Abstract

Aristolochic acids (AAs) are a group of toxins commonly present in the plants of genus Aristolochia and Asarum, which are spread all over the world. Since the 1990s, AA-induced nephropathy (AAN) and upper tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC) have been reported in many countries. The underlying mechanisms of AAN and AA-induced UTUC have been extensively investigated. AA-derived DNA adducts are recognized as specific biomarkers of AA exposure, and a mutational signature predominantly characterized by A→T transversions has been detected in AA-induced UTUC tumor tissues. In addition, various enzymes and organic anion transporters are involved in AA-induced adverse reactions. The progressive lesions and mutational events initiated by AAs are irreversible, and no effective therapeutic regimen for AAN and AA-induced UTUC has been established until now. Because of several warnings on the toxic effects of AAs by the US Food and Drug Administration and the regulatory authorities of some other countries, the sale and use of AA-containing products have been banned or restricted in most countries. However, AA-related adverse events still occur, especially in the Asian and Balkan regions. Therefore, the use of AA-containing herbal remedies and the consumption of food contaminated by AAs still carry high risk. More strict precautions should be taken to protect the public from AA exposure.

Introduction

Aristolochic acids (AAs) are identified as a group of toxins that can cause end-stage renal failure associated with urothelial carcinoma. In 1992, a high prevalence of kidney disease accompanied by urothelial carcinoma in female patients ingesting slimming pills raised worldwide attention to the high nephrotoxic and carcinogenic potential of AAs. Subsequently, Balkan endemic nephropathy (BEN) has also been found to be associated with the exposure to AAs. Since then, different studies have addressed the characterization and quantitation of AA analogs in plants and products, and the underlying mechanisms involved in the adverse reactions of AAs have been broadly described (Zhou et al., 2019).

Aristolochic Acids

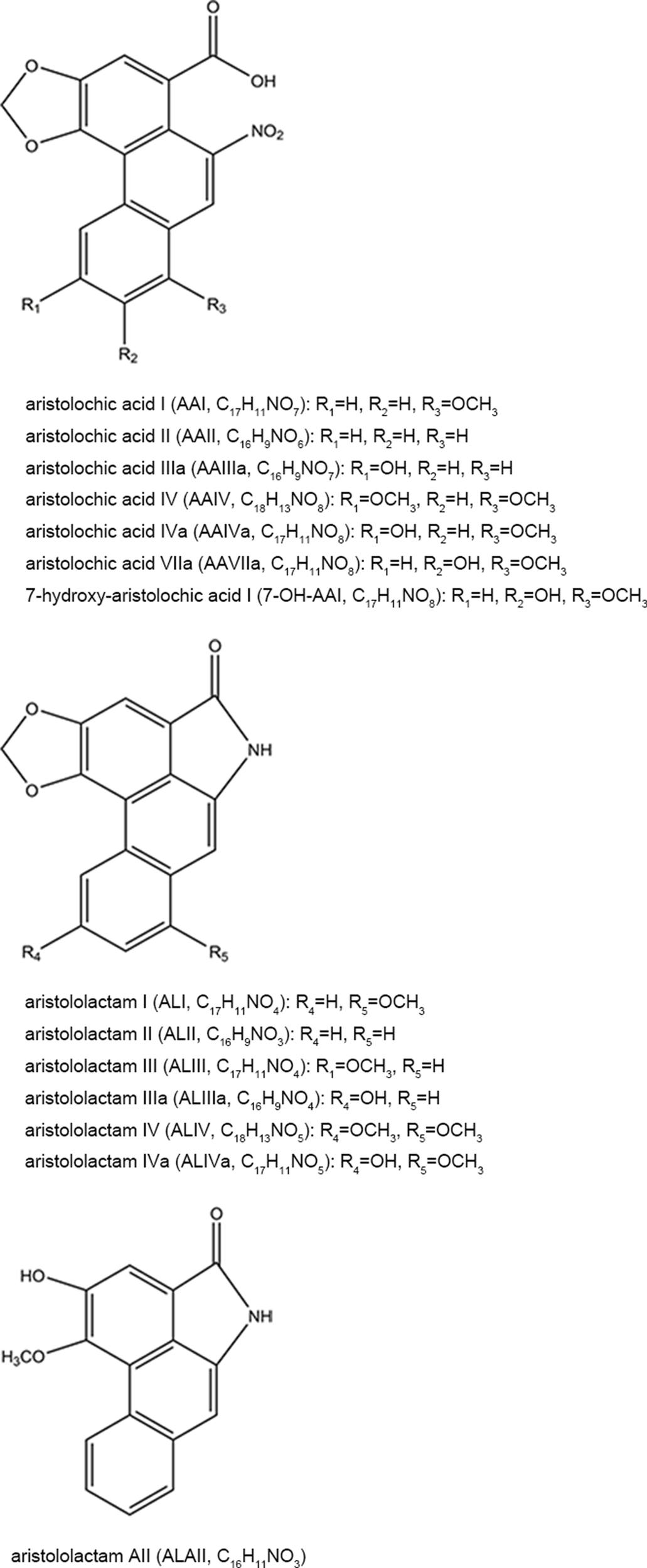

AAs are abundant in the plants of genus Aristolochia and Asarum, which are spread all over the world (Hashimoto et al., 1999; Wooltorton, 2004; Liang et al., 2017). So far, more than 178 AA analogs have been isolated from natural sources (Michl et al., 2014), in which at least seven species of Aristolochia, including Aristolochia indica L. (Asia), A. serpentaria L. (North America), A. debilis Sieb and Zucch. (China), A. acuminata Lam (India), A. trilobata L. (Central/South America, Caribbean), A. clematitis L. (Europe), and A. bracteolata Lam. (Africa) (Heinrich et al., 2009), as well as four species of Asarum, including Asarum heteropoides f. mandshuricum (Maxim). Kitag and A. sieboldii Miq (China), A. europaeum L. (Europe), and A. canadense L (Canada and USA) (Michl et al., 2017) are used medicinally. Herbs or products containing AAs are commonly used for treating cold, headache, aphthous stomatitis, inflammatory diseases, snake bites, and sexual problems (Li et al., 2010; Kuo et al., 2012; Michl et al., 2013; Bhattacharjee et al., 2017; Liang et al., 2017). Since nephrotoxicity and carcinogenicity of AAs have been recognized, the US Food and Drug Administration and regulatory authorities of some other countries have issued alerts against the use and import of products containing parts of Aristolochia. The sale and use of AA-containing products are banned or restricted in most countries. However, in the US and Europe, herbal supplements containing AAs could be easily purchased through the Internet (Gold and Slone, 2003; Schaneberg and Khan, 2004; Michl et al., 2013). In addition, in China and some Asian countries, herbal remedies and products containing herb preparations from Aristolochia and Asarum are still used, and millions of people may be at risk of developing AA-related disease (Hu et al., 2004; Grollman, 2013; Rosenquist and Grollman, 2016). Studies have been performed to assess the AA content in different plants and products. Some typical AA analogs (Figure 1) obtained from plants and Chinese patent medicines are listed in Tables 1 and 2.

Figure 1

Chemical structures of some typical AA analogs.

Table 1

| Botanical name | Plant part | AAI | AAII | AA IIIa |

AAIV | AA IVa |

AA VIIa |

7-OH-AAI | ALI | ALII | ALIII | ALIIIa | ALIV | ALIVa | AL AII |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aristolochia albida (Michl et al., 2016) | Root | 1.346 | 1.413 | 0.402 | NR | 0.055 | NR | NR | 0.007 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia argentina (Michl et al., 2016) | Stem | 0.085 | 0.156 | − | NR | 0.003 | NR | NR | − | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia austroszechuanica (Zhou et al., 2008) | Root or root tuber | 1.050 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia baetica (Michl et al., 2016) | Leaf | 0.086 | 0.073 | 0.002 | NR | 0.001 | NR | NR | − | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia californica (Michl et al., 2016) | Stem | 0.802 | 0.070 | 0.002 | NR | 0.008 | NR | NR | 0.013 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia chamissonis (Michl et al., 2016) | Leaf | 0.682 | − | − | NR | 0.004 | NR | NR | 0.003 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia cinnabarina (Zhou et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2013b; Wang and Chan, 2014; Yu et al., 2016; Li et al., 2017) | Root | 0.887–12.098 | 0.659–5.076 | 0.841 | NR | 0.246 | NR | NR | − | + | NR | + | NR | NR | − |

| Aristolochia clematitis (Michl et al., 2016) | Root | 1.496 | 2.557 | 0.048 | NR | 0.014 | NR | NR | 0.002 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia contorta (Zhai et al., 2006; Yuan et al., 2007a; Yuan et al., 2007b; Yuan et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2011; Xu et al., 2013; Li et al., 2017; Mao et al., 2017; Ding et al., 2018) | Fruit | 0.034–4.695 | 0.010–0.574 | 0.006–2.081 | NR | 0.019–1.370 | 0.019–0.610 | 0.765–0.902 | 0.071–0.446 | 0.012–0.061 | <LOQ | 0.021 | <LOQ | 0.045–1.080 | 0.010–0.048 |

| Aristolochia contorta (Mao et al., 2017) | Seed | 0.840–2.293 | 0.014–0.132 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia contorta (Mohamed et al., 1999; Wei et al., 2005; Zhai et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2006; Kuo et al., 2010) | Root | 0.511–6.421 | 0.029–6.108 | 0.462 | NR | 0.375–0.688 | NR | NR | 0.017–0.020 | 0.015–0.021 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia contorta (Zhai et al., 2006; Yuan et al., 2007a; Yuan et al., 2008) | Herb | 0.127–10.460 | 0.034–6.325 | 0.375–1.085 | NR | 0.258–0.308 | NR | 1.030–1.150 | 0.021 | − | NR | 0.026–0.105 | NR | 0.010 | 0.015 |

| Aristolochia cucurbitifolia (Michl et al., 2016) | Leaf | 1.107 | 0.122 | 0.004 | NR | 0.009 | NR | NR | 0.122 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia cymbifera (Michl et al., 2016) | Stem | 0.016 | 0.127 | 0.005 | NR | 0.004 | NR | NR | − | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia debilis (Hashimoto et al., 1998; Liu et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2013; Li et al., 2017) | Fruit | 0.299–1.532 | 0.064–0.524 | 0.369–1.179 | NR | 0.030–0.240 | 0.318–0.872 | NR | 0.027–0.462 | 0.017–0.046 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia debilis (Michl et al., 2016) | Stem | 0.012–0.035 | − | 0.211 | NR | 0.024–0.111 | NR | NR | 0.004–0.006 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia debilis (Mohamed et al., 1999; Liu et al., 2005; Yuan et al., 2007a; Yuan et al., 2007b; Kuo et al., 2010; Kong et al., 2015; Li et al., 2017; Ding et al., 2018) | Root | 0.078–2.610 | 0.013–0.875 | 0.004–1.400 | 0.120–0.180 | 0.002–1.750 | NR | 0.284–0.615 | 0.007–0.023 | 0.004–0.271 | 0.011–0.016 | <LOD | 0.096 | 0.096 | 0.102–0.285 |

| Aristolochia debilis (Yuan et al., 2007b) | Herb | 0.175 | 0.039 | 0.481 | NR | 0.245 | NR | 1.290 | NR | <LOQ | 0.016 | NR | <LOQ | NR | NR |

| Aritolochia elegans (Jou et al., 2004) | NR | + | + | N | + | + | NR | NR | N | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | + |

| Aristolochia fangchi (Kuo et al., 2010) | Fruit | 0.945 | 0.050 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia fimbriata (Michl et al., 2016) | Stem | 0.180 | − | − | NR | 0.006 | NR | NR | 0.016 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia fontanesii (Michl et al., 2016) | Leaf | 0.855 | 0.102 | 0.106 | NR | 0.092 | NR | NR | 0.002 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aritolochia foveolata (Jou et al., 2004) | NR | + | + | + | + | + | NR | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | N |

| Aristolochia gibertii (Michl et al., 2016) | Leaf | 0.050 | 1.875 | 0.003 | NR | − | NR | NR | − | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia grandiflora (Michl et al., 2016) | Root | 0.066 | − | 0.148 | NR | 0.049 | NR | NR | 0.028 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia guentheri (Michl et al., 2016) | Stem | 0.002–0.005 | − | − | NR | 0.017 | NR | NR | 0.057 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia heterophylla (Mohamed et al., 1999; Jou et al., 2003; Zhou et al., 2008) | Stems and roots | 1.640–3.260 | + | + | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia heterophylla (Zhou et al., 2008) | Root or root tuber | 1.320–4.450 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia indica (Michl et al., 2016) | Root | 0.818 | 0.239 | 0.117 | NR | 0.029 | NR | NR | 0.018 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia kaempferi (Michl et al., 2016) | Stem | 1.202 | 1.261 | 0.017 | NR | 0.023 | NR | NR | − | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia labiate (Michl et al., 2016) | Leaf | 0.003 | − | − | NR | − | NR | NR | − | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia lagesinan (Michl et al., 2016) | Stem | 0.008 | − | − | NR | − | NR | NR | 0.034 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia littoralis (Michl et al., 2016) | Root | 0.070 | 0.048 | 0.260 | NR | 0.097 | NR | NR | 0.034 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia liukiensis (Michl et al., 2016) | Stem | 0.708 | 0.176 | 0.167 | NR | 0.094 | NR | NR | 0.001 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia macrophylla (Michl et al., 2016) | Stem | 0.014 | 0.000 | 0.009 | NR | 0.008 | NR | NR | − | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia maurorum (Michl et al., 2016) | Leaf | 0.140 | − | 0.002 | NR | 0.006 | NR | NR | 0.003 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia manshuirensis (Hashimoto et al., 1998; Liu et al., 2005; Zhai et al., 2006; Yuan et al., 2007a; Yuan et al., 2007b; Han et al., 2008; Yuan et al., 2008; Kong et al., 2015; Yu et al., 2016; Li et al., 2017) | Stem | 0.310–10.850 | 0.130–2.977 | 0.050–0.652 | 0.350–1.230 | 0.090–0.497 | NR | <LOD | 0.000–0.002 | 0.002–0.006 | 0.000–0.002 | 0.098 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| Aristolochia manshuirensis (Michl et al., 2016) | Leaf | 0.938–1.019 | 1.317–1.673 | 0.002–0.009 | NR | 0.000–0.009 | NR | NR | 0.001–0.004 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia maxima (Michl et al., 2016) | Root | 2.151–2.467 | 0.540–1.438 | 0.022–0.024 | NR | 0.017–0.020 | NR | NR | 0.001–0.004 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia mollissima (Liu et al., 2003; Yuan et al., 2007a; Yuan et al., 2007b; Han et al., 2008; Yuan et al., 2008; Yu et al., 2016) | Herb | 0.106–2.650 | 0.022–0.038 | 0.025–0.158 | NR | 0.041–0.058 | NR | 0.092–0.108 | − | <LOD | <LOD | <LOQ | <LOD | 0.010 | <LOQ |

| Aristolochia mollissima (Zhou et al., 2008) | Aerial part | 0.050 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia mollissima (Mohamed et al., 1999) | Stem and root | 0.465 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia mollissima (Michl et al., 2016) | Leaf | 1.234 | − | 0.001 | NR | 0.006 | NR | NR | 0.001 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia moupinensis (Michl et al., 2016) | Leaf | 1.164 | 0.140 | 0.005 | NR | 0.038 | NR | NR | 0.002 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia moupinensis (Zhou et al., 2008) | Root or root tuber | 0.540–2.780 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia moupinensis (Zhou et al., 2008) | Stem | 0.540–2.150 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia odoratissima (Michl et al., 2016) | Leaf | 0.054 | − | − | NR | 0.003 | NR | NR | − | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia ovalifolia (Michl et al., 2016) | Leaf | 0.419 | − | − | NR | 0.001 | NR | NR | 0.013 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia paucinervis (Michl et al., 2016) | Fruit | 1.597 | 0.931 | 0.034 | NR | 0.055 | NR | NR | 0.054 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia pothieri (Michl et al., 2016) | Leaf | − | − | − | NR | − | NR | NR | 0.114 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia ringens (Michl et al., 2016) | Root | 0.668 | 0.138 | − | NR | 0.026 | NR | NR | 0.002 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia rotunda (Michl et al., 2016) | Root | 1.629 | 1.518 | 0.159 | NR | 0.052 | NR | NR | 0.005 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia sempervirens (Michl et al., 2016) | Leaf | 0.676 | 0.073 | 0.007 | NR | 0.028 | NR | NR | 0.005 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia serpentaria (Michl et al., 2016) | Fruit | 0.992 | 0.077 | 0.002 | NR | 0.013 | NR | NR | 0.017 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aritolochia shimadi (Jou et al., 2004) | NR | + | + | + | + | + | NR | NR | N | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | N |

| Aristolochia tagala (Michl et al., 2016) | Root | 1.347 | 0.090 | 0.243 | NR | 0.121 | NR | NR | 0.006 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia taliscana (Michl et al., 2016) | Stem | 0.010 | − | − | NR | − | NR | NR | − | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia tomentosa (Michl et al., 2016) | Stem | 1.047 | 0.370 | 0.029 | NR | 0.023 | NR | NR | 0.001 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia triangularis (Michl et al., 2016) | Stem | 0.025 | − | 0.001 | NR | 0.032 | NR | NR | 0.005 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia trilobata (Michl et al., 2016) | Stem | 0.435 | 0.157 | 0.109 | NR | 0.017 | NR | NR | 0.012 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia westlandii (Michl et al., 2016) | Stem | 0.001 | − | − | NR | − | NR | NR | − | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Aristolochia zollingeriana (Michl et al., 2016) | Leaf | 0.945–1.189 | 1.745–2.289 | 0.033–0.052 | NR | 0.008–0.010 | NR | NR | 0.004–0.011 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Asarum caudigelellum (Han et al., 2008) | NR | 0.150–0.220 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Asarum heterotropides (Yuan et al., 2007a; Yuan et al., 2007b; Yuan et al., 2008; Zhou et al., 2008) | Herb | 0.040–0.110 | 0.025 | 0.055–0.060 | 0.054–0.058 | 0.047 | NR | 0.041 | 0.048 | 0.005 | <LOD | 0.009–0.031 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOQ |

| Asarum heterotropides (Kuo et al., 2010; Wen et al., 2014) | Root and rhizome | 0.008 | NR | NR | NR | 0.110 | NR | NR | 0.045 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Asarum himalaicum (Zhou et al., 2008) | Herb | 0.440 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Asarum sagittarioides (Han et al., 2008; Zhou et al., 2008) | NR | 0.070–0.180 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Asarum sieboldii (Wen et al., 2014; Kong et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2016) | Root and rhizome | 0.016 | 0.020 | NR | <LOD | 0.072 | NR | NR | 0.004–0.030 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Saruma henryi (Dong et al., 2009; Zhao and Jiang, 2009; Zhang, 2011; Wang et al., 2018a) | Root | 0.184–1.995 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | + | + | NR | NR | + | NR | NR |

| Saruma henryi (Zhang, 2011) | Stem | 0.116 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

Contents of AA analogs in plants.

The unit for quantitative data is mg/g, and the value rounds up to three decimal places.

LOD, limit of detection; LOQ, limit of quantification; N, concentration bellows 2.5 µg/ml; NR, not reported; +, present; −, absent.

Table 2

| Name | AAs | Content | Detection method | Specific herbs in CPM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bu fei e jiao tang (Kuo et al., 2010) | AAI, II | AAI: 119.674 AAII: 6.802 |

LC/MS | Herba Aristolochiae Mollissimae |

| Bi yan ling pian (Zhang, 2017) | AAI | − | HPLC | Radix et Rhizoma Asari |

| Bi yan pian (Guan et al., 2005) | AAI | 3.230 | HPLC | Radix et Rhizoma Asari |

| Chun yang zheng qi wan (Ye et al., 2003) | AAI | 280 | HPLC | Caulis Aristolochiae Manshuriensis |

| Chuan xiong cha tiao ke li (Wei et al., 2005) | AAI | + | LC/MS | Caulis Aristolochiae Manshuriensis |

| Chuan xiong cha tiao san (Kuo et al., 2010) | AAI | − | LC/MS | Caulis Aristolochiae Manshuriensis |

| Chuan xiong cha tiao wan (Ye et al., 2003) | AAI | 140 | HPLC | Caulis Aristolochiae Manshuriensis |

| Dao chi san (Wu et al., 2009) | AAI | 357 | HPLC | Caulis Aristolochiae Manshuriensis |

| Dao chi wan (Wei et al., 2005) | AAI | − | LC/MS | Caulis Akebiae |

| Dang gui si ni tang (Ruan et al., 2012) | AAI | 321.45 | HPLC | Medulla Tetrapanacis |

| Da huang qing wei wan (Shu et al., 2016) | AAI | 0–0.08 | SPE-HPLC | Caulis Akebiae |

| Er shi jiu wei neng xiao san (Zhang et al., 2013a) | AAI | 2.69–3.71 | HPLC | Fructus Aristolochiae |

| Er shi wu wei lv rong hao wan (Chen et al., 2009) | AAI | 99–114 | HPLC | Fructus Aristolochiae |

| Er shi wu wei shan hu wan (Liu et al., 2015) | AAI | − | HPLC, RP-HPLC | Radix Aucklandiae |

| Er shi wu wei shan hu wan (Luo, 2013) | AAI | 52.5 | HPLC | Radix Aucklandiae |

| Er shi wu wei song shi jiao nang (Tan et al., 2005) | AAI | 0.020–0.030 | HPLC | Fructus Aristolochiae |

| Er tong qing fei wan (Wei et al., 2005) | AAI | − | LC/MS | Radix et Rhizoma Asari |

| Fu fang nan xing zhi tong gao (Yin et al., 2009) | AAI | − | UPLC | Radix et Rhizoma Asari |

| Fu fang quan shen pian (Pang and Qu, 2015) | AAI | 0.29–1.02 | HPLC | Herba Aristolochiae Mollissimae |

| Gan lu xiao du wan (Chen and Xie, 2004; Zhu et al., 2006) | AAI, II | AAI: 60–230 AAII: 370–400 |

RP-HPLC | Caulis Aristolochiae Manshuriensis |

| Gan te ling jiao nang (Wei et al., 2007) | AAI | − | HPLC | Radix et Rhizoma Asari |

| Gu ben qu feng ke li (Yu et al., 2011a; Yu et al., 2011b) | AAI | − | HPLC | Radix et Rhizoma Asari |

| Guan xin su he di wan (Li et al., 2006; Yuan and Zhang, 2016) | AAI | 148–993 | HPLC | Radix Aristolochiae |

| Guan xin su he jiao nang (Wei et al., 2005; Li et al., 2006) | AAI, II, IIIa, IVa | AAI: 183–516 AA-II:+ AA-IIIa:+ AA-IVa:+ |

LC/MS | Radix Aristolochiae |

| Guan xin su he wan (Li et al., 2006; Wu, 2006; Jiang et al., 2007; Yuan et al., 2007a; Yuan et al., 2007b; Yuan et al., 2008) | AAI, II | AAI: 48.500–426 AAII: 64.700–65.200 |

RP-HPLC | Radix Aristolochiae |

| Han shi bi ke li (Kang and Li, 2008) | AAI | − | HPLC | Radix et Rhizoma Asari |

| Jian gu shu jin pian (Huang et al., 2009) | AAI | − | HPLC | Radix et Rhizoma Asari |

| Jiu wei qiang huo ke li (Guan et al., 2005) | AAI | 1.920 | RP-HPLC | Radix et Rhizoma Asari |

| Liu jing tou tong tablet (Huang and Zhu, 2015) | AAI | − | SPE-HPLC | Radix et Rhizoma Asari |

| Long dan xie gan wan (Ye et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2005; Wei et al., 2005; Shen et al., 2008) | AAI, II, IIIa, IVa,7-OH-AAI | AAI: 30–253 AAII: 44, AAIIIa: + AA-IVa: + 7-OH-AAI: + |

HPLC; LC/MS | Caulis Aristolochiae Manshuriensis |

| AAI, II, | − | UHPLC-MS/MS | Caulis Akebiae | |

| Long dan xie gan ke li (Wei et al., 2005) | AAI, II, IIIa, IVa,7-OH-AAI | − | LC/MS | Caulis Akebiae |

| Ma huang zhi sou wan (Zhou et al., 2015) | AAI | 0.070–0.210 | SPE-HPLC | Radix et Rhizoma Asari |

| Pai shi ke li (Liu et al., 2005) | AAI, II | AAI: 4 AAII: 4 |

SPE-HPLC HPLC |

Caulis Akebiae |

| Qing nao zhi tong jiao nang (Li et al., 2009) | AAI | − | HPLC | Radix et Rhizoma Asari |

| Qing ning wan (Ye et al., 2003) | AAI | 100 | HPLC | Caulis Aristolochiae Manshuriensis |

| Qing lin ke li (Yuan et al., 2007a; Yuan et al., 2007b; Yuan et al., 2008) | AAI, II, IVa;AL-IV,AL-IVa | AAI: 114–184 AAII: 56.200–62.400 AAIVa: 40.800–58.200 ALIV: 52.500 ALIVa: 32.500–160 |

HPLC LC/MS |

Caulis Akebiae |

| Qi wei hong hua shu sheng wan (Wei et al., 2011) | AAI | 241–385 | HPLC | Fructus Aristolochiae |

| Qing xue nei xiao wan (Gan et al., 2013) | AAI | + | HPLC LC/MS |

Caulis Akebiae |

| Ru mo zhen tong jiao nang (Xue, 2015) | AAI | − | HPLC | Radix et Rhizoma Asari |

| Shen nong she yao jiu (Qiu et al., 2018) | AAI | + | HPLC | Aristolochia fordiana |

| Tiao gu pian (Lin et al., 2014) | AAI | 2.860–6.250 | HPLC | Radix et Rhizoma Asari |

| Wan tong jin gu pian (Tian and Wang, 2007) | AAI | 2.403–4.779 | RP-HPLC | Radix et Rhizoma Asari |

| Wu wei zha xun wan (Ni and Yang, 2012) | AAI | 260–280 | HPLC | Fructus Aristolochiae |

| Xiao feng zhi yang ke li (Zhang and Wang, 2012) | AAI | − | LC-MS | Caulis Akebiae |

| Xiao qing long ke li (Guan et al., 2005) | AAI | 2.86 | RP-HPLC | Radix et Rhizoma Asari |

| Xiao qing long tang (Kuo et al., 2010) | AAI | 0.194 | LC/MS | Radix et Rhizoma Asari |

| Xiao Zhong zhi tong ding (Tang et al., 2012; He et al., 2013) | AAI | + | LC-MS/MS, SPE-HPLC | Radix et Rhizoma Asari |

| Xiao Zhong zhi tong ting (Tang et al., 2012; He et al., 2013) | AAI | + | HPLC | Radix et Rhizoma Asari |

| Xin ma zhi ke ke li (Chen et al., 2007) | AAI | − | HPLC | Radix et Rhizoma Asari |

| Xin qin ke li (Ge et al., 2010) | AAI | − | HPLC, SPE-HPLC | Radix et Rhizoma Asari |

| Xin sheng ke li (Ren et al., 2010) | AAI | − | HPLC | Radix et Rhizoma Asari |

| Xi xin pei fang ke li (Pan and Gan, 2009) | AAI | − | LC-MS/MS | Radix et Rhizoma Asari |

| Yang xue qing nao ke li (Li et al., 2007) | AAI | − | HPLC, LC-MS | Radix et Rhizoma Asari |

| Yang yin jiang ya jiao nang (Ran et al., 2016) | AAI | 1129–1458 | HPLC | Radix Aristolochiae |

| Yi shen juan bi wan (Wang et al., 2017) | AAI | − | HPLC | Herba Aristolochiae Mollissimae |

| Zhui feng tou gu capsule (Lv, 2015) | AAI | − | HPLC | Radix et Rhizoma Asari |

| Zhu sha lian jiao nang (Chen, 2003) | AAI | 1160–4521 | HPLC | Radix Aristolochiae Cinnabarinae |

Contents of Aristolochic acids in Chinese patent medicine (CPM).

The unit for quantitative data is µg/g.

Aristolochic Acid-Induced Adverse Reactions

Aristolochic Acid Nephropathy

AA nephropathy (AAN) is a kind of chronic tubulointerstitial renal disease accompanied by upper tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC) in almost half of the cases (Nortier et al., 2000). In 1992, some female patients from Belgium who consumed slimming pills containing Chinese herbs suffered from rapidly progressive interstitial nephritis (Vanherweghem et al., 1993). The renal failure was characterized by extensive interstitial fibrosis with atrophy, loss of tubules, and hyperplasia of the urothelium mainly localized in the superficial cortex (Cosyns et al., 1994a; Depierreux et al., 1994). Thereafter, urothelial carcinoma occurred in more than 40% of the patients consuming these Chinese herbs (Cosyns et al., 1994b; Nortier et al., 2000; Lord et al., 2001; Nortier and Vanherweghem, 2002). After investigations, it was found that Stephania tetranda was inadvertently substituted by Aristolochia fangchi, which contained nephrotoxic constituents (AAs) leading to adverse events (Vanhaelen et al., 1994). AAs were substantiated as the chief culprit because AA-derived DNA adducts were detected in the kidneys and ureteric tissues of these patients (Schmeiser et al., 1996; Nortier et al., 2000; Lord et al., 2001). Since then, AAN has raised worldwide attention (Jadot et al., 2017). Long-term ingestion of herbal formula known or suspected to contain AAs is one of the prominent risk factors for developing AAN (Jia et al., 2005; Vervaet et al., 2017). Although the sale and use of AA-containing products are banned or restricted in most of the countries (Krell and Stebbing, 2013), AAN induced by numerous herbal remedies and products are still reported from all over the world (Lord et al., 1999; Yang et al., 2006; Debelle et al., 2008; Shaohua et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2012; Vaclavik et al., 2014; Ban et al., 2018).

Generally, most AAN patients display an unusually rapid progression towards end-stage renal disease. During clinical examination, mild hypertension, severe anemia, increased serum creatinine, decreased estimated glomerular filtration rate, proteinuria, glycosuria, and/or leukocyturia may be observed in most cases (Reginster et al., 1997; Meyer et al., 2000; Yang et al., 2012; Gokmen et al., 2013). More precisely, some studies reveal that microalbuminuria and proteinuria of tubular type can serve as early screening indicators of AAN (Kabanda et al., 1995; Trnacevic et al., 2017). Estimation of neutral endopeptidase, a 94-kDa ectoenzyme of the proximal tubule brush border, which is characteristically decreased in AAN patients, may also serve as an early clinical biomarker of AAN (Nortier et al., 1997). During renal tract ultrasonic inspection, shrunken kidneys are observed, which results in asymmetrical and irregular cortical outline (Gokmen et al., 2013). Microscopically, the typical findings are extensive interstitial fibrosis with atrophy and loss of tubules localized predominantly in the superficial cortex and progressing towards the inner cortex. The interstitium is remarkably hypocellular in a majority of the cases. Interstitial inflammatory infiltration is observed in some cases, and more inflammatory cells are found as compared with other renal diseases. The glomeruli are relatively spared. The collapse of the capillaries and wrinkling of the basement membrane are noticed in a few glomeruli. Glomerular lesions mainly include ischemic, microcystic, obsolescent glomeruli, occasional thrombotic microangiopathy-like lesions, and/or focal segmental sclerosis-like lesions. Multifocal thickening of interlobular and afferent arterioles and/or splitting up of peritubular capillary basement membranes may be observed, which are associated with arteriolar hyalinosis, intimal fibrous hyperplasia, and occasional mucoid arterial intimal fibrosis (Depierreux et al., 1994; Meyer et al., 2000; Stefanovic et al., 2007; Debelle et al., 2008; Jelakovic et al., 2014; Jadot et al., 2017).

Balkan Endemic Nephropathy

After AAs were substantiated as one of the main causative agents inducing rapidly progressive renal disease, some scientists proposed that the clinical and morphological features of different stages of AAN and the patterns of the famous BEN were strikingly similar. This provided a clue that BEN may also be related to AAs (Cosyns et al., 1994a; Arlt et al., 2002; Grollman et al., 2007; de Jonge and Vanrenterghem, 2008). BEN is an endemic familial but not inherited chronic renal disease, which is frequently accompanied by urothelial carcinoma of the upper urinary tract (Stefanovic et al., 2007; Miyazaki and Nishiyama, 2017). The disease is prevalent in the endemic farming villages along the tributaries of the Danube river (Stiborova et al., 2016). It has been estimated that almost 25,000 people have caught this disease, and nearly 100,000 people are still at risk (Bamias and Boletis, 2008; Pavlovic, 2013a).

Several hypotheses on the etiology of BEN have been projected in the past decades, including mycotoxins, phytotoxins, heavy metals, viruses, trace element deficiencies, and AAs (Stefanovic et al., 2006; Grollman et al., 2007; De Broe, 2012). Among these, the evidence is strongest for inadvertent chronic consumption of food contaminated with AAs leading to BEN (Grollman et al., 2007; De Broe, 2012; Bui-Klimke and Wu, 2014). Researchers assume that the BEN patients might be exposed to toxic AAs through consuming food prepared from flour contaminated with the seeds of the plants of Aristolochia family, which grow abundantly as weeds in the endemic regions (Ivic, 1969; Hranjec et al., 2005; Jelakovic et al., 2012; Grollman, 2013; Jelakovic et al., 2015b). Moreover, molecular agricultural and food chemistry investigations have been carried out to trace other possibilities on how AAs enter the human food chain. Studies have demonstrated that some crops could uptake and bioaccumulate AAs from the Aristolochia species-grown soil and water. Therefore, prolonged intake of food prepared from these crops can also result in BEN (Pavlovic et al., 2013b; Chan et al., 2016; Li et al., 2016; Gruia et al., 2018). In recent years, the definitive link between BEN and AAs has been found. AA-derived DNA adducts and hallmark A→T transversions have been detected in renal cortical and urothelial malignant tissues obtained from BEN patients (Grollman et al., 2007; Jelakovic et al., 2012).

Aristolochic Acid-Induced Urothelial Carcinoma

Apart from nephrotoxicity, AAs have also been implicated in the genesis of UTUC, which is a rare subset of urothelial malignancies occurring in the renal pelvis and upper ureter. UTUC has been so far principally correlated to AA intoxication (Miyazaki and Nishiyama, 2017). At first, scientists found progressive urothelial atypia and atypical hyperplasia in the tissue samples of Belgian patients diagnosed with slimming pill-induced nephrotoxicity (Cosyns et al., 1994a; Cosyns et al., 1994b). Subsequently, urothelial carcinoma localized in the upper urinary tract was observed in almost half of the AAN patients (Nortier et al., 2000). AA-derived DNA adducts and TP53 mutations were also found in the ureteric tissues (Cosyns et al., 1999; Lord et al., 2001), which indicated the carcinogenic potential of AAs on the urothelium. In addition, the prevalence of UTUC is extraordinarily high in BEN patients (Colin et al., 2009; Patel et al., 2014; Soria et al., 2017). The data on AA-derived DNA adducts and A→T transversions further corroborated the relationship between AAs and BEN-associated urothelial tumor (Arlt et al., 2002; Arlt et al., 2007; Schmeiser et al., 2012).

Moreover, the trend of urothelial cancer among the patients diagnosed with end-stage renal disease has been reduced with the decreased consumption of AA-containing products (Wang et al., 2014a; Wang et al., 2014b). In 2002 and 2012, the World Health Organization International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified AAs as group I carcinogen according to the available strong evidence that AA-specific DNA adducts and TP53 mutations were found in humans exposed to materials obtained from plant species containing AAs (IARC, 2002; IARC, 2012). However, despite a high mutagenic and carcinogenic potential, herbal remedies and products containing AAs are still used in Asia contributing to a high incidence of urothelial carcinoma (Chen et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2015).

Most cases of AA-induced UTUC are found during AAN inspections. Initially, only mild to moderate urothelial atypia and atypical hyperplasia were observed (Cosyns et al., 1994a). Subsequently, overwhelming disseminated pelvicalyceal urothelial atypia, malignant transformation, and/or multifocal flat transitional cell carcinoma mostly localized in the upper urinary tract were shown (Cosyns et al., 1994b; Cosyns et al., 1999). Usually, these tumors have a high mortality rate. The urothelial carcinomas are mainly of synchronous bilateral or metachronous contralateral type and are related to the cumulative exposure of AAs (Chen et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2015). In addition, AA-derived DNA adducts and TP53 mutations are clinically meaningful to explore the involvement of AAs in UTUC (Chen et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2013; Aydin et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2015).

Other Adverse Effects Induced by Aristolochic Acids

Besides UTUC, AA-mutational signatures have also been detected in other types of cancer, which indicates that AAs also display carcinogenic potentials in other organs (Rosenquist and Grollman, 2016). Clinically, patients with hepatitis B virus infection are presumed to have a higher risk of hepatocellular carcinoma if they consume AA-containing herbs (Chen et al., 2018). Genomic heterogeneity analyses provide strong evidence that AAs potentially contribute to the development of liver cancer (Poon et al., 2013; Lin et al., 2017). Recently, a specific mutational signature of AA exposure has been exhibited in whole exome sequencing of hepatocellular carcinomas, suggesting a plausible conclusion that AAs and their derivatives might be one of the culprits triggering liver cancer in Asia (Totoki et al., 2014; Letouze et al., 2017; Ng et al., 2017; Nault and Letouze, 2019). AAs can also affect the initiation and/or progression of renal cell carcinoma (Scelo et al., 2014; Jelakovic et al., 2015a; Hoang et al., 2016) or bladder urothelial tumor (Lemy et al., 2008; Poon et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2015).

More carcinogenic potentials and/or toxic effects of AAs are explored in animal studies. High risk of tumor occurrence in the fore-stomach, ear duct, small intestine, kidney, urothelial tract, liver, bladder, and/or subcutaneous regions were observed in mice, rats, and/or canines after AA administration (Mengs, 1982; Mengs, 1988; Schmeiser et al., 1990; Wang et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2018b; Jin et al., 2016). Renal toxicity of AAs is observed in both mice and rats after repeat dose (Mengs, 1987; Mengs and Stotzem, 1993). Furthermore, aristolochic acid I (AAI)-induced gastrotoxicity characterized by fore-stomach damage presents prior to renal injury (Pu et al., 2016). In addition, AAI could induce apoptotic cell death in the ovaries and testis of mice and cause severe reduction of organ size and weight (Kwak et al., 2014; Kwak and Lee, 2016).

Toxicological Properties of Aristolochic Acids

Mutational Signature of Aristolochic Acids

As mentioned above, AAs are conversed to reactive intermediates (aristolactam nitrenium ion) and bind to purines in DNA to form covalent DNA adducts. The adducts of AAs with DNA are highly persistent in human tissues (Schmeiser et al., 2014) due to the lack of recognition and/or processing by global genome nucleotide excision repair (Lukin et al., 2012; Sidorenko et al., 2012). Without effective DNA repair, predominant A→T transversions enriched on the nontranscribed gene strand in the TP53 tumor suppressor gene could form in high frequency (Moriya et al., 2011; Hoang et al., 2013). The TP53 mutations and formation of AA-derived DNA adducts are considered as biomarkers for the assessment of AA exposure (Slade et al., 2009; Stiborova et al., 2017). Mutated base adenine accounts for more than half of the mutational spectra detected in the specimens of AAN and AA-induced UTUC patients (Lord et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2012; Jelakovic et al., 2012; Hoang et al., 2013; Castells et al., 2015). Besides A→T transversions, C→T transversions also occur in a high frequency. Multiple mutations are mainly found in the TP53 hotspot region of exons 5–8, as well as exons 4 and 10 (Moriya et al., 2011; Aydin et al., 2017). In animal studies, A→T transversions were observed in the activating positions in H-ras of rats treated with AAs (Wang et al., 2011). Further, RNAs modified by AAs were at much higher frequencies than DNA (Leung and Chan, 2015).

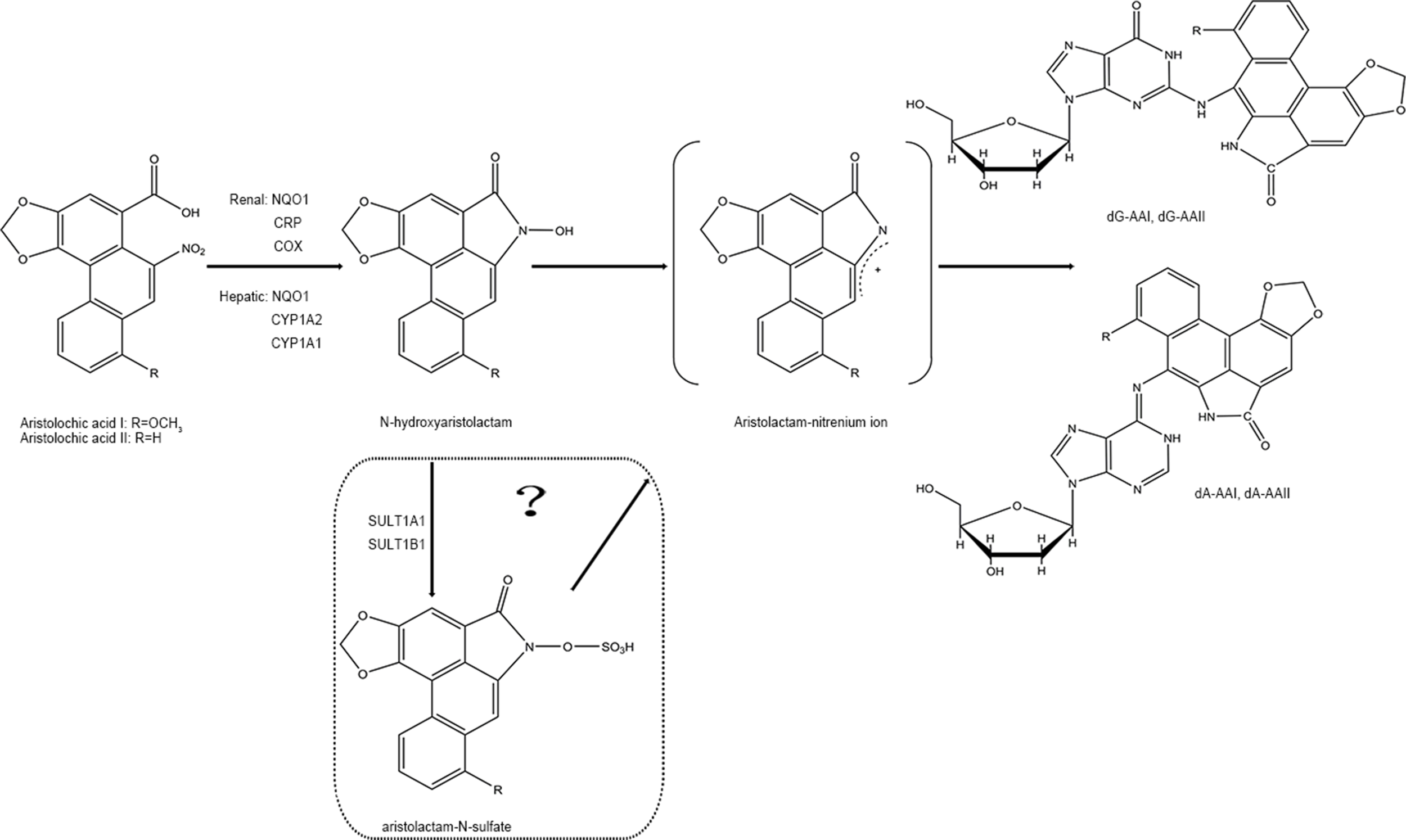

Biotransformation of Aristolochic Acids

In phase I biotransformation reaction, AAs are first transformed to N-hydroxyaristolactams (AL-NOHs) through nitroreduction reaction. After that, they are converted to aristolactam-nitrenium, which is an electrophilic cyclic aristolactam-nitrenium ion with delocalized positive charges. They preferentially bind to the exocyclic amino groups of purine bases in DNA to form AA-DNA adducts. These adducts can lead to A→T transversions and elicit renal disease and cancers (Stiborova et al., 2008b; Stiborova et al., 2008c). Both microsomal and cytosolic phase I enzymes participate in catalyzing the activation of AAs to form AA-DNA adducts consisting of 7-(deoxyadenosin-N6-yl) aristolactam I (dA-AAI), 7-(deoxyguanosin-N2-yl) aristolactam I (dG-AAI), 7-(deoxyadenosin-N6-yl) aristolactam II (dA-AAII), and 7-(deoxyguanosin-N2-yl) aristolactam II (dG-AAII) (Stiborova et al., 2005; Stiborova et al., 2008a), in which dA-AAI and dA-AAII persist for an exceptionally long time in the lesions (Lukin et al., 2012; Schmeiser et al., 2014). The dA adducts are also significantly more mutagenic than the dG adducts (Attaluri et al., 2010). According to the results from in vitro studies, among the cytosolic reductases, NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase (NQO1) plays the most important role in activation of AAs in the liver and kidney. In human renal microsomes, NADPH : CYP reductase (CPR) is proven to be more effective in activating AAs, and prostaglandin H synthase (cyclooxygenase, COX) is also involved in the reductive reaction. In human hepatic microsomes, CYP1A2 contributes maximum in the process, while CYP1A1 exhibits lesser effects and CPR plays a minor role (Stiborova et al., 2005; Stiborova et al., 2008a). Currently, the roles of the hydroxyl group on amino acids present in the active center of CYP1A1 and CYP1A2 on nitroreduction of AAs have been verified using a site-directed mutagenesis approach (Milichovsky et al., 2016). It is assumed that the genes of enzymes existing in variant forms or showing polymorphisms may be one of the factors affecting the individual’s susceptibility to AAs (Stiborova et al., 2008a). Additionally, phase II metabolisms formed by sulfation are reported to readily produce AA-DNA adducts (Sidorenko et al., 2014). It has been predicted that following reductive reactions, AL-NOHs may serve as substrates for sulfotransferases (SULTs) and convert them to N-sulfated esters, which react more efficiently with DNA (Sidorenko et al., 2014; Hashimoto et al., 2016). Among the SULTs tested, SULT1A1 and SULT1B1 displayed more activity than the other subtypes (Meinl et al., 2006; Sidorenko et al., 2014). The sulfate conjugates could be transported out of the liver via MRP membrane transporters and transferred into the kidney via organic anionic transporters (OAT), thereby inducing kidney damage (Chang et al., 2017). However, conflicting results have been observed in some other studies (Stiborova et al., 2011; Arlt et al., 2017) (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Proposed pathway for metabolic activation of AAI and AAII.

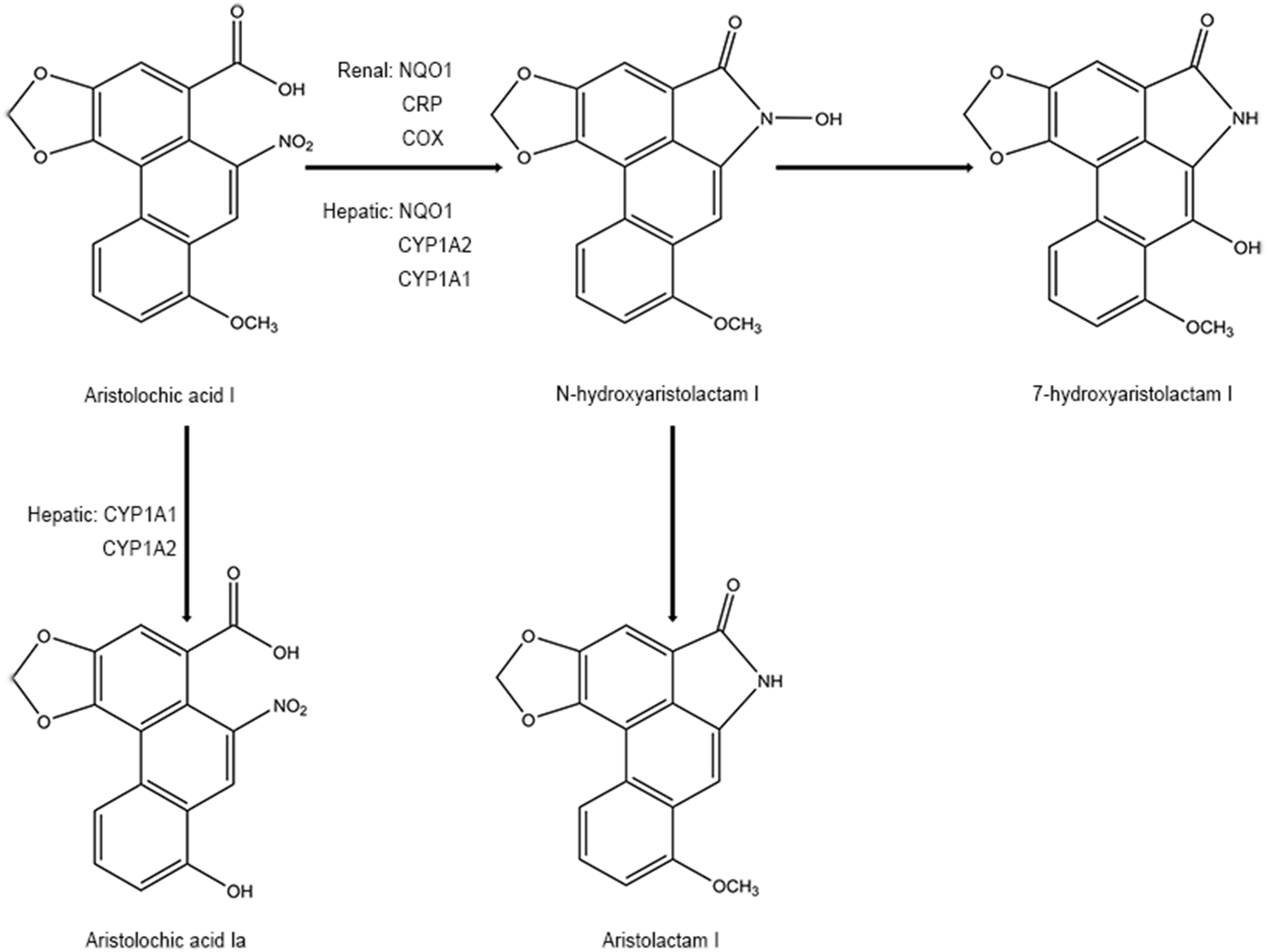

On the other hand, detoxification of AAI happens at the same time when it exerts mutagenic and cytotoxic potentials. Some studies have mentioned that N-hydroxyaristolactam I could also competitively rearrange to 7-hydroxyaristolactam I or further reductive production of aristolactam I (ALI) (Stiborova et al., 2008b; Stiborova et al., 2008c), which shows a lower capacity to form AAI-DNA adducts (Dong et al., 2006). In addition, oxidation of AAI to a lesser toxic 8-hydroxyaristolochic acid I (aristolochic acid Ia, AAIa) is also suggested to be a detoxifying pathway of AAI (Stiborova et al., 2008b; Stiborova et al., 2008c). The O-demethylated metabolites of AAI, conjugated metabolites of AAIa, are found to be excreted in the urine of AA-treated rats (Chan et al., 2007). Hepatic microsomal cytochrome P450, especially CYP1A subfamily (CYP1A1 and CYP1A2), has been found to play a critical role in suppressing the carcinogenic and nephrotoxic effects of AAI (Xiao et al., 2008; Stiborova et al., 2009; Rosenquist et al., 2010; Stiborova et al., 2012; Stiborova et al., 2015; Dracinska et al., 2016). Therefore, the CYP1A1 and 1A2 play a dual role by partly regulating the balance between reductive activation and oxidative detoxification of AAI (Figure 3). However, the analogical mechanism has not been observed in AAII yet because AAII shows much lower amenability to oxidation than AAI (Martinek et al., 2017).

Figure 3

Proposed pathway for metabolic detoxication of AAI.

Specific Organic Anion Transporters for Aristolochic Acids

The nephrotoxic damage of AAs selectively targets the proximal tubules, indicating that the toxins may specifically accumulate in these tissues. The proximal tubules take charge in the secretion and reabsorption of xenobiotics or their metabolites through several particular transporters. OAT family, a group of multispecific membrane transport proteins, contributes to the renal handling of negatively charged drugs and other organic compounds. Indeed, AAI as a low molecular weight organic anion with an anionic carboxyl group and a hydrophobic part possesses the chemical characteristics of a substrate for OAT. OAT family is, therefore, considered to be one of the pivotal determinants mediating the accumulation of AAI into the renal proximal tubules (Dickman et al., 2011). Many investigations have verified OATs, especially OAT1 and OAT3, in the basolateral membrane of the proximal tubules facilitating the uptake of AAI by renal cells, which at least partly lead to site-selective AAI-induced nephrotoxicity (Bakhiya et al., 2009; Dickman et al., 2011; Xue et al., 2011; Baudoux et al., 2012). In addition, the phase II metabolite of AAI, sulfate-conjugated AL-I (sulfonyloxyaristolactam, AL-I-NOSO3) is reported to be transported into kidney via OAT1, OAT3, and OAT4 (Chang et al., 2017).

Other Mechanisms Involved in Aristolochic Acid-Induced Adverse Reactions

The chemical structures of AAs are considered as critical determinants of their toxic effects. According to the current knowledge, AAI is solely responsible for nephrotoxicity (Shibutani et al., 2007) and has more cytotoxicity than AAII (Balachandran et al., 2005). On the other hand, AAII may show higher or similar genotoxic and carcinogenic potentials as AAI (Shibutani et al., 2007; Xing et al., 2012). In reductive reactions, NQO1 is more effective in activating of AAI than AAII (Martinek et al., 2011), and the extent of AAI-DNA adducts is much higher than that of AAII-DNA adducts in most in vitro enzymatic systems (Schmeiser et al., 1997). During phase II metabolism, ALI-DNA adducts are also formed more efficiently than ALII-DNA adducts in SULT1B1 (Sidorenko et al., 2014). In addition, similar CYP-mediated oxidative detoxification reactions of AAI are not observed in AAII (Martinek et al., 2017). The difference on enzymatic conversion of AAI and AAII is considered to relate to their chemical structures.

In recent years, more than 30 microRNAs differentially expressed in patients exposed to AAs have been explored, which might improve the understanding of the pathogenesis of AA-related renal disease and cancer. It has been speculated that FGFR3, Akt, mucin type O-glycan biosynthesis, ECM receptor interaction pathways, and other biological mechanisms might be involved in the occurrences of AAN, BEN, and/or AA-induced UTUC (Tao et al., 2015; Lv et al., 2016; Popovska-Jankovic et al., 2016). Meanwhile, 15% of the 417 detectable miRNAs have been found to be altered by AAs in rats (Li et al., 2015). During exome sequencing of genes in DNA samples from BEN patients, possible deleterious/damaging variants—CELA1, HSPG2, and KCNK5—are detected. These genes could encode proteins connected to the process of angiogenesis (Toncheva et al., 2014), which is tightly correlated with BEN and UTUC (Jankovic-Velickovic et al., 2012).

Some studies have focused on the contributions of innate and adaptive immunity in the progression of AAN (Sato et al., 2004; Pozdzik et al., 2010). In the kidney specimens, interstitial inflammatory infiltration is dramatically observed in the tubulointerstitial lesions, and massive infiltration of macrophages and T and B lymphocytes is demonstrated in the medullary rays and outer medullae, implying the onset of immune response (Pozdzik et al., 2010). Animal study has suggested that AAs increase the proportion of myeloid CD11bhighF4/80mid and decrease their counterpart. CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells could provide protection against AA-induced acute tubular necrosis (Baudoux et al., 2018). However, this view is still debatable as AAI is also reported to damage the epithelial cells lining the proximal renal tubule due to direct toxic effects instead of immune actions (Yi et al., 2018).

Meanwhile, AAs could cause increased oxidative stress leading to impaired renal function. AAI elicits oxidative stress-related DNA damage through depleting antioxidant glutathione in the human renal proximal tubular cells (Yu et al., 2011a; Yu et al., 2011b) and induces increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) and tubular apoptosis via decreasing nitric oxide availability in mice (Decleves et al., 2016).

Inflammatory and fibrotic pathways and dynamic changes in fatty acid, phospholipid, and glycerolipid metabolisms are all linked to AAN (Zhao et al., 2015). Additionally, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-related signaling pathways are considered to be associated with nephrotoxicity and reproductive toxicity of AAI. AAI could upregulate the expression of phospho-ERK1/2 in cells, which contributes to ROS generation (Yu et al., 2011a; Yu et al., 2011b). AAs also activate JNK signaling pathway and elicit the overexpression of TGF-1, which is critically involved in the pathogenesis of AAN (Rui et al., 2012). Interestingly, some other studies have described that AAI inhibits Akt and/or ERK1/2 phosphorylation, impedes relevant apoptosis, and causes severe injury resulting in the development of ovarian and testis in mice (Kwak et al., 2014; Kwak and Lee, 2016; Yu et al., 2011b). Besides, NFκb, aryl hydrocarbon receptor, and cell cycle signaling are also modulated in the kidneys of AA-treated mice (Arlt et al., 2011). In addition, the loss of functional TASK-2 channels may indirectly increase the susceptibility to the toxic effects of AAs (Veale and Mathie, 2016). The decrease in pro-apoptotic protein Bax can predict the development of AA-induced UTUC (Jankovic-Velickovic et al., 2011).

Conclusion

AAs have been recognized as a group of potent nephrotoxin and carcinogen. The consumption of AA-containing foods can cause permanent kidney injury, end-stage renal disease, and even UTUC. AA-derived DNA adducts are recognized as specific biomarkers for the assessment of AA exposure. A characteristically mutational signature of A→T transversions observed in the tumor tissues also implies the exposure of AAs. So far, the underlying etiological mechanisms of AA-induced renal disease and UTUC have been preliminarily revealed, although the detailed mechanisms are far from being completely understood. In addition, various enzymes, organic anion transporters, and molecular mechanisms might be involved in AA-induced damages. Therapy for AAN and AA-induced UTUC remains a serious challenge. AA-related adverse events are still widely reported, especially in the Asian and Balkan regions. AAs have now been listed as group I carcinogen by IARC (IARC, 2002; IARC, 2012). The US Food and Drug Administration and regulatory authorities of some other countries have issued alerts against the use and import of products containing AAs (Zhang et al., 2019). However, in China and some countries, products containing herb preparations from Aristolochia and Asarum are still used, and food contaminated by AAs cause health problems in some countries (Ioset et al., 2003; Wooltorton, 2004; Hsieh et al., 2008; Michl et al., 2013; Ardalan et al., 2015; Cachet et al., 2016; Abdullah et al., 2017). Therefore, the use of AA-containing herbal medications and consumption of food contaminated by AAs may still impose high risk, and hence, more strict precautions should be taken to protect the public from AA exposure.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Science and Technology Major Project (2015ZX09501004-003-001 and 2018ZX09101002-003), Beijing Science and Technology Projects (Z151100000115012 and Z161100004916025), and China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences Foundation (ZZ10-025 and ZZ12-001).

Statements

Author contributions

JH, ZX, and JL are the major writers of the manuscript. YZ has drawn the pictures. AL has overseen the writing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1

Abdullah R. Diaz L. N. Wesseling S. Rietjens I. M. (2017). Risk assessment of plant food supplements and other herbal products containing aristolochic acids using the margin of exposure (MOE) approach. Food Addit. Contam. Part A Chem. Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess.34 (2), 135–144. doi: 10.1080/19440049.2016.1266098

2

Ardalan M. R. Khodaie L. Nasri H. Jouyban A. (2015). Herbs and hazards: risk of aristolochic acid nephropathy in Iran. Iran J. Kidney Dis.9 (1), 14–17. doi: http://dx.doi.org/

3

Arlt V. M. Ferluga D. Stiborova M. Pfohl-Leszkowicz A. Vukelic M. Ceovic S. et al . (2002). Is aristolochic acid a risk factor for Balkan endemic nephropathy-associated urothelial cancer? Int. J. Cancer101 (5), 500–502. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10602

4

Arlt V. M. Meinl W. Florian S. Nagy E. Barta F. Thomann M. et al . (2017). Impact of genetic modulation of SULT1A enzymes on DNA adduct formation by aristolochic acids and 3-nitrobenzanthrone. Arch. Toxicol.91 (4), 1957–1975. doi: 10.1007/s00204-016-1808-6

5

Arlt V. M. Stiborova M. Brocke J. Simoes M. L. Lord G. M. Nortier J. L. et al . (2007). Aristolochic acid mutagenesis: molecular clues to the aetiology of Balkan endemic nephropathy-associated urothelial cancer. Carcinogenesis28 (11), 2253–2261. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm082

6

Arlt V. M. Zuo J. Trenz K. Roufosse C. A. Lord G. M. Nortier J. L. et al . (2011). Gene expression changes induced by the human carcinogen aristolochic acid I in renal and hepatic tissue of mice. Int. J. Cancer128 (1), 21–32. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25324

7

Attaluri S. R. Bonala R. Yang I. Y. Lukin M. A. Wen Y. Grollman A. P. et al . (2010). DNA adducts of aristolochic acid II: total synthesis and site-specific mutagenesis studies in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res.38 (1), 339–352. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp815

8

Aydin S. Ambroise J. Cosyns J. P. Gala J. L. (2017). TP53 mutations in p53-negative dysplastic urothelial cells from Belgian AAN patients: new evidence for aristolochic acid-induced molecular pathogenesis and carcinogenesis. Mutat. Res.818, 17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2017.03.003

9

Aydin S. Dekairelle A. F. Ambroise J. Durant J. F. Heusterspreute M. Guiot Y. et al . (2014). Unambiguous detection of multiple TP53 gene mutations in AAN-associated urothelial cancer in Belgium using laser capture microdissection. PLoS One9 (9), e106301. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106301

10

Bakhiya N. Arlt V. M. Bahn A. Burckhardt G. Phillips D. H. Glatt H. (2009). Molecular evidence for an involvement of organic anion transporters (OATs) in aristolochic acid nephropathy. Toxicology264 (1–2), 74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2009.07.014

11

Balachandran P. Wei F. Lin R. C. Khan I. A. Pasco D. S. (2005). Structure activity relationships of aristolochic acid analogues: toxicity in cultured renal epithelial cells. Kidney Int.67 (5), 1797–1805. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00277.x

12

Bamias G. Boletis J. (2008). Balkan nephropathy: evolution of our knowledge. Am. J. Kidney Dis.52 (3), 606–616. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.05.024

13

Ban T. H. Min J. W. Seo C. Kim D. R. Lee Y. H. Chung B. H. et al . (2018). Update of aristolochic acid nephropathy in Korea. Korean J. Intern. Med.33 (5), 961–969. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2016.288

14

Baudoux T. Husson C. De Prez E. Jadot I. Antoine M. H. Nortier J. L. et al . (2018). CD4+ and CD8+ T cells exert regulatory properties during experimental acute aristolochic acid nephropathy. Sci. Rep.8 (1), 5334. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-23565-2

15

Baudoux T. E. Pozdzik A. A. Arlt V. M. De Prez E. G. Antoine M. H. Quellard N. et al . (2012). Probenecid prevents acute tubular necrosis in a mouse model of aristolochic acid nephropathy. Kidney Int.82 (10), 1105–1113. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.264

16

Bhattacharjee P. Bera I. Chakraborty S. Ghoshal N. Bhattacharyya D. (2017). Aristolochic acid and its derivatives as inhibitors of snake venom L-amino acid oxidase. Toxicon138, 1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2017.08.003

17

Bui-Klimke T. Wu F. (2014). Evaluating weight of evidence in the mystery of Balkan endemic nephropathy. Risk Anal.34 (9), 1688–1705. doi: 10.1111/risa.12239

18

Cachet X. Langrand J. Bottai C. Dufat H. Locatelli-Jouans C. Nossin E. et al . (2016). Detection of aristolochic acids I and II in “Chiniy-tref”, a traditional medicinal preparation containing caterpillars feeding on Aristolochia trilobata L. Toxicon114, 28–30. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2016.02.013

19

Castells X. Karanovic S. Ardin M. Tomic K. Xylinas E. Durand G. et al . (2015). Low-coverage exome sequencing screen in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumors reveals evidence of exposure to carcinogenic aristolochic acid. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev.24 (12), 1873–1881. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0553

20

Chan W. Luo H. B. Zheng Y. Cheng Y. K. Cai Z. (2007). Investigation of the metabolism and reductive activation of carcinogenic aristolochic acids in rats. Drug Metab. Dispos.35 (6), 866–874. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.013979

21

Chan W. Pavlovic N. M. Li W. Chan C. K. Liu J. Deng K. et al . (2016). Quantitation of aristolochic acids in corn, wheat grain, and soil samples collected in serbia: identifying a novel exposure pathway in the etiology of Balkan endemic nephropathy. J. Agric. Food Chem.64 (29), 5928–5934. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b02203

22

Chang S. Y. Weber E. J. Sidorenko V. S. Chapron A. Yeung C. K. Gao C. et al . (2017). Human liver-kidney model elucidates the mechanisms of aristolochic acid nephrotoxicity. JCI Insight2 (22). doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.95978

23

Chen C. H. Dickman K. G. Huang C. Y. Moriya M. Shun C. T. Tai H. C. et al . (2013). Aristolochic acid-induced upper tract urothelial carcinoma in Taiwan: clinical characteristics and outcomes. Int. J. Cancer133 (1), 14–20. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28013

24

Chen C. H. Dickman K. G. Moriya M. Zavadil J. Sidorenko V. S. Edwards K. L. et al . (2012). Aristolochic acid-associated urothelial cancer in Taiwan. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.109 (21), 8241–8246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119920109

25

Chen C. J. Yang Y. H. Lin M. H. Lee C. P. Tsan Y. T. Lai M. N. et al . (2018). Herbal medicine containing aristolochic acid and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis B virus infection. Int. J. Cancer. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31544

26

Chen L. Xie B. (2004). Determination of the contents of aristolochic acid in Ganluxiaodu Pills by RP-HPLC. J. Zhejiang Chin. Med. Univ.28 (2), 73–74. doi: 10.16466/j.issn1005-5509.2004.02.045

27

Chen J. Li Y. Meng S. Guo M. (2007). Determination of aristolochic acid in Xinmazhike Granules. Lishizhen Med. Mater. Med. Res.18 (11), 2725–2726. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1008-0805.2007.11.068

28

Chen Y. (2003). Determination of the contents of aristolochic acid A in Zhushalian Capsule by HPLC. J. Chongqing Med. Univ.28 (1), 84–86. doi: 10.13406/j.cnki.cyxb.2003.01.027

29

Chen Y. Hang Z. Liu Y. Liu Y. Liu Q. Yi J. (2009). Analysis of aristolochic acid A in Ershiwuweiluronghao Pills. Chin. J. Pharm. Anal.29 (9), 1458–1461. doi: 10.16155/j.0254-1793.2009.09.006

30

Colin P. Koenig P. Ouzzane A. Berthon N. Villers A. Biserte J. et al . (2009). Environmental factors involved in carcinogenesis of urothelial cell carcinomas of the upper urinary tract. BJU Int.104 (10), 1436–1440. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08838.x

31

Cosyns J. P. Jadoul M. Squifflet J. P. De Plaen J. F. Ferluga D. van Ypersele de Strihou C. (1994a). Chinese herbs nephropathy: a clue to Balkan endemic nephropathy? Kidney Int.45 (6), 1680–1688. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.220

32

Cosyns J. P. Jadoul M. Squifflet J. P. Van Cangh P. J. van Ypersele de Strihou C. (1994b). Urothelial malignancy in nephropathy due to Chinese herbs. Lancet344 (8916), 188. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(94)92786-3

33

Cosyns J. P. Jadoul M. Squifflet J. P. Wese F. X. van Ypersele de Strihou C. (1999). Urothelial lesions in Chinese-herb nephropathy. Am. J. Kidney Dis.33 (6), 1011–1017. doi: 10.1016/S0272-6386(99)70136-8

34

De Broe M. E. (2012). Chinese herbs nephropathy and Balkan endemic nephropathy: toward a single entity, aristolochic acid nephropathy. Kidney Int.81 (6), 513–515. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.428

35

de Jonge H. Vanrenterghem Y. (2008). Aristolochic acid: the common culprit of Chinese herbs nephropathy and Balkan endemic nephropathy. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant.23 (1), 39–41. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm667

36

Debelle F. D. Vanherweghem J. L. Nortier J. L. (2008). Aristolochic acid nephropathy: a worldwide problem. Kidney Int.74 (2), 158–169. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.129

37

Decleves A. E. Jadot I. Colombaro V. Martin B. Voisin V. Nortier J. et al . (2016). Protective effect of nitric oxide in aristolochic acid-induced toxic acute kidney injury: an old friend with new assets. Exp. Physiol.101 (1), 193–206. doi: 10.1113/EP085333

38

Depierreux M. Van Damme B. Vanden Houte K. Vanherweghem J. L. (1994). Pathologic aspects of a newly described nephropathy related to the prolonged use of Chinese herbs. Am. J. Kidney Dis.24 (2), 172–180. doi: 10.1016/S0272-6386(12)80178-8

39

Dickman K. G. Sweet D. H. Bonala R. Ray T. Wu A. (2011). Physiological and molecular characterization of aristolochic acid transport by the kidney. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther.338 (2), 588–597. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.180984

40

Ding H. Shen J. Fei W. Qian Y. Xie T. Liu Q. (2018). Determination of aristolochic acid A, B, C, D in aristolochia herbs by UPLC-MS/MS. Chin. J. Ethnomed. Ethnopharmacy27 (18), 38–43.

41

Dong H. Suzuki N. Torres M. C. Bonala R. R. Johnson F. Grollman A. P. et al . (2006). Quantitative determination of aristolochic acid-derived DNA adducts in rats using 32P-postlabeling/polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis. Drug Metab. Dispos.34 (7), 1122–1127. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.008706

42

Dong S. Shang M. Wang X. Zhang S. Li C. Cai S. (2009). Chemical constituents isolated from Saruma henryi. J. Chin. Pharm. Sci.18 (2), 146–150.

43

Dracinska H. Barta F. Levova K. Hudecova A. Moserova M. Schmeiser H. H. et al . (2016). Induction of cytochromes P450 1A1 and 1A2 suppresses formation of DNA adducts by carcinogenic aristolochic acid I in rats in vivo. Toxicology, 344–346, 7–18. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2016.01.011

44

Gan S. Han T. Liu H. Shi X. Wu C. (2013). Determination of aristolochic acid A in Qingxueneixiao Pills by LC-MS-MS. Chin. J. Exp. Tradit. Med. Formulae19 (16), 163–167. doi: 10.11653/syfj2013160163

45

Ge X. Zhang Y. Cai X. Wu C. Wang H. (2010). Limit test for aristolochic acid A in Xinqin Granules by HPLC. Chin. J. Pharm.41 (8), 604–606.

46

Gokmen M. R. Cosyns J. P. Arlt V. M. Stiborova M. Phillips D. H. Schmeiser H. H. et al . (2013). The epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of aristolochic acid nephropathy: a narrative review. Ann. Int. Med.158 (6), 469–477. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-6-201303190-00006

47

Gold L. S. Slone T. H. (2003). Aristolochic acid, an herbal carcinogen, sold on the web after FDA alert. N. Engl. J. Med.349 (16), 1576–1577. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200310163491619

48

Grollman A. P. (2013). Aristolochic acid nephropathy: harbinger of a global iatrogenic disease. Environ. Mol. Mutagen.54 (1), 1–7. doi: 10.1002/em.21756

49

Grollman A. P. Shibutani S. Moriya M. Miller F. Wu L. Moll U. et al . (2007). Aristolochic acid and the etiology of endemic (Balkan) nephropathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.104 (29), 12129–12134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701248104

50

Gruia A. T. Oprean C. Ivan A. Cean A. Cristea M. Draghia L. et al . (2018). Balkan endemic nephropathy and aristolochic acid I: an investigation into the role of soil and soil organic matter contamination, as a potential natural exposure pathway. Environ. Geochem. Health40 (4), 1437–1448. doi: 10.1007/s10653-017-0065-9

51

Guan W. Li X. Xiao J. (2005). Determination of the contents of aristolochic acid in Asari Radix et Rhizoma and its preparations by reversible high performance liquid chromatography. Chin. Remedies Clinics5 (4), 283–285. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-2560.2005.04.013

52

Han N. Lu J. Bi K. Du X. Zhou Y. Zhou J. (2008). Assaying of aristolochic acid A in 14 traditional Chinese medicines by RP-HPLC. J. Shenyang Pharm. Univ.25 (2), 115–118. doi: 10.14066/j.cnki.cn21-1349/r.2008.02.005

53

Hashimoto K. Higuchi M. Makino B. Sakakibara I. Kubo M. Komatsu Y. et al . (1998). Quantitative analysis of aristolochic acids, toxic compounds, contained in some medicinal plants. J. Ethnopharmacol.64 (1999), 185–189. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(98)00123-8

54

Hashimoto K. Higuchi M. Fau-Makino B. Makino B. Fau-Sakakibara I. Sakakibara I Fau-Kubo M. Kubo M Fau-Komatsu Y. Komatsu Y Fau-Maruno M. et al . (1999). Quantitative analysis of aristolochic acids, toxic compounds, contained in some medicinal plants. J. Ethnopharmacol.64 (2), 185–189. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(98)00123-8

55

Hashimoto K. Zaitseva I. N. Bonala R. Attaluri S. Ozga K. Iden C. R. et al . (2016). Sulfotransferase-1A1-dependent bioactivation of aristolochic acid I and N-hydroxyaristolactam I in human cells. Carcinogenesis37 (7), 647–655. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgw045

56

He S. Tang X. Sang T. Zhao X. Xie T. (2013). Content determination of aristolochic acid A in Xiaozhongzhitong Tincture by LC-MS/MS. China Pharmacy24 (20), 1907–1909. doi: 10.6039/j.issn.1001-0408.2013.20.31

57

Heinrich M. Chan J. Wanke S. Neinhuis C. Simmonds M. S. (2009). Local uses of Aristolochia species and content of nephrotoxic aristolochic acid 1 and 2-a global assessment based on bibliographic sources. J. Ethnopharmacol.125 (1), 108–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.05.028

58

Hoang M. L. Chen C. H. Chen P. C. Roberts N. J. Dickman K. G. Yun B. H. et al . (2016). Aristolochic acid in the etiology of renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev.25 (12), 1600–1608. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0219

59

Hoang M. L. Chen C. H. Sidorenko V. S. He J. Dickman K. G. Yun B. H. et al . (2013). Mutational signature of aristolochic acid exposure as revealed by whole-exome sequencing. Sci. Transl. Med.5 (197), 197ra102. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006200

60

Hranjec T. Kovac A. Kos J. Mao W. Chen J. J. Grollman A. P. et al . (2005). Endemic nephropathy: the case for chronic poisoning by aristolochia. Croat Med. J.46 (1), 116–125. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1040752

61

Hsieh S. C. Lin I. H. Tseng W. L. Lee C. H. Wang J. D. (2008). Prescription profile of potentially aristolochic acid containing Chinese herbal products: an analysis of National Health Insurance data in Taiwan between 1997 and 2003. Chin. Med.3, 13. doi: 10.1186/1749-8546-3-13

62

Hu S. L. Zhang H. Q. Chan K. Mei Q. X. (2004). Studies on the toxicity of Aristolochia manshuriensis (Guanmuton). Toxicology198 (1–3), 195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2004.01.026

63

Huang K. Zhu X. (2015). Determination of aristolochic acid I in Liujingtoutong Tablet by SPE-HPLC. Tianjin Pharmacy27 (5), 9–11. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-5687.2015.05.003

64

Huang Q. Zheng W. Chi Z. Lin G. (2009). Limit detection of aristolochic acid A in Jiangusujin Tablet by HPLC. Strait Pharm. J.21 (11), 74–75. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-3765.2009.11.033

65

IARC (2002). Some traditional herbal medicines, some mycotoxins, naphthalene and styrene. IARC Monogr. Eval. Carcinog. Risks Hum.82, 1–556.

66

IARC (2012). Pharmaceuticals. IARC Monogr. Eval. Carcinog. Risks Hum.100 (Pt A), 1–401.

67

Ioset J. R. Raoelison G. E. Hostettmann K. (2003). Detection of aristolochic acid in Chinese phytomedicines and dietary supplements used as slimming regimens. Food Chem. Toxicol.41 (1), 29–36. doi: 10.1016/S0278-6915(02)00219-3

68

Ivic M. (1969). Etiology of endemic nephropathy. Lijec. Vjesn.91 (12), 1273–1281.

69

Jadot I. Decleves A. E. Nortier J. Caron N. (2017). An Integrated view of aristolochic acid nephropathy: update of the literature. Int. J. Mol. Sci.18 (2). doi: 10.3390/ijms18020297

70

Jankovic-Velickovic L. Stojnev S. Ristic-Petrovic A. Dolicanin Z. Hattori T. Mukaisho K. et al . (2011). Pro- and antiapoptotic markers in upper tract urothelial carcinoma associated with Balkan endemic nephropathy. Sci. World J.11, 1699–1711. doi: 10.1100/2011/752790

71

Jankovic-Velickovic L. Ristic-Petrovic A. Stojnev S. Dolicanin Z. Hattori T. Sugihara H. et al . (2012). Angiogenesis in upper tract urothelial carcinoma associated with Balkan endemic nephropathy. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol.5 (7), 674–683. doi: 10.5114/fn.2012.30530

72

Jelakovic B. Castells X. Tomic K. Ardin M. Karanovic S. Zavadil J. (2015a). Renal cell carcinomas of chronic kidney disease patients harbor the mutational signature of carcinogenic aristolochic acid. Int. J. Cancer136 (12), 2967–2972. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29338

73

Jelakovic B. Karanovic S. Vukovic-Lela I. Miller F. Edwards K. L. Nikolic J. et al . (2012). Aristolactam-DNA adducts in the renal cortex: biomarker of environmental exposure to aristolochic acid. Kidney Int.81 (6), 559–567. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.371

74

Jelakovic B. Nikolic J. Radovanovic Z. Nortier J. Cosyns J. P. Grollman A. P. et al . (2014). Consensus statement on screening, diagnosis, classification and treatment of endemic (Balkan) nephropathy. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant.29 (11), 2020–2027. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft384

75

Jelakovic B. Vukovic Lela I. Karanovic S. Dika Z. Kos J. Dickman K. et al . (2015b). Chronic dietary exposure to aristolochic acid and kidney function in native farmers from a Croatian endemic area and Bosnian immigrants. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol.10 (2), 215–223. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03190314

76

Jia W. Zhao A. Gao W. Chen M. Xiao P. (2005). New perspectives on the Chinese herbal nephropathy. Phytother. Res.19 (11), 1001–1002. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1676

77

Jiang Y. Hu L. Hao F. (2007). Determination of the contents of cinnamic acid and aristolochic acid A in two Guanxinsuhe Pills by RP-HPLC. Chin. Traditional Patent Med.29 (4), 599–601. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-1528.2007.04.048

78

Jin K. Su K. K. Li T. Zhu X. Q. Wang Q. Ge R. S. et al . (2016). Hepatic premalignant alterations triggered by human nephrotoxin aristolochic acid I in canines. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila)9 (4), 324–334. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-15-0339

79

Jou J. H. Li C. Y. Schelonka E. P. Lin C. H. Wu T. S. (2004). Analysis of the analogues of aristolochic acid and aristolactam in the plant of Aristolochia genus by HPLC. J. Food Drug Anal.12 (1), 40–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2003.11.005

80

Jou J. H. Chen S. Wu T. S. (2003). Facile reversed-phase HPLC resolution and quantitative determination of aristolochic acid and aristolactam analogues in traditional Chinese medicine. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol.26 (18), 3057–3068. doi: 10.1081/JLC-120025422

81

Kabanda A. Jadoul M. Lauwerys R. Bernard A. van Ypersele de Strihou C. (1995). Low molecular weight proteinuria in Chinese herbs nephropathy. Kidney Int.48 (5), 1571–1576. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.449

82

Kang D. Li T. (2008). Determination the content of aristolochic acid A in Hanshibi Granules by HPLC. China Med. Her.5 (33), 17–18. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-7210.2008.33.011

83

Kong D. Gao H. Li X. Lu J. Dan Y. (2015). Rapid determination of eight aristolochic acid analogues in five Aristolochiaceae plants by ultra-high performance liquid chromatography quadrupole/time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J. Chin. Pharm. Sci.24 (6), 364–375. doi: 10.5246/jcps.2015.06.047

84

Krell D. Stebbing J. (2013). Aristolochia: the malignant truth. Lancet Oncol.14 (1), 25–26. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70596-X

85

Kuo C. H. Lee C. W. Lin S. C. Tsai I. L. Lee S. S. Tseng Y. J. et al . (2010). Rapid determination of aristolochic acids I and II in herbal products and biological samples by ultra-high-pressure liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Talanta80 (5), 1672–1680. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2009.10.003

86

Kuo P. C. Li Y. C. Wu T. S. (2012). Chemical constituents and pharmacology of the Aristolochia (madou ling) species. J. Tradit. Complement Med.2 (4), 249–266. doi: 10.1016/S2225-4110(16)30111-0

87

Kwak D. H. Lee S. (2016). Aristolochic acid I causes testis toxicity by inhibiting Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Chem. Res. Toxicol.29 (1), 117–124. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.5b00467

88

Kwak D. H. Park J. H. Lee H. S. Moon J. S. Lee S. (2014). Aristolochic acid I induces ovarian toxicity by inhibition of Akt phosphorylation. Chem. Res. Toxicol.27 (12), 2128–2135. doi: 10.1021/tx5003854

89

Lemy A. Wissing K. M. Rorive S. Zlotta A. Roumeguere T. Muniz Martinez M. C. et al . (2008). Late onset of bladder urothelial carcinoma after kidney transplantation for end-stage aristolochic acid nephropathy: a case series with 15-year follow-up. Am. J. Kidney Dis.51 (3), 471–477. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.11.015

90

Letouze E. Shinde J. Renault V. Couchy G. Blanc J. F. Tubacher E. et al . (2017). Mutational signatures reveal the dynamic interplay of risk factors and cellular processes during liver tumorigenesis. Nat. Commun.8 (1), 1315. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01358-x

91

Leung E. M. Chan W. (2015). Comparison of DNA and RNA adduct formation: significantly higher levels of RNA than DNA modifications in the internal organs of aristolochic acid-dosed rats. Chem. Res. Toxicol.28 (2), 248–255. doi: 10.1021/tx500423m

92

Li G. Chen S. Wu L. Chen J. Zhang J. Li X. et al . (2017). Determination of aristolochic acid I in traditional Chinese medicine by UPLC-QQQ-MS. Chin. J. Exp. Tradit. Med. Formulae23 (13), 61–65. doi: 10.13422/j.cnki.syfjx.2017130061

93

Li L. Gao H. Wang Z. Wang W. (2006). Determination of aristolochic acid A in Guanxinsuhe Preparations by RP-HPLC. China J. Chin. Mater. Med.31 (2), 122–124. doi: 10.3321/j.issn:1001-5302.2006.02.009

94

Li Q. Liu Y. Chang Y. Wang L. Jia R. Zhao Y. (2009). Qingnaozhitong Capsule of aristolochic acid A limited determination. Spec. Wild Econ. Anim. Plant Res.31 (4), 61–64. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-4721.2009.04.021

95

Li W. Han J. Gao J. Liu C. (2007). Determination of aristolochic acid A in Rhizoma Asari and Yangxueqingnao Granules using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Chin. J. Anal. Chem.35 (12), 1798–1800. doi: 10.3321/j.issn:0253-3820.2007.12.025

96

Li W. Hu Q. Chan W. (2016). Uptake and accumulation of nephrotoxic and carcinogenic aristolochic acids in food crops grown in Aristolochia Clematitis-contaminated soil and water. J. Agric. Food Chem.64 (1), 107–112. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b05089

97

Li Y. L. Tian M. Yu J. Shang M. Y. Cai S. Q. (2010). Studies on morphology and aristolochic acid analogue constituents of Asarum campaniflorum and a comparison with two official species of Asari radix et rhizoma. J. Nat. Med.64 (4), 442–451. doi: 10.1007/s11418-010-0433-6

98

Li Z. Qin T. Wang K. Hackenberg M. Yan J. Gao Y. et al . (2015). Integrated microRNA, mRNA, and protein expression profiling reveals microRNA regulatory networks in rat kidney treated with a carcinogenic dose of aristolochic acid. BMC Genomics16, 365. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1516-2

99

Liang A. Gao Y. Zhang B. (2017). Safety problems and measures of traditional Chinese medicine containing aristolochic acid. China Food Drug Admin. Mag.11, 17–20.

100

Lin D. C. Mayakonda A. Dinh H. Q. Huang P. Lin L. Liu X. et al . (2017). Genomic and epigenomic heterogeneity of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res.77 (9), 2255–2265. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-2822

101

Lin W. Chen X. Liu K. (2014). Determination of aristolochic acid A in Tiaogu Tablets. Asia-Pac. Tradit. Mediine.10 (10), 37–38. doi: 10.1111/ajco.12307

102

Liu C. Chen Y. Zhao X. Gong L. Wang L. (2003). Determination of aristolochic acid A in Aristolochia mollissima Hance by RP-HPLC. Chin. Traditional Herbal Drugs34 (12), 87–89. doi: 10.7501/j.issn.0253-2670.2003.12.2003012619

103

Liu F. Li Z. Nie L. Axia A. Yuan R. Wang J. (2015). Determination of aristolochic acids A and heavy metals in Tibetan medicine-Ershiwuweishanhu Pills. J. Tibet Univ.30 (2), 65–70. doi: 10.16249/j.cnki.54-1034/c.2015.02.011

104

Liu L. Cao S. Ji Y. Zhang X. Huang T. (2005). Qualitative and quantitative analysis of aristolochic acids in Chinese materia medica and traditional Chinese patent medicines. Chin. Traditional Patent Med.27 (8), 938–941. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-1528.2005.08.025

105

Liu Y. Han S. Feng Q. Wang J. (2011). Determination of aristolochic acids A and B in Chinese herbals and traditional Chinese patent medicines using ultra high performance liquid chromatography-triple quadrupole mass spectrometry. Chin. J. Chromatogr.29 (11), 1076–1081. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1123.2011.01076

106

Lord G. M. Cook T. Arlt V. M. Schmeiser H. H. Williams G. Pusey C. D. (2001). Urothelial malignant disease and Chinese herbal nephropathy. Lancet358 (9292), 1515–1516. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06576-X

107

Lord G. M. Hollstein M. Arlt V. M. Roufosse C. Pusey C. D. Cook T. et al . (2004). DNA adducts and p53 mutations in a patient with aristolochic acid-associated nephropathy. Am. J. Kidney Dis.43 (4), e11–17. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.11.024

108

Lord G. M. Tagore R. Cook T. Gower P. Pusey C. D. (1999). Nephropathy caused by Chinese herbs in the UK. Lancet354 (9177), 481–482. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)03380-2

109

Lukin M. Zaliznyak T. Johnson F. de los Santos C. (2012). Structure and stability of DNA containing an aristolactam II-dA lesion: implications for the NER recognition of bulky adducts. Nucleic Acids Res.40 (6), 2759–2770. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1094

110

Luo Q. (2013). Determination of aristolochic acid A in Ershiwuweishanhu Pill by HPLC. Drug Clinic10 (14), 37–39. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-2809.2013.14.010

111

Lv Q. (2015). Limit test of aristolochic acid A in Zhuifengtougu Capsules. Chin. J. Modern Drug Appl.9 (15), 285–286. doi: 10.14164/j.cnki.cn11-5581/r.2015.15.196

112

Lv Y. Que Y. Su Q. Li Q. Chen X. Lu H. (2016). Bioinformatics facilitating the use of microarrays to delineate potential miRNA biomarkers in aristolochic acid nephropathy. Oncotarget7 (32), 52270–52280. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10586

113

Mao W. W. Gao W. Liang Z. T. Li P. Zhao Z. Z. Li H. J. (2017). Characterization and quantitation of aristolochic acid analogs in different parts of Aristolochiae Fructus, using UHPLCQ/TOF-MS and UHPLC-QQQ-MS. Chin. J. Nat. Med.15 (5), 0392–0400. doi: 10.1016/S1875-5364(17)30060-2

114

Martinek V. Barta F. Hodek P. Frei E. Schmeiser H. H. Arlt V. M. et al . (2017). Comparison of the oxidation of carcinogenic aristolochic acid I and II by microsomal cytochromes P450 in vitro: experimental and theoretical approaches. Monatsh. Chem.148 (11), 1971–1981. doi: 10.1007/s00706-017-2014-9

115

Martinek V. Kubickova B. Arlt V. M. Frei E. Schmeiser H. H. Hudecek J. et al . (2011). Comparison of activation of aristolochic acid I and II with NADPH:quinone oxidoreductase, sulphotransferases and N-acetyltranferases. Neuro. Endocrinol. Lett.32 (Suppl 1), 57–70. doi: 10.3233/VES-2011-0426

116

Meinl W. Pabel U. Osterloh-Quiroz M. Hengstler J. G. Glatt H. (2006). Human sulphotransferases are involved in the activation of aristolochic acids and are expressed in renal target tissue. Int. J. Cancer118 (5), 1090–1097. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21480

117

Mengs U. (1982). The carcinogenic action of aristolochic acid in rats. Arch. Toxicol.51, 107–119. doi: 10.1007/BF00302751

118

Mengs U. (1987). Acute toxicity of aristolochic acid in rodents. Arch. Toxicol.59 (5), 328–331. doi: 10.1007/BF00295084

119

Mengs U. (1988). Tumour induction in mice following exposure to aristolochic acid. Arch. Toxicol.61 (6), 504–505. doi: 10.1007/BF00293699

120

Mengs U. Stotzem C. D. (1993). Renal toxicity of aristolochic acid in rats as an example of nephrotoxicity testing in routine toxicology. Arch. Toxicol.67 (5), 307–311. doi: 10.1007/BF01973700

121

Meyer M. M. Chen T. P. Bennett W. M. (2000). Chinese herb nephropathy. Proc. (Bayl Univ Med Cent).13 (4), 334–337. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2000.11927699

122

Michl J. Bello O. Kite G. C. Simmonds M. S. J. Heinrich M. (2017). Medicinally used Asarum species: high-resolution LC-MS analysis of aristolochic acid analogs and in vitro toxicity screening in HK-2 cells. Front. Pharmacol.8, 215. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00215

123

Michl J. Ingrouille M. J. Simmonds M. S. Heinrich M. (2014). Naturally occurring aristolochic acid analogues and their toxicities. Nat. Prod. Rep.31 (5), 676–693. doi: 10.1039/c3np70114j

124

Michl J. Jennings H. M. Kite G. C. Ingrouile M. J. Simmonds M. S. Heinrich M. (2013). Is aristolochic acid nephropathy a widespread problem in developing countries? A case study of Aristolochia indica L. J. Ethnopharmacol.149 (1), 235–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.06.028

125

Michl J. Kite G. C. Wanke S. Zierau O. Vollmer G. Neinhuis C. et al . (2016). LC-MS- and 1H NMR-based metabolomic analysis and in vitro toxicological assessment of 43 Aristolochia species. J. Nat. Prod.79 (1), 30–37. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b00556

126

Milichovsky J. Barta F. Schmeiser H. H. Arlt V. M. Frei E. Stiborova M. et al . (2016). Active site mutations as a suitable tool contributing to explain a mechanism of aristolochic acid I nitroreduction by cytochromes P450 1A1, 1A2 and 1B1. Int. J. Mol. Sci.17 (2), 213. doi: 10.3390/ijms17020213

127

Miyazaki J. Nishiyama H. (2017). Epidemiology of urothelial carcinoma. Int. J. Urol.24 (10), 730–734. doi: 10.1111/iju.13376

128

Mohamed O. A. Wang Z. Yu G. Khalid H. E. (1999). Determination of aristolochic acid A in the roots and rhizomes of Aristolochia from Sudan and China by HPLC. J. China Pharm. Univ.30 (4), 288–290. doi: 10.1016/B978-008043005-8/50012-3

129

Moriya M. Slade N. Brdar B. Medverec Z. Tomic K. Jelakovic B. et al . (2011). TP53 mutational signature for aristolochic acid: an environmental carcinogen. Int. J. Cancer129 (6), 1532–1536. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26077

130