Abstract

Many studies have examined whether citizens prefer direct or stealth democracy, or participatory democratic processes. This study adds to the emerging literature that instead examines the temporal aspect of citizens’ process preferences. We use a survey with a probabilistic sample of the Finnish voting-age population (n = 1,906), which includes a measure of the extent to which citizens think democratic decision-making should maximize welfare today or ensure future well-being. Calling this dimension of democratic process preferences future-oriented political thinking, we demonstrate that people hold different but consistent views regarding the extent to which democratic politics should balance between present and future benefits. We find that future-oriented political thinking is linked to general time orientation, but the linkage varies across respondent groups. Politically sophisticated individuals are less future-oriented, suggesting that intense cognitive engagement with politics is linked with a focus on present-day politics rather than political investment in the future.

Introduction

In the complex contemporary world, many of the most acute political problems have consequences that extend far into the future and cannot be discussed and decided upon in terms of the present alone. However, democracies are not always particularly good at governing for the long-term. Part of the problem lies in democratic institutions, whose inner logic is based on short electoral cycles, making them far from ideal for making long-term policy investments (Jacobs, 2011; MacKenzie, 2013). Another part of the problem, which this study focuses on, concerns the political time perspectives of citizens. Where would citizens prefer to put the emphasis of democratic decision-making when it comes to balancing between maximum welfare today and future well-being? In this article, we argue that in order to fully grasp the nature and extent of shortsightedness in democratic decision-making, we also need to understand the temporal component in political attitudes.

This forces the question of when into the research agenda (also Jacobs, 2016). There is an extensive empirical literature that examines what democratic publics want, both in terms of what type of democracy (e.g., Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, 2002) and what type of policies people desire (e.g., Wlezien, 2004). There is an equally vast literature on how public attitudes are formed (e.g., Toff and Suhay, 2018). However, the question of where the temporal focus of citizens’ political preferences is still an emerging area of research.

In psychological literature, time perception, i.e., “the degree to which one reflects upon the past, is centered in the present, or anticipates the future” (Lennings, 2000, p. 40), has been shown to significantly affect human behaviour as well as to vary between individuals (e.g., Strathman et al., 1994). This understanding, however, has been slow to take root among political scientists, whose focus has perhaps been more on who gets what and how, but not on when.

While previous research has focused on policy-specific preferences regarding future-oriented thinking in politics, in this study we examine future-oriented thinking in terms of procedural preferences. Although striking a balance between present and future needs is at its most concrete in the context of specific policies, democratic governance is also a process, which focuses more on some aspects and less on others. As previous research on democratic process preferences shows, people hold fairly stable attitudes regarding how they think democratic governance should be organized. Much of the focus in this literature has been on popular support for different institutional arrangements, such as direct democracy versus representative democracy (e.g., Bowler et al., 2007; Bengtsson and Mattila, 2009). In this study, we investigate the extent to which people prefer a democratic process that focuses on the future versus the present. We seek to contribute to the literature on democratic process preferences by suggesting that democratic process preferences also include a temporal dimension. To the more specific literature on temporal political preferences, we wish to make more particular contribution by suggesting that in addition to policy-specific preferences, it is valuable to also address the more general process preferences.

To this end, we utilize a question battery designed for measuring the extent to which people think democratic decision-making should focus on the present versus the future and examine individual-level determinants of that preference. Examining what we call “future-oriented political thinking,” our findings underscore the relevance of analysing political attitudes in terms of temporality. We find that people hold different but consistent views regarding the extent to which democratic politics should concentrate on present or future wellbeing. The findings demonstrate that personality-related determinants, attachment to politics and political ideology are more strongly connected to differences in temporal preferences than life-cycle related determinants.

Citizens and Democratic Myopia

The future manifests itself in different ways in democratic decision-making. On the level of policy-making, certain choices have, or at least might have, consequences that reach far into the future. The temporal horizon of such issues varies almost infinitely. Choices that are made regarding, for example, the storage of nuclear waste has significance so far beyond the human life span that no democracy or individual decision-maker can truly grasp the temporal aspect of such a decision. In less extreme situations, a “long-term policy” might be understood as something that could have consequences beyond the current electoral cycle, and probably stretch at least some decades into the future. Most of what we know about the handling of such issues in democratic decision-making comes from studies targeting a specific policy domain, such as environmental or pension policy or public debt (MacKenzie, 2013; 5ff; also; Jacobs, 2016). In this study, we do not examine policy preferences, but rather the underlying question of where, in a normative sense, citizens think that the emphasis of democratic choices should be, in maximizing present or future wellbeing. This approach sidesteps the difficult, or perhaps impossible, question of defining exactly how far in the future a political choice must extend in order to be considered “long-term.” Hence, we focus on the normative foundations behind democratic process preferences and leave the question of just how far the future really is outside the scope of the analysis.

The mainstream of previous scholarship concerning the temporal dimension of democracy has dealt with the institutional causes of (alleged) democratic myopia. These studies address the basic dynamic in democratic policy-making, where politicians want to maximize likelihood for re-election and investing in uncertain future well-being is risky, especially if it means costs for voters today. Organized interest groups may be hard to overcome because they are determined to block reforms, which they feel will hurt their own interests (MacKenzie, 2013). Furthermore, future-oriented policy-making has extraordinarily high information costs, which causes problems for decision-makers, even if they are willing to bear the possible electoral costs for their choices (Jacobs, 2016).

Underlying these system-level explanations is the persistent discussion of voter myopia. It proposes that voters, or citizens more broadly, are shortsighted by nature and thus exert pressure on elected officials to make policies that produce benefits in the short-term, although politicians themselves might prefer more future-oriented policies. This argument builds on the premise that the ubiquitous human tendency to maximize short-term gains instead of investing in uncertain future benefits is also behind democratic myopia, because democracies are expected to serve the people’s current needs (Thompson, 2010). In this view, voter demands are seen as the root cause of democratic myopia.

Intuitively, it seems plausible that people are biased towards preferring immediate rewards, both in everyday life and in politics. Psychologists have demonstrated compellingly the human tendency to opt for short-term gains over delayed benefits and to prefer risk-avoidance over maximization of possible gains (Tversky and Kahneman, 1991). Risk-avoidance understandably emphasizes the present, because the future always carries risks due to uncertainty. In a similar fashion, political economists have discussed the occurrence of future discounting, which also refers to situations where individuals have (good) reasons to prefer immediate gains to protracted benefits. However, the extensive literature review by Frederick et al. (2002) finds inconclusive support for future discounting in the field of political economy, suggesting that perhaps the shortsighted tendencies are not quite as prevalent in political behaviour as might easily be assumed.

The claim that shortsighted citizens are a key factor behind democratic choices is more often taken as a given rather than empirically tested. The few studies that explicitly address the issue empirically, usually in the context of a specific policy choice, offer a mixed bag of results. It is widely held that elected representatives display risk-avoiding behaviour by trying to “avoid blame” instead of going for major policy wins, because they involve big electoral risks (Weaver, 1986). This seems like a response to the (assumed) risk-avoiding bias among voters. While risk-avoidance, according to psychologists, is biased towards the present, studies in political behaviour have indicated that the connection between risk avoidance and temporal preferences is mostly indirect. For example, the dominance of retrospective over prospective evaluations among voters is sometimes interpreted as supporting the idea that voter choices are typically shortsighted (e.g., Nannestad and Paldam, 2000), although as empirical evidence of democratic myopia this is, at best, incidental.

Thus far, the few explicit tests focused on policy preferences in specific choice contexts. Healy and Malhotra (2009) compared voter reactions to proposed investment in relief aid for natural disasters and in future natural disaster prevention. They reported conclusive voter support for the short-term option (immediate relief aid) instead of the long-term option (disaster prevention). The credibility of the finding rests only on the link between aggregated candidate support at the county level and the choice of investing in one of the two policy options for handling natural disasters. The broader question of whether citizen in general prefer policy-making that concentrates on present or on future policy benefits remains outside the authors’ scope.

Jacobs and Matthews (2012; 2017) examined the individual-level drivers of citizen preferences for short-term policy benefits in a series of tests with survey experiments and cross-sectional surveys. Based on nationally representative samples of the US voting age population, they did not find evidence of a “radically” myopic electorate (Jacobs and Matthews, 2012, p. 932). In their interpretation, the slight bias towards short-term policies stems from distrust rather than shortsightedness: not being able to trust politicians to deliver on long-term promises, people prefer the less uncertain short-term option (also Cai et al., 2020). Consequently, it seems that politicians’ fears of electoral retaliation for future-oriented policy-making could be excessive (Jacobs and Matthews, 2012). Instead of blaming impatient voters for democratic shortcomings in long-term policy-making, Jacobs and Matthews suggest that perhaps the focus should be on enhancing institutional trust among the public.

Attempting to address this issue, the same authors turned to studying how political institutions might facilitate the public’s trust in long-term policy commitments (Jacobs and Matthews, 2017). They designed survey and vignette experiments, which varied the decision-making institution (local government, United States federal government or military), to capture the effect of varying trust in different institutions. As expected, long-term policies received more popular support, when political institutions, which were perceived as more trustworthy by the people, introduced them.

To summarize, previous literature suggests that people perhaps are not particularly politically shortsighted, although they might show a slight preference for instantaneous benefits. The scarce evidence comes exclusively from the North American political context and experimental designs focusing on the choice between a short-term and a long-term policy option. The finding that temporal policy preferences largely depend on institutional trust highlights the context-dependency of the matter, calling for more evidence from other political realities.

Moreover, while extant research has studied policy choices in concrete political issues, the more general attitudes concerning the temporal focus of democratic decision-making and its determinants remain unexplored; putting concrete policies aside, how do people see the temporal trade-off between the present and the future in democratic decision-making? Where do they think the temporal focus of democratic governance should be? These questions pertain to the temporal aspect of democratic process preferences. By looking at the more general question of future-oriented thinking in terms of process, not policy-specific, preferences, we add another dimension to the field of study. Whereas weighing the temporal trade-offs of two or more policy options is unavoidably driven by whatever personal preferences regarding the specific policy question or the decision-makers a person has, our aim is to provide a more general understanding of what the public expects of democratic governance in terms of temporal emphasis. Whereas policy choices may also involve pragmatic considerations of what, for example, is possible to achieve technically in a given situation, we seek to tap into the normative ideas about what people think democratic governance should focus on—the present or the future. As previous research regarding democratic process preferences has shown (e.g., Bowler et al., 2007; Bengtsson and Mattila, 2009), people hold relatively coherent opinions about who should govern in a democracy and what the contours of the democratic process should look like. Our overarching aim is to examine the temporal aspect of those normative ideas about the democratic process.

Individual Differences in Future-Oriented Political Thinking

What factors could be associated with individual differences in future-oriented political thinking? We suggest three different explanatory pathways for why people feel differently about the temporal aspect in democratic decision-making.

Life Situation

Studying citizen perceptions of the time horizons of political decisions, a person’s current life situation and basic demographic markers seem a plausible category of determinants. First, having children might evoke moral responsibility for future well-being. An extensive sociological literature has documented the prevalence of intergenerational solidarity as a norm even in high-income societies where the number of children per woman is low (Graham et al., 2017). Longer life expectancies may strengthen the emotional and material commitments to the next generations even more. Having children could thus be expected to translate into more care and compassion, also for the future and not just for the present day. We used a measure asking respondents whether they have children or grandchildren, in order to capture the impact of having offspring (see Supplementary Appendix for variable codings).

Second, we may assume that personal economic and employment situations play a role in future-oriented political thinking, because support for future oriented policies requires willingness to bear costs in the present without immediate gains from policy-making. From the perspective of psychology, this is a challenging choice, because individuals are not particularly good at delaying personal gratification and biases prevent people from making trade-offs between their and others’ well-being (Wade-Benzoni et al., 2010). Therefore, people who are financially secure may be more prepared to demonstrate future-oriented thinking. We use a standard survey measure of gross annual income to measure personal economic situation.

Third, people’s subjective assessment of their health may also be an important determinant. Literature on health and political behaviour shows, for example, that poor health decreases trust towards political authorities (Mattila and Rapeli, 2018). We expect a similar effect in terms of political time orientation, because research suggests that political distrust increases shortsightedness in political behaviour (see below). Additionally, it seems likely that experiencing health problems makes a person more focused on immediate rather than future well-being. We rely on a widely used Likert scale on self-rated health assessment (Jylhä, 2009).

Fourth, although the direction is unclear, age might be associated with future-oriented political thinking. According to conventional scholarly wisdom, expected remaining lifetime should have a positive relation with risk-taking propensity (e.g., Bommier, 2006). Since the future is always more or less uncertain and therefore entails some degree of risk-taking, it seems likely that an orientation towards the future would also be stronger among the young in the political realm. In other words, the longer the expected future a person has, the more likely that person is to emphasize future-oriented politics. However, experimental evidence demonstrates that priming people to consider proximity of the end of their lives makes them think more about the future and about the legacy they are leaving for future generations (Wade-Benzoni et al., 2012), suggesting that future-oriented thinking could instead be most pronounced among the elderly.

Personality

Providing a different explanatory angle, personality is another possible source of individual differences in political behaviour (e.g., Mondak, 2010). In the current study, we are able to assess the impacts of two personality-related indicators, which could explain political time orientation, namely empathy and general time orientation. Empathy refers to an individual’s ability to understand other people’s views and feelings (Walter, 2012). Empathy contributes to prosocial behaviour and is thus a crucial component of social life (Cikara et al., 2011). While empathy affects how people judge other individuals and help others (Davis, 1994), it is also a product of social interaction with other people (Grönlund et al., 2017). Psychologists have unpacked the multidimensionality of empathy and often at least two dimensions are distinguished: affective empathy referring to reactions to other people’s emotions and cognitive empathy referring to perspective-taking (Walter, 2012).

Empathy could play a role in future-oriented political thinking because it forms the basis for an individuals’ ability to take the perspective of known and unknown others. This includes people who come after us, who are the main beneficiaries of long-term policies. As discussed earlier, future-oriented policy-making entails current taxpayers being willing to pay for initiatives that will concretely improve future living conditions. Understanding the feelings of others could therefore also increase willingness to support future well-being, even at the cost of current taxpayers. The survey included eight empathy items that were modified and translated into Finnish from the Questionnaire for Cognitive and Affective Empathy (QCAE: Reniers et al., 2011). These eight items measured the perspective-taking dimension of empathy.

Another obvious personality trait is general time perception. As has already been discussed, general time perception reflects the extent to which an individual lives in and focuses on the present or the future. It seems plausible that general time perception and the domain-specific time orientation related to politics are closely related; a person’s general outlook on time might also apply to their political thinking. In fact, it might be reasonable to think that a person’s time orientation in politics is merely an expression of their more general time perception. There are, however, good grounds to assume that the two could be separate concepts, despite close relation. A wealth of evidence demonstrates that the personal is surprisingly seldom political; research has typically shown that personal experience is not a strong predictor of political attitudes and behaviours (Egan and Mullin, 2012, p. 797). Based on this vast literature, it seems anything but clear that general time orientation and future-oriented political thinking would tap into the same conceptualizations. To test for this possibility, we employ a widely used scale developed by Gjesme (1975). It consists of six statements with Likert scale response alternatives [completely/partly (dis)agree]. The items have been formed into an additive index, where a higher score indicates a future-oriented frame of thinking.

Political Attachment

A third possible pathway leads from an individual’s political attachment to their future-oriented political thinking. We examine three aspects of political attachment: political interest, political (institutional) trust and ideological self-placement.

People who are strongly attached to politics are simply more interested in politics (Strömbäck and Shehata, 2010). As an important cursor of political attachment, political interest offers a link to peoples’ political identity, value orientations and their inclination to make political commitments. Political interest also leads people to assess the pros and cons of different political outcomes (Rebenstorf, 2004, p. 89). Moreover, political interest has been found to correlate positively with patience, suggesting that individuals who pay attention to politics are more oriented towards future rewards. For instance, based on their study of delayed gratification and voter turnout, Fowler and Kam (2006) argue that many campaign issues revolve around policies and political outcomes that lie way ahead in the future and may take years to implement. Voters who only care about the present may not be interested in paying attention to campaigns, but rather focus on other issues that have more immediate effects on their daily life (Fowler and Kam, 2006, p. 119). Similarly, it has been shown that politically interested individuals are more likely to follow news and have better political knowledge and self-efficacy, constructs that also correlate with future-oriented thinking (Beal, 2011, p. 26–29).

Previous research looking into temporality in policy preferences has highlighted the role of trust in politics and political institutions as a key factor affecting time orientation. The brief and conventional definition presents political trust as a basic evaluative orientation among citizens towards the government, which reflects perceptions of how well the government is operating according to people’s normative expectations (Hetherington, 1998, p. 791). While we acknowledge the scholarly debate concerning the dimensionality of political trust, it is beyond the scope of this article to engage deeply in this discussion. We follow Hooghe (2011), who argues that citizens’ trust judgements reflect the prevalent political culture within the political system they are part of; political trust can be conceptualized in terms of institutional trust, consisting of trust in the parliament, the judiciary system, public officials, politicians, political parties, the government and the European Union. With a remarkably high Cronbach’s alpha (0.935) and inter-item correlations ranging between 0.539 and 0.889, the unidimensional solution is strongly supported by the data in the current study.

Despite a lack of studies on institutional trust and political time orientation, there are several mechanisms that suggest a correlation between political trust and time orientation. First, trust in general is often seen as a resource for individuals to cope with situations of uncertainty (Misztal, 1996, p. 18). Since the future always involves a certain amount of uncertainty and risk, we predict that politically trusting individuals are more future oriented than those who are less trusting (Jacobs and Matthews, 2017; Cai et al., 2020). This mechanism likely depends on the fact that institutional trust influences public policy support. When citizens have high trust in the government, they are more likely to comply voluntarily with government policies and regulations (Tyler, 2006). Similarly, negative evaluations and political distrust reduce public support for government actions and motivations to accept implementation (ibid.). Therefore, it seems plausible that this connection becomes even more pronounced when policies and regulations lie far ahead in the distant and uncertain future. Second, it has been shown that political trust may have an effect on citizens’ risk-taking or risk-averse dispositions with regards to policy preferences. In their study on the effect of political trust on individual support for land-taking compensation in China, Cai et al. (2020) found that both risk-averse and risk-seeking individuals prefer one-time benefits to yearly dividends and/or pension payments. However, political distrust induces citizens to favour the one-time benefit-option, while trusting individuals are more accepting of compensations that lie further ahead in the future.

A person’s ideological disposition is another way to examine the foundations of political attachment. We rely on the standard self-placement on the left-right continuum, which has potential significance for future-oriented political thinking. Subjective political orientation is widely thought to pertain to risk-relevant characteristics (Choma et al., 2014, p. 1). Previous studies have demonstrated that political conservatives tend to be more threat-sensitive and risk-averse than liberals. According to Choma et al. (2014), political conservatism (vs. liberalism) is connected to two relevant components, namely preference for tradition (vs. social change) and acceptance (vs. rejection) of inequality, both of which pertain to threat-sensitivity. Moreover, the left-right dimension distinguishes people in terms of policy questions, which are salient for the preference between present and future wellbeing. Environmental issues are an obvious case in point. Leftist ideology is associated with more pro-environmental attitudes (e.g., Sargisson et al., 2020), which could plausibly be linked with a more future-oriented political outlook as well. In the context of Finnish politics, from where the data originate, the liberal-conservative distinction is captured by left-right self-identification. The reasoning is much the same as it is for conservative-liberal identification: individuals on the right are expected to be more traditionalist and conservation-motivated, whereas those who place themselves on the left are more open to change. These distinctions suggest that self-placement in the political left could be associated with a more future-oriented political outlook.

Measuring Future-Oriented Political Thinking

Several research literature domains touch on the issue of future-oriented political thinking but thus far it has avoided explicit assessment. For example, an extant political science literature has discussed citizens’ democratic policy preferences in terms of whether they prefer representative, participatory or stealth- or expert-driven democracy (e.g., Bengtsson and Mattila, 2009). The main focus in the literature is whether citizens prefer elections as the mechanism for delegation of power, or some other model. This research has not, however, addressed the normative ideas about where the temporal focus of democratic decision-making should be.

Another adjacent research area is the study of general time perceptions within psychology. It builds on the understanding that there is significant variation between individuals in terms of the extent to which people think about the future (e.g., Strathman et al., 1994). Psychologists have created different measures for studying various aspects related to time orientation, such as how long people’s planning horizons are (Lynch et al., 2010), how they perceive time in general (Gjesme, 1975) and how people reason about the future consequences of their actions (Strathman et al., 1994). Among other findings, the literature has demonstrated that future-oriented thinking has significant consequences e.g., for health-related behaviour (Seginer, 2009). However, the study of time perceptions has not yet properly extended into the realm of politics.

Similarly, futures studies have sought to empirically measure future-oriented thinking. The focus is on “future consciousness,” which refers to the extent that a person is aware of what “could or should happen in the future” or is cognitively engaged in linking the present with the future (Ahvenharju et al., 2018, p. 2). A thorough inventory of the literature in the field reveals a wide range of ideas and measures associated with future-oriented thinking, including personal traits such as optimism, courage and risk-taking, but none touches upon political attitudes (Ahvenharju et al., 2018, p. 6).

Despite useful conceptualizations, none of the existing measures is directly applicable to the study of political attitudes, or the more specific question of temporality in the democratic process. There are no standardized survey items or scales for measuring public attitudes towards the degree to which the democratic process should be “centered in the present, or anticipate the future” (Lennings, 2000, p. 40). There is, however, a question battery that is available in a survey (n = 1,906) conducted in Finland in 2019 among a probability sample, which was representative of the voting-age population. The survey respondents were recruited from a panel administered by Qualtrics so that the required quotas for age, gender and place of residence were filled. The resulting sample represented the voting-age population in terms of these characteristics. Qualtrics was also used as the software for conducting the survey online. We use the following survey items to construct an index of future-oriented political thinking:

The following statements describe politics on a general level. What do you think about them? (Completely agree; partly agree; partly disagree; completely disagree; cannot say)

1. Decision-makers must try to solve problems now that are still decades away in the future.

2. Today’s voters must be prepared to reduce their standard of living, if it is necessary for the well-being of future generations.

3. The world changes so fast that it does not pay to make political decisions that reach far into the future.

4. Voters’ demands are binding for decision-makers even when they might threaten the well-being of those who come after us.

5. Politics should try to solve contemporary societal problems, not future ones.

6. Future living conditions must be taken into account carefully in decisions made today.

7. Decision-makers must invest in solving future problems, even if it means that taxpayers face costs now.

8. Time will solve future problems, regardless of political decisions made today.

The battery was developed for the purpose of gauging individuals’ reasoning on temporality in democratic decision-making. Consisting originally of 12 items, we utilize the above eight items, which form the most robust composite variable. These eight items, include two types of statements. One set of items measure the basic question of whether the respondent believes, in general, that the future should be considered in present political decision-making (statements 1, 3, 5, and 8). From the perspective of democratic process preferences, these items ask respondents to state their preference regarding the extent to which democratic policies should focus on the present or on the future. The other items extend this purely normative discussion to measuring the extent to which the respondent thinks costs should be bore now even if policy benefits materialize in the future (statements 2, 4, 6, and 7). In order to be a genuinely general measure of temporal process preferences, as opposed to policy-specific, the item wordings are intentionally rather abstract.

We do not claim that these two dimensions are the only conceivable ones for measuring normative ideas about the temporal focus of democratic governance. However, what we do argue is that the two are highly relevant dimensions of those ideas in terms of democratic process preferences. The first one pertains to the overall value attached to the core question of what democratic governance should emphasize—the present or the future. The second one attempts to measure the same perceptions, but with a more concrete reference to those choices that the democratic process is forced to make between present and future wellbeing. In our attempt to measure a general attitude instead of a policy-specific one, we obviously do not anchor the questions in any policy sector. However, given that the democratic process exists to produce policies, the items also refer to this fact.

As all constructs aimed at measuring abstract ideas, also the above survey measure involves some dilemmas. First, from the respondents’ viewpoint, the topic is demanding and designing simple and understandable question wordings is difficult. Second, social desirability bias might cause respondents to over-emphasize future-orientation. To counter this potential caveat, some items have been designed to make it more acceptable to express less future-oriented political attitudes. Moreover, due to the long and sprawling theoretical trajectories from adjacent disciplines, conceptual boundaries easily get blurred. The items do not tap into a perception of political time in general, because they do not measure the degree to which a person reflects upon decision-making in the past (Lennings, 2000). In a similar fashion, the items are not either concerned with perceptions of the future itself, that is, how uncertain the respondents think future is or how they see themselves in the future. While these aspects are undoubtedly part of the bigger equation of how, all things considered, people perceive of temporality in politics, these items have a more constrained focus, namely that they examine the temporal aspect of democratic process preferences.

Admittedly, respondents are likely to also think in terms of policy areas when they answer the questions, and not purely in terms of a process. They might also have responded differently to some of the items depending on policy area, if the items had been anchored to specific policy issues. However, as the results reported below and in the Supplementary Appendix demonstrate, people hold consistent opinions about where the temporal focus of the democratic process should be, suggesting that the responses are not dramatically affected by underlying policy-specific considerations.

The battery was pre-tested using a sample consisting mainly of university students (n = 184). The pre-test showed high internal scale reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.705 and average inter-item covariance of 0.144. It was then included in the general population online survey (n = 1,906) described above. The survey showed even higher internal consistency across the items than the pre-test. Including only factors with an eigenvalue ≥1 and a cut-off ≥0.500 factor loadings, the items loaded on a single factor (see Supplementary Appendix Table A2). Both Cronbach’s alpha (0.844) and average inter-item correlation (0.453) suggest very high scale reliability. Further validity checks have been included in the Supplementary Appendix. In addition to high scalability, they demonstrate that the composite measure has the expected association with relevant policy-specific attitudes, further suggesting that the measure functions as intended.

Analysis

Table 1 below displays percentages of respondents who (dis)agree to the eight items that comprise the measurement of future-oriented political thinking.

TABLE 1

| Item | Completely/partly agree | Completely/partly disagree | Cannot say |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decision-makers must try to solve problems now that are still decades away in the future | 80.2 | 12.4 | 7.4 |

| Today’s voters must be prepared to reduce their standard of living, if it is necessary for the well-being of future generations | 54.9 | 35.3 | 9.8 |

| The world changes so fast that it does not pay to make political decisions that reach far into the future | 33.9 | 55 | 11.1 |

| Voters’ demands are binding for decision-makers even when they might threaten the well-being of those who come after us | 41.4 | 44.7 | 13.9 |

| Politics should try to solve contemporary societal problems, not future ones | 55 | 35 | 10.1 |

| Future living conditions must be taken into account carefully in decisions made today | 69.7 | 20.7 | 9.7 |

| Decision-makers must invest in solving future problems, even if it means that taxpayers face costs now | 52.8 | 36.1 | 11.1 |

| Time will solve future problems, regardless of political decisions made today | 30 | 56.9 | 13.2 |

(Dis)agreement to the statements (% of respondents, n = 1,752).

The responses demonstrate much disagreement across all items, suggesting that socially desirable responses biased towards future orientation are not very widespread. The broadest consensus is in the statement, “Decision-makers must try to solve problems now that still lie decades away in the future,” with 80% of respondents agreeing to the statement. Other items show more disagreement. On average, approximately 10% of the respondents declined to respond, suggesting that some respondents found it difficult to provide a meaningful response to the statements.

The one-dimensional result in the factor analysis (principal component analysis) allows us to safely use the factor scores, calculated using the regression method, as the dependent variable in the subsequent regression analyses. The factor scores represent the extent to which a respondent engages in future-oriented political thinking; for every respondent, a larger factor score means more future-oriented political thinking. The population mean is 0, which approximates the average placement of the surveyed individuals in terms of their future-oriented political thinking. Every step in the positive (negative) direction from 0 means one unit change in standard deviation from the population mean.

In order to examine the explanatory power of each possible type of explanation (life situation, personality, political attachment), we first entered each block containing the different explanatory models separately and then included them all in a full model. In addition to the theorized variables, we control for gender and education, which are among the most widely used “usual suspects” among individual-level determinants of political attitudes and behaviours. Given the cross-sectional nature of the data, our aim is to investigate associations between certain individual-level determinants and the dependent variable, rather than to suggest causal connections.

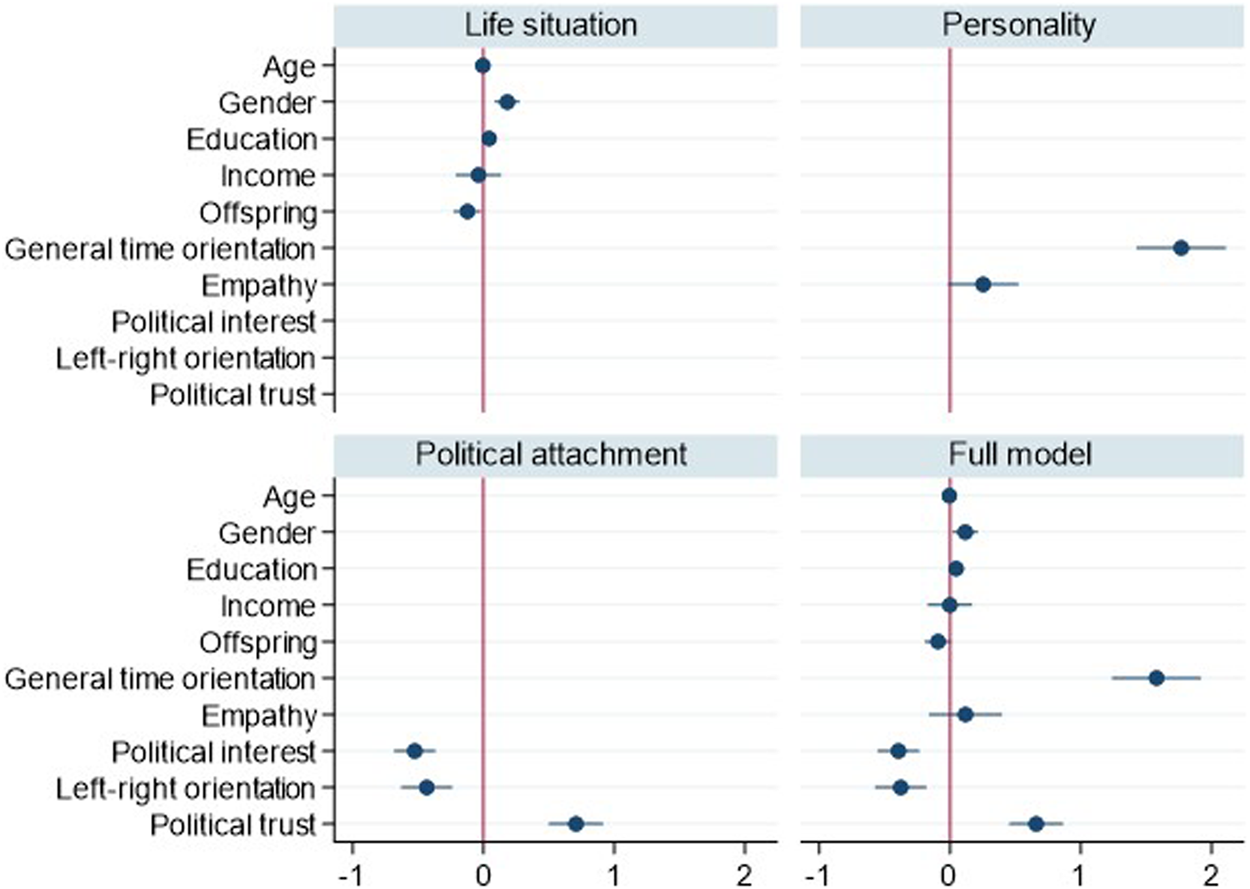

Figure 1 shows the point estimates for each explanatory variable and their confidence intervals (see Supplementary Appendix Table A4 for full results of the linear regression analyses). While the explanatory power of the models is modest, the picture is clear and every explanatory model seems to have some relevance. Income is the only variable in the life situation model, which shows no statistical significance. Young age, high education and good health all predict high future-oriented political thinking. The fact that younger individuals are more future-oriented politically is probably also captured by the negative coefficient for having offspring. Gender, which is included in the life situation model for practical reasons, shows that women are politically more future-oriented than men.

FIGURE 1

Determinants of future-oriented political thinking.

Empathy is unrelated to future-oriented political thinking. It seems that being sensitive to other people’s well-being and the ability to put oneself in the shoes of unknown others does not translate into a more future-oriented political outlook. From the perspective of long-term policy-making, this may also imply that public support of long-term policies does not require widespread empathy among the electorate. General time orientation, on the other hand, stands out as a particularly significant predictor in the personality model, suggesting that having a future-oriented outlook on life in general is associated with a similar orientation in the political realm.

All the variables included in the political attachment model demonstrate statistically significant relationships with future-oriented political thinking. As previous research suggests, political trust has a strong, positive association, which confirms that trust in the political system is linked with a willingness to place more emphasis in future-oriented politics. It seems that a lack of trust in the ability of political institutions and actors to deliver uncertain future benefits is associated with a less future-oriented political outlook. As expected, a leftist orientation predicts more future-oriented political thinking.

The negative coefficient for political interest means that politically engaged individuals are more focused on the present than on future-oriented politics. This stands in clear contrast with the above explained expectation, suggesting a very different interpretation. It seems that highly attached and partisan individuals are more likely to view politics in terms of shortsighted and partisan electoral politics, for which it is crucial either to get large benefits quickly when in government or to turn electoral fortunes around when in opposition. Such an approach leaves little room for long-term policy concerns, which could plausibly lead to the negative relationship with future-oriented political thinking that we are seeing in the results.

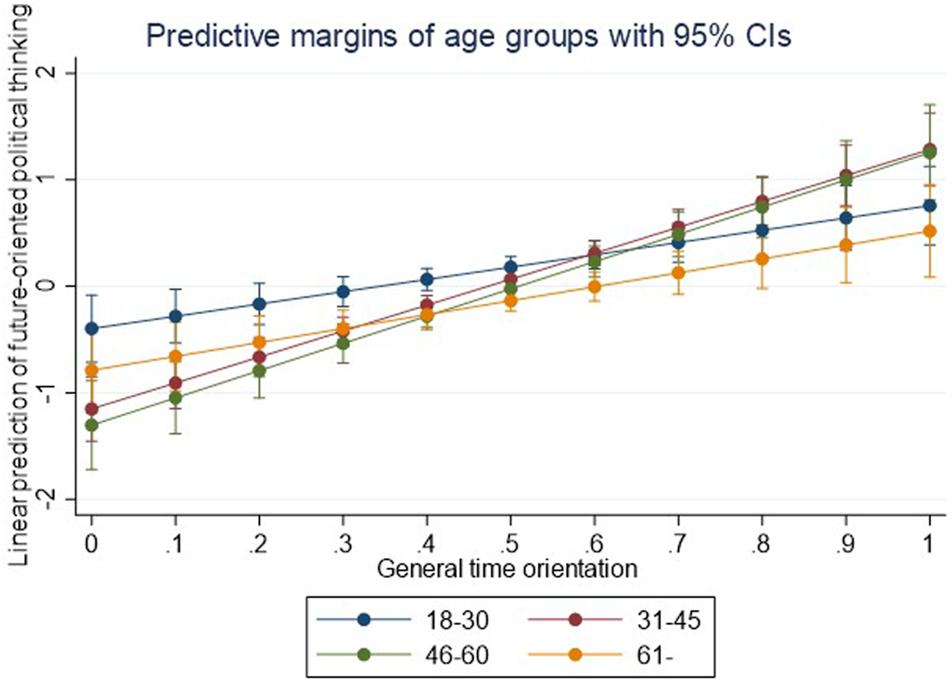

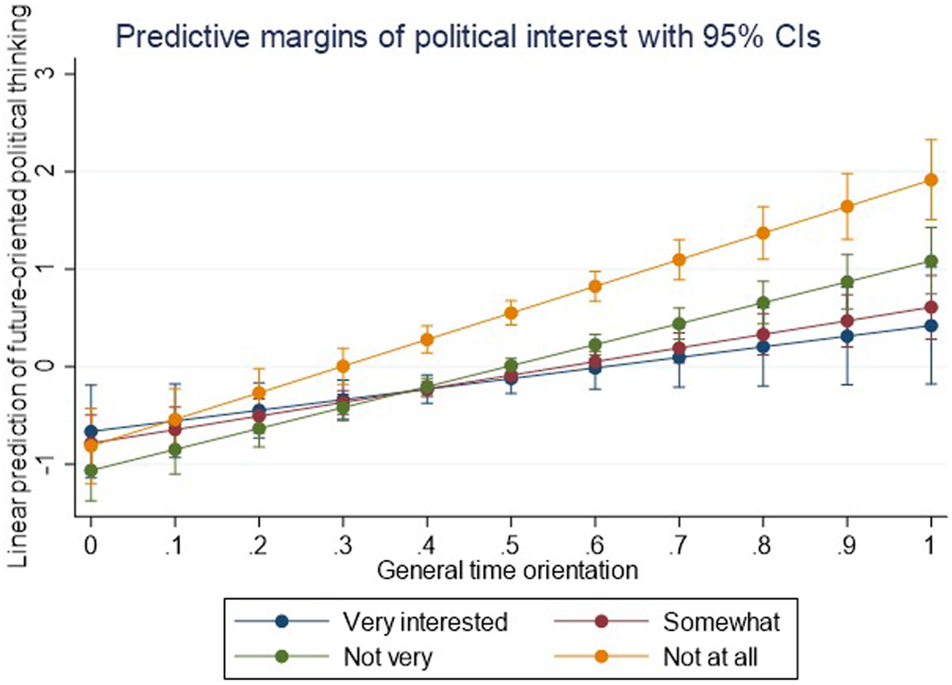

Despite a weak bivariate correlation with future-oriented political thinking, general time orientation stands out as the strongest single predictor. However, as Figure 1 shows, the large confidence intervals for general time orientation suggest considerable individual variation in terms of how strong this relationship is. Given that the two temporal orientations are also conceptually closely linked, we ran interactions with general time orientation and all the other explanatory variables to examine whether and how the strength of the association varies between respondent groups. In the figures below, we report the two instances where we found statistically significant interactions. The figures show the marginal effect of general time orientation on future-oriented political thinking across the respondent groups, when all other explanatory variables are set to their means.

A notable observation is that the impact of general time orientation differs between age groups (Figure 2). General time orientation is more closely connected to future-oriented political thinking among 31–45-year-olds and 46–60-year-olds than for the youngest and the oldest age groups. In other words, the youngest and the oldest age groups rely less on general time orientation when forming attitudes about future-oriented political thinking. As discussed, there are plausible reasons for why both youth and old age might be associated with more future-oriented thinking. Our findings suggest that people in both life situations have more nuanced thoughts about their temporal political preferences, although the young are more future-oriented than the elderly. People in middle-age, on the other hand, seem not to make much of a difference between their everyday temporal orientation and their temporal orientation in the political domain.

FIGURE 2

Impact of general time orientation on future-oriented political thinking across age groups.

General and political future orientations are much more closely connected among those who are not at all interested in politics (Figure 3). The contrast is most obvious with those who say they are very interested, suggesting that a strong cognitive attachment to politics is associated with a larger gap between general and political time orientations. In other words, people who follow politics closely, do not rely as much on general time perceptions to form their future-oriented political thinking. We interpret this as indicating that politically interested individuals hold well developed and nuanced political attitudes, which they (to some degree) keep separate from their attitudes in other realms. In the current case, this “pigeonholing” means that although people might be generally future-oriented, they might not be that politically—and vice versa.

FIGURE 3

Impact of general time orientation on future-oriented political thinking across levels of political interest.

To conclude, while general time orientation is the strongest predictor of future-oriented political thinking, the association is not the same across all relevant explanatory variables. Although a more future-oriented outlook on life for many people spills over to their attitudes toward temporality in democratic decision-making, this is not always the case and the bivariate correlation between the two is not particularly strong. Our interpretation is that the two are close, but nevertheless separate concepts and that the temporal aspect of democratic process preferences cannot be adequately captured through a measure of general time orientation.

Discussion

Several valuable efforts by scholars representing a diversity of research fields, such as economics, psychology and policy sciences, have focused on the temporal aspect of democratic politics from different analytical angles, such as (voter) rationality, risk-taking, cognitive biases and policy preferences. However, a more general understanding of citizen attitudes toward the temporal dimension of democratic decision-making has been lacking. In a world where the most important societal problems require long-term solutions, understanding what citizens think about the temporal dimension of democratic politics is essential. Moreover, assumptions about citizen myopia have not yet been very rigorously tested.

Empirically, a key takeaway for the study of democratic process preferences is that citizens have consistent and varying attitudes concerning the temporal dimension of democratic decision-making. The attitudes are one-dimensional across the eight-item survey measure and distinguishable from related concepts. This indicates that citizens not only care about how democratic power structures should be arranged institutionally, but they also hold consistent opinions on how democratic processes should balance between the needs of today and the prosperity of tomorrow. The when in democratic governance clearly matters for citizens.

We examined three plausible explanatory pathways for individual-level differences in future-oriented political thinking. The strong negative impact of age suggests at least a life-cycle related effect. It supports the idea that expected remaining lifetime is positively linked to emphasizing investments in future welfare. However, given that the data is cross-sectional, we cannot rule out the possibility that the age effect is in fact a generational effect and not an effect related to life situation. Political trust demonstrates the assumed positive relationship with future-oriented thinking. This confirms previous findings, according to which trust in political institutions to deliver on their promises is a key determinant of support for long-term policies. It seems obvious that the same mechanism is at work even when it comes to the underlying, normative ideals. Interestingly, the connection with political interest is negative, suggesting that individuals who are likely to follow politics closely, emphasize a focus on present-day well-being. A possible interpretation is that attentiveness to the partisan realities of democratic politics makes people value immediate policy rewards, because they are acutely aware of the fragility of long-term political commitments.

The finding that leftist ideology is connected to more future-oriented political thinking could be indicative of a deep ideological gap. The question, whether democracies ought to emphasize present-day or future wellbeing is, after all, a fundamental one and the left-right divide is a significant predictor of that preference, even when controlling for a host of other factors. It seems that ideological differences, which often manifest themselves on the level of actual policies, can partly also be attributed to different normative conceptions about what, temporally, should be the focus of democratic policy-making. The finding has potentially profound consequences for our understanding of the significance of ideology for democratic policy-making, but it calls for more investigation and evidence from other political contexts.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, general time orientation stands out as the variable with the most explanatory power. On average, people who are more future-oriented in their everyday lives are so even in the political realm. However, important differences between respondent groups also exist. General time orientation is a better proxy for future-oriented political thinking among people between the ages of 30–60 than for the youngest or the oldest age groups. Similarly, it is also a weaker predictor of future-oriented political thinking among politically attentive individuals. This suggests that people with a high cognitive capacity and a high engagement with politics are less likely to use general time orientation as a heuristic to express future-oriented political thinking. The findings thus support the idea that future-oriented political thinking should be distinguished from general time orientation—both conceptually and empirically.

It is also interesting to note the insignificance of income and empathy, both of which according to existing research are plausible drivers of future-oriented political thinking. One explanation may be that standard psychological indices fail to capture empathy towards future generations that are a very specific, abstract type of out-group in current societies. The impact of having (grand)children also had only a moderate, negative impact. This also may partly depend on measurement, but these observations nevertheless give the impression that factors related to personality and political attachment seem more important than life-cycle related determinants. Overall, the findings demonstrate understandable linkages about the way people reason about the temporal aspect of politics. Broadly speaking, the findings support one of the most fundamental insights which have emerged from the research on attitude formation, that personal life circumstances often have a surprisingly negligible impact on political attitudes (Egan and Mullin, 2012). Instead, in the case of future-oriented political thinking, the most important explanations seem to be personality differences and a person’s cognitive attachment to politics, including their ideological disposition.

For the more specific field of research concerned with the temporal dimension of democracy, the primary implication of the findings is that citizen myopia, which forces policy-makers to take shortsighted decisions, may not be as severe a problem for democracy after all. The assumption about widespread myopia may be an overstatement and, to some degree, an inaccurate picture of the citizenry. Many citizens agreed to statements describing a future-oriented style of democratic politics and there are systematic and understandable individual-level differences in the degree to which they do so. Studying the temporal aspect of political attitudes, therefore, seems like a meaningful exercise, although it has largely been neglected by mainstream scholarship on political attitudes. The temporal dimension of democratic politics should feature heavily on researchers’ agenda now that the solutions to the most pressing political problems require sacrifices in the present day in order to secure benefits in the future. When these political decisions that ensure well-being in the future are made, the crucial question becomes how legitimate they are considered by the public at large and current generation. Understanding the role that future plays in citizens’ political thinking may help us anticipate and solve legitimacy deficits of future-oriented policies.

The extent to which our survey measure and findings are replicable across national contexts remains to be examined. While some important predictors of future-oriented political thinking undoubtedly remain outside our empirical scope, subsequent research should also revisit the role of empathy more thoroughly. What distinguishes future-oriented political thinking from personal future orientation is the fundamentally collective nature of the former. Our findings that perspective-taking and general feelings towards outgroups are not associated with future-oriented political thinking could, therefore, imply that future-oriented political thinking is a fairly individualistic attitude or alternatively, that solidarity towards future generations operates via different causal mechanisms than general empathy. Furthermore, our measures tracked citizens’ attitudes towards the political present and the future, but there are studies suggesting that understanding retrospective viewpoints also increases support for long-term policies (Nakagawa et al., 2019). Citizens’ perceptions of the political past therefore remain another open question, which research into political time orientations should examine.

While we have argued and showed that future-oriented political thinking is normatively desirable and an empirically measurable concept, the question of how to foster it remains outside the scope of this article. There is some evidence that citizen deliberation in so called mini-publics can increase consideration of future generations’ perspectives in long-term planning (Kulha et al., 2021; MacKenzie and Caluwaerts, 2021), but the role of political socialization or education, for example, remains to be studied.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: “The Finnish Social Science Data Archive.”

Author contributions

LR initiated the writing of the article, conducted the analyses, wrote many parts of the manuscript and compiled others’ contributions to form a complete manuscript. He is the first author. The others are all second authors, with equal contributions. MB contributed to the planning of the manuscript and wrote some parts of the theoretical discussion and the concluding discussion. MJ contributed to the planning of the manuscript and wrote some parts of the theoretical discussion and the concluding discussion. VK was heavily involved in developing the survey measurement used in the analysis and contributed also to planning this article. All authors commented the whole manuscript on several occasions.

Funding

This work was supported by the Strategic Research Council of the Academy of Finland under Grant 312676 and by the Åbo Akademi University Foundation grant to the Future of Democracy Centre of Excellence.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2021.692913/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Ahvenharju S. Minkkinen M. Lalot F. (2018). The Five Dimensions of Futures Consciousness. Futures104, 1–13. 10.1016/j.futures.2018.06.010

2

Beal S. J. (2011). The Development of Future Orientation: Underpinnings and Related Constructs. PhD Thesis. Nebarska: University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

3

Bengtsson Å. Mattila M. (2009). Direct Democracy and its Critics: Support for Direct Democracy and 'Stealth' Democracy in Finland. West Eur. Polit.32 (5), 1031–1048. 10.1080/01402380903065256

4

Bommier A. (2006). Uncertain Lifetime and Intertemporal Choice: Risk Aversion as a Rationale for Time Discounting. Int. Econ. Rev47 (4), 1223–1246. 10.1111/j.1468-2354.2006.00411.x

5

Bowler S. Donovan T. Karp J. A. (2007). Enraged or Engaged? Preferences for Direct Citizen Participation in Affluent Democracies. Polit. Res. Q.60 (3), 351–362. 10.1177/1065912907304108

6

Cai M. Liu P. Wang H. (2020). Political Trust, Risk Preferences, and Policy Support: A Study of Land-Dispossessed Villagers in China. World Dev.125, 104687–104712. 10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104687

7

Choma B. L. Hanoch Y. Hodson G. Gummerum M. (2014). Risk Propensity Among Liberals and Conservatives. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci.5 (6), 713–721. 10.1177/1948550613519682

8

Cikara M. Botvinick M. M. Fiske S. T. (2011). Us versus Them. Psychol. Sci.22 (3), 306–313. 10.1177/0956797610397667

9

Davis M. H. (1994). Empathy: A Social Psychological Approach. Boulder: Westview Press.

10

Egan P. J. Mullin M. (2012). Turning Personal Experience into Political Attitudes: The Effect of Local Weather on Americans' Perceptions about Global Warming. J. Polit.74 (3), 796–809. 10.1017/S0022381612000448

11

Fowler J. H. Kam C. D. (2006). Patience as a Political Virtue: Delayed Gratification and Turnout. Polit. Behav.28 (2), 113–128. 10.1007/s11109-006-9004-7

12

Frederick S. Loewenstein G. O’donoghue T. (2002). Time Discounting and Time Preference: A Critical Review. J. Econ. Lit.40 (2), 351–401. 10.1257/00220510232016131110.1257/jel.40.2.351

13

Gjesme T. (1975). Slope of Gradients for Performance as a Function of Achievement Motive, Goal Distance in Time, and Future Time Orientation. J. Psychol.91 (1), 143–160. 10.1080/00223980.1975.9915808

14

Graham H. Bland J. M. Cookson R. Kanaan M. White P. C. L. (2017). Do People Favour Policies that Protect Future Generations? Evidence from a British Survey of Adults. J. Soc. Pol.46 (3), 423–445. 10.1017/S0047279416000945

15

Grönlund K. Herne K. Setälä M. (2017). Empathy in a Citizen Deliberation Experiment. Scand. Polit. Stud.40 (4), 457–480. 10.1111/1467-9477.12103

16

Healy A. Malhotra N. (2009). Myopic Voters and Natural Disaster Policy. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev.103 (3), 387–406. 10.1017/S0003055409990104

17

Hetherington M. J. (1998). The Political Relevance of Political Trust. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev.92 (4), 791–808. 10.2307/2586304

18

Hibbing J. R. Theiss-Morse E. (2002). Stealth Democracy. Americans’ Beliefs about How Government Should Work. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/cbo9780511613722

19

Hooghe M. (2011). Why There Is Basically Only One Form of Political Trust. The Br. J. Polit. Int. Relations13 (2), 269–275. 10.1111/j.1467-856X.2010.00447.x

20

Jacobs A. M. Matthews J. S. (2012). Why Do Citizens Discount the Future? Public Opinion and the Timing of Policy Consequences. Br. J. Polit. Sci.42 (4), 903–935. 10.1017/S0007123412000117

21

Jacobs A. M. Matthews J. S. (2017). Policy Attitudes in Institutional Context: Rules, Uncertainty, and the Mass Politics of Public Investment. Am. J. Polit. Sci.61 (1), 194–207. 10.1111/ajps.12209

22

Jacobs A. (2011). Governing for the Long Term: Democracy and the Politics of Investment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/cbo9780511921766

23

Jacobs A. M. (2016). Policy Making for the Long Term in Advanced Democracies. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci.19, 433–454. 10.1146/annurev-polisci-110813-034103

24

Jylhä M. (2009). What Is Self-Rated Health and Why Does it Predict Mortality? towards a Unified Conceptual Model. Soc. Sci. Med.69 (3), 307–316. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.013

25

Kulha K. Leino M. Setälä M. Jäske M. Himmelroos S. (2021). For the Sake of the Future: Can Democratic Deliberation Help Thinking and Caring about Future Generations?Sustainability13 (10), 5487. 10.3390/su13105487

26

Lennings C. (2000). The Stanford Time Perspective Inventory: An Analysis of Temporal Orientation for Research in Health Psychology. J. Appl. Health Behav.2 (1), 40–45. 10.14195/978-989-26-0775-7_4

27

Lynch J. G. Jr Netemeyer R. G. Spiller S. A. Zammit A. (2010). A Generalizable Scale of Propensity to Plan: The Long and the Short of Planning for Time and for Money. J. Consum Res.37 (1), 108–128. 10.1086/649907

28

MacKenzie M. (2013). Future Publics: Long-Term Thinking And Farsighted Action In Democratic Systems. Ph.D. Thesis. Columbia: University of British Columbia.

29

MacKenzie M. Caluwaerts D. (2021). Paying for the future: deliberation and support for climate action policies. J. Environ. Policy Plann.23 (3), 317–331. 10.1080/1523908X.2021.1883424

30

Mattila M. Rapeli L. (2018). Just Sick of it? Health and Political Trust in Western Europe. Eur. J. Polit. Res.57 (1), 116–134. 10.1111/1475-6765.12218

31

Misztal B. A. (1996). Trust in Modern Societies: The Search for the Bases of Social Order. Cambridge: Polity Press.

32

Mondak J. (2010). Personality and the Foundations of Political Behavior. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/cbo9780511761515

33

Nakagawa Y. Kotani K. Matsumoto M. Saijo T. (2019). Intergenerational Retrospective Viewpoints and Individual Policy Preferences for Future: A Deliberative experiment for forest Management. Futures105, 40–53. 10.1016/j.futures.2018.06.013

34

Nannestad P. Paldam M. (2000). “Into Pandora's Box of Economic Evaluations: a Study of the Danish Macro VP-Function, 1986–1997. Elect. Stud.19 (2–3), 123–140. 10.1016/S0261-3794(99)00043-8

35

Rebenstorf H. (2004). “Political Interest – its Meaning and General Development.” in Democratic Development? East German, Israeli and Palestinian Adolescent, Hilke Rebenstorf, 89–93. Wiesbaden: Springer.

36

Reniers R. L. Corcoran R. Drake R. Shryane N. M. Völlm B. A. (2011). The QCAE: a Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy. J. Personal. Assess.93 (1), 84–95. 10.1080/00223891.2010.528484

37

Sargisson R. J. De Groot J. I. M. Steg L. (2020). The Relationship between Sociodemographics and Environmental Values across Seven European Countries. Front. Psychol.11, 2253. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02253

38

Schober P. Boer C. Schwarte L. (2018). Correlation Coefficients. Anesth. Analgesia126 (5), 1763–1768. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002864

39

Seginer R. (2009). Future Orientation: Developmental and Ecological Perspectives. New York: Springer. 10.1007/b106810

40

Strathman A. Gleicher F. Boninger D. S. Edwards C. S. (1994). The Consideration of Future Consequences: Weighing Immediate and Distant Outcomes of Behavior. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol.66 (4), 742–752. 10.1037/0022-3514.66.4.742

41

Strömbäck J. Shehata A. (2010). Media Malaise or a Virtuous circle? Exploring the Causal Relationships between News media Exposure, Political News Attention and Political Interest. Eur. J. Polit. Res.49, 575–597. 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2009.01913.x

42

Swank J. Mullen P. (2017). Evaluating Evidence for Conceptually Related Constructs Using Bivariate Correlations. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev.50 (4), 270–274. 10.1080/07481756.2017.1339562

43

Thompson D. F. (2010). Representing Future Generations: Political Presentism and Democratic Trusteeship. Crit. Rev. Int. Soc. Polit. Philos.13 (1), 17–37. 10.1080/13698230903326232

44

Toff B. Suhay E. (2018). Partisan Conformity, Social Identity, and the Formation of Policy Preferences. Int. J. Public Opin. Res.31 (2), 349–367. 10.1093/ijpor/edy014

45

Tversky A. Kahneman D. (1991). Loss Aversion in Riskless Choice: A Reference-dependent Model. Q. J. Econ.106 (4), 1039–1061. 10.2307/2937956

46

Tyler T. R. (2006). Why People Obey the Law. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

47

Wade-Benzoni K. A. Plunkett Tost L. Hernandez M. Larrick R. P. (2012). It's Only a Matter of Time: Death, Legacies, and Intergenerational Decisions. Psychol. Sci.23 (7), 704–709. 10.1177/0956797612443967

48

Wade-Benzoni K. A. Sondak H. Galinsky A. D. Adam D. (2010). Leaving a Legacy: Intergenerational Allocations of Benefits and Burdens. Bus Ethics Q.20 (1), 7–34. 10.5840/beq20102013

49

Walter H. (2012). Social Cognitive Neuroscience of Empathy: Concepts, Circuits, and Genes. Emot. Rev.4 (1), 9–17. 10.1177/1754073911421379

50

Weaver R. K. (1986). The Politics of Blame Avoidance. J. Pub. Pol.6 (4), 371–398. 10.1017/S0143814X00004219

51

Wlezien C. (2004). Patterns of Representation: Dynamics of Public Preferences and Policy. J. Polit.66 (1), 1–24. 10.1046/j.1468-2508.2004.00139.x

Summary

Keywords

democratic process preferences, political attitudes, democratic myopia, general time orientation, political trust

Citation

Rapeli L, Bäck M, Jäske M and Koskimaa V (2021) When do You Want It? Determinants of Future-Oriented Political Thinking. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:692913. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.692913

Received

09 April 2021

Accepted

02 June 2021

Published

22 June 2021

Volume

3 - 2021

Edited by

Hilde Coffe, University of Bath, United Kingdom

Reviewed by

Anna Kern, Ghent University, Belgium

Paul Webb, University of Sussex, United Kingdom

Updates

Copyright

© 2021 Rapeli, Bäck, Jäske and Koskimaa.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lauri Rapeli, lauri.rapeli@abo.fi

This article was submitted to Elections and Representation, a section of the journal Frontiers in Political Science

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.