- 1Meharry Medical College, Sayreville, NJ, USA

- 2Department of Psychiatry, Meharry Medical College, Nashville, TN, USA

- 3Residency Training Program, Psychiatry Externship Program, Division of Forensic Psychiatry, Meharry Medical College, Nashville, TN, USA

A disability assessment for non-therapeutic reasons is the most common evaluation requested of treating psychiatrists. Mental disorders affect approximately 20 percent of Americans each year. People who are unable to work need some financial assistance. As part of the system, it’s our goal to assist them in this process. When a disability claim is filed, psychiatrists take into account the individual’s impairments and disabilities. A psychiatrist’s evaluation of disability involves knowledge and experience. There are many ethics related challenges, especially when performing disability evaluation of their own patients. Disability training should therefore be part of residency curriculum for training of psychiatry residents.

Psychiatrists are often unaware of the process of disability evaluation, as psychiatric residencies mostly do not train residents how to conduct them. This area of need prompts the necessity to outline guidelines that could assist psychiatrist in performing an accurate and valuable psychiatric disability evaluation.

According to different laws and insurance companies, Disability is a legal concept with more than one definition. It is similar to a competency but quite different from Impairment.

The most recommended American Medical Association Guides to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment Guides (AMA’s), Fifth Edition (Andersson and Cocchiarella, 2008) defines Disability as an “Activity limitation and/or participation restriction in an individual with a health condition, disorder, or disease” (Andersson and Cocchiarella, 2008, p. 5) and Impairment as “a significant deviation, loss or loss of use of any body structure or body function in an individual with a health condition, disorder or disease” (Andersson and Cocchiarella, 2008, p. 5).

An impairment “results from anatomical, physiological, or psychological abnormalities which can be shown by medically acceptable clinical and laboratory diagnostic techniques” (United States Social Security Administration Office of Disability Programs, 2005). World Health Organization (WHO) defines Impairment as “problems in body function or structure such as a significant deviation or loss” (World Health Organization, 2002, p. 10). There are different classifications of impairment used which include the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) World Health Organization (WHO) (2001); Social Security Administration regulations C.F.R. pt. 404 (2005); DSM-IV-TR Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) Scale (American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

Disability evaluation is often referred as an independent psychiatric examination that can be requested by employer, government institutions, insurance agencies, or either party in litigation. The purpose of such reports is to help them decide their course of action such as providing healthcare benefits or arranging damages and workplace accommodations.

Currently there are no standardized tests to evaluate an applicant’s mental health that could directly determine disability. Rating scales are sometimes helpful in quantifying impairment although not recommended. DSM GAF Scale (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) is a standard diagnostic assessment most commonly applied.

The AMA Guides (Andersson and Cocchiarella, 2008) advices physicians to maintain confidentiality while evaluating disability cases. It’s difficult routinely because of third-party evaluations, but a psychiatrist should try his level best in doing so. A consent form for release of pertaining relevant information (C.F.R. §164.508 (b)(4)(iii), 2007) according to The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) (1996), should therefore be included as part of the records. Though there exists a limited doctor patient relationship (Weinstock and Garrick, 1995; Weinstock and Gold, 2004; Baum, 2005) in such evaluations, problem arises when a psychiatrist attempt to plays the dual role, as a treatment provider and that of an evaluator. This can lead to conflict of ethics. The American Academy of Psychiatry and the Laws (AAPL’s) guideline, therefore suggests that the primary treating psychiatrist avoid performing evaluations for legal purposes of their own patients (American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 2005).

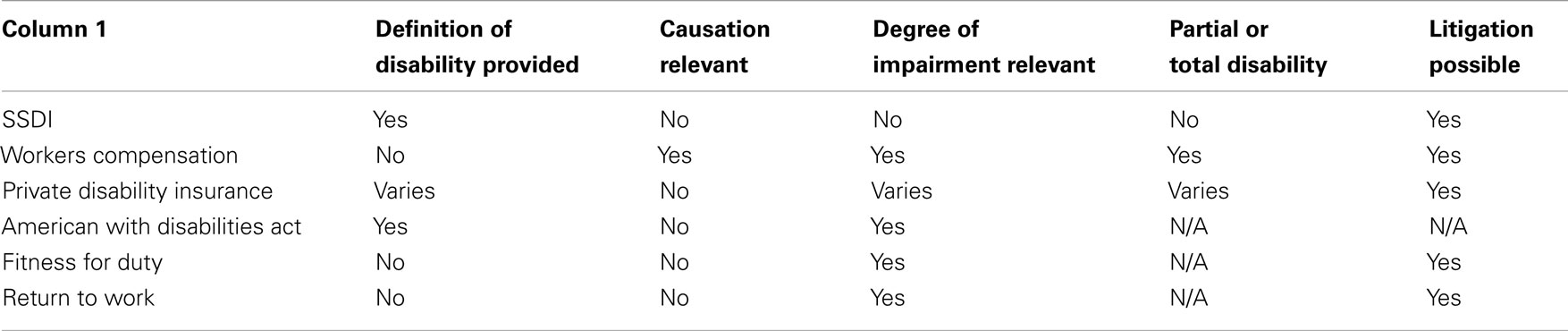

There are many types of disability evaluations including social security, worker compensation, private disability insurance, American with Disabilities Act (ADA), fitness for duty, and return to work. All of them have some similarities and differences, which are summarized in Table 1 (Lisa et al., 2008).

Although a psychiatrist should be aware of all types of disability evaluations individually, our aim is to provide general overview of pertinent common factors involved in performing any evaluation.

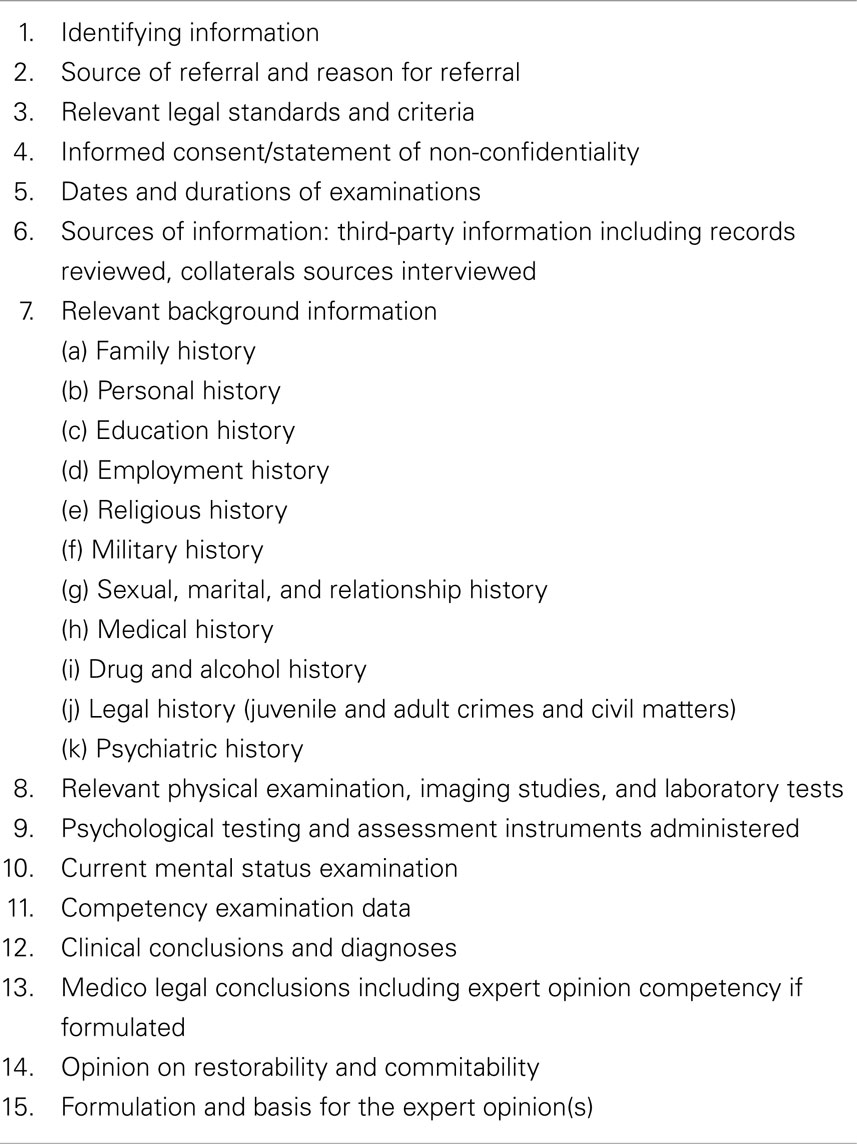

There are certain procedures that need to be taken into consideration in order to conduct a comprehensive psychiatric disability evaluation (see Table 2). A written informed consent stating that evaluation is not for treatment purpose but diagnosing level of impairment or disability should be signed before beginning a standard Psychiatric Examination. A psychiatrist should be aware of the time frame required to file a disability case along with the details of medical and legal events in evaluees life.

It is necessary to clarify the referral source. Collateral information is gathered such as employment records, educational documents, substance abuse profile, and other relevant personal record. Information from third parties including family members and treatment providers may be useful as well. Generally video surveillance is not recommended, as it cannot record internal emotional states. Start interview with open ended questions in order to explore symptoms followed by mental state examination and continues with inquiries to assess specific areas of functioning. The safety of conducting psychiatrist assessments is of prime importance specially if an evaluee is suicidal or homicidal during the disability evaluation.

The next part of the interview should focus on examining the internal consistency of claimants report to correlate requirements of job with his/her impairments. It is important to look for factors related to circumstances outside the work place. This could be done by comparing mood, speech, behavior, and thought processes during the interview to detect malingering and minimize real gain. One clue for psychological gain could be, if the evaluee didn’t show interest in seeking treatment. Additionally when reliability of patient interview and diagnosis is an issue, neuropsychological testing should be performed. For this purpose Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III (WAIS-III) and Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI-2) are sometimes used for conducting cognitive testing in disability evaluations (Melton et al., 2007).

Psychiatrists are often asked to report whether an evaluee’s signs and symptoms limit or restrict a person’s ability to perform occupational functions. It is better to comment on Multiaxial diagnosis, including GAF score and use current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) categories for making Diagnosis. Define impairments in work function; recommend treatment if any and possible course the illness might take.

Psychiatrists are often asked to justify their reports. They should be able to give evidence and support their evaluations based on their judgment, to stand a trial whenever called upon. Americans with Disabilities Act Amendments Act (ADAAA) legislation therefore recommends complete and careful examination even if the evaluee is asymptomatic. The clinician who performs disability evaluation is taken in lieu to the standards of a forensic psychiatrist if questions arise. Having a psychiatric disorder does not automatically denotes impairment or qualifies for a disability.

Honesty is another subjective issue (Appelbaum, 1990, 1997; Griffith, 1998; Shuman and Greenberg, 1998; Candilis et al., 2007) that needs to be addressed, in order to avoid bias. If litigation occurs after evaluation is conducted, then a psychiatrist is not obliged to release information that did not become public in order to avoid legal liabilities (Weinstock and Garrick, 1995; Appelbaum, 2001; Binder, 2002; Gold and Davidson, 2007).

Although no fixed pattern (Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry, 1991; Allnutt and Chaplow, 2000; Silva et al., 2003) has been approved, the report should be prepared according to the format of a standard forensic psychiatric report unless specified. Following AAPL’s guidelines a psychiatrist should be able to perform a well formulated and accurate disability evaluation (Sugarman, 1996). Honest disagreement can be encountered which must be respected. If somehow a psychiatrist is unable to reach a decision and has doubts about certainty, he/she can notify the referral source. Disability decision is an administrative and a legally based process. It does not solely depend on a psychiatrists evaluation report, but is given a prime importance when the court makes a decision. Table 2 (Douglas et al., 2007) summarizes what a typical report should include.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Allnutt, S. H., and Chaplow, D. (2000). General principles of forensic report writing. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 34, 980–987. doi:10.1080/000486700533

American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. (2005). Ethics Guidelines for the Practice of Forensic Psychiatry (Adopted May 1987; Revised October 1989, 1991, 1995, and 2005). Bloomfield, CT: American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV-TR, 4th Edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Andersson, G. B. J., and Cocchiarella, L. (2008). American Medical Association: Guides to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment, 6th Edn. Chicago, IL: AMA Press.

Appelbaum, P. S. (1990). The parable of the forensic psychiatrist: ethics and the problem of doing harm. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 13, 249–259. doi:10.1016/0160-2527(90)90021-T

Appelbaum, P. S. (1997). Ethics in evolution: the incompatibility of clinical and forensic functions. Am. J. Psychiatry 154, 445–446.

Appelbaum, P. S. (2001). Law and psychiatry: liability for forensic evaluations – a word of caution. Psychiatr. Serv. 52, 885–886. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.52.7.885

Baum, K. (2005). Independent medical examinations: an expanding source of physician liability. Ann. Intern. Med. 142, 974–978. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-142-12_Part_1-200506210-00007

Binder, R. (2002). Liability for the psychiatrist expert witness. Am. J. Psychiatry 159, 1819–1825. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.11.1819

Candilis, P. J., Weinstock, R., and Martinez, R. (2007). Forensic Ethics and the Expert Witness. New York: Springer.

Douglas, M., Stephen, G. N., Peter, A., Frierson, R. L., Gerbasi, J., Hackett, M., et al. (2007). AAPL practice guideline for the forensic psychiatric evaluation of competence to stand trial. J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law 35, S3–S72.

Gold, L. H., and Davidson, J. E. (2007). Do you understand your risk? Liability and third party evaluations in civil litigation. J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law 35, 200–210.

Griffith, E. E. H. (1998). Ethics in forensic psychiatry: a cultural response to Stone and Appelbaum. J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law 26, 171–184.

Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry. (1991). The Mental Health Professional and the Legal System. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Lisa, H. G., Stuart, A. A., Albert, M. D., Metzner, J. L., Price, M., Wall, B. W., et al. (2008). AAPL practice guideline for the forensic evaluation of psychiatric disability. J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law 36, S3–S50.

Melton, G. B., Petrila, J., Poythress, N. G., and Norman G. (2007). Psychological Evaluations for the Courts: A Handbook for Mental Health Professionals and Lawyers. New York: Guilford Press.

Shuman, D. W., and Greenberg, S. A. (1998). The role of ethical norms in the admissibility of expert testimony. Judges J. 37, 4–9.

Silva, J. A., Leong, G. B., and Weinstock, R. (2003). “Forensic psychiatric report writing,” in Principles and Practice of Forensic Psychiatry, 2nd Edn, ed. R. Rosner (New York: Oxford University Press), 31–36.

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA), Pub. Law No. 104–191 (1996).

United States Social Security Administration Office of Disability Programs. (2005). Disability Evaluation under Social Security. Available at: http://www.ssa.gov/disability [accessed September 28, 2005].

Weinstock, R., and Garrick, T. (1995). Is liability possible for forensic psychiatrists? Bull. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law 23, 183–193.

Weinstock, R., and Gold, L. H. (2004). “Ethics in forensic psychiatry,” in The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Forensic Psychiatry, eds R. I. Simon and L. H. Gold (Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc), 91–116.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2001). The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Geneva: World Health Organization.

World Health Organization. (2002). Towards a Common Language for Functioning, Disability, and Health. Available at: http://www.who.int/classification/icf [accessed January 13, 2006].

Keywords: disability, impairment, psychiatry residency, independent psychiatric examination, AMA guidelines

Citation: Sohail Z, Bailey RK and Richie WD (2013) How to evaluate disability. Front. Psychiatry 4:54. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00054

Received: 03 February 2013; Accepted: 30 May 2013;

Published online: 14 June 2013.

Edited by:

Shagufta Jabeen, Meharry Medical College, USACopyright: © 2013 Sohail, Bailey and Richie. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in other forums, provided the original authors and source are credited and subject to any copyright notices concerning any third-party graphics etc.

*Correspondence: Zohaib Sohail, Meharry Medical College, 51 Sayreville Blvd S, Sayreville, NJ 08872, USA e-mail:em9oYWliX2RtY0Bob3RtYWlsLmNvbQ==