- 1Juniata College, Huntingdon, PA, United States

- 2University of North Georgia, Dahlonega, GA, United States

Based on our observations and scholarship about how democratic norms are currently being undermined, we propose a model of fascist authoritarianism that includes authoritarianism, the production and exaggeration of threats, conspiracy-oriented propaganda adoption, and distrust of reality-based professions. We refer to this as the Fascist Authoritarian Model of Illiberal Democracy (FAMID) and argue that all components are essential for understanding contemporary antidemocratic movements. We demonstrate that all components of FAMID correlate with illiberal antidemocratic attitudes, that Republicans generally score higher than Democrats on the model components, and that all components significantly contribute to predicting illiberal antidemocratic attitudes. We find approximately equal support for both left-wing and right-wing illiberal antidemocratic attitudes. The fascist authoritarian model of illiberal democracy helps explain the basic mechanisms by which an authoritarian leader works to erode liberal democratic norms—and does a better job at doing so than simpler authoritarianism theories.

The fascist authoritarian model of illiberal democracy

Political psychology research on authoritarianism has often focused on a measure of authoritarianism, a measure of perceived threat, and some measure of antidemocratic attitudes or behaviors (e.g., prejudice, support for ethnic persecution, etc.). We argue that while important, this focus fails to account for important mechanisms necessary for understanding how liberal democratic norms are undermined. We develop and test a more thorough model specifically meant to explain contemporary illiberal antidemocratic attitudes. Our proposed fascist authoritarian model of illiberal democracy (FAMID) includes authoritarianism, perceptions of “others” as threatening, conspiracy-oriented propaganda adoption, and distrust of reality-based professions as essential ideological beliefs that undermine liberal democratic norms.

Authoritarianism developed as a research focus in political psychology specifically to help understand the appeal of antidemocratic beliefs. In the wake of WWII and Nazi atrocities, early authoritarianism theory specifically focused on understanding “fascist receptivity” (Adorno et al., 1950, p. 279), especially to ethnocentrism. From this perspective, ethnocentrism was inherently antidemocratic because it could result in differential treatment based on identity characteristics such as ethnicity, religion, etc. The rule of law, a foundational principle of a liberal democracy, is predicated upon the idea that everyone is treated equally regardless of such identity characteristics.

Authoritarianism research, starting with Adorno et al. (1950), has shown a consistent relationship between measures of authoritarian ideology and various measures of prejudice (e.g., Altemeyer, 1981; McFarland, 2010; Dunwoody and Funke, 2016; Duckitt and Sibley, 2017; Dunwoody and McFarland, 2018). Similarly, the relationship between authoritarianism and threat perception is well documented (Feldman, 2003; Hetherington and Suhay, 2011; Duckitt and Sibley, 2017; Dunwoody and Plane, 2019), as are the relationships between authoritarianism and support for antidemocratic behaviors including political intolerance (Feldman, 2003), restrictions on civil liberties (Cohrs et al., 2005; Hetherington and Weiler, 2009; Dunwoody and Funke, 2016), and support for political violence (Dunwoody and McFarland, 2018; Dunwoody and Plane, 2019).

While the above research paints a convincing picture about the roles of authoritarianism and threat perception in predicting support for illiberal antidemocratic tendencies, there are likely additional factors that help explain support for such tendencies.

Stanley (2015, 2018) discusses the explicit role of propaganda in undermining liberal democracy. He argues that propaganda prevents democratic deliberations from being possible by hiding undemocratic realities. As an example, Stanley (2015) cites polling data showing that most white people believe that a Black person is just as likely to get a job as a white person, given equal qualifications. Given the overwhelming empirical evidence that this is not true, the belief in equal opportunity prevents democratic deliberations about systemic racism and inequality. As such, propaganda serves the explicit function of hiding inequality and thwarting democratic discussion of it. To adopt the language of social dominance theory (Sidanius and Pratto, 1999), propaganda serves the role of a hierarchy legitimizing myth because it works to maintain inter-group hierarchies.

Similarly, Rauch (2021) argues that our current political polarization is due in part to a widespread attack on reality-based professions. These include professions whose traditional role is to delineate fact from fiction such as journalism, science, and academia. The practices and norms that form what Rauch calls “the constitution of knowledge” have been eroded by the explosive growth of information in new media that has failed to engage in traditional forms of truth monitoring such as peer review, ethical guidelines from professional organizations, etc. In the absence of such practices, false information spreads faster than truth. Because the Internet can provide an echo chamber of falsehoods, entire groups can become increasingly disconnected from reality as they choose alternatives to traditional, reality-based professions.

There is an obvious connection between delegitimizing reality-based professions, propaganda, and authoritarianism. Vladimir Putin is credited with perfecting a tactic known as the firehose of falsehoods (Illing, 2020), a deliberate strategy to flood the information zone with so much misinformation that determining fact from fiction becomes too difficult for the average person. In such an environment, anyone can claim that an election is rigged because significant segments of the population no longer trust the traditional arbiters of truth (e.g., journalists, judges, scientists, etc.) and some have given up on the idea that the truth is even knowable.

The firehose of falsehoods was adopted and used effectively by the Donald Trump administration. In 2018, Steve Bannon, one of Trump's key strategists, colorfully referred to this tactic when he said, “The real opposition is the media. And the way to deal with them is to flood the zone with shit” (Illing, 2020). The Washington Post documented 30,573 false claims made by Trump during his presidency (Kessler et al., 2021). This is a deliberate authoritarian tactic and should be considered as one of the key psychological mechanisms by which liberal democratic norms are undermined.

When leaders employ a firehose of falsehoods, citizens retreat into cynicism and the belief that the truth is fundamentally unknowable. If the truth is unknowable, reasoned debate is pointless because there are no agreed-upon facts. For example, Trump advisor Kellyanne Conway referred to “alternative facts” when questioned about false and misleading claims related to Trump's inauguration (Blake, 2020). When reasoned democratic discourse is not possible because there are no agreed upon facts, all that is left is the political exercise of raw power. This strategy is consistent with political psychology research showing that epistemic and existential uncertainty motivate the adoption of conservative and authoritarian beliefs (Jost et al., 2003, 2007).

We propose a broader model of authoritarianism that includes not only authoritarianism and perceptions of threat, but also the adoption of conspiracy-oriented propaganda beliefs and a distrust of reality-based professions typically responsible for holding the powerful accountable. It is our argument that these four components make up core elements of authoritarian ideology and collectively contribute to the adoption of illiberal antidemocratic attitudes in the population. To differentiate this broader model from simpler models of authoritarianism, we refer to it as the fascist authoritarian model of illiberal democracy.

The fascist authoritarian model of illiberal democracy (FAMID)

Fascist authoritarianism

Authoritarianism has been defined as a personality trait (Adorno et al., 1950), a set of social attitudes (Altemeyer, 1981), and an expression of values (Feldman, 2003; Stenner, 2005; Duckitt et al., 2010). However, we consider authoritarianism to be an ideology. This is consistent with Jost's (2006, p. 653) definition of ideology as “a belief system of the individual that is typically shared with an identifiable group and that organizes, motivates, and gives meaning to political behavior broadly construed” (2006, p. 653).

Specifically, we refer to fascist authoritarianism to mean the belief system that includes not only authoritarianism, but also includes fascist elements: the perception of “others” as threatening (threat othering), the adoption of conspiracy-oriented propaganda, and a distrust of reality-based professions (truth delegitimization). Our central argument is that this collective set of ideological beliefs lead people to support illiberal antidemocratic practices.

We use the phrase fascist authoritarianism to differentiate our model from simpler theories and measures of authoritarianism that focus only on the identification of a trait (e.g., personality, attitudes, values, etc.). We also do so to explicitly reference the works of Stanley, including How Fascism Works (2018) and How Propaganda Works (2015), which provide significant inspiration for our FAMID. Stanley uses fascism and authoritarianism as synonyms. His work is an excellent synopsis of modern fascism, how it is rooted in local cultural beliefs, and the role of threat and propaganda in undermining liberal democracies.

Threat othering

Authoritarian leaders must create or elevate the enemies that justify their use of power. Put another way, perceived threats help to justify the expanded powers that authoritarians say they need to effectively counter those threats. This is why the free press, academics, and minorities are elevated to the position of existential threats by authoritarian leaders and promoted as such by cooperating propaganda outlets. Authoritarian leaders seem to intuitively understand that extremism creates extremism. By elevating their critics and political opponents to the level of existential threats in the eyes of their followers, they radicalize their followers for political gain.

For example, Trump helped to manufacture the so-called Big Lie, which was the false claim that the election was stolen from him. By painting Democrats and members of Congress as threats to the country, he was able to radicalize his own followers in the hopes of overturning the election. The result was the attack on the U.S. Capitol on January 6th, 2021 (Block, 2021).

Similarly, Trump frequently referred to Black Lives Matter protesters (who were overwhelmingly peaceful) as thugs, terrorists, and anarchists (Beer, 2021). He referred to immigrants as rapists, drug-dealers, and criminals and regularly attacked the press as disgusting people who were a threat to democracy (Kalb, 2018; Wolf, 2018). Furthermore, those with anti-immigration beliefs can easily depict immigrants as harbingers of diseases (Herrera, 2019) such as COVID. We refer to this process as threat othering because it creates affective and emotional responses in people that make them fearful of immigrants and angry at their fellow citizens. The skillful demagogue exploits emotional reactions to threat as a way to gain more political power.

Truth delegitimization

The deliberate undermining of objective notions of truth are central to authoritarianism because obedience to authoritarian leaders requires total submission to their chosen fictional narratives. Authoritarian leaders must assert that their chosen fiction is correct, despite any and all evidence to the contrary. Arendt (1951) argued that submission to this fiction is the essential element of totalitarianism. It is for this reason that authoritarians must delegitimize professions which focus on establishing and validating the public's understanding of the truth. By delegitimizing the professions that help the public understand the true state of the world, authoritarian leaders undermine professions which might hold them accountable for abuses of power. If the truth is fundamentally unknowable, democratic discourse, debate, and compromise is futile (Stanley, 2015; Rauch, 2021). Instead, democratic discourse and process is replaced with tribalism and the raw exercise of political power that is unchecked by the rule of law. Professionals who traditionally establish what is widely accepted as true include academics, judges, scientists, and journalists.

Conspiracy-oriented propaganda adoption

Authoritarian leaders use the tools of threat othering and truth delegitimization to gain the power they argue is necessary to crush the perceived threats they themselves have helped to create in the eyes of the public. However, this is only possible to the extent that the public believes this narrative and adopts fictitious beliefs that invent or exaggerate the threat posed by others. Falsehoods that elevate the public's threat level include beliefs that immigrants are mostly criminals who bring diseases, that BLM is a terrorist group, that political parties want to destroy America, that the media and academics are conspiring to mislead the public, etc. While false beliefs about COVID are widespread, it is important to realize that the false beliefs do not need to be about a specific target. Rather, a flood of falsehoods creates in some the belief that nothing is truly knowable. This epistemic vacuum can then be filled with authoritarian fictions.

Propaganda designed to increase threat perceptions often takes the form of conspiracy theories. Agitation propaganda specifically works to motivate popular masses toward some collective action through adoption of conspiracy beliefs (Marmura, 2014). Like authoritarianism (Jost et al., 2007), the adoption of conspiracy beliefs can serve epistemic, existential, and social needs (Douglas et al., 2017).

Illiberal democracy

Liberal democracy refers to a system of government that emphasizes free and fair elections, the protection of civil liberties, and the rule of law. Victor Orban has promoted what some refer to as illiberal democracy (Plattner, 2019) as he worked to deliberately distance himself and Hungary from liberal democracies. An illiberal democracy is a contradiction in that it works to preserve the appearance of democratic elections and civil liberties while actively undermining the mechanisms that would otherwise ensure fair elections, the rule of law, and civil liberties.

Illiberal democracies elect leaders but do little to universally protect civil liberties or limit the power of elected officials, allowing them to break the law with impunity. Donald Trump indicated that he was not capable of breaking the law simply because he was president, stating “I have an Article II [of the Constitution], where I have the right to do whatever I want as president” (Brice-Saddler, 2019). This is a fundamentally illiberal argument and threatens foundational principles of liberal democracy. A leader who can break the law with impunity operates in a system that is democratic in name only.

One critique of authoritarianism research is that the construct has been used so widely that it has little theoretical guidance (Feldman, 2003). We agree with this critique. All scientific theories should have an explicitly limited scope of phenomena that they aim to explain. Failure to do so results in theories that have no clear application boundaries and are thus vague. Our explicit focus is the explanation of illiberal antidemocratic attitudes and behaviors. Based on the definition of liberal democracy, these include support for large-scale restrictions on civil liberties (especially of specific groups), policies or actions that target citizens based on identity characteristics (e.g., religion, skin color, ethnicity heritage, etc.), violations of the rule of law by ingroup members and leaders, and support for violence or the threat of violence to achieve one's political goals.

Another critique of authoritarianism is that it often focuses on right-wing authoritarianism and not left-wing authoritarianism. Indeed, Altemeyer (1981) measure is called right-wing authoritarianism. To address this critique, we include support for both right-wing and left-wing illiberal attitudes.

The current study

Authoritarian leaders have used recent events across the globe such as terrorism, immigration, the Black Lives Matter civil rights movement, and the COVID-19 pandemic to advance the mechanisms of threat othering, truth delegitimization, and conspiracy-oriented propaganda adoption to promote illiberal democracy. Our central theoretical proposal is that these components are central to the erosion of liberal democratic norms and increased support for illiberal antidemocratic norms.

We remain agnostic regarding the causal direction between authoritarianism and threat as there is evidence for a bidirectional causal relationship between them (Onraet et al., 2014). We believe that similar bidirectional relationships may be possible with not just authoritarianism and threat, but also truth delegitimization and conspiracy-oriented propaganda adoption. As such, we adopt a simple additive model to test the unique contributions of authoritarianism, threat othering, truth delegitimization, and conspiracy-oriented propaganda adoption in predicting illiberal antidemocratic attitudes.

To test the fascist authoritarian model of illiberal democracy, we created a list of illiberal antidemocratic attitudes (e.g., restrictions on civil liberties of specific groups, support for violence, etc.) that might be held by both left- and right-wing individuals in the United States on topics such as COVID-19, Black Lives Matter, the teaching of critical race theory, and the 2020 U.S. presidential election.

Hypotheses

H1: All components of the Fascist Authoritarian Model of Illiberal Democracy will be correlated in the expected directions. We expect authoritarianism to not only be positively correlated with measures of threat othering and illiberal democracy, but also with conspiracy-oriented propaganda adoption and truth delegitimization.

H2: Threat othering will be a function of group membership such that outgroups, or those proposing ideas associated with outgroups, will be viewed as more threatening than will ingroups. To demonstrate the targeted nature of threat perception and the impact of threat othering, we predict that Republicans and Democrats will perceive threats from others asymmetrically based on ingroup-outgroup distinctions.

We predict that Republicans will perceive greater threat than will Democrats from those approving mask and vaccine mandates and how Democrats handled of the 2020 election. Conversely, we predict Democrats will perceive greater threat than will Republicans from those opposing mask and vaccines mandates and how Republicans handled the 2020 election.

H3: Left-leaning participants will express more support for left-leaning, anti-democratic ideas than will right-leaning participants. Right-leaning participants will express more support for right-leaning, anti-democratic ideas than will left-leaning participants. Authoritarianism research has focused on right-wing related violence. Stanley (2018) makes the point that fascist movements are rooted in cultural norms that hark back to the past. While the U.S. context is one that appears more welcoming to the growth of right-wing illiberal, anti-democratic attitudes, there appears to be growing support on the left for political intolerance evidenced by so-called cancel-culture (Rauch, 2021). We believe it is important to consider the possibility that illiberal antidemocratic attitudes on one side of the ideological spectrum might promote equally illiberal antidemocratic attitudes on the other. For example, The Weimer Republic saw the growth of not just the illiberal Nazi Party, but concurrently the growth of the illiberal Communist Party. As such, we consider illiberal antidemocratic attitudes likely held by those on the political left and right.

H4: Republicans will have higher average scores for authoritarianism, truth delegitimization, conspiracy-oriented propaganda adoption, and illiberal democracy items than will Democrats. Significant past research has not only shown that authoritarianism is linked with the political right in the U.S., it has also shown that authoritarianism has become the main driver of party sorting (Hetherington and Weiler, 2009) and that the Republican Party became significantly more illiberal under Trump (Luhrmann et al., 2020). As such, we test to see if Republicans show greater endorsement of the components of our Fascist Authoritarian Model of Illiberal Democracy than do Democrats.

H5: Truth delegitimization and conspiracy-oriented propaganda adoption will explain more variance than will the more typical model of authoritarianism and threat perception in predicting illiberal antidemocratic attitudes. If our model is correct, then propaganda adoption and truth delegitimization will add statistically and substantively to explaining support for illiberal antidemocratic attitudes over and above the contribution of authoritarianism and threat perception demonstrated in previous research. Our central claim is that this fuller model of fascist authoritarianism is needed to better account for the undermining of liberal democratic norms.

H6: Authoritarianism, threat othering, truth delegitimization, and conspiracy-oriented propaganda adoption will all be unique predictors of illiberal antidemocratic attitudes. Although we expect the components of our model to all correlate, we also expect them to all remain significant unique predictors of illiberal antidemocratic attitudes.

Methods

Procedure

A survey including basic demographic and 70 agree-disagree questions was administered at several colleges and universities in the northeastern, southeastern, and southwestern United States from January 10 to February 17, 2022. All participants were told that survey completion was voluntary, would take ~10–15 min, and that they would be entered into a drawing for a $100 gift card. Students, faculty, and staff were all free to participate. Participants completed the survey through Qualtrics.

Participants

Five hundred and five participants completed enough questions to be included in at least some of the analyses. Seventy-five percent of participants identified as students, 6% as faculty, 15% as staff/administrators, and 1% as other. Ages ranged from 18 to 73 with an median age of 21 (M = 27.6, s = 13.3). One-hundred and thirty-two participants identified as male, 328 as female, and 20 as non-binary. For racial/ethnic identity, participants were able to select more than one category and as such, the total exceeds the number of participants; 387 identified as white, 53 as other/multiple, 27 as Asian, 26 as Black or African American, 13 as American Indian or Alaskan Native, and 3 as Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. The sample leaned liberal with 51% percent of participants self-identifying as liberal or strongly liberal and only 15% identified as conservative or strongly conservative.

Measures

Responses to all scale items described below are on a five-point scale (minimum = 1, maximum = 5). See the Appendix for additional details about the various measures and scales used in this analysis.

Authoritarianism

To measure authoritarianism, we used the Aggression-Submission-Conventionalism (ASC) scale (Dunwoody and Funke, 2016). This scale is based on Altemeyer's (1981) theory of authoritarianism but includes independent subscales for authoritarian aggression, authoritarian submission, and conventionalism. The ASC scale had acceptable reliability (M = 2.57, s = 0.47, alpha = 0.81). The subscales varied in reliability but were all acceptable (ASC Aggression: M = 2.49, s = 0.71, alpha = 0.78; ASC Submission: M = 2.38, s = 0.56, alpha = 0.81; ASC Conventionalism: M = 2.83, s = 0.70, alpha = 0.79). When predicting left-leaning antidemocratic attitudes, we used only the Aggression and Submission subscales since Conventionalism is explicitly linked with right-leaning ideology. The Aggression-Submission (AS) scale also produced acceptable reliability (AS scale: M = 2.44, s = 0.48, alpha = 0.72).

Threat othering

We created four different three-part questions designed to measure the threat level perceived from different groups. These included people who are actively promoting COVID masks and vaccine mandates (M = 1.77, s = 1.10, alpha = 0.93), people who are actively opposing COVID masks and vaccine mandates (M = 3.45, s = 1.29, alpha = 0.88), how the Democrats handled the 2020 presidential election (M = 2.22, s = 1.14, alpha = 0.88), and how Republicans handled the 2020 presidential election (M = 3.51, s = 1.25, alpha = 0.90).

Each question asked participants to indicate how concerned they were that the group was disrupting American norms and values (symbolic threat), dangerous because they threaten our physical safety (existential threat), and wasting resources that could be used by other Americans in need (realistic threat). Participants responded on a five-point scale from not at all concerned to extremely concerned.

Conspiracy-oriented propaganda adoption

We created a 17-item scale made of claims found in the public sphere that were either demonstrably false or lacked supporting evidence. Eleven of these statements were conspiracy theories about COVID, four were conspiracy beliefs about the 2020 U.S. presidential election or the January 6th insurrection, and one was a statement that most college and university professors were communists who hated America. Despite the wide-ranging nature of these false and propagandistic beliefs, reliability was high (M = 1.80, s = 0.85, alpha = 0.95).

Truth delegitimization

We created an 11-item scale with items that measured people's trust or distrust in scientists, the media, journalists, and academics. Again, reliability was high (M = 3.30, s = 0.61, alpha = 0.86).

Illiberal antidemocratic attitudes

Participants were asked to indicate how much they agreed or disagreed with a series of statements we viewed as illiberal and antidemocratic on a five-point scale anchored by strongly disagree and strongly agree. These items include statements that limit the rights of others or either explicitly or implicitly support violence against others. We calculated averages across all illiberal antidemocratic items (M = 1.78, s = 0.56, alpha = 0.83), only those we viewed as left-leaning (M = 2.08, s = 0.87, alpha = 0.82), and only those we viewed as right-leaning (M = 1.61, s = 0.71, alpha = 0.90).

Results

H1: All components of the Fascist Authoritarian Model of Illiberal Democracy will be correlated in the expected directions.

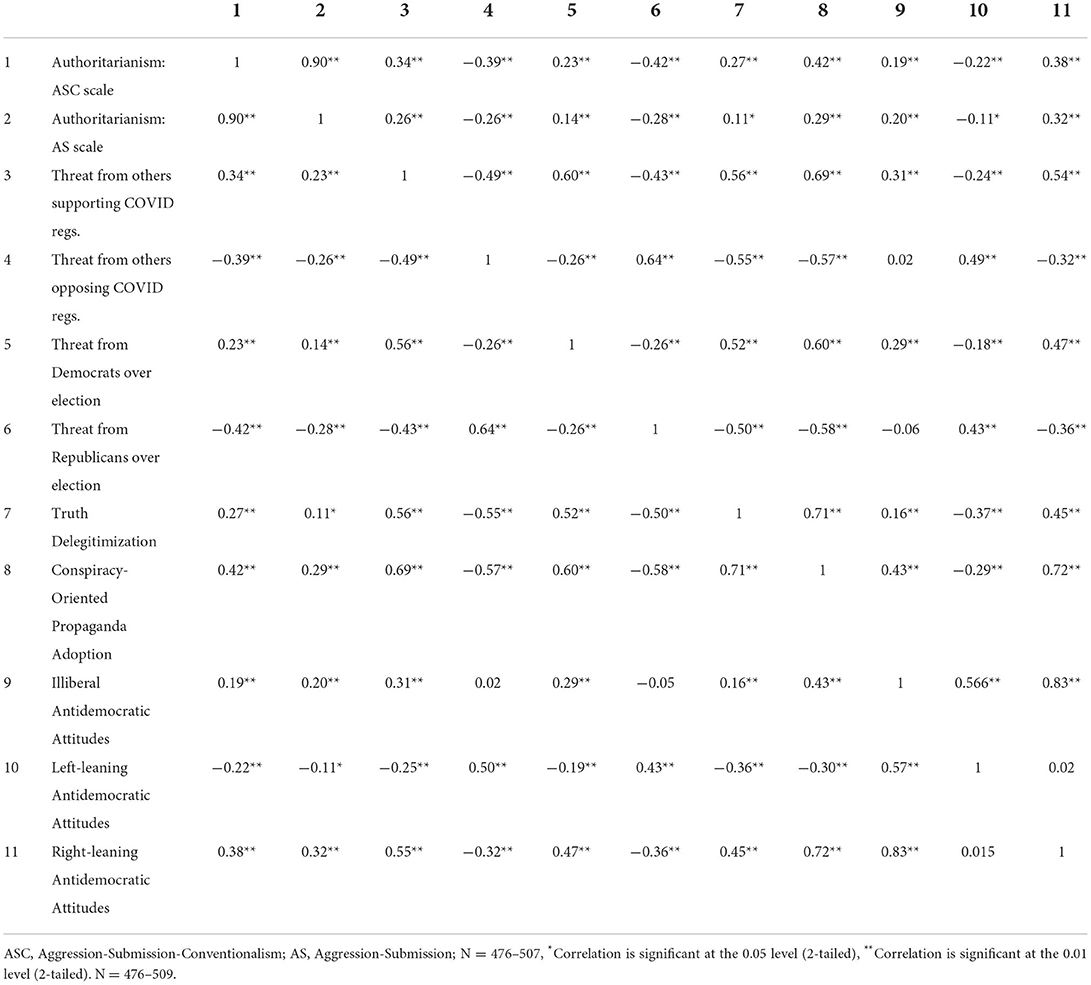

All measures of the proposed fascist authoritarian model of illiberal democracy are correlated in the predicted direction when examining correlations with left and right-leaning illiberal antidemocratic tendencies. When examining correlations with general illiberal antidemocratic tendencies (which combine those leaning left and right), most of the variables are still significant and all are in the predicted direction. Interestingly, right- and left-leaning illiberal antidemocratic tendencies are not correlated.

Several variables used as predictors of illiberal antidemocratic correlated between 0.5 and 0.7. Truth delegitimization and propaganda adoption are highly correlated at 0.71, which we believe impacted the regression coefficients generated in later hypothesis tests. See Table 1 for correlations.

H2: Threat othering will be a function of group membership such that outgroups, or those proposing ideas associated with outgroups, will be viewed as more threatening than ingroups.

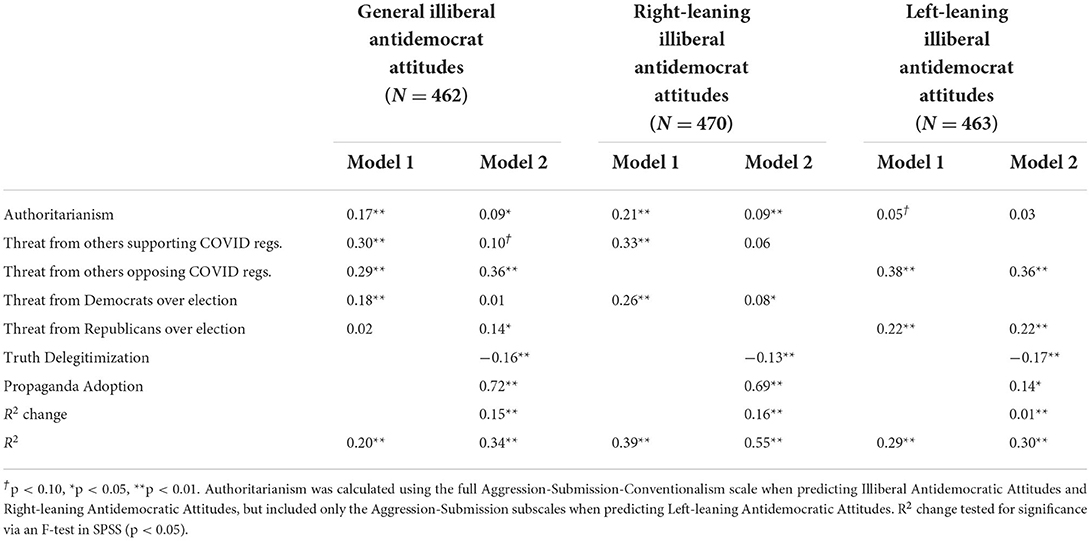

As predicted, Republicans perceived those who support COVID regulations as more threatening than did Democrats. Conversely, Democrats perceived those who oppose COVID regulations as more threatening than did Republicans.

Likewise, Republicans perceived Democrats' handling of the 2020 U.S. presidential election as more threatening than did Democrats. Conversely, Democrats perceived Republicans' handling of the 2020 U.S. presidential election as more threatening than did Republicans. See Table 2 for descriptive and inferential statistics.

Table 2. Comparison of democrats and republicans on fascist authoritarianism model of illiberal democracy variables.

H3: Left-leaning participants will express more support for left-leaning antidemocratic ideas than will right-leaning participants. Right-leaning participants will express more support for right-leaning antidemocratic ideas than will left-leaning participants.

As predicted, liberal-conservative self-identification, with low values indicating liberalism and high values conservatism, was positively correlated with right-leaning illiberal antidemocratic items (r = 0.45, p < 0.01, n = 485) and negatively with left-leaning illiberal antidemocratic items (r = −0.42, p < 0.01, n = 489). These correlations are almost equal in strength.

H4: Republicans will have higher average scores for authoritarianism, truth delegitimization, conspiracy-oriented propaganda adoption, and illiberal democracy items than will Democrats.

As predicted, Republicans had higher scores on authoritarianism, conspiracy-oriented propaganda adoption, truth delegitimization, and general illiberal antidemocratic items than did Democrats (see Table 2 for descriptive and inferential statistics). However, support for left-leaning and right-leaning illiberal antidemocratic practices varied in predictable ways with Republicans showing greater support for right-leaning practices and Democrats greater support for left-leaning practices. Republican support of right-leaning illiberal antidemocratic practices is almost identical to Democratic support for left-leaning illiberal antidemocratic practices. Although Republicans had higher scores on the total Aggression-Submission-Conventionalism scale, only the Aggression and Conventionalism subscales were significantly different.

H5 and H6: Truth delegitimization and conspiracy-oriented propaganda adoption will explain more variance than the more typical model of authoritarianism and threat perception in predicting illiberal antidemocratic attitudes. Authoritarianism, threat othering, truth delegitimization, and conspiracy-oriented propaganda adoption will all be unique predictors of illiberal antidemocratic attitudes.

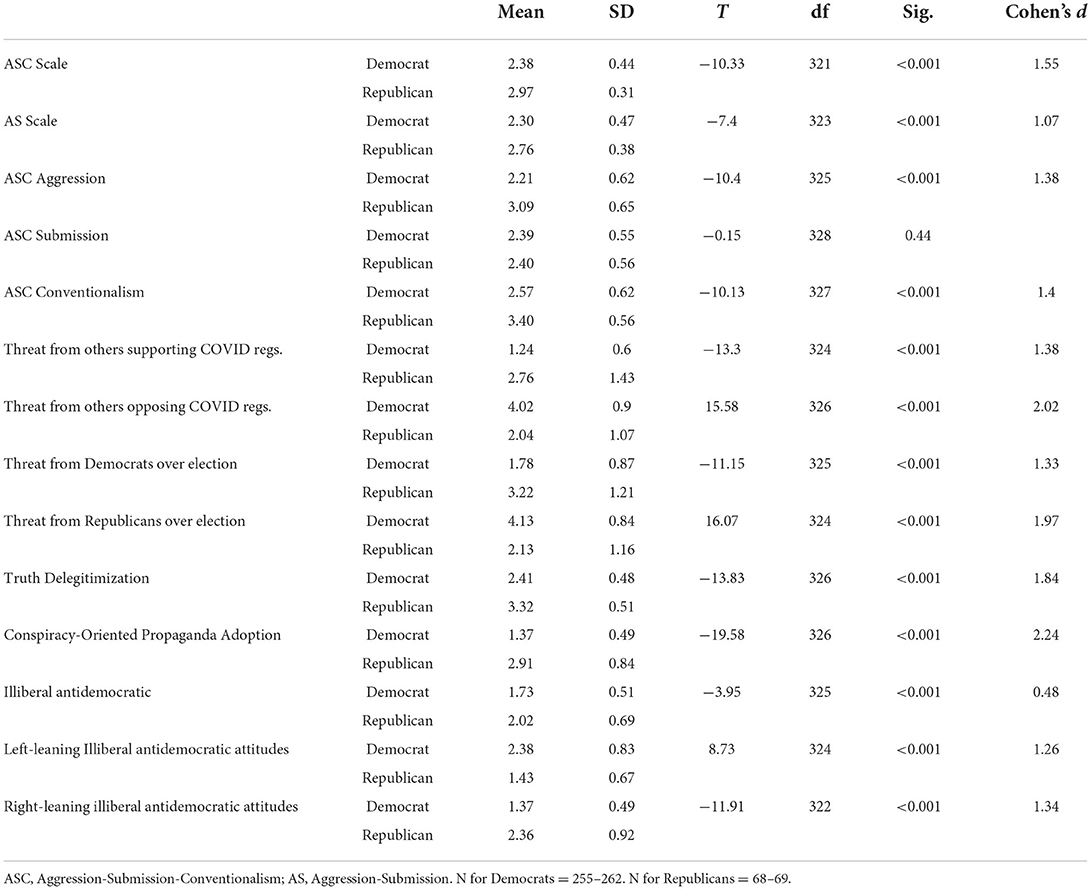

We computed several hierarchical ordinary least squares regression models to test the above claims, which we view as central to the FAMID. The first test ignored ideological differences (i.e., left-leaning vs. right-leaning) in support for illiberal antidemocratic practices. As such, we assume this model will underestimate the variance accounted for.

The first column of Table 3 shows that the general test of Model 1 works as predicted. Authoritarianism and three of the four threat measures in Model 1 are unique predictors of general illiberal antidemocratic attitudes. Model 2 adds truth delegitimization and propaganda adoption, resulting in an increase in the variance accounted for from 20 to 34% [Fchange (2, 454) = 50.83, p < 0.01] as shown in the second column of Table 3.

We then recomputed the models to predict right-wing illiberal antidemocratic attitudes (the middle two columns in Table 3) and then again to predict left-wing illiberal antidemocratic attitudes (the rightmost two columns in Table 3). This provided specific applications in predicting both right-wing and left-wing illiberal antidemocratic attitudes.

The model proved even more robust in predicting right-leaning illiberal antidemocratic attitudes with authoritarianism and threat perception accounting for a total of 39% of the variance. The inclusion of distrust of reality-based professions and conspiracy-oriented propaganda adoption increased the variance accounted for significantly and substantively from 39 to 55% [Fchange (2, 457) = 80.21, p < 0.01].

The model was less able to account for left-leaning antidemocratic attitudes. Authoritarianism and threat perception predicted 29% of the variance in left-wing illiberal antidemocratic attitudes with only the measures of threat perception as significant contributors. Adding propaganda adoption and truth delegitimization significantly increased the variance accounted for, but only from 29 to 30% [Fchange (2, 464) = 4.75, p < 0.01].

The standardized Beta weights are all in the predicted direction except for the contribution of truth delegitimization. The sign indicates that as the participants gained truth delegitimizing beliefs, they were less likely to support illiberal antidemocratic practices.

As shown in Table 1, truth delegitimization was negatively correlated with left-leaning illiberal antidemocratic attitudes (r = −0.38), and positively correlated with support for general illiberal antidemocratic attitudes (r = 0.31) propaganda adoption (r = 0.71), and right-leaning illiberal antidemocratic attitudes (r = 0.45). It is interesting to note that those most supportive of right-leaning illiberal antidemocratic practices have high levels of distrust in reality-based professions while those most supportive of left-leaning illiberal antidemocratic practices have low levels of distrust (i.e., high levels of trust) in reality-based professions.

We believe the negative regression weight of truth delegitimization in Table 3 may be a statistical artifact caused by the high correlation between truth delegitimization and propaganda adoption (r = 0.71), making one or both variables unstable. Given the high correlation and conceptual relationship between distrust of reality-based professions and adoption of conspiracy-oriented propaganda, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis to see if items from these two scales loaded onto a common factor and might be combined into a single measure. This produced one large factor (Eigenvalue = 12.27) accounting for about 44% of the total variance containing all conspiracy-oriented propaganda items, but only some items measuring truth delegitimization. Truth delegitimization items mostly loaded onto several other lesser factors (Eigenvalues of 2.2 or lower, variance <8%). As such, we did not combine these items into a single measure.

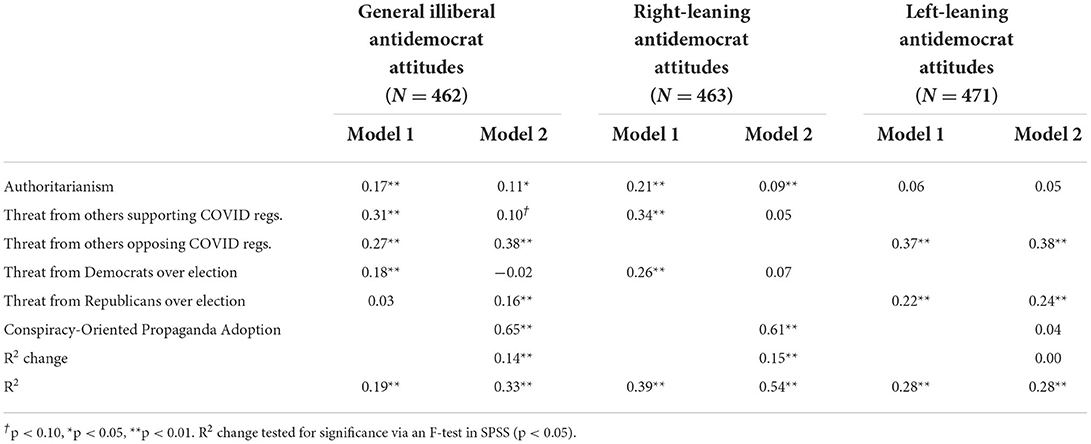

We reran our regression analyses to explore how the removal of truth delegitimization would impact our results. The results in Table 4 are largely consistent with those shown in Table 3. Table 4 shows that the main unique contributors of left-leaning and right-leaning illiberal antidemocratic practices are different. Left-leaning illiberal antidemocratic practices stem mostly from the perception of threat posed by Republicans while right-leaning illiberal antidemocratic practices stem mostly from conspiracy-oriented propaganda beliefs. However, it is important to note that the regression weights show unique variance and therefore are impacted by correlations among the items (see Table 1). Our measures of threat perception were moderately to strongly correlated with conspiracy-oriented propaganda beliefs.

Table 4. Standardized betas from hierarchical regression on illiberal antidemocratic attitudes without truth delegitimization.

While Table 4 shows that the addition of propaganda added significantly to general illiberal antidemocratic attitudes [Fchange (1, 455) = 93.28, p < 0.01] and right-leaning illiberal antidemocratic attitudes [Fchange (1, 458) = 150.70, p < 0.01], it did not add significant variance when explaining left-leaning antidemocratic attitudes [Fchange (1, 466) = 0.56, p = 0.46]. Importantly, comparing Tables 3, 4 shows that dropping truth delegitimization from the model resulted in only small decreases in R2 (usually by no more than 1%), an indication that little explanatory power was lost.

Discussion

We view the results of this study as generally supportive of our proposed fascist authoritarian model of illiberal democracy. In the general test of our model, all theorized components predicted unique variance in support for illiberal antidemocratic attitudes. Importantly, the addition of truth delegitimization and conspiracy-oriented propaganda adoption added statistically and substantively significant variance beyond that of authoritarianism and threat measures.

However, the strong correlation between our measures of truth delegitimization and conspiracy-oriented propaganda adoption (r = 0.71) means that the regression weights were unreliable when entered in the same model. Table 1 also shows that truth delegitimization beliefs related to support for right-leaning and left-leaning illiberal antidemocratic values differently. Support for right-leaning illiberal antidemocratic practices was positively correlated with distrust in reality-based professions while support for left-leaning illiberal antidemocratic practices was negatively correlated with distrust in reality-based professions. The relationship between distrust in reality-based professions and support for illiberal antidemocratic practices is more complicated than we hypothesized and deserves further exploration.

Rerunning our analyses without the inclusion of truth delegitimization produced similar results, but with some important caveats. While Table 3 shows all theorized components as significant unique predictors of both general and right-leaning illiberal antidemocratic attitudes, Table 4 shows all theorized components as significant unique predictors when explaining general illiberal antidemocratic attitudes, but not those that are left or right leaning. Right-leaning illiberal antidemocratic attitudes were best explained by authoritarianism and conspiracy-oriented propaganda beliefs, while left-leaning illiberal antidemocratic attitudes were best explained by perceptions of threat.

Despite the historical focus on right-wing authoritarianism, we found approximately equal support for left-wing and right-wing illiberal antidemocratic attitudes. We also found that the correlation of liberal-conservative self-identification with right-wing illiberal antidemocratic attitudes was equal in strength to that with left-wing antidemocratic attitudes. These findings are somewhat surprising given the historical focus on right-wing authoritarianism and extremism. It may be that perceived extremism of the ideological other promotes self-extremism. That is, liberals who perceive conservatives as extremely threatening are more likely to themselves become extreme, and conservatives who perceive liberals as extremely threating are more likely to themselves become extreme. In essence, extremism of the “other” justifies extremism of the self.

However, the simplified FAMID explained right-wing illiberal antidemocratic attitudes better than it explained left-wing antidemocratic attitudes by a margin of twenty-six percentage points (see Table 4). While we do not think that illiberalism is inherent to right-wing politics, our data come from the United States at the transition from the Trump to the Biden presidencies, a period in which Trump challenged various democratic norms and moved the Republican Party in an illiberal antidemocratic direction. The V-Dem Institute, which measures liberal and illiberal tendencies of countries and political parties, argues that the Republican Party has taken a drastic turn toward illiberalism. Their measure of illiberalism is based on the rhetoric of politicians and captures “low commitment to political pluralism, demonization of political opponents, disrespect for fundamental minority rights and encouragement of political violence.” They wrote that the Republican Party under Trump was “far more illiberal than almost all other governing parties in democracies” and that “its rhetoric is closer to authoritarian parties” (Luhrmann et al., 2020).

Given the large impact of conspiracy-oriented propaganda adoption in our regression models, it is possible that different media consumption habits explain why FAMID better explains right-wing than left-wing illiberal antidemocratic attitudes. While 48% of Democrats watched news sources with a mixed or right-leaning audience, only 34% of Republicans watched news sources with a mixed or left-leaning audience (Mitchell et al., 2021). Perhaps even more importantly, the only news outlet that more than 50% of Republicans trust is FOX News, while there are six different news sources that more than 50% of Democrats trust (Jurkowitz et al., 2020). Social media also plays an important role. Research on Twitter shows that false news spreads much faster than the truth (Vosoughi et al., 2018). Research about Facebook shows that far-right posts generate the highest per-follower interaction when compared with other groups and that far-right misinformation had almost twice the interaction rate of accurate information (Edelson et al., 2021). However, we cannot rule out the possibility that our measures of truth delegitimization and conspiracy-oriented propaganda adoption were more likely to measure right-leaning than left-leaning beliefs.

Van Hiel et al. (2006) have argued that left-wing authoritarianism is more common in Eastern Europe where there is a deeper tradition of communism. This is consistent with Stanley (2018) argument that populist movements are always rooted in the long-held traditional beliefs of a society. The U.S. and Western Europe are rooted more deeply in individualistic values compared to the collectivistic values found in East Asia. This difference implies that right-wing extremism will be readily found in the West and left-wing extremism in the East (for a detailed consideration of left- and right-wing authoritarianism, see Costello et al., 2022).

Republicans not only had higher scores on authoritarianism, but also on truth delegitimization, conspiracy-oriented propaganda adoption, and illiberal antidemocratic attitudes. Tables 3, 4 provide useful information regarding the relative contribution of each component in explaining illiberal antidemocratic attitudes. Standardized regression coefficients show conspiracy-oriented propaganda adoption as the largest contributing factor by a wide margin when measured separately from truth delegitimization.

Practically speaking, this might mean that the best way to counter illiberal antidemocratic tendencies in a population is through methods that decrease the likelihood of people adopting false, conspiracy-oriented propagandistic beliefs. Given the strong correlation with distrust of reality-based professions (truth delegitimization), reducing propagandistic beliefs is likely possible by increasing trust in what Rauch (2021) calls the reality-based professions.

In addition to an inverse relationship between authoritarianism and education, research clearly shows that a liberal arts education has an impact on reducing authoritarian attitudes (Simpson, 1972; Carnevale et al., 2020). We think it is likely that a liberal arts education also increases use of credible sources and trust in reality-based professions, while decreasing adoption of propagandistic beliefs. This suggests that in order to increase support for liberal democratic norms, we must explicitly cultivate the relevant capacities throughout our educational systems.

Limitations and future directions

An important caveat of our claims is that they were tested on a convenience sample that is non-representative of U.S. residents. Our sample is younger, more liberal, and more likely to be white than is the general population. As such, our claims are primarily about the relationship among the proposed variables in FAMID and not about their representativeness in the general population. That said, there is sufficient evidence elsewhere that conspiracy-oriented propaganda beliefs related to the January 6, 2021 attack on the U.S. Capitol are widespread (Lang, 2022); that misinformation about COVID and the 2020 presidential election is widespread (Cox, 2020); that Democrats and Republicans increasingly see the other party as a threat (Pew Research Center, 2014; Salvanto et al., 2021); and that trust in the media is low (Cox, 2020). Examples of these beliefs and attitudes can readily be found in polling data, journalistic reports, and commentary from political pundits. Our contribution in this research is to show how they operate collectively to undermine liberal democracy.

While we believe that the conceptual difference between truth delegitimization and conspiracy-oriented propaganda adoption is theoretically important, the utility of measuring them independently was not supported by the present study. Their high correlation means that our measures failed to substantively differentiate them, and little explanatory power was lost by excluding truth delegitimization from our model. As such, a more parsimonious conception includes only authoritarianism, threat othering, and conspiracy-oriented propaganda. Future research might consider how truth delegitimization and conspiracy-oriented propaganda are related causally and could be independently measured.

Despite a historic focus on right-wing authoritarianism, we demonstrated equal support for left-wing and right-wing illiberal antidemocratic attitudes. Similarly, the relationship between liberal-conservative self-identification was correlated equally with right-wing and left-wing illiberal antidemocratic attitudes. These findings suggest that future research should consider both left-wing and right-wing illiberalism. Specifically, FAMID predicts that perceived extremism of the “other” justifies self-extremism in the form of support for illiberal antidemocratic practices. Relatedly, Costello et al. (2022) argue that left- and right-wing authoritarianism share a common core that includes, among other things, support for coercion, aggression, and moral absolutism.

We encourage future research to focus not just on the measurement of an authoritarian trait, but to look more broadly at how a collective set of ideological beliefs works to undermine liberal democratic norms. We believe that this more socio-political lens is needed to realize how contemporary actors deliberately work to undermine liberal democratic norms in the public. Our proposed fascist authoritarian model of illiberal democracy is an attempt to focus research more on the applied problems of understanding how liberal democratic norms are undermined, and our findings highlight the important role of conspiracy-oriented propaganda beliefs.

The fascist authoritarian model of illiberal democracy in action

All the components of the fascist authoritarian model of illiberal democracy were evidenced in the recent 2020 U.S. presidential election. President Trump demanded ingroup conformity, personal submission, and the punishment of anyone who opposed him (authoritarianism); deliberately worked to delegitimize the press and courts as valid sources of truth (truth delegitimization); argued that immigrants, journalists, Democrats, and even some Republicans were a threat to the country (threat othering); and claimed that he both won the election and that there was widespread voter fraud (conspiracy-oriented propaganda adoption).

In classic authoritarian fashion, Trump sought to remain in power by asserting his preferred fiction over more objective realities promoted by those in traditional, truth-based professions. Trump engaged in threat othering to work up his base so that they would support the use of force to “save” their country. The result of these combined mechanisms was the support of blatantly illiberal antidemocratic behavior at the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021.

COVID-19 offered authoritarian leaders another platform to spread misinformation, delegitimize reality-based professions, and create or exaggerate the threat posed by others. As such, COVID-19 was exploited the same way a migrant crisis would be exploited, and via the same mechanisms.

This research makes a substantive contribution to the literature by explicating a matter of great practical importance to modern liberal democracies. The fascist authoritarian model of illiberal democracy helps explain the basic mechanisms by which an authoritarian leader works to erode liberal democratic norms—and does a better job at doing so than simpler authoritarianism theories. While the measurement of specific conspiracy-oriented propaganda and threat-related beliefs will vary situationally, FAMID offers a tool for conceptualizing the challenges to liberal democracy across contexts. It is a more complete framework by which to understand illiberal antidemocratic practices than a simple trait-based focus on authoritarianism and has greater explanatory power than models that only include authoritarianism and threat.

As the threat of authoritarianism and extremism grows, the importance of understanding its mechanisms cannot be overstated. It is our hope that FAMID provides a map not just for understanding how liberal democratic norms are undermined, but also how they can be reinforced to counter illiberal antidemocratic forces.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation pending Juniata College Institutional Review Board approval.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Juniata College Institutional Review Board. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2022.907681/full#supplementary-material

References

Adorno, T. W., Frenkel-Brunswik, E., Levinson, D. J., and Sanford, R. N. (1950). The Authoritarian Personality. New York, NY, U.S.A.: Harper and Brothers.

Beer, T. (2021). Trump called BLM protesters “thugs” but Capitol-storming supporters “very special.” Forbes. Available online at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/tommybeer/2021/01/06/trump-called-blm-protesters-thugs-but-capitol-storming-supporters-very-special/?sh=39cc3dd23465 (accessed July 13, 2022).

Blake, A. (2020). Kellyanne Conway's legacy: the “alternative facts”-ification of the GOP. Washington Post. Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/08/24/kellyanne-conways-legacy-alternative-facts-ification-gop/ (accessed July 13, 2022).

Block, M. (2021). The clear and present danger of Trump's enduring “Big Lie.” NPR. Available online at: https://www.npr.org/2021/12/23/1065277246/trump-big-lie-jan-6-election (accessed July 13, 2022).

Brice-Saddler, M. (2019). While bemoaning Mueller probe, Trump falsely says the Constitution give him “the right to do whatever I want.” Washington Post. Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/07/23/trump-falsely-tells-auditorium-full-teens-constitution-gives-him-right-do-whatever-i-want/ (accessed July 13, 2022).

Carnevale, A. P., Smith, N., Drazanova, L., Gulish, A., and Campbell, K. P. (2020). The Role of Education in Taming Authoritarian Attitudes. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Center for Education and the Workforce.

Cohrs, J. C., Kielmann, S., Maes, J., and Moschner, B. (2005). Effects of right-wing authoritarianism and threat from terrorism on restriction of civil liberties. Analyses Soc Issues Public Policy 5, 263–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-2415.2005.00071.x

Costello, T. H., Bowers, S. M., Stevens, S. T., Waldman, I. D., Tasimi, A., and Lilienfeld, S. O. (2022). Clarifying the structure and nature of left-wing authoritarianism. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 122, 135–170. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000341

Cox, D. A. (2020). Conspiracy theories, misinformation, COVID-19, and the 2020 election. Surv. Center Am. Life. Available online at: https://www.americansurveycenter.org/research/conspiracy-theories-misinformation-covid-19-and-the-2020-election/ (accessed July 13, 2022).

Douglas, K. M., Sutton, R. M., and Cichocka, A. (2017). The psychology of conspiracy theories. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 29, 538–542. doi: 10.1177/0963721417718261

Duckitt, J., Bizumic, B., Krauss, S. W., and Heled, E. (2010). A tripartite approach to right-wing authoritarianism: the authoritarianism-conservatism-traditionalism model. Pol. Psychol. 31, 685–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2010.00781.x

Duckitt, J., and Sibley, C. G. (2017). The dual process motivational model of ideology and prejudice. In C.G. Sibley and F.K. Barlow (Eds.), The Psychology of Prejudice (pp. 188–221). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Dunwoody, P. T., and Funke, F. (2016). The aggression-submission-conventionalism scale: testing a new three factor measure of authoritarianism. J. Soc. Pol. Psychol. 4, 571–600. doi: 10.5964/jspp.v4i2.168

Dunwoody, P. T., and McFarland, S. G. (2018). Support for anti-Muslim policies: the role of political traits and threat perception. Political Psychology. Available online at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111./pops.12405/full (accessed July 13, 2022).

Dunwoody, P. T., and Plane, D.L. (2019). The influence of authoritarianism and outgroup threat on political affiliations and support for antidemocratic policies. Peace Conflict J. Peace Psychol. 25, 198. doi: 10.1037/pac0000397

Edelson, L., Nguyen, M., Goldstein, I., Goga, O., Lauinger, T., and McCoy, D. (2021). Far-right news sources on Facebook more engaging. Cybersecurity for Democracy. Available online at: https://medium.com/cybersecurity-for-democracy/far-right-news-sources-on-facebook-more-engaging-e04a01efae90 (accessed July 13, 2022).

Feldman, S. (2003). Enforcing social conformity: a theory of authoritarianism. Pol. Psychol. 24, 41–74. doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00316

Herrera, J. (2019). Studies Show Fears About Migration and Disease are Unfounded. Los Angeles, CA: Pacific Standard. Available online at: https://psmag.com/news/studies-show-fears-about-migration-and-disease-are-unfounded (accessed July 13, 2022).

Hetherington, M. J., and Suhay, E. (2011). Authoritarianism, threat, and Americans' support for the war on terror. American J. Political Science, 55, 546–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00514.x

Hetherington, M. J., and Weiler, J. D. (2009). Authoritarianism and Polarization in American Politics. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Illing, S. (2020). “Flood the zone with shit”: How misinformation overwhelmed our democracy. Vox. Available online at: https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2020/1/16/20991816/impeachment-trial-trump-bannon-misinformation (accessed July 13, 2022).

Jost, J. T. (2006). The end of the end of ideology. Am. Psychol. 61, 651–670. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.7.651

Jost, J. T., Glaser, J., Kruglanski, A.W., and Sulloway, F.J. (2003). Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychol. Bull. 129, 339–375. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.339

Jost, J. T., Napier, J. L., Thorisdottir, H., Gosling, S. D., Palfai, T. P., Ostafin, B., et al. (2007). Are needs to manage uncertainty and threat associated with political conservatism or ideological extremity? Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 33, 989–1007. doi: 10.1177/0146167207301028

Jurkowitz, M., Mitchell, A., Shearer, E., and Walker, M. (2020). U.S. Media Polarization and the 2020 Election: A Nation Divided. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2020/01/24/democrats-report-much-higher-levels-of-trust-in-a-number-of-news-sources-than-republicans/ (accessed July 13, 2022).

Kalb, M. (2018). Enemy of the People: Trump's War on the Press, The New McCarthyism, and the Threat to American Democracy. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Kessler, G., Rizzo, S., and Kelly, M. (2021). Trump's false or misleading claims total 30,573 over 4 years. Washington Post. Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/01/24/trumps-false-or-misleading-claims-total-30573-over-four-years/

Lang, J. (2022). Half of U.S. Republicans believe the left led Jan. 6 violence: Reuters/Ipsos poll. Reuters. Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/world/us/half-us-republicans-believe-left-led-jan-6-violence-reutersipsos-2022-06-09/ (accessed July 13, 2022).

Luhrmann, A., Medzihorsky, J., Hindle, G., and Lindberg, S. I. (2020). New Global Data on Political Parties: V-Party. Gothenburg, Sweden: V-Dem Institute. Available online at: https://www.v-dem.net/static/website/img/refs/vparty_briefing.pdf (accessed July 13, 2022).

Marmura, S. M. E. (2014). Likely and unlikely stories: conspiracy theories in an age of propaganda. Int. J. Commun. 8, 1377–2395. Available online at: https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/2358/1220

McFarland, S. (2010). Authoritarianism, social dominance, and other roots of generalized prejudice. Pol. Psychol. 31, 453–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2010.00765.x

Mitchell, A., Jurkowitz, M., Oliphant, B., and Shearer, E. (2021). How Americans Navigated the News in 2020: A Tumultuous Year in Review. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2021/02/22/about-a-quarter-of-republicans-democrats-consistently-turned-only-to-news-outlets-whose-audiences-aligned-with-them-politically-in-2020/ (accessed July 13, 2022).

Onraet, E., Dhont, K., and Van Hiel, A. (2014). The relationship between internal and external threat and right-wing attitudes: a three-wave longitudinal study. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 40, 712–725. doi: 10.1177/0146167214524256

Pew Research Center (2014). Political Polarization in the American Public. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2014/06/12/political-polarization-in-the-american-public/ (accessed July 13, 2022).

Plattner, M. F. (2019). Illiberal democracy and the struggle on the right. J. Democracy 30, 5–19. doi: 10.1353/jod.2019.0000

Rauch, J. (2021). The Constitution of Knowledge: A Defense of Truth. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press.

Salvanto, A., Khanna, K., Backus, F., and Pinto, J. D. (2021). Americans See Democracy Under Threat – CBS News Poll. CBS News. Available online at: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/joe-biden-coronavirus-opinion-poll/ (accessed July 13, 2022).

Sidanius, J., and Pratto, F. (1999). Social Dominance. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139175043

Simpson, M. (1972). Authoritarianism and education: a comparative approach, Sociometry 35, 223–234. doi: 10.2307/2786619

Van Hiel, A., Duriez, B., and Kossowska, M. (2006). The presence of left-wing authoritarianism in Western Europe and its relationship with conservative ideology. Pol Psychol. 27, 769–793. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2006.00532.x

Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., and Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science 359, 1146–1151. doi: 10.1126/science.aap9559

Wolf, Z. B. (2018). Trump basically called Mexicans rapists again. CNN. Available online at: https://www.cnn.com/2018/04/06/politics/trump-mexico-rapists/index.html (accessed July 13, 2022).

Keywords: authoritarianism, fascism, threat, propaganda, conspiracy, democracy, illiberal, antidemocratic

Citation: Dunwoody PT, Gershtenson J, Plane DL and Upchurch-Poole T (2022) The fascist authoritarian model of illiberal democracy. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:907681. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.907681

Received: 30 March 2022; Accepted: 07 July 2022;

Published: 10 August 2022.

Edited by:

Kris Dunn, University of Leeds, United KingdomReviewed by:

Raynee Sarah Gutting, University of Essex, United KingdomSusan Banducci, University of Exeter, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2022 Dunwoody, Gershtenson, Plane and Upchurch-Poole. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Philip T. Dunwoody, ZHVud29vZHlAanVuaWF0YS5lZHU=

Philip T. Dunwoody

Philip T. Dunwoody Joseph Gershtenson

Joseph Gershtenson Dennis L. Plane

Dennis L. Plane Territa Upchurch-Poole1

Territa Upchurch-Poole1