- 1Basque Culinary Center, Faculty of Gastronomic Sciences, University of Mondragón, San Sebastián, Spain

- 2Turismo de Portugal, Lisbon, Portugal

- 3Instituto Politecnico de Coimbra Escola Superior de Educacao de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal

- 4Faculty of Education Sciences and Humanities, Universidad Internacional de La Rioja, Logroño, Spain

- 5Escola Superior de Hotelaria e Turismo do Estoril, Estoril, Portugal

- 6International Commission on the Anthropology of Food and Nutrition – Spain & Portugal, Lisbon, Portugal

- 7Center for Research in Anthropology – CRIA NOVA/FCSH – IN2PAST, Lisbon, Portugal

Introduction: This paper examines how diplomatic meals in Portugal (1910–2023) have been shaped by Portuguese foreign policy and geopolitical contexts, and conversely, how Portuguese gastronomic culture has been leveraged as a culinary diplomacy and geopolitical rapprochement strategy. Framed within the theory of international relations, this paper examines how these meals promote transnational political relations, foreign affairs, and project Portuguese identity and soft power through national gastronomy.

Methods: Employing qualitative methods, the research analyses meal environments, highlighting the historical and cultural significance of the dining experience.

Results: The findings reveal five distinct types of diplomatic meals, demonstrating that culinary practices have facilitated diplomatic negotiations while providing opportunities for cultural exchange and political messaging.

Discussion: Although a clear culinary diplomacy strategy was not identified, this study enhances our understanding of the influence of transnational gastronomy on diplomacy, illustrating how national cuisines can be strategically employed to bolster a country’s global standing.

1 Introduction

Food has been a cornerstone in strengthening diplomatic relations since the Classical Greek and Roman civilisations (Zeev, 2021). The statecraft and the concerted diplomatic efforts led by Charles Talleyrand and Chef Marie-Antoine Carême during the Congress of Vienna (1814–1815) facilitated the establishment of a new era for diplomacy, gastronomy and geopolitics. In this triangular reformation, new actors and resources emerged as significant diplomatic players, such as cooks, products and foodways. Hence, culinary and gastronomy play a soft power role (Raffard, 2021b). The role of the table is now undeniable in the diplomatic context. Diplomacy has catalysed the codification and dissemination of national cuisines, leveraging food to facilitate negotiations and elevate French cuisine as the standard in diplomacy (Chapple-Sokol, 2013; Raffard, 2021a).

This paper presents the second part of a study conducted to investigate the existence of a culinary diplomacy strategy in Portugal (1910–2023). Building on the findings of the first study, which examined the composition of Portuguese State meals, this paper focuses on the geopolitical and diplomatic significance of those meals. It seeks to answer the research question “How have diplomatic meals in Portugal both reflected and shaped foreign policy and geopolitics, while mobilising Portuguese gastronomy as a tool of culinary diplomacy?” Assessing the role of gastronomy as a diplomatic tool in international relations through a potential culinary diplomacy strategy, particularly within the context of diplomatic visits, opens new avenues for understanding international relations and geopolitical reconfigurations.

The research examined the menus of official state banquets, receptions, and other diplomatic dining events hosted by Portuguese sovereign bodies, taking into account the embedded historical, political, and cultural aspects. This paper employed qualitative methods to analyse primary data. Besides, since interpretation and data analysis are closely linked to the findings, the authors opted to merge the Results and Discussion sections.

2 Literature review

Modern diplomacy has broadened the classic scopes and classic diplomatic practice, framing it in the increasing complexity of the “geopolitics of world metamorphosis” (Fernandes, 2024). In addition to information, negotiation, and representation, diplomacy now incorporates the promotion and dissemination roles of a country’s economic and cultural spheres (Magalhães, 2005). For all those, the table is an essential mechanism (Stefanini, 2019). Given this diplomatic breadth, Constantinou calls on a “transprofessional diplomacy” to encapsulate not only new non-classically defined diplomatic tasks that have recently appeared as part of the diplomatic relationship, but also to underline some other professionals and skills that have been called up to form part of the diplomatic arenas (Constantinou et al., 2017). This is the case of cooks, food, and gastronomy, which now serve as a mechanism to facilitate the three initial and core diplomatic functions, also providing substance matter within the realm of cultural diplomacy (Kessler, 2020).

The emergence of studies in the intersection between political action, public policies, and gastronomy has given rise to a field of study known as “gastropolitics” or “culinary politics,” whose analyses take on a transdisciplinary perspective (Cabral et al., 2024a). In the Portuguese case, the Portuguese wine soft power has been studied (Balogh and Morgado, 2025).

2.1 Official meals as a political channel

An official meal can be a potent tool for cultivating cross-cultural comprehension and mending divisions between nations (Chapple-Sokol, 2013). Countries have increasingly recognised the value of gastronomy in diplomacy, harnessing the power of food to forge cultural connections, enhance trade relations, and project soft power (Aslan and Çevik, 2020; Cabral et al., 2024b).

This approach to International Relations Theory raises a physiological necessity to a debate level that facilitates cultural dissemination. Official meals aim to foster rapprochement but can also lead to tensions. Many official meals aim to demonstrate political or personal closeness and address geopolitical tensions (Flowers, 2024; Mahon, 2015; Matwick and Matwick, 2022; Teughels, 2021). Some have provoked tensions and conveyed political messages, like the official meal at COP25 (2019, Madrid, Spain) with a menu containing dishes called “Clear water & Dirty water,” “Warm seas. Eating imbalance,” or “Urgent. Minimise animal protein and increase the vegetable protein” (La Vanguardia, 2019). These menus, intentionally designed to draw attention from a gastronomic perspective, also served as a tool to communicate non-gastronomic aspects, showcasing the versatility and depth of culinary diplomacy.

2.2 “Contact zones” theory and the “Mere Exposure Effect”

Food serves as a form of soft power, creating bonds and fostering political meanings through shared experiences and commonalities. These aspects are based on the Theory of contact zones and the “Mere Exposure Effect” (MEE). “Contact zones” are, according to Mary Louise Pratt, “social spaces exhibiting diverse cultural encounters and clashes and asymmetrical power relations” (Pratt in Chan, 2021, p. 12). The “contact hypothesis” derived from the Contact Zones theory “asserts that under the right conditions, contact among members of different groups will reduce hostility and promote more positive behaviour in inter-group meetings. This contention is predicated on the assumption that unfamiliarity and lack of knowledge about another group create tension and potential rivalry” (Chapple-Sokol, 2013, p. 171). The “Mere Exposure Effect” (MEE) is a social psychology phenomenon in which an individual develops a sense of acquaintance and preference while avoiding sentiments of hostility based on “increased contact and familiarity, encouraging acceptance and even desire for further contact” (Suntikul, 2017, p. 5). Also, MEE is based on the “formation of a positive affective reaction to repeated or single exposure to a stimulus, even in the absence of awareness” (Ye and Raaij, 1997, p. 629).

Diplomatic meals serve as “contact zones” in which food helps not only bridge tensions and differences but also create a sense of familiarity, nativeness and bonding through MEE (Chapple-Sokol, 2013; Suntikul, 2017), which are essential for gastronomic promotion.

2.3 Food and the theory of international relations

The examination of food and gastronomy in the context of International Relations underscores their transdisciplinary nature, requiring that disciplines reinvent and continually adapt themselves to integrate the analysis of emerging social phenomena. Several prior studies have already advanced in this direction (Cabral et al., 2024a, 2024b; Gasparatos et al., 2023; Parasecoli and Rodriguez-Garcia, 2023; White et al., 2019). However, little effort has been made to align food studies with the theoretical underpinnings of contemporary international relations. According to Sørensen and Møller (2025), the study of International Relations, understood as the analysis of “relationships and interactions between states, including the activities and policies of national governments, international organisations, non-governmental organisations, and multinational corporations” (Sørensen and Møller, 2025, p. 2) encompasses exploring how people are granted (or not) access to freedom, welfare, justice, order and security. Due to its transversality, the access to food and the cultural aspects that are also manifested in the foodways are neuralgic.

Key foundations of International Relations include Realism, Liberalism, and Social Constructivism, each with a distinct role in relation to food and gastronomy.

In the Realism theory, food is primarily understood as a strategic asset to ensure physiological needs fulfilment and read as a security-related aspect (“to ensure that one has what to eat”). States compete over food resources, using trade restrictions, food embargoes, and agricultural policies as instruments of geopolitical influence, even during war times with humanitarian aid. From this perspective, food security emerges as a key national security concern, underscoring Realism’s view that power politics and survival-driven international relations. From this perspective, food, as a mere means of sustenance, serves as a tool in the struggle for power, where dominance and hegemony also manifest in the dynamics of the global food system. Given that Realism is centred on power and individual state interests, food security emerges as a critical element in international negotiations, functioning both as a resource for political leverage and as a means of exerting influence over other states (Walton, 2012). Realist approaches deeply trust in food diplomacy to balance power on food access (Cabral et al., 2024b).

The school of thought known as Liberalism is fundamentally anchored in the conviction that transnational and international institutions act as moderators, rather than diminutors, of free trade and global economic engagement. Institutions such as the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) are instrumental in facilitating food exchange, fostering the development of international food systems, and promoting economic interdependence as a mechanism for conflict prevention (Sørensen and Møller, 2025). Access to food serves as a reflection of and a response to global power imbalances, thereby positioning food as a pivotal instrument of cooperation and a source of legitimacy within international relations. Through trade agreements and development policies, Liberalism posits that food can serve as a vehicle for actualising cooperation, ensuring a more equitable distribution of resources, and reinforcing the interconnected nature of an increasingly globalised world.

Finally, for the Social Constructivism theory, food and gastronomy are powerful social constructs that shape and exchange national identities and global narratives. Rather than being solely material commodities, food, gastronomy, and culinary traditions carry symbolic meanings that influence, persuade and attract how nations perceive themselves and others, through the soft-power nuances exercised by all-sized countries (Nye, 2005). In Social Constructivism, the development of national campaigns, including branding campaigns, based on cultural awareness (which includes gastronomy), drives political action more than purely economic power or political forces (Sørensen and Møller, 2025). With this theoretical underpinning in sight, cultural diplomacy and governance action towards the construction and implementation of gastrodiplomatic public policies gain special relevance from the perspective of identity mobilisation and diffuse public attraction to a nation’s cause (Cabral et al., 2024b). Objectively, culinary diplomacy could also be theoretically founded in this IR theory. In summary, when examining the concept from a broader interpretive perspective, the promotion of national cuisines in official meals can be applied across various forms of diplomatic relationships. Furthermore, the Constructivist theory posits that international relations are influenced by dynamic social interactions, collective identities, and the significance of ideas, positioning these elements at the core of this form of culinary diplomacy.

2.4 Portuguese foreign policy

In a general manner, foreign policy can be defined as a set of tangible “objectives, strategies and instruments” (Freire and Vinha in Lopes, 2024, p. 72) expression of the decisions made by a government, reflecting its agenda-setting operations, that govern a state’s relations with external actors—be them other states, international organisations, or non-state actors—to achieve national interests (Bojang, 2018), as well as the “unintentional results of those actions, to answer to a current or future environment” (Freire and Vinha in Lopes, 2024, p. 72). According to Freire and Vinha, foreign policy necessitates a “bidirectional relationship between the internal and external” aspects of a country (Freire and Vinha, 2015, p. 15).

Pequito Rebelo, through the famous phrase “Portugal is Mediterranean by nature and Atlantic by position” (Pequito Rebelo in Ribeiro, 2021, p. 63) encapsulated the essence of Portugal’s complex positions in the world, reflecting its geographical, geopolitical, historical, and strategic versatility. This multifaceted framework serves as a foundational perspective for understanding the characteristics of Portuguese foreign policy.

Historically, Portuguese foreign policy has been shaped by the country’s geographical position as well as its cultural settings and heritage, recognised as a stable policy (Lopes, 2024) and characterised by its continuity throughout various historical periods and changes in domestic actors (Silva, 2019). Teixeira (2004, 2015) identifies three distinct models of Portuguese foreign policy: the first model, the classical model, and the international insertion model.

The first model prevailed until the 15th century and was characterised by the Iberian Peninsula as a hegemonic space and the centre of global trade negotiations. The second model, known as the classical model, spanned from the late 15th century to the period of democratisation and accession to the European Union (1974–1986). This period marked a significant transition in Portuguese foreign policy, accompanied by the construction and dissolution of geopolitical alliances (with the United Kingdom, the United States of America, former colonies, and European countries), world conflicts, decolonisation processes, the rise of international institutionalism, and the intensification of global trade and human mobility. Notably, European integration introduced a new set of geopolitical concerns, as well as internal concerns, thereby affirming the significance of internal dimensions in the execution of foreign policy. These concerns pertained to the formation of a European mindset that needed to be integrated into foreign policy execution during a convergence process that experienced internal fluctuations with external expressions, including moments of “euroenthusiasm” and “euroscepticism,” as well as the impacts of economic crises (Teixeira, 2017). The third model, from 1986 to the present, is referred to as the new model of international insertion and has positioned Portugal within a multilateral economic and institutional framework as a mediator for human, cultural, political, and diplomatic development. This occurred despite the shifting power balances within Europe and globally. While these concerns began to be institutionalised in 1975, through the establishment of the “Coordination Commission for Negotiations in the Economic and Financial Domain”,1 this era, as described by Teixeira, has introduced numerous diplomatic, political, and non-state actors focused on cooperation—particularly within the framework of the Community of Portuguese Language Countries—as well as economic, scientific, technological, and cultural development interactions (Pavia and Monteiro, 2013; Teixeira, 2015).

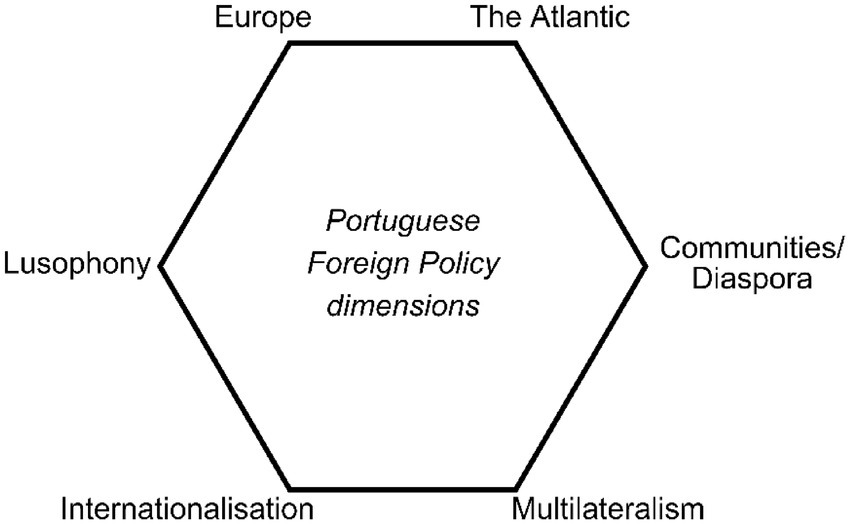

In summary, Augusto Santos Silva has recently illustrated that the fields of Portuguese foreign policy form a hexagonal model, highlighting the external and geopolitical concerns that drive Portuguese foreign action, as outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The “Hexagon” of Portuguese foreign policy dimensions. Source: Adapted from Silva (2020).

It is noteworthy that not only geographic but also cultural spaces are vital for the affirmation of Portuguese foreign policy. The Portuguese diaspora and the Portuguese communities worldwide, along with Portugal’s involvement in organisations such as UNESCO, since 1965,2 illustrate a shift in external policy wherein these two aspects have begun to function as soft power instruments for the implementation of both a cultural diplomacy and a public diplomacy strategy that is already incorporated into Silva’s hexagon model. Portuguese soft power increasingly emphasises diplomacy, mediation, and cultural assets, such as the diffusion of language, while placing less emphasis on militarism (Teixeira and Mendes, 2020). Notwithstanding, Lopes (2024) call on budgetary restrictions on cultural diplomacy strategies, which emerged after the 2011 economic crisis, shifting the focus of the Portuguese soft power into economic diplomacy.

The aforementioned factors have influenced the country’s execution of its foreign policy during periods of quietness, social turbulence and uncertainty, as well as under monarchic, dictatorial and democratic regimes.

3 Methodology

This study employed a qualitative, historical–documentary approach to examine the diplomatic significance of official meals in Portugal between 1910 and 2023. The analysis focused on how menus and dining practices reflected geopolitical contexts, foreign policy objectives, and the use of gastronomy as a tool of cultural and culinary diplomacy.

3.1 Archives research

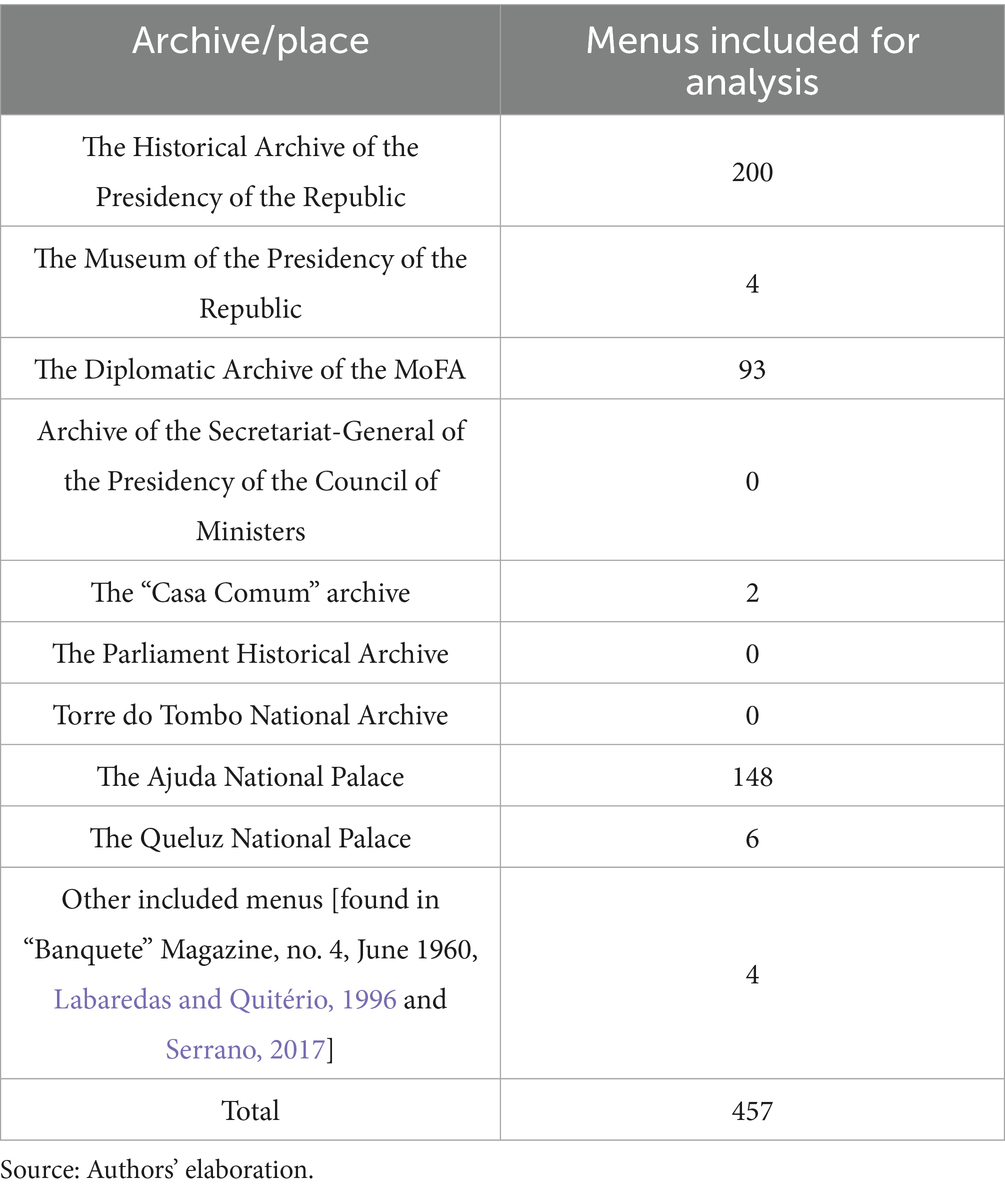

Research was conducted in 9 different public archives in Portugal between May 5th, 2023, and January 20th, 2025. There were searches at the Historical Archive of the Presidency of the Republic, The Museum of the Presidency of the Republic, The Diplomatic Archive, by the Portuguese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, The Archive of the Secretariat-General of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers, The “Casa Comum” archive, as the repository of the former President Mário Soares’ documents held by Foundation Mário Soares and Maria Barroso, The Parliament Historical Archive, The Torre do Tombo National Archive, The Ajuda National Palace and The Queluz National Palace.

3.1.1 Research string and inclusion criteria

Online research examined the first seven archives’ catalogues. The last two archives were searched in person due to the absence of online catalogues. Searches in Portuguese included: ementa or menu (menu), banquete (banquet), jantar (dinner), and almoço (lunch) across all available fields.

The inclusion criteria required that the documents pertain to official meals hosted by sovereign Portuguese bodies (e.g., the Presidency of the Republic, the Prime Minister) for foreign dignitaries, whether in Portugal or abroad, and that they highlight Portuguese gastronomy to non-native guests. Both banquets and more intimate diplomatic meals were considered. Items included menus, programs, guest lists, and press descriptions when available.

3.2 Supplementary data sources

To enrich the archival data, the research was supplemented with bibliographic analysis. To fully understand the social phenomena surrounding the State’s visits and dining, it was complemented with contemporaneous press coverage to ascertain the configurations of meals and/or State visits, namely through the Diário de Lisboa newspaper.3

Most of the references were retrieved from archival sources. However, the authors identified four additional menus during the literature review that warranted inclusion. These menus, on the visit of President Sukarno of Indonesia, were published in Banquete Revista Portuguesa de Culinária Magazine (issue 4, 06/1960) (two menus), in Labaredas and Quitério (1996) (one menu for NATO), and in Serrano (2017) (one menu for Germany). Furthermore, the authors included the diplomatic meals served to Queen Elizabeth II by Lisbon City Hall and the University of Évora in 1985. Although these meals were prepared in different contexts, they formed part of the official visits coordinated by the State Protocol and the President of the Republic of Portugal. The authors contend that these meals constitute valuable Supplementary material that enhances the archival content, considering their significance in Portugal’s history of diplomatic meals.

3.3 Data analysis and interpretation

Each document was catalogued and assigned an identification code (ID) to facilitate chronological and geopolitical mapping. A total of 457 diplomatic meals were included in the analysis. The retrieved data was compiled into an Excel database. The date, type of meal, source, reference, country/organisation and any additional information of each meal was registered into the database.

A content analysis was performed. Menus and related documents were organised according with their chronological context (historical and political period), geopolitical significance (guest country, international organisations, alliances, conflicts), culinary identity (French vs. Portuguese styles, use of national/regional products, territorialisation of cuisine, gastropolitical symbolism), sociocultural elements (rituals, venues, symbolic references, guest preferences, press narratives).

The analysis combined the diplomatic and gastronomic significance of each meal within Portugal’s broader macro-geopolitical context. By examining the menus, guest lists, and historical settings, the study sought to understand how each event reflected the foreign policy zeitgeist and Portugal’s evolving international relations.

4 Results and discussion

The archival research identified 457 diplomatic meals in Portugal, as shown in Table 1. The complete list is included in Appendix 1.

4.1 Geopolitical environments

Each meal holds diplomatic and geopolitical significance, impacting Portuguese international relations and reflecting Portugal’s foreign policy zeitgeist. This analysis combines the diplomatic and gastronomic significance of the official meal within Portugal’s macro-geopolitical context.

4.1.1 The diplomatic meals of the first republic (1910–1926) and of the military dictatorship (1926–1933)

The first nine diplomatic meals in the sample, from 1920 to 1932, correspond to two distinct historical periods in Portugal. In the post-1st World War, the First Portuguese Republic (1910–1926) marked a heterogeneous historical period denoted by governmental, political, and financial instability in the country (and the world). Our sample includes only two meals. These are the visits of Prince Albert of Monaco (ID1, Monaco), who had a circumstantial nature during his scientific expedition to the Azores Sea, and a British military mission (ID2, United Kingdom). Also, the period of the Portuguese Military Dictatorship (1926–1933), from the perspective of diplomatic meals (which includes 7), reflects the search for international alliances amidst the sociopolitical upheavals of an unproductive republic (Martins, 2001). During this period, few guests were invited to Lisbon, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Distribution of sampled diplomatic meals from the first republic (1910–1926) and military dictatorship (1926–1933) periods in Portugal. Source: Authors’ elaboration. Map credits: datawrapper.de.

Noteworthy meals include those with Spain (ID4) and Italy (ID9), demonstrating the historical Iberian proximity during the Ibero-American Exhibition in Seville and the empathy shown towards Mussolini’s fascist ideals through the presence of his Air Minister, Italo Balbo, in Lisbon, whom the Fascio of Lisbon4 highly acclaimed. Additionally, the presence of the United Kingdom (ID8), following the Madeira uprising, demonstrated the strength, support and continuity of the Anglo-Portuguese alliance. Likewise, the absence of international organisations at diplomatic meals could reflect that this period marked the early stages of their formation and establishment. Notwithstanding, lavish 9 and 10-course meals rooted in French cuisine persisted. This opulence contrasts with the financial control established by the Minister of Finance (Oliveira Salazar, future Portuguese dictator, 1888–1970), who was responsible for overseeing every aspect of the diplomatic meals, from “the silverware, the China, the glassware”,5 to the selection of plants and its watering service and the hiring of staff. Boldly, in our interpretation, and due to the facts, we assert that there was no intention to showcase Portugal’s cuisine through the diplomatic meals of this period. However, it is the first time that “Selle de veau à la Portugaise” appears in the banquet served to Her Royal Highness Infanta D. Eulália of Bourbon (ID4).

4.2 The Estado Novo (1933–1974) and the three different phases of diplomatic meals

The Estado Novo dictatorial period (1933–1974), led by Oliveira Salazar as the President of the Ministers Council until 1968 and followed by Marcello Caetano until the Revolution on April 25, 1974, counted 53 diplomatic meals. According to diplomatic records, this period can be subdivided into three distinct periods.

a) The Estado Novo on the table: from the foundation to the NATO entrance (1933–1949)

In the first Estado Novo period, 1933–1949 (9 meals), much of the foreign policy was centred around Salazar, as he took on the Minister of Foreign Affairs role from November 1936 to February 1947. His focus was “the preservation of peace and the maintenance of the territorial integrity of the country and its colonial empire” (Pereira, 2023, p. 11). Aside from this colonial urgency, the exploitation of Portugal’s significant historical achievements defines the tone of Portuguese diplomacy and propaganda, reflected in the diplomatic meals.6 The presence of South Africa in Lisbon (ID12, ID13), in one case on its way to London, reflects the pressure exerted by international actors on Portuguese colonial policy. Internally, the presence of the Minister of Indigenous Affairs of South Africa in 1939 is justified by the need to resolve issues “that concern both countries”.7 Two events continue to shape the agenda of diplomatic meals in Portugal. The “Exposição do Mundo Português” (Great Exhibition of the Portuguese World) and the “Comemorações dos Centenários” (Centennial Celebrations) (both in 1940) served as the backdrop for diplomatic meals, with international honorary guests such as the Special Embassy of Brazil at the event (ID14) and members of the Delegations and Centennial Celebrations (ID15). Despite celebrating Portuguese identity, there are no references to national products or cuisine in the diplomatic menus.8 The Spanish presence is also significant, particularly in 1940 (ID16). This is not only due to Spain’s support for the event or its military connection, highlighted by the decoration of Spanish soldiers in commemoration of the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Salado (1340), but also because, about a year earlier, the Luso-Spanish Treaty of Friendship and Non-Aggression (later the Iberian Pact) had been signed. In this friendly environment, Spain thus became a frequent honorary guest in Lisbon (Tíscar, 2014).

The presence of the Vatican and the Catholic Church delegations in national diplomatic corridors is not negligible. It served two essential purposes: the search for direct diplomatic support from the Church and indirect support from Christian states, which was important for national affirmation. On the other hand, the directives shaping the citizen’s role were firmly based on the influence of the Catholic Church. Thus, over a five-year period (1946–1951), the Vatican made three formal visits to Portugal. The first (ID17), 6 years after the Concordat with the Holy See was signed, took place in 1946, and the last (ID21) in 1951, marking the conclusion of the Holy Year and the commemoration of the Marian apparitions at Fátima. The menu remained unchanged for all three visits. On each occasion, turkey (with truffles in two of the three occasions) and asparagus were served to the Papal Legation, and dessert consisted of pudding and fruit.

Finally, another detail should not be ignored from the perspective of international relations. Our sample does not record any meals related to the political movements related to Portugal’s accession and ratification of the North Atlantic Treaty (currently NATO) in 1949. The first diplomatic meal for NATO was served in Lisbon in 1952 (ID23) by Mestre João Ribeiro from the Aviz Hotel, featuring trout from the Minho River and French cuisine preparations.

b) From NATO to international and social agitation due to colonialism policies (1950–1961/62)

The second Estado Novo period (1950–1961/62) comprises 30 diplomatic meals. It spans from the post-accession to NATO period until the social agitation period, known as the anni horribiles for the Estado Novo regime. The effects of the “Santa Maria” liner assault, the outbreak of the Angolan War in 1961 and the Portuguese academic crisis in 1962 were sonorous anti-regime events upon which Portuguese domestic and foreign policy practices kept unveiling (Ferreira, 2012), although with considerable mass attention to Portuguese politics. Considering the national understanding of colonial territories (by then already referred to as “overseas provinces” (Santos and Pereira, 2022), vocal contestations resonated in Lisbon within the framework of official visits and, of course, in diplomatic meals, a privileged place for persuasion and attraction games.

A notable example of this situation is the state visits of Indonesian Head of State Sukarno (ID36, ID41, ID42, ID43), considered by the contemporary press as a “political indoctrinator of undeniable originality”9 who firmly opposed any colonial perspectives (Weatherbee, 1966), visited Portugal twice (1959 and 1960), and was served an almost complete French meal (except for the asparagus from Sanguinhal). On the contrary, the State’s visit by Emperor Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia (ID39, 1959) seems to respond to an international support claim, demonstrating that Portugal’s global presence, through its historical expansionist policy, was not entirely harmful. This was confirmed by the press during the Ethiopian Emperor’s visit, with Diário de Lisboa newspaper affirming that,

“Although without political objectives, the journey of the Emperor of Ethiopia holds the beautiful significance of demonstrating, four centuries later, the gratitude of the Ethiopian people toward a country that helped defend its independence against Muslim invaders and introduced it—without politically or economically dominating it—to the construction techniques and decorative arts practised in 16th- and 17th-century Europe”. Source: Diário de Lisboa No. 1315810 (bolds of our responsibility)

Diplomatic practices during this period have expanded to include cultural and economic diffusion, although the essence of geopolitical diplomacy remains unchanged. Examples include the Pakistani President’s visit in 1957 (ID33), Emperor Haile Selassié I of Ethiopia in 1959 (ID39), the Thai Kings in 1960 (ID48), and Oliveira Salazar’s official dinner for the European Free Trade Association delegation in 1960 (ID45), of which Portugal was a founding member. These instances reflect an increase in bilateral relations promoting trade and cultural ties.

Meanwhile, it is worth emphasising that at diplomatic tables (where Brazil and the United Kingdom continue to have a regular presence during this period, with 6 and 5 meals, respectively), a fundamental shift occurs in the inclusion and promotion of Portuguese products, territory and the communication of national culinary regionalism and an early sense of gastronationalism (DeSoucey, 2010).

This change is readable through a combination of several elements. Primarily, the consolidation of the usage of the expression “à moda de” (“in the style of…”) or “à” (“-style”) in diplomatic meal menus was found in the sample 139 times.11 On the one hand, this practice induces the mental representation of a culinary imaginary and the serving of a dish as it is supposedly and traditionally prepared in a specific place, according to a unique set of characteristics and preparation methods of that place (Csergo and Etcheverria, 2020).

On the other hand, this idea of culinary practices rooted in tradition works as a “political device” for political communication (Gal, 1998). It is performed in diplomatic meal settings by the menu. This territorialisation aligns with one of the guiding principles of the Estado Novo, which is to root governing action in the field, specifically in the rural areas of the country. Moreover, associating a culinary process with a place or even a person, in the case of honorific cuisine (Soares, 2018), creates a code that could or could not be widely spread, recognised and culinarily understood. A well-codified and widely recognised example is the “Bulhão Pato-style,” meaning culinary preparation is sautéed and prepared with garlic, coriander, and lemon (found in 6 diplomatic meals). Conversely, “Imperial-style” or “à l’Aviz” is found, respectively, in 4 meals and one meal, requiring additional meaning and context for the successful communication of the course details.

Those codes could represent any brigade member’s creative and inventive process, which may lack wide recognition, and could even be polysemic. For instance, the introduction of the word “imperial” to describe a pudding in the official dinner offered to Emperor Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia (ID39, 1959) seems to create a rapport with the honoured guest, rather than symbolising any culinary preparation. The same happened with the Lombo de Vaca à Dom Henrique (beef loin Dom Henrique-style) served to the Duke of Edinburgh at Paço dos Duques de Bragança in Guimarães (ID62, 1973), creating a nexus between the venue and the historical aspects deeply rooted in the foundational myth of the Estado Novo. This association propaganda was intensely evoked in the local press.12

On the opposite end, the inclusion of imperial ice cream in the European Free Trade Association official luncheon (ID45, 1960) seems to transmit a sense of geopolitical greatness and vast governing capacity when international organisations were approving formal resolutions against the imperial ideology of Portugal (Rodrigues, 2004). Despite this configuration, the objective remains to transport the diner to a gastronomic imagination, which may or may not be codified in culinary practice but whose ultimate goal is to demonstrate that the dish served is prepared as it would be in the referenced location.

Secondly, through the diplomatic meals served aboard the inaugural voyage of the new Portuguese liner “Santa Maria,” hosted by the Minister of the Navy, Américo Tomás (who would later become President of the Republic in 1958). Brazilian President Getúlio Vargas, on November 25th, 1953, was gifted with a Banquet (ID24) in his honour aboard Paquete Santa Maria. This meal included, for the first time in our sample, Queijo da Serra (Serra cheese), alongside other Brazilian cheeses. Six days later, on the same Paquete Santa Maria route and also on board, the Minister headed to Argentina, where a Porto de Honra (Porto of honour) was served to President Perón, and a meal offered that same afternoon to the Argentine Government on December 1, 1953 (ID25) (also including Queijo da Serra). The Brazilian and Argentine meals included a culturally relevant cantiga de amigo, a medieval Galician-Portuguese poem, on the menu cover, demonstrating an understanding of the menu as a means of cultural diffusion. The “Santa Maria” liner then set sail for Uruguay, where, the following day, an exhibition of Portuguese wines was organised aboard the ship, as reported by the Diário de Lisboa No. 1135.13 The Argentine 9-course meal was a turning point, marking the simplification of menus from that moment onward, with diplomatic meals reduced to just four or five courses (typically a soup, a fish dish, a meat dish, a sweet dessert and fruit).

In our sample, the gastronationalism of gastronomic moments and their evidence of sharing territory in diplomatic meals, meaning the communication and the inclusion on the menu of certain food products’ specific origins, emerges during this period. Notably, the first references pointing to a territorial connection and origin of a national product occur in the official dinner served to Queen Juliana of the Netherlands (ID26) in November 1955, which featured a Lagosta de Sesimbra (Sesimbra lobster) and Ananás dos Açores (Azorean pineapple).

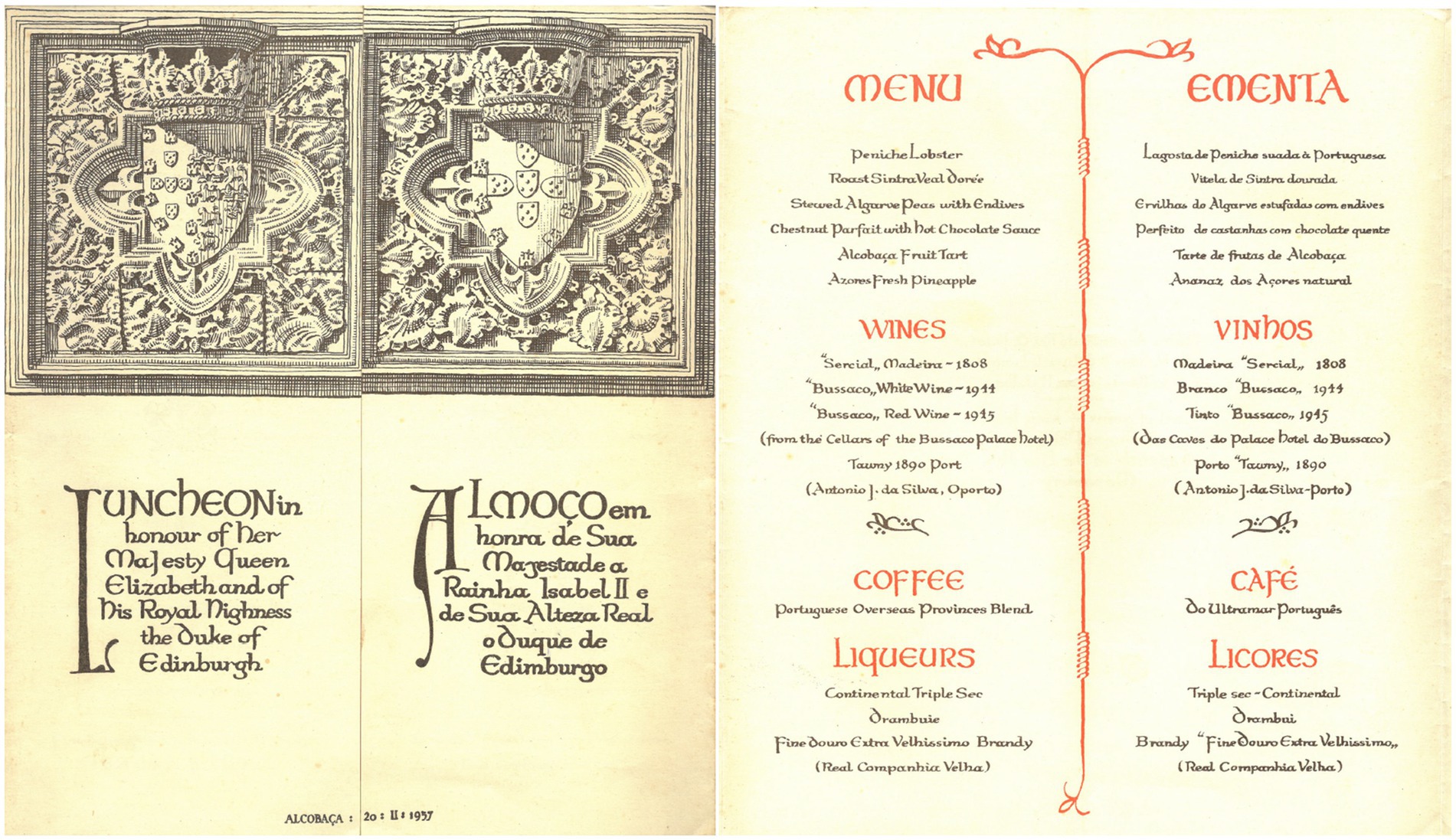

This trend would be followed by several other diplomatic meals in the upcoming meals, namely the Luncheon14 for Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom (ID31) served in Alcobaça (Portugal) in 1957, during the Queen’s reciprocal visit to Portugal as a reciprocity for the visit to the UK of President Craveiro Lopes in 1955. At this Luncheon, the entire menu was designed to convey a sense of territory and “Portugality,” serving as a broad overview to understand the Portuguese regime’s orientation towards Portuguese gastronomy. It is essential to note that this meal was conceived by Francisco Lage (1888–1957) and represents a culinary vision of a gastronomic country centred on luxury products. Lage was an ethnographer of the regime and an SNI15 official who viewed Portuguese culinary and gastronomy as essential to the affirmation and configuration of Portuguese regionalism (Barthez, 2019, 2021). The ethnographer thus reflects the regime’s view of Portuguese cuisine. Lage had prepared the menu for foreign journalists during the “Great Portuguese World Exhibition” (1940) and was appointed by António Ferro, director of SNI, to prepare this meal for the Queen (Barthez, 2016). The menu, a piece of art itself (Figure 3), registers a meal fully cooked in situ in the old kitchens of the Alcobaça Monastery and was classified as “simple, yet marked by good taste”.16 Lagosta de Peniche suada à Portuguesa (Peniche Lobster stewed in the Portuguese style), Vitela de Sintra dourada (Golden Veal from Sintra), Ervilhas do Algarve estufadas com endives (Stewed Peas from the Algarve with endives), Tarte de frutas de Alcobaça (Fruit Tart from Alcobaça), Ananaz dos Açores ao natural (Azorean pineapple served fresh) were part of the menu, among others. To finish, a rare Café do Ultramar Português (coffee from Portuguese Overseas) was served. Despite the geographical understanding of Portugal at that time, which was understood as mainland territories and overseas provinces, no other reflections of colonial food references have appeared in the sample.

Figure 3. Menu of the “Luncheon in honour of her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II and his Royal Highness the Duke of Edinburgh” in Alcobaça (Portugal), February 20th, 1957. Source: Parques de Sintra-Monte da Lua, Ref. Almoço_Alcobaça_Rainha Isabel_1957.

The 1957 visit of Queen Elizabeth II also illustrates the profound respect for the preferences of the honoured guests. Notes about the installation of Queen Elizabeth II and the Duke of Edinburgh at the Palace of Queluz reveal that, on the day of their arrival, the Hotel Aviz dispatched to Queluz a team consisting of a “cook, a commis, and a butler,” and that the Queen’s lunch that day would already be served at the palace. The British Embassy noted, “The Queen is very fond of Portuguese canned sardines, and a well-selected variety should be included in the hors d’oeuvres (…), as she desires a very light and simple lunch”.17

This preference may have been shaped not by cultural reasons, but by circumstantial and hypothetical contact with Portuguese export products. According to Henriques (2023), during World War II, the United Kingdom was the primary export market for canned sardines. Hence, Queen’s exposure to combat rations during her service in the British Army during World War II (that included canned fish) or the fact that 10 years earlier, the British Royal Family had also adhered to rationing programs in place in the United Kingdom, which included canned fish, could explain her fondness.

The 1957 visit of Queen Elizabeth II to Portugal is still remembered today in diplomatic circles for many aspects, but for two main gastronomic ones.

The first aspect is the Galinha à Moda do Convento de Alcântara (Chicken at Convento de Alcântara-style) dish served during the official dinner on February 18, 1957 (ID28) at the Palácio da Ajuda. In diplomatic terms, and according to our results, poultry was not (and is still not) considered a delicacy befitting a royal table. However, it is important to note the gastronomic and culinary evolution of this dish, which was included by Escoffier in Guide Culinaire (1903) as Faisan à la mode de Alcântara (pheasant at Alcântara-style) (Escoffier, 2015) and later renamed Perdizes à Alcântara (Partridges at Alcântara-style) by Olleboma (Bello, 2021).

The recipe was popularised by Chef Mestre João Ribeiro, who featured it at diplomatic tables such as this one, where he served as Head Chef. The justification for this service can be found in Labaredas and Quitério (1996) and the criteria distinguishing haute and low cuisine established by Goody (Sobral, 2014), mainly due to the use of luxurious and exclusive raw materials such as foie gras or truffles. According to those authors, this dish might be one of the few Portuguese haute cuisine dishes formally codified as such, which explains its inclusion on the Queen’s table.18 At diplomatic tables, and according to our sample registers, the dish was served at least six more times, prepared with variations using pheasant, chicken, partridge, or duck (ID1, ID28, ID58, ID202, ID287, ID352).

The second aspect concerns the exclusiveness of the Queen’s consumption of Portuguese Salmon from the Minho River. Portuguese salmon, also contemporarily considered an exquisite and rare food product in the Minho region, whose decline was locally felt since the first half of the 20th century (Guterres, 2020), was served at the Queen’s banquet in 1957 (ID28). Moreover, according to our sample, it was served five additional times until 1973 (ID28, ID33, ID45, ID59, ID61). Curiously, the Duke of Edinburgh was the last guest of honour to consume such a product at diplomatic tables in Sintra, in May 1973 (ID61, in Sintra Palace, as part of a salmon pudding).

c) Portugal 1962–1974, a confirmational period?

The consumption of exclusive products positions the diplomatic tables as a locus of distinctiveness and delicacy for a culinary item that was once considered a national extravagance but is currently extinct. This exclusivity and abundance occasionally contrast with social scarcity scenarios,19 as described below.

We can affirm that political (and gastronomic) confirmations mark the period from 1962 to 1974 (with 14 meals). Strategic and long-standing partners visited and validated Portugal, such as Brazil (5 meals), the United Kingdom (3 meals), and the Vatican (2 meals). Politically, diplomatic ties and friendships were strengthened during a period of intense, multifaceted opposition to Portugal’s continued colonial policies. This was expressed by two former Brazilian Presidents, Senator Juscelino Kubitschek de Oliveira (former Brazilian President) (ID49, 1963) and Marshall Alencar Castello-Branco (ID55, 1967) and the Spanish Government Vice-President, General Muñoz-Grandes (ID52, 1965).

According to our sample, Senator Kubitschek de Oliveira was the first diplomatic guest to sit on a Portuguese diplomatic table following the invasion of the Indian Union of the overseas territories of Goa, Daman and Diu in December 1961. The Senator claimed to support Portugal firmly during his visit to inaugurate a monument in honour of Pedro Álvares de Cabral in Belmonte. This presence is thus symbolically marked by logocentric and non-verbal communication surrounding Portuguese foreign policy and the celebration of significant events. Conversely, he received Chickens Portuguese-style for the official Banquet.

Besides, the “love for Portugal,” as an image of this support, is shared among Brazilian and Spanish visiting guests. Former Brazilian president Marshall Castello-Branco, on a European trip, stated, “Upon arriving in Lisbon, I feel equally Portuguese and Brazilian”.20 Also, these Iberian brotherhood sentiments were emphatically expressed by General Muñoz-Grandes, upon his arrival in Portugal in 1965, when he declared “With all my senses, I love deeply, and I suffer and rejoice as, over time, adversity or fortune accompanies you [Portugal]”,21 illustrates the tone of diplomatic visits during this period.

With Salazar’s removal and the appointment of Marcello Caetano (1906–1980) in 1968, the Estado Novo regime (and the country) entered a new phase of proposed openness to the world, known as Marcelism, which also included a renewed effort to strengthen Iberian relations. Marcello Caetano would later confirm this with his visit to Madrid in 1970 (Cabrera, 2019). Previously, as Minister of the Presidency and head of the SNI, regarded as the “pedal of the nation” (Caetano in Cabrera, 2019, p. 226), Caetano indirectly engaged with gastronomy as a tool for political configuration, primarily through the contributions of Francisco Lage.

After a long trajectory of unity between Portugal and the USA centred on the Lajes Air Base due to its strategic position in the Atlantic, and namely in the post-World War II period, Marcello Caetano hosted the 1971 USA-France summit with President Nixon and President Pompidou on Terceira Island (Rocha, 2023). The summit underscores the geopolitical importance of Portugal and its territory during a Cold War increasingly characterised by negative externalities. On the gastropolitical level, it is essential to note the presence of Portuguese elements at this diplomatic table, as evident in the official dinner served at Palácio dos Capitães-Generais, albeit modestly (as we will see below and as it remains throughout our sample), given the predominance of French culinary influences.

During this period (and the following one), some of the rarest food products were recorded as being served at the diplomatic table and served to hundreds of attendees of diplomatic meals. Interestingly, some of these culinary delicacies found on diplomatic tables also involve the United Kingdom’s sovereigns (but not exclusively), contrasting with the Sovereign’s fondness for canned sardines. Besides the already mentioned salmon pudding, Turtle Soup was consumed at the Banquet in honour of the Duke of Edinburgh at the Ajuda National Palace in June 1973 (ID60). Also, in a rare appearance, trouts from São Miguel Island (Azores, Portugal) were served during the official dinner of the cited USA-France summit, hosted by Portugal in Terceira Island (ID57, 1971) to President Nixon of the USA and President Pompidou of France. This meal featured an utterly national menu, with a variety of Azorean and mainland Portuguese-origin products. It embodied a semiotically designed diplomatic capacity [due to the position of Terceira Island and the geopolitical functions and importance of the Azorean islands (Andrade, 2013)] but also an hymn to Portuguese cuisine in a key moment during the Cold War period. This is especially relevant for the analysis of the geopolitical importance of the region in the Atlantic, as well as for the Portugal-USA and USA-Europe bilateral and multilateral contexts and relations.

The inclusion of moments showcasing Portuguese culture, and specifically, gastronomic culture, in proportion to the periods preceding and following, may be due to the impact of some difficulties in sourcing more exclusive products for the diplomatic tables. These difficulties, which might have been driven by the economic and energy crises triggered by the Cold War, lasting in Portugal beyond the 1970s, could help to explain the preference for the service, e.g., of locally-sourced Robalos de Sesimbra (Sea bass from Sesimbra) (Brazil, ID53) to Brazilian elected-President General Artur Costa e Silva on the exact day when Diário de Lisboa newspaper transmits sharp concerns about the lack of fish and its scarcity in Sesimbra.22

On one of the rare occasions when a Portuguese political leader hosted abroad a meal in honour of a Head of State, such as the one that took place at the Hotel Nacional in Brasília offered by President Américo Tomás in the honour of Brazilian President Emílio Garrastazu Médici (ID58, 1972), it is of utmost importance to explore the configurations of the dinner to understand better the aforementioned confirmation of the Portuguese culture’s presence.

“An Arabian tent, with Persian and Portuguese rugs, Brazilian flowers and fruits, in addition to antique Portuguese furniture pieces, were the main points of the decoration at the Hotel Nacional for the reception of President Tomás to President Médici. The project was authored by Portuguese decorator Fausto de Albuquerque, who, at the last minute, removed the chandelier from the tent and set it up in the hotel entrance hall because the piece was too low, and President Médici is very tall. THE DINNER. For each guest, the Portuguese Embassy’s Ceremonial placed a waiter. There were also many servers, so 120 men served the 116 guests. The menu for the banquet consisted of the following: smoked salmon, Alentejo cream, pheasant à la Alcântara, and strawberries in Port wine. To maintain the grandeur of the event, full of luxury and refinement (mandatory attire: diplomatic tailcoat), the Portuguese Embassy had special outfits made for the waiters, based on mustard-coloured dolmans, matching the table service”. Source: Jornal do Brasil No. 15, p. 323

Besides the sonorous Faisão à Alcântara (Pheasant Alcantara style), with its truffles, foie-gras and Porto wine served in Brazil, the Arabic tent, the decoration with Persian and Portuguese rugs as well as the investment in waiters uniforms in the colour of the table arrangements (which expressively accounts for 120 waiters[!] for 116 Banquet attendants), crown the meals as vehicles for the dissemination of political messages, here associated with a sense of Portuguese long-lasting identity, based on relevant historical moments for the Estado Novo regime, such as the Discoveries period, which are semiotically communicated (Teughels, 2021).

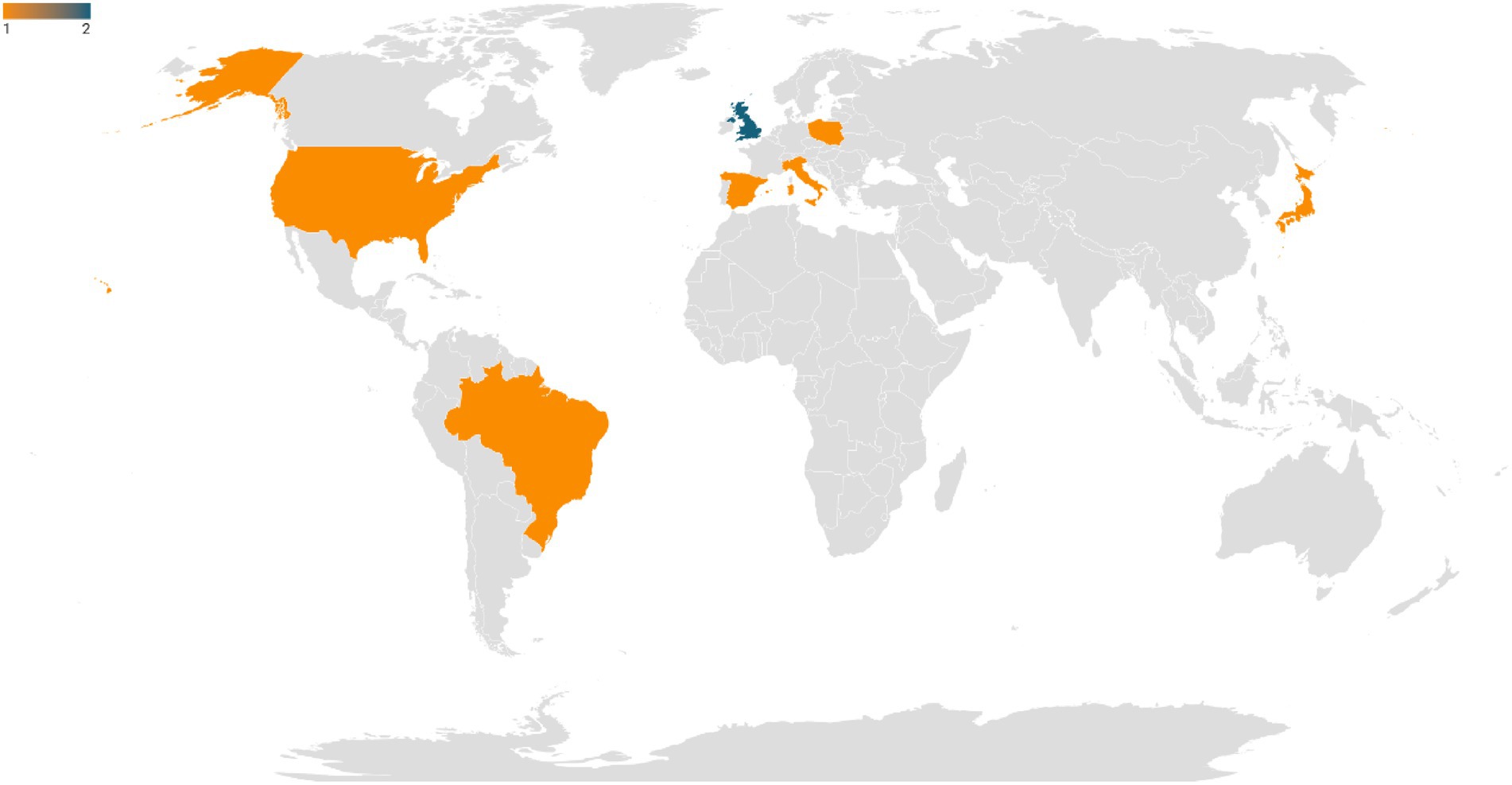

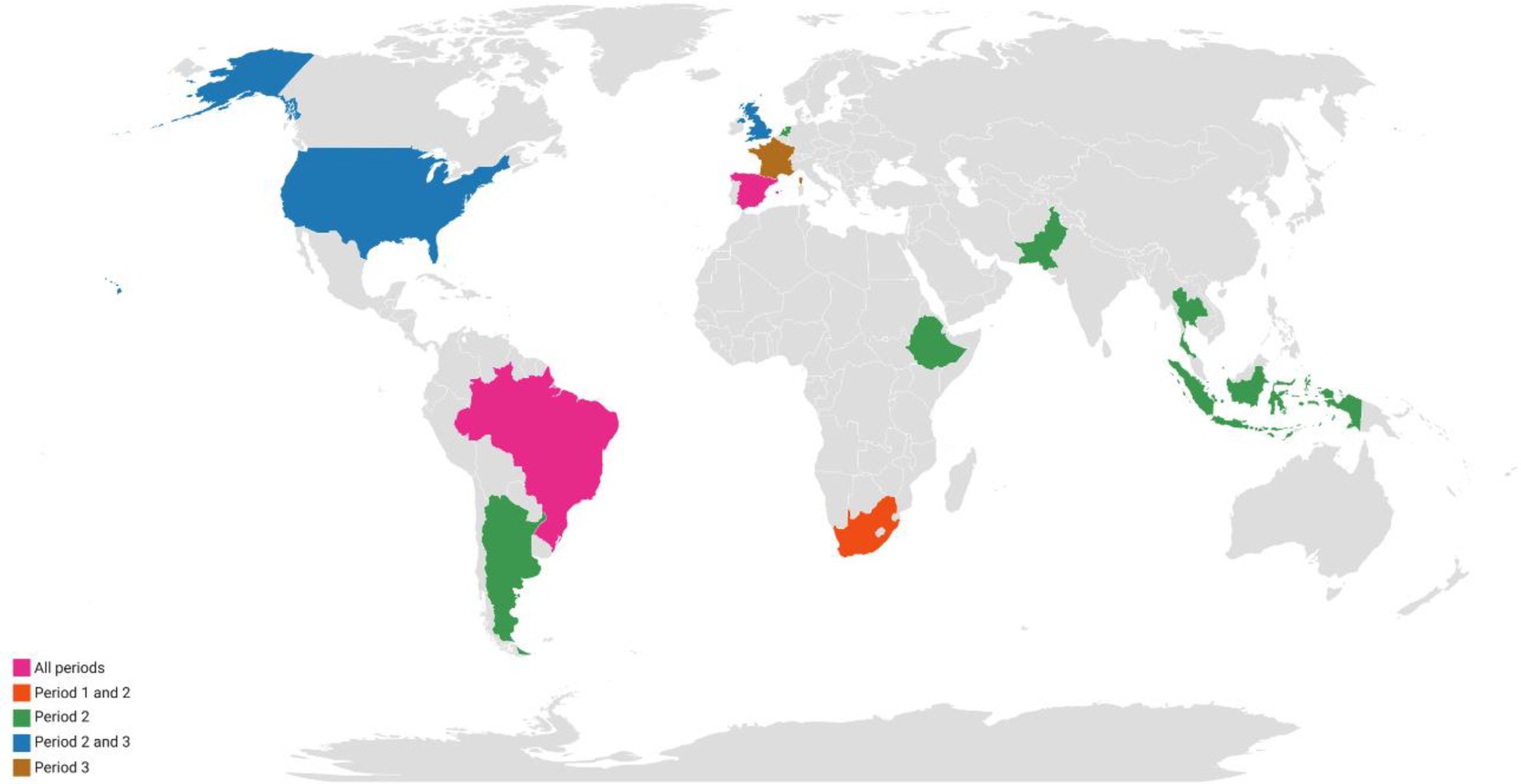

Finally, Figure 4 shows the world dispersion of guests considered in our sample during the Estado Novo regime and according to the analysed period of presence in Portugal. To these countries, the visits were made by Members of the Centennial Commemorations’ Delegations (for the Great Exhibition of the Portuguese World, Period 1), EFTA, the Order of Malta, the accredited Diplomatic Corps in Lisbon (Period 2), and NATO (Periods 2 & 3).

i. Time for national and international resettlements: from the Revolution to the pre-Expo 1998 (1974–1997).

Figure 4. Distribution of included diplomatic meals in the Estado Novo period in Portugal (1933–1974). Source: Authors’ elaboration. Map credits: datawrapper.de.

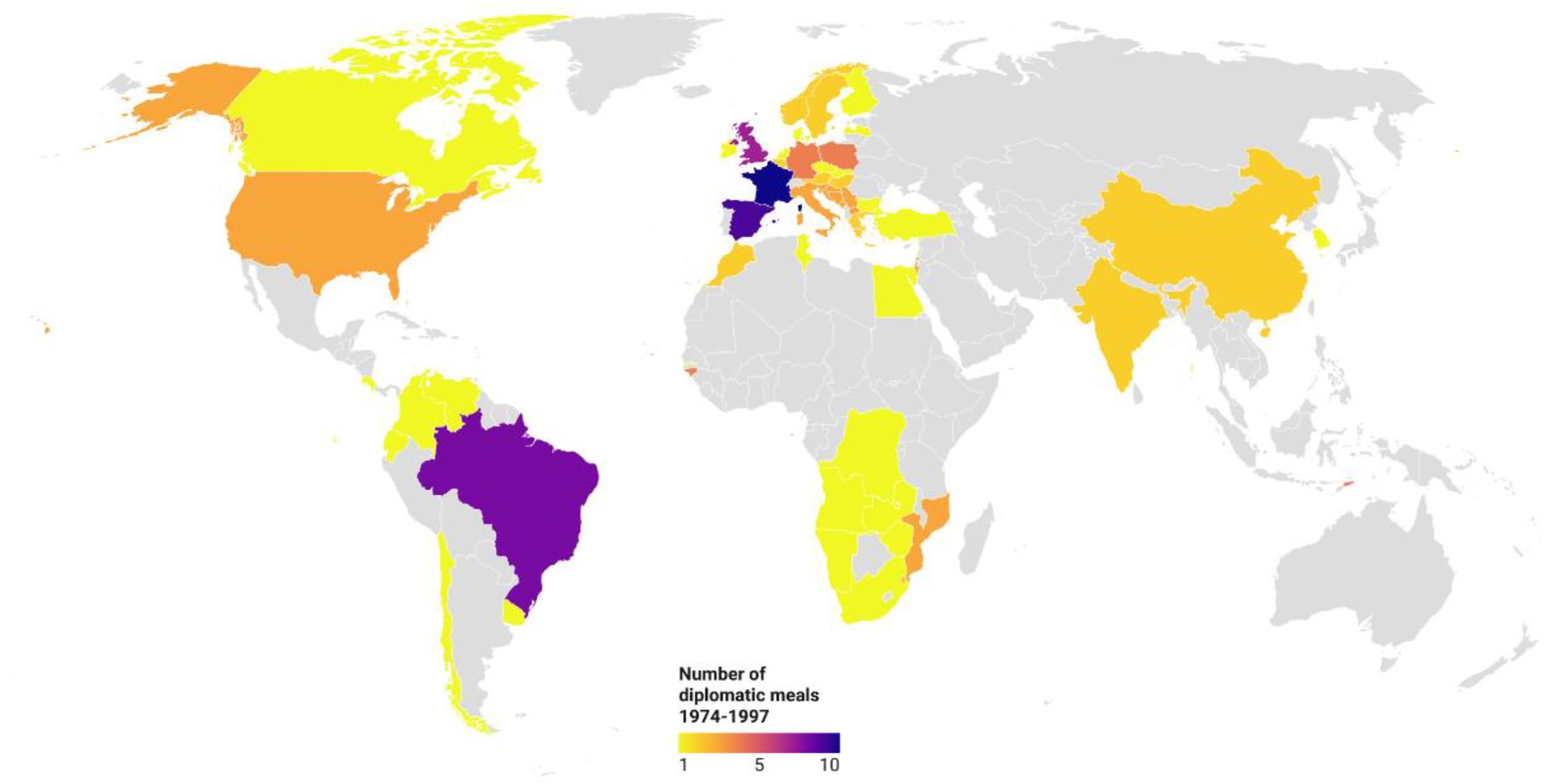

Between 1974 and 1997, spanning from the democratic revolution of April 25 to the eve of Expo’98, Portugal recorded, according to our sample, 155 diplomatic meals that took place for distinguished Heads of State and international organisations as honour guests, as demonstrated in Figure 5. The map’s geographic dispersion highlights an expansion of diplomatic meals as a result of the broadening of diplomatic action in bilateral and multilateral diplomatic relationships (Brandão, 1984).

Figure 5. Geographical distribution of guests of diplomatic meals in Portugal in the period 1974–1997. Source: Authors’ elaboration. Map credits: datawrapper.de.

This expanded coverage highlights a shift in the purposes of Portuguese diplomatic relations, encompassing areas such as politics, culture, military, commerce, trade, investment protection, science, and technical cooperation (Teixeira, 2004). This set of reasons justifies the rapprochement with Europe, Africa, and the Eastern and Western worlds, paving the way for cooperation in development policies (Brandão, 1984). Portugal takes advantage of its geographic position (again, in this new era) while maintaining enduring diplomatic relations with its former colonies, new political actors and long-standing strategic partners. In the Top 10, we find France (10 meals), Spain (9), Brazil (8), the United Kingdom (7), Cabo Verde (5), São Tomé and Príncipe (5), Germany, Guinea-Bissau, Poland, and Timor Leste (all with 4 meals). Regarding the institutional presence of Portugal, the honour guests for diplomatic meals included the EU and its governing bodies (6 meals), NATO (3), UNESCO (2), Sovereign Order of Malta (2), Red Cross (1), Organisation of American States (1), Presidents of the Supreme Courts of Justice and Attorneys General of the States of the European Union (1), Steering Committee/Advisory Group of the Bilderberg Conference (1), Federal Supreme Court of Brazil (1), Academy of the Kingdom of Morocco (1) and OSCE (1). Given this diversity, the authors analysed a few politically and gastronomically significant moments for Portugal.

Politically, this was a highly heterogeneous period, as the revolution ushered in a transitional regime in Portugal during the PREC (Ongoing Revolutionary Process period, 1974–1976), marked by intense social upheaval, addressing many issues related to the transition to a democratic regime (Almeida et al., 2001). The end of colonial wars, recognition of the independence of former colonies, the beginning of diplomatic relationships with new countries and administrative reorganisation of the country, among other factors, paved the way for the independence of former colonies and Portugal’s participation in supranational political projects such as the European Union (F. Silva, 2024). Nevertheless, Portuguese foreign policy in post-1974 maintained the same tone in its international relations that it had before the revolutionary period, establishing a “(.) policy of continuity, informed by its national geography and history (.) harmoniously developed throughout the democratic period” (Santos Silva in Lopes, 2024, p. 88). Also, according to Machete, “(…) the Portuguese geographic position, its territorial and populational dimension, its history and culture have influenced how Portugal inserts itself and acts in the international system” (Machete in Lopes, 2024, p. 88).

Although UN Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim made the first visit to the country in August after the April 1974 revolution, the first Head of State to visit Portugal after the revolution was Leopold Sédar Senghor, President of Senegal, 15 days after the signing of the Alvor Agreement between the Portuguese State and the Angolan guerrilla forces (Brandão, 1984). However, this meal is not included in our sample. The first post-revolutionary diplomatic meal included in our sample was an official lunch hosted by the President of the Republic, Francisco da Costa Gomes, for Edward Gierek, the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers’ Party (ID63). At that time, as illustrated by Portugal’s participation in the Helsinki Conference (finished in 1975), the country was consolidating efforts in different diplomatic settings. On one side, its political rapprochement with the USSR bloc and neighbouring countries like Yugoslavia (F. Silva, 2024) and its Atlantic positioning and proximity to NATO (and its soft and hard power) (J. Fernandes, 2024) as well as the proximity to the United States, were at stake. On the other hand, trade development was crucial to the country’s economic growth. The message delivered in the newspaper following Gierek’s visit was “Let us sell more to Poland”.24 This specific meal, however, featuring lobster, tournedos, and diplomat pudding, offered little gastronomic distinction.

It is also relevant to highlight the characteristics of the banquet served in honour of Marshal Josip Broz Tito of Yugoslavia at the Palácio da Ajuda (ID66, 1977). Known for his anti-colonial stance, this meal holds significance for our analysis for several reasons. Beyond the delicate rapprochement mentioned, it is the first meal of our sample presided over by President Ramalho Eanes. Furthermore, the Portuguese gastronomic identity, as it was understood at the time, was embodied in a menu that featured Sesimbra Sea Bass with Herb Sauce, Sintra Veal with Madeira Wine Sauce, and Nougat Pudding with Alcobaça Peaches. In our analysis, the menu reflects an intention to convey diversity to the President of Yugoslavia, balancing Portuguese traditionalism with national productive capacity while hinting at an aspiration for internationalisation in this new diplomatic phase.

The massive social attention given to gastronomy during this period is a corollary of the accumulated diffuse and multilateral interest in gastronomy in Portugal during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. This systematic enthusiasm, a reflection of a multilateral evolutionary process, appears to have originated politically with the Estado Novo regime. However, it flourished, spurred by Maria de Lourdes Modesto’s television cooking programs (Portuguese and international cuisine) since 1958, broadcasting culinary to people’s houses with the RTP (Portuguese public television) recent emissions. The growing volume and prominence of culinary publications, such as the Banquete Revista Portuguesa de Culinária magazine, witnessed and called on an ongoing journey of “(…) resurgence of the truth Portuguese cuisine [and on a] greater interest in culinary issues (…)”.25 Culinary is then an integral part of the mission of “(…) re-Portuguese Portugal”,26 both internally and externally, as Portuguese cuisine started to be framed as a full-right tourist asset. Additionally, local and national gastronomic events, such as the National Gastronomy Fair (1980), the development of national and regional tourism, and the preparation for product qualification under the EU’s product qualification schemes (late 1980s and early 1990s), would also be of utmost importance for this attention. At this time, gastronomic critics also gained prominence in the national press, with journalists and individualities like Luís de Sttau Monteiro (under his pseudonyms),27 Gentil Marques, Manuel Guimarães, and Melo Lapa, among others. This mobilisation, along with more formal efforts of celebrating Portuguese gastronomy, surged in Lisbon in 1982 with the first meeting at the School of Hospitality and Tourism of Lisbon, paradoxically with the patronage of a representative of the French Culinary Institute (Gomes, 2010),28 eventually leading to the recognition of Portuguese gastronomy in 2000 as an “Intangible Asset of Portuguese Cultural Heritage” and the creation of the “National Portuguese Gastronomy Day” in 2015.29

From a gastropolitical perspective, with the recognition of the independence of former colonies, certain gastronomic aspects also shifted. For instance, the understanding of what constituted Portuguese Regional Cuisine evolved, and even coffee began to be referred to simply as coffee without indicating its origins. All colonial language was, evidently and subsequently, removed from the menus of diplomatic meals.

Also, prior to the signing of the Treaty of Accession to the European Union, our sample includes only one meal (ID65, 1976) served in Sintra during the visit of the President of the Commission of the European Communities, François Ortoli. This visit, aimed at addressing the candidacy that would only take place in 1977 and initiating the acquis communautaire process, serves as the cover to the series of high-level meetings (and diplomatic meals) that Portugal held with European Union bodies to prepare and stabilise Portugal’s entry into the EEC.

From a gastronomic perspective, in 1986, after Portugal entered the EEC on January 1, an official dinner (ID100, 1986) was served in honour of the Europeanist Jacques Delors at the Palácio de Belém. This dinner stood out for its technical nature and the balance between the author’s cuisine and traditional Portuguese cuisine. We understand it, therefore, as a metaphor for the complexity of Portugal’s access to and alignment with the European demands, both preceding and following its accession. During this meal, just days before the start of the celebrations of the Jubilee Year of Tourism in Portugal (1986–1987), in which Portuguese gastronomy took a central role, the menu featured Canja de galinha à camponesa (Country-style chicken broth), Filete de pregado com mousse de tomate e agrião (Turbot fillet with tomato and watercress mousse), Sorvete de vinho verde e limão (Vinho Verde and lemon sorbet), Perna de borrego assada à transmontana com arroz de forno (Roast leg of lamb transmontane-style with oven’s rice) and farófias (soft meringue clouds with English sauce).

Although French cuisine courses continue to dominate diplomatic meals, the atmosphere of diplomatic closeness between Portugal and the countries of the CPLP is also reflected at the table. This closeness is evident in the dishes’ coding, where Portuguese specialities predominate. In terms of main ingredients within this group of countries, codfish recipes stand out, served six times, specifically to Timor-Leste (ID453), Angola (ID437), Guinea-Bissau (ID394), Cabo Verde (ID110), São Tomé and Príncipe (ID268), and Mozambique (ID161). Kid, primarily roasted, was served four times, notably to Mozambique (ID329), Brazil (ID292), Mozambique again (ID246), and Timor Leste (ID357).

Regarding the repeated dishes, it is worth highlighting the Clams in Cataplana, served 3 times to Mozambique (ID161, ID329) and Brazil (ID292), and Cozido à Portuguesa (Portuguese stew) served twice to Angola (ID371) and São Tomé and Príncipe (ID145). In these same meals, a Sopa do Cozido (Cozido soup) was also served, made from the broth of the boiled meats for Cozido à Portuguesa. Arroz de pato (duck rice) is also among the top dishes, served twice in Timor Leste (ID283, ID341). Finally, fish soup was repeated and served to Timor Leste (ID300) and Angola (ID372).

As for sweet moments, the top three include leite creme (custard), typically presented with red fruits, served 10 times to Brazil (ID114, ID209, ID292), Timor Leste (ID263, ID321, ID341), Angola (ID371), Cabo Verde (ID132), and Mozambique (ID328, ID381). Egg-based sweets were served five times in various forms to Brazil (ID35, ID59, ID81), Guinea-Bissau (ID199), and São Tomé and Príncipe (ID291). Encharcada, usually accompanied by fruit, was served five times to Brazil (ID192, ID261), Timor Leste (ID198), Cabo Verde (ID286), and Mozambique (ID282). Papos de anjo (egg cakes with syrup) were also served five times, in small or large versions, with the larger one being nicknamed “papão de anjo.” These were served to Mozambique (ID87, ID329), Brazil (ID311), Cabo Verde (ID157), and São Tomé and Príncipe (ID252).

From 1974 until the eve of the inauguration of Expo’98, Portugal witnessed three Presidents of the Republic and six Prime Ministers, all of whom came from the socialist or social-democratic parties. The mobilisation and political participation of citizens grew during this period, not only in elections but also in associations, popular movements, and political movements. Nevertheless, diplomatic meals always enjoyed the protection granted by a certain secrecy surrounding diplomatic activities, even during heightened political scrutiny. The only references gathered in the consulted Archives that contradict this silence occur during this period, 13 days before the official Luncheon offered by the University of Évora to Queen Elizabeth II on March 28, 1985 (ID97):

“From Portuguese mothers who have children studying in terrible conditions of health, education, and food, they will have to account for the money spent on the Queen’s reception. If not, they [the mothers] will not hesitate to blow the university building into the air”. Source: The Historical Archive of the Presidency of the Republic, Ref. PT/PR/AHPR/CC/CC0206/0799.

Finally, this period is marked by the presence of various international organisations in Lisbon, with special emphasis on UNESCO’s involvement in diplomatic meals. This is noteworthy for two reasons. Firstly, Portugal’s intermittent membership in the organisation. The country joined in 1965, but due to disputes arising from colonial issues, Portugal withdrew in 1972. The request to rejoin was submitted in September, just a few months after the April 1974 revolution. Secondly, due to the importance that cultural matters have started to hold in diplomacy. Two diplomatic meals were recorded in the pre-Expo’98 period (ID182 in 1994 and ID197 in 1996). The official lunch and dinner, respectively, featured dishes such as lobster salad, veal tenderloin with vegetables, langoustines in a Portuguese-style sauce, and grilled grouper with vegetables. The latter meal is one of the rare occasions when white Vinho Verde was served to accompany seafood and fish.

ii. Expo’98 (1998)

The International Exhibitions have historically served as excellent showcases for their host countries’ industrial, economic, cultural, and tourist promotion. Expo’98, one such example, marked the culmination of Portugal’s diplomatic efforts, where gastronomy played a fundamental role in fostering connections among people and dignitaries. Beyond the extensive offering of Portuguese and international dining options for visitors, the diplomatic meals were primarily organised by ENATUR, a state-owned company responsible for managing the Pousadas de Portugal (Portuguese Inns), created by the SNI in 1942. Recognising the role of the Pousadas in promoting Portuguese gastronomy, this mission was once again entrusted to them during this event.

The restaurant they managed, Viagem dos Sabores, located in the Portugal Pavilion, was designated for official meals. It served as a space for “showcasing national gastronomy,” offering “an excellent opportunity to enjoy the most representative delicacies of Portuguese cuisine”.30 The various dining rooms, including those for banquets, lunches, and official dinners, had a maximum capacity of 300 seated guests and 600 for standing receptions.

Recalling the central theme of Expo’98–The Oceans–it is notable that, of the 22 recorded meals from this period (served not only at Expo’98), 11 featured fish as the main course (primarily grouper, wreckfish, and seabass). The remaining dishes were meat-based, ranging from Curia-style pheasant, Conventual partridge and Singeverga-style duck to various goat and lamb dishes, underscoring the role of territory and religious aspects in the dishes’ communication.

The inauguration banquet was held on May 22, 1998, at the Vasco da Gama Tower Restaurant, also known as Torre T in Lisbon (ID228). It was attended by five Presidents of the Republic (Brazil, Cabo Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, and São Tomé and Príncipe), Prime Ministers, numerous foreign affairs ministers, and the President of the European Commission. This banquet, heavily influenced by State Protocol, included dishes considered traditional Portuguese, such as Terrine of goose livers with Moscatel jelly, grapes, and toasted bread, and Wreckfish loin with clams. The Portuguese classic Pudim Abade de Priscos, a pudding made with eggs, sugar, and cured ham, was served for dessert. However, these choices suggest a limited emphasis on Portuguese cuisine as a defining factor in coeval diplomatic meals.

iii. A new diplomatic Portugal 1998–2023: more convergence than tensions?

The period marking the beginning of this new era, which brings significant and positive developments to Portugal in the foreign policy, diplomatic and gastronomic domains, inherits from Expo’98 the legacy of social mobilisation for sustainability causes while paving the way for Portuguese diplomatic stability.

Thus, while China’s presence in Portugal became prominent on the eve of the sovereignty transfer of Portugal’s last colony, Macau, in 1999, Portuguese gastronomy entered a prosperous phase with its elevation to the status of “intangible cultural heritage of Portugal” in 2000. For the first time, in 2001, a National Gastronomy Commission was established, focusing its efforts on the recognition and heritage preservation of Portuguese cuisine in all its facets.

Regarding China, despite its presence being noted seven times in our sample (covering the period 1984–2018), also expressing the Portuguese foreign policy focus on the economic diplomacy already discussed above, the most recent of which was with President Xi Jinping, diplomatic participation in official meals alternates between the Government and the Presidency of the Republic. President Jiang Zemin was the last to receive a banquet in his honour at the Palácio Nacional da Ajuda, approximately 2 months before the sovereignty transfer ceremony of that territory (ID254). The menu included Gratinated spinach crêpes, Lobster in champagne sauce, Leg of lamb with rosemary, and Chocolate marbled dessert.

In the remaining meals, certain moments stand out: Palm hearts cream (ID94), Queijo da Serra (ID188), Partridge with cherries and vegetables (ID370), Tomato cream soup with egg threads (ID386), Sopa de míscaros com foie gras [a Portuguese mushroom soup with foie gras (ID387)], and Coriander soup with crispy suckling pig (ID438).

Among the 218 diplomatic meals recorded during this period, two stand out for their evident gastropolitical significance. First, the official dinner in honour of the Spanish Royals, hosted at the Palácio Nacional da Ajuda in 2016 and served at the Paço dos Duques de Bragança in Guimarães (ID416). Second, the official lunch served to Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, hosted by Prime Minister António Costa at the Palácio das Necessidades in 2017 (ID421)—one of the 16 meals hosted by a Prime Minister or an equivalent leader.

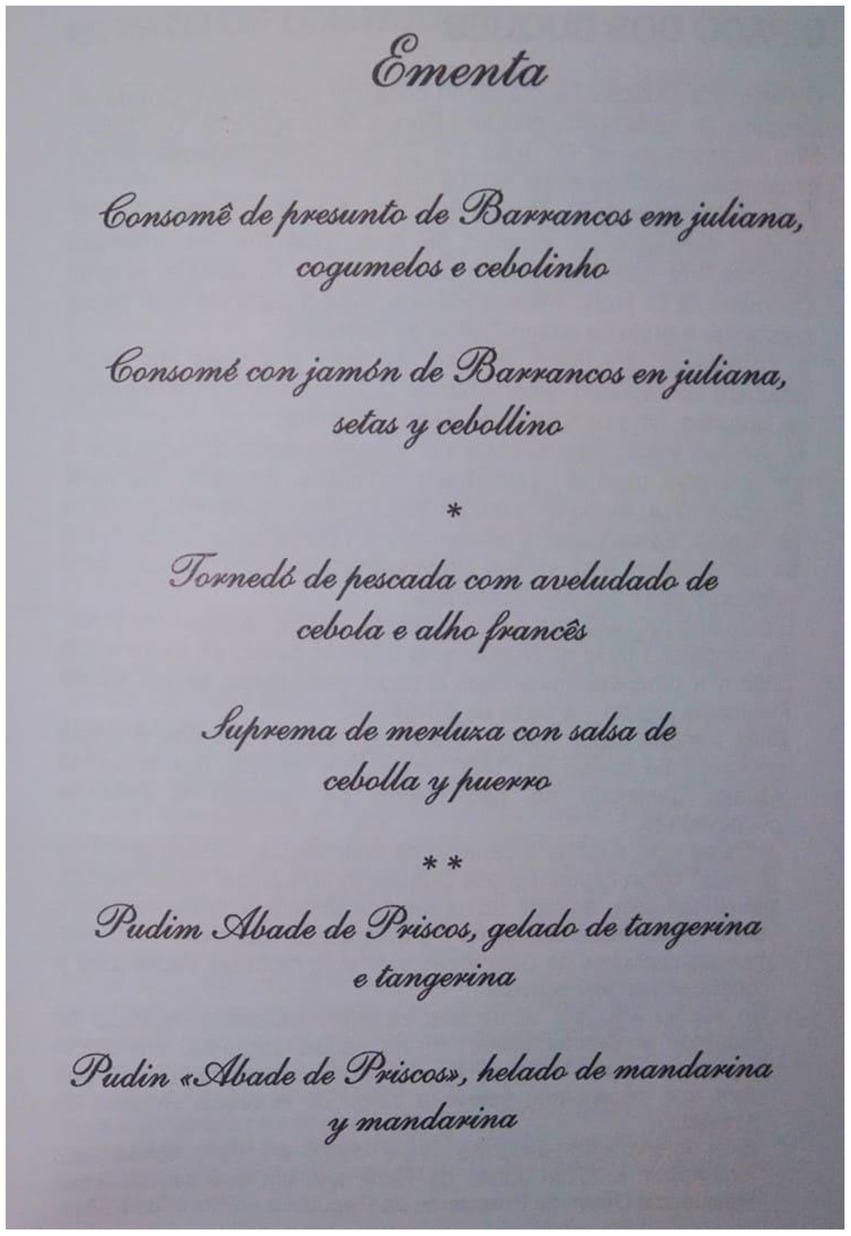

In the first case, although the exact context of the diplomatic meal definition is unknown, it is worth emphasising the cultural and gastronomic identity challenge posed to King Felipe VI of Spain (ID416) by including the first savoury course, Consommé de presunto de Barrancos (consommé of cured ham from Barrancos). This analysis, viewed through the lens of gastropolitical semiotics and gastronomic cultures, is significant. On one hand, Spain is firmly established as “el país del jamón” (the country of cured ham). Nevertheless, it is intriguing that its neighbouring host country, with a deeply rooted tradition of cured pork products, would serve a hybrid dish: a French-based soup (consommé) using a Portuguese product with a Protected Designation of Origin (although its PDO is not communicated, nor is that of any other product qualified under the European schemes) and employing a classical French cutting technique, a julienne.

This moment, illustrated in Figure 6, exemplifies the integrated power of cultural, agri-food, territorial, tourism, and gastronomic communication within diplomatic channels.

Figure 6. Official dinner menu served to Felipe VI of Spain by the President of the Republic, Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa, in November 2016 at Paço dos Duques de Bragança (Guimarães). Source: The Diplomatic Archive of the Portuguese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, No archival reference.

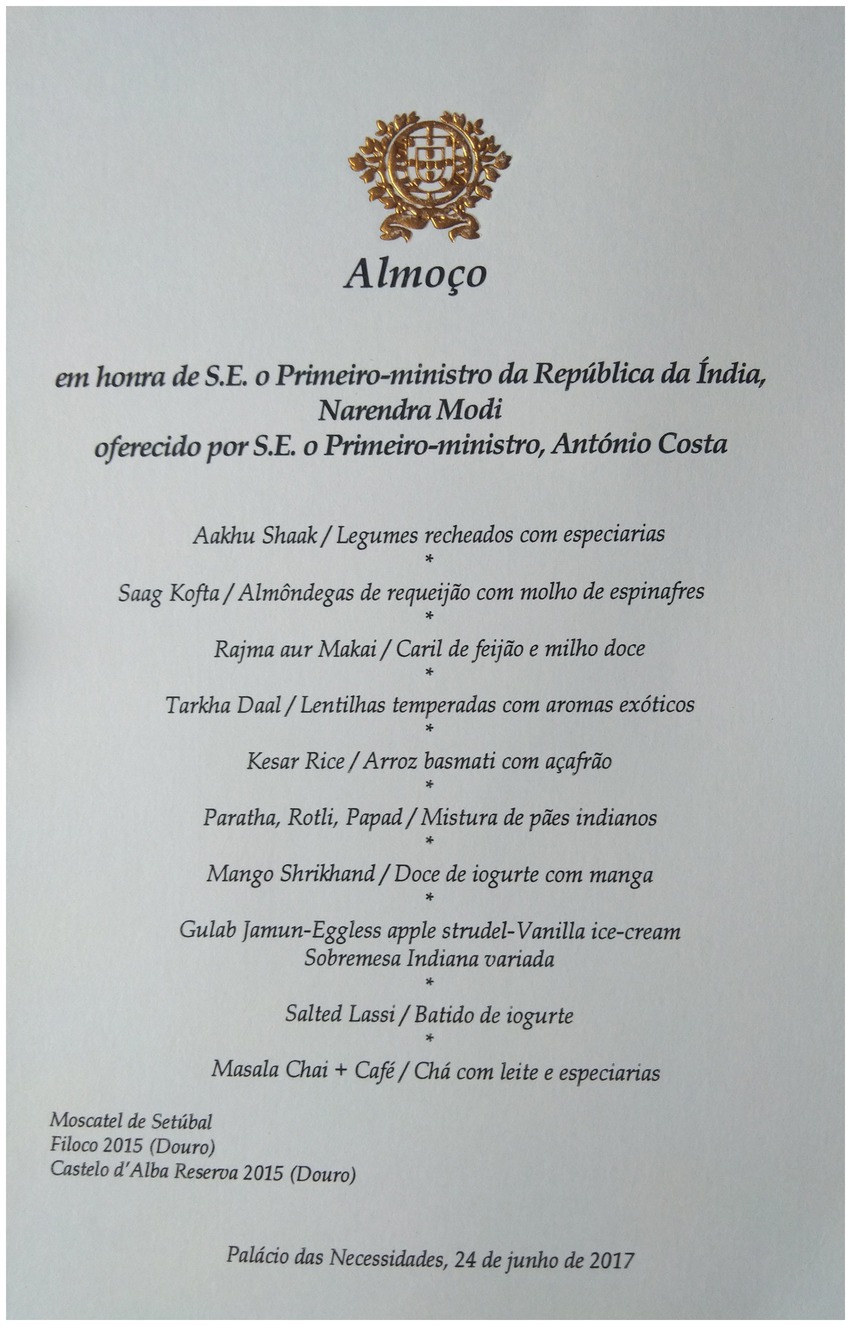

On the other hand, the lunch served by António Costa deserves special attention in our analysis due to the atmosphere of familiarity it seeks to establish. Diplomatic meals often use psychological strategies to create comfort and a sense of community for the hosts (Cabral et al., 2024a, 2024b). Moreover, if there is an example of this, it is the meal served to Narendra Modi, who visited Portugal with economic and scientific diplomatic objectives. António Costa, Prime Minister of Portugal from 2015 to 2023, of Goan descent on his father’s side, offered Modi a vegetarian meal with Indian-based dishes, as protocol dictates.31 The meal composition is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Official lunch menu served to the Indian Prime Minister by the Portuguese Prime Minister António Costa on June 24, 2017, at the Palácio das Necessidades. Source: The Diplomatic Archive of the Portuguese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, No archival reference.

Finally, a reference for a research silence. The Portuguese pastel de nata (custard egg tart) plays a prominent role in the international representation of Portuguese gastronomy. In the context of the included diplomatic meals, it is mainly denoted by its absence. In 457 diplomatic meals analysed, it appears only once in its pastry form, incorporated into a dessert with caramelised fruit. Its prominence is also due to the fact that it was served by President Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa to his Serbian counterpart during a dinner in 2017 at the Palácio Nacional da Ajuda, prepared by Chef José Avillez (ID418). This is the only occasion in our sample where the chef is named in the menu.

5 Conclusion

The analysis of 457 diplomatic meals reveals that they reflect the main characteristics of state visits. Based on the collected and analysed data, it can be affirmed that these meals play a significant role in the execution and continuity of Portuguese foreign policy. As stated by Freire and Vinha (2015) the mobilisation of internal aspects related to Portugal’s territorial gastronomy and gastronomic identity in the substantiation of these visits and meals is confirmed, albeit in a limited manner. The predominance of French cuisine contrasts with the introduction of rare Portuguese products over time at the diplomatic table. Political and diplomatic contact creates distinct contexts and opportunities in which food and the table, as spaces of continued power exercise, assume a fundamental role, including in the semiotic relationship between the consumed foods and the power possessed by their consuming agents. This confirmation emerges through menus, visit configurations, and Chef selection (as seen in the dinner served to Serbia [ID418]), among other aspects.

Five essential types of diplomatic meals were identified, manifesting throughout Portugal’s different political and social periods, whether in dictatorial or democratic regimes, even though their purposes may overlap.

The first group are associated with tactical meals. Those meals are associated with an embryonic moment in transport development and the necessity of stopping vessels or other means of transportation in Portugal, leading Heads of State to temporarily remain in Lisbon (e.g., Monaco ID1, United Kingdom ID2, Poland ID7). More recently, there have been tactical-political meals related to the cession of territories of former colonies, such as the banquet offered to Chinese President Jiang Zemin (ID254) during the official transfer of Macau to Chinese rule.

The second group includes the geopolitical meals aimed at renewing and confirming alliances. This group includes the visits from the United Kingdom (ID8, ID31, ID28, ID61), the USA (ID3, ID44, ID57, ID78, ID109, …), NATO (ID23, ID51, ID98, ID112, …), and Spain (ID4, ID16, ID52). These also include meals demonstrating support (such as Ethiopia ID39) or censorship of Portuguese imperialist geopolitical choices (such as Indonesia, ID36, ID41, ID42, ID43, or South Africa, ID12, ID13), particularly during the colonial period. Additionally, courtesy and reciprocity visits from the Vatican (ID17, ID19, ID21, ID37, ID186, …) and meetings associated with the propaganda of totalitarian regimes, such as the Iberian brotherhood, featuring General Muñoz-Grandes or Generalissimo Franco himself (ID4, ID16, ID34, ID52), or the visit of Benito Mussolini’s Air Minister (ID9), fall into this category. Along with cultural proximity meals, this category justifies most diplomatic meals that persist today in these and many other countries.

The third group includes the cultural proximity’s meals. These fit within Portugal’s foreign policy strategy to strengthen cultural ties with the PALOP and CPLP countries, from which, alone, at least 85 diplomatic meals have been recorded (approximately 19% of the total sample).

The fourth group includes the economic diplomacy meals. Those meals are primarily intended to foster commercial and financial relations, such as those held with EFTA (ID45), Pakistan (ID33), Thailand (ID48, ID45), Poland (ID63), Nigeria (ID451), or the European Central Bank (ID446).

The fifth and last group includes the scientific, cultural, and development cooperation diplomacy meals. Some examples of this are the visits of the former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan (ID342), representing a cross-section of interests in these areas, or India (ID421).

Despite adhering to principles of diplomatic prudence, meal curatorship is essentially carried out by street-level bureaucrats, as defined by Lipsky. Some choices demonstrate the transmission of a diplomatic, cultural, and culinary identity, as pointed out by Mahon. However, the aesthetic component and gastronomic creativity lie in the service provider’s scope, reflecting the selection of products and techniques aligned with a vision of a “high” diplomatic cuisine, in the sense of Jack Goody, rather than in an expression of Portuguese culinary identity. The exception confirms these configurations: in the menus served to CPLP countries, where cultural relations prevail in diplomatic meals, different products are used, more closely tied to a national sense of Portuguese gastronomy.