- The Law School, Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan

This paper examines the ministerial portfolio allocation to European Radical Right Parties (RRPs) in coalition governments, focusing on both quantitative and qualitative aspects. Ministerial portfolio allocation, essential for policy implementation and government stability, typically follows the proportionality principle, aligning ministerial portfolios with seat share. Meanwhile, traditional mainstream parties often secure ministerial portfolios that match their electoral programs. This study investigates whether RRPs—long regarded as “pariah parties”, despite their increasing participation in coalition governments since the early twenty-first century, often entering as weak junior partners and maintaining a hostile stance toward liberal democracy—follow these allocation patterns. Our analysis shows that while RRPs exhibit a proportional seat-to-portfolio share relationship, their allocations are more strongly influenced by bargaining power. Moreover, RRPs often fail to obtain ministerial portfolios aligned with their electoral priorities. Thus, while RRPs appear normalized in terms of quantitative allocation, they continue to face significant qualitative challenges.

1 Introduction

The study of coalition governments is one of the most advanced and progressive areas in political science (Druckman and Roberts, 2008, p. 101). Research on coalition governments encompasses several important classic themes, including the composition, duration, fulfillment of electoral pledges, decision-making processes, and the allocation of ministerial portfolios. Among these topics, the ministerial portfolio allocation is the least studied (Müller and Strøm, 1999; Mershon, 2001a, p. 278; Ecker et al., 2015, p. 802). However, ministerial portfolio allocation is one of the most critical aspects of coalition bargaining and formation (Bäck et al., 2011, p. 441), representing the bottom line of the political process in parliamentary democracy (Laver and Schofield, 1990, p. 164; Laver and Shepsle, 1996).

This is because, on the one hand, ministerial portfolios are typically the pinnacle of a political career for politicians and one of the most crucial resources for parties to provide rents and patronage (Druckman and Warwick, 2005; Verzichelli, 2008, p. 237; Saijo, 2020, p. 4). On the other hand, ministers, as the most important policymakers in parliamentary democracy, are the most tangible manifestations of policy payoffs. Controlling relevant ministerial portfolios in the government is a crucial intervening link between party policy and government action, giving a party a significant advantage in implementing its preferred policies in the relevant sector and bargaining capital to trade with parties controlling other issue areas. This, in turn, affects the overall policy output of the government and ultimately has a profound impact on the stability of the government itself (Browne and Franklin, 1973; Bäck et al., 2011; Bäck and Carroll, 2020). Therefore, regardless of a party's strategic goals—whether office-seeking, policy-seeking, or vote-seeking—all parties should be highly concerned with both the quantitative (i.e., how many ministerial portfolios they can secure) and qualitative (i.e., what types of ministerial portfolios they can obtain) aspects of ministerial portfolio allocation (Budge and Keman, 1990, p. 89; Strøm and Müller, 1999; Verzichelli, 2008, p. 238; Bäck and Carroll, 2020, p. 314).

Many past studies have shown that traditional mainstream parties strictly adhere to the principle of proportionality in the quantitative allocation of ministerial portfolios. This means that the share of ministerial portfolios they receive closely corresponds to their share of seats in the coalition government, maintaining an almost one-to-one relationship. This proportionality is largely unaffected by factors such as each party's bargaining power or the varying importance or policy salience of different ministerial portfolios. Regarding the qualitative allocation of ministerial portfolios, traditional mainstream parties are also often seen as being able to secure the ministerial portfolios they desire.

Do the characteristics displayed by traditional mainstream parties in the quantitative and qualitative allocation of ministerial portfolios also apply to Radical Right Parties1 (RRPs), which are often defined by their core ideological features of nativism, authoritarianism, and populism (Mudde, 2007, 2019)?

While postwar RRPs differ in many respects from the fascist movements of the interwar era, continuities in historical context and ideology can no longer be overlooked—particularly in terms of socio-economic conditions marked by widening class inequality and rising economic distress, policy orientations toward protectionism and authoritarian, xenophobic agitation, and political emotions fueled by anti-establishment sentiment and demands for radical change. Accordingly, the current surge of RRPs has been described by scholars of fascism as a period of “post-fascism” (e.g., Traverso, 2017). RRPs have also traditionally been treated as “pariah parties”, excluded from coalition politics due to their perceived threat to parliamentary democracy (van Spanje and van der Brug, 2007; Bäck et al., 2024; Calvo et al., 2024). Consequently, they have long been subject to political (Downs, 2002) and societal cordons sanitaires (Art, 2011). Only in the twenty-first century did they begin to normalize and gradually gain mainstream acceptance, leading to a growing number of RRPs entering coalition governments (Mudde, 2019, p. 3). However, within such coalitions, RRPs are almost always weak junior partners (McDonnell and Newell, 2011, p. 448–449). Moreover, due to their hostility toward liberal democracy (Mudde, 2007, p. 155–157, 2019, p. 113–128), they are seen not only as undermining democratic

quality at the national level but also as posing significant risks to European and North Atlantic integration (Liang, 2007). These features raise reasonable doubts as to whether RRPs follow the same patterns as traditional mainstream parties in the quantitative and qualitative allocation of ministerial portfolios. Yet this important question has received surprisingly limited scholarly attention.

To address this issue, this paper aims to compare the characteristics and differences between RRPs and traditional mainstream parties in both the quantitative and qualitative allocation of ministerial portfolios. It does so by constructing a more comprehensive and transparent dataset, applying widely accepted and standardized methodological approaches, adopting a pan-European perspective while remaining attentive to the political, economic, and cultural differences between Eastern and Western Europe, and combining primarily quantitative analysis with qualitative insights. In doing so, the paper contributes to the broader literature on ministerial portfolio allocation, RRPs, and the interrelationships between them.

This study finds that, regardless of whether ministerial portfolio importance is considered, and across all of Europe, Western Europe, and Eastern Europe, similar to other traditional mainstream parties, the seat share of RRPs shows an imperfect but still strong proportional relationship with their ministerial portfolio shares. However, though seat share shows higher explanatory power, the power index/vote weight of RRPs demonstrates a better proportional relationship with their ministerial portfolio shares than does their seat share. Particularly when considering ministerial portfolio importance, there is an almost perfect proportional relationship between the power index/vote weight of RRPs and their ministerial portfolio shares in all of Europe, Western Europe, and Eastern Europe. This indicates that, unlike traditional mainstream parties, for RRPs, bargaining power has a stronger proportional relationship with the ministerial portfolio shares they receive in coalition governments compared to their seat share.

Meanwhile, the ministerial portfolio shares that RRPs receive in coalition governments are often less than their seat share. However, the proportional relationship between seat share and ministerial portfolio share for RRPs in Eastern Europe is stronger than that for RRPs in Western Europe, regardless of whether ministerial portfolio importance is considered. Lastly, unlike traditional mainstream parties, RRPs often do not secure the ministerial portfolios they desire when entering coalition governments. Nonetheless, Eastern European RRPs still find it somewhat easier to obtain specific ministerial portfolios they prioritize compared to their Western counterparts, whereas Western European RRPs rely more heavily on their “hard power” (i.e., seat share) to secure specific ministerial portfolios than their Eastern counterparts. All in all, while RRPs have largely achieved normalization/mainstreaming in the quantitative allocation of ministerial portfolios, they still have a considerable way to go in the qualitative allocation before fully reaching that status.

In the next section, we will first provide an overview of the quantitative and qualitative theory of ministerial portfolio allocation, summarizing their longstanding key conclusions and highlighting the importance of studying the ministerial portfolio allocation to RRPs. In Section 3, we will explore the potential characteristics of ministerial portfolio allocation to RRPs, present our hypotheses, and critically assess the conclusions of the limited existing research. In Section 4, after introducing the dependent, independent, and control variables, we test each hypothesis using ordinary least squares regression and conditional logit regression, followed by a concise comparative case study to provide a more robust empirical foundation for the analysis. Finally, Sections 5 and 6 will discuss the empirical analysis results, highlight the academic contributions and limitations of this paper, and conclude with suggestions for future research directions.

2 The quantitative and qualitative theory of ministerial portfolio allocation

Regarding the quantitative allocation of ministerial portfolios (i.e., how many ministerial portfolios each coalition party secures), Gamson (1961, p. 376, p. 379) proposed over 60 years ago: “Any participant will expect others to demand from a coalition a share of the payoff proportional to the amount of resources which they contribute to a coalition”, meaning parties' demands reflect the proportion of resources they control.

The primary resource for each party is its seat share. Browne and Franklin (1973, p. 457) argued, “The percentage share of ministries received by a party participating in a governing coalition and the percentage share of that party's coalition seats will be proportional on a one-to-one basis”, meaning “the percent ministries received by parties in governing coalitions is directly proportional to the percent seats they contribute to the coalition” (Browne and Franklin, 1973, p. 467). Their calculations confirm this, showing a correlation coefficient of 0.926 between seat share and ministerial portfolio share, and a simple regression analysis (ministerial portfolio share as dependent variable, seat share as independent variable) yielding a constant of −0.01 and regression coefficient of 1.07 (Browne and Franklin, 1973, p. 460). Hence, Browne and Franklin's (1973) one-to-one proportionality hypothesis is supported.2

Since ministerial portfolio allocation visibly reflects the outcome of bargaining processes (Schofield, 1976, p. 36; Falcó-Gimeno, 2011, p. 393), bargaining theory—which analyzes how coalition gains are distributed among parties with conflicting preferences (Lasswell, 1936)—is often viewed as challenging Gamson's proportionality principle. However, empirical studies comparing seat share with the “power index/vote weight”—a widely used proxy for bargaining power, measuring how often a party is pivotal in coalition orderings—that is, when it transforms a losing coalition into a winning one (Shapley and Shubik, 1954; Banzhaf, 1965)—consistently find that seat share provides stronger explanatory power for ministerial portfolio allocation, both substantively and statistically. Bargaining power only occasionally slightly distorts proportionality3 (Mershon, 2001a; Warwick and Druckman, 2006; Ennser-Jedenastik, 2013; Falcó-Gimeno and Indridason, 2013; Ceron, 2014; Cutler et al., 2014), and in fact, differences in bargaining power frequently reinforce proportionality (Martin and Vanberg, 2020).

Another challenge is posed by importance/salience theory. Coalition parties negotiate not only over the number of ministerial portfolios but also over specific ministries (Browne and Franklin, 1973, p. 458). This occurs because certain ministerial portfolios are inherently more critical (e.g., Prime Minister), or because particular ministries become especially significant in specific contexts (e.g., the Finance Ministry after a financial crisis) (de Mesquita, 1979; Druckman and Warwick, 2005). Thus, ministerial portfolio allocation among parties may vary according to the relative importance or salience of individual ministries or policy domains.

These assumptions appear reasonable, yet empirical studies find that the impact of these factors on the quantitative allocation of ministerial portfolios is minimal. Even when considering variations in the importance or policy salience of ministerial portfolios, their quantitative allocation still largely adheres to the proportionality principle (Browne and Franklin, 1973, p. 465; Warwick and Druckman, 2001; Indridason, 2015, p. 21; Martin, 2016, p. 26–27; Martin and Vanberg, 2020). Some scholars further argue that despite methodological variations, research approaches emphasizing qualitative dimensions consistently support Gamson's proportionality principle (Raabe and Linhart, 2013, p. 482).

Besides bargaining model theory and importance/salience theory, even when considering factors such as geographical context—Eastern or Western Europe (Druckman and Roberts, 2005)—time spent in opposition (Falcó-Gimeno, 2011), voter perceptions (Lin et al., 2017), or examining different actors such as intra-party factions (Mershon, 2001a,b; Ceron, 2014), junior ministers (Manow and Zorn, 2004), the European Commission (Franchino, 2009), regional party branches (Ennser-Jedenastik, 2013), or regional coalition governments (Raabe and Linhart, 2013), Gamson's proportionality principle maintains robust statistical significance.4 Therefore, there is no compelling methodological or empirical reason to question the validity of this proportionality principle (de Mesquita, 1979, p. 62–63).

This principle, applicable to all aspects of coalition payoffs (Browne and Frendreis, 1980, p. 753; Schofield and Laver, 1985, p. 158), is among the most reliable, widely recognized, and robust empirical regularities. It is described as the “Nash equilibrium” and “iron law” in parliamentary democracies (De Winter, 2001, p. 190; Verzichelli, 2008, p. 239; Bäck et al., 2009, p. 28), coalition studies since the 1970s (Carroll and Cox, 2007, p. 300), comparative politics (Lin et al., 2017, p. 915), political science (Budge and Keman, 1990, p. 105; Laver, 1998, p. 7), and even across social sciences broadly (Laver and Schofield, 1990, p. 171; Warwick and Druckman, 2001, p. 627, 2006, p. 635).

In addition to the quantitative theory, the qualitative theory (i.e., what types of ministerial portfolios coalition parties can obtain) is another critical area of research. Qualitative theory argues that coalition parties not only seek ministerial portfolios proportional to their seat share but also target specific ministerial portfolios that are significant, govern salient policy areas (as noted earlier), or align closely with their ideological and policy priorities. Securing these ministerial portfolios enables parties to implement preferred policies or fulfill campaign promises (Budge and Keman, 1990).

Although these factors may not substantially influence the proportionality principle in the quantitative allocation of ministerial portfolios, numerous studies have found that parties emphasizing specific ministerial portfolios in their electoral programs or belonging to party families traditionally associated with particular ministerial portfolios have a higher likelihood of obtaining those ministerial portfolios (Bäck et al., 2011; Raabe and Linhart, 2013; Ecker et al., 2015; Greene and Jensen, 2016; Saijo, 2020; Däubler et al., 2024).

For example, Socialist parties typically obtain ministerial portfolios such as Social Affairs, Health, and Labor; Conservative parties commonly secure Interior, Foreign Affairs, and Defense portfolios; Liberal parties frequently receive Finance, Economy, and Justice portfolios; and Agrarian and Green parties usually hold Agriculture and Environment portfolios, respectively5 (Browne and Feste, 1975; Bäck et al., 2011).

The characteristics of quantitative or qualitative ministerial portfolio allocation discussed above are, to our knowledge, almost non-existent when applied to RRPs, with very few exceptions (e.g., Bichay, 2021). However, this issue is very important for several reasons. First, RRPs have traditionally been regarded as “pariah parties”, viewed by traditional mainstream parties as posing serious threats to parliamentary democracy and therefore considered non-coalitionable (van Spanje and van der Brug, 2007; Bäck et al., 2024; Calvo et al., 2024). As a result, they have long faced cordons sanitaires in both political systems (Downs, 2002) and social life (Art, 2011). It was only after entering the twenty-first century that they began to normalize and gradually achieve mainstream status, leading to an increasing number of RRPs participating in coalition governments6 (Mudde, 2019, p. 3). These innovative governing formulae (Mair, 1997, p. 209) involving RRPs are widely regarded as a reluctant outcome of strategies—such as co-optation, collaboration (Downs, 2001), accommodation (Meguid, 2008), or adoption (Bale et al., 2010)—that traditional mainstream parties were compelled to pursue after becoming unable to bear the high costs of continually excluding RRPs from coalition governments (Backlund, 2023, p. 894). Therefore, there is good reason to believe that the quantitative and/or qualitative allocation of ministerial portfolios to RRPs may significantly deviate from previously established patterns.

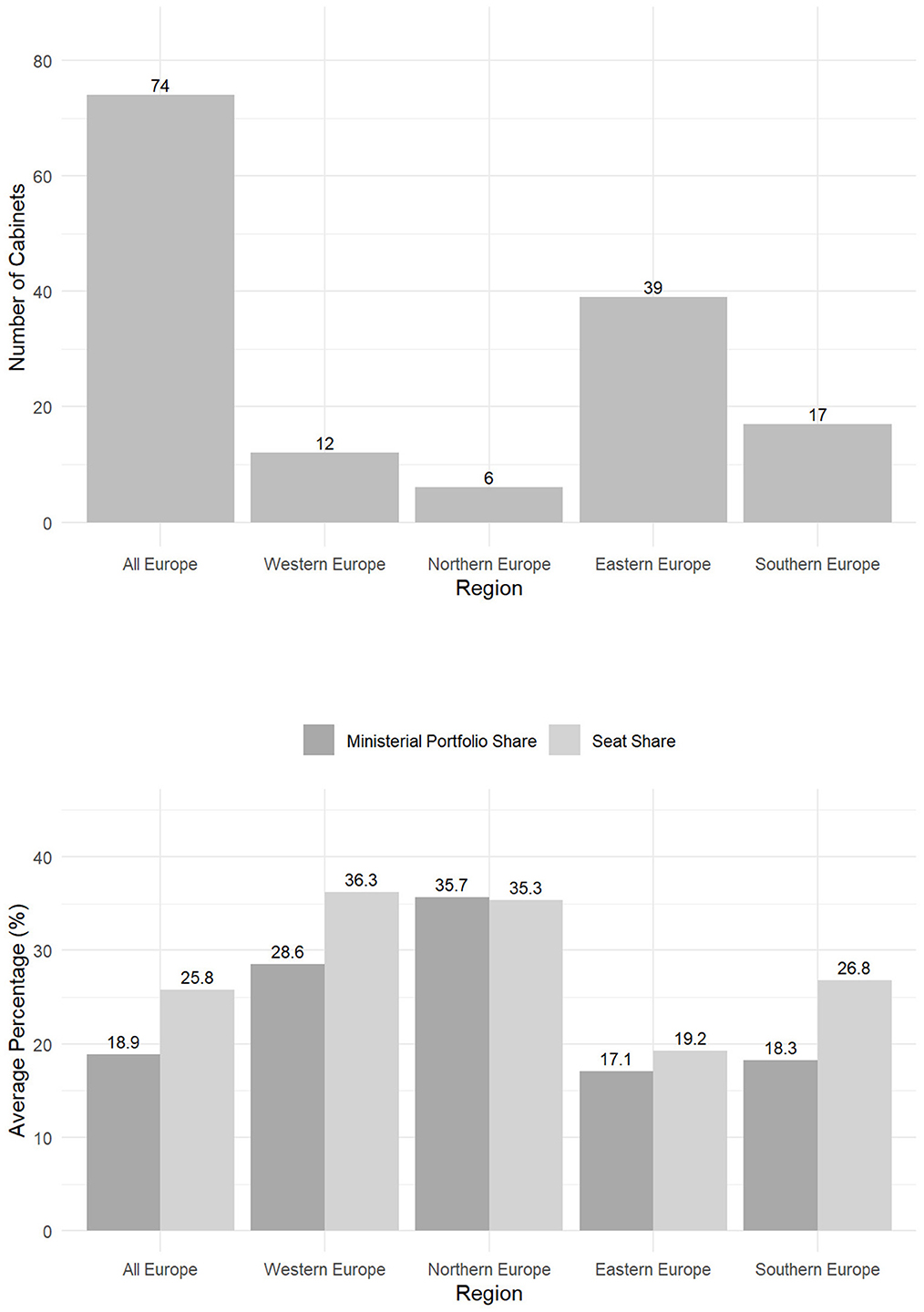

Second, there are marked regional differences in RRPs' government participation: over half of the cabinets involving RRPs are in Eastern Europe7 (about 52.7%), followed by Southern Europe (about 23%), Western Europe (about 16.2%), and the least in Northern Europe (about 8.1%)8 (see also Figure 1, Appendix 1). This suggests that political institutions or issue salience in different regions significantly impact RRPs' government participation. Third, RRPs in coalition governments are always typically weak junior partners (McDonnell and Newell, 2011, p. 448–449). During coalition formation or to maintain coalition stability, RRPs generally make significant concessions to senior partners (Heinisch, 2003). Furthermore, considering the characteristic of RRPs being adversaries of Liberal Democracy (Mudde, 2007, p. 155–157, 2019, p. 113–128), it is highly questionable whether other coalition partners would be willing to allocate important ministerial portfolios—such as Justice, Interior, Economic Affairs, and Immigration—to RRPs, even if these are highly desired by them.

Therefore, given the unique nature of RRPs, potential regional differences in institutional or issue salience, and their weaker position in coalition governments, the purpose of this paper is clear and straightforward: to examine whether the ministerial portfolio allocation to RRPs follows the same quantitative and qualitative patterns as those for traditional mainstream parties.

3 Radical right parties and the ministerial portfolio allocation

Many scholars have long argued that, due to the populist nature of RRPs, these parties—even when they enter coalition governments—struggle to implement their often unrealistic policy promises, which were primarily designed to attract votes. As a result, the policy influence of RRPs has generally been considered quite limited in the past (Canovan, 1999, p. 12; Mény and Surel, 2002, p. 18; Heinisch, 2003, p. 123–124; Taggart, 2004, p. 270; Hopkin and Ignazi, 2008, p. 61; McDonnell and Newell, 2011, p. 448–449; Mudde, 2013, p. 13–14).

However, in recent years, as RRPs have more frequently entered coalition governments, some of these parties are even considered to have gained sustainable governance capabilities (Albertazzi and McDonnell, 2015, p. 165–166). These parties are increasingly exerting significant policy influence in the areas they govern or are concerned about. For instance, scholars have pointed out that under coalition governments involving RRPs, criminal policies have become stricter (Bale, 2003); immigration, refugee, and integration policies have become more stringent (Schain, 2006; Bale et al., 2010; van Spanje, 2010; Akkerman, 2012; Akkerman and De Lange, 2012); language, education, and cultural policies have become more conservative, foreign policies have become more aggressive (Minkenberg, 2015); and welfare policies have become more restrictive (Schumacher and van Kersbergen, 2016; Falkenbach and Greer, 2018; Chueri, 2021).

The influence of RRPs on these policies can, of course, be indirect—such as through blackmailing or bargaining with other parties to achieve their policy goals—but it can also be direct, such as by controlling ministerial portfolios that oversee these policy areas. Especially as RRPs gain more experience and governance capabilities through repeated participation in coalition governments, they are increasingly likely to independently manage a ministerial portfolio and exert greater policy influence within its domain.

In this context, Nicolas Bichay made a valuable initial contribution to the study of RRPs' ministerial portfolio allocation. In a short article, he noted that RRPs consistently secure a ministerial portfolio share proportional to their seat share in the coalition government. Moreover, RRPs often succeed in obtaining the ministerial portfolios they prioritize (Bichay, 2021). Therefore, building on the conclusions of scholars presented in Section 2 and Bichay's preliminary observations on RRPs, it seems reasonable to assume that RRPs, like traditional mainstream parties, align with existing research findings on the quantitative and qualitative theories of ministerial portfolio allocation. More specifically9:

Quantitative Hypothesis 1: RRPs display strong proportionality between their seat share and ministerial portfolio share, even when ministerial portfolio importance is considered.

Quantitative Hypothesis 2: RRPs display stronger proportionality between their seat share and ministerial portfolio share than between their bargaining power and ministerial portfolio share, with seat share providing greater explanatory power.

Qualitative Hypothesis: The more RRPs emphasize specific policy areas, the greater the likelihood of securing ministerial portfolios overseeing those policy areas.

However, the hypotheses outlined above are not necessarily valid, as certain characteristics of RRPs cast doubt on them. For instance, under the governance of RRPs, minority rights, judicial and central bank independence, and freedoms of expression, press, association, and research have been undermined, leading to varying degrees of democratic backsliding in countries like Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia (Rosenbluth and Shapiro, 2018, p. 214–228; Batory and Svensson, 2019; Norris and Inglehart, 2019, p. 183–185). Furthermore, the rule of RRPs not only undermines the quality of democracy domestically but also negatively impacts international politics, as RRPs are often regarded as pursuing self-centered and sovereignty-focused foreign policies. This tendency results in actions that exclusively consider national interests and contradict the principles of liberal democracy on the international stage (Rathbun, 2004, p. 197–198, p. 213–214). Consequently, although RRPs do not share a uniform or monolithic set of foreign policy preferences, the main features of their foreign policy—characterized by nativism, anti-pluralism, anti-globalism, and anti-establishment sentiments (Destradi et al., 2021, p. 665, p. 671–676; Ostermann and Stahl, 2022, p. 5)—are widely seen as posing significant risks to European and North Atlantic integration (Liang, 2007).

Given the above, coalition partners are likely reluctant to allocate ministerial portfolios that oversee critical domestic and/or international policy areas to RRPs, which are considered adversaries of liberal democracy. This reluctance may impact the quantitative and/or qualitative allocation of ministerial portfolios to RRPs. In other words, although the normalization/mainstreaming of RRPs has become more frequent and significant in the twenty-first century, the allocation of ministerial portfolios to these parties may not follow the established patterns and principles of quantitative and/or qualitative allocation observed for other traditional mainstream parties.

Simultaneously, although Bichay's research fills an important gap in the study of ministerial portfolio allocation to RRPs, we cannot conclude that his findings are entirely accurate for several reasons: First, Bichay does not provide the source or detailed content of the dataset used, which raises concerns about data transparency and reliability. Second, in his analysis of the quantitative allocation of ministerial portfolios to RRPs, Bichay does not employ the most standard and widely accepted method in ministerial portfolio allocation research—ordinary least-squares linear regression (Indridason, 2015, p. 10, p. 15; Martin, 2016, p. 18). Third, his study focuses only on the seven most common ministerial portfolios10 shared among European governments, overlooking other significant ministerial portfolios such as Social Welfare, Health, Labor, Economic Affairs, and Culture, which are also often assigned to RRPs. Fourth, some of Bichay's specific conclusions regarding the qualitative allocation of ministerial portfolios to RRPs are inaccurate. For instance, he claims that RRPs are most likely to control the Defense and Justice portfolios and almost never manage the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. However, as demonstrated in Appendices 1, 2,11 these assertions do not hold. One of the main reasons for this inaccuracy appears to be Bichay's failure to account for the significant East–West divide in ministerial portfolio allocation to RRPs. The differences between Eastern and Western Europe in this regard can be attributed to a variety of factors—including, but not limited to, their distinct political, economic, and cultural contexts.

Lastly, Bichay did not take into account the potential influence of bargaining model theory and/or importance/salience theory. While previous research has shown that a party's seat share is crucial for dividing ministerial portfolios within coalition governments, this logic may not necessarily apply to RRPs. In particular, for RRPs operating in highly unfavorable contexts—such as in Nordic countries like Sweden or in Germany—seat share alone may carry less weight. Instead, the key factor may be whether these parties can convince traditional mainstream parties that their inclusion would enhance the coalition government's policy viability. In other words, bargaining power may replace seat share as the decisive factor (Martin and Vanberg, 2014)—especially when the importance or policy salience of specific ministerial portfolios is considered (Bassi, 2017)—not only in determining RRPs' ministerial portfolio allocation, but also in whether mainstream parties are willing to collaborate with them in the first place (Backlund, 2023). In summary, the hypothesis that RRPs have achieved normalization/mainstreaming in the quantitative and qualitative allocation of ministerial portfolios warrants further investigation.

While the critiques mentioned above may seem overly stringent for research that is less methodologically rigorous, Bichay (2021) still deserves high praise for addressing the research gap in the quantitative and qualitative allocation of ministerial portfolios to RRPs. Building on this perspective, this paper aims to advance the research in this area by creating a more comprehensive and transparent dataset, incorporating a broader range of variables, and applying more standardized research methods. In doing so, it seeks to make a further contribution to the study of ministerial portfolio allocation, RRPs, and the relationship between the two.

4 Empirical analysis

4.1 Data and methods

When testing Quantitative Hypotheses, we use ordinary least-squares linear regression, the most standard and widely accepted method. The independent variables are the seat share of RRPs in coalition governments (Siaroff, 2019; European Journal of Political Research Political Data Yearbook12) and their bargaining power, measured as the power index/vote weight (Shapley and Shubik, 1954). As previously noted, the power index/vote weight measures how often a given party transforms a losing coalition into a winning one—that is, how often its inclusion secures a parliamentary majority (i.e., typically 50% + 1 seat).

The formula is:

where n represents the number of parties, and n! is the total number of all possible orderings of those n parties.13

Additionally, as shown in Section 3, scholars have observed that the normalization/mainstreaming of RRPs have become increasingly frequent and significant over time. Therefore, to examine whether the analysis results on the ministerial portfolio allocation to RRPs change when time is considered as a factor, we will conduct additional regression analyses with time included as a control variable.

The dependent variable is the share of ministerial portfolios held by RRPs in coalition governments. The data source is the database of “WHO governs in Europe and beyond”.14 This database contains information about cabinet duration, the names of various ministerial portfolios and the individuals appointed to them, and the partisan affiliation of each minister at the time a particular cabinet is appointed in 48 European democratic states.15 We extracted data from 13 European countries, covering 22 RRPs and 74 coalition governments, spanning from October 1993 (Slovakia) to January 2024 (Switzerland) (see also Appendix 1).16

When considering the importance of ministerial portfolios, we need to weigh the different ministerial portfolios held by RRPs.17 We utilize the Portfolio Importance Scores for Western European countries (Druckman and Warwick, 2005) and Eastern European countries (Druckman and Roberts, 2008), derived from large-scale expert surveys.18

While most democracies include a set of core ministerial portfolios—such as head of government, Foreign Affairs, and Finance—the structure and composition of additional ministerial portfolios vary significantly across countries. Even within parliamentary cabinet systems, differences in coalition dynamics, administrative traditions, and institutional rules lead to considerable variation in how responsibilities are distributed, ministerial portfolios are reshaped and renamed, and ministries are reorganized. These variations introduce complexities that can obscure cross-national comparisons (see also text footnote 11). In such cases, like Druckman and Warwick (2005) and Druckman and Roberts (2008), the importance of a ministerial portfolio formed by combining two or more posts was calculated as the sum of the mean importance scores of the separate posts. When obtaining separate scores for different posts combined into a single ministerial portfolio, the total mean score was evenly divided among them (see also Bucur, 2016, p. 6) (for the Portfolio Importance Scores of ministerial portfolios across different cabinets in various countries, see Appendix 3).

In testing the Qualitative Hypothesis, we will employ a conditional logit regression analysis, following the approach of Bäck et al. (2011). The data are divided into 20 groups, each representing a different ministerial portfolio (details provided later).19 The dependent variable is a binary indicator of whether an RRP obtained a specific ministerial portfolio (1 = obtained, 0 = not obtained). The seat share of RRPs in the coalition government and their power index/vote weight are included as control variables. Meanwhile, similar to the analysis of the quantitative allocation of ministerial portfolios to RRPs, we will also conduct additional analyses to examine the potential impact of time on the qualitative aspect, including time as a control variable.

The independent variable is the policy salience assigned to each specific ministerial portfolio by RRPs. To measure this, the study also draws on the research by Bäck et al. (2011) and utilizes data from the Comparative Manifesto Project (Lehmann et al., 2024). This salience-based approach is well-suited for examining whether RRPs, like traditional mainstream parties, exhibit a pattern where greater emphasis on specific policy areas in their electoral programs corresponds to a higher likelihood of securing ministerial portfolios governing those areas.

As mentioned earlier, ministerial portfolios often have different names in different countries, and the policy jurisdictions of ministerial portfolios may vary substantially across countries. Therefore, when examining the qualitative allocation of ministerial portfolios, Bäck et al. (2011, p. 453) suggested a “maximalist approach”, which involves using a large number of categories in different combinations, allowing the repetition of categories for several ministerial portfolios. This approach maximizes the information available in the CMP dataset and provides the widest possible picture of the policy jurisdiction of ministerial portfolios (see also Däubler et al., 2024).

Bäck et al. (2011) identified 13 general categories of the most important ministerial portfolios in Western European countries.20 However, this paper takes a pan-European perspective and considers all the ministerial portfolios that RRPs have held to date (see also Appendix 1). Therefore, we have made some adjustments to the 13 general categories, resulting in 20 general categories (For details on the specific assignment of CMP categories to ministerial portfolios, see Appendix 4):

(1) Foreign Affairs

(2) Interior

(3) Justice

(4) Finance

(5) Economic Affairs

(6) Defense

(7) Health, Labor, Social affairs, Social Security, Welfare

(8) Education

(9) Agriculture, Fisheries, Food, Forestry

(10) Infrastructure

(11) Natural Resources, Environment

(12) Family, Generations, Birth, Equal Opportunity

(13) Integration, Immigration

(14) Public Administration

(15) Culture, Public Services, Sports, Tourism

(16) Transport, Innovation, Technology, Communication

(17) Development Cooperation, Foreign Trade

(18) Posts and Telecommunications

(19) Petroleum, Energy

(20) Regional Affairs and Autonomies

4.2 Analysis outcomes of quantitative hypotheses

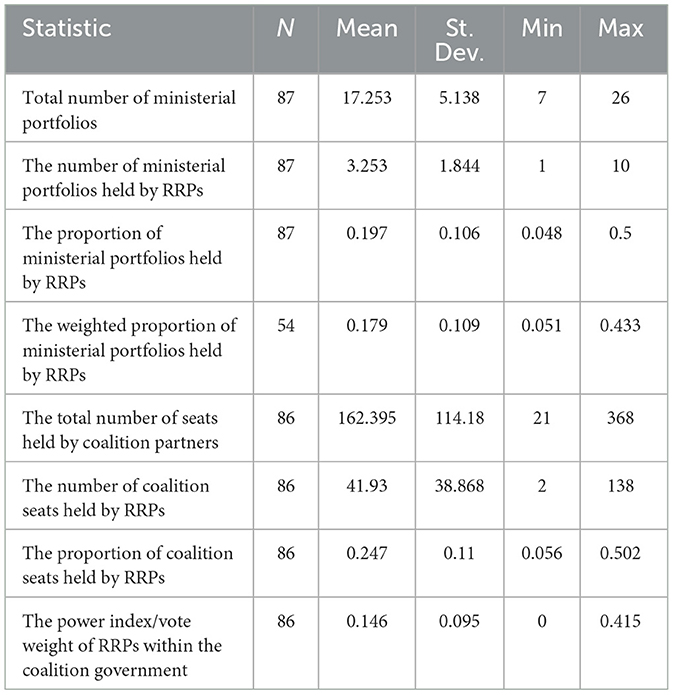

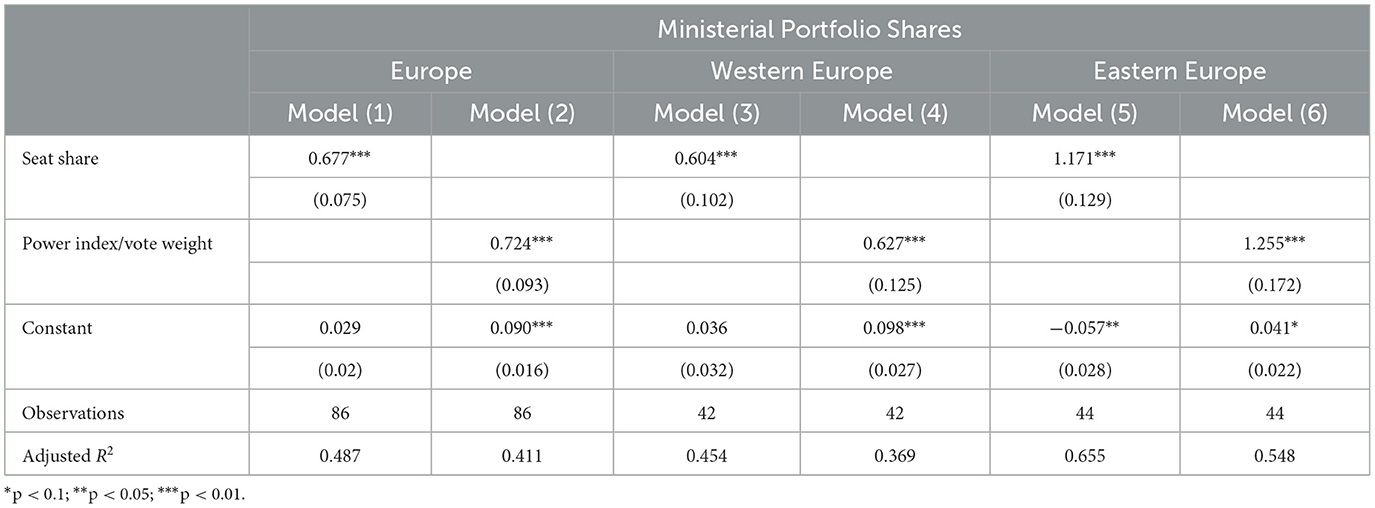

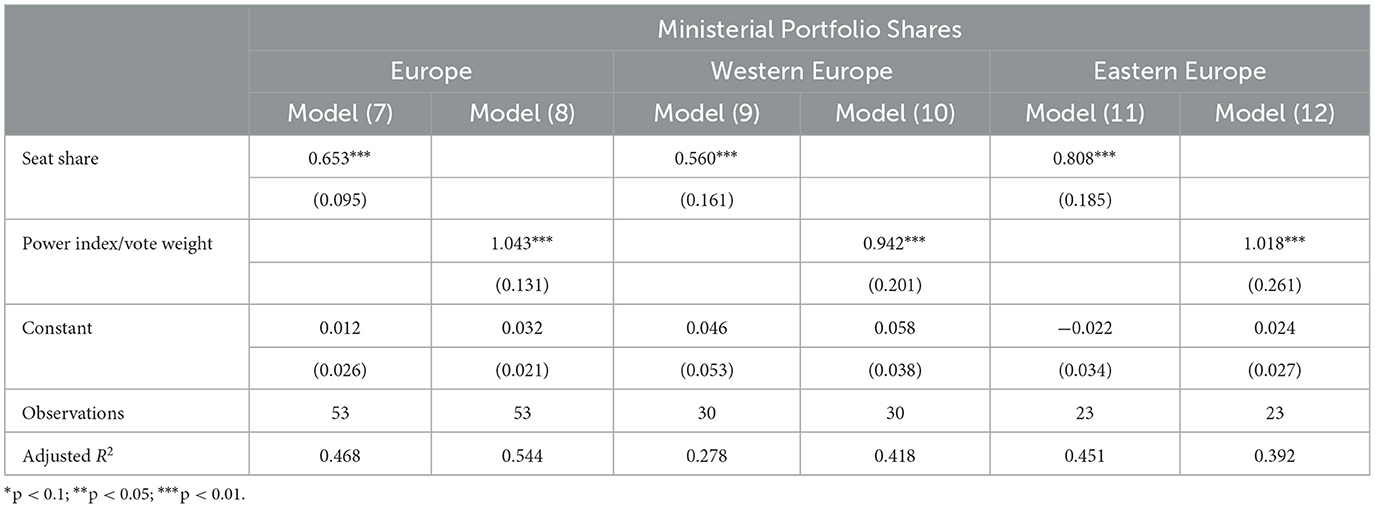

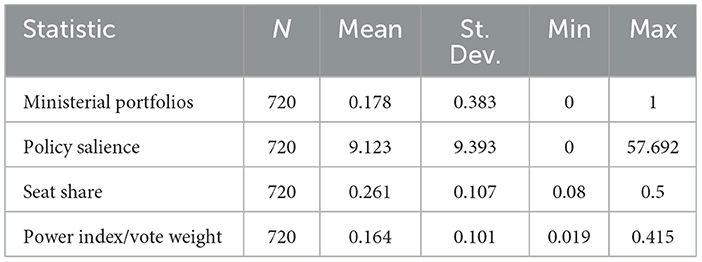

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for the ordinary least-squares linear regression, while Tables 2 and 3 present the results of the ordinary least-squares linear regression without and with consideration of ministerial portfolio importance, respectively. The results from models (1), (3), and (5) support the first part of Quantitative Hypothesis 1, confirming the strong proportionality between RRPs' seat share and ministerial portfolio share. The seat share coefficients are all highly significant at the 1% level and generally within the expected proportional range, though varying in their proximity to 1 (see also text footnote 9). The constant terms remain relatively close to zero, reinforcing the proportional relationship. Similarly, the results from models (7), (9), and (11) support the latter part of Quantitative Hypothesis 1, confirming that the proportionality between RRPs' seat share and ministerial portfolio share holds even when ministerial portfolio importance is considered. The seat share coefficients are all highly significant at the 1% level and generally within the expected proportional range, though their proximity to 1 varies. The constant terms remain relatively close to zero, further reinforcing the proportional relationship.

Even when time is included as a control variable (Appendix 5), the analysis results remain largely unchanged from those presented above. Therefore, regardless of whether ministerial portfolio importance is considered, whether the analysis focuses on All Europe, Western Europe, or Eastern Europe, or whether the time variable is controlled, RRPs, like other traditional mainstream parties, demonstrate a strong proportional relationship between their seat share and ministerial portfolio share in coalition governments. Thus, seat share is a highly reliable predictor of ministerial portfolio share,21 and Quantitative Hypothesis 1 is supported.

However, it is also important to note that while RRPs exhibit a strong proportional relationship between their seat share in coalition governments and their ministerial portfolio share, as mentioned earlier, this relationship is not perfect. Except for model (5), RRPs often need to contribute a larger seat share to secure a comparable return in terms of ministerial portfolio share. Additionally, compared to Western RRPs, Eastern RRPs show a more proportional relationship between their seat share and ministerial portfolio share in coalition governments, regardless of whether ministerial portfolio importance is considered.22

The conclusions regarding Quantitative Hypothesis 2 are somewhat mixed. On one hand, seat share generally shows higher adjusted R2 values compared to the power index/vote weight, indicating that seat share tends to have stronger explanatory power for ministerial portfolio shares in most cases. On the other hand, except for model (6), the regression coefficients of the power index/vote weight are generally closer to one compared to those of seat share. Particularly when considering ministerial portfolio importance, RRPs' power index/vote weight shows an almost perfect proportional relationship with their ministerial portfolio shares in All Europe, Western Europe, and Eastern Europe. This indicates that, unlike traditional mainstream parties, for RRPs, the power index/vote weight, which represents bargaining power, has a stronger proportional relationship with the ministerial portfolio shares they receive in coalition governments compared to their seat share. Similarly, even when controlling for the time variable, the results remain nearly identical (Appendix 5), indicating that the power index/vote weight also proves to be a more reliable predictor of RRPs' ministerial portfolio shares than seat share. Therefore, Quantitative Hypothesis 2 is only partially supported.

4.3 Analysis outcomes of qualitative hypothesis

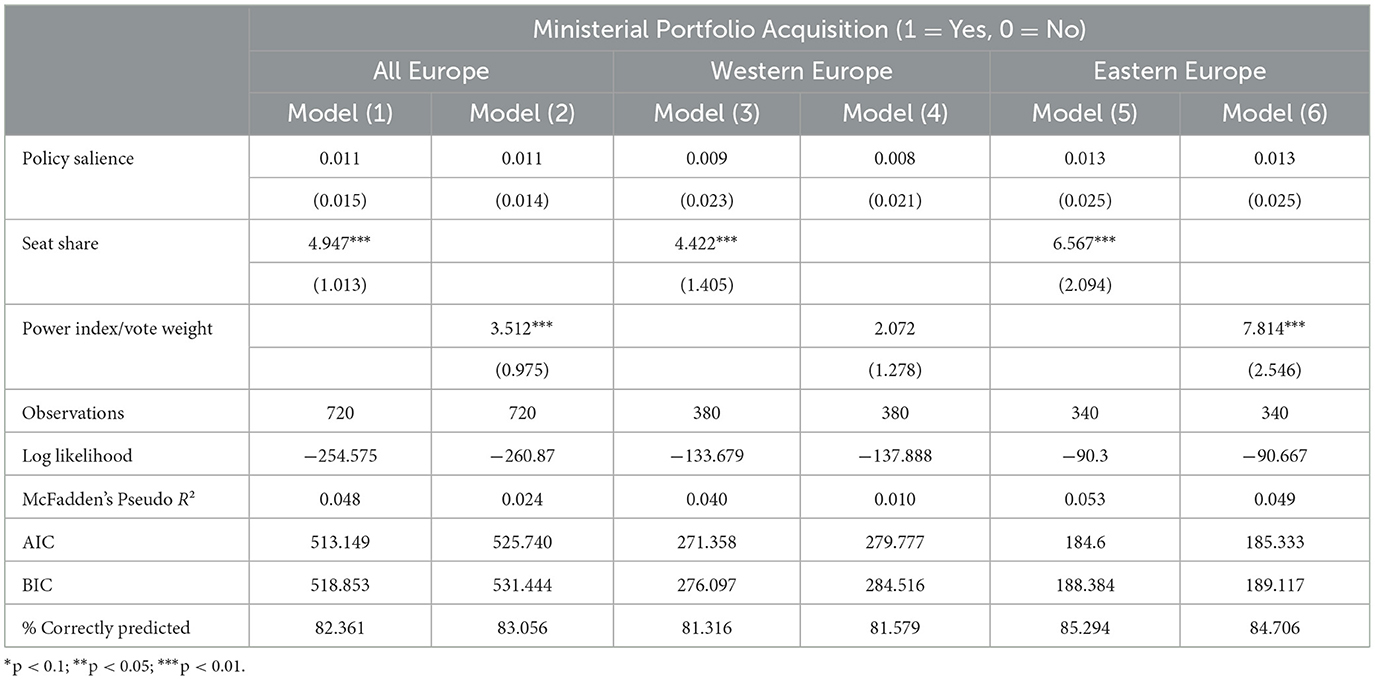

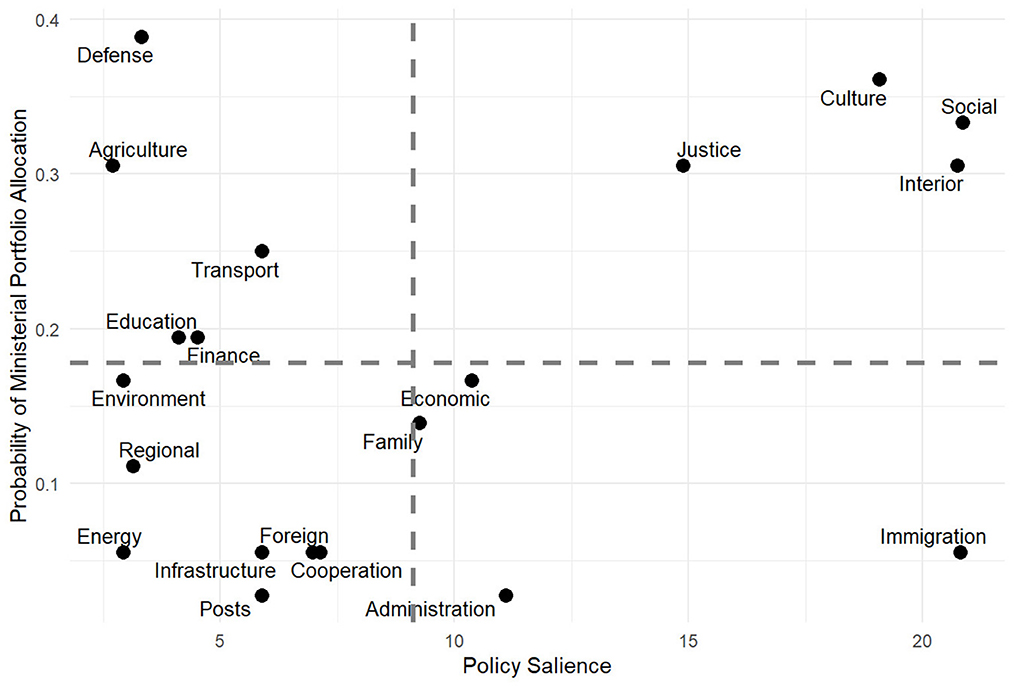

Table 4 presents the descriptive statistics for the conditional logit regression. From the results of the conditional logit regression (Table 5), since policy salience does not show statistical significance, RRPs, unlike other traditional mainstream parties, do not necessarily secure the ministerial portfolios they emphasize in their electoral manifestos when entering coalition governments. Figure 2 further confirms the robustness of the conditional logit regression results. In Figure 2, the vertical and horizontal dashed lines represent the mean values of the policy salience of ministerial portfolios and the probability of ministerial portfolio allocation, respectively. These two lines divide the 20 ministerial portfolios into four categories:

• The top-left quadrant includes five ministerial portfolios with low policy salience but high allocation probability.

• The bottom-left quadrant includes seven ministerial portfolios with both low policy salience and low allocation probability.

• The bottom-right quadrant includes four ministerial portfolios with high policy salience but low allocation probability.

• The top-right quadrant includes four ministerial portfolios with both high policy salience and high allocation probability.

This pattern reveals that while RRPs are relatively likely to be allocated ministerial portfolios they assign high policy salience to—such as those responsible for Social Affairs, Interior, Culture, and Justice—they often fail to secure others they also consider highly salient, such as ministerial portfolios covering Family Policy, Economic Affairs, Public Administration, and especially Immigration policy, which ranks highest in policy salience. At the same time, RRPs are frequently allocated ministerial portfolios they assign relatively low policy salience to, such as those responsible for Defense, Agriculture, Transport, and Education. Therefore, the Qualitative Hypothesis must be rejected.

Moreover, except for model (4), the seat share of RRPs in coalition governments and their power index/vote weight both demonstrate strong statistical significance. This indicates that, compared to the salience RRPs assign to specific policy areas, seat share and bargaining power remain the more influential factors in determining whether RRPs can secure a particular ministerial portfolio. Once again, even when controlling for the time variable, the results remain nearly identical (Appendix 5), further confirming the consistently strong association between seat share, power index/vote weight, and RRPs' qualitative allocation of ministerial portfolios.23

Additionally, the regression coefficients for seat share and power index/vote weight in Eastern Europe are noticeably higher than those in Western Europe, indicating that the influence of seat share and bargaining power on the allocation of specific ministerial portfolios is more pronounced for RRPs in Eastern Europe compared to Western Europe. Interestingly, the regression coefficients for seat share are higher than those for power index/vote weight for RRPs in Western Europe, whereas the opposite is true for RRPs in Eastern Europe. This suggests that the impact of seat share and power index/vote weight on the qualitative allocation of ministerial portfolios to RRPs varies across regions.

4.4 Robustness check: comparative case studies of Austria's FPÖ in 2017 and Slovakia's SR in 2020

To provide a more robust empirical foundation for the preceding analysis, this section presents a concise comparative case study of Austria's Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) in 2017 and Slovakia's Sme Rodina (SR) in 2020. These two cases were selected based on two key considerations. First, at the national level, Austria and Slovakia are neighboring countries with historically close ties. Importantly, while Austria represents Western Europe and Slovakia post-communist Eastern Europe, both countries operate under similar multi-party parliamentary cabinet systems and have experienced substantial influence from RRPs in their political landscapes. Second, at the party level, FPÖ and SR are not only members of the same RRP party family but also part of the Identity and Democracy political group in the European Parliament. Ideologically, the two parties are often seen as closely aligned (Antal, 2023, p. 33). Both have benefited from “reputational shields” (Ivarsflaten, 2006), have been centered around charismatic leadership figures (Heinz-Christian Strache for FPÖ and Boris Kollár for SR), and entered coalition governments as junior partners after spending more than a decade in opposition, each doing so as the third-largest party in parliament at the time. Given these parallels, the two cases are particularly well suited for a comparative analysis based on the most similar systems design.

Austria held its legislative election on October 15, 2017, in which the FPÖ secured 25.97% of the vote, becoming the third-largest party, just behind the Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) at 26.86%. Subsequently, in mid-December of the same year, the FPÖ officially joined the coalition government led by the first-place Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP, 31.47%), forming the Kurz I cabinet. According to Twist (2019, p. 74–76), despite not having governed together with the FPÖ for more than a decade, the ÖVP's decision to form a coalition government with the FPÖ—rather than with its traditional partner, the SPÖ—was grounded in the belief that such an alliance would allow the ÖVP to pursue more of its policy objectives. One of the key issues in the campaign was immigration and asylum, historically a core issue for the FPÖ. However, under Sebastian Kurz's leadership and the rebranding of the ÖVP as the “new People's Party”, the ÖVP increasingly encroached upon the FPÖ's issue ownership in this area, adopting many of its positions during the campaign. Conversely, in response to the growing importance of tax reduction as a campaign issue, the FPÖ strategically expanded its focus on economic matters in order to strengthen its bargaining position. It even released a dedicated economic platform during the election campaign. The convergence of ÖVP and FPÖ policy preferences was later reflected in the coalition agreement (Heinisch and Werner, 2021), which emphasized shared priorities on fiscal, immigration, and European issues—including income and tax cuts, reduced benefits and tighter asylum regulations, and rejection of Turkey's EU accession (Bodlos and Plescia, 2018, p. 1360–1361).

Under this coalition agreement, the FPÖ—with 51 parliamentary seats, accounting for 45.1% of the coalition government's seat share and a power index/vote weight of 0.333—was allocated 5 out of 14 ministerial portfolios, or 35.7% of the total, a distribution more closely aligned with its power index/vote weight than with its seat share. The five ministerial portfolios were: (1) Vice-Chancellor and Minister of Civil Service and Sport, and the Ministries of (2) Interior, (3) National Defense, (4) Health and Social Affairs, and (5) Infrastructure. Among these, the FPÖ secured the highly salient Ministry of the Interior (policy salience = 26.77), a key ministerial portfolio for controlling immigration and asylum policies. However, the reputational benefits of controlling this issue area were arguably diminished by the ÖVP's parallel appropriation of the same issue. While the FPÖ also obtained the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs (policy salience = 25.89), it failed to secure other ministerial portfolios it rated as highly salient, such as the Ministry of Justice (policy salience = 22.12) and the Ministry of Women, Family and Youth (policy salience = 12.17). Instead, it was allocated ministerial portfolios with lower salience for the party, including National Defense and Infrastructure (both at 4.87) (Lehmann et al., 2024). Given that even the SPÖ had expressed openness to forming a coalition government with the FPÖ prior to the election (Bodlos and Plescia, 2018, p. 1360; Twist, 2019, p. 81), the eventual distribution of ministerial portfolios appears underwhelming in light of the FPÖ's relatively strong strategic position during the coalition negotiations.

Slovakia held its legislative election on February 29, 2020. Founded in 2011, SR surprised many by securing 8.24% of the vote, becoming the third-largest party. Later that March, it officially joined the Matovič Cabinet—a coalition government led by the largest party, Obyčajní ludia a nezávislé osobnosti (OLaNO, 25.3%). The 2020 election was dominated by two long-standing themes in Slovak politics: corruption and redistribution. On the one hand, corruption had been a persistent concern since the early 1990s, gaining renewed salience in the late 2010s. On the other hand, since the early 2000s, party competition had increasingly centered on socio-economic questions, particularly regarding how to structure the economy to promote growth and how to equitably distribute its benefits. The ability to mobilize voters around these two themes was a decisive factor in OLaNO's electoral success (Haughton et al., 2022). SR emerged in this same political context, presenting a platform that combined concrete policy priorities—such as reforming Slovakia's poorly managed governance, fighting corruption, maintaining a strong anti-immigrant stance, and improving public services like healthcare and education—with a broader socio-political agenda focused on supporting low-income families and individuals, explicitly aiming to place social protection at the center of its program. These positions won the party substantial support among low-income and less-educated groups—particularly the working poor and so-called “precariat” (Školkay and Žúborová, 2019, p. 20–21; Sirovátka et al., 2022, p. 29; Antal, 2023, p. 35–36).

Upon entering the coalition government, SR held 17 parliamentary seats—accounting for 17.9% of the coalition's seat share—and had a power index/vote weight of 0.1. In return, it was allocated 2 out of 15 ministerial portfolios (13.3%), a share more closely aligned with its power index/vote weight than with its seat share. These included (1) Deputy Prime Minister and (2) Minister of Labor, Social Affairs and Family. The latter reflects the party's core emphasis on social welfare, while the former, which oversees legislation and strategic planning, aligns with SR's calls to reform public governance. During coalition negotiations, SR leader Boris Kollár also proposed an ambitious housing initiative—constructing 25,000 affordable rental units for low-income residents (Sirotnikova, 2020). While SR did not formally obtain the Ministry of Transport and Construction, which would oversee such a project, it reportedly secured the appointment of an ally to that post (Láštic, 2021, p. 353). Given SR's relatively weak position in the coalition government—especially compared to OLaNO's 53 seats—and the party's reputational vulnerabilities, including alleged ties to organized crime and its association with conspiracy theories, disinformation, and anti-immigrant rhetoric (Sirotnikova, 2020), its performance in securing key ministerial portfolios can be considered notably successful.

The brief comparative analysis of FPÖ and SR further reinforces the robustness of the findings presented in Sections 4.2 and 4.3. Specifically, it supports the following conclusions: (1) Seat share maintains a generally strong, though not perfect, proportional relationship with ministerial portfolio share; (2) Bargaining power exhibits a stronger proportional relationship with ministerial portfolio share than seat share does; (3) RRPs frequently receive a smaller ministerial portfolio share than their seat share would suggest; and (4) RRPs often fail to secure the specific ministerial portfolios they prioritize—though Eastern European RRPs appear somewhat more successful in doing so. The case of SR exemplifies this dynamic well: despite its comparatively weaker position relative to FPÖ during the same period, it nonetheless performed notably well in ministerial portfolio allocation. This may suggest that Eastern European RRPs rely more on “soft power”—including bargaining power—rather than “hard power” such as seat share. While these two cases do not fully illustrate the fifth finding from Section 4.2—namely, (5) that the proportional relationship between seat share and ministerial portfolio share is stronger for Eastern European RRPs than for their Western counterparts—there is indirect support for this conclusion. The proportional ratios (i.e., ministerial portfolio share divided by seat share) are relatively close across regions (West: 0.79 vs. East: 0.74), and given the significant disparity in party strength between FPÖ and SR, the fact that SR achieved comparable outcomes lends some additional credibility to this argument. The differences in ministerial portfolio allocation between FPÖ and SR—despite their strong similarities—may be attributed to a range of factors, including, but not limited to, the differing political, economic, and cultural contexts of Eastern and Western Europe. The following section will offer a more detailed discussion.

5 Discussion and limitations

Ministerial portfolio allocation is one of the most critical aspects of coalition formation, representing the foundation of the political process in parliamentary democracies. The study of ministerial portfolio allocation generally focuses on two dimensions: quantitative and qualitative. The quantitative allocation of ministerial portfolios examines how many ministerial portfolios each party receives, while the qualitative allocation focuses on which specific ministerial portfolios are assigned to each party. In terms of the former, the proportionality principle is regarded as one of the most reliable, well-known, and strongest empirical relationships in social science. As for the latter, scholars have argued that the more a coalition party emphasizes specific ministerial portfolios in its electoral program, the higher the likelihood that the party will secure those ministerial portfolios.

This paper explores the characteristics of the quantitative and qualitative allocation of ministerial portfolios to RRPs, which were once considered “pariah parties”. However, since the early twenty-first century, they have gradually undergone a process of normalization/mainstreaming. Increasingly, RRPs have entered coalition governments, accumulated governing experience, and begun to exert significant policy influence. Some RRPs are even seen as having achieved sustainable governance capabilities. Nevertheless, it is undeniable that in countries governed by RRPs, there has been a varying degree of democratic backsliding. Additionally, RRPs are perceived as significant threats and challenges to European and North Atlantic integration in international politics. Given that RRPs are typically junior partners in coalition governments, other coalition partners might be reluctant to allocate important ministerial portfolios overseeing domestic and/or international policy areas to them, or even to ministerial portfolios that RRPs themselves desire. This may result in the quantitative and/or qualitative allocation of ministerial portfolios to RRPs differing from that of traditional mainstream parties.

Based on the results of this paper's analysis, we find that regardless of whether ministerial portfolio importance is considered, and across all of Europe, Western Europe, and Eastern Europe, seat share shows imperfect but still strong proportional relationships with ministerial portfolio shares. However, while seat share typically shows higher adjusted R2 values compared to power index/vote weight, the regression coefficients of power index/vote weight are generally closer to one than those of seat share. Especially when considering ministerial portfolio importance, whether in all of Europe, Western Europe, or Eastern Europe, the power index/vote weight of RRPs shows an almost perfect proportional relationship with their ministerial portfolio shares. This indicates that, unlike traditional mainstream parties, for RRPs, bargaining power has a stronger proportional relationship with the ministerial portfolio shares they receive in coalition governments compared to their seat share. This result somewhat confirms our previous conjecture: because RRPs in coalition governments are always typically weaker junior partners—and particularly given their anti-liberal democratic tendencies and their incomplete mainstreaming (see also text footnote 6), that is, operating within highly unfavorable contexts—their ability to obtain ministerial portfolios proportional to their contributions depends more on their bargaining power.

Moreover, RRPs often receive fewer ministerial portfolio shares in coalition governments than their seat shares would suggest—a pattern that runs counter to the classic “relative weakness effect” (see also text footnote 2) and may further reflect the unique ideological and reputational features of RRPs. However, Eastern European RRPs show a better proportional relationship between their seat shares and ministerial portfolio shares in coalition governments than Western European RRPs, regardless of whether ministerial portfolio importance is considered. This implies that, compared to Western Europe, Eastern European RRPs encounter fewer obstacles on their path to normalization/mainstreaming—possibly due to the region's distinct post–World War II history, the challenges of nation-building amid ethnic diversity, limited democratic experience, the rapid transition from state socialism to a market economy, and a relatively less institutionalized and more fluid party system (Minkenberg, 2002; Buštíková, 2018). Therefore, although Eastern European RRPs are generally less successful overall than their Western counterparts (see also Figure 1), their characteristics in quantitative ministerial portfolio allocation more closely resemble those of traditional mainstream parties.

Finally, the Qualitative Hypothesis of this paper is found to be unsupported. This result confirms our earlier conjecture that coalition partners are often reluctant to grant ministerial portfolios that are likely related to critical domestic and/or international policy areas, or even the ministerial portfolios RRPs desire—such as those responsible for Family Policy, Economic Affairs, Public Administration, and especially Immigration policy. This conjecture is also partially supported by Kimberly A. Twist's research. By examining six traditional mainstream right parties and the coalition governments they participated in across five countries—Austria, Denmark, Italy, the Netherlands, and Norway—she found that these parties tend to hold slightly more key ministerial portfolios in coalitions with RRPs than in those without them, regardless of the role of policy preferences (Twist, 2019, p. 25–26).24

Furthermore, the influence of seat share and power index on the allocation of specific ministerial portfolios is more pronounced for RRPs in Eastern Europe compared to Western Europe. At the same time, seat share, as a form of “hard power”, plays a more crucial role than bargaining power, considered “soft power”, in determining whether RRPs in Western Europe can secure specific ministerial portfolios. In contrast, the reverse is true for RRPs in Eastern Europe. These observations further highlight that, although Eastern European RRPs are relatively weaker than their Western counterparts, they face fewer barriers to normalization/mainstreaming—potentially making it somewhat easier for them to secure the specific ministerial portfolios they prioritize.

Taken together, the above findings are further corroborated by the concise comparative case studies presented in this paper, which reinforce the empirical credibility of the results. In summary, although RRPs have made notable progress toward normalization/mainstreaming in the quantitative allocation of ministerial portfolios, they continue to encounter substantial challenges in the qualitative allocation, where normalization/mainstreaming remain largely unrealized.

This paper makes significant contributions to advancing research on ministerial portfolio allocation, RRPs, and the relationships between them. However, we also acknowledge some limitations. First, since RRPs' participation in government has increased only gradually since the early twenty-first century, this study, being a “small-N” study, employs the most traditional and straightforward analytical methods. As the sample size increases, however, it is reasonable to expect that previous results—particularly those from the conditional logit regression—may change. At the same time, this study does not incorporate control variables in the quantitative analysis that could also potentially influence the quantitative and/or qualitative allocation of ministerial portfolios to RRPs—such as a communist past, the duration of democratic rule, the length of EU membership, prior electoral success or government participation, and the policy distance between coalition partners.

Second, although the significant development of RRPs' normalization/mainstreaming over time has been confirmed by previous scholarly research, the additional analyses conducted in this paper, which included time as a control variable, found that time was not statistically significant (Appendix 5). This result could be attributed to a small sample size or other technical factors, but it may also be because time represents only the visible tip of the iceberg, while the potential control variables mentioned earlier constitute the massive, hidden iceberg beneath the surface. We encourage other scholars to utilize the publicly available dataset (Appendices 1, 3, 4) to replicate this study, evaluate its findings, and refine its conclusions using alternative research methods.

Third, compared to more meticulous case studies, this study, being a “large-N” study, may overlook important national contexts, such as Switzerland's “magic formula,” the oversized coalitions in Southern European countries, the tradition of minority coalitions in Northern European countries, or the “red-brown alliance” in Central and Eastern European countries. These factors are also likely to influence the quantitative and/or qualitative allocation of ministerial portfolios to RRPs.

Fourth, some crucial variables related to political party interactions could also impact the quantitative and/or qualitative allocation of ministerial portfolios to RRPs. For instance, the willingness of other parties to govern with RRPs. Given that policies adopted in parliamentary systems reflect a compromise among the policy positions of coalition parties, and that coalition parties may allocate ministerial portfolios with future policy-making in mind, RRPs' non-cooperative nature or their excessive policy distance from other coalition parties in certain policy areas (e.g., immigration) could significantly affect their coalitionability (Martin and Vanberg, 2014; Bassi, 2017; Backlund, 2023). Another example is the RRPs' willingness to enter a coalition government. If RRPs are unlikely to obtain their desired ministerial portfolios, why would they choose to join a coalition government in the first place? Could it be, as Riker (1962, p. 22) argued, that gaining access to power is the ultimate goal in party politics—leading RRPs to accept concessions in ministerial portfolio allocation as the price for entering government? The case of the Rassemblement National (RN) in France appears to support this view. Since 2011, the RN has pursued a strategy of “dédiabolisation”—aimed at gaining governmental credibility—by making significant efforts to moderate its rhetoric and policies in pursuit of its long-term ambition of assuming government power, even going so far as to soften its stance on core issues such as immigration (Ivaldi, 2016). It is therefore conceivable that, in order to join a coalition government (as forming a government alone remains unimaginable), the RN would be willing to forgo some ministerial portfolios it considers important. Beyond these factors, instances where coalition entry is enforced due to sheer party size (Tronconi, 2015) could also influence the quantitative and/or qualitative allocation of ministerial portfolios to RRPs. The factors mentioned above warrant further investigation.

6 Conclusion

This paper may also offer potential directions for future research. First, do the characteristics of ministerial portfolio allocation to RRPs in national governments also apply to RRPs in regional governments? Given the lower importance and sensitivity of ministerial portfolio allocation in regional governments, will RRPs be more similar to other traditional mainstream parties in receiving a better proportional allocation of ministerial portfolios and/or obtaining the ministerial portfolios they desire? Second, can specific case studies further substantiate or refute the important conclusions of this paper, such as “RRPs need to rely more on their own bargaining power” or “coalition partners are often unwilling to allocate ministerial portfolios related to important domestic and/or international policy areas to RRPs”? Third, do the characteristics of ministerial portfolio allocation to RRPs apply to Radical Left Parties like Syriza, Podemos, and the Socialist People's Party of Denmark, or Valence Populist Parties like Italy's Movimento 5 Stelle (Zulianello and Larsen, 2024), which, like RRPs, are increasingly entering coalition governments? What are the similarities and differences in ministerial portfolio allocation to these different types of parties that are in the process of normalization/mainstreaming? Fourth, a more important and challenging question concerns the role of these diverse radical and populist parties after entering government: How do they influence policy-making? What kinds of policy outcomes do they produce? What impact do they have on the overall quality of democracy? Exploring these questions through the lenses of historical political culture, institutional structures, media discourse, and elite behavior could prove especially useful in explaining cross-national variation and differences across party families. We believe that pursuing these research avenues would significantly advance the broader scholarly understanding of ministerial portfolio allocation, RRPs, and their interplay with democratic governance.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary material.

Author contributions

TT: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Grant Number: 23K18755).

Acknowledgments

A draft of this research was presented at the 2024 Annual Meeting of the Japanese Association of Comparative Politics (Session: Open Theme C) on June 22, 2024, in Osaka, Japan. This research has greatly benefited from the generous support of many scholars, including Mitsuo Koga (Chuo University), Takako Imai (Seikei University), Takeshi Hieda (Osaka Metropolitan University), and Serika Atsumi (Tokyo University). The author also extends heartfelt gratitude to the reviewers for their highly professional, detailed, and actionable feedback, which has significantly enhanced the readability and scientific rigor of this paper. Any remaining errors and shortcomings are entirely the responsibility of the author.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2025.1500403/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^In this paper, the term RRPs is used in a broad sense to refer to parties that are positioned further to the right than traditional mainstream right-wing parties, such as conservatives or liberals. While RRPs accept the essence of democracy, they are considered anti-system parties, meaning that they are hostile to fundamental elements of liberal democracy, such as minority rights and the rule of law (Mudde, 2019, p. 7–8).

2. ^As shown by the regression coefficient here, the proportionality principle is not strictly followed in ministerial portfolio allocation. Over the years, many researchers have identified a small deviation in which smaller parties tend to receive additional or “bonus” ministries beyond their proportional shares, while larger parties tend to give up such ministries. This deviation is commonly referred to as the “relative weakness effect” (Browne and Franklin, 1973, p. 460; Schofield, 1976, p. 34; de Mesquita, 1979, p. 71; Browne and Frendreis, 1980, p. 767; Raabe and Linhart, 2013, p. 487; Martin, 2018, p. 1184).

3. ^It should be noted that the bargaining model theory posits that parties with a higher power index/vote weight have a more advantageous position in coalition government negotiations. Consequently, these parties can leverage their superior bargaining power to secure more ministerial portfolios than what the proportionality principle would suggest. This view has been supported under certain specific conditions or contexts, such as in less-advanced Eastern European countries (Druckman and Roberts, 2005), the absence of a vote of no confidence (Golder and Thomas, 2012), the intra-party factions of the Liberal Democratic Party of Japan (Ono, 2012) or Italian parties (Ceron, 2014), the regional branches of the German Social Democratic Party (Ennser-Jedenastik, 2013), and the sequential allocation process (Ecker et al., 2015).

4. ^The statistical significance of the proportionality principle can be even stronger in certain specific contexts, such as political systems characterized by a small number of parties and connected coalitions (Schofield and Laver, 1985), coalition governments based on pre-election pacts (Carroll and Cox, 2007), or when using methods that estimate time-varying measures of ministerial portfolio importance (Bucur, 2016).

5. ^It is worth noting that, similar to the quantitative theory (see also text footnote 2), the predictive power of the qualitative theory also varies across countries—ranging from below 44% in Belgium to above 70% in Germany. Two main factors are thought to influence this variation: the number of cabinet parties that typically form coalition governments in a given country, and the distinctive national experiences of parties in forming and cooperating within such governments (Bäck et al., 2011, p. 465).

6. ^Mirko Crulli and Daniele Albertazzi's recent research argues that the increasing frequency with which RRPs enter coalition governments only fulfills a functional interpretation of being mainstream. To determine whether RRPs are fully mainstream, one must also consider whether their attitudes are widely shared by the majority of the public, without any statistically or substantively significant differences in endorsement across political groups. From this attitudinal perspective, RRPs clearly do not qualify as fully mainstream. Therefore, the authors suggest that RRPs would be more accurately defined as “‘established but not mainstream' in contemporary European politics” (Crulli and Albertazzi, 2024, p. 23). We agree with this perspective. However, to avoid conceptual disputes, we have decided to use the prefix “traditional” when referring to parties generally accepted as fully mainstream, such as liberal or social democratic parties, to differentiate them from RRPs, which are also sometimes referred to as the “new” mainstream (Vampa and Albertazzi, 2021, p. 283–284).

7. ^Except for the single-party governments led by Hungary's Fidesz and Poland's Law and Justice Party.

8. ^Western Europe: (1) Austria, (2) Netherlands, (3) Switzerland; Northern Europe: (4) Finland, (5) Norway; Eastern Europe: (6) Bulgaria, (7) Estonia, (8) Latvia, (9) Poland, (10) Slovakia; Southern Europe: (11) Cyprus, (12) Greece, (13) Italy. In subsequent analyses, due to the limitation of sample size, these 13 countries are grouped into two regions: Western Europe (including Northern and Southern Europe) and Eastern Europe.

9. ^When testing the hypothesis of whether RRPs conform to the proportionality principle using H0: β = 0 as the null hypothesis, if β is assumed to be 0.5 and the standard error is small, it is still statistically significant to reject H0: β = 0, indicating that RRPs follow the proportionality principle. However, since β = 0.5 is less than β = 1, it does not indicate a strict proportional relationship. Therefore, setting the null hypothesis as H0: β = 1 might be more appropriate, as it directly tests whether RRPs strictly follow the proportionality principle. We are grateful to Takeshi Hieda (Osaka Metropolitan University) for providing this valuable suggestion. However, we did not adopt this approach because, as noted in text footnote 2, the proportionality principle is often not strictly followed in the actual process of ministerial portfolio allocation, which becomes even more evident when examining this principle by country. An analysis of ministerial portfolio allocation in 14 Western European countries found that although parties' ministerial portfolio payoffs are generally determined by their contribution of seats to coalition governments (β = 0.782), the β values across countries fluctuate between 0.52 (Iceland) and 0.938 (France). Thus, the ministerial portfolio allocations in most countries do not adhere strictly to the proportionality principle (Bäck et al., 2009, p. 17; see also Schofield and Laver, 1985, p. 160, and Indridason, 2015, p. 12). As a result, setting the null hypothesis as H0: β = 1 would lead to the conclusion that most cases do not conform to the proportionality principle, even though we know this is not entirely accurate. Therefore, this paper continues to use H0: β = 0 as the null hypothesis.

10. ^These seven ministerial portfolios are: (1) Agriculture; (2) Defense; (3) Education; (4) Finance; (5) Foreign Affairs; (6) Interior; and (7) Justice.

11. ^It is important to note that the names and responsibilities of ministerial portfolios vary between countries. Therefore, to better illustrate the characteristics of the ministerial portfolios held by RRPs, the ministerial portfolio shares displayed in this figure do not represent the actual numerical shares. Instead, they show the share of each policy domain managed by RRPs relative to all the policy domains they oversee. For example, from 2004 to 2007, the Swiss People's Party held a ministerial portfolio titled Minister of Defence, Civil Protection, and Sport. To more intuitively convey the characteristics of this ministerial portfolio and facilitate comparisons with cases from other countries, I divided it into three separate ministerial portfolios: (1) Defence; (2) Interior; and (3) Culture, Public Services, Sports, Tourism. However, in subsequent regression analyses, when we examine the quantitative allocation of ministerial portfolios to RRPs, we use the actual number of ministerial portfolios. When we examine the qualitative allocation of ministerial portfolios to RRPs, we use the adjusted number of ministerial portfolios. The actual and [adjusted] numbers of ministerial portfolios held by RRPs in different regions are as follows: All Europe (283 [348]), Western Europe (32 [54]), Northern Europe (40 [44]), Eastern Europe (124 [146]), and Southern Europe (87 [104]) (see also Appendix 1).

12. ^https://ejpr.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/20478852

13. ^In calculating the power index/vote weight, we utilized an online algorithm program based on the fundamental definition by Shapley and Shubik (1954) (https://homepages.warwick.ac.uk/~ecaae/ssdirect.html). This algorithm has the advantages of being simple and providing exact values for the power index/vote weight. The correlation coefficients between the seat share of RRPs in coalition governments and their power index/vote weight for All Europe, Western Europe, and Eastern Europe are 0.873, 0.863, and 0.805, respectively.

14. ^https://whogoverns.eu/cabinets/

15. ^The database records changes in the cabinet when: (1) there is a change in the partisan composition of the government coalition; (2) the Prime Minister leaves office; and (3) parliamentary elections are held, even if there is no resulting change in the partisan composition of the cabinet. As one reviewer insightfully pointed out, the integration of RRPs into coalition governments cannot be divorced from regime type. Fortunately, this factor does not substantially affect the analysis presented in this paper, for several reasons. First, the focus here is not on why traditional mainstream parties accept RRPs, but rather on how many and what kinds of ministerial portfolios RRPs receive after successfully entering coalition governments. Second, of the 13 countries examined, all except Cyprus, Poland, and Switzerland are republics with a multi-party parliamentary cabinet system. Third, due to data limitations, Cyprus is not included in the analysis of the qualitative allocation of ministerial portfolios (see also text footnote 19). Fourth, Poland is commonly classified as a semi-presidential regime with a strong parliamentary character—specifically, a form of “premier-presidentialism” (Elgie, 2011, p. 27–29)—and Switzerland's collegial executive system, often referred to as the “magic formula”, also operates within a strong parliamentary framework (Cruz et al., 2021).