- Department of Political Science, Memorial University, St. John’s, NL, Canada

In American politics, few argue with the idea that leaders matter: in the 2020 American election, the media closely tracked the performance and activities of Joe Biden and Donald Trump, for example, suggesting to us that who they are matters. Voters indicate on their ballot which presidential candidate they prefer, marking an x next to the person’s name, giving further credence to the idea that the individual matters in the process. Contemporary Anglo-Westminster-style democracies have many things in common with the United States, but operate with completely different political systems, and without a direct vote for a specific party leader. What is the relationship between voters and party leaders in these contexts? Do party leaders matter the same way in these countries? Has this relationship changed over time? Are we really seeing the personalization of parliamentary elections, as some scholars have suggested? The personalization literature provides us with mixed evidence of the increasing importance of leaders, and part of the reason for that maybe linked to the lack of comparable data. This paper assesses the role of leaders in the United States as well as four parliamentary democracies (Britain, Canada, New Zealand, and Australia) over time. Combining data from the election studies of these five countries from the 1960 s to the present, the analyses presented here suggest that leaders are not increasingly important to voters over time, but that leaders have always been important to election outcomes. What has changed over time, however, is the way partisans see the leaders of other parties. Partisans are increasingly polarized in their views of opposing party leaders, and this has the potential to change the impact of leaders in the electoral process.

Introduction

Much has been made in recent years about the role of leaders in the minds of voters (Mughan, 2000; Johnston, 2002; King, 2002; Poguntke and Webb, 2005; Bittner, 2011; Da Silva 2019; De Angelis and Garzia 2016; Garzia et al., 2020). The topic is of increasing interest around the world, and scholars of parliamentary democracy have taken particular notice of the penchant voters have for evaluating party leaders and considering those evaluations when they head to the ballot box (Bean, 1993; McAllister, 1996; Bittner, 2011). Many have argued that this focus on party leaders among the electorate is new, and point to the “personalization” of politics, arguing that what is normal in presidential systems has become normal in parliamentary systems.

Evidence for this personalization of politics is mixed, however. In some countries there is substantial evidence for the increasing role of leaders in the minds of voters (Rahat and Sheafer, 2007; Balmas et al., 2014), while in others research suggests that evidence of personalization is lacking (Kaase, 1994; Bittner, 2018). The literature as a whole continues to be convinced that personalization is taking place, as observed by Karvonen (2009).

While the evidence of personalization is mixed (sometimes even scant), part of the issue may be related to available data. Quite simply, it is difficult to assess the importance of leaders, and very few studies have done so on a scale large enough to make sweeping conclusions about the role of leaders in the minds of voters. Several comparative, longitudinal analyses do exist (Aarts et al., 2011; Bittner, 2011), but most of those analyses were not necessarily looking for personalization as a “process,” they were seeking to determine whether leaders matter “at all” (see, however, Garzia et al., 2020). In order to argue that increased personalization is taking place, we must have evidence that leaders are not just important, but that they are more important today than they have been in the past. This is not the kind of research that can be done with survey data obtained at a single point in time; we need information gathered over time. This is similar to the argument made by Garzia et al. (2020), who assess the role of personalization in Western European countries over time. This paper builds on their work and expands the scope, as it moves the focus to a new set of countries, concentrating on personalization in Anglo-American democracies.

In this paper I assess data from five countries, including Canada, Britain, United States, Australia, and New Zealand, and assess the role of party leaders in the minds of voters over time, beginning in 1968 (Canada) and ending in 2016 (United States and Australia).1 I rely upon data from the national election studies of each of these five countries, which were coded in a similar fashion and then pooled together in order to assess the role of party leaders over time.2 The data analyses presented here suggest that leaders are not increasingly important to voters over time, but that leaders have always been important to election outcomes. More research is needed to better understand the processes associated with personalization, but at first (comparative, longitudinal) glance, the argument that personalization is on the rise does not apply universally when we assess cross-national and longitudinal data.

Literature Review

Personalization of Politics: What Do We Know So Far?

The personalization literature is rich, diverse, and fascinating. The argument is appealing, and the lament is compelling, especially for those who would argue that other factors (such as the state of the economy, or party platforms) “should” be more important to voters than the personality traits of party leaders. The normative objection to the importance of party leaders can be likened to the constant disapproval of the preferences of “millennials,” a generation of adults who are seen by many to be frivolous, irresponsible, with a penchant for selfies and leisure rather than hard work and settling down to have families (e.g., headlines like “Millionaire to Millennials: Your avocado toast addictions is costing you a house” in United States Today (Cummings, 2017) https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/2017/05/16/millionaire-tells-millennials-your-avocado-addiction-costing-you-house/101727712/). There has been a decline in the “quality” of citizenship, the argument goes, and voters are irresponsible, lack knowledge, and focus on silly things rather than important factors.3 This is not the view held by all. Bittner (2011), for example, suggests that voters are able to glean important information from assessing leaders that they would not be able to obtain by focusing on policies or platforms alone.

Putting aside normative objections for a moment, it is important to note that there has been a substantial body of scholarship which has assessed the personalization of politics, and which points to a number of key factors explaining the rise in importance of leaders. In their review of the literature, Costa Lobo and Curtice (2014, p. 2) point to four key factors explaining personalization. They suggest that 1) because of modernization and individualization, we have seen a decline in long-term forces that tie voters to parties; 2) the mediatization of campaigns and politics has led to an emphasis on candidates, on their personal campaign organization, and on televised debates; 3) the downsizing of the state and globalization have resulted in increased prominence of leaders as representatives of citizens on the global stage; and 4) they point to changes in party organization, suggesting that parties now conduct business in a way that makes leaders more central and visible to all. Most scholarship tends to agree that the media has changed the way leaders are covered in the contemporary era, and that over time, we have seen an increase of coverage of leaders at the expense of party or other possible focal points (Mughan, 2000; Rahat and Sheafer, 2007; Karvonen, 2009). More cross-national research is needed, but for now, I focus my attention on the decrease in the role of long-term forces and the change in social bases of political behavior.

The Changing Bases of Political Behavior

Scholars for some time have pointed to changes in the party systems of western countries leading to the decreasing importance of parties in the minds of voters (Wattenberg, 1984; Franklin, 1992), which constitutes a major change from the observations about the importance of parties that were made by early scholars of voting behavior and party systems (Campbell et al., 1960; Lipset and Rokkan, 1967). As Franklin observes in relation to understanding the foundations of electoral choice, there was a 20% drop in the variance accounted for by social cleavages between the 1960 and the 1980 s. While in the 1970 s, it was clearly accepted by most scholars that “attitudes towards the parties were a better guide to voting behavior than were attitudes towards the leaders” (Butler and Stokes, 1974), in later years, this relationship began to be called into question. Garzia (2014, p. 8) notes that in recent years “…parties have undergone deep transformations that are at once cause, and consequence, of personalization,” as the transformation from class-mass and denominational parties to catch-all parties in Europe has led to a change in the way that voters see and relate to political parties. He observes that both Downs (1957) and Kircheimer (1966) noted and tracked this process, which has led to a breakdown in the traditional cleavages (class, religion) that propped up and propelled party politics as observed by Lipset and Rokkan in the late 1960 s.

The literature emerging from both Europe and the United States has noted that the factors motivating the decision-making processes of voters has shifted over time, as voters note that the “man” is having an increasing influence on their vote choice than is “the party” (Dalton et al., 2000; Wattenberg, 1984, 1991). Recent work shows that partisan dealignment plays a major role in influencing personalization in Western Europe (Garzia et al., 2020) and Garzia (2014, p. 19) suggests that “partisan attachments have become increasingly connected to voters’ attitudes towards party leaders” because of increased candidate-centred campaigning by catch-all parties; because of increased role of leaders in shaping party policy; and because of an increased tendency of voters to think about politics in “personal rather than partisan terms.” Indeed, Garzia goes as far as to suggest that the causal arrow between partisanship and leader evaluations needs to be flipped, as leader evaluations may have a substantial influence on voters’ feelings towards parties (2014, p. 21). De Angelis and Garzia (2016) refer to “reciprocal causation” between leader effects, partisanship, and voting, reinforcing the idea that the causal arrow is potentially not as clear as we once thought, and providing additional impetus for another deep and careful assessment of the relationship between these variables.

The notion that partisanship matters less to voters now than it did years ago is not new, but is also not undisputed. Indeed, in their discussion of Canadian voters, Gidengil and Blais (2007) note the conflicting evidence of decreasing ties between voters and parties, suggesting that the evidence is scant. Johnston’s (2006) review essay of partisanship also suggests that the concept of Party ID remains strong, and can continue to be thought of as an “unmoved mover.” Looking more closely at the impact of partisanship and perceptions of leaders in the United States and Germany, Bartels (2002) and Brettschneider and Gabriel (2002) both find that candidate effects are equal to or stronger amongst partisans compared to non-partisans, suggesting that the impact of the long-term force has not been replaced by the short-term force.

The personalization scholarship as a whole highlights the decreasing importance of long-term factors anchoring voting behavior (partisanship, class, and religion); and the increasing importance of short-term factors such as perceptions of leaders, evaluations of the economy, and other issue attitudes (Dalton et al., 1984; Wattenberg, 1984; Mughan, 2000; Poguntke and Webb, 2005; Rahat and Sheafer, 2007; Costa Lobo and Curtice, 2014). None of these scholars debates the notion that leaders matter in the minds of voters. Indeed, the wider literature points to the importance of party leaders in the minds of voters, even if not focusing on personalization as such (Kinder, 1978; Kinder et al., 1980; Kinder and Fiske, 1986; Rahn et al., 1990; Johnston, 2002; Peterson, 2004; Bittner, 2011).

Ultimately, it is important to note that there is strong evidence in support of the notion that leaders play a prominent role in the minds of voters and in electoral outcomes. The evidence for personalization itself, however, is less overwhelming. Perhaps most importantly, and as some scholars note, personalization assumes a process: “…the notion of personalization does not only imply that individual politicians matter in the political process—they are also assumed to matter more throughout time” (Garzia, 2014, p. 6 emphasis in original). As such, many scholars of personalization have made substantial effort to (where possible) assess the dynamics related to personalization on a longitudinal basis. In some cases, in a single country (e.g., Kaase, 1994; Mughan, 2000; Gidengil and Blais, 2007), in other cases, in multiple countries (e.g., Karvonen, 2009; Garzia, 2014; Garzia et al., 2020). Scholars do not agree, however, on the extent to which personalization is taking place. Some find strong evidence of an increase in the importance of party leaders over time, while others do not. More research is needed, ideally research that is both comparative and longitudinal. As Karvonen notes, evidence from several countries is necessary to eliminate the risk that the peculiarities of any single national system dictate the conclusion drawn. The alleged trend towards personalization should be present in most, if not all countries if personalization is such a pervasive phenomenon as is frequently suggested (2009, p. 69).

While we have some comparative, over-time analyses to assess, we need data from more countries, over more years, and we need them to be analyzed in a similar way. To date, some studies that have been conducted look only at a single country, and many use different sources of data: some rely upon Gallup data to inform analyses of the electoral impact of the party leaders (Mughan, 2000), while others use data from national election studies (Bartels, 2002; Brettschneider and Gabriel, 2002; Gidengil and Blais, 2007; Garzia, 2014; Garzia et al., 2020). As has been argued elsewhere (Bittner, 2011), seeking to find patterns across countries when using very different data sources and types of data is suboptimal, and some of the disagreement in the literature may be (at least partially) the result of these very different types of analyses that have been performed in the past.

Data and Methods

In order to assess the role of party leaders in the minds of voters, and whether or not leaders have become more important to voters over time, I conduct a cross-national, longitudinal analysis using data from the national election studies of five countries: Canada, Britain, United States, Australia, and New Zealand. It is important to recall that four of these five countries have parliamentary systems, systems in which voters do not have an opportunity to vote directly for the head of government. According to many scholars (Karvonen, 2009; Costa Lobo and Curtice, 2014), leaders should not matter “as much” in these countries, since they do not appear on the ballot for most voters (only those voters residing in the leader’s district have the opportunity to vote for the Member of Parliament who will also become Prime Minister if the party is successful). These five countries in many ways are quite similar, having similar cultures and democratic origins (as a result of colonialism and the inheritance of the British tradition). As such, assessing the role of leaders in these five countries will allow us to make important inroads into whether or not personalization of parliamentary elections has taken place over time.

Assessing Anglo-American democracies may provide additional important insights into the personalization hypothesis, as scholars have noted that institutional effects may structure the ways in which parties compete in the system, which may influence the importance of leaders. Curtice and Lisi (2014) assessed party competition and leader effects, and Bittner (2011) provides an overview of the role of political institutions in structuring vote choice. Anglo-Westminster democracies tend to have party systems with a low effective number of parties competing, which may influence the way that leaders are perceived by voters.4 A systematic assessment of personalization in these five countries has not been done in a coordinated fashion.

This type of cross-national and longitudinal analysis is time-consuming and challenging, largely because different questions are asked in each election study across countries and over time, and assembling a usable dataset that incorporates these differences is not a simple task. The dataset that was coded and compiled for this study includes a total of 57 election studies from 1968 to 2016 (14 for Canada, 11 for United Kingdom, 13 for United States, 11 for Australia, and 9 for New Zealand) which does not represent the universe of data collected for these countries, but incorporates all of the election studies that are available in that period of time and include questions about party leaders, either in the form of personality traits and/or feelings thermometers. Scholars have argued that thermometer ratings are not optimal for assessing attitudes towards party leaders, because they are noisy and imprecise: they contain so many “other” components—attitudes about the party and so on (Johnston, 2002; Bittner, 2011). In order to truly assess how voters feel about a given party leader, is it preferable to assess their perceptions of leaders’ personality traits specifically. I concentrate my analysis on the evaluation of traits wherever possible, which is another unique contribution of this paper. Unfortunately these measures are not always available. In order to maximize the ability to track perceptions of leaders I also look at feeling thermometers across all countries and years. By looking at both traits and thermometers we are able to get a more fulsome understanding of the role of personalization in elections in these five countries.

In addition to perceptions of party leaders, I gathered and re-coded variables related to respondents’ partisanship (including both PID and strength of partisanship), vote choice, party thermometers, perceptions of the economy (both the national economy and individual pocketbooks), taxation vs. spending, social liberalism (e.g., attitudes towards abortion, same sex marriage, and immigration and diversity), the major election issue in a given election, as well as a series of demographic variables, including age, sex, income, education, and ethnicity. I followed similar coding patterns to that found in Bittner (2011), in order to be able to assess the attitudes of respondents from a number of countries and over time.5

The analysis proceeds in two stages. I begin with the most “complex” part, and show the impact of perceptions of party leaders on vote choice over time and across countries. I then explore the data and track 1) perceptions of party leaders of each country’s two major parties over time; 2) rates of partisanship (and non-partisanship) over time and across countries; 3) strength of partisanship over time; and 4) left/right ideological self-placement over time.6 By looking at these variables, we are able to get a better sense of, first, whether leaders have become more important in the minds of voters over time; and second, the extent to which changes in these other explanatory factors may have contributed to the personalization of politics.

Discussion

The Impact of Party Leaders on Vote Choice Over Time

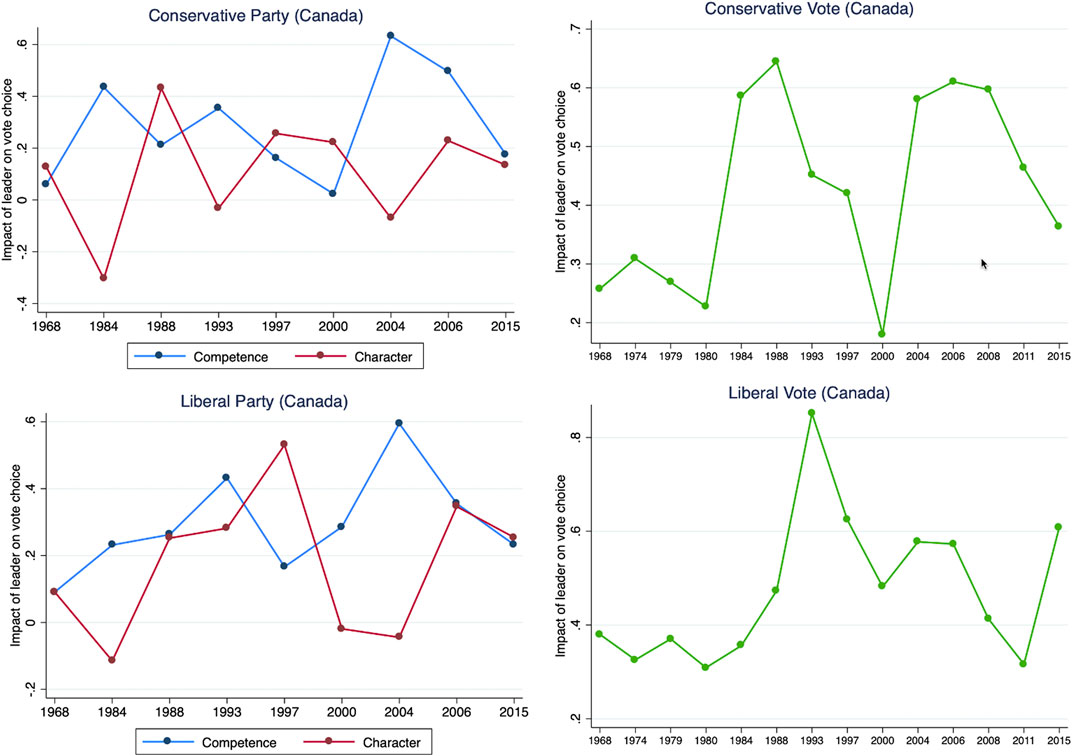

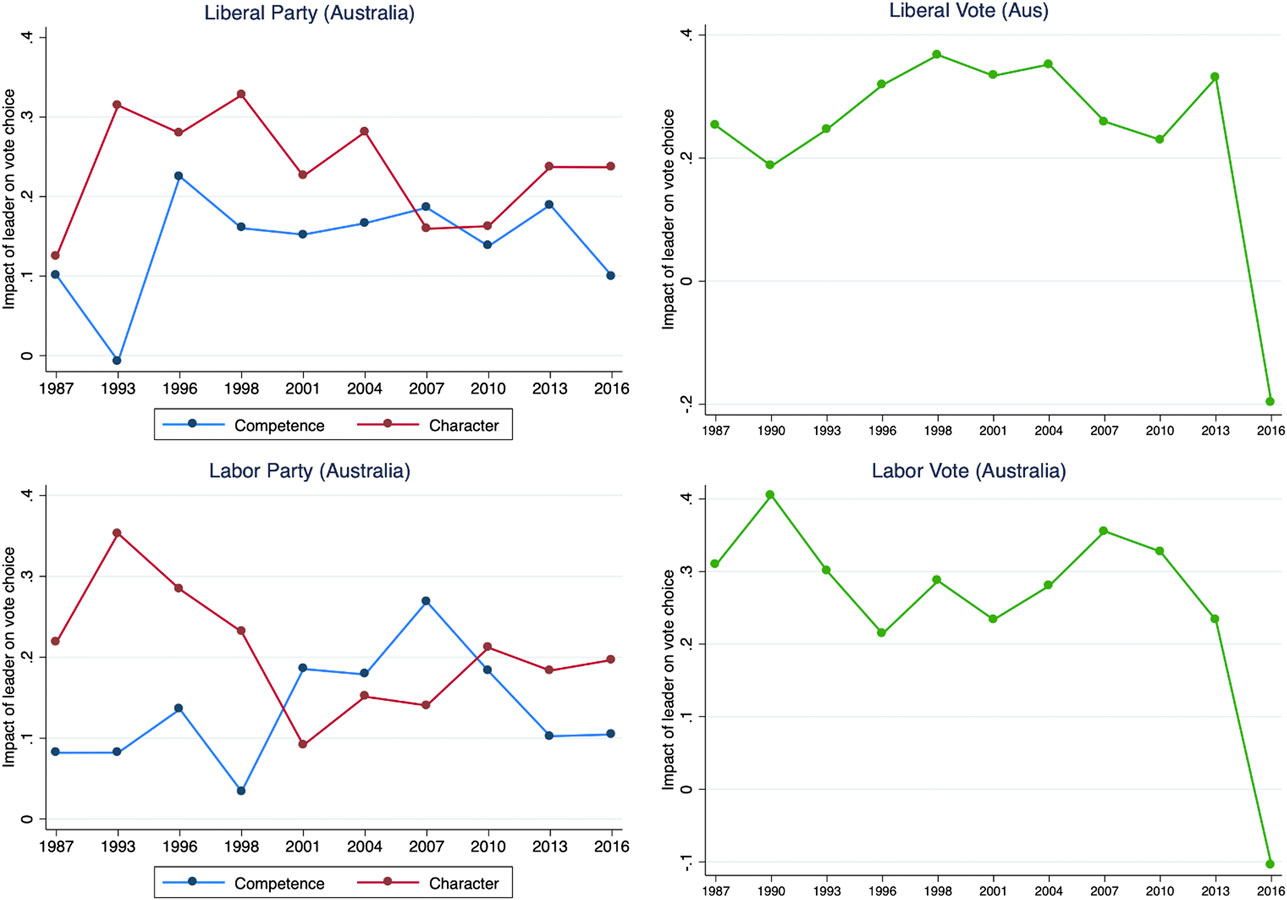

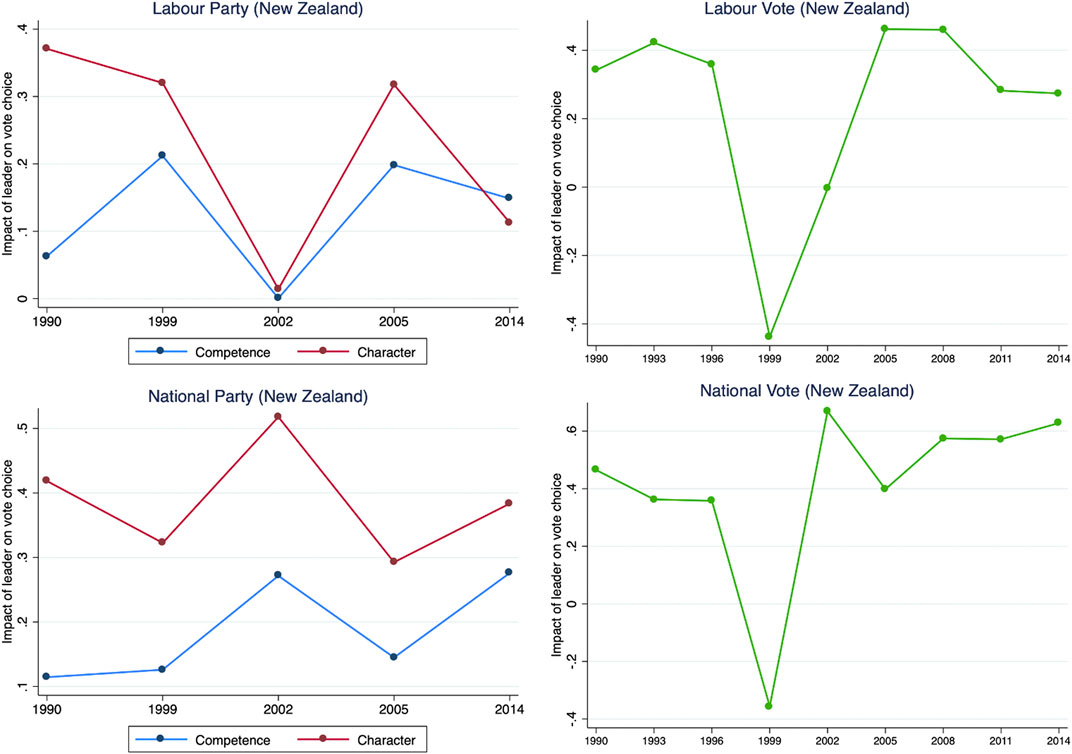

In this paper, I begin by assessing whether leaders have become more important over time. In order to be able to speak of a personalization of politics, we need to be able to establish that leaders are becoming more important to elections over time. That is, arguing that there has been a personalization of politics necessarily assumes a process by which leaders have become more influential upon voters. In order to test this hypothesis, I ran a series of regression analyses, regressing vote choice for each of the top two parties in each country/year (Conservative, Liberal, Republican, Democrat, and so on) on perceptions of party leaders, as well as a series of control variables.7 The charts presented in Figures 1–5 present the plotted marginal effects of leaders’ personality traits and feelings thermometers on votes for a given party.8,9

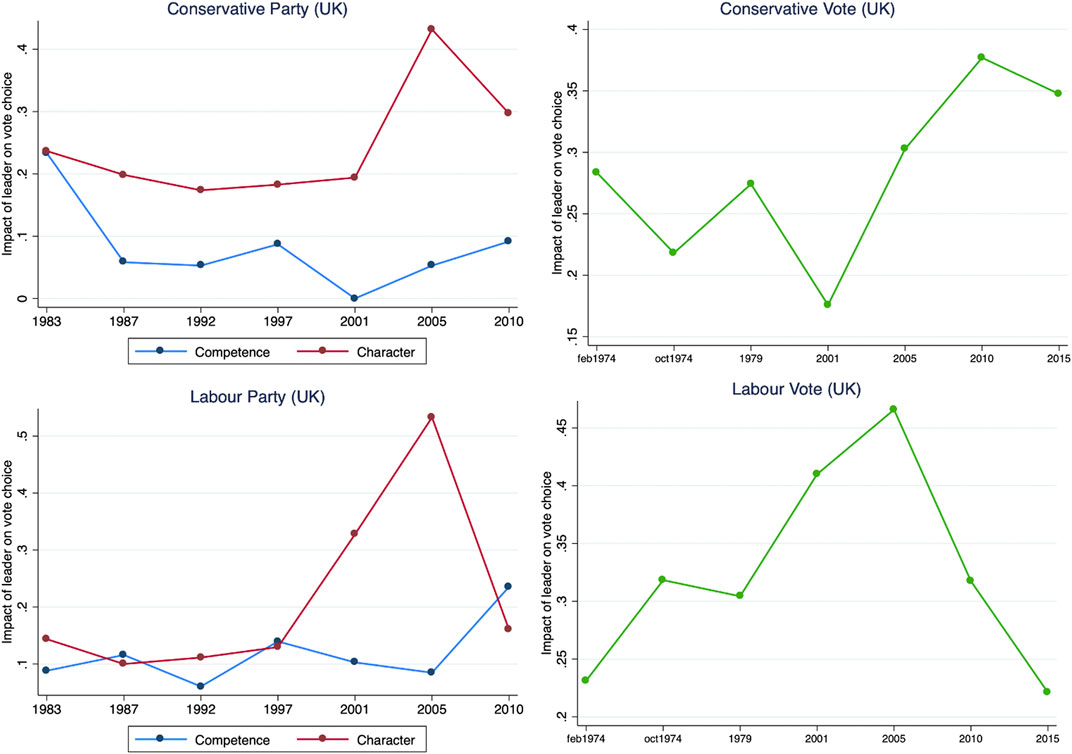

FIGURE 2. United Kingdom: Impact of leaders traits and thermometer ratings on vote for top two parties.

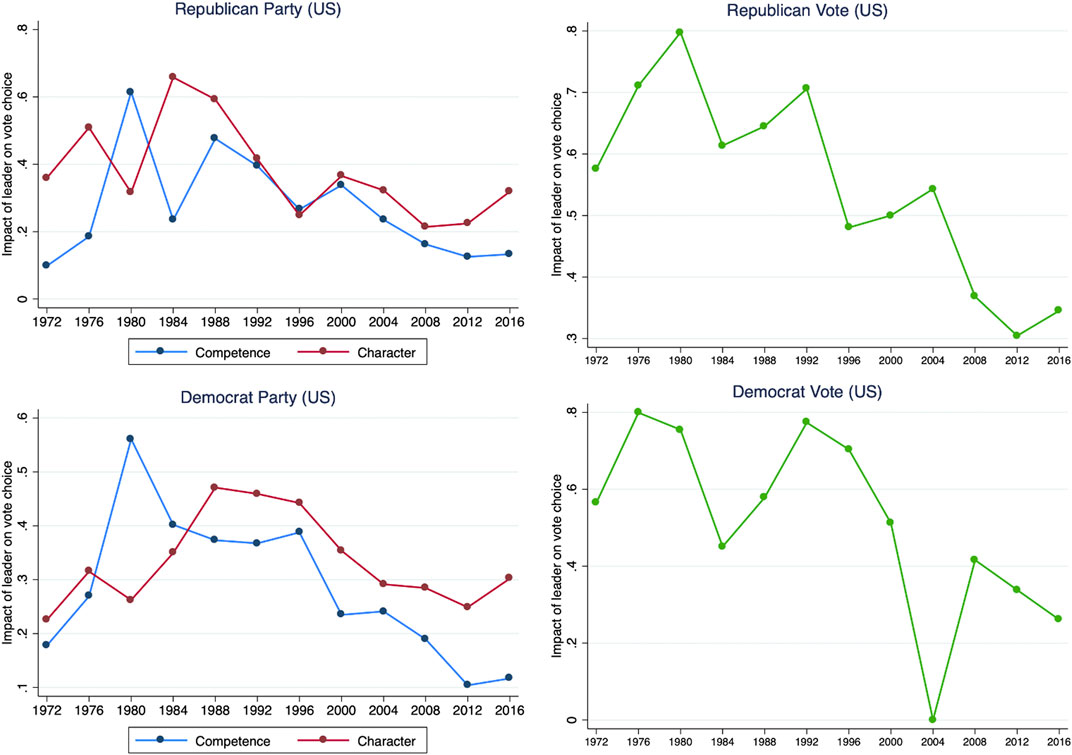

FIGURE 3. United States: Impact of leaders traits and thermometer ratings on vote for top two parties.

FIGURE 5. New Zealand: Impact of leaders traits and thermometer ratings on vote for top two parties.

In Figures 1–5, depicted on the left-hand side is the impact of perceptions of a given party leader’s character and competence (that is, leaders’ personality traits)10 on vote for that leader’s party. On the right-hand side we find the impact of “feelings” towards the leader (as measured by a thermometer rating) on vote for that leader’s party. Dependent variables across all five figures are binary, where vote for the party is coded as 1, and vote for any other party is coded as 0. Independent variables include demographic and PID controls, as well as feelings towards “other” leaders in the election that year (because voters do not evaluate leaders in a vacuum, but en masse and in comparison with one another, as per Bittner 2011).11

Figure 1 plots the impact of perceptions of leaders of the Conservative Party and Liberal Party (in Canada) on votes for those two parties. If “personalization” were taking place, then we would see a clear upward trend in the impact of leaders on vote choice. What we see, is that in some years, the leader matters more than others, both in terms of personality traits as well as thermometer ratings. In the case of vote for the Conservative Party, the impact of the Conservative leader’s competence moves up and down quite a bit, and ends up close to where it began in 1968. The impact of the leader’s character rating also moves up and down quite a bit, having higher or lower impacts on vote choice in different election years, also ending up close to where it began. A similar pattern emerges for the impact of leaders’ traits on vote for the Liberal Party. In some years, the leader’s character and competence account for an increase in likelihood of vote for the party, and in other years the effect is negligible. There is no clear upward climb, however, in the impact of leaders’ traits on vote choice. Similarly, when we assess the impact of thermometer ratings, it is clear that there is no steady upward trend. Having said that, it is clear that the impact of thermometer ratings is higher, on average, in the latter half of the graph (1997–2015) than in the earlier elections. One might argue that leaders have become more important over time, but this is not a clear pattern.

Across the remaining four figures plotting the impact of leaders’ traits/thermometer ratings on vote choice, there is similarly no clear upward trend. The effect of leaders on the vote is higher in some years than others across all countries, and appears to bounce around for the most part. The one country where a clear pattern can be seen is the United States, where the effect of leaders appears to be on the decline. There is a discernible and steady downward trend in the influence of both leaders’ personality traits (character and competence) as well as thermometer ratings on vote for the Republican and Democratic Parties. Controlling for partisanship, demographics, and so on, American party leaders appear to be playing a lesser role in the decision-making process of American voters on election day.

Taken as a whole, Figures 1–5 suggest that not only do we not see an increase in the impact of leaders over time and across space, the sole country with a presidential system (United States) appears to be paying less attention to its party leaders when it heads to the ballot box, in comparison to what American voters were doing in the 1970 and 1980 s. More research is needed, but at first glance, it seems that there is not a great deal of evidence to support the idea that leaders have become more important to vote choice over time in the states examined.

Understanding the Dynamics of Leader Evaluations and Electoral Politics Over Time

Perhaps taking a closer look at evaluations of party leaders, rather than assessing their impact on vote choice will help us to better understand dynamics related to perceptions of party leaders, and may shed additional light on the patterns seen in Figures 1–5.

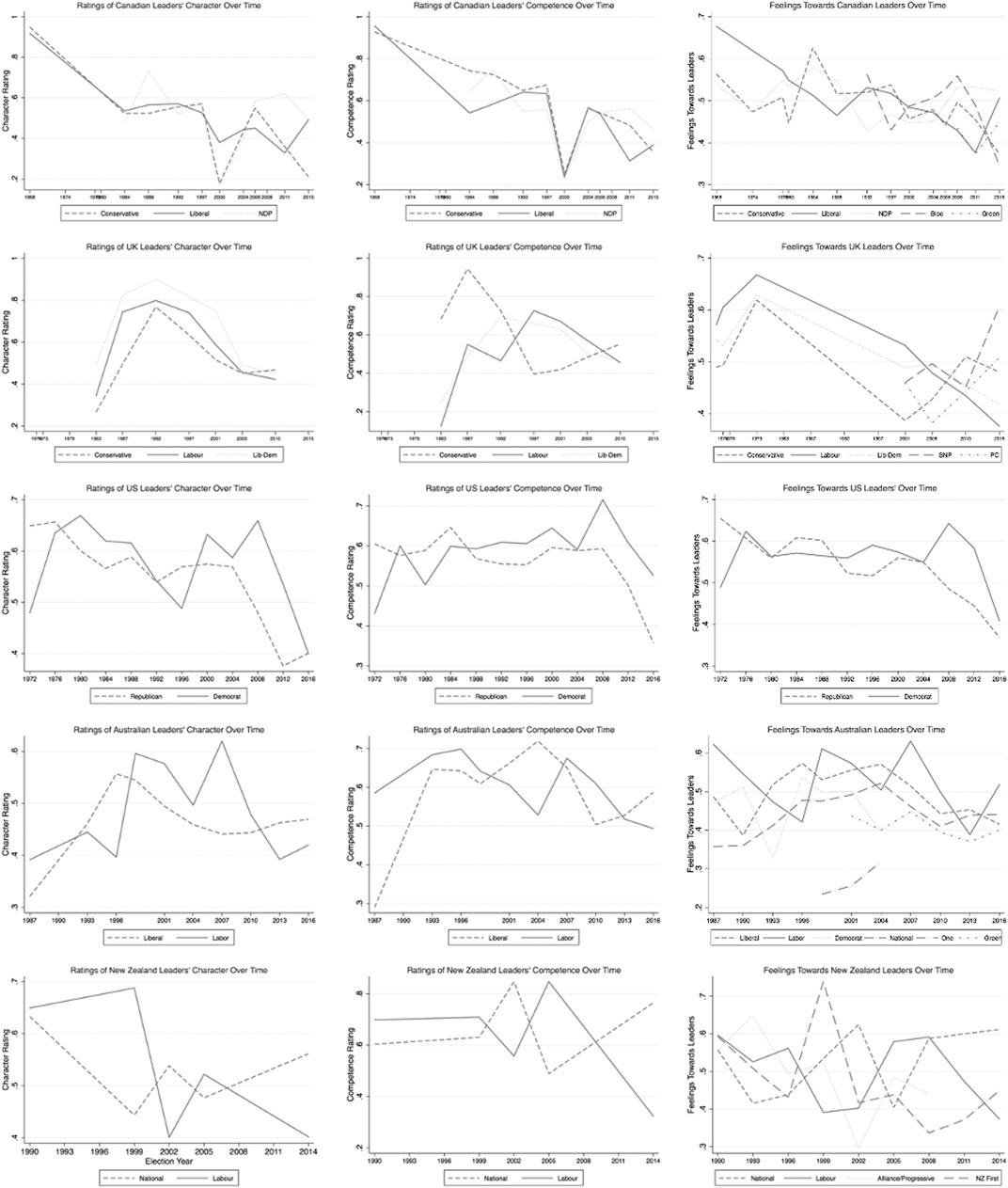

Figure 6 presents 15 graphs, depicting the average rating of leaders’ competence, character, and thermometer ratings across all five countries and over time, for as many as parties as possible. As mentioned earlier, more thermometer data was collected than personality trait data, and as a result, the right-most panel tracks data for the leaders of a larger number of parties (as many as six party leaders in Australia).

Figure 6 clearly illustrates the fluctuations that occur in perceptions of party leaders over time. No line is straight, and no lines are identical, all of which suggests that voters discern between the leaders of different parties over time and across space. Even in situations where the same leader contests more than a single election in a country, we see fluctuation, indicating that voters perceive the same leader differently over time. As voters become more familiar with a leader, their perceptions of that individual and his/her strengths may change, as indicated in Bittner (2013).

What is most interesting about these graphs is not that voters are able to differentiate across leaders over time, as it has been known for quite a while that it is relatively “easy” to be able to decide how we feel about candidates. What is interesting is that in the majority of these graphs, the average rating attributed to party leaders over time is decreasing: that is, with time, voters have come to see party leaders in a less favorable light. The Canadian, British, and American graphs most clearly show a decline in evaluations over time, as leaders in 2015/2016 receive substantially lower ratings on both personality traits (character and competence) as well as overall feelings thermometers. The downward trend is less stark in Australia and New Zealand, although there is a decline present there as well, especially since the early 1990 s. These graphs present averages only: they do not control for partisanship, demographics, or anything else. More research is needed to better understand what might be happening to evaluations of party leaders over time. For now, suffice it to say that there has been substantial movement in leader ratings over time and across space: contemporary voters in these five countries view party leaders much more negatively than they did in the 1960, 1970, and 1980 s. Whether this is linked to a “personalization of politics” in these countries is unclear, but probably unlikely, given the trends found in Figures 1–5.

The Dynamics of Partisanship Over Time

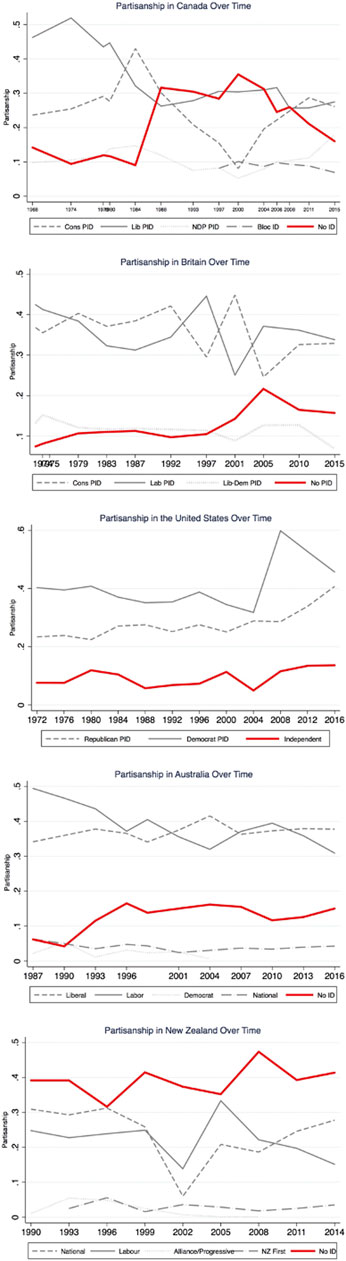

Scholars of personalization have suggested for some time that the process is linked to a decrease in the partisan affiliation of voters (e.g., Dalton et al., 2000; Da Silva, 2019; Garzia et al., 2020). As parties have become less important in the minds of voters, they argue, leaders have come to fill the void, and increasingly anchor the outcomes of elections and the decisions made at the ballot box.

The data from these five countries puts that argument into question. Figure 7 tracks party identification over time in Canada, Britain, United States, Australia, and New Zealand. The grey lines track the rates at which respondents claim to identify with specific (major) parties, and the bold red lines track the number of individuals claiming to have no identification to parties (or claiming to be Independents, in the case of the United States). As all of the graphs make clear, there is no massive downward trend in identification with parties, nor, conversely, is there a major upward trend in the proportion of the population claiming to be Independent or non-partisan. The largest fluctuations can be seen in Canada and Britain. In the case of Canada, increases in non-partisanship appear to coincide with party system flux in the late 1990/early 2000 s when the Conservative Party was in disarray and when we saw the emergence of the Reform Party on the right and the Bloc Quebecois (a separatist party) in the country’s predominately French-speaking province. The number of non-partisans in Canada has returned closer to “normal” in the most recent two elections, as the party system has reached a new equilibrium. In Britain, we see a slight increase in non-partisans over the last fifteen years, perhaps coinciding with fluctuations in support for the Conservative Party (when the Conservative line goes up, the no-ID line goes down, and vice versa). This pattern may also be linked to recent events taking place in Britain, namely, Brexit. It is possible that the Brexit debate has changed the nature of considerations being made by voters, who are focusing more on this one issue, rather than leaders or partisanship or anything else.12 This relationship needs additional examination.

In the other three countries, the proportion of the population to claim to be non-partisan fluctuates from year to year, but there is no clear upward or downward trend. The proportion of New Zealanders to claim non-partisanship is highest among the citizens of these five countries, but it has not increased over time (at least not since 1990). Taken together, these graphs do not provide any support for the idea that voters are disowning parties nor that they are becoming more non-partisan than in the past.

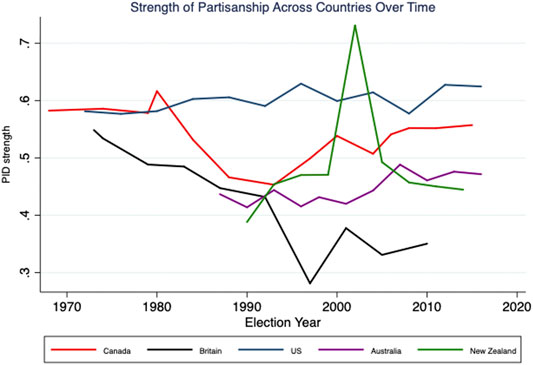

Perhaps a better measure or indicator of the decline of partisanship is linked to “strength” of partisanship rather than Party ID/non-partisanship. These data have also been collected in the election studies of these five countries, and Figure 8 tracks average strength of party identification (PID) over time.

As Figure 8 indicates, only one country has experienced a clear decline in the strength of partisanship over time: Britain. The other countries have maintained broadly steady rates of party ID strength, and in two cases (Australia and the United States) we even see slight increases in levels of PID strength. A picture of Britain is emerging as potentially the one place where we see an increase in the likelihood of a “personalization” of politics based on a decline of partisanship: rates of PID are going down, rates of non-partisanship are going up, and the strength of partisanship among partisans has declined since the 1970s. However, recall from Figure 2, the impact of party leaders on vote choice in Britain has not markedly increased over time, suggesting that voters are not moving away from parties and towards leaders as anchors of the vote. It is not clear from these analyses what is anchoring British voters in place of parties. More research is needed.

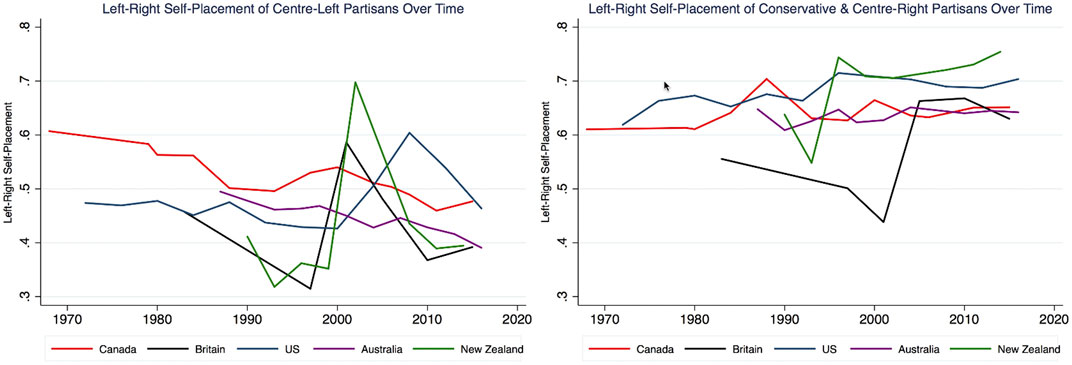

Lipset and Rokkan (1967) pointed to the social bases for party organization that grounded the parties and helped to organize voters. Some have suggested that the personalization of politics has taken place because the traditional social bases of party organization have shifted, and long-term forces such as ideological leanings are less important to grounding voter behavior. Figure 9 tracks left-right ideological self-placement among voters in these five countries, among two sets of partisan groups: partisans of centre-left parties (for each country, one of the two major competitors in elections) and partisans of conservative and centre-right parties (for each country, one of the other two major competitors in elections).13

Two trends emerge over time: first, there appears to be a gradual downward (left-ward) slope in the average left-right self-placement of centre-left partisans. This means that the partisans of centre-left parties in these five countries have moved to the left over time. The movement is not entirely linear for all countries: there were a number of spikes to the right in the decade from 2000 to 2010 (in Britain, United States, and New Zealand). For Canadians and Australians, the (red and purple lines), the move to the left was more linear, with no big spike in the 2000s.

Amongst conservative and centre-right (New Zealand) partisans, there is a slight trend upward, indicating that partisans have become more right-leaning over time. Again, this movement is not universal, nor is it linear for all. In Britain (black line), we see a move to the left among conservatives until the early 2000s, then a large jump to the current placement. In Canada, we see a large move to the right in 1988, before moving again to the left and then gradually moving back to the right over time. In New Zealand, there is a small drop to the left in the early 1990s before a large jump to the right among National Party partisans. Also visible is a steady gradual move to the right amongst Republicans in the United States. They begin in the early 1970s with an average left-right self-placement rating of 0.6 on a scale of 0, 1, and move to 0.7 by the 2016 election.

When we take the two panels together, and compare partisans within a single country, a pattern of ideological polarization emerges, perhaps unsurprising to scholars of elections and behavior. In Canada, Liberal partisans have moved to the left, Conservatives have moved slightly to the right. In Britain, Labour supporters have bounced around but end up in 2015 to the left of where they began in the early 1980 s. Australian Labor supporters have moved to the left, while Liberal partisans have remained fairly stable in their ideological leanings. In United States, Republicans have moved steadily to the right, while Democrat partisans have bounced around but in the 2016 election are nearly identically placed to where they were in the early 1970 s. The pattern in New Zealand is similar to that of the US: National Party supporters have moved to the right, while Labour partisans bounced around but end up where they began in 1990. This polarization in left-right self-placement across partisans may help to explain both why leaders are less important over time (Figures 1–5), as well as the decreasing average ratings of leaders over time. If strength of partisanship is not universally declining (Figure 8), and if the proportion of voters claiming to be partisans is not universally declining, but parties are becoming increasingly polarized on the left-right ideological spectrum, it is possible that the lens through which they are evaluating party leaders is also increasingly polarized. Indeed, recent work points to the potential importance of negative personalization (Garzia and Silva, 2021) and negative partisanship (Abramowitz and Webster, 2016), and provides important insights into the potential dynamics of ideological and affective polarization in influencing perceptions of leaders.

A Brief Dive Into Polarization and Leader Evaluations

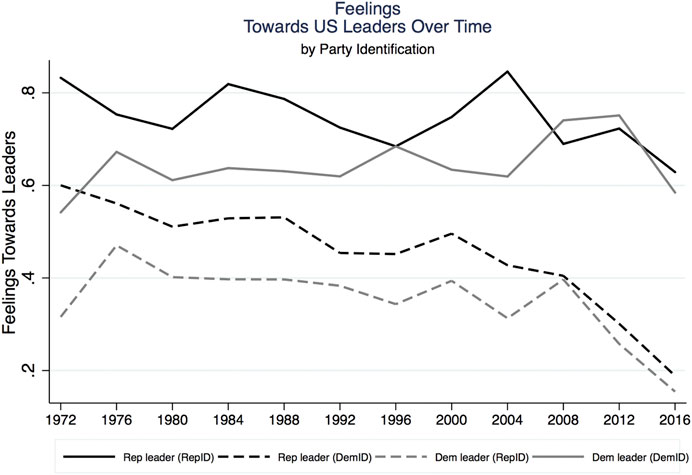

In order to better assess the potential role played by party polarization, I focus on the United States and Canada in this final section, tracking average ratings of party leaders among partisans. I do not differentiate theoretically or methodologically between ideological and affective polarization in the analyses presented here, although I do think this will be important in subsequent analyses as we explore these trends in greater detail in the future. Figure 10 presents these data for the United States, while Figures 11–13 present more detailed results for Canada.

Figure 10 tracks ratings on the feeling thermometer for both Republican and Democrat leaders, among Republican and Democrat partisans. The solid lines represent evaluations of party leaders made by partisans of those same parties (matching partisanship with the leader in question)—the solid black line, therefore, represents average ratings of Republican leaders, as evaluated by Republican partisans. Similarly, the solid grey line represents average ratings of Democrat leaders, as evaluated by Democrats. Almost always, Republicans are more enthusiastic about their own party leader than are Democrats, with the exception of 2008 and 2012 (when Democrats were more enthusiastic about Obama than Republicans were about both McCain and Romney, respectively). The dashed lines represent evaluations of leaders by partisans of the opposing party (black dash represents evaluations of Republican leaders by Democrat partisans, and grey dash represents evaluations of Democrat leaders by Republican partisans).

Figure 10 fairly clearly shows a decrease in average evaluations of party leaders by opposing partisans. That is, both Democrats and Republicans have become more negative in their evaluations of the opposing party’s leader over time (especially among Republicans, whose average evaluations of Democratic leaders has dropped by about 0.4 on the 0, 1 scale). There are many jumps and drops across all four trend lines, but there has been less noticeable change in the evaluations of party leaders by members of their own parties (the evaluation of Democrat leaders by Democrats has become only slightly more positive over time, especially compared to evaluations of Republican leaders by Republicans which have become more negative between 1972 and 2016).

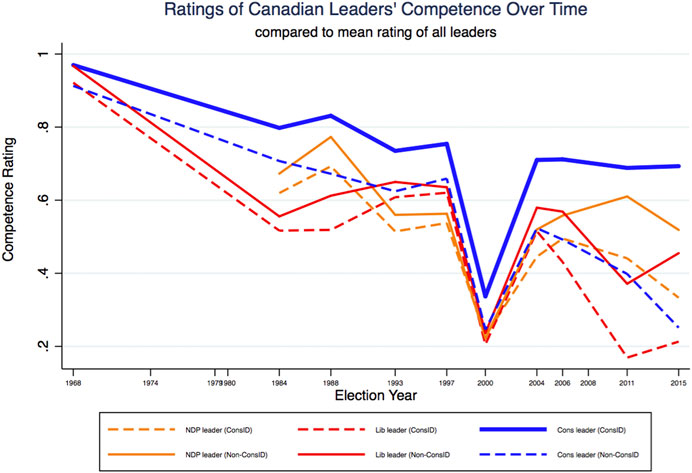

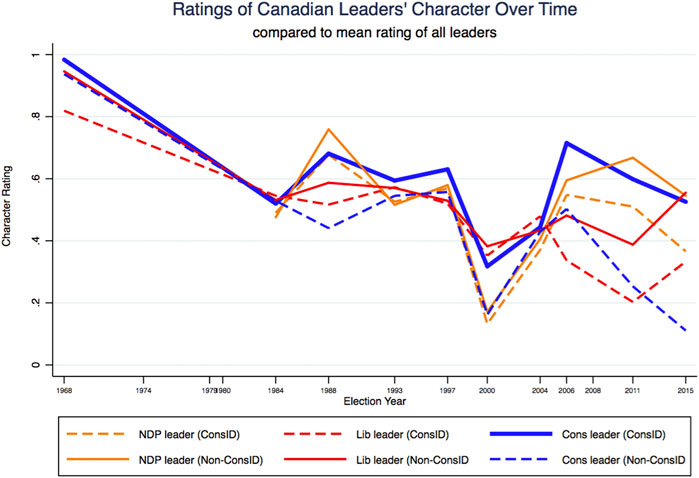

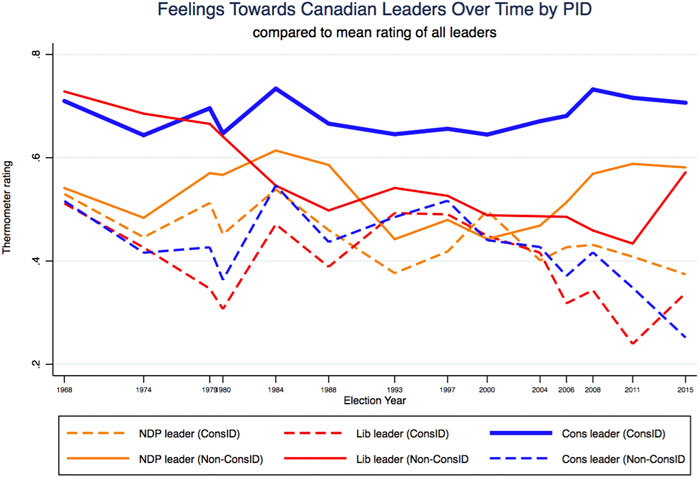

Figure 10 shows only the trend lines for a single country, the United States. I chose to present this country because of the clear downward trend seen in Figure 3 (impact of leaders on vote choice) as well as Figure 7 (ratings of party leaders over time). In both of these graphs, we see that leaders matter less to vote choice over time, and we see that leaders are perceived Figures 11–13 by voters. Similar dynamics emerge in the Canadian data as well. Figures 11–13 depict average ratings across partisan groups for 1) leaders’ competence; 2) leaders’ character, and then 3) overall “feelings” as measured by the thermometer.

Identifying polarization dynamics in a multiparty system (such as Canada) is more challenging than looking at longitudinal graphs in a two-party system (like United States), but we can see fairly clearly that there are some changes over time. As of the 2004 Canadian election, partisans began to be more polarized in their evaluations of leaders’ competence: partisans viewed their own leaders more favourably and became more negative about the leaders of the opposing parties (the gap between the solid lines and dashed lines increased between 2004 and 2015). A similar dynamic can be seen in perceptions of leaders’ character, as seen in Figure 12. Figure 12 shows a widening gap that emerges in 2004 and continues to the present: out-partisans are more negative about party leaders’ personality traits, including both character and competence, in recent decades than they were in the past.

Figure 13 provides a more direct comparison with the American data presented in Figure 10, because it tracks thermometer ratings over time. Again, I note that it is messy to look at the ratings of leaders in a multiparty system in comparison to a two-party system. There are a lot of lines in the graph making it challenging to interpret. There is clear indication, however, that voters have become more polarized over time in their assessments of party leaders. They feel more warmly towards their own leaders in general (especially when we look at Conservative partisans, who rarely change their views towards their leaders over time), while partisans of other parties evaluate those same leaders more negatively, and, over time, increasingly more negatively. The gap widens most by 2015 for feelings towards the Conservative leader (largely because Conservative partisans are so committed to viewing their leader positively), but also widens substantially for evaluations of the Liberal and NDP party leaders over time. This is most visible for evaluations of the NDP leaders after 2004, while the polarization between in-partisans and out-partisans’ evaluations of the Liberal leader was large in the 1960 and 1970s, decreased, and then increased again after 2004.

Polarization between in- and out-partisans may help to explain why we are not seeing a great deal of evidence of personalization of politics. If partisans are more protective of their own leaders and more hostile towards opposing leaders, this may have an impact on the extent to which leaders influence vote choice. More research is needed, including 1) research that looks at the dynamics of polarization across other countries; and 2) research that seeks to better understand the translation of perceptions of leaders to vote choice among partisan groups. This is the logical next step. Reiljan (2020) has made important inroads into understanding affective polarization in Europe, and Wagner (2021) has pushed the discussion one step further by challenging the ways in which we can measure polarization in multiparty systems. Extending their work to better assess the role of polarization in relation to personalization is likely to be quite fruitful in better understanding the dynamics of personalization.

Conclusion: Personalization and the Factors Contributing to the Importance of Party Leaders

This paper provides a starting point, and it makes it clear that cross-national, longitudinal research is important (as also demonstrated in Garzia’s et al. (2020) work) for determining the impact of party leaders in elections, and in particular, for determining whether or not personalization of politics is taking place. The results presented in this paper are inconclusive, but they do not uncover a great deal of evidence in favor of the increasing importance of party leaders. In fact, the data suggest that party leaders have always been important, and that they may be becoming less important over time.

It is not entirely obvious that personalization as a process is underway on a global level, at least not based on data from these five countries over time. More research is needed, research that is comparative in scope and longitudinal in its analysis. Polarization needs to be considered seriously as a factor influencing our understanding of how voters perceive leaders and their personality traits, and we must incorporate this variable into our analyses of the impact of leaders on election results over time.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation. Data and documentation for each country's election studies can be found here: Canada: http://www.ces-eec.ca/, United States, https://electionstudies.org/, New Zealand: http://www.nzes.org/, Australia: https://australianelectionstudy.org/, Britain: https://www.britishelectionstudy.com/.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was not provided because use of secondary data. Assuming PIs had informed consent when collecting data.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge the incredibly helpful research assistance of Hannah Breckenridge, Holly Fox, Clare Noxon, and Brooke Steinhauer. I would also like to thank Scott Matthews and Rüdiger Schmitt-Beck for conversations about this work during its earliest stages, as well as the two anonymous reviewers for very helpful feedback and suggestions. All errors are my own.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2021.660607/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1Data from subsequent elections are now available but are not integrated in the analyses presented here.

2Codebook and syntax available from the author upon request. In addition to collecting perceptions of leaders’ personality traits and overall “feelings” towards leaders (where available), I coded partisanship, issue attitudes, ideological self-placement, and demographic variables to allow for cross-national and longitudinal analysis.

3To be clear: I am not suggesting that I believe millennials are frivolous. I also do not believe that leader evaluations are frivolous and less important than evaluations of the state of economy.

4I would like to thank Reviewer 2 for suggesting this consideration for why assessing Anglo-Westminster democracies is particularly fruitful.

5A complete list of variables, and syntax, is available from the author upon request. The statistical models presented in this paper are quite minimalist, in order to maximize the number of respondents in the analyses. Once we begin to add in perceptions of the economy, attitudes about issues, and other opinion questions into our models it becomes much more difficult to conduct the research at a cross-national level, as so many questions are not asked consistently or regularly.

6Missing from this analysis is the role of media coverage in explaining personalization. This paper is part of a larger project (more countries, more data) assessing the role of party leaders over time, and the media portion will be assessed in a second paper. In this paper, I only assess voters’ attitudes towards leaders and other attitudinal variables that may influence the importance of perceptions over time.

7The decision to display the impact of leaders on vote for the top two parties only is significant, as many of these countries have multiparty systems and parties outside the top two are also competitive, and by not showing the effects of leaders on vote for all parties, it is possible that we are missing part of the story. Indeed, Michel et al. (2020) suggest that voters of Right-wing Radical parties are more likely to focus on leaders, and usually these parties are not part of the top-two. It is conceivable that mainstream parties have been losing support to these other parties because of the role of party leaders, in which case, assessing a fuller set of parties is valuable. I do not disagree that a fulsome evaluation is important and valuable. A complete picture is beyond the scope of this paper (or, really, any paper), and past research shows that perceptions of party leaders have a much larger influence on vote choice for major parties (Bittner, 2011), and that personalization in particular appears to be primarily concentrated among major parties (Garzia et al., 2020).

8Models were similar across time and space. Dependent variable is vote for the party (binary, 1 = vote for party, 0 = vote for other), and independent variables include sex, marital status, education, employment status, age, partisanship, evaluations of leaders. A model was run for each of the top two parties in each election year in each country, and marginal effects for each model were calculated and plotted. Please see supplementary material for full results of regression analyses.

9Because I include multiple countries and years in this analysis, I opted for a simple binary logistical model rather than running multinomial logit models with vote for multiple parties as dependent variables. Party systems and parties vary across countries and over time, making pooled comparative analysis challenging. This paper does not pool data across countries, but runs separate models for each party/election, making analysis simpler. Most (but not all) of the election studies included in the analyses collected perceptions of leaders’ personalities for the leaders of the two major parties. More frequently collected were “feelings” thermometer ratings towards party leaders, of the top two parties, but also the leaders of other major parties. Where possible, models included perceptions of multiple leaders as control variables (e.g., models for Canada and Britain include evaluations of NDP leaders’ traits and Lib-Dem leaders’ traits, and NZ models with thermometer ratings as independent variables include thermometer ratings for the Labour Party, National Party, Alliance/Progressive Parties, and NZ First Party) although only the models where dependent variables were the top two parties are shown.

10Because traits data have been collected less frequently over time and across space, here I examine the impact of thermometer ratings as well, to maximize the number of countries and years included in the analysis. They are presented separately, and in models graphed on the left side, thermometer ratings are not included and in models graphed on the right side, personality traits are not included. The year is presented on the x-axis and may be different in the traits model in comparison to the thermometer model, because these two types of questions about leaders were often found in different years. Please see supplementary material for a detailed description of inclusion of leaders traits and thermometer ratings in the election studies used in this paper.

11I replicated the analyses without the addition of leader evaluations of other leaders in the models. This was done to check the robustness of the models against the possibility that the ebbs and flows in the effects of leaders on vote choice are more closely linked to the idiosyncrasies of survey researchers and the questions/parties/leaders they choose to include in the survey instrument in a given year. Although these replication tables and charts are not included in the appendix, they are available from the author upon request, and suggest that keeping the number of leaders as IVs constant across models does not substantively change the patterns seen across time and space. Further, the inclusion of other leaders in the model as independent variables appears to make the models more robust, providing further that voters assess them in relation to one another.

12Thank you to one of my anonymous reviewers for suggesting Brexit as a possible explanation.

13The centre-left category includes the Liberal Party (Canada), the Labour Party (United Kingdom), the Democratic Party (United States), the Labor Party (Australia), and the Labour Party (New Zealand), while the conservative category includes the Conservative Party (Canada), the Conservative Party (United Kingdom), the Republican Party (United States), and the Liberal Party (Australia). The centre-right category includes the National Party (New Zealand). These parties are placed together in categories according to placement along two dimensions (taxes versus spending) and social liberalism, following Benoit and Laver’s (2006) classification system, as employed in Bittner (2011).

References

Aarts, K., Blais, A., and Schmitt, H. (2011). Political Leaders and Democratic Elections. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Abramowitz, A. I., and Steven, W. (2016). The Rise of Negative Partisanship and the Nationalization of U.S. Elections in the 21st Century. Electoral Stud. 41, 12–22. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2015.11.001

Balmas, M., Rahat, G., Sheafer, T., and Shenhav, S. R. (2014). Two Routes to Personalized Politics. Party Polit. 20 (1), 37–51. doi:10.1177/1354068811436037

Bartels, L. M. (2002). “The Impact of Candidate Traits in American Presidential Elections,” in Leaders’ Personalities and the Outcomes of Democratic Elections. Editor A. King (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Bean, C. (1993). The Electoral Influence of Party Leader Images in Australia and New Zealand. Comp. Polit. Stud. 26, 111–132. doi:10.1177/0010414093026001005

Benoit, K., and Laver, M. (2006). Party Policy in Modern Democracies. London, NY: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203028179

Bittner, A. (2013). “Coping with Political Flux: The Impact of Information on Voters’ Perceptions of the Political Landscape, 1988-2011,” in Parties, Elections, and the Future of Canadian Politics. Editors A. Bittner, and R. Koop (Vancouver: UBC Press).

Bittner, A. (2018). Leaders Always Mattered: The Persistence of Personality in Canadian Elections. Elect. Stud. 54, 297–302. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2018.04.013

Bittner, A. (2011). Platform or Personality?: The Role of Party Leaders in Elections. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brettschneider, F., and Gabriel, O. W. (2002). “The Nonpersonalization of Voting Behavior in Germany,” in Leaders’ Personalities and the Outcomes of Democratic Elections. Editor A. King (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Butler, D., and Stokes, D. (1974). Political Change in Britain: The Evolution of Electoral Choice. 2nd ed. London: MacMillan. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-02048-5

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E., and Stokes, D. E. (1960). The American Voter. Chicago: John Wiley & Sons.

M. Costa Lobo, and J. Curtice (Editors) (2014). Personality Politics?: The Role of Leader Evaluations in Democratic Elections. Oxford: OUP Oxford.

Cummings, W. (2017). Millionaire to Millennials: “Your Avocado Toast Addiction is Costing you a House,” in USA Today. May 16 https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/2017/05/16/millionaire-tells-millennials-your-avocado-addiction-costing-you-house/101727712

Curtice, J., and Lisi, M. (2014). “The Impact of Leaders in Parliamentary and Presidential Regimes,” in Personality Politics?: The Role of Leader Evaluations in Democratic Elections. Editors M. Costa, and C. John (Oxford: OUP Oxford), 63–86.

Da Silva, F. F., Garzia, D., and De Angelis, A. (2019). From Party to Leader Mobilization? The Personalization of Voter Turnout. Party Politics, June 12. doi:10.1177/1354068819855707

Dalton, R., Flanagan, S., and Beck, P. (1984). Electoral Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies: Realignment or Dealignment? Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Dalton, R., McAllister, I., and Wattenberg, M. P. (2000). “The Consequences of Partisan Dealignment,” in Parties without Partisans: Political Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies. Editors R. Dalton, and M. P. Wattenberg (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

De Angelis, A., and Garzia, D. (2016). Partisanship, Leader Evaluations and the Vote: Disentangling the New Iron Triangle in Electoral Research. Comparative European Pol. 14 (5), 604–625. doi:10.1057/cep.2014.36

Franklin, M. (1992). “The Decline of Cleavage Politics,” in Electoral Change: Responses to Evolving Social and Attitudinal Structures in Western Countries. Editors M. Franklin, T. T. Mackie, and H. Valen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Garzia, D., and Da Silva, F. F. (2021). Negative Personalization and Voting Behavior in 14 Parliamentary Democracies, 1961–2018. Electoral Stud. 71, 102300. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102300

Garzia, D., Ferreira da Silva, F., and De Angelis, A. (2020). Partisan Dealignment and the Personalisation of Politics in West European Parliamentary Democracies, 1961–2018. West European Politics, 1–24. doi:10.1080/01402382.2020.1845941

Gidengil, E., and Blais, A. (2007). “Are Party Leaders Becoming More Important to Vote Choice in Canada?,” in Leadership, Representation, & Elections: Essays in Honour of John C. Courtney. Editors H. J. Michelmann, D. C. Story, and J. S. Steeves (Toronto: University of Toronto Press). doi:10.3138/9781442684706-005

Johnston, R. (2006). PARTY IDENTIFICATION: Unmoved Mover or Sum of Preferences? Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 9, 329–351. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.9.062404.170523

Johnston, R. (2002). “Prime Ministerial Contenders in Canada,” in Personalities and the Outcomes of Democratic Elections. Editor A. King (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Kaase, M. (1994). Is There Personalization in Politics? Candidates and Voting Behaviour in Germany. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 15 (4), 211–230. doi:10.1177/019251219401500301

Karvonen, L. (2009). The Personalization of Politics: A Study of Parliamentary Democracies. Colchester, UK: ECPR Press.

Kinder, D. R., and Fiske, S. T. (1986). “Presidents in the Public Mind,” in Political Psychology: Contemporary Problems and Issues. Editor M. G. Hermann (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass).

Kinder, D. R., Peters, M. D., Abelson, R. P., and Fiske, S. T. (1980). Presidential Prototypes. Polit. Behav. 2 (4), 315–337. doi:10.1007/bf00990172

Kinder, D. R. (1978). Political Person Perception: The Asymmetrical Influence of Sentiment and Choice on Perceptions of Presidential Candidates. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 36, 859–871. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.36.8.859

King, A. (2002). Leaders’ Personalities and the Outcomes of Democratic Elections. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kircheimer, O. (1966). “The Transformation of the Western European Party System,” in Political Parties and Political Development. Editors J. LaPalombara, and M. Weiner (Princeton: Princeton University Press).

Lipset, S. M., and Rokkan, S. (1967). “Cleavage Structures, Party Systems and Voter Alignments: an Introduction,” in Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives. Editors S. M. Lipset, and S. Rokkan (New York: Free Press).

McAllister, I. (1996). “Leaders,” in Comparing Democracies: Elections and Voting in Global Perspective. Editors L. LeDuc, R. G. Niemi, and P. Norris (Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Inc).

Michel, E., Garzia, D., Da Silva, F. F., and De Angelis, A. (2020). Leader Effects and Voting for the Populist Radical Right in Western Europe. Swiss Pol. Sci. Rev., 26 (3), 273–295.

Mughan, A. (2000). Media and the Presidentialization of Parliamentary Elections. Basingstoke: Palgrave. doi:10.1057/9781403920126

Peterson, D. A. M. (2004). Certainty or Accessibility: Attitude Strength in Candidate Evaluations. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 48, 513–520. doi:10.1111/j.0092-5853.2004.00084.x

Poguntke, T., and Webb, P. (2005). The Presidentialization of Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/0199252017.001.0001

Rahat, G., and Sheafer, T. (2007). The Personalization(s) of Politics: Israel, 1949-2003. Polit. Commun. 24 (1), 65–80. doi:10.1080/10584600601128739

Rahn, W. M., Aldrich, J. H., Borgida, E., and Sullivan, J. L. (1990). “A Social-Cognitive Model of Candidate Appraisal,” in Information and Democratic Processes. Editors J. A. Ferejohn, and J. H. kuklinski (Urbana: University of Illinois Press).

Reiljan, A. (2020). Fear and Loathing across Party Lines' (Also) in Europe: Affective Polarisation in European Party Systems. Eur. J. Pol. Res. 59 (2), 376–396. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12351

Wagner, M. (2021). Affective Polarization in Multiparty Systems. Electoral Stud. 69, 102199. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102199

Wattenberg, M. P. (1984). The Decline of American Political Parties, 1952–1980. Boston: Harvard University Press.

Keywords: personalization, polarization, party leaders, leader effects, voters

Citation: Bittner A (2021) The Personalization of Politics in Anglo-American Democracies. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:660607. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.660607

Received: 29 January 2021; Accepted: 07 June 2021;

Published: 02 July 2021.

Edited by:

Scott Pruysers, Dalhousie University, CanadaReviewed by:

Diego Garzia, University of Lausanne, SwitzerlandFrederico Ferreira Da Silva, University of Lausanne, Switzerland

Copyright © 2021 Bittner. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Amanda Bittner, YWJpdHRuZXJAbXVuLmNh

Amanda Bittner

Amanda Bittner