- 1School of Marxism, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China

- 2Department of Politics and International Relations, University of York, York, United Kingdom

Policy agenda-setting is a crucial indicator of a political system’s nature and openness, reflecting the political attitudes and value orientations of its decision-makers. In China’s authoritarian context, where centralised control and strategic governance dominate, the rise of online political engagement has made Internet-based focusing events key drivers in shaping policy agendas. This study examines how these events influence policy prioritisation within the Chinese political system. Utilising Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA), this research develops a framework that incorporates ‘actor-driven’ and ‘opportunity-coupling’ factors to explore the impact of these events on policy formulation. The findings reveal that the Chinese government strategically manages its responsiveness to public discourse, aligning policy shifts with broader state objectives. By analysing the dynamics of policy-setting in China’s digital age, this study enhances the understanding of how authoritarian resilience is maintained through the interaction between state control and online public engagement.

1 Introduction

Establishing policy agendas, where public decision-making entities recognise, prioritise, and select societal issues that require urgent solutions, is a critical entry point in political systems (Easton, 1999). This process serves as the primary mechanism for translating diverse social demands into the political domain, initiating a policy cycle that progresses from problem identification to solution development, enactment, and feedback (DeLeon, 1994). The configuration of policy agendas is not only indicative of a political system’s responsiveness but also reflects its openness and democratic characteristics, as it reveals the political attitudes and values of decision-makers (Feng, 2020).

Western scholarship has long described China as an authoritarian regime (Ma and Cao, 2023). In authoritarian regimes, the formation of policy agendas plays a crucial role in maintaining the legitimacy of the state while managing societal demands. Unlike democratic systems where public participation in agenda-setting is more direct, authoritarian regimes must carefully balance control with responsiveness to avoid instability. How these regimes set their policy agendas provides deep insight into their underlying governance strategies (Nathan, 2003). Recent studies have increasingly focused on how authoritarian regimes, particularly in China, adapt their strategies to maintain legitimacy in the face of rising public expectations and technological advancements (Repnikova and Fang, 2018; Stockmann, 2013; Truex, 2016; Weng et al., 2021).

With the advent of the Internet era, the dynamics of policy agenda-setting have undergone significant changes. The Internet has emerged as a powerful platform through which citizens can express their views, engage in political activities, and raise concerns that might otherwise be overlooked in more controlled environments (Ma and Cao, 2023). This shift has been particularly evident in China, where the internet has become a double-edged sword for the government: providing a means for the state to monitor public opinion and also enabling the rapid spread of ‘focusing events’—highly visible incidents that capture widespread attention and have the potential to influence policy agendas (Birkland, 1997; Shirk, 2011).

Focusing events in the digital age are shaped through interactions between public discourse, media coverage, and government responses. In this era of rapid information spread, these events can quickly mobilise public opinion and attract attention from citizens and the state. Online discourse plays a crucial role, enabling swift dissemination and discussion of incidents that might remain localised (Luo, 2014; Shirk, 2011). This dynamic elevates the visibility of issues and frames them to challenge or reinforce governmental narratives.

The Chinese government’s response to digitally amplified focusing events exemplifies ‘responsive authoritarianism’. The regime monitors and engages with public opinion to maintain stability and reinforce legitimacy (He and Warren, 2011; King et al., 2013). Instead of relying solely on repression, it addresses grievances by adjusting policies or taking visible action, demonstrating responsiveness while retaining control. This approach allows adaptation to challenges without altering authoritarian nature. Managing events effectively is critical to ‘authoritarian resilience’, which is the ability of regimes to withstand pressures, including those from technology and changing public expectations (Nathan, 2003; Weiss, 2014).

Understanding how online focusing events affect policy agenda-setting in China is vital, given the need to maintain control and address public concerns. The response is influenced by factors like perceived threats to stability, the need to manage opinion, and using state media to control narratives (Stockmann, 2013). This is enhanced by advanced technologies like big data analytics and artificial intelligence, which help the government monitor and preempt public reactions (Dai et al., 2021). Swift data analysis allows assessment of focusing events’ impact on stability and policy response.

This study examines when online focusing events lead to policy agenda establishment in China, using a cross-case Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) that integrates ‘actor-driven’ and ‘opportunity-coupling factors’. It draws on theories such as media agenda-setting (McCombs and Shaw, 1972), multiple streams (Kingdon, 1984), and punctuated equilibrium (Baumgartner and Jones, 1993) to explore the relationship between government recognition, public opinion, and available solutions for policy responses.

This research enhances the understanding of authoritarian resilience, showing that China’s regime is adaptable and responsive within its structure. Findings indicate that the government’s sensitivity to public opinion rivals more democratic systems, but remains tightly controlled and strategically managed, reflecting the balance between control and responsiveness in preserving authoritarian resilience (Luo, 2014; Truex, 2016). This study refines existing theories on policy agenda-setting in authoritarian contexts and provides new insights into the dynamics of governance in China’s Internet age. This study highlights how the Chinese government’s responses to online focusing events reveal both the strengths and limitations of its authoritarian resilience, offering a deeper understanding of the interaction between the state and society in contemporary China.

2 Ongoing intellectual debates

The phenomenon of focusing on events significantly influences policy agenda-setting. Cobb et al. (1976) identify focusing events as catalysts that elevate social issues within the policy agenda-setting process. Birkland (1997) has emphasised the disruptive power of focusing events in pushing issues on the government’s agenda. Dearing and Rogers (2009) have noted that the severity and urgency associated with focusing events introduce complexity into the policy agenda. Furthermore, Kingdon (1984) and Gershton (2001) recognise focusing events as triggers for public policy changes.

Extensive research has been conducted on the factors influencing the impact of focusing events on policy agendas. Cobb and Elder (1971) highlight the importance of attention in triggering policy changes. Birkland (1998) has argued that focusing events must capture the interests of decision-makers and meet their political needs. Anderson (2009) highlights the visibility of social conflicts through focusing events. Gershton (2001) and Kingdon (1984) discuss the role of personal experiences, potent symbols, and other factors in elevating issues within the policy agenda.

In China, the dynamics of policy agenda-setting triggered by focusing events are shaped by the country’s unique political structure and the role of digital media. Chinese scholars have conducted localised studies on policy agenda-setting, emphasising various critical factors within an authoritarian regime. Li (2012) emphasises the need for specific objectives in policy agendas, while Chen and Wang (2013) highlight the amplifying role of emerging media. Zhao and Xue (2017) view the policy agenda as a ‘responsive’ model, driven by the manner and intensity of events, echoing the broader theory of ‘responsive authoritarianism’ discussed by scholars such as Qiaoan and Teets (2019). This concept reflects how the Chinese government, under Xi Jinping’s administration, has increasingly centralised power and used ideological control to respond selectively to focusing events, particularly those amplified by social media.

Wang and Wu (2019) have identified concrete interest demands as necessary for triggering policy agendas, whereas Wu and Wang (2021) have noted the reasons for the failure of focusing events in setting policy agendas. These observations align with Liu and Chan’s (2018) framework for crisis-induced agenda-setting in China, where government-led narratives play a pivotal role in shaping public responses and determining whether a focusing event leads to substantive policy changes.

Huang et al. (2019) have identified ‘event attributes’ and ‘attention’ as key elements in propelling policy agendas, which is particularly relevant in the digital age where online platforms can significantly amplify the visibility and perceived importance of certain issues. Jia (2019) has further elaborated on this by examining the dynamics of online public opinion in China, noting that the government’s responsiveness to online discourse is often selective and aimed at quelling dissent rather than addressing the root causes of public concern.

The restoration process of policy agenda setting triggered by focusing events has also been studied, with many researchers utilising Kingdon’s multiple streams theory to describe the convergence of problem, policy, and political streams, opening the ‘policy window’ (Wang and Qu, 2017). Baumgartner and Jones’ punctuated equilibrium theory provides another lens through which to understand policy evolution and change, particularly in the Chinese context, where sudden policy shifts can occur following major focusing events (Peng, 2020; Wu and Huang, 2021). Specific case studies include the introduction of the ‘Vaccine Administration Law’ (Bai and Huang, 2020) and public crisis responses (Guan, 2021). These case studies reflect how the Chinese government leverages focusing events to justify significant policy changes and maintain stability.

Moreover, the role of elite bargaining and leadership priorities in China has been emphasised in studies such as those by Chan et al. (2021), who highlight how leadership decisions override public opinion, even in cases of widespread online discourse. This is consistent with the broader strategy of maintaining ‘authoritarian resilience’, as described by Weiss (2014), where the state adapts to new challenges without relinquishing control. Wang (2022) further illustrates this by examining how the Chinese government used social media during the COVID-19 pandemic to manage public perception and maintain stability.

Existing research validates the practical significance of focusing events on policy agenda-setting, demonstrating the ability to elevate certain issues to the top of governmental agendas, particularly during crises or periods of public discontent. However, key areas in China require further investigation to fully understand this process. One critical area is the distinct characteristics of focusing events in the Internet age, in which digital platforms can rapidly amplify events, creating widespread public attention almost instantaneously. This amplification influences not only the speed and intensity with which these events impact policy agendas but also introduces new dynamics in government monitoring and response. The role of digital media in shaping public discourse and governmental action in China is particularly significant, as the state strategically uses censorship and propaganda to either suppress or amplify narratives, thereby affecting the trajectory of focusing events differently from more open societies.

Moreover, while Western theories on policy agenda-setting, such as Kingdon’s multiple stream framework and Baumgartner and Jones’s punctuated equilibrium theory, have been instrumental in understanding focusing events, their applicability to China’s authoritarian regime requires careful examination. The centralised decision-making process in China, combined with the unique role of the Communist Party, suggests that the processes described by these theories may not fully capture how focusing events influence policy agendas. Recent studies have highlighted the importance of elite bargaining and top-down directives in agenda-setting, indicating that modifications to these theories may be necessary to account for the Chinese context. Integrating insights from these studies helps clarify how focusing events are managed within China’s political and social framework, particularly as the government navigates the complex digital landscape. This approach enhances the theoretical vitality and universality of existing frameworks when applied to non-Western authoritarian contexts, such as China, offering a deeper understanding of how digital media, government strategies, and public sentiment interact to shape policy outcomes.

3 Theoretical framework

3.1 Ongoing theoretical debates

Since the latter half of the last century, public policy research has transitioned from abstract description to empirical analysis, driven by questions about the traditional rationalist path and the rise of behaviourism. This shift has produced theories with enhanced explanatory power, derived from inductive reasoning and quantitative methods. Specifically, the policy agenda domain has benefited from new theoretical models developed by scholars such as Cobb, Birkland, Kingdon, and Anderson. Therefore, examining and integrating these contributions is invaluable to understanding China’s policy agenda-setting process.

First, Cobb and Elder have categorised policy agendas into system (public) and institutional agendas (government). System agendas refer to social issues that capture public attention, leading to discussions and the formation of influence within society, eventually prompting a government response (Chen, 1993). In contrast, institutional agendas involve issues that decision-makers consider as requiring attention and resolution, representing the final stage of agenda-setting. Moreover, media coverage often amplifies social issues that require interactions between the public and interest groups before setting a policy agenda (Cobb and Elder, 1983; Liu, 2011).

Similarly, Anderson’s views align with the concept that system agendas necessitate public discourse to urge government action, whereas government agendas comprise issues that officials deem necessary to address (Anderson, 2009). Cobb and Elder’s stage development theory suggests that external societal forces influence policy agendas. Consequently, this theory lays the foundation for understanding how societal issues first enter the public eye, then the government agenda, and finally affect the policy agenda (Liu, 2011).

McCombs and Shaw’s media agenda-setting theory emphasises the media’s role in influencing public opinion and setting the government’s agenda. They propose that the mass media could set societal issues for discussion and prioritise them, influencing what people think about and in what order. This process follows a sequence in which the media guides the public, who then pressures the government, thus transferring the agenda among these three entities (McCombs and Shaw, 1972). Furthermore, the theory distinguishes between ‘agenda-setting’, which studies the media’s influence on the public, and ‘agenda-building’, which examines the influence of public and media agendas on decision-makers (Chang, 2000; Entman, 2004).

Moreover, JoKingdon’s Multiple Streams Framework, building on the ‘Garbage Can Theory’, systematises how officials notice issues, select solutions, and set policy agendas. Kingdon identifies three streams: the problem, political, and policy streams. Typically, the convergence of these streams determines the likelihood of issues being addressed and solutions being selected (Kingdon, 1984).

In addition, Anderson’s Trigger Mechanism Theory suggests that societal issues transform into policy issues through a ‘trigger-like’ mechanism, including crisis events, media reports, social protests, and political elites. In today’s digital era, this theory is particularly relevant as emergencies often lead to policy innovation. Significant events act as catalysts that aggregate public agendas and pressure governments to improve public policies (Anderson, 2009).

Furthermore, the attention theory proposed by Arrow and Simon challenges the notion of fully rational decision-making by highlighting the limitations of human cognitive capacity and the ‘attention bottleneck’. This theory explains the constraints entities face in influencing the policy agenda and the reasons for the agenda’s declining phase (Arrow, 1970; Simon, 1983). Anderson mentions that what prompts the policy agenda is the demand that decision-makers notice and deem necessary to address (Anderson, 2009). Baumgartner and Jones view attention as a ‘lever’ of policy agenda-setting, with the political system’s attention being limited. Consequently, incidents that become the focus can bring social issues to light but may also disappear as attention wanes (Baumgartner and Jones, 1993). The attention theory highlights the ‘timeliness’ of policy agenda-setting, providing a dynamic perspective for research and deeply explaining the constraints faced by various entities in influencing the policy agenda. It also indirectly supplements the reasons for the policy agenda falling into the ‘decline phase’ abyss (Downs, 1972).

3.2 Media control, symbolic participation, and the duality of the digital space in authoritarian regimes

In authoritarian regimes like China, the media does not serve as a neutral space for public dialogue; instead, it acts as a tool for crafting narratives that legitimise political power. This study utilises Herman and Chomsky’s propaganda model (1988), initially designed to critique how ruling elites manipulate mass media in liberal democracies, to analyse media in China, where it aligns closely with state interests and employs ‘conditional visibility’ alongside superficial responsiveness. The model indicates that media organisations filter information through ideologically, economically, and politically motivated lenses to protect the interests of prevailing power structures. In authoritarian settings, these filters intensify due to direct state intervention, institutional capture, and the integration of media into government processes. This explains why state-affiliated media organisations operate under stringent government regulations.

This model illustrates what He and Warren (2011) refer to as responsive authoritarianism, wherein the authoritarian regime pretends to be responsive and tries to create an illusion of deliberation to escape demands for significant structural reform. Through a controlled media landscape, consisting of party-affiliated and state-owned newspapers and broadcasters, the government amplifies specific narrative-defining ‘focusing events’ while suppressing those considered disruptive. Consequently, this leads to a constructed public agenda that seems responsive but is thoroughly restricted and fundamentally unresponsive.

The internet and social media introduce a new facet to this issue. These platforms offer various digital tools, enabling individuals to express themselves more freely, collaborate, and disseminate information. Yet, this freedom is accompanied by authoritarian surveillance and censorship strategies, including content manipulation and control over digital environments. According to MacKinnon (2011), China serves as a prime example of networked authoritarianism, where the digital realm is not entirely oppressive or completely free; instead, the government regulates it to permit limited expression while undermining social challenges.

According to King et al. (2013), China’s censorship system permits local critiques while suppressing calls for collective action. In a self-creation process, Repnikova (2017) notes that state media increasingly utilise techniques that invite public participation in a constructed dialogue. Viewed in this light, the internet functions as a paradoxical political arena, serving as both a means of control and a space for resistance, where expression and surveillance coexist alongside symbolic involvement and discursive governance.

This reasoning aligns with Ma and Cao's (2023) analysis of pseudo participation in China’s hybrid political system. Their typology illustrates how individuals partake in ‘political’ activities, such as viewing state-approved news, sharing promotional materials, and ‘attending’ consultations, all of which are carefully controlled to prevent any real power from being exercised. While these actions are presented as participatory, they are mostly superficial and integrated into broader legitimisation efforts. Consequently, this results in a framework for symbolic participation, relegating citizens to politically ritualistic activities that uphold the party’s dominance without allowing for the real emergence of democracy.

Managed engagement plays a pivotal role in the stability of authoritarian regimes, as highlighted by Nathan (2003); it emphasises the political control maintained through adaptable governance frameworks and institutional flexibility. In the context of China, the digital public space is not entirely muted; rather, it is systematically woven into the control apparatus. While some events catch public interest, they are not amplified solely to foster engagement, but are instead utilised to bolster the illusion of state responsiveness within very narrow confines. Thus, engagement serves as a tool for symbolic integration and automates the façade of grassroots legitimacy, even though such engagement is orchestrated through narrative management and regulated narrative transparency.

This fundamental understanding of the information environment systems prepares one to examine the relations between actions and opportunity combinations that follow. Within China’s authoritarian environment, media, scholars, and the populace do not operate individually but rather in a systematic grid bounded by the state’s constraints and calculated possibilities. The internet does not serve solely as an active trigger for political change or as a dormant enhancer; it functions as a contested space that is integrated into the state and the politically charged realm of governance.

3.3 Actor-driven factors

Based on the above discussions, this study argues that triggering mechanism theory incorporates focusing events as a driving force for policy agenda-setting into the research perspective. Attention theory complements the stage development theory and media policy agenda-setting theory, indicating that factors imbued with subjectivity can successfully drive the setting of social issues on the policy agenda. The multiple-stream framework refers to the factors that prompt the coupling of three streams in a chaotic and disorderly state, which can open policy windows. By integrating existing academic research achievements, this study summarises the conditions that need to be met for policy agenda-setting from different perspectives, absorbing the strengths of each theory to construct a framework of influencing factors for online focusing events to trigger policy agendas.

In policy agenda-setting, various stakeholders may participate actively or passively; however, this does not imply that they can directly shape policy agendas. The natural advantage of the governmental authority is that it consistently occupies a central decision-making position in policy agenda-setting.

Governments may influence agenda setting in several ways: on the one hand, they may proactively propose agendas and formulate policies based on their values and behavioural preferences, leaving no room for intervention by other stakeholders (Birkland, 2011); on the other hand, they may assess the need for public support and cooperation and decide whether persuasion of other stakeholders to accept and cooperate is necessary (Li, 2003). Moreover, governments may also be passively pressured by societal public opinion and collective events, necessitating responses to policy issues. However, even in such scenarios, governmental constraints greatly influence agenda-setting and policy content (Zhu and Xiao, 2012).

Additionally, expert scholars serve as pivotal intermediaries in the policy agenda-setting process. They form part of think tanks which identify and analyse societal issues, leveraging their research outcomes to provide policy recommendations. Subsequently, these recommendations influence the configuration of policy agendas within governmental realms. Conversely, intellectuals within the public domain undertake the role of opinion leaders, strategically directing public attention towards salient social issues. Through their influence, they amplify the significance of events and ensure the elevation of pertinent issues on the government’s radar, effectively manoeuvring societal concerns into the purview of government decision-makers. In addition, these intellectuals disseminate their envisaged policy remedies across public platforms, potentially propelling them into contention as viable policy alternatives.

Moreover, interest groups emanating from societal strata coalesce around shared policy values and objectives. Their modus operandi involves lobbying governmental entities to accord precedence to issues germane to their collective interests, along with advocating the adoption of policy proposals aligned with their agenda. Furthermore, they exert a counteractive influence on policy agenda-setting processes by obstructing governmental initiatives aimed at reforming or rescinding policies that adversely affect their interests. In interactions with governmental bodies, interest groups seek to establish direct channels with decision-makers, often resorting to bureaucratic channels of influence exchange. Concurrently, they harness the media to rally public support, manipulate public opinion in their favour, or obfuscate inconvenient truths.

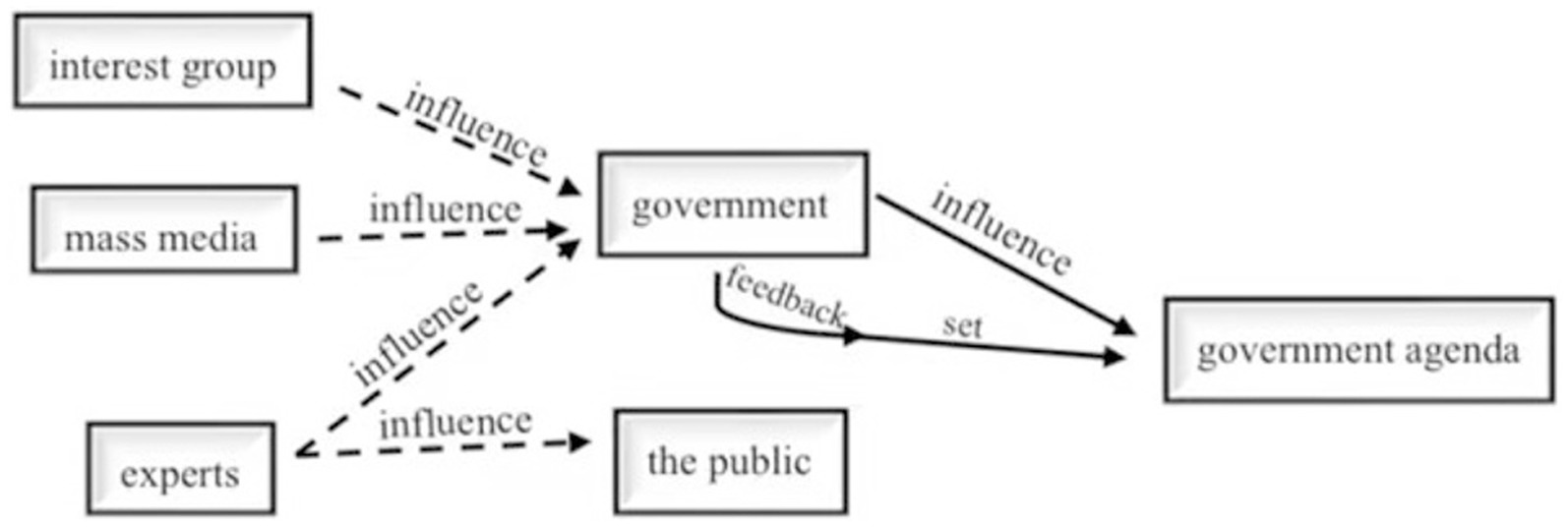

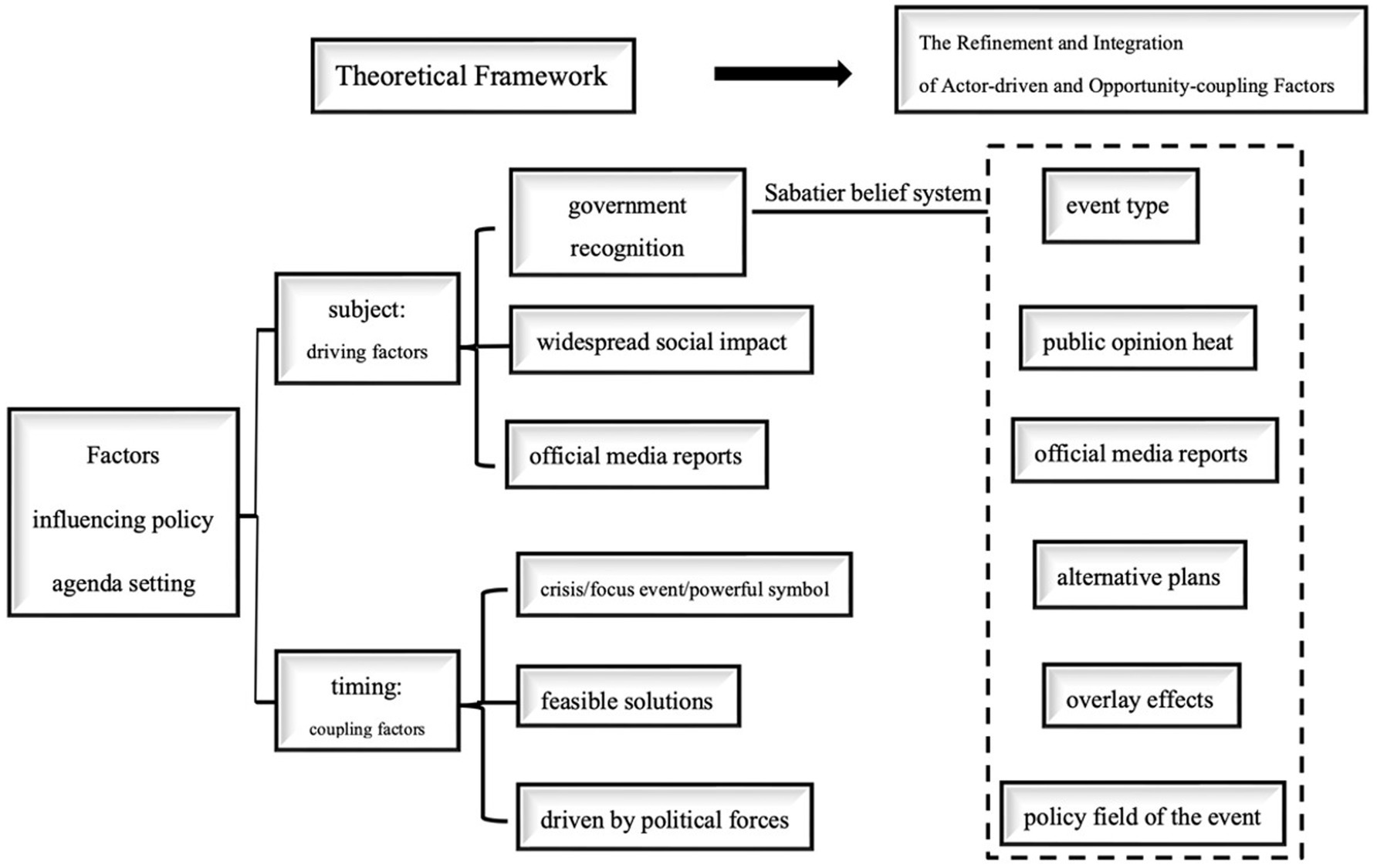

The proliferation of Internet technologies, coupled with heightened civic consciousness, has empowered the public to assert agency in both the selection of policy agendas and the shaping of policy-setting processes. Guided by personal interests, values, and affective responses, the public selectively incorporates societal issues into its systemic agenda, thereby articulating policy imperatives to government authorities. Instances where societal issues attain widespread discourse or precipitate collective mobilisation serve as pivotal junctures, wherein the systemic agenda converges closely with the policy agenda. The main driving factors of the government agenda are presented in Figure 1.

In summary, the government unequivocally assumes the mantle of the gatekeeper and adjudicator in the realm of policy agenda-setting. Concurrently, the public exerts palpable pressure on government authorities and wields substantive agency in the agenda-setting process. Official media, aligned closely with governmental narratives, serves as a primary conduit for agenda transmission, occupying a preeminent position within the media landscape. Collectively, these factors serve as drivers for the formulation and configuration of policy agendas.

3.4 Opportunity-coupling factors

A ‘policy window’ arises as social issues wait their turn to be addressed. In Kingdon’s multiple streams framework, the process of policy agenda-setting does not progress linearly as per stage models (Kingdon, 1984). Instead, a comprehensive linkage is envisaged comprising streams of problems, policies, and politics. Within the political system, there exists an array of issues, either acknowledged by the government, media, and public or neglected, constituting the ‘problem stream’.

First, changes in series indicators monitored by the government, political institutions, and non-governmental researchers and scholars, such as health, safety, and education, are deemed significant, as they signify alterations in the state of the system. Second, issues do not manifest solely because of the presence of indicators; they await the impetus of crises, potent symbols, or focusing events for emergence and dissemination. Third, if there are adverse feedback responses regarding the government’s current policy initiatives, known as negative ‘inputs’, new issues may arise unexpectedly (Kingdon, 1984).

Policy proposals and alternative solutions float within communities comprised of professionals, akin to molecules colliding or combining. Certain criteria act as meticulous filters, allowing only select ideas to persist in the ‘policy soup’, while others may survive and become policy proposals (Kingdon, 1984). The topics related to effective alternative solutions garnered heightened and sustained attention on the policy agenda.

Different political entities, such as citizens, governments, political parties, and interest groups, undergo changes that render new agendas significant and exert considerable influence on the policy agenda. Factors such as public sentiment, government turnover, competition among interest groups, and the ideological landscape of political parties are encompassed within the political stream (Kingdon, 1984).

In conclusion, these three streams, which involve a focus on issues by the government and surrounding actors, surviving alternative solutions, and the dynamics of various political forces, serve as aggregating factors poised for agenda-setting success.

3.5 The refinement and integration of actor-driven and opportunity-coupling factors

Building on the critical analysis of how authoritarian regimes strategically create participation, responsiveness, and visibility, this section incorporates actor-driven and opportunity-coupling mechanisms into a practical framework. These mechanisms operate within a media environment that is anything but neutral; they are closely intertwined with a digitally mediated political landscape where events of focus, public participation, and policy responsiveness are filtered and managed by the state. Thus, this framework seeks to elucidate not just who influences agenda-setting, but also how symbolic participation and media control shape the environment in which political agendas develop.

At the actor level, the process of policy agenda-setting is affected by whether societal issues gain acknowledgement from the government, spark public debate, and are disseminated via official media. However, in authoritarian regimes, each aspect is manipulated selectively. Public pressure might be accepted or suppressed; media reporting can either highlight or obscure issues; and government acknowledgement might mirror regime interests rather than public urgency.

This study utilises established agenda-setting theories, including Kingdon’s multiple streams framework and media-based agenda-building models, but does not consider them universally applicable. Instead, it critically adapts these theories to the Chinese context, where the Party-State’s ideological dominance, media centralisation, and dual-track responsiveness mechanisms significantly alter the landscape for policy agenda formation. This methodology aligns with recent research by Ma and Cao (2023), who contend that political participation in China often embodies a mixed pattern of mobilisation, control, and symbolic inclusion.

In this system, political participation is carefully managed, and institutional responsiveness tends to be more symbolic than substantive. Thus, instead of assuming that public attention or the severity of issues alone drives agenda-setting, this study develops a framework that incorporates media filtering, strategies for maintaining regime legitimacy, and authoritarian responsiveness as shared influences on policy attention. The configurational logic of Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) is well-equipped to capture these dynamics, as it embraces context-specific causal pathways instead of relying on linear, universally applicable effects.

In the time frame, crises, key events, and significant moments—like widespread online responses or recurring incidents—act as catalysts for agenda inclusion, especially when practical policy solutions are available. These catalysts are influenced by state dynamics; their prominence is frequently shaped by political considerations. By incorporating these actor-focused and temporal factors, the research outlines six clarified antecedent conditions that create the empirical foundation for the subsequent QCA.

These factors can be delineated to obtain measurable antecedent conditions, thereby laying the groundwork for an analysis of the determinants of policy agenda-setting.

The first factor involves the notion of government recognition, aimed at analysing which societal issues the government is more inclined to transform into policy problems or, conversely, which it might reject as policy concerns. This necessitates an understanding of the government’s policy values and behavioural preferences, which can be achieved through the framework of policy beliefs proposed by Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith (1993).

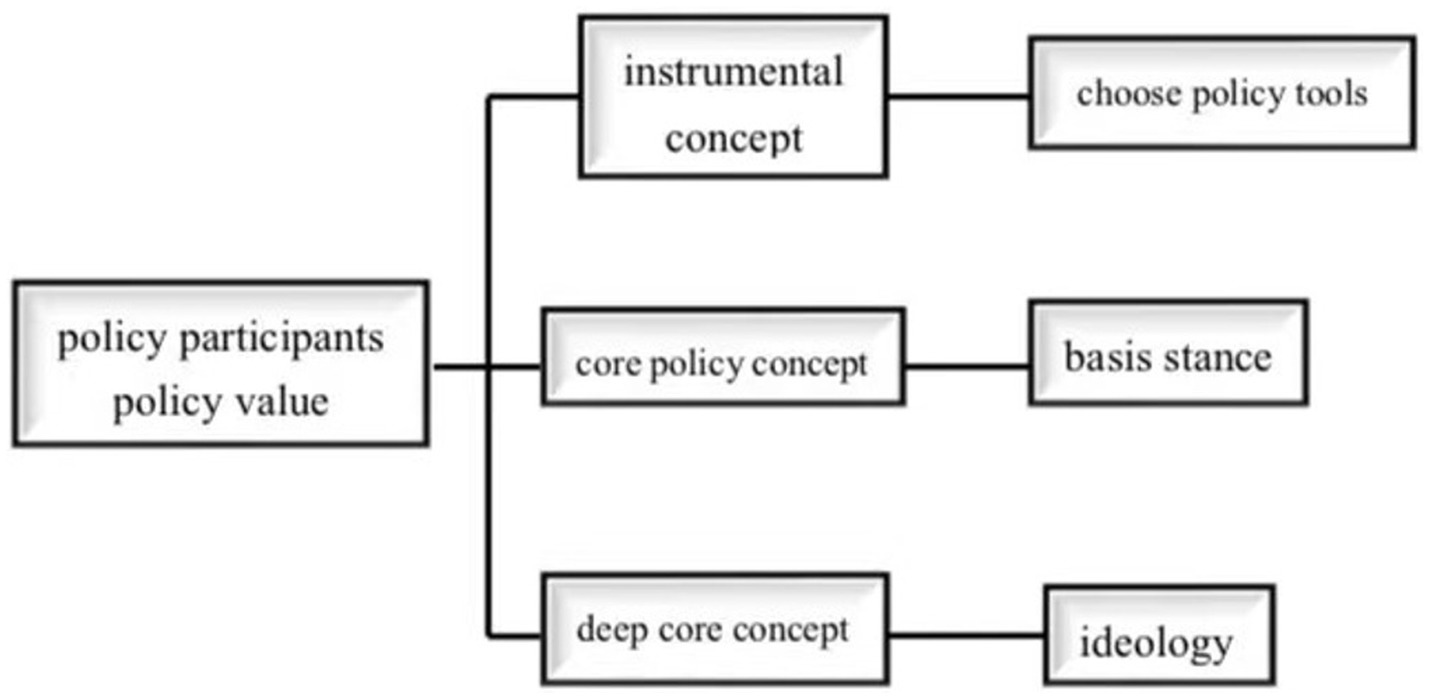

Policy beliefs are divided into three levels: the instrumental concept, the core policy concept, and the deep core concept (Figure 2). At the instrumental rationality level, policymakers’ selection of policy tools is primarily based on surface-level, tangible cognitions that are subject to change. This can be understood as the government being willing and having appropriate tools available when faced with a societal issue, thereby successfully setting the policy agenda. A further breakdown includes whether the problem falls within the government’s scope of responsibility and whether viable policy tools are available. For example, situations about personal ethics or cultural and entertainment events may not be suitable for government intervention and policy tools. Additionally, such events often lack consensus among the public and may even be contentious, making it difficult for the government to establish clear policy objectives. The availability of policy tools emphasises the operational feasibility of the problem; societal issues that the government has dealt with repeatedly and for which mature solutions exist are more likely to be prioritised for resolution (Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith, 1993). At the core policy concept level are the fundamental stances and strategies. This level combines additional values with instrumental rationality and encounters pressure groups that impede policy agenda-setting. When faced with societal issues, the government must gradually learn from policy experiences and engage in incremental policy learning until a balance of power is achieved (Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith, 1993). However, it is also possible for the government to procrastinate, allowing societal issues to gradually fade. The deep core beliefs level mainly refers to ideology (Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith, 1993), which dominates the entire belief system and is the most difficult to influence unless there is significant political upheaval or policymakers act with long-term considerations. If societal issues reflect abstract ideology-related demands, they are unlikely to be placed on policy agendas.

The second driving and coupling factor includes how societal issues exert widespread influence on the public. This is indicated by the public’s ‘speech’ and ‘action’, whether through triggering collective events or generating high levels of public discourse. Under the imperative of constructing a responsive government, societal issues must be swiftly placed on the agenda, which sometimes overshadows their inherent severity.

Third, coverage by official media outlets, such as the People’s Daily, Xinhua News Agency, China Youth Daily, and Guangming Daily, plays a pivotal role. These outlets not only disseminate information but also fulfil political functions, such as propagating ideology, conveying government stances, and promoting public policies, thereby exerting authoritative influence on the public. If a societal issue is incorporated into an official media agenda, the process of policy agenda-setting accelerates significantly.

Fourth, crises, focusing events, and potent symbols serve to highlight societal issues and intensify public perception. Moreover, they require other elements to act as ‘accompaniment’. For instance, in the case of a crisis, merely its occurrence is insufficient to alter the status quo of the issue definition by various stakeholders; the ubiquity of the issue requires a deeper impact to ‘sound the alarm’ once again. Similarly, other events that resemble the focusing events can reinforce their effects.

Fifth, feasible solutions are crucial. The criteria for retaining solutions are inherent within the policy community, including factors such as the feasibility of implementation; the practical mechanisms for application, also known as ‘technical feasibility’; alignment with principles of fairness and efficiency as demanded by professionals; and adherence to constraints such as public acceptance and budgetary limitations.

Finally, political forces also play a significant role in policy agenda-setting. Changes in policy agendas can be attributed to static entities, such as the public, government, pressure groups, or other alliance-like entities, and dynamic functions within the government, such as leadership turnovers and shifts in the political landscape of parties (Kingdon, 1984). These factors create a new political ecosystem in which previously impossible scenarios become feasible and other aspects become contingent. Certain ideologies may be accepted, while others may not.

Given the overlap between the refined driving and coupling factors, this study embeds the context of online focusing events within the framework of policy agenda-setting and conducts comparisons. Subsequently, it further refines possible indicators that may influence policy agenda-setting as presented in Figure 3. Therefore, the actor-driven and opportunity-coupling factors are refined and integrated into the following:

1) Public opinion heat serves as evidence of online focusing events’ ability to attract attention. This correlates with the driving factor of ‘widespread influence on the public’ and aligns synonymously with coupling factors such as ‘focusing events/crises/potent symbols’. It is also intertwined with political forces, such as national sentiment and pressure groups.

2) Event type, whether regarding disasters, the social rule of law, cultural and entertainment issues, emotional and moral issues, or political issues involving ideology, is derived from the perspective of government recognition. At the instrumental rationality level, event type indicates the government’s inclination to address societal problems that it should solve, while at the deep-core belief level, it suggests the government’s reluctance to address politically sensitive issues that affect its legitimacy. The policy core belief level, which is more complex and involves resistance from pressure groups, is not included within the standard range.

3) Official media reports align with the positioning of the media as a significant factor in policy agenda-setting, considering the rapid growth of online social platforms and self-media. This context underscores the media’s proactive role in brewing focusing events, shaping agendas, and highlighting the symbiotic relationship between authoritative state media and the government.

4) Alternative plans, as per the instrumental rationality level of the driving factor ‘government recognition’, imply that the government prioritises societal issues it can address effectively. Clear solutions help to clarify policy objectives and facilitate policy implementation. The coupling factor, ‘feasible solutions’, in policy discourse also indicates that if a problem has viable solutions attached, it is more likely to be included in the government’s policy agenda.

5) Overlay effects underscore the severity of a problem. While a single event may not adequately convey the urgency of an issue, a series of closely occurring events can raise awareness of a widespread and pressing problem requiring resolution.

6) The policy field of the event, specifically, whether there are policy gaps or deficiencies related to online focusing events, is crucial. If an issue emerges or falls within the public domain but lacks government policy, it garners greater public demand and highlights unresolved societal problems, making it more likely to attract government attention and expedite efforts to establish a comprehensive policy framework.

Figure 3. Analysis framework of influencing factors of policy agenda setting (this figure is created by the authors).

4 Research method and process

The analytical framework constructed above reveals that multiple factors, including public opinion heat, event type, official media reports, alternative plans, overlay effects, and the policy field of the event, may influence the setting of policy agendas, either individually or in combination. Quantitative analysis methods aim to explain the strength of the correlation between different causal conditions and the outcome condition within linear causal relationships; therefore, they cannot discern the significance of each factor’s impact on the outcome or the pathways through which they are effective. This study adopts the Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) method, pioneered by Charles Ragin et al. in the 1980s, as a new approach beyond quantitative and qualitative research (Rihoux and Larkin, 2019).

4.1 Qualitative comparative analysis

QCA presents a groundbreaking methodology that transcends the traditional boundaries of qualitative and quantitative research. Unlike conventional approaches that emphasise linear causality and isolate the effects of individual conditions, QCA is based on the principle of complex causality. It explores how multiple conditions interact in a nonlinear manner to produce outcomes, emphasising the configurations of conditions that lead to particular results (Ragin, 1987). This methodological innovation is particularly adept at identifying both necessary and sufficient conditions for an outcome, thus providing a refined understanding of causality that is often missed by other methods. The adaptability of QCA to handle both crisp and fuzzy datasets further enhances its utility, allowing researchers to analyse data with varying levels of precision and account for degrees of membership in conditions (Rihoux and Ragin, 2009).

The selection of crisp-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (csQCA) for this research stems from its distinctive ability to manage data characterised by clear, binary distinctions in conditions and outcomes, facilitating a precise examination of causal relationships within complex phenomena. CsQCA is particularly suited for studies in which the conditions and outcomes can be unambiguously categorised as present or absent, thereby providing a rigorous framework for identifying the necessary and sufficient conditions that influence the phenomenon under investigation. This binary approach simplifies the complex interplay of multiple factors, making it possible to discern the distinct patterns and configurations that lead to specific outcomes (Ragin, 2000).

In the context of policy agenda-setting, csQCA enables the researcher to operationalise conditions in a binary fashion, such as the presence or absence of significant media coverage, public opinion heat, or specific event types. This clarity is crucial for analysing how various combinations of these conditions contribute to or deter the inclusion of issues on the policy agenda. Moreover, the focus of csQCA on binary data does not preclude the examination of complex causal relationships; rather, it offers a structured method for navigating the intricacies of these relationships by systematically comparing cases to identify causation patterns (Ragin, 2000; Rihoux and Ragin, 2009).

The adoption of csQCA in this study is justified by its capacity to provide clear and interpretable results that reveal the causal mechanisms underpinning policy agenda-setting. By identifying necessary and sufficient conditions, csQCA facilitates a new understanding of how different factors interlock to shape policy outcomes.

While the adoption of crisp-set QCA provides strong explanatory clarity, it is acknowledged that dichotomisation can sometimes risk oversimplifying gradient phenomena. In this study, fuzzy-set calibration was considered but ultimately deemed inappropriate due to both theoretical and empirical constraints. Conceptually, the outcome under investigation—whether an online focusing event results in policy agenda-setting—is a threshold phenomenon in the Chinese political context. Either an issue is formally addressed by the state, or it is not. This institutional binary logic also applies to many causal conditions—such as whether an event was reported by top-level government media, or whether systematic alternative proposals were made—which function as categorical triggers rather than continuous spectra.

Empirically, conditions such as the Baidu Index exhibit highly uneven distributions, strongly dependent on media amplification and event characteristics. Applying fuzzy calibration to such skewed and discontinuous data would introduce artificial precision and compromise interpretability. Therefore, this study adopts a dichotomous threshold of 10,000 in the 10-day post-event average to identify ‘high public opinion heat,’ based on empirical inflection points identified in previous studies (Huang et al., 2019). Other conditions—including media coverage, policy field classification, and alternative proposals—are intrinsically binary within the institutional discourse, and are more appropriately treated as crisp sets.

To reinforce the validity of these calibration decisions, the study conducted three rounds of robustness testing. These included raising the consistency threshold from 0.8 to 0.9, adjusting the PRI consistency threshold from 0.75 to 0.8, and increasing the frequency threshold from 1 to 2. Across all scenarios, the principal causal configurations remained stable, demonstrating the empirical robustness of the csQCA results.

Furthermore, the dichotomous structure of both the outcome and the causal conditions aligns with the institutional reality of China’s policymaking system. Whether a policy agenda is initiated or not is a matter of formal state action, not degrees of attention. Similarly, many conditions—such as official recognition, inclusion in the media agenda, or relevance to a policy field—are filtered through non-transparent decision-making logics. These reflect what can be described as a ‘black box’ of authoritarian governance, where thresholds are abrupt, and intermediate values are politically inaccessible or methodologically unobservable.

Therefore, although csQCA sacrifices some granularity compared to fsQCA, it remains both conceptually appropriate and empirically rigorous for investigating policy agenda-setting under authoritarian governance.

4.2 Data

In selecting cases for analysis, this study principally relies on eight volumes of the ‘China Social Public Opinion Blue Book Series’, titled ‘China Social Public Opinion Annual Report’, published by the People’s Daily Press between 2011 and 2020. A total of 110 cases were obtained. From 2011–2020, the China Social Public Opinion Annual Report listed 20 major online focusing events each year. However, in 2020, due to the outbreak of COVID-19, all 20 events were related to the COVID-19 pandemic, making it difficult to distinguish which specific policies triggered the related incidents. As a result, the focusing events of 2020 were integrated with those of 2019, with one of the key online focusing events in 2019 being the outbreak of COVID-19. Ultimately, a total of 110 focusing events were identified. Additionally, following the requirements for case selection outlined by QCA, the selection must satisfy the following criteria:

First, the number of cases must be appropriate. Unlike quantitative and qualitative research, QCA adopts a meso-level approach and recommends an optimal range of 10–60 cases (Rihoux and Ragin, 2009). Second, the classic representativeness of cases is essential. The cases should be widely recognised as having a significant influence. Third, there must be diversity in the case types. This implies that the characteristics and nature of each case should be heterogeneous. Fourth, regarding the availability of materials, a rich source of information must support case investigation. Finally, certainty of the outcome is required, implying that the outcomes of the cases can be qualitatively assessed and remain unchanged (Ragin, 1987).

In the final selection of cases, it is crucial to ensure both practical relevance and theoretical robustness. The most effective method to achieve this balance is expert scoring, which involves gathering assessments from suitable experts. This method leverages individuals’ expertise and experience to evaluate cases based on predefined criteria, thereby ensuring a high level of reliability and validity in the selection process (Eisenhardt, 1989; Yin, 2017).

However, because of the difficulty in accessing a sufficient number of experts for this study, it was not feasible to implement the expert scoring method directly. As an alternative, this study employed the method of cross-referencing selected cases with those chosen from related studies published in CSSCI and SSCI journals over the past 5 years. This approach is grounded in the idea that peer-reviewed publications undergo rigorous scrutiny to ensure that selected cases are thoroughly vetted by the academic community. By aligning these cases with those documented in the established academic literature, this article aims to capture the consensus of scholarly judgment and maintain a high standard of academic rigour.

Peer-reviewed articles in reputable journals are subjected to extensive review processes involving multiple experts in the field. These experts evaluate the relevance, significance, and methodological soundness of the research, including the choice of the case (Levy and Ellis, 2006; Webster and Watson, 2002). Therefore, by cross-referencing the cases selected for this research with those selected in these articles, this study indirectly leverages the expertise and judgment of the reviewers. This method ensures that the case selection is both credible and methodologically sound, effectively addressing the QCA criteria.

By incorporating cases highlighted in CSSCI and SSCI journals (Guo et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2019; Wang and Wu, 2019; Wu and Wang, 2021), this study ensures that case selection reflects the most relevant and impactful cases studied in recent years. All the selected cases are listed in Table 1.

4.3 Key hypotheses and coding scheme

Within the context of this study’s aim to uncover the configurational conditions that facilitate the setting of policy agendas in response to online focusing events, six hypotheses were developed based on the proposed theoretical framework. These hypotheses explore the interplay between a range of factors, including public opinion heat, event type, official media reporting, alternative proposals, the overlay effect, and the policy field of the event, to understand their collective or individual influence on the policy-making process.

4.3.1 Hypothesis 1

Events that generate high public opinion heat, as indicated by a Baidu Index exceeding 10,000 within 10 days of their occurrence (Huang et al., 2019), are more likely to lead to policy agenda-setting, especially when combined with official media reporting. This hypothesis draws on the premise that heightened public attention validated by government media acknowledgement creates a conducive environment for policy consideration (Huang et al., 2019).

4.3.2 Hypothesis 2

Focusing events for which the public, media, or experts have proposed systematic policy suggestions, are more likely to result in policy agenda-setting. This hypothesis underlines the significance of constructive and actionable feedback in steering policy considerations, suggesting that alternative proposals can catalyse policy evaluation and change (Wu and Wang, 2021).

4.3.3 Hypothesis 3

Events occurring within a context in which similar events have been previously recorded are more likely to lead to policy agenda-setting. This hypothesis assumes that a history of similar events accentuates the need for policy intervention, highlighting the importance of historical context in policy decision-making processes.

4.3.4 Hypothesis 4

Events reported or commented upon by top-level government media outlets which mention policy introductions, amendments, or abolitions are more likely to be followed by policy agenda-setting. This hypothesis posits that official media reporting not only signals government attention but also potentially frames policy discourse, influencing policy direction.

4.3.5 Hypothesis 5

Disaster accidents, ideological-political issues, and socio-legal events are more likely to trigger policy agenda-setting than cultural entertainment or moral-emotional events. This hypothesis suggests that the nature of an event significantly influences the likelihood of a policy response, with critical events prompting immediate action.

4.3.6 Hypothesis 6

Events occurring in fields where policies have already been introduced are more likely to influence policy agenda-setting. This hypothesis suggests that the existence of precedent policies provides a foundation upon which further policy deliberations and modifications can be more easily based, indicating that the policy field plays a crucial role in determining the susceptibility of policy agendas to new influences.

Based on the above hypotheses, a coding scheme is developed for both causal and outcome conditions to facilitate the analysis using QCA. For the causal conditions, coding was based on the following dimensions:

4.3.7 Public opinion heat (14 cases)

This study utilised the ‘Baidu Index’, which reflects the allocation of public attention to social issues over a certain period and search behaviour, as a measure (Huang et al., 2019). Specifically, research indicates that approximately 10 days after the onset of internet public opinion, it enters a period of rising heat and reaches a peak. Therefore, in this study, if the average Baidu Index within 10 days after the emergence of an Internet-focusing event remained above 10,000, it was coded as 1, indicating high public opinion heat; otherwise, it was coded as 0.

4.3.8 Alternative proposals (18 cases)

Focusing events for which the public, media, or experts have proposed systematic policy suggestions were coded as 1; otherwise, they were coded as 0.

4.3.9 Overlay effect (19 cases)

This study coded an event as 1 if, in the year b before the event, similar types of events were recorded rather than isolated or sporadic cases; otherwise, events were coded as 0.

4.3.10 Official media reporting (26 cases)

Events reported or commented on by top-level government media outlets, including People’s Daily, Xinhua News Agency, and CCTV (referred to as the ‘three central mouthpieces’), especially those mentioning policy introductions, amendments, or abolitions, were coded as 1; otherwise, they were coded as 0.

4.3.11 Event type (31 cases)

Disaster accidents and socio-legal events were coded as 1, while cultural entertainment, moral-emotional, and ideological political issue events were coded as 0.

4.3.12 Policy field of the event (16 cases)

If there were already policies introduced in the type or field to which an Internet focusing event belongs, it was coded as 1; otherwise, it was coded as 0.

4.3.13 Policy agenda setting outcome

For the outcome condition:

Online focusing events that triggered policy agenda-setting, manifested as policy modification, introduction, or abolition, were coded as 1; otherwise, they were coded as 0.

5 Results

5.1 Truth table and logical diversity

The analysis generated a truth table comprising all 64 logically possible configurations derived from six dichotomous causal conditions. Among these, 23 configurations were empirically observed in the dataset, while the remaining 41 represent logical remainders—that is, configurations that are theoretically possible but unobserved in the data. This asymmetry reflects the well-documented problem of limited diversity inherent in small-and medium-N QCA designs (Ragin, 2000).

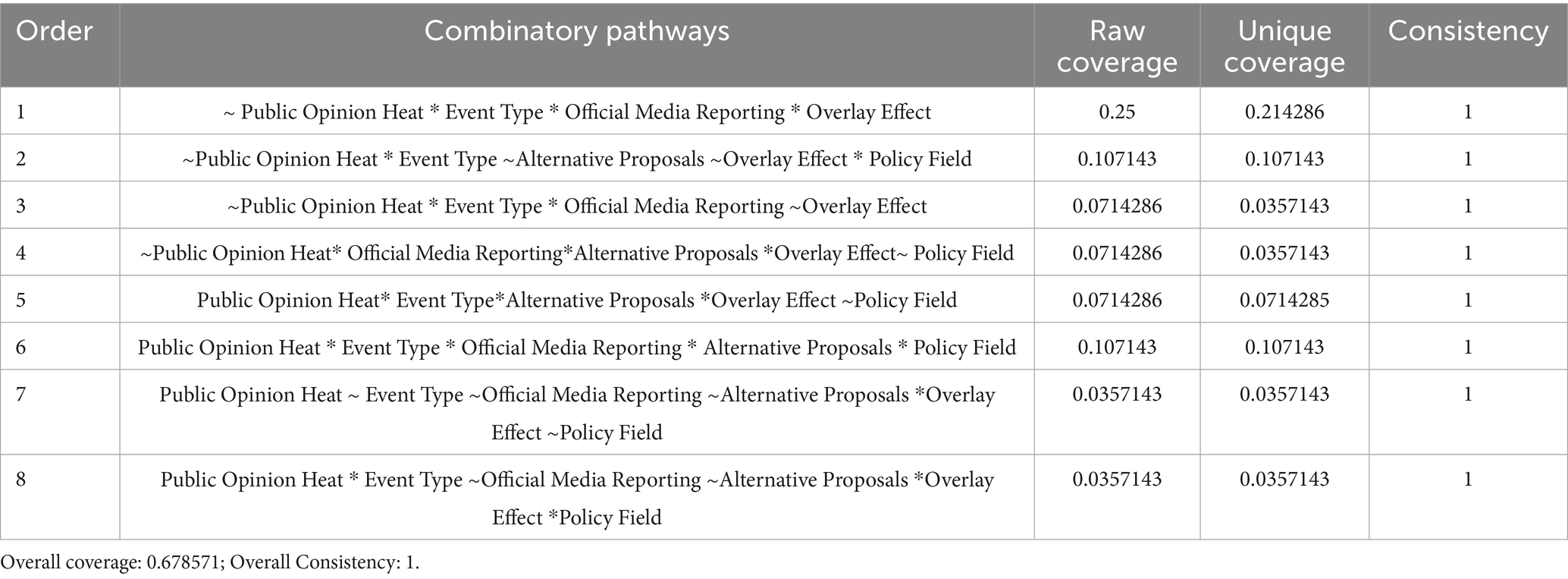

This analysis employs the intermediate solution in crisp-set QCA (csQCA). Unlike the parsimonious solution, which oversimplifies conditions and can obscure important theoretical nuances, or the complex solution, which complicates interpretation, the intermediate solution strikes an optimal balance by integrating theoretically informed assumptions about logical remainders. It allows careful inclusion of conditions based on established theoretical insights, thereby clearly distinguishing core from peripheral causal conditions (Ragin, 2008). Thus, while the truth table identifies 23 observed empirical configurations, the intermediate solution consolidates these into eight distinct causal pathways. This reduction reflects theoretical coherence and empirical clarity, facilitating nuanced interpretation of authoritarian policy agenda-setting, institutional responsiveness, and symbolic governance boundaries.

To ensure full transparency, Appendix 1: Truth Table presents the complete set of configurations, clearly identifying observed cases and logical remainders. Each configuration is accompanied by its condition values, outcome (OUT), consistency, PRI score, number of cases, and case identifiers. Logical remainders are marked accordingly.

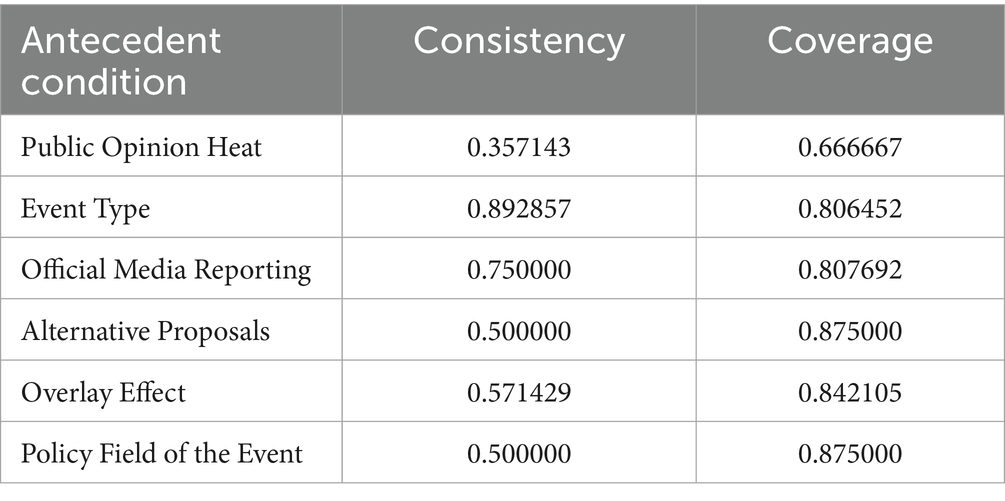

Among the 41 logical remainders, configurations 49 through 61 warrant specific attention due to their plausible alignment with agenda-setting triggers, particularly the co-presence of high public opinion heat and salient event types. These configurations are included in the intermediate solution and will be further addressed in Chapter 6. No single condition exhibits consistency above 0.9, indicating the absence of any necessary conditions for triggering policy agenda-setting. Only the consistency of the event type with policy agenda-setting exceeds 0.8, making it a sufficient condition for setting the policy agenda. This suggests that disaster incidents and social-legal events focused on the social-legal system are sufficient conditions for opening policy windows. The consistency of the other conditions falls below 0.8, indicating that they can, in combination but not independently, belong to the category of multiple concurrent causal relationships that influence the policy agenda-setting outcomes of online focusing events.

5.2 Necessity analysis

The necessity analysis was conducted to assess whether any single causal condition was individually required for policy agenda-setting to occur. The analysis applied the standard consistency threshold of 0.90 to identify necessary conditions. As shown in Table 2, none of the six antecedent conditions met the threshold, indicating that no single condition was strictly necessary for the outcome. However, ‘Event Type’ approached the consistency threshold (0.8929), suggesting that it may function as a quasi-necessary condition, meriting further theoretical attention.

5.3 Sufficiency analysis and configurational results

Sufficiency analysis identified eight causal pathways associated with successful policy agenda-setting. Each pathway constitutes a distinct configuration of conditions that is consistently linked to the outcome. All eight pathways exhibit perfect consistency (1.00), indicating that whenever a configuration was observed, the outcome also occurred.

Table 3 presents the eight sufficient configurations, along with their raw and unique coverage scores and consistency values. Pathways 1, 2, and 6 demonstrated the highest empirical relevance, with comparatively higher unique coverage. Pathway 5, though more limited in coverage, is retained due to its stable explanatory role. Pathways 3, 4, 7, and 8 displayed minimal unique coverage (<0.04), yet are included to reflect the full diversity of the solution space.

No contradictory configurations were found in the truth table. Each observed configuration yielded consistent outcomes, with all configurations linked to policy agenda-setting (OUT = 1) meeting the consistency threshold of 1.00. The presence of eight sufficient paths with full consistency supports the explanatory power of the identified configurations. However, the relatively low unique coverage of paths 3, 4, 7, and 8 (<0.04) indicates that these combinations capture fewer unique cases and contribute marginally to the overall explanatory structure. These configurations are retained in the solution for completeness and will be further discussed in Chapter 6.

5.4 Robustness and contradiction assessment

To assess the stability of the findings, three sets of robustness checks were conducted, adjusting key analytical thresholds commonly used in csQCA:

1. Consistency Threshold Test: The minimum sufficiency threshold was raised from 0.80 to 0.90. All key pathways (especially 1, 2, 5, and 6) remained consistent and present in the solution (Please see Appendix 2: Robustness Check – Consistency Adjustment).

2. PRI (Proportional Reduction in Inconsistency) Threshold Test: The PRI threshold was increased from 0.75 to 0.80. The solution remained stable, with no change in pathway inclusion (Please see Appendix 3: Robustness Check –PRI Adjustment).

Across all three robustness tests, the core solution set remained unchanged, suggesting that the findings are not sensitive to minor calibrational variations. This robustness affirms the internal validity of the model and enhances confidence in the sufficiency of the configurations.

Additionally, a contradiction check was performed on the full truth table. No contradictory rows were found—that is, no configuration yielded both the presence and absence of the outcome. This confirms the logical coherence of the model and the internal consistency of the observed data.

The results above offer a clear account of the condition combinations that are sufficient for policy agenda-setting in the Chinese context. Eight distinct pathways were identified, all with perfect consistency, though their empirical contributions vary significantly. Core pathways with higher coverage (1, 2, and 6) account for the bulk of the explained outcome, while other configurations represent peripheral or rare combinations.

These results demonstrate the configurational complexity of responsiveness under authoritarian rule, where multiple causal routes coexist. The interpretive implications of these configurations—including their relation to symbolic participation, regime legitimacy, and strategic responsiveness—are explored in detail in Chapter 6.

6 Discussion

The previous chapter highlights the complexity of authoritarian responsiveness and the mechanisms through which policy agendas are set or avoided in contemporary China. While research on authoritarian governance emphasises centralisation, responsiveness, and symbolic participation (He and Warren, 2011; Nathan, 2003), few studies explore how media coverage, public opinion, event types, and institutional boundaries shape policy agendas. Using Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA), this study identifies multiple pathways, illustrating both mechanisms of state responsiveness and instances of institutional silence.

This chapter will analyse each configuration to clarify theoretical implications from the empirical findings. Paths showing structured institutional responsiveness (paths 1, 2, 5, and 6) will be discussed first, focusing on how media framing, public opinion salience, and institutional settings create coherent policy responses.

Additionally, pathways with low coverage but high theoretical significance (paths 3, 4, 7, and 8) will be explored through illustrative cases, including the Fudan University poisoning, Zhengning school bus accident, high-speed rail ‘seat occupancy’ controversy, and Zhongguancun school bullying incident. These cases reveal the limits of institutional responsiveness under specific conditions.

Lastly, logical remainders (configurations 49–61), which involve events with high theoretical potential yet missing from the policy agenda, will be discussed. These configurations reveal deliberate governmental silences, indicating selective institutional responsiveness in sensitive areas (e.g., ideology, morality, entertainment). This section will incorporate theories from Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith’s (1993) belief systems approach, demonstrating how governments delineate policy arenas to reflect ideological boundaries and reinforce legitimacy.

Overall, this interpretative discussion aims to contribute significantly to the theoretical literature on authoritarian responsiveness, symbolic governance, and agenda-setting in non-democratic contexts, offering insights into the dynamics sustaining contemporary authoritarian governance.

6.1 Main pathways: institutionalised responsiveness (paths 1, 2, 5, and 6)

6.1.1 Pathway 1: structured institutional responsiveness (~public opinion heat * event type * official media reporting * overlay effect)

Pathway 1 illustrates a strong institutional logic guiding policy agenda-setting regardless of public opinion pressures. This setup highlights socio-legal or disaster events noted by official media, alongside clear or implied policy proposals. The government’s proactive response shows that its internal policy priorities and institutional responsibilities often take precedence over public mobilisation, revealing its deep-seated instrumental rationality (Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith, 1993).

The Jiangxi proxy examination and sexual harassment cases involving a Changjiang Scholar illustrate this institutional dynamic. Initially, these events lacked public consensus and online mobilisation, but repeated official media coverage and alignment with government responsibilities elevated these issues to policy agendas. This suggests that when an event aligns with the government’s institutional framework, especially those affecting social order or educational integrity, official media acts as an amplifier of government interests, making intense public advocacy unnecessary.

Importantly, this pathway reveals the state’s power in strategically framing issues. The repetitive coverage (‘Overlay Effect’) does not merely inform the public; rather, it signals governmental acknowledgment and urgency, shaping public perception of issue importance and legitimacy. By proactively responding to institutionally recognised and media-highlighted events, the government demonstrates its responsiveness while simultaneously reinforcing its legitimacy and authoritative control over agenda-setting. Consequently, events captured by Pathway 1 illuminate the carefully orchestrated nature of authoritarian responsiveness, in which policy attention derives primarily from institutionalised logic rather than direct popular demand.

6.1.2 Pathway 2: proactive institutional response in policy vacuums (~public opinion heat * event type * policy field * ~ alternative proposals * ~ overlay effect)

Pathway 2 represents another distinctive facet of institutional responsiveness, capturing scenarios where socio-legal or disaster-related events, despite limited public engagement, compel governmental policy intervention due to evident gaps or vacuums in existing policy frameworks. Crucially, these are isolated, non-repetitive events with minimal public attention or pre-existing solution consensus, yet they clearly fall within the government’s policy field.

The Eastern Star cruise ship disaster and the Fan Bingbing tax evasion scandal exemplify this pattern vividly. Despite their relatively isolated occurrence and limited long-term media persistence, their immediate policy implications were significant enough to demand swift governmental action. Such responsiveness emerges not from extensive public mobilisation, but from the government’s strategic imperative to address and fill policy voids swiftly, avoiding potential accusations of negligence or incompetence. Here, ‘Event Type’ again emerges as critical, explicitly indicating issues within clear institutional responsibility. The policy vacuum itself motivates governmental responsiveness, demonstrating proactiveness and authority expansion even absent public pressure.

Thus, Pathway 2 highlights governmental strategic selectivity in addressing emergent institutional problems. Through prompt policy initiation in policy void areas, the government not only reasserts its control but also strategically mitigates potential legitimacy crises by addressing institutional gaps before they become politically contentious. Therefore, this pathway epitomises the nuanced, preventive dimension of authoritarian responsiveness—policy action driven by institutional necessity rather than popular demand, carefully maintaining and reinforcing regime legitimacy and effectiveness.

6.1.3 Pathway 5: institutional adaptation and policy innovation (public opinion heat * event type * alternative proposals * overlay effect * ~ policy field)

Pathway 5 highlights how strong public opinion, recurrent socio-legal or disaster-related events, and feasible alternative proposals collectively drive policy agenda-setting within previously undefined policy spaces. Here, the authoritarian regime demonstrates resilience through adaptive institutional responses, rather than symbolic avoidance, and extends state responsiveness beyond established policy frameworks (Nathan, 2003).

The Hongmao Medicinal Liquor incident vividly exemplifies this adaptive responsiveness. Initially falling outside existing regulatory frameworks, the event generated repeated public outrage and demands for clearer regulatory standards regarding medical misinformation and police authority misuse. Recognising both the public urgency and legitimacy threat, authorities responded substantively, initiating specific policy actions such as clearer standards for advertising medical products and stricter oversight mechanisms for police authority. This institutional adaptation, driven by public pressures and feasible alternatives, underscored the regime’s flexible capacity for policy innovation and responsiveness.

From the perspective of authoritarian resilience, this configuration demonstrates a regime’s strategic ability to respond adaptively to emergent challenges by selectively integrating societal demands into new policy areas. Rather than remaining rigid, the government tactically expands its institutional reach, thereby alleviating legitimacy pressures while reinforcing governance control (He and Warren, 2011). This adaptive mechanism thus contributes significantly to authoritarian resilience by enhancing institutional flexibility and demonstrating responsive governance capacities, effectively balancing societal pressures with regime stability.

6.1.4 Pathway 6: comprehensive institutionalised responsiveness (public opinion heat * event type * official media reporting * alternative proposals * policy field)

Pathway 6 reflects the most comprehensive institutionalised responsiveness pattern, in which high public opinion, official media framing, policy suggestions, and a clear institutional policy domain collectively align to trigger prompt policy agenda-setting. The configuration exemplifies highly structured, collaborative governance logic where public attention, media discourse, and governmental initiatives intersect to address critical social issues effectively.

The Husi expired meat scandal vividly exemplifies this comprehensive institutional alignment. Initial public outrage generated intense societal debate and mobilised collective concern. Official media coverage further amplified public dissatisfaction, creating consensus around clear policy solutions and demanding regulatory oversight. The government, recognising the legitimacy and institutional clarity surrounding food safety, quickly initiated formal policy responses. Here, the synergy of public pressure, media amplification, feasible solutions, and clearly defined institutional responsibilities created ideal conditions for immediate policy adoption, underscoring the alignment between public interests and institutional priorities.

This pathway embodies a form of authoritarian responsiveness resembling certain democratic governance features—specifically, collective problem definition and responsiveness shaped by public discourse and media mobilisation. While still fundamentally authoritarian, the mechanism reveals the state’s strategic use of public and media input to legitimise policy actions. By selectively responding to highly salient public concerns within clearly defined institutional frameworks, the government effectively harnesses societal legitimacy, deflecting criticism and reinforcing authoritative governance. Thus, Pathway 6 illustrates an evolved governance strategy within authoritarian contexts—one that incorporates limited participatory and democratic elements to sustain legitimacy and policy efficacy.

Integrating these pathways enhances our understanding of authoritarian governance by highlighting the mechanisms underpinning authoritarian resilience. Firstly, institutions strategically frame public perceptions and media discourse in line with internal belief systems (Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith, 1993), enabling regimes to maintain stability through controlled responsiveness. Secondly, although intense public opinion pressure is significant, its impact depends crucially on institutional alignment—clear event categorisation, official media support, feasible policy alternatives, and clearly defined policy fields.

The inclusion of Pathway 5 explicitly underscores regimes’ capacity for adaptive institutional innovation, a cornerstone of authoritarian resilience (Nathan, 2003). By selectively responding and extending institutional frameworks to manage emergent legitimacy pressures, authoritarian governments demonstrate flexibility critical to regime durability. Collectively, these pathways empirically illustrate responsive authoritarianism (He and Warren, 2011), reinforcing the view that governmental responsiveness is strategically selective, adaptive, and designed primarily to sustain regime stability and legitimacy.

Thus, authoritarian resilience is achieved through a sophisticated balance of institutional logic, selective media framing, strategic responsiveness, and adaptive policy innovation. This multifaceted responsiveness allows the regime to mitigate legitimacy threats, absorb societal pressures, and reinforce its authoritative governance, thereby illuminating the nuanced complexity underlying authoritarian agenda-setting processes.

6.2 Marginal pathways: boundary conditions of institutional responsiveness (paths 3, 4, 7, and 8)

Despite limited empirical coverage (<0.04), pathways 3, 4, 7, and 8 remain theoretically important, precisely because they represent exceptional yet successful instances of policy agenda-setting. These marginal pathways illuminate crucial boundary conditions under which authoritarian institutions selectively initiate policy responses, thereby enriching theoretical understandings of institutional responsiveness and authoritarian resilience (Nathan, 2003; He and Warren, 2011).

Pathway 3 (~Public Opinion Heat * Event Type * Official Media Reporting * ~ Overlay Effect), exemplified by the Fudan University poisoning incident, demonstrates that even singular socio-legal events clearly defined and institutionally endorsed through authoritative media can trigger immediate policy responses without sustained repetition. Its low coverage signals that sustained media repetition typically reinforces institutional responsiveness, yet this pathway highlights instances where the institutional significance and event clarity alone suffice to trigger decisive policy intervention.

Pathway 4 (~Public Opinion Heat * Official Media Reporting * Alternative Proposals * Overlay Effect * ~ Policy Field), illustrated by the Zhengning school bus accident, underscores governmental initiative in filling clear institutional voids through responsive policymaking, even absent significant public mobilisation. Its marginal occurrence reflects the unusual conditions where government proactively sets the agenda driven by internal policy needs and symbolic legitimacy considerations, rather than reactive public pressures. Thus, this pathway enhances our understanding of proactive institutional policy initiation.

Pathway 7 (Public Opinion Heat * ~ Event Type * ~ Official Media Reporting * ~ Alternative Proposals * Overlay Effect * ~ Policy Field), exemplified by the high-speed rail ‘seat occupancy’ controversy, captures rare instances where intense, sustained public outrage alone, despite lacking clear institutional categorisation or media endorsement, nevertheless pushes governmental institutions into symbolic but formal policy response. Its marginal occurrence illustrates how significant emotional mobilisation, though typically insufficient, can occasionally compel limited institutional adjustments, reflecting the adaptive capacity integral to authoritarian resilience.