- 1Institute of Social Sciences, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal

- 2Ronald F. Inglehart Laboratory for Comparative Social Research, HSE University, Moscow, Russia

- 3ISCTE, University Institute of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal

Belief systems are core organizing factors of social attitudes and behaviors, and their study has highlighted the role of conservatism as a contributing mechanism in mitigating concerns associated with change avoidance, as well as the reduction of uncertainty and ambiguity in life. Moreover, these aspects seem to be consistently used as powerful tools in the political and social discourse of the far-right. Life and death ethics are an example of issues that deal with the need for stability and control over personal and social life that people endorsing conservative values seek to attain. There is a rich line of studies on the individual and social explanatory factors of political conservatism, but less attention has been dedicated to moral conservatism as an autonomous and meaningful concept. The current research follows a multilevel approach to disentangle the individual and contextual correlates of conservative attitudes toward life and death. Thus, besides looking at the influence of individual choices related to religion and political orientation, this study also seeks to analyse the impact of the context, introducing in the model variables measuring economic performance, social and gender inequality, religious diversity and the prevalence of materialism and post-materialism values. Multilevel models using data from the 34 countries that participated in the last wave of the European Values Study (2017–2020), revealed an association between far-right orientation and conservative attitudes toward life and death, and that this relationship is moderated by materialism/post-materialism values, economic performance, and social inequality. Our findings reinforce the role of democracy as an environment where freedom of choice and thought are indisputable rights, cherished by most of the populations, regardless of their political position or their stance on moral issues.

1 The faces of conservatism

Conservatism, as an ideological belief system, reflects a set of principles that guide the lives of those who praise stability, control over life, adherence to pre-existing social norms, and endorsement of social and economic inequality (e.g., Tomkins, 1963; Wilson, 1973; Stone and Schaffner, 1988; Eckhardt, 1991; Sidanus and Pratto, 1996). Conservative people tend to conform to social order and socially accepted behaviors, having conformity as a restraining effect on actions, inclinations and impulses that might violate social expectations or norms. They are a guarantee that social life runs smoothly without disruptive events. As Schwartz (1992) wrote, following conformity means praising obedience, self-discipline, politeness and the veneration of parents and elders. Conservative people are also very proud of their roots and traditions, acting to preserve symbols and practices that work for group unity and ensure the survival and maintenance of the group's distinctive traits. Religious rites, beliefs and behavioral norms are the major forms assumed by tradition: they aim to instill respect, commitment and approval of the customs and ideas that are imposed by religion and culture (Schwartz, 1992). Within the same line of thought, Wilson (1973) defines conservatism as the “resistance to change and the tendency to prefer safe, traditional and conventional forms of institutions and behavior”. This definition entails a psychological profile that avoids uncertainty and promotes a political ideology that values the maintenance of the status quo. For that reason, conservatism acts on many different areas of life, orienting people that hold conservative views when they are faced with disturbing dilemmas: the moral principle of, for instance, “thou shalt not kill” vs. a war context where killing is acceptable.

Conservatism can then be understood as a defensive response to the fear of uncertainty and threat (e.g., Altemeyer, 1998; Duckitt et al., 2002; Jost et al., 2003) that can be satisfied by adopting a conservative ideology associated with resistance to change and endorsement of inequality. Attitudinal responses to the different sources of uncertainty include religious dogmatism, ethnocentrism, authoritarianism, punitive measures, and rigid morality (Wilson, 1973).

Conservatives have a higher tendency to engage in conventional moral reasoning, based on laws and duties, while liberals are more prone to engage in post-conventional moral reasoning, based on rights and universal moral principles (e.g., Emler et al., 1983; Feather, 1988). It is not our aim to discuss whether conservatives have a more complex and developed moral reasoning than liberals or not, but there is empirical evidence suggesting that, for liberals, morality is about issues of harm, rights and justice, whereas for conservatives, morality is also about group loyalty, respect for authority, and bodily and spiritual purity (e.g., Haidt and Graham, 2007). Both perspectives have established a strong relationship between political orientation and moral intuitions, with the choice of a conservative ideology being a way of preserving one's values, namely the conceptions of right and wrong.

Based on these perspectives, we will focus our analysis on the correlates of moral conservatism, as a composite measure of attitudes toward life and death: namely the justification of abortion, suicide, euthanasia, and in vitro fertilization, paying particular attention to the impact of the far-right ideology.

Attitudes toward life and death are particularly relevant as they reflect the individuals' positioning in an axis that opposes authoritarian to libertarian values. This dimension divides those favoring the values of conformity with conventional social norms, collective security (authoritarians), from those favoring personal freedoms, pluralism, and individualism (liberals) (Norris and Inglehart, 2019). Traditionalists supporting social conformity are likely to feel that people endorsing modern social mores, like the acceptance of multicultural lifestyles, tolerance of ethnic diversity or fluid gender identities are not simply mistaken; they are morally wrong (Norris and Inglehart, 2019). Accordingly, people holding traditional values take a pro-life stance on abortion, euthanasia, and suicide. Holding more liberal views is one of the results of the value shift initiated by the Silent Revolution that occurred during the second half of the twentieth century. This shift eroded materialist values, prioritizing economic and physical security, and brought a gradual rise of post-materialist values, accentuating the importance of individual free choice and self-expression (e.g.,. Inglehart, 1977).

Thus, the main objective of this research is to analyse whether the context, namely the prevalence of materialist or post- materialist values in a society, functions as a trigger or a buffer in the impact of far-right ideology on socially critical issues, such as conservative social mores.

1.1 The specific case of far-right conservatism

Europe is a home where liberal democracy is cherished. “It is a peace project, which emerged from the tragedy of war and was founded on the respect for human dignity, human rights, freedom, democracy, equality and the rule of law” (von der Leyen, in Reeskens, 2022). However, the last decade has been marked by a political change that constitutes a worrying threat to the most basic foundations of democracy: the spread of far-right ideology and the rise of radical right-wing populist political parties.

Far-right movements are letting everyone know about their existence, as they have become very visible and loud in European countries and are, possibly, behind the origin of the establishment of populist and authoritarian regimes in Western democracies (Norris and Inglehart, 2019). Parties like Brothers of Italy, Rassemblement Nationale in France, Alternative für Deustchland in Germany, Prawo I Sprawiedliwosc (Law and Justice) in Poland, Fidesz in Hungary, UKIP (the UK Independence Party) in the United Kingdom, Vox in Spain, or the Golden Dawn in Greece (banned in 2021 but alive among their supporters) are some examples of far-right parties that are gaining votes and recognition from the people (Halikiopoulou and Vlandas, 2019). In Portugal, a country without far-right representation since the Revolution of 1974, a new populist political party (Chega) has appeared and rapidly gained supporters among all social layers, currently being the 3rd political force, after the socialists and the social democrats.

Populist far-right parties are not a homogeneous group, but they share several core ideological positions, such as nativism, populism, and authoritarianism (Mudde, 2007): characteristics identified by Adorno et al. (1950) as defining traits of the authoritarian personality. Right-wing authoritarians believe strongly in the submission to established authorities and the social norms these authorities endorse (Altemeyer, 1998), with the infringement of authority being something that must be punished severely. For instance, right-wing authoritarians are more prone to see the benefits of having a strong leader and powerful army forces (e.g., Sprong et al., 2019). Previous studies have also shown that people holding authoritarian values are more likely to express conservative attitudes toward social issues (e.g., Adorno et al., 1950; Altemeyer, 1998; Inglehart and Baker, 2000; Norris and Inglehart, 2019; Nilsson and Jost, 2020). However, the issues previously investigated have been narrowing their focus to converging themes, such as abortion, same-sex marriage, LGBT rights, gender equality, and affirmative action (Norris and Inglehart, 2019). In a study based on data from the European Values Study (EVS) 2008–2010, Szalma and Djundeva (2019) found that people with higher levels of religiosity, lower acceptance for homosexuals' rights and lower acceptance of abortion were also less in favor of assisted reproductive technologies. Bulmer et al. (2017) demonstrated that in the US lower levels of conservatism were associated with supporting euthanasia. Based on the data of the General Social Surveys, Yen and Zampelli found a negative relationship between political conservatism and abortion support and that this relationship was stronger in comparison to religiosity (Yen and Zampelli, 2017). Norris and Inglehart (2019) found consistent correlates of voting support for populist parties, namely, support for authoritarian values and far-right ideological self-placement. In contrast, abortion rights, same-sex marriage, more fluid gender identities and support for progressive change on these issues increasingly comes from well-educated younger generations of post-materialists.

To the best of our knowledge, conservative attitudes toward life and death, as a key concept, and its relationship with political authoritarianism have never been addressed, which makes this article a ground-breaking contribution to the field. The current study thus aims to fill this gap in the literature, investigating how the adhesion to an extreme right-wing political orientation, conveyed, and reflected in populist radical right-wing parties, is related to people's views on moral issues related to life and death. Moreover, we will analyse in what measure extreme right-wing views on these matters differ from those of right, center, and left-wing supporters.

Following the findings from previous research, we hypothesize that people with far-right political orientations hold more conservative attitudes toward life and death issues than individuals placing themselves in the democratic right, center or left of the political spectrum (H1).

2 Cultural values and moral principles

Two main assumptions have guided research in the field of values: (1) values represent fundamental principles that guide people in their different life domains, leading to the study of individual differences; (2) the importance that a society in general attributes to values also reflects the fundamental principles that guide that society, leading to the study of shared values in different countries and cultures (Ramos et al., 2016). Accordingly, the role of values may be analyzed on two different (although not independent) levels. They represent individual motivations, serving as guiding principles for personal actions and choices (e.g., Schwartz, 1992). However, at a country level, values express shared conceptions of what is good and bad, what is seen as either desirable or unfavorable in the culture. Consequently, they serve as guiding principles for national priorities and public policies. Hofstede (1980) and Inglehart (1990, 1997) called this conception, cultural values.

Inglehart (1990, 1997) dedicated a substantial part of his work to the study of the changing process of values in advanced industrial societies, concluding that modern societies have experienced a shift from materialist values to post-materialist values. This typology organizes and creates a hierarchy for societal objectives. At the base of this model, value priorities are to be found centered on the satisfaction of basic needs, economic growth, and social cohesion. At the top, we find concerns regarding the intellect, aesthetics, quality of life and participation in decision-making processes, both in terms of work and the political system. Only when countries overcome economic lack do they stop giving priority to security, order and economic prosperity and start valuing the needs for self-fulfillment, political participation, and environmental concern. Therefore, and following Inglehart's model, giving priority to the first type of need corresponds to praising materialist values, whilst giving priority to the second is to extol those of post-materialism.

While people tend to hold more traditional and conservative values in the face of material insecurity, the past decades have witnessed rising economic and physical security leading to a gradual intergenerational shift in many countries placing higher emphasis on post-materialist values (Welzel and Inglehart, 2009). These processes, along with rising educational levels, have encouraged the spread of emancipative values giving priority to gender equality over patriarchy, tolerance over conformity, autonomy over authority and participation over security. Based on these considerations, we draw the following hypothesis:

H2: In countries with higher levels of economic performance, people endorse less conservative attitudes regarding life and death.

H3: In countries with lower levels of social inequality, people endorse less conservative attitudes regarding life and death.

H4: In countries with higher performance regarding gender equality, people endorse less conservative attitudes regarding life and death.

Economic development and educational expansion have given people the cognitive prerequisites necessary for a transition from the conventional to the post-conventional level of moral judgement (e.g., Kohlberg, 1976; Colby et al., 1987; Dülmer, 2001). While at the conventional level, traditional religious and social norms and rules are the main guides of moral judgements, at the post-conventional level, these norms and rules are questioned with respect to their genuine moral meaning, as this process enables individuals to distinguish between culture-specific conventions and universally valid moral rules and principles (e.g., Nunner-Winkler, 1998; Dülmer, 2014). According to Inglehart (1997), religion also fulfills a need for psychological security, as it transmits what rules and norms should be followed. There is empirical evidence, however, that the late stages of modernization are associated with declines in religious practice, affiliation, and belief (Voas and Doebler, 2014).

Previous research has given empirical evidence that supports the assumption that in countries where post-materialistic values are more salient, their populations are more open toward moral issues (e.g., Dülmer, 2014). For instance, based on the 5th wave of the World Values Survey (WVS), Rudnev and Savelkaeva (2018) analyzed data from 35 countries and concluded that the acceptance of euthanasia is an expression of autonomy values rather than just a function of a low religiosity, and that the impact of autonomy is stronger in countries with higher levels of post-materialism. Also based on WVS data, Stack and Kposowa (2016) concluded that cultural approval of suicide is related to a general cultural axis of nations endorsing post-materialist values. Following these findings, we expect to find people endorsing less conservative attitudes regarding life and death in countries with higher levels of religiosity (H5), and with a prevalence of post-materialist values (H6).

3 Data and methods

3.1 Participants

This paper is built on data from the 5th Wave of the EVS (2022), representing 34 countries and 56,491 respondents. Data was weighted by gweight, a weighting factor available in the EVS data set that has been computed using the marginal distribution of age, sex, educational attainment and region. A detailed description of the countries' sample characteristics can be found in Annex 1.

3.2 Conservative attitudes

In this study conservative attitudes are measured by an index indicating the resistance to accept four actions related to life and death. The EVS questionnaire included a set of situations and behaviors, inviting respondents to indicate the degree to which they found them justifiable or not (the scale ranged from 1-never justifiable to 10-always justifiable; scale values were recoded so that higher scores represented higher rejection).

From a set of 15 indicators, we specifically selected those related to life and death, namely abortion, suicide, euthanasia, and artificial/in vitro reproduction. Confirmatory factor analysis revealed excellent fit to the entire data set: χ2 (df = 1; N = 56,730) = 119.00, p < 0.001, CFI = 1.00; TLI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.048 (CI: 0.041; 0.056) with a factor loading between 0.63 and 0.80. The same was true for the configural equivalence assessment: χ2 (df = 34; N = 56,730) = 146.00, p < 0.001, CFI = 1.00; TLI = 0.98; RMSEA = 0.047 (CI: 0.039; 0.055). This suggests that the indicators loaded on the same latent factor in all countries (see detailed information in the online Supplementary material). In addition, internal consistency analysis revealed moderate to robust parameters (α = 0.75; ω = 0.79).

3.3 Conservative attitudes' correlates

3.3.1 Individual level

3.3.1.1 Political orientation

The main correlate of our model is political orientation. In the descriptive analysis, we used a recodification of the original 10-point scale variable in 3 categories: far-left (1 and 2), middle positions (3–8) and far-right (9 and 10). With this recodification, we intended to test the differences between far-left and far-right and see whether the far-right was a specific case. A different transformation was performed on the variable included in the multilevel models, since our purpose was confronting the far-right political orientation with the rest of the political spectrum. Thus, we performed a different transformation of the variable in two positions: far-right, corresponding to points 9 and 10 of the original scale (0.50) and all the other points of the scale (−0.50).

3.4 Control variables

3.4.1 Individual level

We introduced in the multilevel models the following set of individual-level control variables: sex, age, education level, and importance of religion in life.

3.4.2 Country level

At the country level, we considered the following contextual variables: for the economic dimension, GDPppp (UNDP); for the social dimension, GINI (UNDP), Gender Development Index (UNDP),1 Gender Inequality Index (UNDP),2 and Religious Diversity Index (PEW)3; and for the cultural dimension, adhesion to materialism/post-materialism values.

The EVS questionnaire included eight of the 12 indicators of Inglehart's original scale of materialism/post-materialism. Respondents were asked to answer the following set of questions:

“People sometimes talk about what the aims of this country should be for the next 10 years. On this card are listed some of the goals which different people would give top priority. Would you please say which one of these you yourself consider the most important? And which would be the next most important?”

(1) A high level of economic growth

(2) Making sure this country has strong defense forces

(3) Seeing that people have more say about how things are done at their work and in their communities

(4) Trying to make our cities and countryside more beautiful

If you had to choose, which one of the things on this card would you say is most important? And which would be the next most important?

(1) Maintaining order in the nation

(2) Giving people more say in important government decisions

(3) Fighting rising prices

(4) Protecting freedom of speech

The measure of materialism/post-materialism was operationalised as follows: firstly, we attributed a score to each item (2 if the item was first choice, 1 if it was second choice; 0 if it was not chosen). We then averaged the materialist items and aggregated them at country level in a materialism score. We did the same procedure with post-materialist items and, finally, the materialism score was subtracted from the post-materialism score (i.e., post-materialism minus materialism). Thus, for each respondent, we obtained a scale ranging from −1.5 to 1.5, where −1.5 stood for higher materialism and 1.5 for higher post-materialism. We decided to use values at the contextual level for two reasons: (1) Inglehart's indicators actually measure cultural rather than individual values, since respondents are asked about goals to be achieved by the society and not by the respondents themselves; (2) using the country-level measure of values is theoretically meaningful because individual and cultural values are two different things: while the first measure basic individual motivations (Schwartz, 1992), the second measure priorities that people believe are important as societal goals (Inglehart, 1977).

3.5 Data analysis strategy

We began with descriptive statistics on attitudes toward life and death by country and examined its relationship with various political positions (far-left vs. “in between” vs. far-right). Then, we tested the proposed hypotheses by performing a series of multilevel estimations using MPlus software (Muthén and Muthén, 2017). We focused on estimating the association between individual far-right (vs. other) positioning on attitudes toward life and death, while controlling for individual variables. We then estimated the role played by contextual indicators and finally included the interaction terms between far-right political positioning and the country-level indicators. Following the recommendations of Enders and Tofighi (2007), all correlate variables were centered on their grand mean. Parameter models were estimated using the maximum likelihood estimation with standard errors (MLR) method, and we specified either fixed or random intercept and slope terms (see Nezlek, 2001). In addition, we interpreted significant cross-level interaction coefficients by plotting those of far-right individuals (relative to other positioning) on attitudes toward life and death in countries with lower (relative to higher) scores on country-level indicators.

4 Results

4.1 Conservative attitudes and political orientation

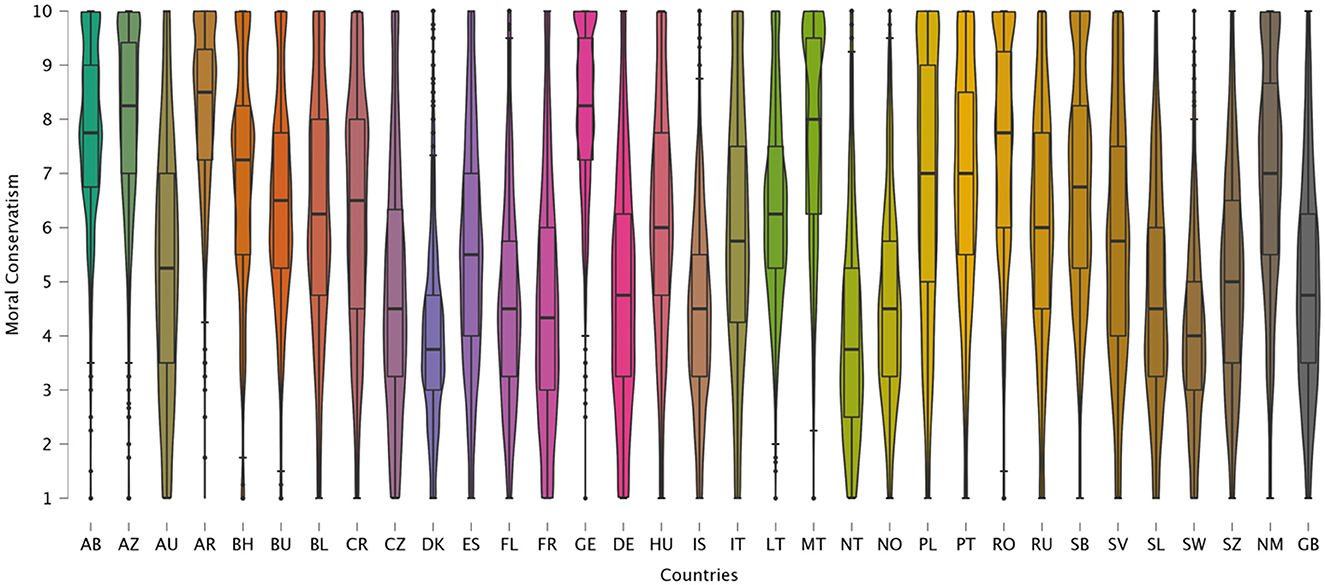

The first finding from our analysis is that European countries vary a lot in their adherence to conservative attitudes toward life and death (Figure 1). Nordic countries, along with the Netherlands and France, show the lowest levels of adhesion. In contrast, we find North Caucasus countries (Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan) having the highest adhesion scores, followed by Eastern European countries, such as Albania, Montenegro and Romania.

The endorsement of conservative attitudes toward life and death may have multiple explanatory factors depending on individual characteristics of the respondents and cultural environment factors. Since far-right political orientation is our main individual correlate, however, we first need to know if, from a global point of view, the adoption of conservative ideals regarding life and death issues is different in respondents that identify themselves with the far-right. In fact, according to our results, people endorsing far-right political orientations (N = 4,920; M = 6.67; SD = 2.45) are significantly different from those on the far-left (N = 4892; M = 5.64; SD = 2.63) and from the middle positions (N = 36,834; M = 5.57; SD = 2.32) regarding attitudes toward life and death [F (2,46643) = 476.2, p < 0.001, = 0.020]. Thus, in the next sections, following our hypotheses, we will focus on the role of individuals' far-right positioning (as opposed to other placements).

4.2 Individual and contextual correlates of conservative attitudes toward life and death

Based on the single intercept model (Table 1, null model), aiming to describe how much of the total variance of conservative attitudes is allocated to each level of analysis, we calculated the Intraclass Correlation corresponding to level 2 data structure (country). Results show that 28% of the variance can be assigned to the country level, suggesting the adequacy of analyzing data using multilevel regression to estimate the model parameters.

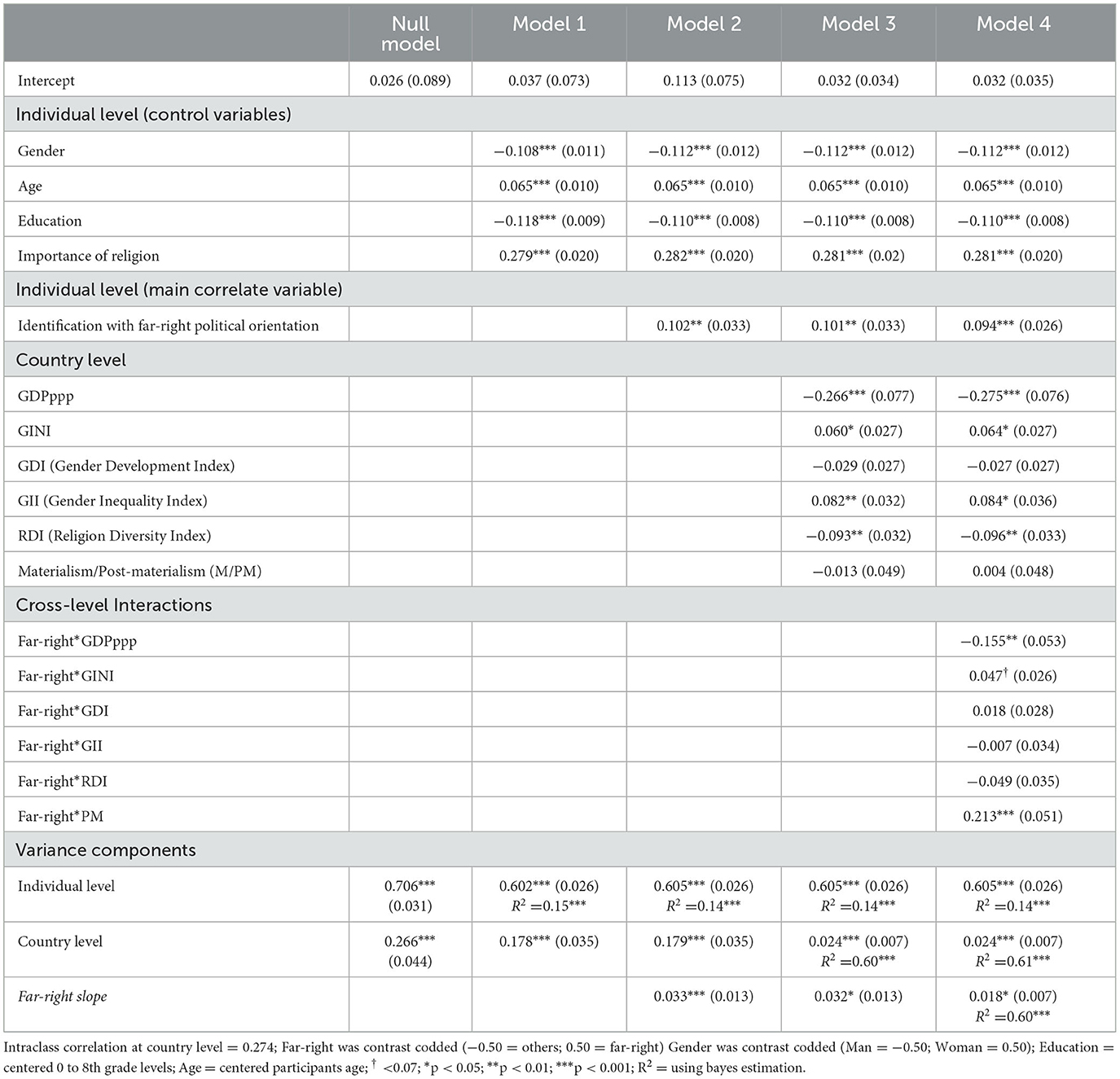

Table 1. Correlates of conservative attitudes toward life and death in 34 European countries (parameter estimates).

The role played by control variables (Table 1, model 1) follows the tendency that has been found in the literature. Men, older individuals, and those for whom religion is important show higher levels of endorsement of conservative attitudes. Higher levels of education, on the other hand, are associated with lower levels of endorsement of conservative attitudes. This pattern of findings holds equally through all the models estimated, avoiding spurious interpretations between variables for which we have specific hypotheses to test the endorsement of conservative attitudes toward life and death.

In model 2, we introduced the main individual correlate, far-right political positioning (vs. all other positioning). Confirming our hypothesis, results show that people endorsing far-right ideology tend to hold more conservative attitudes. Moreover, this is a robust finding, as it remains significant after controlling the variance accounted by the control variables. In this model, we added the estimation of random slopes for far-right political orientation. Results showed that the association between far-right and conservative attitudes varies between countries, suggesting that this relationship can be moderated by contextual variables.

In Model 3, we added the contextual variables to explore the relevance of the economic performance (GDPppp); social inequality (GINI); gender inequality (GII and GDI); religious diversity (RDI) and cultural values (materialism/post-materialism). Our findings confirmed most of our predictions. Economic performance was indeed an important factor, as the higher the GDPppp, the lower the endorsement of conservative attitudes toward life and death (H2). We also found higher levels of endorsement in countries with higher social inequality, as measured by the Gini index (H3), and in countries with lower levels of religious diversity assessed by the RDI index (H5). Regarding the specific case of women's rights, only the index measuring gender inequality showed a significant association, as the higher the GII, the higher the adhesion to conservative attitudes toward life and death (H4). With cultural values, our hypothesis was not confirmed, since the association between materialism\post-materialism values and endorsement of conservative attitudes was not significant (H6). This model accounts for 16% and 64% of explained variance at, respectively, individual and contextual levels.

Equally important are the findings of the cross-level interactions (model 4). Results show that the relationship between far-right orientation and the endorsement of conservative attitudes is moderated by three contextual variables: GDPppp, GINI and materialism/post-materialism.

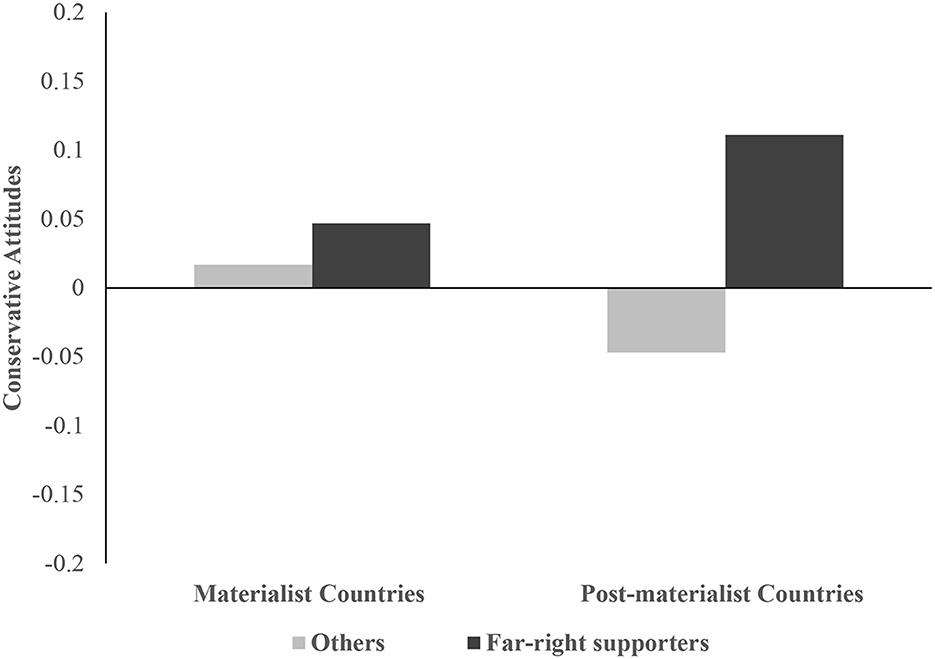

We have decomposed the interaction between far-right orientation and country level materialism/post-materialism (Figure 2). The results show that in more materialistic countries (i.e., countries with−1SD from the mean materialism/post-materialism) the relationship between the far-right and endorsement of conservative attitudes is not significant (b = 0.030, SE = 0.028, t = 1.078, p = 0.281). Furthermore, in more post-materialist countries (i.e. those with a +1SD from the materialism/post-materialism mean), we found a significant positive relationship between these variables, meaning that far-right individuals are more supportive of conservative attitudes toward life and death (b = 0.158, SE = 0.033, t = 4.817, p < 0.001). Figure 2 helps to better understand the meaning of these relationships: in post-materialist countries, people who were not on the far-right scored below the midpoint of the conservative attitudes index, meaning that they were opposed to it. On the other hand, those on the far-right were above this midpoint, clearly showing their tendency to hold conservative attitudes. Accordingly, this suggests that the positive relationship between far-right and more conservative attitudes in post-materialist countries is associated to the tendency of non-far-right individuals to be more open in their positions regarding life and death issues.

Figure 2. Estimated marginal mean scores of conservative attitudes toward life and death, as a correlate of far-right political orientation at the individual level and materialism/post-materialism at the country level.

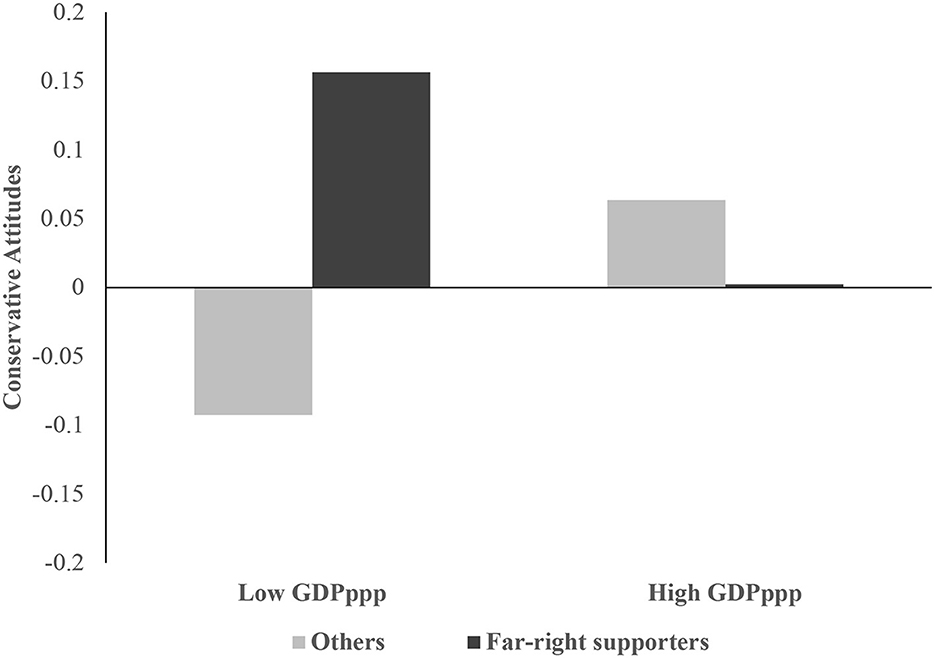

Decomposing the interaction between far-right orientation and country GDPppp (Figure 3), we found that in countries with lower GDPppp (i.e., countries with−1SD), the relationship between the far-right and endorsement of conservative attitudes was significantly positive (b = 0.249, SE = 0.062, t = 4.020, p < 0.001), suggesting that far-right individuals are more supportive of conservative attitudes than individuals that do not identify with the far-right. However, in countries with higher GDPppp, the relationship between far-right orientation and endorsement of conservative attitudes was not significant (b = −0.061, SE = 0.057, t = −1.083, p = 0.279).

Figure 3. Estimated marginal mean scores of conservative attitudes toward life and death, as a correlate of far-right political orientation at the individual level and GDPppp scores at the country level.

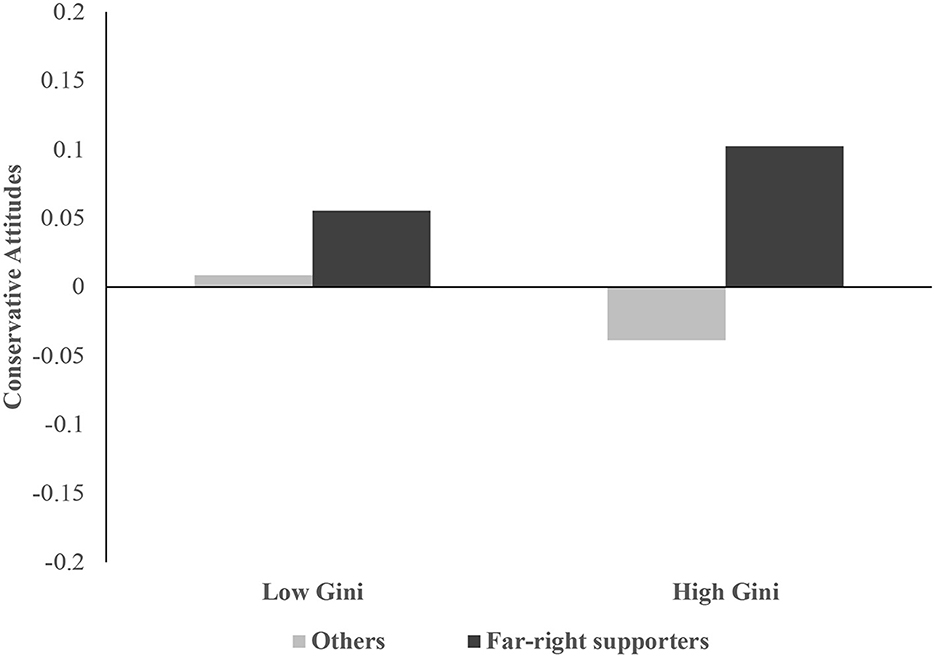

The pattern of results of the interaction between far-right orientation and the country's GINI (Figure 4) shows that the association between the far-right and endorsement of conservative attitudes was not significant in countries with a lower Gini (b = 0.047, SE = 0.040, t = 1.151, p = 0.250), but significant in countries with a higher Gini (b = 0.141, SE = 0.033, t = 4.309, p < 0.001). This association suggests that in countries with higher levels of social inequality, far-right individuals are more supportive of conservative attitudes toward life and death than people who place themselves in other political positions.

Figure 4. Estimated marginal mean scores of conservative attitudes toward life and death, as a correlate of far-right political orientation at the individual level, and GINI scores at the country level.

5 Discussion

We analyzed the relationship between identification with far-right political orientation and endorsement of conservative attitudes toward life and death issues (abortion, suicide, euthanasia and in vitro fertilization). In selecting indicators of conservative attitudes, we drew on the established literature to operationalize this construct. Importantly, our results provide sufficient empirical support for the factorial validity and reliability of the indicators used. Moreover, the correlation with respondents' political positioning on the left-right scale strengthens the theoretical foundation and criterion-based validity of these measures.

The belief that the behaviors selected are justified reflects one of the crucial components of post-materialist values as defined by Inglehart (1990, 1997). Moreover, and as hypothesized, we found that adhesion to conservative attitudes in Europe varied a lot, the lowest being in Nordic countries along with the Netherlands and France (countries that score high in post-materialist values) and the highest in the Republics of North Caucasus and Eastern European countries (countries that score low in post-materialist values).

As we referred to above, moral rules have a variety of functions, relating to both the psychological and social organizing principles of life (Inglehart, 1997). In traditional societies, moral rules contribute to individuals' reassurance that things are under control; and that social hierarchies are just and legitimate because they represent the distinction between right and wrong, which is universal, reflecting absolute truths with absolute validity, revealed by the word of a supreme supranatural power (Inglehart and Baker, 2000). At the societal level, absolute rules are crucial for a society's viability. The rule “Thou shall not kill” serves the societal function of restricting violence to narrow, predictable channels and prevents a society from collapsing. In the same way, condemning divorce, abortion and homosexuality serves the purpose of keeping the reproductive function within the family (Dülmer, 2014).

According to the theory, it is expected that in more developed contemporary societies, the process of socialization in an environment with high degrees of physical and economic security, along with the expansion of education and the consequent ability of questioning the status quo, contributes to the reduction of the psychological need for absolute rules (Inglehart, 1997). In such societies, individuals would have the cognitive skills to take a country-specific perspective, and to apply context-sensitive moral rules evaluating the potential consequences of rule obedience when making judgments about right and wrong (Dülmer, 2014). Besides this, in such societies, the need for economic growth and security gives place to needs for self-expression, autonomy and quality of life leading, among other values, to higher levels of support for minority rights and individual choice. But, in times of crisis, value change may point to conservatism and traditionalism (Welzel and Inglehart, 2009) and, consequently, to the search for security and stability. This is precisely the terrain where the far-right ideology searches for supporters: in moments of crisis, whether economic (e.g., increase of unemployment rates, inflation) or social (e.g., increase of immigration fluxes, exposure of corruption cases within the political sphere). While the functioning of democratic institutions is questioned, traditional and conservative values are extolled.

Results confirmed our prediction that people with a political orientation toward the far-right highly endorsed conservative attitudes. This initial hypothesis plays a crucial role in understanding the phenomenon under study. It draws on a wealth of research that emphasizes the crucial influence of individuals' political positioning on conservative attitudes and behaviors. This wealth of prior evidence, which forms the basis of our study (H1), serves as a springboard for our innovative propositions. Specifically, we propose that this association is not universal but moderated by prevailing societal values at the country level. This nuanced proposition both qualifies and accentuates H1, making it more significant in the broader context of our study.

We also confirmed that in poorer countries (lower GDP), in countries with higher levels of social inequality (higher GINI), in countries where women are still facing high levels of discrimination (higher GII), and in countries with lower levels of religious diversity (low RDI) people tend to hold more conservative attitudes. Nonetheless, the association with country-level materialist/post-materialist orientation was not significant.

Importantly, concerning the interactions between far-right positioning and post-materialist values, GDPpp and Gini were critical to understanding the contextual buffers and triggers of political positioning on adhesion to conservative attitudes.

Regarding the moderating effect of values, it is interesting to observe that the association between right-wing extremism and more closed attitudes toward life and death occurred mainly in countries with higher scores on post-materialism, while this association was not significant in more materialist countries. Two factors may contribute to this finding: (1) in countries scoring higher in materialist values, the endorsement of conservative attitudes was particularly high, as if “the glass is already more than half full”; (2) in these same countries, political ideology did not influence the endorsement of conservative attitudes, i.e., apparently there was not a clearly defined conflict of values. Accordingly, it is possible that the discourse of the far-right occupies a space that complements the one already fostered by the cultural environment where people live, which we identified as materialist.

However, in countries scoring higher on post-materialism, the results were somewhat different: here we found a clear expression of a value-based conflict. People that did not identify with the far-right took a position that was clearly against conservative attitudes toward life and death issues, as if they were engaging in a downward movement to express their rejection of the conservative agenda. Those on the far-right, on the other hand, were clearly in favor of such an agenda, as if they were reaffirming their conservative beliefs through an upward movement. This downward vs. upward countermovement seems to translate into a stronger statistical effect the more post-materialist a country is.

It is worth noting that, to our knowledge, Inglehart's theory did not anticipate a moderating role of materialism-postmaterialism values on far-right association with conservative attitudes. Inglehart's theory focused primarily on the broader relationship between modernization/postmodernization processes and political attitudes, with this materialism-postmaterialism value dimension serving as a proxy for these processes.

Our innovative research question, however, does not simply aim to validate Inglehart's theories in the contemporary context, although we do use Inglehart's instrument, which is justified by his theoretical rationale. Instead, the introduction of the cross-level moderation hypothesis and the robust empirical evidence derived from comprehensive and representative samples not only makes an important contribution to the discipline, but also opens new avenues for research in at least three theoretical areas. These include: (a) exploring the previously unexamined moderating role of societal-level factors around far-right political positioning; (b) understanding the contextual nature of individuals' conservative attitudes in the context of conservative ideologies; and, illuminating the role of materialism-postmaterialism values in understanding the relatively understudied intersection of individual and societal level variables in Inglehart's theory-based research in contemporary society.

We had previously found a negative association between GDPppp and endorsement of conservative attitudes, meaning that in richer countries people tended to be less conservative. This can be related to the cultural environment that is provided to the citizens in those countries, such as higher levels of information and education, and where death and life matters are on the social and political agenda, allowing each one to judge and decide about such controversial subjects. What the interaction reveals is that in these same countries the opinions about life and death issues were not associated with identifying with far-right ideology. In fact, this only happened in countries scoring lower on GDPppp, where the endorsement of conservative attitudes was stronger when identification with the far-right was also present. The same pattern was found regarding social inequality: we only found a significant, and positive, effect of the far-right on the endorsement of conservative attitudes in more unequal societies.

If we read this pattern of findings in the light of the Democracy Index 2020, developed by The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited (2021)4, we can verify that countries scoring higher on conservative attitudes toward life and death are among the ones scoring lower on Democracy Index and vice-versa. These observations suggest the importance that a democratic social and institutional context has in shaping social attitudes, namely those related to life and death issues. They indicate a relationship between values and democracy; but also an association between democracy and less conventional forms of moral judgement. Our findings reinforced the role of democracy as an environment where freedom of choice and thought were indisputable rights, cherished by most of the populations, regardless of their political position or their stance on moral issues.

Our conclusions can also be placed in a broader discourse. The increase of popularity of far-right parties and far-right political orientation can lead to a shift to more conservative values and a decrease in the acceptance of diversity in all its forms, which contradicts the main principles of the European community and, particularly, the European values. Moreover, 70 years after the publication of The Authoritarian Personality, many of Adornos' insights remain valid, namely the affinity between right-wing conservatism and authoritarianism, a relationship that we know is not invariant, depending on the context and specific facets of authoritarianism and ideology (Nilsson and Jost, 2020).

5.1 Limitations

Given that our dataset is based on cross-sectional research, it is important to note that we cannot establish causal relationships or determine the direction of influence between variables. Endogeneity remains a potential concern in cross-sectional studies, and no data analysis method can fully address this issue. It is possible that variables that could be associated to conservative attitudes and to political orientation have not been accounted for in the EVS questionnaire. While randomized controlled experimental designs would be ideal for addressing this concern, we opted for multilevel modeling, as it is a robust methodological approach for analyzing hierarchical data structures, helping to partially mitigate the issue.

In our study, we took several measures to address potential endogeneity issues. Firstly, we employed rigorous variable selection based on theoretical considerations. Additionally, we conducted extensive robustness checks and reliability analyses to ensure the stability of our results. Moreover, we incorporated in the multilevel models control variables, such as socio-economic background and other individual level variables, which contributed to minimize the blurring between the conservative attitudes toward life and death and adhesion to the far-right allowing us to address some of the challenges associated with drawing definitive conclusions.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://europeanvaluesstudy.eu/methodology-data-documentation/survey-2017/full-release-evs2017/.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of Institute of Social Sciences, University of Lisbon. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

AR, CP, NS, and MV contributed equally to the theoretical framework and the discussion of results. AR, CP, and NS contributed equally to the data analysis methodology. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

AR and CP were supported by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia IP, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian and Fundação La Caixa. NS was supported by the Higher School of Economics Basic Research Program.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2023.1159916/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^GDI measures gender inequality in achievement in three basic dimensions of human development: health, measured by life expectancy at birth; education, measured by the expected years of schooling for children and years of schooling for adults aged 25 years and older; and command over economic resources, measured by estimated earned income (United Nations Development Programme Annual Report, 2021). More information on GDI can be found in www.hdr.undp.org/gender-development-index#/indicies/GDI.

2. ^GII is a composite metric of gender inequality using three dimensions: reproductive health, empowerment and the labor market (United Nations Development Programme Annual Report, 2021). To learn more about this index, visit www.hdr.undp.org/data-center/thematic-composite-indices/gender-inequality-index#/indicies/GII.

3. ^RDI measures the share of eight major world religions (Buddhism, Christianity, folk or traditional religions, Hinduism, Islam, Judaism, other religions considered as a group, and the religiously unaffiliated) (Pew Research Center, 2014). To know more about the methodology behind the construction of this index, go to www.pewresearch.org/religion/2014/04/04/methodology-2/.

4. ^The Economist Intelligence Unit's Index, in addition to expert's assessments, uses indicators from public-opinion surveys, mainly the World Values Survey. The indicators predominate heavily in the political participation and political culture categories, with a few also used in the civil liberties and functioning of government categories.

References

Adorno, T. W., Frenkel-Brunswik, E., Levinson, D. J., and Sanford, R. N. (1950). The Authoritarian Personality. Virginia: Harpers.

Altemeyer, B. (1998). “The other “authoritarian personality”, in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, eds. M. P. Zanna. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, 47–92. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60382-2

Bulmer, M., Boehnke, J. R., and Lewis, G. J. (2017). Predicting moral sentiment towards physician-assisted suicide: the role of religion, conservatism, authoritarianism, and Big Five personality. Personal. Individ. Differ. 105, 244–251. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.09.034

Colby, A., Kohlberg, L., Speicher, B., Hewer, A., Candee, D., Gibbs, J., and Power, C. (1987). The Measurement of Moral Judgement: Volume 2, Standard Issue Scoring Manual. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Duckitt, J., Wagner, C., Du Plessis, I., and Birum, I. (2002). The psychological bases of ideology and prejudice: testing a dual process model. J. Personal. Social Psychol. 83, 75. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.83.1.75

Dülmer, H. (2001). “Education and the influence of arguments on moral judgment: an empirical analysis of kohlberg's theory of moral development,” in Kölner Zeitschrift Für Soziologie Und Sozialpsychologie (Berlin: Springer Nature), 53, 1–27.

Dülmer, H. (2014). “Modernization, Culture and Morality in Europe: Universalism, Contextualism or Relativism,” in Value Contrasts and Consensus in Present-Day Europe. Painting Europe's Moral Landscapes, eds. W. Arts and L. Halman. Leiden: Brill

Emler, N., Renwick, S., and Malone, B. (1983). The relationship between moral reasoning and political orientation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 45, 1073. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.45.5.1073

Enders, C. K., and Tofighi, D. (2007). Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: a new look at an old issue. Psychol. Methods 12, 121–138. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.2.121

EVS (2022). European Values Study 2017: Integrated Dataset (EVS2017). GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA7500 Data file Version 5.0.0. doi: 10.4232/1.13897

Feather, N. T. (1988). Moral judgment and human values. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 27, 239–246. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1988.tb00825.x

Haidt, J., and Graham, J. (2007). When morality opposes justice: conservatives have moral intuitions that liberals may not recognize. Soc. Just. Res. 20, 98–116. doi: 10.1007/s11211-007-0034-z

Halikiopoulou, D., and Vlandas, T. (2019). What is new and what is nationalist about Europe's new nationalism? Explaining the rise of the far-right in Europe. Nations and Nationalism 25:409–434. doi: 10.1111/nana.12515

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture's Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Inglehart, R. (1977). The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles Among Western Publics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Inglehart R. (1990) “Political value orientations” in Continuities in Political Action: A Longitudinal Study of Political Orientations in Three Western Democracies, eds M. K. Jennings and J. W. van Deth (Berlin; Boston, MA: De Gruyter), 67–102. doi: 10.1515/9783110882193.

Inglehart, R. (1997). Modernization, postmodernization and changing perceptions of risk. Int. Rev. Sociol. 7, 449–459. doi: 10.1080/03906701.1997.9971250

Inglehart, R., and Baker, W. (2000). Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. Am. Sociol. Rev. 65, 19–51. doi: 10.1177/000312240006500103

Jost, J. T., Glaser, J., Kruglanski, A. W., and Sulloway, F. J. (2003). Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychol. Bullet. 129, 339–375. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.339

Kohlberg, L. (1976). “Moral Stages and Moralization: The Cognitive-Development Approach,” in Moral Development and Behavior: Theory and Research and Social Issues, eds. T. Lickona. New York, NY: Holt, Rienhart, and Winston, 31–53.

Muthén, L. K., and Muthén, B. O. (2017). Mplus, Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables: User's Guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén and Muthén.

Nezlek, J. B. (2001). Multilevel random coefficient analyses of event- and interval-contingent data in social and personality psychology research. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bullet. 27, 771–785. doi: 10.1177/0146167201277001

Nilsson, A., and Jost, J. T. (2020). The authoritarian-conservatism nexus. Curr. Opini. Behav. Sci. 34, 148–154 doi: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2020.03.003

Norris, P., and Inglehart, R. (2019). Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nunner-Winkler, G. (1998). The development of moral understanding and moral motivation. Int. J. Educ. Res. 27, 587–603. doi: 10.1016/S0883-0355(97)00056-6

Pew Research Center (2014). Global Religious Diversity: Half of the Most Religiously Diverse Countries are in Asia-Pacific Region.

Ramos, A., Pereira, C. R., and Vala, J. (2016). Economic crisis, human values and attitudes towards immigrants. Values, Econ. Crisis Democ. London: Routledge, 130–163.

Rudnev, M., and Savelkaeva, A. (2018). Public support for the right to euthanasia: impact of traditional religiosity and autonomy values across 37 nations. Int. J. Comp. Sociol. 59, 301–318. doi: 10.1177/0020715218787582

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). “Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, eds. M. P. Zanna. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, 1–65.

Sidanus, J., and Pratto, F. (1996). Racism, conservatism, affirmative action, and intelectual sophistication: a matter of principled conservatism or group dominance? J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 70, 476–490. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.70.3.476

Sprong, S., Jetten, J., Wang, Z., Peters, K., Mols, F., Verkuyten, M., et al. (2019). “our country needs a strong leader right now”: economic inequality enhances the wish for a strong leader. Psychol. Sci. 30, 1625–1637. doi: 10.1177/0956797619875472

Stack, S., and Kposowa, A. J. (2016). Sociological perspectives on suicide. Int. Handbook Suicide Prev. 241–257. doi: 10.1002/9781118903223.ch14

Stone, W. F., and Schaffner, P. E. (1988). This Psychology of Politics. New York: Sringer-Verlag. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4612-3830-0

Szalma, I., and Djundeva, M. (2019). What shapes public attitudes towards assisted reproduction technologies in Europe? Demográfia 62, 45–75. doi: 10.21543/DEE.2019

The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited (2021). “Democracy index,” in Sickness and in Health? (London).

Tomkins, S. S. (1963). “Left and right: a basic dimension of ideology and personality,” in The Study of Lives, eds. R.W. White. Chicago: Atherton.

United Nations Development Programme Annual Report (2021). Available online at: https://www.undp.org/publications/undp-annual-report-2021

Voas, D., and Doebler, S. (2014). “Secularization in Europe: an analysis of intergenerational religious change,” in Value Contrasts and Consensus in Present-Day Europe. Painting Europe's Moral Landscapes, eds. W. Arts and L. Halman. Leiden: Brill.

Welzel, C., and Inglehart, R. (2009). Political Culture, Value Change, and Mass Beliefs. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Wilson, G. D. (1973). “A dynamic theory of conservatism,” in The Psychology of Conservatism, eds. G. D. Wilson. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press.

Keywords: cross-cultural studies, conservative attitudes, far-right orientation, life and death ethics, multilevel analysis

Citation: Ramos A, Pereira CR, Soboleva N and Vaitonytė M (2024) The impact of far-right political orientation and cultural values on conservative attitudes toward life and death in Europe: a multilevel approach. Front. Polit. Sci. 5:1159916. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1159916

Received: 06 February 2023; Accepted: 13 December 2023;

Published: 08 January 2024.

Edited by:

Hermann Duelmer, University of Cologne, GermanyCopyright © 2024 Ramos, Pereira, Soboleva and Vaitonytė. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alice Ramos, YWxpY2UucmFtb3NAaWNzLnVsaXNib2EucHQ=; Cícero Roberto Pereira, Y2ljZXJvLnBlcmVpcmFAaWNzLnVsaXNib2EucHQ=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Alice Ramos

Alice Ramos Cícero Roberto Pereira

Cícero Roberto Pereira Natalia Soboleva

Natalia Soboleva Meda Vaitonytė3

Meda Vaitonytė3