Abstract

This article investigates voters' preferences for party families in Western European countries' general elections in the 2000s. According to the realignment literature, “traditional” class voting patterns have been replaced by new class-party alignments: upper-middle employee classes joined the electoral bases of left parties, whereas radical right actors introduced in the electoral competition of the most deprived strata of the population, labeled “left behind”. This article aims to answer to the research questions: do social class and political values affect voting behavior in Western European general elections? Which direction are these variables associated with the preference of party families? The first section outlines the theoretical framework, accounting for the “societal modernization” processes, which have been affecting Western societies since the late 1960s. Among the “traditional” cleavages, the literature assumes the realignment of class voting patterns, as well as alignments between value orientations and political preferences. Indeed, class-party alignments are mediated by the political supply's mobilization of voters according to their value orientations. Such appeals differ among party families, partly explaining why specific classes constitute their electoral bases or contested stronghold. The theoretical framework hypothesizes political values as clustered in three ideologies (social and economic conservatism-liberalism, and authoritarianism-libertarianism). Those political values, which do not assimilate in ideologies, constitute more proximal factors, i.e., evaluations of specific political issues close to elections (attitudes). Having defined class voting realignment and a theoretical account of value voting, the paper empirically investigates their associations with vote choices in Western Europe. The analyses ground on European Social Survey data, aggregating the responses concerning the 12 Western European countries for which data are available in all waves. The dependent variable clusters the parties, which competed in the general elections occurred in the time span considered, in party families. Fixed effects multinomial logistic regression models are performed to detect which social classes constitute party families' bases or contested stronghold and how more proximal variables based on values account for class voting patterns. The results clearly show whose social classes are more likely to have voted for radical left, center-left, center-right, and radical right party families. Political ideologies account for a portion of these preferences for mainstream political actors, whereas political attitudes partly explain the introduction of radical right parties in the competition for working classes with left families.

Introduction

Voting behavior constitutes an interdisciplinary research topic characterized by a bulk of theoretical and analytical perspectives. Among these perspectives, a currently prominent debate pertains to two different definitions of voters: individualized or affected by their social positions. The former definition underpins dealignment theory, whereas the latter underpins realignment theory. This article fits in such a debate, aiming to give empirical support to the realignment perspective and to answer the research questions: do social class and political values affect voting behavior in Western European general elections? Which direction are these variables associated with the preference of party families? In accordance with the theoretical framework outlined in the first section, the analyses aim to provide further insights into cleavage politics in Western European countries during the 2000s. Such analyses center on political demand by investigating which parties constituting Western European political supply are perceived by voters as responding to their own demands, which, in turn, reflect their socio-structural positions and values. Thus, individual probability models are performed, as these provide estimations of the associations concerned, which enable to examine the patterns of class cleavage and their mediation by value divides.

Despite the fact that an analysis focused on the actual existence and direction of voting patterns “would need to take in account both the demand and supply side of politics,” the analytical perspective pertains to “the structural context of mobilization, that is, party preferences of voters” (Oesch, 2008, p. 334). The supply side is accounted for in the dependent variable, concerning party families. Such an approach makes it possible to group together those political actors who share specific names, historical traditions, party programs, and membership of transnational organizations (see Knutsen, 2004, p. 14). In spite of this, only a specific focus on general elections held in individual countries enables to introduce in the analyses the processes at the political-supply level (Thomassen, 2005), and to identify any within-country differences (Knutsen, 2004).

This article focuses on three sets of voting behavior factors. The first concerns social positions, referring to cleavage theory. Of these factors, the main focus is placed on social class, assessing its voting patterns along the lines of the literature on the realignment of class cleavage. Besides providing individuals with material/immaterial resources, social positions also define their socialization processes. Therefore, social positions affect the transfer of political values, which are structured in political ideologies, which constitute the second set of variables. Herein a three-dimensional political ideological space, defined in the next section, is employed. The last set of variables includes political attitudes. According to the literature (e.g., Dalton, 2018), increasing electoral “volatility” in Western countries may be assessed through the introduction of short-term issues' evaluations, as framed by political actors during electoral campaigns. This new conceptualization of value voting is assumed to enable to identify more accurate voting patterns. Indeed, parties mobilize voters by emphasizing/de-emphasizing more than one issue (see Knutsen, 2017); therefore, distinguishing between value orientations that previous authors grouped together enables to further deepen how parties leverage political values.

Moreover, if a mediation perspective is adopted (see Knutsen and Scarbrough, 1995), it is also argued that social status is an antecedent factor in the establishment of political values. Indeed, since the socialization agents with whom people interact are determined by socio-structural positions, during adulthood, these “peer groups” are mainly defined by the occupational position. However, it should be pointed out that individuals' identities do not only consist of their membership of a given social class, and the prevalence of the said factor over others with regard to electoral behavior depends on the mobilization strategies pursued by the political supply's actors (Oesch and Rennwald, 2018; Rennwald, 2020). Indeed, class divisions are now less relevant as party loyalties than as orientations toward issues activated/de-activated by political actors (Evans and Northmore-Ball, 2018). The mediation approach is delved into in the next two sections, which focus on the theoretical framework and the analytical methods. Then, the third section presents the results.

Theory

The debate centered on the role of social positions has been ongoing in voting behavior research topic since the 1970s. Structuralist approaches, concerning Columbia University and cleavage theory, theorized enduring alignments between social positions and political preferences. However, according to modernization theory, which underpins a rational-based perspective, such alignments have been eroding in affluent Western democracies since the development of new economic and social (e.g., secularization) processes in the second half of the Twentieth century (Thomassen, 2005; Dalton, 2018; Ford and Jennings, 2020). Accordingly, political behaviors were assumed to lose their strong anchoring on social positions and to become increasingly “volatile”. These elements define political dealignment: Parties are less perceived as representatives of social groups (von Schoultz, 2017), and empirical studies focus more on proximal voting determinants, considered more flexible to explain both the political preferences and their variation over time. Despite the literature agrees on considering the “traditional” alignments between social positions and political preferences, theorized by cleavage theory,1 as weakened by “societal modernization” processes, the political actors which shaped these alignments still gain votes. According to the opposite perspective, i.e., political realignment, these actors appeal to different electoral bases than before. Such electoral bases, as well as the ones characterizing new rising political forces, can be defined by either the same social positions, yet following new patterns, or new factors.

Despite “societal modernization” processes determine a weaker attachment to social groups, the erosion in quantitative terms of some groups, and the resolution of the main social conflicts characterizing the modernity in its first phase (Kriesi, 1998, 2010; von Schoultz, 2017; Dalton, 2018; Ford and Jennings, 2020), a realignment perspective hypothesizes that the same processes generate “a temporary phase of partisan decay before new alignments between parties and voters are established” (von Schoultz 2017, p. 31). Therefore, cleavage theory is redefined to encompass the reorganization of political competition: a top-down perspective is considered along with the bottom-up of its first formulation. Accounting for processes in both political supply and demand, the role played by political élites in shaping social divisions (i.e., their agency) is recognized. Besides reacting to “societal modernization” processes, political supply actors provide competing interpretations of political issues, influencing voters' choices and structuring/restructuring the alignments between social positions and political preferences (von Schoultz, 2017; Dalton, 2018; Evans and Northmore-Ball, 2018; Ford and Jennings, 2020). The realignment perspective accounts for both the redefinition of “traditional” cleavages and the “birth” of new lines of conflict, cutting across the old divisions. Indeed, the intertwined top-down and bottom-up processes transform the Western European electoral competition, generating the conditions for new conflicts and mobilization chances (Enyedi, 2008; Ford and Jennings, 2020).

The current literature argues that, of the four cleavages defined by Lipset and Rokkan (1967) in their landmark comparative study of Western Europe, center-periphery (territorial) and class ones continue to shape voters' electoral behavior (see Ford and Jennings, 2020). The focus on the latter cleavage is due to the long-standing and long-lasting debate concerning it (Elff, 2009). Indeed, the change of economic development model (post-industrialism) and the consequential decline of its main institutions (industries and trade unions) affected the labor market, disrupting the former vertical social hierarchy. Accordingly, the literature considers the “traditional” class voting pattern, which theorized associations between working class and left parties and between the upper classes and right-wing political actors (Oesch, 2006; Dalton, 2018; Ford and Jennings, 2020), as weakening since the 1990s. However, the political realignment perspective hypothesizes that such evidence is due to outdated operationalizations of class (von Schoultz, 2017; Evans and Northmore-Ball, 2018). Indeed, the location in the labor market affects a person's amount of available resources, structuring inequalities between social positions and differences between their shared interests (Oesch, 2006). The trends in the labor market2 determined the working class decrease in quantitative terms, the blurring of the duality between manual and non-manual jobs, and the salaried middle-class expansion and heterogenization. New class schema proposals better account for such changes by intertwining the hierarchical dimension with a horizontal one, which discriminates within the hierarchically equivalent classes. The two dimensions identify daily work experiences and routines, which affect value orientations in the social world (Kitschelt and Rehm, 2014; Oesch and Rennwald, 2018). The realignment perspective also considers how the political supply faces the changes in the political demand: mainstream parties are redefined as “catch-all”, whereas new anti-establishment actors attract the most deprived strata of the electorate (so-called “left behind”) by leveraging their political marginalization (Ford and Jennings, 2020). Accordingly, more fine-grained alignments are detected: upper-middle employee classes find representation in center-left parties, whereas business owners and managers prefer mainstream right-wing ones; working classes are shown to be sensitive to anti-establishment and far-right political actors, who were introduced in the political niches constituted by people whose interests were previously mobilized by left-wing forces (Oesch and Rennwald, 2018; Rennwald, 2020). The focus on classes' value orientations and their associations with political supply's strategies shows that class divisions are no more relevant as party loyalties as well as orientations toward issues activated/de-activated by political actors (Evans and Northmore-Ball, 2018).

Social positions do not only provide individuals with material/immaterial resources and constraints, but they also define their daily experiences and routines, affecting their orientations in the social world (see Kitschelt and Rehm, 2014). Indeed, social positions determine people's social interactions, on which socialization grounds (Neundorf and Smets, 2017). Within the political sphere, this process conveys political values, which are organized in value orientations and structured in political ideologies. Indeed, the realignment perspective also theorizes a new “critical juncture”, which focuses on values and plays a mediating role between social positions and political preferences (see Knutsen and Scarbrough, 1995). Value orientations' associations with political preferences are better conceived by the notion of a “divide”, defined by the interplay between issues and vote choices (see von Schoultz, 2017). Socio-cultural, economic, and political values are theorized to structure in ideologies,3 according to both everyday life interactions and political élites (Marchesi, 2019). Despite the fact that “new politics” literature hypothesizes a two-dimensional political ideological space in Western countries, composed by an economic dimension and a social dimension, the social worldview is conceived as made up of two dimensions. These are based on different contents, shown to better account for political supply and demand: social conservatism-liberalism and authoritarianism-libertarianism (Stenner, 2009). Therefore, it is theorized that Western countries witnessed the historical development of three main ideologies. Conservatism-liberalism continuum is constituted by two facets: economic and social. This second facet is separated from authoritarianism-libertarianism; such an ideology is not focused on social stability and preservation of status quo, yet concerns a predisposition to favor obedience and conformity over freedom and difference (ibidem). However, people's evaluations of few specific issues, i.e., attitudes, “do not assimilate easily” into the ideological dimensions, cross-cutting them (Enyedi 2008, p. 294). Ideologies structure these evaluations, concerning short-term factors usually employed to analyze the increasing “volatile” Western electoral context. Yet, certain topics are strongly affected by political actors and mass media framing work during electoral campaigns (e.g., Dalton, 2018). Among these topics, the attitudes toward the European Union and immigration cross-cut the three dimensions, and the performance evaluation of political institution is strongly related to the rise of anti-establishment parties. The next section provides the definition and operationalizations of the political ideologies and attitudes included in the analyses. Accounting for political attitudes has become prominent since anti-establishment actors have mobilized those sections of the electorate whose ideological outlooks are far from main political actors, and which are characterized by strong feelings toward particular topics (Dalton, 2018; Abou-Chadi and Wagner, 2020; Ford and Jennings, 2020). Indeed, such political actors usually leverage specific issues during electoral campaigns (Vasilopoulos and Lachat, 2018). Accordingly, their ideological alignments are expected to be low.

Since social class is assumed to be temporally antecedent to values, and to play a role in the establishment of these by controlling both political ideologies and political attitudes enables to identify the “net” association between this socio-structural independent variable and the dependent variable (the party choice in general elections). This mediation perspective assumes that each factor is partly affected by previous ones and, in turn, partly affects the subsequent ones, and, therefore, provides insights into electoral “volatility” and the re-structuration of cleavages (see Dalton, 2018).

Data and Methods

The dataset employed is the European Social Survey cumulative from Round 1 (2002) to Round 9 (2018).4 The ESS provides cross-national data covering a broad time span (the first round started collecting data in 2002, while the ninth round was completed in 2020). This dataset comprises information about party preferences in a country's most recent general election, respondents' occupations (this is required in order to formulate social class schema), and respondents' opinions on socio-cultural and economic topics. As a result of focus on cleavage voting, the analyses conducted here concern all those Western European countries that participated in all nine rounds, namely: Finland, Sweden, Norway, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Belgium, the Netherlands, France, Germany, Switzerland, Spain, and Portugal. Fixed effects multinomial logistic regression models are developed to investigate the associations between political preferences and independent variables, with the country and the ESS round introduced as covariates. Further covariates are gender, age group, educational attainment (ISCED 3 classification), and residence5 (big city, small city, suburbs/outskirts, village/country). It should be pointed out that the aggregation of countries does not permit the inclusion of the area of residence in the models, since the actual territorial definitions of “center” and “periphery” differ from one country to the next.

Considering only those respondents providing valid responses regarding all variables, the final sample totaled 107,144.6 Results are presented as average marginal effects (AMEs),7 and class polarization is assessed by computing kappa indexes (Hout et al., 1995). Kappa indexes may refer both to the entire set of parties standing for election, and to individual parties or party families. It is interpreted as a measure of the degree to which classes' preferences for political parties vary on average from the corresponding party's average preference.8 The AMEs provide estimations of the absolute differences in the likelihood to have voted for each party family, whereas the kappa index measures the degree to which the likelihood of having voted for a party family is different among social classes. Indeed, the marginal differences associated with voting for a party family may be “small” in absolute value (observing the AMEs) and become “large” in relative terms when the average likelihood to have voted for such a party family is accounted for. Kappa indexes represent total “gross” class voting, the full association, and how this changes when other variables are introduced into the model (Langsæther, 2019). This is in keeping with the aforementioned mediation perspective: the association observed between long-term and dependent variables is given by the sum of an indirect effect, i.e., the association between a third set of variables (mediators) and both the dependent and independent variables, and the direct effect between these two, net of mediators (see VanderWeele, 2015). The dependent variable concerns the questions about the party that people voted for in the most recent general elections. Parties are grouped into six classes: Green, Radical Left, Center-Left, Center-Right, Radical Right, Other parties or coalitions.9 The classification of Western European parties according to their “center” or “radical” features enables a more fine-grained assessment of these parties' electoral appeals, as it will be shown in the following sections.

As regards to the three sets of independent variables, respondents' class position is assessed by applying Oesch (2006) 8-class schema to the data. This schema enables to discern “hierarchically between more or less advantageous employment relationships based on people's marketable skills” and “horizontally between different work logics” (Oesch and Rennwald 2018, p. 791). The interaction of these two dimensions differentiates between the self-employed and employees and discriminates within hierarchically equivalent classes (Oesch, 2006). Accordingly, such an operationalization provides more fine-grained class voting patterns than the working class-bourgeoisie division. The eight classes are shown in Table 1. Office clerks constitute the reference category in the subsequent regression models, since they are assumed to approximate to the median voter (Oesch and Rennwald, 2018). The class voting patterns highlighted by the political realignment literature and discussed in the theoretical section point out the following hypotheses: the upper-middle employee classes tend to perceive that their interests are represented by center-left parties, while business owners and managers tend to vote for mainstream right-wing ones (H1); at the same time, the working classes, and, specifically, manual workers reveal to be sensitive to anti-establishment radical right actors, and, as such, their votes are contested for by such actors and the left-wing parties (H2). Respondents are assigned to classes according to “their current or, if missing, past jobs”, starting from the ISCO 4-digit variable (Oesch and Rennwald, 2018, p. 792). Those who do not have a current job or have not been employed in the past are assigned a class position on the basis of the position of their partners.10 A covariate concerning respondents' employment status is introduced into the models to maintain the focus on individuals rather than on households.11

Table 1

| Independent work logic | Technical work logic | Organizational work logic | Interpersonal service work logic |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Self-employed professionals and large employers | 3. Technical professionals and semi-professionals | 5. Managers and associate managers | 7. Socio-cultural professionals and semi-professionals |

| 2. Small business owners | 4. Production workers | 6. Office clerks | 8. Service workers |

The collapsed 8-class schema based on Oesch (2006).

The second and third sets of independent variables concern political ideologies and attitudes, which are measured by means of scaling procedures. The equivalence across countries of such measures must be accounted for while performing these procedures, especially when cross-national survey data are employed. Three types of equivalence are addressed herein: construct, structural, and measurement unit/scalar.12 The resulting variables, assumed continuous, are recoded between zero and one.13 However, since data do not provide enough items to cover all the theoretical dimensions of the operational definitions of political ideologies and attitudes, some of these constructs must be assessed using proxies. As far as ideologies are concerned, proxies are employed to account for economic conservatism-liberalism and authoritarianism-libertarianism. The former ideology is defined as focused on the involvement of the government in the economy, the regulation of private enterprise, and the welfare state (Crowson, 2009). The measure computed for this is based on one item introduced in all rounds, concerning the role of government in the economy, previously adopted by Oesch and Rennwald (2018): “Government should reduce differences in income levels” (reverse-score). The resulting proxy has a mean value of 0.31 (SD = 0.26). A Principal Components Analysis (PCA) provides a measure for social conservatism-liberalism. The items taken into account are the ones introduced in every ESS round, and considered capable of embracing, to a considerable degree, the conceptual domain of the corresponding operational definition. These items concern religion, which has been one of the main elements of social conservatism since its initial theorizations; intolerance of ambiguity and complexity in the social world, including the sexual sphere (conservatives are less tolerant toward new conceptions of sexuality, i.e., sexual orientations other than heterosexuality); and traditions, which is another key element of conservatism's definitions (see Kirk, 1953). The PCA performed (KMO Test = 0.78) revealed just one component with an eigenvalue of more than 1 (2.60), accounting for 52.02% of variance. Table 2 presents the items and their loadings (Cronbach's Alpha = 0.75). The mean of the final measure is 0.36 (SD = 0.21).

Table 2

| Item | Loadings |

|---|---|

| Gays and lesbians free to live life as they wish (R) | 0.25 |

| How religious are you | 0.52 |

| How often pray apart from at religious services | 0.52 |

| How often attend religious services apart from special occasions | 0.51 |

| Important to follow traditions and customs | 0.36 |

Items and loadings of social conservatism-liberalism measurea.

Choosing |0.25| as the minimum acceptable factor loading, no significant differences are found among the countries concerned. Only the item concerning sexuality reveals a loading of between |0.20| and |0.22| in four of the countries (Sweden, Ireland, Germany, and Portugal). As far as Cronbach's Alpha is concerned, its value ranges from 0.69 (Sweden) to 0.77 (Ireland and Spain).

As outlined in the theoretical section, the ideological social facet is completed by one further dimension, namely, authoritarianism-libertarianism. Psychological literature usually defines this as the combination of three elements: authoritarian submission, conventionalism, and authoritarian aggression. Yet, this operationalization may overlap with other concepts (Vasilopoulos and Lachat, 2018). Furthermore, the ESS datasets do not provide items capable of encompassing all of their facets. A different perspective was proposed by Feldman (2003). Making no references to specific targets and political arrangements, the author views authoritarianism as a trade-off between the opposing values of personal autonomy (concerning diversity, freedom, and support for civil liberties, and outgroups) and social control (centered around conformity, obedience, authority, social norms, limited civil liberties, and intolerance toward outgroups and non-conformists). For the purposes of the analyses set out here, this second conceptualization offers a better idea of the authoritarianism-libertarianism continuum, which is defined not in terms of a personality trait but as a disposition that complements a political ideology, causally prior to political attitudes and vote choice (Vasilopoulos and Lachat, 2018). The resulting proxy measure is defined as authoritarian predispositions (Feldman, 2003), and is based on Schwartz (1992) Portrait Value Questionnaire (see Arikan and Sekercioglu 2019, p. 1103). Accordingly, the proxy measure is computed by subtracting from the average score on conservation values the score concerning openness to change, i.e., opposing conformity, security, and tradition to self-direction and stimulation. Hedonism is not included since it belongs to both the openness-to-change and the self-enhancement dimensions. Table 3 shows the final set of items. The measure obtained has a mean of 0.51 (SD = 0.12).

Table 3

| Value Dimension | Value Orientation | Item |

|---|---|---|

| Conservation | Conformity | Important to do what is told and follow rules |

| Important to behave properly | ||

| Traditiona | Important to be humble and modest, not draw attention | |

| Security | Important to live in secure and safe surroundings | |

| Important that government is strong and ensures safety | ||

| Openness to change | Self-direction | Important to think new ideas and being creative |

| Important to make own decisions and be free | ||

| Stimulation | Important to seek adventures and have an exciting life | |

| Important to try new and different things in life |

Value dimensions, value orientations, and the items in Schwartz (1992) model of human values provided by the ESS dataset and used to compute the measure of authoritarian predispositions (see Arikan and Sekercioglu, 2019).

Tradition value orientation is constituted by two items. Yet one of them focuses on social conservatism and is introduced in its PCA. Accordingly, while computing the measure of authoritarian predispositions, only one of them is considered.

As regards to political ideologies, the following hypotheses are considered: as previous analyses have shown (e.g., Oesch and Rennwald, 2018; Abou-Chadi and Wagner, 2020), social and economic conservatism and authoritarianism are positively associated with mainstream right-wing parties and negatively associated with left-wing parties (H3); anti-establishment radical right actors are weakly associated with political ideologies due to the long-standing history of the latter and the recent rise of the former (H4); as social class schemas are based principally on economic issues, the economic continuum accounts more for class polarization than the other dimensions do (H5). However, certain topics “do not assimilate easily” into the ideological dimensions but tend to cut across them (Enyedi 2008, p. 294) and are strongly affected by the framing operations of political supply and the mass media during electoral campaigns (Dalton, 2018; Vasilopoulos and Lachat, 2018). It is argued that anti-establishment actors gain more leverage from such issues than from issues structured in political ideologies (H6). Indeed, these parties mobilize specific feelings, and, therefore, they may be weakly aligned with their voters in ideological terms (see Enyedi et al., 2020). The measures computed in order to assess the evaluations of these issues constitute the final set of independent variables. Indeed, the mediation perspective does not overlook short-term factors, concerning evaluations assumed to be structured in attitudes. Every round of the ESS includes items focusing on three political attitudes: opposition to immigration, mistrust of the European Union, and mistrust of the political system. As in Knutsen (2017), a PCA is performed in order to measure the first attitude (KMO Test = 0.73) by adopting three items concerning the opinions of respondents with regard to the effect of immigration on the economy, the national culture, and inter-group relations. These items and their loadings are shown in Table 4. The only component with an eigenvalue of more than one (2.33) accounts for 77.72% of the variance (Cronbach's Alpha = 0.86). The final measure has a mean of 0.44 (SD = 0.20).

Table 4

| Item | Loadings |

|---|---|

| Immigration bad or good for country's economy (R) | 0.57 |

| Country's cultural life undermined or enriched by immigrants (R) | 0.58 |

| Immigrants make country worse or better place to live (R) | 0.59 |

Items and loadings of the measure of the attitude toward immigrationa.

No significant differences were found when comparing factor loadings among countries (these range from |0.56| to |0.60|). As far as Cronbach's Alpha is concerned, its value ranges from 0.77 (the Netherlands) to 0.90 (the United Kingdom).

The stance taken with regard to the European Union constitutes another attitude considered by Knutsen (ibidem). Herein, this stance is assessed by means of a single item measuring trust in the EU's supranational parliament. Such a measures is recoded so that lower trust equates to higher values, and the means = 0.54 (SD = 0.22). The final attitude considered here concerns the degree of mistrust14 of the political system, which is argued to be associated with the rise of anti-establishment political actors. The ESS comprises three items reflecting the respondents' trust (or a lack thereof) in parliament, politicians, and political parties. Unfortunately, only the first two have been included in the questionnaire as of the first round of the ESS. This means that a scaling procedure is impossible to perform. Accordingly, a proxy measure has been computed as the average of the two variables.15 Its mean = 0.53 (SD = 0.21).

Each independent variable is introduced individually in the model in order to establish how its introduction changes the coefficients of interest. Although the following section shows the three main models, the entire set of those performed is provided in the Supplementary Material. Indeed, the role of individual factors in affecting the classes' AMEs is better understood by looking at these models. The mediation perspective requires an analysis of the associations between the mediators and both dependent and independent variables in order to understand how and why the other associations differ once new variables are introduced into the model. Such analyses pertain to both kappa indexes and linear regression models, with ideologies or attitudes as the dependent variables and social class as the independent one. While an entire section is devoted to kappa indexes, the second set of analyses is provided in the Supplementary Material and is referred to when commenting on the results.

Results

Class Voting Patterns and Value Divides

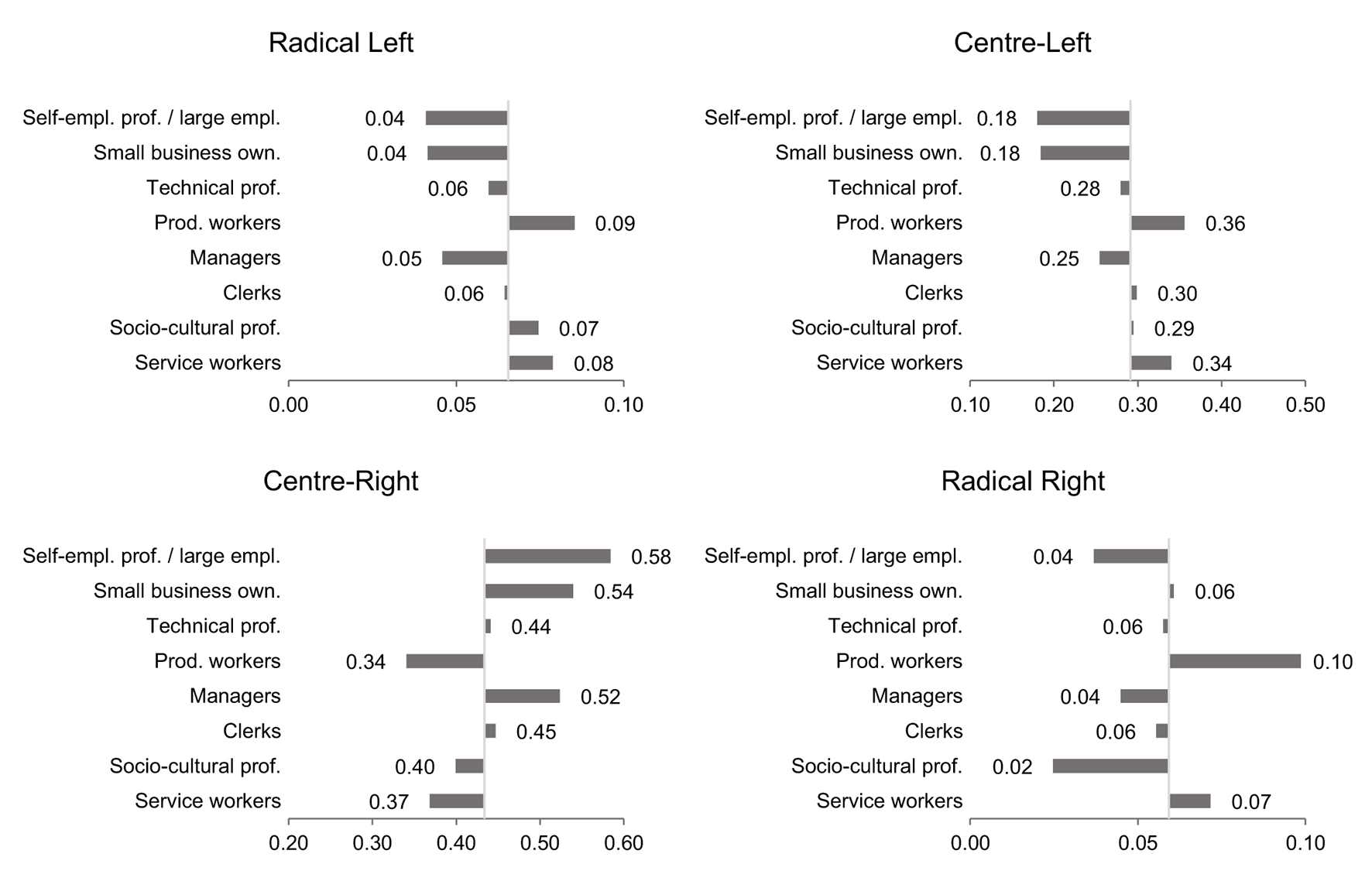

Before presenting the multinomial logistic regression models performed, class voting patterns are introduced according to the bivariate association between social class and the dependent variable. Figure 1 shows the class differences in electoral support for radical left, center-left, center-right, and radical right party families. It shows that the electoral base of left-wing parties is mainly constituted by sociocultural professionals and the working classes, while the latter classes are also mobilized by radical right actors. The radical right parties also gained a non-negligible share of their votes from small business owners. The center-right parties' votes mainly come from those most involved in the market, namely, the self-employed classes and managers. This party family is also popular among technical professionals and clerks, whose votes they contend for in competition with the center-left parties. The bivariate model corroborates the hypotheses (H1 and H2), as well as the empirical literature's findings (e.g., Oesch and Rennwald, 2018; Rennwald, 2020). The results call back the definition of sociocultural professionals as “leftist”, which is associated with their interpersonal work logic (see Oesch, 2006) and their preference for egalitarian economic policies. According to Kriesi (1998), this economic orientation distinguishes between this upper-middle class and that of managers.

Figure 1

Electoral support for radical left, center-left, center-right, and radical right party families (relative values). The y-axis intersects the x-axis at the point of marginal electoral support: radical left = 6.55%, center-left = 29.14%, center-right = 43.35%, radical right = 5.93% (although green and other party or coalition families are not shown, their marginal elector support is, respectively, 6.93% and 8.09%). N = 107,144. Weighted data.

These patterns are further analyzed by performing multivariate models, whereby these associations are controlled for the covariates and the mediators defined in the previous section. The models reflect the likelihood of individuals having voted for each of the party families considered during the Western European general elections held between the late 1990s and 2019 (this is the time span covered by the ESS cumulative dataset). A social class AME concerns the difference in the average likelihood of having voted for a specific party family between the social class observed and the reference category (clerks). Such differences enable to identify the main electoral basis of each party family, i.e., those social classes most likely to have voted for the parties constituting such a family. The AME of a continuous measure assesses the differences in the average likelihood of having voted for a specific party family per one unit increase in the measure. These results enable to observe value voting patterns by detecting the sets of values which given party families tend to appeal to. Although each of the six measures of political ideologies and attitudes is introduced individually in order to establish how its introduction changes the coefficients in question, Table 5 illustrates the three main models: M1 includes social class and covariates only, M2 introduces the three measures of political ideologies, while M3 introduces the three measures of political attitudes.

Table 5

| M1+class | M2+ideol | M3+att | M1+class | M2+ideol | M3+att | M1+class | M2+ideol | M3+att | M1+class | M2+ideol | M3+att | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radical left | Center-left | Center-right | Radical right | |||||||||

| Social class (ref. clerks) | ||||||||||||

| Self-empl. prof./large employers | −0.02*** | −0.01*** | −0.01*** | −0.10*** | −0.08*** | −0.08*** | 0.11*** | 0.09*** | 0.10*** | −0.01** | −0.01*** | −0.01** |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Small business own. | −0.02*** | −0.01*** | −0.01*** | −0.10*** | −0.09*** | −0.08*** | 0.08*** | 0.06*** | 0.06*** | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.00 |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Technical prof. | −0.00 | −0.00 | −0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.00 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01** | −0.01** | −0.01** |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Prod. workers | 0.02*** | 0.01*** | 0.01*** | 0.05*** | 0.05*** | 0.06*** | −0.09*** | −0.08*** | −0.08*** | 0.03*** | 0.03*** | 0.01*** |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Managers | −0.01*** | −0.01*** | −0.01*** | −0.03*** | −0.01** | −0.02*** | 0.07*** | 0.05*** | 0.05*** | −0.01*** | −0.02*** | −0.01*** |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Socio–cultural prof. | 0.02*** | 0.02*** | 0.02*** | 0.02*** | 0.03*** | 0.02*** | −0.05*** | −0.05*** | −0.04*** | −0.03*** | −0.03*** | −0.02*** |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Service workers | 0.01*** | 0.01*** | 0.01*** | 0.03*** | 0.03*** | 0.04*** | −0.06*** | −0.06*** | −0.06*** | 0.01*** | 0.01*** | 0.01** |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Economic conservatism | −0.11*** | −0.10*** | −0.21*** | −0.21*** | 0.36*** | 0.35*** | 0.03*** | 0.02*** | ||||

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |||||

| Social conservatism | −0.15*** | −0.13*** | −0.20*** | −0.21*** | 0.35*** | 0.33*** | −0.01*** | −0.01** | ||||

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |||||

| Authoritarian pred. | −0.04*** | −0.03*** | 0.06*** | 0.08*** | 0.13*** | 0.07*** | 0.00 | −0.02*** | ||||

| (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | |||||

| Interaction terms (ideol) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Anti-immigration | −0.05*** | −0.16*** | 0.17*** | 0.18*** | ||||||||

| (0.00) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.00) | |||||||||

| EU distrust | 0.05*** | −0.05*** | −0.01 | 0.03*** | ||||||||

| (0.00) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.00) | |||||||||

| Political system distrust | 0.06*** | −0.05*** | −0.16*** | 0.07*** | ||||||||

| (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.00) | |||||||||

| Interaction terms (att) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||||

| Country and ESS round dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| McFadden R2 | 0.112 | 0.152 | 0.175 | 0.112 | 0.152 | 0.175 | 0.112 | 0.152 | 0.175 | 0.112 | 0.152 | 0.175 |

| N | 107,144 | 107,144 | 107,144 | 107,144 | 107,144 | 107,144 | 107,144 | 107,144 | 107,144 | 107,144 | 107,144 | 107,144 |

Voting for the radical left, center-left, center-right, and radical right.

Marginal effects (with standard errors) based on multinomial logistic regressions. Only social class and ideological and attitudinal variables are shown.

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01. All models include covariates. For the full models, see the Supplementary Material.

M1 provides a second assessment of the association between social class and voting. The self-employed classes, both professionals/large employers and small business owners, are those most likely to have voted for center-right parties in the Western European countries' general elections. Indeed, an individual belonging to one of aforesaid two classes is, respectively, an 11 and 8% more likelihood to have voted for a center-right actor than clerks (the reference category) are. As expected, managers reveal the same pattern (7% more likely than clerks). Conversely, these three classes are the least likely to have voted for center-left parties (respectively, −10, −10, and −3% than clerks). Center-left parties gathered the majority of their votes from sociocultural professionals, production workers, and service workers (respectively, +2, +5, and +3% more likely than clerks), and were less likely to have voted for mainstream right-wing parties (respectively, −5, −9, and −6% than clerks). The same associations observed between social classes and votes for the center-left party family can also be seen in the case of radical left parties. Considering the radical right parties, production and service workers are the classes most likely to have voted for such actors (respectively, +3 and +1% than clerks), whereas sociocultural professionals, defined as “leftist” by the literature, constitute the class least likely to have vote for them (−3% than clerks). Such patterns are in keeping with the relative hypotheses (H1 and H2), and offer empirical proof in favor of the three assumptions widely present in class voting realignment literature. These assumptions are as follows: the historical competition between the bourgeoisie and the working classes, who constitute the main electoral bases of, respectively, mainstream right-wing and left-wing parties; the difference between the self-employed, who are more likely to be part of the center-right constituency than of the center-left one, and employed workers (except for managers); the electoral competition for the votes of the less privileged classes (the working classes), who are divided between their historical allegiance to the mainstream left-wing political forces and the attractiveness of the radical right. Moreover, given the similarity between the voting patterns of technicians and clerks, despite the former being slightly less likely to vote for radical right-wing parties (−1%), their definition as median voters by Oesch and Rennwald (2018) is also corroborated here.

The three measures of political ideologies are introduced together in M2: R2 increases (0.152), previous patterns are confirmed, and this set of variables partly explains some of the associations between social class and political preferences. The measure of economic conservatism is negatively correlated with having voted for radical and center-left parties (respectively, −11 and −21%) and positively correlated with having voted for radical and center-right ones (respectively, +3 and +36%). Therefore, the likelihood of having voted for the former or the latter decreases or increases, respectively, as this measure increases.16 The measure of social conservatism is negatively correlated with having voted for radical and center-left parties (respectively, −15 and −20%) and positively correlated with having voted for center-right ones (+35%). This variable is also negatively correlated with a slight extent to having voted for radical right political forces (−1%). It should be pointed out that this measure comprises items concerning religion and tradition, whereas, as pointed out in the theoretical section, these actors are observed to mobilize people's on anti-immigrant and Eurosceptic attitudes together with their general political discontent. The measure of authoritarian predispositions is positively associated with having voted for center-right parties (+13%) and is negatively associated with having voted for radical left-wing parties (−4%). While these results concerning the associations between the measures of political ideologies and vote choices confirm the relative hypothesis (H3), the measure of authoritarian predispositions shows a weakly-positive association with having voted for center-left (+6%, although this AME is not statistically significant). As far as this result is concerned, it must be pointed out that the two ideological dimensions of sociocultural values share some information (see Supplementary Table S3). Controlling for the three measures confirms the patterns detected in M1, but it also accounts in part for the differences in the likelihood of having voted for party families between the reference category (clerks) and the self-employed classes, managers, and the working classes. With respect to M1, such differences reduce in absolute value as regards to voting for center-right and left-wing actors: the decision of an individual from one of these classes to vote, or not to vote, for a center-right or a left-wing party is impacted, to some extent, by the mediating role played by political ideologies. Observing kappa indexes in the next section enables to understand which measure accounts for the largest portion of the differences in the likelihood of having voted for each party family among classes. Conversely, and confirming the results of the model which includes only economic conservatism (see Supplementary Table S5), had it not been for the positive association between the measure of economic conservatism and voting for radical right actors, managers would be less likely to have voted for this party family (from −1% than clerks in M1 to −2% than clerks in M2). Since the managers score high on the measure of economic conservatism (see Supplementary Table S2), the managers' likelihood of having voted for radical right parties, although limited, is partly affected by these parties' economic programs.17 Sociocultural professionals score high on the measure of social conservatism (see Supplementary Table S2). Therefore, had it not been for the center-left's stances on social conservatism, this class would be more likely to have voted for the parties of that family (from +2% than clerks in M1 to +3% than clerks in M2), as it has been observed by controlling for social conservatism only (see Supplementary Table S5).

The final set of variables introduced focuses on voters' political attitudes. According to the literature ascribing prominence to short-term factors (e.g., Dalton, 2018), the assessment of specific issues should further the understanding of voting patterns, particularly as regards to voting for radical right parties. In discussing the AMEs of the full model (M3), it must be pointed out that political ideologies and political attitudes share some of their information. Indeed, sociocultural values are structured in two ideologies and three attitudes.18 As regards to the associations between the five measures, those pertaining to political ideologies and to having voted for one of the four party families differ from what is observed in M2. Generally, such associations are weaker in absolute value, with the exception of those between authoritarian predispositions and voting for center-left or radical right parties. In both cases, controlling for political attitudes, the authoritarianism divide is greater and the associations between attitudes and voting for the two party families have the opposite sign of those concerning authoritarian predispositions.19 Examining political attitudinal value divides, anti-immigrant stances are negatively correlated with having voted for radical left (−5%) or center-left (−16%) parties, and positively associated with having voted for center-right (+17%) or radical right (+18%) parties. Distrust of the EU is negatively correlated with having voted for center-left and center-right parties. The same pattern is detected with regard to distrust of the political system: the association is positive between this attitude and having voted for more radical forces, and negative between the same attitude and having voted for less radical parties (center-right parties in particular, whose AME is −16%). Therefore, such results corroborate the hypothesis concerning anti-establishment actors' stronger associations with political attitudes than with political ideologies (H6). As regards to social classes, the working classes score highest on the measures of the three attitudes (see Supplementary Table S2). Indeed, members of the working classes are assumed to be dissatisfied with mainstream parties (Rennwald, 2020) and opposed to processes, such as trans-nationalization, denationalization, globalization, and supranational integration (Hooghe et al., 2002; Kriesi et al., 2006; Kriesi, 2010; von Schoultz, 2017; Abou-Chadi and Wagner, 2020; Ford and Jennings, 2020). Accordingly, part of the significant likelihood of production workers' voting for radical right parties can be accounted for by their positions on such issues (from +3% than clerks in M2 to +1% than clerks in M3). Conversely, had it not been for the negative associations between the three measures and the preference for center-left parties, production and service workers would more likely have voted for them (respectively, from +5% than clerks in M2 to +6% than clerks in M3, and from +3% than clerks in M2 to +4% than clerks in M3).20 Since self-employed professionals and large employers score low on the three measures (see Supplementary Table S2), controlling for attitudes increases the corresponding (already high) likelihood of their having voted for center-right parties: had it not been for the stances of these parties on immigration issue, this class would be more likely to have voted for center-right. Conversely, since small business owners score high on all three measures (see Supplementary Table S2), controlling for attitudes increases the corresponding likelihood of their having voted for center-left parties: political attitudes account for the difference between this class and clerks (the reference category) in terms of the likelihood to have voted for such parties. To conclude, sociocultural professionals are more likely to have voted for mainstream right-wing, and less likely to have voted for mainstream left-wing parties in M3 than in M2. Indeed, since this class scores the lowest on the three attitudinal measures (see Supplementary Table S2), the correlation between having voted for center-left and these three dimensions partly accounts for the likelihood differences pertaining to this class. At the same time, had it not been for the association between having voted for center-right and anti-immigrant attitude, this class would be more likely to have voted for center-right parties.

Having discussed the class-based patterns of voting for specific party families in Western Europe and the mediation of such patterns by value voting divides, the focus now shifts to class voting strength. The AMEs only reveal the differences between social classes in terms of their likelihood of having voted for a specific party family. These differences cannot be used to assess which party family is more inter-classist and which is characterized by the most polarized voting. Furthermore, the assessment of the mediating role played by value voting divides identifies which dimension accounts for the greatest share of the differences between classes in terms of their electoral preferences.

Class Polarization

Social class coefficients enable to investigate each party family's electoral base. Yet, class voting analysis also focuses on the degree to which voting for parties is polarized between classes; this polarization ranges from a total lack of any association (complete inter-classism) to the maximum correlation (when a class is completely prone to vote for a specific individual party or party family). Considering each class' probability distribution of voting for each party family, if at least two classes differ in their distribution with regard to the same party family, then an association between social class and political preferences can be said to exist. As previously mentioned, this association is assessed using the kappa index, proposed by Hout et al. (1995). Since multinomial logistic regression models provide beta values as log odds ratios, a measure of class voting can be computed as the standard deviation of these coefficients, representing the relative differences among classes.21 Such an index can measure class polarization regarding each party family and, also, the entire set of families. When computed for a single party family, the kappa index consists of the standard deviation of the class coefficients (based on the class schema adopted, there are eight such coefficients), with those concerning the reference category kept equal to zero:

j is the party family (the voting outcome) the coefficient refers to (j = 1, … J, here J = 6), while i is the social class (i = 1, … C, here C = 8). βij is the coefficient corresponding to the class i and the party family j, whereas β.j is the mean coefficient for the party family j. Accordingly, the total kappa index for the entire model, i.e., the whole set of voting outcomes, is computed as follows:

Table 6 shows kappa indexes computed for each party family in every model performed, with the variables introduced individually and together from the bivariate to the full one. Therefore, the “gross” association between social class and voting is compared to the “net” ones, resulting from the other models, and the degree to which mediators account for the bivariate class differences regarding party preference is investigated (Langsæther, 2019). The results show that radical right parties are characterized by the greatest polarization in the time span and array of countries considered in the analyses (0.50 in the bivariate model).22 As per the relative hypothesis (H6), the value of the kappa index corresponding to such a party family diminishes to the greatest extent in the full model, i.e., when introducing political attitudes too; the complete set of variables accounts for about 46.55% of the class polarization pertaining to this party family (from 0.50 to 0.27). On the other hand, both center-left, center-right, and radical left forces display their lowest kappa index values (respectively, 0.33, 0.20, and 0.30) when economic conservatism only is introduced. The center-right party family is associated with the strongest inter-classism, as this is characterized by the lowest kappa index value (0.29 in the bivariate model).23

Table 6

| Model | Radical left | Center-left | Center-right | Radical right |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.29 | 0.50 |

| Socio-demographic | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.22 | 0.36 |

| Economic cons. | 0.30 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 0.36 |

| Social cons. | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.22 | 0.35 |

| Eco. * Soc. cons. | 0.31 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 0.35 |

| Authoritarian pred. | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.23 | 0.36 |

| Political ideologies | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 0.35 |

| Political attitudes | 0.34 | 0.35 | 0.22 | 0.28 |

| Full model | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 0.27 |

The class-voting polarization measure (kappa index) for party families.

The first row pertains to the bivariate model.

To conclude, Table 7 shows the kappa indexes computed for the whole set of party families, together with the relative differences once further variables are introduced into the model. Of the various political ideologies, economic conservatism-liberalism is the one that accounts for the largest share of class polarization (25.77%). However, the entire set of political ideologies accounts for an even larger portion (26.31%). Political attitudes play the main role in mediating the association between social class and political preferences (28.95%), since they account for the largest share of radical right parties' class polarization. The full model accounts for the 32.07% of “gross” class polarization (from 0.36 to 0.25).24 It should be pointed out that economic conservatism underpins the very class schema (Rennwald, 2020), and this confirms the relative hypothesis (H5). Indeed, the class schema is based on economic and labor market processes (Oesch, 2006). However, anti-establishment, the radical right party family does not conform to this pattern, since the electoral appeal of such parties in Western European countries is based more on short-term issue evaluations than on political ideologies.

Table 7

| Model | Kappa index | Δ |

|---|---|---|

| Class | 0.36 | |

| Socio-demographic | 0.28 | −23.7% |

| Economic cons. | 0.27 | −25.9% |

| Social cons. | 0.28 | −23.2% |

| Eco. * Soc. cons. | 0.27 | −25.8% |

| Authoritarian pred. | 0.28 | −22.4% |

| Political ideologies | 0.27 | −26.3% |

| Political attitudes | 0.26 | −29.0% |

| Full model | 0.25 | −32.1% |

The class-voting polarization measure (kappa index) for the whole models and the relative differences compared with the bivariate model (first row).

Conclusions

This article fits the debate between political dealignment and realignment, and adopted the latter perspective to assess the general class and value voting patterns in Western European countries in the 2000s. Employing a class schema that combines a hierarchical dimension with a horizontal one enabled to detect more fine-grained class voting patterns, in keeping with previous results. Furthermore, the conceptualization of value voting divides as based on values, which cluster in three ideologies and further attitudes, allowed to provide further insight into voting for left-wing or right-wing parties as well as center and radical political supply's actors.

The analyses presented identified the electoral bases of Western European party families by exploring which social classes they appeal to. The models performed detect which classes are most likely to have voted, on average, for each party family. In doing so, it should be said that the so-called “catch-all” parties gather a non-negligible amount of votes from all social classes, for whose votes they compete with the other actors constituting the political supply (Rennwald, 2020). Despite this, they do tend to mobilize specific social groups, which, in turn, provide the majority of their electoral support. Accordingly, such an analytical focus enables to distinguish three patterns pertaining to social class:

“some classes are one party pole's preserve, other classes are the contested stronghold of two party poles, and, over still other classes, there is an open competition between three party poles.” (Oesch and Rennwald 2018, p. 799)

The self-employed classes and managers result as being the preserve of the center-right, whereas sociocultural professionals constitute the contested stronghold between the two left-wing families.25 The votes of the working classes, on the other hand, are openly contested by the radical left, the center-left, and the radical right.26 Sociocultural professionals and managers are those least likely to have voted for radical right parties. These clear-cut patterns corroborate the first two hypotheses (H1 and H2).

Party families leverage political values too. Mainstream actors strongly mobilize voters along the conservatism-liberalism continuum, whereas radical right actors seem to “fill” the gaps in electoral representativeness by leveraging topics framed and debated during electoral campaigns. Indeed, most of them conform to expectations (H3): the likelihood of having voted for left-wing parties is correlated with higher levels of social and economic liberalism, whereas the opposite can be said in the case of mainstream right-wing actors. Although the same patterns were hypothesized for authoritarianism-libertarianism dimension, center-left actors show a weak but positive association with the measure of authoritarian predispositions. The radical right party family, which includes anti-establishment actors, was more weakly correlated with political ideological measures than were the mainstream parties, revealing their stronger associations with political attitudes (H4). The rise of a wide array of anti-establishment parties is a recent phenomenon, and the literature connects the emergence of this phenomenon with the development of dealignment and realignment processes (see the theoretical section). Furthermore, these parties are “the main beneficiaries” of the Great Recession, which interested the Western World in the 2000s, since their vote shares increased during and after the economic crisis (Hernández and Kriesi, 2016, p. 221).

Kappa indexes enable to establish which sets of mediators best account for the class polarization of voting behavior in the sample. While AMEs reveal the party families' electoral bases, the kappa indexes help to understand the relative weights of the class differences regarding electoral preferences. The economic bases of the class schemas, which are grounded in individuals' occupations (Rennwald, 2020), suggest that economic conservatism-liberalism is the political-ideological continuum that accounts for the largest part of class polarization (H5). However, political attitudes constitute the set of variables associated with the largest reduction in the value of the kappa index, depending on their role in accounting for the class polarization of the radical right parties. This finding backs up the hypothesis concerning the prominence of those issues debated and framed near to the date of an election in terms of the decision to vote for a party of the radical right (H6). Furthermore, the same results tally with those presented by Langsæther (2019), according to whom the political attitude resulting in the largest reduction in the kappa index concerns the issue of immigration. Indeed, there is wide evidence in the literature for the existence of a positive association between the preference for radical right or center-right parties and anti-immigration attitude, and, also, for that between voting for social-democratic parties and the holding of pro-EU views (Hooghe et al., 2002; Kriesi et al., 2006; Oesch and Rennwald, 2018; Abou-Chadi and Wagner, 2020; Ford and Jennings, 2020; Rennwald, 2020). Distrust of institutional actors resulted as being positively associated with both radical left and radical right party families. These associations are in line with the literature, which argues that such feelings, which characterize so-called “left-behind”, are leveraged by radical and anti-establishment actors (Gidron and Hall, 2017; Ford and Jennings, 2020). According to both voting patterns and kappa indexes, the radical right parties' electoral success seems strongly tied to the fragmentation of the working classes' voting behavior. Indeed, these classes appear susceptible to the appeal of those actors who leverage voters on specific topics; this primarily consists in said parties' expressed views on sociocultural issues (e.g., distrust of institutions and opposition to immigration).

The associations between social classes and voting for the party families constituting the Western European political supply have been “depurated” by adopting a mediation perspective. Indeed, this article has aimed to identify class voting patterns in Western European countries and account for such in terms of value-voting divides. The kappa indexes add to the results by providing a measure of class polarization, i.e., an assessment of class voting strength for each party family and for the entire set of party families. However, the results are affected by a 2-fold heterogeneity, concerning national contexts on the one hand, and the dependent variable itself on the other. Considering a wide array of countries means bringing together different historical and institutional elements in the same analysis. This enables to identify any common patterns by controlling for these elements. Simultaneously, the focus on party families, although mandatory when studying several countries together, differs from the focus on specific political actors. Within the same family, while parties share common features, they also may differ according to their political traditions, rivalries, and strategies. Furthermore, as far as the ESS cumulative dataset is concerned, not every country's party system includes at least one actor for every party family considered. Indeed, Western European countries have undergone processes that have seen their party systems develop differently. The models are based on comparative analyses and enable to investigate the validity of the same theoretical framework both among countries and over time (Thomassen, 2005). The common patterns detected need to be examined with a specific focus on countries' elections.

Although with these limitations, the findings presented here show that Western European political parties do mobilize voters according to their positions in the class structure. Furthermore, accounting for voters' value orientations enables to identify how political values affect voting behavior and explains a portion of the differences observed among classes. These conclusions answer to the two research questions. The main contribution offered to the realignment literature is the assessment of the general patterns according to which social class and political values impact on voting behavior. Furthermore, although the mobilization of social classes by political parties is partly explained by these classes' value orientations (and the combinations thereof), there is, still, a portion of class voting, which is not accounted for by these. As far as this is concerned, it must be pointed out that class divisions increased their relevance as orientations toward the evaluation of specific issues, but these still affect voting behavior as the result of conflicts between social groups, according to the “traditional” definition of class cleavage.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

AM is responsible for research design and conceptualization for data cleaning and analysis, and for manuscript writeup.

Acknowledgments

The author wants to thank the Department of Political and Social Sciences at the University of Bologna, in particular Nicola De Luigi, Daniela Giannetti and Alessandro Bozzetti as well as the Editors and the Reviewers, for the useful insights.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2022.871129/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1.^See Knutsen and Scarbrough (1995) or Ford and Jennings (2020) for a definition of the concept of political cleavage.

2.^These main trends concern the growth of the service sector, women's participation and education levels.

3.^Ideologies are defined as social and historical products reproduced and modified by both individuals and political élites, affecting value orientations in turn.

4.^European Social Survey Cumulative File, ESS 1-9 (2020). Data file edition 1.1. NSD - Norwegian Centre for Research Data, Norway—Data Archive and distributor of ESS data for European Social Survey European Research Infrastructure (ESS ERIC).

5.^This variable is based on respondents' own description of their domicile, and it allows to control for the dimension of housing context, considered by the Columbia University studies.

6.^ESS weights are recalibrated with regard to the loss of cases according to country, round, gender, and age groups. The final weights replicate the distribution of the cross-classification of these variables.

7.^Since the coefficients estimated by logistic models are not directly interpretable, marginal effects are computed. AMEs are the average of the predicted changes (the differences) in the fitted values of the dependent variable (marginal effects) for each unit change in each regressor of a given independent variable for each observation in the sample, while controlling for the other independent variables in the model.

8.^The kappa index measures political polarization. This concerns the voting rate by social class, i.e., whether a party or party family obtains votes to the same extent among the different social classes.

9.^Supplementary Table S1 shows the current parties' actual location. The categorization adopted is based on Knutsen, 2004, Knutsen (2017), Oesch and Rennwald (2018), and the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (Bakker et al., 2020). Other parties or coalitions also include centrist political actors. Indeed, according to the categorizations considered, centrist forces only appear in three countries (Finland, Sweden, and Norway). The results presented in the following sections only concern the radical left, the center-left, the center-right, and the radical right party families. The choice to not consider green parties in the analyses is motivated by the fact that the ESS does not include items focused on environmentalism in all nine rounds. This attitude constitutes a prominent factor in understanding the preference for green actors.

10.^The construction of the class schema follows the author's scripts available at: http://people.unil.ch/danieloesch/scripts/.

11.^The categories into which this variable is divided are: employed, unemployed, student, retired, household, other.

12.^As far as construct and structural equivalences, the ESS were faced with biases regarding the construction and translation of the items before collecting data, and the same ideologies and attitudes (defined and operationalized in the same way) are believed to have developed in Western European countries. The resulting set of items must be tested across groups; with the aim of assessing the invariance of each index and the correspondence of its factorial structure among countries, the analyses are performed for the sample as a whole and then tested separately for each country (Byrne et al., 1989; van de Vijver, 2001; Georgas et al., 2004).

13.^Zero and one correspond to the two poles of the ideology measured.

14.^Mistrust is preferred to disaffection since the latter concept is usually employed in political participation studies. Distrust of both national and supranational political institutions seems to be strongly correlated with people's perceived or subjective social status (Gidron and Hall, 2017). However, the ESS data do not provide information about this topic.

15.^A PCA is performed (KMO Test = 0.71) using all three items and focusing on rounds 2–9. The resulting index is standardized between zero and one and has a mean of 0.56 (SD = 0.21). The correlation between this and the proxy measures is 0.98.

16.^It should be noted that the same variable concerning economic values has been adopted by Oesch and Rennwald (2018), whose associations closely resemble the ones set out in Table 5. Furthermore, by aggregating elections among countries and over time, the likelihood of having voted for radical right actors reveals a correlation that is close to the corresponding correlation in the case of center-right party family voting. According to previous analyses (e.g., Knutsen, 2017), Western Europe's radical right parties are generally positioned in the middle of this continuum.

17.^A mediation effect may determine either a higher or a lower “gross” association, according to the directions of the correlations between the corresponding mediator and the dependent and independent variables. In this specific case, since the association between the voting behavior and the specific class is negative, the association between the voting behavior and the measure is positive, and the specific class scores high on this measure (see Supplementary Table S2), controlling for this latter provides a stronger difference between the specific class and the reference category (clerks) for what concerns the voting behavior (the AME increases in absolute value). Indeed, if it had not been for the role played by the measure (mediator), the specific class would be less likely to show such a voting behavior.

18.^Supplementary Table S3 shows the Pearson correlation coefficients between the five variables.

19.^As regards to the radical right party family, had it not been for the positive relationships between authoritarianism and the three attitudes (mainly the anti-immigrant one), the most authoritarian voters would be 2% less likely to vote for these parties than the most libertarian ones would have. For the same reason, and focusing on the center-left party family, the most authoritarian voters would be 8% more likely to vote such a party family than would have the most libertarian ones.

20.^Accordingly, introducing the three attitudes helps explain the appeal of radical right parties for the lower classes at the expense of center-left forces.

21.^The kappa index is equal to zero when there is no association, and positive values are assumed otherwise. However, its maximum value differs in a non-constant way for different numbers of those parties or party families considered, thus preventing comparisons being made among analyses which do not operationalize the dependent variable in the same way. By adopting log odds ratios, a final index can be obtained, which is not sensitive to the marginal distribution of vote choices, i.e., it does not account for the different numbers of respondents in each class (Hout et al., 1995).

22.^Despite the fact that the marginal differences associated with the radical right party family in the models are “small” in absolute terms (observing the AMEs), they become “large” in relative terms, when they are observed in relation to class polarization. The differences in the likelihood of having voted for these parties, between the lower and upper classes, are relevant. The graphical representation of these results is shown in Supplementary Figure S1.

23.^The findings concerning the kappa index values are in keeping with those of Langsæther (2019). However, it is not possible to directly compare these values in the two studies due to the different sets of countries considered and the different operationalizations of the dependent variable in each study. Moreover, the author operationalizes the set of sociocultural values differently and applies a diverse class schema.

24.^The graphical representation of these results is provided in Supplementary Figure S2.

25.^As regards to sociocultural professionals, their preference for policies close to the liberal pole of the economic conservatism continuum is associated with social conservative stances (see Supplementary Table S2). Their likelihood to have voted for left-wing or right-wing party families is better understood by controlling for the political attitudes concerned. Indeed, this class shows pro-immigrant and pro-EU stances as well as a low degree of distrust of the political system.

26.^According to Rennwald (2020), the working classes' vote in Western Europe general elections is contested by social-democratic and radical right parties in the main, and less often by radical left actors.

References

1

Abou-ChadiT.WagnerM. (2020). Electoral fortunes of social democratic parties: do second dimension positions matter?J. Eur. Public Policy27, 246–272. 10.1080/13501763.2019.1701532

2

ArikanG.SekerciogluE. (2019). Authoritarian predispositions and attitudes towards redistribution. Polit. Psychol.40, 1099–1118. 10.1111/pops.12580

3

BakkerR.HoogheL.JollyS.MarksG.PolkJ.RovnyJ.et al. (2020). 1999 – 2019 Chapel Hill Expert Survey Trend File, Version 1.2. Available online at: chesdata.eu (accessed April 6, 2022).

4

ByrneB. M.ShavelsonR. J.MuthénB. (1989). Testing for the equivalence of factor covariance and mean structures: the issue of partial measurement invariance. Psychol. Bull.105, 456–46610.1037/0033-2909.105.3.456

5

CrowsonH. M.. (2009). Are all conservatives alike? A study of the psychological correlates of cultural and economic conservatism. J. Psychol.143, 449–463. 10.3200/JRL.143.5.449-463

6

DaltonR.. (2018). Political Realignment: Economics, Culture, and Electoral Change. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

7

ElffM.. (2009). Social divisions, party positions, and electoral behaviour. Elect. Stud.28, 297–308. 10.1016/j.electstud.2009.02.002

8

EnyediZ.. (2008). The social and attitudinal basis of political parties: cleavage politics revisited. Eur. Rev.16, 287–304. 10.1017/S1062798708000264

9