Abstract

The increasing dissemination of multidrug resistant (MDR) bacterial infections endangers global public health. How to develop effective antibacterial agents against resistant bacteria is becoming one of the most urgent demands to solve the drug resistance crisis. Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) with multi-target antibacterial actions are emerging as an effective way to combat the antibacterial resistance. Based on the innovative concept of organic wholeness and syndrome differentiation, TCM use in antibacterial therapies is encouraging. Herein, advances on flavonoid compounds of heat-clearing Chinese medicine exhibit their potential for the therapy of resistant bacteria. In this review, we focus on the antibacterial modes of herbal flavonoids. Additionally, we overview the targets of flavonoid compounds and divide them into direct-acting antibacterial compounds (DACs) and host-acting antibacterial compounds (HACs) based on their modes of action. We also discuss the associated functional groups of flavonoid compounds and highlight recent pharmacological activities against diverse resistant bacteria to provide the candidate drugs for the clinical infection.

Introduction

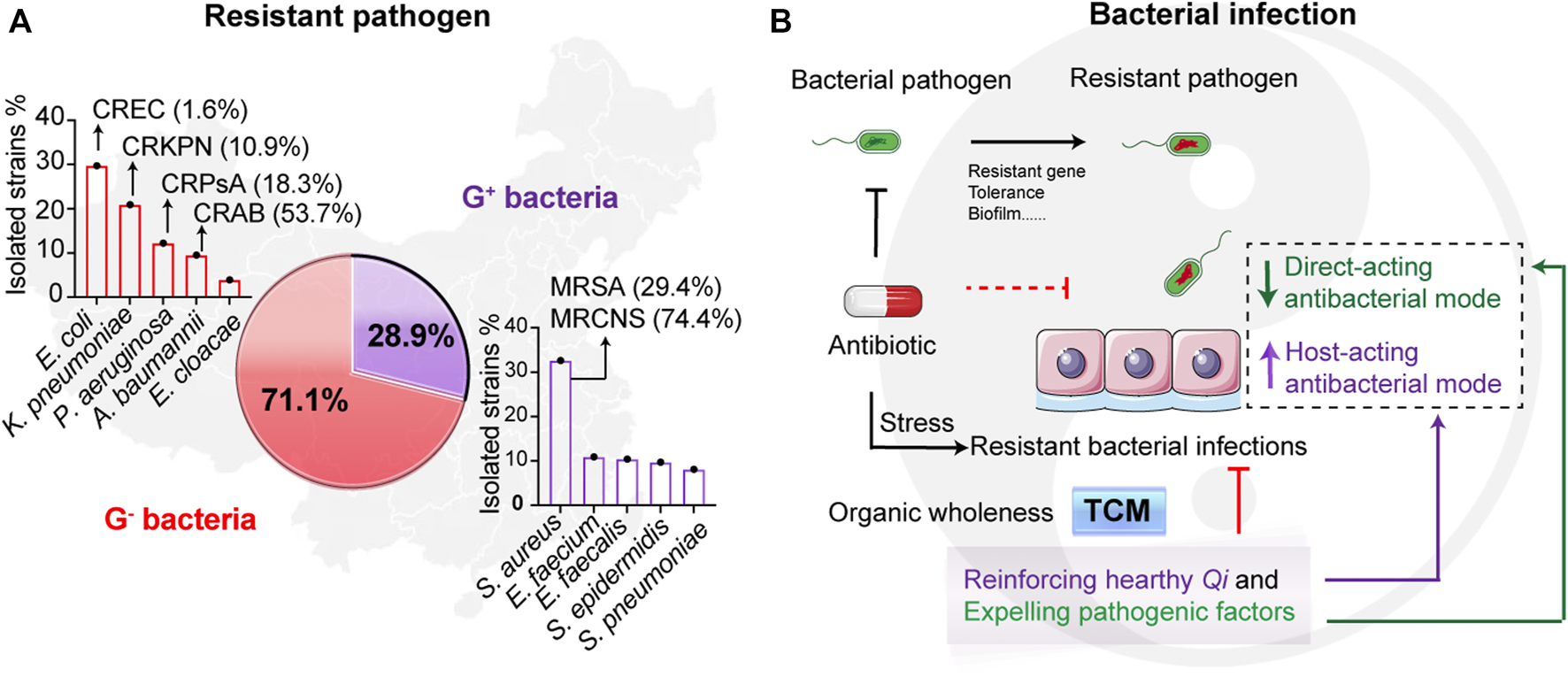

The worldwide spreading of pathogenic resistant bacteria threatens public health. Currently, the infections caused by Gram-negative (G−) bacteria occur more frequently than Gram-positive (G+) bacteria in clinics. A report from the China Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (CARSS)1 shows that G− bacteria accounted for 71.1% of the 3,249,123 clinical isolated strains, while Gram-positive (G+) bacteria for 28.9% (Figure 1A). Among them, the high number of multidrug resistant (MDR) bacterial infections, such as carbapenem-resistant G− bacteria (CRGNB), are life-threating (Bassetti et al., 2021; Palacios-Baena et al., 2021). As shown in Figure 1A, many more MDR pathogens are emerging, including the resistant G− bacteria like carbapenem-resistant E. coli (CREC, 1.6%), carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (CRKPN, 10.9%), carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa (CRPsA, 18.3%), carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii (CRAB, 53.7%), and the resistant G+ bacteria such as methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA, 29.4%) and methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative S. aureus (MRCNS, 74.4%). Worse still, global patient deaths due to antibiotic resistance are approximately 700, 000 and the numbers are expected to increase to 10 million by 2050 if no effective measures are introduced2. Therefore, alternative strategies to antibiotics and the discovery of novel antibacterial drugs to combat resistant bacteria are in high demand.

FIGURE 1

Resistant pathogenic infections and the treatment of traditional Chinese medicine. (A) The occurrence of resistant pathogens in China from 10/2019 to 12/2020. Reported data are collected from China Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (CARSS)1. The isolated resistant strains from the report that account for Gram-negative (G−) bacteria and Gram-positive (G+) bacteria are 71.1% and 28.9%, respectively. (B) Scheme of the infectious therapy of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). Resistant bacterial infections lead to the treatment failures of antibiotics. While therapeutic principles of TCM focus on the organic wholeness referring to “reinforcing healthy Qi and expelling pathogenic factors,” which displays that both suppressing bacteria and enhancing host defense. The TCM can divide to two types including direct-acting antibacterial mode and host-acting antibacterial mode. It is worth noting that “Qi” in TCM denoted the gas of host healthy, mostly meaning the forces of host defense.

In the resistant era, the major therapy of MDR still rely the efficacy and safety antibacterial agents, while the discovery and development of antibacterial drugs are barrier by the unknown infective route of pathogen (Liu et al., 2019; Song et al., 2020; Zulauf and Kirby, 2020). Effective antibacterial therapies need to explore more antibacterial compounds and their pharmacological activities and targets to sustainably combat the resistant bacteria (Theuretzbacher et al., 2020). Our previous work has demonstrated that the host defenses are critical for both bacterial infections and antibacterial drug therapy (Liu F. et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021). Therefore, host factors are vital for the management of MDR bacterial infections. In most situations, bacteria evolve or develop a variety of strategies to infect the human host (Culyba and Van Tyne, 2021). Thus, antibiotics cannot effectively fight against various bacterial mutations, while large doses and frequent usage of antibiotics can cause bacteria to be constantly exposed to drug stress, which will trigger the emergence of drug-resistant bacteria.

Unlike the direct stress of antibiotics to bacteria, host-directed therapy (HDT) is a sensible strategy against unknown resistant bacteria, and host-acting antibacterial compounds (HACs) are worthy of developing (Liu et al., 2022). The intrinsic advantages of HACs therapy are mobilizing the host cells to protect themselves from unknown infections with less emergence of resistant bacteria, due to the reduced selective pressure from directly targeting bacteria. Similar to HDT and HACs, the main therapeutic principle of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) against bacteria is dependent on “reinforcing healthy Qi and expelling pathogenic factors,” which also refers to its abilities of both enhancing host defense forces and eliminating pathogenic bacteria (Figure 1B). In terms of the TCM theory, we divide the antibacterial actions of TCM to direct-acting and host-acting antibacterial modes (Figure 1B). Upon infections, bacterial diseases belong to heat syndrome (Wang et al., 2018). Heat-clearing Chinese medicines symptomatically treat bacteria-caused internal heat syndrome. Therefore, the heat-clearing herbs may serve as potential drug libraries for screening the lead compounds to combat MDR bacterial infection. Flavonoids are abundant in plants, such as in most herbs, and recent research shows that flavonoids have excellent antibacterial activities that are regulated tightly with their functional groups (Song et al., 2021a).

Overall, this review focuses on the flavonoids from heat-clearing herbs to reveal the therapeutic strategies of resistant pathogens. In the following sections, we discuss the availabilities and antibacterial pipelines of herbal flavonoids.

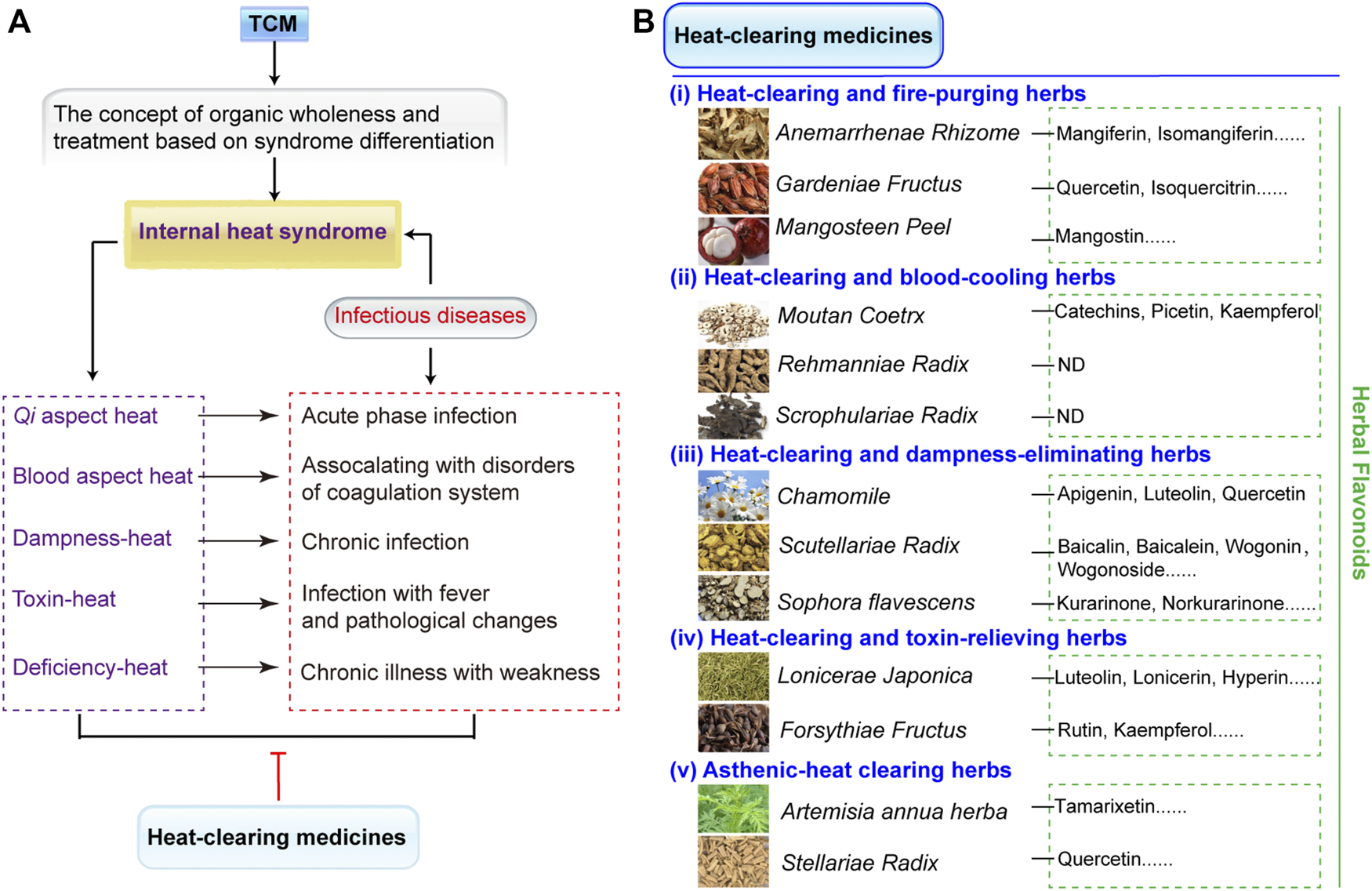

Herbal Flavonoids in Heat-Clearing Medicines

TCM is identified by organic wholeness and treatment based on syndrome differentiation. The syndrome differentiation of infectious diseases belongs to internal heat syndrome, which can be treated with heat-clearing medicines. Internal heat syndrome manifests itself in many forms including Qi aspect heat, blood aspect heat, dampness-heat, toxin-heat, and deficiency-heat (Figure 2A) (Chen, 1965). The heat syndrome occurs in the spatiotemporal axis of infectious diseases’ correspondence with acute phase, disorders of coagulation system, chronic infection, fever, pathological changes, and chronic illness with weakness (Figure 2A). For these heat syndromes, heat-clearing medicines have five of therapy: 1) heat-clearing and fire-purging herbs, 2) heat-clearing and blood-cooling herbs, 3) heat-clearing and damp-eliminating herbs, 4) heat-clearing and toxin-relieving herbs, and 5) asthenic-heat clearing herbs (Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2

Heat-clearing medicines and the distribution of its flavonoid compounds. (A) Heat-clearing medicines treat internal heat syndrome. TCM is identified by the concept of organic wholeness and treatment based on syndrome differentiation. The syndrome differentiation of infectious diseases belongs to internal heat syndrome, which can be treated with heat-clearing medicines. Internal heat syndrome contains Qi aspect heat, blood aspect heat, dampness-heat, toxin-heat, and deficiency-heat and occur during the spatiotemporal axis of infectious diseases, such as acute phase, disorders of coagulation system, chronic infection, fever, pathological changes, and chronic illness with weakness. (B) The classifications of heat-clearing medicines that combat different heat syndromes include (i) heat-clearing and fire-purging herbs, (ii) heat-clearing and blood-cooling herbs, (iii) heat-clearing and damp-eliminating herbs, (iv) heat-clearing and toxin-relieving herbs, and (v) asthenic-heat clearing herbs. In addition, the heat-clearing herbs that contain herbal flavonoids are listed. ND denotes no detected flavonoids in heat-clearing herbs. All the species list in the figure are fully validated3.

Flavonoids are widely distributed heat-clearing medicines and exhibit multiple biological activities such as antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidation effects (Lan et al., 2021; Waditzer and Bucar, 2021). The chemical structures of more than 8000 flavanoids have been determined (Wen et al., 2021) and most existing flavonoids have been reported to defend against MDR bacterial infections (Song et al., 2021a). As shown in Figure 2B, the typical heat-clearing and fire-purging herbs include Anemarrhenae Rhizome, Gardeniae Fructus, and Mangosteen peel. Mangiferin and isomangiferin are the main compounds from Anemarrhenae Rhizome (Piwowar et al., 2020), quercetin and isoquercitrin can be extracted from fruits of Gardeniae Fructus (Kim et al., 2006), and mangostin exsits in the Mangosteen peel (Weerayuth et al., 2014). Heat-clearing and blood-cooling herbs contain Moutan Coetrx, Rehmanniae Radix, and Scrophulariae Radix; among these, only Moutan Coetrx is reported to contain flavonoid compounds of catechins, picetin, and kaempferol (Zhang et al., 2017), while the others have no detected flavonoids. Three heat-clearing and damp-eliminating herbs with large flavonoids are apigenin, luteolin, andquercetin in Cancrinia discoidea (Su et al., 2011), baicalin, baicalein, wogonin, and wogonoside in Scutellariae Radix (Guowei et al., 2018), and kurarinone and norkurarinone in Sophora flavescens (Dong et al., 2021). Heat-clearing and toxin-relieving herbs such as Lonicerae Japonica and Forsythiae Fructus have luteolin, lonicerin, hyperin, and rutin (Huang et al., 2020; Wei et al., 2020). Finally, asthenic-heat clearing herbs include Artemisia annua herba and Stellariae Radix and these exist in tamarixetin and quercetin, correspondingly (Hao et al., 2020).

Antibacterial approaches and the main targets of the flavonoids are important for clinical applications. Within the decoding of active function, the classifications of flavonoids based on the chemical structures are intuitive, simple, and critical for understanding of antibacterial activates of flavonoids.

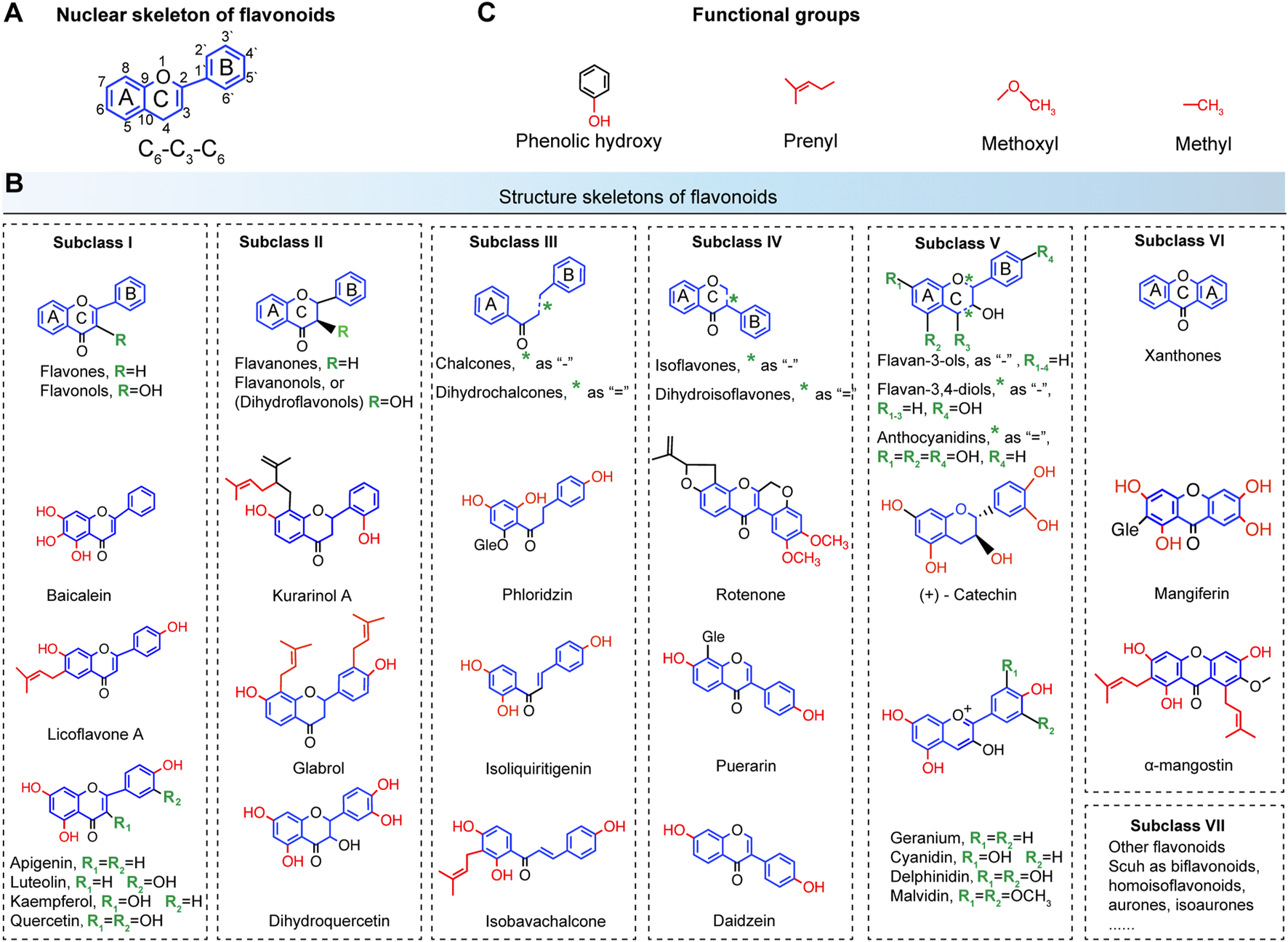

Chemical Structure Classification of Flavonoids

To assess the antibacterial activities of flavonoids, the chemical structures of flavonoid compounds need to be clarified. Thus, the structural classifications of herbal flavonoids are detailed in Figure 3. Generally, flavonoids refer to a series of compounds in which two benzene rings (A and B rings) with phenolic hydroxyl groups are connected to each other through the central three carbon atoms (Wen et al., 2021). As shown in Figure 3A, the nuclear skeleton of flavonoids forms the C6-C3-C6 system. This subsequently classifies the flavonoids according to the degree of oxidation of the central three carbon atoms, the linking position of the B ring, and whether the three carbon chains constitutes a ring (C ring) or not (Xie et al., 2015). Major subclasses of flavonoids are detailed in Figure 3B; subclass I includes flavones and flavonols, Subclass II includes flavanones and flavanonols, Subclass III includes chalcones and dihydrochalcones, Subclass IV includes isoflavones and dihydroisoflavones, Subclass V includes flavan-3-ols, flavan-3.4-diols, and anthocyanidins, and Subclass VI includes xathones and mangiferin, Subclass VII includes other flavonoids such as bioflavonoids, homoisoflavonoids, aurones, isoaurones, and so on. The common skeletons are marked by blue and the green R groups denote substitutable groups. Finally, the functional groups of flavonoids including prenyl, methoyl, and methyl (highlighted in red) decide the antibacterial activities (Figures 3B,C), resulting in various modes of action on resistant bacteria.

FIGURE 3

Chemical structure classifications of flavonoids. (A) The nuclear skeleton of flavonoids contains a 2-phenyl-chromone core with the C6-C3-C6 system. The A and B benzene rings connect to each other through the central three carbon atoms, which can or cannot form the C ring. (B) The major subclasses of flavonoids. Subclass I, flavones and flavonols; Subclass II, flavanones and flavanonols; Subclass III, chalcones and dihydrochalcones; Subclass IV, isoflavones and dihydroisoflavones; Subclass V, flavan-3-ols, flavan-3.4-diols and anthocyanidins; Subclass VI, xathones and mangiferin; Subclass VII, other flavonoids such as bioflavonoids, homoisoflavonoids, aurones, isoaurones, and so on. The common skeletons are marked by blue and the green R groups denote substitutable groups (C) The main functional groups of flavonoids include phenolic hydroxy, prenyl, methoxyl, and methyl (highlighted in red).

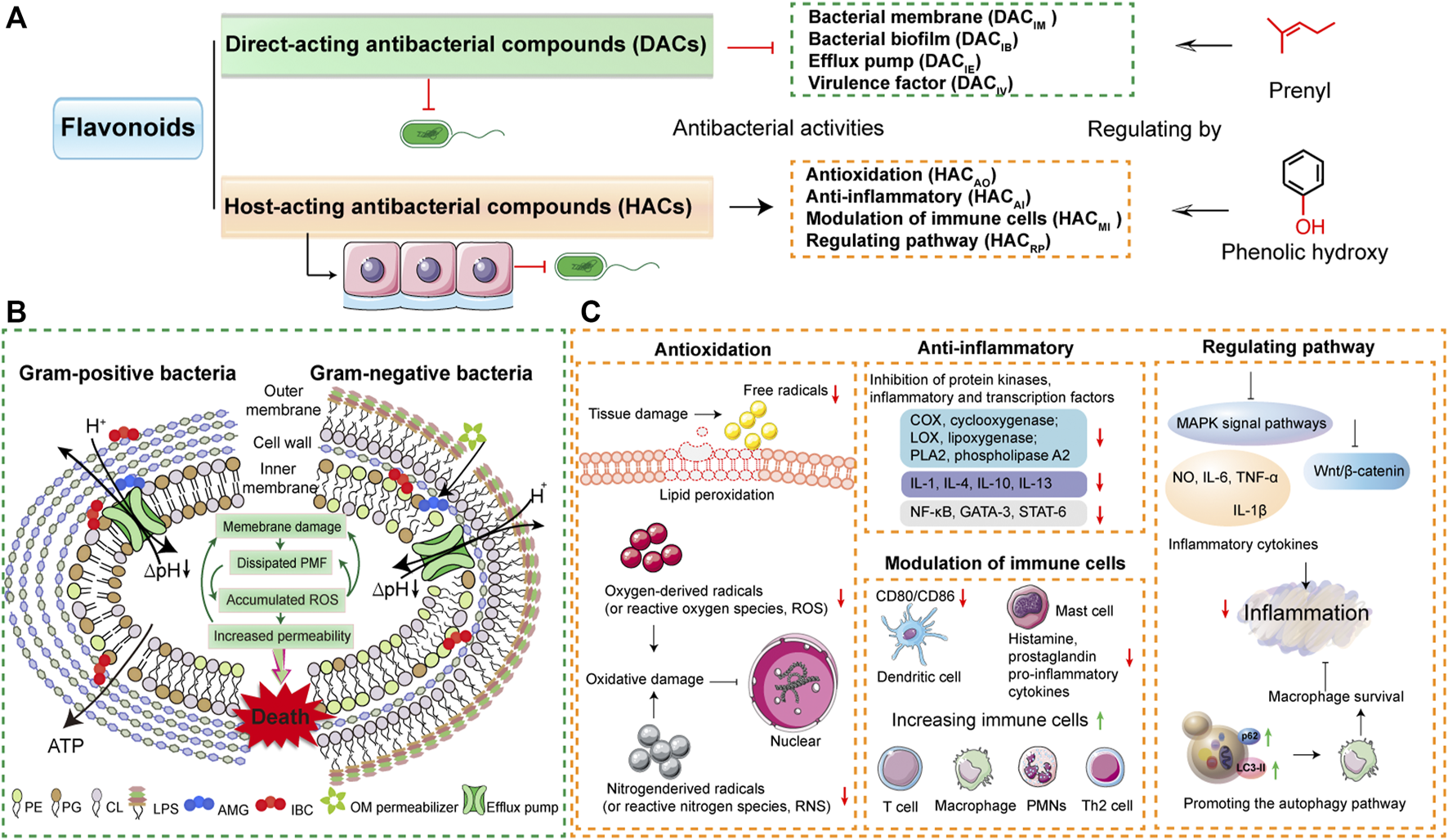

Modes of Action of Flavonoids on Resistant Bacteria

Antibacterial modes of flavonoids depend on the structures, that is the substitutions on the aromatic rings. As more antibacterial activities of natural flavonoids have been found, numerous flavonoids have been confirmed to have existing antibacterial activity-structure relationships. For instance, the flavonoid compounds that have prenyl groups with hydrophobic substituents inhibit bacterial membrane function and biofilm formation (Rashid et al., 2007; Prawat et al., 2013; Wenzel, 2013; Narendran et al., 2016). The flavonoid compounds that have phenolic hydroxy groups with scavenging oxygen free radicals can modulate antioxidation and anti-inflammatory activities (Wenzel, 2013; Guowei et al., 2018; Farhadi et al., 2019; Jordan et al., 2020).

According to different modes of action, flavonoid compounds can be grouped into two types, one with a direct-acting antibacterial mode (DAC) regulated by prenyl (Dong et al., 2017; Kariu et al., 2017; Jordan et al., 2020; Song et al., 2021a), the other with host-acting antibacterial mode (HAC) regulated by phenolic hydroxy (Xie et al., 2015; Echeverria et al., 2017; Farhadi et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2022).

For a clearer understanding of the two modes, the related three subcategories are attributed to these two modes. According to the antibacterial activities of inhibition of bacterial membrane, bacterial biofilm, efflux pump, and virulence factor, DAC divides to DACIM, DACIB, DACIE, and DACIV, respectively. HAC is divided into HACAO, HACAI, HACMI, and HACRP based on the effects on the antioxidation, anti-inflammatory, modulation of immune cells, and regulating pathway of host (Figure 4A and Table 1). Furthermore, the specific modes of action on herbal flavonoids that combat resistant bacteria are illustrated in the following.

FIGURE 4

Modes of action of flavonoids on resistant pathogens. (A) The flavonoids are divided into two types of compounds based on the antibacterial modes. One is the direct-acting antibacterial flavonoid compounds (DACs) that damage the bacterial membrane and inhibit bacterial biofilm, bacterial efflux pump, or virulence factor. The other refers to host-acting antibacterial flavonoid compounds (HACs) that target anti-inflammatory, antioxidation modulation of immune cells, or regulate cellular pathway. The antibacterial activities of DACs and HACs are regulated by prenyl, phenolic hydroxy, or methyl. (B) The mechanisms of flavonoid DAC (isobavachalcone, AMG and α-mangostin, IBC) inhibit bacterial membrane (Song et al., 2021a). The copyright was obtained from Wiley-VCH GmbH in their journal of Advanced Science with the terms of the https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/license. (C) The molecular mechanisms of flavonoid HACs have the antibacterial actions of antioxidation, anti-inflammatory, modulation of immune cells, and regulating cellular pathway.

TABLE 1

| Flavonoids | Flavonoid structures | Sources | Antibacterial modes (DACIM/IE/IV/IB/HACAO/AI/MI/RP) | Target | Bacteria | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavonoids | Prenylated flavonoids | Epimedium species | DACIV/IB | Bacterial biofilm formation | Porphyromonas gingivalis | Kariu et al. (2017) |

| Flavonoids | Sophora flavescensa | HACAI/RP | Autophagy protein LC3II and p62 | Tuberculosis (TB) | Kan et al. (2020) | |

| Flavones | Apigenin | Cancrinia discoideaa | DACIE; HACAI/AO | Inhibition of EtBr efflux pump | Staphylococcus aureus | (Brown et al., 2015; Tang et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2019; Ciumarnean et al., 2020) |

| Flavonols | Baicalein, Baicalin | Scutellariae Radixa | DACIM/IE/IV/IB; HACAI/AO | Bacterial biofilm formation | MRSA; S. aureus; Streptococcus suis; Helicobacter pylori; Pseudomonas aeruginosa | (Rajkumari et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020; Lu et al., 2021; Palierse et al., 2021; Xiao et al., 2021) |

| Baicalein-7-O-β-D-glucuronide | Scutellariae Radixa | HACAI/AO/RP | Regulating Wnt/β-catenin and MAPK signal pathways | Bacteria | (Li et al., 2009; Kawai, 2018) | |

| Quercetin, Isoquercitrin | Gardeniae Fructusb; Stellariae Radixc | DACIM/IE/IV; HACAO | CRGNB; S. aureus; CRPsA; CRAB | (Lee et al., 2017; Mohamed et al., 2020; Pal and Tripathi, 2020; Yang et al., 2020) | ||

| Kaempferol | Moutan Coetrxd | DACIM/IV | MRSA, S. aureus | (Aparna et al., 2014; Lin et al., 2020; He et al., 2021) | ||

| Luteolin, Lonicerin | Lonicerae Japonicae | DACIM/IE/IV/IB; HACAI/MI/ | Reducing the extracellular matrix to inhibit microcolony biofilms; MsrA efflux pump | Escherichia coli; Klebsiella pneumoniae; MRSA; Trueperella pyogenes; Mycobacterium tuberculosis | (Zhang et al., 2018; Pruteanu et al., 2020; Miao et al., 2021; Singh et al., 2021; Guo et al., 2022) | |

| Luteolin-7-O-β-D-glucuronide | Impatiens balsamina | HACAI/RP | MAPKs pathway | G− Bacteria | (Liu et al., 2020; Pereita et al., 2020) | |

| Tamarixetin | Artemisia annua herbac | DACIV; HACAI | Escherichia coli K1 | Park et al. (2018) | ||

| Wogonin | Scutellariae Radixa | DACIE/IV | Inhibition of EtBr efflux pump | S. aureus, Mycobacterium aurum and Mycobacterium smegmatis | Solnier et al. (2020) | |

| Flavanones | Glabrol | Liquorice (n.a.) | DACIM | LPS | MRSA | Kalli et al. (2021) |

| Flavanonols | Hyperin, Hyperoside | Lonicerae Japonicae; Anadenanthera colubrina var cebil (n.a.) | HACAO | Antioxidant potentials | S. aureus | Rodrigo Cavalcante de Araújo et al. (2019) |

| Kurarinol A, Kurarinone | Sophora flavescensa | HACMI/AI | Regulation of macrophage functions | Gram-negative bacteria | Xu et al. (2021) | |

| Rutin | Forsthiae Fructusa | DACIB/IV; HACAO | Bacterial biofilm, atioxidant potentials, inflammatory cytokine expressions | P. aeruginosa; S. aureus; Multidrug-resistant Gram-positive pathogens; Drug resistant Aeromonas hydrophila | (Deepika et al., 2019; Di Lodovico et al., 2020; Motallebi et al., 2020; Suebsaard and Charerntantanakul, 2021) | |

| Chalcones | Phloridzin | Apples, tea (n.a.) | DACIB; HACAI | Efflux protein genes Biofilm formation | S. aureus (msrA and norA efflux protein); Gram-negative bacteria | (Lopes et al., 2017; Kamdi et al., 2021) |

| Dihydrochalcones | Isoliquirtigenin | Liquorice (n.a.) | DACIM; HACAI | Bacterial cytoplasmic membrane function, Tissue inflammation | MRSA | (Gaur et al., 2016; Watanabe et al., 2016) |

| Isobavachalcone | Psoralea corylifolia (n.a.) | DACIE | AcrAB, TolC efflux pumps | MDR-Gram-negative bacteria; MRSA; Bacteria | (Kuete et al., 2010; Song et al., 2021a) | |

| Isoflavones | Rotenone | Derris (n.a.) | - | - | - | - |

| Dihydroisoflavones | Puerarin | Pueraria Lobata (n.a.) | HACAI | Anti-inflammation by protecting the epithelia and goblet cells and increasing the short-chain fatty acids level | Pathogenic bacteria | (Wu et al., 2020; Song et al., 2021a) |

| Daidzein | n.a. | DACIE | Efflux pump assemblies and AcrB and MexB proteins | E. coli (AcrB efflux pump); P. aeruginosa (MexB efflux pump) | Aparna et al. (2014) | |

| Flavan-3-OLS Flavan-3,4-Diols | Catechin | Moutan Coetrxd; Hyperforin perforatume; Ginkgo Biloba, tea (n.a.) | DACIM/IV; HACAI | Inhibition of bacterial membrane and bacterial virulence factors, anti-inflammation | Resistant bacteria | (Gomes et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2018; Siebert et al., 2021; Wu and Brown, 2021) |

| Anthocyanidins | Cyanidin, Delphinidin, Geranium, Malvidin | Angiosperm (n.a.) | - | - | - | - |

| Xanthones | Mangiferin | Anemarrhenae Rhizomeb | DACIE | Efflux pumps | Gram-negative MDR bacteria. | Tchinda et al. (2019) |

| α-mangostin | Mangosteen peelb | DACIM | PG of bacterial membrane function | Bacteria | Song et al. (2021a) |

Antibacterial modes of natural plant flavonoids and the main target bacteria.

Note: Heat-clearing Chinese herbs include.

Heat-clearing and damp-eliminating herbs.

Heat-clearing and fire-purging herbs.

Asthenic-heat clearing herbs.

Heat-clearing and blood-cooling herbs.

Heat-clearing and toxin-relieving herbs.

n.a., not applicable. DAC represents direct antibacterial flavonoid compound, DACIM, DAC that inhibition of bacterial membrane, DACIE, DAC that inhibition of bacterial efflux pump, DACIV, DAC that inhibition of bacterial virulence factor, DACIB, DAC that inhibition of bacterial biofilm; HAC denotes host-acting antibacterial flavonoid compound, HACAI, anti-inflammatory of HAC; HACMI, HAC that modulation of immune cells, HACAO, antioxidation of HAC, HACRP, HAC that regulate signaling pathways; MDR, multidrug-resistant; MRSA, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; CRGNB, carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria; CRPsA, carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa; CRAB, carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii; “-” denotes that not report the antibacterial activity. All the species listed in the table are fully validated3.

Direct-Acting Antibacterial Modes

Direct-acting antibacterial modes of herbal flavonoids means that the antibacterial agents directly target the bacterial themselves, such as the bacterial membrane functions, biofilm formation, efflux pumps, and virulence factors (Figure 4A). Of the activities of DAC flavonoids, the first category is the biophysical barrier of the bacterial inner membrane that directly increases bacteria survival (Martin et al., 2020). Similar to most antibacterial drugs, the main therapeutic treatment option of flavonoids is damaging bacterial membrane functions. A recent report shows that the antibacterial mechanisms of flavonoids rely on distinctive modes of action to bind the phospholipids of bacterial membrane, which result in the disruption of proton motive force and metabolic disturbance (Song et al., 2021a). DAC flavonoids such as isobavachalcone (AMG) and α-mangostin (IBC) target the phosphatidylglycerol (PG) of bacterial membrane (Figure 4B). These two DAC flavonoids have 3′-prenyl and 2, 8-prenyl, respectively (Figure 3B). Active prenyl flavonoids endow the antibacterial activities that combat most bacteria, even MRSA (Table 1). In addition, the prenyl flavonoid compounds are abundantly distributed in herbal flavonoids (Wen et al., 2021). For instance, as typical heat-clearing and damp eliminating herbs, Scutellariae Radix has the main flavonoes of baicalein and baicalin using the direct-acting antibacterial activity to fight against MRSA, S. aureus, and Streptococcus suis infections via inhibition of bacterial membrane functions (Rajkumari et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2020; Lu et al., 2021) (Table 1). In addition, other flavonoid compounds in heat-clearing herbs also have the antibacterial abilities of damaging the bacterial membrane, such as quercetin from Gardeniae Fructus (iii, heat-clearing and damp eliminating herb) (Mohamed et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2020), kaempferol origin from Moutan Coetrx (ii, heat-clearing and blood-eliminating herb) (Lin et al., 2020; He et al., 2021), luteolin and lonicerin from Lonicerae Japonica (iv, heat-clearing and toxin-relieving herb) (Zhang et al., 2018; Singh et al., 2021), hyperin and hyperoside origin from Lonicerae Japonica (iv, heat-clearing and toxin-relieving herb) (Rodrigo Cavalcante de Araújo et al., 2019), rutin from Forshiae Fructus (iii, heat-clearing and damp eliminating herb) (Deepika et al., 2019; Di Lodovico et al., 2020; Motallebi et al., 2020), and mangiferin from Anemarrhenae Rhizome (i, heat-clearing and blood-cooling herbs) (Tchinda et al., 2019). These DACIM flavonoids that treat bacterial strains are detailed in Table 1.

In order to gain more survival options from the antibiotic stress, resistant bacteria evolved various approaches to survive, such as biofilm, efflux pumps, and virulence factors (Blair et al., 2015; Narendran et al., 2016; Ercoli et al., 2018; Yelin and Kishony, 2018). Flavonoids limited the spread of resistant bacteria by serving as the inhibitors of bacterial efflux pumps (Solnier et al., 2020) and bacterial virulence factors (Wang et al., 2020). We summarized the effect of flavonoids such as DACIB, DACIE, and DACIV in Table 1. For the DACIB mode, flavonoids directly target the bacterial biofilm formation as therapeutic strategies. For instance, the baicalein-fabricated gold nanoparticles have antibiofilm activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 (Rajkumari et al., 2017). The flavone luteolin and the flavonols myricetin, morin, and quercetin strongly reduce the extracellular matrix to interrupt the Escherichia coli macrocolony biofilms by directly inhibiting the assembly of amyloid curli fibers by driving CsgA subunits into an off-pathway leading to SDS-insoluble oligomers (Pruteanu et al., 2020). With flavonoid DACIE, apigenin can recover the susceptibility of antibiotics to resistant bacteria by suppressing the EtBr efflux pump (Brown et al., 2015; Tang et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2019; Ciumarnean et al., 2020). Additionally, wogonin can suppress the EtBr efflux pumps of S. aureus, Mycobacterium aurum, and Mycobacterium smegmatis (Solnier et al., 2020). Luteolin inhibits MsrA efflux pump in Trueperella pyogenes (Guo et al., 2022), phloridzin inhibits the msrA and norA efflux proteins of S. aureus (Lopes et al., 2017; Kamdi et al., 2021), isobavachalcone inhibits AcrAB, TolC efflux pumps of G− bacteria (Kuete et al., 2010), and daidzein inhibits AcrB efflux pump of E. coli (Aparna et al., 2014). It is worth noting that quercetin that belongs to flavanols have the inhibitory potential to effectively act as the efflux pump to treat CRNB due to its polyphenol hydroxyl group structure (Pal and Tripathi, 2020). On the other side, flavonoid compounds have the direct-acting antibacterial effect of inhibiting bacterial virulence factors, such as α-hemolysin (Hla) of S. aureus (Wang et al., 2020; He et al., 2021). The Hla can cause bacterial entry of host cells and also lead to bacterial coinfection, while flavonoids can target Hla to control bacterial infection (He et al., 2021). Altogether, the flavonoid compounds that inhibit virulence factors are denoted as DACIV flavonoids and summarized in Table 1.

Host-Acting Antibacterial Modest

To establish persistent infection in the host, resistant bacteria toned to interrupt the host defense and trigger inflammation (Ercoli et al., 2018; Mathur et al., 2019; Pham et al., 2020; Rowe et al., 2020). The host is the key point to drug therapy and HDT may be a novel approach for controlling resistant bacteria (Kaufmann et al., 2018; Ahmed et al., 2020). Many natural plant compounds exhibited the antibacterial activity of HDT, such as the bacterial infection therapy obtained from bedaquiline from Perucian bark that activates host innate immunity (Giraud-Gatineau et al., 2020). Additionally, the host-acting antibacterial compounds were systematically summarized in our previous works (Liu et al., 2022). Based on these foundations, as shown in Figure 4C, we divide HAC flavonoids into four groups: antioxidation (HACAO), anti-inflammatory (HACAI), modulation of immune cells (HACMI), and regulating cellular pathways (HACRP).

HACAO flavonoids are able to combat bacterial infection with their antioxidation function, by reducing the free radicals and lipid peroxidation to inhibit oxygen-derived radicals or nitrogen-derived radicals to avoid oxidative damage (Kamdi et al., 2021; Palierse et al., 2021) In addition, this antibacterial activity mainly relies on the phenolic hydroxy group of flavonoid compounds, such as quercetin and hyperoside (Figures 3C, 4A) (Xie et al., 2015). For the HACAI flavonoids, the major anti-inflammatory modes of flavonoid compounds are inhibition of protein kinases (COX, cyclooxygenase, LOX, lipoxygenase and PLA2, phospholipase A2), inflammatory factors (IL-1, IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13) and related transcription factors (NF-κB, GATA-3, and STAT-6) (Park et al., 2018; Ren et al., 2019; Kamdi et al., 2021; Miao et al., 2021). The anti-inflammatory flavonoid compounds include apigenin, baicalein, baicalin, luteolin, lonicerin, tamarixetin, rutin, phloridzin, isoliguirtigentin, puerarin, and catechin (Table 1). The HACMI flavonoids are marked as modulation of immune cells, which is usually accompanied by anti-inflammatory effects, like luteolin and kurarinol A (Singh et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2021). These functions of activating immune cells to downregulate inflammation contains decreasing CD80/CD86 of dendritic cells and histamine, prostaglandin, pro-inflammatory, and cytokines of mast cells to suppress excessive inflammation. In addition, it also increases immune cells (T cell, macrophage, PMNs and Th2 cell) to activate innate immunity (Figure 4C). The HACRP flavonoids are the kinds of compounds that target cellular signaling pathways to combat bacteria. As shown in Table 1 and Figure 4C, the flavonoids of Sophora flavescens are potential agents in Tuberculosis (TB) infection therapy by enhancing macrophage autophagy to promote cellular survival and then reducing inflammation. (Kan et al., 2020). The Baicalein-7-O-β-D-glucuronide of Scutellariae Radi and Luteolin-7-O-β-D-glucuronide of Impatiens balsamina target MAPKs or Wnt/β-catenin pathway to inhibit the inflammation from bacterial LPS (Li et al., 2009; Kawai, 2018; Liu F. et al., 2020; Pereira et al., 2020).

Conclusion

The antibacterial resistance crisis has led to a prolonged period of infection control in clinics. High-efficiency and novel antimicrobial drugs remain the most effective strategies for the treatment of multidrug-resistant and unknown pathogen infections (Brown and Wright, 2016; Theuretzbacher et al., 2020). It is clear that the main measures for the prevention and control of drug-resistant bacteria are to vigorously develop green and effective new antibacterial drugs and restore existing antibacterial drugs safely and stably. However, unclear mechanisms of antibacterial action is the main reason that hinders the development of drugs. Therefore, target identification of herbal products is necessary. In this review, we summarized both the direct-acting and host-acting antibacterial flavonoids derived from heat-clearing herbs and focused on the antibacterial modes. The current reports show the antibacterial effects of flavonoid compounds on MDR bacteria by both the direct-acting antibacterial mode and host-acting antibacterial mode (Table 1). It also proves that herbal flavonoids should be the better source for alternative antibiotics (Figure 1B and Figure 4). However, the focus on the discovery of antibacterial targets of flavonoids are the main topic in this review. In addition, the screening principles of lead flavonoids based on the antibacterial targets need more illustration. Hence, further studies ought to devote more attention to the multi-targets of flavonoids. Thus, we believe the crisis in antibiotic discovery will rapidly be solved though exploring more herbs in future. Altogether, the basis of this review aims to find the flavonoid lead compounds to guide the future drug modifications based on the structure and active antibacterial mechanism based on functional groups.

Statements

Author contributions

XL conceived the projects. XL, LS, and XH prepared the figures and table. JL and XR performed data collection. XL, LS, and XH wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by “Beijing Natural Science Foundation, grant number 6224060”, “2021 youth project of high-end technology innovation think tank, grant number 2021ZZZLFZB1207120”, “2022 Research and Innovation ability improvement plan for young teachers of Beijing University of Agriculture, grant number QJKC2022028” and “Beijing University of Agriculture science and Technology innovation Sparkling support plan, grant number, BUA-HHXD2022007”.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Kui Zhu from China Agricultural University for his kind help with this review.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

AhmedS.RaqibR.GuðmundssonG. H.BergmanP.AgerberthB.RekhaR. S. (2020). Host-directed Therapy as a Novel Treatment Strategy to Overcome Tuberculosis: Targeting Immune Modulation. Antibiot. (Basel)9, 21. 10.3390/antibiotics9010021PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2

AparnaV.DineshkumarK.MohanalakshmiN.VelmuruganD.HopperW. (2014). Identification of Natural Compound Inhibitors for Multidrug Efflux Pumps of Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa Using In Silico High-Throughput Virtual Screening and In Vitro Validation. PLoS One9, e101840. 10.1371/journal.pone.0101840PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

3

BassettiM.EcholsR.MatsunagaY.AriyasuM.DoiY.FerrerR.et al (2021). Efficacy and Safety of Cefiderocol or Best Available Therapy for the Treatment of Serious Infections Caused by Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria (CREDIBLE-CR): a Randomised, Open-Label, Multicentre, Pathogen-Focused, Descriptive, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Infect. Dis.21, 226–240. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30796-9PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

4

BlairJ. M.WebberM. A.BaylayA. J.OgboluD. O.PiddockL. J. (2015). Molecular Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.13, 42–51. 10.1038/nrmicro3380PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

5

BrownA. R.EttefaghK. A.ToddD.ColeP. S.EganJ. M.FoilD. H.et al (2015). A Mass Spectrometry-Based Assay for Improved Quantitative Measurements of Efflux Pump Inhibition. PLoS One10, e0124814. 10.1371/journal.pone.0124814PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

6

BrownE. D.WrightG. D. (2016). Antibacterial Drug Discovery in the Resistance Era. Nature529, 336–343. 10.1038/nature17042PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

7

ChenK. K. (1965). PHARMACOLOGY of Chinese MATERIA MEDICA - ScienceDirect. Pharmacol. Orient. Plants, 47–50. 10.1016/b978-0-08-010809-4.50009-6CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

8

ChenM. E.SuC. H.YangJ. S.LuC. C.HouY. C.WuJ. B.et al (2018). Baicalin, Baicalein, and Lactobacillus Rhamnosus JB3 Alleviated Helicobacter pylori Infections In Vitro and In Vivo. J. Food Sci.83, 3118–3125. 10.1111/1750-3841.14372PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

9

CiumărneanL.MilaciuM. V.RuncanO.VesaȘ. C.RăchișanA. L.NegreanV.et al (2020). The Effects of Flavonoids in Cardiovascular Diseases. Molecules25, 4320. 10.3390/molecules25184320CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

10

CulybaM. J.Van TyneD. (2021). Bacterial evolution during human infection: adapt and live or adapt and die. PLoS Pathog.17, e1009872. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009872PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

11

DeepikaM. S.ThangamR.VijayakumarT. S.SasirekhaR.VimalaR. T. V.SivasubramanianS.et al (2019). Antibacterial Synergy between Rutin and Florfenicol Enhances Therapeutic Spectrum against Drug Resistant Aeromonas Hydrophila. Microb. Pathog.135, 103612. 10.1016/j.micpath.2019.103612PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

12

Di LodovicoS.MenghiniL.FerranteC.RecchiaE.Castro-AmorimJ.GameiroP.et al (2020). Hop Extract: An Efficacious Antimicrobial and Anti-biofilm Agent against Multidrug-Resistant Staphylococci Strains and Cutibacterium Acnes. Front. Microbiol.11, 1852. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01852PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

13

DongY.JiaG.HuJ.LiuH.WuT.YangS.et al (2021). Determination of Alkaloids and Flavonoids in sophora Flavescens by UHPLC-Q-TOF/MS. J. Anal. Methods Chem.2021, 9915027–9915113. 10.1155/2021/9915027PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

14

EcheverríaJ.OpazoJ.MendozaL.UrzúaA.WilkensM. (2017). Structure-Activity and Lipophilicity Relationships of Selected Antibacterial Natural Flavones and Flavanones of Chilean Flora. Molecules22, 608–623. 10.3390/molecules22040608CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

15

ErcoliG.FernandesV. E.ChungW. Y.WanfordJ. J.ThomsonS.BaylissC. D.et al (2018). Intracellular Replication of Streptococcus Pneumoniae inside Splenic Macrophages Serves as a Reservoir for Septicaemia. Nat. Microbiol.3, 600–610. 10.1038/s41564-018-0147-1PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

16

FarhadiF.KhamenehB.IranshahiM.IranshahyM. (2019). Antibacterial Activity of Flavonoids and Their Structure-Activity Relationship: An Update Review. Phytother. Res.33, 13–40. 10.1002/ptr.6208PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

17

GomesF. M. S.Da Cunha XavierJ.Dos SantosJ. F. S.De MatosY.TintinoS. R.De FreitasT. S.et al (2018). Evaluation of Antibacterial and Modifying Action of Catechin Antibiotics in Resistant Strains. Microb. Pathog.115, 175–178. 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.12.058PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

18

Giraud-GatineauA.CoyaJ. M.MaureA.BitonA.ThomsonM.BernardE. M.et al (2020). The Antibiotic Bedaquiline Activates Host Macrophage Innate Immune Resistance to Bacterial Infection. Elife9, e55692. 10.7554/eLife.55692PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

19

GuoweiG.HuaiyouW.XiangpengK.RanD.Tina (2018). Flavonoids Are Identified from the Extract of Scutellariae Radix to Suppress Inflammatory-Induced Angiogenic Responses in Cultured RAW 264.7 Macrophages. Sci. Rep.8, 17412. 10.1038/s41598-018-35817-2PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

20

GuoY.HuangC.SuH.ZhangZ.ChenM.WangR.et al (2022). Luteolin Increases Susceptibility to Macrolides by Inhibiting MsrA Efflux Pump in Trueperella Pyogenes. Vet. Res.53, 3. 10.1186/s13567-021-01021-wPubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

21

HaoC.ChenL.DongH.XingW.XueF.ChengY. (2020). Extraction of Flavonoids from Scutellariae Radix Using Ultrasound-Assisted Deep Eutectic Solvents and Evaluation of Their Anti-inflammatory Activities. ACS Omega5, 23140–23147. 10.1021/acsomega.0c02898PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

22

HeS.DengQ.LiangB.YuF.YuX.GuoD.et al (2021). Suppressing Alpha-Hemolysin as Potential Target to Screen of Flavonoids to Combat Bacterial Coinfection. Molecules26, 7577. 10.3390/molecules26247577PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

23

HuangY.XiumeiM. A.ZengC.CaiX.JieH. E.FengX.et al (2020). Extraction Process and Content Determination of Total Flavonoids in Lonicera japonica. Med. Plant11, 4. Google Scholar

24

JordanP. M.GerstmeierJ.PaceS.BilanciaR.RaoZ.BörnerF.et al (2020). Staphylococcus Aureus-Derived α-Hemolysin Evokes Generation of Specialized Pro-resolving Mediators Promoting Inflammation Resolution. Cell Rep.33, 108247. 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108247PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

25

KalliS.Araya-CloutierC.HagemanJ.VinckenJ. P. (2021). Insights into the Molecular Properties Underlying Antibacterial Activity of Prenylated (iso)flavonoids Against MRSA. Sci. Rep.11, 14180. 10.1038/s41598-021-92964-9PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

26

KamdiS. P.RavalA.NakhateK. T. (2021). Phloridzin Attenuates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Cognitive Impairment via Antioxidant, Anti-inflammatory and Neuromodulatory Activities. Cytokine139, 155408. 10.1016/j.cyto.2020.155408PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

27

KanL. L.LiuD.ChanB. C.TsangM. S.HouT.LeungP. C.et al (2020). The Flavonoids of Sophora Flavescens Exerts Anti-inflammatory Activity via Promoting Autophagy of Bacillus Calmette-Guérin-Stimulated Macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol.108, 1615–1629. 10.1002/JLB.3MA0720-682RRPubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

28

KariuT.NakaoR.IkedaT.NakashimaK.PotempaJ.ImamuraT. (2017). Inhibition of Gingipains and Porphyromonas Gingivalis Growth and Biofilm Formation by Prenyl Flavonoids. J. Periodontal Res.52 (1), 89–96. 10.1111/jre.12372PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

29

KaufmannS. H. E.DorhoiA.HotchkissR. S.BartenschlagerR. (2018). Host-directed Therapies for Bacterial and Viral Infections. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov.17, 35–56. 10.1111/jre.12372PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

30

KawaiY. (2018). Understanding Metabolic Conversions and Molecular Actions of Flavonoids in Vivo:toward New Strategies for Effective Utilization of Natural Polyphenols in Human health. J. Med. Invest.65, 162–165. 10.2152/jmi.65.162PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

31

KimH. J.KimE. J.SeoS. H.ShinC. G.JinC.LeeY. S. (2006). Vanillic Acid Glycoside and Quinic Acid Derivatives from Gardeniae Fructus. J. Nat. Prod.69, 600–603. 10.1021/np050447rPubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

32

KueteV.NgameniB.TangmouoJ. G.BollaJ. M.Alibert-FrancoS.NgadjuiB. T.et al (2010). Efflux Pumps Are Involved in the Defense of Gram-Negative Bacteria against the Natural Products Isobavachalcone and Diospyrone. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.54, 1749–1752. 10.1128/AAC.01533-09PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

33

LanJ.-E.LiX.-J.ZhuX.-F.SunZ.-L.HeJ.-M.ZlohM.et al (2021). Flavonoids from Artemisia Rupestris and Their Synergistic Antibacterial Effects on Drug-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Nat. Prod. Res.35, 1881–1886. 10.1080/14786419.2019.1639182PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

34

LiC.ZhouL.LinG.ZuoZ. (2009). Contents of Major Bioactive Flavones in Proprietary Traditional Chinese Medicine Products and Reference Herb of Radix Scutellariae. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal.50, 298–306. 10.1016/j.jpba.2009.04.028PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

35

LeeY. S.WooJ. B.RyuS. I.MoonS. K.HanN. S.LeeS. B. I. (2017). Glucosylation of Flavonol and Flavanones by Bacillus cyclodextrin Glucosyltransferase to Enhance Their Solubility and Stability. Food. Chem.229, 75–83. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.02.057PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

36

LinS.LiH.TaoY.LiuJ.YuanW.ChenY.et al (2020). In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation of Membrane-Active Flavone Amphiphiles: Semisynthetic Kaempferol-Derived Antimicrobials against Drug-Resistant Gram-Positive Bacteria. J. Med. Chem.63, 5797–5815. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00053PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

37

LiuF.LiL.LuW.DingZ.HuangW.LiY. T.et al (2020a). Scutellarin Ameliorates Cartilage Degeneration in Osteoarthritis by Inhibiting the Wnt/β-Catenin and MAPK Signaling Pathways. Int. Immunopharmacol.78, 105954. 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.105954PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

38

LiuT.LuoJ.BiG.DuZ.KongJ.ChenY.et al (2020b). Antibacterial Synergy Between Linezolid and Baicalein Against Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Biofilm In Vivo. Microb. Pathog.147, 104411. 10.1016/j.micpath.2020.104411PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

39

LiuX.LiuF.DingS.ShenJ.ZhuK. (2020c). Sublethal Levels of Antibiotics Promote Bacterial Persistence in Epithelial Cells. Adv. Sci. (Weinh)7, 1900840. 10.1002/advs.201900840PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

40

LiuX.WuY.MaoC.ShenJ.ZhuK. (2022). Host-acting Antibacterial Compounds Combat Cytosolic Bacteria. Trends Microbiol.,.10.1016/j.tim.2022.01.006CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

41

LiuX.ZhuK.DuanX.WangP.HanY.PengW.et al (2021). Extracellular Matrix Stiffness Modulates Host-Bacteria Interactions and Antibiotic Therapy of Bacterial Internalization. Biomaterials277, 121098. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.121098PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

42

LiuY.DingS.ShenJ.ZhuK. (2019). Nonribosomal Antibacterial Peptides that Target Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria. Nat. Prod. Rep.36, 573–592. 10.1039/c8np00031jPubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

43

LopesL. A. A.Dos Santos RodriguesJ. B.MagnaniM.De SouzaE. L.de Siqueira-JúniorJ. P. (2017). Inhibitory Effects of Flavonoids on Biofilm Formation by Staphylococcus aureus that Overexpresses Efflux Protein Genes. Microb. Pathog.107, 193–197. 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.03.033PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

44

LuH.LiX.WangG.WangC.FengJ.LuW.et al (2021). Baicalein Ameliorates Streptococcus Suis-Induced Infection In Vitro and In Vivo. Int. J. Mol. Sci.22 (11), 5829. 10.3390/ijms22115829PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

45

MartinJ. K.2ndSheehanJ. P.BrattonB. P.MooreG. M.MateusA.LiS. H.et al (2020). A Dual-Mechanism Antibiotic Kills Gram-Negative Bacteria and Avoids Drug Resistance. Cell181, 1518–e14. e1514. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.005PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

46

MathurA.FengS.HaywardJ. A.NgoC.FoxD.AtmosukartoIi.et al (2019). A Multicomponent Toxin from Bacillus Cereus Incites Inflammation and Shapes Host Outcome via the NLRP3 Inflammasome. Nat. Microbiol.4, 362–374. 10.1038/s41564-018-0318-0PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

47

MiaoJ.LinF.HuangN.TengY. (2021). Improving Anti-inflammatory Effect of Luteolin with Nano-Micelles in the Bacteria-Induced Lung Infection. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol.17, 1229–1241. 10.1166/jbn.2021.3101PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

48

MohamedE. H.AlghamdiY. S.Mostafa Abdel-HafezS.SolimanM. M.AlotaibiS. H.HassanM. Y.et al (2020). Susceptibility Assessment of Multidrug Resistant Bacteria to Natural Products. Dose Response18, 1559325820936189. 10.1177/1559325820936189PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

49

MotallebiM.KhorsandiK.SepahyA. A.ChamaniE.HosseinzadehR. (2020). Effect of Rutin as Flavonoid Compound on Photodynamic Inactivation against P. aeruginosa and S. aureus. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther.32, 102074. 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2020.102074PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

50

NarendranR.ShankarS.ReneC. L.SundaramM. M.SaiS. N.BrindhaP.et al (2016). Antimicrobial Flavonoids Isolated from Indian Medicinal Plant Scutellaria Oblonga Inhibit Biofilms Formed by Common Food Pathogens. Nat. Prod. Res.30, 2002–2006. 10.1080/14786419.2015.1104673PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

51

PalA.TripathiA. (2020). Quercetin Inhibits Carbapenemase and Efflux Pump Activities Among Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria. Apmis128, 251–259. 10.1111/apm.13015PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

52

Palacios-BaenaZ. R.GiannellaM.ManisseroD.Rodríguez-BañoJ.VialeP.LopesS.et al (2021). Risk Factors for Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacterial Infections: a Systematic Review. Clin. Microbiol. Infect.27, 228–235. 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.10.016PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

53

PalierseE.HélaryC.KrafftJ. M.GénoisI.MasseS.LaurentG.et al (2021). Baicalein-modified Hydroxyapatite Nanoparticles and Coatings with Antibacterial and Antioxidant Properties. Mater Sci. Eng. C Mater Biol. Appl.118, 111537. 10.1016/j.msec.2020.111537PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

54

ParkH. J.LeeS. J.ChoJ.GharbiA.HanH. D.KangT. H.et al (2018). Tamarixetin Exhibits Anti-inflammatory Activity and Prevents Bacterial Sepsis by Increasing IL-10 Production. J. Nat. Prod.81, 1435–1443. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.8b00155PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

55

PereiraR. V.MecenasA. S.MalafaiaC. R. A.AmaralA. C. F.MuzitanoM. F.SimasN. K.et al (2020). Evaluation of the Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Extracts and Fractions of Ocotea Notata (Ness) Mez (Lauraceae). Nat. Prod. Res.34, 3004–3007. 10.1080/14786419.2019.1602828PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

56

PhamT. H. M.BrewerS. M.ThurstonT.MassisL. M.HoneycuttJ.LugoK.et al (2020). Salmonella-driven Polarization of Granuloma Macrophages Antagonizes TNF-Mediated Pathogen Restriction during Persistent Infection. Cell Host Microbe27, 54–67. e55. 10.1016/j.chom.2019.11.011PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

57

PiwowarA.RembiałkowskaN.Rorbach-DolataA.GarbiecA.ŚlusarczykS.DoboszA.et al (2020). Anemarrhenae Asphodeloides Rhizoma Extract Enriched in Mangiferin Protects PC12 Cells against a Neurotoxic Agent-3-Nitropropionic Acid. Int. J. Mol. Sci.21, 2510. 10.3390/ijms21072510PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

58

PrawatU.ChairerkO.PhupornprasertU.SalaeA. W.TuntiwachwuttikulP. (2013). Two New C-Benzylated Dihydrochalcone Derivatives from the Leaves of Melodorum Siamensis. Planta Med.79, 83–86. 10.1055/s-0032-1327950PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

59

PruteanuM.Hernández LobatoJ. I.StachT.HenggeR. (2020). Common Plant Flavonoids Prevent the Assembly of Amyloid Curli Fibres and Can Interfere with Bacterial Biofilm Formation. Environ. Microbiol.22, 5280–5299. 10.1111/1462-2920.15216PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

60

RajkumariJ.BusiS.VasuA. C.ReddyP. (2017). Facile Green Synthesis of Baicalein Fabricated Gold Nanoparticles and Their Antibiofilm Activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Microb. Pathog.107, 261–269. 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.03.044PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

61

RashidF.AhmedR.MahmoodA.AhmadZ.BibiN.KazmiS. U. (2007). Flavonoid Glycosides from Prunus Armeniaca and the Antibacterial Activity of a Crude Extract. Arch. Pharm. Res.30, 932–937. 10.1007/BF02993959PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

62

RenN.KimE.LiB.PanH.TongT.YangC. S.et al (2019). Flavonoids Alleviating Insulin Resistance through Inhibition of Inflammatory Signaling. J. Agric. Food Chem.67, 5361–5373. 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b05348PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

63

Rodrigo Cavalcante de AraújoD.Diego Da SilvaT.HarandW.Sampaio De Andrade LimaC.Paulo Ferreira NetoJ.De Azevedo RamosB.et al (2019). Bioguided Purification of Active Compounds from Leaves of Anadenanthera Colubrina Var. Cebil (Griseb.) Altschul. Biomolecules9 (10), 590. 10.3390/biom9100590CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

64

RoweS. E.WagnerN. J.LiL.BeamJ. E.WilkinsonA. D.RadlinskiL. C.et al (2020). Reactive Oxygen Species Induce Antibiotic Tolerance during Systemic Staphylococcus aureus Infection. Nat. Microbiol.5, 282–290. 10.1038/s41564-019-0627-yPubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

65

SiebertD. A.PaganelliC. J.QueirozG. S.AlbertonM. D. (2021). Anti-inflammatory Activity of the Epicuticular Wax and Its Isolated Compounds Catechin and Gallocatechin from Eugenia brasiliensis Lam. (Myrtaceae) Leaves. Nat. Prod. Res.35, 4720–4723. 10.1080/14786419.2019.1710707PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

66

SinghD. K.TousifS.BhaskarA.DeviA.NegiK.MoitraB.et al (2021). Luteolin as a Potential Host-Directed Immunotherapy Adjunct to Isoniazid Treatment of Tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog.17, e1009805. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009805PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

67

SolnierJ.MartinL.BhaktaS.BucarF. (2020). Flavonoids as Novel Efflux Pump Inhibitors and Antimicrobials against Both Environmental and Pathogenic Intracellular Mycobacterial Species. Molecules25 (3), 734. 10.3390/molecules25030734PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

68

SongM.LiuY.HuangX.DingS.WangY.ShenJ.et al (2020). A Broad-Spectrum Antibiotic Adjuvant Reverses Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Pathogens. Nat. Microbiol.5, 1040–1050. 10.1038/s41564-020-0723-zPubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

69

SongM.LiuY.LiT.LiuX.HaoZ.DingS.et al (2021a). Plant Natural Flavonoids against Multidrug Resistant Pathogens. Adv. Sci. (Weinh)8, e2100749. 10.1002/advs.202100749PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

70

SongX.WangW.DingS.LiuX.WangY.MaH. (2021b). Puerarin Ameliorates Depression-like Behaviors of With Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stress Mice by Remodeling Their Gut Microbiota. J. Affect Disord.290, 353–363. 10.1016/j.jad.2021.04.037PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

71

SuJ. Y.LiQ. C.ZhuL. (2011). Evaluation of the In vivo Anti-Inflammatory Activity of a Flavone Glycoside from Cancrinia discoidea (Ledeb.) Poljak. Excli. j.10, 110–116. PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

72

TangD.ChenK.HuangL.LiJ. (2017). Pharmacokinetic Properties and Drug Interactions of Apigenin, a Natural Flavone. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol.13, 323–330. 10.1080/17425255.2017.1251903PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

73

TchindaC. F.SonfackG.SimoI. K.Çelikİ.VoukengI. K.NganouB. K.et al (2019). Antibacterial and Antibiotic-Modifying Activities of Fractions and Compounds from Albizia Adianthifolia against MDR Gram-Negative Enteric Bacteria. BMC Complement. Altern. Med.19, 120. 10.1186/s12906-019-2537-1PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

74

TheuretzbacherU.OuttersonK.EngelA.KarlénA. (2020). The Global Preclinical Antibacterial Pipeline. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.18, 275–285. 10.1038/s41579-019-0288-0PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

75

WaditzerM.BucarF. (2021). Flavonoids as Inhibitors of Bacterial Efflux Pumps. Molecules26 (22), 6904. 10.3390/molecules26226904PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

76

WangJ.WongY. K.LiaoF. (2018). What Has Traditional Chinese Medicine Delivered for Modern Medicine?Expert Rev. Mol. Med.20, e4. 10.1017/erm.2018.3PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

77

WangM.FirrmanJ.LiuL.YamK. (2019). A Review on Flavonoid Apigenin: Dietary Intake, ADME, Antimicrobial Effects, and Interactions with Human Gut Microbiota. Biomed. Res. Int.2019, 7010467. 10.1155/2019/7010467PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

78

WangT.ZhangP.LvH.DengX.WangJ. (2020). A Natural Dietary Flavone Myricetin as an α-Hemolysin Inhibitor for Controlling Staphylococcus aureus Infection. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol.10, 330. 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00330PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

79

WatanabeY.NagaiY.HondaH.OkamotoN.YamamotoS.HamashimaT. (2016). Isoliquiritigenin Attenuates Adipose Tissue Inflammation in vitro and Adipose Tissue Fibrosis through Inhibition of Innate Immune Responses in Mice. Sci. Rep.6, 23097. 10.1038/srep23097PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

80

WeerayuthS.Supranee Manurakchinakorn (2014). In Vitro Antioxidant Properties of Mangosteen Peel Extract. J. Food Sci. Technol.51, 3546–3558. 10.1007/s13197-012-0887-5PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

81

WeiL.MeiY.ZouL.ChenJ.TanM.WangC.et al (2020). Distribution Patterns for Bioactive Constituents in Pericarp, Stalk and Seed of Forsythiae Fructus. Molecules25, 340. 10.3390/molecules25020340PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

82

WenK.FangX.YangJ.YaoY.NandakumarK. S.SalemM. L.et al (2021). Recent Research on Flavonoids and Their Biomedical Applications. Curr. Med. Chem.28, 1042–1066. 10.2174/0929867327666200713184138PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

83

WenzelU. (2013). Flavonoids as Drugs at the Small Intestinal Level. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol.13, 864–868. 10.1016/j.coph.2013.08.015PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

84

WuM.BrownA. C. (2021). Applications of Catechins in the Treatment of Bacterial Infections. Pathogens10. 10.3390/pathogens10050546CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

85

WuY.LiY.RuanZ.LiJ.ZhangL.LuH.et al (2020). Puerarin Rebuilding the Mucus Layer and Regulating Mucin-Utilizing Bacteria to Relieve Ulcerative Colitis. J. Agric. Food Chem.68, 11402–11411. 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c4119PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

86

XiaoT.CuiY.JiH.YanL.PeiD.QuS. (2021). Baicalein Attenuates Acute Liver Injury by Blocking NLRP3 Inflammasome. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.534, 212–218. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.11.109PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

87

XieY.YangW.TangF.ChenX.RenL. (2015). Antibacterial Activities of Flavonoids: Structure-Activity Relationship and Mechanism. Curr. Med. Chem.22, 132–149. 10.2174/0929867321666140916113443PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

88

XuX.DongQ.ZhongQ.XiuW.ChenQ.WangJ.et al (2021). The Flavonoid Kurarinone Regulates Macrophage Functions via Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor and Alleviates Intestinal Inflammation in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. J. Inflamm. Res.14, 4347–4359. 10.2147/JIR.S329091PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

89

YangD.WangT.LongM.LiP. (2020). Quercetin: Its Main Pharmacological Activity and Potential Application in Clinical Medicine. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev.2020, 8825387. 10.1155/2020/8825387PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

90

YelinI.KishonyR. (2018). Antibiotic Resistance. Cell172, 1136–e1. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.018PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

91

ZhangH.LuanY.JingS.WangY.GaoZ.YangP.et al (2020). Baicalein Mediates Protection against Staphylococcus Aureus-Induced Pneumonia by Inhibiting the Coagulase Activity of vWbp. Biochem. Pharmacol.178, 114024. 10.1016/j.bcp.2020.114024PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

92

ZhangT.QiuY.LuoQ.ZhaoL.YanX.DingQ.et al (2018). The Mechanism by Which Luteolin Disrupts the Cytoplasmic Membrane of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Phys. Chem. B122, 1427–1438. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b05766PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

93

ZhangX. X.ShiQ. Q.JiD.NiuL. X.ZhangY. L. (2017). Determination of the Phenolic Content, Profile, and Antioxidant Activity of Seeds from Nine Tree Peony (Paeonia Section Moutan DC.) Species Native to China. Food Res. Int.97, 141–148. 10.1016/j.foodres.2017.03.018PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

94

ZulaufK. E.KirbyJ. E. (2020). Discovery of Small-Molecule Inhibitors of Multidrug-Resistance Plasmid Maintenance Using a High-Throughput Screening Approach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.117, 29839–29850. 10.1073/pnas.2005948117PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Summary

Keywords

natural plant flavonoids, heat-clearing Chinese medicine, antibiotic resistance, multidrug resistant bacteria, antibacterial modes

Citation

Song L, Hu X, Ren X, Liu J and Liu X (2022) Antibacterial Modes of Herbal Flavonoids Combat Resistant Bacteria. Front. Pharmacol. 13:873374. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.873374

Received

10 February 2022

Accepted

17 May 2022

Published

27 June 2022

Volume

13 - 2022

Edited by

Younes Smani, Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), Spain

Reviewed by

Michal Letek, Universidad de León, Spain

Wael Abdel Halim Hegazy, Zagazig University, Egypt

Gandhi Radis Baptista, Federal University of Ceara, Brazil

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Song, Hu, Ren, Liu and Liu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaoye Liu, xiaoyeliu@bua.edu.cn

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

This article was submitted to Pharmacology of Infectious Diseases, a section of the journal Frontiers in Pharmacology

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.