- Department of Global Inquiry, School of International Service, American University, Washington, DC, United States

Right-wing populism poses a persistent threat to democratic governance in Central and Eastern Europe, sparking widespread anti-populist mobilization across the region. This study examines why some anti-populist social movements in the Visegrád Four succeed electorally while others do not, using process tracing to analyze variation across comparable political and historical contexts. It identifies three recurring features among the successful cases: sustained mobilization, inclusive framing, and operation within contexts marked by coherent democratic elites. The findings contribute to debates on democratic backsliding and offer valuable insights for scholars, activists, and policymakers seeking to counter right-wing populists holding electoral power.

Introduction

The global rise of right-wing populism has raised important questions about whether its electoral gains reflect short-term shifts or enduring ideological transformation. Since the late 1980s, Central and Eastern European countries (CEECs) have transitioned toward democratic governance and integrated into the liberal international order. However, their democratic systems remain fragile—characterized by recurring institutional threats and backsliding, even after accession to the European Union (EU) (Tomini, 2014). Populist parties have become a persistent feature of Central and Eastern European (CEE) politics since the start of the century, retaining power in ways that challenge prior assumptions about their weak governing capacity. In some cases, such as Hungary, right-wing populists have systematically eroded democratic checks and balances, transforming democracy into an electoral autocracy (European Parliament, 2022). The populist electoral surge has not only strained these countries’ relations with the EU but has also cast doubt on the long-term prospects of democratic consolidation in the region.

At the same time, citizens across CEE have actively resisted their populist incumbents. In the Visegrád Four, several movements have mobilized mass protests—largest since the fall of communism—explicitly targeting populist governments. These movements have not only aimed to remove populist incumbents but have also championed pluralism and the defense of democratic values and institutions. Yet, despite similar levels of mass mobilization, their electoral impact has varied: while movements in Poland and Czechia contributed to the defeat of populist parties in elections, those in Slovakia and Hungary had limited influence. This study asks: Why, then, do some anti-populist social movements achieve success in CEE while others do not? Although scholars have analyzed the strategies and dynamics of anti-populist movements in Western democracies (Fisher, 2019; Gose and Skocpol, 2019; Meyer and Tarrow, 2018), a theoretical framework to explain variation in anti-populist movement success across CEE is still lacking.

Identifying the factors that increase the likelihood of democratic movements succeeding against populist incumbents is vital for scholars, activists, and policymakers alike. This knowledge is especially urgent given that populists in power are four times more likely to erode democratic institutions (Kyle and Mounk, 2018), often doing so gradually enough that citizens do not realize what they have lost until it is too late (Lührmann and Lindberg, 2019). Authoritarianism now impacts approximately 72 percent of the global population (Nord et al., 2025), severely undermining democratic accountability and depriving individuals of fundamental rights, freedoms, and access to essential public goods. Populist leaders exacerbate these threats by scapegoating marginalized communities, polarizing society, and weakening the institutions that safeguard human rights and the rule of law, thereby accelerating democratic erosion.

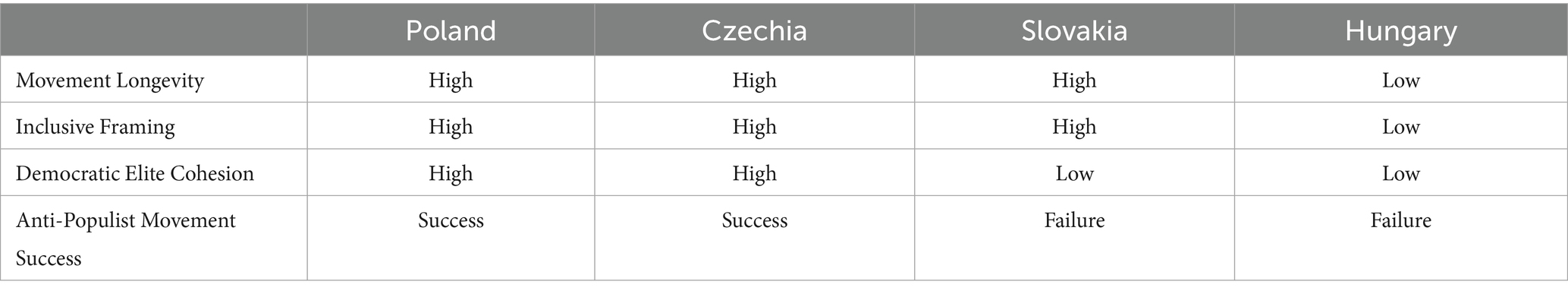

I argue that anti-populist social movements are more likely to succeed in CEE when they sustain broad-based mobilization over time and operate under conditions of unified democratic opposition. Accordingly, countering right-wing populism in the region depends on three necessary conditions: the longevity of anti-populist movements, the inclusivity of their framing, and the cohesion of democratic oppositional elites. Movements that are sustained and adopt inclusive, resonant frames are more likely to achieve electoral success. Success is also more likely when unified democratic elites contest populists in elections. In contrast, movements that are short-lived, narrowly framed, and operate in contexts of democratic elite fragmentation often face greater difficulty achieving electoral impact. This study compares major anti-populist social movements in the Visegrád Four between 2015 and 2025, employing process tracing to examine the factors underlying variations in their electoral impact despite shared political and historical contexts. The paper begins with a literature review, develops and tests hypotheses concerning the conditions under which anti-populist movements achieve electoral impact, presents a comparative case analysis, and concludes with key findings, implications, and directions for future research.

Literature review

Demand-side explanations for populism in CEE

Existing literature points to a variety of overlapping economic explanations for the global ascent of right-wing populism. One prominent explanation highlights how exposure to international trade increases support for protectionist and nationalist policies, particularly as a backlash to the China trade shock (Autor et al., 2020; Barone and Kreuter, 2021; Colantone and Stanig, 2018). Others point to the political consequences of financial crises, which deepen economic insecurity and distrust in mainstream parties (Funke et al., 2016; Morelli et al., 2025). A third strand of literature emphasizes economic insecurity more broadly as a driver of right-wing populism (Guiso et al., 2024), particularly when linked to unemployment (Algan et al., 2017) and automation (Anelli et al., 2019). Additionally, some scholars interpret the rise of right-wing populism as a voter backlash against neoliberalism and the erosion of redistributive protections (Bischi et al., 2022; Mouffe, 2018). Overall, this body of research reflects a demand-side perspective: economic pain and dislocation push voters toward populist politicians who promise protection and change.

The economic drivers behind the global rise of populism have also manifested in CEE, where they have been further shaped by the region’s distinct post-communist legacy. In CEECs, neoliberal economic reforms during the post-communist transition were pivotal to the emergence of populist parties (Rupnik, 2007; Bustikova and Kitschelt, 2009). To attract foreign investment, CEE governments pursued aggressive market liberalization to signal their alignment with global economic norms and secure capital inflows (Appel and Orenstein, 2018). Social democratic parties alienated working-class voters by embracing neoliberalism, creating space for populists to gain appeal by blending protectionist, redistributive policies with nativist rhetoric (Snegovaya, 2024). Populist parties also exploited economic disparities between Western Europe and CEE to stoke dissatisfaction with EU integration, despite CEECs’ relative economic success because of it (Epstein, 2020). These strategies allowed populists to expand their electoral appeal among voters disillusioned with neoliberal economic policies.

Cultural explanations are equally essential to understanding the rise of right-wing populism globally and regionally. Norris and Inglehart’s (2019) cultural backlash thesis links populist support to older generations’ resistance to younger cohorts’ post-materialist values. Other scholars highlight the interplay of economic grievances and cultural anxieties, particularly the perceived decline in subjective social status among populist supporters (Gidron and Hall, 2020). Building on this logic, Nai et al. (2023) show that support for populist radical right parties is positively associated with public preference for ethno-traditional cultural symbols abroad. Their findings suggest that nativist cultural worldviews shape not only domestic politics but also transnational cultural preferences. In CEECs, cultural backlash often manifests as rejection of cosmopolitan values associated with liberal elites (Krastev, 2007), driven by resentment toward Western-imposed liberal norms and the perceived erosion of national autonomy (Krastev and Holmes, 2019). Even in Poland—where EU membership remains broadly popular—Eurosceptic populists maintain support by condemning the EU’s liberal values, while casting themselves as defenders of Europe’s “true” heritage rooted in neo-traditionalism (Styczyńska, 2025). Thus, populist appeal in CEE is driven not only by economic dissatisfaction but also by resistance to liberal values.

Supply-side explanations and institutional weakness in CEE

In addition to voter grievances, some scholars argue that the rise of populism can be understood through supply-side dynamics. As Berman (2019) argues, populism reflects the inability of political institutions to effectively address the concerns of their electorates. Katz and Mair (1995) characterize mainstream political parties as operating like “cartels,” having largely abandoned their representative functions. Building on this, Schlozman and Rosenfeld (2019) argue that as these parties grow increasingly “hollow,” they maintain privileged access to state resources while becoming disconnected from their constituencies. These trends are even more pronounced in CEE, where mainstream parties were “born hollow” (Cianetti et al., 2018), lacking institutionalization (Ekiert and Ziblatt, 2013), grassroots presence (Van Biezen et al., 2012), and stable voter linkages (Saarts, 2011). The region thus experiences a proliferation of short-lived parties built around anti-corruption appeals and celebrity leadership (Haughton and Deegan-Krause, 2020), with protest voting for populist parties serving as an outlet for widespread disillusionment with mainstream politics (Pop-Eleches, 2010). These domestic vulnerabilities are compounded by the EU’s own democratic deficit (Mair, 2013), enabling populists to exploit both national and supranational shortcomings to get elected.

Once in office, CEE populists tend to consolidate power and implement illiberal reforms. Scholars have documented cases of state capture and strategic legalism used to implement illiberal policy changes in CEECs (Scheppele, 2018; Pirro and Stanley, 2022; Dimitrova, 2018; Malová and Gál, 2021). Governing populist parties have eroded judicial independence, constitutional checks, and media freedom (Fomina and Kucharczyk, 2016; Bánkuti et al., 2012), while undermining their opposition (Vachudova, 2019). Moreover, populists strengthen loyal civil society organizations instead of those that could keep them accountable. In Poland, civil society has become increasingly fragmented since 2000 due to the rise of nationalist, anti-liberal, and religious networks supported by media, political parties, and the Catholic Church (Ekiert, 2020). In Hungary, Fidesz leveraged the Civic Circles Movement to mobilize educated, conservative middle-class supporters (Greskovits, 2020). Conversely, liberal and social democratic parties on the Left have struggled to develop civil society ties, as evidenced in Poland, where traditional links to labor unions have deteriorated (Ost, 2005).

Conceptualizing CEE populism

Populism in Central and Eastern Europe tends to be exclusionary, defining the people along cultural, ethnic, or civilizational lines (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, 2013). Ideologically flexible, CEE populists encompass former mainstream conservatives like Fidesz and PiS, as well as the previously center-left SMER-SD. Several conceptual frameworks shed light on these regional dynamics: Bugarič (2019) characterizes Hungarian and Polish populism as authoritarian, blending nationalism with populist rhetoric; Buštíková and Guasti (2019) emphasize its technocratic dimension, focusing on managerial competence and anti-corruption efforts; and Enyedi (2024) describes it as paternalist, endorsing strong leadership that legitimizes selected elites. Stubbs and Lendvai-Bainton (2020) highlight how the authoritarian-populist nexus in the region is closely tied to neoliberal restructuring and radical conservatism, where deservingness is increasingly defined through heteronormative, nationalist, and exclusionary criteria. Together, these perspectives highlight the complex and hybrid nature of right-wing populism in the region, whose multifaceted appeal resonates with the public through displays of decisive leadership, clear delineation of outsiders, and tangible benefits for core supporters.

Resistance to populism in CEE

Despite extensive research on the causes and characteristics of right-wing populism in CEE, considerably less attention has been paid to the conditions under which social movements effectively challenge it. Globally, civic resistance has emerged as a critical counterforce to populist rule (Guasti, 2020), with a growing body of literature examining its nature and features (Hamdaoui, 2021; Sombatpoonsiri, 2018; Havlík and Kluknavská, 2022; Vüllers and Hellmeier, 2022; Sato and Arce, 2022). Scholars have long explored the conditions under which protests succeed, particularly in preventing democratic erosion (Gamboa, 2022; Beissinger, 2025) and influencing electoral outcomes (McAdam and Tarrow, 2010; Gillion and Soule, 2018; Wasow, 2020). However, CEE social movements face unique challenges, underscoring the need for closer examination of the conditions under which anti-populist resistance can succeed under local circumstances.

The scale and effectiveness of anti-populist mobilization vary significantly across the region (Vachudova et al., 2024). Della Porta (2025) demonstrates that, despite repression, civic activism in the region has intensified since 2010, becoming more autonomous and diverse, with protests increasingly focused on labor, environmental, and gender rights. Recent research has also begun to explore why CEE citizens mobilize in defense of democratic norms and the outcomes they seek to achieve (Blackington et al., 2024), as well as how ethnic minority activism in the region bolsters democratic resilience (Rovny, 2023). Yet significant gaps remain in this literature. This study addresses one of them through a comparative analysis of anti-populist social movements in the Visegrád Four, identifying key conditions that help explain the variation in their success.

Theoretical argument

This study argues that effectively countering right-wing populism in CEE depends on three necessary conditions: the longevity of anti-populist social movements, inclusivity in their framing, and democratic elite cohesion. The central research question guiding this analysis is: What explains the variation in the success of anti-populist social movements across CEE? Successful anti-populist movements tend to engage in sustained organizing, adopt inclusive frames, and benefit from unified oppositional elites. In contrast, unsuccessful movements tend to be short-term and narrowly framed, with democratic elites opposing right-wing populism remaining fragmented and uncoordinated. Necessity is conceptualized as requiring these conditions to meet a high threshold. A key assumption of this theory is that the political system remains open to coalition-building, making anti-populist social movements more likely to succeed in proportional representation systems than in majoritarian ones.

Conceptualization of anti-populist movement success

I base my conceptualization of anti-populism on Müller’s (2016) definition of populism as a moralistic, binary worldview that pits a unified people against corrupt elites, marked by anti-elitism and anti-pluralism. Accordingly, I define anti-populism as an ideology that promotes democratic pluralism and defends power-sharing institutions from populist erosion, with anti-populist movements aiming to protect democracy by endorsing both pluralism and elitism. In this paper, I define anti-populist movement success as the electoral defeat of a populist incumbent and party in national parliamentary elections. Populists in power often use their legitimacy and state resources to undermine democratic institutions (Levitsky and Ziblatt, 2018; Pappas, 2019), making their electoral removal critical. While movements may pressure populists to resign, defeating them at the ballot box is more legitimate, sustainable, and difficult. In the Visegrád Four, parliamentary elections are especially consequential, as they directly impact populists’ access to resources and ability to capture institutions.

Hypotheses

First, long-term social movements are more effective in challenging right-wing populism than short-term initiatives in the region (Hypothesis 1). I hypothesize that the longevity of social movements—measured by sustained public activity over a period of at least two consecutive years—is positively associated with their capacity to keep their cause salient in the public sphere. This, in turn, may influence electoral outcomes. Over time, long-term mobilization may more effectively shift public discourse and elite perceptions, making it harder for populists to control the narrative and suppress dissent (see Bryan and Perevezentseva, 2021). Sustained visibility can erode the legitimacy of populist regimes and help create favorable conditions for democratic opposition to succeed at the ballot box.

Second, successful anti-populist social movements in CEE are more likely to adopt inclusive framing (Hypothesis 2). Social movement frames are collections of beliefs and meanings that guide and justify the actions and campaigns of a social movement, and they may vary in their inclusivity, flexibility, and resonance (Benford and Snow, 2000). I operationalize inclusive framing as the articulation of grievances in ways that emphasize shared values and collective threats rather than partisan or group-specific interests. Inclusive framing may enable movements to attract and mobilize a broad base of participants, particularly rural populations—often portrayed by populists as neglected by liberal elites. By uniting and fostering solidarity across diverse social groups, inclusive framing may help anti-populist social movements counter populist polarization. Large-scale nonviolent mobilization, in turn, may pose a credible threat to populist leaders while enhancing domestic and international legitimacy of the movement (Chenoweth and Stephan, 2011). Thus, it is hypothesized that variation in the inclusivity of social movement framing is linked to differences in the electoral outcomes of anti-populist movements in the Visegrád Four.

Third, democratic elite cohesion is positively associated with the success of anti-populist efforts in Central Europe (Hypothesis 3). In bipartisan systems such as the United States, anti-populist social movements like the Women’s March successfully mobilized voter support behind the Democratic Party in the 2018 midterm elections (Gose and Skocpol, 2019). In parliamentary systems, where anti-populist voters may be spread across multiple parties, strategic coalition-building among democratic elites can be crucial to prevent vote fragmentation. Operationally, elite unity is reflected in the formation of pre-election coalitions and coordinated efforts to present a united front against populism. In the absence of such coordination, fragmented opposition often alienates voters through infighting and competition. Coalition-building and strategic alignment among democratic elites therefore often significantly increase the chances of defeating populist parties in parliamentary elections.

Alternative explanations

There are two main alternative explanations for anti-populist social movement success in the Visegrád Four. The first is pressure and sanctions from the EU, particularly through legal and financial mechanisms. Such pressure was observed most prominently in Poland and Hungary, as EU material sanctions against both populist governments began in 2021 (Blauberger and Sedelmeier, 2025). While EU sanctions may have contributed to the defeat of PiS, they appear to have been insufficient to unseat Hungary’s Fidesz, suggesting that external pressure alone does not fully explain populist electoral defeat.

The second explanation concerns the strength of the populist government at the time of elections—specifically, whether declining popularity or poor performance drive electoral outcomes. Some may argue that political demands influence both populist strength and anti-populist mobilization, shaping electoral outcomes beyond movement features, strategies, or democratic elite cohesion. However, political demands are continuously framed, contested, and mutually shaped by both populist and anti-populist actors and organizations, which limits their ability to independently explain variations in electoral outcomes. For example, even when populists fail to address key political demands and crises, they often successfully reframe their shortcomings through conspiracy theories that scapegoat “the other” and consolidate their base (see Plenta, 2020). Thus, these alternative explanations do not fully account for the observed variation in anti-populist social movement success across the Visegrád Four.

Methods and data

Czechia, Hungary, Slovakia, and Poland were selected as case studies due to their shared political and historical contexts, geographic and cultural proximity, and similarities in political and civil society development. All four countries have experienced a post-communist populist surge, with Hungary and Poland exhibiting more pronounced democratic backsliding as a result. Each has also witnessed nationwide anti-populist social movements with varying degrees of success in challenging incumbents. Employing a Most-Similar Systems Design (MSSD) framework (Przeworski and Teune, 1982), this study compares these cases, minimizing confounding variables and enhancing internal validity. Process tracing is used to test the hypotheses and causal mechanisms (Bennett and Checkel, 2014), allowing for an in-depth examination of the specific dynamics underlying variation in the success of anti-populist social movements while reducing the risk of reciprocal causation (Collier, 2011). The temporal scope is limited to the past decade (2015–2025) to reduce contextual discrepancies and avoid data limitations associated with a broader time frame.1

While ideological variation exists across the Visegrád Four, this study does not treat ideology as a primary explanatory factor. As noted in the literature review, party systems in the region were “born hollow” and remain weakly institutionalized, and populist actors are often ideologically fluid (“Conceptualizing CEE Populism”). Similarly, anti-populist movements tend to form broad coalitions grounded in shared democratic values rather than Left–Right or other prevailing ideological divides. This approach aligns with the paper’s conceptualization of anti-populist social movements as defenders of democratic pluralism and elitism rather than conventional political ideologies, thereby justifying a focus on strategic and organizational factors (“Conceptualization of Anti-Populist Movement Success”).

The author collected a broad swath of primary and secondary data on major anti-populist social movements in the Visegrád Four between 2015 and 2025. This included semi-structured interviews, news articles, media, and communications from social movements, civil society organizations, and political actors, as well as secondary sources such as academic articles. The qualitative data analysis used triangulation and thematic coding, along with the identification of causal process observations (CPOs)—insights or data points that contribute uniquely to causal inference (Collier et al., 2004). Coding was conducted using a combined inductive and deductive approach, enabling both descriptive and interpretive analysis. Codes were then organized into higher-level thematic categories. This multifaceted approach allowed for the identification of recurring strategic patterns and a deeper understanding of how specific political outcomes unfolded across cases. It also offered a systematic basis for assessing the study’s hypotheses (see Table 1).

A total of 31 semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted by the author, primarily during fieldwork in Slovakia and Czechia as a visiting doctoral student at Comenius University (2022–2023). Respondents included social movement leaders, participants, and political elites from Slovakia and Czechia. They were recruited through snowball sampling initiated via academic and departmental contacts, which facilitated access to relevant participants (see Goldstein, 2002; Kapiszewski et al., 2015). Eligibility was based on active involvement in anti-populist movements or relevant political roles. Additional details regarding interview settings, procedures, and questions are provided in Appendix A.

Poland

The pro-abortion movement in Poland exemplifies anti-populist social movement success, as it helped propel Tusk’s coalition to defeat PiS in the 2023 parliamentary election. Between 2015 and 2023, PiS eroded democratic institutions and restricted civil liberties but was ultimately ousted amid record voter turnout. Pro-choice feminist activists mobilized large-scale protests beginning in 2016 against abortion restrictions, using grassroots tactics and inclusive framing to challenge both the government and the Catholic Church, while keeping reproductive rights consistently on the public agenda. Sustained mobilization helped increase political engagement, especially among women and youth. The Civic Coalition and civil society organizations leveraged EU pressure and mobilized voters to secure victory against PiS in the 2023 parliamentary election.

The rise of PiS and the erosion of Polish democracy

In 2015, the right-wing populist party PiS, led by Jarosław Kaczyński, secured an absolute majority in Poland’s parliamentary elections. PiS campaigned on a platform emphasizing welfare policies, alongside anti-immigration, and anti-abortion positions (BBC News, 2015a). This victory, coupled with the election of PiS candidate Andrzej Duda to the presidency in 2015, allowed the party to implement drastic illiberal policies. Despite a slightly reduced mandate in the 2019 elections, PiS retained power, continuing its campaign against “corrupt liberal elites” and intensifying its attacks on LGBTQIA+ rights (Sojka, 2019). However, in the 2023 parliamentary elections, PiS was defeated by a coalition of three coalitions led by Donald Tusk, with a record-high voter turnout of 74 percent.

Over its eight-year tenure, PiS systematically undermined democratic institutions. The party eroded judicial independence by establishing a disciplinary chamber for judges, packing courts, and ignoring Constitutional Tribunal rulings (Davies, 2018). Additionally, PiS expanded political influence over judicial appointments and granted the justice minister oversight of prosecutors (Wlodarczak-Semczuk, 2023). PiS also politicized the media, turning public broadcasting into a tool of propaganda and securing control over local press through state-owned Orlen’s 2020 acquisition of the news agency Polska Press (European Centre for Press and Media Freedom, 2023). PiS targeted its opposition by manipulating electoral laws and using state resources for campaigns (Wójcik, 2023). PiS vilified liberal civil society organizations (CSO), imposing legal and financial restraints on them while favoring loyal CSOs (Korolczuk, 2023). These tactics significantly skewed the electoral playing field in PiS’s favor, making its 2023 defeat by the opposition even more remarkable.

Committee for the defense of democracy

The Committee for the defense of democracy (KOD) was the first grassroots anti-populist resistance movement to emerge in opposition to PiS. Founded by Mateusz Kijowski, KOD organized its inaugural protest march on December 12, 2015, in response to PiS’s actions undermining the Constitutional Tribunal and imposing broader judicial restrictions (Budrewicz, 2016). According to Kijowski (quoted in BBC News, 2015b), KOD sought to stand as a non-partisan front to protect democracy and express discontent over the erosion of democratic institutions. KOD’s peak period of protest activity was between 2015 and 2016, when tens of thousands of participants gathered across 40 Polish cities and even internationally (Budrewicz, 2016).

From the start, the movement supported political elites who joined its demonstrations while maintaining a firm commitment to nonpartisanship (Karolewski, 2016). KOD also fostered a positive relationship with the European Union, establishing formal representation in Brussels to advocate for democratic values (Matthes, 2021). Though its momentum declined somewhat after 2017, KOD remains an active pro-democracy organization with 16 regional branches throughout Poland (Committee for the Defence of Democracy, 2024). During the 2023 parliamentary elections, the movement played a role in election monitoring and enhancing civic participation through its Citizens’ Election Control project (The EEA and Norway Grants, 2025). KOD is widely recognized as an early and foundational effort to mobilize Polish civil society from the grassroots against PiS and for supporting other civil society initiatives, including the feminist pro-choice movement, in challenging PiS’s policies (Marczewski, 2024).

The pro-choice movement’s role in anti-PiS mobilization

The pro-choice movement played a crucial role in the mass mobilization of grassroots civil society against the PiS government and shifting public sentiment against it. The 2016 Black Protests marked the first major wave of feminist activism in response to a proposed total abortion ban drafted by the ultra-conservative advocacy group Ordo Iuris (Davies, 2016). These protests drew over 100,000 participants across 137 cities, becoming the largest demonstrations in Poland since the fall of communism (Lipska and Naumann, 2025). In 2016, approximately 200,000 women participated in a general strike by refusing to work, demonstrating widespread support for the cause (Noryskiewicz, 2020). As a result, the 2016 Black Protests successfully pressured the PiS government to reject the total abortion ban.

In October 2020, the Polish Constitutional Court issued a ruling that imposed a near-total abortion ban. In response, the All-Poland Women’s Strike (“Ogólnopolski Strajk Kobiet”), a grassroots social movement, mobilized hundreds of thousands in recurring mass protests to defend reproductive rights. The movement harnessed public anger with powerful slogans such as “This is war!,” “Revolution is a woman,” and “J**** PiS” (‘F*** Law and Justice’) (Muszel and Piotrowski, 2020), while using symbolic imagery like coat hangers to convey the dangers of illegal abortions (Wądołowska, 2020). Government forces attempted to suppress the demonstrations through excessive violence, tear gas, and detentions (Beswick, 2020). Despite this repression, the feminist movement persisted for years, staging regular protests—especially after women died from being denied abortions—which kept reproductive rights consistently on the public agenda (Picheta, 2024). Beyond protests, gender activists built grassroots networks, supported local initiatives, provided sex education, and helped women access abortion services abroad (Lipska and Naumann, 2025). PiS support subsequently declined from 43.6% in 2019 to 35.4% in 2023 (Guerra and Casal Bértoa, 2023).

The movement mobilized large-scale participation by framing the protests as part of a broader resistance to PiS and its anti-rights agenda. As Marta Lempart (in Amnesty International, 2021), co-founder of OSK, stated, “Extreme restrictions on abortion are part of a broader assault by Poland’s government on human rights, including women’s rights and LGBTI rights, and the rule of law.” This inclusive framing was reflected in the movement’s establishment of the Consultative Council in November 2020 to coordinate civil society organizations and articulate protest demands extending beyond abortion to LGBTQIA+ rights, secularism, climate policy, and broader social justice (Onet, 2020). The 2020 protests stood out for their intersectionality, drawing women from diverse socio-economic backgrounds, and expanding into rural areas (Zając, 2022). Although the near-total abortion ban remains in place, the movement revitalized Polish civil society, challenged the Catholic Church’s political influence, and contributed to the Civic Coalition’s 2023 electoral victory.

Opposition and civil society in the 2023 elections

During PiS’s 2015–2023 tenure, opposition elites employed several strategies to counter populism. First, opposition parties engaged with social movements and civil society, particularly by supporting reproductive rights and proposing amendments to abortion restrictions (Tronina and Kaźmierska, 2023). Second, they sought to consolidate the opposition vote during elections, notably rallying behind Warsaw Mayor Rafał Trzaskowski, who narrowly lost the 2020 presidential race to PiS’s Andrzej Duda (Rudzinski, 2020). Third, the opposition and civil society raised awareness to alert the EU about PiS’ attacks on democracy and prompt it to put pressure on PiS. As a result of increased scrutiny over PiS’s rule of law violations, the EU triggered Article 7 proceedings in 2017 and introduced the Rule of Law Conditionality Mechanism (Przybylski, 2023). This led to the freezing of up to €137 billion in cohesion and COVID-19 recovery funds for Poland (Liboreiro, 2024). Collectively, these efforts weakened PiS’s popularity and paved the way for a more unified anti-populist front in the 2023 parliamentary elections, where PiS was seeking a third term.

Victory in the 2023 parliamentary elections was made possible through the coordinated mobilization of democratic elites and civil society. Donald Tusk led the Civic Coalition, composed of Civic Platform (KO), the Left (Lewica), and the Third Way (TD), united by a shared goal of reversing democratic backsliding under PiS. Civic Coalition presented a coherent and appealing political agenda that combined pro-EU messaging, support for human rights, and pledges to expand welfare, while also highlighting PiS’s corruption and cronyism (Shea, 2023). In the lead-up to the election, Tusk spearheaded mass protests, including the historic “Million Hearts March” on October 1, 2023, which brought nearly one million people to the streets of Warsaw. Civil society supported these efforts by raising awareness, organizing campaigns to boost voter turnout, and training thousands of election observers (Horonziak and Pazderski, 2023). These initiatives helped drive a record 74% voter turnout—the highest since 1919—with more women voting than men and unprecedented youth participation (McMahon, 2023). Election results also revealed that the Third Way played a pivotal bridging role for bringing in disillusioned conservative voters seeking an alternative to PiS (Szczerbiak, 2023).

Czechia

Million Moments for Democracy, a Czech anti-populist social movement, facilitated the center right Spolu coalition’s efforts to unseat Babiš’s ANO party in the 2021 parliamentary elections. Between 2017 and 2021, Babiš centralized power and undermined democratic institutions through his technocratic populism. Million Moments for Democracy emerged in 2017 as a student-led initiative and grew into a nationwide civic movement that used mass protests, grassroots organizing, and inclusive framing to challenge Babiš’s corruption and democratic backsliding. It pressured opposition parties to unite into electoral coalitions and mobilized thousands of volunteers through its “I Vote for Change” campaign. These efforts contributed to record voter turnout and the victory of the SPOLU coalition, with the movement continuing to influence Czech politics as a civil society organization to this day.

Technocratic populism in Czechia and its limits

The Czech right-wing populist party ANO, founded in 2011 by billionaire Andrej Babiš as an anti-corruption movement, was registered as a party in 2012 and quickly rose to second place in the 2013 elections. In 2017, ANO won a landslide victory with nearly 30% of the vote and formed a minority government, making Babiš Prime Minister. The party’s campaign emphasized opposition to corruption, immigration, and deeper EU integration, including rejection of the euro (Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2017). In governance, ANO functioned as a classic business-firm party—an extension of Babiš’s personal interests (Kopeček, 2016)—characterized by anti-political rhetoric and a promise to run the state like a business (Buštíková and Guasti, 2019). Over time, however, the party’s popularity declined amid growing concerns over Babiš’s alleged conflicts of interest. In the 2021 parliamentary elections, ANO was defeated by the center-right SPOLU coalition, led by Petr Fiala, amid the highest voter turnout since 1998 (65.4%) (Havlík and Wondreys, 2021). Additionally, Babiš lost the 2023 presidential election to retired NATO general Petr Pavel.

Between 2017 and 2021, Czechia experienced democratic backsliding under ANO’s rule. Even before entering government, Babiš had acquired the country’s leading media group and used media to pressure political opponents (Dębiec, 2021). Once in power, his party further centralized authority within the state bureaucracy (Hanley and Vachudova, 2018). The Stork’s Nest scandal, in which Babiš was accused of misusing EU subsidies through opaque ownership transfers, exemplifies the kind of corruption, conflict of interest, and institutional shielding that signaled democratic backsliding during his tenure (AP News, 2022). Babiš also undermined judicial independence, notably by dismissing his justice minister after the police recommended charges against him. While ANO did not use its power to tilt the electoral field as aggressively in its favor as Poland’s PiS, Babiš’s technocratic populism—characterized by obscurity and quiet concentration of power—posed significant challenges to democratic accountability and civic mobilization.

Million Moments for Democracy

The Million Moments for Democracy (“Milion chvilek pro demokracii”) movement began as a student-led initiative during the 2017 Czech parliamentary elections, founded by Mikuláš Minář, who feared democratic decline under Babiš (Minář, 2024, personal interview). On the 2017 anniversary of the Velvet Revolution, the movement launched a petition titled “A Moment for Andrej,” which quickly united public discontent by urging Babiš to honor his democratic promises, gathering 30,000 signatures. Heightened concerns over democracy followed key events such as President Zeman’s re-election, Babiš’s lost confidence vote, and revelations of his ties to the communist secret service, prompting the movement to launch a second petition demanding Babiš’s resignation in 2018 (Roll, 2024, personal interview). This petition amassed over 400,000 signatures by summer 2019, solidifying the group’s position as Czechia’s foremost civic activist organization (Minář, 2024, personal interview).

On April 9, 2018, the Million Moments for Democracy movement organized its first formal protest, drawing approximately 20,000 attendees (Minář, 2024, personal interview). Over the following months, it expanded rapidly, connecting with activists in 150 cities and towns across the Czech Republic and later establishing the “Million Moments Network” (Minář, 2024, personal interview). From the outset, the movement employed an inclusive framing strategy that combined negative messaging—exposing Babiš’s corruption and conflicts of interest—with positive narratives emphasizing civic engagement and democratic principles (Roll, 2024, personal interview). This framing was designed to resonate with a wide range of citizens beyond ideological divides. Simultaneously, protests were strategically structured to encourage repeat attendance by offering clear, actionable steps for democratic engagement and cultivating a “neighborly atmosphere” through strict prohibitions on partisanship, violence, hate speech, and aggression (Minář, 2024, personal interview; Zévl, 2024, personal interview). Frequent protests across Prague and Czechia demanding Babiš’s resignation culminated in a June 23, 2019, demonstration at Letná Park, which drew an estimated 250,000 people nationwide, marking the largest protest since the Velvet Revolution (Palickova, 2019). Despite the massive turnout, Babiš refused to resign.

Undeterred, the movement focused on long-term resistance to populism, transitioning into a formal organization with full-and part-time staff between 2019 and 2020 to ensure sustainability (Roll, 2024, personal interview). Throughout this period, it kept issues of Babiš’s corruption and democratic backsliding in the public agenda. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the movement adapted by organizing socially distanced protests and notably painted over 20,000 white crosses in Old Town Square to symbolize pandemic deaths and criticize the government’s mishandling (Gomaa, 2021). After founder Minář left in 2020 to pursue a political career, leadership passed to Benjamin Roll, who continued the movement with the goal of helping political parties defeat ANO in the 2021 parliamentary elections.

ANO’S defeat in 2021 parliamentary elections

As early as 2019, Million Moments for Democracy publicly urged five democratic opposition parties to unite against Prime Minister Babiš, articulate a compelling democratic vision, and broaden their appeal to new voters (Minář, 2024, personal interview). In partial response, the opposition eventually formed two pre-electoral coalitions: the center-right SPOLU and the center-left Pirates/STAN (Minář, 2024, personal interview). These coalitions campaigned extensively on promoting themselves as alternatives to ANO that will preserve democracy and decency, while refraining from campaigning against each other to present a united front against Babiš (Havlík and Kluknavská, 2022). Just days before the elections, revelations from the Pandora Papers confirmed that Babiš had failed to disclose several shell companies used to purchase a multi-million-euro chateau (Alecci, 2021), further reinforcing concerns about his corruption and conflicts of interest—issues that the movement had consistently kept on the public agenda through its mobilization. The revelations further damaged Babiš’s public standing and prompted coordinated denunciations from politicians across both coalitions (Mortkowitz, 2021).

Believing that defeating right-wing populism required mobilizing new and first-time voters, Million Moments for Democracy launched a grassroots contact campaign titled “I Vote for Change.” Leveraging its regional network, the movement recruited nearly 1,000 volunteers to engage in street-level outreach, inform citizens about the democratic coalitions, and encourage electoral participation (Roll, 2024, personal interview). The 2021 parliamentary elections saw one of the highest turnouts, with voter participation increasing by approximately 5% compared to the 2017 election (Havlík and Lysek, 2022). Ultimately, the center-right SPOLU coalition, consisting of the Civic Democratic Party (ODS), Christian and Democratic Union – Czechoslovak People’s Party (KDU-ČSL), and TOP 09, defeated ANO in the parliamentary elections. Building on this success, the movement deployed similar tactics in the 2023 presidential election, formally endorsing Petr Pavel, who went on to defeat Babiš (Roll, 2024, personal interview). Today, Million Moments for Democracy remains active as a movement and civil society organization committed to defending democratic norms.

Slovakia

Robert Fico, Slovakia’s long-dominant populist leader and founder of SMER-SD, was forced to resign in 2018 following mass protests by the anti-populist movement For a Decent Slovakia, which emerged after the murder of journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancée. By emphasizing nonviolence, transparency, and inclusivity, the movement united diverse participants and revitalized Slovak civil society. After 2018, it shifted from mass mobilization to grassroots electoral engagement before pausing its activities in the beginning of the pandemic. By its end, the movement had been marginalized from political life, failing to maintain public focus on Fico’s corruption and democratic backsliding. In 2023, Fico returned to power through nationalist-populist appeals, aided by a fragmented democratic opposition. Slovakia’s case illustrates that anti-populist movements may struggle to counter entrenched populism without the presence of a coherent democratic opposition, even when they adopt inclusive framing and endure for several years.

The rise, fall, and return of Robert Fico

Robert Fico served as Prime Minister of Slovakia from 2006 to 2010, from 2012 to 2018, and returned to office after the 2023 parliamentary elections. He founded SMER in 1999 after leaving the communist successor Party of the Democratic Left (SDL’), positioning it as a protest movement outside the dominant pro-and anti-Mečiar blocs (Spáč and Havllk, 2015). Gaining over 13% of the vote in 2002, SMER entered parliament, with Fico’s opposition to Prime Minister Dzurinda’s neoliberal reforms raising his and the party’s profile (Bokes, 2023). Between 2002 and 2004, SMER merged with several left-wing parties and rebranded as Smer–Social Democracy (Malová, 2017). Although its 2006–2010 coalition with nationalist and authoritarian forces hurt its credibility, the party won an outright majority in 2012 (Bokes, 2023). Despite its social democratic rhetoric, Smer-SD is better characterized as a populist party built around Fico’s personal appeal rather than a strong organizational structure (Malová, 2017). While SMER-SD increasingly mirrored European right-wing populist parties in its nationalism and illiberalism, Fico at times displayed pragmatism by pursuing pro-EU policies and avoiding major political confrontations, highlighting a gap between his and his party’s rhetoric and actions.

SMER-SD’s dominance in Slovak politics and Fico’s popularity among voters were challenged in 2018 by the anti-populist social movement For a Decent Slovakia. The movement successfully organized sustained, large-scale public protests, pressuring Fico and key SMER-SD officials to step down. However, Fico’s return to power in the 2023 parliamentary elections, along with his ally Pellegrini’s victory in the 2024 presidential elections, reversed many of the movement’s earlier democratic gains. Since his 2023 re-election, Fico has taken steps to undermine the civic sector, shield himself from investigations, and pursue a politics of vengeance—all of which threaten further democratic erosion and the “Orbánization” of Slovakia (Haughton and Malová, 2023).

For a Decent Slovakia

For a Decent Slovakia (“Za slušné Slovensko”) emerged in March 2018 in response to the murders of investigative journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancée, Martina Kušnírová. Kuciak was widely known for uncovering corruption and exposing links between Slovak politicians and organized crime, particularly the Italian ‘Ndrangheta mafia and members of Robert Fico’s SMER-SD party (Hajdari, 2023). The murders sparked widespread outrage and spontaneous protests across Slovakia. The movement began through spontaneous protest organized as a Facebook event that quickly gained traction, mobilizing through existing social, civic, and professional networks (Participant 1, 2022, personal interview). The movement called for “a thorough and independent investigation into the murders of Ján Kuciak and Martina Kušnírová with the participation of international teams of investigators” and “a new, trustworthy government that will not include people suspected of corruption or having links to organized crime” (For a Decent Slovakia, 2018). The first formal protest of the movement on March 9, 2018, attracted around 60,000 people in Bratislava alone (Makovicky, 2018), marking the largest protest in Slovakia since the fall of communism.

At a February 27, 2018, press conference, flanked by Police Chief Tibor Gašpar and Interior Minister Robert Kaliňák, Fico offered a €1 million reward for information on the murderers, with stacks of cash placed beside him. This “strongman” gesture, which resembled mafia-style tactics, backfired (Verseck, 2018). His refusal to take responsibility led to a sharp decline in public trust, intensifying calls for his resignation and strengthening the resolve of the movement’s leaders and supporters (Participant 9, 2023, personal interview). The movement’s strategy during the peak protest period (March–May 2018) was to sustain public pressure on SMER-SD through large-scale protests (Participant 14, 2023, personal interview). This effort succeeded, resulting in the resignations of Interior Minister Kaliňák on March 12, Prime Minister Fico on March 15, and Police Chief Gašpar on May 31, 2018.

For a Decent Slovakia demonstrated strong organizational capacity by drawing on the experience of seasoned activists and the energy of new participants (Participant 4, 2022, personal interview). The movement employed an explicitly inclusive framing around opposition to corruption and political decency, uniting citizens across ideological, generational, and regional lines in opposition to SMER-SD (Participant 4, 2022, personal interview). The protests—Slovakia’s largest since the Velvet Revolution—spread to dozens of cities, including SMER-SD strongholds, and even extended abroad through the Slovak diaspora. Unlike earlier anti-corruption and anti-government protests, For a Decent Slovakia emphasized nonviolence, inclusivity, and discipline, fostering a peaceful, family-friendly atmosphere that welcomed broad participation (Participant 13, 2023, personal interview). It became the first civic initiative in post-communist Slovakia to achieve such large-scale, coordinated mobilization, with many crediting it for revitalizing the country’s civil society.

The Slovak 2019 presidential and 2020 parliamentary elections

The resignations of top SMER-SD officials reduced For a Decent Slovakia’s ability to sustain mass street mobilization, leading to a sharp decline in protest turnout (Participant 4, 2022, personal interview). In response, the movement reserved large-scale protests for symbolic occasions and shifted toward electoral engagement. To maintain momentum and broaden its reach, the movement organized outreach trips across Slovakia to engage citizens in both urban centers and rural regions ahead of the 2019 presidential and 2020 parliamentary elections (Participant 10, 2023, personal interview). These trips aimed to build trust and reinforce the movement’s participatory image by listening to local concerns, distributing newspapers, and promoting democratic participation and voting (Participant 5, 2023, personal interview). This inclusive, bottom-up approach helped bridge geographic and political divides, sustaining civic engagement beyond the streets.

In 2019, anti-corruption lawyer Zuzana Čaputová of Progressive Slovakia (PS) won the presidential election, defeating a Fico ally with a pro-democracy, anti-populist platform. Her campaign was further strengthened by the strategic withdrawal and endorsement of Robert Mistrík, another PS candidate. Leading up to the 2020 parliamentary elections, For a Decent Slovakia maintained its non-partisan stance, refraining from endorsing specific parties while vocally opposing SMER-SD and far-right candidates and promoting broad democratic renewal (Participant 4, 2022, personal interview). Another populist party, OĽaNO, led by Igor Matovič, capitalized on widespread public discontent with corruption and ultimately ended SMER-SD’s long-standing dominance. There were no significant efforts at pre-electoral coordination or coalition-building among mainstream opposition parties prior to the election. The Slovak opposition remained weak and fragmented, with OĽaNO drawing support from both established opposition parties and newer entrants such as Progressive Slovakia (PS) and Za Ľudí. While OĽaNO’s electoral success demonstrated the effectiveness of anti-corruption mobilization in sustaining public attention on Fico’s abuses, it did not contribute to democratic consolidation, as it merely replaced one populist party with another.

SMER-SD’S return in the 2023 parliamentary elections

Following the 2020 election, Fico regained popularity by exploiting internal conflicts and inefficiencies within the ruling post-electoral coalition, while appealing to pro-Russian sentiments through pledges to end military aid to Ukraine (EURACTIV, 2023). His return to power in 2023 was further enabled by SMER-SD’s nationalist-populist campaign, which promised stability and support for economically vulnerable voters, and by a successful post-election coalition with Hlas-SD and SNS (Haughton et al., 2025). Once again, no efforts were made to coordinate electorally or build pre-election coalitions among opposition parties. The main challenger, Progressive Slovakia (PS), increased its vote share from under 7 to 18% by campaigning on anti-corruption and positioning itself as a credible alternative to Fico (Perevezentseva and Vachal, 2023). However, its prospects were weakened when Hlas-SD, led by Peter Pellegrini, rejected a coalition offer and aligned with SMER-SD instead (Buštíková, 2023). Meanwhile, the Movement For a Decent Slovakia suspended activities early in the pandemic due to leadership burnout (Participant 5, 2023, personal interview) and failed to regain momentum afterward, primarily mobilizing symbolically on anniversaries of the murders, which had diminished salience in the public discourse (Participant 4, 2023, personal interview). While mass mobilization against Fico has intensified since his 2023 return—particularly in 2025 amid growing alignment with Putin—it remains uncertain whether this resistance will translate into electoral success.

Hungary

Fidesz, under Viktor Orbán, maintained power in Hungary since 2010 through nationalist rhetoric, economic patronage, and constitutional manipulation. In response to its authoritarian encroachments on education, labor, and LGBTQIA+ rights, Hungary has witnessed waves of civil resistance. The 2018 mass mobilization for labor rights came closest to fostering inclusive solidarity against the Orbán government but failed to produce policy reversals or influence electoral outcomes. Despite forming a broad pre-electoral coalition against Fidesz in the 2022 parliamentary election, the opposition has struggled to pose a serious electoral challenge, hindered by internal divisions, weak coordination, and an uneven electoral playing field.

Fidesz and Hungary’s democratic backslide

Fidesz was originally founded in 1988 by three dozen college students as a liberal, anti-communist youth movement (Szelényi, 2019). Viktor Orbán, who at the time advocated for market reforms and democratization, started his political career within Fidesz as it registered as a political party in 1990 and entered the Hungarian parliament the same year (Danvers, 2016). In 1994, Orbán took full control of the party and shifted it ideologically to the right, causing an exodus of some of its leaders (Beauchamp, 2018). Orbán served as Hungary’s youngest Prime Minister from 1998 to 2002, leading the country into NATO and advancing EU accession. Unexpectedly, Fidesz lost the 2002 election to the Hungarian Socialist party (MSZP), partly due to Orbán’s failure to distance the party from far-right groups (Kenes, 2020). After a leaked audio revealed Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsány admitting that the Socialist-Liberal coalition had lied to voters about the economy, Orbán capitalized on the scandal to return to power in 2010 (Schleifer, 2014). Since 2010, Fidesz has won four consecutive parliamentary elections with supermajorities, keeping Orbán in power as Prime Minister for 15 uninterrupted years.

Several factors explain the enduring success of Fidesz in Hungary and the difficulties social movements face in challenging its dominance. Orbán has consistently used populist economic policies to serve short-term political and personal goals. Mares and Young (2019) found that Hungary’s workfare program was often manipulated by local officials as a tool of political control, with access to benefits exchanged for votes or withheld as a form of coercion. The party also skillfully mobilized nationalist and anti-immigrant rhetoric while securing support from the Catholic Church (Bozóki and Ádám, 2016). Orbán crafted an “umbrella” enemy in George Soros, effectively using conspiracy theories about him to mobilize supporters and deflect criticism (Plenta, 2020). Finally, Fidesz effectively consolidated the Hungarian right by absorbing rival parties and co-opting their elites (Ivanov, 2024).

Another major challenge for the opposition is that Orbán has tilted the electoral playing field more drastically than other populist leaders in Poland, Czechia, or Slovakia by systematically weakening democratic institutions that could check his power. Since 2010, Fidesz’s supermajority has allowed the party to amend Hungary’s constitution at will, effectively placing itself above the law (Scheppele, 2022). As a result, Orbán has transformed Hungary into an “illiberal democracy” by tightening control over state institutions, the media, and civil society (Shapiro and Végh, 2024). For instance, Hungary’s current electoral system—legally altered by Fidesz—undermines democratic accountability by limiting fair representation for opposition parties and ethnic minorities, while also discouraging citizen participation (Fumarola, 2016). Independent media and civil society organizations have been persistently targeted and harassed by the Orbán government (László, 2025). These systemic changes have made it especially difficult to build and maintain nationwide anti-populist resistance, as well as for the opposition to contest Fidesz in elections.

Civic resistance within the education sector

Hungary has witnessed a series of protest movements in response to the Orbán government’s authoritarian policies targeting education and academic freedom. In April 2017, over 10,000 students, faculty, and supporters marched in solidarity with Central European University (CEU), protesting government legislation that threatened its existence (Thorpe, 2017). In 2020, students and faculty of the University of Theatre and Film Arts (SZFE) organized marches and a building blockade in response to its forced privatization by the Hungarian government and the imposition of a politically aligned board of trustees, drawing international attention and support (RFE/RL’s Hungarian Service, 2020). From 2022 to 2023, Hungarian teachers launched strikes and protests over low pay, poor working conditions, and excessive centralization—actions met with a retaliatory “revenge law” that stripped them of their public employee status (Spike, 2023). Despite their visibility, these fragmented and issue-specific protests lacked sustained momentum and broader coalition-building, ultimately failing to pose a lasting challenge to Orbán’s entrenched rule.

Protests against Fidesz’ legislation

The largest wave of protest against Fidesz’s legislation targeted the so-called “slave law,” which raised the annual overtime cap from 250 to 400 hours in December 2018. For the first time since 1989, a unified front of all parliamentary parties, grassroots movements, and trade unions organized widespread protests and strikes across Hungary—mobilizing tens of thousands in Budapest and reaching over 60 cities (Bottoni, 2019). Demonstrators linked their cause to broader democratic goals, carrying banners with slogans such as “Do not steal!” and “Independent courts!” (Reuters, 2018). This convergence of actors briefly bridged ideological divides and challenged Fidesz’s populist image by portraying the government as serving foreign corporate interests (Szombati, 2019). However, the law was passed, and by 2019 the movement had dissipated, achieving neither a policy reversal nor any electoral impact.

Other protests during Orbán’s long tenure have responded to his government’s escalating crackdown on LGBTQIA+ rights. In 2020, a proposed law banning legal gender changes sparked demonstrations and warnings from EU officials about rising discrimination (EURACTIV, 2020). Protests intensified in 2021 after the government passed legislation echoing Russia’s 2013 “gay propaganda” law, which equated homosexuality with pedophilia and banned LGBTQIA+ content (Korkut and Fazekas, 2021). Activists responded by erecting a 10-meter-high rainbow heart near Parliament and pledging civil disobedience (Spike, 2021). In 2025, after a new law banned Pride events and authorized facial recognition to identify participants, thousands blocked a major bridge in Budapest, and more than 10,000 joined a satirical “Gray Pride” march on April 12, with weekly demonstrations continuing ahead of the planned June 28 Pride (Le Monde with AFP, 2025). Still, the movement has struggled to build broad coalitions through inclusive framing due to the discrimination, marginalization, and political scapegoating of LGBTQIA+ individuals and rights under Fidesz.

Opposition strategies and parliamentary elections

The Hungarian opposition has used various tactics to challenge Fidesz but has struggled since the 2006 Őszöd scandal and Ferenc Gyurcsány’s continued political presence, which alienated many voters (Bogden, 2021). In the 2018 election, opposition parties attempted to unify their votes by strategically withdrawing some candidates in favor of others, but coordination remained weak, resulting in votes being split across several parties (Horvath, 2018). In 2022, the six-party technical coalition United for Hungary—comprising the Democratic Coalition (social liberal), Jobbik (far-right, rebranded conservative), Momentum Movement (liberal), Hungarian Socialist Party (social democratic), LMP (green liberal), and Dialogue for Hungary (green progressive)—united behind conservative Péter Márki-Zay but still fell short. United for Hungary struggled with ideological differences, internal divisions, mutual distrust, and competing ambitions, which undermined its ability to present a unified front against Orbán (Broszkowski, 2023). The opposition coalition also overestimated voter loyalty, as many Jobbik supporters ended up voting for Orbán or the newly emerged far-right party, Mi Hazánk (Lorman, 2022). This lack of coordination, combined with Fidesz’s structural advantages, undermined the opposition’s efforts.

Protests and rallies accompanied both the 2018 and 2022 elections, with civil society groups focusing on activist training, voter mobilization, fraud monitoring, and broad awareness campaigns (aHang, 2022). In 2022, Hungarian civic organizations led by aHang organized the country’s first opposition primary, mobilizing over 800,000 voters and thousands of volunteers to support unified pro-democracy candidates, which boosted voter engagement (Whitman, 2024). Democratic forces also achieved local breakthroughs against Fidesz, notably Budapest’s Green Mayor Gergely Karácsony, who won the 2018 mayoral election through an intensive grassroots campaign with direct voter contact (Bayer, 2019). This approach proved effective beyond Budapest, as coordinated joint candidates and grassroots efforts helped opposition parties overcome Fidesz’s strict media control and win four additional municipal seats (Végh, 2019). Nevertheless, the most prominent elite challenger to Orbán today is Péter Magyar, a former Fidesz businessman who gained popularity after a 2024 corruption scandal, drawing large-scale anti-Orbán rallies. However, even if Magyar’s TISZA party wins in 2026, it is likely to represent a younger version of Fidesz’s rule rather than a genuine democratic transformation.

Discussion

Much of the existing literature on right-wing populism has concentrated on identifying the conditions that enable its rise, including economic grievances and cultural backlash (e.g., Autor et al., 2020; Gidron and Hall, 2020; Norris and Inglehart, 2019). This study shifts the focus from structural explanations of right-wing populism’s rise to its resistance, highlighting how movement agency, framing, and elite dynamics shape anti-populist electoral success. By examining cases of anti-populist mobilization in CEE over the past decade, it identifies the specific conditions under which movements can effectively challenge populist incumbents, even amid persistent economic discontent and cultural backlash. This research builds on recent scholarship emphasizing that civic resistance in CEE requires context-specific analyses that reflect the region’s political, social, and institutional dynamics (e.g., Della Porta, 2025; Blackington et al., 2024; Rovny, 2023). By analyzing how anti-populist social movements in the region shape electoral outcomes, this study contributes to growing literature on the relationship between civic mobilization and elections (e.g., McAdam and Tarrow, 2010; Gillion and Soule, 2018; Wasow, 2020), offering a valuable regional perspective. Findings support all three hypotheses, highlighting the importance of social movement longevity, inclusive framing, and democratic elite cohesion in contributing to successful anti-populist outcomes in the Visegrád Four.

Hypothesis 1, which proposed that long-term social movements are more effective in challenging right-wing populism than short-term initiatives, is fully supported. In Poland, the feminist movement played a central role in the defeat of PiS in parliamentary elections by sustaining civic resistance against its assault on reproductive rights. Mobilizing since 2016, it drew on a strong infrastructure of NGOs and grassroots networks to maintain long-term engagement both on and off the streets. Similarly, in Czechia, Million Moments has maintained momentum since 2017. Its longevity was aided by its professionalization as an NGO and the creation of an impressive national volunteer network. These cases indicate that movement longevity appears to support sustaining public attention on the dangers of populism, influencing political agendas, and applying pressure on both elites and voters.

Hypothesis 2, which posited that successful anti-populist movements are more likely to adopt inclusive framing, is also supported. The pro-choice movement in Poland employed inclusive framing by emphasizing the life-threatening consequences of abortion restrictions, presenting reproductive rights as a human rights and social justice issue, and warning against the dangers of clericalism. This framing resonated across partisan and regional lines, particularly among women and youth, as reflected in their increased electoral turnout. Million Moments has framed its cause around resisting populist corruption and democratic backsliding, while maintaining a positive message around the value of democracy and civic engagement. The movement sustained momentum across electoral cycles by linking ANO’s inadequate pandemic response to broader issues of mismanagement and corruption. These strategies appear to have helped both movements build broad coalitions of diverse supporters and mobilize constituencies across partisan lines, thereby enhancing their capacity to effectively challenge the polarizing tactics of populist incumbents.

The findings also lend support to Hypothesis 3, underscoring the importance of democratic elite cohesion in fostering anti-populist electoral outcomes. In both Poland and Czechia, broad-based mobilization was matched by effective pre-electoral coordination among democratic elites. Broad mobilization in Poland was further reinforced by effective pre-electoral coordination by the opposition, as Donald Tusk facilitated coalition-building that minimized vote-splitting in the parliamentary elections. The Czech movement pressured political elites to form two anti-populist coalitions in the 2021 parliamentary elections and endorsed both, while oppositional elites in turn adhered to strict mutual non-competition during their campaigns. In both cases, strategic coordination among democratic elites presented voters with credible alternatives to populist incumbents.

Crucially, in both Poland and Czechia, anti-populist movements that endured over time, adopted inclusive framing, and operated within contexts of democratic elite cohesion influenced electoral outcomes, offering support for the theoretical argument. It is important to note that these two anti-populist movements varied in their specific demands, grievances, tactics, and emotional appeals. While Poland’s reproductive rights movement channeled anger—using provocative slogans and imagery—Million Moments adopted a more civic-minded, peaceful approach to highlighting concerns over Babiš’s corruption and democratic erosion. Ultimately, in different national contexts, the use of inclusive framing—emphasizing shared values and collective threats—appears important for uniting those who oppose populism in large-scale, nationwide mobilization and motivating them to vote for the opposition.

The negative cases of Slovakia and Hungary provide further evidence that the absence of any one of the three hypothesized factors can undermine anti-populist outcomes. For a Decent Slovakia demonstrated longevity and inclusive framing from 2018 to 2020. The movement successfully kept the issue of SMER-SD’s corruption and assault on democracy—highlighted by the murder of a journalist and his fiancée—on the public agenda, sustaining widespread civic engagement. However, in the 2020 parliamentary elections, the fragmented democratic opposition failed to present a credible electoral alternative to populism. Thus, a different populist party, OĽaNO, capitalized on the movement’s popularity and won the 2020 election on its anti-corruption platform. For a Decent Slovakia largely dissipated during the COVID-19 pandemic and concerns over Fico’s corruption lost salience. Robert Fico’s 2023 return was facilitated by his appeal to economically vulnerable voters, his successful coalition with Hlas-SD, and the lack of cohesion among his pro-democratic opposition.

In Hungary, no anti-populist movement achieved the sustained mobilization observed in Poland, Czechia, or Slovakia. While labor rights protests briefly adopted resonant and inclusive framing, they failed to sustain long-term mobilization. The opposition’s internal fragmentation, lack of coordination, and inclusion of the formerly far-right Jobbik undermined its democratic credibility and failed to attract broader support in parliamentary elections. The resulting ideologically incoherent coalition presented no credible alternative to Orbán. A unified strategy rooted in democratic values, like those seen in Poland or Czechia, may have been more effective. However, Hungary’s severe democratic backsliding—characterized by media control, electoral manipulation, and civil society repression—creates structural barriers that constrain movement success and render electoral victories unlikely, even when key conditions are met. While Poland’s reproductive rights movement succeeded despite significant restrictions, Hungary’s context more closely resembles competitive authoritarianism rather than democracy, falling outside the scope of this framework (see Levitsky and Way, 2010). In competitive authoritarian contexts, anti-populist movements may need to focus on extra-electoral strategies, such as pressuring elites to resign or waiting for windows of political opportunity when repression subsides.

These findings contribute to the literature on contentious politics and democratic backsliding by identifying the specific conditions that facilitate the translation of anti-populist social movement mobilization into electoral impact, even amid entrenched populist incumbents. Nevertheless, the limitation of this research lies in a restrictive operationalization of anti-populist movement success, focusing primarily on national-level outcomes in parliamentary elections. Future research should investigate alternative forms of success, such as victories in other types of elections or the passage of key legislation. Additionally, while this study emphasizes periods of heightened mobilization, it does not examine in depth the routine activities of civil society organizations, their interactions with social movements and political parties, or their specific roles and limitations in resisting populism. Lastly, while this study only briefly mentions local-level political developments, notable achievements such as the “Pact of Free Cities” highlight the importance of subnational and local politics in democratic resilience. The role of local governance in CEE in countering populism represents a promising area for future research.

Conclusion

By focusing on the conditions that enable anti-populist social movements to influence electoral outcomes, this study addresses the critical question of what factors are associated with successful civic resistance against entrenched populism. It shifts attention away from the structural causes of right-wing populism toward the dynamics within its opposition, suggesting that social movement longevity, inclusive framing, and democratic elite cohesion are important conditions that can facilitate civic mobilization to challenge populist incumbents in CEE. This research paper also advances the region-specific literature by filling gaps related to explaining the variation in the effectiveness of anti-populist mobilization.

Contributing to both the regional literature on CEE and the broader scholarship on populism—where anti-populist resistance remains under examined—this study also advances the literature on social movement by linking the conditions for movement success to electoral dynamics. Practically, the findings underscore the importance of sustained organizing, as long-term engagement appears to keep populist threats on the public agenda. Inclusive framing played an important role in mobilizing diverse constituencies, while elite unification helped facilitate a credible electoral alternative to populism. These findings have broader relevance for other backsliding democracies, showing that even under entrenched populist rule, social movements can meaningfully influence electoral outcomes. Future research should explore how these conditions operate in other regional and global contexts to further refine and expand our understanding of anti-populist resistance.

Data availability statement

The data presented in this article are not readily available, as they are derived from qualitative research, including personal interviews with social movement participants, leaders, and political elites conducted during fieldwork. Data collection was conducted in accordance with approved IRB protocols and procedures. No publicly available datasets were used.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were approved by the Institutional Review Board at American University. The human subjects research used in this article was conducted in accordance with local legislation and institutional requirements. Participants provided either written or oral informed consent to participate in the study, depending on their role, in line with existing IRB requirements.

Author contributions

AP: Investigation, Conceptualization, Software, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Project administration, Methodology, Formal analysis.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This project was supported by the Princeton Dissertation Scholars Program, the National Scholarship Programme of the Slovak Republic, and the School of International Service, American University.

Acknowledgments

I am deeply grateful to Michelle Egan for her guidance and support as my dissertation advisor. I also thank Agustina Giraudy, Alexandria Wilson-McDonald, Carl LeVan, Cathy Schneider, Frieder Dengler, Grace Benson, Holona Ochs, James Bryan, Kristoffer Rees, Megan DeTura, Nichole Grossman, Yang Zhang, Jaclyn Fox, and two reviewers for their valuable feedback. I am grateful to Comenius University for providing an intellectual home during fieldwork, and to Jan Vachal for his excellent research assistance.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. ChatGPT (GPT-4o) was used for proofreading and language editing.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

Views presented in this article are those of the author, and do not represent the official policy or position of the Iacocca International Internship Program, Iacocca Institute, or Lehigh University.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2025.1640976/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^The primary unit of analysis in this study is the anti-populist social movement(s) operating within each country during the specified timeframe. While the broader cases are countries, the focus is on examining the characteristics, strategies, and outcomes of the major movement(s).

References

aHang (2022). A madár azért énekel, mert van egy dala [The bird sings because it has a song]. Available online at: https://ahang.hu/a-madar-azert-enekel-mert-van-egy-dala/ (Accessed: June 4, 2025).

Alecci, S. (2021). Czech prime minister secretly bought lavish French Riviera estate using offshore companies. The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. Available online at: https://www.icij.org/investigations/pandora-papers/czech-prime-minister-andrej-babis-french-property/ (Accessed: June 4, 2025).