- 1Faculty of Human Ecology, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia

- 2School of Marxism, Lyuliang University, Lüliang, Shanxi, China

Political identity is key to maintaining social cohesion and political stability. At present, when political apathy among Chinese youth prevails, the Chinese government regards social media as a significant threat to political identity. However, the impact of user-generated social media content on political identity has not been fully explored, especially in the context of epidemic corruption. This study examines how four dimensions of social media content, information sharing, building new relationships, self-presentation, and enjoyment, shape the political identity of Chinese university students, and how perceptions of corruption moderate these relationships in an authoritarian context. Data were collected through a simple random sample survey of 633 students and analyzed using structural equation modeling and hierarchical regression. Results show that information sharing, self-presentation, and enjoyment significantly strengthen political identity, whereas building new relationships has no direct effect. Moreover, corruption perception weakens the positive associations between social media content and political identity. By clarifying the differentiated effects of social media content and the contextual role of corruption, this study integrates Social Identity Theory and Relative Deprivation Theory into political identity research within an authoritarian context, offering new theoretical insights. Practically, the findings suggest that improving political transparency and tolerance can help unlock the positive potential of social media, fostering broader political identity and social cohesion.

1 Introduction

Political identity is crucial in sustaining social cohesion, guiding political participation, and maintaining regime legitimacy (Qin and Li, 2024). It shapes individuals’ self-conception as political community members, helps them recognize dissenting views and external threats, and influences their trust, loyalty, and involvement in political institutions (Malka and Lelkes, 2010; Castiglione, 2009). Conversely, weak or fragmented political identity can lead to political apathy, social division, and even instability in pluralistic societies (Omidi and Roustaei, 2025; Vasist et al., 2024; Martianv, 2024). The global waves of social movements and political change over the past decade have further heightened concerns about identity formation (Alharahsheh and Pius, 2020). As a result, examining the mechanisms through which political identity is constructed has become a key focus in academic research and policy-making.

In the digital era, social media has become a key arena for the construction and contestation of political identity (Qin et al., 2023; Ismail et al., 2025). Unlike top-down traditional media, social media breaks the state’s monopoly over information and political expression. User-generated content enables personalized political expression and decentralised participation, facilitating bottom-up political interaction (Bennett, 2012; Chapman, 2023). Although the role of social media in shaping political behavior has been well established, most studies have focused on elite groups (Prior, 2013; Weismueller et al., 2022). For ordinary citizens, social media allows individuals to express political values and demonstrate group belonging, making them important factors influencing identity. However, prior research has rarely examined the relationship between user-generated content and political identity at the individual level. In addition, some scholars argue that social media promotes political expression and enhances identity (Qin et al., 2023), while others warn that it can lead to community fragmentation and undermine identity (Elsayed, 2021). These inconsistent findings highlight the need to explore the conditions under which social media content shapes political identity.

Corruption is an important contextual factor in this discussion. As a global challenge, corruption exists in all societies. It hinders investment, slows economic growth, distorts public spending, strengthens the informal economy, and contributes to poverty, income inequality, and public disillusionment with political institutions (Damijan, 2023). Corruption is often closely linked to culture and tradition; in some regions, it is viewed as a cultural practice or survival strategy (Walton, 2013). Some scholars have highlighted the potential positive effects of culturally rooted corruption (Pertiwi, 2022). As a result, debate continues over whether corruption leads to social dysfunction or plays a constructive role.

China offers a unique context for examining the interaction of factors that shape political identity. On the one hand, young people are the primary targets of political socialization and the key population for constructing political identity. However, recent surveys reveal a certain degree of political apathy among contemporary Chinese youth. Data from the 2021 Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) show that only 13.7% of young people have participated in grassroots democratic elections. A 2024 survey by People’s Forum further reports that only 40.7% of university students consider political identity important. These findings have drawn considerable attention from scholars and policymakers to the issue of youth political identity. On the other hand, globalisation, digitalisation, and profound socioeconomic transformation have broken the state’s monopoly over information dissemination, creating new opportunities for public oversight, social criticism, and political participation (Bennett, 2012; Chapman, 2023). Social media has become an important platform for youth to explore identity and engage in civic learning, providing a new space for practizing political identity. However, online discourse is often marked by misinformation, emotional rhetoric, and polarization, particularly during public crises, which can undermine political identity and threaten social stability. In response, the Chinese government has strengthened online governance, using opinion guidance and content regulation to maintain political order and stability, thereby creating a tension between state control and social media dynamics (Bennett, 2012; Chapman, 2023).

Within this dual context, whether young people’s content on social media strengthens or weakens their political identity remains an open empirical question. In particular, corruption remains sensitive and highly relevant as an essential element of Chinese political culture (Keliher and Wu, 2016). Against this backdrop, investigating how social media content influences political identity under the moderating effect of corruption perception is theoretically significant and of pressing practical importance.

This study examines the relationship between individual social media content and political identity in China’s unique sociopolitical context and the moderating role of corruption perception. By doing so, it seeks to clarify how social media shapes political identity under perceived corruption and address the gaps in existing research. This approach reveals the mechanisms through which digital practices construct political identity under different institutional settings and extends the application of Social Identity Theory and Relative Deprivation Theory. The findings are expected to offer theoretical insights and policy implications for enhancing political tolerance, promoting civic participation, and strengthening social stability. Thus, this research addresses the following questions:

1. What is the impact of social media content on political identity?

2. To what extent does corruption perception affect the impact of social media content on political identity?

2 Literature review and hypotheses development

2.1 Political identity

The concept of “identity” originates from Erikson’s 1950s psychological research, which conceptualised it as a developmental process that shapes individuals’ worldviews, behaviors, and even social power structures (Weiner and Tatum, 2021). Influenced by psychology and sociology, political scientists in the 1990s began to examine how identity affects political behavior and institutional functioning (Chen and Urminsky, 2019). Today, political identity is an analytical and theoretical lens for understanding how individual identity interacts with broader ideologies and institutional structures (Weiner and Tatum, 2021).

In developmental and social psychology, political identity is a dual-dimensional concept. It is both an internal self-concept and an external social expression. Individuals continuously interpret and present themselves within a political community, and these orientations are shaped and reconstructed through ongoing social interactions (Gentry, 2018). This duality of internal self and external interaction explains why identification with a party or a specific ideology carries strong emotional resonance while also constrained by social norms (Huddy, 2001). Political identity, therefore, is neither purely self-constructed nor entirely externally imposed; instead, it emerges through the dynamic interplay between self-categorization and external recognition. This interactive nature leads scholars to distinguish between personal and social identities as two analytical paths for studying political identity, though the two are not entirely independent (Malka and Lelkes, 2010). From this perspective, political identity is both subjective and relational; an individual’s self-understanding only gains meaning in contrast to others, which helps explain why political identity often takes on a polarized dimension. In democracies, this polarization is commonly expressed through the left–right political spectrum. Labels such as “liberal” and “conservative” signify not only ideological differences but also important markers of identity (Bennett, 2012). However, theoretical frameworks derived from Western contexts cannot be uncritically transplanted to other societies. In China, socialist ideology serves as the dominant framework for political identity construction. Individuals’ political belonging is not expressed along a left–right continuum but rather through their acceptance or distancing from the core socialist values systematically embedded in the education system and broader ideological discourse. This highlights that the construction of political identity is profoundly shaped by the institutional and cultural context in which it occurs.

Consequently, political identity must be understood within its institutional framework. It is simultaneously a product of individual construction and reflects political institutions and ideology. For Chinese youth, political identity cannot be captured by “liberal–conservative” ideological typologies. Instead, it is embedded in state-led socialist ideological education and influenced by social factors such as digital media practices and corruption perception. Accordingly, this study treats socialist ideology as a key indicator of political identity. It explores how youth political identity is shaped in the context of everyday digital media use and perceptions of corruption.

2.2 Social media content and political identity

For a long time, the media have been regarded as a core political apparatus (Boomgaarden and Schmitt-Beck, 2019). By shaping and disseminating political narratives, audiences can internalise these narratives as “common sense,” thereby influencing political identities (Chahal, 2023). Traditional media typically plays a dual role; on the one hand, it reinforces political cognition by controlling the content of information; on the other, it acts as a “gatekeeper,” selecting issues and suppressing alternative viewpoints to maintain homogeneity of identity (Qin et al., 2023). Scholars once hoped the media would fulfil its “fourth estate” function by supervising government and ensuring transparency (Amodu et al., 2014). However, growing criticism highlights that corporate and state control over media restricts viewpoint diversity and deepens ideological bias (Street, 2010). As public trust in traditional media declines and audiences drift away, its influence has further weakened (Hariyanto et al., 2025). Against this backdrop, social media has reshaped the landscape of political communication. Unlike the passive audiences produced by traditional media, digital media has enabled interactive participation, turning users into consumers and producers of political content. Individuals can freely express their views, mobilise around issues, and take personalized action without relying on traditional political institutions. This transformation has facilitated a shift from collective, institutionalized participation to more individualised and networked forms of engagement (Bennett, 2012). However, a key question remains: if traditional media once functioned as a political tool, can decentralised, fragmented, user-driven social media still play the same role?

This debate is particularly salient in authoritarian contexts. The state maintains strict control over traditional media in China, using it as an important channel for political socialization and ideological dissemination (Street, 2010). Social media complicates this landscape. Although not entirely free, it still allows for bottom-up interaction, user-generated content, and personalized political communication (Shao and Wang, 2017). Based on self-disclosure and social interaction on social networks, Cheung et al. (2015) classified social media content into four dimensions: information sharing, building new relationships, self-presentation, and enjoyment. Later studies confirmed that these dimensions represent the core drivers of social media use (Jacobson et al., 2020). While initially applied to media consumption and diffusion studies, these behavioral patterns are equally relevant in political contexts. In digital political communication, information sharing facilitates the dissemination of political narratives and ideological cues; building new relationships enables individuals to connect with like-minded others; self-presentation allows individuals to visualize and express their political identities; and entertainment sustains political engagement through emotional and symbolic practices. These four dimensions are thus not merely general patterns of social media use but also mechanisms through which political identity is expressed, reinforced, and negotiated in online spaces. Even under conditions of tight control, such “micro-spaces” supplement, complicate, and sometimes challenge state-led ideological socialization.

Social Identity Theory (SIT) provides a theoretical foundation for understanding the relationship between social media content and political identity. SIT emphasises that individual identity derives from membership in social groups, including political communities. Social media offers a crucial arena for expressing, forming, and reinforcing such identities. Specifically, information sharing provides shared narrative resources that strengthen cognitive and emotional cohesion within the group while sharpening group boundaries and distinguishing “us” from “them.” Building new relationships allows individuals to transcend geographic and social boundaries, expand group networks, and broaden the reach of political identity. Self-presentation enables individuals to display their political stance and values, achieving self-categorization and making identity more visible, reinforcing group-based identification. Enjoyment allows users to engage with politics in a light and approachable way, normalizing political expression, lowering participation thresholds, and sustaining political identity through affective practice.

Existing research shows that social media exerts a positive influence on political identity. Through self-expression online, individuals make their political views visible, connect with others, and enhance their “political visibility,” strengthening their sense of identity and willingness to participate (Bennett, 2012). Even among Chinese small-town youth, often regarded as politically apathetic, social media, especially short-video platforms, has stimulated political interest and identification (Qin et al., 2023). Therefore, social media is not merely a channel for political information dissemination but a complex arena where political identity is constructed, negotiated, contested, and reinforced. For Chinese youth, social media plays a dual role; it complements state-led ideological socialization while enabling individuals to be seen and connected in broader communities, thereby strengthening political identity.

Building on SIT and previous research, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H1a: Information sharing positively affects political identity.

H2a: Building new relationships positively affects political identity.

H3a: Self-presentation positively affects political identity.

H4a: Enjoyment positively affects political identity.

2.3 Corruption perception as a moderator

Corruption is commonly defined as using public power for private gain (Sampford, 2006), but its impact extends far beyond this narrow definition. It undermines democratic principles such as justice, transparency, and accountability, erodes citizens’ trust in political leaders and institutions, and profoundly shapes individuals’ political attitudes (Jameel et al., 2019). Therefore, it is not merely an economic or administrative problem but an important contextual factor influencing political attitudes and behavior.

In China, corruption has persisted and become more widespread due to economic reforms and large-scale privatization of state-owned enterprises (Dong and Torgler, 2013; Shivakumar, 2005). It has reached epidemic proportions since the reform and opening-up era, fueling discontent with political identity (He and Jiang, 2020; Orjuela, 2017). Scholars have further emphasised that corruption is culturally embedded, functioning both as a widespread social problem and a phenomenon rooted in cultural practices (Keliher and Wu, 2016). Measuring corruption is a key challenge in corruption research. Unlike direct indicators such as conviction rates, corruption perception captures how citizens evaluate public power for private benefit, reflecting individual experience and broader social narratives (Charron, 2016; Melgar et al., 2010). When corruption perception is high, norms of fairness are weakened, political trust declines, and identification with dominant political values is reduced. Given its corrosive effects, the Chinese government has conducted sustained anti-corruption campaigns since 2012. These efforts, from investigating and punishing corrupt officials to launching educational and publicity initiatives, aim to rebuild public confidence in the ruling party and the political system.

Existing empirical studies on the relationship between social media and political attitudes and behaviors have produced inconsistent findings. Some research highlights the positive effects of social media, arguing that online self-expression enhances individuals’ political visibility, thereby strengthening their sense of identity and willingness to participate (Bennett, 2012). For example, studies show that even Chinese small-town youth, often considered politically apathetic, can gradually develop political interest and a sense of identification through platforms such as short video apps (Qin et al., 2023). However, other studies have revealed adverse effects. Social media news use has been found to correlate with increased political cynicism (Song et al., 2021), and some research indicates that social media use may harm political attitudes and even erode trust in political institutions (Kiratli, 2023). To explain these conflicting findings, researchers have begun to examine moderating effects. For instance, Zhu et al. (2019) explored the moderating role of online political expression in the relationship between social media use and political participation. Other studies have investigated moderators such as gender (Alodat et al., 2023) and content type (Matthes et al., 2023). Lorenz-Spreen et al. (2023) emphasised that these relationships often vary across national contexts, suggesting that country-specific factors may function as important moderators. Corruption, a significant feature of the political context, has also been shown to moderate political outcomes. Empirical evidence suggests that corruption weakens the ability of e-government initiatives to build political trust (Jameel et al., 2019). Following this logic, corruption perception may also dampen the positive influence of social media content on political identity. Although online practices such as information sharing can promote the construction of a shared political identity, their positive effects may be offset by perceptions of injustice when corruption is widely perceived, potentially leading to political alienation rather than identification.

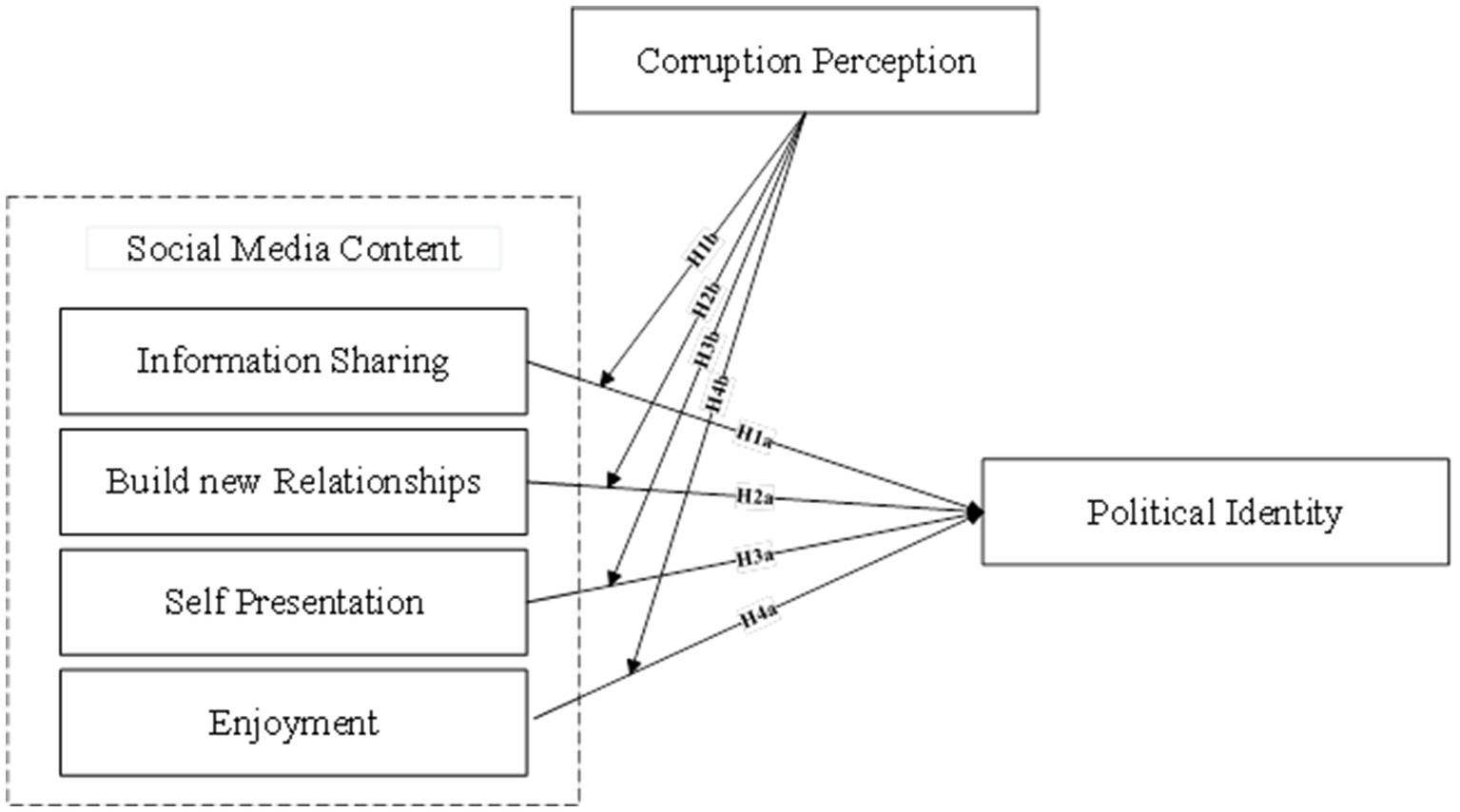

Relative Deprivation Theory (RDT) provides a theoretical framework for understanding this dynamic. RDT argues that individuals evaluate their social status through comparison with others. When resources and opportunities are perceived as unfairly distributed or misused, individuals experience a strong sense of injustice, which reduces their sense of belonging. When corruption violates the socialist ideals of fairness and justice, citizens’ value identification and political identity may be undermined. In this way, corruption is not merely a background variable but a key condition shaping how political identity is formed and sustained. The conceptual framework of the current study is shown in Figure 1.

Building on RDT and previous research, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H1b: Corruption perceptions moderate the relationship between information sharing and political identity, such that this relationship is weaker when perceived corruption is high.

H2b: Corruption perceptions moderate the relationship between building new relationships and political identity, such that this relationship is weaker when perceived corruption is high.

H3b: Corruption perceptions moderate the relationship between self-presentation and political identity, such that this relationship is weaker when perceived corruption is high.

H4b: Corruption perceptions moderate the relationship between enjoyment and political identity, such that this relationship is weaker when perceived corruption is high.

3 Methodology

3.1 Research design

This study adopts a positivist paradigm and employs a quantitative research design to examine the relationships among variables, aiming to provide scientific evidence for objective facts (Park et al., 2020; Sarantakos, 2017; Quick and Hall, 2015). Specifically, data were collected through a questionnaire survey. In the data analysis stage, this study combines Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) and hierarchical regression analysis to test the direct and moderating effects among variables. This design allows for assessing the reliability and validity of the measurement instruments and provides robust statistical estimates for the hypothesised relationships proposed in this study.

3.2 Sample design and data collection

University students are a key group in political socialization, and a combination of civic education, digital environments, and broader social contexts shapes their political identity. To enhance the study’s external validity, undergraduate students from a comprehensive university in central China were selected as the survey population. This region has been designated a priority area for addressing systemic and collective corruption during China’s anti-corruption campaign, making it typical and contextually significant. It thus provides a unique setting for examining the relationship between social media use, corruption perception, and political identity.

The university has a total student population of 20,189. To ensure statistical power and representativeness, the target sample size was determined following Krejcie and Morgan’s (1970) sample size table and Christopher Westland (2010) minimum sample size formula, with a requirement that it exceed 377 and meet the “five-times rule” relative to the number of scale items.

A simple random sampling method was employed, and questionnaires were distributed in class between September 11, 2024, and September 19, 2025. Before distribution, the university’s ethics committee reviewed and approved the research protocol to ensure compliance with academic research standards. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. A total of 700 questionnaires were collected, and after data cleaning and screening, 633 valid responses were retained for analysis. The effective response rate was 90%, which meets the requirements of statistical research.

3.3 Measurement

All variables in this study were measured using five-point Likert scales (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). The scales were adapted from well-established instruments in prior literature, and their reliability and validity were confirmed through back-translation and pilot testing. The final questionnaire consisted of 18 items and included basic demographic information at the end.

The social media content scale was adapted from Jacobson et al. (2020) and comprised four dimensions: information sharing (IS), sample item as “Social media is convenient for informing all my friends about my ongoing activities” (IS); building new relationships(BNR), sample item as “I connect to new people who share my interests through social media”; self-presentation(SP), sample item as “I try to make a good impression on others on social media” (SP); and enjoyment, sample item as “When I am bored, I often go to social media”.

Political identity was measured using a scale adapted from Yang and Stening (2012), which has been further validated in studies on political socialization in China. The scale reflects ideological commitment to socialist principles and measures core ideological orientations in the Chinese context. Items were directly drawn from the writings and speeches of Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping, representing the core of their political and economic philosophies. For instance, Maoist items emphasise values such as “distribution according to need” and a sample item is “Everyone should contribute according to ability and be rewarded according to need.” Whereas post-Maoist items reflect the pragmatism of the reform era and endorse values such as “allowing some people to get rich first” and a sample item is “To be rich by one’s efforts is glorious.” Importantly, this study operationalises political identity as an ideological commitment rather than a behavioral outcome. This choice reflects the Chinese institutional and cultural context, where political identity is manifested more through value alignment and ideological commitment than overt political behavior, as authoritarian regimes often restrict direct citizen participation in the public sphere (Åström et al., 2012). The final political identity scale contained three items, with a Cronbach’s α above 0.70.

In corruption research, scholars typically distinguish between “grand corruption” (high-level corruption) and “petty corruption” (everyday corruption) (Heinrich and Hodess, 2011). For university students with limited exposure to complex political and economic processes, petty corruption, particularly bribery, is the most salient and directly perceived form. Thus, the corruption perception scale was adapted from Gbadamosi and Joubert (2005) and focused on bribery and informal payments, with items such as “Individuals pay bribes and tips to get things done.” This operationalisation has high clarity and face validity and aligns well with students’ direct experiences of corruption.

All scales demonstrated strong internal consistency, with Cronbach’s α coefficients exceeding 0.80. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) further supported good convergent and discriminant validity.

3.4 Data analysis procedure

This study employed a series of data analysis procedures to ensure the rigor and reliability of the results. First, before formal analysis, the raw data were preprocessed and subjected to quality control, including the treatment of missing values, detection of outliers, and tests for normality, to ensure data integrity. Second, to address potential common method bias (CMB), Harman’s single-factor test and the Unmeasured Latent Method Construct (ULMC) technique were applied to the measurement model to statistically control for method effects and enhance the study’s internal validity. Third, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted using Amos 26 to assess the latent constructs’ convergent and discriminant validity, ensuring the measurement model’s stability. Fourth, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was employed to examine the direct effects of the four dimensions of social media content on political identity. Finally, hierarchical regression analyses were performed using the PROCESS macro v2.4 in SPSS 28 to test the moderating role of corruption perception. The significance of the ΔR2 values for the interaction terms was used to evaluate the existence and robustness of the moderation effects, thereby strengthening the explanatory power and credibility of the findings.

4 Results

Several measures were taken to control for potential spurious relationships caused by common method bias (CMB). At the procedural level, steps were implemented to minimise social desirability and censorship effects. The study ensured respondent anonymity, emphasised voluntary participation, and provided clear instructions to encourage honest responses. In the Chinese context, where students may hold concerns about engaging with political topics, questionnaires were collected anonymously, and teachers were not directly involved in the process, effectively reducing potential bias and enhancing the robustness of the results. In addition, CMB was statistically assessed. Harman’s single-factor test results showed that the first factor accounted for 44% of the total variance, below the 50% threshold (Podsakoff et al., 2003). The Unmeasured Latent Method Construct (ULMC) technique was applied, comparing a method-factor model with the structural one. The improvement in model fit was negligible (ΔCFI = 0.006; ΔRMSEA = 0.004), falling short of the criteria typically used to indicate severe CMB (ΔCFI ≥ 0.01; ΔRMSEA ≥ 0.015) (Cheung and Rensvold, 2002). These results suggest that CMB did not seriously threaten this study.

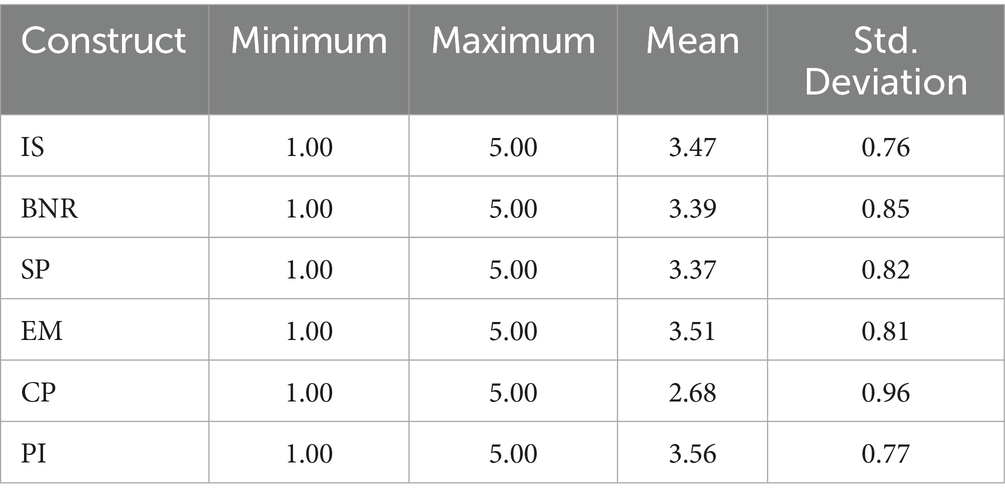

A total of 633 respondents were included in the final sample, consisting of 272 males and 361 females. The sample structure conforms to this university’s male-to-female ratio of 2:3. Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics for the key variables in the study, including the mean, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum values. These statistics provide an overview of the data distribution and variability, laying the groundwork for subsequent hypothesis testing and empirical analysis.

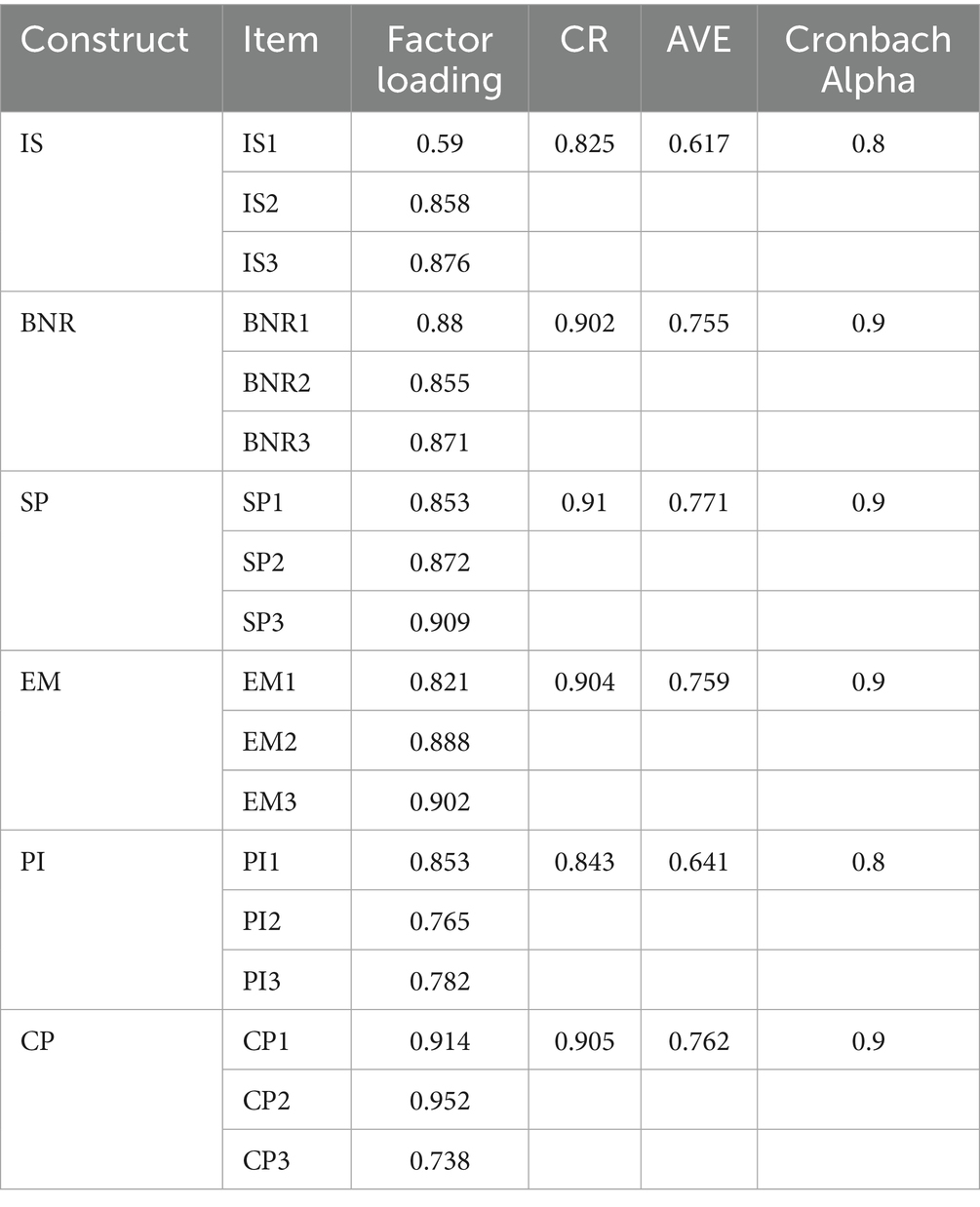

Reliability and validity analyses were conducted to ensure the robustness and applicability of the measurement scales. Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s α coefficients. As shown in Table 2, all variables, including Information Sharing (IS), Building New Relationships (BNR), Self-Presentation (SP), Entertainment (EM), Political Identity (PI), and Corruption Perception (CP), had Cronbach’s α values exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.70 (Pallant, 2020), indicating good internal consistency and reliability. Accordingly, the measurement instruments used in this study were deemed reliable and appropriate for examining the relationships among social media content, corruption perception, and political identity.

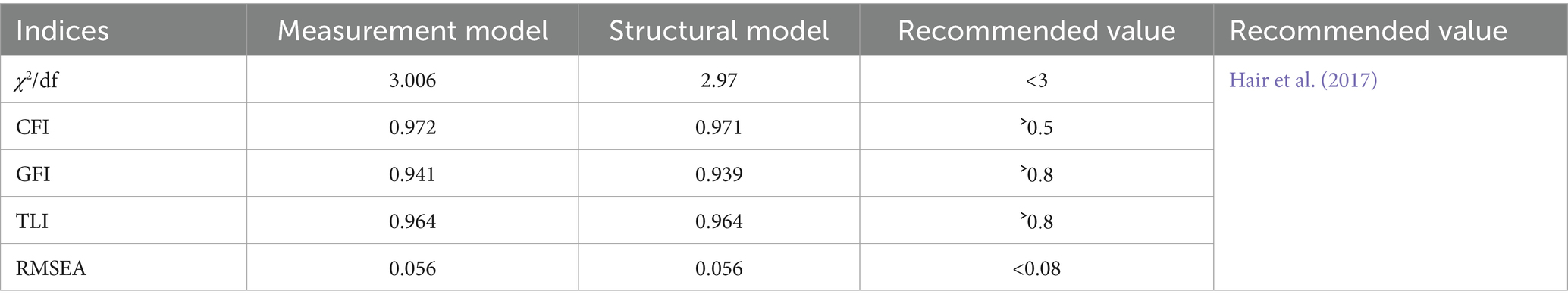

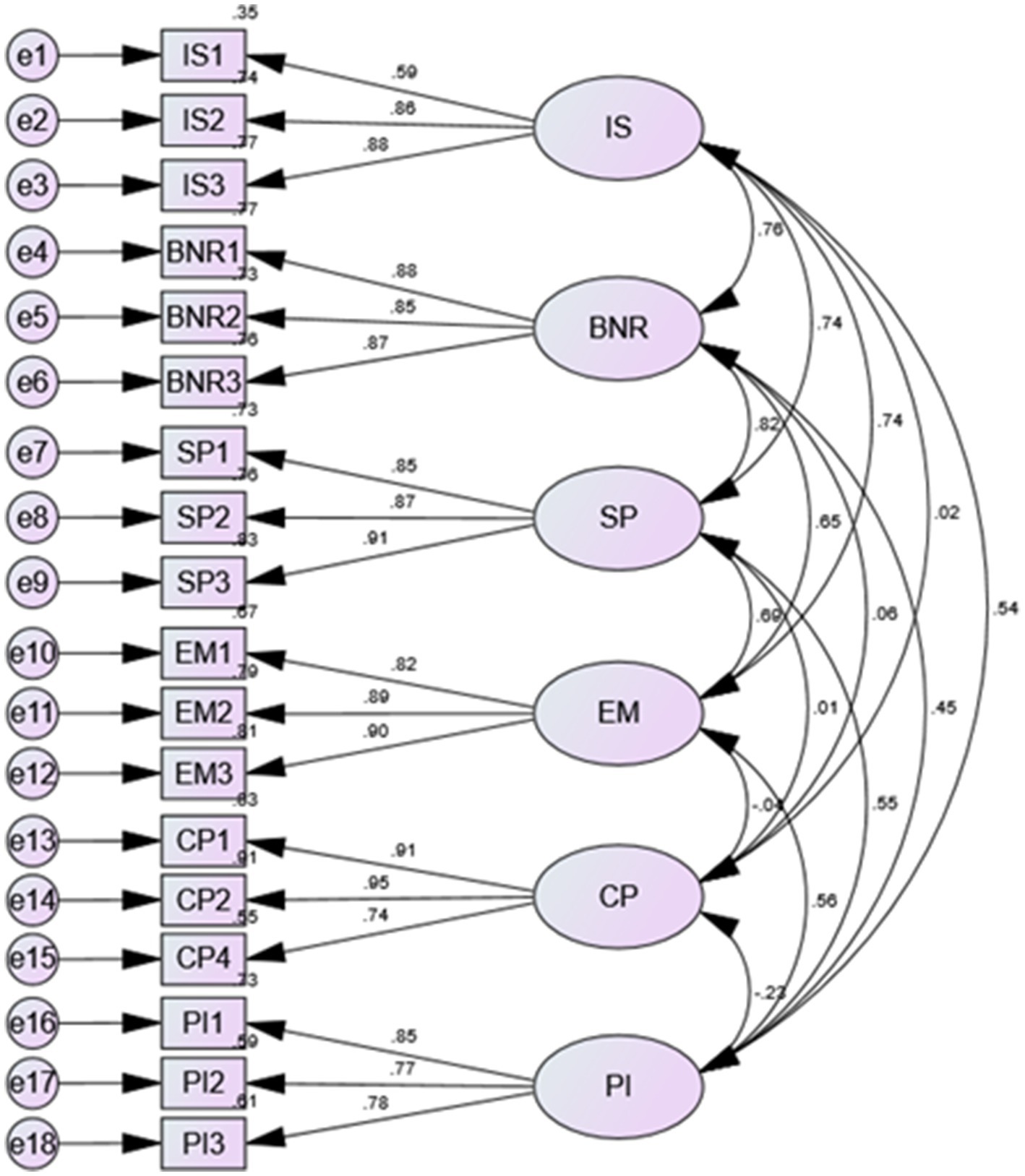

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted to assess the fit of the measurement model and evaluate factor loadings, variances, covariances, and validity metrics (Hox, 2021). Fit indices for the final measurement model are presented in Table 3. Key indicators confirm acceptable model fit: ChiSq/df is 3.006, below the recommended threshold of 5; Comparative Fit Index (CFI) is 0.972, exceeding the recommended minimum of 0.90; and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) is 0.056, below the maximum acceptable threshold of 0.08 (Hair et al., 2017). Thus, the measurement model demonstrates good data fit, providing a reliable foundation for hypothesis testing. The CFA model is shown in Figure 2.

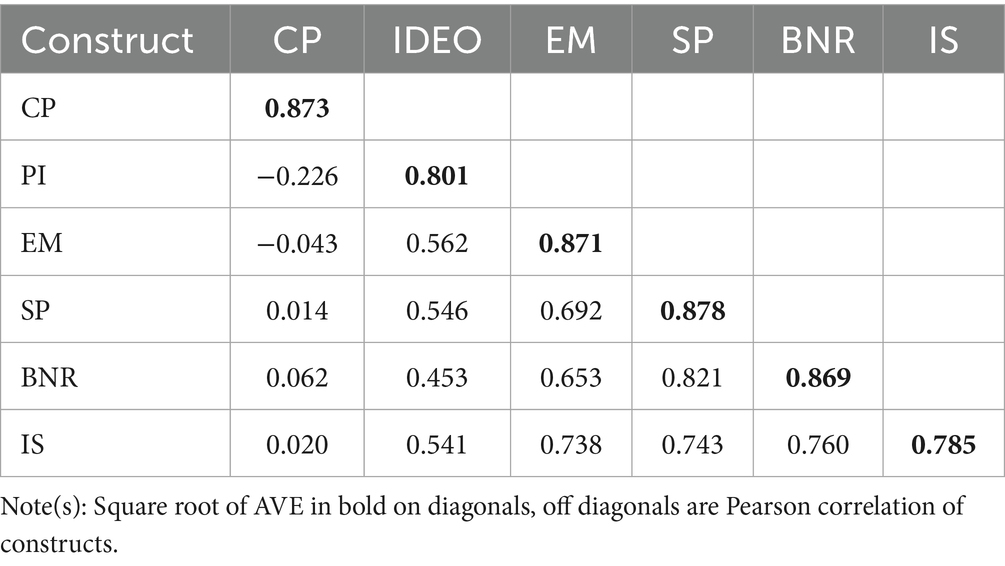

The CFA results show that all factor loadings exceed 0.5, indicating an adequate representation of each construct. Additionally, Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values surpass 0.5, meeting convergent validity criteria (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Composite Reliability (CR) values for all constructs exceed 0.7, confirming the internal consistency and reliability of the scales (Bagozzi and Yi, 1988). As illustrated in Table 4, the square root of each construct’s AVE is greater than or equal to its correlations with other variables, satisfying the Fornell-Larcker criterion and establishing discriminant validity (Fornell and Larcker, 1981).

In summary, CFA confirms the measurement model’s reliability and validity, establishing robust constructs suitable for hypothesis testing.

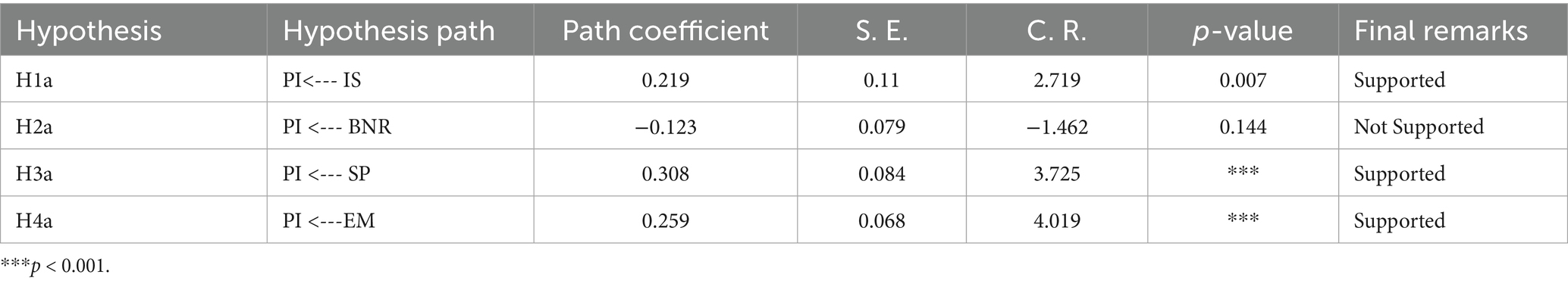

4.1 Direct effects

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was employed to test the hypothesised relationships between the dimensions of social media content and political identity. As shown in Table 5, three dimensions, Information Sharing (IS), Self-Presentation (SP), and Entertainment (EM), were found to exert significant and positive effects on Political Identity (PI). These results support Hypotheses H1, H3, and H4. Specifically, when individuals actively share political information, express their political values online, and derive enjoyment from these activities, they are more likely to develop a stronger political identity.

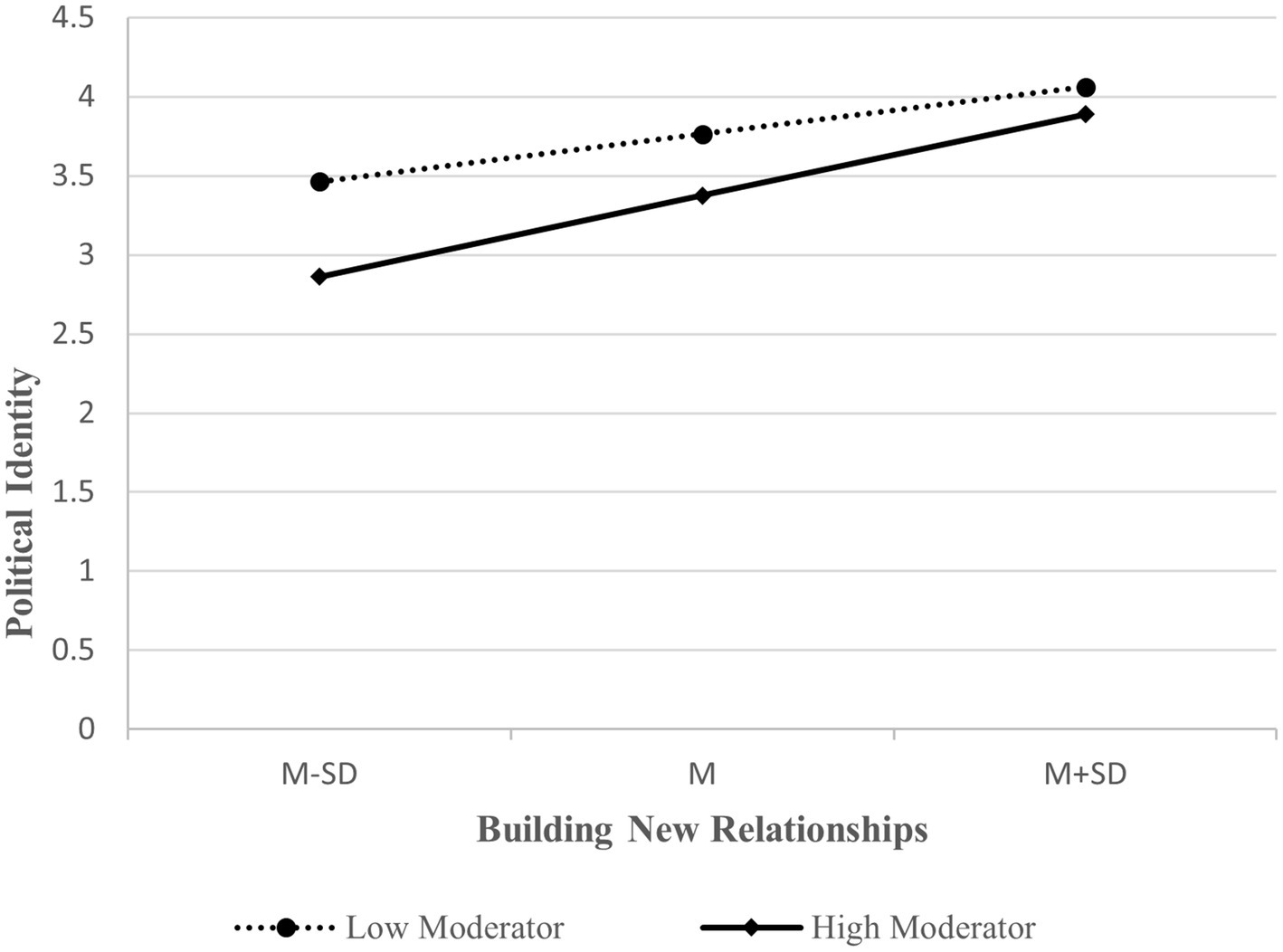

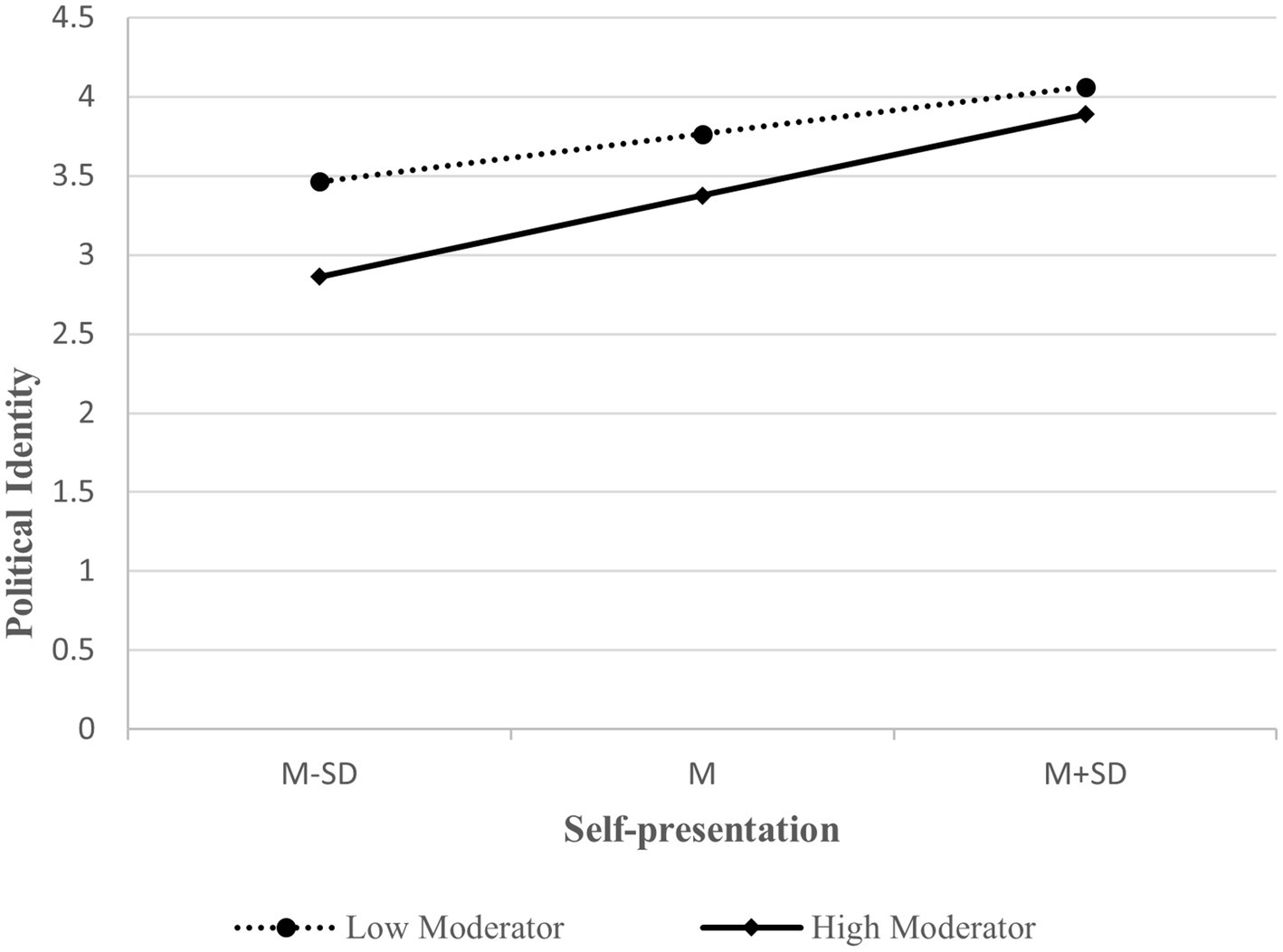

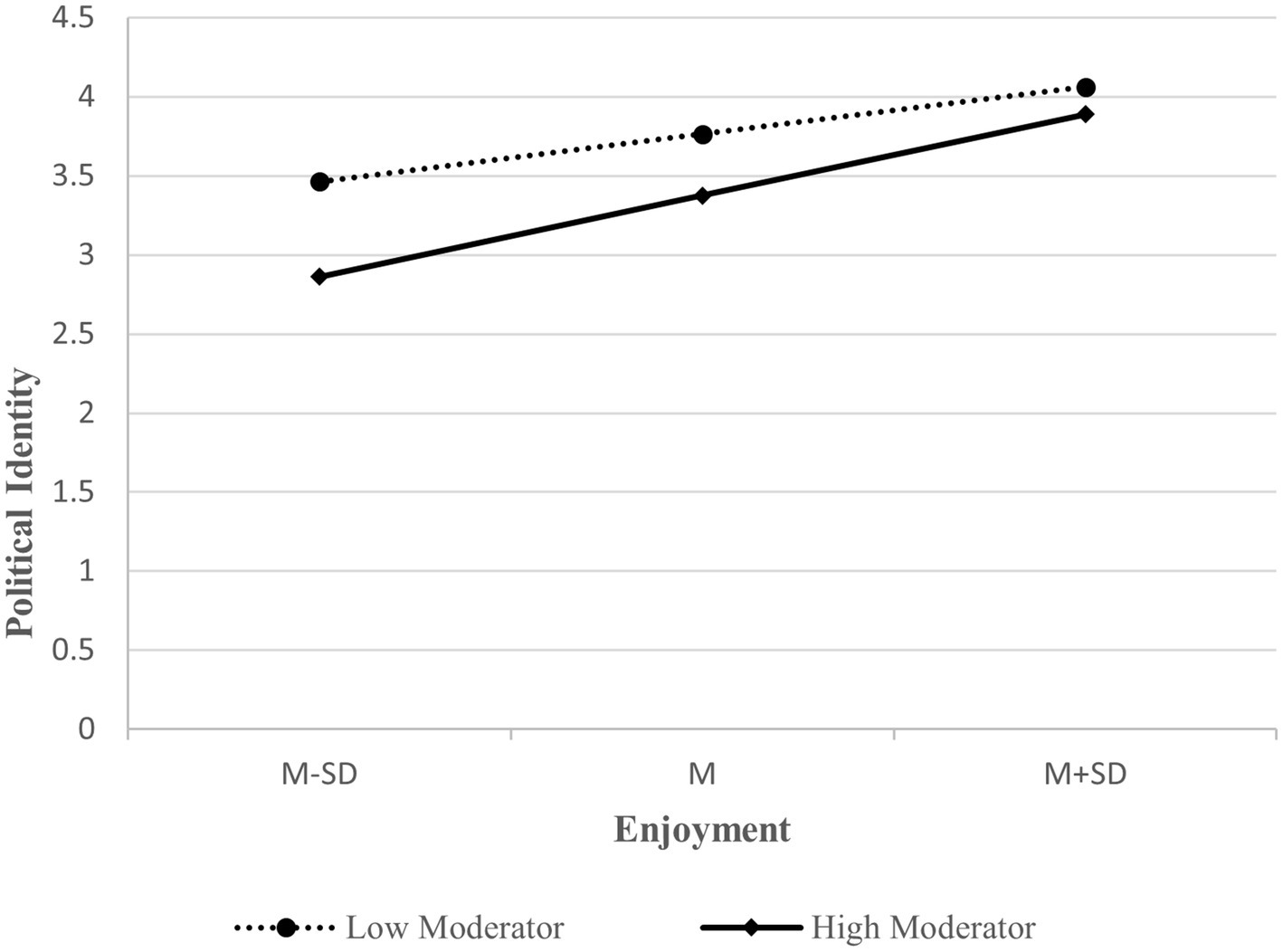

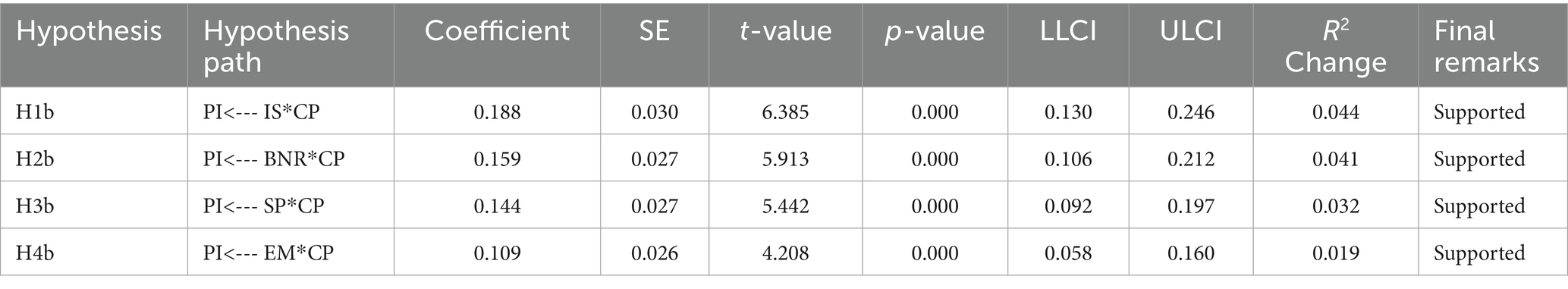

Table 6. Moderating the role of corruption perception to social media content and political identity.

Information sharing promotes the accumulation of collective knowledge and strengthens group narratives, consolidating group boundaries and encouraging political self-categorization. Self-presentation allows individuals to publicly express and communicate their political positions, reinforcing the alignment between personal attitudes and group identity. Enjoyment is an affective amplifier; the positive emotions associated with online participation motivate sustained engagement and consolidate political identity over time. Together, these findings suggest that political identity formation in the digital era is not a passive cognitive process but a dynamic one shaped by online interaction and emotional experience. Social media provides users with information and offers positive emotional feedback, creating a virtuous cycle that reinforces political identity.

However, an important finding of this study is that the hypothesised relationship between Building New Relationships (BNR) and political identity was not supported (see Table 5). This result appears to contradict the general expectation of Social Identity Theory (SIT), which posits that building relationships strengthens group belonging and identification. A plausible explanation is that relational activities on social media are often oriented toward personal or entertainment-related purposes rather than political goals (Caldeira et al., 2020). Consequently, the new connections formed tend to be weak ties or non-political, limiting their direct capacity to reinforce political identity. Furthermore, political risk and censorship pressures make young people cautious about forming overtly political relationships online (López-Fraile and Alonso Guisande, 2025), reducing BNR’s effectiveness as a vehicle for political identity formation. These findings suggest that BNR’s role in constructing political identity is more complex than SIT might predict. In the present model, BNR’s effects may operate through indirect pathways, such as mediation by political discussion or trust, that were not directly captured, resulting in a statistically nonsignificant direct effect.

In summary, the current findings highlight that specific forms of social media, particularly information sharing, self-presentation, and enjoyment, may play a meaningful role in shaping political identity. However, other dimensions of social media activity, such as creating new relationships, do not directly influence political identity.

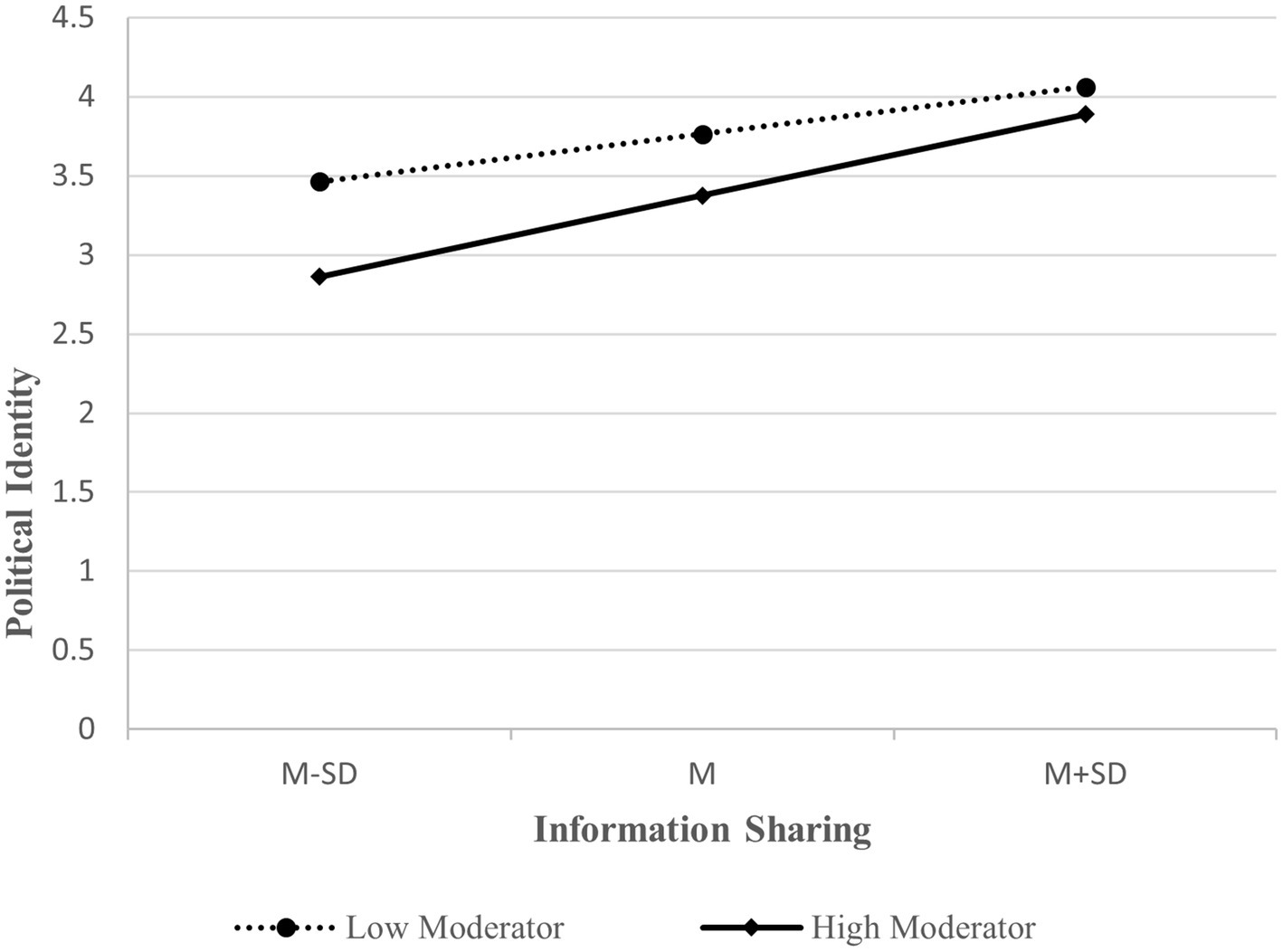

4.2 Moderating effect of corruption perception

This study used the PROCESS v2.4 macro to conduct hierarchical regression analysis and test the moderating role of corruption perception (CP) in the relationship between social media content (SMC) and political identity (PI). The results show significant interaction effects on PI between CP and all four dimensions of SMC, information sharing, building new relationships, self-presentation, and enjoyment (see Table 6). The confidence intervals for all interaction terms excluded zero, indicating that the moderation effects were robust. Simple slope analyses (see Figures 3–6) further revealed that when individuals reported high levels of CP, the positive effects of SMC on PI were significantly weaker. When CP was low or at the mean level, the positive effects of these SMC dimensions on PI were stronger and more pronounced. These findings suggest that CP plays a critical “contextual gatekeeping” role in constructing political identity. It diminishes the identity-strengthening effect of social media and reduces the likelihood that young people will build political trust and value resonance through digital platforms. In other words, although social media provides interactive space and informational resources for identity formation, its positive function depends on individuals’ perceptions of institutional justice and social fairness.

This result is consistent with the Relative Deprivation Theory (RDT). RDT holds that when people perceive corruption as widespread, they interpret political content with suspicion and a sense of injustice, leading to political apathy and alienation. This ultimately limits social media’s positive role in constructing political identity. These findings imply that improving institutional transparency and credibility may be necessary for unlocking social media’s potential in political education and fostering political identity among youth.

Overall, the results support Hypotheses H1a, H3a, H4a, H1b, H2b, H3b, and H4b. Expressive and participatory forms of social media, such as information sharing, self-presentation, and enjoyment, are more conducive to forming political identity. In contrast, relationship-oriented use (BNR) shows limited effects, which may be closely linked to censorship pressures in the Chinese cultural context. In addition, corruption perception, as a key indicator of the sociopolitical environment, significantly weakens the positive role of social media in constructing political identity. These findings suggest that the digital construction of political identity depends on institutional credibility and a shared sense of social fairness. They deepen our understanding of the mechanisms of political identity formation under authoritarian conditions and highlight the need to consider both platform characteristics and governance context when designing digital civic education initiatives and youth ideological guidance strategies.

5 Discussion

In the digital era, social media has become a central political expression and participation platform, significantly influencing political identity construction. This study empirically examined how four dimensions of social media content, IS, SP, EM, and BNR, affect PI under conditions of perceived corruption.

The results show that IS, SP, and EM significantly positively affect PI, consistent with Social Identity Theory (SIT) expectations. These findings suggest that these dimensions can effectively strengthen individual political identity on social media platforms. IS provides shared political narratives that enhance cognitive consistency and group emotional bonds. This result is consistent with prior research showing that information sharing on social media can positively influence political attitudes and offline participation (Lane et al., 2017). Self-presentation makes political positions visible and gives individuals a sense of presence and alignment within the group. Such expressions are not merely displays but part of an identity-building process, in which repeated articulation of similar themes gradually produces a stable self-concept (Nilsson, 2012). In authoritarian settings, however, information sharing and self-presentation are subject to censorship and surveillance. Young Chinese users must navigate the tension between strengthening their identity and avoiding political risk. This often leads to symbolic or indirect forms of “strategic presentation.” While such presentations may appear superficial, they can reinforce political identity through emotional resonance and value alignment. Enjoyment also plays an important role. Identity is constructed through symbols and discourse and supported by emotion. Enjoyment provides the affective “grip” that makes political content less risky, allowing it to enter daily conversation in humorous and lighthearted forms such as memes. This lowers the threshold for participation and sustains emotional bonds over time (Kølvraa, 2018). Enjoyment, therefore, is not mere diversion but an important medium for maintaining and expanding political identity in constrained environments.

This study also found no significant direct relationship between BNR and PI, a result that does not fully align with SIT or some earlier studies. Although relational ties are often viewed as critical resources for identity formation, enhancing status and broadening collective belonging (Zhao et al., 2008; Stoeckel, 2016), the findings suggest that the Chinese context introduces additional complexity. New relationships on social media are often oriented toward entertainment or instrumental goals rather than explicitly political purposes (Caldeira et al., 2020). Moreover, given the sensitivity of political networks and censorship pressures, young Chinese users remain cautious about forming overt political ties online (Lemaire, 2024). They prefer reinforcing identity within existing, lower-risk networks rather than forming new political relationships. This implies that the effect of BNR may operate indirectly, for example, through network trust, rather than directly shaping political identity.

Moderation analysis further revealed that corruption perception (CP) significantly weakens the positive effects of social media content on PI. Individuals with high CP are more likely to interpret political discourse with suspicion and perceive injustice, thereby limiting the identity-building effects of social media. This finding is consistent with the Relative Deprivation Theory (RDT), which argues that when expectations and reality diverge, individuals experience disappointment and alienation, weakening their political identification. Although the moderation effects in this study were statistically significant but small, explaining an additional 2 to 4% of variance, their importance should not be underestimated. Cohen (2013) and Funder and Ozer (2019) argue that minor effects in social science research can accumulate over time and across populations to produce substantial social consequences. Even slight declines in political identity, when aggregated across millions of young people, may have far-reaching implications for political stability. Interestingly, some cultural research, such as Pertiwi (2022), suggests that corruption may function positively within relational cultures such as guanxi. However, this study finds no such positive effect. Instead, our findings align with Jameel et al. (2019) and Ghura et al. (2020), confirming that corruption primarily undermines constructive political processes.

This study highlights the complex interaction between social media content, corruption perception, and political identity. In China’s authoritarian context, where surveillance and censorship are pervasive, information sharing, self-presentation, and entertainment should not be dismissed as superficial engagement. Instead, they represent important avenues for maintaining and strengthening political identity under restrictive conditions. At the same time, CP acts as a contextual constraint that significantly reduces the effectiveness of digital identity construction. These findings enrich the theoretical understanding of political identity formation and suggest that future research should explore how platform mechanisms, cultural factors, and governance environments jointly shape the political socialization of youth.

6 Conclusion, contributions, and implications

This study empirically examined the effects of four dimensions of social media content, information sharing (IS), self-presentation (SP), entertainment (EM), and building new relationships (BNR), on political identity (PI), and explored the moderating role of corruption perception (CP). The results show that IS, SP, and EM significantly positively affect PI, underscoring the critical role of expressive and participatory forms of social media use in shaping political identity. At the same time, CP significantly moderates the relationship between social media content and PI, revealing the importance of broader sociopolitical contexts in identity construction.

These findings must be interpreted within China’s unique sociopolitical environment, where state surveillance and ideological education play pivotal roles. State monitoring, including algorithmic tracking, content censorship, and restrictions on political networks, creates an environment in which young people remain cautious about forming explicit political relationships online. This dynamic helps explain why BNR does not significantly predict PI in the present model. Chinese youth are more likely to reinforce political identity within existing, lower-risk networks rather than by forming new political ties. In addition, ideological education provides a robust top-down framework for identity construction. The state instils ideological commitment and affective attachment through systematic curricula, patriotic rituals, and symbolic practices. These top-down and bottom-up mechanisms contextualise the study’s findings, showing how political identity in China is simultaneously constrained in scope yet intensified.

Theoretically, this study contributes by differentiating the mechanisms through which distinct forms of social media use influence political identity and emphasising CP as a key contextual moderator. It demonstrates that in authoritarian settings, information sharing, self-expression, and enjoyment are not merely superficial behaviors but essential means of maintaining and reinforcing political identity under constraint. This enriches the theoretical framework for understanding political identity construction. Practically, the findings offer several insights for policy and education. First, the moderating effect of CP suggests that high perceptions of corruption weaken the positive impact of social media on PI. Policymakers should strengthen anti-corruption efforts, regulate the conduct of public officials, and enhance transparency to build institutional trust and a sense of fairness, critical foundations for fostering political identity and social stability. Second, the findings suggest that regulatory frameworks should not focus solely on risk suppression and content censorship. Instead, they should create institutionalized spaces for legitimate and diverse political expression, balancing preventing extremist discourse with encouraging rational and constructive debate. Such an approach may foster political tolerance and align with China’s goal of building a “pluralistic yet unified political community.” Third, given that CP and institutional frameworks condition the effects of social media, civic education should go beyond ideological indoctrination and include the cultivation of critical media literacy. By helping students critically evaluate online information and understand political divergence, civic education can strengthen youths’ political reasoning, political tolerance, and capacity for stable identity formation.

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations. First, the sample consists exclusively of university students, a relatively homogeneous group in age, education, and life experience. The findings should therefore not be overgeneralized to the broader population. In addition, political identity formation in China is shaped by the digital divide, urban–rural disparities, and differences in political knowledge. To improve external validity, future studies should include more diverse samples and incorporate these structural variables for in-depth exploration to more comprehensively reveal the formation mechanism of political identity among Chinese youth. Second, the cross-sectional survey design limits the ability to capture the dynamic evolution of political identity and restricts causal inference. Third, the measure of CP used in this study primarily reflects perceptions of petty corruption and does not fully capture systemic corruption or institutional distrust, which may also influence PI and should be addressed in future research. Fourth, this study did not conduct a retest reliability test, and future research should further verify this through longitudinal or repeated measurement designs.

Future work could extend these findings in several ways. First, additional moderators such as political cynicism, institutional trust, and media literacy could be incorporated to better specify the boundary conditions of the SMC and PI relationship. Second, longitudinal and experimental designs should be employed. Longitudinal studies can track changes in political identity over time, while experimental designs can manipulate contextual cues to establish causal mechanisms, providing more substantial evidence for the study’s conclusions. Third, qualitative approaches such as in-depth interviews, focus groups, or digital ethnography could complement quantitative data by capturing identity construction’s cognitive, emotional, and social nuances, revealing micro-level mechanisms that survey data may overlook. Fourth, in future research on corruption perception, scholars may move beyond the focus on “petty corruption,” such as bribery, and include institutional distrust, such as systemic inequality and cronyism. This approach can provide a more comprehensive understanding of how corruption perception shapes political identity.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Lyuliang University Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

NJ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. LF: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the reviewers for their valuable comments and constructive suggestions. Their insightful feedback on the research has significantly improved the quality of this paper and broadened the authors’ understanding of the research topic. Any remaining errors or shortcomings are the sole responsibility of the authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2025.1659804/full#supplementary-material

References

Alharahsheh, H. H., and Pius, A. (2020). A review of key paradigms: positivism vs interpretivism. Glob. Acad. J. Hum. 2, 39–43. doi: 10.36348/gajhss.2020.v02i03.001

Alodat, A. M., Al-Qora’N, L. F., and Abu Hamoud, M. (2023). Social media platforms and political participation: a a study of Jordanian youth engagement. Soc. Sci. 12:402. doi: 10.3390/socsci12070402

Amodu, L. O., Usaini, S., and Ige, O. (2014). The media as fourth estate of the realm. ResearchGate, No. 10.

Åström, J., Karlsson, M., Linde, J., and Pirannejad, A. (2012). Understanding the rise of e-participation in non-democracies: domestic and international factors. Gov. Inf. Q. 29, 142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2011.09.008

Bagozzi, R. P., and Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 16, 74–94. doi: 10.1007/BF02723327

Bennett, W. L. (2012). The personalization of politics:political identity, social media, and changing patterns of participation. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 644, 20–39. doi: 10.1177/0002716212451428

Boomgaarden, H. G., and Schmitt-Beck, R. (2019). The media and political behavior. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Caldeira, S. P., De Ridder, S., and Van Bauwel, S. (2020). Between the mundane and the political: women’s self-representations on instagram. Soc. Med. 6:802. doi: 10.1177/20563051209408

Castiglione, D. (2009). Political identity in a community of strangers. Eur. Identity 1:3. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511806247.003

Chahal, V. (2023). The media’s impact on political discourse and public opinion. Res. Rev. Int. J. Multidiscip. 8, 138–152. doi: 10.31305/rrijm.2023.v08.n04.017

Chapman, A. L. (2023). Social media for civic education: Engaging youth for democracy. Berlin: Springer Nature.

Charron, N. (2016). Do corruption measures have a perception problem? Assessing the relationship between experiences and perceptions of corruption among citizens and experts. Eur. Polit. Sci. Rev. 8, 147–171. doi: 10.1017/S1755773914000447

Chen, S. Y., and Urminsky, O. (2019). The role of causal beliefs in political identity and voting. Cognition 188, 27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2019.01.003

Cheung, C., Lee, Z. W. Y., and Chan, T. K. H. (2015). Self-disclosure in social networking sites. Internet Res. 25, 279–299. doi: 10.1108/IntR-09-2013-0192

Cheung, G. W., and Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Modeling 9, 233–255. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5

Christopher Westland, J. (2010). Lower bounds on sample size in structural equation modeling. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 9, 476–487. doi: 10.1016/j.elerap.2010.07.003

Damijan, S. (2023). Corruption: a review of issues. Econ. Bus. Rev. 25, 1–10. doi: 10.15458/2335-4216.1314

Dong, B., and Torgler, B. (2013). Causes of corruption: evidence from China. China Econ. Rev. 26, 152–169. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2012.09.005

Elsayed, W. (2021). The negative effects of social media on the social identity of adolescents from the perspective of social work. Heliyon 7:e06327. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06327

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18, 39–50. doi: 10.2307/3151312

Funder, D. C., and Ozer, D. J. (2019). Evaluating Effect Size in Psychological Research: Sense and Nonsense. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 2, 156–168. doi: 10.1177/2515245919847202

Gbadamosi, G., and Joubert, P. (2005). Money ethic, moral conduct and work related attitudes. J. Manage. Dev. 24, 754–763. doi: 10.1108/02621710510613762

Gentry, B. (2018). “Political identity: meaning, measures, and evidence” in Why youth vote: Identity, inspirational leaders and Independence. ed. B. Gentry (Cham: Springer International Publishing).

Ghura, H., Harraf, A., Li, X., and Hamdan, A. (2020). The moderating effect of corruption on the relationship between formal institutions and entrepreneurial activity. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 12, 58–78. doi: 10.1108/JEEE-03-2019-0032

Hair, J. F., Celsi, M. W., Ortinau, D. J., and Bush, R. P. (2017). Essentials of marketing research. Columbus, Ohio: McGraw-Hill.

Hariyanto, D., Dharma, F. A., Rodiyah, I., Amalia, F. P., and Rositah, N. D. N. (2025). The role of mainstream media in politicization identity politic on social media. SHS Web Conf. 212:4041. doi: 10.1051/shsconf/202521204041

He, H., and Jiang, S. (2020). Partisan culture, identity and corruption: An experiment based on the Chinese Communist Party. China Econ. Rev. 60:101402. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2019.101402

Heinrich, F., and Hodess, R. (2011). “Measuring corruption” in Handbook of Global Research and Practice in Corruption. eds. A. Graycar and R. G. Smith (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), 18–33.

Hox, J. J. (2021). “Confirmatory factor analysis” in The encyclopedia of research methods in criminology and criminal justice. eds. J. C. Barnes and D. R. Forde (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley).

Huddy, L. (2001). From social to political identity: a critical examination of social identity theory. Polit. Psychol. 22, 127–156. doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00230

Ismail, A., Munsi, H., Yusuf, A. M., and Hijjang, P. (2025). Mapping one decade of identity studies: a comprehensive bibliometric analysis of global trends and scholarly impact. Soc. Sci. 14:92. doi: 10.3390/socsci14020092

Jacobson, J., Gruzd, A., and Hernández-García, Á. (2020). Social media marketing: who is watching the watchers? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 53:101774. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.03.001

Jameel, A., Asif, M., Hussain, A., Hwang, J., Sahito, N., and Bukhari, M. H. (2019). Assessing the moderating effect of corruption on the e-government and trust relationship: an evidence of an emerging economy. Sustainability 11:6540. doi: 10.3390/su11236540

Keliher, M., and Wu, H. (2016). Corruption, anticorruption, and the transformation of political culture in contemporary China. J. Asian Stud. 75, 5–18. doi: 10.1017/S002191181500203X

Kiratli, O. S. (2023). Social media effects on public Trust in the European Union. Public Opin. Q. 87, 749–763. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfad029

Kølvraa, C. (2018). Psychoanalyzing Europe? Political enjoyment and european identity. Polit. Psychol. 39, 1405–1418.

Krejcie, R. V., and Morgan, D. W. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. 30, 607–610. doi: 10.1177/001316447003000308

Lane, D. S., Kim, D. H., Lee, S. S., Weeks, B. E., and Kwak, N. (2017). From online disagreement to offline action: how diverse motivations for using social media can increase political information sharing and catalyze offline political participation. Soc. Med. Soc. 3:162. doi: 10.1177/20563051177162

Lemaire, P. (2024). Online censorship and young people’s use of social media to get news. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 45, 521–535. doi: 10.1177/01925121231183105

López-Fraile, L. A., and Alonso Guisande, M. Á. (2025). Censorship and self-censorship of university students on Instagram and Tiktok. Visual Rev. Inte. Visual Cult. Rev. 17, 149–166. doi: 10.62161/revvisual.v17.5786

Lorenz-Spreen, P., Oswald, L., Lewandowsky, S., and Hertwig, R. (2023). A systematic review of worldwide causal and correlational evidence on digital media and democracy. Nat. Hum. Behav. 7, 74–101. doi: 10.1038/s41562-022-01460-1

Malka, A., and Lelkes, Y. (2010). More than ideology: conservative–liberal identity and receptivity to political cues. Soc. Justice Res 23, 156–188. doi: 10.1007/s11211-010-0114-3

Matthes, J., Heiss, R., and Van Scharrel, H. (2023). The distraction effect. Political and entertainment-oriented content on social media, political participation, interest, and knowledge. Comput. Human Behav. 142:107644. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2022.107644

Melgar, N., Rossi, M., and Smith, T. W. (2010). The perception of corruption. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 22, 120–131. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/edp058

Nilsson, B. (2012). Politicians' blogs: strategic self-presentations and identities. Identity 12, 247–265. doi: 10.1080/15283488.2012.691252

Omidi, A., and Roustaei, M. (2025). Citizen diplomacy and Armenian-Azeri tensions: challenges and opportunities. Cent. Eur. Stud., 1–28. doi: 10.22059/jcep.2025.379591.450238

Orjuela, C. (2017). “Corruption and identity politics in divided societies” in Corruption in the aftermath of war. eds. J. Lindberg and C. Orjuela (Abingdon: Routledge).

Pallant, J. (2020). Spss survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using Ibm Spss. Abingdon: Routledge.

Park, Y. S., Konge, L., and Artino, A. R. (2020). The positivism paradigm of research. Acad. Med. 95, 690–694. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003093

Pertiwi, K. (2022). “We care about others”: discursive constructions of corruption Vis-à-Vis national/cultural identity in Indonesia’s business-government relations. Crit. Perspect. Int. Bus. 18, 157–177. doi: 10.1108/cpoib-03-2019-0025

Podsakoff, P. M., Mackenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Prior, M. (2013). Media and political polarization. Ann. Rev. 16, 101–127. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-100711-135242

Qin, J., Du, Q., Deng, Y., Zhang, B., and Sun, X. (2023). How does short video use generate political identity? Intermediate mechanisms with evidence from China’s small-town youth. Front. Psychol. 14:273. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1107273

Qin, G., and Li, X. (2024). The political identity of China's emerging youth. Soc. Sci. Q. 105, 2122–2136. doi: 10.1111/ssqu.13455

Quick, J., and Hall, S. (2015). Part three: The quantitative approach. J. Perioper Pract. 25, 192–196. doi: 10.1177/175045891502501002

Shao, P., and Wang, Y. (2017). How does social media change Chinese political culture? The formation of fragmentized public sphere. Telematics Inform. 34, 694–704. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2016.05.018

Shivakumar, S. (2005). “Institutions, market exchange, and development” in The constitution of development: Crafting capabilities for self-governance. ed. S. Shivakumar (New York: Palgrave Macmillan US).

Song, H., De Zúñiga, H. G., and Boomgaarden, H. G. (2021). Social media news use and political cynicism: Differential pathways through “news finds me” perception. Social media news and its impact. Abingdon: Routledge.

Stoeckel, F. (2016). Contact and community: the role of social interactions for a political identity. Polit. Psychol. 37, 431–442. doi: 10.1111/pops.12295

Vasist, P. N., Chatterjee, D., and Krishnan, S. (2024). The polarizing impact of political disinformation and hate speech: a cross-country configural narrative. Inf. Syst. Front. 26, 663–688. doi: 10.1007/s10796-023-10390-w

Walton, G. W. (2013). Is all corruption dysfunctional? perceptions of corruption and its consequences in Papua New Guinea. Public Adm. Dev. 33, 175–190. doi: 10.1002/pad.1636

Weiner, S., and Tatum, D. S. (2021). Rethinking identity in political. Science 19, 464–481. doi: 10.1177/1478929920919360

Weismueller, J., Harrigan, P., Coussement, K., and Tessitore, T. (2022). What makes people share political content on social media? The role of emotion, authority and ideology. Comput. Hum. Behav. 129:107150. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2021.107150

Yang, S., and Stening, B. W. (2012). Cultural and ideological roots of materialism in China. Soc. Indic. Res. 108, 441–452. doi: 10.1007/s11205-011-9885-7

Zhao, S., Grasmuck, S., and Martin, J. (2008). Identity construction on Facebook: digital empowerment in anchored relationships. Comput. Human Behav. 24, 1816–1836. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2008.02.012

Keywords: social media content, corruption perception, political identity, ideology, social identity

Citation: Jia N and Fee LY (2025) The influence of social media content on political identity with corruption perception as a moderator. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1659804. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1659804

Edited by:

Enrique Hernández-Diez, University of Extremadura, SpainReviewed by:

Iffat Aksar, Xiamen University, MalaysiaWawan Kurniawan, University of Indonesia, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Jia and Fee. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lee Yok Fee, bGVleW9rZmVlQHVwbS5lZHUubXk=

Na Jia

Na Jia Lee Yok Fee

Lee Yok Fee