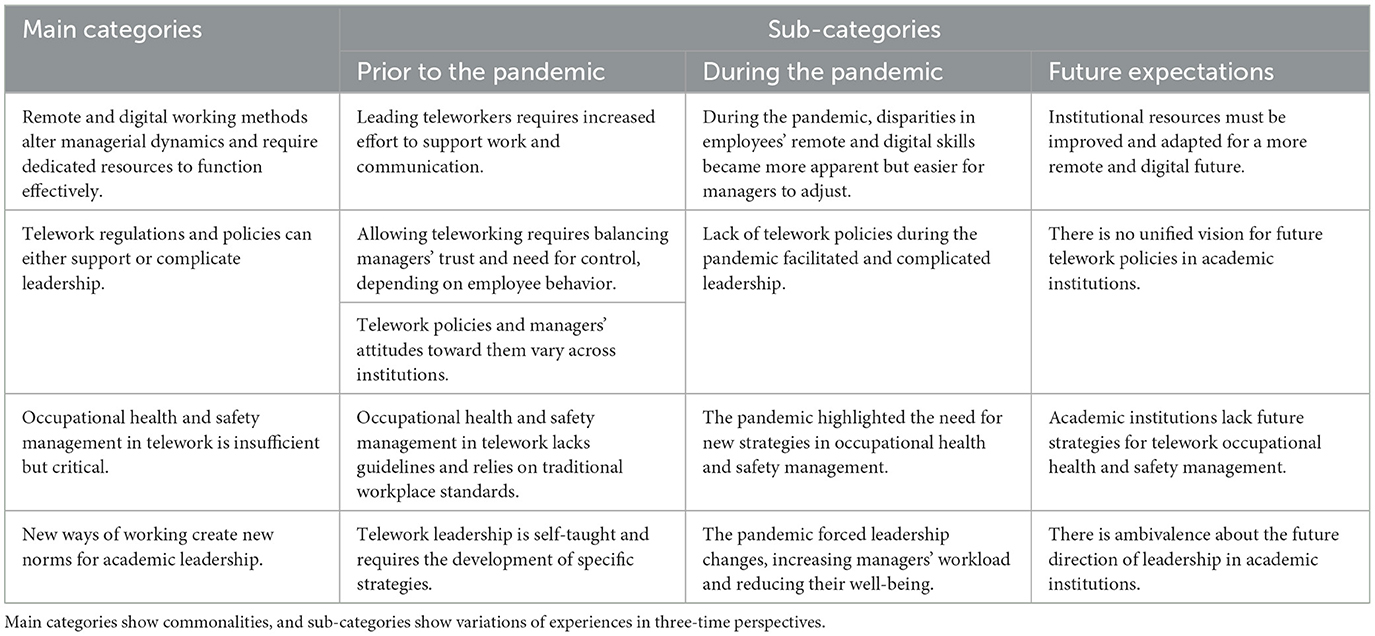

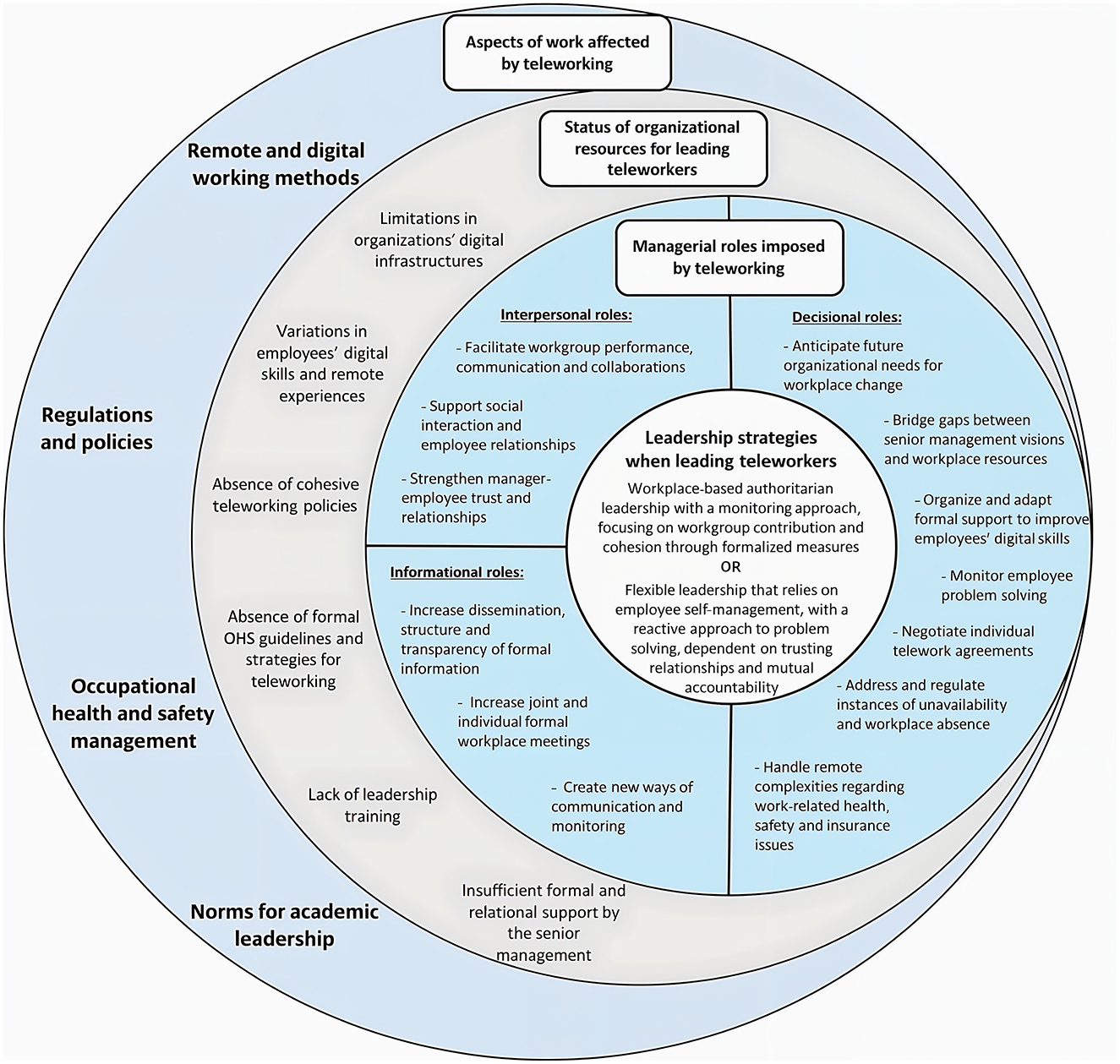

The analysis identified four main categories representing academic managers' common experiences and expectations of leading teleworkers, as well as 13 categories detailing diverse experiences across the three different time perspectives (see Table 1 for category overview). The categories were related to remote and digital working methods, regulations and policies, occupational health and safety management, and new norms for academic leadership. Figure 1 details the conditions for leading teleworkers in academia in terms of organizational resources, managerial roles and leadership strategies.

Figure 1. Academic managers' organizational conditions, managerial roles and leadership strategies for leading teleworkers.

3.1 Requirements for remote and digital working methods

Leading teleworkers requires increased effort to support work and communication. Remote and digital communication could place higher demands on managers to provide more and clearer information, structure, and documentation of meetings to prevent unclarities and misunderstandings among employees. This was because communication through digital platforms, emails, and phone calls was generally perceived as more superficial and harder to interpret, challenging meaningful conversations and constructive dialogues (e.g., feedback and problem-solving) between managers and employees. Nonetheless, some conversations could be easier to handle through digital means: “If you talk about something that is a bit more sensitive or difficult, it feels a bit freer to interact digitally than coming into a room and sit down on a chair and having a face-to-face conversation. I think it slightly affects the power balance, because you as a manager don't get the same position of power in a digital meeting as when you bring someone into your office.” (Informant 1).

During the pandemic, disparities in employees' remote and digital skills became more apparent but easier for managers to adjust. The pandemic entailed an increased load of learning new technologies and digital systems, which could be difficult for managers to monitor due to the lack of opportunity for joint physical meetings. The challenge was enhanced by disparities in employees' prior experiences of remote and digital work methods and communication. While experienced employees worked in a more structured and efficient way and coped better with work-related problems, unexperienced employees could struggle with work and communication, requiring managers to provide additional support. To deal with this, managers could mobilize institutions' technical and educational supporting functions and resources, who provided practical guidance, training, and discussion forums, facilitating employee work and interaction: “I think there is a tendency toward relationships not being quite as smooth as they used to be. That you write an email, and it gets a little too short handed. Sometimes it can be perceived as a bit aggressive, even if it's because the person writing is in a bit of a hurry. I also recognize this in the relationships between students and teachers.” (Informant 16). Despite challenges, managers generally considered the increased digitalization as a positive development because it necessitated an enhancement of digital competencies across the workforce and created more equitable conditions for improving it. Sometimes it also contributed to employees becoming more aware of the efficiency gains of more digitalized work, such as that of distance teaching freeing up more time for teacher-student interaction.

Institutional resources must be improved and adapted for a more remote and digital future. Managers expected remote and digitalized work (e.g., distance teaching) to become more possible and requested in the future, because of employees' preferences and senior managements' plans for such a development. This could mean both benefits and challenges to leadership. Partly, it was argued to benefit academic institutions in terms of education quality, economy, recruitment and international collaboration. It also had the potential to decreased work-related travel, which could improve the work environment for both managers and employees. However, to achieve benefits, academic institutions needed to update their digital infrastructures (e.g., competences and resources) otherwise the development risked leading to poor work conditions, particularly for employees with poor digital skills. Changes to physical premises would likely also be required, such as converting single-cell offices into open-plan offices, which was suspected to reduce employees' willingness to work at the office. As academic institutions rarely had sufficient resources to implement the necessary changes, the managers believed that increased remote and digitalized work would mean increased challenges for managers' to maintain workgroup relationships, performances and collaborations: “It can provide security for the employees if I act as some sort of barrier to all these signals that come from the senior management. They argue that now we can reduce rent, now we can have home offices or now we can digitalize everything, and that distance learning is much better. But it doesn't really work that way, because we don't have sufficient digital infrastructure. If there is too much of this visionary talk from the senior management without it being backed up with resources and planning: I think it can create quite a lot of uncertainty among employees.” (Informant 15).

3.2 Challenges to telework regulations and policies

Allowing teleworking requires balancing managers' trust and need for control, depending on employee behavior. Telework agreements were often shaped by a combination of organizational policies, individual negotiations, and informal understandings. Managers who had fostered trusting relationships with their employees tended to view formal regulations as unnecessary, arguing for self-managed teleworking according to the general working hours agreement. However, a general apprehension regarding teleworking was evident, as managers established requirements focused on workplace presence, task suitability, and performance metrics. Instances of teleworking employees' unavailability and high absence from the workplace, particularly among senior researchers, prompted managers to implement stricter regulations, reflecting concerns about collaboration and team dynamics. Some managers suspected a weak relationship between them and the employees as an explanation for teleworkers unavailability: “Sometimes I don't feel completely confident about the relationship between me and a certain employee. If that's the case, their absence from the workplace could make me wonder if there is something that causes this person to avoid me.” (Informant 8). Follow-up practices, including phone calls and meetings, emerged as crucial for addressing mismanagement and reinforcing teleworking protocols, sometimes resulting in disciplinary actions or employment termination: “If you mismanage telework, then you must sit down with me and get this list of “kindergarten rules” with dos and don'ts for telework. Like, you must notify me whenever you need to make a personal errand like go to the dentist or inspect the car or whatever. But if it has gone that far it is usually not an employee I wish to continue working here.” (Informant 13).

Telework policies and managers' attitudes toward them vary across institutions. The absence of cohesive teleworking policies across institutions, departments and personnel groups was a recurring theme. Managers described consequences, as it reducing leadership to a problem-solving function, and complicating decision-making regarding, e.g., telework allowance. An absence of organization-wide policies could be perceived as managers lacking mandate to formally regulate teleworking. Managers believed that their examples of regulations and follow-ups could facilitate an insight into teleworking and signal a concern for employee work conditions. However, such initiatives by the senior management were generally considered an action of mistrust or need for control. Managers emphasized the importance of considering both managers' and employees' needs when designing policies, but this was difficult to achieve. Policies could be appreciated and accepted but also opposed by academics because they did not like being directed: “The working hours agreement states that: if the work tasks allow it and the manager permits it, the employee may perform certain tasks outside the workplace. It's not a given right, it's an opportunity. But if we managers would start sticking our noses into docents, lecturers, and professors' businesses they would go crazy. So, you need to find the right balance of control.” (Informant 5).

Lack of telework policies during the pandemic facilitated and complicated leadership. Initially, the lack of organization-wide policies provided managers flexibility in leading the homebound employees. However, it ultimately led to a loss of managerial control and difficulties to support employees' work performance and wellbeing: “Staff that performed well before the pandemic have performed well during the pandemic, while those who misbehaved before are misbehaving even more now. I've had a few cases when I had to give staff reprimands over Zoom, it just doesn't turn out well. So, the biggest difference is that you lose control over those who can't behave.” (Informant 13).

There is no unified vision for future telework policies in academic institutions. Telework policies, e.g., common frameworks for where, when, and how employees should meet and interact, could become a critical yet challenging factor for successful leadership in future telework. Nonetheless, managers had mixed opinions regarding their senior management's plans for such policies. On the one hand, policies encouraging teleworking risked triggering a “too high” frequency of it, risking to diminishing the value of employee in-person interaction at work. On the other hand, policies including more stringent regulations could be unrealistic relative to organizational resources and employees' needs and, as such, become a burden for both managers and employees. Rather than rigid regulations, the managers emphasized the need for flexible telework policies, tailored to individual workgroup dynamics and employee needs. However, they also advocated organization-wide regulations to mitigate competitive disparities between departments regarding telework allowance. These approaches were believed to foster a cohesive work environment while addressing the diverse needs of employees, ensuring that telework remained a supportive tool rather than a divisive factor in academic institutions. Additionally, some managers suggested that more flexible telework policies could reduce employee sickness absence as well as minimize risks associated with sickness presenteeism: “If you look at the sickness absence rate for professors and lecturers, you will see that there is basically no sickness absence to speak of, even if they are sick just as much as everyone else. If you‘re sick one day, you just take the day off and then you make it up another day, like Saturday or Sunday. I think that will also change for the administrative staff in the future like, let's say they are a bit snotty on a Monday, well then, they will just work at home that day. They won't go to the workplace, and then we will avoid the spread of infections. I think we should include that in new contracts, that days like that you should work from home.” (Informant 11).

3.3 Limitations in occupational health and safety management

Occupational health and safety management in telework lacks guidelines and relies on traditional workplace standards. This left managers ill-equipped to address the unique challenges posed by teleworking. Overall, OHS management in telework was a neglected area, often delegated to the responsibility of supporting functions (e.g., Human Resources) or left to the employees to handle themselves: “The work environment and the discussions about it are concentrated to the on-site workplace environment. I can't remember that we ever even talked about some kind of work environment in telework.” (Informant 12).

The pandemic highlighted the need for new strategies in occupational health and safety management. There were several strategies that academic institutions could adopt to enhance employees‘ homebound work environment. These included managers being encouraged to maintain regular contact with employees and follow up on their work conditions. Some institutions successfully implemented digital reviews of employees' homebound work environments and provided them with essential work equipment, such as ergonomic furniture and desktop tools. There were also initiatives, like digital walk-and-talk meetings, to promote physical activity and mitigate feelings of isolation among employees.

The forced homebound work, however, introduced new complexities regarding work-related health, safety and insurance issues. Employees faced heightened risks of isolation, increased workload, and diminished job motivation, but managers lacked formal guidelines and practical tools for effectively identifying and acting on it. In addition, the psychological and social dimensions of homebound work were frequently overlooked, with many managers expressing discomfort in probing into employees‘ psychosocial needs. Managers' reluctance stemmed from a perception that such inquiries might be intrusive, which led them to delegate such issues to HR, professors or other roles with closer relationships with employees.

The institutional support available to managers was largely inadequate. While some academic institutions attempted to provide verbal encouragement, this was considered insufficient for addressing the multifaceted nature of OHS in the homebound work. Consequently, managers struggled and felt alone, particularly those without prior experience of handling OHS in telework: “I have sent out surveys, I have received responses, and I have confirmed them. If it sounds like someone needs a little more help, I‘ve called and talked and listened to them. But I've done all this based on some sort of common sense, because I'm not a pro at these things, nobody is. It is just expected that we [managers] have good judgment. I have often thought to myself, how do I know that I am doing the right things?” (Informant 7).

Academic institutions lack future strategies for telework occupational health and safety management. While some academic institutions had formed committees to develop future OHS policies, these were often mainly focused on quantitative metrics rather than qualitative aspects such as employee needs for wellbeing in telework. Without adequate support, managers, especially those with large workgroups, thought the fulfillment of OHS in future telework could be difficult and increase their workload. The ambiguity surrounding academic institutions' accountability for OHS management in telework left many managers uncertain about whom to approach for guidance and support, both regarding their employees' and their own work environment and wellbeing in telework.

3.4 New norms for academic leadership

Telework leadership is self-taught and requires the development of specific strategies. Academic managers described their role as involving the management of both office- and teleworkers, with workplace presence serving as a dual strategy for integrating with the workgroup and fulfilling managerial expectations. Academic institutions' lack of training for leadership in telework forced managers to navigate this new terrain independently, often relying on their own experiences as teleworkers. Managers described effective leadership in telework as requiring a distinct set of strategies, such as a more structured, clear, and motivating leadership, to ensure employee work performance. Building closer relationships with teleworking employees was also important, as to enhance managers' insight into their work situations, life circumstances, and overall wellbeing. However, it was complicated and sometimes failed, leaving some managers feeling socially excluded as their employees teleworked: “I can feel like I am losing a bit of my control, especially when I don't have my staff around me, when everyone is working at a distance from different places. Sometimes I imagine to myself that they're sitting over there talking to each other about me. That isn't the case, but you can get that kind of feeling that things are happening somewhere else, and you are not there.” (Informant 15).

The pandemic forced leadership changes, increasing managers' workload and reducing their wellbeing. The pandemic significantly altered the managerial role, reducing it to a reactive problem-solving function primarily focused on personnel issues. Managers recognized a greater request among employees for performance-focused meetings and formal information rather than for social initiatives. In response to this, managers could enhance the frequency of information dissemination through emails and digital meetings, striving for greater transparency in their planning and decision-making processes. They also organized informal digital meetings to foster social relationships, although employees' participation declined over time because of their high workload or discomfort with socializing digitally. Further, the introduction of new employees presented unique challenges, as traditional mentorship and support systems were disrupted. Managers adapted by establishing regular follow-ups through phone calls and digital meetings, which could function well. Overall, the increased frequency of meetings and pressure to address employee complaints and new challenges could contribute to stress and loss of job satisfaction among the managers: “Other than being boring, leadership in telework has been quite stressful because of the load of emails. That's almost the biggest thing, the emails are pouring in. I don't have to act on all of them, but I must decide whether to act or not and that has been significantly more stressful than before. Then I find it extremely boring and frustrating that I don't feel like I'm doing a good job as a manager. I'm not really the manager I'd like to be.” (Informant 10). During the pandemic situation, managers expressed frustration over insufficient organizational support and lack of clear communication from their senior management, hindering their fulfillment of managerial responsibilities and complicating their engagement in institutions' developmental work.

There is ambivalence about the future direction of leadership in academic institutions. Some managers necessitated an adaptation of a more remote and digital realm and anticipated a more authoritative leadership approach to maintain an oversight and control when leading future teleworkers. Others declared that they did not wish to continue working as a manager if teleworking would become the new norm for work. Most managers aim to return their leadership practice to the traditional office setting to rebuild employee workplace identity and enhance relational climates. Nonetheless, they could express concerns regarding employees experiencing discomfort in workplace interactions when returning to the post-pandemic office. This led to plans for more phased returns accommodated to employees' needs as well as suggestions for improving workplace facilities to make the office more attractive for employees: “I believe that our business should be run on site. My ambition is for us to return as much as possible to what we had before, I think my teachers generally feel good about it, but we should also continue to have the freedom we've had before. We have had many discussions before about digitalization, where those who advocate digitalization are like prophets talking about a golden future, like: if we just do everything digitally and use technological aids the learning will be better, and we'll be more efficient, and we can have more time for our families. But I think we also have learned the costs of it, like the loss of interpersonal meetings.” (Informant 12).

4 Discussion

We aimed to investigate academic managers' experiences of leading teleworkers prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic, and their expectations for leadership in future telework. Overall, the managers viewed telework as a natural self-managed feature of academic work. However, the pandemic situation contributed to managers reflecting more actively on the pros and cons of teleworking, especially in relation to their own work and leadership. Jointly, our findings reveal several complexities regarding leading teleworkers in academic institutions, which were related to remote and digital working methods, regulations and policies, OHS management, and new norms for academic leadership.

Previous studies of leadership in telework, or homebound work during the pandemic, have primarily included managers with little or no prior experience of leading employees remotely (Allen et al., 2015; Cortellazzo et al., 2019). These studies often show that leading remotely could pose challenges and increase demands for managers and their leadership. Our study shows that even managers with prior remote-leadership experience could experience an increase in demands and challenges when leading teleworkers.

4.1 Remote and digital challenges to managers' support

Like in other studies (Alward and Phelps, 2019; Antonacopoulou and Georgiadou, 2021), our findings conclude that leading teleworkers necessitates a heightened commitment from managers to foster effective communication and problem-solving. However, our findings also indicate that managers do not always have the necessary conditions to do so. Remote and digital interaction have sometimes been described as a threat to the effectiveness of workgroups (Ruiller et al., 2019). One reason for this could be social communication difficulties when using digital interaction, which can complicate interpersonal dialogues and slow down problem-solving processes. Another source could be organizational members digitalized competences (Kniffin et al., 2021; Peiró and Martínez-Tur, 2022). We found that such aspects determined the success of academic managers' digital communication with and support of employees in telework and homebound work. Like previous studies (Cortellazzo et al., 2019; Peiró and Martínez-Tur, 2022), disparities in academic staffs' digitalized skills complicated managers' support of staff work performance and wellbeing. Digitalized competences, i.e., transformation of non-digital skills enforced by technological change, affect the transition to and practice of work in virtual spaces and thus determines the achievement of sustainable digital development (Peiró and Martínez-Tur, 2022). Variations in digitalized competences among organizational members risks creating inequalities regarding, e.g., performance of work tasks and professional development. An effective leadership, supporting problem-solving and maintaining team dynamics, in virtual spaces is argued to require understanding as well as mastering of digitalized competence. This also needs to be integrated with managers' psychosocial competences. Prior studies show that organizations may lack adequate preparation for increased digitalization, such as training for managers in handling and leading digitalized work methods (Cortellazzo et al., 2019; Peiró and Martínez-Tur, 2022). In the pandemic situation, we found that academic institutions' supporting functions in IT and education could help managers deal with difficulties regarding staffs' digitalized competences. Nonetheless, managers emphasized an overall limitation in institutions' digital infrastructures which they thought could hinder a functional development of future hybrid work solutions.

4.2 Managerial trust and telework policies

Research indicates that teleworking may decrease managers' decisional power over employees' work in terms of performance, relationships and location, which is argued to increase the importance of managers having trust in employees teleworking. The importance of trust-building efforts has in part been illustrated through the LMX theory showing that the relational quality of manager-staff relationship could have a direct effect on outcomes such as work performance and wellbeing in telework (Cortellazzo et al., 2019; Varma et al., 2022). According to the theory (Graen and Uhl-Bien, 1995), employees' work performance is dependent on the psychological contract established by the trust given by managers when allowing telework and, conversely, managers trust relies on employees' ability to achieve their work goals. In studies on telework, the LMX theory has underscored the influence of managers' trust in employees' trustworthiness, conscientiousness, and communication qualities on managers' willingness to allow telework (Varma et al., 2022). The present findings reveal a complex interplay between managers' trust, and need for control when leading teleworkers in academia. Although managers generally described a trusting relationship with their employees, managers' trust could be violated by employees' mismanagement of telework. Contrary to studies suggesting that managers are more inclined to support telework for employees with high task independence (Lembrechts et al., 2018; Silva et al., 2019), our results show that academic managers could be reluctant to endorse teleworking for employees with the highest task independence (e.g., professors) due to concerns over these employees' mismanaging their teleworking. Managers could also feel a need to follow-up, regulate or restrict teleworking by different measures. This might suggest that academic employees might not adequately contribute to the establishment of a trustful relationship with their manager when teleworking. This may be explained by previous findings showing that digital interaction in telework could change the power dynamics between the management and employees by destructing traditional hierarchies. According to such findings, hierarchical leadership may have less influence over employees when work interaction becomes more digitally based (Cortellazzo et al., 2019). Further, the present findings might contradict earlier findings proposing managers to exhibit less trust-building efforts when leading experienced teleworkers (Kim et al., 2021).

Some studies argue for organizations to adopt joint telework policies or regulations to support managers' responsibilities and leadership in telework (Nayani et al., 2018; Silva et al., 2019). In the present findings, managers could argue for policies or regulations if they believed these could benefit academic institutions' performance, competition or recruitment, but they could question policies if these were believed to hinder employees' ability to balance work and personal needs, as it could negatively impact work performance and wellbeing. Our findings align with the duality of workplace policies in academic institutions, described and criticized in prior research for ostensibly promote work-life balance but ultimately serve to bolster organizational productivity at the expense of employee wellbeing (Saltmarsh and Randell-Moon, 2015; Warren, 2017). The inclination to encourage telework as a substitute for sickness absenteeism, recognized in our findings, raises ethical questions and warrants further examinations of academic institutions' true intent behind telework policies.

4.3 Occupational health and safety management in telework

The present findings showed a general lack of formal OHS guidelines for teleworking in academic institutions, which became more apparent to managers because of the shift to homebound during the pandemic. The absence of guidelines left managers ill-prepared to address the unique OHS challenges in the pandemic's homebound work as well as in traditional telework. Earlier findings have revealed a troubling dynamic in which senior management prioritizes employee performance over health and safety in telework (Nayani et al., 2018; Sjöblom et al., 2022). Above all, deficits in organizations' engagement in employees' psychosocial safety climate in telework have been acknowledged (Sjöblom et al., 2022). Our findings show that insufficient formal guidance on OHS management in telework could make managers insecure regarding their role in addressing employees' psychosocial wellbeing, resulting in reluctance to engage in employee mental health matters. This phenomenon has been seen in studies on OHS management in conventional work settings, also revealing employers and managers' knowledge on mental health as lower than of physical health (Ebbevi et al., 2021). Managers exhibiting avoidant behaviors when leading teleworkers can foster a sense of neglect among employees, potentially exacerbating feelings of isolation during telework (Harris, 2019; Nayani et al., 2018). Collaboration between managerial levels, and with OHS representatives in organizations can prevent such outcomes and facilitate functional OHS management (Nayani et al., 2018). In present findings, the managers could delegate some of the OHS responsibility to the HR managers or the head of subject in teaching, however, managers were mostly left alone with the responsibilities for maintaining OHS standards in telework. This could reflect the broader trend of individualization within academia (Saltmarsh and Randell-Moon, 2015; Warren, 2017), indirectly suggested to undermine collective efforts to systemic address OHS challenges in telework.

4.4 New norms for leadership

The findings from this study highlights the complex evolving of managerial roles and leadership in telework. Leading face-to-face at the office seemed to be the academic managers' primary and preferred leadership strategy, both in general and when leading teleworkers. They consistently emphasized workplace interaction as crucial for maintaining their own as well as their employees' relationships, motivation, community, and sense of belonging in work. A large part of previous research has highlighted relationship-oriented leadership behaviors (i.e., show recognition, give feedback and regularly interact with employees) as most important for work satisfaction and performance in telework (Antonacopoulou and Georgiadou, 2021; Margheritti et al., 2024). However, existing research suggests that managers may increase their output control as employees are teleworking to compensate for the lack of ability to directly supervise employees at the conventional workplace (Groen et al., 2018). Such tendencies were, as described above, recognized in the present findings. Some researchers argue that managers should be more performance-oriented when leading teleworkers (Kim et al., 2021; Kwon and Jeon, 2020). For instance, managers are recommended to develop more objective and reliable performance measures for regularly following up on teleworking employees' work (Groen et al., 2018). Studies on the academic work context show that the advancement of technology and digital work methods could force academic managers to develop more effective approaches to leadership to secure a knowledge-processing environment. Academic managers might need to become more business oriented to fit in with the more remote, globalized and competitive context of academic institutions. Some researchers even argue that the role of academic managers is now to engage in emergent problem-solving and control information flows rather than employees (Alward and Phelps, 2019). A shift toward more informational or decisional managerial roles (Mintzberg, 2009) was indicated in the present findings as managers described their main activities when leading teleworkers and homebound workers. The managers described planning, resource allocation, documentation, dissemination of information and problem-solving as central activities, surpassing their time for interpersonal and relationship-building activities. Hence, although managers generally preferred relationship-oriented leadership, the context of telework seems to force them to adopt more authoritarian and performance-oriented approaches. This is interesting considering leadership styles in telework often being treated and recommended as something that can actively be adopted (Margheritti et al., 2024; Varma et al., 2022).

4.5 Strengths and limitations

Researchers have been encouraged to adopt more qualitative approaches to deepen the understanding of the complexities of telework arrangements. While previous research has primarily focused on the employee perspective, the perspective of managers has received less attention (Lunde et al., 2022; Nayani et al., 2018). This is significant, as managers and their leadership performance are crucial to the success of teleworking (Nayani et al., 2018).

Although teleworking is common in knowledge-intensive organizations like academic institutions, it has been rarely studied in this context (Eurofound, 2022). This study addressed these gaps by using a phenomenographic approach to explore managers' experiences and perspectives on telework in academic institutions. An inductive method was used to provide a broader, less theory-driven investigation than a deductive approach would offer.

Our findings represent a variety of telework practices in academic institutions because we used a broad definition of telework by including telework performed during voluntary as well as forced work conditions, this could be considered a strength of this study. Knowledge provided by this study may be of importance when academic institutions are planning future telework strategies which are adapted to both the everyday work situation and that of a crisis. Our sample represented academic managers from various educational and scientific disciplines, from universities of different sizes and parts of Sweden. It also included an equal distribution of female and male managers.

There are however also limitations to this study. For instance, qualitative findings are difficult to generalize to other or wider groups than those being studied because experiences are individual and situated in a specific context. Further, this study was conducted in Sweden where the government's approach to COVID-19 restrictions in society generally was more liberal than in other countries (Eurofound, 2022). Consequently, Swedish academic institutions may have had more flexible homebound work solutions, e.g., with the option of being present at the workplace occasionally. This might have mitigated some of the recognized negative effects of the pandemic's homebound work, such as social isolation and limitations to autonomy. For managers, the option of workplace presence might have provided better control or insight into employee performance and wellbeing matters, although this was not seen in our findings. Hence, our findings may not be transferable to academic institutions in other countries during the pandemic.

4.6 Implications for research and practice

Overall, our findings challenge the prevailing notion of leadership in telework being easier in more self-managed organizations (Silva et al., 2019). According to existing research, managers can perceive challenges and develop reluctant attitudes toward telework if organizational resources, such as technical support and equipment, guidelines for telework agreements and leadership training for managers, are inadequate or missing (Kwon and Jeon, 2020; Silva et al., 2019). Conversely, if organizational resources are in place managers may become more prone to consider telework as important and useful for the organization (Nayani et al., 2018; Silva et al., 2019). The present study revealed a general lack of such instrumental resources for managers leading teleworkers in academic institutions. The findings also show a lack of social support to managers. Studies on academic institutions show that managers in this context often feel undervalued by their senior managers (Warren, 2017), which is also indicated by our findings. Academic managers operate in a complex organizational context where the managerial leadership structure exists in parallel with that of the academic profession. Consequently, academic managers are often seen struggling with defining their organizational role and function (Saltmarsh and Randell-Moon, 2015; Warren, 2017). Hence, leading teleworkers in academic institutions can be considered challenging, partly because of the complex organizational context. Partly, it entails an imbalance between organizational demands directed toward managers and the resources provided to fulfill employees' as well as managers' needs in telework. While previous research on telework has defined managers and their leadership as a resource in their own right (Nayani et al., 2018), few studies have examined the specific needs of managers leading teleworkers and the status of organizational resources provided to them. Further studies should pay more attention to such aspects and investigate how the character and access of organizational resources impacts managerial roles, leadership strategies and the wellbeing of managers. Researchers should also further explore and define the academic management's different roles and responsibilities, as well as the (in)congruence of those, in telework arrangements.

In practice, academic institutions need to improve their resources to managers leading teleworkers. Firstly, leadership training, such as collegial learning activities, on leadership in telework should be provided for managers. Secondly, the senior management of academic institutions should, in collaboration with managers and academic staff, discuss and formulate common guidelines for where, when and how telework should be allowed. Similarly, they need to develop specific guidelines, routines and collaboration for OHS management in telework. Further, the digital infrastructures and competences in academic institutions need to be evaluated and strengthened. Such suggestions have partly been given by other researchers (Margheritti et al., 2024; Nayani et al., 2018; Silva et al., 2019), but mainly without recommendations for collaboration between organizational levels and roles. Other than managerial levels and academic staff, the collaboration could preferably also include supporting functions like HR and IT, OHS representatives and head of teaching and research. We believe that a collaborative approach is important for creating functional telework guidelines, as it may allow consideration for the varying needs of academic managers, staff and administrative functions. It might also increase institutional members' agreement on decisions regarding telework allowance/regulations.

5 Conclusion

This study examined academic managers‘ experiences and expectations for leading teleworkers, both in traditional telework and forced homebound settings. The findings revealed that managing teleworkers requires more effort to support work and communication. Managers called for organizational policies to increase their control over telework and highlighted a lack of formal resources to meet OHS standards in telework. An increase in teleworking may require leadership changes that conflict with managers' preferred styles. In conclusion, academic institutions must provide resources tailored to managers‘ needs to effectively lead teleworkers. This includes support and guidance by the senior management regarding telework allowance, OHS management and leadership strategies. Without sufficient support, leading teleworkers could jeopardize managers' wellbeing and performance, potentially affecting institutional outcomes.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Regional Ethical Review Board in Uppsala, Sweden (Reg. no. 2020-06012). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

LW: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Software, Formal analysis, Visualization, Resources, Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Validation. EB: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. MH: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. BW: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Formal analysis.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the informants for their contribution to this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/forgp.2025.1596172/full#supplementary-material

References

Allen, T. D., Golden, T. D., and Shockley, K. M. (2015). How effective is telecommuting? Assessing the status of our scientific findings. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 16, 40–68. doi: 10.1177/1529100615593273

Alward, E., and Phelps, Y. (2019). Impactful leadership traits of virtual leaders in higher education. Online Learn. 23, 72–93. doi: 10.24059/olj.v23i3.2113

Antonacopoulou, E. P., and Georgiadou, A. (2021). Leading through social distancing: the future of work, corporations and leadership from home. Gender Work Organ. 28, 749–767. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12533

Bakker, A. B., and Demerouti, E. (2018). “Multiple levels in job demands-resources theory: implications for employee well-being and performance,” in Handbook of Wellbeing, eds. E. Diener, S. Oishi, and L. Tay (Salt Lake City, UT: DEF Publishers).

Batalheiro Ferreira, J. (2022). Exhausted and not doing enough? The productivity paradox of contemporary academia. J. Design Econ. Innovation 8, 181–191. doi: 10.1016/j.sheji.2022.05.001

Beckel, J. L. O., and Fisher, G. G. (2022). Telework and worker health and well-being : a review and recommendations for research and practice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 3879. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19073879

Brunelle, E. (2013). Leadership and mobile working: the impact of distance on the superior-subordinate relationship and the moderating effects of leadership style. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 4, 1–14.

Carillo, K., Cachat-Rosset, G., Marsan, J., Saba, T., and Klarsfeld, A. (2021). Adjusting to epidemic-induced telework: empirical insights from teleworkers in France. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 30, 69–88. doi: 10.1080/0960085X.2020.1829512

Chirico, F., Zaffina, S., Prinzio, D. i., Giorgi, R. R., Ferrari, G., Capitanelli, G. O., et al. (2021). Working from home in the context of COVID-19: a systematic review of physical and mental health effects on teleworkers. J. Health Soc. Sci. 6, 319–332. doi: 10.19204/2021/wrkn8

Cortellazzo, L., Bruni, E., and Zampieri, R. (2019). The role of leadership in a digitalized world: a review. Front. Psychol. 10:1938. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01938

De Macêdo, T. A. M., Cabral, E. L. D. S., Silva Castro, W. R., De Souza Junior, C. C., Da Costa Junior, J. F., Pedrosa, F. M., et al. (2020). Ergonomics and telework: a systematic review. Work 66, 777–788. doi: 10.3233/WOR-203224

Ebbevi, D., Von Thiele Schwarz, U., Hasson, H., Sundberg, C. J., and Frykman, M. (2021). Boards of directors' influences on occupational health and safety: a scoping review of evidence and best practices. Int. J. Workplace Health Manage. 14, 64–86. doi: 10.1108/IJWHM-10-2019-0126

Eurofound (2022). The Rise in Telework: Impact on Working Conditions and Regulations. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Eurofound. (2020). Telework and ICT-Based Mobile Work: Flexible Working in the Digital Age, New Forms of Employment Series. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Giedre Raisiene, A., Rapuano, V., and Juozapas Raišys, S. (2022). Teleworking experience of education professionals vs. management staff: challenges following job innovation. Mark. Manage. Innovations 2, 171–183. doi: 10.21272/mmi.2022.2-16

Graen, G. B., and Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership : development of leader-member exchange (LMX). Manage. Department Fac. Publ. 57:30.

Groen, A. C. B., van Triest, P. S., Coers, M., and Wtenweerde, N. (2018). Managing flexible work arrangements : teleworking and output controls. Eur. Manage. J. 36, 727–735. doi: 10.1016/j.emj.2018.01.007

Guest, G., Namey, E., and Chen, M. (2020). A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS ONE. 15:e0232076. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232076

Harris, L. (2019). Home based teleworking working and the employment relationship: managerial challenges, tensions and dilemmas. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 53, 1689–1699. doi: 10.1108/00483480310477515

Howell, J. M., and Hall-Merenda, K. E. (1999). The ties that bind: the impact of leader-member exchange, transformational and transactional leadership, and distance on predicting follower performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 84, 680–694. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.84.5.680

Kim, T., Mullins, L. B., and Yoon, T. (2021). Supervision of telework: a key to organizational performance. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 51, 263–277. doi: 10.1177/0275074021992058

Kniffin, K. M., Narayanan, J., Anseel, F., Antonakis, J., Ashford, S. P., Bakker, A. B., et al. (2021). COVID-19 and the workplace: implications, issues, and insights for future research and action. Am. Psychol. 76, 63–77. doi: 10.1037/amp0000716

Kotera, Y., and Vione, K. C. (2020). Psychological impacts of the new ways of working (NWW): a systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 1–13. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17145080

Kwon, M., and Jeon, S. H. (2020). Do leadership commitment and performance-oriented culture matter for federal teleworker satisfaction with telework programs? Rev. Public Personnel Adm. 40, 36–55. doi: 10.1177/0734371X18776049

Lembrechts, L., Zanoni, P., and Verbruggen, M. (2018). The impact of team characteristics on the supervisor's attitude towards telework: a mixed-method study. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manage. 29, 3118–3146. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2016.1255984

Lunde, L. K., Fløvik, L., Christensen, J. O., Johannessen, H. A., Finne, L. B., Jørgensen, I. L., et al. (2022). The relationship between telework from home and employee health: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 22, 1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-12481-2

Margheritti, S., Picco, E., Gragnano, A., Dell‘aversana, G., and Miglioretti, M. (2024). How to promote teleworkers' job satisfaction? the telework quality model and its application in small, medium, and large companies. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 27, 481–500. doi: 10.1080/13678868.2023.2244705

Marton, F., and Pong, W. Y. (2005). On the unit of description in phenomenography. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 24, 335–348. doi: 10.1080/07294360500284706

Nayani, R. J., Nielsen, K., Daniels, K., Donaldson-Feilder, E. J., and Lewis, R. C. (2018). Out of sight and out of mind? A literature review of occupational safety and health leadership and management of distributed workers. Work Stress 32, 124–146. doi: 10.1080/02678373.2017.1390797

Peiró, J. M., and Martínez-Tur, V. (2022). ‘Digitalized' competences. A crucial challenge beyond digital competences. Rev. Psicologia Del Trabajo y de Las Organ. 38, 189–199. doi: 10.5093/jwop2022a22

Perry, S. J., Rubino, C., and Hunter, E. M. (2018). Stress in remote work: two studies testing the demand-control-person model. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 27, 577–593. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2018.1487402

Plotnikof, M., Bramming, P., Branicki, L., Christiansen, L. H., Henley, K., Kivinen, N. N., et al. (2020). Catching a glimpse: corona-life and its micro-politics in academia. Gender Work Organ. 27, 804–826. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12481

Rohwer, E., Harth, V., and Mache, S. (2024). “The magic triangle between bed, office, couch”: a qualitative exploration of job demands, resources, coping, and the role of leadership in remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health 24:476. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-17995-z

Ruiller, C., Van Der Heijden, B., Chedotel, F., and Dumas, M. (2019). “You have got a friend”: the value of perceived proximity for teleworking success in dispersed teams. Team Perf. Manage. 25, 2–29. doi: 10.1108/TPM-11-2017-0069

Saltmarsh, S., and Randell-Moon, H. (2015). Managing the risky humanity of academic workers: risk and reciprocity in university work-life balance policies. Policy Futures Educ. 13, 662–682. doi: 10.1177/1478210315579552

Silva, C. A., Montoya, R. I. A., and Valencia, A. J. A. (2019). The attitude of managers toward telework, why is it so difficult to adopt it in organizations? Technol. Soc. 59:101133. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2019.04.009

Sjöblom, K., Mäkiniemi, J. P., and Mäkikangas, A. (2022). “I was given three marks and told to buy a Porsche”-supervisors' experiences of leading psychosocial safety climate and team psychological safety in a remote academic setting. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:12016. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191912016

Varma, A., Jaiswal, A., Pereira, V., and Kumar, Y. L. N. (2022). Leader-member exchange in the age of remote work. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 25, 219–230. doi: 10.1080/13678868.2022.2047873

Vartiainen, M., and Vanharanta, O. (2024). True nature of hybrid work. Frontiers in Organ. Psychol. 2:1448894. doi: 10.3389/forgp.2024.1448894

Warren, S. (2017). Struggling for visibility in higher education: caught between neoliberalism ‘out there' and ‘in here'-an autoethnographic account. J. Educ. Policy 32, 127–140. doi: 10.1080/02680939.2016.1252062

Keywords: telework, managers, leadership, universities, occupational health, COVID-19, interviews

Citation: Widar L, Boman E, Heiden M and Wiitavaara B (2025) Leading teleworkers in academia: managers' experiences and expectations for the future. Front. Organ. Psychol. 3:1596172. doi: 10.3389/forgp.2025.1596172

Received: 19 March 2025; Accepted: 09 June 2025;

Published: 09 July 2025.

Edited by:

José Maria Peiró, University of Valencia, SpainReviewed by:

Núria Tordera, University of Valencia, SpainDaisung Jang, University of Melbourne, Australia

Copyright © 2025 Widar, Boman, Heiden and Wiitavaara. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Linda Widar, bGluZGEud2lkYXJAdW11LnNl

Linda Widar

Linda Widar Eva Boman2

Eva Boman2 Birgitta Wiitavaara

Birgitta Wiitavaara