- 1Instituto Superior de Ciencias Sociais e Politicas da Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal

- 2Centro Cientifico e Cultural de Macau, Lisbon, Portugal

- 3Sciences Po, Paris, France

This article presents a scoping review of 64 publications on gastrodiplomacy, a growing subfield within diplomatic studies that explores the strategic use of national cuisine as a tool for public and cultural diplomacy. Building on foundational literature and recent empirical studies, the review maps the conceptual, methodological, and thematic developments of gastrodiplomacy research over the past two decades. The analysis reveals a growing scholarly consensus around the field’s core elements—strategic objectives, operative agents, and mechanisms of influence—while also highlighting a strong geographic and economic bias toward developing countries in Asia. Although most existing studies emphasize national-level campaigns led by state actors, an emerging body of work now focuses on sub-state and non-state actors such as diaspora communities, chefs, and influencers. The study identifies three future research directions: methodological diversification through primary data and micro-level analysis; expanded geographic scope beyond Asia and small/middle powers; and the incorporation of critical perspectives. By offering a comprehensive review focused exclusively on the concept of gastrodiplomacy, this article contributes to the consolidation of the field and provides a foundation for further theoretical, comparative and impact-based research.

1 Introduction

“I believe that the act of eating cross-culturally can be a way of developing intimacy with others—a kind of friendship-making” (Heldke, 2003, p. 15).

The growing appreciation of gastronomy as an instrument of public diplomacy has drawn significant international attention in recent years, fueled by initiatives from countries such as Thailand, Japan, and South Korea. Indeed, food has always played a role in interpersonal, communal, and now international relations. From Zhou Enlai’s “roast duck diplomacy” to the luncheon between Trump and Kim Jong Un, food, regardless of time and place, carries the power to reconcile and harmonize tense relationships, as eating is, above all, a fundamental human activity. Gastrodiplomacy, in this sense, extends the diplomatic function of food from official interactions to the public domain, involving the international promotion of food with the purpose of fostering closer relations with foreign audiences.

Since the first journalistic report on the Global Thai program in 2002, numerous blog posts and exploratory commentaries have emerged on relevant platforms such as the USC Center on Public Diplomacy and HuffPost. Although these writings lack scientific rigor, they have provided an important foundation for subsequent research. Opinion articles and online texts by figures such as Paul Rockower and Sam Chapple-Sokol, for instance, remain widely cited and analyzed.

More than two decades later, there is now a substantial body of scholarly work on gastrodiplomacy, particularly using case study approaches that examine initiatives by countries such as Thailand, Taiwan (China), South Korea, and Peru. Among this literature, two systematic reviews stand out. White et al. (2019) conducted the first systematic literature review in this field, offering insights into levels of analysis, methodological approaches, and academic disciplines. Despite its merits, this review primarily focused on the intersection between tourism and international gastronomic promotion rather than on the core concept itself. More recently, Muljabar (2024) conducted a review based solely on Indonesian scholarship to reflect local research trends.

Although both works make valuable contributions, they lack a systematic analysis centered specifically on the concept of gastrodiplomacy, including its definition, theoretical underpinnings, recurring methods, and key actors. This highlights the need for a new, comprehensive systematic review that encompasses the full scope of international scholarly production on this continually developing yet still fragmented topic.

This study thus seeks to answer the following research question: What are the main characteristics of academic research on gastrodiplomacy over the past two decades, as identified in the existing literature? The specific objectives are to synthesize the state of the art in the field, provide an overview of current research, and explore directions for future inquiry.

To this end, we conducted a scoping review—the most suitable approach for systematically and comprehensively mapping an emerging and underdeveloped research field—comprising 64 selected studies. The review process was carried out independently by two reviewers. To ensure credibility and replicability, detailed information about the methodological decisions is provided in Section 3 of this paper.

The article is organized into five main sections: the introduction; a brief conceptual discussion of gastrodiplomacy; the methodology, which outlines the review process; the presentation and analysis of results and recommendations for future research and a final section with conclusions.

2 Gastrodiplomacy: a way to win hearts and minds

There is a long history of food serving not only human survival but also political purposes. In ancient China, elaborate gastronomic banquets were common in diplomatic settings, demonstrating the host’s hospitality, respect, and friendly disposition. For example, during the Tang and Qing dynasties, imperial feasts for foreign envoys were meticulously curated in terms of dish presentation, rare ingredients, and ceremonial service. These elements were carefully designed to showcase China’s cultural richness and sophistication while asserting its political power. In this way, food functioned as a symbolic language that facilitated diplomatic dialogue and strengthened foreign relations.

In 2002, the Thai government recognized that the value of its cuisine extended beyond official channels. Capitalizing on the international popularity of Thai food, it launched the Global Thai program with the aim of promoting national cuisine abroad to attract more international tourists, boost food-related industries, and ultimately strengthen civil-level international relations (The Economist, 2002). Inspired by Thailand’s actions, the same report coined the term “gastrodiplomacy” to describe the international promotion of food for economic and political purposes.

Several related terms, such as “culinary diplomacy” and “food diplomacy,” reflect different roles that food plays in international relations and should be distinguished. Chapple-Sokol (2013) attempted to position gastrodiplomacy as one of two levels within culinary diplomacy; however, this framework was not widely adopted within the gastrodiplomatic community. While gastrodiplomacy focuses on promoting cuisine to foreign publics, culinary diplomacy refers to high-level official meals. In other words, the distinction parallels that between public diplomacy (gastrodiplomacy) and traditional diplomacy (culinary diplomacy) (Rockower, 2020). In contrast, food diplomacy generally refers to international food aid during humanitarian crises.

Following Thailand’s lead, countries such as Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, and Taiwan have developed similar programs. Unlike other cultural diplomacy events where food plays only a supporting role, gastrodiplomacy places food and its associated culture at the center. In gastrodiplomatic campaigns, other cultural resources such as music, television dramas, and dance revolve around food. For instance, at the Night Market event in London, the tasting of Malaysian cuisine was accompanied by concerts and other performances by Malaysian artists (Travel Daily News, 2012).

The relevance of gastronomy in public diplomacy lies both in its social significance and the constructivist nature of international relations. First, eating reinforces interpersonal bonds and connection to the food’s country of origin. According to Chapple-Sokol (2013) and Spence (2016), eating becomes more than a basic need when practiced collectively, creating shared experiences. Restaurants also provide a welcoming environment for conversation. When it comes to foreign cuisine, they offer a direct opportunity to encounter another culture, often prompting broader discussion of the host country. Second, food is relatively neutral, containing fewer political or ideological elements than other cultural forms such as film, opera, or literature. When asked about the political role of gastronomy, Rockower argues that its less political nature contributes to its diplomatic potential: “A good public diplomacy is making something foreign familiar and not everything has to do with politics directly” (Rockower, apud Li, 2024a, p. 58). Through the appreciation of foreign cuisine, audiences come into closer contact with the culture and possibly other dimensions of the promoting country, leading to more tolerant attitudes. In democratic contexts, such people-to-people connections can positively influence official relations, as public opinion can shape policy. For example, the international popularity of sushi, particularly sashimi, is said to reduce global criticism of Japan’s overfishing policies (Reynolds, 2012).

Studies on gastrodiplomacy are marked by their interdisciplinary nature. Food is a research object in fields such as International Relations, Business, Communication, and Anthropology, meaning that gastrodiplomacy benefits from a broad theoretical, conceptual, and methodological base, as shown in our literature review (Section 4). However, without coordinated integration of these fields, gastrodiplomacy risks becoming fragmented, with an abundance of research lacking depth. In other words, each discipline may treat the topic in isolation, without contributing to a unified field of study. Public and cultural diplomacy—the two conceptual pillars of gastrodiplomacy—are themselves underdeveloped due to a lack of theoretical grounding and conceptual clarity (Clarke, 2020).

Given the significant number of empirical studies, especially case studies, it is now timely to systematically synthesize the existing literature on gastrodiplomacy, with particular focus on definitions, theoretical frameworks, methodologies, studied countries, and related themes.

3 Research methods

Literature review is a fundamental step for scientific advancement, as it serves two primary purposes: summarizing previous knowledge and indicating directions for future research. In addition to being part of a larger research project, literature reviews, especially in their systematic form, may also be conducted as stand-alone pieces, provided they follow rigorous scientific standards and offer original value to the relevant field. Since the late 20th century, with the rise of evidence-based research in the social sciences, systematic literature reviews began to be imported from the Health Sciences to improve the quality and credibility of traditional reviews, which essentially involve assembling a puzzle of existing information and arguments.

To gain a deeper understanding of the current knowledge on gastrodiplomacy, a systematic literature review was conducted for this study. According to Xiao and Watson (2019), there is no single unified approach to systematic literature reviews; the choice depends primarily on the objective of the review itself. In the case of gastrodiplomacy, which is still a relatively new and fragmented area within diplomatic studies, there is a clear need to systematically summarize the existing knowledge. Empirically, there are still few publications in top-tier international relations or related journals. Therefore, in order to map the field and identify neglected themes, a scoping review was selected as the primary method, along with a mainly narrative analysis based on the evidence gathered from the included literature.

A scoping review, as defined by Mays et al. (2001), p. 194, “aims to map rapidly the key concepts underpinning a research area and the main sources and types of evidence available and can be undertaken as stand-alone projects in their own right, especially where an area is complex or has not been reviewed comprehensively before.” While sharing tools with systematic reviews, scoping reviews emphasize breadth over depth and quality. In a stricter sense, a systematic literature review aims to answer a highly specific micro-level question using a small number of carefully filtered sources of high quality. Consequently, its applicability is limited to mature fields that possess strong theoretical and conceptual foundations and sufficient case studies for generalization. Scoping reviews, on the other hand, aim to provide a comprehensive overview of the field in question. Despite not focusing on the quality of the literature reviewed, scoping reviews still qualify as a form of systematic literature review in a broader sense for two reasons. First, scoping reviews, like all forms of scientific research, follow a logical, transparent, and rigorous research design. Second, in response to concerns about potential bias in the review process, the scoping review can employ cross-checking by two independent reviewers. Accordingly, the main purpose of this research is not to examine in detail or provide definitive answers to highly specific questions about gastrodiplomacy, but rather to offer a global overview of the work conducted to date in this field and, subsequently, to characterize the prevailing research trends.

In this study, the three fundamental values for scientific review—validity, credibility, and reproducibility—are upheld throughout the processes of collecting, evaluating, and presenting data (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005; Xiao and Watson, 2019). This review was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR), as proposed by Tricco et al. (2018).

The review protocol consists of six main stages: formulation of the research question, identification, screening and inclusion of the sample, extraction of relevant data, and charting and analysis of the data.

3.1 Formulation of the research question

As stated in the Introduction, the research question and objectives arose from the lack of a solid foundation and the absence of a systematic review on existing work in gastrodiplomacy.

3.2 Identification

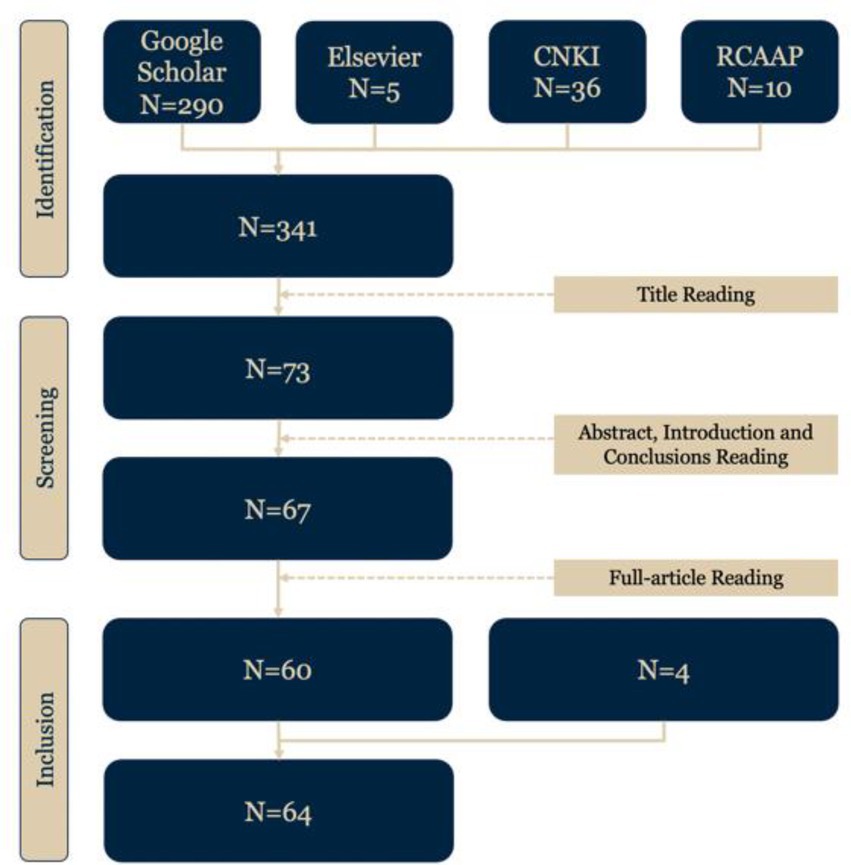

Three criteria were established for the initial literature search. First, regarding the timeframe, only publications from 2002 to 2024 were considered—2002 being the year the first known text on gastrodiplomacy appeared, and 2024 being the most recent full year prior to this research. The search was conducted across four digital platforms: Google Scholar, Elsevier, RCAAP (Open Access Scientific Repository of Portugal), and CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure). Six keywords were used: “gastrodiplomacy,” “gastro-diplomacy,” and “culinary diplomacy,” along with their Portuguese (“gastrodiplomacia,” “gastro-diplomacia,” and “diplomacia culinária”) and Chinese translations (美食外交, 美食剬共外交, and 胃肠外交). Following these criteria, the initial search was conducted on June 9, 2025, yielding a total of 341 results (Figure 1).

3.3 Screening

For practical purposes, three filters were applied to manage the sample. First, although scoping reviews do not intend to assess the quality of each selected text, controlling the type of publication ensures the review reflects the field’s consensus and cutting-edge research. Acceptable sources included peer-reviewed journal articles, books, and book chapters, while other types such as conference abstracts and working papers were excluded. Second, in terms of language, English, Portuguese, and Chinese were considered—leveraging the authors’ multilingual capabilities for broader coverage. Third, duplicate publications were naturally removed. This screening excluded 268 documents, leaving 73 for further evaluation.

A subsequent screening was conducted to identify research explicitly focused on the use of food as a public diplomacy tool for enhancing national soft power. In other words, studies that concentrated on the use of food in official or elite settings were excluded. This screening involved reading the abstracts, introductions, and conclusions of the remaining 73 texts, which led to the exclusion of an additional six documents.

3.4 Inclusion

Applying the same criteria, a further seven documents were excluded after the full-text review, resulting in a final set of 60 texts. Additionally, a backward search through the reference lists of the included works yielded four items of grey literature. These comprised: a 2002 report from The Economist, which first coined the term “gastrodiplomacy”; two opinion pieces by Rockower (2010a) and Rockower (2010b) analyzing gastrodiplomacy cases from Thailand, South Korea, and Taiwan, and providing an informative foundation for subsequent scholarly work; and one blog post by Sam Chapple-Sokol (2016), in which the author critically re-examined the earlier theoretical foundations of gastrodiplomacy. The final sample thus comprised 64 relevant sources.

3.5 Data extraction

Based on the research question and objectives, seven inductively derived indicators were defined after an initial full reading of the included texts. These indicators are: number of publications per year; conceptual definitions; key concepts and theories used in gastrodiplomacy research; applied research methods; frequency of initiating countries; frequency of target countries; and other recurring themes. Although the indicators in question may not be exhaustive, they encompass three fundamental dimensions for the formulation of an academic concept: definition, theoretical framework, and methodological approach. Following this, a second full reading was conducted, and data were extracted and coded using Notion software.

3.6 Charting and analysis

Except for definitions of gastrodiplomacy – analyzed via word frequency using Voyant Tools – all other quantifiable data were visualized using Excel and PowerPoint. Based on these review results, an analytical interpretation follows in the next section.

Steps 2 through 5 were conducted simultaneously but independently by both authors between June 10 and 16, 2025, to mitigate potential personal bias. Once the inclusion criteria, screening, and data extraction methods were finalized, the reviewers compared and cross-checked their results. Any discrepancies were discussed and resolved. The protocol described above represents the final agreed version.

It must be acknowledged that all methodological approaches have inherent limitations. In the case of scoping reviews, the absence of a systematic focus on scientific quality may compromise overall rigor and the validity of conclusions. Moreover, scoping reviews are not designed to address highly specific research questions within the field under examination, as their primary aim is to map the broader landscape of the discipline rather than to analyze a single, narrowly defined aspect. Nevertheless, given that gastrodiplomacy remains an emerging field lacking a robust foundational framework, the need for an initial mapping exercise justifies the use of a scoping review. Such a comprehensive overview can provide the necessary groundwork for conducting a more rigorous systematic literature review in future research.

4 Findings and discussion

4.1 Findings

This section presents the results—organized according to the seven indicators used in the data extraction process—which form the empirical basis for the subsequent discussion.

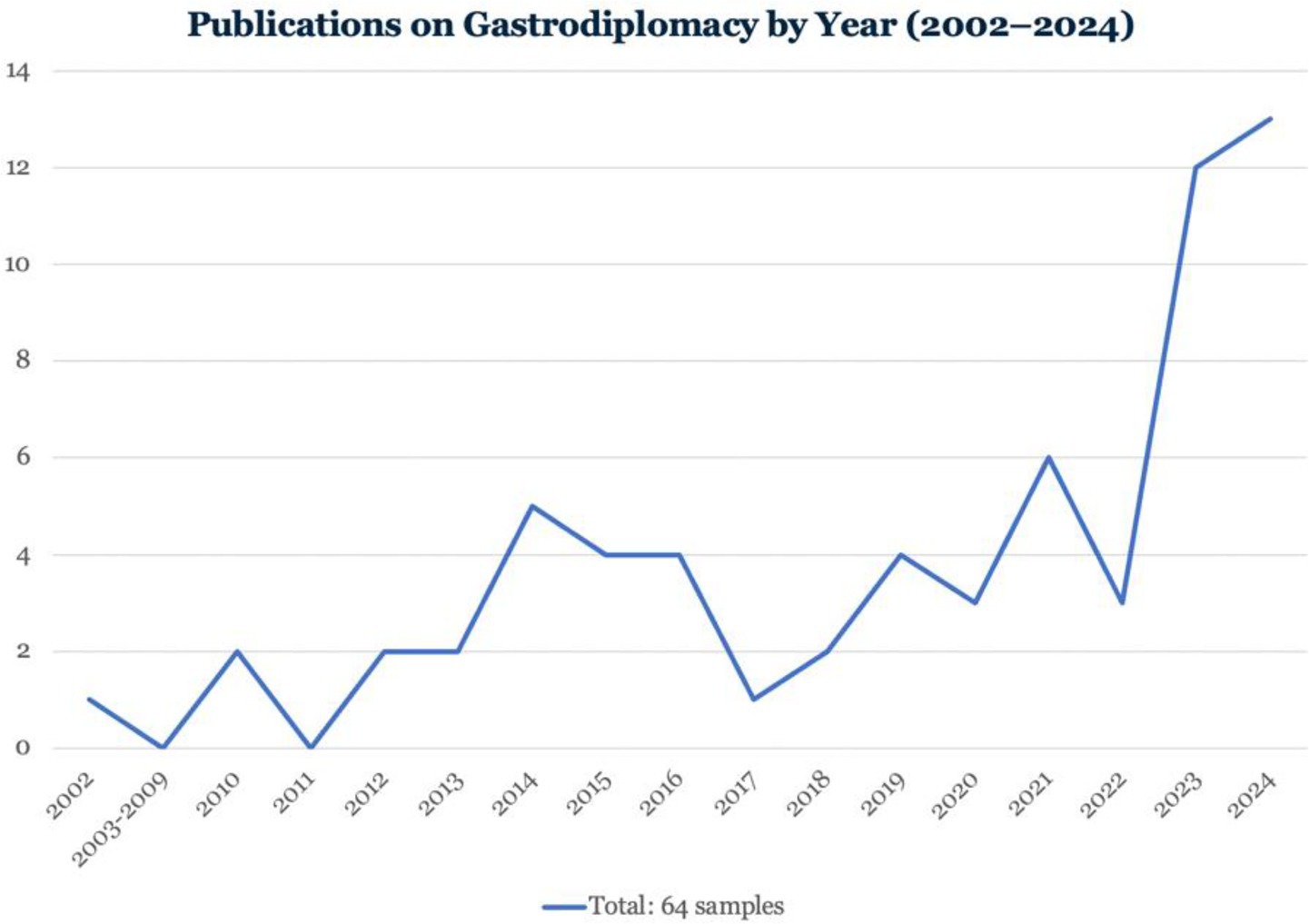

First, regarding the annual number of publications on gastrodiplomacy, the overall trend shows a steady quantitative increase (Figure 2). After the first mention in 2002, there was a period of nearly 10 years during which the academic community paid little attention to this emerging tool of public diplomacy. Until 2012, references were mostly limited to blogs and opinion pieces. Starting in 2013, the annual number of publications has consistently reached at least three, with the exception of 2017. The largest spike occurred in 2023 with 12 publications, followed by 13 in 2024.

Second, regarding the definition of the term, 5 out of the 64 sources did not provide an explicit definition of gastrodiplomacy. Therefore, this dimension was analyzed based on the remaining 59 texts that did offer a clear conceptualization. Definition-related excerpts were extracted, compiled, and processed using Voyant Tools—a widely used application for text analysis and interpretation—to identify the most common conceptual components and the degree of consensus. As shown in Figure 3, the most frequent terms were “food” (33 occurrences), “diplomacy” (28), “cultural” (24), “public” (16), and “culinary” (16). These five highly used words point to three widely agreed yet basic dimensions of the concept of gastrodiplomacy: the use of “food” (or “culinary,” as a cultural means) as the central tool; the broader diplomatic context in which gastrodiplomacy operates; and the primary target of this new diplomatic activity (the public). The definition by Rockower (2012), p. 235—“Gastrodiplomacy is the act of winning hearts and minds through stomachs”—is the most frequently cited when authors did not formulate their own definitions. His name appears ten times across the 59 documents analyzed, which also justifies our inclusion of two grey literature sources by the same author.

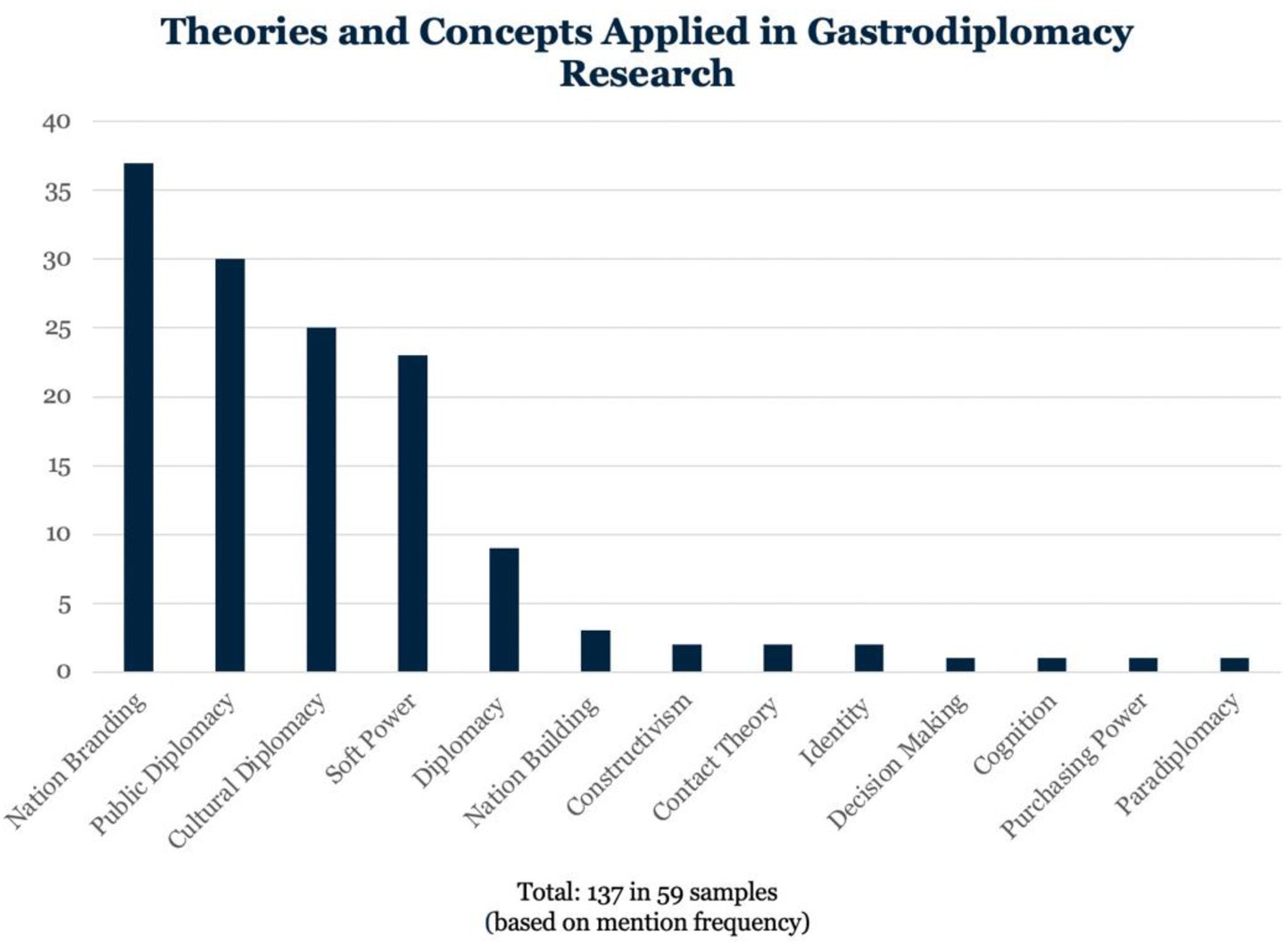

Third, in terms of theoretical and conceptual frameworks, 59 of the 64 texts included provided an explicit foundation for their discussion of gastrodiplomacy. As each text may draw on more than one theory or concept, the analysis is based on total reference frequency. As shown in Figure 4, the five most frequently used concepts are Nation Branding (37 mentions), Public Diplomacy (30), Cultural Diplomacy (25), Soft Power (23), and Diplomacy in a general sense (9). Additional, less frequent references include theories from outside diplomatic studies, such as Contact Theory, Decision-making Theory, and Purchasing Power, highlighting the interdisciplinary nature of the field. Regarding the basic theories of International Relations, only the constructivist school was mentioned, and only twice.

Figure 4. Theories and concepts applied in gastrodiplomacy research. Source: prepared by the authors.

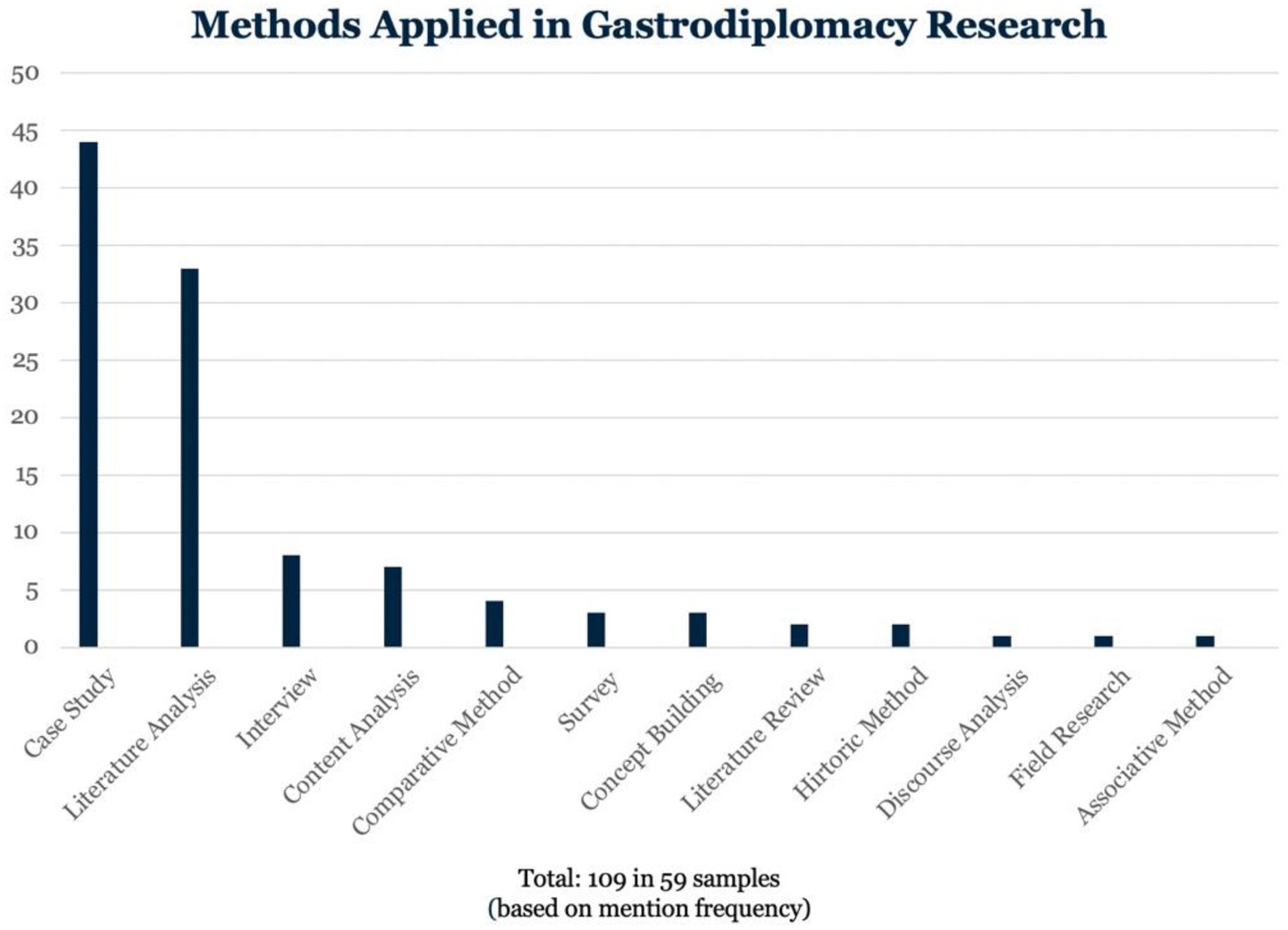

Fourth, concerning research methodology, 59 out of 64 texts explicitly stated their methods. As with theoretical frameworks, the analysis was based on total frequency. Altogether, 109 methodological instances were recorded in the 59 texts. As shown in Figure 5, the most commonly used methods were case study and literature analysis (referring to secondary data sources such as previous studies and media reports). Other techniques, including interviews, content analysis, and discourse analysis, appeared less frequently—each used fewer than ten times.

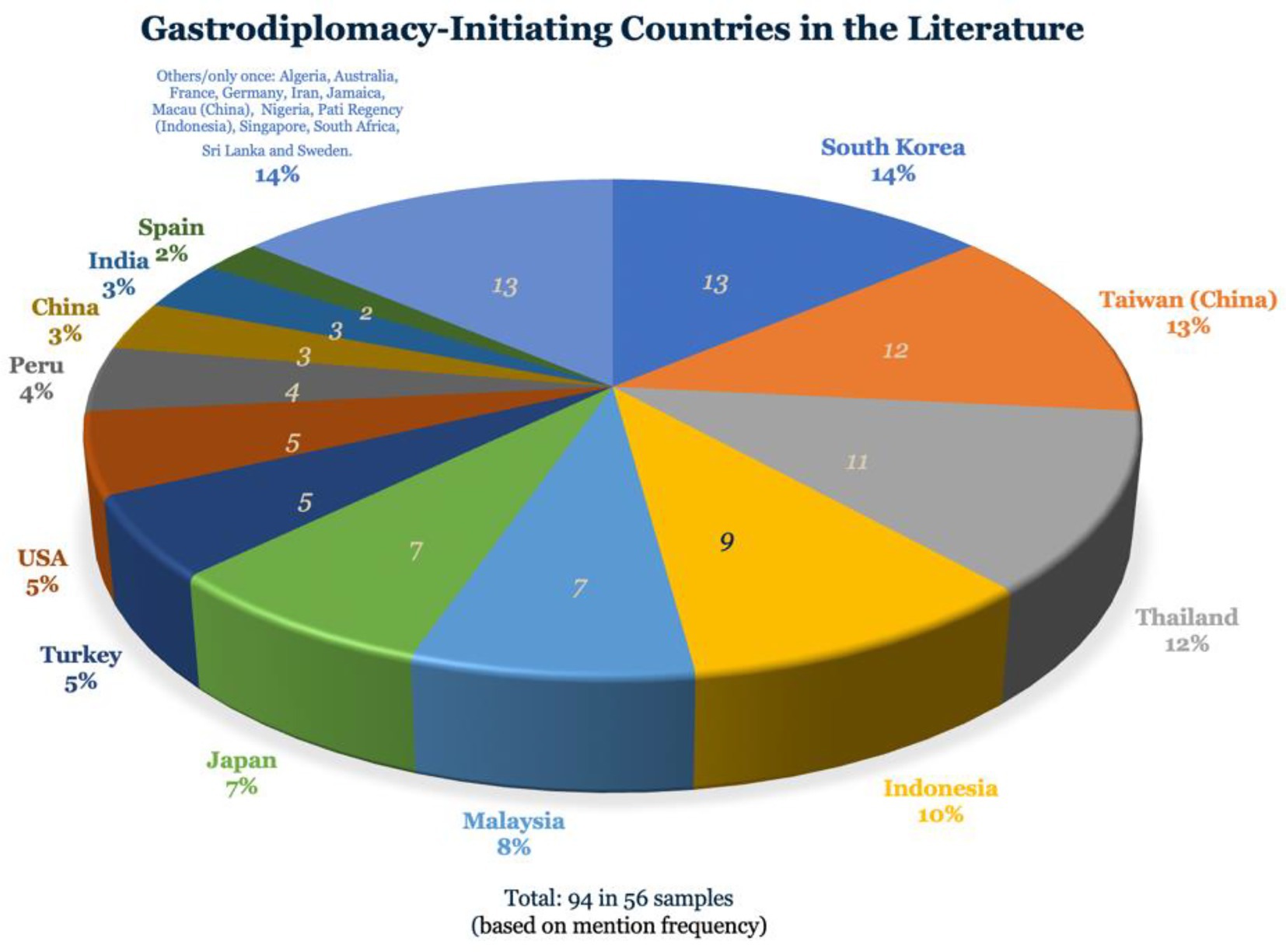

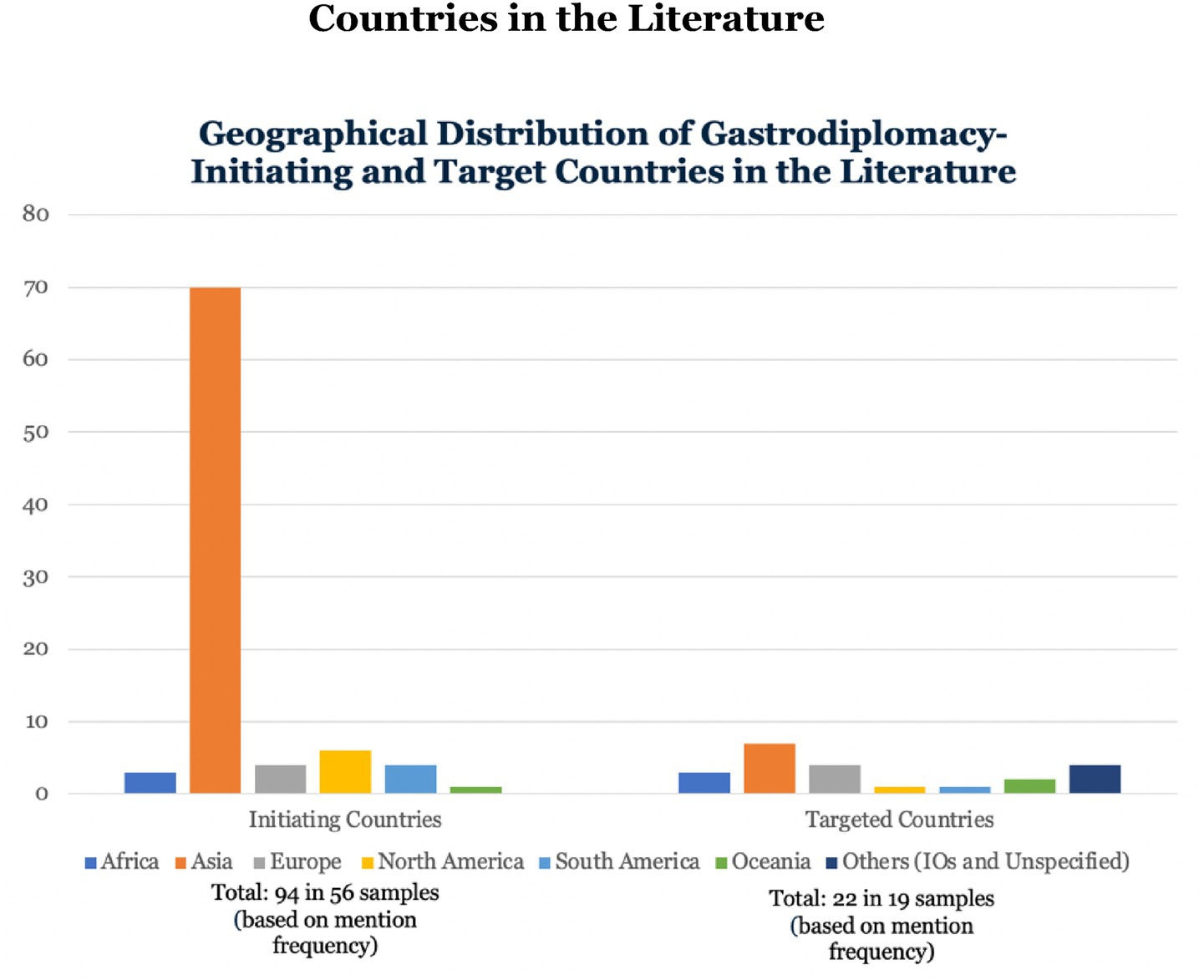

Fifth, regarding the initiating countries of gastrodiplomatic campaigns, 56 texts explicitly analyzed gastrodiplomatic projects, totaling 94 country-references – some countries being mentioned more than once (Figure 6). The six most frequently analyzed countries are all in Asia, namely South Korea (13 mentions), Taiwan (12), Thailand (11), Indonesia (9), Malaysia (7), and Japan (7). Other countries, although less frequently referenced, appeared more than once, including Turkey (5), the United States (5), Peru (4), China (3), India (3), and Spain (2). Several others—such as Australia, France, and South Africa—were discussed only once. Beyond national-level cases, some studies also addressed subnational entities, notably the Macau Special Administrative Region of China and Peti Regency in Indonesia.

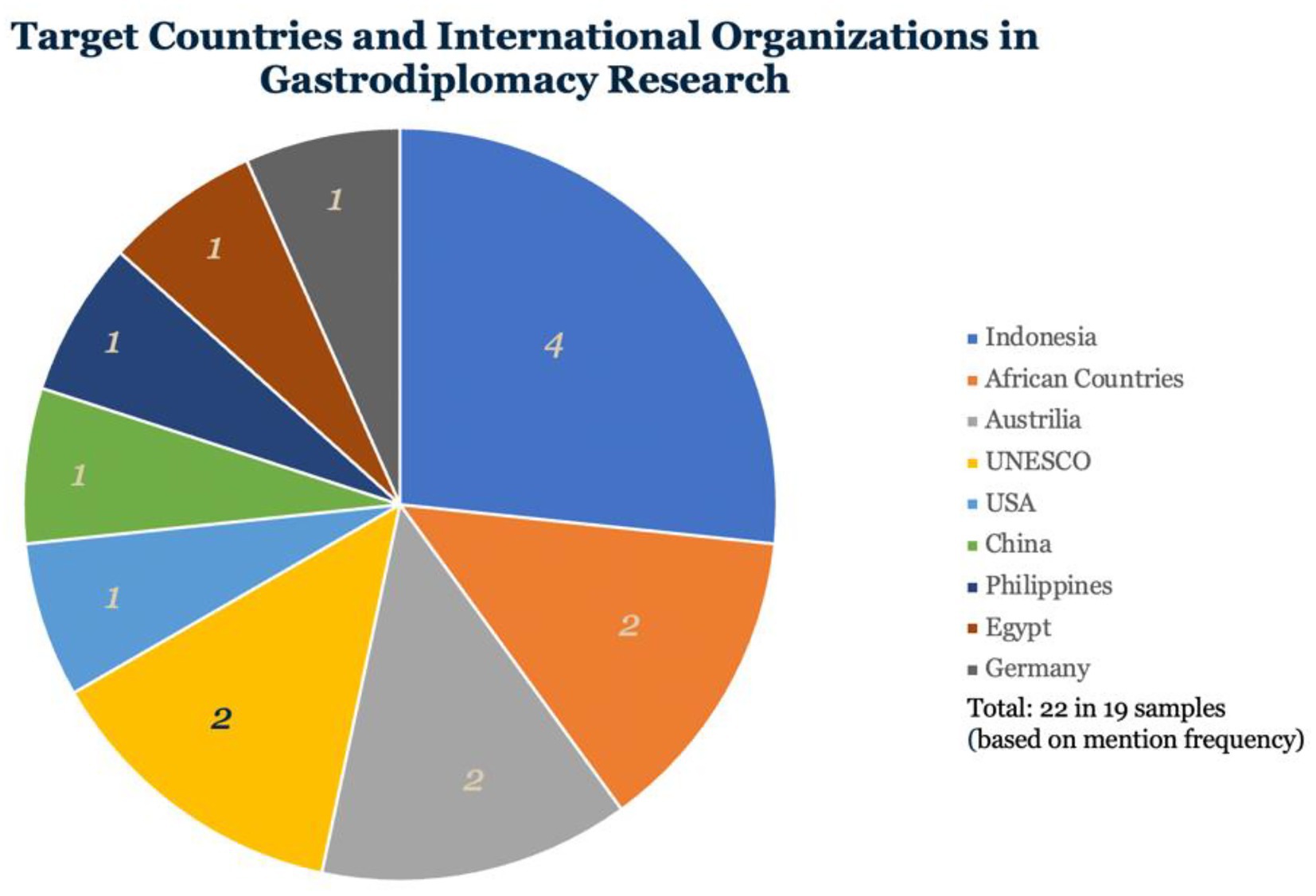

Sixth, regarding target countries – those that receive gastrodiplomatic campaigns – only 19 of the 64 studies included explicit analysis of this dimension. Given that some studies addressed multiple destinations, a total of 22 target cases were identified (Figure 7). Among them were non-traditional international actors like UNESCO (2 cases), and integrated regional approaches such as the collective study of African countries (2 cases). The remaining cases were focused on individual national contexts, including Indonesia (4), Australia (2), the United States (1), China (1), the Philippines (1), Egypt (1), and Germany (1).

Figure 7. Target countries and international organizations in gastrodiplomacy research. Source: prepared by the authors.

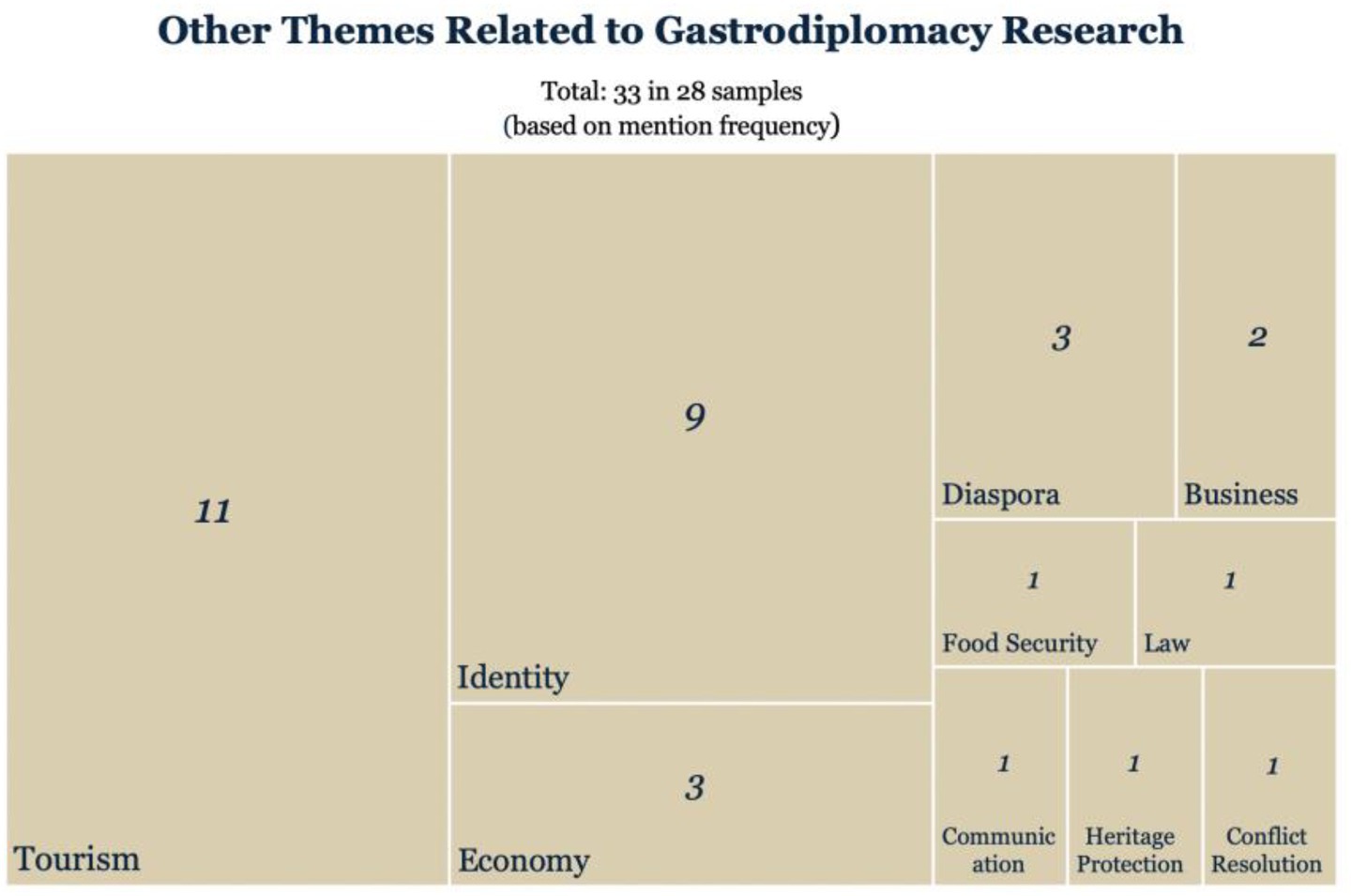

Finally, 28 of the analyzed texts integrated gastrodiplomacy with other significant themes, indicating a more organic and interdisciplinary approach to the study of food and international relations. As shown in Figure 8, topics frequently connected to gastrodiplomacy include tourism, identity, economy, diaspora, business, food security, law, communication, heritage protection, and conflict resolution. Among these, tourism is particularly prominent, as local cuisine is an integral part of travel experiences. This link is exemplified by the early Global Thai campaign, which explicitly sought to promote tourism through culinary outreach.

4.2 Discussion

Based on the results of the review, this subsection aims to characterize the field of gastrodiplomacy through the existing literature and to propose, in a reflective manner, interesting and important directions for future research.

Regarding its characteristics, first, gray literature constitutes relevant initial steps for scientific work on gastrodiplomacy. The quantity of publications is divided into two phases: before 2012 and after 2012. According to Figure 2, prior to 2012, there are few works on gastrodiplomacy, and the gray literature—such as blogs and online opinion pieces studying gastrodiplomatic programs of specific countries—comprise the only materials from that period. Following a 2002 report by The Economist, Paul Rockower, representing the USC Public Diplomacy Center, and Sam Chapple-Sokol, an editor and author of food-related texts, contributed relevant—although mainly non-scientific—works to the field, which continue to be frequently cited today. According to the word frequency analysis in Figure 3, for example, it is clear that Paul Rockower’s definition is employed in various subsequent works. Building on these initial case-study explorations, a significant leap for the field was Chapple-Sokol’s (2013) work, which combined and analyzed the most applied concepts in current research—nation branding, public diplomacy, and soft power.

Due to these pragmatic and conceptual foundations, since 2013, there has been a steady annual increase in publications, with over three papers per year, except for 2017 and 2018. In 2023, the number of annual publications surged from 2 to 12. This more significant development since the term’s creation mainly results from efforts by Indonesian academia. In 2017, the first center dedicated exclusively to gastrodiplomacy studies was established at Jember University, and in 2022, gastrodiplomacy became one of two branches in the International Relations undergraduate program at the same institution. Starting in 2023, most – 14 out of 25 – publications were produced by Indonesian researchers in the field.

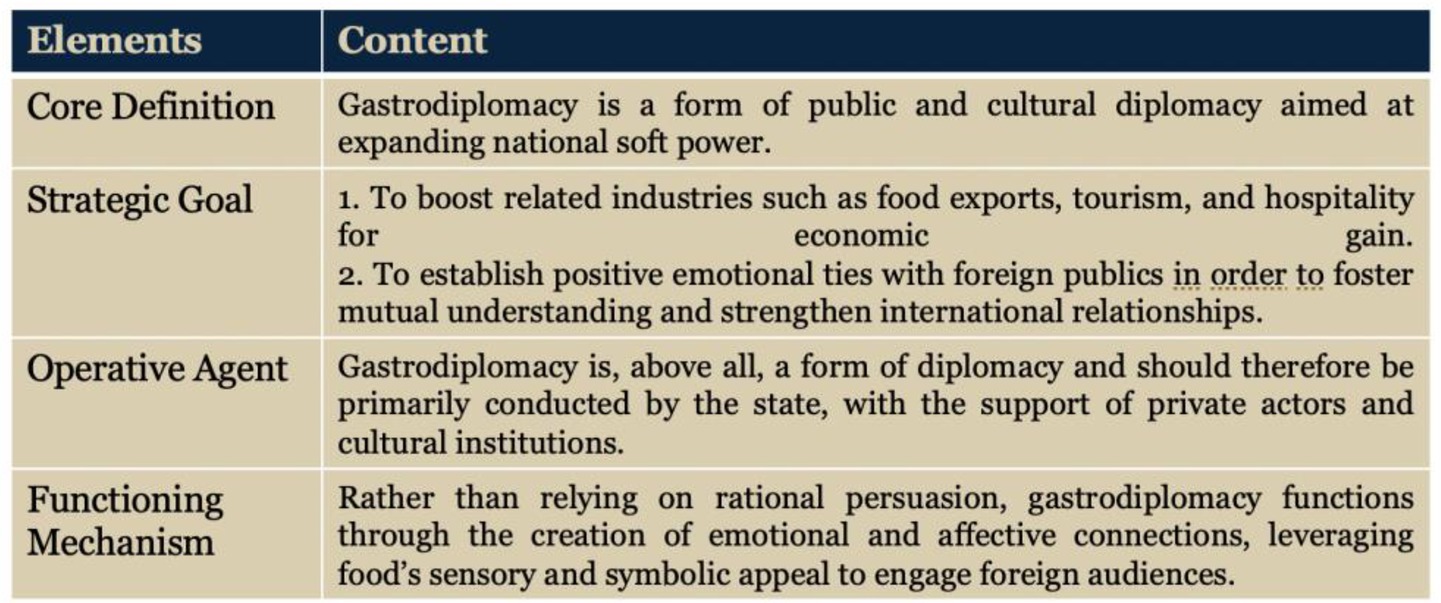

Second, despite the existence of numerous definitions of the term – which largely reflect semantic variations – the fundamental elements of gastrodiplomacy are consensual among scholars, including its strategic goals, operative agents, and functioning mechanisms (Figure 9). On the one hand, as shown in Figure 3, words such as “food,” “culinary,” and “gastronomy” are frequently used interchangeably, reflecting some confusion between gastrodiplomacy and culinary diplomacy. However, this lexical confusion stems from different understandings of the same subject of study, since gastrodiplomacy, or the various terms preferred by each researcher, focuses on food as a tool of public and cultural diplomacy and a means of international promotion for a country, which becomes evident in the applied concepts.

Figure 9. The concept of gastrodiplomacy: definition and key elements. Source: prepared by the authors.

Regarding the goals of this public diplomacy tool, The Economist (2002) report explicitly states that the Global Thai program brings economic benefits, especially in the export and tourism sectors. Diplomatically, the Thai program can also “subtly help to deepen relations with other countries” (The Economist, 2002), which has been artistically summarized as a way to “win hearts and minds” (Chapple-Sokol, 2013; Rockower, 2020). Concerning agents, gastrodiplomacy – despite the apolitical nature of food – is a diplomatic activity in which the state continues to play a central role. As Li (2024b) argues, only the state has the power to design a large national gastrodiplomatic project and the financial and human resources to support it. However, in a context where new civil society actors—such as companies, recognized individuals, and civic associations—also begin to occupy important roles in public diplomacy (Melissen, 2015), the subtle management of relations between official and civil actors becomes a key task for policymakers and academics alike. While the state defines the objectives, targets, and other components of the gastrodiplomatic project, its realization does not occur without collaboration and support from other agents such as the national diaspora abroad, internet influencers, recognized chefs, among others. Currently, most works focus on macro-level policy analyses defined in the programs; however, since 2022, micro-level studies adopting a bottom-up approach have emerged, examining gastrodiplomacy in practice with a focus on implementing agents. For example, Octastefani and Kusuma (2022) argue that the diaspora—especially emigrants who run food businesses—constitutes an important channel for Taiwan’s gastrodiplomacy. Yayusman et al. (2023) and Yayusman and Mulyasari (2024) follow the same research line and highlight the importance of Indonesian communities in promoting their national cuisine.

Regarding the theoretical foundation, according to the data in Figure 4, there are theories and concepts from various fields applied to studies on gastrodiplomacy. However, Nation Branding, Public Diplomacy, Cultural Diplomacy, and Soft Power are the four most frequently mentioned (each with a frequency above 20, while the others are always below ten). The simultaneous use of these four approaches is not an overlap but rather an organic interconnection, since each one supports a specific dimension of gastrodiplomacy. Gastronomy—both food itself and the art of preparing it—is a cultural resource and therefore falls within the scope of cultural diplomacy. Public diplomacy, in turn, emphasizes that gastrodiplomacy takes place in a contemporary world where the power of influence is recognized as belonging to the people rather than solely to elites, as in an era when diplomacy and international relations were decided behind closed doors. As for nation branding and soft power, both concepts focus on the intended outcomes of gastrodiplomacy, with the former referring more to the economic sphere and the latter demonstrating a more political nature.

Unlike traditional diplomacy, which depends on negotiations or, in some cases, political coercion, gastrodiplomacy aims to engage foreign publics through emotional and affective connections fostered by their appreciation of the initiating country’s cuisine. This is why the term soft power, as defined by Nye (2004), is frequently referenced in gastrodiplomacy research (Figure 4). Unlike the coercion or seduction exercised by hard power, gastronomy is essentially a cultural resource aimed at increasing national soft power through attraction and the creation of close relationships. Therefore, although authors vary in how they phrase the concept of gastrodiplomacy, the results of the Voyant analysis (see Figures 3, 9). show that its central tool, academic foundations, objectives, agents, target audiences, and functioning mechanisms remain consistent. This allows the concept to be summarized as follows: Gastrodiplomacy is a form of cultural diplomacy that uses the appeal of food to expand a nation’s soft power among foreign publics, with the aim of achieving economic, political, and other related benefits.

Third, methodologically, there is a lack of scientific rigor in existing studies. This lack of scientificity is understandable in the early works, given the nascent state of the field and the urgent need for diverse perspectives. However, literature analysis remains a widely, and sometimes the only, used technique (Figure 5). Without primary data or clear research design, these studies analyze gastrodiplomatic campaigns based on secondary sources such as previous research or online information, employing descriptive and narrative approaches. The value of descriptive research should not be dismissed, as it plays an important role in the early stages of a field’s development. However, in the case of gastrodiplomacy, this initial phase should have now been surpassed. Yet, several recent studies continue to offer largely repetitive information of gastrodiplomatic initiatives from Thailand and Taiwan, without introducing fresh perspectives or insights to advance the field (Lipscomb, 2019; Putri and Baskoro, 2023; Tholhah and Wafa, 2024).

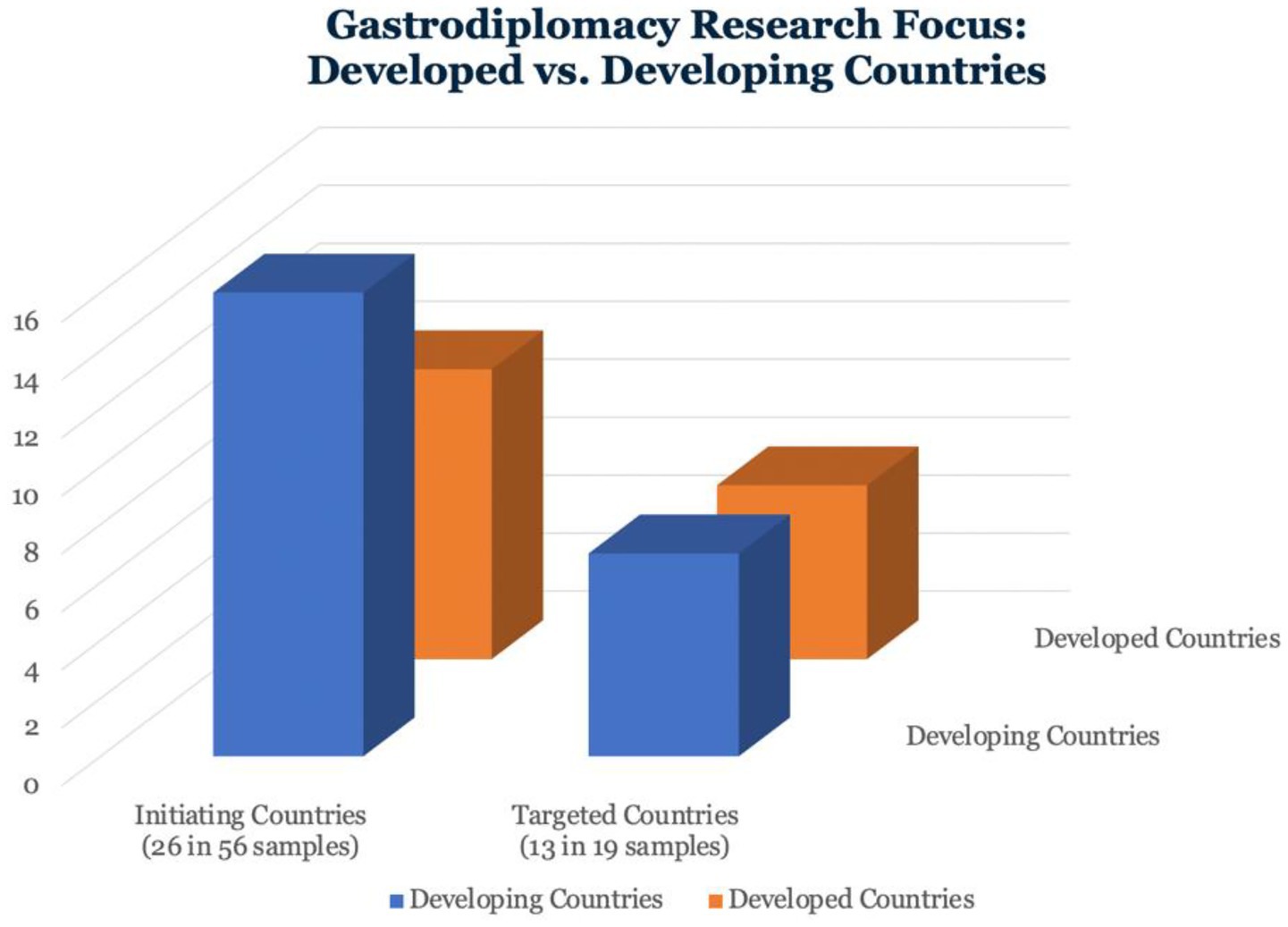

Fourth, regarding geographical distribution and economic development, initiating countries are mainly developing countries located in Asia. Based on the results in Figure 6, countries with gastrodiplomatic programs were categorized according to geographic location, with 70 of 94 analyzed cases being Asian countries. The combined total of cases from other continents – North America (6), Europe (4), South America (4), Africa (3), and Oceania (1) – amounts to approximately only one-third of the Asian cases (24/70) (Figure 10). The same categorization was made according to economic development level, as defined by the United Nations (2024). Among the 26 countries related developed (Figure 11).

Figure 10. Geographical distribution of gastrodiplomacy-initiating and target countries in the literature. Source: prepared by the authors.

Regarding gastrodiplomacy target countries, a more balanced distribution is observed in terms of geography and economic development. Using the same categorization criteria, although Asian countries remain the most studied cases, the numbers are close. The variance—which measures the degree of dispersion relative to the mean—for this group of data is only 3.84 compared to 553.10 for the initiating countries. Concerning economic development level, among the 13 target countries, seven are developing countries while the remaining six are developed.

On the one hand, gastrodiplomacy is an international promotion project that started in Thailand and naturally has greater influence over its Asian neighbors. On the other hand, small and middle powers in Asia (in gastrodiplomacy studies, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, among others) prefer alternative means to increase their international presence. For countries that do not possess economic or military hegemony in the international system, other forms of soft power, such as gastrodiplomacy, are more economical and important tools. As Fox (1959), p. 2, argues, “Small states are not powerless; rather, they exercise influence in ways that differ from great powers.” For Thailand, its cuisine can reach all corners of the world where, for example, its aircraft carrier HTMS Chakri Naruebet cannot.

Regarding the two low variances in the numbers of target countries, more countries outside Asia and more developed countries are becoming targets of gastrodiplomacy campaigns, since, on the one hand, the dispersed geographic distribution demonstrates the intention of international promotion of gastrodiplomatic campaigns. On the other hand, according to Leonard et al. (2002), in all forms of public diplomacy, certain countries are prioritized as targets due to their weight in global affairs. This explains why more developed countries with greater influence on international affairs – such as the Netherlands, the United States, among others—appear as gastrodiplomacy target countries (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Gastrodiplomacy research focus: developed vs. developing countries. Source: prepared by the authors.

High-quality literature reviews do not merely summarize existing studies but critically evaluate the body of knowledge, identify research gaps, and propose avenues for future investigation (Randolph, 2009; Torraco, 2005; Webster and Watson, 2002). This approach ensures that literature reviews contribute to the advancement of the field rather than functioning as passive descriptions. In line with the preceding analysis, three key directions are proposed for the advancement of gastrodiplomacy research.

First, there is room for methodological improvement in both the techniques employed and the analytical perspectives adopted. To date, most studies have relied heavily on secondary data, resulting in repetitive, information-based outputs rather than yielding new insights that advance the field. In this regard, it is promising to note a growing use of more rigorous scientific methods—such as content analysis and discourse analysis—based on primary data in recent works (e.g., Li, 2024a; Nair, 2021; Vellycia, 2021).

Moreover, both the research objects and levels of analysis should be further diversified. Most current studies focus on national-level policies, yet other actors and platforms—such as diasporic communities, celebrity chefs, television shows, and online influencers—also play important roles in promoting national cuisine abroad. It is at this micro level that the mechanisms of gastrodiplomacy can be best observed in practice.

This shift in analytical scale also requires incorporating the perspective of target countries, as soft power is ultimately concerned not merely with the possession of resources but with the achievement of efective outcomes. To date, according to our data, the majority of studies on gastrodiplomacy (56 publications) have approached the topic from the perspective of the initiating country, emphasizing the design and implementation of gastrodiplomatic programs. In contrast, only 19 studies have examined their actual effects in target countries. For the sustainable development of this field and to enhance its credibility among policymakers, more research is needed that applies the concept from the standpoint of target audiences and establishes a comprehensive evaluation framework. This gap, as in other areas of public and cultural diplomacy, requires urgent attention. A target- and results-focused approach is essential for assessing the real impacts of gastrodiplomatic campaigns on foreign publics, including both economic benefits and attitudinal changes toward the initiating country.

Second, future research should broaden both the geographic and developmental scope of gastrodiplomacy studies. The existing literature predominantly focuses on small and middle powers in Asia for several reasons. As previously discussed, smaller states often seek alternative means to assert their presence in the international system. However, major powers such as China, France, and the United States also engage in the international promotion of their cuisines – often in spontaneous or decentralized ways. As Li (2025) notes, despite the absence of a formal national gastrodiplomacy program, China exhibits forms of spontaneous gastrodiplomacy through the activities of overseas Chinese communities and regional governments operating via paradiplomatic channels. Such non-centralized initiatives warrant scholarly attention, since in public diplomacy it is not the degree of central coordination that matters most, but the impact achieved.

In addition, the natural conditions in much of Asia – particularly in East, South, and Southeast Asia – foster remarkable culinary diversity due to the wide range of locally produced ingredients and species. Nonetheless, other parts of the world have also produced foods that have achieved global popularity, such as pizza (Italy), fried chicken (Southern United States), and tacos (Mexico). Therefore, the relative lack of scholarly attention to the gastrodiplomacy of more developed countries or those outside Asia should not be interpreted as evidence of its absence. More case studies featuring countries from diverse regions and levels of development are essential to introduce fresh perspectives and to test the generalizability of gastrodiplomacy as a global concept.

Third, while gastrodiplomacy has gained increasing popularity as a tool of soft power and cultural engagement, critical perspectives in the literature remain underdeveloped. A postcolonial lens invites a deeper interrogation of the cultural hierarchies embedded in state-sponsored culinary narratives – raising questions such as: Who gets to represent a nation’s cuisine? Which regional or minority food cultures are included, and which are excluded? For culturally diverse countries such as China, India, Brazil, and many others, should gastrodiplomacy be pursued as paradiplomacy – that is, at the level of regional cuisines rather than as a single national brand? The case of Peru (Wilson, 2013) offers a telling example. In the early 2000s, the country nominated “Peruvian cuisine” for inclusion on UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list, and in 2023 one of its most famous dishes, ceviche, was finally added to the candidate list. Yet questions of representation arise: why was this coastal dish (costa) selected over others from the sierra or selva regions?

In the case of Taiwan, the question of presentiveness could be even more controversial. On the one hand, Taiwan has used gastrodiplomatic initiatives to seek international recognition distinct from mainland China, as part of a broader nation-building effort in support of its independent path. On the other hand, from a cultural perspective, the majority of Taiwanese dishes – including those often claimed as symbols of Taiwanese identity, such as lurou fan (卤肉饭, braised pork rice) and niurou mian (牛肉面, beef noodle soup) – originate from, and still have equivalent versions in, mainland China. In this sense, determining which dishes have the legitimacy to symbolize a uniquely Taiwanese identity is an important issue for both policymakers and scholars in Taiwan.

Future studies should also examine the tensions between cultural exchange and cultural homogenization and assess whether gastrodiplomatic efforts genuinely foster mutual understanding or merely reproduce exoticized, commercialized and stereotypic images of the “Other.” In this regard, the case of McDonald’s in China offers a compelling example: on one hand, the brand has successfully promoted American fast-food culture and its associated lifestyle; on the other hand, despite localization efforts – including its Chinese name and flavor adaptations – McDonald’s continues to be seen as an emblem of American values (Western and capitalist) and a cultural threat to traditional Chinese cuisine, culture, and ideology (Wang, 2014; Zhang, 2006).

5 Conclusion

This study conducted a scoping review of 64 publications on gastrodiplomacy, a relatively new subfield within diplomatic studies. Through systematic coding and descriptive analysis, the findings indicate that the field has developed a reasonably coherent conceptual foundation, grounded primarily in the frameworks of nation branding, soft power, public diplomacy, and cultural diplomacy. Despite variations in terminology and definitional approaches, scholars broadly agree on the core elements of gastrodiplomacy – its strategic objectives, operational actors, and functioning mechanisms. In this respect, gastrodiplomacy can be defined as a form of public and cultural diplomacy aimed at expanding national soft power.

Importantly, gastrodiplomacy should not be seen as merely a cultural communication strategy. For small and middle powers, it constitutes an alternative modality of engaging in global affairs, particularly in contexts where economic or military means are limited. This review reveals a strong geographic and economic concentration in the literature, especially toward developing Asian countries, where state actors continue to play dominant roles. However, the increasing presence of non-state actors – including diaspora communities, celebrity chefs, and digital influencers – has become increasingly evident, particularly at the implementation level.

By offering a structured and up-to-date synthesis of the field, this study contributes to the consolidation of gastrodiplomacy as a legitimate area of inquiry and identifies avenues for further exploration. Empirically, the field remains predominantly focused on initiating countries, while little attention has been paid to the actual impact and reception of gastrodiplomatic efforts in target societies. As gastrodiplomacy continues to evolve, future research should prioritize impact evaluation, particularly from the perspective of target audiences.

Although the literature remains heavily centered on Asian contexts, other countries with notable culinary profiles – such as Brazil, France, Italy, and China – also engage in gastrodiplomacy. Comparative studies between small/middle powers and larger geopolitical players could offer valuable insights into strategic divergence and symbolic intent. Furthermore, the integration of critical perspectives, including inquiries into national identity, cultural hegemony, and symbolic representation, would enrich the theoretical depth of the field. Gastrodiplomacy scholarship must evolve beyond merely descriptive accounts toward more analytical and reflective frameworks.

While this review provides a comprehensive mapping of the field, certain limitations inherent to the scoping review methodology must be acknowledged. These include the absence of a formal quality assessment of individual sources and potential interpretive bias. However, the study implemented measures to maximize transparency, replicability, and credibility, including a clearly documented review protocol, independent coding by two researchers, and an evidence-based approach to interpretation. Unlike previous reviews in the field (White et al., 2019; Muljabar, 2024), which focused on specific themes (e.g., gastrodiplomacy and tourism) or regional cases (e.g., Indonesia), this study offers a comprehensive panorama of the field and its foundational components. As such, it may serve as a springboard for future systematic reviews and comparative research in gastrodiplomacy and cultural diplomacy at large.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

GL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KM: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2025.1659162/full#supplementary-material

References

Arksey, H., and O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 8, 19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

Chapple-Sokol, S. (2013). Culinary diplomacy: breaking bread to win hearts and minds. Hague J. Diplom. 8, 161–183. doi: 10.1163/1871191X-12341244

Chapple-Sokol, S. (2016). A new structure for culinary diplomacy. Available online at: http://culinarydiplomacy.com/blog/2016/08/28/a-new-structure-for-culinary-diplomacy/ (Accessed June 1, 2025).

Clarke, D. (2020). Cultural diplomacy. Oxford, Oxford University Press: Oxford Research Encyclopedias, 1–30.

Fox, A. B. (1959). The power of small states: diplomacy in world war II. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Leonard, M., Stead, C., and Smewing, C. (2002). Public diplomacy. London: The Foreign Policy Centre.

Li, G. F. (2024a). A gastrodiplomacia Chinesa por meio de método audiovisual: O caso do documentário a bite of China. Daxiyangguo Revista Portuguesa de Estudos Asiáticos 32, 41–63. doi: 10.33167/1645-4677

Li, G. F. (2024b). Gastrodiplomacia Chinesa no Presente e no Futuro. J. Int. Stud. 14, 72–86. doi: 10.26619/1647-7251.DT24.5

Li, G. F. (2025). Gastronomia como Soft Power: A Gastrodiplomacia Chinesa em Portugal. Lisboa: Centro Científico e Cultural de Macau (in press).

Lipscomb, A. (2019). Culinary relations: gastrodiplomacy in Thailand, South Korea, and Taiwan. Yale Rev. Int. Stud. 1, 1–3.

Mays, N., Roberts, E., and Popay, J. (2001). “Synthesizing research evidence” in Studying the organisation and delivery of health services: research methods. eds. N. Fulop, P. Allen, A. Clarke, and S. Black (New York: Routledge), 188–220.

Melissen, J. (2015). “The new public diplomacy: between theory and practice” in The new public diplomacy: soft power in international relations. ed. J. Melissen (New York: Palgrave Macmillan), 3–27.

Muljabar, H. (2024). Research of trend gastro diplomacy in Indonesia. J. Islamic World Politics 8, 85–93. doi: 10.18196/jiwp.v8i1.72

Nair, B. B. (2021). Gastrodiplomacy in tourism: capturing hearts and minds through stomachs. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Syst. 14, 30–40.

Octastefani, T., and Kusuma, B. M. A. (2022). Exploring Taiwanese street food in contemporary Indonesian society: between nostalgia and gastrodiplomacy. J. Gov. 7, 797–809. doi: 10.31506/jog.v7i4.15663

Putri, A. R., and Baskoro, R. M. (2023). A "splash" of Taiwan bubble tea: gastrodiplomacy, nation brand and a symbol. AEGIS J. Int. Relat. 7, 75–88. doi: 10.33021/aegis.v7i1.4624

Randolph, J. J. (2009). A guide to writing the dissertation literature review. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 14, 1–13. doi: 10.7275/b0az-8t74

Reynolds, C. (2012). The soft power of food: a diplomacy of hamburgers and sushi? Food Stud. Interdisc. J. 1, 47–60. doi: 10.18848/2160-1933/CGP/v01i02/40518

Rockower, P. (2010a). The gastrodiplomacy cookbook. Available online at: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/the-gastrodiplomacy-cookb_b_716555 (Accessed June 1, 2025).

Rockower, P. (2010b). Branding Taiwan through gastrodiplomacy. Available online at: https://nation-branding.info/2010/07/21/branding-taiwan-through-gastrodiplomacy/ (Accessed June 1, 2025).

Rockower, P. (2012). Recipes for gastrodiplomacy. Place Brand. Public Diplom. 8, 235–246. doi: 10.1057/pb.2012.17

Rockower, P. (2020). “A guide to gastrodiplomacy” in Routledge handbook of public diplomacy. eds. N. Snow and N. J. Cull (New York: Routledge), 205–212.

Spence, C. (2016). Gastrodiplomacy: assessing the role of food in decision-making. Flavour 5, 1–16. doi: 10.1186/s13411-016-0050-8

The Economist. (2002). Thailand’s gastrodiplomacy. Available online at: https://www.economist.com/asia/2002/02/21/thailands-gastro-diplomacy (Accessed June 6, 2025).

Tholhah, T., and Wafa, S. N. (2024). Thailand’s strategy to change the image of sex tourism through gastro diplomacy in 2017-2020. J. Islamic World Politics 8, 151–166. doi: 10.18196/jiwp.v8i2.41

Torraco, R. J. (2005). Writing integrative literature reviews: guidelines and examples. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 4, 356–367. doi: 10.1177/1534484305278283

Travel Daily News. (2012). Malaysia week London: taste Malaysia’s cuisine and enjoy free concerts. Available online at: https://www.traveldailynews.asia/asia-pacific/malaysia-week-london-taste-malaysias-cuisine-and-enjoy-free-concerts/#utm_source=chatgpt.com (Accessed June 8, 2025).

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., et al. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 169, 467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850

United Nations. (2024). World economic situation and prospects 2024. Available online at: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/publication/world-economic-situation-and-prospects-2024/ (Accessed May 28, 2025).

Vellycia, V. (2021). Beyond entertainment: gastrodiplomacy performance in Korean drama and reality show. Communicare J. Commun. Stud. 8, 104–118. doi: 10.37535/101008220212

Wang, M. H. (2014). 美国快餐文化在中国的传播效果及对我国传统饮食文化的冲击 (the effectiveness of the dissemination of American fast food culture in China and its influence on traditional Chinese culinary culture). Teach. Forestry Regions 1, 73–74.

Webster, J., and Watson, R. T. (2002). Analyzing the past to prepare for the future: writing a literature review. MIS Q. 26, xiii–xxiii. doi: 10.2307/4132319

White, W., Barreda, A. A., and Hein, S. (2019). Gastrodiplomacy: captivating a global audience through cultural cuisine—a systematic review of the literature. J. Tourismol. 5, 127–144. doi: 10.26650/jot.2019.5.2.0027

Wilson, R. (2013). Cocina peruana Para El Mundo: gastrodiplomacy, the culinary nation brand, and the context of National Cuisine in Peru. Exchange J. Public Diplom. 2, 13–20.

Xiao, Y., and Watson, M. (2019). Guidance on conducting a systematic literature review. J. Plann. Educ. Res. 39, 93–112. doi: 10.1177/0739456X17723971

Yayusman, M. S., and Mulyasari, P. N. (2024). Indonesia’s spice-based gastrodiplomacy: Australia and Africa continents as the potential markets. JAS J. ASEAN Stud. 12, 51–77. doi: 10.21512/jas.v12i1.8004

Yayusman, M. S., Yaumidin, U. K., and Mulyasari, P. N. (2023). On considering Australia: exploring Indonesian restaurants in promoting ethnic foods as an instrument of Indonesian gastrodiplomacy. J. Ethn. Foods 10, 1–14. doi: 10.1186/s42779-023-00207-1

Keywords: culinary, cultural diplomacy, gastrodiplomacy, public diplomacy, literature review

Citation: Li G and Mok K (2025) More than two decades of gastrodiplomacy: a review of the concept, current characteristics, and future trends. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1659162. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1659162

Edited by:

Carlos Leone, Open University, PortugalReviewed by:

Alla Atamanenko, National University Ostroh Academy, UkraineNihan Tomris Kucun, KTO Karatay University, Türkiye

Copyright © 2025 Li and Mok. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Guofeng Li, bGkuZ3VvZmVuZ0BlZHUudWxpc2JvYS5wdA==

Guofeng Li

Guofeng Li Kakio Mok

Kakio Mok