- 1Department of Politics, Languages and International Studies, University of Bath, Bath, United Kingdom

- 2School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Northumbria University, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom

Comprehensive trade agreements between regional groupings in Latin America and the EU have been in place since the early 2010s. These were some of the first EU agreements to incorporate dedicated chapters for trade and sustainable development that have garnered criticism due to their limited enforceability and failing to transform social and environmental circumstances on the ground. Trade agreements are living agreements; the texts are not end points but starting points for implementation processes. After over a decade of implementation of agreements, scholars are turning their attention to implementation processes of trade and sustainability chapters and uncovering some slow gradual changes. This contribution leverages publicly available documents relating to implementation committees and elite interviews to uncover the practical reality of interactions between Latin American regional groups (Central America and states in the Andean Community) and the EU relating to trade and sustainability in the context of their trade agreements and against the backdrop of global polycrises. The analysis pays special attention to themes discussed, to parties raising issues and the nature of the discussions, whether this includes coercive demands for action, or adversarial exchanges. In so doing, it uncovers hierarchies of themes and action prioritisation within relationships characterised by significant economic power asymmetries. Unpacking the functioning of the trade and sustainable development (TSD) implementation committees contributes to the wider literature on EU-Latin American relations and a growing literature on TSD in EU trade agreements. The analysis reveals that discussions and cooperation on critical sustainability matters, even on new priorities not present when the FTAs were negotiated, help to raise the level of environmental ambitions of the parties. At the same, financial constraints on both sides, and EU unilateral measures to address the climate and environmental crisis result in different priorities for tackling these issues and tensions in the relationship.

1 Introduction

The European Union (EU) is a staunch supporter of global initiatives addressing a key aspect of the so-called polycrisis moment: climate change. It has positioned itself as a self-proclaimed leader in this area, garnering both support (Borchardt et al., 2025) and criticism (Almeida et al., 2023) for this. It has enacted a series of internal policies to hasten decarbonisation, e.g., Emissions Trading System (ETS), decades of environmental regulations, and the 2019 European Green Deal flagship programme (Wurzel and Connelly, 2011; Parker and Karlsson, 2017; Oberthür and Dupont, 2021).

Given the global nature of the climate change challenge, the Green Deal exemplifies EU policies with an extraterritorial effect (Eritja and Fernández-Pons, 2024). Measures like the controversial Carbon Border Adjustment Measure (CBAM) or the EU Deforestation -free Products Regulation (EUDR), which would ban certain agricultural and forestry commodities and derivatives—(European Commission, 2025a) produced in deforested areas from entering the EU market, are specifically designed to have an impact on sourcing in supply chains and production elsewhere in the world (Gilbert, 2024; Magacho et al., 2024).

Latin American countries, for their part, have been active in international climate and environment regimes, and have enacted extensive legal reforms and domestic green policies. For instance, Brazil established the Amazon Fund in 2008 to combat deforestation, and has emerged as a regional leader on the Amazon (Tigre, 2016) taking steps to combat deforestation and to establish environmental institutions and policies over the last decades (Eduardo and Franchini, 2017). However, initiatives have been subject to periods of advances and retrenchment (Hochstetler, 2021), including reversals during Bolsonaro’s time in office (Toni and Feitosa Chaves, 2022). Mexico has adopted ambitious legislation in its Climate Act, although structural deficiencies have limited its implementation (Solorio, 2021). Across the continent green policies have enjoyed different degrees of success (Zepeda-Gil and Natarajan, 2020), and despite some valuable success stories, insufficient finance has stymied ambitions (Cárdenas et al., 2024).

In terms of values, the region has been a key innovator in environmental rights. Following the 2012 Rio + 20 Conference, governments negotiated the first legally-binding international agreement specifically to protect environmental rights in Latin America and the Caribbean—the Escazú Agreement (2021; GNHRE, 2025). Ecuador was one of the first countries to include mentions to Nature’s rights (Mother Earth’s rights) in its 2008 Constitution (ELFLAW, 2023),1 and the region is leading the way in developing climate litigation (Tigre et al., 2023; Winter de Carvalho et al., 2024). Others, like Costa Rica, a founding member of the Agreement on Climate Change, Trade and Sustainability (ACCTS), are spearheading novel approaches to make international trade more sustainable and to use a wider array of policies to address climate change. Latin America and the EU share a keen interest in the climate and environment aspect of the polycrisis and are active in developing different to ways to address it.

Against this backdrop, in the context of an ever-developing international climate and environmental regime, EU-Latin America environmental and climate cooperation has gradually increased as is evident in a growing number of EU projects in Latin American countries (Dominguez, 2015). Over half of EU projects in Latin America proposed under the Global Gateway programme2 that mobilises public and private investment to address global challenges like climate and energy and digital transitions, relate to Climate and Energy (see Appendix 1).

This developing cooperation on climate and environment in EU-LAC relations, has attracted scholarly attention, focused on how combatting climate change and environmental degradation has been addressed through the interregional relationship, by (i)tracking the evolution of the theme in EU-Latin American governance and projects (Dominguez, 2015; Ribeiro Hoffmann et al., 2024), and (ii) within discussions of EU-LAC summitry (Castiglioni, 2024). To our knowledge, the articulation of climate and environment in EU-Latin American relations by means of the free trade agreements (FTAs) that connect the regions has been neglected. FTAs represent the culmination of decades of economic and political cooperation, and, are concrete and valued examples of the interregional relationship. These are important legal instruments within broader interregional relations that also serve to address the inextricable link between trade and climate and the environment and warrant further scrutiny.

This article turns its attention to the EU’s Multi-party Agreement with Peru/Colombia/Ecuador (MPA), and the FTA part of the Association Agreement with Central America (EU-CA FTA). These agreements included chapters on trade and sustainable development (TSD), aimed at addressing the trade-environment (and labour) intersection, and at improving environmental legislation. We seek to understand how interregional climate and environment cooperation is articulated in practice, through the implementation of the TSD chapters, as these are key components of the overarching interregional approach to global climate, and environmental challenges. Special attention is paid to the nature of interregional relations as articulated in the context of the FTAs, i.e., whose concerns take precedence, how topics for cooperation are selected, and what that cooperation entails, to discern whether the relationship leads to more consensual and compatible approaches towards contributing to resolving the climate and environmental crisis. In so doing, the article contributes novel insights to both the literature on EU-Latin American relations, and the incipient literature on environmental aspects of EU TSD chapters and on the implementation phase of these chapters.

The rest of the article is structured as follows: Section 2 conceptualises interregionalism. Section 3 provides an overview of EU-Latin American interregional relations and locates this research within the literature on interregional relations with Central America and Andean states. Section 4 details the content and operation of the TSD chapters. Section 5 presents the methods and data sources employed. Section 6 presents the findings and how climate and environment cooperation is articulated through the implementation of the TSD chapters. Section 7 concludes that TSD chapters are facilitating important discussions on climate and environment between the parties, but whilst there is agreement on the need to act on climate and environment, specific thematic priorities within this broad category and preferred approaches differ.

2 Conceptualisation of interregionalism

Interregionalism first appeared in the literature as the EU started to develop external relations with other groupings of states, as captured in early discussions of the phenomenon in Edward and Regelsberger (1990) collection Europe’s Global Links: European Community and Interregional Cooperation.

Initial research was associated with the articulation of EU external actorness and evolution of regionalism (Söderbaum and Van Langenhove, 2006). Early work considered regional groupings and subsequent interregional relations between these as potential modes for global governance (Doidge, 2007). The literature emerged from a eurocentric perspective (Rüland, 2014). However, the concepts were refined in comparative literature considering relations between different regional organisations (Hänggi et al., 2006), and literature exploring the actorness of other organisations (Mattheis and Wunderlich, 2017), and influence of non-state actors in interregionalism (Litsegård and Mattheis, 2023). As the literature developed, the focus also shifted from studying the potential of interregionalism, to exploring obstacles to achieving global governance through interregionalism (Gardini and Malamud, 2018).

Interregionalism does not represent a unified concept. Instead, it has been used to define different types of relationships, including (i)pure interregionalism, a model in which two or more regional organisations interact; (ii) transregionalism, which brings together members of two or more regional organisations; (iii) and hybrid interregionalism (Hänggi, 2006), that develops between a single group with a member state of another group (Aggarwal and Fogarty, 2004).

Interregional relations are considered to fulfil several functions in international relations: balancing (developing regional groups as a way of balancing against major powers); institution-building; rationalising (engagement among smaller number of states than in multilateral fora); agenda-setting (at times when major powers dominate international politics); and collective identity-building (Rüland, 2010). Within a European context, the collective identity-building function has been considered an important aspect of the EU’s promotion of interregional relations. Interregionalism served a legitimating function, advancing a ‘need to forge a common European identity among the people of its constituent nations and by a belief in the utility of regions as unit for organising the global economy’ (Aggarwal and Fogarty, 2004, p. 14). Engaging in interregional relations was considered to help normalise the value of regional integration groupings and the legitimacy of these as entities in the international system (Söderbaum and Van Langenhove, 2006).

Within this context, the EU has actively promoted regionalism through support for other regional integration projects (Pietrangeli, 2016), including capacity building and financial assistance (Jimenez Soto et al., 2025) in attempts to normalise and legitimate regional organisations as key actors in international governance.

Relations with Latin America, as summarised in section 3, have epitomised these attempts at legitimating and raising the international profile of regional integration projects, and of the EU as an entity and international actor in its own right. Interregional relations have revolved around different types of initiatives to promote democracy, improved human rights, economic cooperation and development, creating broad multi-layered relations that in the 1990s and early 2000s stood in sharp contrast to the USA’s model of market and economic-driven relations with other regions (Börzel and Risse, 2009). This distinct focus on values and the performance of ‘normative power’ (Manners, 2002), in a part of the world of lower strategic salience to the EU, enabled it to further legitimate its foreign policy (Smith, 1995) and, itself, as an organisation representing a ‘better’ form of international actor (Börzel and Risse, 2009).

Creating a true interregional partnership with Latin America, could establish the EU’s credentials as a global civilian power, and also support Latin American hopes at the turn of the millennium for a multilateral order built on the principles of diplomacy, economic cooperation and non-intervention as an alternative to USA unilateralism (Freres, 2000, p. 79). Political, development and economic cooperation activities, and improved bases for economic and trade relations through FTAs, have, thus, been made contingent on further regional integration (see section 3). Whilst this conditionality has not always delivered desired outcomes in full (García, 2015), as evidenced by the complicated and fragmented evolution of regionalism in Latin America (Malamud, 2010), this emphasis supports a discourse proposing regional integration as a valuable aspiration in and of itself, and the self-legitimation of the EU as an integration organisation.

In practice, however, domestic political changes, economic and geopolitical upheavals, entangled with the so-called polycrisis at the heart of this special issue, have marred the practical potential of the interregional relationship (see inter alia Sanahuja Perales and Bonilla, 2022; Martins, 2023; Freres et al., 2007), not least in terms of advancing alternative global governance. The confluence of global changes, the polycrisis, including European economic constraints since the eurocrisis, its inability to adequately respond to migration and other challenges, has weakened the credibility of the EU as an international actor, and increased criticism of the EU as integration project (Becker et al., 2021). In Latin America, disappointment with the EU’s initial inability and reluctance to deliver covid-19 vaccines to the region, for instance, affected the EU’s credibility as a partner for cooperation and solidarity in the interregional relation (Barrera and Bonilla, 2025).

Against this backdrop, practical examples of successful interregional relations and cooperation, especially if directed at confronting critical challenges, gain importance as a way to not only justify the relationship, but as explained above to legitimate the EU as a project and international actor. At the present juncture, when international organisations, be these multilateral organisations like the WTO, looser structures like the climate regime, or regional organisations like the EU, are increasingly questioned and contested, legitimating these becomes increasingly important (Lenz and Söderbaum, 2023).

Organisations deploy various strategies to legitimate their existence and practices: a discursive (a rhetorical claim to legitimacy), institutional (creating or modifying institutional arrangements) and behavioural strategies (performative practices, review exercises, performance reviews; Lenz and Söderbaum, 2023). Within the EU-Latin America interregional relationship, FTAs represent an important example of institutionalised operationalisation of the relationship with subsets of states. Unlike most other facets of the interregional relationship, FTAs are legally-binding frameworks, and are desired outcomes of the relationship, with Latin American states often having been demandeurs of FTAs (García, 2015; Gomez-Arana, 2017). Their success is, therefore, important for demonstrating value-added from the interregional relationship and enhancing the EU’s credibility and legitimacy as an international actor. FTAs, as a mode of governance, in an of themselves, include TSD chapters, both as a way to address climate and environmental concerns, and mechanism to enhance the legitimacy of the FTAs.3 In this article, we consider FTAs, and the TSD chapters within them, as a form of institutionalised operationalisation of the interregional relationship between the EU and certain states in Latin American regional groupings. These legitimate and enshrine certain beliefs about how to run economies (an open approach to trade), and through the TSD chapters also about how to balance environmental (and labour) policies with trade openness. We interpret the practical implementation of TSD chapters as an example of an institutionalised innovation that extends the interregional relationship, and supports interregional ambitions to confront the climate and environmental crisis. TSD chapters are ‘institutions’ in which the absence of legally-binding mechanisms to ensure implementation, results in a reliance on what Lenz and Söderbaum (2023) have termed behavioural legitimation strategies in the form of performance reviews rankings and discussions, to not only demonstrate the value of TSD chapters, but to legitimate the FTA, in its entirety, as a framework for a mutually beneficial interregional relationship that transcends purely economic relations among businesses on both sides of the Atlantic. With its focus on how the interregional relationship is manifested in the practical implementation of TSD chapters in interregional FTAs, we contribute novel empirical insights into behaviours that emerge in this relationship and how they relate to shared values and interest in tackling global climate and environmental challenges.

3 EU-Latin America interregional relationship

EU relations with Latin America have gone through different stages since they started informally around 45 years ago. They are the outcome of a complex web of interregional, regional and bilateral relationships with different degrees of success and institutionalisation, including political dialogues, development aid, strategic partnerships, framework cooperation, association agreements and legally-binding free trade agreements (FTAs) (Hardacre and Smith, 2009; Selleslaghs 2018). The variety of actors (governments, regional organisations, civil society, NGOs) and layers of relations with the whole region, regional groupings and individual states display mechanisms of transregionalism, pure, and hybrid regionalism described by Hänggi (2006), and have been considered a template for interregionalism despite their varied outcomes (Ayuso and Gardini, 2017). Initial EU formal relations with the region revolved around political and economic support for Central American states’ peace processes through the San José Dialogue at these states’ behest (Smith, 1995). Political dialogues, political cooperation (including support for democratisation) and economic cooperation, often in the form of development aid became cornerstones of the relationship. The EU, and its member states, became the largest development cooperation actor in the region (del Arenal, 2009). Growing private investment in the region and increased trade flows, supported by economic cooperation and the inclusion of many countries in the region into the EU’s Generalised System of Preferences (GSP) facilitating access to the EU market for products from developing countries, strengthened the interregional economic relationship.

However, the relationship has been fraught with disagreements and inconsistencies. Design shortcomings in democracy promotion initiatives limited their success (Youngs, 2002, p. 111), and conditioning cooperation to advances in democratisation and human rights was controversial for some governments (Youngs, 2002). In economic cooperation, whilst GSP is meant to support economic development by fostering exports, exceptions in the types of products covered, such as sugar, have prevented developing states in Latin America from expanding exports in products in which they are very competitive. In the case of Central America, highly competitive bananas did not benefit from improved market access, until the ‘banana wars’ dispute challenging EU preferences for bananas from former UK and French colonies was resolved at the WTO (Valladão, 2016).

A succession of dialogues and cooperation programmes displaying the various types of interregionalism (pure, hybrid, transregionalism) have set the backdrop against which more structured economic relations have been forged with the negotiation of free trade agreements (FTAs) with Mexico and Chile in the early 2000s (both of which have been recently modernised), and with Andean and Central American states a decade later. Challenging two decades-long negotiations between the EU and Mercosur for an Association Agreement including a FTA concluded in an agreement that is yet to be put to a ratification vote in the EU, 5 years after the initial conclusion of negotiations (see inter alia Gomez-Arana, 2017; Sanahuja and Rodríguez, 2022). This perfectly encapsulates the constant ebbs and flows in EU-Latin American relations, where periods of initiatives are marred by lack of momentum and de-prioritisation by the EU of the region that have characterised EU-Latin American relations (del Arenal, 2009; Roy, 2013; Gardini and Ayuso, 2015).

3.1 EU-Central America interregionalism

Central American integration has a long and complicated history predating formal interaction with the European Community/Union. Initial plans to create a Central American Common Market in 1960 failed to deliver such a market in part due to import substitution development practices hampering market-creation.4 Integration was relaunched in the 1990s as economic reforms took root, and was characterised by development of new integration frameworks, the System for Central American Integration (SICA in Spanish).5

The institutionalisation of region-to-region relations began through European political cooperation in security and peace processes in Central America. When the Sandinista revolution in Nicaragua took place in 1979, and Central America edged closer to a political and economic crisis, the EU tried to contain this supporting a ‘Peace-Democracy-Development’ approach (Bulmer-Thomas and Rueda-Junquera, 1996, p. 323). Within this context of reinforcing political stability, interregional relations began in 1979 with an informal dialogue, followed by a meeting between the Contadora Group and the Troika and the institutionalization of the political dialogue in 1984 through the mechanism of San Jose (Munguía, 1999). The Cooperation Agreement of 1985 was established within this context (Bulmer-Thomas and Rueda-Junquera, 1996; Munguía, 1999). Central America requested a dialogue on political and economic matters within the San Jose Dialogue forum, in the hope that economic cooperation would improve their asymmetrical economic relations (Bulmer-Thomas and Rueda-Junquera, 1996, p. 324). The relationship, thus, took on a political and economic dimension. Politically, support for peace and democratisation was reinforced with financial support as this lay at the heart of EU relations with the region (Youngs, 2002). European ideological support for regional integration was evident in other political initiatives aimed at fostering regional integration in Central America in more concrete ways; the European Parliament supported the creation of Parlacen, the Central American Parliament created in 1991 and supported the establishment of SICA Central American Integration System in 1993 (Munguía, 1999).

Economically, by 1991 the Generalised System of Preferences (GSP) scheme was incorporated in the Cooperation Agreement (Bulmer-Thomas and Rueda-Junquera, 1996). However, the exclusion of bananas, and sugar (due to European market protectionism for this product) from market preferences stymied some potential economic gains for Central American states (Rivera and Rojas-Romagosa, 2007). In fact, the EU Association Agreement with Central America agreed in 2010 during the Spanish presidency, was only possible after an agreement was reached resolving the long-term banana trade problems (Gomez Arana, 2015).

The decision to upgrade the relationship and commence negotiations for a comprehensive Association Agreement including a FTA to further institutionalise the interregional relationship was an important one. The EU made negotiations contingent on increased regional integration. At this stage, EU’s prioritisation of trade negotiations at the WTO Doha Round had been established. However, given the EU’s promotion of regionalism, it made an exception for regional groups (Aggarwal and Fogarty, 2004). The EU had delayed the start of negotiations arguing more integration was required, however, once countries in the region had entered into FTAs with the US, and Doha Round negotiations all but collapsed in 2005, the EU acceded to negotiate (García, 2015; BKP Economic Advisors 2022a, p. 15). The negotiations successfully ended 5 years later. The final Association Agreement was negotiated between the European Union and some of the SICA members: Costa Rica, El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, Nicaragua and Panama.6

Unlike the FTA with the US, given the regional focus, this agreement included Panama (Gomez Arana, 2015). When the agreement entered into force in 2013, it became the first EU FTA with another group of states.

The EU has supported political stability, economic growth, and regional integration in Central America, but benefits for Central America from the relationship can at times be limited due to the EU’s policies (e.g., agricultural policy and sugar imports). Moreover, although the FTA has resulted in increased banana exports to the EU and slight growth in Central American exports, change of land-use for agriculture combined with weaknesses in the agricultural sector may have had some negative impacts on the environment, such as poor water management, indirect deforestation, forest degradation, and pollution (related to agrochemical use) (Commission Services 2022, 2; BKP Economic Advisors, 2022a, p. 6). As subsequent sections show, the tensions between EU policies and partnership with Latin American states remain when it comes to the climate and green agenda and its articulation in the implementation of FTAs.

3.2 EU-Andean community interregionalism

As with Central America, the European Union was supportive of regional integration in the Andean region, which started in the 1960s. Political and cooperation relations were strengthened with the 1998 Cooperation Agreement which laid the ground for political dialogues, development cooperation and an evolving relationship leading to the 2003 Political Dialogue and Cooperation Agreement. Under the aegis of these agreements cooperation on a variety of areas has taken place (research, student exchanges, combatting drugs, environment, gender, development) (Fairlie Reinoso, 2022).

In terms of the economic relationship, Andean states had preferential access to the European market via the GSP + scheme, but as Peru and Colombia’s economies improved they ceased to be eligible for the scheme, creating an incentive for them to wish to negotiate FTAs with the EU. The EU pushed for a bloc-to-bloc interregional Association Agreement and FTA with the Andean Community. However, such negotiations were precluded by Bolivia’s reluctance and Ecuador initially rejected negotiations due to its opposition to certain intellectual property provisions. The EU agreed to abandon the interregional approach, arguably due to fears of potential loses in EU businesses’ positioning in Peru and Colombia as they entered into FTAs with the US in the mid-2010s (García, 2015; Meissner, 2018), and due to increased competition from China in the region (García and Gomez Arana, 2022).7

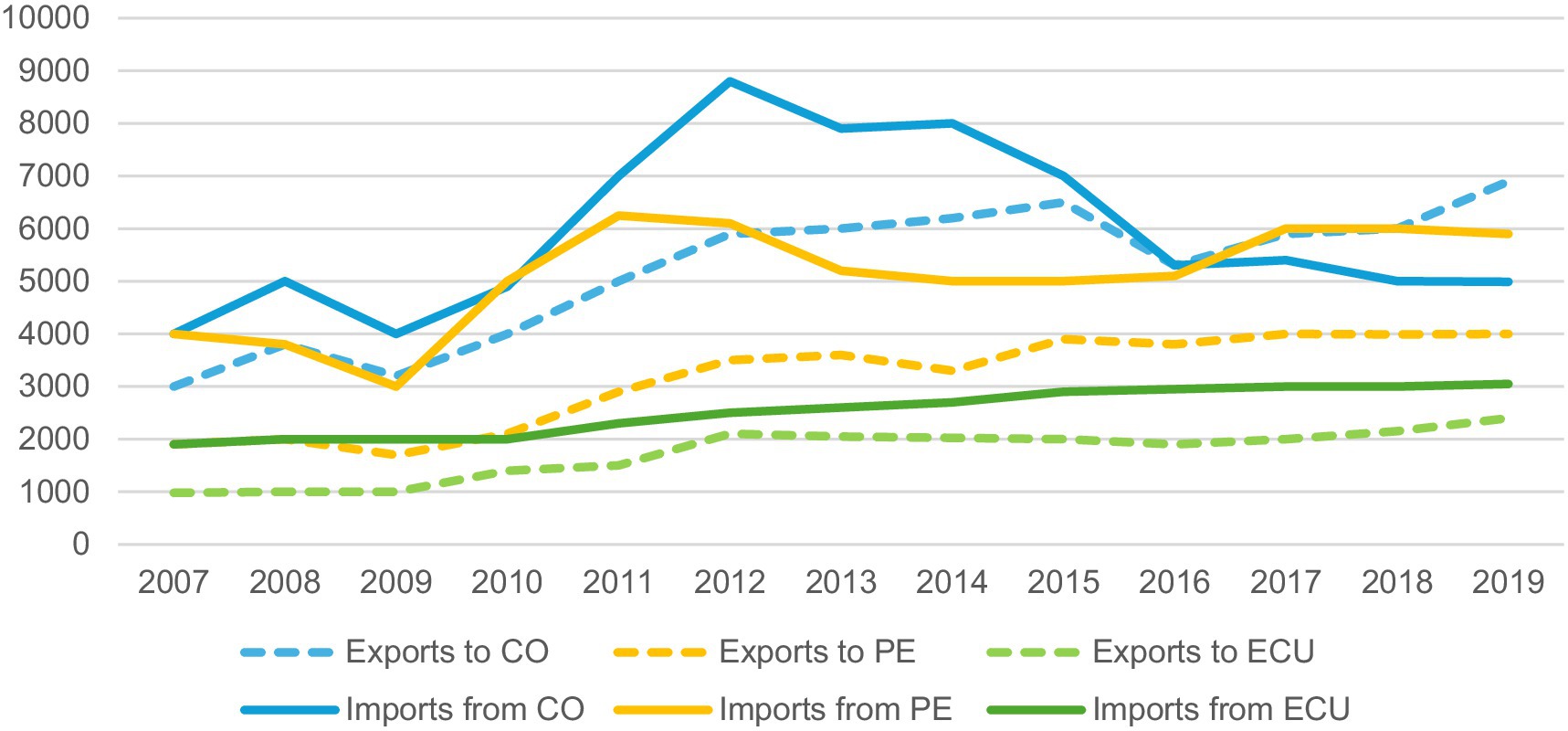

The Multiparty Agreement (MPA) with Peru, Colombia, and Ecuador is an example of hybrid regionalism, however it was crafted in such a way that other Andean Community states could join at a later date, in order to to gradually achieve a full interregional agreement between the EU and Andean Community. The MPA entered into force with Peru in March 2013, with Colombia in August 2013. Ecuador subsequently negotiated its accession, and the agreement applied to Ecuador in 2017 (European Commission, 2025b). The MPA has reinforced the economic relationship, creating stable tariffs and rules for trade and investment. Improved market access has led to a growth in trade between the parties, although this has been tempered by the fact that Andean countries previously had access to GSP (BKP Economic Advisors 2022b; Figure 1).

Figure 1. EU28 bilateral trade with Andean countries, 2007–2019 (EUR million). Source: BKP Economic Advisors (2022b, 31).

Whilst the MPA may not have led to an explosion of additional trade, it is important politically, making Andean states more secure partners with the EU (Interview Andean diplomat 10.5.25). It also creates an important forum and structured relationship to understand and challenge issues that arise that can limit the economic outcomes of the MPA. The case of maximum levels of cadmium in cacao is a case in point. An internal health and safety regulation in the EU lowering maximum cadmium levels in food in 2019, directly impacted on cacao trade from Andean countries. These feared their farmers would be locked out of the EU market with this new non-tariff barrier to trade, as the land in some mountainous regions were naturally higher in cadmium concentrations, and that all production from the country (including that in areas with low cadmium concentrations) could be affected. Such non-tariff barriers reduce the chances of exporting to some places, as well as the volume of exports, and they affect small businesses more (Vázquez-deCastro et al., 2024), and can reduce jobs in the sector (Solar et al., 2025), or lead to costly replacement of cacao production with other crops (Vázquez-deCastro et al., 2024). In keeping with the cooperation spirit of the FTA, the EU ‘is implementing a specific development programme under DeSIRA (Development-Smart Innovation through Research in Agriculture) Initiative, a 6 million Euros intervention on low cadmium and climate relevant innovation to promote sustainable cocoa production in Colombia, Ecuador and Peru’ (European Commission, 2018). The FTA, as part of a broader relationship, thus, presents an opportunity to cooperate in realising political and economic goals, including fostering green economic growth and trade, as ways to revive economies following covid-19 economic contractions (Fairlie Reinoso, 2022). Subsequent sections will focus on how this is evolving in the context of the FTAs.

4 Trade and sustainable development chapters in FTAs

The EU introduced trade and sustainable development chapters (TSD) in its FTAs for the first time in the 2011 agreement with South Korea, soon followed by the agreements with Central America and Peru and Colombia. TSD Chapters cover labour and environmental matters. In these chapters the parties commit to maintaining and upholding domestic laws and regulations on labour rights and environmental protection. They agree to non-derogation of their laws and to work towards improving these and maintaining high levels of protection. They also commit to ratifying and implementing ILO Fundamental Conventions on labour rights and a series of multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs) on climate change, biodiversity, ozone protection. There is also an obligation for the parties to cooperate on these matters, and although some potential examples of cooperation are listed (e.g., sharing best-practices, capacity building), there is no specific commitment to setting aside funds for this. The chapters set up various bodies to monitor the implementation of these matters: a TSD Sub-committee or Board8 that reports to the main Joint Committee governing the whole of the agreement; Domestic Advisory Groups (DAGs) made up of representatives of civil society and business that provide information to the TSD committees and meet with these at an annual Civil Society Forum. A final key characteristic of these chapters is that they are excluded from the dispute settlement mechanism of the FTAs. TSD disputes regarding non-implementation of the chapter are resolved via consultations between the parties. If no solution is found the matter can be referred to a panel of experts that will propose a series of recommendations for action. There is, however, no mechanism to force the implementation of recommendations.

An extensive academic literature has evolved around TSD in EU FTAs explaining the rationales for inclusion of these chapters in FTAs (Orbie et al., 2009) including the role of pressures from the European Parliament; and the evolution of these chapters over time. Analyses focused on the implementation of, and effectiveness of these chapters have tended to prioritise the labour aspects of TSD and have been very critical of the absence of legally-binding dispute settlement mechanisms for TSD (Harrison et al., 2019; Campling et al., 2016; Marx et al., 2016; Orbie et al., 2017; Van Roozendaal, 2017). South Korea, which delivered the first, and to date only, full dispute settlement procedure under the TSD chapter, over trade union laws, has been the subject of focused scrutiny (Van Roozendaal, 2017; García, 2022), as has the Multiparty Trade Agreement with Andean states (Marx et al., 2016; Orbie et al., 2017). This responds to the challenging situation of trade unions in these countries, and, in the case of the Andean states, the roadmaps for labour that were contingent on European Parliament approval for the MPA. Transnational links among the labour movement, and their greater activism within the Civil Society Forum and Domestic Advisory Groups established in the TSD chapters of FTAs, in spite of the limitations of these (Orbie et al., 2017; Potjomkina et al., 2023; Drieghe et al., 2022), also helps to account for the greater salience of this side of the TSD chapters (Interview EC Official 24.10.24).

Literature on the environment side of TSD has a descriptive slant comparing environmental provisions in EU and other FTAs (Velut et al., 2022; Jinnah and Morgera, 2013; Nessel and Orbie, 2022) and explaining the evolution of environmental provisions and dimensions of legal enforceability (Durán, 2023). A focus on the implementation of environmental aspects of TSD chapters is recent and has considered the framing of climate change in TSD implementation discussions (Bögner, 2025) the functions of the TSD Committees (García, 2025), and the discursive delineation of trade-sustainability communities in the negotiation and implementation of TSD chapters (Happersberger and Bertram, 2025).

This contribution, by contrast, forges a new path of inquiry by focusing on the implementation of the environmental aspect of TSD chapters from the perspective of the dynamics present in the interregional relationship between the EU and Latin American groupings and exploring how values, different commitments, priorities and approaches to climate and environment challenges shape TSD chapters’ implementation.

5 Empirical strategy and methods

We leverage publicly available documents accessible through the European Union’s CIRCAB document repository, complemented by eight open-ended elite interviews9 with EU and Latin American officials involved in the implementation of the FTAs for the purpose of triangulation, to conduct a qualitative thematic content analysis (see Braun and Clarke, 2021) aimed at determining key environmental priorities as articulated in the implementation processes of the inter-regional trade agreements that the EU has subscribed with groups of states in Latin America. This is particularly relevant as EU-Latin America interregional relationships have been characterised by non-legally binding cooperation frameworks, whereas the FTAs represent legally-binding texts governing the economic relations between the EU and some Latin American countries.

The two cases scrutinised: the trade pillar of the Association Agreement between the EU and Central America (Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama), and the Multiparty Trade Agreement between the EU and Peru, Colombia and Ecuador, have been selected for the following reasons. The agreements represent the EU’s only agreements outside the development-led Economic Partnership Agreements under the Yaoundé Convention, with groups of states operating within previously established regional integration frameworks. Both agreements entered into force provisionally in 2013, making them some of the first post-Global Europe (European Commission, 2006) Strategy EU trade agreements (after the one with South Korea) to be instituted. The longer implementation period allows for observations over time to discern evolution in priorities. From an environmental perspective the regions covered by these agreements are rich in biodiversity, forest reserves and marine environments, and have become especially relevant in the context of climate change, both as important carbon sinks (Amazonian region) and vulnerable areas given their exposure to climate change. These would, therefore, be cases where we would expect to observe a higher degree of commitment to environmental activity, cooperation and measures being articulated through the implementation of the FTAs. We would also expect to observe a focus on cooperation activities for the implementation of TSD chapters with a clear regional dimension, given that climate and environmental matters transcend borders, and more importantly, the interregional nature of these FTAs.

To ascertain this, we rely on public documents, including FTA implementation reports produced for the European Commission by external consultants. These reports reveal ambiguity as to the environmental impact of the FTAs. On the one hand they report positively on increased trade in sustainably produced goods, on the other they highlight that the increase in agricultural production for exports may be increasing pressure on water usage and the use of pesticides. Given the challenges in determining the environmental impact of the FTAs and isolating impacts from broader trends (e.g., increased production for other markets, business decisions independent of the FTA, commitments to other international agreements), as evidenced in the reports, we delve deeper into the environmental discussions and measures within the context of the FTA, by examining outputs from the Trade and Sustainable Development Committees for the implementation of the FTAs. Subcommittee meeting minutes are available to the public. They have inherent limitations as they represent mutually agreed summaries of discussions in those meetings. Some governments are less prone to transparency and limit the information contained in the minutes (Interview EC official, 14.10.24). Minutes with the Andean states typically double in length those with Central America. The nature of the summaries mean that it is not possible to garner information about how long particular items were discussed for, and the overall tone of the minutes is neutral.

However, despite their limitations, they reveal which issues are highlighted by each of the parties, where their priorities lie, and what their key environmental concerns are in relation to the FTAs, and offer valuable, if limited, insights into the operation of the Committees. Elite interviews with Latin American diplomats and European Commission officials who participate in the TSD Committee meetings serve to triangulate and verify our interpretations of the minutes’ data, and afford additional nuance to better understand the priorities of the different states involved in the FTA implementation, their concerns and nature of the actual discussions.

Recent scholarship has shown the potential for exploiting this source of data. Similar minutes have been analysed to uncover how, despite general commitments to climate change, climate is discursively discussed mostly in terms of trade in these Committees (Bögner, 2025), and to explore the different aspects of the monitoring function of these Committees revealing a predominant function as a locus of information exchanges (García, 2025). For the purposes of this article, the corpus includes all minutes available from the TSD Committees meetings with Central America and with Andean states in the MPA. In the case of Central America, minutes are available for all 10 annual meetings (2014–2024), for the Andean states it is minutes from the 5 to the 10th meeting (2018–2023).

The minutes are coded using qualitative content analysis software (NVivo). Codes are derived from environmental themes that appear in the TSD chapters of the FTAs (e.g., climate change, multilateral environmental agreements, biodiversity). Following an initial reading of the documents and coding for these pre-determined codes, additional codes are inductively generated to include themes or initiatives not originally mentioned in the FTAs (e.g., new EU unilateral sustainability and trade measures).

Further codes are created to take account of domestic initiatives demonstrating significant innovation and international leadership in terms of environmental protection or climate change measures. This facilitates an understanding of who is prioritising certain issues and also of the domestic context, e.g., a country displaying leadership on climate change will encounter less friction in the implementation of TSD chapters in FTAs. Codes to reflect requests for additional information, actions or support are created to capture national priorities and the hierarchy of these priorities. All themes coded are also coded to each the reporting party (i.e., the EU or one of the Latin American states). This allows for the creation of matrices showing the frequency with which each party provides updates on particular themes and raises concerns about specific themes, enabling us to elucidate on their priorities, and how these are then hierarchised in the relationship.

5.1 Analysis of the implementation of TSD chapters in the FTAs

TSD Chapters define the operation of TSD Committees. These are tasked with various functions related to the monitoring of the implementation of the commitments undertaken in the FTA. These include informing the other parties of environmental law and policy developments and progress in complying with MEAs, holding each other to account and policing each others’ implementation, and cooperating with one another. Of these, the information sharing function is predominant across TSD committees (García, 2025). Nonetheless, through the other functions the meetings afford other parties an opportunity to ask for clarifications, request more information on progress, demand additional actions be taken, ask for support, and to suggest and report on cooperation activities and joint projects. Meetings are short and only take place annually, but cooperation activities and further technical exchanges of information take place between individual officials in between meetings.

In the context of EU-Andean States and EU-Central American TSD Committees, sharing information and reporting on policy developments is, indeed, the key activity reflected in the various minutes. Given the similarity in TSD chapters, especially in these two quasi-contemporaneous FTAs, all minutes share a format and the themes discussed. Meetings are divided into four substantive parts: (1) updates on labour (including implementation of ILO conventions); (2) updates on environment (including implementation of MEAs, positions at MEAs meetings, and NDC updates); (3) updates on cooperation initiatives (including EU funded projects); (4) updates on selection and working of Domestic Advisory Groups (DAGs).10

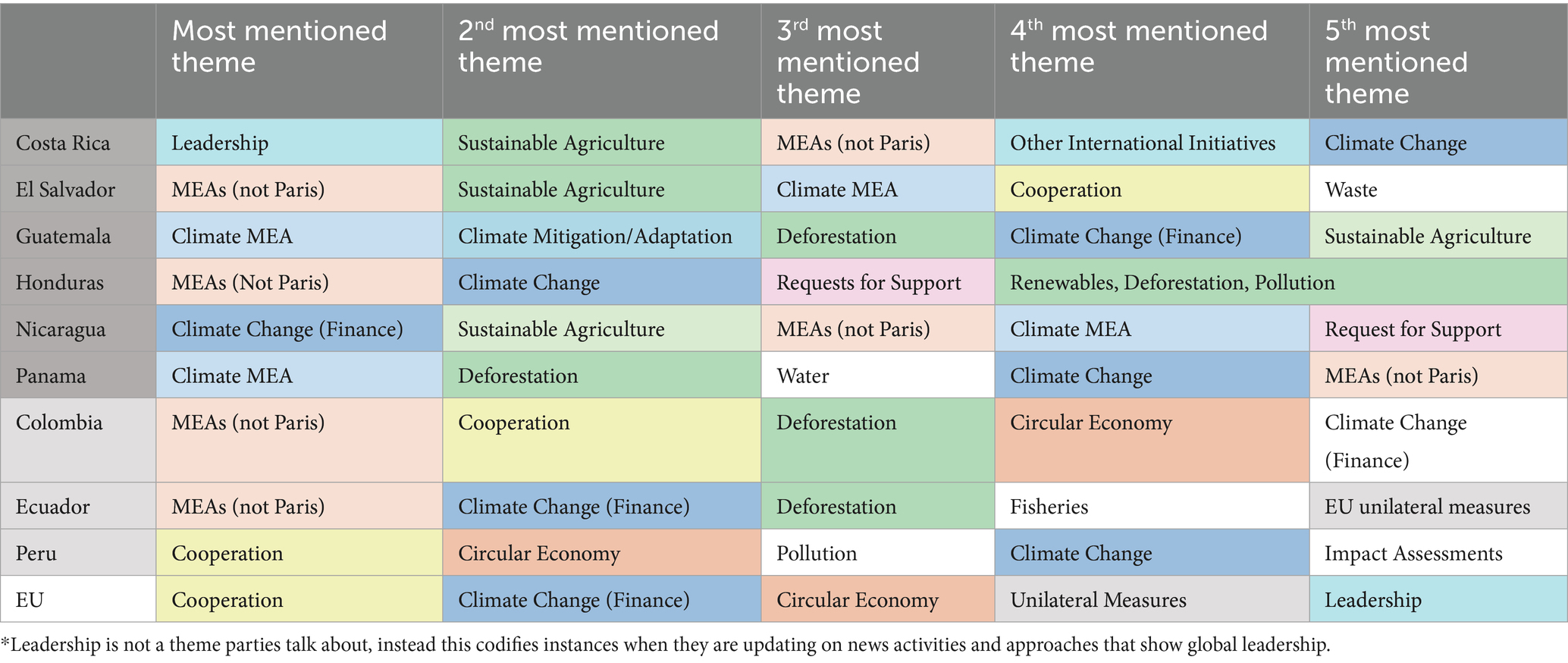

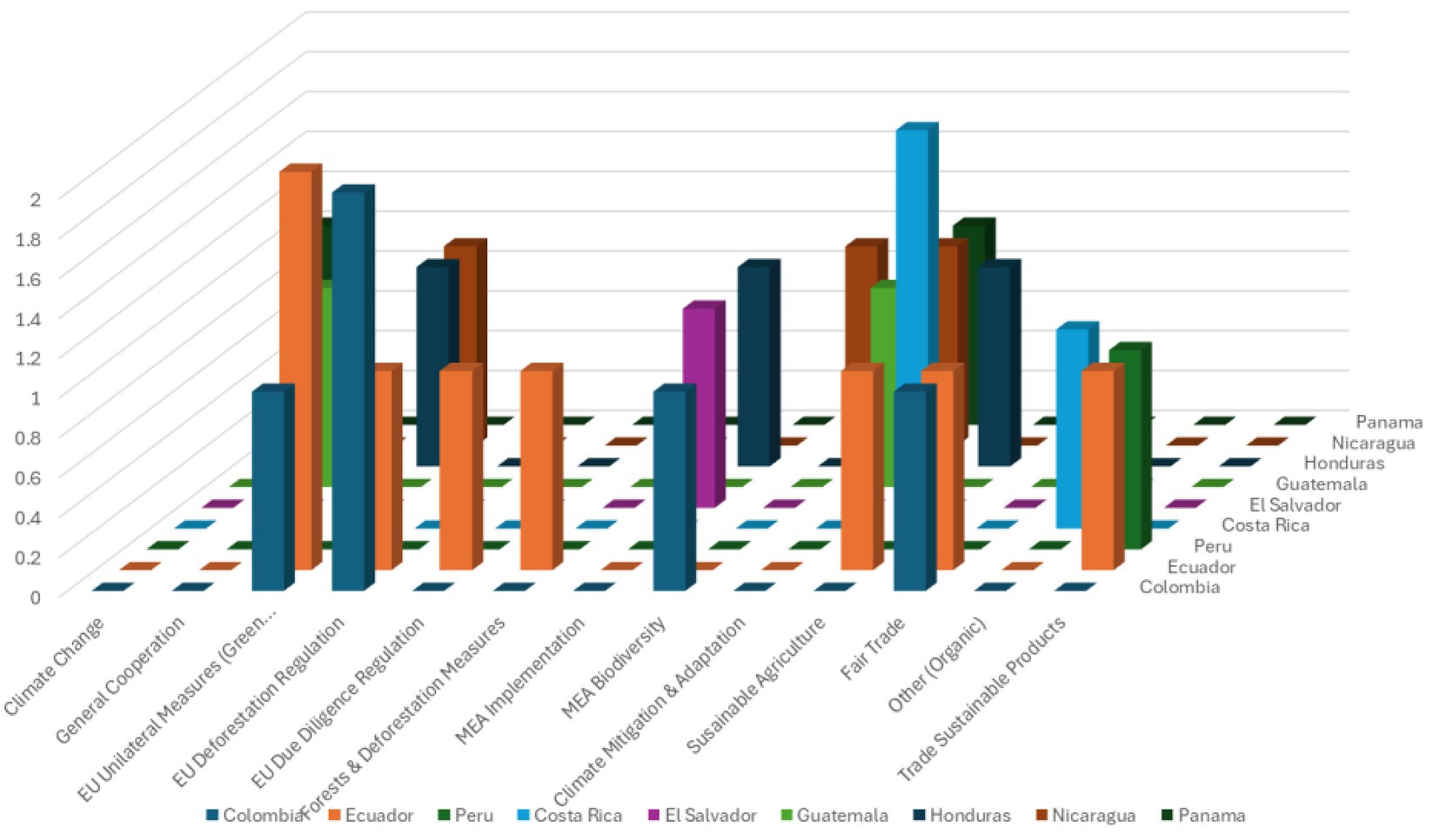

All meeting minutes reflect the same themes, however, there are noticeable differences in terms of the themes that each reporting party mentions more frequently, which we interpret as an indication of prioritisation by the party in national policies.11 Discussions on environment and climate feature the same general themes: MEAs, climate change policies, nationally determined contributions (NDCs) emission lowering targets to comply with the Paris Agreement, environmental law reforms, green policies, deforestation and biodiversity. Table 1 summarises the most prevalent themes discussed by each reporting party, and issues on which they offer more updates.12

Tackling Climate Change is prioritised by all parties. This includes legislation and policies (captured in Climate Change code), including proposals and government commitments on finance, implementation of Paris Agreement (Climate Change MEA code) which includes updates on NDCs. The predominance of climate matters as a key motivation for public policy actions is unsurprising given the critical relevance of this matter globally and within these regions. The EU aims to lead the global fight against climate change, and Central American states are especially vulnerable to this, whilst Andean states are under pressure via international climate regimes to preserve the Amazon, as the ‘planet’s lungs’. Moreover, there is broad consensus on the importance of tackling climate change, even if there may not be alignment on how to achieve this (Interview DG Trade official 24.10.24, Andean diplomat 15.5.25). This is clearly reflected in Panama’s reminder of the need for a ‘just transition under a framework of common but differentiated responsibilities’ (9th EU-CA meeting).

Central American and Andean states are very active when it comes to the implementation of MEAs, in particular the Convention on Biodiversity and new additions like the Kumming-Montreal Protocol. This is an issue they report on frequently under the MEA (not Paris) category which refers to the Convention on Biodiversity and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). Another important area of activity is the development of laws and projects to prevent and reverse deforestation, a matter of concern in and of itself, but also closely linked to habitat conservation and biodiversity, as well as climate issues. The minutes also reveal the temporal evolution of environmental policies and approaches. The original FTAs do not highlight the circular economy, yet, over time the EU, Colombia and Peru, and later Ecuador and Costa Rica have reported on how this concept has become an ever more important component of their environmental and climate policies, as recycling can reduce emissions from increased production. The theme gains importance at the 6th MPA meeting (2019), and the 7th EU-CA meeting (2021), as the EU’s Green Deal places greater emphasis on this, and Andean states, in particular, advance in this matter.

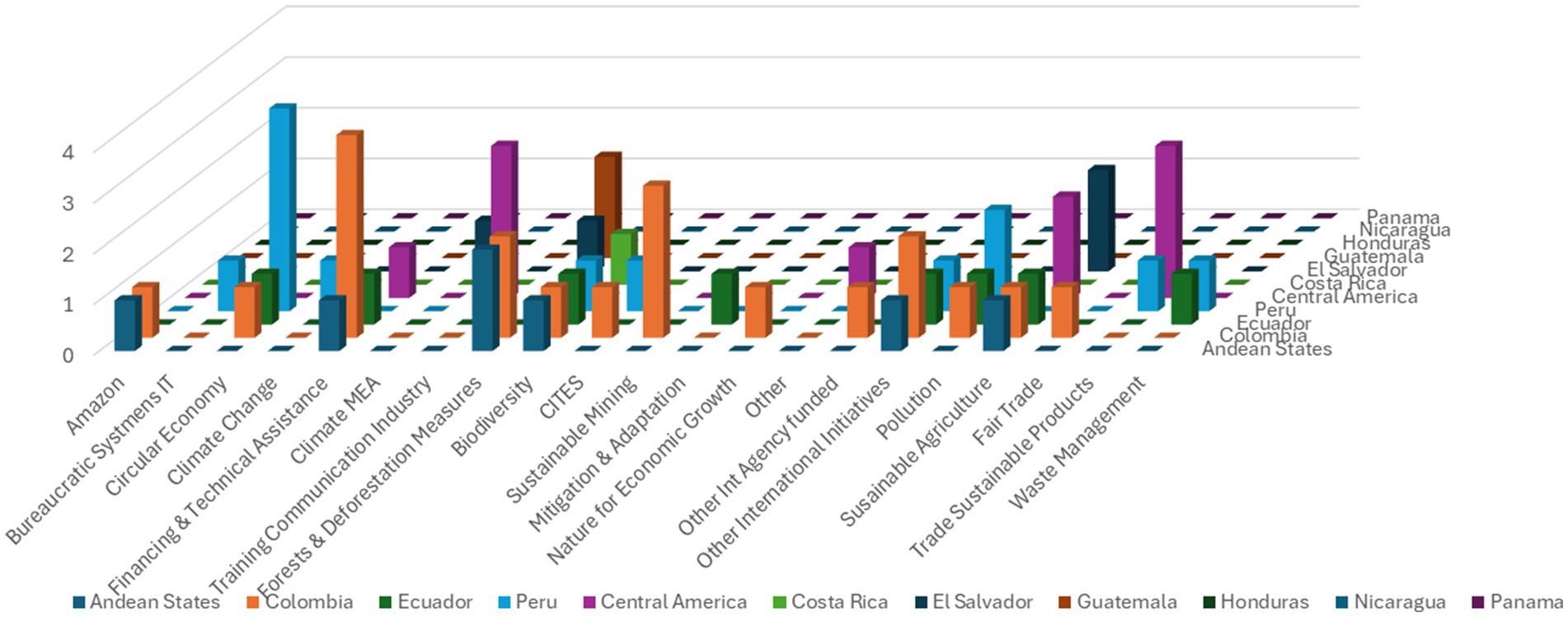

In 2019, Peru reported it had established Latin America’s first Circular Economy plan, whilst Ecuador was in the process of developing a white paper on the matter. By the next meeting, Colombia too, had developed a National Circular Economy Strategy. In February 2021, an international initiative on the circular economy was launched, the Global Alliance for the Circular Economy and Resource Efficiency, which the EU and Peru both joined, demonstrating increased international activity on this specific matter of relevance to the fight against climate change and environmental damage. Peru demonstrated its advances and leadership on this matter further through its involvement as a leading member of the Coalition for the Circular Economy in Latin America and the Caribbean (8th MPA meeting). Specific mentions also appear showing that from 2020 cooperation activities between the EU and Peru and Ecuador on this theme are taking place: Ecuador referenced work with the EU to promote responsible consumption, and Peru highlighted European support delivered through the EU’s EuroClima+ programme and its multiannual indicative programme for Peru (2021–2027). In the case of Central America, in 2021 the EU ‘invites Central American countries to join the Global Alliance’ launched earlier that year (7th MPA meeting), and Guatemala reports on its specific plans at the 10th EU-CA meeting (2024). Reports on general national climate plans and strategies also mention the circular economy as an area to consider and work on.

The case of the circular economy illustrates important characteristics of the practical role and impact of FTA TSD chapters in advancing and developing climate and environmental policies: (1) Chapters and FTAs are living agreements, they create frameworks within which the relationship between the parties can evolve and discuss and resolve differences related to the FTA; (2) TSD chapters’ cooperation pillar is indeed resulting in activities in support of improved policy development and implementation; (3) The interregional relationship is a complicated one, in part due to web of overlapping initiatives and the diffusion of institutional responsibilities across EU departments. Whilst interest in cooperating on the circular economy is highlighted in the context of FTA TSDs, the European Commission’s Directorate General (DG) for Trade and Economic Security, who bears responsibility for the implementation of the FTA, has no funds to engage in activities with partners, therefore limiting what can be done within the context of the FTA. Instead, officials may relay partners’ interest to their colleagues in DG International Partnerships (INTA) dealing with relations with developing economies, which does have a budget for cooperation projects (Interview DG Trade official, 24.10.24).

Deforestation is another key area where Latin American countries are reinforcing legislation and action plans, as reflected in the number of advances they are reporting in TSD committee meetings, demonstrating clear commitments to this matter. As mentioned previously, the value of measures in support of the environment is not questioned, it is the cost that can be an obstacle. In the case of measures to tackle deforestation, a series of EU projects offer some support to the region. These include: ‘Zero deforestation and traceability in Guatemala’ co-financed by the EU and Germany, which is part of larger Team Europe Initiative for business and biodiversity in Central America and the Dominican Republic, to support sustainable growth and jobs (10th EU-CA meeting); Five Great Forests of Mesoamerica, spearheaded by five EU member states to transform agriculture and food systems and protect intact forest ecosystems (see European Commission, 2025a); as well as bilateral partnerships established under the aegis of international agreements like the Glasgow Declaration on Forests and Land Use of the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (8th EU-CA meeting). Indeed, beyond the scope of the FTAs, the EU channels significant funds to UN agencies whose projects then support technical assistance to these countries to design customised NDCs, regulations, development of their own ETS, although this support is less visible (Interview DG CLIMA official 20.6.25).

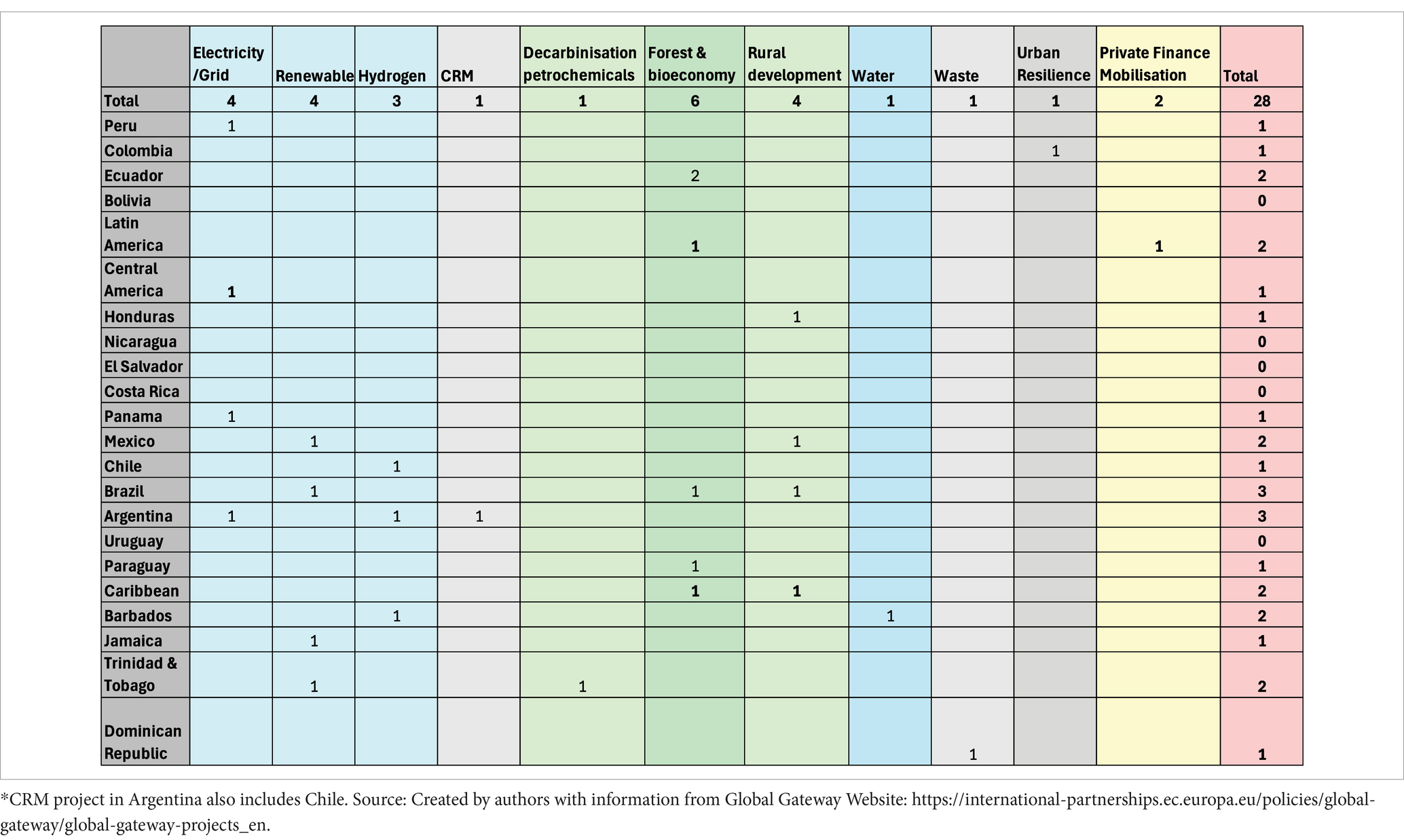

Cooperation activities related to TSD chapters, even if carried out under other initiatives reveal coinciding topic priorities. The EU’s flagship programme for engaging developing economies, the Global Gateway, prioritises climate change and the environment in projects financed in Latin America, with 55% of projects devoted to climate and the environment, and the rest to transport, health, education and digital. Table 2 shows the key environmental initiatives in different countries under Global Gateway and how forest conservation, bioeconomy and the closely related rural development are especially relevant.

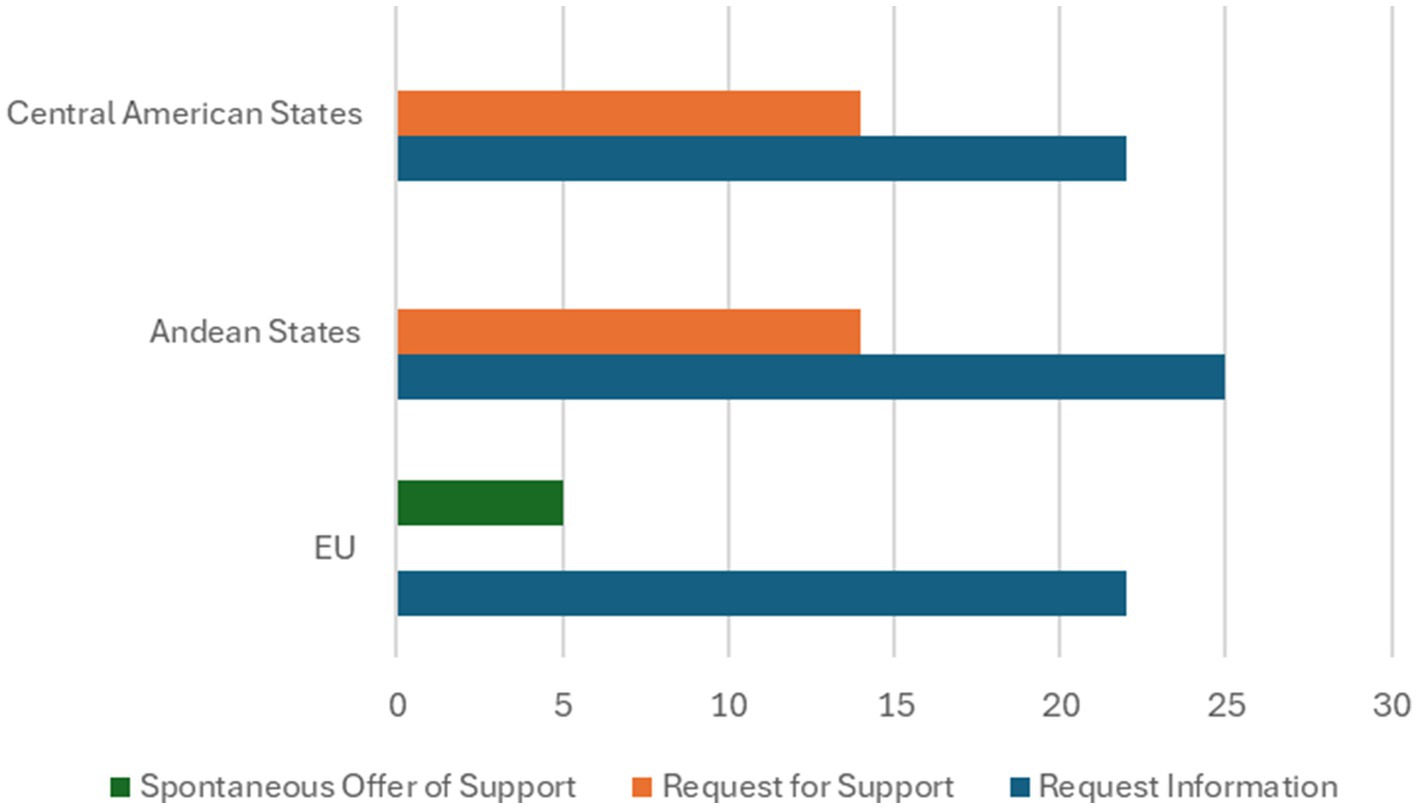

Despite agreement on the importance of the climate agenda and on core areas to prioritise within that agenda, there are also frictions and instances of misalignment of priorities in the relationship. Beyond presenting updates on legislation and its implementation, TSD committees also serve as a locus for the parties to challenge one another’s policies and implementation of the commitments in the TSD chapter of the FTA. This typically takes the form of asking the other party for more information on a policy measure or plans for that, or asking for progress reports on an issue area. Under these agreements there has been no recourse to the dispute settlement mechanism to settle implementation problems, which would represent the strongest challenge to a party’s implementation strategies. Nonetheless, the analysis of minutes suggests that when it comes to questioning other parties, requesting progress reports and encouraging further actions, there are clear differences in the behaviours of the parties, reflecting the asymmetric nature of the relationship.

The EU is more likely to demand additional progress information from other parties. This is especially evident in the labour section of TSD meetings. Trade union members of DAGs possess more specific information regarding the situation in other countries through their transnational networks and are more active in raising attention to these matters (Interview EESC 27.5.25). Additionally, ILO conventions and reviews provide explicit and clear action plans, whereas when it comes to climate matters international regimes are less specific on how implement ambitions (Interview DG Trade official 20.10.24).

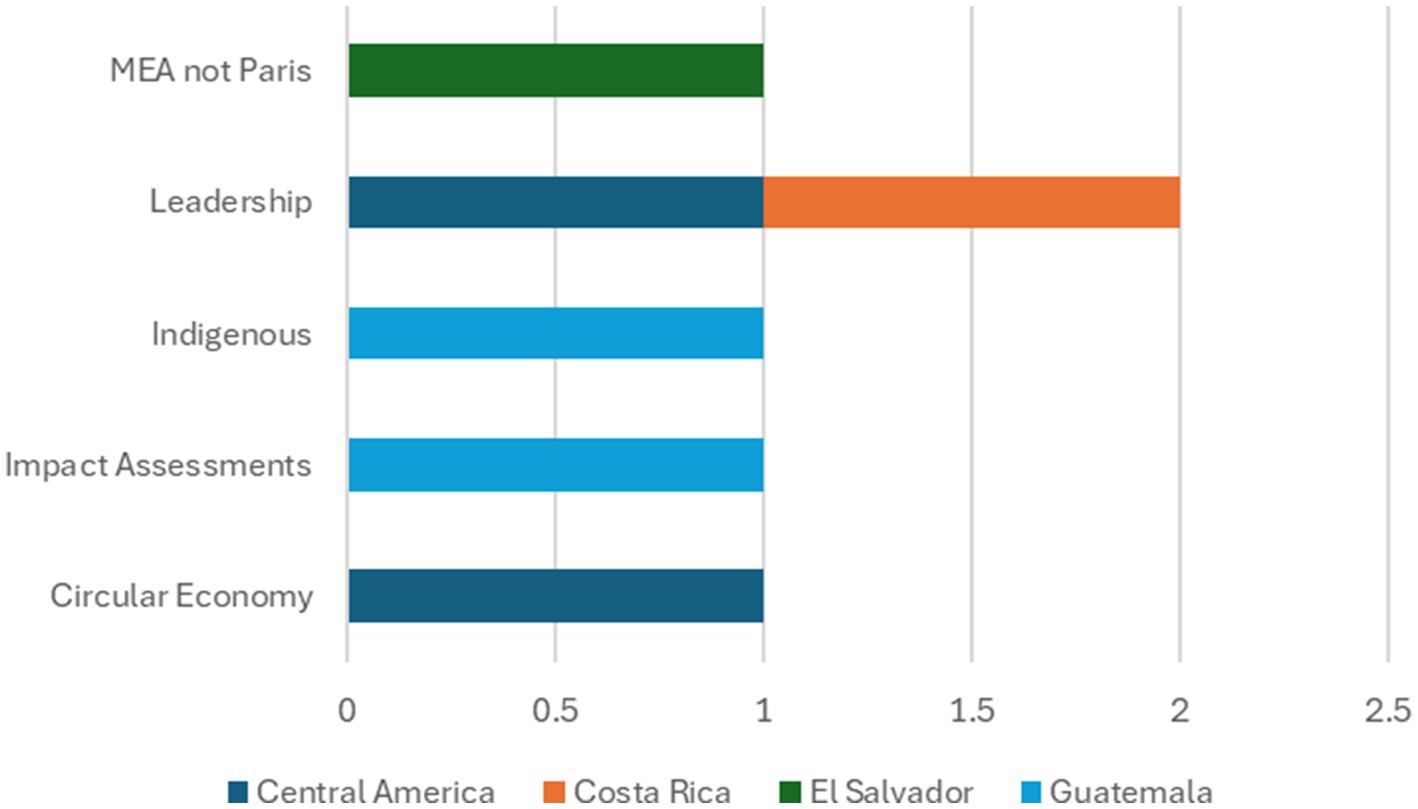

In the case of the environment, as Figure 2 summarises, Andean states and the EU make the most use of the possibility of requesting more information from the other party. Andean and Central American states use this forum to request support, financial and technical, to adapt to EU regulations and specific requirements for market access.

The EU makes more requests for progress reports on a variety of issues and from most parties. By and large, these are demands for more action and express concerns. For instance, on the issue of mining the EU ‘expressed interest in learning about the latest developments in the fight against illegal mining (in Colombia) and conveyed civil society’s concerns about the impact of these activities’ (7th MPA meeting). It also highlighted concerns about ‘the long-year opposition by Guatemala to the listing of a hazardous pesticide (“paraquat”) under the Rotterdam Convention on the Prior Informed Consent Procedure for Certain Hazardous Chemicals and Pesticides in International Trade’ (6th EU-CA meeting), which Guatemala agreed to discuss bilaterally.

Fisheries, in particular measures to tackle illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing (IUU) are an issue where there are strong demands for action and oversight on the part of the EU. For example, the EU requested that the Ecuadorian draft law on fisheries resulting from the discussions in the corresponding Committee in the National Assembly be shared with the EU experts in DG MARE (6th MPA meeting). Demands in the context of TSD meetings complemented EU unilateral actions beyond the scope of the FTA regarding IUU fishing. The EU’s 2008 Regulation on IUU fishing bans products of IUU from the EU market, requiring exporting countries to demonstrate they implement strict laws to vanish such practices. The Regulation gives DG MARE in the European Commission the capacity to work with other countries to monitor and influence their IUU fishing laws and implementation, and to issue a ‘yellow card’ to countries as a step before an outright ban of fish imports from that country. Following years of monitoring and demands for more action, and despite legal advances, in 2020, the EU issued a ‘yellow card’ to Ecuador, considering attempts to combat illegal fisheries insufficient, and demanding more work with DG MARE (7th MPA meeting). On issues where the EU has resort to unilateral trade measures with possible economic repercussions, the TSD meetings serve as additional forum to pressure parties to comply and a locus for a more political discussion (as opposed to the technical nature of interactions with DG MARE), and serve to provide accountability (Interview DG Trade official, 4.10.24).

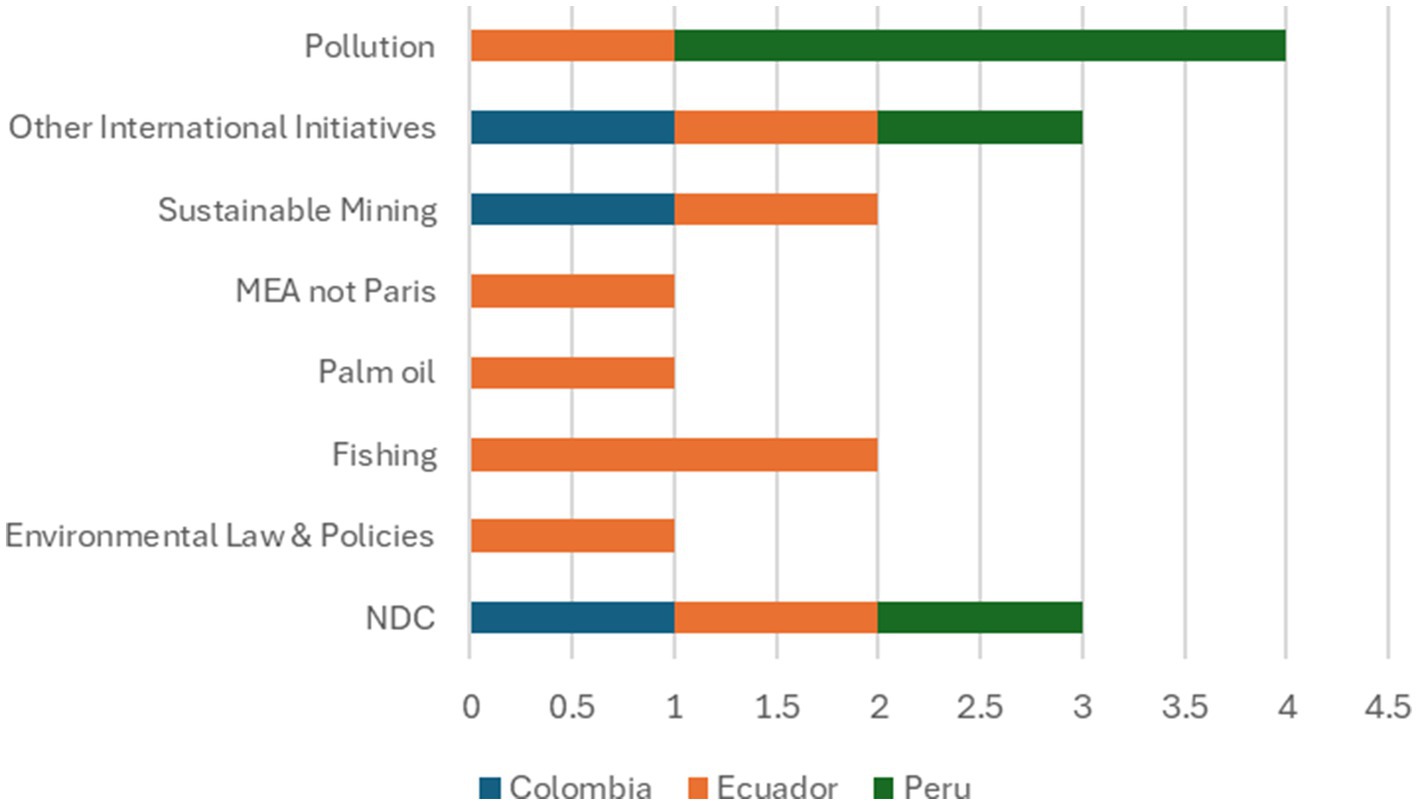

It is important to note, that although, far less frequent, there are also requests for information based on genuine interest and a desire to learn more about others’ approaches to environmental matters. A key example of this relates to requests for additional information on the plurilateral Agreement on Climate Change, Trade and Sustainability (ACCTS), of which Costa Rica is a founding member (6th EU-CA meeting). Figures 3, 4 provide an overview of the environmental themes on which the EU pursues increased action and reporting from Latin American countries.13

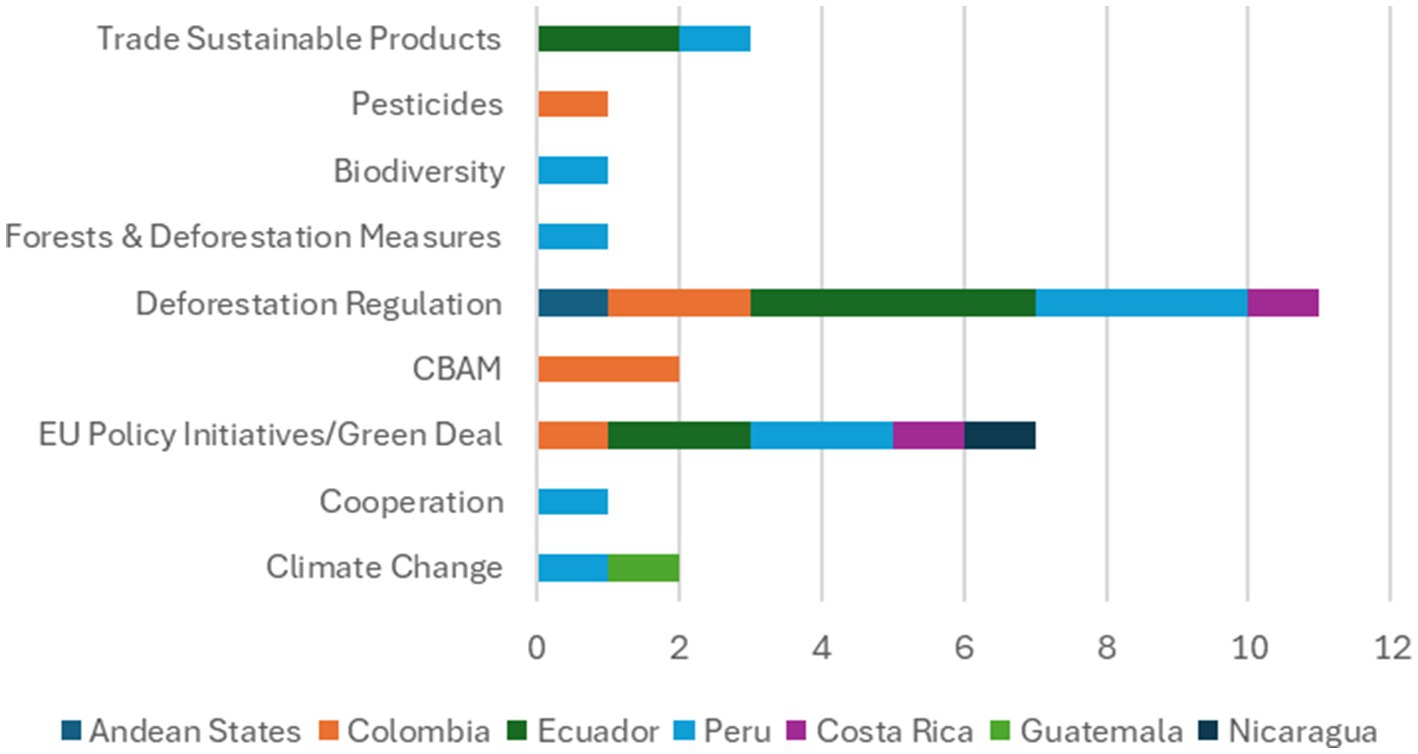

Latin American states, for their part, as shown in Figure 5, have overwhelmingly requested more explanations from the EU on its unilateral measures that could affect trade with them and limit the market access gains achieved in the FTA. Requests have concentrated on the EU Deforestation-free products Regulation, and to a lesser extent more general questions around how the Green Deal might affect these countries. Andean states have been especially critical of the EU Deforestation regulation, and been insistent in demanding clarifications about how it would be applied.

The EU Deforestation-free Products Regulation (EUDR) (EU Regulation 2023/1115) was highly controversial, especially in agricultural commodity producing countries (Berning and Sotirov, 2024). The Regulation targets the importation of products like cacao, coffee, timber, palm oil, rubber, soy, cattle and derivative products (furniture, leather, beef, and chocolate). It requires importers to demonstrate that the product has not been produced in forested land that was cleared for the purpose of production after December 2020, and imposes strict due diligence requirements.

Countries in the region have been interested in, and active in combatting deforestation, as evidenced in the number of updates provided in TSD meetings, and specific programmes to guarantee key agricultural commodities are not the product of deforestation. For example, Costa Rica with the programme ‘Café Libre de Deforestación’ supported by United Nations, has been very successful thanks to the centralization of due diligence under ICAFE. The progamme ProAmazonia against deforestation while growing cacao (before the EUDR) and Ecuador, the agreement on Acuerdo Cero Deforestación for Palm oil in Colombia (2017), and a similar one in Guatemala, are other examples (Soto and Parada, 2025).

Despite these advances, exporting countries have expressed their concerns about potential trade diversion if their producers, especially smaller scale farmers are unable to meet the onerous requirements (including geolocation information) to demonstrate compliance with the Regulation (Solar et al., 2025). Peruvian and Colombian concerns have been raised about the lack of consideration for local contexts (Interview Andean diplomats 17.5.25).

Peru’s concerns specifically relate to challenges to align EUDR implementation with ‘national legal requirements against a background of fragmented laws presents a challenge, geolocalization, implementation costs and EU cooperation, benchmarking requirements, gaps in the EUDR and a short implementation timeline’ (Solar et al., 2025, p. 6–7). In preparation for EUDR, Peru already started a series of reforms specifically targeting smaller farms. By 2021, the first draft of a bill that aimed at simplifying the legal status of lands used by small farmers in forest areas converting them into private properties, was already being discussed by the Peruvian Congress (Peña Alegría, 2024). With the EUDR expected to be implemented in 2024, and thousands of small farmers not being able to comply with this European directive due to their lack of ownership of the lands, the Congress decided to approve the new Bill in December 2023, among other reasons (Peña Alegría, 2024). However, this development was controversial, as environmental groups, indigenous communities, and the President, himself, opposed the decision fearing a potential detrimental effect on forest preservation, as it is more difficult to enforce deforestation laws on private properties (Peña Alegría, 2024). Colombia mirrors Peru’s concerns over EUDR, and is especially worried about the Regulation’s emphasis on traceability. The use of polygon mapping for traceability with difficult terrain, and different mapping systems and the understanding of the EUDR by small farmers are just some of the obstacles to compliance (Naranjo et al., 2024). As in the case of Peru, the ownership of the land and some informalities associated with land use will add difficulty to the process of traceability (Naranjo et al., 2024).

Local interactions between agricultural production in remote areas and other critical domestic policies have also not been considered within EUDR. For instance, as part of the fight against narcotics production, there are programmes to foster production of other commodities in those areas (Solar et al., 2025). Some of those areas may not comply with the EUDR, but they argue those products should be exempt in order to support communities’ development and the shift away from illicit narcotic production and trafficking (incidentally, a topic that has consistently featured in broader EU-Latin American Dialogues). Andean diplomats expressed their disappointment at the EU’s lack of consideration for their concerns over this proposal despite using every means possible to reiterate this message, including the implementation committees of the MPA. In countries with weaker institutions and lower levels of development, assuming the costs of traceability to comply with EUDR, and with other EU Due Diligence regulations targeting labour and environment including common practices such as child labour in small family coffee farms, may be insurmountable (Melo-Velasco et al., 2025; Chalmers et al., 2024) Given the complexities for businesses to implement the EUDR, the EU delayed its implementation by 1 year until December 2025 to further revise its technical implementation.

Latin American states have used the TSD meetings to request specific support from the EU to compensate for the costs they have to incur to meet the commitments in the FTA and a adapt to EU legislation. Peru, for example, has been vocal in stressing that ‘EU legislation on deforestation-free products stipulated that cooperation activities will be carried out to implement them with the countries concerned, and therefore stressed the need for more details on specific activities, their scope, form and dates when they would be carried out’ (10th MPA meeting). As summarised in Figure 6, most requests for support relate to this Regulation, as well as closely associated areas of deforestation and sustainable agriculture, which whilst not explicitly mentioning the Regulation relate directly to it and its aims.

The EU funds various cooperation activities aimed at supporting green trade, implementation of MEAs, and adaptation to EU legislation (see Figure 7 summarising areas of cooperation). For instance, the Green Business Generation Program in Colombia, co-funded by the EU through then DG DEVCO (now DG INTA). The programme supported the creation of 683 green businesses, 4,835 jobs, and sales worth $118 million, implementing aspects of the National Green Business Plan launched in July 2018 (5th MPA meeting). Ecuador, for its part, has acknowledged financial support from the EU and France and Germany for national projects, and has emphasised the importance of this technical and financial assistance in continuing to advance climate change mitigation and adaptation (7th MPA meeting).

Given their lower level of development, minutes with Central America refer to numerous programmes funded through more general EU development programmes. For example, between 2014 and 2020, the EU Regional Cooperation Office provided EUR 120 million for Central America. These funds supported regional economic integration to maximise the benefits of the EU-Central America Association Agreement (including EUR 55 million invested in the Regional Strategy for Productive Transformation), security and the rule of law, and climate change and disaster management (5th EU-CA meeting). Significantly, this is the only explicit example in TSD minutes of tangible support for regional integration. Support for integration is in keeping with the aims of interregional relations and the EU’s long-standing support for regional integration and is also consistent with the transnational nature of the climate and environmental challenges. What is surprising is the relative low number of initiatives targeting greater integration and cooperation within the region. There are some specific projects relating to Amazon protection and the 5 Great Forests of Mesoamerica that apply to several countries given the geographic location of these forests, but do not necessarily support nor require regional integration for the management of these areas.

Despite positive attitudes towards support projects, there are limitations, hence the continuous calls for support expressed at TSD meetings. Concerns surround the limited funds the EU devotes to cooperation. As one Andean diplomat put it: ‘the EU has no money for anything, only Ukraine and it has its own huge debt (…)’ (Interview Andean diplomat 17.5.25). Another lamented that EU ‘support often takes the form of technical support, exchanges, seminars, rather than actual investment’ (Interview Andean diplomat 17.5.25). Perhaps more critically, as a Peruvian official pointed out, ‘we can understand that the EU may not have funds, but it can listen and refrain from putting in place regulations, which whilst well-intentioned have unintended consequences for others,’ like reducing competitiveness or weakening Peruvian efforts to combat drug production through the Deforestation Regulation, when the problem also reverts on the EU as the main market for that illicit cocaine (Interview Andean official 15.5.25).

It is these instances that suggest a hierarchical prioritisation of certain issues and concerns over others that belies an asymmetric relationship. Despite generally shared values and concerns on environment and climate, when it comes to specific approaches to this, prioritisation of types of activities and themes within this broad area, there are differences.

Following its 2018 TSD Review, as part of the 15-point Action Plan, the European Commission started to prioritise TSD areas for each partner, including areas for cooperation and where the EU would place greater emphasis for reforms. This followed a practical logic that focusing on fewer themes with each partner could concentrate efforts and result in actual change on the ground. The EU presented its list of priorities to partners, without consulting with them. EU priorities focused on core labour rights matters, environmental protection legislation and consultation with civil society through the DAGs. Latin American states did not disagree with these priorities, however, they expressed their desire for their own priorities to receive equal standing. Colombia expressed its view that the areas identified by the EU are also priorities for Colombia, but wished to include other areas of particular interest to itself such as the circular economy and green business. Peru, for its part, acknowledged the EU priority list as just an EU working document and expressed the importance of addressing priority issues for Peru, such as biological diversity, within the framework of TSD. Ecuador also highlighted the need for a dynamic agenda of priority issues (5th MPA meeting).

Historical EU-Latin America interregional dialogues have been marred by the problem of ‘an asymmetrical power balance leading to EU dominance and ‘ownership’ of the whole interregional process, including the drafting of statements, action plans, its financing and ultimately also its implementation’ (Gardini and Malamud, 2018). FTAs create institutional structures, such as the TSD Committees, that are based on the principle of equality. Moreover, the parties have signed the same legal text, and in the case of TSD chapters have made the same commitments. However, as highlighted by Latin American states in the implementation of these FTAs and in the working of the TSD Committees, the articulation of those commitments is not the same for the parties, nor is the cost. Although the EU has been receptive to FTA partners’ requests for information, clarifications, and additional support on environmental matters, it continues to be the dominant actor when it comes to monitoring others’ actions and legislative processes. EU ambitions to be a global environmental leader, and its own legitimation of trade agreements as a tool for balancing trade and environmental values underpin its focus on performing these behavioural strategies for legitimation highlighted by Lenz and Söderbaum (2023).

Through its new unilateral trade measures in the Green Deal, EU priorities and its vision for tackling the climate/environment-trade nexus is the one that is being prioritised and enacted. Latin American states, are, however, also exploiting the forum offered by the TSD Committees to push back against certain EU measures, most notable the Deforestation Regulation, and increasingly also to demand that their priorities be ranked as highly as EU ones. In terms of mutual learning, Latin American countries are the recipients of EU technical assistance to adapt to MEAs and EU regulations, suggesting a one-way exchange on this matter. As explained above, in most cases this support is requested by Latin American countries. There are instances where countries actively want to learn from, and imitate, EU approaches. Costa Rica, mindful that its largest export market for organic products is the EU, whilst in the process of updating its organic farming laws requested discussions with the EU to model these changes on EU law (7th EU-CA meeting). The parties have also acknowledged that discussions and hearing about others’ climate and environmental policies can also be helpful when they domestically decide to legislate on those matters (Interview DG Trade official, 20.10.24).

Despite interesting innovations in approaches to climate and environment arising in some Latin American states, there is scarce direct evidence of two-way learning. TSD Committee minutes show an interest on the part of the EU on these developments. There are also specific best practice exchanges leading to what an EU official described as some ‘wow moments’ where EU officials discover exciting innovations taking place in Latin American states. For instance, Coalition for Circular Economy in Latin America projects where coffee residue is being turned into plastic, or, outside the scope of this particular article but relevant, a ‘show and tell’ invitation to visit to small hydrothermal plants in Mexico changing waste into methane and gas, an idea the official would like to export (Interview DG ENV 27.5.25). At a purely personal level officials also admit that Latin American approaches towards nature’s rights and indigenous approaches to nature are especially interesting and there could be some interesting lessons there (Interview, DG TRADE 20.5.25). EU policies are developed within a euro-centric perspective, partly due to the complicated internal dynamics of EU policy-making. Minutes of TSD meetings have shown that even in policies designed to impact other countries, consideration of their concerns and realities have only come at later stages, and once others have raised their concerns. There is no evidence that such approaches will change. However, through the exchange of best practices, and EU officials’ increased knowledge and appreciation of others’ approaches to climate and environment, could very gradually in the long-term permeate broader institutional thinking.

The analysis of TSD committee minutes and key informant testimonies reveal that TSD chapters have institutionalised regular practices that include practical information exchanges and performance reviews. In this way the TSD chapters embody what Lenz and Söderbaum (2023) have termed as institutional and behavioural legitimation strategies. The parties’ engagement in this process, particularly the EU’s, enables them to demonstrate a commitment to environmental and climate action as codified in the FTA, and thus, justify the FTA within the interregional relationship.

The findings show that the parties’ priorities for the implementation of specific TSD commitments in the FTAs vary in their focus. The EU places greater weight on the monitoring aspect of TSD chapters implementation, reviewing the performance of counterparts in their environmental policies and laws. This aligns with both the EU’s self-proclaimed aspiration to be a global climate leader, and the need to demonstrate the environmental credentials of the agreements, in response to European public concerns.

Given the regions’ environmental values, all parties are actively upgrading legal and policy instruments to meet international obligations. Notifications of legal changes by Latin American states coalesce around policies to implement obligations derived from multilateral environmental agreements, in particular, those legally-binding ones like CITES, and those on Biodiversity (Ekardt et al., 2023). Approaches to climate change vary according to level of development, Central American states focus on deforestation and sustainable agriculture. More developed states are also developing approaches that coincide with priorities in EU approaches, e.g., the growing significance of the circular economy in Andean climate strategies, in part due to the multiplicity of joint and international fora on these matters. Active interregional cooperation projects on this issue incentivised by exchanges in the TSD committees support the development of policies on this on both sides of the Atlantic.

In terms of the implementation of the cooperation commitments in TSD chapters, Latin Americans have acknowledged EU support for concrete projects of interest to them but have expressed disillusion at the level and type of support available for adaptation to new EU unilateral measures in the Green Deal that could diminish the economic gains from the FTAs. Discussions in TSD committees reveal different approaches to climate and environment: a focus on improving legal instruments and their enforceability, and greening of production and energy in Latin America; and extensive regulatory changes in the EU and EU unilateral trade measures that directly impact on Latin American producers and exporters (among others). Controversies and requests for support and cooperation in TSD committee meetings arise from this mismatch in approaches, and the fact that EU measures require others to adapt and bear the cost of that adaptation.

6 Conclusion

The dynamic implementation of TSD chapters in EU FTAs has been controversial, however, as this article demonstrates, they create an additional and regular forum for discussion of climate and environmental matters. The analysis of the minutes of TSD committee meetings in the MPA and EU-Central America trade agreements unpacks aspects of the operation of FTA implementation committees, and makes an important empirical contribution to literature on climate and environment cooperation in EU-Latin American relations. The article reveals important progress in climate and environment legislation in all the parties, particularly Costa Rica, Andean states, and the EU. The convergence of interests in climate and environment, and shared domestic agendas on these matters have facilitated fruitful exchanges within the context of TSD chapters implementation and the development of cooperation activities. Nonetheless, there is evidence of an asymmetrical relationship in the implementation of these chapters, with the EU demanding action and progress reports from partners more assiduously. Latin American states are increasingly making use of these fora to highlight their own approaches to climate and environment, and to question EU legal developments impacting on them, like the Green Deal and EUDR, and to demand support for compliance and greater consideration of local specificities. Cooperation activities reveal adjustment to the needs and interests of Latin American states on climate and environmental issues. Although a ‘unilateral reflex’ on the part of the EU is still present in the initial presentation of more focused thematic priorities within TSD as part of its 2018 TSD review. The articulation of interregional relations within this setting, thus, retains the imbalances over ‘ownership’ often highlighted in the EU-Latin America relations literature (Gardini and Malamud, 2018), although it is developing into a more equal partnership.

The implementation of TSD chapters demonstrates that despite the absence (in these cases) of legally-binding enforcement mechanisms, the institutional arrangements of the TSD chapters create behavioural norms of accountability and cooperation that are preformed through continuous reviews and discussions, as a legitimatization strategy (Lenz and Söderbaum, 2023) to justify these interregional FTAs. TSD chapters are a useful avenue for the identification and development of cooperation activities to progress on climate and environment within the interregional relationship, although most programmes take place outside the scope of the TSD chapters and FTAs, be it through EU development initiatives or UN or other international cooperation activities. It is also notable that, despite the overarching regional nature of these FTAs, much of the cooperation remains bilateral with individual countries, reflecting the different levels of engagement with climate and environmental reforms and different specific challenges in each country and national legislations, and the absence of a concerted regional approach to the matter.