- Menninger Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, United States

A Commentary on

Duty to Warn: Antidepressant Black Box Suicidality Warning Is Empirically Justified

by Spielmans GI, Spence-Sing T and Parry P (2020) Front Psychiatry doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00018

In a recent issue of Frontiers in Psychiatry, Spielmans et al. (1) defend the 2004 decision of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to issue a Black Box warning on the potential risk of suicidality in youth being administered antidepressant medications. Some researchers have claimed this action had a chilling effect on prescribing and led to an increase in youth suicides (2). Spielmans et al. (1) are to be commended for carefully reviewing and critiquing the evidence behind such claims of unintended consequences and for offering an alternative interpretation that the Black Box warning was and remains empirically justified. They are equally careful to point out the limitations of the available data, which are mostly correlational (not causal), that led to their own conclusions.

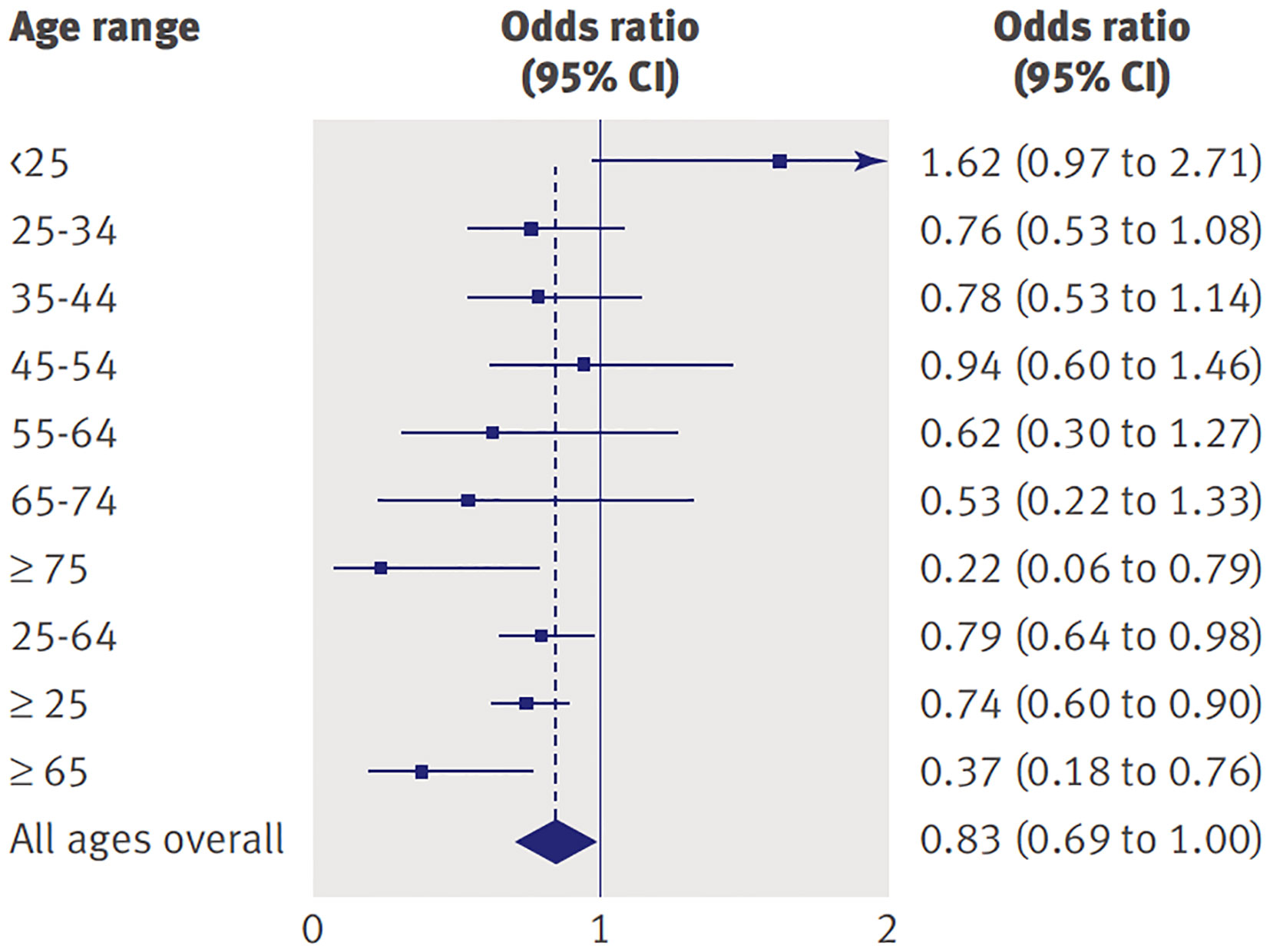

As Chair of the FDA Psychopharmacological Drugs Advisory Committee proceedings that led to the Black Box warning, one author of this commentary (WKG) had a front row seat at hearings in which both data and public testimonials from a variety of viewpoints were presented. In addition to the 2004 meeting that focused on pediatric data, another meeting was convened in 2006 in which the FDA presented data compiled from nearly 100,000 subjects across the lifespan who participated in 372 randomized controlled trials comparing antidepressant medications to placebo across a number of indications (3). The relative risk of suicidality in the drug versus placebo groups showed an interesting pattern across the age range (see Figure 1). As noted in 2004, the odds for suicidality were higher for active drug relative to placebo for individuals under age 25 years. However, for older individuals, active drug was actually protective against suicidality (both ideation and behavior) compared to placebo and this effect was most pronounced for the oldest cohorts [see Forest plot in Stone et al. (3)].

Figure 1 Odds of suicidality (ideation or worse) for active drug relative to placebo by age in adults with psychiatric disorders. Reprinted with permission from (3).

What might account for this relationship between age and risk of suicidality associated with antidepressants? Although the literature is inconclusive (4), susceptibility to and nature of SSRI-induced behavioral side effects may be a function of brain maturation occurring throughout childhood and adolescence, ending during early adulthood. This hypothesis has been supported by various rodent models (5), as well as limited human studies (6). For example, although not direct support of the link between brain maturation and SSRI-induced activation, evidence of increased dorsolateral prefrontal cortex grey-matter volume among depressed youth relative to healthy controls may suggest differing brain maturational processes (7, 8) for adolescents with psychiatric disorders. As various neural correlates (e.g., amygdala connectivity) have predicted attenuated antidepressant treatment response (9, 10), it is possible that such developmental alterations in brain maturation also relate to increased possibility of SSRI-induced behavioral side effects. Therefore, it is not surprising that the effects of antidepressants in the developing brain, both in regard to efficacy and side effects, might be different compared to adult brains. In 2007, Goodman et al. (11) hypothesized that antidepressants might induce “behavioral toxicity” in some susceptible youth that could act as a precursor for suicidality if undetected. Those preceding behavioral effects can assume various manifestations including activation syndrome (11). Once antidepressant induced suicidality is conceptualized as a behavioral side effect, it becomes less surprising that it can occur at higher rates in the active versus placebo arms of a study.

How to best monitor for early signs of adverse behavioral effects during treatment that could evolve into suicidality remains an unanswered question. The Treatment-Emergent Activation and Suicidality Assessment Profile (TE-ASAP) was developed to assist parents and child and adolescent psychiatrists with monitoring behavioral side effects during antidepressant treatment of youth (12). This 38-item scale covers several constructs often associated with activation syndrome, including irritability, hyperactivity, disinhibition, motor restlessness, externalizing behaviors and hypomanic symptoms. In a study of 56 youth with obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) who participated in a double-blind trial of sertraline versus placebo, the TE-ASAP showed acceptable psychometric properties (12). The study was too small to assess how well it identified participants at risk of suicidality.

It seems inconceivable that antidepressants would induce suicidality in the absence of other associated or antecedent behavioral changes. The essential message of the Black Box is to remind prescribers and consumers about the importance of monitoring closely for adverse behavioral changes during the initiation of (or changes in) antidepressant therapy in order to reduce the risk of suicidality in patients through age 24 years. The intention was not to discourage appropriate prescribing of antidepressants for youth with depression, OCD or anxiety disorders. In fact, some evidence, as reviewed by Fornaro et al. (13), suggested substantial reductions in antidepressant medication prescriptions in children and adolescents following the Black Box Warning (14). In addition, the period following the Black Box Warning was associated with an increased number of attempted/completed suicides (15), increased utilization of antipsychotic and benzodiazepine medications (2) and no significant change in use of psychotherapy (16). For the majority of these patients, the benefits of antidepressants greatly outweigh the risks. Nevertheless, we agree with Spielmans et al. (1) that prescribers have a “duty to warn” and highlight the need for adequate training for all potential prescribers during medical school and residency programs.

Author Contributions

Both authors made substantial contributions to conceptualization and preparation of this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Spielmans GI, Spence-Sing T, Parry P. Duty to warn: antidepressant black box suicidality warning Is empirically justified. Front Psychiatry (2020) 11:1–16. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00018

2. Lu CY, Zhang F, Lakoma MD, Madden JM, Rusinak D, Penfold RB, et al. Changes in antidepressant use by young people and suicidal behavior after FDA warnings and media coverage: quasi-experimental study. Bmj (2014) 348:g3596. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3596

3. Stone M, Laughren T, Jones ML, Levenson M, Holland PC, Hughes A, et al. Risk of suicidality in clinical trials of antidepressants in adults: analysis of proprietary data submitted to US Food and Drug Administration. BMJ (2009) 339:b2880. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2880

4. Cousins L, Goodyer IM. Antidepressants and the adolescent brain. J Psychopharmacol (2015) 29:545–55. doi: 10.1177/0269881115573542

5. Gross C, Zhuang X, Stark K, Ramboz S, Oosting R, Kirby L, et al. Serotonin1A receptor acts during development to establish normal anxiety-like behaviour in the adult. Nature (2002) 416:396–400. doi: 10.1038/416396a

6. Glover ME, Clinton SM. Of rodents and humans: A comparative review of the neurobehavioral effects of early life SSRI exposure in preclinical and clinical research. Int J Dev Neurosci (2016) 51:50–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2016.04.008

7. Straub J, Brown R, Malejko K, Bonenberger M, Gron G, Plener PL, et al. Adolescent depression and brain development: evidence from voxel-based morphometry. J Psychiatry Neurosci (2019) 44:237–45. doi: 10.1503/jpn.170233

8. Paus T, Keshavan M, Giedd JN. Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nat Rev Neurosci (2008) 9:947–57. doi: 10.1038/nrn2513

9. Cullen KR, Klimes-Dougan B, Vu DP, Westlund Schreiner M, Mueller BA, Eberly LE, et al. Neural correlates of antidepressant treatment response in adolescents with major depressive disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol (2016) 26:705–12. doi: 10.1089/cap.2015.0232

10. Klimes-Dougan B, Westlund Schreiner M, Thai M, Gunlicks-Stoessel M, Reigstad K, Cullen KR. Neural and neuroendocrine predictors of pharmacological treatment response in adolescents with depression: A preliminary study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry (2018) 81:194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.10.015

11. Goodman WK, Murphy TK, Storch EA. Risk of adverse behavioral effects with pediatric use of antidepressants. Psychopharmacol (Berl) (2007) 191:87–96. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0642-6

12. Bussing R, Murphy TK, Storch EA, McNamara JP, Reid AM, Garvan CW, et al. Psychometric properties of the Treatment-Emergent Activation and Suicidality Assessment Profile (TEASAP) in youth with OCD. Psychiatry Res (2013) 205:253–61. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.09.019

13. Fornaro M, Anastasia A, Valchera A, Carano A, Orsolini L, Vellante F, et al. The FDA “Black Box” warning on antidepressant suicide risk in young adults: more harm than benefits? Front Psychiatry (2019) 10:294. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00294

14. Kurian BT, Ray WA, Arbogast PG, Fuchs DC, Dudley JA, Cooper WO. Effect of regulatory warnings on antidepressant prescribing for children and adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med (2007) 161:690–6. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.7.690

15. Gibbons RD, Brown CH, Hur K, Marcus SM, Bhaumik DK, Erkens JA, et al. Early evidence on the effects of regulators’ suicidality warnings on SSRI prescriptions and suicide in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry (2007) 164:1356–63. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07030454

Keywords: suicidality, Black Box, activation syndrome, behavioral toxicity, antidepressants

Citation: Goodman WK and Storch EA (2020) Commentary: Duty to Warn: Antidepressant Black Box Suicidality Warning is Empirically Justified. Front. Psychiatry 11:363. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00363

Received: 25 February 2020; Accepted: 14 April 2020;

Published: 30 April 2020.

Edited by:

Michele Fornaro, New York State Psychiatric Institute (NYSPI), United StatesReviewed by:

Laura Orsolini, University of Hertfordshire, United KingdomMirko Manchia, University of Cagliari, Italy

Copyright © 2020 Goodman and Storch. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wayne K. Goodman, d2F5bmUuZ29vZG1hbkBiY20uZWR1

Wayne K. Goodman

Wayne K. Goodman Eric A. Storch

Eric A. Storch