- 1Medical Faculty, Universidad San Sebastián, Puerto Montt, Chile

- 2Medical Faculty, Universidad Diego Portales, Santiago, Chile

- 3Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Charité Campus Mitte, Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany

- 4Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Hospital Clínico Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile

- 5Department of Psychology, Universidad del Humanismo Cristiano, Santiago, Chile

- 6Corporación de Artistas por la Rehabilitación y Reinserción Social a través del Arte CoArtRe, Santiago, Chile

- 7Department of Drama, Queen Mary University of London, London, United Kingdom

Introduction: Innovative and interdisciplinary approaches are needed to improve mental health and psychosocial outcomes of people with criminal justice involvement and their families. Aim of the study was to assess effects of the participation in a theatre project on the mental health problems of people with criminal justice involvement and relatives.

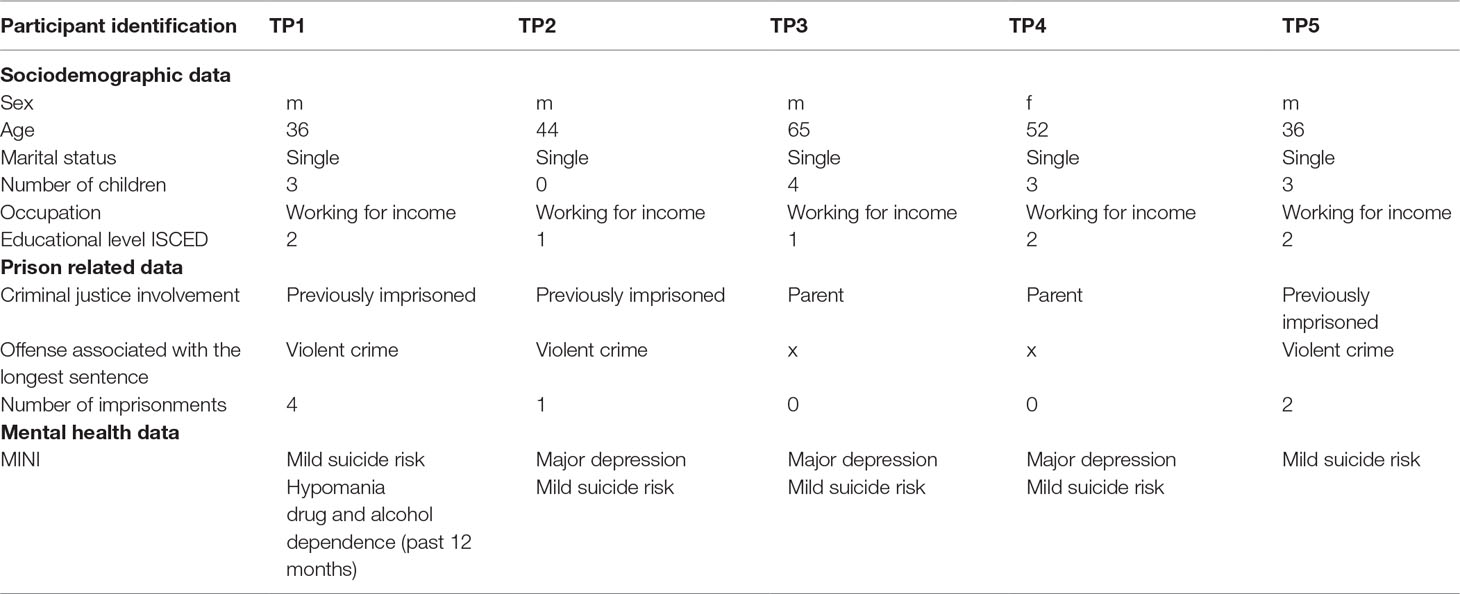

Methods: We conducted structured diagnostic interviews and in-depth qualitative interviews with five participants performing Shakespeare’s Richard III in Chile. Three participants had been imprisoned prior to the project, and two were the parents of a person who died in a prison fire. Qualitative interviews followed a topic guide. Data were transcribed, and a six-phase approach for thematic analysis of the data was used.

Results: Substance use disorder or major depression was identified in all the participants. Participation in the theatre project was experienced by the respondents as having a positive effect on the mental health conditions. The research registered the positive experiences of role identification, emotional expression, commitment with group processes, improved skills to socially interact, to be heard by the general public and society, and positive perceptions of the audience (including relatives).

Discussion: The study raises the possibility that there may be improvements of depression and substance use problems through the participation of people with criminal justice involvement in a drama project. Wider scale research is recommended on the possible effects. The approach may be an alternative to psychotherapy and medication for some individuals.

Introduction

Prison populations have grown worldwide in the past 15 years (1). In South America, the increase of prison population rates has been especially pronounced (1) and related to a decrease in psychiatric bed numbers (2). There has been concern about high rates of mental health problems (3, 4) and substance use disorders (5, 6) in prison populations (7). Improvements of mental health care and psychosocial outcomes of prison populations are considered a global public health challenge. Innovative and interdisciplinary approaches are needed.

Therapeutic effects of theatre have been described since Aristotle first outlined his theory of catharsis (8–12). Specific drama-based therapeutic approaches based on performance include Moreno’s “Psychodrama,” Augusto Boal’s “Theatre of the Oppressed,” and “Rainbow of Desire” and drama therapy (13–16). Psychodrama allows participants to enact scenes from the past, present or future, and imagined or real, as if they were occurring at the moment in a safe therapeutic environment (15). Boal’s experiments aimed to overcome oppression initiating political change and overthrowing internalized oppression through a dialectic process involving “spect-actors” (13, 14). Drama therapy encourage activities that create a dramatic reality through engagement with embodiment, projection, and roleplay (12). In all the above methodologies, drama is seen to address psychological and social needs such as self-expression, identity, freedom (of imagination), creativity, and community (17).

Art as a vehicle to change behavioral patterns of those making it has been increasingly used in correctional institutions. In qualitative case studies as well as in quantitative evaluations of art projects, it has been shown that art can engage prisoners in transforming aspects of their lives (17, 18). Positive effects on the personalities of imprisoned people and cost-benefits for societies have been described (19, 20, 17, 18). Lower rates of recidivism, the development of coping strategies, and social responsibility as well as the decrease of anger levels have been identified as a result of art programs in prisons (21–24). The unlocking of creative potentials in prisons has been described to have potential for the long-term rehabilitation of participants in music programs (25). Drama-based therapeutic techniques may be more effective than verbal therapies in evoking emotional states and allow more healthy self-reflection in forensic clients with personality disorders (26). Participating in drama seems to improve the skills of people to maintain positive relationships with others. Participants may establish trust and respectful relationships within the group and mutual commitments to a common task. There may be a possibility to challenge negative narrative identities of people with criminal justice involvement. The sense of usefulness and belonging could help in the formation of a pro-social identity (27).

Testimony therapy is a psychotherapeutic method that originated in South America (28). This psychotherapeutic technique of narrating and writing testimonies was used to integrate traumatic experiences of former prisoners, survivors of the military dictatorship in Chile. Narrative exposure therapy is one of the most established trauma-focused psychotherapies, and it was derived from this approach (29, 30). Expression through acting in drama could help to integrate traumatic experiences of people with experience of incarceration and their families (4).

There is further need to understand processes and mechanisms of change related to the participation of people with experience of incarceration and their families in drama projects. The aim of this exploratory study was to assess subjective effects of participating in a drama project on mental health problems and on interpersonal and social functioning in former prisoners. The study also included an assessment of people who have been involved tangentially with the penal system through including the parents of a prisoner who died in a prison fire.

Methods

The Theatre Production

CoArtRe (Corporación de Artistas por la Rehabilitación y Reinserción Social a través del Arte) is a nonprofit organization founded in 1998 that realizes theatre projects in criminal justice contexts in Chile. The organization has artistic and social aims (31). Those include translating testimonies of incarcerated individuals in theatre productions and promoting social inclusion and mobility through artistic experiences. Former prison inmates, the parents of a prisoner who had died in prison and professional actors, participated in the production of Richard III by Shakespeare. Rehearsals took place four times a week between November 2015 and March 2016. The production premiered in March 2016 in Santiago de Chile (Teatro, Centro Cultural Gabriela Mistral, Chile).

Shakespeare and Imprisonment

“To hold as ‘twere the mirror up to nature: to show virtue her feature, scorn her own image, and the very age and body of the time his form and pressure” (32). Shakespeare gave these words to Hamlet as he instructed the actors who were taking part in his experimental performance to “catch the conscience” of the King. The London Shakespeare Workout describes Shakespeare’s language as offering an opportunity to change by providing “confidence through the will to dream” (33). The roles in Shakespeare’s plays offer possibilities of identification for people with criminal justice involvement and those affected by imprisonment. Shakespeare’s work is comprised of topics such as crime, factional allegiances, violence, revenge, love, desire, and hatred. His complex characters and their actions have proved themselves resilient across four centuries and continue to connect to different cultures, contexts, and lives today. While the historical distance of these texts and their characters can defuse the issues, questions, and uncertainties they raise, new contexts in which they are expressed (e.g., in relation to the experience of incarceration) can bring new effects, affects, and implications. Working with Shakespeare’s texts can help people get affected by imprisonment to reflect personal choices and to think critically (34, 35). Shakespeare’s work has a special place in prison theatre (36, 37). Combining marginalized prison contexts and allowing performers to bring their biographies and personalities to classical dramaturgic texts through the performance of Shakespeare brings a particular experience of authenticity for the spectators (38).

Richard III by Shakespeare

Richard III (c.1593) is one of Shakespeare’s most intriguing works. The protagonist has a complicated character. His sinister character depicts cruelty, while his hunger for power acts as the driving force (39). Richard’s seductive yet ruthless manipulations combine with criminal acts of extreme violence to secure the throne for himself, without respect for family, social norms, or the limits of the law. Yet, at the end of the play, Shakespeare gives us a glimpse of human vulnerability within all the extravagant monstrosities as Richard is haunted by his victims’ spirits, his own nightmares, and an emerging, fearful conscience:

My conscience hath a thousand several tongues,

And every tongue brings in a several tale,

And every tale condemns me for a villain (40)

Perhaps we might say that Richard is a prisoner of his own desires and becomes a victim of the web of intrigues and crimes he himself weaves.

Sample and Procedures

In order to cast his production of Richard III, JR recruited professional actors and participants with different levels of experience of the Chilean penal system. The five non-professional participants had previously participated in a documentary prison theatre production by CoArtRe that focused on a prison fire which took place when three of them were still held in the penal system of Santiago de Chile. By the time of casting for Richard III, those three participants had been released and were in the process of psychosocial rehabilitation. They had large roles including the title role. The other two were family members of a prison inmate who had died in the prison fire. Furthermore, professional actors were recruited to perform the remaining roles and included in the crew at later stages of the rehearsals.

Participants were approached for interviews during rehearsal. Qualitative interviews were held in private areas upon written informed consent of the participants. Data were audiotaped and transcribed eliminating information that would allow personal identification. The data were collected between March and June 2016. The research ethics review board of the Universidad San Sebastián, Chile, approved the study.

We conducted structured diagnostic interviews and qualitative interviews with five participants of the theatre project. The interviews were held during the rehearsals and after performing in the play. In total, eight in-depth interviews were audio-recorded (five during rehearsals before the performances, three after performances of the play), subsequently transcribed, and included in the analysis.

Instruments

The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) in Spanish was used to assess mental disorders and substance use disorders. The MINI is a fully structured diagnostic interview (41) that has been used in epidemiological research to establish the prevalence of mental disorders in prison populations in Chile (42). It classifies mental disorders according to the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10). Qualitative interviews were guided through topics relating to expectations with respect to the participation and experiences of the participation. Particular areas covered included: positive/negative effects, social interactions (with other participants), emotions (during participation), perception of rehabilitation (effects of participating), work (effect on personal development), family, and mental health (possible changes in health and mental health).

Analyses

Mental health and substance use disorders of the participants were described.

Qualitative data were analyzed by CS and CG using an approach consisting of six phases: familiarization, initial coding, searching for themes, reviewing themes, definition of themes, and reporting (43). Interviews were analyzed using an inductive thematic analysis procedure (44, 45). Coding was conducted manually by two researchers CG and CS. Disagreements were resolved in discussion with a third researcher APM. NVivo software was used for the initial quantitative content analysis identifying the most used words.

Results

Characteristics of the Sample

Participants were between 36 and 65 years old. Participants with direct experience of criminal justice involvement had served sentences for violent crimes. The structured clinical interviews of the five participants revealed one participant with current illicit drug dependence (former inmate) and three with major depression (one former inmate and the parents of an inmate who died in a prison fire). All had mild suicide risk related to previous suicide attempts (Table 1).

Coding of the Qualitative Data

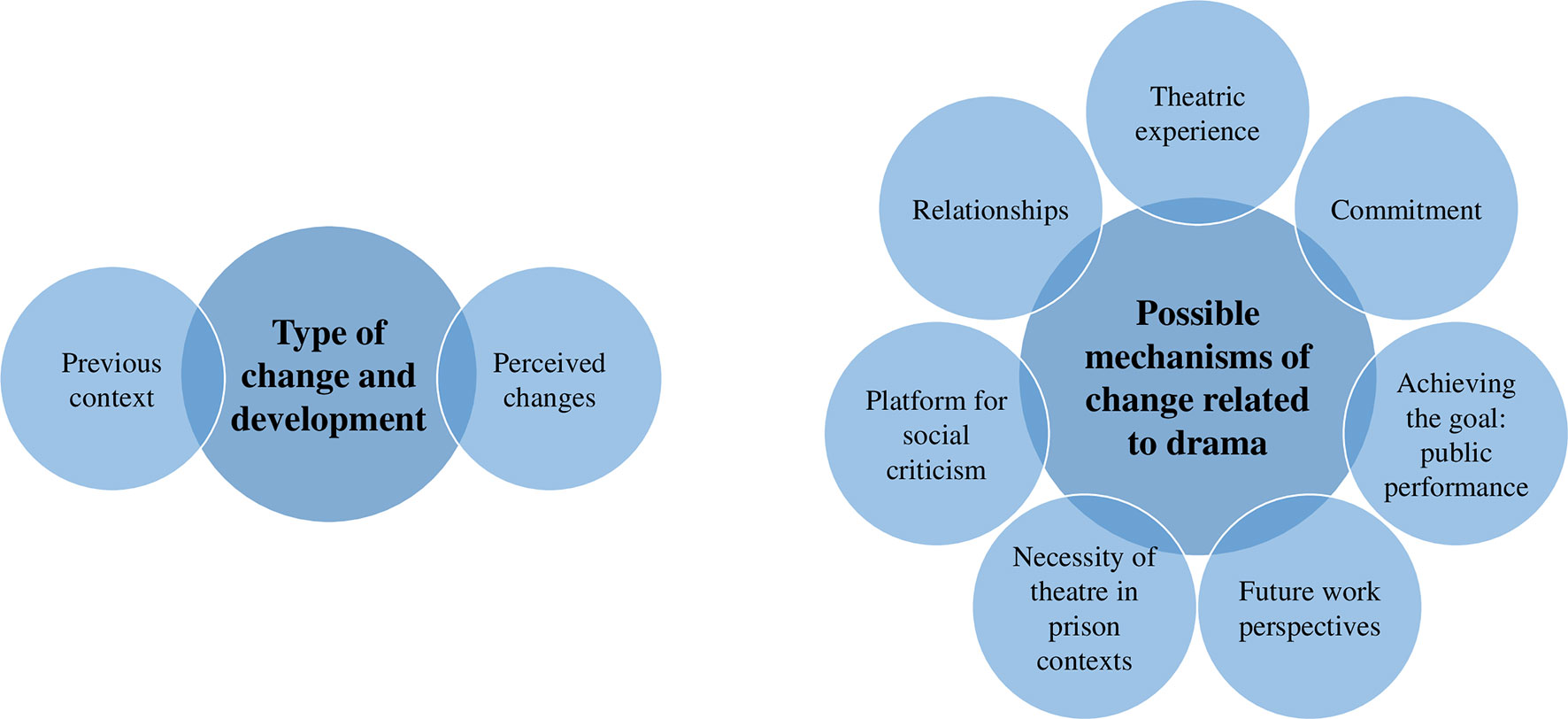

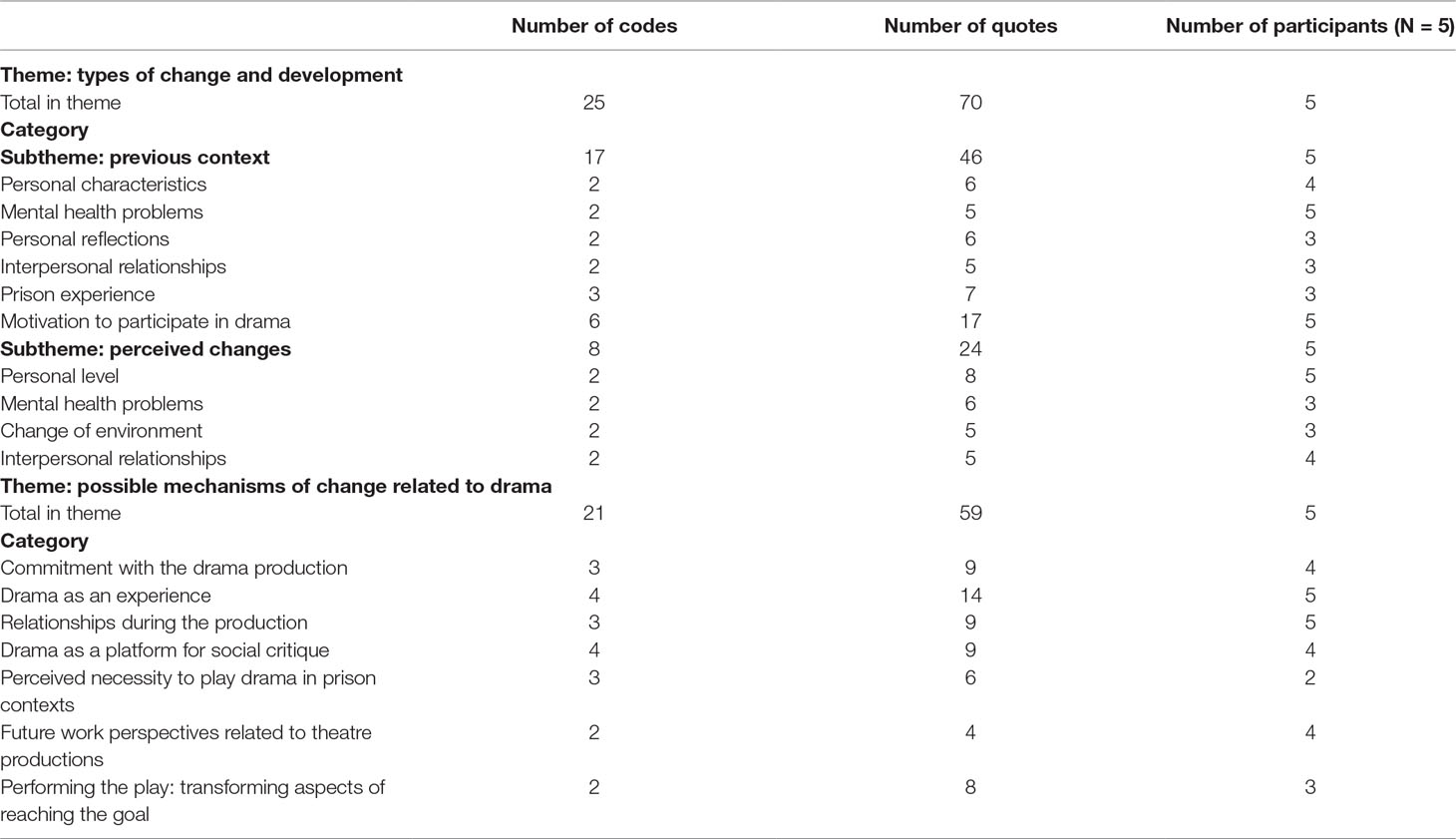

The most used words in the interviews served as a first orientation prior to manual coding. The five most used words were theatre (n = 181), play (n = 99), people (n = 55), prisoner (Spanish: preso) (n = 54), appearing in all eight interviews, and prison (Spanish: carcel) (n = 45) appearing in six interviews. Inductive analysis resulted in 46 initial codes, which were grouped into 17 categories and two main themes and are reported in Table 2.

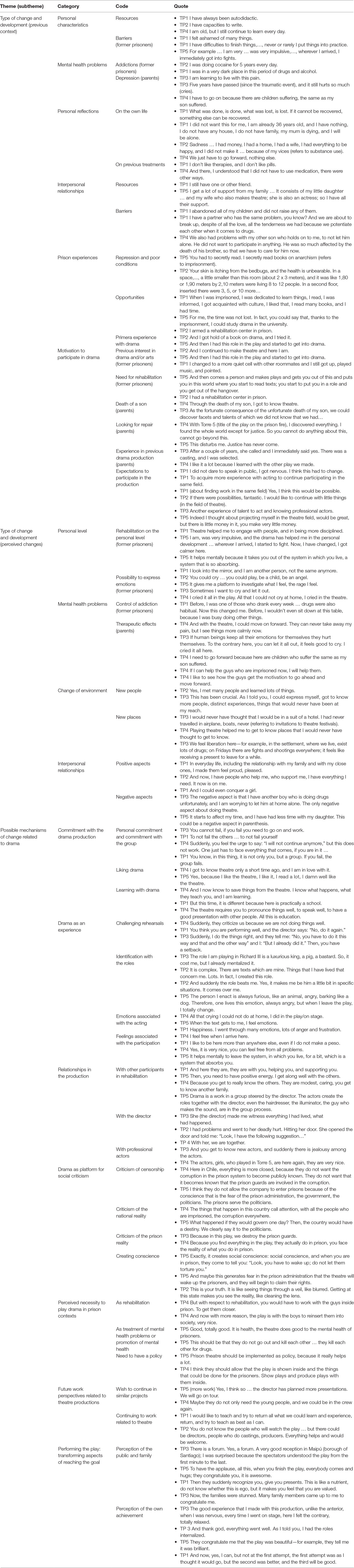

Figure 1 shows the two main themes, two subthemes for the first main theme, and seven categories for the second main theme.

Figure 1 Type of change and possible mechanisms of change in individuals involved with the criminal justice system participating in a drama project.

Types of Change and Development

This first theme includes the types of changes the participants perceived over the course of the intervention/participation in the theatre project. It includes descriptions of the previous context relating to mental health and substance use problems (personal characteristics, problems regulating interpersonal relationships, previous experiences in prison, traumatic experiences) and the perceived changes (with respect to mental health, substance use, social environment, affectivity, and personality).

Assessing the previous context, participants revealed personal characteristics that related to their mental health problems.

TP5: “For example … I am very … was very impulsive … wherever I arrived, I immediately got into fights”

When participants revealed previous states of mental health, the data were dominated by “substance abuse and addiction” especially for the former inmates.

TP1: I was in a very bad place in this period of drugs, alcohol”

The parents of the inmate who died in a prison fire participants expressed during the interviews emotions related to trauma and depression.

TP3: “Five years have passed and it still hurts so much (crying)”

All former inmates revealed negative experiences with prison life, perceived repression, and suffered the poor housing conditions in prison.

“TP2: “Your skin is itching from the bedbugs and unbearably unhealthy. In a space … a little smaller than this room (about 2 x 3 meters) and it was like 1,80 or 1,90 meters by 2,10 meters were living 8 to 12 people. In a second floor inserted there were 3, 5 or 10 more…”

The former inmates revealed emotions related to deprivation and the loss of relationships and material goods due to the substance use problems and imprisonment.

“TP2: Sadness … I had money, I had a home, I had a wife, I had everything to be happy and I did not make it … because of my vices (refers to substance use).”

The former inmates described their social context and interpersonal relations as obstacles for overcoming mental health issues.

“TP1: I have a partner that has the same problem, you know? And we are about to break up, despite of all the love, all the tenderness we had because we potentiate each other when it comes to drugs”

They described that mental health problems and substance use problems improved with participation in the project.

“TP1: Before, I was one of those who drank every week … drugs were also habitual. Now this changed me. Before, I wouldn’t even sit down at this table because I was busy doing other things”

“TP4: And with the theatre I could move on forward. They can never take away my pain, but I see things more calmly now”

Possible Mechanisms of Change

The second theme describes possible mechanisms that underlie changes produced through the participation in theatre.

There was the possibility to express and reflect emotions related to traumatic experience.

“TP4: All that crying, I could not do at home, I did in the play/on stage”

The participants identified with the role and created new personal narratives.

“TP2: It is complex. There are texts which are mine. Things that I have lived, that concern me. Lots. In fact, I have created this role.”

The participation may have produced changes of self-perception affecting their identity:

“TP1: I look into the mirror and I am another person, not the same anymore.”

The positive reception of the play by the audience and their families was rewarding and changed the participants’ self-image. Participants expressed the experience of a personal success.

“TP5: They congratulate me, that the play was beautiful, for example, they tell me it was brilliant”

The change of the social environment was a recurrent theme. Participation in the theatre company meant the opportunity to meet new people and see new places.

“TP3: This has been crucial. As I told you, I could express myself, got to know more people, distinct experiences, things that would never have been at my reach.”

Changes in interpersonal relationships were described as positive.

“TP1: In everyday life, including the relationship with my family and with my close ones, I made them feel proud, pleased”

The group of former inmates emphasized the possibility to engage with people and to acquire new skills.

“TP1: Theatre helped me to engage with people, and in being more disciplined”

A crucial point for all was the commitment with the group to achieve the common goal of the project, to put the play on stage. The interpersonal relationships were perceived as resources during the participation in the theatre project.

“TP5: I get a lot of support from my family … It consists of my little daughter … and my wife who also plays theatre; she is also an actress; so I have all their support”

The relationships with the professional actors and the director played an important role for the participants going as far as referring to them as “family.” All participants had in common that they expected future activities or even remunerated jobs in theatre beyond the participation in the current project. Given that most of the participants had previously participated in a prison theatre project that had been successful with a series of invitations to international festivals, the aspiration did not seem to be completely impossible, but unrealistic.

Participants also described theatre as a platform for social criticism that would not be heard elsewhere. The play reached general public interested in experimental and alternative theatre. It was also discussed in the media. The opportunity to criticize authorities, police, censorship, and politics in front of a public outside, and beyond their usual social environment generated a feeling of satisfaction. Shakespeare seemed to be a safe mechanism to serve this purpose through his cultural power but historical distance. Theatre was described as a way of generating more awareness about imprisonment, inside and outside prison. Participants expressed the idea that more theatres inside the prisons would be useful for rehabilitation, social reinsertion, and improvements of mental health.

“TP5: Exactly, social awareness is generated: A social awareness and when you are a prisoner it tells you ‘Look, you have to wake up, don’t let the guards torture you.’”

For two of the former inmates as well as the mother of the inmate who died in the prison fire, the artistic work was a vehicle of change superior to psychotherapeutic treatments and medication. They reflected on their past contacts with psychiatrists, therapists, and treatments that had not been useful to them.

“TP1: I don’t like therapies and I don’t like pills”

Quantitative Content Analysis

The number of appearance of quotes and codes per category and theme, and by how many participants each category and theme was brought up, are reported in Table 3.

Table 3 Quantitative content analysis indicating the number of codes and number of quotes per category and theme, and by how many participants each category, and theme was brought up.

Discussion

Main Findings

Participation in theatre projects may subjectively change emotional states related to traumatic experiences and improve capacities to regulate interpersonal relationships in people with criminal justice involvement. The possible mechanisms include commitments with the group and with performing the work, expression of emotions, and traumatic experiences, being heard in public and positive perception by others. New skills and artistic success may open up personal perspectives and future projections.

Strengths and Limitations

This was an innovative collaboration between professionals in drama with backgrounds in academia and in practice working together with professionals in mental health with backgrounds in psychology and in psychiatry to address research questions relating to drama interventions in a Latin American context. The participants had a similar socio-economic background that allows focusing on the effects of theatre on mental health and psychosocial functioning.

The study also had several limitations: the number of participants was small. The group of participants was heterogeneous. There were former inmates and the parents of an inmate who died in a prison fire. Participants had different types of traumatic experiences and criminal justice involvement. Not all the participants were available for a second interview after the performances. The small number of participants may not have yielded saturation of the themes and topics identified in the study. The results may have been influenced by the selection of participants with positive previous experiences of performing drama.

Comparison With the Literature

There are two different aspects of using arts as therapeutic vehicles: 1) in the context of art therapies that focus on the rehabilitation process in workshops or rehearsals and 2) doing art with a focus on the artistic product that is exhibited or performed to communicate with the public, society, and the contemporary art scene.

The approach used in this study involves both aspects, which is potentially powerful. It stands in a South American landscape that includes such figures as Brazilian psychiatrist Nise da Silveira (46) who used arts as an access to the unconscious in psychotherapies and also focused on the artistic product facilitating success of several artists with mental health problems in the contemporary art scene. Beyond using arts in therapies, Silveira converted parts of a psychiatric hospital into an open creative laboratory that was used by patients and attracted the interest of critics, artists, and the general public intrigued and inspired by the art of the mentally ill. The hospital in Rio de Janeiro where she worked from the 1940s through to the 1990s now hosts the Museum of Images of the Unconscious which houses one of the world’s most important art collections produced by patients with mental illnesses. Formerly known as the Pedro II Psychiatric Centre, it has been renamed as the Nise da Silveira Municipal Institute.

Participating in theatre may improve personal development and rehabilitation of people with criminal justice involvement (47). In the treatment of traumatic stress, performing theatre was shown to lead to more self-awareness and positive psychological transformation (48). Elements of testimonial theatre or Boal’s concept of forum theatre encourage a simultaneous dramaturgy between actors and spectators. This was later refined to create a methodology Boal referred to as The Rainbow of Desire whereby participants introduce narratives of their personal lives and experiences in performing and understanding their own behaviors (13, 14). Drama therapy has been shown to enhance alternative behavioral choices that are crucial for achieving abstinence in the treatment of substance use disorders (49, 50). Performing Richard III implies identification with the roles and provides the opportunity to express traumatic experiences such as exposure to violence, which is common in prisoners (51). The performance of a role and the use of Shakespeare’s language allow the participants to communicate in ways that are different from their habitual form of interaction (33, 52).

All participants felt that they expressed social criticism by performing theatre, which is a crucial element of testimony therapy (28). Several participants of this study expressed the necessity of implementing theatre inside prisons not only to create social awareness inside prisons but also to communicate through this medium with a wider public. They experienced the possibility to criticize social inequalities, prison life, and the feeling of repression from police, politics, and authorities. In a previous theatrical production documenting a prison fire—in which most of the actors had performed, and several of the participants had lost family members—the criticism of the authorities had been more direct. They experienced opportunities to create awareness in society for the problems of marginalized communities and especially prison inmates. The role of theatre in prisons has been described as a social process Staging Human Rights (53). Prison theatre may be less effective when it merely focuses on the process of rehearsals (54). This study revealed that being heard and appreciated in public led to the experience of social inclusion and empowerment as possible mechanisms of mental health improvements in the participants. In the success of putting the play on stage, this individual and collective accomplishment contributes to positive emotions (55). Public success of performing prison theatre enables the actors to visualize an alternative self and gain motivation for their future (56).

Conclusions

The participation in theatre productions seems to subjectively initiate change regarding the regulation of emotions and interpersonal relationships in people with criminal justice involvement. The mechanisms may go beyond and complement those of individual psychotherapies and medications. They include identification with roles, artistic expression, commitment with group processes, communication with the public, and social criticism. Wider scale research can be recommended on the type and size of these effects in larger and more homogeneous samples of participants. Contact procedures for follow-ups should be improved to reduce attrition in future research.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding authors.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of “research ethics review board of the Universidad San Sebastián, Chile” with written informed consent from all subjects. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the “research ethics review board of the Universidad San Sebastián, Chile.”

Author Contributions

AM, JR, and PH contributed to the conception and design of the study. AM, PM, and CG collected the data. CG and CS performed the qualitative data analysis. AM and CG wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript, and approved the submitted version. AM supervised the study.

Funding

The study was supported by funding of the Universidad San Sebastián, Chile and by a bridging fund for exploring interdisciplinary collaborations in life sciences of the Wellcome Trust, UK. APM receives funding of the CONICYT, grant scheme FONDECYT Regular 1190613. We acknowledge support from the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the Open Access Publication Fund of Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Walmsley R. World prison population list (twelfth edition). London: Institute for Criminal Policy Research (2018). Available: http://www.prisonstudies.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/wppl_12.pdf [Accessed 12.07.2019].

2. Mundt AP, Chow WS, Arduino M, Barrionuevo H, Fritsch R, Girala N, et al. Psychiatric hospital beds and prison populations in South America since 1990: does the Penrose hypothesis apply? JAMA Psychiatry (2015) 72:112–8. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2433

3. Fazel S, Seewald K. Severe mental illness in 33 588 prisoners worldwide: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Br J Psychiatry (2012) 200:364–73. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.096370

4. Baranyi G, Cassidy M, Fazel S, Priebe S, Mundt AP. Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in prisoners. Epidemiol Rev (2018) 40:134–45. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxx015

5. Fazel S, Bains P, Doll H. Substance abuse and dependence in prisoners: a systematic review. Addiction (2006) 101:181–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01316.x

6. Mundt AP, Baranyi G, Gabrysch C, Fazel S. Substance use during imprisonment in low- and middle-income countries. Epidemiol Rev (2018) 40:70–81. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxx016

7. Baranyi G, Scholl C, Fazel S, Patel V, Priebe S, Mundt AP. Severe mental illness and substance use disorders in prisoners in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence studies. Lancet Glob Health (2019) 7:e461–71. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30539-4

8. Newman G. Catharsis in healing, ritual, and drama. By T. J. Scheff. Berkeley: 246 pp. In: Social Forces. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press (1981). 60:639–41. doi: 10.1093/sf/60.2.639

9. Maddox GL. Catharsis in healing, ritual and drama. Soc Sci Med (1982) 16:1386. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(82)90041-7

10. Scheff TJ, Bushnell DD. A theory of catharsis. J Res Pers (1984) 18:238–64. doi: 10.1016/0092-6566(84)90032-1

11. Pendzik S. On dramatic reality and its therapeutic function in drama therapy. Arts Psychother (2006) 33:271–80. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2006.03.001

12. Jones P. The active self: drama therapy and philosophy. Arts Psychother (2008) 35:224–31. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2008.02.006

14. Boal A. The rainbow of desire: the boal method of theatre and therapy. London: Routledge (1994) p. 1–216.

15. Yaniv D. Revisiting Morenian psychodramatic encounter in light of contemporary neuroscience: relationship between empathy and creativity. Arts Psychother (2011) 38:52–8. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2010.12.001

16. Tuluk N. Augusto boal’s treatment of the socratic method teaching techniques used in with drama in education. Procedia Soc Behav Sci (2012) 51:1050–5. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.08.286

17. Shailor J. Performing new lives: prison theatre. London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers (2011).

18. Gardner A, Hager LL, Hillman G. Prison arts resource project—an annotated bibliography. Washington, DC, US: National endowment for the arts (2014). Available: https://artsevidence.org.uk/media/uploads/prison-arts-resource-project—hillman-hager-and-gardner.pdf [Accessed 12.07.2019].

19. Brewster LG. An evaluation of the arts-in-corrections program of the california department of corrections. Santa Cruz, California: William James Association & California Department of Corrections (1983). Available: https://www.ncjrs.gov/app/abstractdb/AbstractDBDetails.aspx?id=127780 [Accessed 12.07.2019].

20. Brune K. Shakespeare Prison Project, Creating behind the razor wire: perspectives from arts in corrections in the United States. Kenosha, WI, US: Shakespeare Prison Project, University of Wisconsin. University of Wisconsin. (2008). Available: http://www.shakespeareprisonproject.com/uploads/4/9/9/0/49907227/shailor_09.pdf [Accessed 12.07.2019].

22. Harkins L, Pritchard C, Haskayne D, Watson A, Beech AR. Evaluation of Geese Theatre’s re-connect program: addressing resettlement issues in prison. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol (2010) 55:546–66. doi: 10.1177/0306624X10370452

23. Nugent B, Loucks N. The arts and prisoners: experiences of creative rehabilitation. Howard J Crim Justice (2011) 50:356–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2311.2011.00672.x

24. Cheliotis L, Jordanoska A, Sekol I. The arts of desistance. London, UK: National Criminal Justice Arts Alliance (2014). Available: http://artsevidence.org.uk/media/uploads/the-arts-of-desistance-03-11-2014.pdf [Accessed 12.07.2019].

25. Wise S. Time well spent. London, UK: The Irene Taylor Trust (2005). Available: http://www.artsevidence.org.uk/media/uploads/evaluation-downloads/mip-time-well-spent-2005.pdf [Accessed 12.07.2019].

26. Van Den Broek E, Keulen-De Vos M, Bernstein DP. Arts therapies and schema focused therapy: a pilot study. Arts Psychother (2011) 38:325–32. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2011.09.005

27. Davey L, Day A, Balfour M. Performing desistance: how might theories of desistance from crime help us understand the possibilities of prison theatre? Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol (2015) 59:798–809. doi: 10.1177/0306624X14529728

28. Cienfuegos AJ, Monelli C. The testimony of political repression as a therapeutic instrument. Am J Orthopsychiatry (1983) 53:43–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1983.tb03348.x

29. Ertl V, Pfeiffer A, Schauer E, Elbert T, Neuner F. Community-implemented trauma therapy for former child soldiers in Northern Uganda: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA (2011) 306:503–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1060

30. Mundt AP, Wünsche P, Heinz A, Pross C. Evaluating interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder in low and middle income countries. Intervention (2014) 12:250–66. doi: 10.1097/WTF.0000000000000001

31. Corporación De Artistas Por La Rehabilitación Y Reinserción Social a Través Del Arte CoArtRe. Teatro carcelario por la rehabilitación a través del arte. Santiago, Chile: CoArtRe (2017). Available: http://www.coartre.cl/teatro-carcelario-por-la-rehabilitacion-a-traves-del-arte/ [Accessed 21.08.2019].

32. Bosak J. W. Shakespeare: the tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. UK: Moby Lexical Tools, University of Sheffield (1999) p. 68, Available: https://w3.org/People/maxf/XSLideMaker/hamlet.pdf [Accessed 12.07.2019].

33. London Shakespeare Workout. LSW Prison Project: Mission Statement. London: London Shakespeare Workout Available: http://www.londonshakespeare.org.uk/Mission/prisonmission2.htm [Accessed 12.07.2019].

34. Bates L. Shakespeare saved my life: ten years in solitary with the bard. Naperville, Illinois, US: Sourcebooks (2013) p. 1–291.

35. Berlin J. Shakespeare in shackles: Laura Bates. Washington, DC, US: National Geographic Society (2014). Available: http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/innovators/2014/04/140428-innovator-laura-bates-prisons-solitary-confinement-shakespeare/ [Accessed 12.07.2019].

37. Pensalfini R. Prison Shakespeare. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan (2016) 1–233. doi: 10.1057/9781137450210

38. Corporación De Artistas Por La Rehabilitación Y Reinserción Social a Través Del Arte. Teatro y Carcel. Reflexiones, paradojas, testimonios. Santiago, Chile: Ed. Cuarto Propio (2013) p. 1–130.

39. Ramin Z. Shakespeare’s Richard III and Macbeth: a Foucauldian reading. K@ta (2013) 15:57–66. doi: 10.9744/kata.15.2.57-66

40. Shakespeare W. King Richard III. Boston: Hylton J. (1993) Available: http://shakespeare.mit.edu/richardiii/full.html [Accessed 12.07.2019].

41. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry (1998) 59:22–33 (quiz 34-57).

42. Mundt AP, Kastner S, Larrain S, Fritsch R, Priebe S. Prevalence of mental disorders at admission to the penal justice system in emerging countries: a study from Chile. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci (2016) 25:441–9. doi: 10.1017/S2045796015000554

43. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol (2006) 3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

44. Hayes N. Doing psychological research. Buckingham and Philadelphia: Open University Press (2000).

45. Frith H, Gleeson K. Clothing and embodiment: men managing body image and appearance. Psychol Men Masc (2004) 5:40–8. doi: 10.1037/1524-9220.5.1.40

46. Amendoeira MC, Tavares Cavalcanti M. Nise Magalhaes da Silveira (1905–1999). Am J Psychiatry (2006) 163:1348. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.8.1348

47. Liebling A. Can human beings flourish in prison? London, UK: National Criminal Justice Arts Alliance (2012). Available: http://www.artsevidence.org.uk/media/uploads/evaluation-downloads/can-human-beings-flourish-in-prison—alison-liebling—may-2012.pdf [Accessed 12.07.2019].

48. Ali A, Wolfert S. Theatre as a treatment for posttraumatic stress in military veterans: exploring the psychotherapeutic potential of mimetic induction. Arts Psychother (2016) 50:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2016.06.004

49. Uhler AS, Parker OV. Treating women drug abusers: action therapy and trauma assessment. Sci Pract Perspect (2002) 1:30–5. doi: 10.1151/spp021130

50. North American Drama Therapy Association. Drama therapy with addictions populations. New York, US: North American Drama Therapy Association (2015). Available: http://www.nadta.org/assets/documents/addictions-fact-sheet.pdf [Accessed 12.07.2019].

51. Caravaca Sánchez F, Luna A, Mundt A. Exposure to physical and sexual violence prior to imprisonment predicts mental health and substance use treatments in prison populations. J Forensic Leg Med (2016) 42:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2016.05.014

52. Moller L. Project “For colored girls:” breaking the shackles of role deprivation through prison theatre. Arts Psychother (2013) 40:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2012.09.007

53. Heritage P. Staging human rights: securing the boundaries? Hisp Res J (2013) 7:353–63. doi: 10.1179/174582006X150975

54. Heritage P. Rebellion and theatre in Brazilian prisons: an historical footnote. In: Thompson J, editor. Prison theatre: perspectives and practices. Jessica Kingsley Publishers (1998). p. 231–8.

55. Seligman M. Authentic happiness: using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. New York: Free Press (2002) 1–336.

Keywords: drama, art therapy, prison population, mental disorders, addiction, substance use disorders

Citation: Mundt AP, Marín P, Gabrysch C, Sepúlveda C, Roumeau J and Heritage P (2019) Initiating Change of People With Criminal Justice Involvement Through Participation in a Drama Project: An Exploratory Study. Front. Psychiatry 10:716. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00716

Received: 06 April 2019; Accepted: 06 September 2019;

Published: 03 October 2019.

Edited by:

Birgit Angela Völlm, University of Rostock, GermanyReviewed by:

Marije E. Keulen-de Vos, Forensic Psychiatric Center (FPC), NetherlandsJack Tomlin, University of Rostock, Germany

Copyright © 2019 Mundt, Marín, Gabrysch, Sepúlveda, Roumeau and Heritage. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Adrian P. Mundt, YWRyaWFuLm11bmR0QG1haWwudWRwLmNs; Caroline Gabrysch, Y2Fyb2xpbmUuZ2FicnlzY2hAY2hhcml0ZS5kZQ==

Adrian P. Mundt

Adrian P. Mundt Pamela Marín

Pamela Marín Caroline Gabrysch

Caroline Gabrysch Carolina Sepúlveda5

Carolina Sepúlveda5 Paul Heritage

Paul Heritage