Abstract

Background:

The prevalence of dementia is expected to rapidly increase in the next decades, warranting innovative solutions improving diagnostics, monitoring and resource utilization to facilitate smart housing and living in the nursing home. This systematic review presents a synthesis of research on sensing technology to assess behavioral and psychological symptoms and to monitor treatment response in people with dementia.

Methods:

The literature search included medical peer-reviewed English language publications indexed in Embase, Medline, Cochrane library and Web of Sciences, published up to the 5th of April 2019. Keywords included MESH terms and phrases synonymous with “dementia”, “sensor”, “patient”, “monitoring”, “behavior”, and “therapy”. Studies applying both cross sectional and prospective designs, either as randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, and case-control studies were included. The study was registered in PROSPERO 3rd of May 2019.

Results:

A total of 1,337 potential publications were identified in the search, of which 34 were included in this review after the systematic exclusion process. Studies were classified according to the type of technology used, as (1) wearable sensors, (2) non-wearable motion sensor technologies, and (3) assistive technologies/smart home technologies. Half of the studies investigated how temporarily dense data on motion can be utilized as a proxy for behavior, indicating high validity of using motion data to monitor behavior such as sleep disturbances, agitation and wandering. Further, up to half of the studies represented proof of concept, acceptability and/or feasibility testing. Overall, the technology was regarded as non-intrusive and well accepted.

Conclusions:

Targeted clinical application of specific technologies is poised to revolutionize precision care in dementia as these technologies may be used both by patients and caregivers, and at a systems level to provide safe and effective care. To highlight awareness of legal regulations, data risk assessment, and patient and public involvement, we propose a necessary framework for sustainable ethical innovation in healthcare technology. The success of this field will depend on interdisciplinary cooperation and the advance in sustainable ethic innovation.

Systematic Review Registration:

PROSPERO, identifier CRD42019134313.

Introduction

The global health challenge of dementia is exceptional in size, cost and impact (Wortmann, 2012). The World Health Organization estimates that 47 million persons live with dementia worldwide, a number expected to reach 75 million by 2030 and more than triple by 2045 (World Health Organization, 2017). According to the Alzheimer’s Association, dementia-related costs range from $157 to $215 billion - higher than costs associated with cancer or cardiac disease — in the US alone, with roughly $42,000 to $56,000 spent per individual. These costs are driven to a significant extent by behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) such as psychosis, apathy, hyperactivity, agitation, sleep disorders or depression (Ballard and Howard, 2006). This symptomatology may be caused or exaggerated by a range of conditions, such as hypoglycemia, pain and general discomfort, or they may arise secondary to the use of both psychotropic and non-psychotropic medications, which are known to precipitate a wide range of symptoms (Lyketsos et al., 2006). The prevalence of polypharmacy further adds to this clinical challenge (Gulla et al., 2016). Compounding this, no FDA approved pharmacologic treatments for BPSD exist and a wide range of psychotropic medications — including antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, antidepressants, and cholinesterase inhibitors — are regularly used to manage the symptoms, despite clear guidelines as to when and how to use them (Ballard and Corbett, 2010). This has led to vast variance in clinical practice around pharmacologic management of BPSD (Livingston et al., 2017). Polypharmacy and inappropriate prescribing can lead to significant adverse events, including increased fall risk, higher rates of inpatient care, loss of independence, and it increase the need for monitoring, which can significantly raise costs of dementia care, especially in nursing homes (Winblad et al., 2016).

Thus, there is an urgent need for tools that facilitate diagnoses that are more precise and a deeper understanding of patterns and triggers for BPSD (Kang et al., 2010). This includes tools that generate continuous data on behavior patterns, which may facilitate earlier detection of temporal events and guide more precise pharmacotherapy. Finally, there is a need for tools that can more closely monitor treatment response in dementia across care settings (Teipel et al., 2018).

A wide array of new technologies may provide solutions, especially those explicitly designed to support people with dementia and their formal and informal caregivers (Yang and Kels, 2017). The evidence around this has also been growing with research highlighting aspects of active and passive technology used in dementia (Pillai and Bonner-Jackson, 2015; Martinez-Alcala et al., 2016; Giggins et al., 2017; Brims and Oliver, 2018), the impact of safety equipment on wandering in dementia (Lin et al., 2014; Mangini and Wick, 2017), ethical considerations of surveillance technology in dementia (Sorell and Draper, 2012), or the need for real-world evidence-based solutions to conduct clinical trials (Teipel et al., 2018).

In this review paper, we present a synopsis of existing research studies in this space, including work on both commercially available as well as prototype technologies. This includes diagnostic technologies that utilize active and passive sensing in connection with smart housing, voice recognition and motion mapping (Teipel et al., 2018), and prognostic approaches that may inform clinicians about a range of potential responses, including alterations in circadian rhythm, changes in gait speed, falls, and variations in spatial location and reduction in resistance to care.

Finally, we discuss the potential pitfalls of this technology, specifically related to issues around ethics, privacy and security of data (Bantry-White, 2018; Chalghoumi et al., 2019) and the scalability of these technologies in terms to social living and activities.

Methods

This systematic review presents a synthesis of previous research on sensing technology to assess behavioral and psychological symptoms and to monitor treatment response in people with dementia.

Literature Search

We initially searched for peer-reviewed English language publications indexed in the following databases: Embase, Medline, Cochrane library and Web of Sciences, published up to the 5thof April 2019. Keywords included MESH terms and phrases synonymous with “dementia”, “sensor”, “patient”, “monitoring”, “behavior”, “therapy”. See full search history in the supplementary material. We assessed papers for eligibility using the PICO criteria (P: population, I: intervention, C: comparison and O: outcome), (see Table 1). We included studies applying both cross-sectional and prospective designs, including randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, and case-control studies. Reviews, opinion papers, protocols, and conference abstracts were excluded from the main search results.

Table 1

| Inclusion criteria according to PICO | Population | People with dementia |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Use of sensor technology | |

| Comparison | No use of sensor technology | |

| Outcome | Changes in behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia/neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia. Validity of assessment of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia comparing sensor technology with proxy rated symptoms | |

| Exclusion criteria | Studies published before 2009. Reviews, protocols, opinion, and conference papers. Publications in other languages than English. |

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

After removal of duplicates, one researcher (BH) screened all the manuscripts on title and abstract level to select relevant studies based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Potentially relevant studies were assessed for eligibility by all coauthors by evaluating the inclusion and exclusion criteria on the full-text manuscripts. Reference lists of manuscripts and reviews were screened to identify additional relevant publications. The final selection of included publications was by consensus among all authors. The study was registered in PROSPERO 3rd of May 2019.

Results

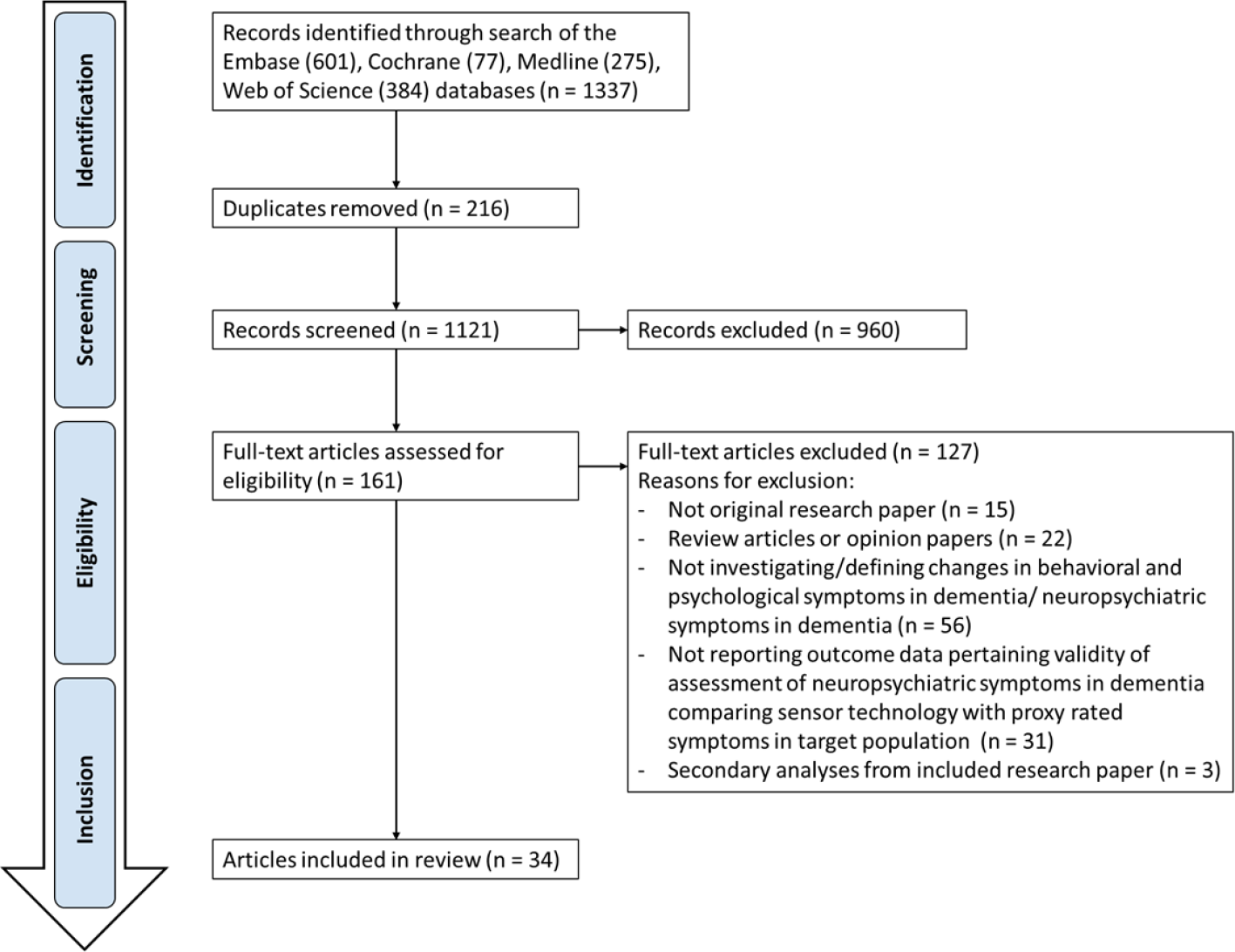

The systematic search generated 1,337 potential publications from Embase (601), Cochrane (77) Medline (275), and Web of Science (384), of which 161 papers were identified as relevant for full-text evaluation (Figure 1). Of these, 127 papers were removed from the following results because they were either editorial review pieces or opinion articles, or because the studies involved use of technology but not for the primary goal of managing BPSD. Eighteen (53%) articles were published in Europe, 10 (29%) in the United States and 6 (18%) in Oceania.

Figure 1

Flow Chart.

Of the 34 studies selected, 23 focused on management of BPSD itself, while 11 studies that utilized sophisticated technological approaches for studying other factors. For example, one study (Whelan et al., 2018) assessed communication between caregivers and nursing home staff, while another utilized technology to assess ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs) (Stucki et al., 2014). While these studies did not meet the original inclusion criteria, by consensus among the co-authors, we elected to include the studies since they reflect potentially meaningful applications of technology and may have implications for pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic management of BPSD.

For our final review, we assessed the full text from the 34 papers that were identified as relevant and divided studies into four broad categories, based on the type of technology used: (1) wearable technology, (2) non-wearable motion sensor technology, (3) assistive technology/smart home technology, and (4) other technologies not meeting criteria for the above three. We identified six papers that utilized more than one type of technology, and incorporated them into one of the above sections, based on the primary technology for each study.

Wearable Technologies

We identified seven studies that used wearable technologies — these included multiple sensor systems (two papers), ankle or wristbands (three papers), or a combination of both (two papers). We identified four prospective or retrospective cross-sectional studies along with two cohort studies and one case-control study. Study length ranged from 100 sec to 18 months. We noted that five studies utilized wearable technologies to primarily detect motion and two papers utilized wearable technologies that detected variables other than motion (body posture, stress). The details of the identified studies are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2

| Author Country | Year | Study design | N | Study length | Domains studied | Outcome measures | Type of technology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bankole et al., USA (Bankole et al., 2012) | 2012 | Cross-sectional | 6 | 6 weeks | Agitation in dementia | Construct validity of BSN, tested against CMAI, ABS, MMSE | BSN - readings from wearables on wrist, waist, and ankle |

| Fleiner et al., Germany, (Fleiner et al., 2016) | 2016 | Cross-sectional | 45 | 72 h | Agitation in dementia | Feasibility and acceptance of wearable uSense sensor | Wearable “uSense” 3D hybrid motion sensor on lower back which records body postures |

| Hsu et al. Taiwan, (Hsu et al., 2014) | 2014 | Cross-sectional | 71 | 1 visit | Dementia | Validity of wearable device in sensing gait and balance problems during walking tasks | Inertial sensor-based wearable |

| Kikhia et al. Sweden, (Kikhia et al., 2016) | 2016 | Case series | 6 | 37 days | Stress in dementia | Stress measurements (data was categorized into Sleeping, Aggression, Stress, and Normal) and GSR data | Wearable (“DemaWare@NH” wristband) - includes accelerometer, detects skin conductance and temperature, and environmental light and temperature |

| Merilahti et al. Finland, (Merilahti et al., 2016) | 2016 | Retrospective database study | 16 | 12–18 months | Sleep patterns and functional status | Actigraphy, ADLs | Wearable (wristband) |

| Zhou et al. USA, (Zhou et al., 2017) | 2017 | Cohort study | 30 | 1 visit | Motor-cognitive impairment | Feasibility of iTMT, performance on iTMT | iTMT |

| Zhou et al. USA, (Zhou et al., 2018) | 2018 | Cohort study | 44 | 1 visit | Cognitive frailty (cognitive impairment and frailty) | Gait, iTMT performance, accuracy of iTMT system in detecting motor planning errors | iTMT |

Studies utilizing wearable technologies.

ABS, Aggressive Behavior Scale; ADL, Activities of Daily Living; BSN, Body sensor network; CMAI, Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory; GSR, Galvanic Skin Response; iTMT, Instrumented trail-making task; MMSE, Mini-Mental-Scale Examination.

Non-Wearable Motion Sensor Technologies

We identified 12 studies that utilized sensor-based motion detection approaches other than wearables. Only one of these was a randomized controlled trial, with one cohort study, four cross-sectional studies, two proof of concept studies, two case studies, and one longitudinal study. The sample sizes of the studies ranged vastly — from 1 to 265. This broad range reflects the heterogeneity of applications of motion sensor technologies for dementia. Study length ranged from two weeks to three years. Likewise, in the case of wearable technologies, we identified vast heterogeneity in study indications and purpose. Identified studies are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3

| Author Country | Year | Study design | N | Study length | Domains Studied | Outcome measures | Type of technology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akl et al., Canada, (Akl et al., 2015) | 2015 | Feasibility Study | 97 | 3 years | Mild cognitive impairment | CDR), MMSE (tracking who remained cognitively intact vs. who experienced decline) | Passive infrared motion sensors, wireless contact switches (to track entrances/exits), and motion-activated sensors (to track walking speeds) installed in the home, machine learning algorithms |

| Alvarez et al. Spain (Alvarez et al., 2018) | 2018 | Cohort Study | 18 | 10 weeks | Freezing of gait & abnormal motion behavior | Accuracy of Measurements | Multisensory band (wearable - temp, HR, motion data), binary sensor (doors open/close), RGB-D camera (extraction of depth information), Zenith camera (360-degree pano camera for movement tracking), WSN anchors/beacons (monitor signals from pts' wearables) |

| Dodge et al. USA, (Dodge et al., 2015) | 2015 | longitudinal | 265 | 3 years | MCI | CDR; Neuropsychiatric scales (immediate & delayed recall; category fluency; trails, WAIS, Boston Naming Test) | Passive in-home sensor technology (specific motion sensors on the ceiling) |

| Enshaeifar et al. UK (Enshaeifar et al., 2018) | 2018 | Cross-sectional | 12 | 6 month | Dementia (agitation, irritation, and aggression) | Motion data and level of engagement in activities | Wireless sensors (passive infrared sensors, motion sensors, pressure sensor, central energy consumption monitoring device) |

| Galambos et al. USA (Galambos et al., 2013) | 2013 | Case Series | 5 | 7–12 months | Depression & Dementia in older adults | Congruence between health information (GDS, MMSE, SF-12) and activity level changes | Passive infrared motion sensors |

| Gochoo et al. USA (Gochoo et al., 2018) | 2018 | Cross-sectional | 1 | 21 months | Dementia | Accuracy of classifier model in correlating travel pattern with dementia detection | Passive Infrared sensors & deep convolutional neural network (DCNN) |

| Jansen et al. Germany, (Jansen et al., 2017) | 2017 | Cross-sectional | 65 | 2 consecutive days | motor & cognitive impairment in adults in 2 nursing homes (motion, gait, cognitive function) | MMSE, GDS, apathy evaluation scale, short falls efficacy scale international, movement tracking (time away from room, transits) | Wireless sensor network (nodes fixed to the walls that use radio signals) |

| Melander et al. Sweden (Melander et al., 2017) | 2017 | Feasibility & Observational | 9 | 2 weeks | Dementia, agitation | Correlational analysis | EDA Sensor |

| Melander et al. Sweden, (Melander et al., 2018) | 2018 | Case Series | 14 | 8 week study duration | Dementia, agitation | NPI-NH (Nursing home), Electro dermal activity (EDA) | EDA Sensor |

| Nishikata et al. Japan, (Nishikata et al., 2013) | 2013 | Cross-sectional | 40 | 21-191 days | Moderate to advanced AD; BPSD | Integrated Circuit tag monitoring system (antennas set up on the ceiling that receive signals when patients moved under them) | |

| Rowe et al. USA (Rowe et al., 2009) | 2019 | RCT | 106 | 12 months | Nighttime wandering in dementia | Feasibility of system; prevention of dangerous nighttime events | Nighttime monitoring system |

| Yamakawa et al. Japan (Yamakawa et al., 2012) | 2012 | Cross-sectional | 35 | 95 days | Nighttime wandering in dementia | Movement indicators (distance moved, number of hours with movement, etc.), agreement with nursing records; system data agreement with BPSD measured by NPI | Integrated circuit (IC) tag monitoring system - measures temporal and spatial movements |

Studies utilizing motion-sensing technologies.

BPSD, Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia; CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating scale; DCNN, Deep Convolutional Neural Network; EDA, Electro Dermal Activity; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; HR, Human Resources; IC, Integrated circuit; MMSE, Mini-Mental-State Examination; NPI, Neuropsychiatric Inventory; NPI-NH, Neuropsychiatric Inventory-Nursing Home version; SF-12, Short-Form Health Survey 12; WSN, Wireless Sensor Network.

Assistive/Smart Home Technologies

We identified 12 studies that utilized sensor rays placed in the living environment of study subjects. These were variously referred to as assistive or smart home technologies, since they required minimal active engagement by the patient or subject. The studies identified in this category included only one partial RCT — this study had 3 sites, but investigators were able to implement the RCT design at only one site. In addition, we identified three cross sectional/case-control studies, one cohort study, two case series and two open feasibility studies. We also identified three qualitative studies in this category. Study length ranged from 30 min interviews to 15 months and sample sizes ranged from four individuals to 65. Details of studies using these technologies are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4

| Author Country | Year | Study design | N | Study length | Domains studied | Outcome measures | Type of technology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aloulou et al. Singapore (Aloulou et al., 2013) | 2013 | Feasibility study | 10 | 14 months | Wandering, falls, difficulty with ADLs | Acceptability, qualitative feedback | Ambient Assistive Living technologies (motion sensors controlled by a software) |

| Asghar et al. UK, (Asghar et al., 2018) | 2018 | Cross-sectional (questionnaire based) | 327 | 2 months | Factors impacting use of assistive technology in people with mild dementia | Survey responses | AT included mobility supports, cognitive games, reminders or prompters, social applications, and leisure supports. |

| Collins ME. USA (Collins, 2018) | 2018 | qualitative study | 8 | 30–45 min interviews | Alzheimer’s & related dementia | AT with ADLs | AT included Wii, iPads, iPhones, computers, medication management systems, and alarms |

| Hattink et al. The Netherlands (Hattink et al., 2016) | 2016 | RCT at Germany site, pre-test/post-test design in Belgium and Netherlands | 74 | 8 months | In-home assistive technologies’ impact on autonomy, quality of life for both people with dementia and caregivers, sense of competence | Usefulness/user-friendliness, perceived autonomy (measured by the Mastery scale and WHOQOL), QoL (measured by QOL-AD and self-report for caregivers), caregiver competence (measured by SSCQ | Rosetta system |

| Jekel et al. Germany, (Jekel et al., 2016) | 2016 | Case-control study | 21 | 1 day | MCI | IADL tasks, feasibility questionnaire | Assistive smart home technology |

| Lazarou et al. Greece (Lazarou et al., 2016) | 2016 | Case series | 4 | 16 weeks | MCI/Dementia/Mild Depression | MMSE, MoCA, RBMT-delayed recall, NPI, Functional Rating Scale for Symptoms of Dementia, GDS, HDRS, Functional Cognitive Assessment Scale, Perceived Stress Scale, Beck Anxiety Scale, Trail B., Beck Depression Inventory, IADL, Rey-OCFT, Test of Everyday Attention., Map Search, Visual Elevator, Telephone Search | Smart home monitoring |

| Martin et al. Ireland (Martin et al., 2013) | 2013 | Cross-sectional | 8 | Varied, one patient stayed on 33 months through the lifespan of the project | Dementia | Self-report questionnaires | NOCTURNAL monitoring station |

| Meiland et al. The Netherlands (Meiland et al., 2014) | 2014 | Case series | 50 | 15 months | Dementia | CANE, GDS, user feedback questionnaire | Monitoring and assistive ICT technologies |

| Nijhof et al., The Netherlands, (Nijhof et al., 2013) | 2013 | mixed methods (qualitative, cost analysis) | 14 | 9 month | dementia; well-being | Feasibility, cost-saving, reduction of caregiver burden, increased independence and safety | AD life system |

| Olsson et al. Sweden, (Olsson et al., 2018) | 2018 | qualitative study (interviews about use of a technology) | 8 | Interview follow-up after 12 week intervention study | memory impairment due to stroke | Sensor and feedback technology | |

| Sacco et al. France (Sacco et al., 2012), | 2012 | Cohort Study (prospective observational Study) | 64 | 1 day | AD and MCI | DAS | Smart home |

| Stucki et al. Switzerland (Stucki et al., 2014) | 2014 | Feasibility | 11 | 20 days | Focus group healthy, explorative group AD | ADL | Monitoring system |

Studies utilizing assistive technologies.

AD, Alzheimer`s Disease; ADL, Activities of Daily Living; AT, Assistive technology; CANE, Camberwill Assessment of Needs for the Elderly; DAS, Daily Activity Scenario; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; HDRS, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; IADL, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; MCI, Mild Cognitive Impairment; MMSE, Mini-Mental-State Examination; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; NPI, Neuropsychiatric Inventory; RBMT, Rivermead Behavioral Memory Test; SSCO, Short Sense of Competence questionnaire; WHOQOL, World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment instrument; QoL, Quality of Life; QoL-AD, Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease; Wii, Wii Game Console.

Other Technologies;

In addition, we identified three studies, each of which deployed a unique technological approach that could not be classified into one of the three categories above. One feasibility study (Khosla et al., 2017) used a human-like robot to assess social and emotional responses to nonhuman caregivers. Another study utilized a suite of apps administered via a tablet device as a nonpharmacologic intervention for agitation in dementia (Vahia et al., 2017). We identified one study that utilized a text analysis tool to detect variance and patterns of communication between patients, staff, and caregivers (Whelan et al., 2018). The details of the studies are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5

| Author Country | Year | Study design | N | Study length | Domains studied | Outcome measures | Type of technology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khosla et al. Australia, (Khosla et al., 2017) | 2016 | Longitudinal | 115 | 3 years | Social engagement in dementia | Emotional engagement, Visual engagement, Behavioral engagement, Verbal engagement, Robot acceptability questionnaire, Anxiety questionnaire | Social human robot named “Matilda” |

| Vahia et al. USA, (Vahia et al., 2017) | 2016 | Feasibility | 36 | Duration of hospitalization | Agitation in dementia | Acceptability, staff report of agitation severity | iPads with 70 installed applications |

| Whelan et al. Australia (Whelan et al., 2018) | 2017 | Cross-sectional | 34 | 10-min conversations | Communication difficulties between people with dementia and caregivers (e.g., topic shifts, interference, non-specificity, etc.) | Validity of Discursis software in detecting different types of “trouble-indicating behaviors” when checked against human coding | Discursis software (automated text-analytic tool which quantifies communication behavior |

Studies utilizing other technologies.

Finally, during the entire review process, we became increasingly aware of the discrepancies and lack of consensus of the terminology used in this field. An overview of terminology and content are presented in Table 6.

Table 6

| Terms | Devices | Tasks |

|---|---|---|

| Noninvasive body sensor network technology | Wearables on wrist, waist, and ankle e.g. accelerometer | Detect skin constitution; skin temperature; activities; environmental light and temperature |

| 3D Hybrid motion sensors of body postures | Uni- and multi-axial accelerometers | Body posture |

| Unobtrusive sensing technologies with signal processing of real-world data (or monitoring system (TIHM) using Internet of Things, IoT) | Passive, wireless infrared motion sensors, analyzed by machine learning algorithms | Tracks entrances/exits and walking speeds in the home Track motion; pressure; central energy consumption |

| Integrated Circuit tag monitoring system | Antennas set up on the ceiling and related to a software platform | Register signals when patients moved under them |

| Passive, web-based, non-intrusive, proxy-free, assistive technology (AT) | Wii (Nintendo); iPads; iPhones; computers; video cameras; medication management, and alarms | Support of mobility and leisure; cognitive games; social robots; reminders or prompters; social applications, detection/classification of ADL/IADL deficits |

| Sensor and feedback technology | Individually pre-recorded voice reminder | Memory support |

| Information and communication technology (ICT) | Imaging and video processing to improve assessments | Detect functional impairment and be more pragmatic, ecological and objective to improve prediction of future dementia |

| Tablet devices as novel non-pharmacologic tools | iPads | 70 installed applications support challenging patient behavior |

| Discourse analysis software | Automated text-analytic tool | Quantify communication behavior by discriminating between diverse types of trouble and repair signalling behavior |

Terminology and content of different devices.

Discussion

The goal for this review was to identify and summarize the extent to which literature on technologies (specifically sensors) have been used in the assessment and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. As these technologies become widely available, this role is likely to expand (Collier et al., 2018). We identified several ways in which these technologies are being studied. This body of literature will play a crucial role in helping researchers, clinicians and municipalities, and industry partners to develop precision approaches to dementia care. We did note, however, that even though we in our original search aimed at clinical intervention studies with control groups, the majority of the studies found are preliminary with relatively small sample sizes and small durations. Some studies with much larger sample sizes were not intervention studies; rather they represented large surveys of participants around technology use. This dearth in intervention studies suggests that the grounds for innovation, validation, and clinical transference of technology in the management of behavioral symptoms are fertile.

Though we classified technologies into three broad categories, we identified several common underlying themes. Firstly, almost half of studies across the three categories represent ways in which temporarily dense data on motion can be processed and aggregated as proxy for behavior. Findings from these studies indicate high validity of using motion data to detect and track behavioral symptoms such as sleep disturbances, agitation, and wandering (Rowe et al., 2009; Bankole et al., 2012; Sacco et al., 2012; Yamakawa et al., 2012; Aloulou et al., 2013; Galambos et al., 2013; Stucki et al., 2014; Fleiner et al., 2016; Hattink et al., 2016; Jekel et al., 2016; Lazarou et al., 2016; Merilahti et al., 2016; Alvarez et al., 2018; Enshaeifar et al., 2018). Continuous motion monitoring of people with dementia using sensor technology provides informal caregivers and health care providers with the ability to more immediately and accurately diagnose and manage behavioral disturbances and can help to delay admission to long-term care or inpatient facilities. In a prodromal population, data from 8 of the studies suggest that motion data can also be useful in early detection of mild cognitive impairment and/or mild Alzheimer`s disease (Sacco et al., 2012; Hsu et al., 2014; Akl et al., 2015; Dodge et al., 2015; Gochoo et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2018). While the majority of identified studies focused on the assessment of behaviors, we also identified 8 studies that developed intervention approaches based on sensor data or other feedback (Rowe et al., 2009; Aloulou et al., 2013; Martin et al., 2013; Hattink et al., 2016; Vahia et al., 2017; Khosla et al., 2017; Melander et al., 2018).

In addition, out of 34 studies, we found that 16 studies represented proof-of-concept, acceptability, and/or feasibility testing for technologies that are new and have not been used in the dementia population previously. These studies demonstrated some usability issues for smart home and assistive systems, e.g., technological malfunctions and general user-unfriendliness; however, the technology used was predominantly non-intrusive and well-accepted (Hattink et al., 2016; Olsson et al., 2018).

In terms of data privacy and security, we noted that the majority of our identified articles conclude their discussion by encouraging stakeholders to respect users’ privacy and autonomy. Several ask for legal frameworks and regulations to monitor the rapid development of this promising area (Yokokawa, 2012; Yang and Kels, 2017; Khan et al., 2018; Teipel et al., 2018). While we did not specifically identify clinical studies related to ethics, data privacy and security in our review, we present a synopsis of this topic, since the eventual acceptability of new technologies in dementia will be contingent on the development of transparency and trust around digital tools. This is highlighted in several opinion papers and review articles, which discuss ethical considerations in sensing technology for people with dementia or intellectual and developmental disabilities (Table 7).

Table 7

| Author | Year | Type of paper | Ethical considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bantry-White et al. Ireland (Bantry-White E, 2018) | 2018 | Scope review on ethics of electronic monitoring in PWD | a) Autonomy/liberty: Who decides the person`s interests? Identification of past and present wishes for ethical decision making; liberty by electronic monitoring; b) Privacy: Monitoring may be less intrusive than constant caregiver presence; c) Dignity: May technology be a stigma in context to a social construct? d) Monitoring formal and informal caregiving may restrict harmful behaviour. e) Beneficence/non-maleficence: Monitoring may reduce costs, but increasing isolation. |

| Chalghoumi et al. Canada (Chalghoumi H, et al., 2019) | 2019 | Focus group interviews with 6 people with I/DD | People show awareness of privacy concerns but not due to the use of technology. Privacy breaches are a major risk in I/DD: they do not understand the use of personal information and are vulnerable to biases in data collection. |

| Friedman et al. USA (Friedman and Rizzolo, 2017) | 2017 | National I/DD survey on electric video monitoring | Video monitoring are effective methods to expand community care while being cost effective. However, it should also aim at improving care, not only serve as a substitute for personal care and interaction. |

| Kang et al. USA (Kang et al., 2010) | 2010 | Opinion paper on in situ monitoring of older adults | Monitoring can replace caregiver-patient interaction and social contact but also the opposite in providing increased opportunities in contact with family members because of larger awareness of patients` needs. |

| Landau et al. Israel (Landau et al., 2010) | 2011 | Mixed method recommendations for policy makers on ethics on GPS use for PWD | a) Maintain balance between the needs of PWD for protection and safety and their need for autonomy and privacy; b) Decision for GPS use together with PWD (informed consent) and family; c) Advance directives or earlier wishes in case of lack of informed consent; d) Involvement of formal caregivers in decision making. |

| Mehrabian et al. Bulgaria (Mehrabian et al., 2014) | 2014 | Semi-structured interviews with PWD & caregivers | Participants are positive to home telecare, cognitive stimulation program and devices’ care of emergencies with potential to improve QoL. Ethical concerns (e.g. way of provision, installation, monitoring) are reported with needs for proper implementation and informed consent. |

| Robinson L et al. UK (Robinson et al., 2013) | 2013 | Scope review on practice & future direction | Summarize current use of assistive technology with focus on effectiveness, and potential benefits, and discuss the ethical issues associated with the use in elderly people including future directions. |

| Sorell et al., UK (Sorell and Draper, 2012) | 2012 | Position paper on telecare, surveillance and welfare state | Telecare may not be regarded as objectionable extension of a “surveillance state (Orwellian),” but a danger of deepening the isolation of those who use it. Telecare aims to reduce costs of public social and health care; correlative problem of isolation must be addressed alongside promoting independence. |

| Teipel et al. Germany (Teipel et al., 2018) | 2018 | Position paper on ICT devices and algorithms to monitor behavior in PWD | This paper discusses clinical, technological, ethical, regulatory, user-centred requirements for collecting continuously RWE data in RCTs. Data safety, quality, privacy and regulations need to be addressed by sensor technologies, which will provide access to user relevant outcomes and broader cohorts of participants than currently sampled in RCTs. |

| van Hoof et al. NL (van Hoof et al., 2018) | 2018 | Explorative study on RTLS in NHs | Interviews with formal caregivers; NH patients and family members, and researchers. Concerns differed between groups and addressed security, privacy of patients and carers, responsibility. |

| Wigg et al. USA (Wigg, 2010) | 2010 | Position paper on surveillance of pacing in PWD | Surveillance technologies such as locked doors dehumanise and frighten individuals, whereas motion detectors may increase QoL, health benefits and safe medication with less riskiness. |

| Yang et al. USA (Yang and Kels, 2017) | 2017 | Scope review on ethics of electronic monitoring for PWD | To protect and empower PWD, the decision-making capacity of the person has to be evaluated and a multidisciplinary process (including PWD, relatives and healthcare professionals) have to be conducted before electronic monitoring (GPS, radiofrequency, cellular triangulation) is used. |

Review and opinion articles on ethical considerations in sensing technology for people with dementia or intellectual and developmental disabilities.

ICT, Information and Communication Technology; I/DD, Intellectual and developmental disabilities; GPS, Global Positioning System; NH, Nursing Home; PWD, People with Dementia; QoL, Quality of Life; RCT, Randomized Controlled Trial; RTLS, Real Time Location Systems; RWE, Real World Evidence.

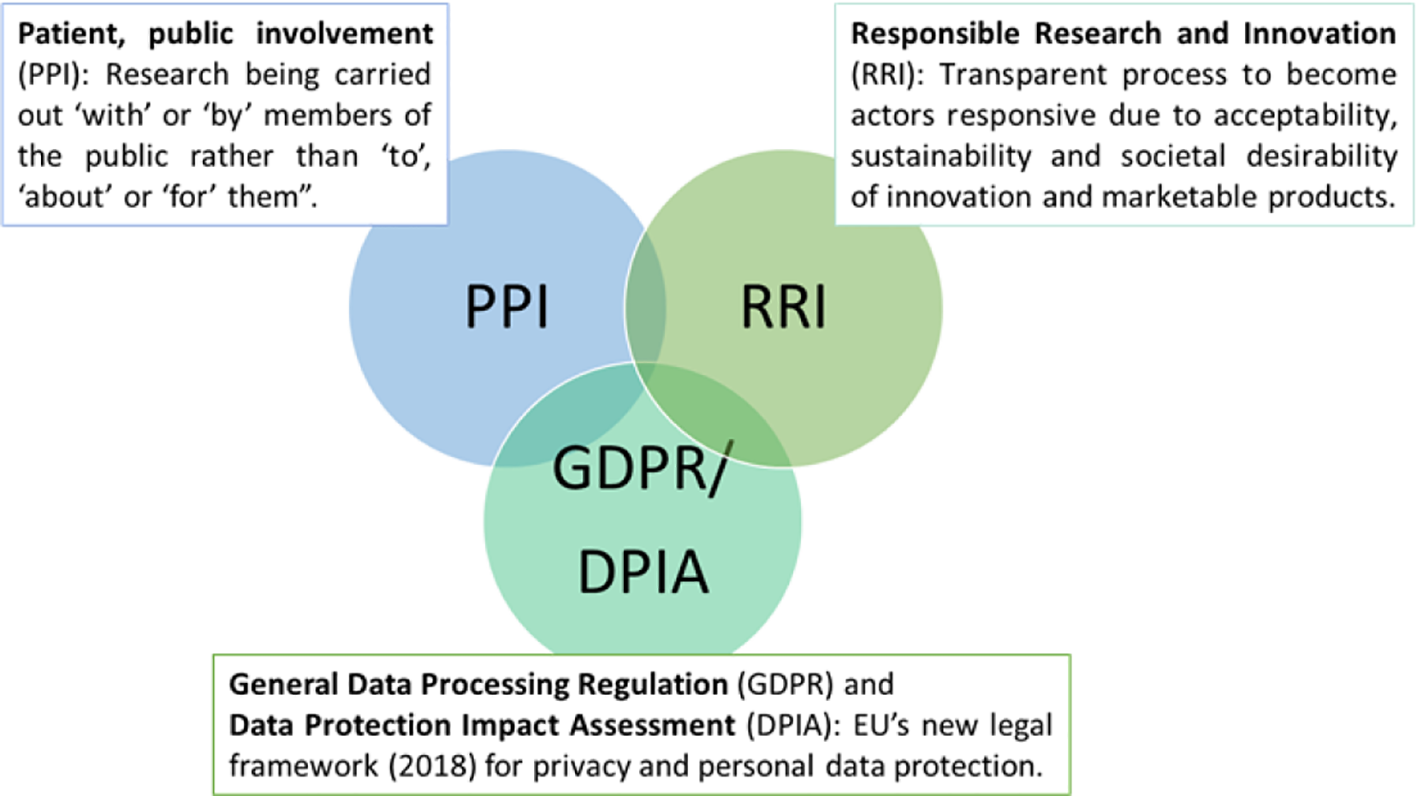

Launched in May 2018, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is the novel European Union-wide law on data protection — a significant step towards more responsible protection of individuals (Crutzen et al., 2019). While it is recognized that participation in research is based on affirmative, unambiguous, voluntary, informed, and specific consent (Mendelson, 2018), people with advanced dementia or intellectual and developmental disabilities are not able to give informed consent or understand the consequences of data acquisition (Friedman and Rizzolo, 2017; Chalghoumi et al., 2019; Timmers et al., 2019). Article 6 of the GDPR addresses this issue by including provisions that protecting persons with dementia and their relatives from being coerced into providing consent without awareness of how their data will be used (Cool, 2019; Crutzen et al., 2019). Despite this regulation, local legislation differs between European countries (de Lange et al., 2019). In Norway, for, e.g., a family member or legal advocate may provide or refuse consent based on their determination around whether the person with dementia would agree or decline to participate in a given study (Husebo et al., 2019). In Germany, the inclusion of people with dementia is limited for only those who may directly benefit from research results. To further strengthen privacy protections, Article 35 of the GDPR requires the Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) (Figure 2) (Donnelly and McDonagh, 2019), which mandates that only the most relevant personal data is collected (data minimization), and limits data access to those who are authorized or given permission by the individual (Yang and Kels, 2017). Overall, in this review, we did not specifically include search keywords relating to ethics in sensor technology but we recognized an engaged discussion in a considerable number of position papers and reviews around ethical considerations and especially, the need for data protection, proper transfer and storage (Holm and Ploug, 2013; Ploug and Holm, 2013).

Figure 2

Framework for sustainable ethic in healthcare technology.

Agencies that provide funding for research increasingly require patient and public involvement (PPI) in design, implementation, and dissemination of health research (Figure 2) (Melander et al., 2017; Melander et al., 2018). The goal of PPI is to ensure user-centered design so that persons who may benefit from it have an opportunity, especially in the early stages of their disease (Landau and Werner, 2012; Bantry-White, 2018) to understand the purpose of the technology (e.g. GPS) and to express values, wishes, and concerns to formal and informal caregivers, We noted that this principle was incorporated into at least three studies that we reviewed (Landau and Werner, 2012; Lariviere, 2017; Mangini and Wick, 2017; Bantry-White, 2018). This approach is also likely to optimize technology engagement in dementia (Nijhof et al., 2013; Mehrabian et al., 2014). A related principle, Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) (Figure 2), is defined as a transparent, interactive process by which societal actors and innovators become mutually responsive to each other (von Schomberg, 2013). They are encouraged to assume a critical perspective when evaluating the innovation and marketability of products (Holthe et al., 2018; Lehoux and Grimard, 2018). This approach may serve to promote awareness of technologies and related issues across both groups of stakeholders (van Haeften-van Dijk et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2017; Rostill et al., 2018).

Limitations

Our findings and recommendations must be interpreted in the context of some limitations. During the process, we recognized that the MESH terms and phrases synonymous with “dementia”, “sensor”, “patient”, “monitoring”, and “behavior”, and “ therapy” probably did not cover the whole range of interesting topics. For instance, items such as ethics, activities of daily living (ADL), and communication, may increase the understanding for and connection to the clinical aspects of this quickly developing area. Because of the vast heterogeneity of the literature, including terminology and definitions of sensing technology, a meta-analysis that may facilitate aggregated recommendations was not feasible. We also noted that the majority of the studies were open-label early-stage studies. Replication of these findings in larger trials will be required before these findings can become the standard of care. Our search algorithm also has potential limitations. We restricted our search to the past decade, since we anticipate that future sensor-based care models will be built on contemporary technology. We determined that tools that are more than a decade old are unlikely to have relevance in the future.

Conclusion

Overall, our systematic review demonstrates that sensor technologies have a broad range of potential applications in dementia care, ranging from early detection of cognitive impairment to aid in the management of behavioral and psychological symptoms in late stage dementia. Targeted clinical application of specific technologies is poised to revolutionize precision care in dementia as these technologies may be used by patients themselves, caregivers, or even applied at a systems level (e.g., nursing homes) to provide more safe and effective care. As sensor technology matures in its ability to guide care in BPSD, it may generate novel ways to capture early symptomatology (e.g., social isolation), improve specificity for cognitive testing in-situ and facilitate cost effective research approaches. A small but rapidly growing body of evidence around sensors in dementia care is paving the early way for the field, bringing into focus both the potential and pitfalls of this approach. Next step in this field may be to investigate the validity of use not only for care purposes, but also for prognostics as well as acceptability, feasibility, and responsiveness in clinical trials. The eventual success of this field will depend on inter-disciplinary models of research, development by industry partners, and sustainable ethic innovation in healthcare technology and smart housing.

Funding

This work is supported by the University of Bergen, The Norwegian Research Council and, in part, by the Technology and Aging Lab at McLean Hospital.

Statements

Data availability statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/supplementary material.

Author contributions

BH and IV developed the study idea, designed the study protocol for the systematic search and BH applied for funding. BH screened all the manuscripts on title and abstract level to select relevant studies. All the co-authors assessed potentially relevant studies on full-text manuscripts for eligibility using inclusion and exclusion criteria. HH, LB, PO, and AR drafted the first version of the result evaluation with supervision from IV and BH. Contribution to the subsequent drafts were provided by BH, HH, LB, PO, AR, and IV. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank medical librarian Regina Küfner Lein at the University of Bergen, Norway. BH would like to thank the Norwegian Government and the GC Rieber Foundation for supporting her time for this work at the Centre for Elderly and Nursing Home Medicine, University of Bergen. LB would like to thank the Research Council of Norway for the support during her postdoctoral period.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1

Akl A. Taati B. Mihailidis A. (2015). Autonomous unobtrusive detection of mild cognitive impairment in older adults. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng62 (5), 1383–1394. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2015.2389149

2

Aloulou H. Mokhtari M. Tiberghien T. Biswas J. Phua C. Kenneth Lin J. H. et al . (2013). Deployment of assistive living technology in a nursing home environment: methods and lessons learned. BMC Med. Info. Decis. Making13, 42. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-13-42

3

Alvarez F. Popa M. Solachidis V. Hernandez-Penaloza G. Belmonte-Hernandez A. Asteriadis S. et al . (2018). Behavior analysis through Multimodal Sensing for Care of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s Patients. IEEE Multimedia25 (1), 14–25. doi: 10.1109/MMUL.2018.011921232

4

Asghar I. Cang S. Yu H. (2018). Impact evaluation of assistive technology support for the people with dementia. Assist. Technol.31 (4), 180–192. doi: 10.1080/10400435.2017.1411405

5

Ballard C. Corbett A. (2010). Management of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in People with Dementia. CNS Drugs24 (9), 729–739. doi: 10.2165/11319240-000000000-00000

6

Ballard C. Howard R. (2006). Neuroleptic drugs in dementia: benefits and harm. Nat. Rev. Neurosci.7 (6), 492–500. doi: 10.1038/nrn1926

7

Bankole A. Anderson M. Smith-Jackson T. Knight A. Oh K. Brantley J. et al . (2012). Validation of noninvasive body sensor network technology in the detection of agitation in dementia. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Demen27 (5), 346–354. doi: 10.1177/1533317512452036

8

Bantry-White E. (2018). Supporting ethical use of electronic monitoring for people living with dementia: social work’s role in assessment, decision-making, and review. J. Gerontol. Soc Work61 (3), 261–279. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2018.1433738

9

Brims L. Oliver K. (2018). Effectiveness of assistive technology in improving the safety of people with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Ment. Health23 (8), 942–951. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2018.1455805

10

Chalghoumi H. Cobigo V. Dignard C. Gauthier-Beaupré A. Jutai J. W. Lachapelle Y. et al . (2019). Information Privacy for Technology Users With Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: Why Does It Matter? Ethics Behav.29 (3), 201–217. doi: 10.1080/10508422.2017.1393340

11

Collier S. Monette P. Hobbs K. Tabasky E. Forester B. P. Vahia I. V. (2018). Mapping movement: applying motion measurement technologies to the psychiatric care of older adults. Curr. Psychiatry Rep.20 (8), 64. doi: 10.1007/s11920-018-0921-z

12

Collins M. E. (2018). Occupational Therapists’ Experience with assistive technology in provision of service to clients with Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias. Phys. Occup. Ther. Geriatr.36 (2-3), 179–188. doi: 10.1080/02703181.2018.1458770

13

Cool A. (2019). Impossible, unknowable, accountable: dramas and dilemmas of data law. Soc Stud. Sci.49 (4), 503–530. doi: 10.1177/0306312719846557

14

Crutzen R. Ygram Peters G. J. Mondschein C. (2019). Why and how we should care about the General Data Protection Regulation. Psychol. Health34 (11), 1347–1357. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2019.1606222

15

de Lange D. W. Guidet B. Andersen F. H. Artigas A. Bertolini G. Moreno R. et al . (2019). Huge variation in obtaining ethical permission for a non-interventional observational study in Europe. BMC Med. Ethics20 (1), 39–39. doi: 10.1186/s12910-019-0373-y

16

Dodge H. H. Zhu J. Mattek N. C. Austin D. Kornfeld J. Kaye J. A. (2015). Use of high-frequency in-home monitoring data may reduce sample sizes needed in clinical trials. PloS One10 (9), e0138095. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138095

17

Donnelly M. McDonagh M. (2019). Health research, consent and the GDPR exemption. Eur. J. Health Law26 (2), 97–119. doi: 10.1163/15718093-12262427

18

Enshaeifar S. Zoha A. Markides A. Skillman S. Acton S. T. Elsaleh T. et al . (2018). Health management and pattern analysis of daily living activities of people with dementia using in-home sensors and machine learning techniques. PloS One13 (5), e0195605. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195605

19

Fleiner T. Haussermann P. Mellone S. Zijlstra W. (2016). Sensor-based assessment of mobility-related behavior in dementia: feasibility and relevance in a hospital context. Int. Psychogeriatr28 (10), 1687–1694. doi: 10.1017/S1041610216001034

20

Friedman C. Rizzolo M. C. (2017). Electronic video monitoring in medicaid home and community-based services waivers for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Dis.14 (4), 279–284. doi: 10.1111/jppi.12222

21

Galambos C. Skubic M. Wang S. Rantz M. (2013). Management of dementia and depression utilizing in- home passive sensor data. Gerontechnol11 (3), 457–468. doi: 10.4017/gt.2013.11.3.004.00

22

Giggins O. M. Clay I. Walsh L. (2017). Physical activity monitoring in patients with neurological disorders: A review of novel body-worn devices. Digit Biomarkers1 (1), 14–42. doi: 10.1159/000477384

23

Gochoo M. Tan T. H. Velusamy V. Liu S. H. Bayanduuren D. Huang S. C. (2018). Device-free non-privacy invasive classification of elderly travel patterns in a smart house using PIR Sensors and DCNN. IEEE Sensors J.18 (1), 390–400. doi: 10.1109/JSEN.2017.2771287

24

Gulla C. Selbaek G. Flo E. Kjome R. Kirkevold O. Husebo B. S. (2016). Multi-psychotropic drug prescription and the association to neuropsychiatric symptoms in three Norwegian nursing home cohorts between 2004 and 2011. BMC Geriatr.16, 115. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0287-1

25

Hattink B. J. Meiland F. J. Overmars-Marx T. de Boer M. Ebben P. W. van Blanken M. et al . (2016). The electronic, personalizable Rosetta system for dementia care: exploring the user-friendliness, usefulness and impact. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol.11 (1), 61–71. doi: 10.3109/17483107.2014.932022

26

Holm S. Ploug T. (2013). Nudgingand informed consent revisited: why “nudging” fails in the clinical context. Am. J. Bioeth13 (6), 29–31. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2013.781713

27

Holthe T. Casagrande F. D. Halvorsrud L. Lund A. (2018). The assisted living project: a process evaluation of implementation of sensor technology in community assisted living. A feasibility study. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol.15 (1), 29–36. doi: 10.1080/17483107.2018.1513572

28

Hsu Y. L. Chung P. C. Wang W. H. Pai M. C. Wang C. Y. Lin C. W. et al . (2014). Gait and balance analysis for patients with Alzheimer’s disease using an inertial-sensor-based wearable instrument. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform.18 (6), 1822–1830. doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2014.2325413

29

Husebo B. S. Ballard C. Aarsland D. Selbaek G. Slettebo D. D. Gulla C. et al . (2019). The effect of a multicomponent intervention on quality of life in residents of nursing homes: a randomized controlled trial (COSMOS). J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc.20 (3), 330–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2018.11.006

30

Jansen C. P. Diegelmann M. Schnabel E. L. Wahl H. W. Hauer K. (2017). Life-space and movement behavior in nursing home residents: results of a new sensor-based assessment and associated factors. BMC Geriatr.17, 36. doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0430-7

31

Jekel K. Damian M. Storf H. Hausner L. Frolich L. (2016). Development of a proxy-free objective assessment tool of instrumental activities of daily living in mild cognitive impairment using smart home technologies. J. Alzheimers. Dis.52 (2), 509–517. doi: 10.3233/JAD-151054

32

Kang H. G. Mahoney D. F. Hoenig H. Hirth V. A. Bonato P. Hajjar I. (2010). Innovative technology working group on advanced approaches to physiologic monitoring for the, A. (2010). In situ monitoring of health in older adults: technologies and issues. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc.58 (8), 1579–1586. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02959.x

33

Khan S. S. Ye B. Taati B. Mihailidis A. (2018). Detecting agitation and aggression in people with dementia using sensors-A systematic review. Alzheimers Dement14 (6), 824–832. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.004

34

Khosla R. Nguyen K. Chu M.-T. (2017). Human robot engagement and acceptability in residential aged care. Int. J. Human–Computer Interact.33 (6), 510–522. doi: 10.1080/10447318.2016.1275435

35

Kikhia B. Stavropoulos T. G. Andreadis S. Karvonen N. Kompatsiaris I. Savenstedt S. et al . (2016). Utilizing a wristband sensor to measure the stress level for people with dementia. Sensors16 (12), 24. doi: 10.3390/s16121989

36

Landau R. Auslander G. K. Werner S. Shoval N. Heinik J. (2010). Families’ and professional caregivers’ views of using advanced technology to track people with dementia. Qual. Health Res.20 (3), 409–419. doi: 10.1177/1049732309359171

37

Landau R. Werner S. (2012). Ethical aspects of using GPS for tracking people with dementia: recommendations for practice. Int. Psychogeriatr24 (3), 358–366. doi: 10.1017/S1041610211001888

38

Lariviere M. J. (2017). Exaine current technology – enabled care practices for people with dementia in the UK: findings from accommodate. A collaborative community-based ethnography of people wliving with dementia using assistive technology and telecare at home. Alzheimer Dement13 (7), P157. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.06.2595

39

Lazarou I. Karakostas A. Stavropoulos T. G. Tsompanidis T. Meditskos G. Kompatsiaris I. et al . (2016). A Novel and Intelligent Home Monitoring System for Care Support of Elders with Cognitive Impairment. J. Alzheimers Dis.54 (4), 1561–1591. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160348

40

Lehoux P. Grimard D. (2018). When robots care: Public deliberations on how technology and humans may support independent living for older adults. Soc Sci.Med.211, 330–337. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.06.038

41

Lin Q. Zhang D. Chen L. Ni H. Zhou X. (2014). Managing Elders’ Wandering Behavior Using Sensors-based Solutions: A Survey. Int. J. Gerontol8 (2), 49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ijge.2013.08.007

42

Livingston G. Sommerlad A. Orgeta V. Costafreda S. G. Huntley J. Ames D. et al . (2017). Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet390 (10113), 2673–2734. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6

43

Lyketsos C. G. Colenda C. C. Beck C. Blank K. Doraiswamy M. P. Kalunian D. A. et al . (2006). Position statement of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry regarding principles of care for patients with dementia resulting from Alzheimer disease. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry14 (7), 561–572. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000221334.65330.55

44

Mangini L. Wick J. Y. (2017). Wandering: Unearthing New Tracking Devices. Consult. Pharm.32 (6), 324–331. doi: 10.4140/TCP.n.2017.324

45

Martin S. Augusto J. C. McCullagh P. Carswell W. Zheng H. Wang H. et al . (2013). Participatory research to design a novel telehealth system to support the night-time needs of people with dementia: NOCTURNAL. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health10 (12), 6764–6782. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10126764

46

Martinez-Alcala C. I. Pliego-Pastrana P. Rosales-Lagarde A. Lopez-Noguerola J. S. Molina-Trinidad E. M. (2016). Information and Communication Technologies in the Care of the Elderly: Systematic Review of Applications Aimed at Patients With Dementia and Caregivers. JMIR Rehabil. Assist. Technol.3 (1), e6. doi: 10.2196/rehab.5226

47

Mehrabian S. Extra J. Wu Y.-H. Pino M. Traykov L. Rigaud A.-S. (2014). The perceptions of cognitively impaired patients and their caregivers of a home telecare system. Med. Devices8, 21–29. doi: 10.2147/MDER.S70520

48

Meiland F. J. Hattink B. J. Overmars-Marx T. de Boer M. E. Jedlitschka A. Ebben P. W. et al . (2014). Participation of end users in the design of assistive technology for people with mild to severe cognitive problems; the European Rosetta project. Int. Psychogeriatr.26 (5), 769–779. doi: 10.1017/S1041610214000088

49

Melander C. Martinsson J. Gustafsson S. (2017). Measuring Electrodermal Activity to Improve the Identification of Agitation in Individuals with Dementia. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Dis. Extra7 (3), 430–439. doi: 10.1159/000484890

50

Melander C. A. Kikhia B. Olsson M. Walivaara B. M. Savenstedt S. (2018). The Impact of Using Measurements of Electrodermal Activity in the Assessment of Problematic Behaviour in Dementia. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Dis. Extra8 (3), 333–347. doi: 10.1159/000493339

51

Mendelson D. (2018). The European Union General Data Protection Regulation (EU 2016/679) and the Australian My Health Record Scheme - A Comparative Study of Consent to Data Processing Provisions. J. Law Med.26 (1), 23–38. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3225047

52

Merilahti J. Viramo P. Korhonen I. (2016). Wearable Monitoring of Physical Functioning and Disability Changes, Circadian Rhythms and Sleep Patterns in Nursing Home Residents. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform.20 (3), 856–864. doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2015.2420680

53

Nijhof N. van Gemert-Pijnen L. J. Woolrych R. Sixsmith A. (2013). An evaluation of preventive sensor technology for dementia care. J. Telemed. Telecare19 (2), 95–100. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2012.120605

54

Nishikata S. Yamakawa M. Shigenobu K. Suto S. Makimoto K. (2013). Degree of ambulation and factors associated with the median distance moved per day in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Int. J. Nurs. Pract.19 Suppl 3, 56–63. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12174

55

Olsson A. Persson A. C. Bartfai A. Boman I. L. (2018). Sensor technology more than a support. Scand. J. Occup. Ther.25 (2), 79–87. doi: 10.1080/11038128.2017.1293155

56

Pillai J. A. Bonner-Jackson A. (2015). Review of information and communication technology devices for monitoring functional and cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials. J. Health Eng6 (1), 71–83. doi: 10.1260/2040-2295.6.1.71

57

Ploug T. Holm S. (2013). Informed consent and routinisation. J. Med. Ethics39 (4), 214. http://jme.bmj.com/content/39/4/214.abstract. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2012-101056

58

Robinson L. Gibson G. Kingston A. (2013). Assistive technologies in caring for the oldest old: A review of current practice and future directions. Aging Health9 (4), 365–375. doi: 10.2217/ahe.13.35

59

Rostill H. Nilforooshan R. Morgan A. Barnaghi P. Ream E. Chrysanthaki T. (2018). Technology integrated health management for dementia. Br. J. Community Nurs.23 (10), 502–508. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2018.23.10.502

60

Rowe M. A. Kelly A. Horne C. Lane S. Campbell J. Lehman B. et al . (2009). Reducing dangerous nighttime events in persons with dementia by using a nighttime monitoring system. Alzheimers Dement.5 (5), 419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2008.08.005

61

Sacco G. Joumier V. Darmon N. Dechamps A. Derreumaux A. Lee J. H. et al . (2012). Detection of activities of daily living impairment in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment using information and communication technology. Clin. Interv. Aging7, 539–549. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S36297

62

Sorell T. Draper H. (2012). Telecare, surveillance, and the welfare state. Am. J. Bioeth12 (9), 36–44. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2012.699137

63

Stucki R. A. Urwyler P. Rampa L. Muri R. Mosimann U. P. Nef T. (2014). A web-based non-intrusive ambient system to measure and classify activities of daily living. J. Med. Internet. Res.16 (7), e175. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3465

64

Teipel S. Konig A. Hoey J. Kaye J. Kruger F. Robillard J. M. et al . (2018). Use of nonintrusive sensor-based information and communication technology for real-world evidence for clinical trials in dementia. Alzheimers Dement.14 (9), 1216–1231. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.05.003

65

Timmers M. Van Veen E. B. Maas A. I. R. Kompanje E. J. O. (2019). Will the Eu Data Protection Regulation 2016/679 Inhibit Critical Care Research? Med. Law Rev.27 (1), 59–78. doi: 10.1093/medlaw/fwy023

66

Vahia I. V. Kamat R. Vang C. Posada C. Ross L. Oreck S. et al . (2017). Use of tablet devices in the management of agitation among inpatients with dementia: an open-label study. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry25 (8) 860–864. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2016.07.011

67

van Haeften-van Dijk A. M. Meiland F. J. van Mierlo L. D. Droes R. M. (2015). Transforming nursing home-based day care for people with dementia into socially integrated community day care: process analysis of the transition of six day care centres. Int. J. Nurs. Stud.52 (8), 1310–1322. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.04.009

68

van Hoof J. Verboor J. Weernink C. E. O. (2018). Real-Time Location Systems for Asset Management in Nursing Homes: An Explorative Study of Ethical Aspects. Information9 (4), 80. doi: 10.3390/info9040080

69

von Schomberg R. (2013). “A vision of responsible research and innovation,” in Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society. Eds. OwenR.BessantJ.HeintzM. (London: John Wiley & Sons), 51–74. doi: 10.1002/9781118551424.ch3

70

Whelan B. M. Angus D. Wiles J. Chenery H. J. Conway E. R. Copland D. A. et al . (2018). Toward the Development of SMART Communication Technology: Automating the Analysis of Communicative Trouble and Repair in Dementia. Innov. Aging2 (3), igy034. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igy034

71

Wigg J. M. (2010). Liberating the wanderers: using technology to unlock doors for those living with dementia. Sociol Health Illness32 (2), 288–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01221.x

72

Winblad B. Amouyel P. Andrieu S. Ballard C. Brayne C. Brodaty H. et al . (2016). Defeating Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias: a priority for European science and society. Lancet Neurol.15 (5), 455–532. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)00062-4

73

World Health Organization (2017). 10 facts on dementia. The World Health Organization. Available from: https://www.who.int/features/factfiles/dementia/en/

74

Wortmann M. (2012). Dementia: a global health priority - highlights from an ADI and World Health Organization report. Alzheimers Res. Ther.4 (5), 40. doi: 10.1186/alzrt143

75

Wu Y. T. Beiser A. S. Breteler M. M. B. Fratiglioni L. Helmer C. Hendrie H. C. et al . (2017). The changing prevalence and incidence of dementia over time - current evidence. Nat. Rev. Neurol.13 (6), 327–339. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.63

76

Yamakawa M. Suto S. Shigenobu K. Kunimoto K. Makimoto K. (2012). Comparing dementia patients’ nighttime objective movement indicators with staff observations. Psychogeriatr12 (1), 18–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-8301.2011.00380.x

77

Yang Y. T. Kels C. G. (2017). Ethical Considerations in Electronic Monitoring of the Cognitively Impaired. J. Am. Board. Fam. Med.30 (2), 258–263. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2017.02.160219

78

Yokokawa K. (2012). Usefulness of video for observing lifestyle impairments in dementia patients. Psychoger12 (2), 137–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-8301.2012.00428.x

79

Zhou H. Sabbagh M. Wyman R. Liebsack C. Kunik M. E. Najafi B. (2017). Instrumented trail-making task to differentiate persons with no cognitive impairment, amnestic mild cognitive impairment, and alzheimer disease: a proof of concept study. Gerontol63 (2), 189–200. doi: 10.1159/000452309

80

Zhou H. Lee H. Lee J. Schwenk M. Najafi B. (2018). Motor Planning Error: Toward Measuring Cognitive Frailty in Older Adults Using Wearables. Sensors18 (3), 20. doi: 10.3390/s18030926

Summary

Keywords

dementia, sensoring, monitoring, behavior, therapy

Citation

Husebo BS, Heintz HL, Berge LI, Owoyemi P, Rahman AT and Vahia IV (2020) Sensing Technology to Monitor Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms and to Assess Treatment Response in People With Dementia. A Systematic Review. Front. Pharmacol. 10:1699. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01699

Received

02 July 2019

Accepted

31 December 2019

Published

04 February 2020

Volume

10 - 2019

Edited by

Bjorn Johansson, Karolinska Institutet (KI), Sweden

Reviewed by

Dione Kobayashi, Independent Researcher, Cambridge, United States; Ming-Chyi Pai, National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan

Updates

Copyright

© 2020 Husebo, Heintz, Berge, Owoyemi, Rahman and Vahia.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bettina S. Husebo, Bettina.Husebo@uib.no

This article was submitted to Neuropharmacology, a section of the journal Frontiers in Pharmacology

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.