- 1Hospital for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, LWL University Hospital of the Ruhr-University Bochum, Hamm, Germany

- 2Department of Psychology, Center for Cognitive Neuroscience, University of Salzburg, Salzburg, Austria

A commentary on

Relevance and Definition of Anorexia Nervosa

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is among the most common clinical problems encountered by adolescent girls and young women (1). Incidence rates are highest for females aged 15–19 years as they constitute about 40% of all cases (2). Individuals with AN restrict their food and energy intake significantly, which results in a marked low body weight. Despite the low weight, they see and feel their own body as being fatter than it is and have an intense fear of becoming fat (3). Besides the restriction of food intake, these two core symptoms of body image disturbances are included in the diagnostic criteria in the fifth version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4).

Challenges in the Treatment of Adolescent AN

As therapy outcome seems much more favorable in youth than in adults (5), it is important to optimize treatment strategies within this age group. A variety of treatment options emerged within the last decades, including various specialized in- and outpatient treatments (6). However, despite these efforts and better treatment outcome in adolescents than in adults, long-term treatment success is still unsatisfactory. Although about 50–73% of patients remit, approximately 20–30% remain chronically ill and 9–14% die (5, 7). Inpatient care is required for those in need of intensive treatment, for example, when previous (outpatient) treatment has failed, when there is a rapid decline in weight, or when there are physical conditions that need medical attention (e.g., hemodynamic instability or electrolyte abnormalities) (6). Of those admitted to a hospital, almost 50% of adolescent inpatients need more than one inpatient treatment, 40% of which need three or more (8). Some studies report relapse rates of 85% and more in adolescent patients when reassessed 2–7 years after inpatient treatment (9). In sum, considering the negative impact of hospitalization on the development in adolescence and the risk of chronicity and morbidity, new and effective treatments are urgently needed.

In contrast to AN treatment research in adults, empirical evidence for adolescent treatment is still scarce and mostly of observational nature. Yet, empirical evidence for adolescent treatment has evolved during the last decade. For example, there are some studies, in which family based treatments were compared with treatments focusing on the individual patient. However, as only few studies explored this topic, findings about a superiority of family based interventions over individualized treatments are inconclusive (10–12). Yet, family based treatments may confer better protection against relapse in the long-term (10) and various current practice guidelines recommend them for adolescent AN patients [e.g., Ref. (13)].

In recent years, several innovative treatment approaches have been developed with the aim of solving the problem of low treatment response. Primarily, these include interventions, which have been evaluated in adults and, then, have been adapted to the specific needs of adolescent AN patients. For instance, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), which is a frequently applied transdiagnostic treatment form of eating disorders, including AN (14, 15), emerges as a promising treatment in adolescent AN patients as well. Based on the experiences with non-responding patients, Fairburn broadened the treatment rational of his transdiagnostic approach and established the so-called enhanced cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT-E) for eating disorders (14, 15).

Enhanced Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Adolescent Patients with Anorexia Nervosa

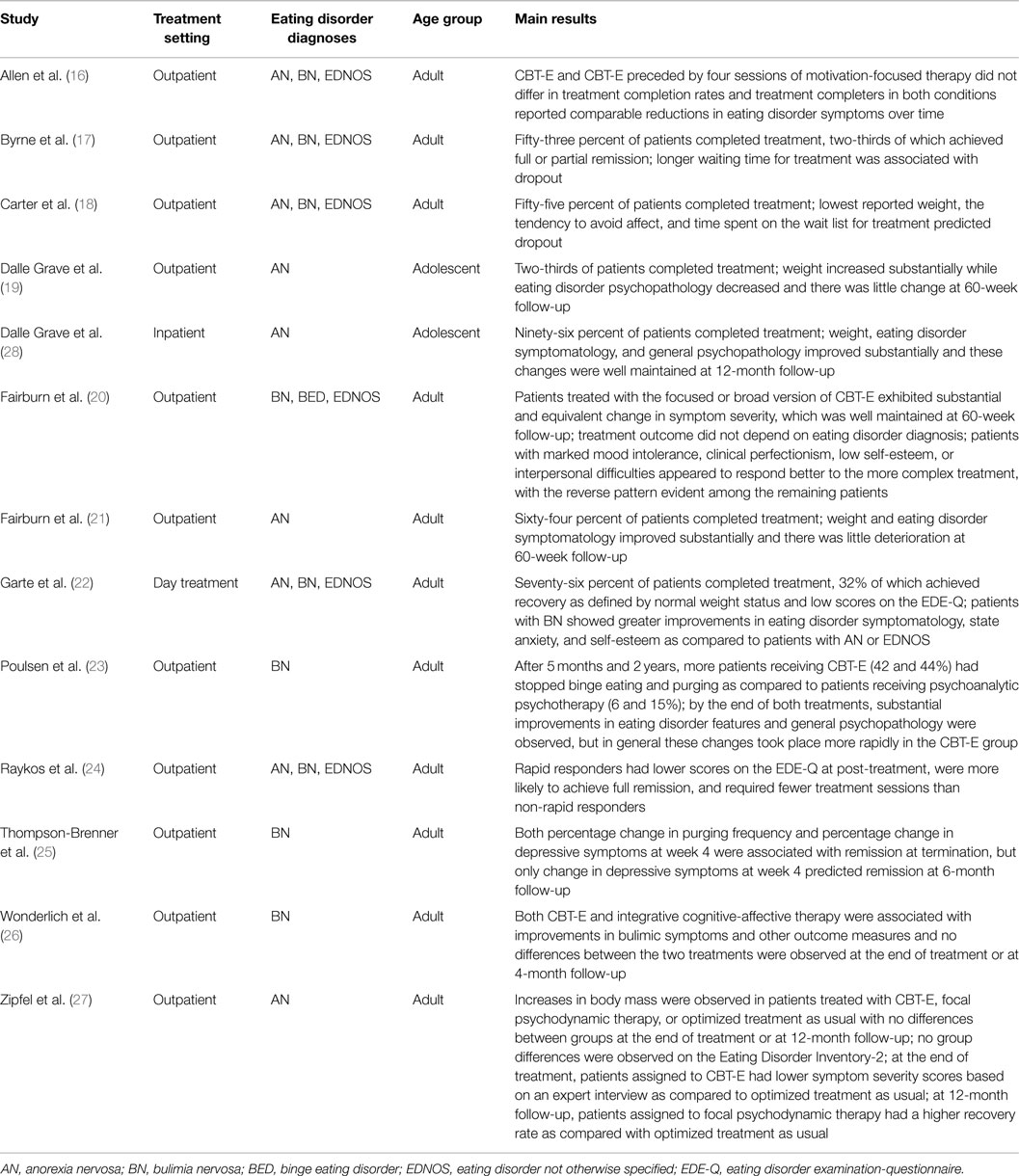

Research about CBT-E in eating disorders is rapidly accumulating in recent years (16–27); yet, most studies involved CBT-E as outpatient treatment in adults (Table 1). In a recent article (28), Dalle Grave and colleagues examined the short- and long-term effects of 20-week adapted CBT-E treatment in adolescent AN inpatients, which is the first study that evaluated a form of CBT-E in this population and treatment setting (Table 1). Although sample size was small (n = 27) and most patients received post-discharge outpatient treatment, this study revealed promising findings about treatment acceptance and long-term efficacy. Ninety-six percent of patients completed inpatient treatment despite its goal of complete weight restoration. Importantly, body mass markedly increased and eating disorder symptomatology markedly decreased in the course of treatment and these changes were maintained at 1-year follow-up. For example, 83% of patients still had normal weight 1 year after treatment (28).

Table 1. Overview of studies involving enhanced cognitive behavior therapy (CBT-E) in eating disorder patients.

However, limitations of this study have to be addressed as well, such as lack of a control group, which would allow evaluating the genuine impact of CBT-E on weight gain and eating disorder pathology. Moreover, an adapted form of CBT-E was used, which included many elements that do not typically form the standard treatment approach. In particular, the structure of an inpatient treatment with its multimodal treatment offers, its long duration (20 weeks), and involvement of parents in the treatment may also contribute to positive long-term treatment outcomes, independent of CBT-E-specific effects. Moreover, during the follow-up period, most patients received outpatient treatment, which probably influenced long-term outcome.

Therefore, future research urgently needs to include a control group and control for additional treatment effects after discharge from the inpatient unit. Moreover, randomization of patients to different treatments seems necessary in order to prevent a selection of highly motivated patients, which may bias outcome interpretation. Notwithstanding these limitations, this study adds to the growing evidence of effectiveness of CBT-E in the treatment of AN and may constitute a basis for and will inspire future research by extending CBT-E to the treatment of adolescent AN patients, which hopefully will improve long-term treatment success in this population.

Conclusion and Future Directions

In recent years, research efforts aiming at optimizing treatment outcome of adolescent AN patients have intensified and proved as fruitful and promising. Besides CBT-E for adolescents in different settings described above, other therapies have been adapted from adult AN patients to juvenile settings as well, for example, cognitive remediation therapy (CRT) (29, 30). Using CRT, improvements in cognitive flexibility could be shown and, in adults, those patients who particularly exhibited low cognitive flexibility prior to treatment showed the largest decreases in eating disorder pathology (31).

Other treatment strategies focus on parents. For example, in an ongoing study, parent-focused treatment is compared with family based treatment strategies (32). Recent research has also compared the effectiveness of different treatment settings: day-patient treatment after short inpatient care proved to be as effective as the more costly continued inpatient treatment (33). Another approach in this line of research is the investigation of home treatment, which is supposed to help overcoming the difficulties that usually arise with the transition from inpatient treatment discharge to the return home (34).

Considering that with the standard treatment, two-thirds of patients can be reached and a considerable number of additional treatment strategies exist, future research should also address the question which patients may profit from which additional treatment form. To date, there are only few studies, in which predictors of treatment success as a function of treatment type were investigated. In a recent review, for example, only one study was identified, in which different treatment types were compared in this regard in adolescents with AN (35). It was found that individuals with higher levels of eating-related obsessionality and eating disorder psychopathology benefited more from family based therapy than individual therapy (36). Other studies on predictors of treatment success, however, focused on adults and/or other eating disorders, treatment types, and outcomes (35). Hence, future research efforts need to generate consistent definitions of treatment outcome, apply multivariate predictor models and differentiate between specific eating disorder diagnoses and treatment types, such as family based interventions versus CBT-E. Identifying characteristics of patients who may benefit more from one treatment form or the other would help to better individualize treatment strategies and may prevent hospitalization.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

AM is supported by a grant of the European Research Council (ERC-StG-2014 639445 NewEat).

References

1. Thompson JK, Smolak L. Body Image, Eating Disorders, and Obesity in Youth: Assessment, Prevention, and Treatment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association (2001).

2. Smink FR, van Hoeken D, Hoek HW. Epidemiology of eating disorders: incidence, prevalence and mortality rates. Curr Psychiatry Rep (2012) 14:406–14. doi:10.1007/s11920-012-0282-y

3. Cash TF, Deagle EA III. The nature and extent of body-image disturbances in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: a meta-analysis. Int J Eat Disord (1997) 22:107–25. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199709)22:2<107::AID-EAT1>3.3.CO;2-Y

4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association (2013).

5. Steinhausen HC. The outcome of anorexia nervosa in the 20th century. Am J Psychiatry (2002) 159:1284–93. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.8.1284

6. Espie J, Eisler I. Focus on anorexia nerosa: modern psychological treatment and guidelines for the adolescent patient. Adolesc Health Med Ther (2015) 6:9–16. doi:10.2147/AHMT.S70300

7. Löwe B, Zipfel S, Buchholz C, Dupont Y, Reas DL, Herzog W. Long-term outcome of anorexia nervosa in a prospective 21-year follow-up study. Psychol Med (2001) 31:881–90. doi:10.1017/S003329170100407X

8. Steinhausen HC, Grigoroiu-Serbanescu M, Boyadjieva S, Neumarker KJ, Metzke CW. The relevance of body weight in the medium-term to long-term course of adolescent anorexia nervosa. Findings from a multisite study. Int J Eat Disord (2009) 42:19–25. doi:10.1002/eat.20577

9. Gowers SG, Weetman J, Shore A, Hossain F, Elvins R. Impact of hospitalisation on the outcome of adolescent anorexia nervosa. Br J Psychiatrt (2000) 176:138–41. doi:10.1192/bjp.176.2.138

10. Lock J, Le Grange D, Agras WS, Moye A, Bryson SW, Jo B. Randomized clinical trial comparing family-based treatment with adolescent-focused individual therapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry (2010) 67:1025–32. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.128

11. Accurso EC, Ciao AC, Fitzsimmons-Craft EE, Lock JD, Le Grange D. Is weight gain really a catalyst for broader recovery?: the impact of weight gain on psychological symptoms in the treatment of adolescent anorexia nervosa. Behav Res Ther (2014) 56:1–6. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2014.02.006

12. Watson HJ, Bulik CM. Update on the treatment of anorexia nervosa: review of clinical trials, practice guidelines and emerging interventions. Psychol Med (2013) 43:2477–500. doi:10.1017/S0033291712002620

13. Wilson GT, Shafran R. Eating disorders guidelines from NICE. Lancet (2005) 365:79–81. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17669-1

14. Cooper Z, Fairburn CG. The evolution of “enhanced” cognitive behavior therapy for eating disorders: learning from treatment nonresponse. Cogn Behav Pract (2011) 18:394–402. doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2010.07.007

15. Fairburn CG. Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders. New York, NY: Guilford Press (2008).

16. Allen KL, Fursland A, Raykos B, Steele A, Watson H, Byrne SM. Motivation-focused treatment for eating disorders: a sequential trial of enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy with and without preceding motivation-focused therapy. Eur Eat Disord Rev (2012) 20:232–9. doi:10.1002/erv.1131

17. Byrne SM, Fursland A, Allen KL, Watson H. The effectiveness of enhanced cognitive behavioural therapy for eating disorders: an open trial. Behav Res Ther (2011) 49:219–26. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2011.01.006

18. Carter O, Pannekoek L, Fursland A, Allen KL, Lampard AM, Byrne SM. Increased wait-list time predicts dropout from outpatient enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT-E) for eating disorders. Behav Res Ther (2012) 50:487–92. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2012.03.003

19. Dalle Grave R, Calugi S, Doll HA, Fairburn CG. Enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: an alternative to family therapy? Behav Res Ther (2013) 51:R9–12. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2012.09.008

20. Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Doll HA, O’Connor ME, Bohn K, Hawker DM, et al. Transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with eating disorders: a two-site trial with 60-week follow-up. Am J Psychiatry (2009) 166:311–9. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08040608

21. Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Doll HA, O’Connor ME, Palmer RL, Grave RD. Enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy for adults with anorexia nervosa: a UK-Italy study. Behav Res Ther (2013) 51:R2–8. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2012.09.010

22. Garte M, Hagen B, Reas DL, Isdahl PJ, Hinderaker E, Rø Ø. Implementation of a day hospital treatment programme based on CBT-E for severe eating disorders in adults: an open trial. Adv Eat Disord (2015) 3:48–62. doi:10.1080/21662630.2014.958510

23. Poulsen S, Lunn S, Daniel SIF, Folke S, Mathiesen BB, Katznelson H, et al. A randomized controlled trial of psychoanalytic psychotherapy or cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry (2014) 171:109–16. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12121511

24. Raykos BC, Watson HJ, Fursland A, Byrne SM, Nathan P. Prognostic value of rapid response to enhanced cognitive behavioral therapy in a routine clinic sample of eating disorder outpatients. Int J Eat Disord (2013) 46:764–70. doi:10.1002/eat.22169

25. Thompson-Brenner H, Shingleton RM, Sauer-Zavala S, Richards LK, Pratt EM. Multiple measures of rapid response as predictors of remission in cognitive behavior therapy for bulimia nervosa. Behav Res Ther (2015) 64:9–14. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2014.11.004

26. Wonderlich SA, Peterson CB, Crosby RD, Smith TL, Klein MH, Mitchell JE, et al. A randomized controlled comparison of integrative cognitive-affective therapy (ICAT) and enhanced cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT-E) for bulimia nervosa. Psychol Med (2014) 44:543–53. doi:10.1017/S0033291713001098

27. Zipfel S, Wild B, Groß G, Friederich H-C, Teufel M, Schellberg D, et al. Focal psychodynamic therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, and optimised treatment as usual in outpatients with anorexia nervosa (ANTOP study): randomised controlled trial. Lancet (2014) 383(9912):127–37. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61746-8

28. Dalle Grave R, Calugi S, El Ghoch M, Conti M, Fairburn CG. Inpatient cognitive behavior therapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: immediate and longer-term effects. Front Psychiatry (2014) 5:14. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00014

29. Pretorius N, Dimmer M, Power E, Eisler I, Simic M, Tchanturia K. Evaluation of a cognitive remediation therapy group for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: pilot study. Eur Eat Disord Rev (2012) 20:321–5. doi:10.1002/erv.2176

30. Dahlgren CL, Lask B, Landrø N-I, Rø Ø. Developing and evaluating cognitive remediation therapy (CRT) for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: a feasibility study. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry (2014) 19:476–87. doi:10.1177/1359104513489980

31. Dingemans AE, Danner UN, Donker JM, Aardoom JJ, van Meer F, Tobias K, et al. The effectiveness of cognitive remediation therapy in patients with a severe or enduring eating disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom (2014) 83:29–36. doi:10.1159/000355240

32. Hughes EK, Le Grange D, Court A, Yeo MS, Campbell S, Allan E, et al. Parent-focused treatment for adolescent anorexia nervosa: a study protocol of a randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry (2014) 14:105. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-14-105

33. Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Schwarte R, Krei M, Egberts K, Warnke A, Wewetzer C, et al. Day-patient treatment after short inpatient care versus continued inpatient treatment in adolescents with anorexia nervosa (ANDI): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet (2014) 383:1222–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62411-3

34. Herpertz-Dahlmann B. [New aspects in the treatment of adolescent anorexia nervosa]. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol (2015) 65:17–9. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1394402

35. Vall E, Wade TD. Predictors of treatment outcome in individuals with eating disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Eat Disord (2015). doi:10.1002/eat.22411

Keywords: enhanced cognitive behavior therapy, anorexia nervosa, eating disorders, treatment

Citation: Legenbauer TM and Meule A (2015) Challenges in the treatment of adolescent anorexia nervosa – is enhanced cognitive behavior therapy the answer? Front. Psychiatry 6:148. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00148

Received: 20 April 2015; Accepted: 02 October 2015;

Published: 14 October 2015

Edited by:

Alix Timko, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, USAReviewed by:

Alison Darcy, Stanford University School of Medicine, USACopyright: © 2015 Legenbauer and Meule. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tanja M. Legenbauer, dGFuamEubGVnZW5iYXVlckBydWIuZGU=

Tanja M. Legenbauer

Tanja M. Legenbauer Adrian Meule

Adrian Meule