Abstract

Cannabinoids include the active constituents of Cannabis or are molecules that mimic the structure and/or function of these Cannabis-derived molecules. Cannabinoids produce many of their cellular and organ system effects by interacting with the well-characterized CB1 and CB2 receptors. However, it has become clear that not all effects of cannabinoid drugs are attributable to their interaction with CB1 and CB2 receptors. Evidence now demonstrates that cannabinoid agents produce effects by modulating activity of the entire array of cellular macromolecules targeted by other drug classes, including: other receptor types; ion channels; transporters; enzymes, and protein- and non-protein cellular structures. This review summarizes evidence for these interactions in the CNS and in cancer, and is organized according to the cellular targets involved. The CNS represents a well-studied area and cancer is emerging in terms of understanding mechanisms by which cannabinoids modulate their activity. Considering the CNS and cancer together allow identification of non-cannabinoid receptor targets that are shared and divergent in both systems. This comparative approach allows the identified targets to be compared and contrasted, suggesting potential new areas of investigation. It also provides insight into the diverse sources of efficacy employed by this interesting class of drugs. Obtaining a comprehensive understanding of the diverse mechanisms of cannabinoid action may lead to the design and development of therapeutic agents with greater efficacy and specificity for their cellular targets.

Introduction

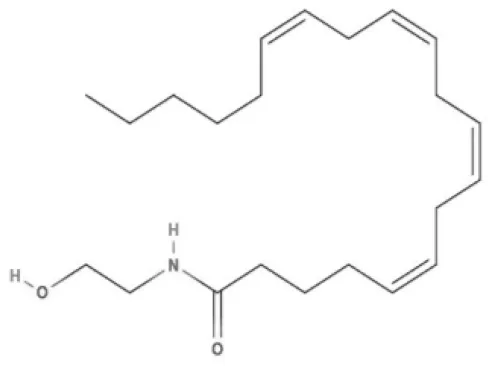

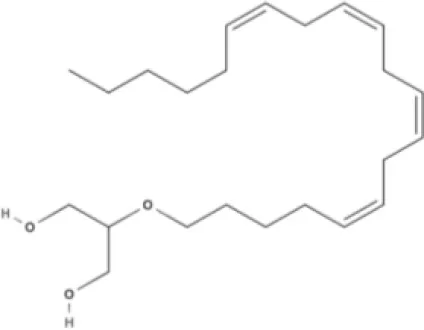

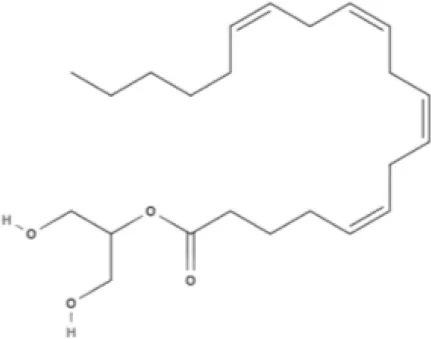

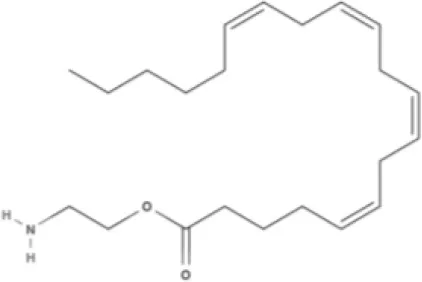

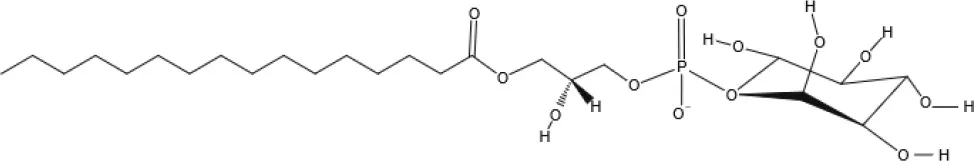

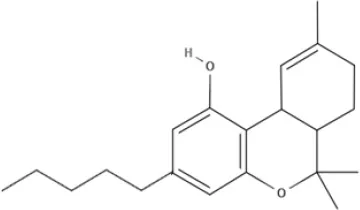

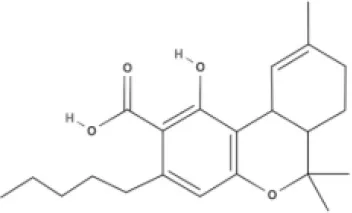

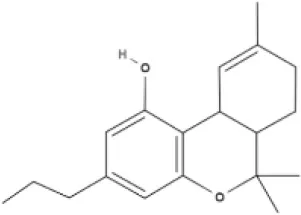

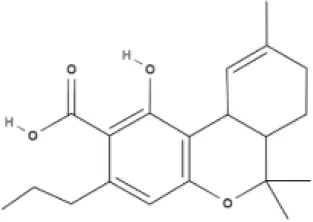

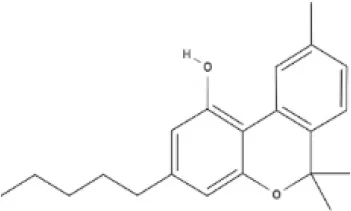

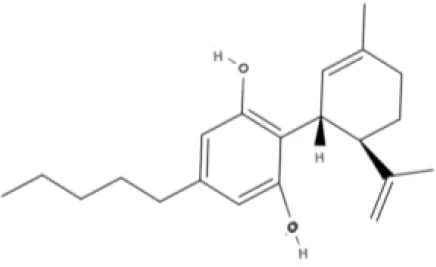

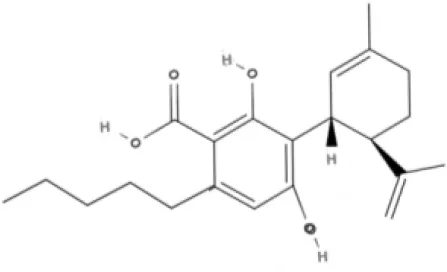

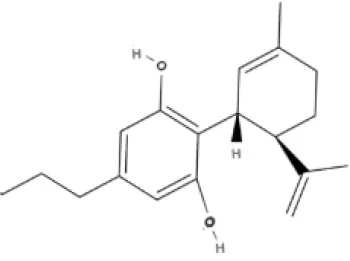

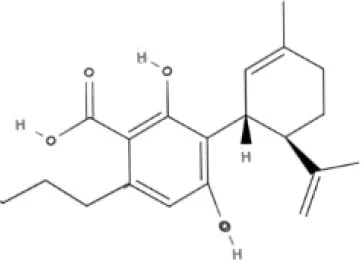

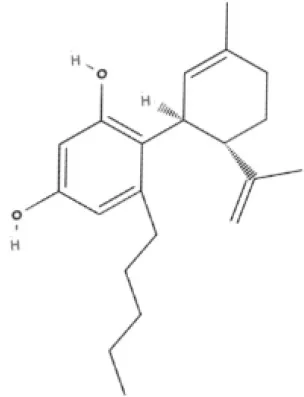

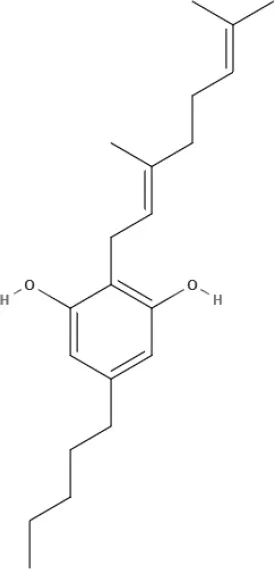

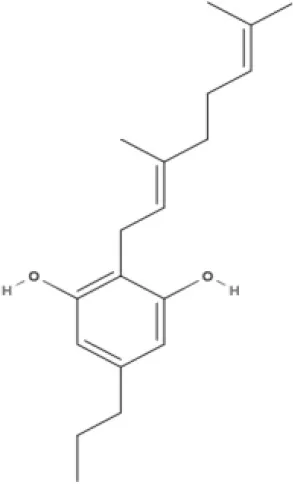

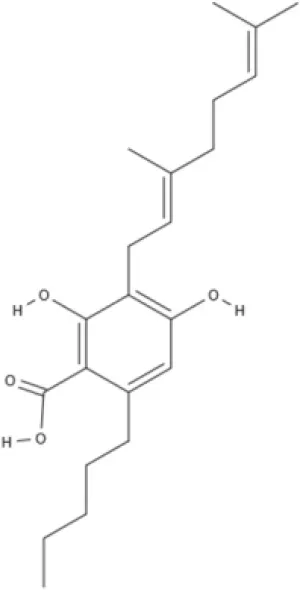

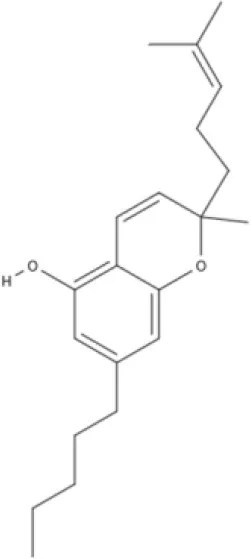

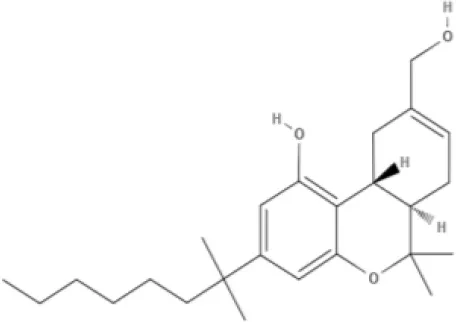

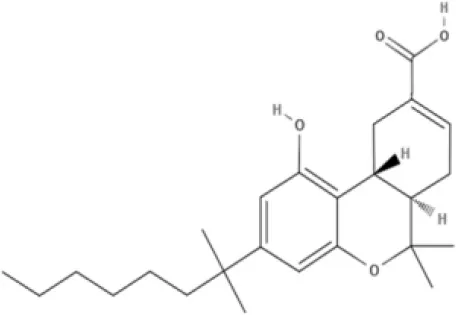

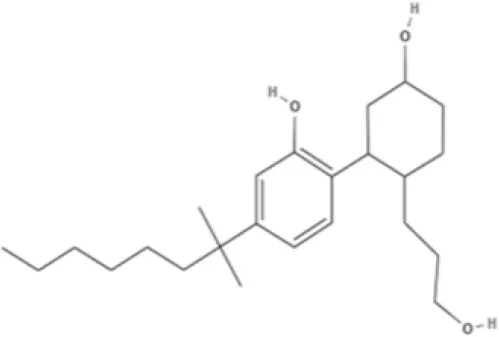

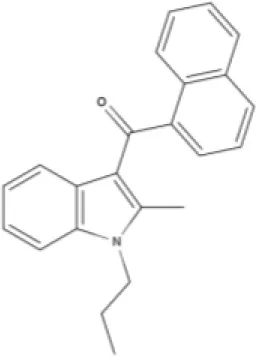

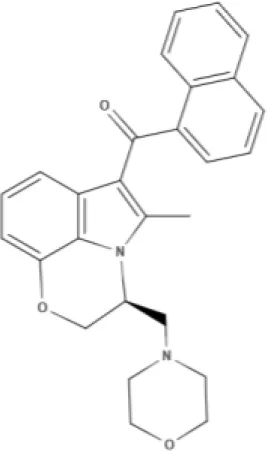

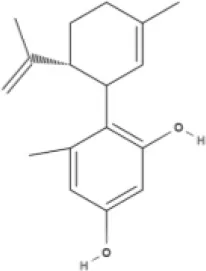

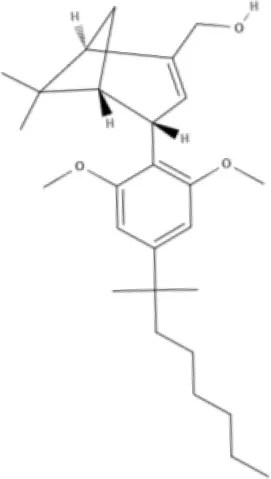

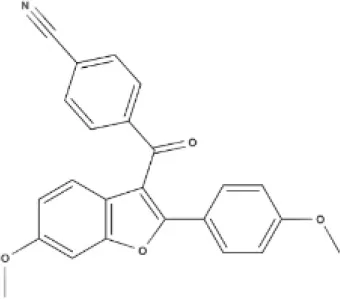

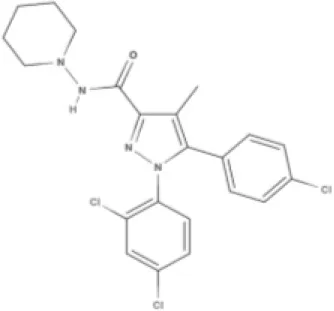

Cannabinoids are a broad and diverse class of drugs that are structurally- or functionally-related to those isolated from Cannabis (i.e., are “Cannabis-like”). Several structural classes of cannabinoid drugs have been identified, including: phytocannabinoids (related to those derived from plant material); endogenously-produced cannabinoids; and related eicosanoids that regulate vertebrate endocannabinoid signaling systems; synthetic and other types of cannabinoids (many developed seeking modulators of other signaling systems, but found to interact with the classic CB1 and/or CB2 receptors). Classical cannabinoid agonists (structures shown in Table 1) bind to and activate cannabinoid receptors 1 and 2 (CB1, CB2) that modulate signal transduction cascades to produce various physiological and pathological outcomes. The actions of cannabinoids are also regulated by the endocannabinoid system (ECS) which includes enzymes involved in synthesis, uptake and degradation of endogenous cannabinoid ligands, and the CB1 and CB2 receptors. Cannabinoid pharmacology is an active field, and new examples of cannabinoid drugs are identified regularly (Shevyrin et al., 2016) with the primary goal of discovering novel therapeutics.

Table 1

| Endocannabinoids (ECs) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

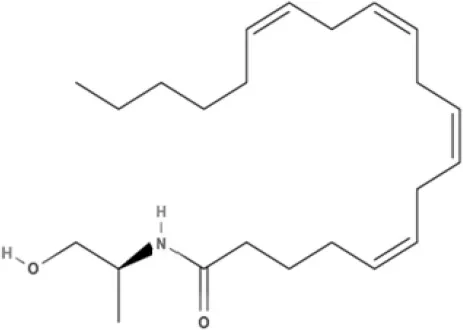

| Arachidonic acid-derived ECs | |||

AEA | Noladin Ether (2-AG ether) | 2-AG | Virodhamine |

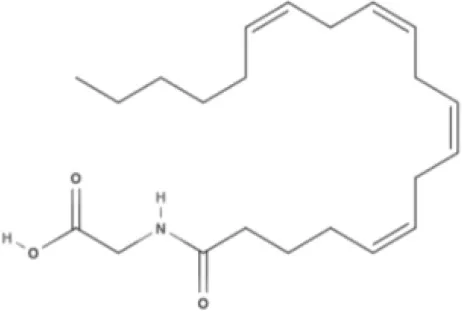

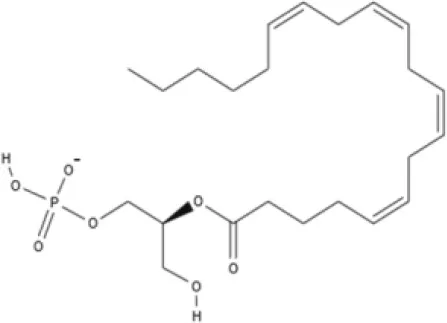

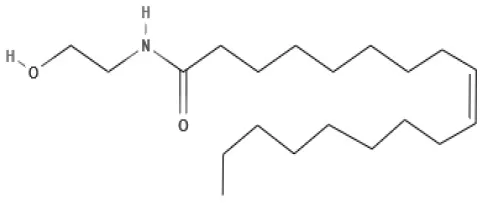

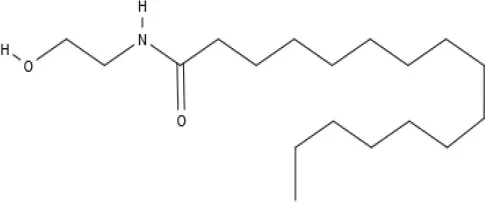

NAGly | 2A-LPA | Oleic acid-derived EC Oleoylethanolamide (OEA) | Palmitic acid-derived EC Palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) |

Other EC Lysophosphatidylinositol (LPI) | |||

| Phytocannabinoids | |||

| Tricyclic phytocannabinoids | |||

THC | THCA | THCV | THCVA |

CBN | |||

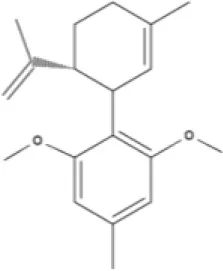

| Bicyclic phytocannabinoids | |||

CBD | CBDA | CBDV | CBDVA |

AbCBD | |||

| Other phytocannabinoids | |||

CBG | CBGV | CBGA | CBC |

| Synthetic cannabinoids | |||

| Dibenzopyran derivatives (THC related compounds) | Cyclohexylphenol derivatives | ||

HU-210 | Ajulemic acid | CP55940 | |

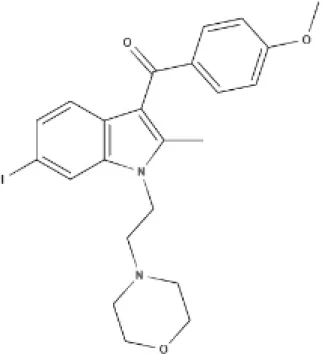

| Aminoalkylindoles | |||

JWH-015 | WIN | AM630 | |

| Synthetic analogs of ECs | |||

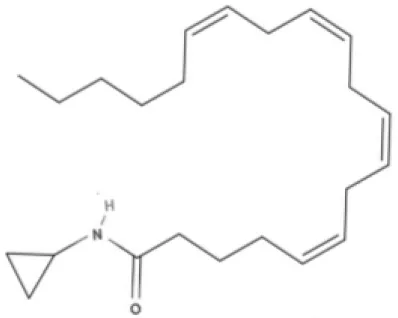

MA | ACPA | ||

| Other synthetic cannabinoids | |||

O-1918 | O-1602 | HU-308 | LY320135 |

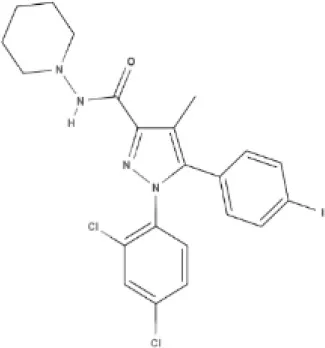

SR141716A | AM251 | ||

Structures of cannabinoids reviewed, summarized by class.

AEA, arachidonoyl ethanolamide or anandamide; 2-AG, 2-arachidonoyl glycerol; OEA, oleoylethanolamine; PEA, palmitoylethanolamide; NAGly, N-arachidonoyl glycine; LPI, lysophosphatidylinositol; 2A-LPA, 2-arachidonoyl lysophosphatidic acid; THC, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol; THCA, THC acid; THCVA, tetrahydrocannabivarin acid; CBD, cannabidiol; CBDA, cannabidiol acid; CBDV, cannabidivarin; CBDVA, cannabidivarin acid; CBN, cannabinol; CBC, cannabichromene; CBG, cannabigerol; CBGV, cannabigerovarin; CBGA, cannabigerol acid; AbCBD, abnormal cannabidiol; WIN, WIN55212-2; MA, methanandamide; ACPA, arachidonylcyclopropylamide.

It is now clear that, in addition to the classic CB1 and CB2 receptors, cannabinoid-related agents interact with a spectrum of macromolecular targets, including: other receptors; ion channels; transporters; enzymes and; protein- and non-protein cellular structures. Evidence for cannabinoid modulation of these targets has already been the subject of excellent reviews (Kreitzer and Stella, 2009; De Petrocellis and Di Marzo, 2010; Pertwee, 2010). The purpose of this review is to examine current studies that focus on how off-receptor targets mediate the effects of classical cannabinoids in the CNS and in cancer. Cannabinoids that interact with cannabinoid receptors in an allosteric manner (allosteric modulators) are outside of the scope of this review but have been recently reviewed elsewhere (Busquets Garcia et al., 2016; Janero and Thakur, 2016; Khurana et al., 2017; Nguyen et al., 2017).

Active constituents of Cannabis produce CNS effects, and the endocannabinoid signaling system was discovered in CNS, therefore cannabinoid effects on neuronal activity have been more thoroughly and efficiently studied than in more peripheral processes like cancer. Although CB1 and/or CB2 receptors are known to be expressed in some cancers (Sarfaraz et al., 2008), their levels vary and may be either up- or down regulated (Bifulco et al., 2001; Begum et al., 2005). Variable receptor expression suggests that cannabinoid effects in cancer are more likely to involve non-receptor mechanisms than in CNS, making the system a promising area to examine for novel targets. Thus, focusing on both CNS and cancer will allow established central and emerging peripheral effects that are not mediated by CB1 or CB2 to be compared and contrasted, in order to appreciate common and divergent mechanisms that are involved. This comparison may also reveal important cannabinoid targets in the CNS and cancer that can form a basis for inquiry in other organ systems. In addition, awareness of non-cannabinoid receptor targets of cannabinoids may lead to the development of drugs with greater efficacy and specificity for their targets.

Roles of cannabinoids and the cannabinoid receptors in the CNS

CB1 receptors are abundant in CNS and expressed in brain at consistently high densities across vertebrate species within which levels have been measured (~2,000 fmol/mg protein, e.g., Pertwee, 1997; Soderstrom et al., 2000; Soderstrom and Johnson, 2001). Although expressed at much lower levels than CB1, CB2 receptors also play clear roles in reward-related CNS activity (Zhang et al., 2014) and immune responses (Cabral et al., 2008). High-level CB1 expression (approaching that of amino acid transmitter receptors) may have contributed to delayed appreciation of central cannabinoid effects produced following interaction with other cellular macromolecules. This is because the magnitude of non-receptor-mediated effects may be small relative to those that follow activation of the more abundant CB1 receptors. This is of therapeutic importance as when using drugs to treat disease often “less is more” and more modest indirect effects may be adequate to mitigate disease processes while avoiding toxicity. Thus, cannabinoid-related agents with targets independent of CB1 and CB2 receptors are currently being effectively employed or evaluated for management of a variety of CNS disorders (McPartland et al., 2014). The non-CB1/CB2 CNS-relevant targets reviewed here, along with the cannabinoid ligands that interact with them, are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2

| Target | Target type | Ligand | Ligand type | Activity | Potency (EC50, nM) | System | Assay | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-HT1A | Receptor | CBD | Phyto | Agon | NA | Rat BNST | Anxiolysis | Gomes et al., 2011 |

| 5-HT1A | Receptor | CBD | Phyto | Agon | ~3,000 | LN 231 | Cell viab. | Ward et al., 2014 |

| 5-HT1A | Receptor | CBD | Phyto | Agon | NA | CHO | Cyclase inhib. | Russo et al., 2005 |

| 5-HT1A | Receptor | CBD | Phyto | Agon | ~1 μg/kg | Rat | Gaping | Rock et al., 2014 |

| 5-HT1A | Receptor | CBD | Phyto | Agon | NA | CHO | GTPγS | Russo et al., 2005 |

| 5-HT1A | Receptor | CBD | Phyto | Agon | NA | Mouse | Panic | Twardowschy et al., 2013 |

| 5-HT1A | Receptor | CBD | Phyto | Agon | NA | Rat MFB | Plus maze | Fogaça et al., 2014 |

| 5-HT1A | Receptor | CBD | Phyto | Antag | NA | Rat | ICSS | Katsidoni et al., 2013 |

| 5-HT1A | Receptor | CBD | Phyto | Ligand | NA | CHO | Lig. displ. | Russo et al., 2005 |

| 5-HT3 | Receptor | AEA | Endo | Antag | 190 | Rat NDG | Cat. current | Fan, 1995 |

| 5-HT3 | Receptor | AEA | Endo | NCAnt | 129 | Rat NDG | Cat. current | Barann et al., 2002 |

| 5-HT3 | Receptor | CP55940 | Syn | Antag | 94 | Rat NDG | Cat. current | Fan, 1995 |

| 5-HT3 | Receptor | CP55940 | Syn | NCAnt | 648 | Rat NDG | Cat. current | Barann et al., 2002 |

| 5-HT3 | Receptor | JWH-015 | Syn | NCAnt | 147 | Rat NDG | Cat. current | Barann et al., 2002 |

| 5-HT3 | Receptor | LY320135 | Syn | NCAnt | 523 | Rat NDG | Cat. current | Barann et al., 2002 |

| 5-HT3 | Receptor | THC | Phyto | NCAnt | 38.4 | Rat NDG | Cat. current | Barann et al., 2002 |

| 5-HT3 | Receptor | WIN | Syn | Antag | 310 | Rat NDG | Cat. current | Fan, 1995 |

| 5-HT3 | Receptor | WIN | Syn | NCAnt | 104 | Rat NDG | Cat. current | Barann et al., 2002 |

| A2A | Receptor | CBD | Phyto | Agon | NA | EOC-20 | Cell prolif. | Carrier et al., 2006 |

| AMPA | Receptor | AEA | Endo | Antag | 160–240 | X. oocytes | Cat. current | Akinshola et al., 1999 |

| ANA trans | Transporter | CBD | Phyto | Antag | 25,300 | leukemia Cx | ANA uptake | De Petrocellis et al., 2011 |

| ANA trans | Transporter | CBG | Phyto | Antag | 11,300 | leukemia Cx | ANA uptake | De Petrocellis et al., 2011 |

| DAGLα | Enzyme | THCA | Phyto | Antag | 27,300 | COS-7 | 2-AG met | De Petrocellis et al., 2011 |

| δOP | Receptor | SR141716A | Syn | NCAnt | NA | CB1 KO | GTPγS | Zádor et al., 2014 |

| ENT1 | Transporter | CBD | Phyto | Antag | ~250 | EOC-20 | Nucleoside | Carrier et al., 2006 |

| ENT1 | Transporter | THC | Phyto | Antag | ~50 | EOC-20 | Nucleoside | Carrier et al., 2006 |

| FAAH | Enzyme | CBD | Phyto | Antag | 15,200 | Rat brain | ANA met | De Petrocellis et al., 2011 |

| GABAA B2 | Receptor | 2-AG | Endo | Agon | 1,100 | X. oocytes | Cl− current | Sigel et al., 2011 |

| GABAA B2 | Receptor | 2-AG | Endo | Antag | NA | HEK293 | Cl− current | Golovko et al., 2014 |

| GABAA B2 | Receptor | CP55940 | Syn | Antag | NA | HEK293 | Cl− current | Golovko et al., 2014 |

| Glycine | Receptor | 2-AG | Endo | Antag | NA | HCX neurons | Cl− current | Lozovaya et al., 2005 |

| Glycine | Receptor | AEA | Endo | Agon | 230–318 | Rat VTA | Cl− current | Hejazi et al., 2006 |

| Glycine | Receptor | AEA | Endo | Antag | 300 | HCX neurons | Cl− current | Lozovaya et al., 2005 |

| Glycine | Receptor | THC | Phyto | Agon | 115 | Rat VTA | Cl− current | Hejazi et al., 2006 |

| Glycine | Receptor | WIN | Syn | Antag | 300 | HCX neurons | Cl− current | Lozovaya et al., 2005 |

| Glycine α1 | Receptor | AEA | Endo | Antag | 38 | HEK293 | Cl− current | Yang et al., 2008 |

| Glycine α2 | Receptor | HU210 | Syn | Antag | 90 | HEK293 | Cl− current | Yang et al., 2008 |

| Glycine α2 | Receptor | HU308 | Syn | Antag | 1,130 | HEK293 | Cl− current | Yang et al., 2008 |

| Glycine α2 | Receptor | NAGly | Endo | Antag | 3,030 | HEK293 | Cl− current | Yang et al., 2008 |

| Glycine α2 | Receptor | WIN | Syn | Antag | 220 | HEK293 | Cl− current | Yang et al., 2008 |

| GLYT1a | Transporter | AEA | Endo | Agon | 30,000 | X. oocytes | Gly trans | Pearlman et al., 2003 |

| GPR119 | Receptor | OEA | Endo | Agon | 3,200 | Yeast | LacZ | Overton et al., 2006 |

| GPR119 | Receptor | PEA | Endo | Agon | >10,000 | Yeast | LacZ | Overton et al., 2006 |

| GPR18 | Receptor | AbCBD | Syn | Agon | ~0.3 μg/kg | RVLM | BP | Penumarti and Abdel-Rahman, 2014b |

| GPR18 | Receptor | AbCBD | Syn | Agon | 836 | HEC-1B | MAPK act | McHugh et al., 2012 |

| GPR18 | Receptor | ACPA | Syn | Agon | 1,350 | HEC-1B | MAPK act | McHugh et al., 2012 |

| GPR18 | Receptor | AM251 | Syn | Antag | 9,640 | HEC-1B | MAPK act | McHugh et al., 2012 |

| GPR18 | Receptor | AEA | Endo | Agon | 383 | HEC-1B | MAPK act | McHugh et al., 2012 |

| GPR18 | Receptor | CBD | Phyto | Antag | 5,110 | HEC-1B | MAPK act | McHugh et al., 2012 |

| GPR18 | Receptor | NAGly | Endo | Agon | NA | CHO | Ca++ | Kohno et al., 2006 |

| GPR18 | Receptor | NAGly | Endo | Agon | ~30 | CHO | Cyclase inhib. | Kohno et al., 2006 |

| GPR18 | Receptor | NAGly | Endo | Agon | 45 | HEC-1B | MAPK act | McHugh et al., 2012 |

| GPR18 | Receptor | O-1602 | Syn | Agon | 65 | HEC-1B | MAPK act | McHugh et al., 2012 |

| GPR18 | Receptor | O-1918 | Syn | Antag | ~0.4 μg/kg | RVLM | BP | Penumarti and Abdel-Rahman, 2014b |

| GPR18 | Receptor | THC | Phyto | Agon | 960 | HEC-1B | MAPK act | McHugh et al., 2012 |

| GPR35 | Receptor | 2A-LPA | Endo | Agon | ~100 | HEK293 | Ca++ | Oka et al., 2010 |

| GPR55 | Receptor | 2-AG | Endo | Agon | 3 | HEK293 | GTPγS | Ryberg et al., 2007 |

| GPR55 | Receptor | AbCBD | Phyto | Agon | 2,500 | HEK293 | GTPγS | Ryberg et al., 2007 |

| GPR55 | Receptor | AM251 | Syn | Agon | 39 | HEK293 | GTPγS | Ryberg et al., 2007 |

| GPR55 | Receptor | AEA | Endo | Agon | 18 | HEK293 | GTPγS | Ryberg et al., 2007 |

| GPR55 | Receptor | CBD | Phyto | Antag | NA | HEK293 | GTPγS | Ryberg et al., 2007 |

| GPR55 | Receptor | CP55940 | Syn | Agon | 5 | HEK293 | GTPγS | Ryberg et al., 2007 |

| GPR55 | Receptor | HU210 | Syn | Agon | 26 | HEK293 | GTPγS | Ryberg et al., 2007 |

| GPR55 | Receptor | LPI | Endo | Agon | 200 | HEK293 | ERK | Oka et al., 2007 |

| GPR55 | Receptor | Noladin Ether | Endo | Agon | 10 | HEK293 | GTPγS | Ryberg et al., 2007 |

| GPR55 | Receptor | O-1602 | Syn | Agon | 13 | HEK293 | GTPγS | Ryberg et al., 2007 |

| GPR55 | Receptor | OEA | Endo | Agon | 440 | HEK293 | GTPγS | Ryberg et al., 2007 |

| GPR55 | Receptor | PEA | Endo | Agon | 4 | HEK293 | GTPγS | Ryberg et al., 2007 |

| GPR55 | Receptor | THC | Phyto | Agon | 8 | HEK293 | GTPγS | Ryberg et al., 2007 |

| GPR55 | Receptor | Virodhamine | Endo | Agon | 12 | HEK293 | GTPγS | Ryberg et al., 2007 |

| κOP | Receptor | SR141716A | Syn | InvAg | NA | CB1 KO | GTPγS | Zádor et al., 2015 |

| MAGL | Enzyme | CBG | Phyto | Antag | 95,700 | COS | 2-AG met | De Petrocellis et al., 2011 |

| MAGL | Enzyme | THCA | Phyto | Antag | 46,000 | COS | 2-AG met | De Petrocellis et al., 2011 |

| μOP | Receptor | Noladin Ether | Endo | NCAnt | NA | CB1 KO | GTPγS | Zádor et al., 2012 |

| μOP | Receptor | SR141716A | Syn | Antag | NA | CB1 KO | GTPγS | Cinar and Szücs, 2009 |

| μOP | Receptor | THC | Phyto | Agon | NA | Rat in vivo | Hot plate | Tulunay et al., 1981 |

| Na+ channel | Ion Channel | Ajulemic acid | Syn | Antag | ~3,000 | HEK293 | Na+ current | Foadi et al., 2014 |

| nAChR a4β2 | Receptor | AEA | Endo | Antag | NA | SH-EP1 | Na+ current | Spivak et al., 2007 |

| nAChR α7 | Receptor | 2-AG | Endo | Antag | 118 | X. oocytes | Na+ current | Oz et al., 2004 |

| nAChR α7 | Receptor | AEA | Endo | Antag | 30 | X. oocytes | Na+ current | Oz et al., 2003 |

| nAChR α7 | Receptor | CBD | Phyto | Antag | 11,300 | X. oocytes | Na+ current | Mahgoub et al., 2013 |

| nAChR α7 | Receptor | MA | Syn | Antag | ~1 μmol/kg | Anesth. Rat | HR | Baranowska et al., 2008 |

| NCX1 | Transporter | AEA | Endo | Antag | 4,700 | Rat myocytes | Na+/Ca++ | Kury et al., 2014 |

| NMDA | Receptor | AEA | Endo | Agon | NA | Rat ICV | BP | Malinowska et al., 2010 |

| NMDA | Receptor | AEA | Endo | Agon | NA | Rat HCX | Ca++ current | Yang et al., 2014 |

| TRPA1 | Ion Channel | AM251 | Syn | Agon | 10,000 | CHO | [Ca++]i | Patil et al., 2011 |

| TRPA1 | Ion Channel | CBD | Phyto | Agon | 110 | HEK293 | [Ca++]i | De Petrocellis et al., 2011 |

| TRPA1 | Ion Channel | CBG | Phyto | Agon | 700 | HEK293 | [Ca++]i | De Petrocellis et al., 2011 |

| TRPA1 | Ion Channel | THC | Phyto | Agon | 230 | HEK293 | [Ca++]i | De Petrocellis et al., 2011 |

| TRPM8 | Ion Channel | CBD | Phyto | Antag | 60 | HEK293 | [Ca++]i | De Petrocellis et al., 2011 |

| TRPM8 | Ion Channel | CBG | Phyto | Antag | 160 | HEK293 | [Ca++]i | De Petrocellis et al., 2011 |

| TRPM8 | Ion Channel | THC | Phyto | Antag | 160 | HEK293 | [Ca++]i | De Petrocellis et al., 2011 |

| TRPV1 | Ion Channel | AM251 | Syn | Agon | 10,000 | CHO | [Ca++]i | Patil et al., 2011 |

| TRPV1 | Ion Channel | AM630 | Syn | Agon | 10,000 | CHO | [Ca++]i | Patil et al., 2011 |

| TRPV1 | Ion Channel | CBD | Phyto | Agon | 1,000 | HEK293 | [Ca++]i | De Petrocellis et al., 2011 |

| TRPV1 | Ion Channel | CBG | Phyto | Agon | 1,300 | HEK293 | [Ca++]i | De Petrocellis et al., 2011 |

| TRPV2 | Ion Channel | CBD | Phyto | Agon | 1,250 | HEK293 | [Ca++]i | De Petrocellis et al., 2011 |

| TRPV2 | Ion Channel | THC | Phyto | Agon | 650 | HEK293 | [Ca++]i | De Petrocellis et al., 2011 |

Summary of CNS-relevant non-cannabinoid receptor targets.

ICSS, intracranial self stimulation; HR, heart rate; BP, blood pressure; MAPK act, MAPK activation; Cat. current, Cation current; AEA, arachidonoyl ethanolamide or anandamide; MA, methanandamide; CBD, cannabidiol; CBG, cannabigerol; Agon, agonist; NCAnt, non-competitive antagonist; Antag, antagonist; NDG, nodose ganglion; Cx, culture; Lig. displ., displacement of ligand binding; MFB, medial forebran bundle.

Effects of cannabinoids and the cannabinoid receptors on cancer

Both CB1 and CB2 receptors, and their endogenous ligands, are expressed in a variety of peripheral organs, including; the GI tract, liver, bone, reproductive system, skin, and the immune system. Peripheral endocannabinoid signaling also regulates many aspects of human pathophysiology, including cancer. Cannabinoid agonists are used as palliative therapy for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, and they may also be beneficial in the treatment of cancer-related pain. Evidence from both in vitro and in vivo studies established the efficacy of these compounds in reducing tumor growth and proliferation (Ladin et al., 2016). Much of this efficacy is attributable to interaction with targets other than the classic CB1/CB2 receptors. Therefore, we focus on how off-receptor targets mediate cannabinoid effects on cancer. The cancer-related off-receptor targets reviewed here, and the cannabinoid ligands that interact with them, are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3

| Cancer type | Cell line | Drug | Target | Activity | Cellular response | Assay | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colon and colorectal cancer | HT29 | AEA | FAAH | Substrate | Reduced cell death | Adherent cell count | Patsos et al., 2005 |

| HCA7 | AEA | COX-2 | Substrate | Cell death | Adherent cell count | Patsos et al., 2005 | |

| HCT116 Caco-2 | CBG | TRPM8 | Antagonist | Apoptosis | • Caspase 3/7 activity • DNA fragmentation | Borrelli et al., 2014 | |

| SW480 HT29 | WIN | Phosphatase | Increased expression, Activation | Apoptosis | • PARP cleavage • TUNEL | Sreevalsan and Safe, 2013 | |

| SW480 | WIN | Phosphatase | Increased expression | Reduced proliferation, Apoptosis | • Cell number • PARP cleavage • Caspase 3 | Sreevalsan et al., 2011 | |

| Brain tumor: | |||||||

| Glioma | Ge227 Ge258 U87 U251 | AEA | TRPV1 | Agonist | Apoptosis | DNA fragmentation | Contassot et al., 2004b |

| U87 | CBD | TRPV2 | Agonist, Increased expression | Increased chemotherapeutic sensitivity, Inhibition of cell migration | • MTT (cell viability) • Chemotaxis (cell migration) | Nabissi et al., 2013 | |

| H4 | MA | COX-2 | Increased expression | Apoptosis | • Caspase • PARP cleavage | Eichele et al., 2006 | |

| GSC patient derived | CBD | TRPV2 | Agonist, Increased expression | Increased differentiation, Autophagy, Reduced proliferation | • Flow (differentiation) • LC3I, LC3II (autophagy) • MTT (proliferation) | Nabissi et al., 2015 | |

| Neuroblastoma | N1EE-115 | AEA | FAAH | Substrate | Reduced cell death | • MTT | Hamtiaux et al., 2011 |

| Prostate | LNCaP | WIN | Phosphatase | Increased expression | Reduced proliferation, Apoptosis | • Cell number • PARP cleavage • Caspase 3 | Sreevalsan et al., 2011 |

| Non-melanoma skin cancer | JWF2 | AEA | COX-2 | Substrate | Apoptosis | • PARP cleavage • Caspase 3 | Kuc et al., 2012 |

| JWF2 | AEA | FAAH | Substrate | Reduced apoptosis | • PARP cleavage • Caspase 3 • TUNEL | Kuc et al., 2012 | |

| Lung cancer | A549 H460 | CBD | PPAR⋎ COX-2 | Activation of PPAR⋎ & COX-2, Increased COX-2 expression | Apoptosis, Reduced tumor growth (xenograft) | DNA fragmentation | Ramer et al., 2013 |

| Murine lung cancer | L1C2 | MA | COX-2 | Expression and activity | Increased tumor growth | Tumor volume | Gardner et al., 2003 |

| HeLa | MA | PPAR⋎ COX-2 | Activation of PPAR⋎ & COX-2, Increased COX-2 expression | Apoptosis | DNA fragmentation | Eichele et al., 2009 | |

| Cervical cancer | HeLa Caski CC299 | AEA | TRPV1 | Agonist | Apoptosis | • subG0/G1 • Caspase 7 cleavage | Contassot et al., 2004a |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | Mc-ChA-1 | AEA | GPR55 | Activation | Apoptosis | Annexin V | DeMorrow et al., 2007 |

| Multiple myeloma | RPMI, U266 | CBD | TRPV2 | Agonist | Necrosis, Cell death, Increased therapeutic sensitivity | • Propidium iodide (necrosis) • MTT (cell death) | Morelli et al., 2014 |

Summary of cancer-relevant non-cannabinoid receptor targets.

AEA, arachidonoyl ethanolamide or anandamide; FAAH, fatty acid amide hydrolase; CBG, cannabigerol; TRPM8, transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily M member 8; WIN, WIN55212-2; CBD, cannabidiol; MA, methanandamide; PPAR⋎, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; TRPV1, TRPV2, transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V members 1 and 2; GPR55, G protein-coupled receptor 55; MTT, 3-(4,5-dimethythiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide; PARP, Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase; TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling.

Non-CB1/CB2 receptor targets

Deorphanized G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) in CNS and cancer

Four former orphan GPCRs (GPR55, GPR18, GPR119, and GPR35) have now been clearly established to transduce effects of a subset of both naturally-occurring and synthetic cannabinoid compounds. The available data demonstrate that cannabinoids directly activate these four GPCRs in the CNS, and they also activate GPR55 in cancer.

GPR55 in CNS

The most well-characterized of the deorphanized GPCRs, GPR55 (Ryberg et al., 2007), is expressed most highly in brain, adrenal gland, and digestive tract (although at reportedly low levels relative to that of CB1). When expressed in HEK293 cells, specific binding of the synthetic CB1 agonist CP55940 is observed, but not of the CB1/CB2 synthetic agonist WIN55212-2. Interestingly, a very small amount of specific GPR55 binding was observed using 50 nM of the CB1-selective antagonist/inverse agonist SR141716A (SR).

Using the same HEK293 cell line for GTPγS functional assays, the endogenous agonist 2-arachidonylglyerol (2-AG) potently activates GPR55 (EC50 = 3 nM), although virodhamine (EC50 = 12 nM) is a more complete agonist with about 50% greater efficacy. Notably, in a separate assay of intracellular calcium release, 2-AG and virodhamine showed no GPR55 agonism, suggesting this receptor is subject to agonist-dependent functional selectivity (Lauckner et al., 2008). Other potent agonists discovered in this initial screen of GPR55 efficacy include; palmitoylethanolamide (PEA), CP55940, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), noladin ether, and anandamide with EC50s of 4, 5, 8, 10, and 18 nM respectively, and efficacies similar to that of 2-AG. Interestingly, the non-psychoactive phytocannabinoid cannabidiol (CBD) was found to antagonize GPR55 activity at physiologically relevant concentrations.

GPR55 primarily couples through the relatively obscure Gα13. This interesting G-protein activates a cascade involving RhoA that, among other effects, ultimately alters actin polymerization and stability, implicating GPR55 signaling in processes related to neuronal morphology (Worzfeld et al., 2008). This potential role is further supported by effects to promote neurite retraction (Obara et al., 2011). More recently, evidence in transfected HEK293 cells indicates that signaling through Gq also occurs (Lauckner et al., 2008).

In ERK activation assays with GPR55-expressing HEK293 cells, lysophosphatidylinositol (LPI) is implicated as an important endogenous agonist (Oka et al., 2007). Notably, 2-AG and virodhamine were not effective in stimulating ERK in transfected HEK293 cells, possibly indicating ligand-dependent functional selectivity for different signal transduction pathways. LPI was also found to dose-dependently increase intracellular calcium in these cells with an EC50 ~ 1 μM, an effect possibly related to GPR55 activation of Gq. System-dependent efficacy of GPR55 signaling may also involve interaction with other receptors including CB1. GPR55 and CB1 have been shown to heterodimerize within rat and macaque striatum, possibly related to a role in motor behaviors. When co-expressed in HEK293 cells, CB1 and GPR55 antagonize respective agonist effects to promote ERK1/2 activation (Martínez-Pinilla et al., 2014).

The physiological significance of GPR55 expression in brain remains an open question; although, some evidence indicates a role in controlling ingestive behaviors (reviewed by Liu et al., 2015). A role in promoting appetite makes sense as it has been reported that GPR55 regulates peripheral metabolism and energy homoeostasis (reviewed by Simcocks et al., 2014). Deletion of GPR55 in mice has subtle effects on motor coordination, but it has shown no significant effect on several learning and memory tests, in contrast to the role of CB1 signaling, and despite dense GPR55 expression in hippocampus, striatum, and cortex (Wu et al., 2013). Spinal cord expression of GPR55 is upregulated in a chronic constriction injury model of neuropathic pain; this suggests that it may mediate some of the analgesic effects of N-arachidonoyl-serotonin (AA-5-HT, Malek et al., 2016). GPR55 activation by some agonists increases calcium release from intraneuronal stores and inhibits M-type potassium current, both tending to promote neuronal activity (Lauckner et al., 2008). These effects may be important in the context of CBD's ability to antagonize the receptor, as this non-psychoactive phytocannabinoid has recently been shown effective for the treatment of Dravet syndrome, a formerly intractable form of childhood epilepsy (Devinsky et al., 2017). Whether the efficacy of CBD in this syndrome involves GPR55 antagonism, or perhaps, involves some combination of the many other established targets of this drug (see Table 2) remains to be resolved. Other evidence for potential roles for GPR55 signaling includes: distinct expression in rod cells of primate retina suggesting a role in low-light vision (Bouskila et al., 2013) and; expression in microglia that, following LPI activation, acts to protect hippocampal neurons from excitotoxicity (Kallendrusch et al., 2013).

GPR55 in cancer

Despite the numerous studies illuminating the physiological functions of GPR55 in the CNS described above (section GPR55 in CNS), limited information is available about the role of this receptor in cancer. GPR55 is expressed in different cancer cell types raising the possibility that it may be a target for cancer chemotherapeutic agent development (reviewed by Falasca and Ferro, 2016). Much of the research conducted thus far indicates that GPR55 promotes tumor formation. GPR55 expression was examined in human tumor biopsy samples from breast, pancreatic, and glioblastoma patients (Andradas et al., 2011). In this study, high levels of GPR55 were strongly correlated with the aggressiveness of the malignancy. Additional evidence for GPR55-promotion of malignancy includes; (1) elevated levels of its endogenous ligand lysophosphatidylinositol (LPI) in ovarian cancers (Xiao et al., 2001) and; (2) exogenous LPI promotion of proliferation and migration of various cancer cell lines (Ford et al., 2010; Piñeiro et al., 2011). However, when GPR55 is activated by the endocannabinoid, AEA, cholangiocarcinoma cell survival is inhibited. AEA induces cholangiocarcinoma cell apoptosis by recruiting Fas death receptors into lipid rafts and activating the JNK signaling pathway (DeMorrow et al., 2007; Huang et al., 2011). Genetic disruption of GPR55 receptor expression using shRNA blocked the antiproliferative effects of AEA in vitro and in vivo (Huang et al., 2011). Of note, AEA-induced cell death was not reversed in the presence of CB1- (SR141716A) or CB2- (SR144528) selective antagonists although each cannabinoid receptor was expressed (DeMorrow et al., 2007). These findings suggest that AEA elicits antiproliferative effects on cholangiocarcinoma that are GPR55-dependent and CB receptor-independent. Other deorphanized GPCRs, including GPR18 and GPR35, have been identified as modulators of tumorigenesis (Okumura et al., 2004; Qin et al., 2011); however, the role of cannabinoid ligands in these systems is unclear. Examination of the deorphanized cannabinoid receptors in cancer will provide greater insight into their impact on tumor development and progression. In addition, determining whether classical cannabinoids mediate their effects through the deorphanized receptors will shed light on mechanisms of their antitumor activity.

GPR18 in CNS

Interestingly, microglia migration is stimulated by activation of a second formerly orphan cannabinoid-related receptor, GPR18 (McHugh et al., 2010). This Gi/o-coupled receptor was originally reported to be highly-expressed in testes and spleen (Gantz et al., 1997); yet, it clearly is also functional within brainstem (Penumarti and Abdel-Rahman, 2014b). GPR18 is activated by N-arachidonoyl glycine (NAGly, Kohno et al., 2006) that is a product of anandamide metabolism (Aneetha et al., 2009; Bradshaw et al., 2009). It is also activated by abnormal cannabidiol (abn-CBD) that, when infused into regions of the brainstem, causes reduction in blood pressure in a manner that involves nitric oxide synthase and adiponectin signaling (Penumarti and Abdel-Rahman, 2014a). As with GPR55 discussed above (section GPR55 in CNS), GPR18 receptor expression is upregulated following spinal cord injury; this suggests that it may mediate some of the analgesic effects of N-arachidonoyl-serotonin (AA-5-HT, Malek et al., 2016). Notably, the principal active constituent of Cannabis, THC, is a potent agonist of GPR18 when expressed in HEK293 cells (McHugh et al., 2012). The lesser Cannabis constituent, CBD, along with synthetic CB agonists CP55940 and WIN55212-2, have no activity at physiologically-relevant concentrations. Potent GPR18 activation by THC and NAGly has been suggested to underlie efficacy to resolve inflammatory pain (Burstein et al., 2011; McHugh et al., 2014; Crowe et al., 2015). Some controversy about GPR18 signal transduction was raised when NAGly failed to inhibit Ca++ currents following heterologous expression and agonist stimulation in rat superior cervical ganglion neurons (Lu et al., 2013). Whether this is a special case of system-dependent functional selectivity, or an indication that NAGly modulates neuronal activity via other receptor systems, remains an open question.

GPR119 in CNS

A third relevant G-protein-coupled receptor, GPR119, has been deorphanized. In humans, GPR119 was initially reported to be expressed only outside of CNS, most notably in pancreas, suggesting a peripheral metabolic function (Fredriksson et al., 2003). A possible CNS expression difference between human and rodent species is suggested in a patent application that indicates GPR119 is also expressed at high density in rat and mouse brain (Bonini et al., 2002). Mouse CNS expression is confirmed by high-affinity GPR119 binding and potent efficacy to reduce seizure-related hippocampal activity (Scott et al., 2014). At micromolar concentrations, the endogenous peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα) agonist oleoylethanolamide (OEA) activates GPR119, while anandamide appears to have partial efficacy in yeast cells expressing the receptor (Overton et al., 2006). Notably, 2-AG, CP55940, WIN55212-2, methanandamide, and JWH-133 did not activate GPR119. Supporting CNS activity, and a role in controlling ingestive behaviors, OEA and a synthetic GPR119 agonist with similar efficacy, but four-fold greater potency, PSN632408, were found to reduce food consumption and body weight in Sprague-Dawley rats (Overton et al., 2006). More recent evidence suggests that PSN632408 may lack selectivity for GPR119 in peripheral tissues (Ning et al., 2008). Despite evidence of GPR119 CNS activity, this receptor is being most closely studied in as a target for treating diabetes and other metabolic disorders (Ansarullah et al., 2013; Cornall et al., 2013, 2015).

GPR35 in CNS

A final Gi/o-coupled deorphanized receptor, GPR35, has been reported to transduce effects of 2-arachidonyl lysophosphatidic acid (2A-LPA) and kynurenic acid, both of which are present at relevant concentrations within neuronal tissues. 2A-LPA is a product of metabolism of the principal brain endocannabinoid, 2-arachidonyl glycerol (2-AG, Oka et al., 2010). Kynurenic acid is the product of tryptophan metabolism, and is most well-characterized as an endogenous antagonist of receptors for the principal excitatory neurotransmitter, NMDA (Stone et al., 2013). A very recent structure-activity study has led to identification of several potent GPR35 agonists and three structures critical for efficacy (Abdalhameed et al., 2017). GPR35 is expressed most predominantly in the gastrointestinal tract and in leukocytes (Wang et al., 2006). Low-level expression of GPR35 in brain reduces the likelihood that it significantly modulates neuronal activity within this region of the CNS. Within spinal cord, on the other hand, convincing evidence demonstrates functionally-relevant expression of GPR35, with distinct enrichment within murine dorsal horn ganglia (Cosi et al., 2011). In an acetic acid-induced pain assay, both kynurenic acid, and the phosphodiesterase inhibitor, zaprinast, were found to produce significant analgesia with EC50s of about 100 and 1 mg/kg, respectively. Note zaprinast is an effective agonist of GPR35 with a particularly high potency at rat vs. human forms of the receptor (Taniguchi et al., 2006). Homology between GPR35, and other LPA receptors, may suggest that 2A-LPA is more relevant than kynurenic acid as an endogenous modulator (Zhao and Abood, 2013). Clearly, more needs to be learned and understood about GPR35 signaling.

Opioid receptors in CNS

Evidence implicating interaction between cannabinoid and opioid signaling systems began to accumulate early, and before specific cannabinoid receptors were unequivocally identified. For example, it was well-established by the 1980s that THC effectively reduces symptoms of naloxone-precipitated opioid withdrawal (Hine et al., 1975). Similarly, the analgesic efficacy of THC was known to depend upon μ-opioid receptors (μOP, Cox et al., 2015), as use of an irreversible antagonist (chlornaltrexamine, that alkylates and destroys activity of μOPs) reduces efficacy of both morphine and THC in the hotplate assay (Tulunay et al., 1981). Using the μOP-selective radioligand, [3H]-dihydromorphine, it was found that THC non-competitively reduces the density of binding sites in brain membranes via an unknown mechanism (Vaysse et al., 1987). More recently, it has been demonstrated that augmentation of endocannabinoid signaling using the monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL) inhibitor JZL184 (MAGL is an enzyme responsible for degrading the endocannabinoid 2-AG) has efficacy similar to THC in reducing opioid withdrawal symptoms. This suggests MAGL as a potential target for managing opioid addiction (Ramesh et al., 2011).

More progress has been made since development of CB1/CB2 receptor-deficient mice and availability of selective antagonists. Interestingly, when using CB1 knockout mice with the CB1-selective cannabinoid antagonist/inverse agonist SR, it was found that SR effectively reduces both basal levels of G-protein activation and the ability of the μOP peptide agonist, DAMGO, to stimulate GTPγS binding (Cinar and Szücs, 2009). These results were obtained using mouse cortical membranes (where μOP and CB1 are normally both distinctly expressed), and there was no difference in efficacy across tissue obtained from wild type and CB1 knockout animals, clearly demonstrating a non-CB1-related mechanism for SR's inverse agonist activity (although not excluding the possibility that CB1 constitutive activity drives inverse agonism in other systems). Additional experiments using CB1 and μOP transfected CHO cells revealed that micromolar concentrations of SR are able to displace ligands bound to μOPs, demonstrating an interesting direct SR-μOP interaction.

The nature of this SR-μOP interaction was further explored by demonstrating that both SR and the 2-AG-related endocannabinoid noladin ether are both able to potently antagonize DAMGO-stimulated GTPγS binding in membranes taken from wildtype animals (Zádor et al., 2012). In membranes from CB1 deficient mice, both SR and a combination of SR and noladin ether reduced the efficacy of DAMGO to stimulate GTPγS binding, without altering potency, suggesting μOP-CB1 interaction, and non-competitive antagonism of μOP in the absence of CB1. These studies employing DAMGO, relevant to μOP activity, were extended to employ the δ-opioid receptor (δOP) selective peptide agonist DPDPE. In CHO cells expressing δOP, SR reduced basal GTPγS activation with an EC50 ~ 1 μM. SR also non-competitively antagonized DPDPE stimulation of GTPγS binding to an extent similar to that achieved by the competitive δOP antagonist, naltrindole (Zádor et al., 2014). Completing evaluation of SR interaction with the three primary opioid receptor subtypes, the same group demonstrated SR displaces binding of the κ-opioid receptor (κOP) agonist U-69,593 from membranes prepared from transfected CHO cell membranes. Using these transfected cells in vitro, SR was found to inhibit basal levels of κOP activation in a manner antagonized by the κ-selective antagonist, nor-BNI, suggesting that SR is a κOP inverse agonist. In both CB1 deficient and wildtype mice, systemic pretreatment of animals with a low, 0.1 mg/kg dosage of SR decreased efficacy of the κOP peptide agonist, dynorphin A to activate GTPγS binding in preparations of brain membranes (Zádor et al., 2015). The magnitude of efficacy reductions following SR pretreatment was similar across CB1 knockouts and wildtype animals, and the potency was not altered, suggesting that SR acts to effectively reduce κOP density. Behavioral tests demonstrated an anxiolytic effect of low-dose (0.1 mg/kg subcutaneous) SR treatments, perhaps contrasting with established dysphoric effects of higher doses in other systems, including humans.

Related to morphine dependence, is evidence indicating that chronic morphine treatment of rats results in upregulation of both CB1 protein and mRNA encoding the receptor (Jin et al., 2014). Morphine-induced CB1 expression was also associated with cytokine release, including IL-6, and, most notably, IL-1B, in various brain regions, including cortex, hippocampus, cerebellum, and brain stem. Coincidently, CB1 upregulation and cytokine release implicate both cannabinoid signaling and immune responsiveness in effects associated with opioid dependence. Interestingly, the microRNA let-7d and CB1 receptors reciprocally downregulate each other in transfected SH-SY5Y cell cultures (Chiarlone et al., 2016). Let-7d-expressing SH-SY5Y cells show decreased sensitivity to methanandamide and morphine in stimulating ERK phosphorylation and a high degree of cross-tolerance following chronic treatments with the cannabinoid- and opioid agonists. Perhaps related to this interaction is evidence for efficacy of the opioid antagonist naltrexone (currently indicated for managing alcoholism) in the treatment of Cannabis dependence (Haney et al., 2015).

Serotonin receptors in CNS

5-HT3 ligand-gated cation channels in CNS

As with other systems, evidence for cannabinoid modulation of serotonin signaling was obtained soon after CB1 receptors were identified. This evidence began to accumulate through studies of the rat nodose ganglion which conducts afferent transmission from GI, heart, and lung. Activity in this ganglion is increased by the 5-HT3 subtype of serotonin-gated cation channels. Using the synthetic agonists CP55940 and WIN, and the most well-established endocannabinoid at the time, anandamide, it was discovered that each of these agonists non-competitively antagonizes serotonergic activation of 5-HT3 receptors at nanomolar concentrations (Fan, 1995). The inability to modulate cannabinoid effects on 5-HT3 activity with guanyl nucleotides suggested a non-G-protein dependent mechanism, and possible direct interaction with the ion channel. This finding raised speculation that analgesic and antiemetic efficacy of cannabinoid agonists may, at least in part, be attributable to 5-HT3 antagonism.

Effects in the isolated tissue preparation described above were corroborated by results of experiments using a human 5-HT3A-expressing CHO cell line (Barann et al., 2002). In patch clamp studies it was found that a series of synthetic, endogenous, and phytocannabinoid agonists potently inhibited serotonin activation of 5-HT3 cation channels. Notably, the phytocannabinoid THC was the most potent compound evaluated with EC50 ~ 40 nM. Cannabinoid antagonism was not inhibited by the CB1-selective antagonist SR. Specific binding of a 5-HT3-selective radioligand wasn't displaced by the cannabinoids employed, suggesting interaction with an allosteric site that doesn't influence serotonin affinity.

5-HT1A GPCRs in CNS

The 5-HT1A subtype of serotonin receptors are notably associated with presynaptic distribution, where, similar to CB1 receptors, their activation reduces probability of neurotransmitter release. Although this type of presynaptic autoreceptor mechanism is well-characterized for 5-HT1A, the distribution of these receptors is wide, and it includes both excitatory and inhibitory terminals, making prediction of effects produced by modulators difficult.

Multiple lines of evidence suggest that the enigmatic non-psychotropic phytocannabinoid CBD exerts at least some of its actions through agonism of 5-HT1A autoreceptors (McPartland et al., 2015). First, CBD displaces specific binding of the 5-HT1A-selective radioligand [3H]8-OH-DPAT, activates GTPγS binding and inhibits adenylyl cyclase activity in heterologously expressing CHO cell cultures (Russo et al., 2005). Second, 5-HT1A receptor expression is upregulated under conditions of neuropathic pain in a manner that is reduced by cannabinoid agonism (Palazzo et al., 2006). Finally, microinfusion of CBD into the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) dose-dependently reduces anxiety as measured by both elevated plus maze and Vogel conflict tests (Gomes et al., 2011).

These anxiolytic CBD responses are reversed by pretreatment with the 5-HT1A-selective agent WAY-100635 (WAY) that has been reported to be a neutral antagonist, although agonism at D4 dopamine receptors has also been reported (Chemel et al., 2006). Recently, WAY-reversible anxiolytic effects of CBD as measured in the elevated plus maze have been confirmed by others (Fogaça et al., 2014). CBD mitigation of acute restraint stress was also found, although, perhaps importantly, this effect was more resistant to WAY antagonism, possibly suggesting involvement of another target in stress vs. anxiety responses. Interestingly, anxiolytic effects of both CB1 and 5-HT1A agonists have been reported in a non-mammalian teleost fish, suggesting a conserved relationship between cannabinoid and serotonergic signaling in responding to stress (Connors et al., 2014).

Extending studies of CBD anxiolysis that are reversed by the 5-HT1A antagonist WAY, mitigation of nausea as measure in the rat gaping model (Rock et al., 2014), reduction of both neuropathic pain (Ward et al., 2014) and panicolytic effects (Twardowschy et al., 2013) have all been reported. In the context of drug abuse, CBD antagonizes effects of morphine to reduce threshold intracranial self-stimulation responding—a measure of drug reward. CBD antagonism of morphine reward was reversed by microinjection of WAY into dorsal raphe, further implicating 5-HT1A involvement (Katsidoni et al., 2013). More recently, CBD has been reported to have rapid-onset antidepressive efficacy that is dependent upon 5-HT1A activation (Linge et al., 2016).

Other serotonin receptors in CNS

Physiological interactions, where activity of one signaling system influences activity of another, have been documented to occur between cannabinoid and serotonergic signaling in models of chronic pain (Campos et al., 2013); epilepsy (Devinsky et al., 2014); stress-induced analgesia (Yesilyurt et al., 2015) and; tic disorders (Ceci et al., 2015). These studies reinforce the possibility of using inhibitors of endocannabinoid uptake and metabolism therapeutically.

Adenosine receptors in CNS

Adenosine signaling in CNS is largely terminated by reuptake, making inhibitors of the transporter indirect-acting adenosinergic agonists. Such agents have shown anti-inflammatory efficacy via inhibiting release of immune mediators like TNFα (Noji et al., 2002). Interestingly, the phytocannabinoid CBD, discussed above, in the context of 5-HT1A agonism (5-HT1A GPCRs in CNS), appears to inhibit immunosuppressive effects via direct interaction with, and antagonism of, an adenosine transporter (Carrier et al., 2006). CBD anti-inflammatory effects were absent in adenosine A2A knockout mice, and reversed by a selective antagonist, implicating indirect agonism of A2A receptors as the mechanism of CBD-mediated immunosuppression.

Antagonists of adenosine receptors are established psychomotor stimulants. In the context of movement disorders, A2A receptors are expressed at high levels within the inhibitory indirect dopaminergic pathway of vertebrate striatum. Interneurons in this region also robustly express presynaptic CB1 receptors that inhibit activity of the inhibitory pathway, resulting in an overall activation of movement-related striatal signaling. Experiments employing CB1 deficient mice found these animals to be resistant to the psychomotor stimulant effect of adenosine receptor antagonists (Lerner et al., 2010). Further investigation found that the A2A-selective antagonist, SCH442416, doubled the concentration of the endocannabinoid, 2-AG, within striatum, but not cortex. Increased 2-AG release was associated with decreased indirect pathway activity as measured electrophysiologically. These results demonstrate that the psychomotor efficacy of A2A antagonists involve, to some extent, indirect endocannabinoid agonism. More recently it has been discovered that CB1-mediated disruption of memory consolidation is mitigated by A2A antagonism, further elaborating the co-dependence of cannabinoid and adenosinergic signaling (Mouro et al., 2017).

Excitatory amino acid receptors in CNS

NMDA receptors in CNS

Given general sedative effects of cannabinoid agonists, it isn't surprising that these agents act, at many sites, to reduce release of the principal excitatory neurotransmitter, NMDA. This was found to clearly be the case in rat brain slice preparations for synthetic agonists (Shen et al., 1996) and both the endocannabinoid anandamide and phytocannabinoid THC. Inhibitory effects of THC and anandamide were reversed in the presence of both the CB1-selective antagonist SR and Gi inhibitor pertussis toxin implicating cannabinoid-receptor involvement (Hampson et al., 1998). But, in the presence of SR, anandamide potentiation of NMDA-induced currents were noted. This stimulatory effect of anandamide was also observed in Xenopus oocytes expressing NMDA receptor (NMDAR) subunits, suggesting a direct agonist interaction with these cation channel proteins.

With similarities to results of experiments done in slice preparations, additional evidence for anandamide interaction with NMDA receptors derives from studies of the complex cannabinoid modulation of blood pressure control in rats (Malinowska et al., 2010). In this system, it was discovered that anandamide produces a pressor effect in the presence of the CB1-selective antagonist, SR. This increase in pressure was partially reduced by the NMDA receptor-selective antagonist MK-801, suggesting a possible direct interaction with relevance to central control of blood pressure.

More recently, the interaction of anandamide and NMDAR activation has been more elaborately studied through a series of electrophysiology studies in rat hippocampal sections and dissected cells (Yang et al., 2014). These experiments demonstrated that CA1 pyramidal cell NMDAR activation by anandamide was reversed in the presence of the TRPV1 antagonist capsazepine, raising the possibility of vanilloid receptor involvement in the anandamide effects discussed above. 2-AG was also studied in these experiments and found to produce a similar potentiation of NMDAR activation, although distinct in that it was not blocked by TRPV1 antagonism. Interestingly, the efficacy of 2-AG was increased when delivered intracellularly, suggesting interaction with NMDAR or other protein domains inside the neuron.

It has long been suspected that Cannabis abuse increases risk of psychoses (Colizzi et al., 2016). In a mouse model of NMDAR antagonist-precipitated psychosis (MK-801), the CB1-selective antagonist AM 251 reduced behavioral symptoms, including hyperactivity (Kruk-Slomka et al., 2016). Interestingly, CB1-antagonism also improved psychosis-related memory impairments in this model, suggesting a possible role for endocannabinoid signaling in the memory deficits associated with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

AMPA receptors in CNS

An early Xenopus oocyte expression study examining sensitivity of various AMPA receptor subunit compositions demonstrated that high concentrations of anandamide (EC50 > 100 μM) effectively inhibit/s AMPA agonist-initiated currents (Akinshola et al., 1999). Anandamide inhibition was not reversed by SR, as expected in the CB1-deficient expression system, and similar efficacy was not observed for the synthetic agonist WIN. Enhancement of anandamide's effect was produced by addition of forskolin, a direct adenylyl cyclase activator, and partially reversed by cyclase inhibitors, implicating this enzyme in mediating the effect.

An interesting physiological interaction between endocannabinoid and AMPA receptor signaling has been reported in chicken embryo spinal cord (Gonzalez-Islas et al., 2012). In this system, a basal endocannabinoid tone inhibits activity of motor neurons which decreases spontaneous activity. Reversal of endocannabinoid tone via application of the CB1-selective antagonist, AM 251 resulted in an increase of spontaneous activity that, over 2 days, resulted in AMPA receptor desensitization, implicating endocannabinoid signaling in regulation of motor activity during development.

Metabotropic glutamate receptors in CNS

Physiological interaction of metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR) and endocannabinoid signaling has been reported in striatal and hippocampal slice preparations (Jung et al., 2005). In this system, activation of the mGluR5 receptor subtype resulted in release of the endocannabinoid 2-AG but not anandamide. This finding implicates 2-AG as the endocannabinoid involved in mediating AMPA receptor-induced plasticity important to processes of learning and memory.

Inhibitory amino acid receptors in CNS

GABA and glycine are amino acid transmitters that activate inhibitory chloride channels, and in the case of GABAB, Gi/o-coupled metabotropic receptors that activate inhibitory inwardly rectifying K+ flow. Overall sedative effects of cannabinoid agonists made positive regulation of these inhibitory amino acid transmitter systems seem likely, although clear evidence of interaction with GABAergic signaling systems has emerged only recently.

Gaba receptors in CNS

In the case of cannabinoid receptor-independent effects on GABAergic signaling, in hippocampal slice preparations it has been found that WIN55212-2 and anandamide (but not 2-AG) potentiate GABA release within rat dentate gyrus. This release promoted measurable inhibitory post-synaptic currents (IPSCs) measured by electrophysiology. The fact these WIN55212-2 and anandamide-promoted currents were resistant to both CB1- and CB2-selective antagonists in tissues taken from CB1 deficient mice, is evidence that they are the result of interaction with a yet uncharacterized target (Hofmann et al., 2011). Interestingly, the agonist specificity (WIN55212-2 and anandamide) of this IPSC effect is similar to that discovered earlier in GTPγS binding assays employing mouse tissue (Breivogel et al., 2001) suggesting that the same target is responsible.

In the context of behavior, 2-AG has been shown to reduce locomotor activity in CB1/CB2 double knockout mice (Sigel et al., 2011). Unfortunately only endocannabinoids were investigated in this study leaving open the question of WIN55212-2 activity that is implicated by earlier studies mentioned above. Hypermotility was observed in mice deficient for the GABAA B2 subunit. When heterologously expressed in Xenopus oocytes, it was found that electrophysiological effects of 2-AG were only observed in systems producing B2 protein, suggesting this subunit is required for 2-AG interaction with GABAA. B2/2-AG interaction has been further supported by modeling and studies of the effect of amino acid substitutions (Baur et al., 2013). This work has recently been extended to a slice preparation model that demonstrates 2-AG influences GABAA signaling under physiologically-relevant conditions (Golovko et al., 2014). This physiological modulation involves both synaptic and extrasynaptic populations of GABAA receptors enhancing the former and inhibiting the latter in a manner to potentiate overall GABAergic inhibition (Brickley and Mody, 2012).

Endocannabinoid regulation of spinal nociceptive vs. non-nociceptive transmission has been established in vertebrate species (Pernía-Andrade et al., 2009). This work has been extended to demonstrate that the endocannabinoid 2-AG produces similar effects in a non-cannabinoid receptor-expressing invertebrate species of leech (Higgins et al., 2013). The target of 2-AG in this animal appears to be a TRPV channel, as a selective antagonist blocked the effect. Interestingly, the 2-AG effect to potentiate non-nociceptive vs. nociceptive transmission was antagonized by the GABAA-selective agent, bicuculline, suggesting a potential TRPV-GABAergic relationship in this physiological system.

Glycine receptors in CNS

Evidence for direct interaction of the endocannabinoids anandamide and 2-AG and glycine receptors were first reported from electrophysiological studies employing primary neuronal cell cultures and hippocampal slice preparations (Lozovaya et al., 2005). These experiments demonstrated that anandamide, 2-AG and the synthetic agonist WIN55212-2 inhibit glycine receptor conductance post-synaptically, and accelerate desensitization. This effect contrasts with the retrograde, presynaptic endocannabinoid mechanism that has been better characterized to date. Glycine receptor inhibition was observed in the presence of CB1, CB2, and vanilloid receptor antagonists, suggesting a direct agonist mechanism.

Complicating the picture, in a different Xenopus oocyte expression system, anandamide agonism of glycine receptors was discovered (Hejazi et al., 2006). These studies extended the effect to include the phytocannabinoid, THC. In an additional heterologous expression system, using HEK293 cell cultures expressing various glycine receptor subunits, an even more complex picture emerged (Yang et al., 2008). In these studies, anandamide and HU210 potently activated α1 subunit-containing glycine receptors. In contrast, the synthetic agonists HU210, HU308, and WIN55212-2 each potently (EC50 38—3030 nM) inhibited the α2 subunit-mediated currents, while the endocannabinoid NAGly (discussed above as a GPR18 agonist) activated it at high concentration. Efficacy and potency of glycine receptor inhibition varied with differential subunit expression. These types of apparent conflicts in pharmacological literature are common and, as we see with glycine receptors, are often attributable to different physiological/expression systems employed (Urban et al., 2007).

Cholinergic receptors in CNS

Anecdotes have long suggested interaction between cannabinoid and nicotinic cholinergic signaling systems. This relationship is supported by behavioral (Pryor et al., 1978) and more recently biochemical evidence that demonstrates nicotine modulates multiple effects of the phytocannabinoid, THC (Valjent et al., 2002).

A direct mechanism underlying cannabinoid interaction with nicotinic receptors has been revealed through a series of Xenopus oocyte expression studies employing the endocannabinoid anandamide. The first of these found that anandamide potently inhibits nicotinic receptors comprised of α7 subunits (IC50 ~ 30 nM, Oz et al., 2003). This inhibition was not altered by CB1 or CB2 antagonists or cAMP modulating agents suggesting a direct nicotinic receptor interaction. Anandamide inhibition of α7-mediated currents didn't alter nicotine potency, only efficacy, indicating a non-competitive antagonist mechanism. The second study expanded the array of cannabinoid agonists employed in the system finding that only the endocannabinoids anandamide and 2-AG produce potent inhibition (Oz et al., 2004). Notably, THC, WIN, CP55940 did not. The final papers in this series found that the potency of inhibitory effects of both anandamide and ethanol are increased by their co-administration (Oz et al., 2005) and that anandamide potently and non-competitively also antagonizes receptors comprised of α4β2 subunits (EC50 ~ 50 nM, Spivak et al., 2007). Also, the phytocannabinoid CBD was found to inhibit nicotinic currents, albeit less potently (EC50 ~ 11 μM, Mahgoub et al., 2013).

More recently, these studies have been extended out of the oocyte system and into in vivo models. In the first of these, the non-hydrolysable analog of anandamide, methanandamide, was found to effectively antagonize nicotinic receptors present in cardiac post-ganglionic sympathetic neurons (Baranowska et al., 2008). In a second anesthetized rat model, nicotine infusion increased activity of dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area, a region important to reward-related release of dopamine in nucleus accumbens. Nicotine stimulation of this activity was found to be reversed by URB597, an indirect cannabinoid agonist that inhibits anandamide metabolism (Melis et al., 2008). This effect did not extend to the hydrolysis-resistant methanandamide, suggesting that a product of an alternate anandamide metabolic pathway is responsible. Interestingly, both oleoylethanolamine (OEA) and palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) were found to have efficacies similar to anandamide. As OEA and PEA are known agonists of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α (PPARα) activation of this receptor was studied as the potential mechanism for nicotinic receptor inhibition. Results revealed that PPARα activation promotes kinase activity that increases nicotinic receptor phosphorylation and inactivation. Whether the efficacy of anandamide, perhaps through increasing availability of ethanolamine precursors, depends upon a similar PPARα-related mechanism remains an open question.

Nuclear receptors in cancer

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR) in cancer

PPARs are a superfamily of nuclear receptors that play an important role in the regulation of lipid metabolism, glucose homeostasis, cell differentiation and tumorigenesis (Vamecq and Latruffe, 1999). PPAR transcription factors form heterodimers with retinoid X receptor (RXR) that then bind to peroxisome proliferator responsive elements (PPRE) and regulate transcription of target genes. PPARs are classified into three subtypes: PPARα, PPARδ, and PPAR⋎. In cancer cells, targeting PPAR⋎ with selective agonists inhibits cell proliferation, induces programmed cell death (apoptosis and autophagy) and promotes cell differentiation in multiple in vitro and in vivo studies (Campbell et al., 2008).

PPARγ in cancer

Cannabinoids increase PPAR⋎ transcriptional activity by diverse mechanisms (reviewed in O'Sullivan, 2007). Cannabinoids can bind and activate cell surface cannabinoid receptors which promotes MAPK signal transduction resulting in downstream PPARγ activation. Cannabinoid-induced PPARγ activation can also occur independent of cannabinoid receptors by direct and indirect mechanisms. Cannabinoids (e.g., ajulemic acid) and endocannabinoids (e.g., AEA and 2-AG) can directly bind, and increase the transcriptional activity of, PPARγ. Indirect PPARγ activation occurs as a consequence of the metabolism of endocannabinoids (2-AG, AEA) to PPARγ agonists or by increasing the synthesis of endogenous PPAR agonists (Burstein, 2005; O'Sullivan, 2007).

Several studies have shown that PPAR⋎ mediates the antitumor activity of cannabinoids independent of CB1 and CB2 receptors. In lung cancer cells, PPARγ activation was required for CBD-induced apoptosis (Ramer et al., 2013). This effect of CBD on PPARγ was mediated by production of the prostaglandins (PGs), PGD2 and 15deoxy, Δ12, 14 PGJ2 (15d-PGJ2) which are PPARγ activators. Prevention of PG synthesis with a selective inhibitor of COX-2 activity (NS-398) or siRNA directed toward COX-2 reduced CBD-induced PPARγ nuclear translocation and cell death. However, the use of CB1 (AM-251), CB2 (AM-630), or TPRV1 (capsazepine) antagonists did not alter CBD-mediated apoptotic cell death. Furthermore, in human cervical carcinoma cells treated with the non-hydrolysable AEA derivative, met-AEA, apoptosis was reliant upon the production of PGD2 and PGJ2 as well as the activation of PPARγ (Eichele et al., 2009). These findings indicate that cannabinoid-induced prostaglandin synthesis and the engagement of these prostaglandins with PPARγ represents an important pathway by which cannabinoids regulate cellular fate independent of the cannabinoid receptors.

Ion channels in CNS and cancer

Direct cannabinoid modulation of the activity of ionotropic receptors have been discussed according to ligand type in the section above. In terms of interaction with non-ligand gated ion channels, cannabinoid receptor-stimulated G-proteins have long been known to inhibit voltage-gated calcium channels and to activate inward-rectifying potassium channels, consistent with inhibition of transmitter release (Shen et al., 1996). In addition to ligand-gated channel effects, evidence for direct cannabinoid interaction with other non-ligand-gated ion channels has emerged and is discussed below.

Voltage-gated sodium channels in CNS

In the case of the synthetic cannabinoid, ajulemic acid that is structurally-related to THC, patch clamp studies of HEK293 and ND7/23 cells expressing various types of voltage-gated sodium channels demonstrated inhibition with potencies ranging from 1 to 10 μM (Foadi et al., 2014). These results suggest that the efficacy of ajulemic acid to reduce neuropathic pain may involve sodium channel inhibition.

Transient receptor potential (TRP) cation channels in CNS

TRP channels are a superfamily of cation channels located on the cell plasma membrane that control inward movement of monovalent or divalent cations notably including Ca++. These channels are largely sensory-related, and they are particularly important to perception of temperature and mechanical stimulation (Voets et al., 2005). TRP channels have already been mentioned above (in the context of anandamide interaction with NMDA receptors) (section NMDA Receptors in CNS). In addition to a role in mediating peripheral afferent signaling, TRP channels are physiologically relevant to the extraneuronal function of vascular smooth muscle (Fernandes et al., 2012) and are also expressed within CNS (Vennekens et al., 2012). Several members of this family may represent “ionotropic cannabinoid receptors” moving cannabinoid signaling into line with most other CNS signaling systems that include both metabotropic and ion channel targets (Akopian et al., 2009).

Several members of this family, including TRP ankyrin type 1 (TRPA1), the vanilloid receptors types 1 and 2 (TRPV1 and TRPV2), and TRP melastatin type 8 (TRPM8), have been identified through a remarkably ambitious and thorough screening study as targets of an array of compounds isolated from Cannabis (De Petrocellis et al., 2011). These phytocannabinoids include cannabichromene (CBC), CBD, cannabidiol acid (CBDA), cannabidivarin (CBDV), cannabidivarin acid (CBDVA), cannabigerol (CBG), cannabigerol acid (CBGA), cannabigivarin (CBGV), cannabinol (CBN), THC, THC acid (THCA), and tetrahydrocannabivarin acid (THCVA). Each of these compounds are effective agonists for TRP1A with EC50s ranging from 90 nM to 8.4 μM and a rank order of potency of CBC > CBD > CBN > CBDV > CBG > THCV > CBGV > THCA > CBDA > CBGA > THCVA. At TRPV1; CBD, CBG, CBN, CBDV, CBGV, and THCV have agonist activity with EC50 < 10 μM (the most potent compound being CBD with EC50 = 1 μM). At TRPV2, several of the compounds had agonist activity with a rank order of potency = THC > CBD > CBGV > CBG > THCV > CBDV > CBN (EC50 ranging from 650 nM to 19 μM). Finally, at TRPM8, each of the compounds were found to effectively antagonize icilin-stimulated Ca++ conductance with a rank order of potency = CBD > CBG > THCA > CBN > THCV > CBDV > CBGA > THCVA > CBGV > CBDA and IC50s ranging from 60 nM to 4.8 μM.

Interestingly, the synthetic cannabinoid compounds AM251 and AM630, that are CB1- and CB2-selective antagonists/inverse agonists, respectively, have been found to activate Ca++ channels in primary cultures of trigeminal nerve neurons (Patil et al., 2011). When evaluated in CHO cell culture systems heterologously expressing TRP1A and TRPV1 channels, it was found that both CB receptor antagonists have agonist activity at TRP1A but not TRPV1. These findings suggest that in vivo AM251 and AM630 may activate sensory neurons via TRP1A agonism.

Focus on TRPV1 in CNS

Also known as capsaicin receptors or vanilloid receptors, these promiscuous cation channels are both temperature- and pH-sensitive. They are also capable of ligand activation, notably by capsaicin (the active constituent of spicy peppers). Shortly after its isolation and identification as the first endogenous cannabinoid present in brain, anandamide was found to interact with a non-cannabinoid receptor target: TRPV1 (Zygmunt et al., 1999). The relationship between anandamide and other endocannabinoid signaling and TRPV1 channel activity has been the subject of excellent recent reviews (Dainese et al., 2010; Marzo and Petrocellis, 2010; Di Marzo and De Petrocellis, 2012), and so, only two notable recent additions, confirming the physiological relevance of TRPV1 agonism by anandamide to neuronal activity, will be presented here.

The first is an interesting recent study of the analgesic effects of the fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) inhibitor: URB597. This compound reduces metabolism of the endocannabinoid, anandamide, thereby enhancing effects of endogenous release. Systemic administration of URB597 effectively reduces measures of neuropathic pain in the rat chronic constriction injury model (Starowicz et al., 2013). Analgesic efficacy of URB597 was maintained in the presence of the CB1-selective antagonist, AM251. However, pretreatment of animals with the potent TRPV1 antagonist, iodoresiniferatoxin, reversed effects of URB597. These important results reinforce the role of endocannabinoid signaling in pain sensation, and they demonstrate that agonism of the TRPV1 subtype of vanilloid receptors is important to this type of analgesic efficacy of anandamide.

A second recent study employed mouse hippocampal cultures of CA1 presynaptic CB1-expressing GABAergic neurons and post-synaptic pyramidal neurons. Activities of both neuron types were studied simultaneously via an ambitious paired patch clamping technique (Lee et al., 2015). As expected, post-synaptic depolarizations were associated with increased 2-AG release and diffusion, ultimately resulting in presynaptic CB1 activation. In the case of perisomatic input to pyramidal cells, a basal tone of 2-AG stimulation of presynaptic CB1 receptors was found to maintain a “set point” of GABA release. This set point was revealed by increased inhibition following application of JZL184, an inhibitor of MAGL. As MAGL is the principal enzyme responsible for degrading 2-AG, inhibitors like JZL184 act as indirect agonists. Interestingly, addition of PF3845, an inhibitor of the enzyme FAAH responsible for degrading anandamide, effectively reduced 2-AG tone, suggesting an antagonistic relationship between the two endocannabinoids in regulating GABAergic signaling in hippocampus. The indirect anandamide agonist effect of PF3845 was reversed in the presence of AMG9810, a selective TRPV1 inhibitor, demonstrating that anandamide effectively modulates basal 2-AG tone via activation of this post-synaptic cation channel, presumably via reduced activity of the enzyme responsible for 2-AG synthesis, DAGLα.

TRP cation channels in cancer

A growing body of evidence implicates members of the TRP family, including TRPV1, TRPV2, and TRPM8, in calcium-mediated signal transduction that regulates proliferation, migration, and metastasis of cancer cells (reviewed by Déliot and Constantin, 2015; Yee, 2015). As discussed previously, numerous cannabinoids bind to, and modify, the activity of TRP channels. We review TRP-mediated activity of several cannabinoids in cancer below.

Vanilloid receptor type 1 (TRPV1) in cancer

TRPV1 Ca++ channels are located on the plasma membrane and other subcellular organelles including the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). TRPV1 regulates intracellular Ca++ levels by controlling Ca++ movement across the plasma membrane and its release from the ER and sarcoplasmic reticulum (Gallego-Sandín et al., 2009). Establishing the relationship between TRPV1 expression levels, and characteristics such as the tumor grade (predicted aggressiveness of the tumor) or tumor stage (tumor size and degree of spread), aids in determining its potential role in cancer. It has been reported that TRPV1 expression increased with increasing tumor grade in prostate cancer biopsies (Czifra et al., 2009), but it was inversely correlated with tumor stage in bladder cancer (Lazzeri et al., 2005) suggesting that the relationship between TRPV1 expression and tumor behavior may be tumor-type specific. Other studies provide evidence that TRPV1 activation is necessary for cannabinoid-induced tumor death. The endocannabinoid, AEA, decreased the viability of cervical cancer cells that overexpressed TRPV1, CB1, and CB2. In these cells, the antiproliferative effect of AEA was counteracted by blockade of TRPV1 but not by antagonism of the CB1 or CB2 receptors (Contassot et al., 2004a). Similarly, AEA initiated TRPV1-dependent, CB receptor-independent apoptosis in human glioma cells (Contassot et al., 2004b). Based upon these interesting findings, further investigation should uncover roles of TRPV1 in cancer and identify other cannabinoid agonists that decrease cancer growth by targeting this pathway.

Vanilloid receptor type 2 (TRPV2) in cancer

The specific role of TRPV2 in carcinogenesis appears to differ according to tumor type. In urothelial carcinoma, TRPV2 expression increased with increasing tumor stage and grade (Caprodossi et al., 2008). However, in hepatocellular carcinoma, TRPV2 expression was lower in poorly differentiated (compared to well-differentiated) tumors (Liu et al., 2010). In glioblastoma multiforme, elevated TRPV2 expression correlated with increased patient survival (Alptekin et al., 2015) while increased TRPV2 expression was associated with poor survival in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (Zhou et al., 2014). Although the aforementioned studies demonstrate that the role of TRPV2 in cancer progression is unclear, research that examined the impact of cannabinoids on this cation channel demonstrated that TRPV2 activation decreased tumor cell survival and sensitized tumor cells to clinically available chemotherapeutic agents. The phytocannabinoid, CBD, increases inward movement of Ca++, but it has low affinity interactions with CB1 and CB2 receptors (De Petrocellis et al., 2011; McPartland et al., 2015). In glioblastoma, CBD increased the plasma membrane expression of TRPV2 and prevented cell resistance to carmustine (BCNU), doxorubicin, and temozolmide (Nabissi et al., 2013). This sensitization to cytotoxic chemotherapeutics was prevented by siRNA-mediated disruption of TRPV2 expression. Consistent with this finding, the antiproliferative effects of CBD in stem-like glioma cells were reversed in the presence of the Ca++ channel blocker, ruthenium red (RR), and the selective TRPV2 blocker, tranilast (Nabissi et al., 2015). As anticipated, antagonists of CB1 (AM251) and CB2 (AM630) were not able to rescue cells from cell death (Nabissi et al., 2015). Moreover, the sensitivity of multiple myeloma cells to bortezomib was heightened by cell exposure to CBD in a TRPV2-dependent manner (Hashimoto et al., 1986). These findings suggest calcium mobilization regulated by TRPV2 is essential for CBD-mediated cell death. Further investigation of the activity of TRPV2 in cancer is needed to determine the feasibility of utilizing cannabinoids to target this cation channel as a therapeutic strategy.

Transporters in CNS

Transporters function to actively facilitate movement of molecules across membranes against concentration and osmotic gradients. Drugs that target transporters exert effects through altering distribution of other molecules that, in turn, alter membrane potential of excitable membranes and/or terminate action of transmitters that are regulated by uptake. With respect to cannabinoid signaling, evidence suggests that transport may contribute to anandamide signal termination, in addition to metabolism by FAAH (Nicolussi and Gertsch, 2015). The anandamide transporter remains a target for development of selective inhibitors (Nicolussi et al., 2014).

Adding to the promiscuous interaction of anandamide with non-CB1/CB2 targets is evidence for inhibition of a Na+/Ca++ exchange pump (Kury et al., 2014). This inhibition was of both influx and efflux, and was not altered by CB1- and CB2-selective antagonists, pertussis toxin or guanyl nucleotide analogs, consistent with a direct interaction with the transporter. Although this transporter is most relevant to cardiac function, similar transporters are important to CNS activity, and these results suggest potential anandamide neuronal efficacy related to ion transport.

Part of the cannabinoid effects on glycinergic signaling discussed above (section Glycine Receptors in CNS) may in part be attributable to interaction with glycine transporters. In the case of glycine transporter GLYT1a, arachidonic acid and anandamide have interesting opposing modulatory actions (Pearlman et al., 2003). Interestingly, evidence that upregulation of GLT-1, the transporter for the excitatory transmitter glutamate, in preventing cannabinoid dependence, is also emerging (Gunduz et al., 2011).

As discussed above in the context of adenosine (section Adenosine Receptors in CNS), evidence demonstrates that the phytocannabinoid CBD antagonizes an adenosine transporter, reducing inflammatory responses (Carrier et al., 2006). This activity was absent in adenosine A2A knockout mice, and reversed by a selective antagonist, implicating indirect A2A agonism, via inhibition of transporter-mediated signal termination, as the mechanism of CBD-mediated immunosuppression.

While not demonstrating a direct interaction, studies of effects of the synthetic CB1/CB2 agonist, WIN, have revealed that dosages effective in reducing locomotor activity (0.1–1 mg/kg) also decrease expression of dopamine transporters (Fanarioti et al., 2015). Transporter densities were measured by in situ [3H]-WIN35428 binding. Decreased levels were observed in several brain regions relevant to drug abuse including: nucleus accumbens core and shell; substantia nigra and; ventral tegmentum.

Enzymes in CNS and cancer

Endocannabinoid synthesis and metabolism in CNS