Abstract

Snowdrop is an iconic early spring flowering plant of the genus Galanthus (Amaryllidaceae). Galanthus species (Galanthus spp.) are economically important plants as ornaments. Galanthus spp has gained significance scientific and commercial interest due to the discovery of Galanthamine as symptomatic treatment drug for Alzhiermer disease. This review aims to discuss the bioactivities of Galanthus spp including anticholinesterase, antimicrobial, antioxidant and anticancer potential of the extracts and chemical constituents of Galanthus spp. This review highlights that Galanthus spp. as the exciting sources for drug discovery and nutraceutical development.

Introduction

Amaryllidaceae family comprises about 85 genera and classified into 1,100 perennial bulb species (Bulduk and Karafakıoğlu, 2019). The genus Galanthus, commonly known as “snowdrop” belongs to the family of Amaryllidaceae. It is a small genus comprises about 20 species of bulbous perennial herbaceous plants, and a small number of subspecies, varieties and natural hybrids (Rønsted et al., 2013; World Checklist of Selected Plant Families, 2020). Galanthus in Greek means “gala” for milk and “anthos” for flower, literally milk-white flowers (Lee, 1999). Native to Europe, their distribution also spread to Asia Minor (southwest Asia) and the Near East, including the eastern parts of Turkey, the Caucasus Mountain and Iran (Figure 1) (Semerdjieva et al., 2019).

FIGURE 1

Worldwide’s distribution of the Galanthus spp. throughout the United Kingdom and Spain (non-native), Europe (Romania, Bulgaria, etc..) and Southwest Asia (Turkey, Ukraine, Iran).

Snowdrop are economically important thanks to their ornamental potential and their use as landscape plants (Semerdjieva et al., 2019). Despite their ornamental properties, snowdrops have been used in folk medicine to treat pain, migraine and headache. It contains a variety of secondary metabolites such as flavonoids, phenolics, terpenoids and some important alkaloids that have shown to possess a broad spectrum of biological activities (Semerdjieva et al., 2019). Over the past three decades, many alkaloids isolated from the Galanthus spp. including isoquinoline-like compounds such as caranine, narciclasine, tazettine, narwedine and montanine were reported to exhibit acetylcholinesterase inhibitory potential, antibacterial, antifungal, antiparasitic (malaria), antiviral, antioxidant, anticancer, anti-inflammatory activities. (Elgorashi et al., 2003; Orhan and Şener, 2003; Ločárek et al., 2015; Resetár et al., 2017). The main constituents with pharmacological action present in the snowdrop, especially in the bulbs are galanthamine and lycorine (Ayaz et al., 2019). Galanthamine, an alkaloid of Galanthus woronowii Losinsk was reported by Proskurnina and Areshknina in 1947, (Proskurnina and Areshknina, 1953). Also, from the same family, galanthamine was purified and characterized from the bulbs of the G. nivalis L. by Dimatar PaskovGalanthamine has been used as the promising drug (known as Nivalin) for the symptometric treatment Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Paskov, 1959; Ayaz et al., 2019). In addition, lectins agglutinin (GNA) were discovered from Galanthus nivalis.

In this review, we discuss the traditional uses and report all published data in relation to their secondary metabolites and biological activities of snowdrops.

The Snowdrop Plants (Galanthus spp.)

Snowdrops are tiny plants (3 to 6 inches tall) with (1 inch or less) white flowers. Each snowdrop bulb produces two linear narrow grassy leaves and a single flower with a delicate small white drooping bell shaped flower. The snowdrop has no petal, but tepal. The outer three are longer pure white, while the smaller inner three are shorter and blushed with green markings (Aschan and Pfanz, 2006). There are many different varieties and species of snowdrop flowers that differs in terms of the size of the tepals and the green markings. As the name suggests, snowdrops are winter-to-spring flowering plants, of which Galanthus nivalis is the first and most common species of the genus (Figure 2; Table 1) to bloom during the end of the winter taking advantage of the lack of tree canopy to capture sunlight for photosynthesis and growth (Orhan and Şener, 2003). Wild snowdrops grow in damp soil in the temperate deciduous woodlands, for example oak (Quercus spp.), maple (Acer spp.), pines (Pinus spp.), cedar of Lebanon (Cedrus libani), particularly nearby shady areas, near river or streams (Elgorashi et al., 2003). Galanthus spp. are difficult to distinguish and classify due to high variability of morphological characteristics which is not clearly definable, which led to multiple taxonomic revisions Galanthus over the years (Rønsted et al., 2013). Currently, all species of Galanthus are classified as Critically Endangered (CR) under International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List Categories and Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade (CITES) in the list of Wild Fauna and Flora. The endangered status of Galanthus is due to its susceptibility to climate change, plucking and forestry and unregulated Galanthus bulb trade (International Union for Conservation of Nature, 2018). It is noteworthy that under CITES regulations, only rural communities in many countries are allowed in limited wild harvest and trade of just three species (G. nivalis, G. elwesii, and G. woronowii) (Bishop et al., 2001).

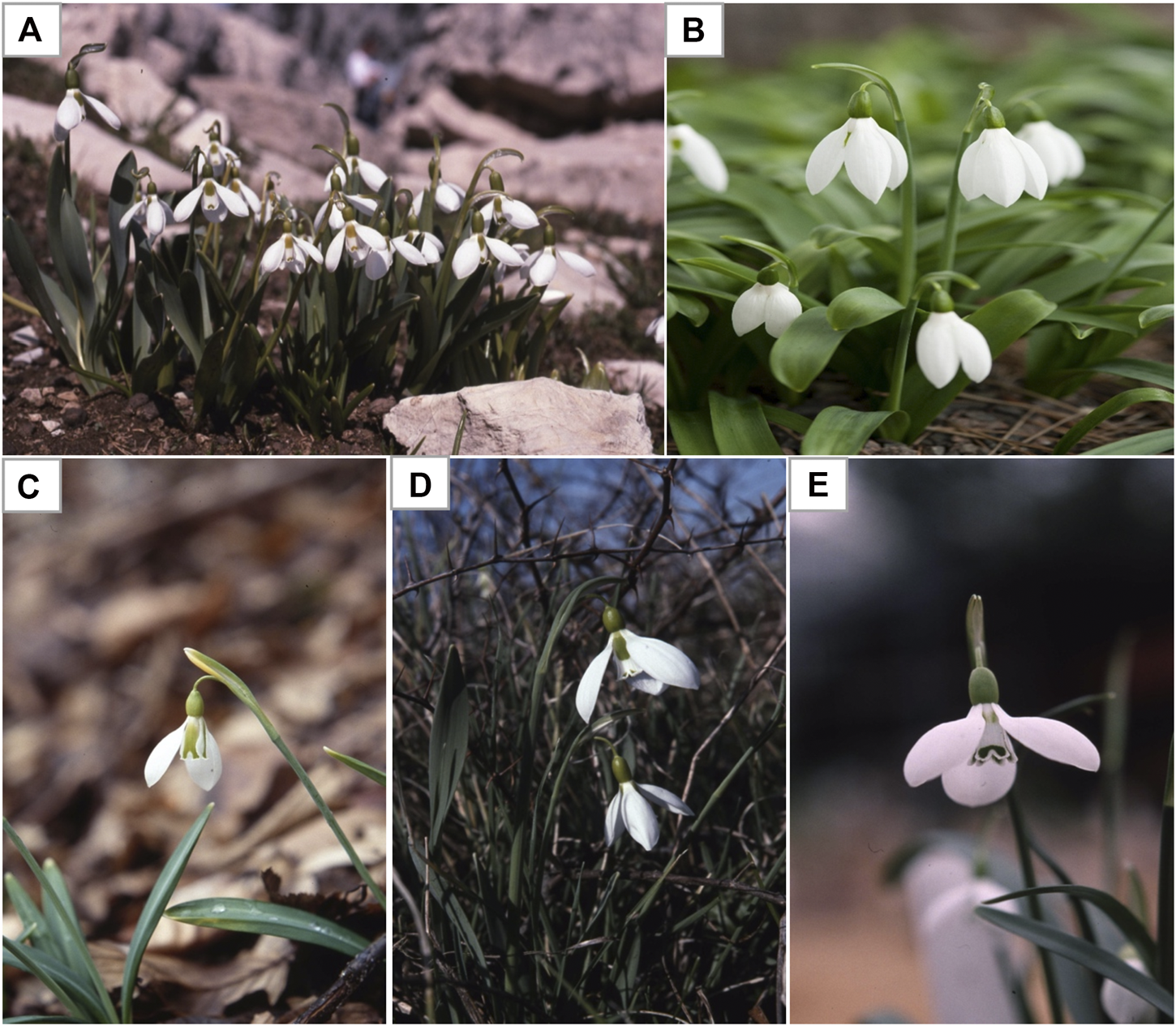

FIGURE 2

Examples of some commonly found Galanthus spp. (A)Galanthus nivalis(B)Galanthus elwesii (Giant or great snowdrops) (B)Galanthus gracilis(C)Galanthus ikariae(D)Galanthus trojanus. Adapted from Davis (2011).

TABLE 1

| Plant common name | Plant full scientific name Kew MPNS | Voucher specimen deposition |

|---|---|---|

| Common snowdrop | Galanthus nivalis L. | Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew |

| Giant or great snowdrop | Galanthus elwesii Hook.f. | Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew |

| Graceful or slender snowdrop | Galanthus gracilis Celak. | Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew |

| Ikaria snowdrop | Galanthus ikariae Baker. | Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew |

| Trojanus snowdrop | Galanthus trojanus A.P.Davis & Özhatay | Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew |

| Queen Olga’s snowdrop | Galanthus reginae-olgae Orph. | Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew |

| Subspecies of Queen Olga’s snowdrop | Galanthus reginae-olgae Orph. subsp. vernalis Kamari | — |

| Hybrids of G. nivalis and G. plicatus subsp. byzantinus | Galanthus xvalentinei nothosubsp. subplicatusa | — |

| Short snowdrop | Galanthus rizehensis Stern | Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew |

| Snowdrop Cilician | Galanthus cilicicus Baker. | Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew |

| Gol-e-Barfi | Galanthus transcaucasicus Fomin | — |

| Pleated snowdrop | Galanthus plicatus M.Bieb. | Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew |

| Subspecies of Pleated snowdrop | Galanthus plicatus subsp. byzantinus (Baker) D.A.Webb | Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew |

| Lagodekhsky snowdrop | Galanthus lagodechianus Kem-Nath. | — |

| Green snowdrop or Woronow’s snowdrop | Galanthus woronowii Losinsk. | Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew |

| Krasnov snowdrop | Galanthus krasnovii Khokhr. | Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew |

| ˗ | Galanthus alpinus Sosn. | — |

| Broad-leaved snowdrop | Galanthus platyphyllus Traub & Moldenke (previously known as G.latifolius) | — |

| Caucasian snowdrop | Galanthus caucasicus (Baker) Grossh. (now accepted as Galanthus alpinus var. alpinus) | Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew |

| Kemularia | Galanthus kemulariae Kuth. (now accepted as Galanthus lagodechianus Kem-Nath.) | — |

| Rare snowdrop | Galanthus shaoricus Kem-Natha | — |

| — | Galanthus peshmenii A.P.Davis & C.D.Brickell | — |

Galanthus spp.’s common names and scientific names.

Not found in http://powo.science.kew.org.

Snowdrop in Folklore

For centuries, the snowdrops have been used as a remedial herb to ease migraines and headaches. Plaitakis and Duvoisin believed the oldest record on snowdrop (Galanthus nivalis L.) was found in ancient Homer’s epic poem, where snowdrop is described as ‘moly’ and used by Odysseus as an antidote against Circe’s poisonous drugs (Plaitakis and Duvoisin, 1983). According to an unconfirmed report in the early 1950s, a Bulgarian pharmacologist noticed people of the remote areas rubbing their foreheads with the plant leaves and bulbs as a folk remedy to relieve nerve pain (Mashkovsky and Kruglikova–Lvova, 1951). Besides, some of the earlier publications had left traces that of evidences on the extensive use of snowdrop in Eastern Europe, such as Romania, Ukraine, the Balkan Peninsula, as well as in some Eastern Mediterranean countries (Heinrich, 2010). However, there were no relevant ethnobotanical literatures for confirmation to be located. Russian pharmacologists reported that local villagers at the foot of the Caucasian mountains in Georgia used the decoction of the bulbs of wild snowdrop (G. woronowii Los.) for the treatment of poliomyelitis in children (Sidjimova et al., 2003). Besides, an old glossary also classified snowdrop as cardiotonic, stomachic and emmenagogue (Baytop, 1999). The use of Galanthus herb has shown to increase the flow of menstrual blood to cure dysmennorhea or oligomennorhea, and was once used to induce an abortion if in the early stages of pregnancy (Baytop, 1999). Although snowdrops have a long traditional use in folk medicines, the chemical constituent recently become a commercial proposition (Ay et al., 2018). Snowdrops have attracted attention due to its pharmacological potential (wild snowdrops trade) and the chemical diversity (Sidjimova et al., 2003). It is interesting to note that, the bulb of the plant contains a chemical called phenanthridine alkaloid, which is toxic to animals including dogs and cats and may lead to gastrointestinal disorders in humans. Lycorine, the phenanthridine alkaloid is used in herbal medicines and pharmaceutical drugs over the years (Lamoral-Theys et al., 2009).

Biological Substances of Snowdrop and Their Ethnopharmacology

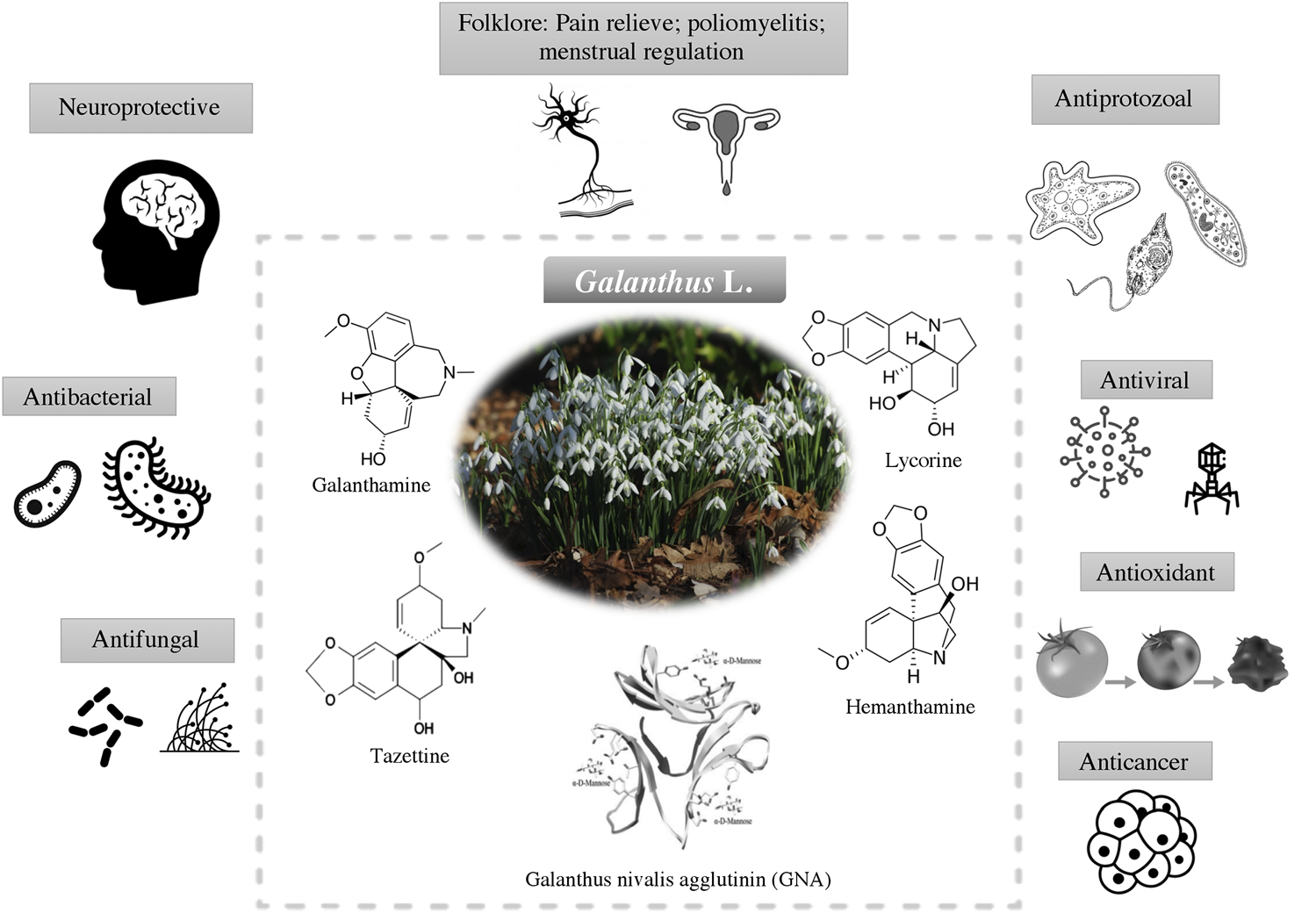

Having evolved over millions of years and wide application in traditional medicine. The discovery of new drug from snowdrops begin in the new decade. The discovery of galanthamine has attracted the interest from scientific community to further explore the relationships between the underexplored pharmacological properties of snowdrops and its chemical space. This including the antimicrobial, antioxidant and anticancer activities (Figure 3). The active compounds which are responsible for the biological activities are listed in Table 2.

FIGURE 3

Biological activities of Galanthus spp. and their main bioactive constituents (alkaloids and plant lectin) that contributed to these activities.

TABLE 2

| Biological activities | Species | Plant parts | Type of extract | Phenotypic activity | Effective dosea | Positive control | Possible mechanism of action | Compounds | Isolation/Detection methods | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cholinesterase | Galanthus nivalis L. | Bulb | Ethanol extract | AChE | 96% | — | Inhibit the cholinesterase enzyme from breaking down ACh, increasing both the level and duration of the neurotransmitter action. | — | — | Rhee et al. (2003) |

| Galanthus elwesii Hook.f. | Bulb | Chloroform: methanol (1:1) | AChE | 73.18% | Galanthamine | — | Orhan and Şener (2005) | |||

| AChE | 77.23% | |||||||||

| Galanthus ikariae Baker | Bulb | Chloroform: methanol (1:1) | AChE | Lycorine | Column chromatography and preparative TLC | |||||

| Chloroform: methanol extract lycorine | 75.56% | Tazettine | ||||||||

| Tazettine | 3.16 μM | Galanthamine | ||||||||

| crinine galanthamine | 3.20 μM | Crinine | ||||||||

| 3.20 μM | 3-epihydroxybulbispermine | |||||||||

| 3.20 μM | 2-demethoxymontanine | |||||||||

| 3.20 μM | ||||||||||

| Galanthus reginae-olgae Orph. subsp. vernalis Kamari | AChE | 76.96% | Conforti et al. (2010) | |||||||

| Alkaloid extract | ||||||||||

| Aerial | Methanol extract | AChE | ||||||||

| Methanol extract | 15.2 ± 0.81% | Physostigmine | 1-metil-4-etossi-,δ, (3)pirrolin-2-one, Neophytadiene, Exadecanoic acid, methyl ester, Exadecanoic acid, 9,12-Octadecandienoic acid, methyl ester,[E,E], 9,12,15-octadecantrienoic acid, methyl ester,[Z,Z,Z], 2-exadecen-1-ol-3,7,11,15-tetramethyl-[R-[R*,R*-(E)]], 9,12,15-octadecantrienal, 9,12-octadecandienoic acid [Z,Z]-2-idrossi-1-[idrossimethyl] ethylester, 2-monolinolenin, 1-octadecene, 9-α-fluoro-5-α-cholest-8(14)-ene-3,15-dione, Vitamin E, Ergost-5-en-3-ol, (3.β.,24 E), Stigmast-5-en-3-ol, (3.β.,24 S), Stigmast-5,24(38)-dien-3-ol, (3.β.,24 E) | GCMS | ||||||

| Hexane fraction | 1.2 ± 0.04% | — | Galanthamine, Lycorine, Tazettine | |||||||

| Ethyl acetate fraction | 1.2 ± 0.06% | |||||||||

| Dichloromethane fraction | 11.8 ± 0.72% | |||||||||

| Bulb | Methanol extract | AChE | Neophytadiene, Exadecanoic acid, Methyl ester, 9,12-Octadecandienoic acid, methyl ester,[E,E], 9,12,15-octadecantrienoic acid, methyl ester,[Z,Z,Z], 9,12-octadecandienoic acid [Z,Z]-2-idrossi-1-[idrossimethyl] ethylester Galanthamine, Lycorine, Tazettine, Crinine, Neronine | |||||||

| Methanol extract | 18.2 ± 0.93% | |||||||||

| Hexane fraction | 7.8 ± 0.49% | |||||||||

| Ethyl acetate fraction | 5.0 ± 0.42% | |||||||||

| Dichloromethane fraction | 38.5 ± 0.49% | |||||||||

| Galanthus gracilis Celak. | Bulb | Alkaloid fraction | AChE | IC50: 11.82 μg/ml | Galanthamine | 8-O-demethylhomolycorine, Homolycorine ,Galanthindole . Tazettine Lycorine, Galanthamine | GCMS | Bozkurt-Sarikaya et al. (2014) | ||

| Alkaloid fraction | ||||||||||

| Aerial | Alkaloid fraction | AChE | IC50: 25.5 μg/ml | Homolycorine, 8-O-demethylhomolycorine, Galanthindole, Tazettine | ||||||

| Alkaloid fraction | ||||||||||

| Galanthus xvalentinei nothosubsp. subplicatus | Bulb | Alkaloid fraction | AChE | IC50: 21.31 μg/ml | Lycorine ismine | Sarikaya et al. (2013) | ||||

| Alkaloid fraction | ||||||||||

| Aerial | Alkaloid fraction | AChE | IC50: 16.32 μg/ml | Tazettine, 11-O-(3'-Hydroxybutanoyl) hamayne, 3-O-(2''-Butenoyl)-11-O-(3'-hydroxybutanoyl) hamayne | ||||||

| Alkaloid fraction | ||||||||||

| Galanthus woronowii Losinsk | Aerial and Bulb | Alkaloid extract | AChE | Galanthamine (IC50: 0.15 μM) | Galanthine, Galanthamine, 2-O-(3’-hydroxybutanoyl)lycorine, Narwedine, 1-O-acetyl-9-O-methylpseudolycorine, O-methylleucotamine, Sternbergine, Lycorine, Sanguinine, Salsoline | Column Chromatography | Bozkurt et al. (2013a) | |||

| Galanthine Narwedine | IC50: 7.75 μM | |||||||||

| O-methylleucotamine | IC50: 11.79 μM | |||||||||

| Sternbergine Sanguinine | IC50: 16.42 μM | |||||||||

| 1-O-acetyl-9-O-methylpseudolycorine | IC50: 0.99 μM | |||||||||

| IC50: 0.007 μM | ||||||||||

| IC50: 78.7 μM | ||||||||||

| Galanthus rizehensis Stern | Bulb | — | AChE | IC50: 12.94 μg/ml | Lycorine, Tazettine, | GCMS | Bozkurt et al. (2013b) | |||

| Galanthamine | ||||||||||

| Galanthus cilicicus Baker | Bulb | Alkaloid fraction | AChE | IC50: 0.407 μg/ml | Galanthamine AChE IC50: 0.043) μg/ml; BuChE 0.711 μg/ML | Galanthamine, Tazettine, | GCMS | Kaya et al. (2017) | ||

| Alkaloid fraction | Galanthindole | |||||||||

| BuCHE | IC50: 8.14 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Alkaloid fraction | ||||||||||

| Aerial | Alkaloid fraction | AChE | IC50: 0.154 μg/ml | Haemanthamine, Tazettine, Galanthindole | ||||||

| Alkaloid fraction | ||||||||||

| BuCHE | IC50: 82.18 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Alkaloid fraction | ||||||||||

| Galanthus elwesii Hook.f. | Aerial (Location: Karaburun, Izmir) | Alkaloid fraction | AChE | IC50: 0.72 μg/mL μg/ml | Galanthamine (AChE IC50: 0.04) μg/ML, BuCHE IC50: 0.711 | Hordenine, Anhydrolycorine, Galanthamine, O-methylleucotamine Sanguinine, 11,12-Didehydroanhydrolycorine, Incartine, Oxoincartine | GCMS | Bozkurt et al. (2017) | ||

| Alkaloid fraction | ||||||||||

| BuCHE | IC50:6.56 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Alkaloid fraction | ||||||||||

| Bulb (Location: Karaburun, Izmir) | Alkaloid fraction | AChE | IC50: 2.20 μg/ml | Galanthamine (IC50: 0.04) μg/ml | Hordenine, Anhydrolycorine, Lycorine, Galanthamine, O-methylleucotamine, Sanguinine, Incartine, Oxoincartine | |||||

| Alkaloid fraction | ||||||||||

| BuCHE | IC50: 15.84 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Alkaloid fraction | ||||||||||

| Aerial (Location: Akseki, Antalya) | Alkaloid fraction | AChE | IC50: | Galanthamine (IC50: 0.04) μg/ml | Galanthindole, Haemanthamine 6-O-methylpretazettine, Galanthindole, 1-acetyl-Β-Carboline, Pinoresinol | |||||

| Alkaloid fraction | 15.72 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Bulb (Location: Akseki, Antalya) | Alkaloid fraction | AChE | IC50: 10.52 μg/ml | Galanthamine (IC50: 0.711) μg/ml | Galanthindole, Haemanthamine 6-O-methylpretazettine, Galanthindole, 1-acetyl-Β-Carboline, Pinoresinol | |||||

| Alkaloid fraction | ||||||||||

| Aerial (Location: Demirci, Manisa) | Alkaloid fraction | AChE | IC50: 6.25 μg/ml | Galanthamine (IC50: 0.04) μg/ml | Galanthamine, Sanguinine, Demethylhomolycorine, O-methylleucotamine, Lycorine, Anhydrolycorine, Hordenine, Ismine,, 2,11-didehydro-2-dehydroxylycorine, Assoanin, 11,12-didehydroanhydrolycorine, Hippeastrine | |||||

| Alkaloid fraction | ||||||||||

| BuCHE | IC50: 9.52 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Alkaloid fraction | ||||||||||

| Bulb (Location: Demirci, Manisa) | Alkaloid fraction | AChE | IC50: 15.65 μg/ml | Galanthamine (IC50: 0.711) μg/ml | Galanthamine, Incartine, Lycorine, Anhydrolycorine And Hordenine, Ismine, Demethylmaritidine, 2,11-Didehydro-2-Dehydroxylycorine, Assoanine, 11,12-Didehydroanhydrolycorine, Hippeastrine | |||||

| Alkaloid fraction | ||||||||||

| BuCHE | IC50: 15.85 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Alkaloid fraction | ||||||||||

| Galanthus peshmenii A.P.Davis and C.D.Brickell | Whole plant | – | AChE | IC50: 49.04 μg/ml | Galanthamine (AChE IC50: 0.043) μg/ml (BuCHE IC50: 0.711 ml) | Homolycorine, Ismine, Graciline, Galanthindole, Tazettine, Demethylhomolycorine, Galwesine | GCMS | Bozkurt et al. (2020) | ||

| BuCHE | IC50: 42.05 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Galanthus Gracilis Celak. | Bulb | Alkaloid fraction | AChE | IC50: 27.51 μg/ml | O-methylnorbelladine, ismine, graciline, 5,6-dihydrobicolorine, vitattine, galanthindole, 11,12-dehydrolycorene, tazettine, 11-OH vittatine, lycorine, homolycorine, pinoresinol | GCMS | ||||

| BuCHE | IC50: 35.72 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Aerial | Alkaloid fraction | AChE | IC50: 61.05 μg/ml | Graciline, 5,6-dihydrobicolorine, galanthindole, 6-O-methylpretazettine, tazettine, homolycorine, demethylhomolycorine, 3-O-demethylmacronine, hippeastrine | ||||||

| BuCHE | IC50: 69.83 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Galanthus krasnovii Khokhr. | Bulb | Alkaloid fraction | AChE | IC50: 8.26 μg/ml | Hordenine, O-methylnorbelladine, 1-acetyl-β-Carboline, Trisphaeridine, 5,6-dihydrobicolorine, Vittatine, 11,12-dehydrolycorene, Demethylmaritidine, Anhydrolycorine, 11-OH vittatine, 11,12-didehydroanhydrolycorine, Pseudolycorine | GCMS | ||||

| BuCHE | IC50: 6.23 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Aerial | Alkaloid fraction | AChE | IC50: 23.52 μg/mL | Hordenine, O-methylnorbelladine, 1-acetyl-B-Carboline, 11,12-dehydrolycorene, Anhydrolycorine, 11-OH vittatine, 11,12-didehydroanhydrolycorine, Pseudolycorine | ||||||

| BuCHE | IC50:14.91 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Antibacterial | Galanthus transcaucas-icus Fomin | Bulb | Ethanol extract | Ethanol extract | MIC: 9.275 mg/ml | — | Disruption of membrane structure by inhibiting enzymes in cell wall biosynthesis, protein synthesis and nucleic acid synthesis. | — | Sharifzadeh et al. (2010) | |

| Chloroform fraction | Chloroform fraction | MIC: 1.17 mg/ml | — | — | ||||||

| Galanthus plicatus subsp. byzantinus (Baker) D.A. Webb | Aerial | Ethanol extract | S.epidermidis: S.pyrogene | Zone of inhibition: | Chloramphenicol: S. epidermis 29.75 mm; S. pyogenes | — | Turker and Koyluoglu (2012) | |||

| S. epidermis | 7.25 mm | 33.75 mm, P. vulgaris | ||||||||

| S. pyogenes | 12.50 mm | 20.50 mm; K. pneumonia | ||||||||

| P. vulgaris | 8.25 mm | 28.50 mm | ||||||||

| K. pneumonia | 7.25 mm | |||||||||

| Galanthus transcaucas-icus Fomin | Bulb | Methanol extract | B. subtilis | 0.82 cm | Kanamycin | 2-furancarboxaldehyde , Gallic Acid, Syringic Acid, Catecin And Ferulic Acid | HPLC, GCMS | Karimi et al. (2018) | ||

| B. cereus | 0.71 cm | B. subtilis: 1.28; | ||||||||

| S.aureus | 0.35 cm | B. cereus 1.36; S. aureus 1.17; | ||||||||

| E. coli | 0.85 cm | E. coli 1.42; | ||||||||

| P. aeruginosa | 0.46 cm | P. aeruginosa 1.21 cm | 2,3-butanediol, Acetic acid, Naringin, Quercetin, Apigenin, Genistein | |||||||

| Flower | Methanol extract | B. subtilis | 1.05 cm | |||||||

| B. cereus | 1.22 cm | |||||||||

| S.aureus | 0.76 cm 76 cm | |||||||||

| E. coli | 1.16 cm | |||||||||

| P. aeruginosa | 0.98 cm | |||||||||

| Shoot | Methanol extract | B. subtilis | 1.12 cm | Acetic acid, n-hexadecenoic acid, 4H-pyran-4-one, Naringin, Quercetin, Apigenin, Genistein | ||||||

| B. cereus | 1.18 cm | |||||||||

| S.aureus | 0.92 cm | |||||||||

| E. coli | 1.29 cm | |||||||||

| P. aeruginosa | 1.06 cm | Gentamicin | Chlorogenic acid, p-coumaric acid, Ferulic acid, Isoquercitrin, Quercitrin | HPLC | Benedec et al. (2018) | |||||

| Galanthus nivalis L. | Aerial | Ethanol extract | S. enteritidis | 6 mm | S. enteritidis: 19; | |||||

| E coli | 6 mm | E coli 18; | ||||||||

| L. monocytogenes | 10 mm | L. monocytogenes 10; | ||||||||

| S. aureus | 18 mm 8 mm | S. aureus 22 mm; | ||||||||

| C. albicans | 6 mm | Fluconazole: | ||||||||

| A. brasillensis | 16 mm | C. albicans 25 mm, | ||||||||

| 16 mm | Amphotericin B: | |||||||||

| A. brasillensis: 21 mm | ||||||||||

| S. enteritidis | MIC: 625 mm | |||||||||

| E coli | 2,500 mm | |||||||||

| L. monocytogenes | 312.5 mm | |||||||||

| S. aureus | 19.53 mm | |||||||||

| C. albicans | 19.53 mm | |||||||||

| A. brasillensis | 1,250 mm | |||||||||

| 78.13 mm78.13 mm | ||||||||||

| Antifungal | Galanthus transcaucas-icus Fomin | Bulb | Ethanol extract | C. albicans | MIC: 150 unit/Ml | — | — | Sharifzadeh et al. (2010) | ||

| Chloroform fraction | S. aureus | MIC: 1.17 mg/ml | ||||||||

| Galanthus elwesii Hook.f. | Bulb | Ethanol extract | C. albican | MIC:1024 ug/mL | — | Galanthamine, Tazettine | GCMS | Ločárek et al. (2015) | ||

| C. dubliniensis | 1024 ug/mL | |||||||||

| C. glabrata | 512 ug/mL | |||||||||

| C. dubliniensis | 512 ug/mL | |||||||||

| Galanthamine | C. dubliniensi | MCF512 ug/mL | ||||||||

| L. elongiosporus, | 512 ug/mL | |||||||||

| Tazzetine | C. dubliniensi | 512 ug/mL | ||||||||

| L.elongiosporus | 512 ug/mL | |||||||||

| Galanthus nivalis L. | Aerial | Ethanol extract | C. albicans | Zone of inhibition:6 mm | Fluconazole ( C. albicans 25 mm), Amphotericin B ( A. brasiliensis : 10 mm) | Chlorogenic acid, p-coumaric acid, Ferulic acid, Isoquercitrin, Quercitrin | HPLC | Benedec et al. (2018) | ||

| A. brasiliensis | 16 mm | |||||||||

| A. brasiliensis | MIC: 78.13 μg/ml | |||||||||

| C. albicans | MIC: 1250 μg/ml | — | ||||||||

| Antiprotozoal | Galanthus trojanus A.P.Davis and Özhatay | Whole plant | Arolycoricidine | T. b. rhodesiense | IC50 5.99 μg/ml | Melarsoprol ( T b. rhodesiense | Direct inhibition of the enzyme involved in the fatty acid biosynthesis (FAS) pathway. | 1-O-acetyldihydromethylpseudolycorine N-oxide, 11-hydroxyvittatine N-oxide, Arolycoricidine , (+)-haemanthamine, (+)-narcidine, O-methylnorbelladine, (–)-stylopine, (–)-dihydrolycorine, protopine, (+)-8-O-Demethylmaritidine, Nicotinic acid, Tyramine | Column chromatography, preparative TLC | Kaya et al. (2011) |

| P. falciparum | IC50: 0.004 μg/ml), Benznidazole ( T. cruzi | |||||||||

| T. b. rhodesiense | IC50: 0.36 μg/ml), Chloroquine (P. falciparum | |||||||||

| T. b. rhodesiense | IC50 4.44 μg/ml | IC50: 0.0065 μg/ml) | ||||||||

| (+)-haemanthamine | T. cruzi | IC50 3.35 μg/ml | ||||||||

| P. falciparum | IC50 4.44 μg/ml | |||||||||

| T. b. rhodesiense | IC50 1.80 μg/ml | |||||||||

| P. falciparum | IC50 2.75 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Dihydrolycorine | Cytotoxicity | IC50 3.10 μg/ml | ||||||||

| L6 cells | IC50 0.23 μg/ml | |||||||||

| KB cells | IC50 > 90 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Stylopine | T. b. rhodesiense | IC50 > 50 μg/ml | ||||||||

| P. falciparum | IC50 8.71 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Protopine | Cytotoxicity | IC50 0.50 μg/ml | ||||||||

| L6 cells | IC50 63.30 μg/ml | |||||||||

| KB cells | IC50 > 50 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Antiviral | Galanthus. elwesii Hook.f. | Bulb | Ethanol extract | Herpes simplex virus | Antiviral conc 8 μg/ml | — | Inhibition of the viral replication and host cell lysis. | Galanthus nivalis agglutinin (GNA) | Hudson et al. (2000) | |

| Bulb | Ethanol extract | Sindbis virus | Antiviral conc 16 μg/ml | — | Direct inactivation of the viral particles. | |||||

| Galanthus reginae-olgae Orph. subsp. vernalis Kamari | Aerial | Methanol extract | DPPH | IC50: 39 ± 0.067 μg/ml | DPPH:Ascorbic acid (2 ± 0.011 μg/ml) | Direct inhibition of ROS | — | GCMS | Conforti et al. (2010) | |

| Lipid Peroxidation | 1000 μg/ml | Lipid Peroxidation: Propyl gallate (7 ± 0.017 μg/ml) | Inhibition of formation of free malonaldehyde (MDA) as the result of oxidation in lipid | |||||||

| β-Carotene bleaching | 11 ± 0.016 μg/ml | β-Carotene bleaching: Propyl gallate; (1 ± 0.009 μg/ml), DPPH:Ascorbic acid (2 ± 0.011 μg/ml) | Inhibition of peroxyl radicals damage on β-Carotene | |||||||

| Hexane fraction | DPPH | IC50: > 1,000 μg/ml | 1-metil-4-etossi-, δ, (3)pirrolin-2-one, Neophytadiene, Exadecanoic acid, methyl ester, Exadecanoic acid, 9,12-Octadecandienoic acid, methyl ester, [E, E], 9,12,15-octadecantrienoic acid, methyl ester, [Z, Z,Z], 2-exadecen-1-ol-3,7,11,15-tetramethyl-[R-[R*,R*-(E)]], 9,12,15-octadecantrienal, 9,12-octadecandienoic acid [Z,Z]-2-idrossi-1-[idrossimethyl] ethylester, 2-monolinolenin, 1-octadecene, 9-α-fluoro-5-α-cholest-8(14)-ene-3,15-dione, Vitamin E, Ergost-5-en-3-ol, (3.β.,24 E), Stigmast-5-en-3-ol, (3.β.,24 S), Stigmast-5,24(38)-dien-3-ol, (3.β.,24 E) | |||||||

| Lipid Peroxidation | >1000 μg/ml | |||||||||

| β-Carotene bleaching | 16 ± 0.045 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Alkaloid fraction | DPPH | IC50: 146 ± 0.238 μg/ml | Galanthamine, Lycorine, Tazettine | |||||||

| Lipid Peroxidation | 74 ± 0.139 μg/ml | |||||||||

| β-Carotene bleachingβ-Carotene bleaching: | 9 ± 0.018 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Ethyl acetate fraction | DPPH | IC50: 10 ± 0.020 μg/ml | ||||||||

| Lipid Peroxidation | 962 ± 1.231 μg/ml | |||||||||

| β-Carotene bleaching | 12 ± 0.017 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Bulb | Methanol extract | DPPH | IC50: 29 ± 0.051 μg/ml | — | Neophytadiene, Exadecanoic acid, methyl ester, 9,12-Octadecandienoic acid, methyl ester,[E,E], 9,12,15-octadecantrienoic acid, methyl ester,[Z,Z,Z], 9,12-octadecandienoic acid [Z,Z]-2-idrossi-1-[idrossimethyl] ethylester | |||||

| Lipid Peroxidation | 1000 μg/ml | |||||||||

| β-Carotene bleaching | 92 ± 0.231 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Hexane fraction | DPPH | IC50: > 1,000 μg/ml | ||||||||

| Lipid Peroxidation | 1,000 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Lipid Peroxidation | >100 μg/ml | |||||||||

| β-Carotene bleaching | ||||||||||

| Alkaloid fraction | DPPH | IC50: 15 ± 0.031 μg/ml | Galanthamine, Lycorine, Tazettine, Crinine, Neronine | |||||||

| Lipid Peroxidation | 273 ± 0.345 μg/ml | |||||||||

| β-Carotene bleaching: | 15 ± 0.035 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Ethyl acetate fraction | DPPH | IC50: 148 ± 0.231 μg/ml | — | |||||||

| Lipid Peroxidation | 1000 μg/ml | |||||||||

| β-Carotene bleaching: | 10 ± 0.019 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Galanthus transcaucas-icus Fomin | Bulb | Methanol extract | DPPH | IC50: 171.07 μg/ml | Vitamin C (65.62 μg/ml), Vitamin E | Direct inhibition of ROS. | 2-furancarboxaldehyde | HPLC, GCMS | Karimi et al. (2018) | |

| (60.39 μg/ml), BHT (83.75 μg/ml) | ||||||||||

| Flower | DPPH | IC50: 132.61 μg/ml | 2,3-butanediol, Acetic acid | |||||||

| Shoot | DPPH | IC50: 125.07 μg/ml | Acetic acid, n-hexadecenoic acid, 4H-pyran-4-one | |||||||

| Galanthus transcaucas-icus Fomin | Bulb | ABTS | IC50: 292.73 ± 1.94 μg/ml | Trolox (191.36 ± 2.02 μg/ml) | Gallic acid, Syringic acid, Catechin, Ferulic acid, Naringin, fla, rutin | |||||

| Flower | ABTS | IC50: 267.47 ± 1.45 μg/ml | Gallic acid, Resorcinol, Syringic acid, Naringin, Quercetin, Apigenin, Genistein | |||||||

| Shoot | ABTS | IC50: 238.27 ± 1.61 μg/ml | Gallic acid, Syringic acid, ferulic acid, Naringin, Quercetin, Kaempferol, Genistein | |||||||

| Galanthus transcauca-sicus Fomin | Bulb | Methanol extract | FRAP | IC50: 151.21 ± 1.28 μg/ml | Vitamin C (96.15 ± 1.37) μg/ml, Vitamin E (66.84 ± 1.72 μg/ml), BHT (83.75 ± 1.87 μg/ml) | Reducing ferric ion (3+) to form ferrous ion (2+). | Gallic acid, Syringic acid, catecin, Ferulic acid, Naringin, Kaempferol, Rutin | |||

| Flower | FRAP | IC50: 137.05 ± 1.36 μg/ml | Gallic acid, Resorcinol, Syringic acid, Naringin, Quercetin, Apigenin, Genistein | |||||||

| Shoot | FRAP | IC50: 107.42 ± 1.03 μg/ml | Gallic acid, Syringic acid, Ferulic acid, Naringin, Quercetin, Kaempferol, Genistein | |||||||

| Galanthus woronowii Losinsk. | — | Hexane extract | DPPH | IC50: 69.07 ± 0.42 μg/ml | BHT (9.92 ± 0.23 μg/ml), BHA (5.37 ± 0.21 μg/ml), Trolox (5.77 ± 0.12 μg/ml) | Direct inhibition of ROS. | – | Genç et al. (2019) | ||

| Chloroform extract | DPPH | IC50: 34.63 ± 0.21 μg/ml | ||||||||

| Ethyl acetate extract | DPPH | IC50: 28.14 ± 0.40 μg/ml | ||||||||

| Galanthus woronowii Losinsk. | — | Hexane extract | CUPRAC | 0.49 ± 0.03 μmol TE/mg | BHT (3.63 ± 0.18), BHA (2.87 ± 0.18) | Reducing copper (2+) to copper (+). | — | |||

| Chloroform extract | CUPRAC | 0.98 ± 0.17 μmol TE/mg | ||||||||

| Ethyl acetate extract | CUPRAC | 0.72 ± 0.01 μmol TE/mg | ||||||||

| Galanthus woronowii Losinsk. | — | Hexane extract | ABTS | IC50: 28.51 ± 1.27 μg/ml | BHT (5.38 ± 0.18 μg/ml), BHA (8.80 ± 0.06 μg/ml), Trolox (5.57 ± 0.09 μg/ml) | Direct inhibition of cation ROS. | — | |||

| Chloroform extract | ABTS | IC50: 16.84 ± 0.49 μg/ml | ||||||||

| Ethyl acetate extract | ABTS | IC50: 13.09 ± 0.20 μg/ml | ||||||||

| Galanthus krasnovii Khokhr. | — | Dichloromethane extract | CUPRAC | 1.15 µmol TE/mg | — | Reducing copper (2+) to copper (+). | — | Erenler et al. (2019) | ||

| Ethyl acetate extract | CUPRAC | 0.77 μmol TE/mg | ||||||||

| Hexane extract | CUPRAC | 0.75 μmol TE/mg | ||||||||

| Galanthus krasnovii Khokhr. | — | Dichloromethane extract | ABTS | 14.33 μg/ml | BHA (8.8 μg/ml) | |||||

| Ethyl acetate extract | ABTS | 14.98 μg/ml | ||||||||

| Galanthus nivalis L. | Leaf | Methanol extract | DPPH | 77% | Ascorbic acid (93%) | – Galanthamine | HPLC | Bulduk and Karafakıoğlu (2019) | ||

| Leaf | ABTS | 20 ± 0.78 μmol TE/100 g | Trolox | — | ||||||

| Bulb | ABTS | 19 ± 0.80 μmol TE/100 g | Trolox | |||||||

| Galanthus elwesii Hook.f. | Leaf | Methanol extract | ABTS | 20 ± 0.85 μmol TE/100 g | ||||||

| Bulb | ABTS | 17 ± 0.78 μmol TE/100 g | ||||||||

| Galanthus woronowii Losinsk. | Leaf | ABTS | 23 ± 0.64 μmol TE/100 g | |||||||

| Bulbs | ABTS | 21 ± 0.710 μmol TE/100 g | ||||||||

| Anticancer | Galanthus kemulariae Kuth. (accepted name: Galanthus lagodechia-nus Kem.-Nath.) | Aerial | Methanol extract | HCT-116 | CC50: 36.4 ± 1.8 μg/ml | Galanthamine (>28.7 μg/ml), Tazettine (>33.1 μg/ml), Lycorine (0.88 μg/ml) | Signal-induced programmed cell death (apoptosis). | — | Jokhadze et al. (2007) | |

| HeLa | CC50: 58.2 ± 5.9 μg/ml | |||||||||

| HL-60 | CC50: 53.8 ± 6.4 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Bulb | Methanol extract | HCT-116 | CC50: 12.2 ± 2.7 μg/ml | |||||||

| HeLa | CC50: 37.1 ± 4.7 μg/ml | |||||||||

| HL-60 | CC50: 34.3 ± 3.9 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Galanthus lagodechia-nus Kem.-Nath. | Bulb | Methanol extract | HCT-116 | CC50: 11.1 ± 3.4 μg/ml | Galanthamine (>28.7 μg/ml), Tazettine (>33.1 μg/ml), Lycorine (0.88 μg/ml) | — | ||||

| HeLa | CC50: 34.8 ± 6.3 μg/ml | |||||||||

| HL-60 | CC50: 45.6 ± 3.5 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Galanthus woronowii Losinsk. | Aerial | Methanol extract | HCT-116 | CC50: 22.0 ± 3.8 μg/ml | Galanthamine (>28.7 μg/ml), Tazettine (>33.1 μg/ml), Lycorine (0.88 μg/ml) | – | ||||

| HeLa | CC50: 41.3 ± 3.3 μg/ml | |||||||||

| HL-60 | CC50: 39.4 ± 2.8 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Galanthus krasnovii Khokhr. | Bulb | Methanol extract | HCT-116 | CC50: 5.8 ± 0.9 μg/ml | Galanthamine (>28.7 μg/ml), Tazettine (>33.1 μg/ml), Lycorine (0.88 μg/ml) | — | ||||

| HeLa | CC50: 15.4 ± 3.7 μg/ml | |||||||||

| HL-60 | CC50: 13.8 ± 1.2 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Bulb | Methanol extract | HCT-116 | CC50: 7.7 ± 1.6 μg/ml | |||||||

| HeLa | CC50: 18.9 ± 3.9 μg/ml | |||||||||

| HL-60 | CC50: 22.0 ± 2.4 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Galanthus alpinus Sosn. | Bulb | Methanol extract | HCT-116 | CC50: 9.6 ± 0.8 μg/ml | Galanthamine (>28.7 μg/ml), Tazettine (>33.1 μg/ml), Lycorine (0.88 μg/ml) | — | ||||

| HeLa | CC50: 21.3 ± 4.5 μg/ml | |||||||||

| HL-60 | CC50: 23.7 ± 1.7 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Galanthus shaoricus Kem.-Nath. | Bulb | Methanol extract | HCT-116 | CC50: 8.9 ± 1.6 μg/ml | Galanthamine (>28.7 μg/ml), Tazettine (>33.1 μg/ml), Lycorine (0.88 μg/ml) | — | ||||

| HeLa | CC50: 17.2 ± 2.1 μg/ml | |||||||||

| HL-60 | CC50: 16.4 ± 0.9 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Galanthus platyphyllu-s Traub and Moldenke | Bulb | Methanol extract | HCT-116 | CC50: 14.2 ± 2.7 μg/ml | alanthamine (>28.7 μg/ml), Tazettine (>33.1 μg/ml), Lycorine (0.88 μg/ml) | — | ||||

| HeLa | CC50: 11.5 ± 1.7 μg/ml | |||||||||

| HL-60 | CC50: 19.1 ± 1.0 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Galanthus caucasicus (Baker) Grossh. (accepted name: Galanthus alpinus var. alpinus) | Aerial | Methanol extract | HCT-116 | CC50: 49.5 ± 4.8 μg/ml | Galanthamine (>28.7 μg/ml), Tazettine (>33.1 μg/ml), Lycorine (0.88 μg/ml) | — | ||||

| HeLa | CC50: 42.8 ± 2.8 μg/ml | |||||||||

| HL-60 | CC50: 39.3 ± 2.3 μg/ml | |||||||||

| Bulb | Methanol extract | HCT-116 | CC50: 23.4 ± 3.7 μg/ml | Galanthamine (>28.7 μg/ml), Tazettine (>33.1 μg/ml), Lycorine (0.88 μg/ml) | ||||||

| HeLa | CC50: 32.1 ± 3.7 μg/ml | |||||||||

| HL-60 | CC50: 31.9 ± 1.5 μg/ml |

Pharmacological activities of Snowdrop.

Effective dose: Dose that gives significant results with p < 0.05, p < 0.01, p < 0.001.

1H-NMR, hydrogen-1 nuclear magnetic resonance; ABTS, 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid); ACh, acetylcholine; AChE, acetylcholinesterase; BHA, butylated hydroxyanisole; BHT, butylated hydroxytoluene; CC50, half maximal cytotoxic and inhibitory concentration; DPPH, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl; EC50, half maximal effective concentration; EIMS, electron ionization mass spectrometry; GC-MS, gas chromatography-mass spectrometry; HPLC, high performance liquid chromatography, IC50, half maximal inhibitory concentration; MIC, minimal inhibitory concentration; MFC, minimal fungicidal concentration; NA, no activity; NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SE, standard error; TLC, thin layer chromatography.

Anticholinesterase Activity

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE), aenzyme remain a highly viable target to alleviate the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Kostelník and Pohanka, 2018). AChE (specific cholinsterase) is present in nervous system and terminates neurotransmission, while the activity of BChE is increase during the late stage of AD (Mesulam and Geula, 1994; Khaw et al., 2014; Kostelník and Pohanka, 2018). Galanthamine is known to enhance the activity of acetylcholine (ACh) by inhibiting the enzyme AChE and functions as a nicotinic activator by interacting with nicotinic ACh receptors (nAChRs) in the brain (Maelicke et al., 1997). The interaction between the Ach inhibitor and nAChR induces conformational change of the receptor molecule, and subsequent activation of nAChRs is believed to have protective effects against β-amyloid cytotoxicity of neuron cells (Coyle and Kershaw, 2001). Snowdrops are important source of anti-neurodegeneration compound “galanthamine” thanks to the traditional knowledge in which the extract has been used in folk medicine for neurological conditions (Ago et al., 2011). Due to limited number of drugs available for the management of Alzheimer disease, significant efforts have been made to explore anticholinesterase inhibitor from medicinal plants (Khaw et al., 2014; Tan et al., 2014; Jamila et al., 2015; Liew et al., 2015; Khaw et al., 2020).

The anti-cholinesterase activities of the Galanthus spp including Galanthus Nivalis, Galanthus elwesii, Galanthus ikariae, Galanthus gracilis, Galanthus xvalentinen, Galanthus rizehensis, Galanthus cilicicus, were assessed in-vitro by determining their inhibitory activities via Ellman method (Table 2). Rhee et al. (2003) showed that the methanol extract of G. nivalis had 96% inhibition against AChE (Rhee et al., 2003). Chloroform:methanol (1 : 1) extracts of the bulbs of G. elwesii and G. ikariae inhibited AChE at 73.18 and 75.56% (10 μg/ml), comparable to the alkaloid extracts at 77.23 and 76.96% (10 μg/ml) (Orhan and Şener, 2005). Phytochemical study of alkaloid extract of G. ikariae yielded amaryllidaceae-type alkaloids, including lycorine (IC50 = 3.16 µM), tazettine, crinine, galanthamine (IC50 = 3.2 µM), 3-epi-hydroxybulbispermine and 2-demethoxymontanine. A study of Kaya and colleagues demonstrated that bulb and aeries parts of G. cilicicus selective towards AChE than BuChE, suggesting the present of selective AChE compounds within the extract.

Similarly, methanol extracts of the bulb and aerial part of G. elwesii were selectively inhibited AChE (Bozkurt et al., 2013a; Kaya et al., 2017). Subsequent GCMS analysis revealed the present of alkaloids in the G. elwesii extract including Galanthamine, O-methylleucotamine, hordenine and sanguinine (Bozkurt et al., 2017). The alkaloid extracts of the G. gracilis bulb and G. xvalentinei nothosubsp. Subplicatus were moderately inhibiting AChE with the IC50 of 11.82–25.5 µg/ml (Sarikaya et al., 2013; Bozkurt-Sarikaya et al., 2014). The bulb of G. krasnovii alkaloid was dual cholinesterase inhibitor with the IC50 of 8.26 µg/ml (AChE) and IC50 of 6.23 µg/ml (BuChE) (Bozkurt et al., 2020). GCMS analysis revealed that anhydrolycorine and 11,12-didehydroanhydrolycorine were the dominant compounds in the extract contribute to the inhibitory activities.

The findings showed that alkaloids from Galanthus spp played an important role in cholinesterase inhibitory activities. Among the alkaloids, lycorine-type alkaloids dominated in the studied extracts. Galanthamine and tazettine-type alkaloids were present in very low amounts. The alkaloid content in the bulb was more prominent than the aerial parts. The findings showed that inhibitory activity might be due to the synergistic interactions between the alkaloids within the extract. Taking into account that existing drugs are effective mild to moderate progression of AD and presenting considerable side effects, the search for effective and selective cholinesterase inhibitors with minimum side effects is imperative. It can be conclude that, the bulb of Galanthus spp. can be served as a source of anticholinesterase alkaloids in addition to their ornamental properties.

Antimicrobial Activity

The emergence of new infectious diseases and drug resistance to antibiotic is one of the biggest threats to global health (Ventola, 2015). Antimicrobial, including antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral and antiprotozoal agents are becoming ineffective, attributed to the overuse and misuse of current existing drugs which leads to resistance (Interagency Coordination Group, 2019). On top of that, diminishing antibiotic pipeline resulted in lesser treatment options against multiple drug resistance pathogens and responsible for at least 700,000 casualties each year (Interagency Coordination Group, 2019). Natural products are promising new drug candidates in treating antibiotic-resistant infections. Natural products have evolved in natural selection process adapting to various abiotic and biotic stresses where abundant of undiscovered biologically active metabolites for drug discovery. Natural products have always been an important part of drug discovery and intense research has been conducted in this area since the discovery of penicillin in the forties.

Antibacterial

Turker and Koyluoglu (2012) reported antibacterial activity of ethanol extract of G. Plicatus against Gram-positive Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus pyrogenes and Gram-negative Proteus vulgaris and Klebsiella pneumoniae obtained from disc-diffusion method (Turker and Koyluoglu, 2012). Growth inhibitions (7.25 ± 0.25 to 12.50 ± 0.50 mm) were compared with positive controls such as chloramphenicol, tetracycline, ampicillin, carbenicillin and erythromycin. In another study, the ethanol and chloroform extracts of G. transcaucasicus showed antibacterial activity against Bacillus subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus at MIC values of 9.275 mg/ml and 1.17 mg/ml, respectively (Sharifzadeh et al., 2010). The methanol extracts of the bulb, flower and shoot of G. transcaucasicus were evaluated for their antibacterial activity against Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus cereus, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Karimi et al., 2018). Overall, the antibacterial activity of shoot extract appeared to be most potent followed by flower and bulb extracts. The main and predominant volatile compounds such as acetic acid (13.6%), 2,3-Butanediol (43.13%) and 2-Furancarboxaldehyde (68.77%) were major in shoot, flower and bulb extracts of G. transcaucasicus, respectively. G. nivalis extract has demonstrated moderate anti-staphylococcal activity, with the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) value of 19.53 μg/ml (Benedec et al., 2018). Interestingly, G. nivalis extract exhibited comparable antibacterial activity with standard drug, gentamicin. Phytochemical analysis of G. nivalis extract revealed that chlorogenic acid (2976.19 ± 12.80 μg/g) was the main constituent, followed by p-coumaric acid (73.02 ± 0.07 μg/g), ferulic acid (26.80 ± 0.19 μg/g), isoquercitrin (25.08 ± 0.31 μg/g) and quercitrin (11.13 ± 0.06 μg/g).

Antifungal

The antifungal activity of ethanol extract of the bulb of G. transcaucasicus against yeast Candida albicans stood at MIC values of 19.53 μg/ml to 2,500 μg/ml (Sharifzadeh et al., 2010). A study by Ločárek and colleagues showed that alkaloid extract of the bulb of G. elwesii inhibited the growth of Candida spp. and Lodderomyces elongisporus (Ločárek et al., 2015). Galanthamine was the major compound in the alkaloid extract, followed by tazettine and minute amount of haemantamine as analyzed by GCMS. Benedec et al. (2018) reported antifungal activity of G. nivalis against C. albicans and filamentous fungi, Aspergillus brasiliensis (Benedec et al., 2018). Phytochemical analysis showed that chlorogenic acid was the dominant phenolic acid within G. nivalis extract.

Antiprotozoal

Amaryllidaceae alkaloids have previously been tested to possess antiparasitic activities (Campbell et al., 2000; Toriizuka et al., 2008) Antiprotozoal activity of the compounds isolated from alkaloid extract was tested against a panel of parasitic protozoa consisting of Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense, Trypanosoma cruzi, Leishmania donovani, and Plasmodium falciparum, which are responsible for human African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness), American trypanosomiasis, Kalaazar (visceral leishmaniasis) and malaria were evaluated in vitro by Plasmodial FAS-II enzyme inhibition assay (Kaya et al., 2011). Arolycoricidine (+)-haemanthamine, dihydrolycorine, and protopine were active against T. b. rhodesiense, while (+)-haemanthamine was active against T. cruzi with the IC50 less than 10 μg/ml. Arolycoricidine (+)-haemanthamine, stylopine and protopine were reported potentially against P. falciparum, where stylopine and protopine exhibited sub-microgram inhibition with the IC50 values of 0.23 and 0.50 μg/ml In addition, stylopine and protopine demonstrated good cytotoxicity (L6 and KB cells) selectivity index grant these compounds as promising lead for further development. The study showed that most of the active compounds are of lycorine type-alkaloids, in which O-methylnorbelladine (–)-dihydrolycorine and (+)-8-O-demethylmaritidine are being reported here for the first time from the genus Galanthus. Amaryllidaceae-derived haemanthamine displayed remarkable cytotoxicity against primary mammalian cell line (L6) and the human carcinoma cell line (KB) (Kaya et al., 2011).

Lycorine, an Amaryllidaceae alkaloid from snowdrop possesses strong antimalarial activity (Khalifa et al., 2018). It was potently inhibited the growth of P. falciparum, the causative agent of malaria, with a low cytotoxic profile against human hepatocarcinoma cells (HepG2) (Gonring-Salarini et al., 2019).

In general, antimalarial agents manifest their action by targeting enzymes associated with the plasmodial FAS-II biosynthetic pathways (Nair and Staden, 2019). It inhibits DNA topoisomerase-I activity which is required for cell growth in parasites and causes cell cycle arrest in vivo (Cortese et al., 1983). The results suggested that the antimalarial activities of lycorine derivatives might be due to the free hydroxyl groups at C-1 and C-2 or esterified as acetates or isobutyrates. The presence of a double bond between C-2 and C-3 is important for the activity (Cedrón et al., 2010; He et al., 2015). Overall, these results suggested that Galanthus spp. is potentialantiprotozoal agent for further development.

Antiviral

Among the microbes, virus infection has emerged as a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide (Luo and Gao, 2020). Recent outbreak has underscored their prevention as a critical issue in safeguarding public health with very limited number of antivirals drugs, vaccines and antiviral therapies available (Babar et al., 2013).

Lectin from snowdrops is being investigated for its anti-viral potential. The Galanthus nivalis agglutinin (GNA) was identified and purified from the bulb of snowdrop (Van Damme et al., 1987). GNA is known to possess virucidal properties against human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) at the EC50 = 0.12 ± 0.07 μg/ml to 4.7 ± 3 μg/ml (Balzarini et al., 2004). The molecular mechanisms of GNA exerting antiviral activities via carbohydrate-binding activities, thereby blocking the entry of the virus into its target cells and transmission of the virus by deleting the glycan shield in its envelope protein, thus neutralizing antibody.

G. elwesii’s ethanol extract was tested for its anti-herpes simplex virus (HSV) and anti-sindbis virus (SINV) activity. G. elwesii has higher activity in the virucidal (8 µg/ml) assay than the plaque-forming assay (24 µg/ml) (Hudson et al., 2000). G. elwesii extract was potent against SINV, it showed anti-SINV activity at the dose of 16 µg/ml.

Most of the mannose-binding lectins exert anti-coronavirus potential except the lectins from garlic (Keyaerts et al., 2007). They interfered with viral attachment in early stage of replication cycle and suppressed the growth by interacting at the end of the infectious virus cycle. The virucidal effect of GNA against SARS-CoV was recorded at EC50 of 6.2 ± 0.6 μg/ml (Keyaerts et al., 2007). Other GNA-related lectins may exert anti-influenza activities by competitively blocking the combination of influenza A virus envelope glycoprotein haemagglutinin (HA) with its corresponding sialic acid-linked receptor in the host cell, such as H1N1 (Yang et al., 2013). A study evaluated the antiviral potential of plant lectins from a collection of medicinal plants on feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV) infected cells. The results indicated that plants derived mannose-binding lections had strongest anti-coronavirus activitity and Galanthus nivalis was one of the coronavirus-inhibiting plants (Adams, 2020).

To sum up, lectin GNA might be a potential target for further development for its anti-CoV potential. Although no CoV treatments have been approved, pharmacotherapies for MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV may lay the foundation for treatment of the novel human Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Antioxidant Activity

Natural antioxidants play a role in preventing cellular free radicals or reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation as well as facilitating repair process from the damage caused by ROS induced oxidative stress which involves in various chronic diseases, such as atherosclerosis, myocardial infections, cancer and neurodegenerative diseases (Bulduk and Karafakıoğlu, 2019). Antioxidants can act as chain breakers, radical scavengers, singlet oxygen quenchers, hydroperoxides decomposers, and pro-oxidative metal ions chelators (Pisoschi et al., 2016).

The antioxidant potential of the aerial and bulb of G. reginae-olgae was determined by free radical scavenging DPPH, lipid peroxidation and β-carotene bleaching tests (Conforti et al., 2010). The result showed that methanol extracts of aerial and bulb of G. reginae-olgae had moderate DPPH scavenging potential. Further fractionation of the extracts indicate that the strongest DPPH scavenging of aerial part was ethyl acetate fraction, while alkaloid fraction of bulb showed highest scavenging potential. The results showed that the DPPH scavenging activity of ethyl acetate and alkaloid fractions of aerial and bulb attributed to their distinct chemical diversity The shoot of G. transcaucasicus exhibited higher antioxidant activities compare to bulb and flower that concurred with the high phenolic and flavonoid compounds in shoot. In a comparative study, the ethanol extract of G. woronowii exhibited highest DPPH and 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid (ABTS) scavenging activity (IC50 = 28.14 μg/ml and 13.09 μg/ml, respectively) (Genç et al., 2019). While dichloromethane extract displayed greater reducing potential in cupric ion reducing power assay that ethanol extract. Antioxidant activity of hexane, dichloromethane and ethyl acetate extracts of G. krasnovii were investigated via DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging and cupric ion reducing power assay (Erenler et al., 2019). Dichloromethane extract demonstrated the highest ABTS activity (IC50 = 14.33 μg/ml) and reducing power (1.15 µmol TE/mg). DPPH and ABTS method were also been used to investigate the methanol extracts of the leaf and bulb of three Galanthus spp. (Bulduk and Karafakıoğlu, 2019). The G. woronowii leaf extract recorded the highest DPPH scavenging activity (77%), whereas all extracts from G. nivalis, G. elwesii and G. woronowii showed comparable ABTS scavenging activity (17 ± 0.78 – 23 ± 0.64 µmol TE/100 g). HPLC analysis showed that content of galantamine was higher in the aerial parts (leaves) when compared to the underground parts (bulbs) which may contributed to the higher scavenging activity of the leaf extract.

Apparently, Galanthus spp. appears to be potent source of antioxidants which are enriched with various phytochemicals phenolic acids, flavonoids, and alkaloids (Karimi et al., 2018). It is envisaged that secondary metabolites from Galanthus spp. may reduce the risk and slow down the progression of chronic diseases including cancers, cardiovascular diseases and neurodegenerative diseases.

Anticancer Activity

Cancer is a chronic disease, which is account for millions of deaths each year (Tan et al., 2016; Tay et al., 2019). Chemotherapy, radiotherapy and recently, immunotherapy are essential means for the treatment of cancers. Severe toxicity and cell resistance to drugs are the major drawback in conventional cancer therapies. In order to circumvent these issues, new cellular targets and anticancer agents are needed, especially those of natural origin. From 1981 to 2002, natural products were the basis of 74% of all new chemical entities for cancer (Demain and Vaishnav, 2011).

Eight different Galanthus species were tested for their anticancer activity on Human colorectal carcinoma cells (HCT-116), Human promyelocytic leukemia cells (Hela) and Human cervical cancer cells (HL-60) (Jokhadze et al., 2007). All methanol extracts from the galanthus species showed cytotoxic activities, in which the bulbs had higher activity than the aerial parts. Majority of the species were more active against HCT-116 cells, except G. platyphyllus bulbs were more active against HeLa cells than other cell lines, indicating an interesting specificity that should be investigated in future studies. The bulbs of G. woronowii, G. krasnowii, G. shaoricus and G. alpinus were the most cytotoxic (IC50 < 10 µg/ml) on HCT-116 cells. Lycorine had cytotoxicity against HCT-116, HL-60 and Hela cells with IC50 of 3.1, 8.2, and 9.3 µM. Meanwhile, galanthamine and tazettine were weakly cytotoxic against HCT-116, HL-60 and Hela cells, with IC50 > 100 µM. It is suggesting that the present of lycorine in the Galanthus spp contributed to the cytotoxic effects on the tested cancer cells. The search for novel anticancer agents from natural sources has been successful worldwide. For over 50 years, natural products have served us well in combating cancer and is still a priority goal for cancer therapy, due to the chemotherapeutic drugs resistance.

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Natural products remain to be a wealthy source for the identification of novel therapeutic agents for the treatment of human diseases. Plants contain a significant numbers of phytochemical components, most of which are known to be biologically active and responsible for various pharmacological activities. It was demonstrated that plant secondary metabolites are preferred natural antioxidants than synthetic ones due to safety concerns. Given the natural abundance of bioactive compounds in this plant, Galanthus spp. can be recognized as an interesting source of natural products with a wide range of biological activities. This review highlights the importance of bioactive substances of various extracts of Galanthus spp. on anti-cholinesterase inhibitory activity and other diseases, supporting the therapeutic possibilities for the use of snowdrops. The most promising compound is galanthamine which exhibited greater activity than tazettine, crinine and lycorine. However, current research on the underlying mechanism of actions and the exact chemical constituent involved are scarce. Apart from the above mentioned activities, other ethnopharmacological uses of snowdrops need to be substantiated with strong scientific studies for its extensive usage in various therapies. Thus, this review may serve as a guide for future researchers in pharmacology to conduct further studies on these plants by providing different perspective. The discussion is expected to inspire further isolation, identification, mechanism of actions and synthetic studies of the existing and novel active compounds from the Galanthus spp. to gain a better understanding of the basis of the activity at the cellular and molecular level in future.

Statements

Author contributions

The writing was performed by CK, LL, KK, and BG. While WS, WY, PG, LM, AM, KK, and BG provided vital guidance, editing and insight to the work. The project was conceptualized by BG and PG.

Funding

This work was financially supported by Monash Global Asia in the 21st Centrury (GA21) research grants (GA-HW-19-L01 and GA-HW-19-S02), Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS/1/2019/WAB09/MUSM/02/1 and FRGS/1/2019/SKK08/TAYLOR/02/02), Taylor’s University Emerging Grant (TRGS/ERFS/2/2018/SBS/016) and External Industry Grant from Biotek Abadi Sdn Bhd (vote no. GBA-8188A).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Aaron P. Davis, Senior Research Leader of Plant Resources at Royal Botanic Kew Gardens for his excellent photographs in Figures 2A–D.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1

AdamsC. (2020). Can red algae and mannose-binding lectins fight coronavirus (COVID-19). J. Plant Med.

2

AgoY.KodaK.TakumaK.MatsudaT. (2011). Pharmacological aspects of the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor galantamine. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 116, 6–17. 10.1254/jphs.11r01cr

3

AschanG.PfanzH. (2006). Why snowdrop (Galanthus nivalis L.) tepals have green marks?. Flora–Morphol. Distrib. Funct. Ecol. Plants201, 623–632. 10.1016/j.flora.2006.02.003

4

AyE.GülM.AçıkgözM.YarilgaçT.KaraŞ. (2018). Assessment of antioxidant activity of giant snowdrop (Galanthus elwesii Hook) extracts with their total phenol and flavonoid contents. Indian J. Pharm. Educ. Res. 52 (4s), s128–s132. 10.5530/ijper.52.4s.88

5

AyazM.UllahF.SadiqA.KimM. O.AliT. (2019). Editorial: natural products-based drugs: potential therapeutics against Alzheimer’s disease and other neurological disorders. Front. Pharmacol. 10, 1417. 10.3389/fphar.2019.01417

6

BabarM. M.ZaidiN. S.AshrafM.KaziA. G. (2013). Antiviral drug therapy- exploiting medicinal plants. J. Antivir. Antiretrovir. 5, 028–036. 10.4172/jaa.1000060https://www.researchgate.net/deref/http%3A%2F%2Fdx.doi.org%2F10.4172%2Fjaa.1000060

7

BalzariniJ.HatseS.VermeireK.PrincenK.AquaroS.PernoC. Fet al (2004). Mannose-specific plant lectins from the Amaryllidaceae family qualify as efficient microbicides for prevention of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48, 3858–3870. 10.1128/AAC.48.10.3858-3870.2004

8

BaytopT. (1999). Therapy with plants in Turkey. (Past and Present). 2nd Edn. Istanbul, TR: Nobel Medicine Publications.

9

BenedecD.OnigaI.HanganuD.GheldiuA. M.PuşcaşC.Silaghi-DumitrescuR.et al (2018). Sources for developing new medicinal products: biochemical investigations on alcoholic extracts obtained from aerial parts of some Romanian Amaryllidaceae species. BMC Compl. Alternative Med. 18, 226. 10.1186/s12906-018-2292-8

10

BishopM.DavisA. P.GrimshawJ. (2001). Snowdrops: a monograph of cultivated galanthus. Netley: Griffin Press.

11

BozkurtB.CobanG.KayaG. I.OnurM. A.Unver-SomerN. (2017). Alkaloid profiling, anticholinesterase activity and molecular modeling study of Galanthus elwesii. South Afr. J. Bot. 113, 119–127. 10.1016/j.sajb.2017.08.004

12

BozkurtB.KayaG. I.OnurM. A.Unver-SomerN. (2020). Chemo-profiling of some Turkish Galanthus L. (Amaryllidaceae) species and their anticholinesterase activity. South Afr. J. Bot. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1016/j.sajb.2020.09.012

13

BozkurtB.KayaG.ÖnürM.BastidaJ.SomerN. (2013a). Phytochemical investigation of Galanthus woronowii. Biochem. Systemat. Ecol. 51, 276–279. 10.1016/j.bse.2013.09.015

14

BozkurtB.SomerN.KayaG.ÖnürM.BastidaJ.BerkovS.et al (2013b). GC-MS investigation and acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity of Galanthus rizehensis. Z. Naturforsch. C Biosci. 68, 118–124. 10.5560/ZNC.2013.68c0118https://www.researchgate.net/deref/http%3A%2F%2Fdx.doi.org%2F10.5560%2FZNC.2013.68c0118

15

Bozkurt-SarikayaB.KayaG. I.OnurM. A.BastidaJ.BerkovS.Unver-SomerN.et al (2014). GC/MS analysis of Amaryllidaceae alkaloids in Galanthus gracilis. Chem. Nat. Compd. 50, 573–575. 10.1007/s10600-014-1022-9

16

BuldukI.KarafakıoğluY. S. (2019). Evaluation of galantamine, phenolics, flavonoids and antioxidant content of Galanthus species in Turkey. Int. J. Biochem. Res. Rev. 25, 1–12. 10.9734/ijbcrr/2019/v25i130068

17

CampbellW. E.NairJ. J.GammonD. W.CodinaC.BastidaJ.ViladomatF.et al (2000). Bioactive alkaloids from Brunsvigia radulosa. Phytochemistry53, 587–591. 10.1016/s0031-9422(99)00575-0

18

CedrónJ. C.GutiérrezD.FloresN.RaveloÁ. G.Estévez-BraunA. (2010). Synthesis and antiplasmodial activity of lycorine derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 18, 4694–4701. 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.05.023

19

ConfortiF.LoizzoM. R.MarrelliM.MenichiniF.StattiG. A.UzunovD.et al (2010). Quantitative determination of Amaryllidaceae alkaloids from Galanthus reginae-olgae subsp. vernalis and in vitro activities relevant for neurodegenerative diseases. Pharm. Biol. 48, 2–9. 10.3109/13880200903029308

20

CorteseI.RennaG.Siro-BrigianiG.PoliG.CagianoR. (1983). [Pharmacology of lycorine. 1) Effect on biliary secretion in the rat]. Boll. Soc. Ital. Biol. Sper. 59, 1261–1264.

21

CoyleJ.KershawP. (2001). Galantamine, a cholinesterase inhibitor that allosterically modulates nicotinic receptors: effects on the course of Alzheimer’s disease. Biol. Psychiatr. 49, 289–299. 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01101-x

22

DemainA. L.VaishnavP. (2011). Natural products for cancer chemotherapy. Microb. Biotechnol. 4, 687–699. 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2010.00221.x

23

ElgorashiE. E.ZschockeS.Van StadenJ.EloffJ. N. (2003). The anti-inflammatory and antibacterial activities of Amaryllidaceae alkaloids. South Afr. J. Bot. 69, 448–449. 10.1016/S0254-6299(15)30329-X

24

ErenlerR.GenáN. S.ElmastaM.Emina Ao LuZ. R. (2019). Evaluation of antioxidant capacity with total phenolic content of Galanthus krasnovii (Amaryllidaceae). Turkish J. Biodivers. 2 (1), 13–17. 10.38059/biodiversity.526833

25

GençN.YıldızI.KaranT.EminagaogluO.ErenlerR. (2019). Antioxidant activity and total phenolic contents of Galanthus woronowii (Amaryllidaceae). Turkish J. Biodivers. 2, 1–5. 10.38059/biodiversity.515111

26

Gonring-SalariniK.ContiR.AndradeJ. P. D.BorgesB. R. J. P.AguiarA. C. C.SouzaJ. O. D.et al (2019). In vitro antiplasmodial activities of alkaloids isolated from roots of worsleya procera (Lem.) Traub (Amaryllidaceae). J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 30, 1624–1633. 10.21577/0103-5053.20190061

27

HeM.QuC.GaoO.HuX.HongX. (2015). Biological and pharmacological activities of Amaryllidaceae alkaloids. RSC Adv. 5, 16562–16574. 10.1039/C4RA14666B

28

HeinrichM. (2010). Galanthamine from Galanthus and other Amaryllidaceae–chemistry and biology based on traditional use. Alkaloids – Chem. Biol. 68, 157–165. 10.1016/s1099-4831(10)06804-5

29

HudsonJ. B.LeeM. K.SenerB.ErdemogluN. (2000). Antiviral activities in extracts of Turkish medicinal plants. Pharm. Biol. 38, 171–175. 10.1076/1388-0209(200007)3831-SFT171

30

Interagency Coordination Group (2019). “No time to wait – securing the future from drug-resistant infections,” in Report to the secretary general of the nations (United Nations). Available at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/documents/no-time-to-wait-securing-the-future-from-drug-resistant-infections-en.pdf?sfvrsn=5b424d7_6

31

International Union for Conservation of Nature (2018). The IUCN red list of threatened species version.2018. United Kingdom: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources.

32

JamilaN.KhairuddeanM.YeongK. K.OsmanH.MurugaiyahV. (2015). Cholinesterase inhibitory triterpenoids from the bark of Garcinia hombroniana. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 30, 133–139. 10.3109/14756366.2014.895720

33

JokhadzeM.EristaviL.KutchukhidzeJ.ChariotA.AngenotL.TitsM.et al (2007). In vitro cytotoxicity of some medicinal plants from Georgian Amaryllidaceae. Phytother Res. 21, 622–624. 10.1002/ptr.2130

34

KarimiE.MehrabanjoubaniP.Homayouni-TabriziM.AbdolzadehA.SoltaniM. (2018). Phytochemical evaluation, antioxidant properties and antibacterial activity of Iranian medicinal herb Galanthus transcaucasicus Fomin. J. Food Meas. Charact. 12, 433–440. 10.1007/s11694-017-9656-5

35

KayaG. I.SarıkayaB.OnurM. A.SomerN. U.ViladomatF.CodinaC.et al (2011). Antiprotozoal alkaloids from Galanthus trojanus. Phytochem. Lett. 4, 301–305. 10.1016/j.phytol.2011.05.008

36

KayaG. I.UzunK.BozkurtB.OnurM. A.SomerN. U.GlatzelD. K.et al (2017). Chemical characterization and biological activity of an endemic Amaryllidaceae species: Galanthus cilicicus. South Afr. J. Bot. 108, 256–260. 10.1016/j.sajb.2016.11.008

37

KeyaertsE.VijgenL.PannecouqueC.Van DammeE.PeumansW.EgberinkH.et al (2007). Plant lectins are potent inhibitors of coronaviruses by interfering with two targets in the viral replication cycle. Antivir. Res. 75, 179–187. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.03.003

38

KhalifaM.ShihataE.RefaatJ.KamelM. (2018). An overview on the chemical and biological aspects of lycorine alkaloid. J. Adv. Biomed. Pharm. Sci. 1, 41–49. 10.21608/jabps.2018.4088.1016

39

KhawK. Y.ChoiS. B.TanS. C.WahabH. A.ChanK. L.MurugaiyahV. (2014). Prenylated xanthones from mangosteen as promising cholinesterase inhibitors and their molecular docking studies. Phytomedicine21, 1303–1309. 10.1016/j.phymed.2014.06.017

40

KhawK. Y.ChongC. W.MurugaiyahV. (2020). LC-QTOF-MS analysis of xanthone content in different parts of Garcinia mangostana and its influence on cholinesterase inhibition. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 35, 1433–1441. 10.1080/14756366.2020.1786819

41

KostelníkA.PohankaM. (2018). Inhibition of acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase by a plant secondary metabolite boldine. BioMed. Res. Int. 2018, 9634349. 10.1155/2018/9634349

42

Lamoral-TheysD.AndolfiA.Van GoietsenovenG.CimminoA.Le CalvéB.WauthozN.et al (2009). Lycorine, the main phenanthridine Amaryllidaceae alkaloid, exhibits significant antitumor activity in cancer cells that display resistance to proapoptotic stimuli: an investigation of structure-activity relationship and mechanistic insight. J. Med. Chem. 52, 6244–6256. 10.1021/jm901031h

43

LeeM. R. (1999). The snowdrop (Galanthus nivalis): from Odysseus to Alzheimer. Proc. R. Coll. Physicians Edinb.29 (4), 349–352.

44

LiewS. Y.KhawK. Y.MurugaiyahV.LooiC. Y.WongY. L.MustafaM. R.et al (2015). Natural indole butyrylcholinesterase inhibitors from Nauclea officinalis. Phytomedicine22, 45–48. 10.1016/j.phymed.2014.11.003

45

LočárekM.NovákováJ.KloučekP.Hošt’álkováA.KokoškaL.GábrlováL.et al (2015). Antifungal and antibacterial activity of extracts and alkaloids of selected Amaryllidaceae species. Nat. Prod. Commun. 10, 1934578X1501000912. 10.1177/1934578X1501000912

46

LuoG.GaoS. J. (2020). Global health concerns stirred by emerging viral infections. J. Med. Virol. 92, 399–400. 10.1002/jmv.25683

47

MaelickeA.CobanT.StorchA.SchrattenholzA.PereiraE. F.AlbuquerqueE. X. (1997). Allosteric modulation of Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor ion channel activity by noncompetitive agonists. J. Recept. Signal Transduct. Res. 17, 11–28. 10.3109/10799899709036592

48

MashkovskyM. D.Kruglikova–LvovaR. P. (1951). On the pharmacology of the new alkaloid galantamine. Farmakol. Toxicol. 14, 27–30.

49

MesulamM. M.GeulaC. (1994). Butyrylcholinesterase reactivity differentiates the amyloid plaques of aging from those of dementia. Ann. Neurol. 36, 722–727. 10.1002/ana.410360506

50

NairJ. J.StadenJ. V. (2019). Antiplasmodial lycorane alkaloid principles of the plant family Amaryllidaceae. Planta Med. 85 (8), 637–647. 10.1055/a-0880-5414

51

OrhanI.ŞenerB. (2003). Bioactivity-directed fractionation of alkaloids from some Amaryllidaceae plants and their anticholinesterase activity. Chem. Nat. Compound39, 383–386. 10.1023/B:CONC.0000003421.65467.9c

52

OrhanI.ŞenerB. (2005). Sustainable use of various Amaryllidaceae plants against Alzeimer’s disease. 678, 59–64. 10.17660/ActaHortic.2005.678.7

53

PaskovD. (1959). Nivalin: pharmacology and clinical application. Pharmachim, 1.

54

PisoschiA. M.PopA.CómpeanuC.PredoiG. (2016). Antioxidant capacity determination in plants and plant-derived products: a review. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longevity2016, 9130976. 10.1155/2016/9130976

55

PlaitakisA.DuvoisinR. C. (1983). Homer’s moly identified as Galanthus nivalis L.: physiologic antidote to stramonium poisoning. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 6, 1–5. 10.1097/00002826-198303000-00001

56

ProskurninaN. F.AreshkninaL. Y. (1953). Alkaloids of Galanthus woronowi. II. Isolation of a new alkaloid. (In English). Chem. Abstr. 47, 6959c.

57

ResetárA.FreytagC.KalydiF.GondaS.M-HamvasM.AjtayK.et al (2017). Production and antioxidant capacity of tissue cultures from four Amaryllidaceae species. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 86, 10.5586/asbp.3525

58

RheeI. K.AppelsN.LuijendijkT.IrthH.VerpoorteR. (2003). Determining acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity in plant extracts using a fluorimetric flow assay. Phytochem. Anal. 14, 145–149. 10.1002/pca.695

59

RønstedN.ZubovD.Bruun-LundS.DavisA. (2013). Snowdrops falling slowly into place: an improved phylogeny for Galanthus (Amaryllidaceae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 69, 205–217. 10.1016/j.ympev.2013.05.019

60

SarikayaB. B.BerkovS.BastidaJ.KayaG. I.OnurM. A.SomerN. U. (2013). GC-MS investigation of Amaryllidaceae alkaloids in galanthus xvalentinei nothosubsp. subplicatus. Nat. Prod. Commun. 8, 327–328. 10.1177/1934578X1300800312https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1934578X1300800312

61

SemerdjievaI.SidjimovaB.Yankova-TsvetkovaE.KostovaM.ZheljazkovV. D. (2019). Study on Galanthus species in the Bulgarian flora. Heliyon. 5, e03021. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019

62

SharifzadehM.YousefbeykF.AminG.SormaghiM.AzadiB.SamadiN.et al (2010). Investigation on pharmacological and antimicrobial activities of Galanthus transcaucasicus Fomin growing in Iran. Planta Med. 76, P474. 10.1055/s-0030-1264772

63

SidjimovaB.BerkovS.PopovS.EvstatievaL. (2003). Galanthamine distribution in Bulgarian Galanthus spp. Pharmazie58, 935–936.

64

TanH. L.ChanK. G.PusparajahP.SaokaewS.DuangjaiA.LeeL. H.et al (2016). Anti-cancer properties of the naturally occurring aphrodisiacs: icariin and its derivatives. Front. Pharmacol. 7, 191. 10.3389/fphar.2016.00191

65

TanW. N.KhairuddeanM.WongK. C.KhawK. Y.VikneswaranM. (2014). New cholinesterase inhibitors from Garcinia atroviridis. Fitoterapia97, 261–267. 10.1016/j.fitote.2014.06.003

66

TayK. C.TanL. T.ChanC. K.HongS. L.ChanK. G.YapW. H.et al (2019). Formononetin: a review of its anticancer potentials and mechanisms. Front. Pharmacol. 10, 820. 10.3389/fphar.2019.00820

67

ToriizukaY.KinoshitaE.KogureN.KitajimaM.IshiyamaA.OtoguroK.et al (2008). New lycorine-type alkaloid from Lycoris traubii and evaluation of antitrypanosomal and antimalarial activities of lycorine derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 16, 10182–10189. 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.10.061

68

TurkerA.KoyluogluH. (2012). Biological activities of some endemic plants in Turkey. Rom. Biotechnol. Lett. 17 (1), 6949–6961.

69

Van DammeE. J. M.AllenA. K.PeumansW. J. (1987). Isolation and characterization of a lectin with exclusive specificity towards mannose from snowdrop (Galanthus nivalis) bulbs. Fed. Eur. Biochem. Soc. Lett. 215, 140–144. 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80129-1

70

VentolaC. L. (2015). The antibiotic resistance crisis: part 1: causes and threats. P T. 40, 277–283.

71

World Checklist of Selected Plant Families (2020). World checklist of galanthus. Kew.: Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens.

72

YangJ.LiM.ShenX.LiuS. (2013). Influenza A virus entry inhibitors targeting the hemagglutinin. Viruses5, 352–373. 10.3390/v5010352

Summary

Keywords

snowdrop, galanthus, bioactivities, galanthamine, lycorine

Citation

Kong CK, Low LE, Siew WS, Yap W-H, Khaw K-Y, Ming LC, Mocan A, Goh B-H and Goh PH (2021) Biological Activities of Snowdrop (Galanthus spp., Family Amaryllidaceae). Front. Pharmacol. 11:552453. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.552453

Received

16 April 2020

Accepted

17 December 2020

Published

19 February 2021

Volume

11 - 2020

Edited by

Lyndy Joy McGaw, University of Pretoria, South Africa

Reviewed by

Pinarosa Avato, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Italy

Tosin Abiola Olasehinde, University of Fort Hare, South Africa

Nehir Unver Somer, Ege University, Turkey

Updates

Copyright

© 2021 Kong, Low, Siew, Yap, Khaw, Ming, Mocan, Goh and Goh.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Poh Hui Goh, pohhui.goh@ubd.edu.bn

This article was submitted to Ethnopharmacology, a section of the journal Frontiers in Pharmacology

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.